Manganese-Induced Alleviation of Cadmium Stress in Rice Seedlings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials, Cultivation Conditions, and Experimental Treatments

2.2. Measurement of Growth Parameters

2.3. Determination of Chlorophyll Content and Photosynthetic Efficiency

2.4. Elemental Analysis

2.5. Chloroplast Ultrastructure Determination

2.6. Determination of ROS and Malondialdehyde Contents

2.7. Analysis of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

2.8. Determination of Expression Levels of Genes Associated with Antioxidative Enzymes and Cd/Mn Transporters

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

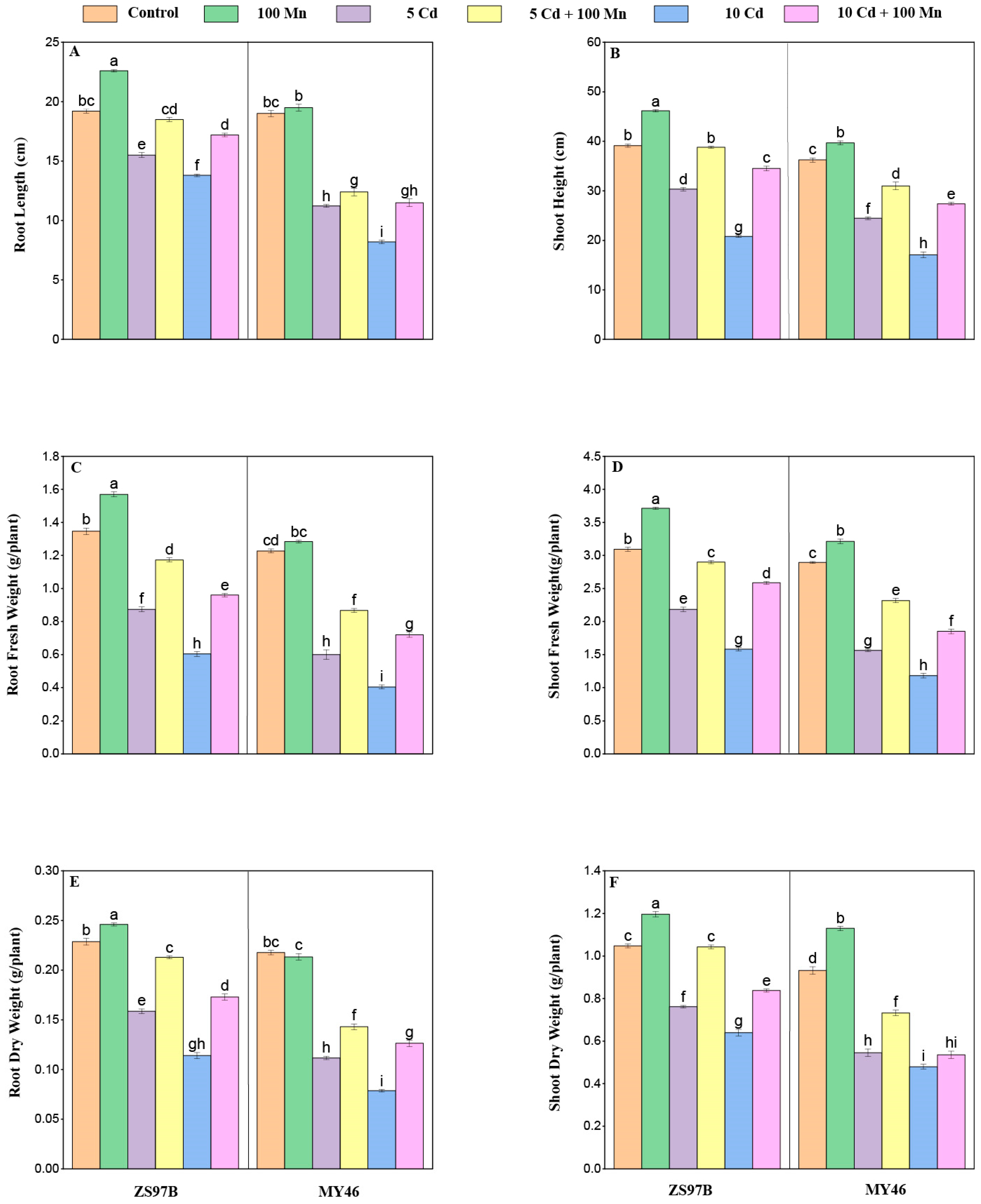

3.1. Plant Height and Dry Weight

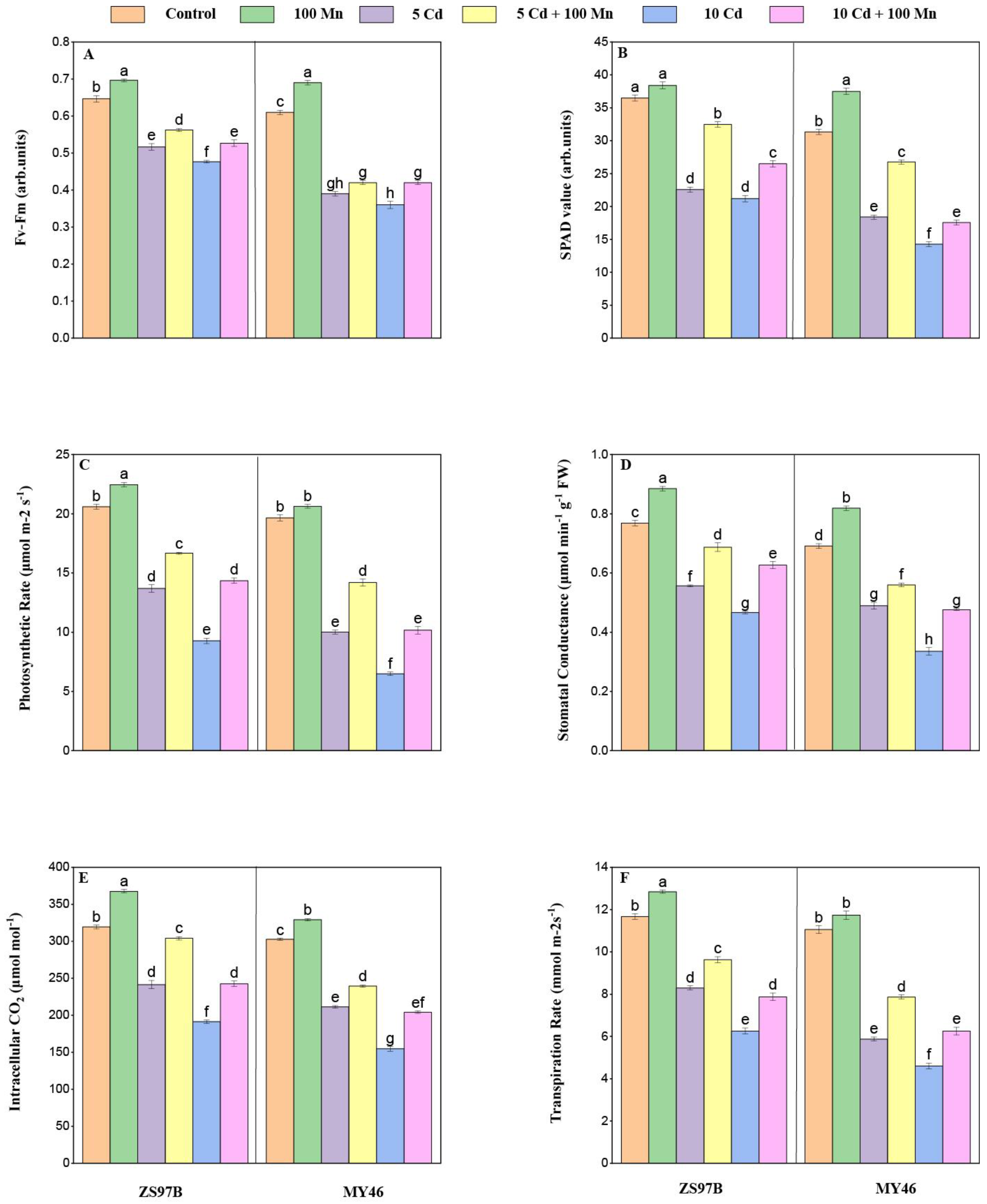

3.2. Chlorophyll Content, Fv/Fm, and Photosynthetic Parameters

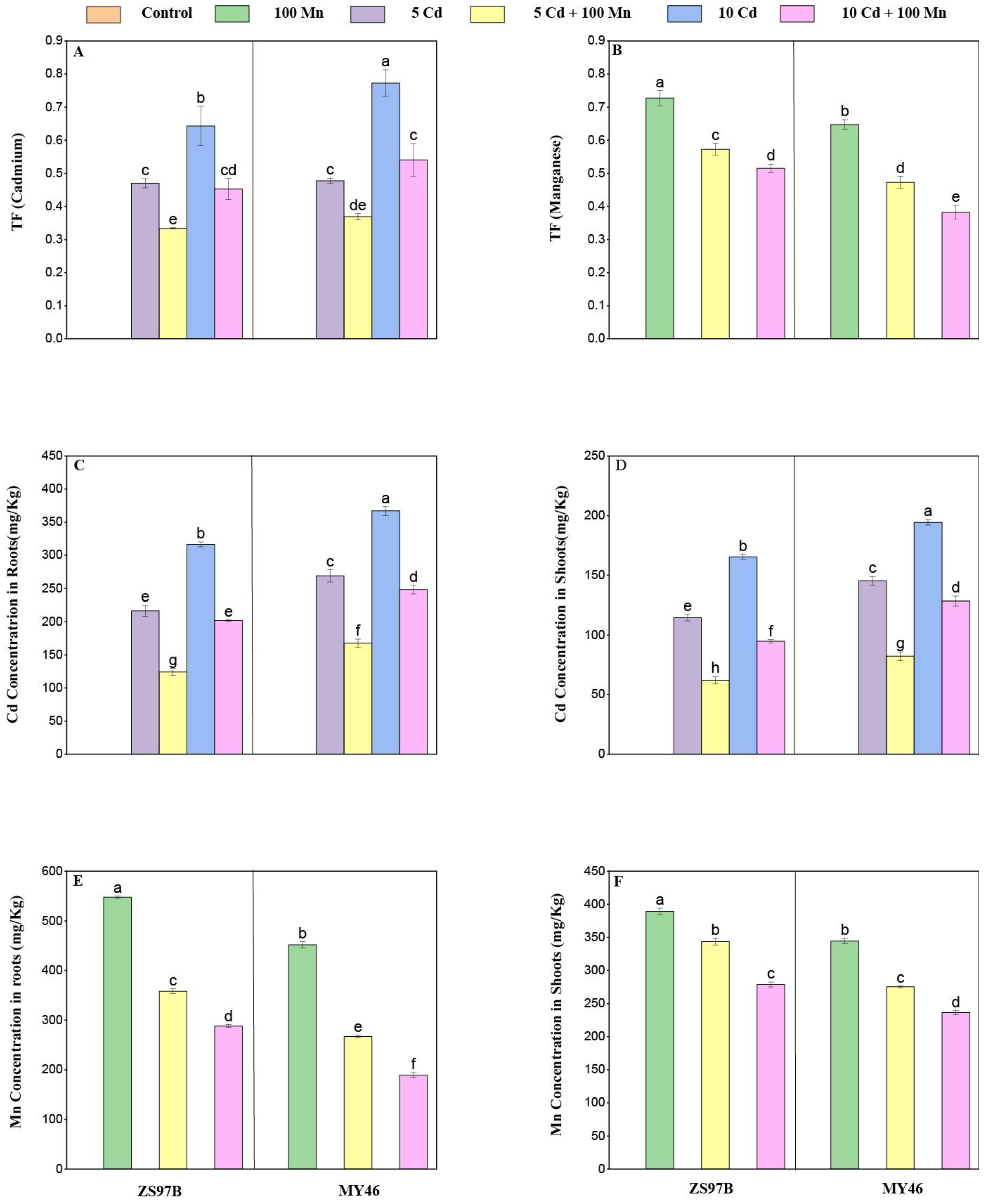

3.3. Nutrient Element Concentrations

3.4. Cd and Mn Concentrations in Roots and Shoots

3.5. Chloroplast Ultrastructure

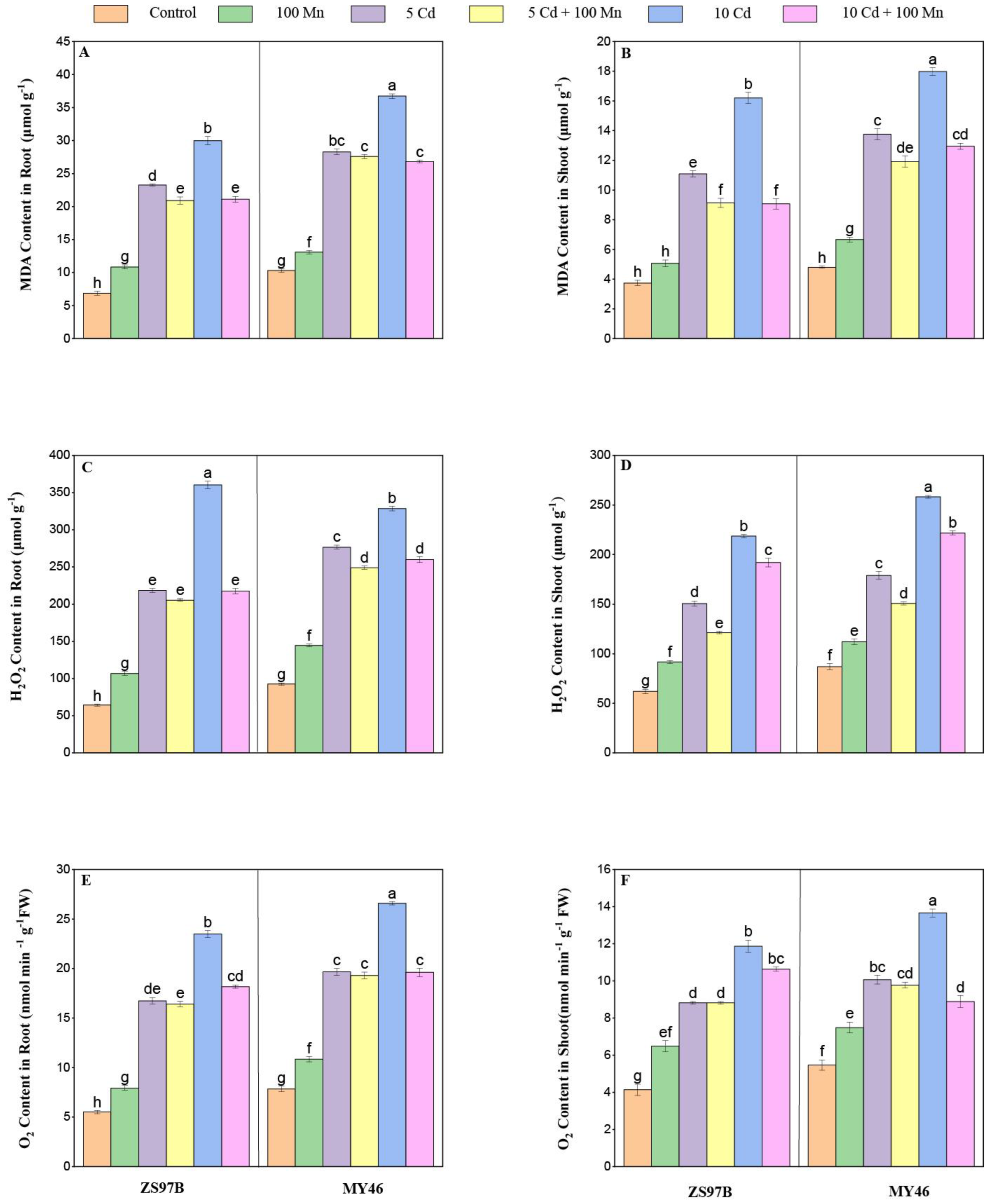

3.6. MDA and ROS Contents

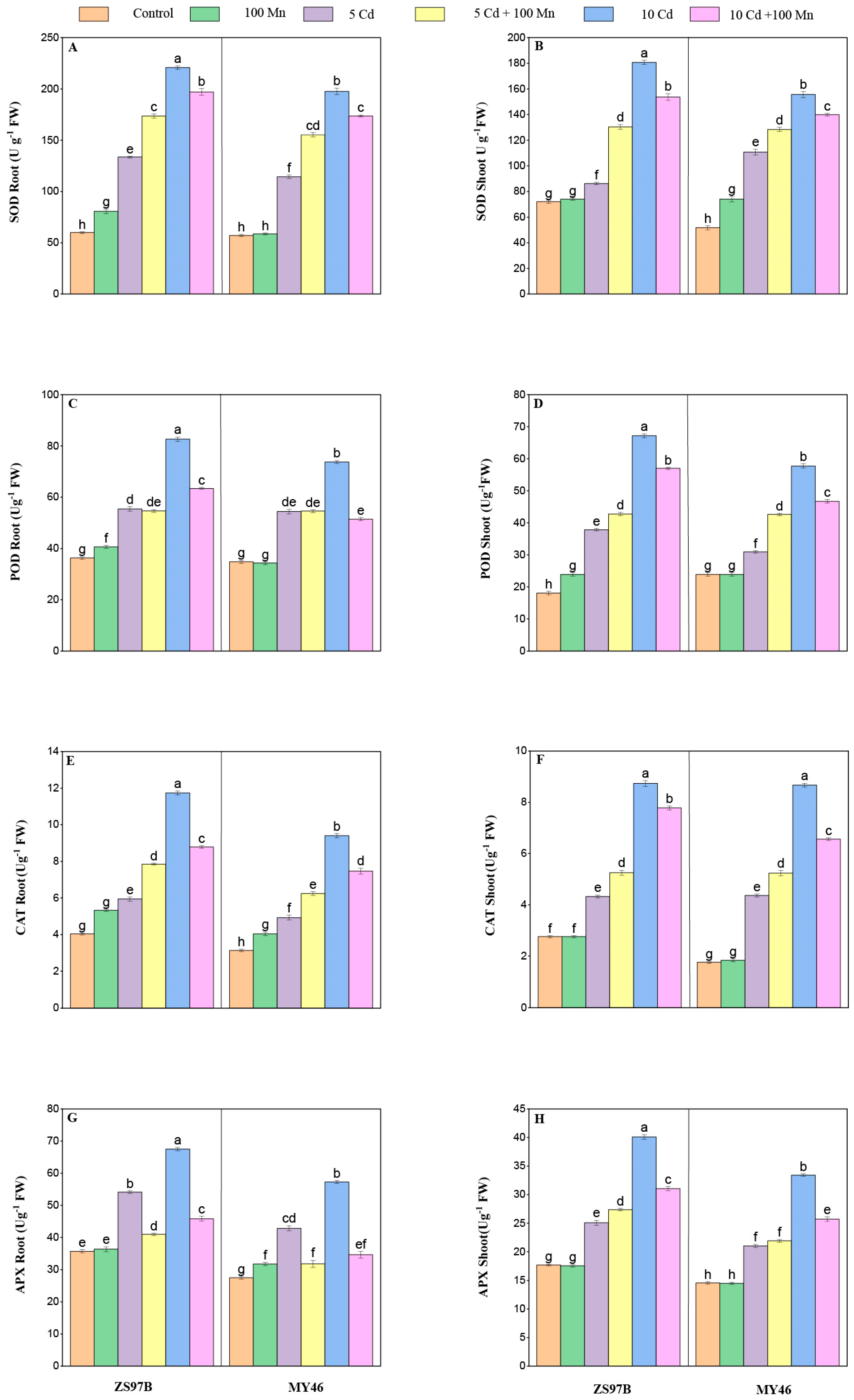

3.7. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

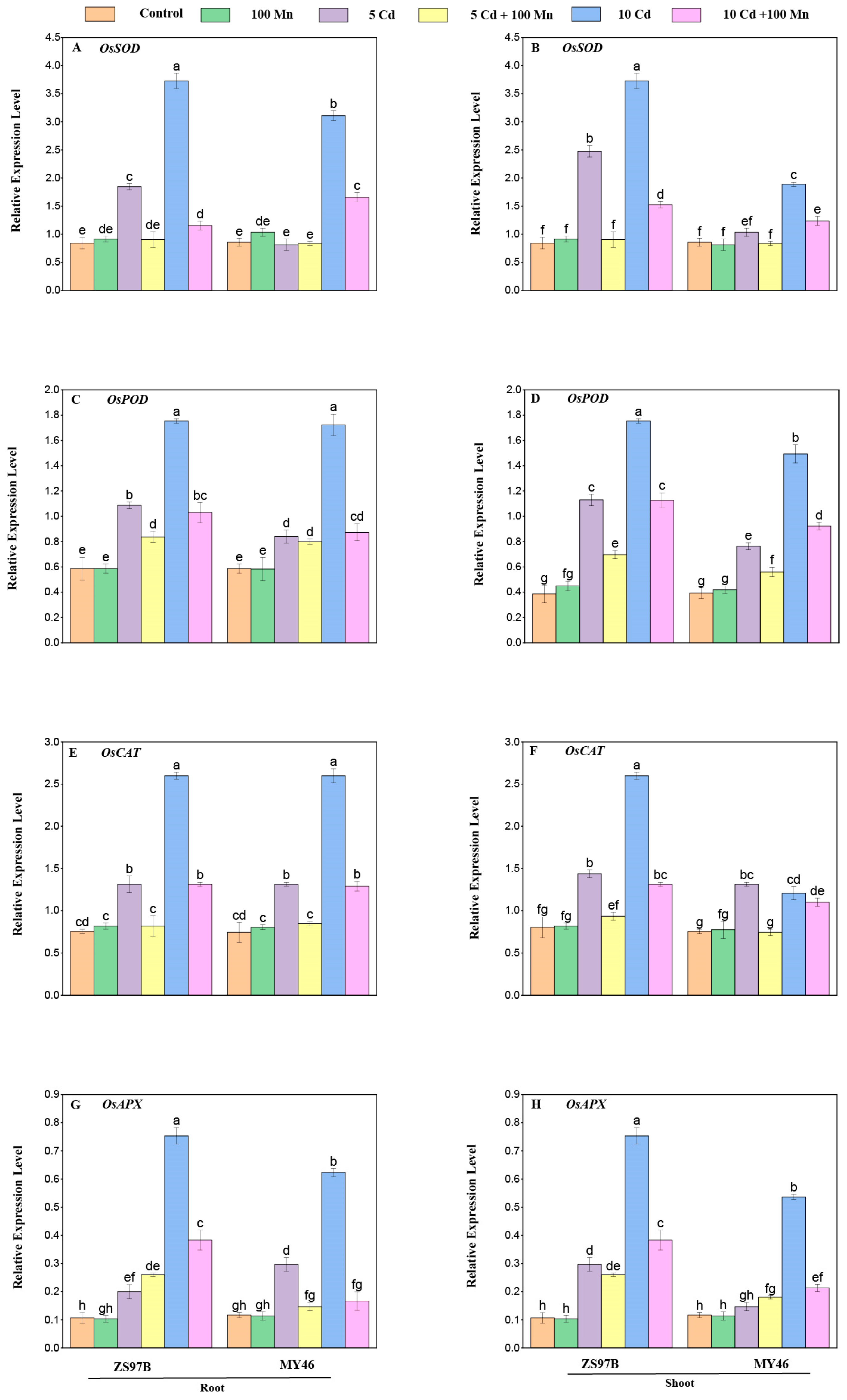

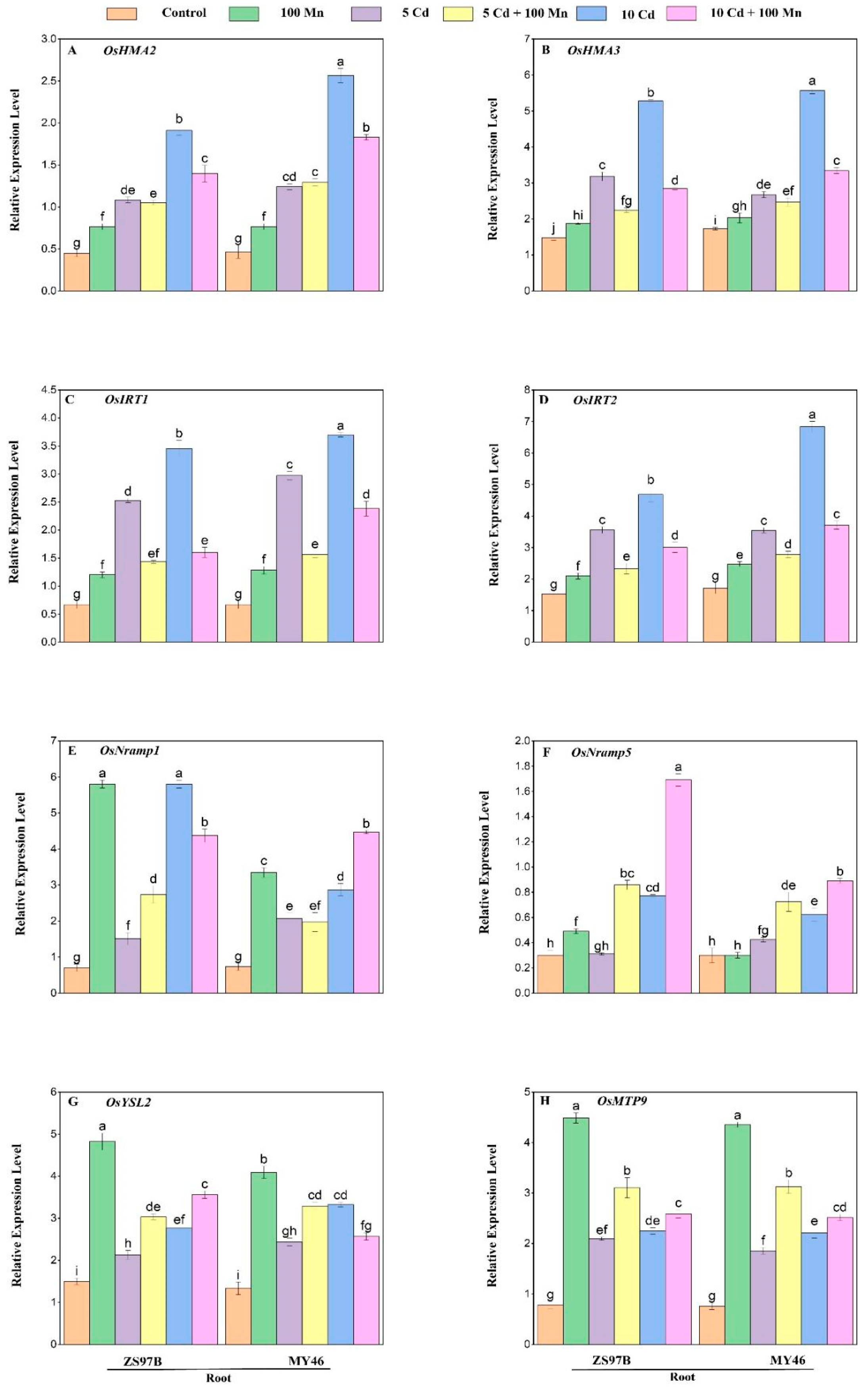

3.8. Expression Levels of Genes Related to Cd/Mn Transporters and Antioxidant Enzymes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu:, Y.; Cheng, H.; Tao, S. The Challenges and Solutions for Cadmium-Contaminated Rice in China: A Critical Review. Environ. Int. 2016, 92, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Mubeen, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Cadmium Contamination in Agricultural Soils and Crops: Theories and Methods for Minimizing Cadmium Pollution in Crops-Case Studies on Water Spinach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Rahman, S.U.; Qiu, Z.; Shahzad, S.M.; Nawaz, M.F.; Huang, J.; Naveed, S.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H. Toxic Effects of Cadmium on the Physiological and Biochemical Attributes of Plants, and Phytoremediation Strategies: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 325, 121433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Hafeez, A.; Al-Huqail, A.A.; Alsudays, I.M.; Alghanem, S.M.S.; Ashraf, M.A.; Rasheed, R.; Rizwan, M.; Abeed, A.H. Effect of Hesperidin on Growth, Photosynthesis, Antioxidant Systems and Uptake of Cadmium, Copper, Chromium and Zinc by Celosia argentea Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 207, 108433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanu, A.S.; Ashraf, U.; Bangura, A.; Yang, D.; Ngaujah, A.S.; Tang, X. Cadmium (Cd) Stress in Rice; Phyto-Availability, Toxic Effects, and Mitigation Measures a Critical Review. IOSR-JESTFT 2017, 11, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Unsal, V.; Dalkıran, T.; Çiçek, M.; Kölükçü, E. The Role of Natural Antioxidants Against Reactive Oxygen Species Produced by Cadmium Toxicity: A Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The Effects of Cadmium Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, M.; Bibi, A.; Khan, A.; Shahzad, A.; Xu, Z.; Maruza, T.M.; Zhang, G. Utilization of Antagonistic Interactions Between Micronutrients and Cadmium (Cd) to Alleviate Cd Toxicity and Accumulation in Crops. Plants 2025, 14, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Roychoudhury, A. Role of Selenium and Manganese in Mitigating Oxidative Damages. In Protective Chemical Agents in the Amelioration of Plant Abiotic Stress: Biochemical and Molecular Perspectives; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Bognor Regis, UK, 2020; pp. 597–621. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.N.; An, H.; Yang, Y.J.; Liang, Y.; Shao, G.S. Effects of Mn-Cd Antagonistic Interaction on Cd Accumulation and Major Agronomic Traits in Rice Genotypes by Different Mn Forms. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 82, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.R.M.; de Almeida, A.A.F.; Pirovani, C.P.; Barroso, J.P.; de C. Neto, C.H.; Santos, N.A.; Mangabeira, P.A.O. Mitigation of Cd Toxicity by Mn in Young Plants of Cacao, Evaluated by the Proteomic Profiles of Leaves and Roots. Ecotoxicology 2020, 29, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, M.; Peng, D.; Khan, A.; Ayyaz, A.; Askri, S.M.H.; Naz, S.; Huang, B.; Zhang, G. Sufficient Manganese Supply is Necessary for OsNramp5 Knockout Rice Plants to Ensure Normal Growth and Less Cd Uptake. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 288, 117386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, A.; Prasad, M. Iron- and Manganese-Assisted Cadmium Tolerance in Oryza sativa L.: Lowering of Rhizotoxicity Next to Functional Photosynthesis. Planta 2015, 241, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Singh, P.K.; Mankotia, S.; Swain, J.; Satbhai, S.B. Iron Homeostasis in Plants and its Crosstalk with Copper, Zinc, and Manganese. Plant Stress 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Tahir, N.; Ullah, A. Effects of Fe and Mn Cations on Cd Uptake by Rice Plant in Hydroponic Culture Experiment. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Pan, G.; Li, X.; Kuang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, W. Effects of Exogenous Manganese on its Plant Growth, Subcellular Distribution, Chemical Forms, Physiological and Biochemical Traits in Cleome viscosa L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 198, 110696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, F.; Majumdar, S.; Arzoo, S.H.; Kundu, R. Genotypic Variation Among 20 Rice Cultivars/Landraces in Response to Cadmium Stress Grown Locally in West Bengal, India. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, G. Soil Properties and Cultivars Determine Heavy Metal Accumulation in Rice Grain and Cultivars Respond Differently to Cd Stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 2019, 26, 14638–14648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ding, C.; Guo, N.; Ding, M.; Zhang, H.; Kamran, M.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Polymer-Coated Manganese Fertilizer and its Combination with Lime Reduces Cadmium Accumulation in Brown Rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.E.; Cobbett, C.S. HMA P-type ATPases are the Major Mechanism for Root-to-Shoot Cd Translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyadate, H.; Adachi, S.; Hiraizumi, A.; Tezuka, K.; Nakazawa, N.; Kawamoto, T.; Katou, K.; Kodama, I.; Sakurai, K.; Takahashi, H. OsHMA3, a P1B-type of ATPase Affects Root-to-Shoot Cadmium Translocation in Rice by Mediating Efflux into Vacuoles. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, D.; Milner, M.J.; Yamaji, N.; Yokosho, K.; Koyama, E.; Clemencia Zambrano, M.; Kaskie, M.; Ebbs, S.; Kochian, L.V.; Ma, J.F. Elevated Expression of TcHMA3 Plays a Key Role in the Extreme Cd Tolerance in a Cd-Hyperaccumulating Ecotype of Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant J. 2011, 66, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, S.; Inoue, H.; Mizuno, D.; Takahashi, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Mori, S.; Nishizawa, N.K. OsYSL2 is a Rice Metal-Nicotianamine Transporter that is Regulated by Iron and Expressed in the Phloem. Plant J. 2004, 39, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, F.; Riaz, A.; Ali, S.; Zhang, G. NRAMPs and Manganese: Magic Keys to Reduce Cadmium Toxicity and Accumulation in Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segond, D.; Dellagi, A.; Lanquar, V.; Rigault, M.; Patrit, O.; Thomine, S.; Expert, D. NRAMP Genes Function in Arabidopsis thaliana Resistance to Erwinia chrysanthemi Infection. Plant J. 2009, 58, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yamaji, N.; Yamane, M.; Kashino-Fujii, M.; Sato, K.; Feng Ma, J. The HvNramp5 Transporter Mediates Uptake of Cadmium and Manganese, but not Iron. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, F.; Wei, X.; He, J.; Sheng, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, J.; Tang, S.; Xia, S.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, P. Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci Associated with Concentrations of Five Trace Metal Elements in Rice (Oryza sativa). Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2018, 20, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Forno, D.A.; Cock, J.H. Laboratory Manual for Physiological Studies of Rice, 2nd ed.; The International Rice Research Institute: Manila, Philippines, 1972; pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lwalaba, J.L.W.; Louis, L.T.; Zvobgo, G.; Fu, L.; Mwamba, T.M.; Mundende, R.P.M.; Zhang, G. Copper Alleviates Cobalt Toxicity in Barley by Antagonistic Interaction of the Two Metals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 180–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative Stress and Some Antioxidant Systems in Acid Rain-Treated Bean Plants: Protective Role of Exogenous Polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Munné-Bosch, S. Malondialdehyde: Facts and Artifacts. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M.U.; Hannan, F.; Munir, R.; Muhammad, S.; Iqbal, M.; Yasin, I.; Khan, M.S.S.; Kanwal, F.; Chunyan, Y.; Fan, X. Interactive Mode of Biochar-Based Silicon and Iron Nanoparticles Mitigated Cd-Toxicity in Maize. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, C.; Maehly, A.C. Assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1955, 10, 764–775. [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polle, A.; Otter, T.; Seifert, F. Apoplastic peroxidases and lignification in needles of Norway spruce (Picea abies L.). Plant Physiol. 1994, 106, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, H.; Ghouri, F.; Ali, S.; Bukhari, S.A.H.; Haider, F.U.; Zhong, M.; Xia, W.; Fu, X.; Shahid, M.Q. The Protective Roles of Oryza glumaepatula and Phytohormone in Enhancing Rice Tolerance to Cadmium Stress by Regulating Gene Expression, Morphological, Physiological, and Antioxidant Defense System. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 364, 125311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Ma, T.; Adeel, M.; Shakoor, N.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, M.; Rui, Y. Effects of Two Mn-Based Nanomaterials on Soybean Antioxidant System and Mineral Element Homeostasis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 18880–18889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Najeeb, U.; Hou, Z.; Buttar, N.A.; Yang, Z.; Ali, B.; Xu, L. Soil Applied Silicon and Manganese Combined with Foliar Application of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Mediate Photosynthetic Recovery in Cd-Stressed Salvia miltiorrhiza by Regulating Cd-Transporter Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1011872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ding, X.; Liu, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Liming and Tillering Application of Manganese Alleviates Iron Manganese Plaque Reduction and Cadmium Accumulation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 427, 127897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zheng, X.; Tao, L.; Yang, Y.; Gao, L.; Xiong, J. Aeration Increases Cadmium (Cd) Retention by Enhancing Iron Plaque Formation and Regulating Pectin Synthesis in the Roots of Rice (Oryza sativa) Seedlings. Rice 2019, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharuk, E.A.; Zagoskina, N.V. Heavy Metals, Their Phytotoxicity, and the Role of Phenolic Antioxidants in Plant Stress Responses with Focus on Cadmium. Molecules 2023, 28, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakoula, A.; Therios, I.; Chatzissavvidis, C. Effect of Lead and Copper on Photosynthetic Apparatus in Citrus (Citrus aurantium L.) Plants. The Role of Antioxidants in Oxidative Damage as a Response to Heavy Metal Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, M.; Bhat, J.A.; Hessini, K.; Yu, F.; Ahmad, P. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Alleviates the Adverse Effects of Cadmium Stress on Oryza sativa via Modulation of the Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Defense System. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 220, 112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja Parmar, P.P.; Nilima Kumari, N.K.; Vinay Sharma, V.S. Structural and Functional Alterations in Photosynthetic Apparatus of Plants Under Cadmium Stress. Bot. Stud. 2013, 54, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, J.P.; de Almeida, A.-A.F.; do Nascimento, J.L.; Oliveira, B.R.M.; Dos Santos, I.C.; Mangabeira, P.A.O.; Ahnert, D.; Baligar, V.C. The Damage Caused by Cd Toxicity to Photosynthesis, Cellular Ultrastructure, Antioxidant Metabolism, and Gene Expression in Young Cacao Plants are Mitigated by High Mn Doses in Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 115646–115665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Yu, L.; Li, C.; Ding, L.; Shao, G. Interactions of Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cd in Soil–Rice Systems: Implications for Reducing Cd Accumulation in Rice. Toxics 2025, 13, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Rizvi, H.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Hannan, F.; Ok, Y.S. Cadmium Stress in Rice: Toxic Effects, Tolerance Mechanisms, and Management: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 17859–17879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Hille, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. ROS-Mediated Abiotic Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, B.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, W.; Shen, T.; Han, X.; Kontos, C.D.; Huang, S. Cadmium Induction of Reactive Oxygen Species Activates the mTOR Pathway, Leading to Neuronal Cell Death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Q.; Yun, L.; Xing, D. Production of Reactive Oxygen Species, Impairment of Photosynthetic Function and Dynamic Changes in Mitochondria are Early Events in Cadmium-Induced Cell Death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biol. Cell 2009, 101, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratovcic, A. Antioxidant Enzymes and their Role in Preventing Cell Damage. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2020, 4, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Damage, and Antioxidative Defense Mechanism in Plants Under Stressful Conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, O. Manganese Complexes Displaying Superoxide Dismutase Activity: A Balance Between Different Factors. Bioorg. Chem. 2011, 39, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J.A. The Mismetallation of Enzymes During Oxidative Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 28121–28128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Dubey, R. Manganese-Excess Induces Oxidative Stress, Lowers the Pool of Antioxidants and Elevates Activities of Key Antioxidative Enzymes in Rice Seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 64, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpoot, R.; Srivastava, R.K.; Rani, A.; Pandey, P.; Dubey, R. Manganese-Induced Oxidative Stress, Ultrastructural Changes, and Proteomics Studies in Rice Plants. Protoplasma 2021, 258, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Duan, S.; Wu, Q.; Yu, M.; Shabala, S. Reducing Cadmium Accumulation in Plants: Structure–Function Relations and Tissue-Specific Operation of Transporters in the Spotlight. Plants 2020, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.; Lei, X.; Qin, L.; Sun, X.; Chen, S. Manganese Facilitates Cadmium Stabilization Through Physicochemical Dynamics and Amino Acid Accumulation in Rice Rhizosphere Under Flood-Associated Low pe+pH. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, C.; Guo, H.; Hu, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, D. Overexpression of a Miscanthus sacchariflorus Yellow Stripe-Like Transporter MsYSL1 Enhances Resistance of Arabidopsis to Cadmium by Mediating Metal Ion Reallocation. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 85, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, B. Role of Transporters of Copper, Manganese, Zinc, and Nickel in Plants Exposed to Heavy Metal Stress. In Metal and Nutrient Transporters in Abiotic Stress; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Ma, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Long, D.; Xiao, X. Manganese and Copper Additions Differently Reduced Cadmium Uptake and Accumulation in Dwarf Polish Wheat (Triticum polonicum L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Limmer, M.A.; Seyfferth, A.L. How Manganese Affects Rice Cadmium Uptake and Translocation in Vegetative and Mature Plants. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.D.; Huang, S.; Konishi, N.; Wang, P.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhao, F.J. Overexpression of the Manganese/Cadmium Transporter OsNRAMP5 Reduces Cadmium Accumulation in Rice Grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5705–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Guan, Q.; Niu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Cheng, H. Progress in Elucidating the Mechanism of Selenium in Mitigating Heavy Metal Stress in Crop Plants. Agriculture 2025, 15, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Z.; Ahmad, I.; Zia, S.; Gan, Y. Recent Developments in Rice Molecular Breeding for Tolerance to Heavy Metal Toxicity. Agriculture 2023, 13, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Pal, S.; Paul, S. Silicon as a Powerful Element for Mitigation of Cadmium Stress in Rice: A Review for Global Food Safety. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Cai, S.; Yan, C.; Rao, S.; Cheng, S.; Xu, F.; Liu, X. Research Progress on the Physiological Mechanism by which Selenium Alleviates Heavy Metal Stress in Plants: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, M.A.; James, B.; Chen, Y.H.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Li, H.H.; Jayasuriya, P.; Guo, W. Uptake, translocation, and accumulation of Cd and its interaction with mineral nutrients (Fe, Zn, Ni, Ca, Mg) in upland rice. Chemosphere 2019, 215, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, X.H.; Du, S.T. Interactions Between Cadmium and Nutrients and Their Implications for Safe Crop Production in Cd-Contaminated Soils. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 2071–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Nahar, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Manganese-Induced Cadmium Stress Tolerance in Rice Seedlings: Coordinated Action of Antioxidant Defense, Glyoxalase System and Nutrient Homeostasis. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2016, 339, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.; Yamaji, N.; Mao, C.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.F. Lateral Roots but not Root Hairs Contribute to High Uptake of Manganese and Cadmium in Rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 7219–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhao, L.; Liang, X.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y. Soil Application of Manganese Sulfate Effectively Reduces Cd Bioavailability in Cd-Contaminated Soil and Cd Translocation and Accumulation in Wheat. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, S.; Höller, S.; Meier, B.; Peiter, E. Manganese in Plants: From Acquisition to Subcellular Allocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; An, H.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Shao, G. Phosphorus Application Interferes Expression of Fe Uptake-Associated Genes to Feedback Regulate Cd Accumulation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) and Relieves Cd Toxicity via Antioxidant Defense. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 102, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Mg (mg/kg) | P (mg/kg) | Na (mg/kg) | K (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | Fe (mg/kg) | Cu (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZS97B Root | |||||||

| Control | 287.00 b | 748.47 b | 342.90 b | 836.18 b | 15.08 b | 257.56 b | 16.45 b |

| 100 µM Mn | 332.88 a | 859.34 a | 386.96 a | 976.66 a | 16.84 a | 279.89 a | 19.20 a |

| 5 µM Cd | 194.73 f | 549.12 d | 219.71 f | 624.43 e | 10.38 e | 171.33 e | 10.18 e |

| 5µMCd + 100 µM Mn | 260.00 c | 661.45 c | 294.57 c | 809.56 b | 12.14 d | 192.08 d | 14.29 c |

| 10 µM Cd | 145.23 h | 424.97 f | 158.16 g | 482.94 f | 7.14 g | 113.18 g | 6.31 g |

| 10 µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 235.35 d | 576.12 d | 264.82 d | 645.05 de | 10.11 e | 171.66 e | 12.68 d |

| ZS97B shoot | |||||||

| Control | 619.74 b | 455.14 b | 83.08 b | 1269.75 b | 9.58 b | 119.46 b | 3.26 b |

| 100 µM Mn | 723.21 a | 552.68 a | 90.09 a | 1483.82 a | 10.91 a | 138.10 a | 3.89 a |

| 5 µM Cd | 385.65 f | 349.12 d | 45.50 h | 937.79 e | 5.71 e | 84.68 d | 2.47 e |

| 5µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 505.41 d | 461.45 b | 65.32 e | 1113.75 c | 8.02 c | 102.39 c | 2.85 c |

| 10 µM Cd | 346.58 g | 248.31 e | 36.66 i | 730.10 f | 3.95 g | 64.10 f | 1.90 h |

| 10 µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 440.79 e | 376.12 c | 48.08 g | 1017.57 d | 6.75 d | 89.56 d | 2.62 d |

| MY46 Root | |||||||

| Control | 261.14 c | 677.91 c | 300.14 c | 722.25 c | 13.16 c | 226.03 c | 14.78 c |

| 100 µM Mn | 290.37 b | 747.65 b | 332.23 b | 850.24 b | 14.87 b | 247.65 b | 16.52 b |

| 5 µM Cd | 154.11 h | 418.29 f | 154.90 g | 479.56 f | 8.51 f | 128.38 f | 7.82 f |

| 5µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 216.27 e | 564.97 d | 237.80 e | 672.77 d | 10.43 e | 165.83 e | 12.19 d |

| 10 µM Cd | 90.72 i | 322.54 g | 104.73 h | 363.82 g | 5.55 h | 83.04 h | 4.60 h |

| 10 µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 180.58 g | 463.58 e | 223.67 f | 513.33 f | 7.99 f | 138.30 f | 9.83 e |

| MY46 Shoot | |||||||

| Control | 537.55 c | 376.58 c | 73.98 d | 1098.32 c | 8.20 c | 106.12 c | 2.79 c |

| 100 µM Mn | 603.62 b | 464.32 b | 78.97 c | 1260.60 b | 9.64 b | 122.97 b | 3.25 b |

| 5 µM Cd | 313.38 h | 248.29 e | 36.57 i | 750.99 f | 4.68 f | 64.76 f | 1.90 h |

| 5µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 444.64 e | 371.64 cd | 54.81 f | 958.51 de | 6.01 e | 86.84 d | 2.32 f |

| 10 µM Cd | 265.17 i | 165.87 f | 27.02 j | 558.49 g | 2.62 h | 50.07 g | 1.45 i |

| 10 µM Cd + 100 µM Mn | 362.66 g | 268.58 e | 38.44 i | 775.72 f | 4.76 f | 71.65 e | 2.11 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shahzad, M.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, Z.; Khan, A.; Wang, Z.; Bibi, A.; Maruza, T.M.; Ayyaz, A.; Zhang, G. Manganese-Induced Alleviation of Cadmium Stress in Rice Seedlings. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312704

Shahzad M, Zheng Y, Cai Z, Khan A, Wang Z, Bibi A, Maruza TM, Ayyaz A, Zhang G. Manganese-Induced Alleviation of Cadmium Stress in Rice Seedlings. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312704

Chicago/Turabian StyleShahzad, Muhammad, Yuling Zheng, Zhenyu Cai, Ameer Khan, Zheng Wang, Ayesha Bibi, Tagarika Munyaradzi Maruza, Ahsan Ayyaz, and Guoping Zhang. 2025. "Manganese-Induced Alleviation of Cadmium Stress in Rice Seedlings" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312704

APA StyleShahzad, M., Zheng, Y., Cai, Z., Khan, A., Wang, Z., Bibi, A., Maruza, T. M., Ayyaz, A., & Zhang, G. (2025). Manganese-Induced Alleviation of Cadmium Stress in Rice Seedlings. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12704. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312704