Abstract

Hate speech is a form of communicative expression that promotes or incites unjustified violence. The increase in hate speech on social media has prompted the development of automated tools for its detection, especially those that integrate emotional tone analysis. This study presents a systematic review of the literature, employing a combination of PRISMA and PICOS methodologies to identify the most used Machine Learning techniques and Natural Language Processing emotion classification in hostile messages. It also seeks to determine which models and tools predominate in the analyzed studies. The findings highlight LLaMA 2 and HingRoBERTa, achieving F1 scores of 100% and 98.45%, respectively. Furthermore, key challenges are identified, including linguistic bias, language ambiguity, and the high computational demands of some models. This review contributes an updated overview of the state of the art, highlighting the need for more inclusive, efficient, and interpretable approaches to improve automated moderation on digital platforms. Additionally, it includes techniques, methods, and future directions in this topic.

1. Introduction

The use of social networks has transformed the ways we communicate, interact, and disseminate opinions. However, these environments facilitate the spread of hate speech and cyberbullying, which most severely impact vulnerable groups. This form of digital violence generates various psychological, social, and emotional effects, making the automated detection of this discourse a research challenge.

This research aims to identify hate speech on social networks using techniques based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML), considering emotional tone as a component to improve the accuracy of detection models.

NLP also addresses situations related to offensive language in digital environments. In particular, the use of transformers marked a breakthrough in the accuracy of automatic text classification systems [1]. However, traditional approaches based on sentiment polarity are insufficient to capture the emotional complexity present in hostile messages.

On the other hand, emotion analysis has become established as an alternative that allows us to identify whether a message conveys a negative emotion, as well as to distinguish the type of emotion expressed, such as anger, fear, or sadness [2]. This capability is valuable when hate speech is expressed indirectly or ambiguously, making it difficult to detect using conventional methods [3]. Therefore, systems that incorporate emotion analysis can obtain greater sensitivity to implicit hostility patterns.

Furthermore, the use of a multimodal architecture enables the integration of contextual, linguistic, and behavioral cues, thus improving the accuracy of tasks such as the detection of cyberbullying [4]. Furthermore, recent studies have indicated that emotion classification also expands the models’ ability to adapt to texts in minority languages or with dialectal variation [5].

Another aspect to consider is the application of multilingual and multi-technique models that analyze content in different cultural and linguistic contexts, which is key to addressing the diversity of hate speech directed at women on a global scale [6]. Furthermore, the use of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques gained relevance by providing transparency in the models’ decisions and strengthening their reliability in sensitive contexts [7].

To organize and systematize recent research on this topic, we conducted a structured review using the PRISMA methodology [8]. The PICOS model was also used to formulate research questions precisely, delimiting the population as social media users, the intervention as the use of NLP, ML, emotional analysis, the comparison between traditional and advanced models and the result in terms of system precision [9].

The results show the most widely used techniques for classifying emotions and hate speech, the methods employed by researchers, the most commonly recognized emotions, the main methodological challenges, the opportunities and gaps identified in the use of these techniques, the models that report the best performance according to metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score, as well as lines of future research. This information is presented in a structured manner that facilitates an understanding of the current state of the field, its advances, limitations, and emerging trends.

Among the contributions of this study are (i) the characterization of the NLP techniques and ML models most used in the classification of emotional tone in hate speech, based on the analysis of their frequency and the role they play in the textual analysis process; (ii) the identification of the most frequently used methods and algorithms and the models that report the best results according to the evaluation metrics for classification models; (iii) an updated overview available to researchers on existing strategies for emotional and hate speech detection, facilitating comparison between approaches and highlighting those that show the most excellent effectiveness; and (iv) a list of the challenges, opportunities and lines of future research, among which are the integration of the emotional dimension, the improvement in tone moderation in hate speech on social networks, and the definition of adequate criteria for the selection and training of artificial intelligence models, as a fundamental part in the construction of software artifacts oriented to its prevention.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 details the procedure used for bibliographic research, combining the PRISMA and PICOS methodologies. Section 3 presents the results obtained from the 34 primary studies included in this review. Section 4 analyzes and interprets these findings in relation to the research questions. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of this study and outlines future lines of work.

2. Materials and Methods

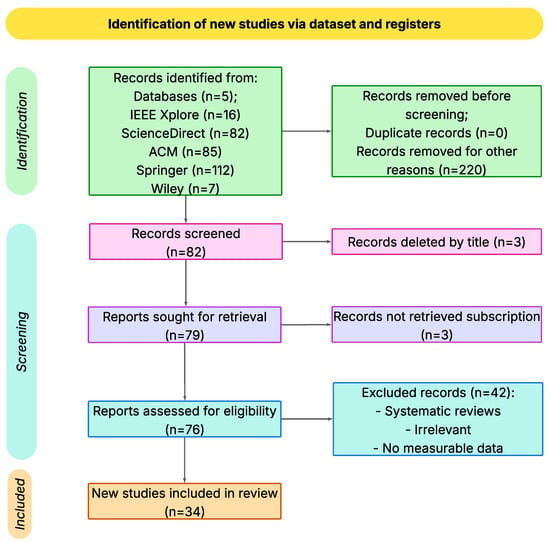

This section outlines the methodological process employed in conducting the systematic review of the literature, which was based on the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Material). PRISMA entails a methodical strategy aimed at conducting systematic reviews, ensuring transparency and methodological rigor throughout the review process [1]. PRISMA establishes a set of criteria for the research process, from the collection and selection of articles to the analysis and interpretation of results [10]. Figure 1 illustrates the flow chart that outlines the selection of studies and the application of the checklist, which ensures a clear and comprehensive presentation of the methods and results [8]. It also shows the total number of records processed, the criteria applied in each phase, and the final number of primary studies selected. Within this methodological approach, we conducted a critical evaluation of the selected studies, considering key elements such as study design, data quality, evaluation of classification model metrics (i.e., precision, recall, F1-score) and clarity of the description of the NLP techniques and machine learning models employed [11,12]. This assessment enabled us to select relevant studies, considering the quality of their content and results.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA 2020 flowchart illustrates the procedure and preliminary results of this research. Source: Adapted from [8].

2.1. Protocol Registration

This systematic review has been registered with the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY). The protocol, entitled “Emotional Tone Detection in Hate Speech Using Machine Learning and NLP: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions, a Systematic Review”, has been accepted and published on the INPLASY website (https://www.inplasy.com). The assigned registration number is INPLASY2025110006, and the corresponding Digital Object Identifier (DOI) is 10.37766/inplasy2025.11.0006. This registration ensures transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor throughout the systematic review process, in alignment with international reporting standards.

2.2. Research Questions

Given that this study focuses on selecting machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP) methods and techniques used to detect the emotional tone of hate speech against women present on social networks, which perpetuates inequality and gender stereotypes, it is crucial to identify where the line between current knowledge and ignorance lies [13]. Below, we establish the relevant research questions.

- RQ1: What are the most commonly used NLP and machine learning techniques to detect emotional tone and/or hate speech on social networks?

- RQ2: What tools do authors use to implement NLP and machine learning techniques to detect hate speech and/or emotional tone on social media?

- RQ3: What are the most detected emotions in hate speech?

- RQ4: What are the main challenges, limitations, and future research directions for using NLP and machine learning techniques to detect emotional tone in hate speech?

- RQ5: Which NLP or machine learning models perform best in the classification of emotional tone based on metrics such as precision, recall, or the F1 score?

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

We included only empirical studies that employed NLP techniques and/or ML models to detect the emotional tone present in hate speech or closely related forms of abusive communication. Since NLP and ML encompass a variety of approaches, we limited our selection to studies that described reproducible methodologies, explained their models in sufficient detail, and reported quantitative metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, or F1-score. Furthermore, we only considered articles written in English, published between 2019 and 2025, and that used datasets explicitly linked to hate speech, toxicity, cyberbullying, or offensive language on social media.

During the initial identification phases, we excluded 220 records due to non-eligibility under these criteria. These included duplicate entries across databases, irrelevant articles based on their titles or abstracts, studies published outside the established time frame, articles written in languages other than English, and studies whose full texts could not be viewed or were unavailable for review. These exclusions correspond to the category of “other reasons” represented in Figure 1.

2.4. Data Sources

We selected IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM Digital Library, Springer, and Wiley databases, because they concentrate the majority of scientific output in engineering, data science, computer science, and disciplines associated with NLP and ML. These platforms include recent empirical articles, high-impact conferences, and applied studies that address issues related to hate speech, toxicity, and emotional analysis on social networks.

Furthermore, we prioritized these databases due to their thematic specialization. IEEE Xplore and ACM Digital Library are repositories covering artificial intelligence, NLP, text classification, and content analysis; ScienceDirect and Springer contribute multidisciplinary research, computational modeling, and computational social sciences; and Wiley provides relevant publications in behavioral science, computational linguistics, and affective computing.

Regarding databases such as Web of Science (WoS) or Scopus, we decided not to include them because we verified that the relevant studies indexed in WoS were already available in the selected databases, so their inclusion would not have provided new primary records. Finally, WoS is a restricted-access platform, and we did not have institutional access, which limited its use in this study.

2.5. Search Strategy

We applied the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design) method to develop our search strategy, allowing for more precise and targeted search strategies. In addition, this achieves greater precision in retrieving relevant studies by simplifying the identification of studies that meet the established criteria in each category. Therefore, PICOS improves the process of selecting and analyzing the available scientific evidence [9]. Table 1 lists the components of the method:

Table 1.

Components of PICOS.

- P: “Hate Speech”, “Online Hate Speech”, “Hate Speech Against Women”, “Offensive Messages on Social Media”, “Hate Messages Against Women”, “Emotional tone”.

- I: “Natural Language Processing”, “Machine Learning”, “Techniques”, “Classification”, “Supervised/Unsupervised Machine Learning”, “RNN”, “BERT”, “GPT”, “Emotion Detection”.

- C: “Deep Learning Models and Pre-Trained Embeddings vs. Traditional NLP Classification Techniques”.

- O: “Precision”, “Accuracy”, “Recall”, “Detection Rate”, “Precision”, “F1-Score”, “False Positive Rate”, “False Negative Rate”.

- S: “Empirical Studies”, “Comparative Analyses”, “Correlational Studies”, “Inferential Statistical Analysis”.

We then defined the search strings and their variants using PICOS, combining terms with Boolean operators to create a comprehensive search. We applied the following search strings to each digital database. Table 2 presents the number of articles found.

Table 2.

Articles found according to the search strings applied.

We conducted initial searches in April 2025 using the databases listed above, which were selected for their availability and access to scientific literature. We subsequently expanded the search strategy by identifying keywords related to the PICOS method, combined with the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” as described in Table 2, yielding a total of 302 articles. Before proceeding with the selection of articles. We defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria described below.

2.6. Inclusion Criteria

- Primary studies using NLP and ML techniques to detect emotional tone in hate speech.

- Only studies with quantitative results, i.e., with precise measurements.

- Written only in English.

- From the last 6 years (2019–2025).

2.7. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies that do not present empirical results related to the detection of emotional tone in hate speech.

- Research using data sets that are unrepresentative, irrelevant, or unrelated to hate speech.

- Studies that lack a precise, reproducible, and evaluable methodology for the classification of emotions.

- Studies focused on theoretical or conceptual aspects of natural language processing or machine learning without providing applicable or measurable results.

2.8. Data Classification

We collect data from selected primary articles related to the natural language processing and machine learning techniques used. We focus on the validation methods and techniques used, the datasets applied (including, when reported, their size and class distribution), the software artifacts implemented, and the evaluation metrics for the classification of emotional tone in hate speech. In addition, for each primary study we recorded the publication year and the type of classification model (traditional machine learning, deep learning, Transformer-based, or LLM-based), which later allowed us to analyse how the choice of models evolved over time and how it relates to data and resource constraints.

2.9. Dataset Analysis

This section describes the datasets used in the selected studies. For comparative analysis, studies were included that reported sufficient information about the corpus used, including dataset type, language, size, emotion labels, and the divisions used for training, validation, and testing. The datasets exhibit variations in label granularity, imbalance level, and annotation methods (manual or automatic); therefore, these characteristics are recorded to highlight the differences between approaches.

For each study, we collected the following labels: the defined emotion, the total number of samples, the availability of distribution information by label, and the standard divisions used in the training process. When any element was not available in the original publication, the label “NR” (Not Reported) was used.

Table 3 summarizes this information and the differences between the corpora used in the analyzed studies.

Table 3.

Summary of datasets used in the selected studies.

2.10. Evaluation Methods

We considered various evaluation strategies to assess the performance of emotion-detection models for hate speech. The main ones included simple hold-out (training-and-test) splits, k-fold cross-validation, stratified partitioning, and the use of external test sets. Table 4 shows the evaluation strategies used in the analyzed studies.

Table 4.

Evaluation methods used in the selected studies.

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained. In summary, we identified 82 relevant articles compiled from scientific databases, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM, Springer, and Wiley, as shown in Figure 1. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we eliminated 48 articles that did not focus on the classification of emotional tone in hate speech using NPL and ML techniques, were not empirical studies, and did not present quantitative results. Therefore, we selected 34 primary articles for analysis. Subsequently, each article was read, reviewed, and studied to answer the research questions individually and classify the collected information. We present the analysis of the results below, grouped by each research question:

- RQ1: What are the most used NLP and machine learning techniques for detecting emotional tone and/or hate speech on social media?

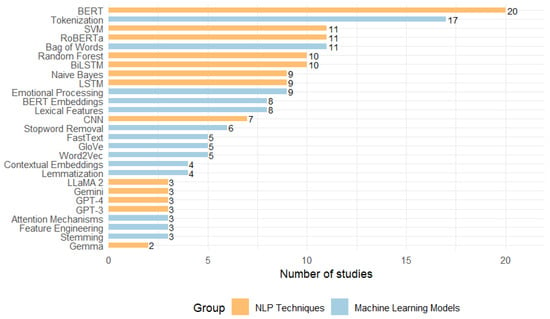

We identified several NLP techniques for detecting emotional tone in hate speech. Their respective references are listed in Table 5, sorted in descending order by number of articles (i.e., “frequency”). We also include a “category” column, which indicates the function of each technique within the language processing pipeline. This classification distinguishes whether the method corresponds to text preprocessing, vector representation, feature extraction, and semantic or emotional analysis.

Table 5.

Techniques using NLP are found in SLR.

Table 5 lists the most common techniques. The most used method is tokenization (17 studies), a part of textual preprocessing, followed by the bag-of-words (11 studies) approach, a classic textual representation technique. Within semantic and emotional analysis, emotional processing is particularly notable (9 studies). Approaches linked to feature extraction and modern contextual representation, such as lexical features and BERT embeddings (each with eight studies), are also common. Other relevant techniques include stopword removal (in 6 studies) and vector representations, such as Word2Vec, GloVe, and FastText (each with five studies). In addition, linguistic normalization methods are identified, such as lemmatization and contextual embeddings (4 studies). Additionally, we find other less frequently used techniques such as stemming, feature engineering, and attention mechanisms (3 studies).

The frequency of use of NLP techniques reveals the most widely used tools and, at the same time, indicates how the field is evolving. We find the simultaneous presence of traditional approaches, such as the bag-of-words model, alongside recent models, including BERT and attention mechanisms. The results demonstrate that classical techniques play a functional role due to their low computational cost and ease of implementation in diverse environments. At the same time, the growing use of contextual embedding reflects a trend toward models that account for the context in which words are used, which is key to identifying the emotional tone in hate speech.

On the other hand, the infrequent use of methods such as stemming, feature engineering, and attention mechanisms raises questions about their effectiveness, the limited number of studies that evaluate them in depth, and how to establish the choice of techniques in future studies. Table 6 shows the ML models, along with their frequency, references, and model type, arranged in descending order.

Table 6.

Machine Learning Models.

In Table 6, we highlight that pre-trained Transformer architectures clearly dominate the period under study, with BERT being the most widely used model (20 studies), followed by RoBERTa and the SVM classifier (11 studies each). We also observe a high prevalence of traditional models, such as Random Forest, a tree-based classifier, and Naive Bayes, a probabilistic classifier, as well as neural architectures such as LSTM, BiLSTM, and CNN. All of the above reflect their continued validity in tasks of emotional tone classification in hate speech.

The Publication Years column shows how these models are distributed over time. BiLSTM, LSTM, and CNN appear in the earliest primary studies in our review window (2020 and 2021), while BERT and RoBERTa are first used from 2021 onwards and are present in studies published up to 2025. In contrast, LLM-based models such as GPT-3, GPT-4, LLaMA 2, Gemini, and Gemma appear only in articles published in 2024 and 2025. They are still cited in only a comparatively small number of studies (i.e., two or three per model).

When we analyse the models chronologically, a clear pattern emerges. The earliest works rely mainly on traditional classifiers (SVM, Random Forest, Naive Bayes) and on recurrent or convolutional neural networks (LSTM, BiLSTM, CNN). As we move to more recent years, most new studies adopt BERT-like architectures as their main backbone, and only in the most recent works (2024 and 2025) do LLM-based approaches start to be explored, typically in zero-shot or few-shot settings. This temporal evolution indicates that the use of traditional models in earlier studies was primarily determined by the state of the art and the limited availability of LLMs at the time of publication, rather than arbitrary design choices. At the same time, some recent studies continue to employ classical models when they operate on small, highly imbalanced datasets or in contexts where interpretability and reduced computational cost are prioritised. Figure 2 presents a visual representation of the results summary for RQ1, facilitating the identification of the NLP techniques and ML models most used in classifying emotional tones in hate speech [43].

Figure 2.

Most frequent techniques and models in the classification of the emotional tone of hate speech using ML and NLP.

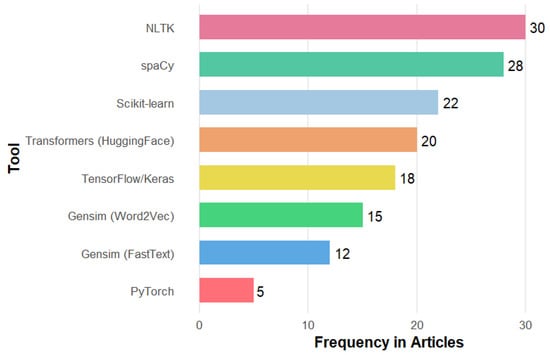

- RQ2: What tools do authors use to implement NLP and machine learning techniques for detecting hate speech and/or emotional tone on social media?

Given this research question, the uniform implementation of preprocessing with NLTK and Spacy addresses the need to manage the variability and noise inherent in social media language. Rodriguez et al. [16] highlights that NLTK facilitates tokenization, stopword removal, and the integration of custom dictionaries to filter hashtags and URLs. On the other hand, Chakraborty et al. [28] note that Spacy accelerates processing through its architecture, which uses static vectors that enable efficient lemmatization of large volumes of text, thereby reducing computational costs compared to other libraries.

For static lexical representation, the authors opted for Word2Vec and FastText via Gensim, not only because of their ease of use but because both models can be quickly trained on specialized corpora. Koufakou et al. [20] showed that Word2Vec effectively captures fine-grained semantic relationships between offensive terms and their contexts. Finally, Alaeddini [35] uses FastText to handle mixed code (Hindi-English) robustly and neologisms, thereby improving coverage of rare or emerging vocabulary.

The leap towards contextual embedding is supported by the adoption of Hugging Face’s Transformers library. Alvarez-Gonzalez et al. [26] compare BERT and RoBERTa in emotion detection tasks on Twitter and report that these models increase the F1-score by up to 7% compared to Word2Vec. The authors place particular emphasis on disambiguating irony and double entendres (i.e., two interpretations) common in hate speech. Ngo and Kocoń [36] reinforces this finding by combining contextual embeddings with user features to improve multimodal classification.

In the modeling phase, however, the preference for Scikit-learn (SVM, Random Forest, Naive Bayes) stems from its stability and transparency; this preference was valued in studies that require interpretability, such as Min et al. [3], which used Scikit-learn to design a multi-label self-training scheme where cross-validation yields reproducible results.

On the other hand, TensorFlow/Keras and PyTorch are the core deep learning frameworks identified among the primary studies. In Al-Hashedi et al. [15], the authors implement a CNN–BiLSTM architecture with attention and an emotional lexicon using TensorFlow 2.9 and Keras 2.9. Meanwhile, Paul et al. [4] developed a multimodal Transformer in PyTorch 2.0 with cross-attention that integrates text, emojis, and metadata.

Figure 3 shows the frequency of use of each tool, with the upper end dominated by the Natural Language Toolkit (30 studies) and spaCy (28 studies), which serve as pillars of preprocessing, ensuring the cleaning and normalization of the text before any other phase. Subsequently, the bars for Scikit-learn (22 studies) and Transformers (20 studies) indicate a shift toward feature extraction and a comparison between classical methods and advanced embeddings. In the middle positions, Word2Vec (15 studies) and FastText (12 studies) confirm their complementary role as static representations. At the same time, the shorter TensorFlow/Keras (18 studies) and PyTorch (5 studies) studies show that deep architectures are only applied when more complex modeling is required.

Figure 3.

Most frequently used tools to detect emotional tone in hate speech identified in the SLR.

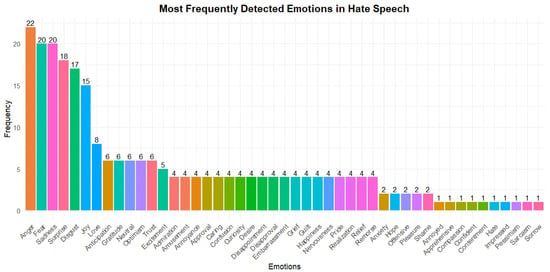

- RQ3: What are the most detected emotions in hate speech?

The emotions most frequently detected in hate speech are consistent with the findings of psychologist Paul Ekman. Ekman developed the theory of basic emotions, which posits the universality of six emotions: joy, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. These emotions are among the most commonly used in computer science research [44], are strongly perceived, and are easily distinguishable.

To ensure comparability between studies using different emotion taxonomies, we developed a mapping of the emotion labels. While many studies adopt Ekman’s six basic emotions, others employ Plutchik’s model, custom taxonomies, or labels specific to each dataset. Therefore, we grouped all the labels into normalized categories aligned with the most commonly used emotion models in the literature. Table 7 shows this mapping and indicates how frequently each category appears in the studies, along with an assessment of the associated predictive difficulty based on the reported results.

Table 7.

Emotional categories, example labels, and frequency of appearance in the 34 primary studies.

As a complement to Table 7, it is possible to identify several patterns related to prediction difficulty. Emotions such as anger and disgust tend to be easier to classify because they often contain explicit lexical markers, such as insults, dehumanizing expressions, or direct hostility. In contrast, emotions such as fear and sadness are more context-dependent and are often expressed implicitly, leading to lower recall values in many models. Positive emotions, such as joy, love, and gratitude, pose the most significant challenge, as they often appear in ironic or sarcastic constructions that mask hostile intentions. Finally, infrequent emotions (i.e., shame, guilt, humiliation, confusion) show volatile performance due to their limited representation in the datasets.

In this context, we highlight that the most frequently detected emotions are anger (22 studies), followed by fear and sadness (each with 20 studies), surprise (18 studies), and disgust (17 studies). These represent responses to basic emotions in the face of threats or conflict, and they frequently appear in hate speech. This trend is supported by studies such as that of Kastrati et al. [14]. They labeled 17.5 million tweets using distant supervision, aligning emojis with the Ekman model, and found that anger, sadness, disgust, and fear were the most recurrent emotions in hate speech. Similarly, the study by Min et al. [3] analyzed three hate speech datasets and concluded that the same emotions were dominant when classifying messages with violent and discriminatory content.

Likewise, in this study, we identified emotions considered positive, such as happiness (15 studies), love, and gratitude (each in 6 studies). The presence of these emotions may be related to the ironic or ambiguous use of language, which is common in contexts where affective expressions are used to reinforce hostile discourse indirectly, as mentioned by Baruah et al. [5] and Al-Hashedi et al. [15], where speeches are analyzed that, although they seem positive, are loaded with hate or double meanings. Although these emotions do not dominate automatic analysis, they enable us to explore the sarcastic dimensions of discourse.

Finally, more than 40 different emotions were detected, demonstrating the emotional complexity behind hate speech, mainly when directed at vulnerable groups. The presence of negative emotions reinforces the notion that this type of speech is characterized by hostility, threat, and rejection. By studying these emotions, we find them extremely useful for training emotional classification models. The distribution of emotions found in this study is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the most frequently identified types of emotions.

- RQ4: What are the main challenges, limitations, and future research directions for using NLP and machine learning techniques for detecting emotional tone in hate speech?

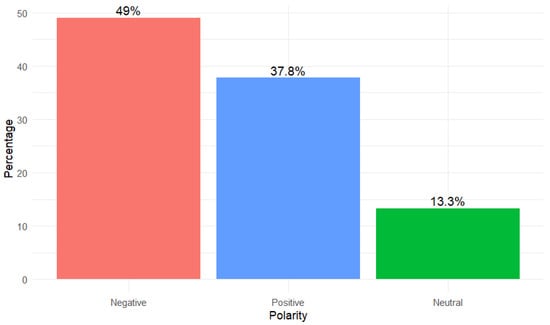

Automating emotional tone detection in hate speech faces a first challenge: emotional polarity. Traditionally, many methods rely on classifying each text as negative, positive, or neutral, but in the context of hate speech, this approach is insufficient. As shown in Figure 5, almost half of the hostile messages (49%) are labeled as negative, but a surprising 37.8% appear with a positive polarity, and 13.3% are labeled as neutral. This distribution indicates the frequency of sarcasm, irony, or “hostility camouflaged” with friendly expressions, causing models based solely on polarity to overlook much of the offensive content [40]. Therefore, a future direction is to incorporate annotations of communicative intent and specific irony-detection metrics to reduce false negatives and enrich contextual analysis.

Figure 5.

Percentage of Polarity of Emotions in Hate Speech.

Another critical challenge is the scarcity of high-quality, multilingual data. Most work focuses on English-language corpora, which biases and limits the validity of the systems in other languages and dialects [1]. Without balanced repositories that include minority languages and unified annotation schemes for both hate speech categories and emotional nuances, it is tough to compare approaches and ensure cultural equity. As a future solution, it is essential to promote collaborative initiatives that create multilingual repositories with consistent annotations and quality protocols, thereby facilitating reproducibility and benchmarking.

The ambiguity and subtlety of language constitute another barrier. Expressions laden with sarcasm, youth slang, or double entendres (i.e., two interpretations) often fool the most advanced contextual models. Fillies and Paschke [40] demonstrate that even in transformers like BERT, detecting irony and emerging neologisms yields high error rates. To mitigate this, evaluation frameworks are needed that include “youth bias” or “sarcasm detection” metrics, as well as communicative intent annotations that allow algorithms to differentiate between message form and function.

On the technical side, the adoption of deep learning models is hampered by their high computational demands and opacity. Architectures such as those based on multimodal Transformers require substantial volumes of labeled data and computing power, making them challenging to utilize in resource-constrained environments Wang et al. [25]. Furthermore, their “black box” nature prevents auditing and explaining decisions, a critical aspect in sensitive applications. Future directions include model distillation into lightweight versions and the integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques that justify predictions and facilitate adoption in contexts of high social responsibility.

Finally, a multimodal fusion of text, images, emojis, and user metadata will enrich the emotional analysis, as demonstrated by Paul et al. [4], who incorporate cross-attention in Twitter. However, these approaches require synchronized, labeled datasets across modalities, which remain scarce in the literature. Future work should focus on developing multimodal annotation protocols, exploring temporal alignment methods, and investigating how to efficiently combine signals across channels to capture emotional tones more holistically.

Figure 5 presents a visualization that empirically reinforces these findings. The results indicate that the predominant emotional polarity in hate speech is negative (49%), followed by a surprising proportion of positively polarized messages (37.8%) and a minority of neutral messages (13.3%).

The pattern in Figure 5 is consistent with what is expected, given that hate speech is often charged with emotions such as contempt, anger, or rejection. However, the high proportion of messages classified as positive or neutral points to another dimension of the problem. Many hostile messages are crafted to appear benign or employ emotionally positive grammatical structures that conceal harmful content. This is consistent with the argument by Fillies and Paschke [40], who argue that contemporary language, particularly among young people and on social media, includes forms of expression that are difficult to capture by outdated or biased models. The presence of these disguised emotions underscores the need to incorporate emotional detection into automated moderation systems.

Furthermore, the possibility that hate speech may be perceived as emotionally neutral also raises methodological questions. Ramos et al. [1] suggests that emotion should be assessed in conjunction with the full communicative context rather than solely from the plain text. Consequently, the detection of emotional tone in hate speech should consider not only polarity but also its implicit manifestations, temporal evolution, and relationship to the conversational environment. In this sense, the contributions of Wang et al. [25] on multimodal models open the door to a more holistic and nuanced detection, allowing us to understand not only the content but also the intention and emotional impact of messages.

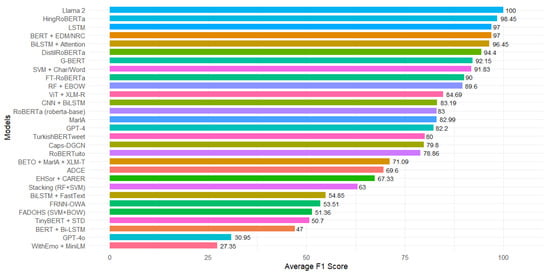

- RQ5: Which NLP or machine learning models perform best in the classification of emotional tone based on metrics such as precision, recall, or the F1 score?

In analyzing the primary studies, researchers used the F1 score, a metric that combines precision and recall, to detect emotional tone in hate speech. This measure provides a balanced evaluation when working with datasets with class imbalance. A value close to 1 (or 100%) indicates that the model correctly identifies and retrieves relevant instances.

It is important to note that the performance values reported in the studies should be interpreted within the specific experimental context of each work. Differences in dataset size, class imbalance, annotation criteria, and evaluation methods make F1 scores not directly comparable across studies. Therefore, the results presented below highlight the models that achieve the best performance within the specific methodological conditions of each investigation and do not constitute an absolute comparison between heterogeneous scenarios.

Based on the F1-score analysis, the LLaMA 2 model achieved 100% performance on this metric, making it the most practical for classifying emotional tone in hate speech. This result was obtained by applying context-based learning to five examples in the Google Play dataset, which has a small number of labeled records and an uneven class distribution.

The LLaMA 2 model operates on a transformer-like architecture that implements RMSNorm normalization, employs the SwiGLU activation function, and utilizes rotational position encoding. It was trained on trillions of tokens and can handle long inputs, facilitating the interpretation of broader contexts. The model does not require weight tuning, as it generates predictions only from examples within the same input message; this enables its application in scenarios with insufficient data for supervised training.

On the other hand, HingRoBERTa, which specializes in Hindi-English code-mixed texts, follows with a 98.45% score [18]. LSTM [28], and BERT combined with EDM/NRC (Emotion Detection Model and NRC Emotion Lexicon) [15], both with a 97% score, reflecting the usefulness of classical models and lexical techniques in specific contexts.

Likewise, other models achieved outstanding results, such as BiLSTM with attention mechanisms, which scored 96.45% Li et al. [7], DistilRoBERTa, which scored 94.4% [36], and G-BERT, which scored 92.15% [19]. These values indicate a preference for Transformer-based models and combinations with emotion-focused attention techniques or embeddings, demonstrating the ability to capture emotional context in language. Figure 6 presents the best-performing models based on their average F1 score, highlighting the effectiveness of modern architecture compared to classical approaches.

Figure 6.

Models identified with the best results with the F1-Score metric for the detection of emotional tone in hate speech.

Suppose we relate these performance results to the temporal information in Table 6. In that case, we observe that most of the best-performing traditional and Transformer-based models (such as LSTM, BERT combined with EDM/NRC, HingRoBERTa, or G-BERT) are reported in studies published between 2021 and 2023, when LLM-based approaches were still not widely used for this task. More recent works (2024 and 2025) increasingly evaluate LLaMA 2 and other LLM-based architectures, often in zero-shot or few-shot configurations, leveraging their ability to generalise from limited labelled data. At the same time, several recent studies still rely on classical classifiers when working with small, highly imbalanced datasets or in scenarios where model transparency and reduced computational cost are key requirements. This confirms that the choice between traditional and advanced models is shaped both by the state of the art at the time of publication and by practical constraints related to data and resources.

4. Discussion

This study analyzes the existing literature on the classification of emotional tone in hate speech, using natural language processing and machine learning techniques. Every aspect was considered, from the methodology to the results obtained. Through a selective search and review of publications available on IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM, Springer, and Wiley, we identified 82 articles initially. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we selected 34 relevant primary studies from these sources.

Firstly, we examine the most frequently used natural language processing techniques. These include tokenization (the most common approach), bag-of-words, emotional processing, BERT, Word2vec, GloVe, FastText, lemmatization, stop-word removal, and attention mechanisms. These techniques facilitate the preparation and transformation of texts to identify patterns that aid in detecting emotional tone in hate speech. We see a growing trend toward approaches that combine traditional processing with context-based deep learning models. This methodological evolution demonstrates that the field is migrating toward more complex models that not only analyze the surface of the text but also incorporate deeper semantic elements.

Regarding machine learning models, we identified a higher frequency of Transformer-based architectures, with BERT being the most widely used, followed by its variant RoBERTa. Traditional models such as SVM, Random Forest, and Naive Bayes, as well as neural network models including CNN, LSTM, and BiLSTM, also appear frequently. The publication years collected for each primary study (see Table 6) show that classical classifiers and shallow neural networks dominate the earliest works in our review window (2020 and 2021), whereas Transformer-based models become prevalent in studies published from 2022 onwards. LLM-based approaches (such as GPT-3, GPT-4, LLaMA 2, Gemini, and Gemma) appear only in the most recent works (2024 and 2025). They are still used in a comparatively small number of studies, usually in zero-shot or few-shot configurations. This pattern suggests that the use of traditional models in many studies is primarily driven by the state of the art and the availability of tools at the time of publication, as well as by the fact that several works operate on relatively small or highly imbalanced datasets, where simpler, more interpretable models remain attractive. At the same time, the strong performance of some less frequently used recent models, such as LLaMA 2, indicates that future research should further explore their robustness, reproducibility, and suitability for real-world deployment.

It is important to note that some of the best-performing models are not the most commonly used in the reviewed studies, demonstrating that frequency of use is not always related to effectiveness. These performance differences must be understood within the specific experimental context of each work, since factors such as dataset size, class imbalance, annotation criteria, and evaluation procedures influence the values reported for metrics such as F1. Therefore, the relative effectiveness of these models reflects their performance under the methodological conditions of their respective studies, rather than a universal comparison across heterogeneous scenarios. Among the models with the highest F1 scores are LlaMA 2 (100%), HingRoBERTa (98.45%), and models such as LSTM and BERT+EDM/NRC (97% each). These results indicate that less-cited models can outperform the most popular ones. This finding highlights the need for future research to be more inclusive of replicating well-known architecture; instead, recent proposals that have demonstrated greater generalization and accuracy should be explored.

Regarding the identified emotions, we align with Ekman’s theory. When comparing negative and positive emotions, the former predominates. Among them, anger, fear, and sadness stand out as the most frequent, which is consistent with the hostile nature of this type of discourse. When discussing positive emotions, we encounter happiness, love, and gratitude, which, although ostensibly positive and non-harmful, can be expressed in ironic or ambiguous ways, adding complexity to the analysis and highlighting the need to improve approaches that capture less explicit semantic nuances. Along these lines, Fillies and Paschke [40] highlights that hostile expressions disguised as positive are increasingly frequent in youth speech, posing a considerable challenge for models that work solely with emotional polarity, leading to a high number of false negatives.

On the other hand, our synthesis reveals that these advances do not eliminate the core obstacles to emotion-aware hate speech detection. Based on the answers to RQ1–RQ5, we group the main challenges into four categories and outline how current research is beginning to address them.

The first challenge is that a considerable portion of hateful content is expressed implicitly, through sarcasm, irony, or ostensibly positive wording. Our own analysis of emotional polarity (Figure 5) shows that almost 40% of messages in hate speech corpora are labelled with positive polarity and 13.3% as neutral, even though they may contain hostile or discriminatory content. This is consistent with studies reporting that youth language increasingly uses positive or playful expressions to convey insults and exclusion [5,40]. Models that rely only on polarity or on surface lexical cues are therefore prone to miss a large portion of abuse. Several works included in this review attempt to mitigate this issue by combining hate speech detection with auxiliary emotion and sentiment tasks [3,15], or by adopting multi-task learning frameworks that jointly model politeness, emotion, and other pragmatic dimensions in dialogues [17]. Our findings suggest that future systems should systematically integrate emotion signals, irony detection, and conversational context, instead of treating hate speech as a purely sentence-level classification problem.

The second challenge is the high linguistic variability of online discourse, including code-mixed texts (e.g., Hinglish, Hindi-English, Khasi), dialectal variants, and youth slang [5,18,19,28,32]. We observe a predominance of English-language corpora and only a limited number of high-quality resources for low-resource languages and mixed-language settings, leading to language and domain biases and limiting generalisation [1]. To address this, some authors rely on subword-based Transformer models adapted to specific languages, language augmentation strategies for code-mixed text [18], or specialised architectures such as HingRoBERTa and G-BERT [19]. However, these efforts remain fragmented. A key implication of our review is the need for multilingual and code-mixed corpora with harmonised annotation schemes for both hate categories and emotions, along with domain-adaptive pre-training and continual learning that explicitly target dialects, emergent slurs, and youth registers.

The third challenge concerns data quality, class imbalance, and annotation complexity. Many of the primary studies work with small or moderately sized datasets, where hateful classes and minority emotion categories are severely under-represented. Emotion labelling is inherently subjective, and the reviewed works adopt different emotion taxonomies and annotation guidelines, which complicates cross-dataset comparison [2]. Some authors try to alleviate data scarcity by resorting to distant supervision, for example, by labelling millions of tweets based on emojis aligned with Ekman’s basic emotions [14], or by combining several corpora in a multi-dataset training setup [3]. These strategies increase coverage but introduce noise and potential label drift. Our results highlight the importance of clearer annotation protocols for hate and emotions (including explicit treatment of sarcasm and implicit abuse), systematic reporting of inter-annotator agreement, and the adoption of techniques to handle imbalance, such as re-sampling, cost-sensitive learning, or focal losses. Active learning and human-in-the-loop pipelines, where annotators focus on the most ambiguous or rare cases, also emerge as promising directions.

The fourth challenge concerns robustness, bias, and the practical deployment of models. Several studies included in this review warn that deep learning and Transformer-based models can inherit and amplify biases present in training data, disproportionately misclassifying the language of specific social groups or dialect communities as hateful [40,41]. At the same time, their “black box” nature makes it difficult to understand why a particular message is flagged, which is problematic in sensitive applications. Recent work begins to address these issues by integrating explainable AI techniques, such as attention visualisation, feature-importance scores, and local explanations, to inspect which cues drive predictions [6,7,36]. From a deployment perspective, Transformer- and LLM-based architectures offer clear performance gains but require substantial computational resources and specialised hardware, which limits their use in low-resource environments and low-latency moderation scenarios [25]. Some authors respond to this limitation by using distilled models (e.g., DistilRoBERTa), model compression, and multimodal architectures that focus only on high-risk content [4,36]. Our synthesis supports the design of cascaded moderation pipelines, where lightweight models filter the majority of content and more complex architectures are reserved for borderline or high-impact cases, as well as further research into model distillation and quantisation that preserve emotional nuance while reducing computational cost.

Finally, we emphasize that the findings of this systematic review offer an insight into the current state of the techniques and models most commonly used for detecting emotional tone in hate speech, which highlights the need to continue improving tools to address the complexity of language in the digital environment to make hate speech safer and more respectful. In this regard, it is recommended that future research advance toward the development of hybrid models that combine supervised approaches with deep semantic interpretation capabilities. Additionally, we suggested cross-validating models in different regions, designing multimodal annotations that incorporate text, emojis, and user context, and integrating systems that not only detect emotions but also interpret the communicative intent behind messages.

5. Conclusions

This study applied a combination of PRISMA and PICOS methodological guides to conduct a systematic literature review, highlighting the importance of natural language processing and machine learning in detecting emotional tones in hate speech. The findings show that among the 34 primary studies analyzed, these techniques enable the identification of emotional patterns targeting vulnerable groups. Among the most widely used are those focused on linguistic preprocessing and semantic embeddings, such as Word2Vec and BERT. We observed a preference for models such as BERT, RoBERTa, SVM, and Random Forest, although some less common ones, such as LLaMA 2, demonstrated superior performance. We also identified a clear predominance of negative emotions such as anger and fear, consistent with the hostile nature of this type of speech, as well as the ironic use of positive emotions, which poses significant semantic challenges. The main limitations of our study include the scarcity of multilingual corpora and the difficulty of interpreting ambiguous expressions, such as sarcasm.

As future work, we plan to develop hybrid models that integrate supervised techniques with deep semantic analysis to achieve more precise, contextualized, and respectful emotional detection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152312686/s1. Reference [45] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.D., R.R., and W.F.; Methodology, A.E.D. and R.R.; Literature search and selection, A.E.D. and R.R.; Validation, A.E.D., R.R. and W.F.; Formal analysis, A.E.D., R.R. and W.F.; Investigation, A.E.D. and R.R.; Data curation, A.E.D. and R.R.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.E.D. and R.R.; Writing—review and editing, W.F.; Visualization, A.E.D. and R.R.; Supervision, W.F.; Project administration, W.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by the Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE through the Research Management Unit, under the budget certification No. 1563, as specified in Memorandum No. ESPE-UGIN-2025-1845-M.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. The data supporting the findings of this systematic review of the literature consist of previously published articles that are publicly available and cited throughout the manuscript. Therefore, no additional data are available.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE for the academic, technical, and institutional support provided for the development of this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, OpenAI ChatGPT (GPT-5, 2025) was used to help with style correction and LaTeX formatting. The authors have reviewed and edited all generated content and assume full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramos, G.; Batista, F.; Ribeiro, R.; Fialho, P.; Moro, S.; Fonseca, A.; Guerra, R.; Carvalho, P.; Marques, C.; Silva, C. A comprehensive review on automatic hate speech detection in the age of the transformer. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2024, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Tang, Q.; Tian, Y. Evaluation of emotion classification schemes in social media text: An annotation-based approach. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Lin, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Lu, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, B. Finding hate speech with auxiliary emotion detection from self-training multi-label learning perspective. Inf. Fusion 2023, 96, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Mallick, S.; Mitra, A.; Roy, A.; Sil, J. Multi-modal Twitter Data Analysis for Identifying Offensive Posts Using a Deep Cross-Attention–based Transformer Framework. Acm Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2025, 19, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, A.; Wahlang, L.; Jyrwa, F.; Shadap, F.; Barbhuiya, F.; Dey, K. Abusive Language Detection in Khasi Social Media Comments. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastrati, M.; Imran, A.S.; Hashmi, E.; Kastrati, Z.; Daudpota, S.M.; Biba, M. Unlocking language barriers: Assessing pre-trained large language models across multilingual tasks and unveiling the black box with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 149, 110136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chan, J.; Peko, G.; Sundaram, D. An explanation framework and method for AI-based text emotion analysis and visualisation. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 178, 114121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, T.F.; Bruun Nielsen, M.F.; Lindhardt, C.L.; Eriksen, M.B. Using the full PICO model as a search tool for systematic reviews resulted in lower recall for some PICO elements. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 127, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, J.I.; Garcés, E.; Fuertes, W. Ransomware Detection with Machine Learning: Techniques, Challenges, and Future Directions—A Systematic Review. J. Internet Serv. Inf. Secur. 2025, 15, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macas, M.; Wu, C.; Fuertes, W. Adversarial examples: A survey of attacks and defenses in deep learning-enabled cybersecurity systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Astudillo, E.; Fuertes, W.; Sanchez-Gordon, S.; Nuñez-Agurto, D.; Rodríguez-Galán, G. A Phishing-Attack-Detection Model Using Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.B. Forming research questions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastrati, M.; Kastrati, Z.; Shariq Imran, A.; Biba, M. Leveraging distant supervision and deep learning for twitter sentiment and emotion classification. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2024, 62, 1045–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashedi, M.; Soon, L.K.; Goh, H.N.; Lim, A.H.L.; Siew, E.G. Cyberbullying Detection Based on Emotion. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 53907–53918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Chen, Y.L.; Argueta, C. FADOHS: Framework for Detection and Integration of Unstructured Data of Hate Speech on Facebook Using Sentiment and Emotion Analysis. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 22400–22419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, P.; Firdaus, M.; Ekbal, A. A multi-task learning framework for politeness and emotion detection in dialogues for mental health counselling and legal aid. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takawane, G.; Phaltankar, A.; Patwardhan, V.; Patil, A.; Joshi, R.; Takalikar, M.S. Language augmentation approach for code-mixed text classification. Nat. Lang Process J. 2023, 5, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keya, A.J.; Kabir, M.M.; Shammey, N.J.; Mridha, M.F.; Islam, M.R.; Watanobe, Y. G-BERT: An Efficient Method for Identifying Hate Speech in Bengali Texts on Social Media. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 79697–79709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufakou, A.; Garciga, J.; Paul, A.; Morelli, J.; Frank, C. Automatically Classifying Emotions Based on Text: A Comparative Exploration of Different Datasets. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 34th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), Macao, China, 31 October–2 November 2022; pp. 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankita; Rani, S.; Bashir, A.K.; Alhudhaif, A.; Koundal, D.; Gunduz, E.S. An efficient CNN-LSTM model for sentiment detection in #BlackLivesMatter. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 193, 116256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, U. Detecting Hate Speech Utilizing Deep Convolutional Network and Transformer Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication and Computers (ELEXCOM), Roorkee, India, 26–27 August 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lou, Y.; Deng, H.; Ji, D. Leveraging bilingual-view parallel translation for code-switched emotion detection with adversarial dual-channel encoder. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 235, 107436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Varol, O. TurkishBERTweet: Fast and reliable large language model for social media analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shibghatullah, A.S.; Iqbal, T.J.; Keoy, K.H. A review of multimodal-based emotion recognition techniques for cyberbullying detection in online social media platforms. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 21923–21956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Gonzalez, N.; Kaltenbrunner, A.; Gómez, V. Uncovering the Limits of Text-based Emotion Detection. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, Virtual, 16–20 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashynska, I.; Sarafanov, M.; Manikaeva, O. Research and Development of a Modern Deep Learning Model for Emotional Analysis Management of Text Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Nawar, F.; Chowdhury, H.A. Sentiment Analysis of Bengali Facebook Data Using Classical and Deep Learning Approaches. In Innovation in Electrical Power Engineering, Communication, and Computing Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de León Languré, A.; Zareei, M. Improving Text Emotion Detection Through Comprehensive Dataset Quality Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 166512–166536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapis, C.M.; Karanikola, A.; Kotsiantis, S. Enhancing sentiment analysis with distributional emotion embeddings. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; García-Díaz, J.A.; Valencia-García, R. Spanish MTLHateCorpus 2023: Multi-task learning for hate speech detection to identify speech type, target, target group and intensity. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2025, 94, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidhar, T.T.; B, P.; P, S.K. Emotion Detection in Hinglish(Hindi+English) Code-Mixed Social Media Text. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, T.; Aiman, A.; Hashmi, E.; Imran, A.S.; Daudpota, S.M.; Yayilgan, S.Y. Hate Speech Detection in Code-Mixed Datasets Using Pretrained Embeddings and Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), Islamabad, Pakistan, 9–10 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallecillo-Rodríguez, M.E.; Plaza-del Arco, F.M.; Montejo-Ráez, A. Combining profile features for offensiveness detection on Spanish social media. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 272, 126705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaeddini, M. Emotion Detection in Reddit: Comparative Study of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.10328. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, A.; Kocoń, J. Integrating personalized and contextual information in fine-grained emotion recognition in text: A multi-source fusion approach with explainability. Inf. Fusion 2025, 118, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touahri, I.; Mazroui, A. Enhancement of a multi-dialectal sentiment analysis system by the detection of the implied sarcastic features. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 227, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecourt, F.; Croitoru, M.; Todorov, K. ‘Only ChatGPT gets me’: An Empirical Analysis of GPT versus other Large Language Models for Emotion Detection in Text. In Proceedings of the WWW ’25: Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Irsan, I.C.; Thung, F.; Lo, D. Revisiting Sentiment Analysis for Software Engineering in the Era of Large Language Models. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillies, J.; Paschke, A. Youth language and emerging slurs: Tackling bias in BERT-based hate speech detection. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 3953–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Díaz, J.A.; Cánovas-García, M.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Valencia-García, R. Detecting misogyny in Spanish tweets. An approach based on linguistics features and word embeddings. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 114, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, O.; Cornelis, C.; Hoste, V. Fuzzy rough nearest neighbour methods for detecting emotions, hate speech and irony. Inf. Sci. 2023, 625, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.O.; Fuertes, W.; Cazares, M.; Ortiz-Garcés, I.; Navas, G. An Exploratory Study of Cognitive Sciences Applied to Cybersecurity. Electronics 2022, 11, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadollahi, A.; Shahraki, A.G.; Zaiane, O.R. Current State of Text Sentiment Analysis from Opinion to Emotion Mining. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2017, 50, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).