1. Introduction

The construction of large-scale structures on soft clay deposits remains one of the most challenging geotechnical problems due to excessive settlement and potential instability in both the short and long term [

1]. Soft clays are naturally sensitive, highly compressible, and possess low shear strength, leading to significant total and differential settlements [

2]. Advances in ground improvement technologies have introduced numerous techniques to enhance the mechanical behavior of such soils, with over forty-six (46) methods identified and classified based on soil characteristics, application, and improvement mechanism [

3,

4,

5].

Among these, the Deep Soil Mixing (DSM) technique has been widely adopted to improve soft, compressible soils. Originating in Japan and Sweden during the 1960s, DSM involves in situ mixing of soil with a stabilizing binder, typically cement or lime, to form soil–cement columns with enhanced strength and stiffness [

6,

7,

8]. The method, introduced in the United States in 1986, is now widely practiced in Japan, the U.S., the Scandinavian countries, China, and South Korea, though its use in Europe remains limited [

7]. Two main variants exist: the wet method, in which cement slurry is injected to improve workability in very soft clays, and the dry method, which relies on natural soil moisture and is suitable for silty or organic deposits [

5].

DSM effectively improves shear strength, stiffness, and bearing capacity, while reducing compressibility and settlement [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Settlement behavior in soft clays is a significant design concern, as excessive deformation can compromise serviceability and structural integrity [

1]. Settlement evaluation commonly relies on field monitoring, laboratory testing, and numerical or analytical modeling [

12,

13]. A thorough understanding of immediate settlement is crucial for accurately interpreting and forecasting the subsequent long-term behavior of the ground, as initial deformations frequently dictate later stability and recovery patterns. Analytical and semi-empirical methods, such as the Priebe approach and unit-cell models, provide simplified estimates for composite ground systems [

14].

Several analytical approaches have been proposed to predict the settlement of DSM-improved soft clays. Classical formulations, such as Priebe’s improvement factor method, provide rapid preliminary estimates based on area replacement and stress concentration principles, assuming an elastic, uniform response. The unit-cell homogenization concept treats the treated ground as a composite medium to estimate immediate settlement and load sharing; however, its accuracy decreases when yielding or interface slip occurs [

14]. Composite decomposition models extend this framework by separating the soil and column domains to capture nonlinear behavior and imperfect bonding, thereby increasing input requirements but yielding a more realistic representation of the composite system [

6]. Semi-empirical and Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)-based procedures combine analytical correlations, unit-cell mechanics, and field observations to produce conservative, practice-oriented predictions. However, they remain limited when applied to complex geometries [

15]. All of these methods rely on idealized soil behavior. In contrast, finite element (FE) analysis with advanced constitutive laws, for example, the Hardening Soil Model, provides higher fidelity at the cost of extensive calibration and computational effort [

13,

15].

In parallel, rheological studies on granular materials have shown that their time-dependent deformation under dynamic loading is strongly influenced by packing density and state evolution. Triaxial creep tests and state evolution modeling have demonstrated the existence of a critical packing fraction separating rapid failure from stabilized logarithmic creep, which highlights the complexity of long-term deformation in granular layers subjected to repeated loading [

16].

Recent advances in computational geomechanics have demonstrated the strong capability of FEM to predict soil deformation and settlement with higher accuracy than traditional analytical formulations [

17,

18]. FEM accounts for nonlinear stress–strain response, complex boundary conditions, and layered ground systems that simplified analytical solutions cannot adequately represent. Large-scale three-dimensional simulations have shown that FEM can accurately capture soil deformability, foundation embedment effects, and composite ground behavior in DSM-improved profiles [

17].

Beyond quasi-static settlement problems, recent analytical studies have also addressed dynamic wave propagation in saturated porous media using seismic metasurfaces, where sub-wavelength resonators placed at the ground surface are modeled within an extended Biot-type framework to tailor Rayleigh wave propagation and mitigate ground-borne vibrations [

19]. These developments illustrate the level of sophistication that can be achieved in the modeling of saturated geomaterials when dynamic effects are of primary concern, which lies beyond the static framework considered in the present study.

In parallel, laboratory investigations on strip footings resting on heterogeneous or defective subsoils have shown that the load settlement response is highly sensitive to geometric and subsoil irregularities. For instance, laboratory tests on an eccentrically loaded strip footing above a single underlying void demonstrated that the footing capacity and settlement pattern change markedly with the position of the void and the load eccentricity, highlighting the complexity of soil structure interaction even for apparently simple shallow foundations [

20]. These findings are consistent with the present emphasis on complex settlement mechanisms in soft ground conditions, where composite reinforcement by DSM columns and non-uniform stress redistribution require more advanced predictive tools than conventional analytical formulas.

Recent studies have also highlighted the increasing integration of FEM-based numerical analyses with machine learning techniques, including multimodal or multi-source data fusion strategies [

21,

22,

23,

24]. These hybrid approaches aim to improve prediction accuracy and capture nonlinear soil structure interactions under complex configurations [

25,

26]. Collectively, these works confirm that FEM plays a central role in bridging analytical and data-driven methodologies such as Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), enabling fast and reliable settlement predictions through the combination of numerical and experimental datasets [

21,

22].

Despite extensive research, existing analytical and numerical approaches still exhibit apparent limitations in predictive capability and generalization when applied to DSM-improved soft clays [

14]. Analytical and semi-empirical formulations offer rapid estimates but are constrained by simplified assumptions about soil elasticity, uniformity, and ideal composite action, limiting their reliability in realistic field conditions. FEM-based analyses overcome many of these simplifications, but their practical use is often hindered by the need for rigorous calibration, high computational cost, and sensitivity to input uncertainty [

27,

28]. Data-driven approaches such as ANN and RSM have been introduced to address some of these limitations, yet most published studies rely on laboratory-scale datasets, simplified loading scenarios, and narrow parameter ranges, which limit their applicability to field-scale DSM systems [

28].

To develop a more representative predictive basis, the present study first calibrated the Hardening Soil Model using PLAXIS 2D simulations of a previously published triaxial test on Tunis soft clay, a material characterized by high compressibility and low shear strength [

10]. Numerical predictions were matched to experimental stress–strain behavior to ensure model consistency. The calibrated parameters were then used to construct a full-scale three-dimensional ground model measuring 120 m by 80 m by 20 m, incorporating a rigid pavement over DSM-improved clay. The parametric program included three column lengths (6, 12, and 20 m), three spacings (1.5D, 2D, and 2.5D), and two installation patterns (square and triangular), enabling a systematic evaluation of the immediate settlement response under realistic field conditions [

6,

7,

29,

30].

This large-scale numerical dataset was subsequently employed to develop and compare ANN and RSM models to assess their capability to reproduce nonlinear soil-column interactions and composite ground behavior beyond the simplified domains often reported in the literature [

31,

32]. The resulting framework provides a more robust, practically relevant basis for immediate settlement prediction in improved Tunis soft clay.

The present study aims to establish a comprehensive and reliable framework for predicting the immediate settlement of soft clay improved with DSM columns under heavy aircraft loading. The work focuses on quantifying the influence of key design variables, specifically column spacing, column length, and installation pattern, rectangular or triangular, on the resulting settlement response. Using high-fidelity numerical simulation datasets, the study develops and compares RSM and ANN predictive models to evaluate their ability to capture both linear and nonlinear soil-column interactions. The overarching objective is to identify the most suitable data-driven approach for accurate, efficient, and practice-oriented DSM design optimization in airport pavement foundations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geotechnical Characterization and Laboratory Testing of Tunis Soft Clay

The subsoil investigated in this study corresponds to the Tunis soft clay, a highly compressible marine deposit characterized by high natural water content, low undrained shear strength, and significant compressibility. These deposits, typical of Quaternary marine formations in coastal Tunisia, are encountered at approximately 7.5 m depth [

10].

The physical properties, including natural moisture content, unit weight, Atterberg limits, and specific gravity, were determined from laboratory tests on undisturbed samples [

10,

33,

34]. Mechanical parameters were obtained from consolidated undrained triaxial shear tests conducted by Frikha [

10] under confining pressures of 100, 150, and 200 kPa. From these tests, the undrained shear strength (Cu) and undrained friction angle (φu) were evaluated, while effective strength parameters (c′, φ′) were derived from the corresponding failure envelopes.

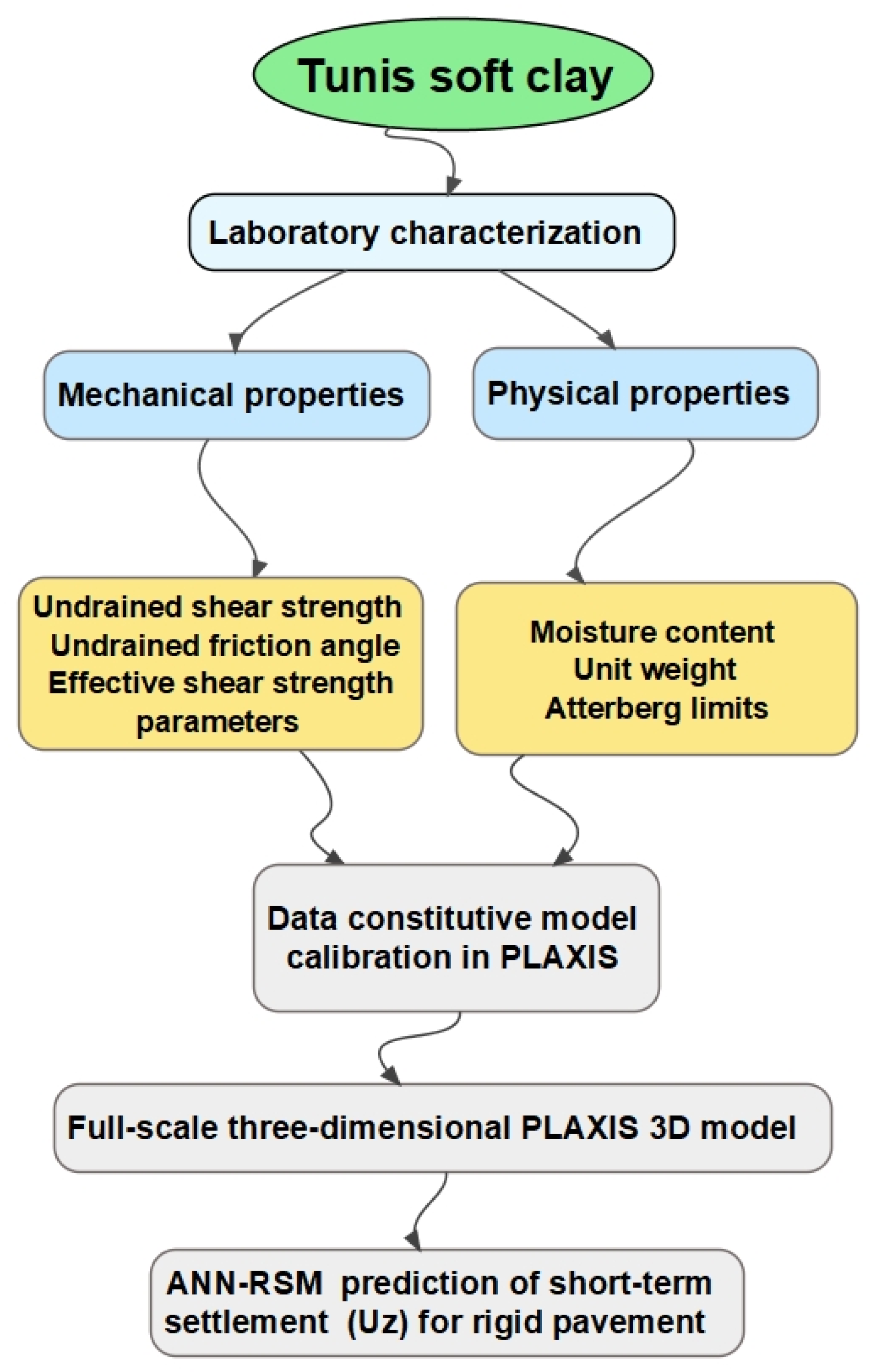

An experimental program was thus established to characterize the principal engineering properties of the Tunis clay. These results provided essential input for calibrating the constitutive model in PLAXIS 3D, ensuring that the numerical model accurately reproduced the soil’s laboratory behavior, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The basic physical and mechanical properties of the Tunis soft clay are summarized in

Table 1, which presents both the index parameters and shear strength characteristics obtained from laboratory testing.

2.2. Numerical Model Calibration and Full-Scale Simulation

The calibration of the constitutive model was performed to ensure that the numerical analysis could accurately reproduce the stress–strain behavior of the Tunis soft clay observed in laboratory testing

Table 1. The Hardening Soil Model (HSM) available in PLAXIS 3D was selected due to its ability to capture stress-dependent stiffness and nonlinear deformation of soft soils [

35,

36,

37].

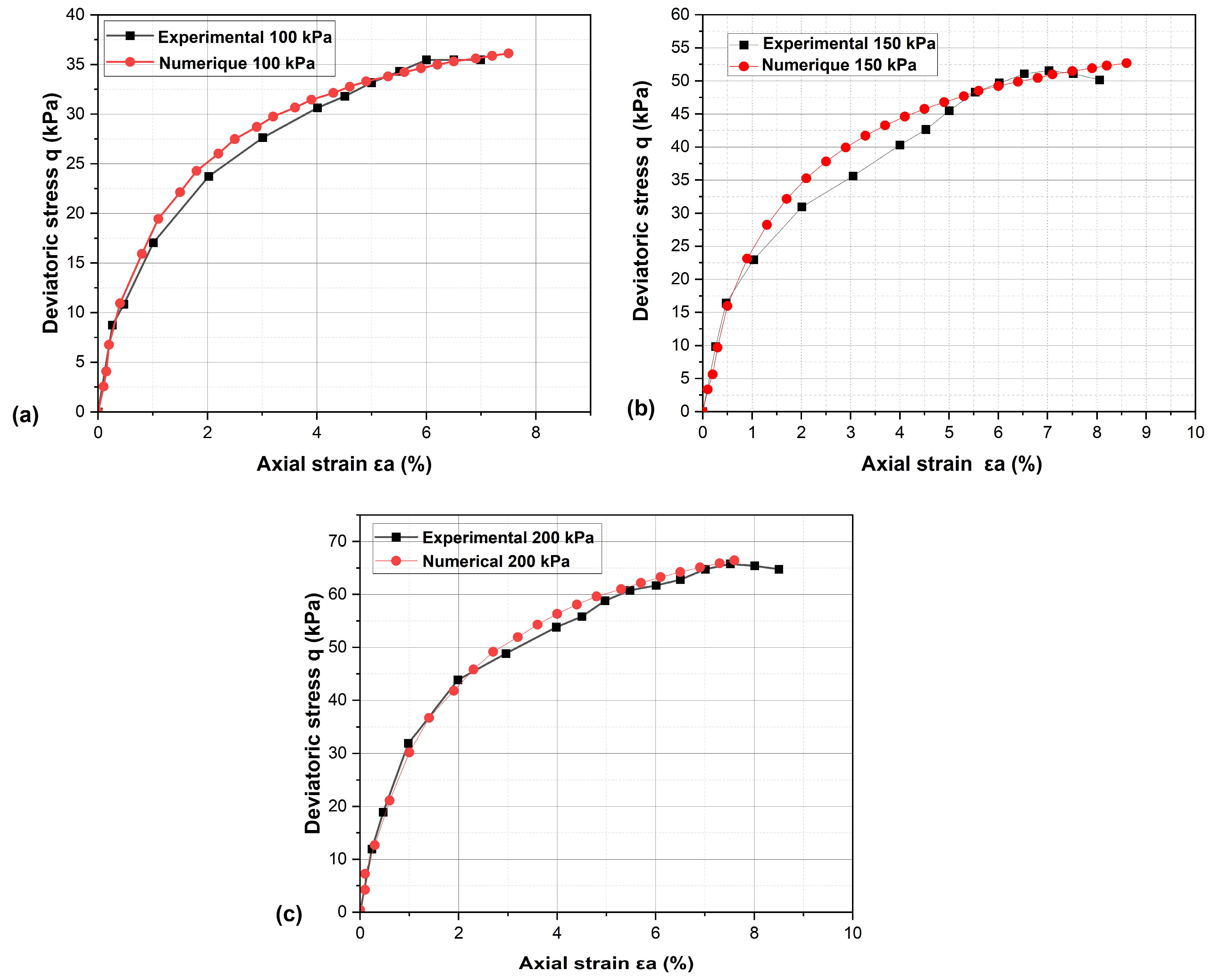

The consolidated undrained triaxial tests on Tunis clay conducted by Frikha [

10] at confining pressures of 100, 150, and 200 kPa were simulated numerically. Model parameters were iteratively refined until a close agreement between numerical and experimental responses was achieved. Special attention was given to the stiffness moduli (E

50ref, E

oed, E

ur) and to verifying the shear strength parameters (c′, ϕ′, Cu, ϕu). The comparison between laboratory and numerical stress–strain curves demonstrated excellent agreement, confirming the suitability of the calibrated parameters and the reliability of the HSM in reproducing the mechanical Response of Tunis soft clay. This agreement is illustrated in

Figure 2a–c, while the final calibrated parameters used in subsequent analyses are summarized in

Table 2.

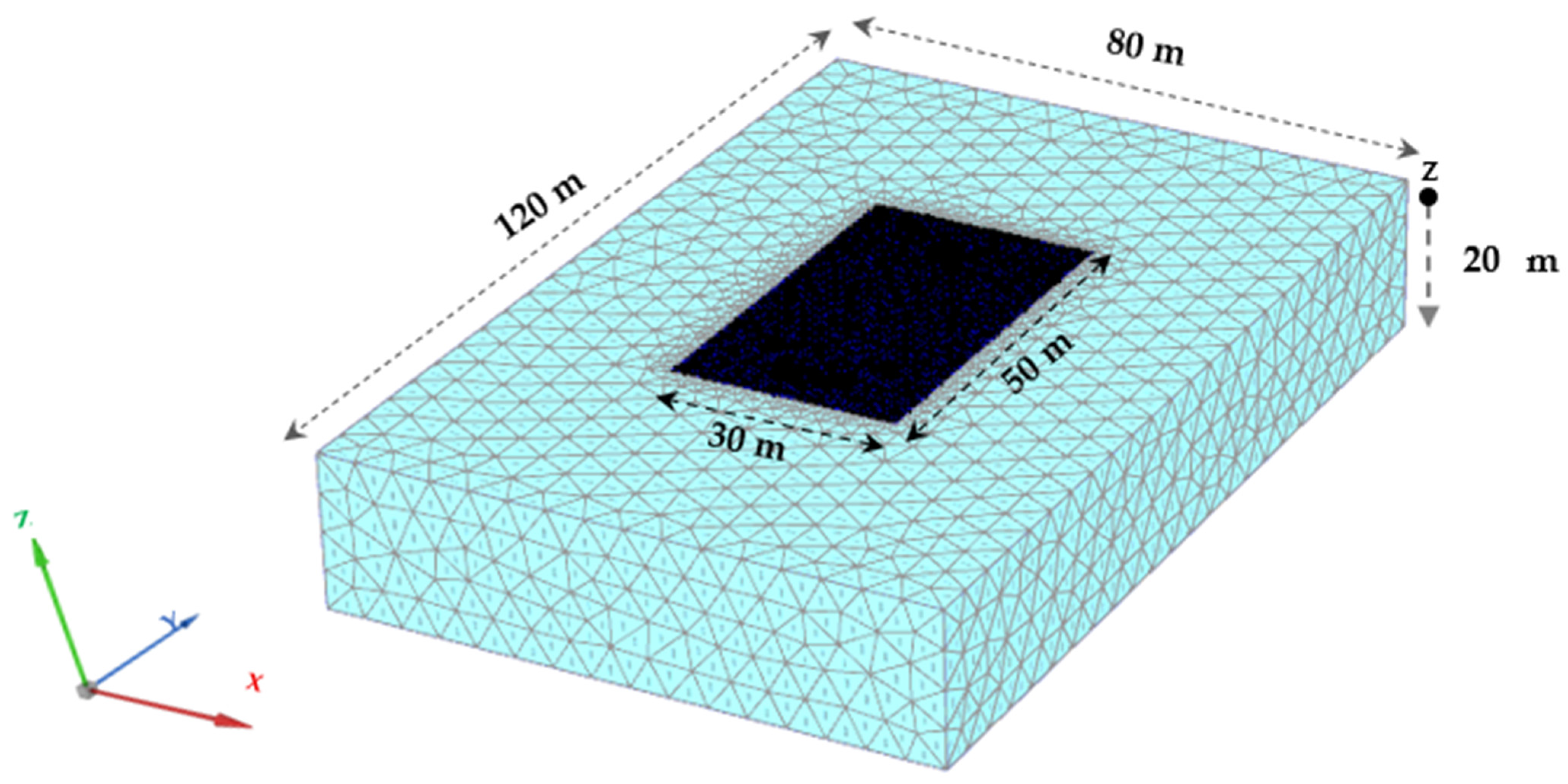

The calibrated parameters were then incorporated into a full-scale three-dimensional PLAXIS 3D model developed to simulate the Response of a rigid pavement founded on Tunis soft clay under representative aircraft loading [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] (see

Figure 3). The computational domain was idealized as a homogeneous soil mass measuring 120 m × 80 m × 20 m (length × width × depth) [

43,

44]. These dimensions ensured that stress and displacement fields dissipated well before reaching the lateral and basal boundaries, thus minimizing boundary effects and preserving realistic soil–pavement interaction [

44]. Beyond this domain size, further enlargement produces negligible (<2–3%) variation in computed immediate settlement, confirming adequacy of the adopted boundaries [

45,

46].

The upper boundary was modeled as a rigid pavement, represented by a 0.35 m-thick plate element measuring 50 m × 30 m (length × width). Interface elements were incorporated into the numerical model to simulate mechanical interaction at critical boundaries with appropriate realism. At the pavement–soil interface, the interface properties were assigned values consistent with those of the rigid pavement layer, and a reduction factor Rinter = 0.7 was applied to account for limited shear transfer. This ensured adequate stress transmission while preventing artificial deformation of the pavement layer [

47,

48]. A mesh sensitivity analysis showed that the maximum difference in predicted settlement between fine and very fine meshes was only 4.8%. Based on this result, a fine global mesh was adopted for the entire model, with a coarseness factor of 0.7, while a locally refined mesh with a reduced coarseness factor of 0.5 was applied beneath the pavement and around the DSM columns to capture stress concentrations and geometric variations with higher accuracy.

Boundary conditions followed standard practice: the basal boundary was fully fixed (Ux = Uy = Uz = 0) to prevent rigid-body motion, while vertical sides were constrained only in the normal direction (zero normal displacement on the yz and xz planes) and left free vertically to allow natural settlement. This configuration minimizes boundary interference and ensures numerical stability throughout the simulation.

2.3. DSM Columns

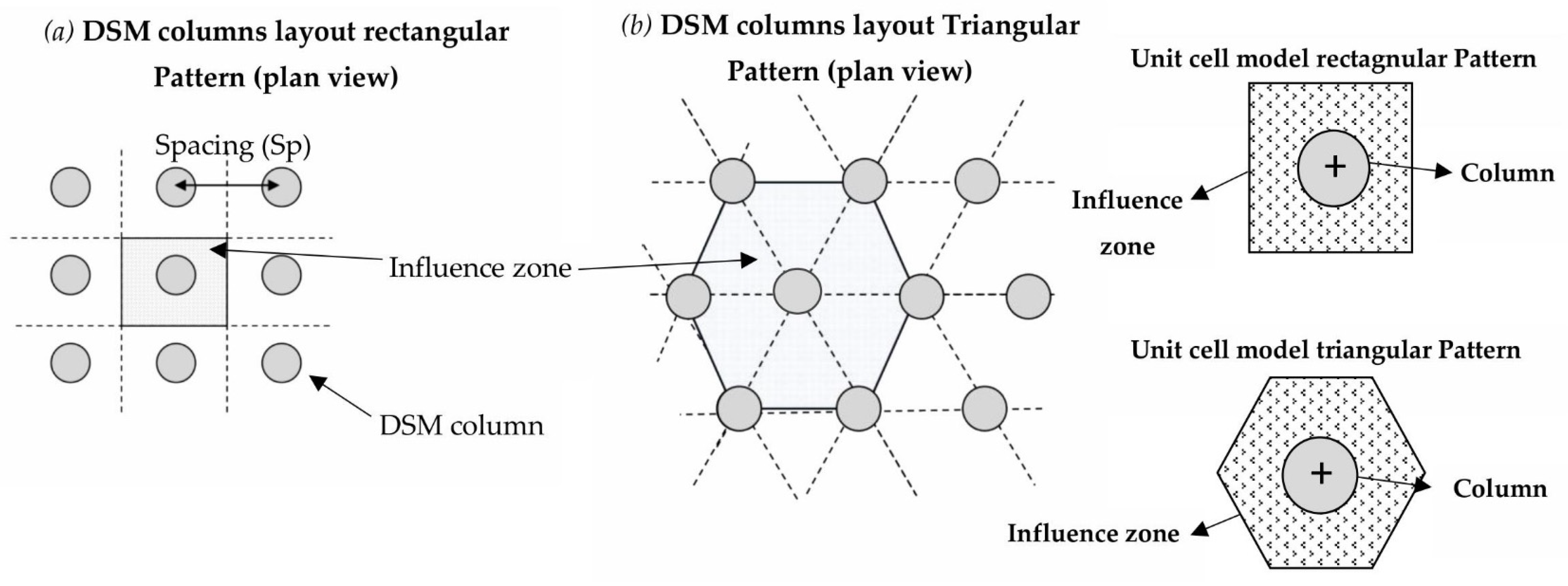

The DSM reinforcement was explicitly modeled as volume clusters embedded within the soft clay domain and positioned beneath the pavement. Columns were idealized as vertical cylinders with diameter (D) and length (L), installed either as floating inclusions within the clay or with toe embedment into the underlying stiff stratum, depending on the case. Two reinforcement layouts were examined—square and triangular grids—with center-to-center spacing (Sp.). The corresponding area-replacement ratios (Ar%) were computed as shown in

Figure 4, together with L/D and Sp/D ratios, which defined the parametric space of the study.

The selected column material was modeled using either a linear-elastic or Mohr–Coulomb constitutive law, with stiffness and strength parameters calibrated from cemented-soil data. The column Young’s modulus (Ec) was set to 100 × 10

3 kPa (≈100 MPa), a value within the commonly reported range for soil–cement columns of comparable binder content and curing conditions, as inferred from UCS–E

50 correlations in the literature [

49]. The surrounding clay was modeled using the calibrated Hardening Soil (HS) parameters summarized in

Section 2.2.

For the soil–column interface, relative slip was permitted, and the interface properties were derived from those of the surrounding soil using a reduction factor Rinter = 0.8, consistent with established practices for soil–concrete contact modeling. This approach ensures realistic load transfer, prevents numerical artifacts, and enhances the reproducibility of the numerical model.

Local mesh refinement was applied around the columns to resolve stress transfer and shear-band formation accurately.

The DSM column diameter was fixed at 1.50 m, consistent with established practice for heavy-duty soil–cement works where diameters of approximately 1.0–1.5 m are typically adopted [

6,

7,

8]. This choice enhances the area-replacement ratio and the composite stiffness contribution under pavement loads while remaining practical and constructible at the field scale.

2.4. Loading Conditions and Aircraft Loading Assumptions

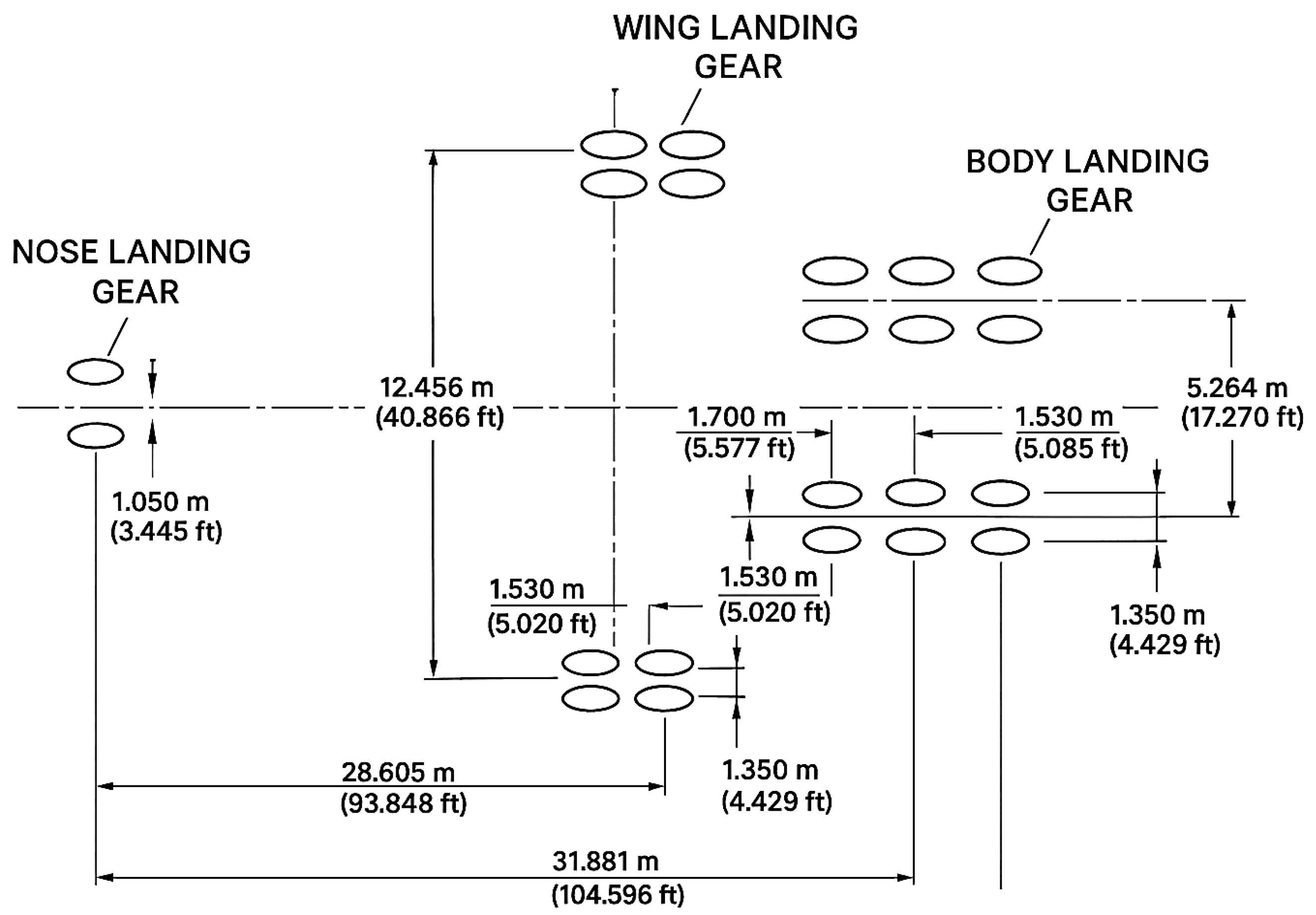

The rigid pavement was subjected to loading conditions representative of the Airbus A380-800, which features 22 wheels distributed across four landing-gear assemblies [

38]. The configuration includes two wheels on the nose gear, six wheels on each of the left and right body gears, and eight wheels on the wing gears. The system is symmetrical with respect to the aircraft centerline, ensuring balanced load transfer and uniform pavement response. A schematic illustration of this wheel configuration is presented in

Figure 5.

The Airbus A380 comprises several Weight Variants (WV), each with distinct operational limits for take-off, landing, taxi, and ramp, as reported in the official Aircraft Characteristics Manual [

50]. In this study, Weight Variant WV002 was selected. The Maximum Ramp Weight (MRW) of 571,000 kg represents the critical ground case corresponding to parking or taxiing with full fuel. Adoption of the MRW provides a conservative loading scenario that encompasses structure, payload, and fuel, thereby yielding a safety-biased assessment of pavement response.

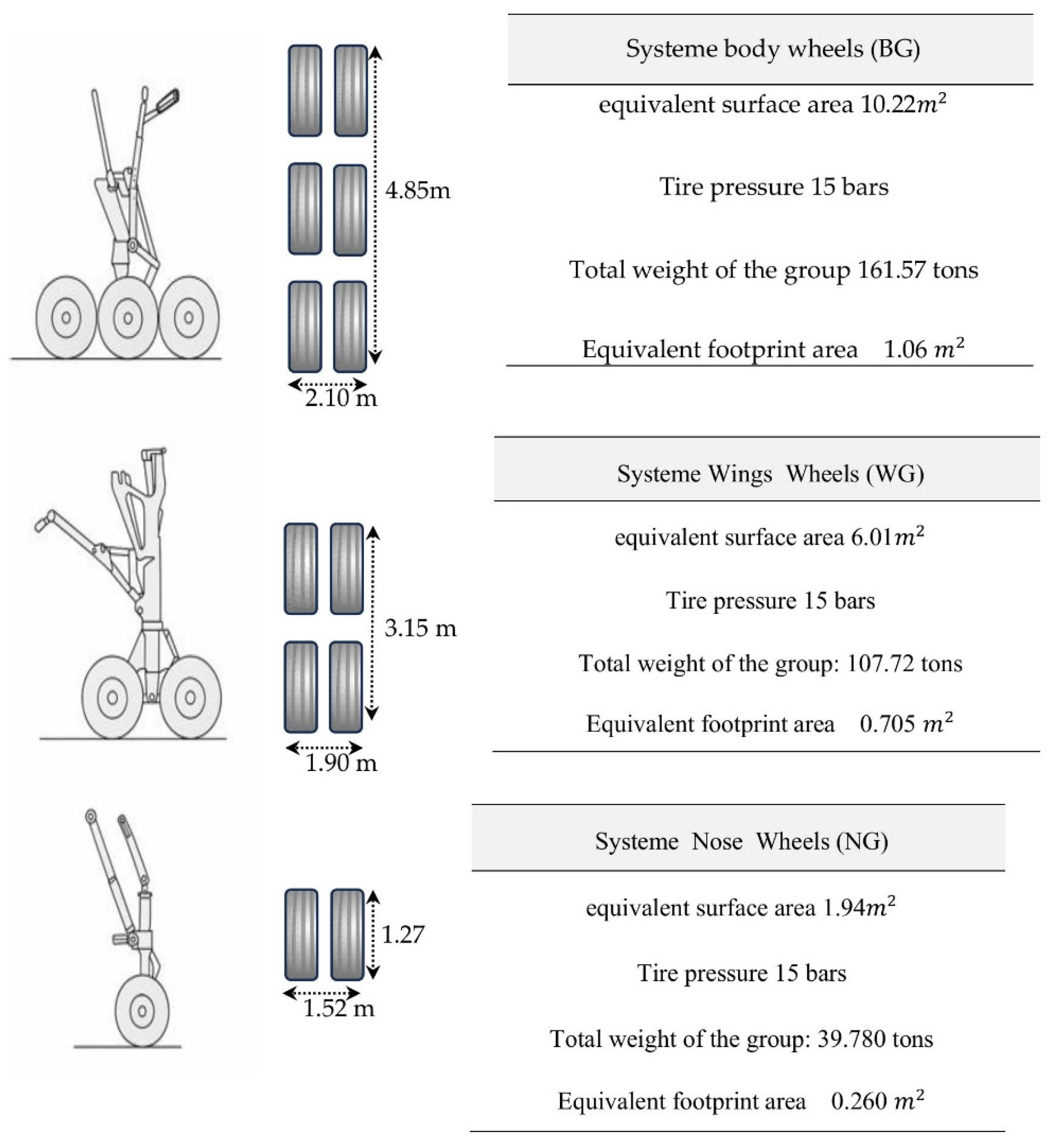

A uniform tire contact pressure (

P0) of 1.5 MPa was applied. This value aligns with the tire specifications for the A380-800—NZG radial tires, type 1400 × 530 R23 (40 PR) for the main gears and 50 × 20.0 R22 for the nose gear—which operate under a high-inflation regime of approximately 14–15 bar. On this basis, the equivalent footprint area (A

i) for each gear group was calculated from Equation (1).

where

Pi is the total load carried by the gear group, and

P0 is the uniform contact stress. For computational efficiency, all tires were modeled according to the certified NZG radial specifications, and a uniform contact pressure

P0 = 1.5 MPa was imposed. Within each gear group, multiple wheels were combined into a single rectangular equivalent loading zone that maintained the same resultant load and centroid. Consequently, five loading zones were defined: nose gear (NG), left body gear (BG-L), right body gear (BG-R), left wing gear (WG-L), and right-wing gear (WG-R).

This abstraction maintains the total load, symmetry, and planwise pressure distribution while simplifying the numerical model in PLAXIS 3D. The plan dimensions and contact areas of all gear groups are summarized in

Figure 6, and the corresponding five loading zones are depicted in

Figure 7.

2.5. Ground Improvement Configuration and Analysis Program

A parametric analysis program was developed to generate a dataset for Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) modeling. The simulations were based on the Airbus A380-800 (WV002) with a Maximum Ramp Weight (MRW) of 571,000 kg and a uniform contact pressure (P0 = 15 bar) applied over the five loading zones: nose gear (NG), left body gear (BG-L), right body gear (BG-R), left wing gear (WG-L), and right-wing gear (WG-R).

The geometry, boundary conditions, and soil parameters were kept constant in all analyses. The Deep Soil Mixing (DSM) design variables were varied as follows:

Pattern: Square and triangular.

Column spacing (Sp): 1.5D, 2.0D, and 2.5D.

Column length (L): 6 m, 12 m, and 20 m.

A full-factorial design (2 × 3 × 3) produced 18 simulation cases. For each case, the DSM layout was created in PLAXIS 3D, the area-replacement ratio (Ar%) was calculated, and the immediate (undrained) settlement phase was analyzed under the fixed aircraft load.

For each simulation, the maximum instantaneous settlement (Uz

max) beneath the pavement and the settlement contours were recorded (The 18 cases with Sp, L, and Uz results are listed in

Table 3). The resulting dataset (pattern, Sp/D, L/D, Ar%) → Uz

(ins) was used for RSM fitting and ANN training/validation.

2.6. Mathematical Modeling Approaches (RSM and ANN)

Two complementary data-driven approaches, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN), were applied to predict the settlement response (Uz) of the DSM-improved ground. Both methods used the dataset generated from the PLAXIS 3D simulations described earlier.

RSM is a statistical and mathematical technique used to model systems influenced by multiple variables and their interactions. Unlike simple regression, it captures both nonlinear and interaction effects, making it suitable for complex geotechnical systems. Structured experimental designs, such as factorial, central composite, and Box–Behnken methods, are often used to develop efficient empirical models while minimizing the number of simulations [

51,

52]. In this study, RSM was used to analyze the effects of DSM column spacing (2.25–3.75 m) and column length (6–20 m) on settlement (Uz). The response surface was represented by a second-order polynomial Equation (2):

where

Y is the Response,

B0 is the intercept, and

Bi,

Bii, and

Bij are the linear, quadratic, and interaction coefficients [

53,

54]. Model significance was tested by the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) using the F-distribution, with the Fisher–Snedecor test at a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05).

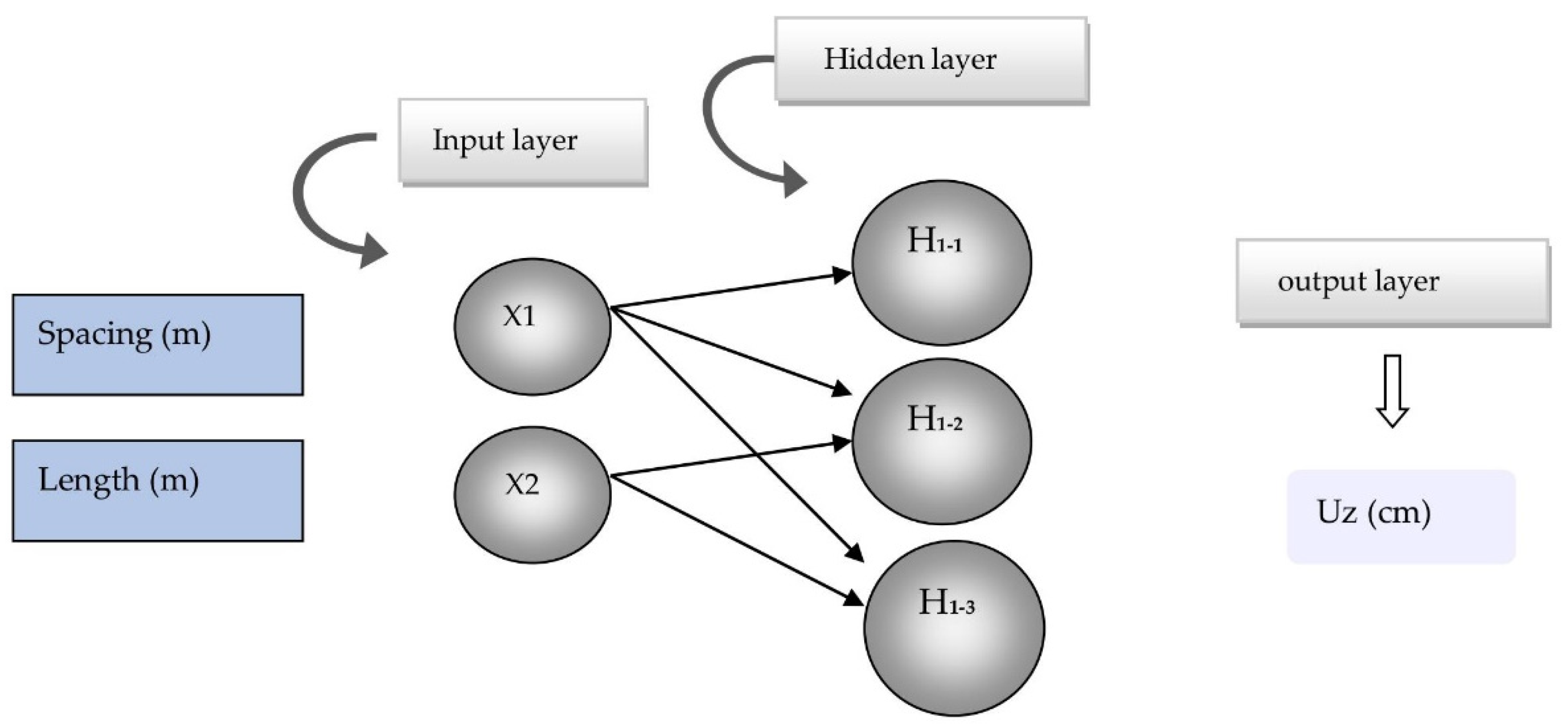

In parallel, a feedforward Artificial Neural Network (ANN) with a multilayer perceptron (MLP) architecture was developed to model the nonlinear relationship between column spacing, column length, and resulting settlement. The network structure included two input neurons representing the geometric parameters, a hidden layer with three neurons employing a Gaussian activation function, and an output neuron with a linear activation function for settlement prediction (

Figure 8). The model was implemented in JMP Pro 17, using a fixed learning rate of 0.01, L2 regularization, and early stopping based on validation error to prevent overfitting. The training employed backpropagation and was performed on a dataset generated by the Box–Behnken design of PLAXIS 3D simulations. Model performance was assessed using a three-fold cross-validation (k = 3) procedure, in which approximately two-thirds (≈67%) of the data were used for training and one-third (≈33%) for validation in each iteration. The process was repeated three times, with each subset used once for validation and twice for training, and the reported performance metrics correspond to the average across all folds. The selected configuration was determined after preliminary sensitivity analyses, which showed that increasing the number of hidden neurons or layers did not significantly improve accuracy but increased model variance. This efficient yet straightforward architecture provided stable convergence and reliable predictive performance.

The variables (Sp, L, and Uz) were used in their original scales due to their narrow and comparable magnitude ranges, which prevented numerical imbalance. Although no explicit normalization was applied, the optimizer still converged stably. It is recognized, however, that lack of normalization can slow convergence or slightly affect weight conditioning in larger datasets; this will be addressed in future work.

Both models were evaluated using statistical indicators, including R

2, RMSE, MAE, SSE, SI, and RPD (Equations (3)–(8)), which quantify the accuracy, robustness, and predictive performance of the models:

where n is the number of observations, y

i is the observed value, ŷ

i is the predicted value, and ȳ is the mean of the observations.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents and interprets the key outcomes of the numerical and data-driven analyses performed in this study. The results are analyzed in terms of the stress–strain behavior, deformation characteristics, and settlement response of Tunis soft clay under aircraft loading. Numerical simulations using the calibrated Hardening Soil Model (HSM) in PLAXIS 3D were first validated against laboratory data to confirm model reliability.

The subsequent predictive modeling phase employed two complementary approaches—Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN)—to estimate the immediate settlement of DSM-improved ground. The RSM model provided an interpretable statistical framework for identifying main and interaction effects among the key design variables: DSM column arrangement, spacing (Sp), and length (L). In contrast, the ANN model captured complex nonlinear interactions that extend beyond polynomial approximations. A comparative evaluation of both models against PLAXIS 3D reference data was then performed to assess prediction accuracy, statistical indicators, and each method’s capacity to reproduce observed settlement trends across various DSM configurations.

3.1. Response Surface Methodology for Settlement in DSM-Improved Soft Clays

Table 4 summarizes the statistical indicators of the response surface models for both rectangular and triangular column arrangements. The results show very high coefficients of determination (R

2 = 0.999678 and 0.999592, respectively) and adjusted R

2 values exceeding 0.9989, confirming that more than 99.9% of the variability in settlement response (Uz) is explained by the selected parameters. These results demonstrate the strong predictive capability and robustness of the RSM models for both layouts.

The mean settlement was slightly higher for the rectangular arrangement (7.26 cm) than for the triangular arrangement (6.81 cm), suggesting that the triangular grid provides more uniform reinforcement and more efficient stress transfer to the subsoil, thus reducing deformation in untreated zones. An equal number of data points (nine per case) ensures a balanced comparison and validates that performance differences stem primarily from geometric configuration.

The ANOVA results (

Table 5) confirmed that both models were statistically significant (

p < 0.0001), reinforcing the suitability of RSM for modeling the settlement response (Uz). In the rectangular pattern, column length (L) was the dominant factor (F = 8658.66,

p < 0.0001), reflecting that deeper DSM inclusions mobilize stiffer substrata and confine surrounding soil, thus minimizing settlement. Spacing (Sp) was also significant (F = 406.13,

p = 0.0003), as reduced spacing increases the composite stiffness of the treated zone. The quadratic term of L (F = 64.43,

p = 0.0040) revealed a nonlinear response: beyond a critical embedment depth, further increases in column length yield diminishing reductions in settlement. The significant Sp × L interaction (F = 22.27,

p = 0.0180) showed that the efficiency of longer columns improves with closer spacing.

In the triangular pattern, L again had the most substantial effect (F = 6424.94, p < 0.0001), while the impact of Sp was magnified (F = 674.45, p = 0.0001), reflecting the isotropic stress distribution and uniform confinement provided by triangular grids. The enhanced Sp × L interaction (F = 75.46, p = 0.0032) indicates that combining longer columns with closer spacing significantly amplifies the reduction in settlement. The nonsignificant quadratic term of Sp implies a near-linear Uz–Sp relationship within the studied range. In contrast, the consistent significance of L2 confirms that column depth primarily governs the nonlinear settlement response.

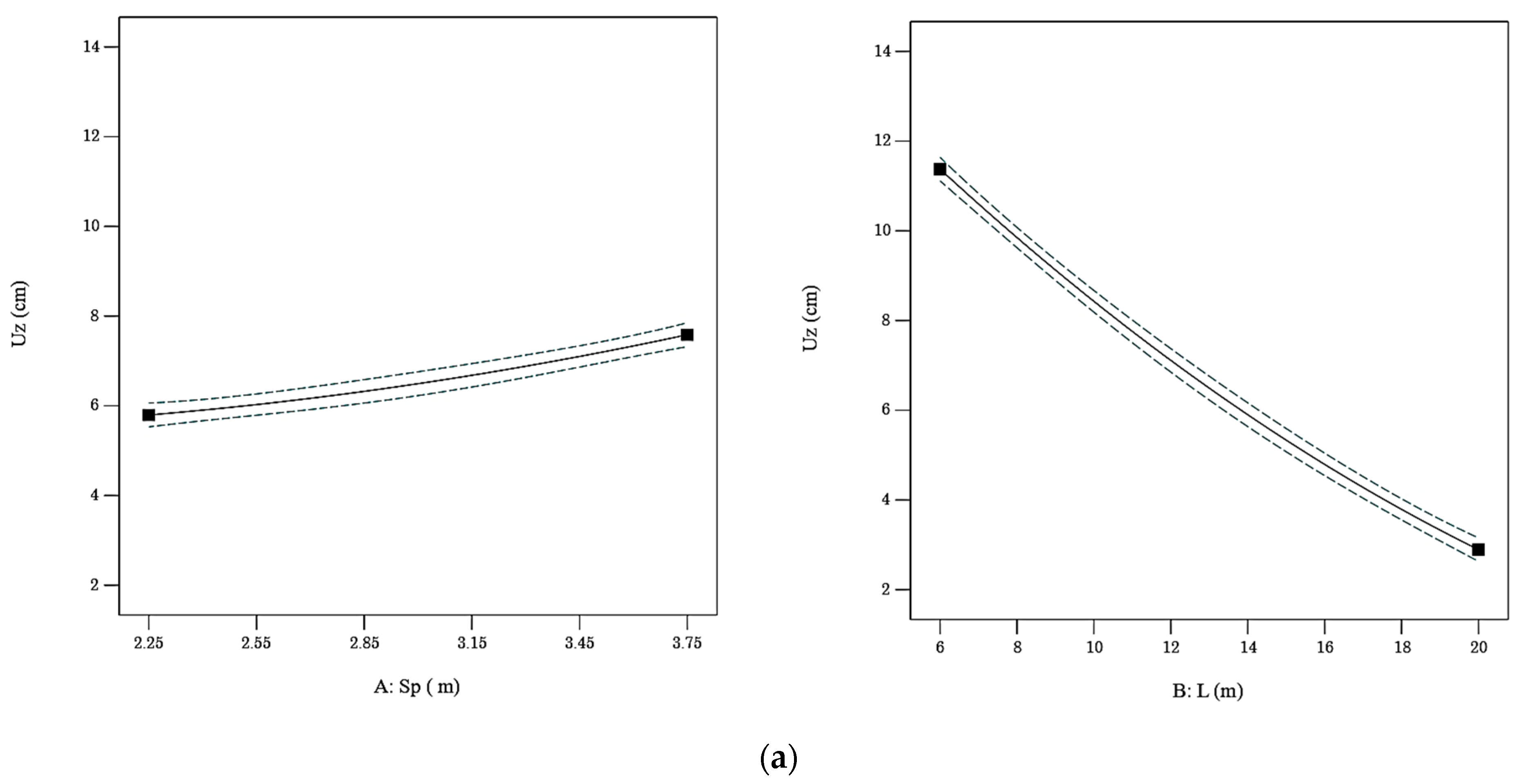

Both spacing (Sp) and column length (L) significantly influence settlement (Uz), though their effects vary with column arrangement. Increasing spacing led to a nearly linear increase in Uz, as wider intervals weaken the composite stiffness and leave untreated soft zones more prone to deformation (

Figure 9)—consistent with the findings of Kitazume and Terashi [

11] and Porbaha [

12]. This effect was more pronounced in the triangular pattern, whose uniform coverage makes closer spacing more effective for distributing loads evenly, as observed by Castro and Sagaseta [

55,

56].

Conversely, increasing column length produced a sharp, nonlinear reduction in Uz for both configurations, confirming the critical role of L in mobilizing deeper and stiffer layers, thereby enhancing confinement, in agreement with Horpibulsuk et al. [

57]. The triangular layout amplified this effect through its isotropic stress redistribution, enabling more efficient load transfer, as reported by Bahadori and Rayhani [

58,

59]. The mild curvature in the Uz–L relationship reflects diminishing returns beyond a critical length, consistent with previous studies on DSM-supported foundations [

60].

Overall, the triangular configuration yielded greater settlement reduction than the rectangular one for equivalent design parameters, owing to superior stress diffusion and load-sharing characteristics, in line with established soil mechanics principles and past research on composite ground reinforcement [

61].

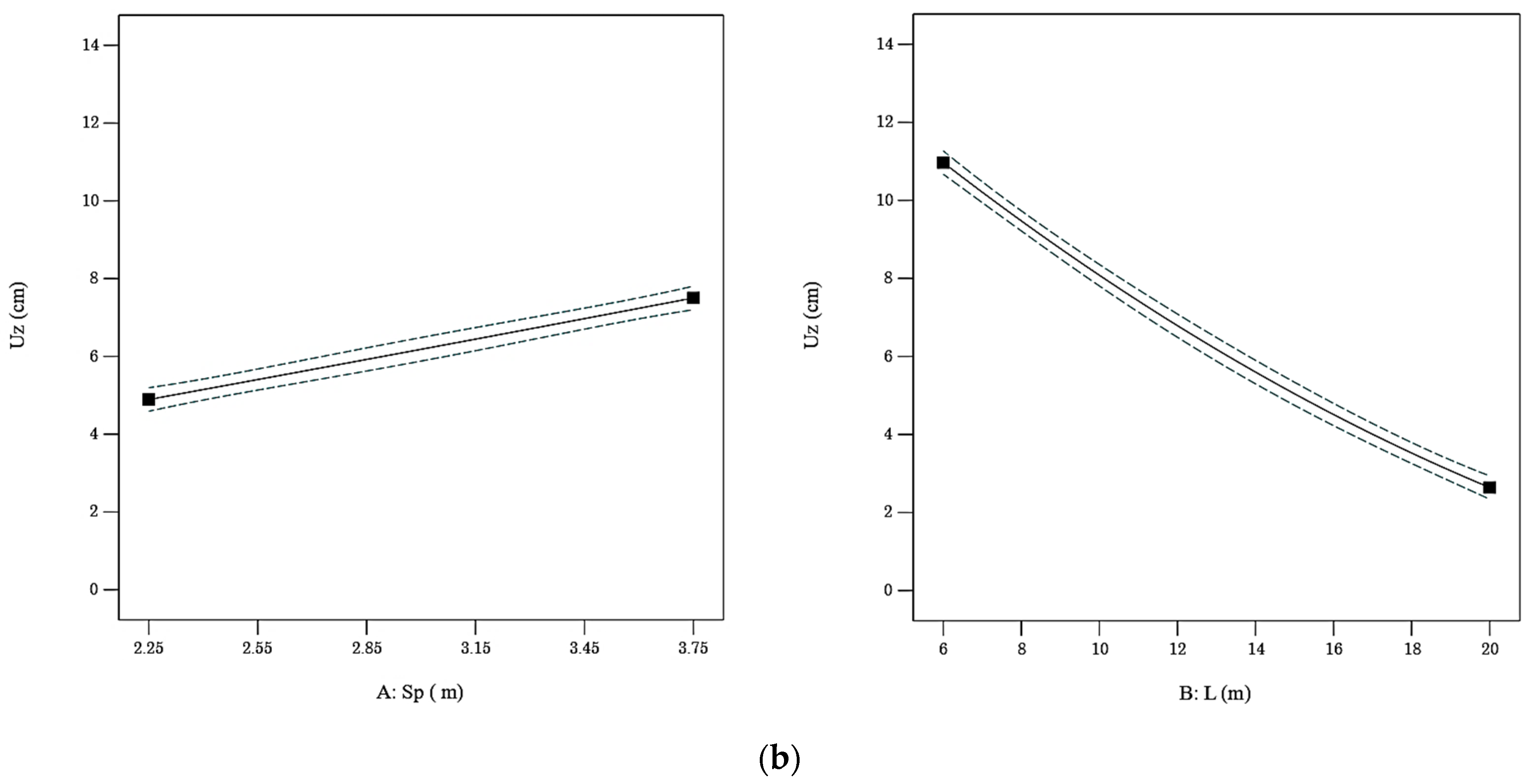

The interaction analysis (

Figure 10) revealed that the reduction in settlement (Uz) due to increased DSM column length (L) is strongly dependent on spacing (Sp) and arrangement. In the rectangular grid, longer columns are most effective when spacing is small, as closer spacing enhances composite stiffness and allows full mobilization of load-transfer capacity. At larger spacings, untreated clay governs deformation, reducing the effectiveness of longer columns.

In contrast, the triangular grid exhibited a stronger Sp × L interaction, where the combination of longer columns and tighter spacing produced a disproportionately larger decrease in Uz. This enhanced performance is attributed to the triangular grid’s isotropic load transfer and superior confinement of intervening clay zones. Consequently, triangular layouts consistently outperform rectangular ones, especially when both L and Sp are optimized, while their performance converges under wider spacing conditions. These findings are consistent with previous studies that emphasize the combined influence of geometry and spacing on DSM efficiency in soft ground improvement [

62,

63].

The predictive equations used to estimate Uz for both rectangular and triangular arrangements, derived from the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) using second-order polynomial models, are presented in Equations (4) and (5).

3.2. ANN K-Fold Cross-Validation for Settlement Prediction in DSM-Improved Soft Clays

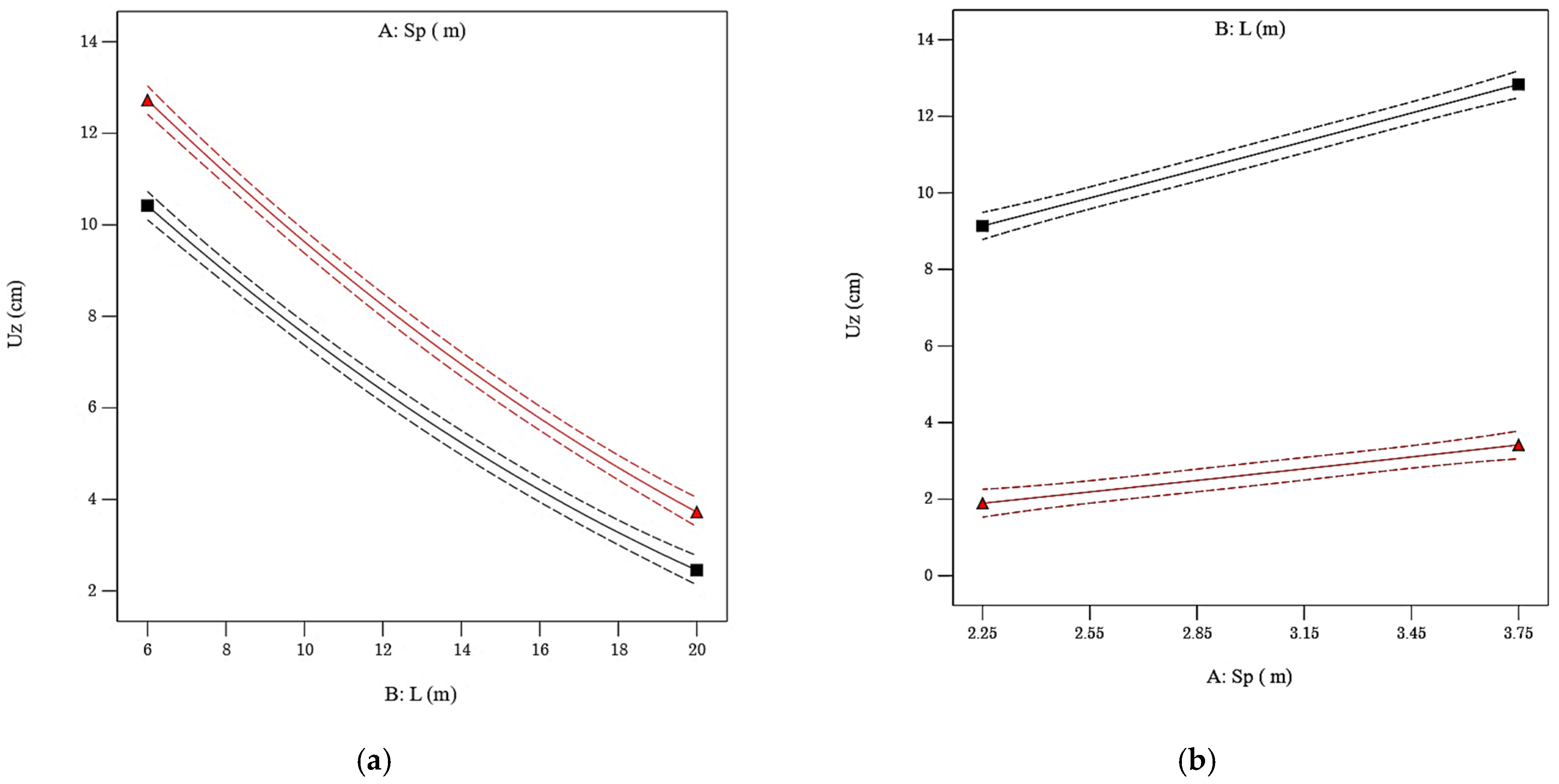

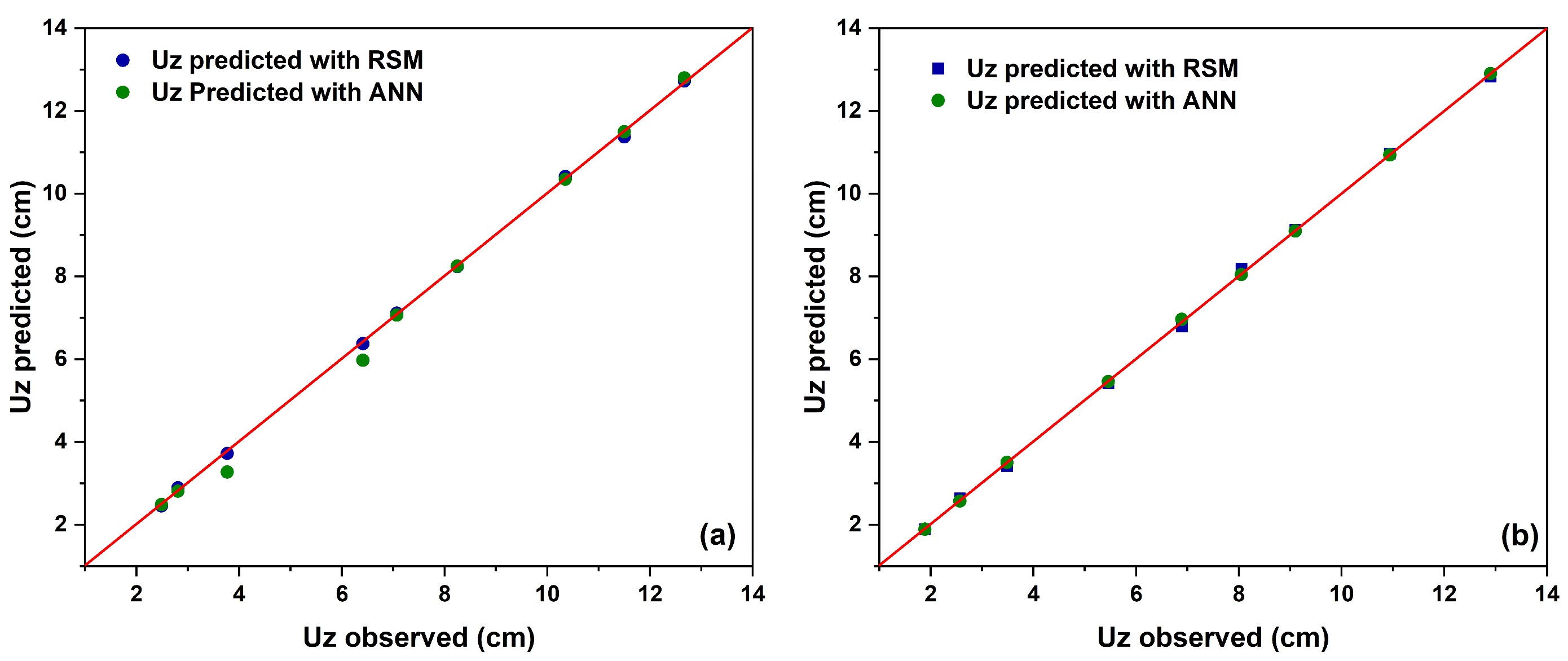

Table 6 and the corresponding observed–predicted plots (

Figure 11) provide strong evidence of the reliability of the k-fold cross-validation applied to the ANN settlement prediction models. For both rectangular and triangular DSM arrangements, the training folds produced exceptionally high coefficients of determination (R

2 > 0.999) with very low Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values. These results confirm that the ANN accurately captures the variance of settlement (Uz) during calibration.

R2 remained consistently above 0.998 during the validation phase, demonstrating the model’s strong generalization capability beyond the training data. The slight increases in RMSE and MAE between training and validation in cross-validation are expected and indicate that the model maintains high predictive accuracy without signs of overfitting. This performance confirms the robustness and reliability of the ANN framework in estimating immediate settlements for DSM-improved soft clays under complex loading conditions.

A noteworthy difference emerged between the two arrangements. While the triangular grid achieved slightly higher accuracy during training (R2 = 0.9998, RMSE = 0.041 cm), its validation errors were larger (RMSE = 0.181 cm, MAE = 0.165 cm) than those of the rectangular layout (RMSE = 0.092 cm, MAE = 0.078 cm). This indicates that, although the triangular configuration is mechanically more efficient in reducing average settlements, it is statistically more sensitive to data partitioning during cross-validation. In contrast, the rectangular arrangement shows greater stability across training and validation folds, indicating more balanced generalization performance.

The observed–predicted plots further reinforce these findings: data points for the training folds align almost perfectly along the 1:1 line for both configurations, whereas the validation points show only minor deviations—slightly more pronounced in the triangular case. These results confirm that K-fold validation provides strong evidence of model adequacy, ensuring that the predictive framework is not confined to interpolation but can reliably estimate settlement under new DSM design conditions.

In practice, while triangular arrangements may deliver superior mechanical performance, rectangular layouts offer more statistically stable predictions. This distinction highlights the importance of balancing mechanical efficiency with predictive robustness when optimizing DSM design for soft-clay ground improvement.

To predict the immediate settlement response (Uz), an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model was developed with a three-neuron-per-column arrangement. The first set of three neurons was trained on the dataset corresponding to the rectangular arrangement, while the second set was trained on the triangular arrangement. Each neuron employs a distinct transfer function and weight–bias combination, enabling the model to capture nonlinear relationships between the design parameters and settlement response. The resulting mathematical formulation can be expressed explicitly to represent the contribution of each hidden unit. Accordingly, the predictive equations for Uz are defined as follows:

Finally, the overall predictive equation for Uz is obtained as a weighted sum of the neuron outputs:

From a geotechnical perspective, the triangular DSM layout exhibits lower settlements because its geometry increases the effective column density and reduces the spacing between adjacent reinforcement points. This configuration promotes more uniform stress diffusion within the treated zone and enhances the lateral confinement acting on each column, thereby limiting bulging and improving the composite stiffness of the soil–column matrix. Furthermore, the interlocking effect between columns is more substantial in triangular arrangements, resulting in more efficient load transfer and reduced deformation compared with square grids. These mechanisms explain the superior performance of the triangular configuration observed in both numerical simulations and ANN predictions.

3.3. Validation of RSM and ANN Robustness Under Gaussian Noise Perturbation

Table 7 presents the results of the noise perturbation analysis performed for both the triangular and rectangular DSM arrangements. Gaussian noise with zero mean and a standard deviation of 5% (μ = 0, σ = 0.05) was applied to the input parameters (Sp and L) to simulate realistic uncertainties, such as measurement error, soil heterogeneity, and model discretization effects.

For each configuration, the table reports the original and perturbed predictions of settlement (Uz) obtained from the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models. The relative deviation (ΔRSM and ΔANN, expressed as a percentage) quantifies the sensitivity of each predictive framework to stochastic variations in the input space.

The “Average variation” at the bottom of each block represents the mean deviation across all cases for the given geometry. These values provide a direct indicator of model robustness: a lower mean variation implies greater numerical stability and higher resistance to noise-induced perturbations.

The data in

Table 7 reveal that both predictive models exhibit excellent numerical stability under stochastic perturbation, with average deviations well below the 5% threshold typically accepted in robust geotechnical modeling.

For the triangular arrangement, the RSM shows a mean deviation of 3.61%, while the ANN achieves 3.44%. This near-equivalence indicates that both models capture the settlement behavior consistently despite minor fluctuations in input parameters. The slight variations observed (typically between 1 and 6%) demonstrate that the RSM’s polynomial surface remains well-conditioned, and the ANN’s nonlinear mapping generalizes effectively without overfitting.

In the rectangular arrangement, the RSM deviation decreases slightly to 2.54%, confirming the model’s smooth, stable behavior in more linearly responsive systems. The ANN shows a mean variation of 3.60%, marginally higher but still within the robust range. This mild increase reflects the ANN’s heightened sensitivity to nonlinear coupling between spacing and column length, especially in configurations where interaction effects are less uniform.

From a mechanistic viewpoint, the triangular pattern inherently produces more isotropic confinement and a denser stress redistribution around the DSM columns, leading to a more nonlinear settlement response. The RSM, based on second-order polynomial approximations, tends to amplify curvature effects, slightly increasing ΔRSM. Conversely, in the rectangular grid, where deformation fields are more uniform and stress paths simpler, both RSM and ANN predictions show smoother responses and minor perturbation-induced variations.

The consistently low deviations across all cases (Δ < 4%) confirm that the models are not memorizing individual data points but are instead reproducing physically meaningful relationships encoded in the Hardening Soil Model calibration. These results validate the robustness and generalization capacity of both the RSM and ANN frameworks for DSM design optimization under uncertain conditions.

Overall, the RSM ensures interpretability and smooth numerical continuity, whereas the ANN demonstrates flexible nonlinear adaptability, capturing complex soil–structure interactions without significant sensitivity to noise. The convergence of their mean variations across both geometries indicates that the proposed hybrid approach (RSM + ANN) provides a mechanically consistent and statistically reliable predictive strategy for assessing immediate settlement in DSM-improved soft clays.

3.4. Comparison Between RSM and ANN k-Fold Predictions

The statistical performance metrics summarized in

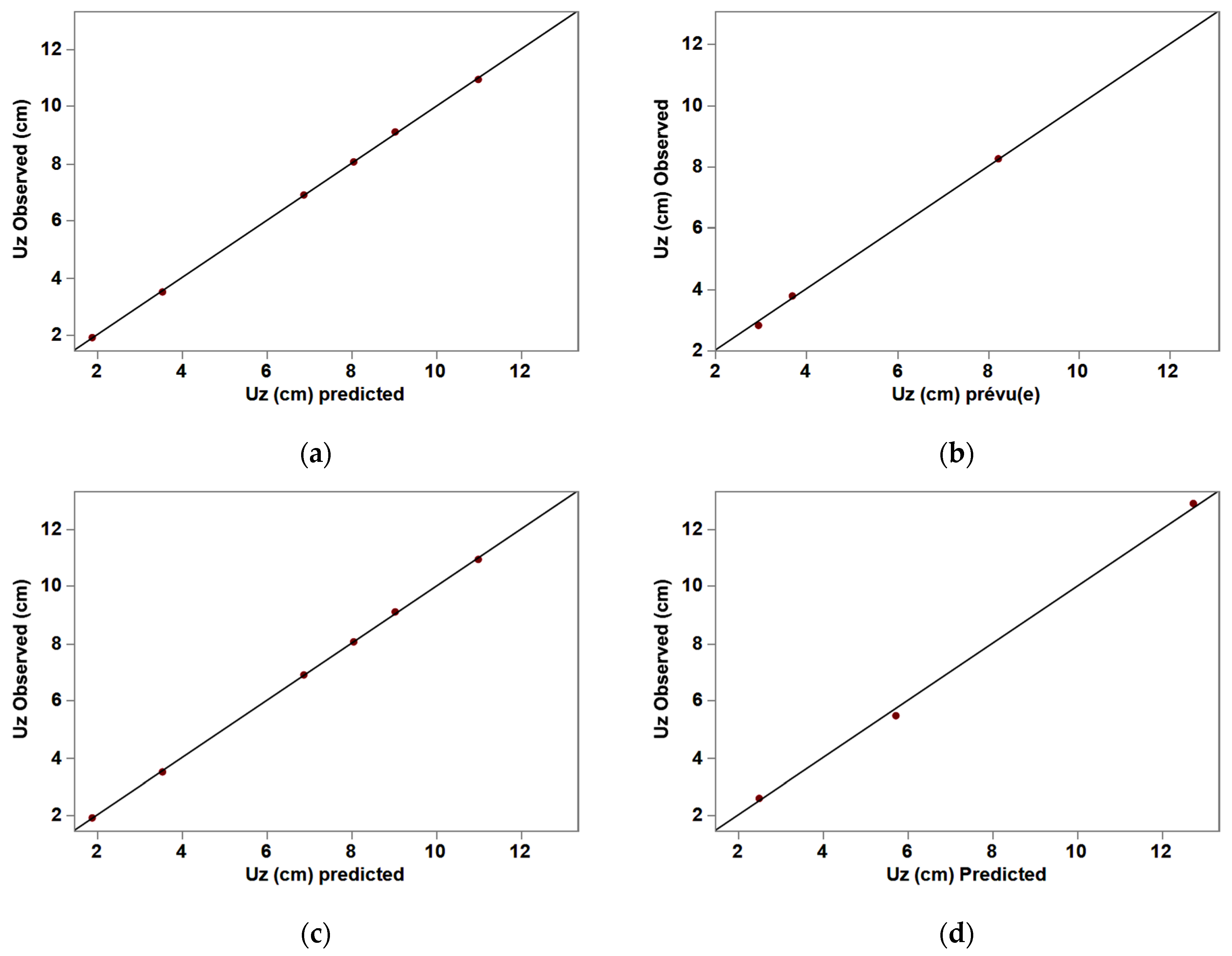

Table 8 and the observed–predicted plots shown in

Figure 12 illustrate the comparative accuracy of the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models in predicting the settlement response (Uz) of DSM-improved Tunis soft clay. For the rectangular arrangement, both models achieved nearly perfect fits, with coefficients of determination (R

2) exceeding 0.999, confirming their robustness and high predictive reliability.

Nevertheless, a closer examination of the error-based indicators reveals that the RSM model slightly outperformed the ANN. Specifically, RSM produced lower Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE = 0.0636 cm), Mean Absolute Error (MAE = 0.0553 cm), and Sum of Squared Errors (SSE = 0.0364) compared with the ANN model (RMSE = 0.0828 cm, MAE = 0.0682 cm, SSE = 0.0617). The Similarity Index (SI) also supports this conclusion, showing a tighter fit for RSM (0.0088) relative to ANN (0.0114).

Interestingly, the Relative Percent Deviation (RPD) was higher for the ANN (1.55 vs. 1.00 for RSM**), suggesting that while the neural network generalized effectively across the dataset, it exhibited slightly greater variability in prediction errors. This behavior is typical of data-driven nonlinear models that trade marginally higher dispersion for broader generalization capability. Overall, both methods demonstrated excellent predictive capacity; however, RSM showed a marginal edge in numerical stability and error consistency for the rectangular layout.

In contrast, the triangular arrangement exhibited a clear advantage for the ANN over the RSM model. Although both achieved very high coefficients of determination (R2 = 0.99995 for ANN and 0.99959 for RSM), the ANN yielded substantially lower error indices, indicating superior predictive precision. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) decreased from 0.0725 cm (RSM) to 0.0265 cm (ANN), while the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) dropped from 0.0615 cm to 0.0111 cm. Similarly, the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) was an order of magnitude lower for the ANN (0.0063 vs. 0.0473), and the Similarity Index (SI) confirmed closer agreement between observed and predicted settlements (0.0039 vs. 0.0107). These results demonstrate that the ANN model captures the nonlinear interactions governing the triangular configuration more effectively, where isotropic load transfer and denser stress redistribution produce more complex settlement behavior. Furthermore, the Relative Percent Deviation (RPD) for the ANN was notably lower (0.178), indicating a more conservative and stable error distribution than that of the RSM model.

The observed–predicted plots further corroborate these findings. In both arrangements, data points align closely with the 1:1 reference line, exhibiting negligible scatter. For the rectangular grid (

Figure 12a), the ANN predictions display slightly larger deviations at intermediate settlement values, consistent with its marginally higher RMSE and MAE. Conversely, for the triangular grid (

Figure 12b), ANN predictions nearly overlap with the observed values, reflecting its superior statistical performance and enhanced generalization of complex soil–structure interactions.

Although the ANN and RSM frameworks are data-driven, their predictive relationships remain consistent with the constitutive behavior of Tunis soft clay as represented by the Hardening Soil Model (HSM) used in the PLAXIS 3D simulations. The HSM explicitly incorporates stress-dependent stiffness moduli (E50ref, Eoed, Eur), effective cohesion (c′), and friction angle (φ′), which collectively govern the soil’s nonlinear stress–strain response. Therefore, the settlement trends learned by the ANN and RSM are not purely empirical but reflect the mechanical processes encoded in these constitutive parameters.

In this context, the DSM column length (L) controls the mobilization of deeper, stiffer sublayers, thereby influencing the equivalent secant modulus (E50ref) and the confining stress distribution. The column spacing (Sp) determines the degree of stress overlapping and confinement within untreated clay zones, affecting both volumetric and deviatoric strain components. The quadratic and interaction terms in the RSM (Sp2, L2, Sp × L) capture these nonlinear stiffness-degradation effects, analogous to the curvature of the HSM yield surface as strain increases. Similarly, the hidden neurons in the ANN implicitly represent higher-order couplings between spacing and length that arise from three-dimensional stress redistribution and shear strain localization within the composite ground.

Hence, both ANN and RSM act as computational surrogates of the HSM, translating its constitutive relationships into efficient predictive models. This mechanistic consistency ensures that the proposed data-driven approaches preserve the underlying physics of the soil–structure interaction while offering substantial computational efficiency for DSM design optimization.