Abstract

Federated learning (FL) is emerging as a pivotal paradigm for environmental monitoring, enabling decentralized model training across edge devices without exposing raw data. This review provides the first structured synthesis of 361 peer-reviewed studies, offering a comprehensive overview of how FL has been implemented across environmental domains such as air and water quality, climate modeling, smart agriculture, and biodiversity assessment. We further provide comparative insights into model architectures, energy-aware strategies, and edge-device trade-offs, elucidating how system design choices influence model stability, scalability, and sustainability. The analysis traces the technological evolution of FL from communication-efficient prototypes to robust, context-aware deployments that integrate domain knowledge, physical modeling, and ethical considerations. Persistent challenges remain, including data heterogeneity, limited benchmarking, and inequitable access to computational infrastructure. Addressing these requires advances in hybrid physics–AI frameworks, privacy-preserving sensing, and participatory governance. Overall, this review positions FL not merely as a technical mechanism but as a socio-technical shift—one that aligns distributed intelligence with the complexity, uncertainty, and urgency of contemporary environmental science.

Keywords:

federated learning; environmental monitoring; edge AI; air and water quality; smart agriculture; biodiversity sensing; privacy-preserving machine learning; distributed intelligence; edge computing; climate data modeling; sustainability; non-IID data; sensor networks; explainable AI; energy-aware learning 1. Introduction

The exponential rise in sensor-equipped devices and the expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT) have revolutionized data acquisition across numerous domains, particularly in environmental monitoring. From remote hydrological stations and urban air quality sensors to mobile agricultural drones, the influx of decentralized data has outpaced traditional approaches to model training and inference. The conventional cloud-centric paradigm—where raw data is transmitted to a central server for learning—poses critical challenges, including latency, bandwidth limitations, data ownership concerns, and above all, privacy violations. As environmental data often contain sensitive information tied to geography, land use, or infrastructure, the need for privacy-preserving yet collaborative learning frameworks is more pressing than ever [,].

Federated learning (FL) has emerged as a promising solution to these challenges. Rather than aggregating data in a central repository, FL allows local devices to collaboratively train a shared model while keeping data on-premise. Only model updates are exchanged, significantly reducing the risk of data leakage while enabling distributed intelligence. In essence, FL bridges the gap between the growing demand for data-driven insights and the societal, legal, and technical barriers to centralized data collection [,].

The strength of FL lies not only in its privacy-preserving nature but also in its architectural adaptability. Ref. [] demonstrated that edge-based FL architectures in IoT wireless sensor networks can simultaneously uphold energy efficiency and privacy in resource-constrained environments. This is of particular importance for environmental deployments where energy harvesting, intermittent connectivity, and computational constraints are the norm. Similarly, Ref. [] introduced a mobility-aware FL scheduling framework for vehicular edge networks—a concept highly transferable to mobile sensing platforms used in environmental monitoring, such as drones or autonomous boats. Their results confirm that even under dynamic network topologies, FL can maintain low latency and high task completion rates [,].

At the intersection of privacy and reliability, Ref. [] proposed a novel FL framework for real-time anomaly detection in edge devices. Although targeted at cybersecurity, their work offers valuable methodological foundations for environmental anomaly detection tasks—such as identifying chemical spills, illegal deforestation, or sudden climatic deviations—where rare events are critical yet difficult to model centrally [,].

Despite its potential, the deployment of FL in environmental contexts remains fragmented. Most current research has concentrated on smart cities, healthcare, and industry, with environmental science lagging behind in implementation. This discrepancy underscores the need to systematically review the models, devices, and integration strategies that enable effective FL in nature-facing applications. Doing so requires not only an evaluation of algorithms but also a reflection on the sensor ecosystems, data heterogeneity, communication protocols, and interpretability demands unique to environmental science [,].

In this article, we examine the current landscape of federated learning applied to environmental monitoring. We identify domain-specific challenges and innovations, drawing from recent advances in energy-aware edge computing, mobility-aware aggregation, multimodal sensing, and secure distributed inference. Our review builds on curated literature to map out how FL is reshaping environmental data analysis—not merely as a computational improvement, but as a structural rethinking of how we sense, model, and act upon our changing planet [,].

2. Methodology

In reviewing the landscape of federated learning (FL) applications in environmental monitoring, we adopted a rigorous, transparent, and reproducible methodology based on the PRISMA 2020 framework.

The goal was not only to chart the growth of FL across environmental domains but also to critically evaluate how these technologies interact with real-world constraints, heterogeneous data streams, and energy-limited sensing infrastructures [,].

The approach combined quantitative mapping with qualitative synthesis, allowing us to examine both the scale and structure of current research trends.

We began by querying the Scopus database, chosen for its interdisciplinary coverage and consistent indexing of peer-reviewed articles in computer science, engineering, and environmental sciences.

Scopus was selected over Web of Science and IEEE Xplore because of its broader inclusion of applied and cross-domain works—essential for a topic bridging artificial intelligence and environmental monitoring.

The search covered the years 2018–2025, spanning both the conceptual emergence of federated learning and its recent applications in environmental and sustainability-oriented contexts.

To minimize retrieval bias, we combined indexed keywords with author-defined terms, capturing papers even where “federated learning” was not explicitly listed in titles or abstracts [,].

The search included combinations of terms such as “federated learning”, “environmental monitoring”, “IoT”, “distributed learning”, “edge device”, “sensor network”, “water quality”, and “air pollution”, alongside domain-specific expressions like “precision agriculture”, “smart farming”, and “biodiversity tracking”.

Our inclusion criteria were deliberately broad in domain yet narrow in intent.

We included only original, peer-reviewed research articles that directly applied federated learning or its derivatives (e.g., hierarchical or hybrid FL) to environmental, ecological, or sustainability-related data.

Framework-only studies, theoretical expositions, or security-focused FL papers were excluded unless they explicitly demonstrated applicability in an environmental context. Conference abstracts, editorials, and non-peer-reviewed materials were also excluded to maintain methodological consistency [].

A specific methodological consideration was the decision to include only open-access or institutionally retrievable publications.

This criterion was applied not as a convenience but as a principled stance toward scientific transparency, equity, and reproducibility.

Environmental data science is deeply connected to the public good and policy-making; restricting a systematic review to open literature ensures that all underlying evidence remains verifiable, shareable, and auditable by researchers and institutions regardless of financial barriers.

In addition, reproducibility is a key expectation in the current open science paradigm, including the UNESCO Open Science Recommendations (2021) and the European Open Data Directive, both of which emphasize equitable access to scientific outputs as part of sustainable research infrastructure.

We recognize that this choice may introduce an accessibility bias, as some closed-access papers—often from industry-funded or commercial research—were excluded.

However, this trade-off was considered acceptable, as open-access filtering enhances the transparency and ethical accountability of the dataset, ensuring that future researchers can replicate, verify, and extend the findings without restriction [,,].

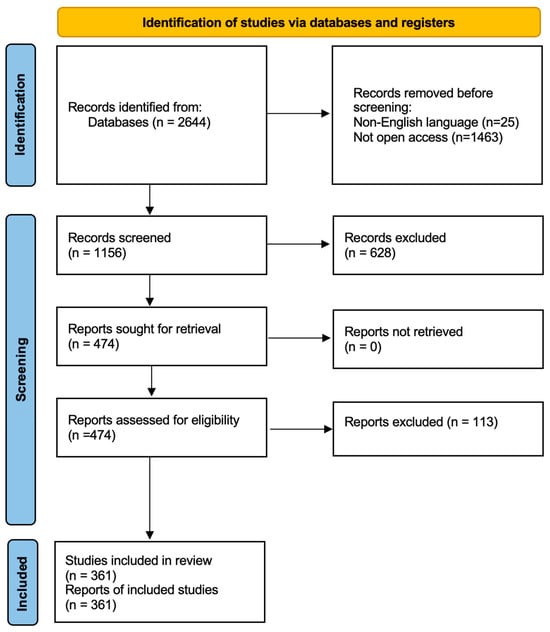

The search process identified a total of 2644 records. After the removal of duplicates and exclusions of non-English (n = 25) and non-open-access papers (n = 1463), 1156 records remained for screening. During the title and abstract review, 628 papers were excluded due to insufficient methodological detail, lack of environmental linkage, or absence of federated architecture. A total of 474 records were sought for full-text retrieval, of which all were successfully obtained. At the eligibility stage, 113 papers were excluded due to insufficient methodological detail, lack of environmental linkage, or overlap between multiple domain categories. Following eligibility assessment, 361 studies met all inclusion criteria and were retained for qualitative synthesis.

The entire selection process, including all filtering stages, is visualized in Figure 1 (PRISMA 2020 flow diagram), which has been updated for numerical consistency and transparency.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Each included study was systematically analyzed along multiple analytical dimensions:

- Application domain (e.g., air and water quality, climate modeling, smart agriculture, biodiversity, energy systems);

- Model type (e.g., CNN, RNN, LSTM, hybrid architectures, ensemble FL, physics-informed models);

- Hardware integration (e.g., edge devices, IoT nodes, fog computing units, energy-harvesting systems);

- Algorithmic characteristics, such as aggregation strategies (FedAvg, FedProx, FedDrop), interpretability mechanisms, and privacy-preserving methods (secure aggregation, differential privacy).

A secondary coding layer captured hybridization and context-awareness, identifying papers that combined FL with complementary techniques such as blockchain, reinforcement learning, differential privacy, or swarm optimization. This two-tiered coding enabled both quantitative aggregation (publication frequency by domain and year) and qualitative synthesis (architectural patterns, performance trade-offs, and interpretability).

For deep analysis, we curated a “core set” of highly representative studies distinguished by methodological novelty, reproducibility, and ecological relevance. This subset provided the foundation for comparative discussion in later sections (Section 4, Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7), including model design, energy efficiency, and governance challenges.

We also examined the geographical and institutional distribution of environmental FL studies, observing concentration in China, the United States, and Europe, with emerging contributions from India and Southeast Asia—reflecting the global diffusion of federated environmental intelligence [,].

Although our procedure adheres to PRISMA 2020 standards, it was not purely mechanical. Given the dynamic and cross-disciplinary nature of environmental FL, interpretive judgment was applied to ensure that relevance and quality outweighed strict keyword matching. In this sense, the review extends beyond cataloguing publications—it aims to contextualize federated learning within the evolving epistemology of environmental data science, where openness, sustainability, and algorithmic equity converge [].

The literature search was conducted in Scopus, using a structured query designed to capture works at the intersection of federated learning, environmental applications, and sensing technologies. The exact query string was as follows:

- (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“federated learning”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(environment* OR “environmental monitoring” OR ecosystem* OR pollution OR “air quality” OR “water quality” OR biodiversity OR “precision agriculture” OR “smart farming” OR “wildlife monitoring” OR “forest monitoring”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(sensor* OR “edge device” OR “IoT” OR “Internet of Things” OR “embedded system*” OR microcontroller OR microcomputer OR “Raspberry Pi” OR Arduino OR wearable OR “remote sensing” OR drone OR “unmanned vehicle”))

- AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”))

- AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”))

- AND (LIMIT-TO (OA, “all”))

The search was finalized on 22 July 2025, yielding 361 documents after filtering.

The Scopus query can be accessed directly via the following persistent link: https://www.scopus.com/results/results.uri?s=%28TITLE-ABS-KEY%28%22federated+learning%22%29+AND+TITLE-ABS-KEY%28environment*+OR+%22environmental+monitoring%22+OR+ecosystem*+OR+pollution+OR+%22air+quality%22+OR+%22water+quality%22+OR+biodiversity+OR+%22precision+agriculture%22+OR+%22smart+farming%22+OR+%22wildlife+monitoring%22+OR+%22forest+monitoring%22%29+AND+TITLE-ABS-KEY%28sensor*+OR+%22edge+device%22+OR+%22IoT%22+OR+%22Internet+of+Things%22+OR+%22embedded+system*%22+OR+microcontroller+OR+microcomputer+OR+%22Raspberry+Pi%22+OR+Arduino+OR+wearable+OR+%22remote+sensing%22+OR+drone+OR+%22unmanned+vehicle%22%29%29+&cluster=freetoread%2C%22all%22%2Ct%2Bsubtype%2C%22ar%22%2Ct%2Blang%2C%22English%22%2Ct&limit=10&origin=searchhistory&sort=plf-f&src=s&sot=a&sdt=cl&sessionSearchId=7d8a3f64fa053f709f30ba93f63d9120 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

3. Background and Conceptual Foundations

Federated learning emerged from the need to train machine learning models collaboratively without requiring centralized access to data. Originally formalized by [], FL introduces a learning protocol in which each participating device—often called a client—trains a local model on its private data and transmits only the model updates to a coordinating server. These updates are then aggregated (typically via algorithms like Federated Averaging) to refine a global model. The process is repeated iteratively, enabling model convergence across decentralized data sources [].

What makes FL particularly suitable for environmental applications is the structural alignment between its decentralized philosophy and the fragmented, often inaccessible nature of environmental data collection. Monitoring systems in agriculture, hydrology, atmospheric science, and urban ecosystems are typically composed of spatially distributed sensors—many operating under strict energy constraints, limited bandwidth, or intermittent connectivity. These constraints make traditional cloud-based machine learning not only inefficient but frequently impractical. Sending raw environmental data to the cloud introduces latency, privacy concerns (especially in relation to geolocation or land ownership), and a dependence on stable network infrastructure that is rarely guaranteed in remote or resource-limited areas [].

By contrast, FL enables models to be trained directly at the data source. This is especially valuable when dealing with privacy-sensitive ecological parameters, proprietary farming data, or high-frequency sensor streams where real-time decisions are needed. Moreover, FL architectures can be combined with edge computing frameworks, enabling models to be trained and deployed locally—reducing latency and dependence on centralized servers. This synergy has led to a proliferation of hybrid designs: FL combined with fog computing, blockchain for auditability, reinforcement learning for adaptive sensing, or even TinyML for low-power inference [].

The environmental domain also introduces unique complexities for FL. Unlike standardized corporate datasets (e.g., in finance or healthcare), environmental data tend to be non-IID (independent and identically distributed) due to variation in geography, weather, soil type, or sensor calibration. This non-IID nature poses a serious challenge to model convergence and generalizability. Aggregation techniques must account for heterogeneity not just in data quantity, but in its underlying distribution. Furthermore, environmental monitoring often prioritizes interpretability—not only to satisfy scientific standards, but also to support public communication and regulatory transparency. Therefore, FL models in this space must often trade raw performance for explainability and robustness [].

Another important aspect is sensor modality. Environmental systems rarely rely on a single data stream; instead, they integrate temperature, humidity, pH, salinity, spectral imagery, and more. This calls for multimodal architectures—federated systems capable of fusing data from diverse sensors, often with inconsistent sampling rates and data quality. Some recent studies have begun exploring hierarchical federated architectures, where edge nodes conduct modality-specific training before sharing compressed representations with a regional coordinator—a setup especially relevant in large-scale environmental observatories or smart agriculture grids [].

Ultimately, federated learning is more than a technical innovation. In the environmental context, it represents a shift in how we think about learning itself: not as a centralized act of abstraction, but as a distributed, negotiated process that respects the situatedness of data. It embodies a computational ethics that mirrors ecological ethics—favoring locality, diversity, and collaboration over uniformity and extraction. This alignment is not incidental. It is precisely what makes FL a promising frontier in sustainable, context-aware environmental intelligence [].

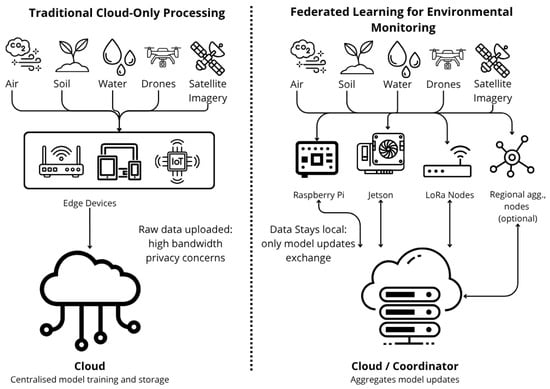

To illustrate the differences between traditional centralized processing and the federated paradigm, we provide a schematic comparison. Figure 2 presents the conceptual architecture for environmental monitoring, contrasting cloud-only pipelines (left) with federated learning (right). In the traditional model, sensors such as air, soil, water, drone, and satellite systems send raw data through thin edge node to a central cloud for storage and analysis, raising concerns about bandwidth and privacy. In contrast, federated learning enables local training directly on edge devices, with optional fog-level aggregation, while the central coordinator aggregates only model updates. This design preserves data locality and enhances scalability without exposing raw sensor data.

Figure 2.

Conceptual architecture for environmental monitoring: comparison of traditional cloud-only pipelines (left) and federated learning (right). Sensors (air, soil, water, drones, satellite imagery) feed edge devices; in FL, local training occurs on-device, optional regional/fog aggregation supports hierarchical FL, and the coordinator aggregates model updates (no raw data sharing).

4. Technological Landscape: Models, Devices, and Architectures in Environmental FL Applications

The adoption of federated learning (FL) in environmental systems has expanded rapidly in recent years, propelled by improvements in edge computing, low-power hardware, and lightweight neural architectures. Yet, the technological ecosystem remains fragmented, shaped by application complexity, uneven data availability, and the operational constraints of decentralized sensing networks [,,,,,]. This section analyses the evolving interplay between model architectures, device configurations, and communication topologies that define the current landscape of environmental FL.

4.1. Model Architectures and Learning Algorithms

Deep learning models form the computational core of most environmental FL frameworks.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are the most common choice for vision-based applications—such as vegetation mapping, pest detection, or satellite classification—where spatial continuity and texture are key predictive features.

Edge-optimized variants (e.g., MobileNet, EfficientNet-Lite) achieve acceptable accuracy while maintaining a small memory footprint.

By contrast, recurrent architectures (RNN, LSTM, GRU) dominate time-dependent tasks, such as hydrological forecasting, soil moisture estimation, or air pollution modeling. Their ability to model temporal autocorrelation makes them particularly well suited for sensor networks that sample sequentially.

Recently, graph neural networks (GNNs) have gained traction for spatially interconnected systems—for example, modeling river networks or pollutant transport between regions. GNNs can represent topological dependencies explicitly, but their computational cost remains high, limiting adoption on lightweight devices [,,,,,,].

Table 1 summarizes the main categories of learning models used in environmental FL and highlights their trade-offs.

Table 1.

Representative learning architectures used in environmental federated learning systems, with their primary use cases, strengths, and limitations.

The table is referred to in several places below (see Section 4.2 and Section 4.4).

While FedAvg remains the baseline algorithm for model aggregation, its performance degrades with non-IID data—a pervasive condition in environmental domains. Improved algorithms such as FedProx and Scaffold stabilize client updates and provide better convergence under heterogeneous data distributions [,].

Recent studies have also combined FedAvg with adaptive weighting, giving more influence to clients that exhibit higher data reliability or lower variance in measurement noise.

4.2. Device-Level Trade-Offs and Energy Awareness

Environmental FL operates across a wide spectrum of edge devices, from microcontrollers embedded in field sensors to GPU-based computing nodes on drones or coastal buoys.

Table 2 compares representative devices by computational power, power demand, and cost.

Table 2.

Comparison of commonly used edge devices in environmental FL deployments and their trade-offs between energy efficiency, cost, and computing capacity.

Raspberry Pi devices are widely adopted due to their low cost and community support, whereas Jetson boards enable more demanding inference tasks such as semantic segmentation or motion tracking.

Energy management remains a key design dimension: solar-powered nodes often employ scheduled training windows or dynamic voltage scaling to balance energy harvesting and computation.

While high-performance units achieve faster local training, lightweight boards often provide greater resilience and longer field autonomy—a recurring trade-off in real-world monitoring networks.

4.3. Communication Architectures and Topologies

Network topology determines the flow of updates between clients and the aggregator, directly influencing efficiency and robustness.

The majority of existing systems rely on a star topology, where each edge node communicates directly with a central coordinator. This architecture is simple to implement but susceptible to latency bottlenecks and central-server dependence.

A growing number of studies are adopting hierarchical FL, introducing fog nodes that act as regional aggregators.

This design significantly reduces communication overhead in wide-area deployments, such as forest monitoring or agricultural cooperatives, by clustering nearby clients.

In mobile or aquatic environments, mesh-based peer-to-peer configurations have been explored, allowing nodes (e.g., drones, boats) to synchronize opportunistically. Hierarchical approaches typically improve scalability and robustness, while mesh systems enhance fault tolerance at the cost of higher coordination complexity [,,].

4.4. Adaptive Aggregation, Non-IID Mitigation, and Security

Environmental data are inherently heterogeneous: variations in soil composition, altitude, or microclimate create statistical divergence among client datasets.

Traditional averaging methods may overweight outlier clients, leading to biased models.

Therefore, adaptive aggregation techniques are increasingly used, weighting updates based on data reliability, signal stability, or measurement completeness. This principle is analogous to uncertainty weighting in geophysical data assimilation and helps stabilize model convergence without sacrificing locality.

Because many environmental FL systems feed directly into decision-support pipelines (e.g., flood forecasting, pest alerts), security and privacy are vital. Recent implementations employ secure aggregation protocols (homomorphic encryption or secret sharing) and differential privacy (DP) to prevent the reconstruction of local information from gradients [,].

Although these techniques can modestly increase computational cost, they enable compliance with data-sovereignty principles and ensure trust in collaborative monitoring.

4.5. Comparative Synthesis and Observed Trends

To understand how these technologies interact across domains, it is helpful to synthesize model types, device classes, and network architectures.

Table 3 provides an integrative overview of selected implementations reported in the recent literature, while the discussion below highlights the key design tendencies.

Table 3.

Representative environmental FL deployments and their architectural configurations.

Across these cases, several broader trends emerge:

- 1.

- Shift from proof-of-concept to operational prototypes.Early studies validated feasibility; recent work integrates FL into functioning monitoring systems, often combining FL with IoT middleware or sensor-management layers.

- 2.

- Convergence between model selection and hardware capacity.CNN-based tasks dominate vision-centric applications, while hybrid statistical models persist where interpretability or low power consumption is essential. Model design is thus dictated more by deployment feasibility than by algorithmic novelty.

- 3.

- Edge intelligence as a sustainability driver.The increasing emphasis on energy-aware scheduling and modular training illustrates that environmental FL is evolving toward energy-conscious intelligence, aligning computational practice with sustainability principles.

- 4.

- Growing importance of explainability and governance.Several projects now include explainable components (e.g., feature-importance reporting or rule-based decision layers), anticipating the integration of ethical oversight frameworks in environmental AI.

Table 3 underscores a clear transition: federated learning in environmental domains is moving from algorithmic exploration toward context-adaptive, resource-balanced ecosystems that prioritize reliability, transparency, and inclusivity over raw performance metrics.

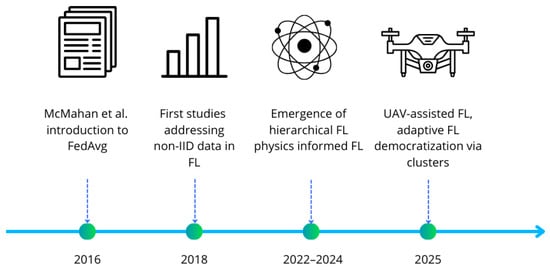

4.6. Evolutionary Timeline

The technological evolution of federated learning in environmental monitoring has not been linear but cyclical—alternating between phases of algorithmic refinement and applied experimentation.

Early implementations were largely conceptual, focusing on communication-efficient aggregation; however, by 2020, the field began converging toward application-driven architectures embedded in sensor and IoT systems. A chronological perspective helps contextualize these shifts and clarifies how methodological innovations translated into practice across domains.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the period from 2016 to 2025 captures several distinct development phases. The initial phase (2016–2018) established the conceptual foundations with the introduction of FedAvg and the first analyses of non-IID data in distributed learning. The translational phase (2019–2021) witnessed the migration of these algorithms into precision agriculture, air-quality modeling, and urban monitoring, emphasizing feasibility and data privacy. The integration phase (2022–2024) brought increasing architectural complexity, marked by the emergence of hierarchical, energy-aware, and physics-informed frameworks such as CorrFL and RuralAI.

Figure 3.

Timeline of key developments in environmental federated learning (2016–2025) [].

Finally, the consolidation phase (2025 onward) is characterized by the convergence of FL with UAV-assisted data collection, adaptive differential privacy, and open-hardware infrastructures—signalling a move toward scalable, democratized environmental intelligence.

Major milestones include the introduction of FedAvg (2016), early research on non-IID handling (2018), first domain-specific applications in precision agriculture and smart cities (2020–2021), emergence of hierarchical and physics-informed architectures (CorrFL, RuralAI) in 2023–2024, and the integration of UAV-assisted training, adaptive privacy, and open-hardware initiatives in 2025. This evolution reflects the discipline’s gradual shift from algorithmic optimization toward robust, context-sensitive deployment across diverse environmental systems [,,,,,,,].

5. Domain-Specific Applications of Federated Learning in Environmental Monitoring

Federated learning (FL) has been explored across a broad spectrum of environmental domains, each characterized by distinct sensing modalities, spatio-temporal scales, and energy or connectivity constraints. While early implementations often replicated industrial FL settings, recent studies have increasingly adapted model architectures and aggregation strategies to the ecological realities of environmental data.

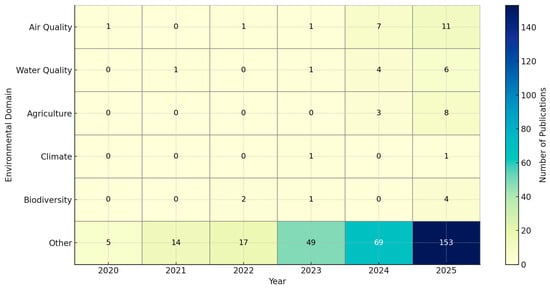

Figure 4 provides an overview of the publication distribution across major domains, highlighting agriculture and air-quality monitoring as dominant research areas, with water and climate applications showing rapid growth since 2022.

Figure 4.

Distribution of reviewed studies by environmental domain (2020–2025). Agriculture and air-quality monitoring dominate the current literature, whereas climate and biodiversity applications are emerging fields with growing interdisciplinary integration. Data also shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Annual and Domain-Specific Publication Counts for Figure 4.

Table 4.

Annual and Domain-Specific Publication Counts for Figure 4.

| Year | Air Quality | Water Quality | Agriculture | Climate | Biodiversity | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| 2021 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 15 |

| 2022 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 17 | 20 |

| 2023 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 53 |

| 2024 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 83 |

| 2025 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 153 | 183 |

| Total | 21 | 12 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 307 | 361 |

The category “Other” includes cross-domain and generalized environmental applications that combine multiple areas such as smart-city monitoring, renewable energy, or integrated IoT–AI systems not specific to a single environmental domain.

5.1. Air-Quality Monitoring

FL has found natural applications in air-quality prediction and pollution source attribution, where sensor networks are spatially dispersed and often governed by different administrative entities.

Edge-based CNN and RNN models have been trained on air-quality indices (AQIs), PM2.5 concentrations, and meteorological variables, enabling local calibration without cross-boundary data exchange.

Hybrid schemes combining FedProx and FedAvg proved effective in mitigating regional bias, particularly when sensors differ in precision or sampling rate []. Several studies demonstrated that hierarchical FL architectures—where city-level hubs aggregate neighborhood sensors—reduce communication load while maintaining consistent prediction accuracy. Compared to centralized learning, these systems offer greater resilience to missing data and communication delays, crucial for real-time alert generation. However, interpretability remains limited: model explanations (e.g., via SHAP or LIME) are rarely transferred to local nodes, hindering transparency for municipal decision-makers [,,,].

5.2. Water-Quality and Hydrological Applications

In aquatic systems, FL addresses privacy and jurisdictional barriers that often prevent data sharing across agencies.

Examples include FL frameworks for river pollution detection, eutrophication prediction, and groundwater level forecasting, typically based on LSTM or GRU architectures [,].

Because hydrological data exhibit strong seasonality and missing values, temporal interpolation and weighted client participation are commonly used to stabilize training. Edge devices deployed in buoy networks or river stations leverage low-power processors, making model compression and quantization indispensable for practical use. Studies comparing centralized and federated LSTM models report near-equivalent predictive skill but with 60–80% lower data transfer volumes, underscoring the suitability of FL for bandwidth-constrained field networks.

An emerging direction involves physics-informed FL, where hydraulic or mass-balance equations are embedded in the loss function, combining data-driven flexibility with domain interpretability.

5.3. Smart and Precision Agriculture

Agriculture represents the most mature domain of environmental FL research, driven by the ubiquity of IoT-enabled farms and commercial interest in privacy-preserving analytics. Typical use cases include crop-yield estimation, soil-moisture prediction, and pest detection from UAV imagery. Lightweight CNNs (e.g., MobileNetV2) are frequently adopted for on-device classification, while federated ensembles (RF + NN) support multi-modal data fusion combining imagery, soil sensors, and weather data [].

Compared with water-quality applications, agricultural FL emphasizes explainability and farmer autonomy: models are often required to provide variable-level insights (e.g., nitrogen, irrigation) rather than only black-box predictions. Energy-aware scheduling—e.g., training during daylight when solar energy is abundant—has also been reported as a distinctive adaptation for agricultural nodes [].

5.4. Climate and Meteorological Forecasting

FL in climate science remains nascent but conceptually transformative.

Distributed training across national meteorological centers enables model personalization without violating data-sovereignty rules.

Several recent studies employed federated convolutional autoencoders and LSTM-based sequence models for temperature, wind, or rainfall prediction, achieving regional adaptation while preserving global coherence []. A particularly promising development is multi-scale FL, in which coarse-resolution climate simulations (e.g., ERA5, CMIP6) guide the aggregation of high-resolution local models. This hybrid approach enhances downscaling performance and could facilitate federated digital twins of regional climate systems. Nevertheless, the integration of physical constraints (e.g., conservation laws) and uncertainty quantification remains underexplored.

5.5. Biodiversity and Ecological Sensing

Applications of FL to biodiversity and ecosystem monitoring are limited but rapidly growing. Projects such as distributed camera traps, underwater microphones, and acoustic bird-detection networks rely on CNN or transformer-based models trained across heterogeneous hardware. In these contexts, federated learning serves both privacy and logistical purposes—allowing collaborations between research institutions, NGOs, and citizen scientists without raw image sharing.

Preliminary results suggest that adaptive client participation (based on dataset size or image quality) improves overall species-recognition performance []. Still, challenges persist in synchronizing model updates under irregular data availability and in ensuring equitable contribution of underrepresented habitats.

5.6. Cross-Domain Comparison and Emerging Insights

Table 5 synthesizes the principal methodological patterns across the domains discussed above, revealing both shared tendencies and context-specific adaptations.

Table 5.

Summary of representative FL applications across environmental domains and their methodological characteristics.

Across these domains, three transversal insights emerge:

- 1.

- Architectural convergence under contextual diversity.Although each domain emphasizes different sensing modalities, the same fundamental FL algorithms (FedAvg, FedProx) recur, adapted through weighting or scheduling to domain constraints.

- 2.

- Trade-offs between interpretability and autonomy.Agriculture and water-quality applications prioritize local explainability, while climate and biodiversity studies focus on global coherence—revealing the spectrum between autonomy and harmonization in FL design.

- 3.

- Progress toward integration with physical and ethical frameworks.A growing subset of works embeds physical models or fairness constraints into FL objectives, signaling a paradigm shift from algorithmic experimentation to sustainable and accountable federated intelligence.

6. Challenges and Open Problems in Federated Environmental Intelligence

Federated learning (FL) faces a complex spectrum of technical, systemic, and institutional barriers that constrain its performance and scalability in environmental applications. These challenges often interact—statistical heterogeneity amplifies communication load, while energy scarcity limits node participation, ultimately degrading accuracy and model reliability.

6.1. Statistical and Algorithmic Challenges

A central problem in environmental FL is the non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed) nature of data. Zhao (2018) [] demonstrated that the accuracy of FL models can decrease by up to 55% when client datasets are highly skewed, emphasizing the need for robust aggregation strategies. Similarly, Lu (2024) [] observed that non-IID distributions not only impair convergence but also increase communication overhead—compounding latency and energy costs in large-scale deployments.

Another persistent limitation arises from model drift and sensor noise, especially in low-cost deployments such as those in precision agriculture. Huangsuwan (2025) [] reported that federated models frequently exhibit client drifting, where weights converge toward local optima rather than a global solution due to statistical heterogeneity. Gao (2022) [] further showed that these local biases, when repeatedly propagated across rounds, can produce systemic model errors that undermine long-term stability and interpretability.

6.2. Communication and Energy Constraints

Connectivity and power limitations are among the defining characteristics of real-world environmental monitoring systems. Behjati (2025) [] highlighted that synchronous FL protocols are often infeasible under such conditions, recommending asynchronous or event-driven update schemes better suited to the episodic, opportunistic nature of ecological sensing. However, these adaptations introduce stale gradient effects and coordination complexity, particularly when nodes operate on intermittent solar or kinetic power.

The energy dimension further complicates deployment. Edge devices powered by batteries or micro-photovoltaic panels must balance local computation with communication frequency. Energy-aware scheduling and federated dropout can extend operational time, but at the cost of slower convergence and reduced model fidelity. This trade-off between accuracy and energy efficiency is a defining constraint in federated environmental intelligence.

6.3. Scalability and Multimodal Integration

Scalability issues arise when monitoring networks integrate heterogeneous sensing modalities, such as humidity, temperature, chemical concentration, and remote imagery.

Duan (2023) [] pointed out that harmonizing such data streams requires significant preprocessing and feature alignment, which may conflict with the decentralized ethos of FL.

Current architectures rarely accommodate cross-modality dependencies or uneven sampling rates, leading to synchronization bottlenecks and high communication overhead. Future systems will need hierarchical or hybrid FL designs capable of multi-scale learning—integrating local specializations while preserving global coherence.

6.4. Explainability, Security, and Governance

Lack of explainability and auditability remains a major obstacle.

Yarham (2025) [] observed that even technically robust FL implementations often fail to provide interpretable outputs.

In citizen-science or policy contexts, such opacity undermines trust, as predictions without transparent rationale risk misinterpretation or rejection.

Equally pressing are security vulnerabilities. Although FL is designed as a privacy-preserving paradigm, Poudel (2025) [] demonstrated that models remain susceptible to gradient inversion and poisoning attacks, especially when cryptographic safeguards are omitted for efficiency. These risks are amplified in resource-constrained deployments, where computational trade-offs often compromise resilience.

Finally, institutional and governance challenges persist in cross-border or multi-stakeholder contexts. Victor (2022) [] highlighted unresolved issues around model ownership, accountability, and conflict resolution when federated updates originate from different jurisdictions. Such issues extend beyond technology—they reflect political and ethical dimensions that must be addressed to establish FL as a trusted framework for environmental intelligence.

6.5. Causal Interactions: Data and Energy Effects on Performance

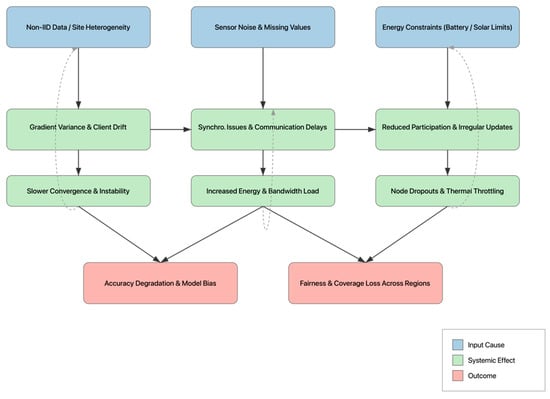

Figure 5 presents a schematic overview of how non-IID data and energy constraints interact to affect FL performance. Heterogeneous data distributions increase gradient variance and slow convergence, leading to greater communication demand and energy expenditure. Limited energy availability, in turn, reduces participation frequency and model diversity, reinforcing bias and diminishing accuracy. These feedback loops form a self-reinforcing cycle that constrains the scalability and fairness of FL in real-world environmental deployments.

Figure 5.

Impact of non-IID data and energy constraints on federated learning performance. Statistical heterogeneity and limited energy supply create coupled feedback loops that degrade accuracy, increase communication load, and hinder model fairness.

Table 6 summarizes the main categories of challenges identified across the reviewed literature, their causal mechanisms, and representative mitigation strategies.

Table 6.

Principal categories of challenges and mitigation pathways in federated environmental intelligence.

7. Future Directions in Federated Environmental Intelligence

Addressing the challenges discussed in the previous section requires a forward-looking perspective that integrates algorithmic, infrastructural, and ethical dimensions of federated learning (FL). The coming decade will determine whether FL can evolve from proof-of-concept experiments into a foundational technology for environmental intelligence, capable of operating under the constraints of data heterogeneity, limited energy availability, and governance complexity.

One central priority is domain-specific personalization. Rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all global model, FL must increasingly adopt localized fine-tuning strategies that account for ecological and climatic heterogeneity. Hybrid approaches alternating between centralized aggregation and local adaptation have proven particularly effective in tasks such as pest detection and river discharge modeling, where local variation is not a source of error but a valuable signal [,]. Techniques such as meta-federation and clustered FL are already emerging to dynamically segment clients by environmental similarity, improving generalization across diverse ecosystems.

Another promising trajectory lies in interfacing FL with physics-based models. Since environmental systems are governed by physical laws such as the conservation of mass and energy, embedding these constraints into federated architectures could enhance both interpretability and sample efficiency. Emerging research demonstrates the integration of partial differential equation (PDE) solvers into neural layers—yielding hybrid physics-informed FL (PI-FL) frameworks capable of enforcing hydrological or thermodynamic constraints locally at the edge [,]. While still computationally expensive, such architectures offer interpretability and physical plausibility often missing from purely data-driven approaches.

Progress will also depend on advances in semantic interoperability. The rapid proliferation of heterogeneous sensors makes it essential to develop shared embedding spaces and ontology-alignment methods so that edge models can effectively exchange knowledge. Recent studies on contrastive federated learning show that data streams as varied as aerial imagery, temperature, and soil chemistry can be harmonized into unified latent representations for cross-modal forecasting in smart agriculture and climate modeling [,]. These innovations will allow knowledge transfer between domains—e.g., using hydrological embeddings to improve flood-prediction models in neighboring regions.

Privacy protection must likewise move beyond simple anonymization. Environmental datasets often contain strategically valuable information, such as aquifer capacity, pollution levels, or biodiversity hotspots. Integrating differential privacy and secure aggregation within FL pipelines has therefore become a central priority, ensuring that sensitive local updates remain protected without degrading model accuracy []. Recent work on adaptive noise injection and gradient clipping demonstrates how privacy budgets can be dynamically adjusted according to environmental context and device energy levels.

Equally critical is the democratization of FL infrastructure. Much of the current research relies on commercial cloud platforms or institutional clusters, resources often unavailable to communities and researchers in the Global South. To widen participation, FL systems should prioritize edge-native, low-energy architectures and open-source toolchains deployable on affordable hardware. Pilot projects using solar-powered Raspberry Pi clusters for biodiversity monitoring and participatory citizen sensing illustrate that inclusive infrastructure can serve as a viable model for equitable scaling [,].

Practical perspectives and real-world demonstrations are also essential for bridging theoretical FL frameworks with actionable environmental intelligence. Recent field-oriented studies in adjacent domains have illustrated how AI-driven, distributed sensing can enhance both ecological and operational sustainability. For example, livestock monitoring systems integrating AI and IoT components have demonstrated measurable gains in animal welfare and environmental efficiency, while AI-assisted decision-support tools for agroecosystems have shown tangible improvements in sustainability-oriented management [,]. These implementations, although not explicitly federated, provide valuable analogs for future real-world FL deployments, highlighting the transition from algorithmic innovation toward practical, domain-integrated intelligence

Finally, governance and ethical frameworks remain underdeveloped. It is not only a question of how models learn, but who defines what is learned, shared, and acted upon. Embedding participatory design, ensuring auditability, and respecting data sovereignty are all essential steps toward legitimacy. Calls for multilateral oversight of transboundary FL initiatives—such as those in marine ecosystem modeling or regional climate-risk forecasting—highlight the need for robust governance structures that extend beyond purely technical considerations [,].

7.1. Technology Roadmap 2025–2035

The evolution of FL will occur along four interdependent layers—Model, Hardware, Governance, and Ethics—each reinforcing the others.

Table 7 summarizes the anticipated milestones between 2025 and 2035, outlining how technical progress must coincide with advances in infrastructure, accountability, and sustainability.

Table 7.

Technical progress needed.

The roadmap shows that progress in federated environmental intelligence will require co-evolution across technical, infrastructural, and ethical dimensions, with sustainability and fairness serving as guiding principles.

7.2. Edge-Native Sustainability Metrics

The environmental footprint of artificial intelligence is now a recognized research challenge, and federated systems must account for carbon efficiency as rigorously as accuracy. Edge-native FL architectures offer an opportunity to make energy use both measurable and optimizable through adaptive scheduling and lightweight telemetry.

Future frameworks will extend the standard optimization objective by incorporating energy- and carbon-weighted loss functions, for instance:

where is the per-round energy expenditure, and represents CO2-equivalent emissions derived from local power source metadata. Scheduling algorithms such as carbon-intensity-aware FedAvg (CI-FedAvg) or energy-proportional client selection can dynamically prioritize nodes using renewable energy or operating under low-carbon grid conditions.

This approach aligns computational efficiency with climate objectives.

Key sustainability indicators for FL include:

- 1.

- Energy per update (J/update)—quantifying energy efficiency of each training cycle.

- 2.

- Carbon cost per inference (gCO2/inference)—measuring deployment emissions.

- 3.

- Thermal efficiency ratio (Teff)—assessing hardware thermal performance versus throughput.

- 4.

- Sustainability score (Ssust)—a composite metric integrating accuracy, uptime, and renewable energy share.

Telemetry protocols such as OpenMetrics, Prometheus exporters, or lightweight MQTT energy monitors can feed these metrics into FL orchestration layers in real time.

By enabling carbon-aware scheduling, FL can transition from being energy-tolerant to energy-optimal, contributing to both computational efficiency and ecological responsibility.

7.3. Integrative Outlook

The future of federated environmental intelligence depends on the systemic integration of algorithmic innovation, hardware sustainability, and transparent governance.

Three converging research streams are expected to define this integration:

- Context-adaptive federated optimization, where participation weights depend on data quality, energy availability, and carbon intensity.

- Cross-domain transfer learning in FL, enabling interoperability across hydrology, meteorology, and biodiversity through shared embedding spaces.

- Self-auditing federated ecosystems, where model updates, data provenance, and energy consumption are cryptographically logged and verifiable.

- At the institutional level, FL should evolve into a trust infrastructure connecting scientific communities, regulators, and local stakeholders.

Mechanisms such as open model registries, participatory governance boards, and algorithmic impact assessments can ensure accountability and legitimacy.

Embedding these principles within environmental monitoring initiatives would make FL not merely a computational tool but a foundation for sustainable digital governance.

Ultimately, progress in this field will hinge on aligning four pillars of innovation:

- (1)

- personalized and physics-informed models,

- (2)

- energy-efficient and carbon-aware infrastructures,

- (3)

- inclusive and participatory governance, and

- (4)

- embedded ethical accountability.

Together, these pillars form the blueprint for federated environmental intelligence that is technically robust, socially equitable, and ecologically sustainable—a system that learns not just from the environment but for the environment itself.

8. Research Gaps and Future Priorities

Despite the rapid progress in federated learning (FL) for environmental monitoring, several critical gaps remain unresolved. These gaps span technical, methodological, and institutional dimensions, and addressing them will be essential for the maturation of the field.

First, there is a clear lack of standardized benchmarks for evaluating FL in environmental domains. Current studies rely on ad hoc datasets—often proprietary, small-scale, or simulated—which makes cross-study comparisons difficult and limits reproducibility. The development of open, shared benchmark datasets and evaluation protocols would significantly accelerate scientific progress.

Second, interpretability and explainability are still underexplored. While accuracy remains a dominant performance metric, decision-making in environmental governance requires models that can justify their predictions in human-understandable terms. Future work must prioritize explainable FL frameworks capable of providing actionable insights to stakeholders such as farmers, regulators, and local communities.

Third, the majority of research to date has focused on proof-of-concept or simulated deployments. Real-world implementations, particularly in cross-border or multi-stakeholder contexts, are rare. Addressing this gap requires field trials that test FL under conditions of unreliable connectivity, energy scarcity, and heterogeneous sensor modalities.

Fourth, security and resilience remain pressing issues. While privacy-preserving techniques such as differential privacy and secure aggregation are gaining traction, FL deployments in environmental systems are still vulnerable to adversarial attacks, including gradient inversion and data poisoning. Research into lightweight, context-aware security mechanisms is urgently needed.

Finally, there are unresolved institutional and governance challenges. Questions of ownership, accountability, and conflict resolution in federated networks are often overlooked in technically oriented studies. Future work should explore participatory governance models and ethical frameworks that ensure inclusivity, fairness, and data sovereignty in federated environmental intelligence.

Together, these gaps outline a research agenda that extends beyond technical optimization. Future priorities must align with ecological realities, emphasize transparency, and ensure equitable access to FL infrastructure and benefits (Table 8).

Table 8.

Research gaps and proposed directions in federated environmental intelligence.

9. Conclusions

Federated learning is no longer a peripheral curiosity in the environmental sciences—it is becoming a central methodological proposition for how we sense, learn from, and respond to complex ecological systems. This review has mapped the state of research at the intersection of FL, environmental sensing, and edge intelligence, drawing on over 300 publications spanning vegetation monitoring, pollution tracking, smart agriculture, water quality, and climate modeling.

The evidence suggests that while federated approaches bring unique advantages—such as privacy-preserving modeling and decentralized learning—their deployment in environmental contexts is far from trivial. Challenges related to data heterogeneity, connectivity, interpretability, and trust remain open and pressing. In particular, we note that assumptions imported from other domains (such as device homogeneity or synchronous data collection) often fail when confronted with the material realities of environmental observation, such as missing data, non-stationary distributions, multi-stakeholder networks, and shifting ecological baselines.

At the same time, emerging trends point to a maturing field. Researchers are beginning to explore physics-informed architectures, hybrid local–global learning loops, cross-modal integration, and ethical frameworks tailored to eco-data. The diversity of hardware platforms—from agricultural drones to underwater buoys—is pushing FL research to account for real-world constraints such as energy, latency, and uneven compute capacity. Moreover, attention is slowly turning from purely technical performance toward broader questions of governance, accountability, and data justice.

What distinguishes environmental federated learning is not only its technical complexity, but its ethical urgency. Decisions informed by these models may impact biodiversity conservation, climate adaptation, and resource management—domains where errors carry ecological and societal cost. It is thus essential that the next wave of FL research moves beyond accuracy benchmarks and towards robustness, fairness, and ecological validity.

In closing, we argue that federated environmental intelligence offers more than a way to train models without sharing data. It represents a deeper epistemological shift: from centralized knowledge extraction to distributed, context-sensitive, and participatory sensing. Realizing this vision will require sustained collaboration across disciplines—not only computer scientists and engineers, but also ecologists, social scientists, and communities on the frontline of environmental change.

The work is just beginning. But the potential—for learning systems that are as distributed, adaptive, and resilient as the ecosystems they study—is immense.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M.; methodology, T.M., I.D., E.K. and A.P.; investigation, T.M., I.D., E.K. and A.P.; T.M., I.D., E.K. and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M., I.D., E.K. and A.P.; writing—review and editing,. T.M., I.D., E.K. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DP | Differential Privacy |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| FedAvg | Federated Averaging |

| FedProx | Federated Proximal Optimization |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| non-IID | Non-Independent and Identically Distributed |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equation |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Ramakrishnan, J. Achieving High Efficiency and Privacy in IoT With Federated Learning: A Verifiable Horizontal Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 48587–48604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballotta, L.; Fabbro, N.D.; Perin, G.; Schenato, L.; Rossi, M.; Piro, G. VREM-FL: Mobility-Aware Computation-Scheduling Co-Design for Vehicular Federated Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 3311–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, K.A.; Ud Din, I.; Almogren, A.; Nawaz, A.; Khan, M.Y.; Altameem, A. SecEdge: A Novel Deep Learning Framework for Real-Time Cybersecurity in Mobile IoT Environments. Heliyon 2025, 11, e40874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Peng, C. A Novel User Behavior Modeling Scheme for Edge Devices with Dynamic Privacy Budget Allocation. Electronics 2025, 14, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhao, X.; Pedrycz, W. A Robust Federated Biased Learning Algorithm for Time Series Forecasting. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albelaihi, R. Mobility Prediction and Resource-Aware Client Selection for Federated Learning in IoT. Future Internet 2025, 17, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, G.N.N.; Mattos, D.M.F. A Practical Evaluation of a Federated Learning Application in IoT Device and Cloud Environment. JBCS 2025, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximing, C.; Xilong, H.; Du, C.; Tiejun, W.; Qingyu, T.; Rongrong, C.; Jing, Q. FedMEM: Adaptive Personalized Federated Learning Framework for Heterogeneous Mobile Edge Environments. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Hossain, M.S. Semi-Supervised Federated Learning for Digital Twin 6G-Enabled IIoT: A Bayesian Estimated Approach. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 66, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Li, Z. A Blockchain Multi-Chain Federated Learning Framework for Enhancing Security and Efficiency in Intelligent Unmanned Ports. Electronics 2024, 13, 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Khajavi, K.; Jafari Siavoshani, M.; Jahangir, A.H. A Multi-Agent Adaptive Deep Learning Framework for Online Intrusion Detection. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, L.; Li, X.; Han, S. System-Level Digital Twin Modeling for Underwater Wireless IoT Networks. JMSE 2024, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaji, E.M.; El Hajla, S.; Maleh, Y.; Mounir, S. Adversarially Robust Federated Deep Learning Models for Intrusion Detection in IoT. IJEECS 2025, 37, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. AFM-DViT: A Framework for IoT-Driven Medical Image Analysis. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 113, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Saeed, U.; Koo, I. FedLSTM: A Federated Learning Framework for Sensor Fault Detection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, X.; Gupta, A. UAV Trajectory Control and Power Optimization for Low-Latency C-V2X Communications in a Federated Learning Environment. Sensors 2024, 24, 8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, T.; Paramana, P.P.D.; Lin, C.-C.; Agarwal, S.; Verma, R. Federated Learning-Driven IoT System for Automated Freshness Monitoring in Resource-Constrained Vending Carts. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Popli, M.; Singh, R.P.; Kaur Popli, N.; Mamun, M. A Federated Learning Framework for Enhanced Data Security and Cyber Intrusion Detection in Distributed Network of Underwater Drones. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 12634–12646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Bagubali, A. Federated Learning With Sailfish-Optimized Ensemble Models for Anomaly Detection in IoT Edge Computing Environment. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 53171–53187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbey, R.A.; Jamil, F. Federated Learning Framework for Real-Time Activity and Context Monitoring Using Edge Devices. Sensors 2025, 25, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, L.K.G.; Appiah, S.Y.; Mantey, V.A.; Danlard, I.; Akowuah, E.K. Computationally Efficient Deep Federated Learning with Optimized Feature Selection for IoT Botnet Attack Detection. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 25, 200462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncel, Y.K.; Öztoprak, K. SAFE-CAST: Secure AI-Federated Enumeration for Clustering-Based Automated Surveillance and Trust in Machine-to-Machine Communication. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albogami, N.N. Intelligent Deep Federated Learning Model for Enhancing Security in Internet of Things Enabled Edge Computing Environment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, M.; Khemakhem, M.A.; Alhebshi, R.M.; Alsulami, B.S.; Eassa, F.E. RPFL: A Reliable and Privacy-Preserving Framework for Federated Learning-Based IoT Malware Detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takele, A.K.; Villányi, B. Resource-Efficient Clustered Federated Learning Framework for Industry 4.0 Edge Devices. AI 2025, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eladl, S.G.; Haikal, A.Y.; Saafan, M.M.; ZainEldin, H.Y. A Proposed Plant Classification Framework for Smart Agricultural Applications Using UAV Images and Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 109, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Ishibashi, K. Adaptively Weighted Averaging Over-the-Air Computation and Its Application to Distributed Gaussian Process Regression. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, F.R.; He, J.; Das, B.; Dharejo, F.A.; Zhu, N.; Khan, S.B.; Alzahrani, S. Adaptive Federated Learning for Resource-Constrained IoT Devices through Edge Intelligence and Multi-Edge Clustering. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Wang, M.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, L.; Yu, S.; Zhou, W. Federated Learning With Blockchain-Enhanced Machine Unlearning: A Trustworthy Approach. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2025, 18, 1428–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benila, S.; Devi, K. Federated Synergy: Hierarchical Multi-Agent Learning for Sustainable Edge Computing in IIoT. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 68311–68322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitendra Chandnani, C.; Agarwal, V.; Chetan Kulkarni, S.; Aren, A.; Amali, D.G.B.; Srinivasan, K. A Physics-Based Hyper Parameter Optimized Federated Multi-Layered Deep Learning Model for Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21992–22010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccialli, F.; Chiaro, D.; Qi, P.; Bellandi, V.; Damiani, E. Federated and Edge Learning for Large Language Models. Inf. Fusion 2025, 117, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficili, I.; Giacobbe, M.; Tricomi, G.; Puliafito, A. From Sensors to Data Intelligence: Leveraging IoT, Cloud, and Edge Computing with AI. Sensors 2025, 25, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsenani, Y. FAItH: Federated Analytics and Integrated Differential Privacy with Clustering for Healthcare Monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniran, I.A.; Nazeer, M.; Wong, M.S.; Chan, P.-W. An Improved Machine Learning-Based Model for Prediction of Diurnal and Spatially Continuous near Surface Air Temperature. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devaraj, H.; Sohail, S.; Ooi, M.; Li, B.; Hudson, N.; Baughman, M.; Chard, K.; Chard, R.; Casella, E.; Foster, I.; et al. RuralAI in Tomato Farming: Integrated Sensor System, Distributed Computing, and Hierarchical Federated Learning for Crop Health Monitoring. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaer, I.; Shami, A. CorrFL: Correlation-Based Neural Network Architecture for Unavailability Concerns in a Heterogeneous IoT Environment. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manage. 2023, 20, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjati, M.; Alobaidy, H.A.H.; Nordin, R.; Abdullah, N.F. UAV-Assisted Federated Learning with Hybrid LoRa P2P/LoRaWAN for Sustainable Biosphere. Front. Commun. Netw. 2025, 6, 1529453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwabli, A. Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Air Quality Forecasting Using IoT Sensors. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 16069–16076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Lai, L.; Suda, N.; Civin, D.; Chandra, V. Federated Learning with Non-IID Data. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.00582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Pan, H.; Dai, Y.; Si, X.; Zhang, Y. Federated Learning With Non-IID Data: A Survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 19188–19209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangsuwan, K.; Liu, T.; See, S.; Beng Ng, A.; Vateekul, P. FedDrip: Federated Learning With Diffusion-Generated Synthetic Image. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 10111–10125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Fu, H.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Xu, C.-Z. FedDC: Federated Learning with Non-IID Data via Local Drift Decoupling and Correction. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 10102–10111. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.-H.; Li, W.; Zou, D.; Li, R.; Lu, S. Federated Learning with Data-Agnostic Distribution Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 8074–8083. [Google Scholar]

- Yarham, S.; Behjati, M.; Alobaidy, H.A.H.; Majeed, A.P.P.A.; Zheng, Y. Enhancing Air Quality Monitoring: A Brief Review of Federated Learning Advances. In Selected Proceedings from the 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Manufacturing and Robotics, ICIMR 2024, 22–23 August, Suzhou, China; Chen, W., Pp Abdul Majeed, A., Ping Tan, A.H., Zhang, F., Yan, Y., Luo, Y., Huang, L., Liu, C., Zhu, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 1316, pp. 489–501. ISBN 978-981-96-3948-9. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, S.; Sainju, A.M.; Upadhyay, K. Privacy Meets Conservation: Federated Learning’s Revolution in Deforestation Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT), Seattle, WA, USA, 28 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, N.; Rajeswari, C.; Alazab, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Magnusson, S.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Ramana, K.; Gadekallu, T.R. Federated Learning for IoUT: Concepts, Applications, Challenges and Opportunities. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.13976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; He, B. A Survey on Federated Learning Systems: Vision, Hype and Reality for Data Privacy and Protection. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 35, 3347–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosain, M.T.; Abir, M.R.; Rahat, M.Y.; Mridha, M.F.; Mukta, S.H. Privacy Preserving Machine Learning With Federated Personalized Learning in Artificially Generated Environment. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 5, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Hong, Y.; Ling, X.; Wang, L.; Ran, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, W.H.; Chen, Z.; Cao, Y. Differentially Private Federated Learning: A Systematic Review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.08299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriya, Y.; Gadekallu, T.R. A Survey on Soft Computing Techniques for Federated Learning- Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. J. Data Inf. Qual. 2023, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokade, M.D. Advancements in Privacy-Preserving Techniques for Federated Learning: A Machine Learning Perspective. JES 2024, 20, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A. Privacy-Centric AI: Navigating the Landscape with Federated Learning. IJRASET 2024, 12, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.A.S. Artificial Intelligence-Powered Carbon Market Intelligence and Blockchain-Enabled Governance for Climate-Responsive Urban Infrastructure in the Global South. J. Eng. Res. Rep. 2025, 27, 440–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, P.M. Federated Learning: Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, T.; Jiang, P.; Qi, A.; Deng, L.; Liu, Z.; He, Y. A Forest Wildlife Detection Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Animals 2023, 13, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamara, N.; Islam, M.D.; Bai, G.F.; Shi, Y.; Ge, Y. Ag-IoT for Crop and Environment Monitoring: Past, Present, and Future. Agric. Syst. 2022, 203, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, D.A.; Adepoju, A.G. Establishing Ethical Frameworks for Scalable Data Engineering and Governance in AI-Driven Healthcare Systems. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2025, 6, 8710–8726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, F. Federated Learning in the Era of Data Privacy: An Exhaustive Survey of Privacy Preserving Techniques, Legal Frameworks, and Ethical Considerations. IJFEI 2025, 2, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).