Abstract

This paper addresses the seismic retrofitting of masonry churches with timber roofs by designing a ductile roof diaphragm with a new energy-based methodology. The proposed approach relies on nonlinear dynamic analyses conducted on an equivalent structural model. In this model, masonry nonlinearity is represented by rotational plastic hinges at the base of the equivalent wall elements. Roof system nonlinearity is modeled by shear plastic hinges simulating the energy dissipation of steel connections. In the equivalent model, the earthquake is implemented using a set of spectrum-compatible accelerograms. The dynamic response of the aforementioned plastic hinges is analyzed in terms of equivalent damping during the seismic events by extracting the relevant hysteresis cycles. This allows for the evaluation of both dissipated and strain energy. The estimation of the equivalent damping ratio provided by the roof diaphragm is based on multiple design configurations. After identifying the maximum achievable damping ratio, the study suggests ways to determine the corresponding roof stiffness, which defines the optimal retrofit configuration. This configuration is then implemented in a three-dimensional model that includes nonlinear properties for both masonry and connection elements, allowing a validation of the seismic response obtained from the initial equivalent model with a more complex and detailed model. Finally, a seismic response comparison is conducted between the optimized dissipated energy configuration, based on damping ratio evaluation, and an overstrength design variant determined considering the elastic behavior of the roof connections.

1. Introduction

The seismic vulnerability of historic masonry churches with single-nave configurations and timber roof systems has been repeatedly demonstrated by earthquakes throughout the years. This kind of construction is widely present all over the world, especially in Europe. The vulnerability under the seismic action can be primarily attributed to overturning mechanisms of the perimeter walls in the nave transversal response [1,2,3]. Out-of-plane mechanisms lead to the loss of support for the roof beams, and excessive rocking induces compressive or tensile stresses that exceed the mechanical capacity of the masonry [4,5]. The high seismic vulnerability of single-nave historical churches can be attributed to an insufficient energy dissipation of the roof diaphragm and an inadequate system of connections between the structural macro-components (i.e., walls, façade, and roof) [6,7]. Moreover, the very frequent slenderness of perimeter walls can be associated with the lack of transverse connection, and in some cases, poor masonry quality can lead to the collapse of upper portions of the walls and subsequent roof failure [8]. Even when seismic-resistant elements are present in the transverse direction (e.g., triumphal arches, wooden trusses, steel ties), in-plane shear failure may occur in the façade or arches if the roof structure is unable to dissipate inertial forces through the steel connections between timber elements [9,10].

Therefore, the role of a dissipative roof diaphragm is crucial in limiting the rocking of the perimeter walls and maintaining the shear forces within safe limits, particularly those transmitted to the façade [11]. To achieve global box-like behavior and maximize energy dissipation, this study proposes an energy-based retrofit methodology for masonry churches with timber roofs, focusing on the design of a ductile roof diaphragm that can dissipate seismic energy [12]. In conventional modeling approaches, the roof system is represented by beam-type elements for trusses and plate-type elements for decking panels or other timber-based solutions (e.g., phenolic panels, CLT, double-layered decking) [13,14,15]. This strategy usually omits the explicit modeling of connections. As a result, under transverse seismic loading, the connections are designed to resist in-plane shear forces derived from the plate elements of the roof [16]. However, the absence of nonlinear connections in the model prevents the evaluation of their energy dissipation capacity. Including this contribution can reduce in-plane shear forces on the panels, allowing for thinner panels. It can also enable an optimized design of the retrofitting intervention in which the connection system dissipates energy through a different mechanism than the original configuration [17,18].

This energy-based approach avoids overly stiff solutions that rely solely on overstrength. Such solutions may reduce displacement, but they increase in-plane shear forces within the roof. They also increase the shear demand on seismic-resistant elements aligned in the transverse direction (e.g., triumphal arches, façades, and walls), which raises the risk of their in-plane collapse [19].

This paper aims to identify a panel-to-panel connection configuration of the retrofitted roof that optimizes the seismic response of a typical one-nave historical church by maximizing the damping effect provided by the connections [20]. Nonlinear dynamic analyses are performed on an equivalent structural model using mono-dimensional finite elements for both walls and roof. Masonry behavior is modeled with rotational plastic hinges, while the timber roof system includes shear plastic hinges simulating the hysteretic response of the steel connections [21]. Spectrum-compatible accelerograms are used to simulate seismic input, and the dynamic response is evaluated in terms of equivalent damping ratio (EDR) derived from hysteresis cycles of the inelastic hinges [21,22]. This allows quantification of the dissipated and strain energy and estimation of damping ratios for different retrofit configurations, in accordance with ATC-40 [21] and FEMA 356 [22].

After selecting the technological solution of inclined timber panels positioned over the existing planks, the optimal connection configuration is defined by the maximum achievable damping. The equivalent finite element model (FEM) allows the simulation of different connection layouts, as the transverse response of the nave is governed by a hysteretic variable (βHYS) that combines the yielding strength of roof connections and masonry walls [23,24,25,26,27,28]. As βHYS varies, roof stiffness changes as well, and different seismic responses occur. Each nonlinear dynamic analysis yields a potential retrofit solution. The optimal βHYS maximizes EDR, limits transverse displacement to prevent out-of-plane mechanisms, and keeps stresses within the strength limits of the considered timber and masonry materials [29,30].

For a case study, possible retrofitting interventions can be tested through nonlinear dynamic analyses performed on the equivalent FEM. The configuration that maximizes the equivalent damping ratio is then selected and implemented in a three-dimensional nonlinear model, which incorporates detailed material behavior for both masonry and connection elements [23]. This allows for a direct comparison with the conventional overstrength-based design strategy, providing a clearer evaluation of the advantages offered by a retrofit approach based on connection ductility rather than resistance [21,22].

In summary, Section 2 explains the criteria for implementing the equivalent FEM to simulate nonlinear dynamic analyses and obtain the response of inelastic hinges during seismic events. Section 3 presents the time history method developed to evaluate the equivalent damping ratio for various retrofitted roof diaphragm configurations, identifying the one corresponding to the maximum EDR. Section 3 details the equations used to evaluate the stiffness of the ductile roof diaphragm at maximum EDR. Section 4 illustrates a case study in which the optimized configuration of connections and timber-based panels is applied to prevent out-of-plane wall mechanisms and maintain stress levels within the mechanical limits of the materials.

2. Simulation of the Ductile Roof Diaphragm’s Role

The seismic response of a single-nave masonry church with a timber roof structure under a transverse earthquake depends on the behavior of both the walls and the roof system. The involved parts of the structure can be classified as macro-elements, specifically the façade, the head wall, the bays, and the roof. Each bay consists of two lateral wall portions, their connecting truss or arch, and the tributary part of the roof [31].

These bay elements form a seismic-resistant system oriented in the transverse direction. In the following, this generic “bay system” will be referred to as the “frame”. Similarly, the façade and the head wall also act as seismic-resistant systems under transverse excitation, but they exhibit greater inertia and stiffness compared to the frames.

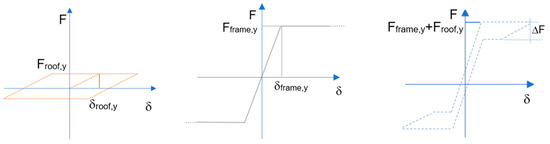

A frame system without a ductile roof diaphragm is susceptible to uncontrolled rocking, since the original roof cannot provide a box-behavior response or dissipate energy [32]. Therefore, the response of a generic frame can be represented by a linear elastic diagram. This diagram shows the yielding force (Fframe,y)—corresponding to the point at which the masonry exits the elastic domain—and its associated displacement (δframe). Their ratio defines the stiffness of the generic frame (Kframe).

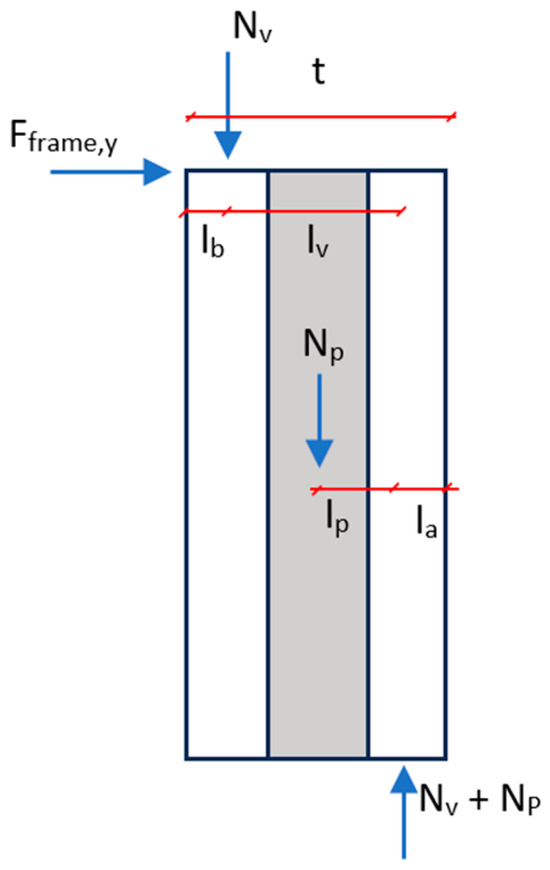

In the equivalent FEM, the capacity of the vertical elements corresponding to the perimeter walls is determined by the evaluation of Fframe,y depending on the geometry and the vertical loads due to the roof, perimeter walls, and abutment (Figure 1). Under the seismic action, the stabilizing moments of the two walls (left and right walls pertaining to a frame) must sustain the overturning moment due to Fframe,y. Therefore, the stabilizing moments can be obtained starting from Equations (1)–(3) and referring to Figure 1, where Nv is the load transferred from the roof and Np is the self-weight of the wall with the abutment.

Figure 1.

Geometry and loads to be considered for Fframe,y in case of perimeter walls with abutments.

To improve the church’s seismic response, a dissipative roof system can be proposed, consisting of timber-based panels (inclined according to the roof slopes) connected by steel connectors capable of dissipating energy (i.e., panel-to-panel connections). Under transverse seismic loading, these connections can exhibit a cyclic behavior. The energy dissipated during a given cycle is represented by the area enclosed within each hysteresis loop. Accordingly, the cyclic response of the roof is characterized by a yielding force and its associated displacement, denoted as Froof,y and δroof,y, respectively, whose ratio defines the stiffness of the connection [32,33].

The stiffness of the connector used in the connections can be determined either from experimental tests or from code provisions [34]. The stiffness, yielding force, and yielding displacement change when the geometric characteristics of the connection (e.g., connector diameter, spacing, presence of metal cover plates, etc.) are modified. Given the cyclic nature of the connection response, an ultimate force and displacement can also be defined, denoted as Froof,u and δroof,u.

By combining the response of the generic frame with the dissipative roof, the elastic bilinear behavior of the generic frame is coupled with the elastic-plastic response of the roof system. In this way, the seismic response of the retrofitted church can be represented by a flag-shaped diagram [32], whose enclosed area corresponds to the energy dissipated by a frame during the seismic event as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representation of the nave transversal response; on the (left): the dissipative effect of the roof diaphragm; (center): the uncontrolled rocking of the walls; on the (right): the flag-shaped diagram of the ductile transverse frame.

The geometry of the flag-shaped diagram depends on a dimensionless hysteretic variable denoted as βHYS, which varies within the range 0 < βHYS < 1.50. The optimal value of this variable cannot be defined a priori, as increasing βHYS inhibits the re-centering capacity of the frame in the damped rocking [32]. Moreover, excessive values of βHYS beyond the limit of 1.5 may result in over-strengthened and overly stiff solutions [31].

The hysteretic variable correlates the mechanical characteristics of the retrofitted roof with the inelastic properties of the masonry walls (4). Knowing Fframe,y from the properties of the lateral walls, Froof,y can be evaluated for different values of βHYS by using Equation (5). Furthermore, Equation (6) describes the roof stiffness kroof as a function of βHYS.

To optimize the dissipative roof system, it is necessary to determine when the roof and its connections begin to dissipate energy with respect to the behavior of the masonry walls. Ideally, both the masonry and the roof should exit their elastic domains simultaneously, reaching their respective yielding points at the same time. For this purpose, a parameter Δ is introduced in Equation (7). When Δ = 1, this condition is satisfied. If Δ << 1, the connections would activate prematurely, when the masonry has not yet begun rocking, resulting in ineffective energy dissipation. Conversely, if Δ >> 1, the masonry reaches its yielding force before the connections begin to dissipate, which may lead to excessive displacements in the lateral walls. Therefore, from a design perspective, it is recommended to target the condition Δ = 1 or at least remain lower and very close to this value.

With reference to the following, in summary: (i) Figure 1 and Equations (1)–(3) describe the force equilibrium to be considered in order to calculate the yielding strength of the lateral walls subjected to transverse seismic action; (ii) Equations (4)–(8) describe the relationship between the response of the lateral masonry walls and the damping behavior of the roof under transverse seismic loading.

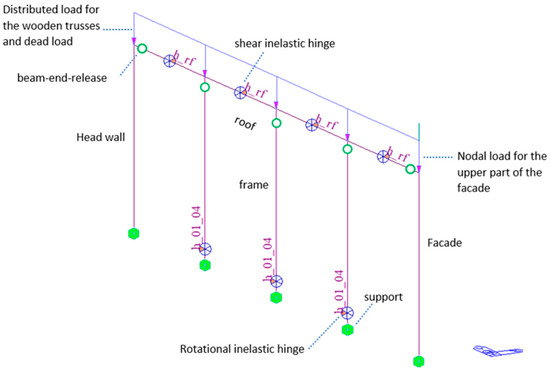

To simulate possible retrofitted configurations without an excessive computational effort, a numerical approach based on an equivalent finite element model is adopted. Equivalent FEM (Figure 3) represents the macro-members of the structure involved in the nave transversal response [35]. It is implemented with equivalent mono-dimensional elements representing the walls and the roof in terms of geometry, inertia, and masses. The vertical elements represent the distribution of stiffness and masses of the masonry walls; the horizontal elements represent the structural behavior of the roof’s panels (the wooden trusses are considered in the FEM only in terms of distributed loads). The self-weight of the equivalent FEM corresponds to the real structure. The masses and inertias of the masonry elements correspond to their actual values, thanks to the detailed knowledge of the in-situ geometries [35]. Earthquake loads are considered through a set of seven spectrum-compatible accelerograms perpendicularly oriented with respect to the nave’s longitudinal axis [36,37].

Figure 3.

Case study: representation of the equivalent frame FEM.

Considering that the most common failure mechanism of a church under transverse earthquake loads involves rocking of the perimeter walls, the equivalent FEM assumes that rotational inelastic hinges will be activated at the base of the equivalent vertical members during the ground shaking. The inelastic behavior of the masonry walls is modeled by rotational inelastic hinges located at the base of the vertical equivalent elements, except for the façade and the head wall, which are implemented as elastic elements due to their high in-plane strength and stiffness [35]. These rotational inelastic hinges are described in terms of moment-rotation (M-φ) diagrams. All of the vertical elements are perfectly restrained at the base. At the same time, the elements of the roof structure are also stressed by the ground shaking, possibly beyond their elastic range. In this work, it is assumed that connections will be plasticized before wood panels, leading to a more ductile behavior of the retrofitted roof. To account for this behavior, the inelastic properties of the potential retrofitted configuration of the roof diaphragm are represented by in-plane shear hinges located in the middle of each horizontal equivalent element and described by shear-deformation (V-η) diagrams. In the equivalent FEM, the inelastic hinges of the roof could be described by the stiffness-degrading hysteretic model [38,39].

Finally, the elements representing the roof and the walls are connected by hinges located at the top end of the vertical elements. The wood roof diaphragm is also pinned to the head wall and façade. Under seismic action, the rocking trigger of the walls is allowed by releasing the bending moment transferred to the roof. At the same time, the roof behaves as a deformable diaphragm. If the stiffness of the roof is opportunely calibrated, the roof diaphragm works as a damper placed on top of the church [35] because the rocking of the walls is controlled, the top transverse displacements are limited within a safety range (the limit value of the horizontal displacement is usually fixed as hw < 0.05%, where hw is the perimeter walls’ height [31,35]), and the in-plane shear forces on the roof’s panels, the head wall, and the façade are also limited (compared to their capacity).

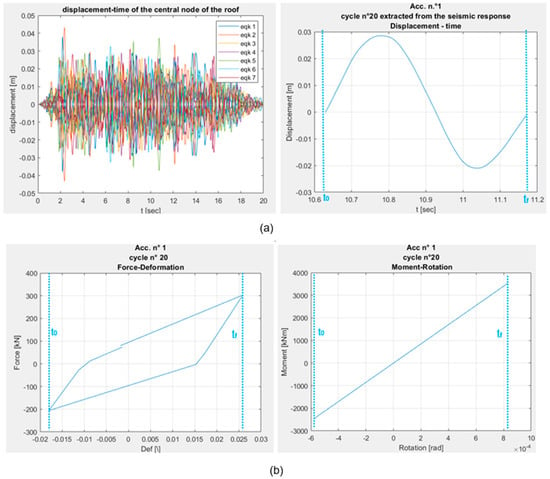

3. Energy-Based Method for the Optimum Ductile Diaphragm

The time history of the maximum displacement of the roof (i.e., the central node of the roof in the equivalent FEM model) can be determined by performing nonlinear dynamic analyses on the equivalent FEM, for each accelerogram and for different values of the hysteretic variable. Each response is characterized by several cycles (Figure 4a), each one defined by an initial and final time instant, respectively named t0 and tf. Each cycle contains a maximum positive transverse displacement and a maximum negative transverse displacement (t0 and tf identify the zero displacement points). During each cycle, the inelastic hinge of the roof responsible for the energy dissipation can exhibit elastic-plastic behavior in t0 − tf. If no energy is dissipated (in t0 − tf), the response of the hinge remains linear (Figure 4b). Similarly, the inelastic hinges located at the base of the frames also exhibit a nonlinear elastic response within the same cycle [31].

Figure 4.

Response of the inelastic hinges in a generic cycle for the evaluation of EDR: (a) on the left: displacements of the central part of the roof for the seven accelerograms; on the right: an example of a cycle extracted from the time history response—(b) examples of force-deformation cycles extracted from the time history response: on the left: 20-th cycle for accelerogram number 1 for an inelastic hinge of the roof; on the right: 20-th cycle for accelerogram number 1 for an inelastic hinge of the walls.

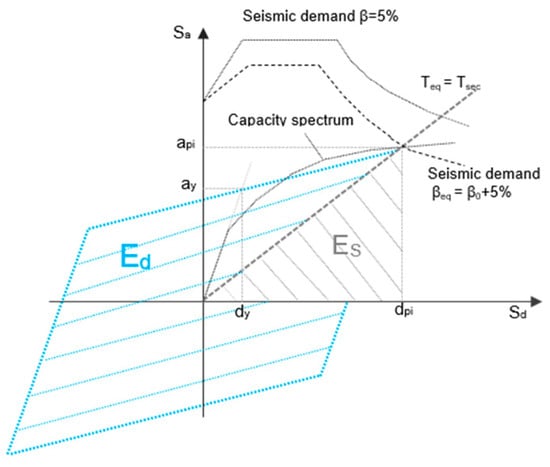

By dividing the overall structural response into a finite number (n) of cycles, the EDR can be computed for each cycle through Equation (9), where i represents the i-th cycle (for i = 1 − n) extracted from the time history displacement response of the structure, ED,i is the energy dissipated by the inelastic hinge in the hysteresis loop of the i-th cycle, and ES0,i is the strain energy of the inelastic hinge in the i-th cycle. Clearly, since the nonlinear properties of the frames are represented by elastic bilinear diagrams, the inelastic hinges of the frames contribute only in terms of ES0,i. Equation (9) and Figure 5 are based on [21,22,40], where 5% represents the inherent damping of the structure [41,42,43,44].

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of the energies considered in the EDR evaluation according to ATC-40 and FEMA 356. Note: the shaded blue area represents the dissipated energy, while the shaded grey area represents the strained energy. Regarding the spectrum: the solid line indicates the spectrum for 5% inherent damping; the dashed line represents the scaled spectrum also considering the contribution of the damping and strain energies.

Different possible retrofitted configurations can be tested by varying βHYS. Thus, for each roof configuration, the overall EDR can be evaluated. Then, the optimal retrofitting configuration can be selected by maximizing the EDR, ensuring that displacements remain below their limit value (0.005hw) and the in-plane shear on the façade remains compatible with the masonry’s capacity. The optimum solution identifies the optimal value of the hysteretic variable βHYS-opt.

For detecting the optimal βHYS-opt, nonlinear dynamic analyses were performed using Midas Gen 2025 v 1.1 software [45] within the range 0 ≤ βHYS ≤ 1.50. A dedicated MATLAB R.2025a [46] routine was developed by the authors to extract the Midas Gen’s results—in terms of displacements and inelastic hinges responses—and to automatically evaluate EDR for each cycle and for the overall structure. In this way, EDR is plotted as a function of βHYS, allowing the identification of the βHYS-opt.

The following set of Equations (10)–(14) provides all the necessary elements for evaluating the equivalent stiffness of the roof. Given the known mechanical and geometric properties of the panels and connections as well as the geometric characteristics of the church, it is possible to calculate the equivalent stiffness of the retrofitted dissipative roof solution as a function of a single parameter, such as the number of connection stripes per bay.

For the βHYS-opt value of the hysteretic variable, the corresponding stiffness of the optimized ductile roof diaphragm retrofitted configuration [32,33] can be evaluated using Equation (10), where kdf is the bending stiffness, kdt is the shear stiffness, is the equivalent elastic modulus evaluated using Equation (11), is the equivalent shear modulus evaluated using Equation (12), is the ideal inertia moment of the section evaluated using Equation (13), and A* is the shear equivalent area given using Equation (14). In Equations (11)–(14), the contribution of both the steel connections and the wooden based panels are present. In fact, nws is the homogenization coefficient of the steel-to-wooden diaphragm connection given by nws = Es/ (where Es is the steel elastic modulus), L is the distance between the seismic-resistant elements (spacing between frames), Ly is the width of the roof, i is the spacing of the connectors, kn is the stiffness of a single connector, tw is the thickness of the wooden panels, χ = 6/5(cos2α) is the shear factor of the cross-section (χ = 1.2 for rectangular sections), Aw is the cross-section area of the roof diaphragm, nn is the number of connectors for each connection stripe (ratio between the spacing of the seismic elements and the spacing of the connectors), ns is the number of the connection stripes for each span, and As is the cross-section area of the steel stripes covering the heads of the connectors in the panel-to-panel connection.

Based on the considerations outlined in this Section 3 and considering Equations (1)–(14), the procedure to identify the roof diaphragm configuration that maximizes EDR can be summarized as follows. The yielding forces of the walls Fframe,y are calculated using Equations (1)–(3), knowing the geometry and mechanical properties of the masonry elements. By varying βHYS, Froof,y is evaluated with Equation (5), and the roof’s stiffness kroof can be expressed in terms of βHYS with Equation (6). Keeping Δ = 1 in Equation (7), the value of the roof’s stiffness kroof is determined with Equation (8).

By performing nonlinear dynamic analyses for different values of the hysteretic variable, the cyclic responses of both the roof and the frames’ plastic hinges are obtained from the equivalent FEM. Using Equation (9), a dedicated MATLAB routine extracts the results from the FEM’s outputs and computes the EDR of the structure, which is then plotted as a function of βHYS. The optimal value of the hysteretic variable βHYS-opt is identified at the point corresponding to the maximum EDR. For EDR evaluation, βHYS values greater than 1.5 can be excluded because they typically result in an overly stiff and over-strengthened roof structure.

Once the βHYS-opt value is determined, the type of panel, the type of connector, and the geometry of the steel stripes can be selected. The only unknown remaining is the number of connection stripes per bay, named nn, which can be derived by combining Equations (10)–(14), as all of the other involved parameters are known.

An application of this procedure is presented in Section 4, where an elastic-plastic panel-to-panel connection is optimized to control the drift and limit the in-plane shear on the roof. Thus, the optimization goal is to keep both the wood panels and the connectors within the elastic domain, allowing energy dissipation to occur primarily through the steel stripes.

4. Case Study

4.1. Description

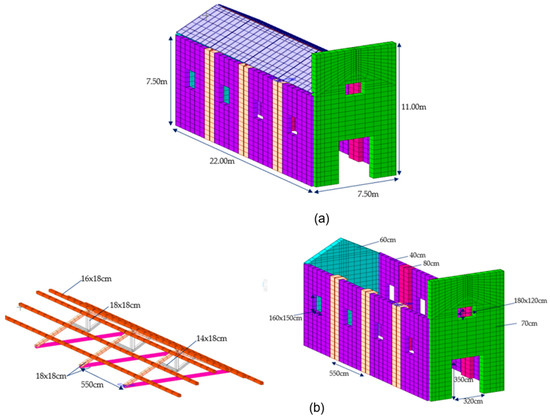

The one-nave church analyzed in this paper has a 22 × 7.50 m rectangular plan, 70 cm thickness façade, and 60 cm thickness head wall. The thickness of the perimeter walls is 40 cm, but abutments with 80 cm thickness are located along the perimeter walls with a spacing of 5.5 m, so the church has four bays 5.5 m in width. Four 1.60 × 1.50 m openings are present on each perimeter wall; the walls are 7.50 m in height. The original roof structure is realized with hardwood trusses: horizontal tie beams and inclined rafters of 18 × 18 cm cross section, struts with a 14 × 18 cm cross section, a king post with an 18 × 18 cm cross section, joists with a 16 × 18 cm cross section, and 2.5 cm thick planks. The masonry of the walls has a Young’s modulus of E = 1100 MPa and a density of ρ = 18 kN/m3. The hardwood elements have a Young’s modulus parallel to the fibers of E0,mean = 10,000 MPa, shear modulus Gmean = 630 MPa, tensile strength parallel to the fibers ft,0,k = 18 MPa, and a density ρw = 5.00 kN/m3.

Initially, a 3D FEM of the church is implemented with linear behavior of the materials and without the presence of the roof’s nails. The earthquake is described with its elastic spectrum, according to the Italian design code [47], as a function of the following site-specific parameters: peak ground acceleration PGA = 0.12 g, return period TR = 475 years, constant acceleration-velocity transition period T*c = 0.297 s, horizontal amplification factor Fo = 2.62, and vertical amplification factor Fv = 1.16. The 3D FEM of the church is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Case study: (a) 3D view; (b) on the left: wooden trusses; on the right: particular of the perimeter walls with the abutments and the openings.

4.2. Design Configuration from EDR

Starting from the design target behavior, the equivalent FEM is implemented following the rules explained in Section 2, and possible ductile roof diaphragm solutions are tested by varying βHYS in the 0–1.8 range (also investigating an over-stiff condition when βHYS = 1.8) and considering seven spectrum-compatible accelerograms as seismic input. The results obtained from the equivalent FEM are averaged over the considered accelerograms to obtain the average value of each design parameter. By assuming Δ = 1, the properties of the roof’s inelastic hinges can be defined as a function of the hysteretic variable βHYS. Consequently, six possible configurations of the roof are analyzed. Table 1 reports the parameters of the inelastic hinges adopted for the roof and walls in the nonlinear analyses of the equivalent FEM. In Table 1, points P1-D1 and P2-D2 respectively represent the yielding and ultimate points for the inelastic hinges characterized by the stiffness-degrading model (Clough hysteretic model) [38,48]. P1 and P2 are the yielding and the ultimate force of the roof’s inelastic hinges, respectively, and D1 and D2 are the dimensionless drifts due to the mutual distance between the frames.

Table 1.

Properties of the inelastic hinges for the Clough model used in the equivalent FEM.

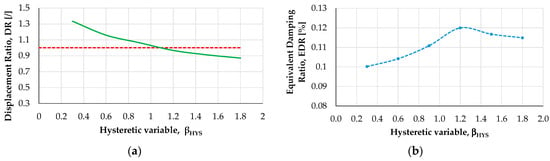

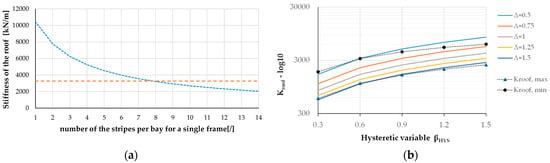

The EDR is evaluated for different values of the hysteretic variable by detecting the cyclic responses of the inelastic hinges of the roof and the corresponding elastic strain energies. Furthermore, the elastic strain energies of the bilinear rotational hinges at the base of the frame are also evaluated. Figure 7 shows the variations in the EDR and displacement ratio (defined as the ratio between the transverse displacements and the target displacement) as a function of the hysteretic variable. The corresponding values obtained from the nonlinear dynamic analyses for the seven spectrum-compatible accelerograms are listed in Table 2.

Figure 7.

Averaged transverse displacements (a) where the green line is the variation of the Displacement Ratio and the red line represents the target value; EDR (b) as a function of the hysteretic variable (for the seven selected accelerograms).

Table 2.

Transverse displacements and EDR values for different values of the hysteretic variable (for the seven selected accelerograms).

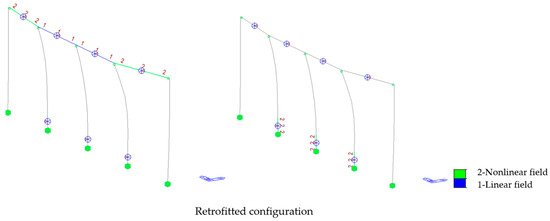

From Table 2 and Figure 7, βHYS-opt = 1.2 is detected (maximum of the EDR curve). Beyond the optimum value, EDR begins to decrease, indicating that the corresponding roof configuration may become excessively stiff. Furthermore, in terms of displacements, the reduction of the displacement ratio is still present also for βHYS-opt = 1.2, but with a lower slope. However, the transverse displacement is reduced from about 5.0 cm to 3.5 cm for the yielding of the inelastic hinges. Figure 8 shows the yielding status of the plastic hinges during the seismic event in the retrofitted configuration, for βHYS-opt = 1.2.

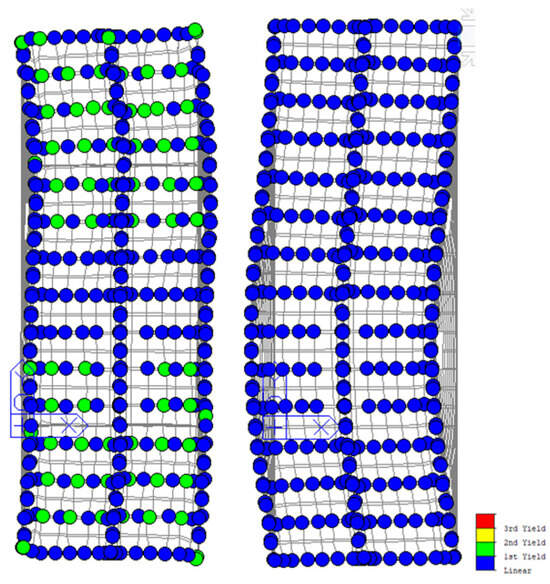

Figure 8.

Status of yielding of the inelastic hinges at the end of the accelerogram 1 for the retrofitted configuration (βHYS-opt = 1.2). Symbol 1 and blue color means that the hinge remains in the elastic field; Symbol 2 and green color means that the hinge status is in the nonlinear field.

Consequently, the optimum value of the hysteretic variable is adopted for the design of the roof diaphragm and Equations (10)–(14) are applied to define the configuration of the panel-to-panel connections, fixing the following criteria: (i) multilayer panels with a thickness of tw = 2.5 cm are adopted [49]; the panels are characterized by an elastic moduli Ew = 6790 MPa, a shear modulus Gw = 1090 MPa, a tensile strength parallel to the fibers fw,0,k = 11 MPa, and a density ρw = 650 kg/m3 (although other typologies of panels, such as cross-laminated timber CLT, could have been selected depending on the designer’s choice); (ii) screws diameter ϕ = 8 mm as connectors; (iii) and a steel stripe acting as a cover connection realized in S275 steel with a cross section of 80 × 5 mm [50,51,52,53].

Accordingly, a design shear force per connector of Vn = 1 kN is assumed (the yield resistance of the connector is about 3 kN), leading to a connector spacing of 23 cm [50]. Consequently, the number of connectors for single steel stripe results in nn = 35. Based on these parameters and knowing the geometry of the church, it is possible to evaluate , , , and A* (defined in Section 2) as a function of the number of stripes ns distributed on the bays, referring to a single frame of the equivalent FEM. By varying this ns, different values of the roof stiffness can be obtained and compared against the optimal target. Figure 9a and Table 3 present stiffness values corresponding to ns ranging from 4 to 14 in relation to the commercial side of the selected panel (available from 0.8 m to 2.8 m). The final configuration adopts eight connection stripes on the two bays (with a total length of 11 m), which falls within the limits of technological feasibility (as illustrated in Figure 9b) and yields an optimized configuration with a resulting value of Δ = 1.01 while ensuring the simultaneous yielding of both the masonry and the roof system.

Figure 9.

(a) Graphical identification of the number of connection stripes based on the roof stiffness, assuming a target displacement Δ = 1; (b) Technological feasibility assessment based on roof stiffness kroof, hysteretic variable βHYS, and yielding behavior of the roof with respect to the masonry capacity.

Table 3.

Roof stiffness kroof [kN/m] in relation to βHYS and Δ, considering the available commercial dimensions of the selected wooden panels.

As previously stated, the design ensures that both the wooden panels and the connectors remain within the elastic domain, while the steel stripes are intended to dissipate energy by plastic deformation. It means that, after a strong site earthquake, only the steel stripes must be replaced (because they are damaged) while the other components of the roof diaphragm could be kept (without evident damage).

As the steel stripe is the primary energy dissipating element, it should be capable of yielding under the design shear demand. To achieve this behavior, some localized weakening can be introduced along the stripes so that the stripes can deform plastically under the connector’s design shear force (in this case assumed as Vn = 1 kN).

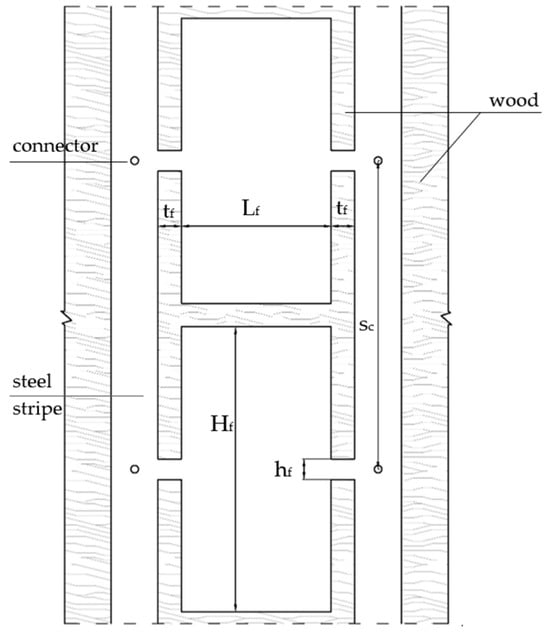

Essentially, dissipative behavior is controlled by the weakest component in the connection system. For this reason, as suggested in [32,33], a viable solution consists of introducing notches between the axes of the connectors along the stripes. According to the procedure described in [32,33], these notches could be shaped as shown in Figure 10. The value of hf is determined from Equation (15), which depends on the properties characterizing the shear behavior of the connector: Vn, Lf, tf, fyd (here assumed equal to 235 MPa), and the spacing between the connectors sc [32,33,54,55]. The definition of the dimensions of the notch depends on the evaluation of the local stiffness. In fact, considering the part of the stripes where the notches are present, the stiffness of the single connector Kconn can be evaluated according to [34]. The elastic stiffness evaluated with Equation (16) should be lower than Kconn [32,33]. In Equation (16), the yielding relative displacement is evaluated considering the ultimate rotation of the short double-cantilever activated between two notches.

Figure 10.

Local weakening of the steel stripes.

Therefore, with the aim of yielding the weakened steel stripes with notches while keeping the connectors and panels in the elastic field, the retrofitted configuration provides 2.5 cm thickness phenolic panels, number 8 S235 steel stripes having a cross section of 0.5 × 22 cm for a length of 11 m per bay, ϕ = 8 mm steel connectors every 20 cm. The notches present on the steel stripes are characterized by the following dimensions: Lf = 50 mm, tf = 20 mm, Hf = 50 mm and hf = 11 mm.

4.3. Validation by 3D FEM

The improvements due to the dissipative roof structure were also investigated by implementing 3D models to validate the procedure based on the equivalent FEM analysis and EDR evaluation. Three different 3D models of the analyzed church were developed: (A) the initial non-retrofitted configuration, already described in Section 4.1; (B) the retrofitted configuration designed for the optimal value of the hysteretic variable βHYS-opt; (C) an over-stiff configuration.

Passing from model A to model B, some modifications of the model are required: (i) the multilayer panels of the roof have mechanical properties with orthotropic behavior taken from the technical datasheets of the manufacturer; (ii) the roof panels are modeled with plate finite elements; (iii) roof connections are modeled as inelastic links with stiffness-degrading hysteretic behavior [38,48]; (iv) the inelastic properties of these links are derived from the mechanical characteristics of the steel stripe tributary width. Clearly, the geometry and the properties of the masonry elements, already defined in Section 4.1, do not change. Model C is based on the same settings as Model B, but with an over-stiff solution at the roof level. This configuration is obtained by changing the mechanical properties of the roof panels and the inelastic properties of the links. Nonlinear history analyses have been performed for all three models considering seven spectrum-compatible accelerograms, and the obtained results have been averaged.

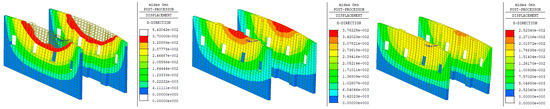

In terms of transverse displacement (Figure 11), it is helpful to first compare configurations A and B under the load combination, considering dead, live, and seismic loads according to [47] The transverse displacement in configuration A is 5.5 cm, higher than the target value assumed as 3.7 cm (equal to 0.5% the perimeter walls’ height), whereas the transverse displacement in configuration B is 3.5 cm, close to the target value. In configuration C, the displacement decreases to 2.5 cm. However, the displacement reduction from A to B is about 37%, better than the 25% obtained by passing from B to C.

Figure 11.

Transverse displacements [m]; on the (left): Model A; in the (middle): Model B; on the (right): Model C. Note: in the non-retrofitted configuration the transparent parts of the walls exceed the limit value of 3.7 cm.

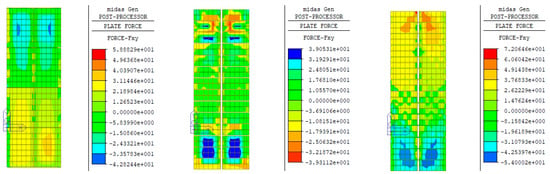

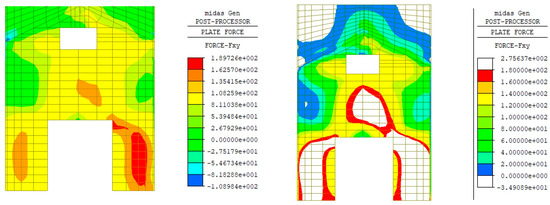

In terms of in-plane shear actions on the roof panels (Figure 12), comparing the three models: Configuration A shows about 42 kN/m, a value that exceeds the mechanical resistance of the original planks (33.3 kN/m for C16 wood class); Configuration B shows 39 kN/m, value that is compatible with the capacity of this kind of panel (48 kN/m [54,55,56]); Configuration C shows values close to 70 kN/m, thus implying an increase in panel thickness and a variation in the masses involved in the seismic event. Comparing the behavior of configurations B and C, the activation of the roof’s inelastic hinges occurs in B (Figure 13), resulting in energy dissipation, limitation of the transverse displacements, and acceptable values of the in-plane shear action. This kind of behavior also helps to limit the in-plane shear actions on the façade (Figure 14). In fact, for configuration B, the shear action on the façade reaches a maximum of about 189 kN/m and around 147 kN/m in the central part between the entrance and the opening. In contrast, in configuration C, these values increase by 46% and 41%, respectively, reaching 276 kN/m and 207 kN/m. It is worth noting that the shear resistance of the façade (with 70 cm thickness, medium quality stone masonry) can be evaluated at about 95 kN/m according to [47]. Therefore, reinforcement of the masonry is required in both configurations. However, in retrofitted configuration B, the intervention may be less invasive. It should also be noted that in the initial condition (Model A without the roof diaphragm), the in-plane shear demand on the façade was about 120 kN/m, in any case exceeding the allowable limit.

Figure 12.

In-plane shear on the roof panels [kN/m]; on the (left): Model A; in the (middle): Model B; on the (right): Model C.

Figure 13.

Activation status of the roof’s inelastic hinges of the roof (on the (left): model B; on the (right): model C). Note: blue color means the link remains in the elastic range; green color means the hinge status is in the plastic field.

Figure 14.

In-plane shear actions on the façade [kN/m] (on the (left): model B; on the (right): model C). Note: the white zones of model C represent the parts of the façade where the in-plane shear action is higher than the maximum value detected in model B.

4.4. Remarks

The nonlinear dynamic analyses performed by equivalent FEM allow the identification of possible retrofitted panel-to-panel connection configurations with significantly lower computational effort than a full 3D nonlinear model.

Once the timber panel technology is selected (in this case the phenolic multilayer panels), the connections’ configuration depends on the constitutive law of the inelastic shear hinges assigned to the roof elements in the equivalent FEM. The behavior of the shear hinges is influenced by the rotational hinge properties of the masonry through the hysteretic variable βHYS.

Using the Matlab procedure, the EDR can be computed and the retrofitted configuration that maximizes EDR can be identified. It should be noted that with this optimized configuration, the transverse displacement of the church can be reduced without significantly increasing the in-plane shear actions on the roof diaphragm.

The EDR graph as a function of the hysteretic variable clearly shows that excessively high values of βHYS should be avoided, as they lead to overly stiff configurations of the roof, thereby reducing the effectiveness of energy dissipation.

From Figure 7, the following observations can be made: (i) the maximum EDR value for the case study is 12%; (ii) beyond βHYS = 1.5, the EDR trend flattens and decreases; (iii) the maximum EDR occurs at the optimal value βHYS-opt = 1.2; (iv) beyond this optimal value, the transverse displacement curve tends to flatten.

Once the optimal hysteretic variable βHYS-opt is identified, the stiffness of the corresponding roof configuration can be calculated starting from the selected timber panel technology, number and layout of connectors, and dimensions of the steel stripes acting as cover plates.

When the features of the panels, connections, number, and dimensions of the steel stripes are known, the design criterion about energy dissipation requires that the steel stripes and connectors resist in-plane shear at the panel joints. However, to limit the overall displacement of the church and reduce the in-plane shear actions in the wood panels and masonry walls, the steel stripes should behave as a dissipative element. Therefore, for the realization of the roof’s elastic-plastic joints, the steel stripes should yield before the connectors. To facilitate the yielding of the steel stripes, they should be weakened by introducing notches between the adjacent rows of connectors.

In the 3D FEM, the steel connections are represented by inelastic springs (with an elastic-plastic stiffness-degrading hysteresis behavior) reflecting the configuration derived from the equivalent FEM. The 3D model is analyzed with the same seven spectrum-compatible accelerograms used for equivalent FEM analyses. It is important to underline that the computational effort of these analyses is not fully compatible with the typical time constraints associated with the development of a seismic retrofit project, particularly when multiple design scenarios need to be evaluated. Thus, the preliminary identification of the possible optimized configuration by using the equivalent model is suggested.

In the case study, the 3D model confirmed the validity of the connections’ configuration designed with the equivalent model. It showed that under transverse seismic action, energy dissipation occurs in the steel stripes close to the façade and head wall, as shown in Figure 13 (as for the output of the dynamic nonlinear analyses performed by equivalent FEM). Moreover, the maximum top displacement of the perimeter walls was reduced under the design limit (Figure 11) and the in-plane shear on the wood panels was compatible with the mechanical properties of the selected wood panels.

It is important to remark that the in-plane shear in the roof panels of the retrofitted configuration is higher than the corresponding shear of the initial configuration, where only the original planks are present (Figure 12). However, the original planks could not withstand these shear actions, leading to possible in-plane collapse of the planks and uncontrolled rocking of the walls of the church.

In summary, in the optimized retrofitted configuration, using phenolic wood panels and suitably weakened steel stripes, the transverse displacements are limited, and even if the in-plane shear actions increase, the corresponding stresses remain within the mechanical capacity of the wood panels thanks to the dissipative connections. Consequently, the in-plane actions on the façade are higher, though still limited, compared to the capacity of the masonry.

Analyzing the results of the case study, it is evident that equivalent FEM includes macro-components involved in the transverse nave response, specifically the masonry in its original condition and the roof in its retrofitted configuration. Nonlinear characteristics of both masonry and connections are modeled using inelastic hinges. The seismic response of the FEM is both qualitative, as it captures the overall structural behavior, and quantitative, as the design actions (displacements, shear forces, etc.) show only minor deviations from those obtained with the full 3D model. While a detailed nonlinear 3D model remains essential for the as-built design of the roof diaphragm, the equivalent FEM allows for early and fast optimization of retrofit solutions to be implemented in the time-consuming 3D analysis for final checks. Further refinement could involve modeling the masonry with solid elements and assigning different nonlinear constitutive laws based on laboratory testing.

Moreover, equivalent FEM enables efficient nonlinear dynamic analyses of dissipative roof solutions, requiring minimal computational effort. Its flexibility allows for practical application across various case studies for several different retrofit configurations. However, implementation constraints may arise if the standard wood panel dimensions do not match the roof geometry. Consequently, customized configurations could increase costs. Similarly, an excessive number of connection stripes per bay or connectors per stripe may affect construction time and economic viability. These aspects can be anticipated and optimized during the design phase using the equivalent model and checking the equivalent stiffness of the roof.

As an alternative to phenolic panels, cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels may be adopted, increasing the diaphragm’s stiffness. This choice leads to higher thickness panels and weight because the minimum thickness for CLT panels is averagely 6 cm. Consequently, notable differences should be present in terms of connection requirements and geometry of the weakening along the panel-to-panel connection stripes. CLT panels offer higher rigidity and require fewer connections, reducing installation time but increasing the unit cost of the structure. Phenolic panels, being lighter and more flexible, demand more connection stripes and connectors. These trade-offs can be anticipated and balanced during the design phase by checking alternative configurations with the proposed equivalent model.

5. Conclusions

A procedure to optimize roof retrofit intervention with the aim of improving the nave transverse response of one-nave historical churches is presented. The EDR evaluation is performed by a Matlab routine that uses the results obtained from dynamic nonlinear analyses carried out by the implementation of an equivalent FEM, considering the damping and the maximum strain energies of the inelastic hinges present in the equivalent FEM. The retrofitted configuration of the roof, designed with the equivalent FEM, is also validated with a 3D FEM showing the same improvements in terms of reduction of the maximum transverse displacement and limitation of the stresses on the roof’s wood panels. The improvement of the structural behavior of the church depends on the energy dissipation occurring in the elastic-plastic connections of the roof, specifically in the steel stripes of the panel-to-panel connections. The dimensions of the steel stripes are defined by assuming that the steel stripes yield when the connectors and the wood panels are still in the elastic field. Thus, the following remarks can be highlighted:

- The nonlinear dynamic analyses performed with the equivalent model allow for the identification of optimal panel-to-panel connection configurations, with reduced computational effort compared to full 3D nonlinear simulations;

- The execution time required for full nonlinear 3D analyses is not fully compatible with the typical time constraints of seismic retrofit design workflows, especially when multiple configurations should be tested. Without preliminary investigations using the equivalent model, the iterative design process would become impractical in real-world engineering contexts;

- The use of the equivalent model proves essential in the early stages of design, enabling rapid screening of alternative connection strategies. This approach significantly reduces the computational burden and supports informed decision-making before performing detailed 3D simulations;

- Localized notches between connectors are introduced to reduce the stiffness of the steel stripes, enabling plastic deformation under the design shear force of the connector. The number of connection stripes is determined iteratively, balancing seismic performance and technological feasibility;

- The full 3D model confirms the effectiveness of the equivalent model, showing dissipation concentrated near the roof ends, reduced mid-span displacement, and in-plane shear values compatible with the mechanical properties of the selected panels;

- Compared to the initial condition (roof with simple planks), the retrofitted system increases in-plane shear capacity of the roof while reducing transverse displacement, preventing uncontrolled rocking and out-of-plane mechanisms of the perimeter walls of the church. Therefore, the roof works a ductile diaphragm;

- The advantage of the energy-based design approach also lies in a retrofitted configuration able to maximize EDR and avoid over-stiff and overstrength solutions, limiting the shear transferred from the roof diaphragm to the façade and head wall.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L., P.C. and L.C.; methodology, N.L., P.C. and L.C.; validation, N.L. and P.C.; formal analysis, N.L. and P.C.; investigation, N.L. and L.C.; data curation, N.L. and P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L. and P.C.; writing—review and editing, N.L., P.C. and L.C.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, N.L., P.C., and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A. Franchi from Politecnico di Milano for the contribution to the successful completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pantò, B.; Cannizzaro, F.; Cademmi, S.; Caliò, I. 3D macro-element modelling approach for seismic assessment of historical masonry churches. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2019, 97, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, G.; Lourenço, P.; Tralli, A. Homogenization Approach for the Limit Analysis of Out-of-Plane Loaded Masonry Walls. J. Struct. Eng. 2006, 132, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longarini, N.; Crespi, P.; Zucca, M. The influence of the geometrical features on the seismic response of historical churches reinforced by different cross lam roof-solutions. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 6813–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, R.; Sofi, A.; Milani, G. Seismic Vulnerability of San Giovannello Church: An Advanced Limit Analysis Approach. In Proceedings of the 18th International Brick and Block Masonry Conference, Birmingham, UK, 21–24 July 2024; pp. 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, G.; Valente, M. Failure analysis of seven masonry churches severely damaged during the 2012 Emilia-Romagna (Italy) earthquake: Non-linear dynamic analyses vs conventional static approaches. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2015, 54, 13–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giresini, L. Energy-based method for identifying vulnerable macro-elements in historic masonry churches. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 14, 919–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giresini, L.; Solarino, F.; Taddei, F.; Mueller, G. Experimental estimation of energy dissipation in rocking masonry walls restrained by an innovative seismic dissipator (LICORD). Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 19, 2265–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Altri, A.M.; Sarhosis, V.; Milani, G.; Rots, J.; Cattari, S.; Lagomarsino, S.; Sacco, E.; Tralli, A.; Castellazzi, G.; Miranda, S. Modeling Strategies for the Computational Analysis of Unreinforced Masonry Structures: Review and Classification. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2020, 27, 1153–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelillo, M.; Lourenço, P.B.; Milani, G. Masonry behaviour and modelling. In Mechanics of Masonry Structures; CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences; Angelillo, M., Ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2014; Volume 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, M.; Reccia, E.; Longarin, N.; Cazzani, A. Seismic Assessment and Retrofitting of an Historical Masonry Building Damaged during the 2016 Centro Italia Seismic Event. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, V.; Casagrande, D.; Cimini, C.; Follesa, M.; Sciomenta, M.; Spera, L.; Fragiacomo, M. Simplified Strategies for the Numerical Modelling of CLT Buildings Subjected to Lateral Loads. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2021), Santiago, Chile, 9–12 August 2021; pp. 1660–1666. Available online: https://iris.unitn.it/handle/11572/401659 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Gavric, I.; Fragiacomo, M.; Ceccotti, A. Cyclic behavior of typical screwed connections for cross-laminated (CLT) structures. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2015, 73, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spera, L.; Sciomenta, M.; Bedon, C.; Fragiacomo, M. Out-of-plane strengthening of timber floors with CLT panels. Buildings 2024, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, R.; Crosatti, A.; Piazza, M. Theoretical and experimental analysis of timber-to-timber joints connected with inclined screws. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisio, A.; Pasca, D.P.; De Santis, Y.; Fragiacomo, M.; Ljungdahl, J. Assessing the deformation energy of timber-to-timber inclined screw connections via computed tomography scan. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2024, 82, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldin, G.; Fragiacomo, M. A Component Model for Cyclic Behaviour of Wooden Structures. In Materials and Joints in Timber Structures; Aicher, S., Reinhardt, H.W., Garrecht, H., Eds.; RILEM Bookseries; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remus, A.; Tezcan, S.; Sun, J.; Milani, G.; Perucchio, R. Seismic failure assessment using energy outputs of finite element analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszczak, S.; Przecherski, P. Macro-mesoscale submodeling approach for analysis of large masonry structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, A.; Massimilla, A.; Formisano, M.; Milani, G. Simplified Numerical Modelling of Structural Units into Masonry Building Compounds: An Equivalent Frame Method Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 10th International Masonry Conference, Milan, Italy, 9–11 July 2018; pp. 1684–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Cattari, S.; Calderoni, B.; Caliò, I.; Camata, G.; de Miranda, S.; Magenes, G.; Milani, G.; Saetta, A. Nonlinear modeling of the seismic response of masonry structures: Critical review and open issues towards engineering practice. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 1939–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATC-40; Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Concrete Buildings. Applied Technology Council: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1996. Available online: https://tanbakoochi.com/File/www.tanbakoochi.com-ATC40.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- FEMA 356; Prestandard and Commentary for the Seismic Rehabilitation of Buildings. Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. Available online: https://www.atcouncil.org/pdfs/FEMA356toc.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Schiavoni, M.; Giordano, E.; Roscini, F.; Clementi, F. Numerical modeling of a majestic masonry structure: A comparison of advanced techniques. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.A.; Piazza, M. Seismic Strengthening and Seismic Improvement of Timber Structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 97, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirra, M.; Ravenshorst, G. Optimizing Seismic Capacity of Existing Masonry Buildings by Retrofitting Timber Floors: Wood-Based Solutions as a Dissipative Alternative to Rigid Concrete Diaphragms. Buildings 2021, 11, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arenzo, G.; Casagrande, D.; Werner, S. Rigid or flexible? A numerical investigation on the in-plane behavior of CLT floor diaphragms. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE), Santiago, Chile, 9–12 August 2021; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11572/401662 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Mirra, M.; Ravenshorst, G. A seismic retrofitting design approach for activating dissipative behaviour of timber diaphragms in existing unreinforced masonry buildings. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Structural Engineering, Mechanics and Computation, 2022, Cape Town, South Africa, 5–7 September 2022; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 1901–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, P.B. Computational Strategies for Masonry Structures. 1996. Available online: https://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:4f5a2c6c-d5b7-4043-9d06-8c0b7b9f1f6f (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Milani, E.; Milani, G.; Tralli, A. Limit analysis of masonry vaults by means of curved shell finite elements and homogenization. IJSS 2008, 45, 5258–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubana, A.; Melotto, M. Evaluation of Timber Floor In-Plane Retrofitting Interventions on the Seismic Response of Masonry Structures by DEM Analysis: A Case Study. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 19, 6003–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longarini, N.; Crespi, P.; Zucca, M.; Scamardo, M. Numerical evaluation of the equivalent damping ratio due to dissipative roof structure in the retrofit of historical churches. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuriani, E.P.; Marini, A.; Preti, M. Thin-Folded Shell for the Renewal of Existing Wooden Roofs. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2016, 10, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, M.; Bolis, V.; Giuriani, E.; Marini, A.; Peretti, M. Studio Del Ruolo Del Diaframma Di Copertura Nel Comportamento Sismico Degli Archi Diaframma Nella Chiesa Parrocchiale Di Sirmione; Technical Report n. 1; Università di Brescia: Brescia, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1995-1-1; Eurocode 5—Design of Timber Structures—General—Common Rules and Rules for Buildings. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2004; 144. Available online: https://www.phd.eng.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/en.1995.1.1.2004.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Giuriani, E.; Marini, A. Wooden Roof Box Structure for the Anti-Seismic Strengthening of Historic Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2008, 2, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciola, P.; Deodatis, G. A Method for Generating Fully Non-Stationary and Spectrum-Compatible Ground Motion Vector Processes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iervolino, I.; Galasso, C.; Cosenza, E. REXEL: Computer Aided Record Selection for Code-Based Seismic Structural Analysis. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2010, 8, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.; Zhao, Y. Seismic Force Modification Factors for Modified-Clough Hysteretic Model. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 3053–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwan, W.D.; Gates, N.C. The Effective Period and Damping of a Class of Hysteretic Structures. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1979, 7, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Homeland Security. FEMA 440: Improvement of Nonlinear Static Seismic Analysis Procedures; Department of Homeland Security: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://mitigation.eeri.org/wp-content/uploads/fema-440.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Jacobsen, L.S. Steady Forced Vibrations as Influenced by Damping An Approximate Solution of the Steady Forced Vibration of a System of One Degree of Freedom Under the Influence of Various Types of Damping. J. Fluids Eng. 1930, 52, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, L. Damping in Composite Structures. In Proceedings of the 2nd World Conference on on Earthquake Engineering, Tokyo and Kyoto, Japan, 11–18 July 1960; Volume 2. Available online: https://engineering.purdue.edu/~ce573/Documents/Damping%20in%20composite%20structures_Jacobsen.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Jennings, P.C. Equivalent Viscous Damping for Yielding Structures. J. Eng. Mech. Div. 1968, 94, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmenshawi, A.; Sorour, M.; Mufti, A.; Jaeger, L.G.; Shrive, N. Damping Mechanisms and Damping Ratios in Vibrating Unreinforced Stone Masonry. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 3269–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midas GEN 2023. Available online: https://support.midasuser.com/hc/en-us/articles/27773333780761--GEN-2023-v1-1-Release-Note (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- MATLAB, version 2022a; The MathWorks Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2022.

- NTC2018; Italian Ministry of Infrastructures. Norme Tecniche per Le Costruzioni. DM 17/1/2018. Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana: Rome, Italy, 2018. Available online: https://biblus.acca.it/download/norme-tecniche-per-le-costruzioni-2018-ntc-2018-pdf/ (accessed on 30 January 2025). (In Italian)

- Clough, R.W. Effect of Stiffness Degradation on Earthquake Ductility Requirements; UC Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1966; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/21f175hg (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Dataholz.eu. OSB—Oriented Strand Board: Technical Properties and Product Data Sheets; Holzforschung Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.dataholz.eu/fileadmin/dataholz/media/baustoffe/Datenblaetter_de/osb_de_01.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Johansen, K.W. Theory of Timber Connections; IABSE: International Association of Bridge and Structural Engineering: Zurich, Switzerland, 1949; Volume 9, Available online: https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=bse-me-001%3A1949%3A9%3A%3A292 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Hossain, A.; Lakshman, R.; Tannert, T. Shear Connections with Self-Tapping Screws for Cross-Laminated Timber Panels. In Proceedings of the Structures Congress 2015, Portland, OR, USA, 23–25 April 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss, C.; Hossain, A.; Tannert, T. Simple Cross-Laminated Timber Shear Connections with Spatially Arranged Screws. Eng. Struct. 2018, 173, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1993-1-8; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Design of Steel Structures—Design of Joints. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2005. Available online: https://www.phd.eng.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/en.1993.1.8.2005-1.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- EN 12369-1:2001; Wood-Based Panels for Use in Construction—Characteristic Values for Structural Design. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2001. Available online: https://www.intertekinform.com/preview/2001000486393.pdf?sku=871935_saig_nsai_nsai_3731552&srsltid=AfmBOoo83fbUFDDhzPhKUWr2WhSaBixTFraM8Y69tGA70iQPs1lg3-gW (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- EN 13986:2004+A1:2015; Wood-Based Panels for Use in Construction—Characteristics, Evaluation of Conformity and Marking. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2015. Available online: https://www.internationalplywood.nl/static/uploads-cms2/EN_13986-2004A1-2015.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- EN 789:2004; Timber Structures—Test Methods—Determination of Mechanical Properties of Wood-Based Panels. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2004. Available online: https://zjz.njfu.edu.cn/DFS//file/2022/07/21/20220721164024580zie9eb.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).