Abstract

The angular shape and breakage of particles for calcareous sand significantly influence its mechanical behavior and the safety of the engineering. Although previous studies have explored the impact of particle shape on the mechanical properties of calcareous sand, the effects of shape-induced stiffness anisotropy and particle breakage remain insufficiently investigated. This study employs the Yade open-source 3D discrete element platform to conduct a series of numerical simulations of isotropic compression and simple shear tests on calcareous sand, examining stiffness, deformation characteristics, microscopic behavior, anisotropic properties, and the influence of different particle breakage rates. The results reveal that particle shape-driven stiffness anisotropy in calcareous sand is obvious. The horizontal shear modulus is different from the vertical modulus by up to 15% under confining pressures of 50 kPa to 1200 kPa. Irregularly shaped particles tend to align in a layered fabric under gravitational deposition, resulting in spatial anisotropy in the distribution of contact normals. Strong contact forces concentrate in the direction of gravitational deposition (i.e., the vertical direction), leading to significant anisotropy in shear modulus, with the horizontal shear modulus being notably greater than the vertical one. The values of horizontal shear modulus ranging from 40 MPa for chunky particles to 120 MPa under high confining pressure. While increasing confining pressure generally enhances the shear modulus of calcareous sand, the concentration of strong contact forces in the vertical direction due to particle shape causes differential increments in shear modulus across directions, thereby altering anisotropy. Particle breakage under high confining pressure (10%) disrupts the concentration of strong contact forces in the vertical direction and triggers a “surrounding particle compensation” mechanism (accounting for >95% of cases), leading to homogenization of contact force distribution. This significantly reduces the shear modulus and diminishes the degree of anisotropy by up to 50% at breakage rates of 10%. The cross-scale relationship between particle morphology, breakage, and fabric evolution is quantified.

1. Introduction

Calcareous sand is formed through diverse biological, physical, and chemical processes. It mainly originates from fragmented shells and skeletal remains of marine organisms. It is widely distributed in coral reefs and coastal areas worldwide, such as the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, the western continental shelf of Australia, and the South China Sea []. Compared to siliceous sand, calcareous sand exhibits two distinctive characteristics. First, it is prone to break into smaller particles under relatively low pressure []. This behavior results from the lower hardness of its main component (calcium carbonate) and the presence of numerous micro-pores within and on the surface of the particles [,]. Second, its particles exhibit irregular shapes, such as curved flat particles and hollow tubular particles [,].

Particle shape significantly affects the particle surface roughness, shear strength, stiffness, and compressibility by influencing the density, interparticle locking, particle movement, and structural stability of calcareous sand. Several scholars have investigated the particle shape of calcareous sand. For instance, Hu et al. [] proposed a three-dimensional reconstruction method for calcareous sand particles based on multi-view two-dimensional images. However, the reconstruction accuracy of dendritic particles was slightly lower.

Several studies have further investigated the influence of particle shape on mechanical properties. Wang et al. [] reconstructed the three-dimensional structure of calcareous sand particles and pores using CT scanning technology, and a strong negative correlation was revealed between the fractal dimension of pores and the particle shape coefficient. Li et al. [] experimentally demonstrated the coupled effect of particle shape and internal pore distribution on the mechanical properties of calcareous sand. Li et al. [], based on experimental results, pointed out that as the content of irregularly shaped calcareous sand particles increased, the coefficient of lateral earth pressure at rest exhibited an upward trend. Rui et al. [] quantitatively assessed particle shape and conducted undrained uniaxial and cyclic simple shear tests. Their results revealed the significant influence of particle shape on the liquefaction resistance of calcareous sand. Wu et al. [] performed a series of triaxial compression tests on calcareous sand from the Nansha Islands, and found that the stress–strain curve of calcareous sand was significantly influenced by both density and confining pressure, while the extent of particle breakage increased with the rise in density and confining pressure. Cheng et al. [] employed the discrete element method (DEM) to simulate biaxial shearing on cemented calcareous sand, and found that particle shape, gradation, and particle strength significantly affect the mechanical behavior of cemented calcareous sand. Hu et al. [] systematically studied the effect of particle shape on the dynamic properties of granular soil using DEM and concluded that particles with distinct shapes exhibited higher shear modulus due to fewer collisions. By combining the cohesive contact model with DEM and FEM, the particle breakage was effectively simulated by Liu et al. []. The results showed that the particle breakage significantly reduced the bearing capacity of calcareous sand and decreased volumetric shear dilation. The study by Shi et al. [] investigated the shape anisotropy induced by particle morphology through triaxial experiments equipped with bender elements, and showed that particles with low sphericity exhibited higher stiffness anisotropy. However, the study did not account for the impact of particle breakage on shape anisotropy. These studies mainly focus on the effect of particle shape and the anisotropic properties induced by the particle shape are still limited.

Previous research has highlighted the importance of particle breakage on the mechanical properties of calcareous sand [], including particle size distribution [], packing density [], friction angle [], strength [], permeability, and microstructure []. Current research on particle breakage primarily relies on laboratory and field tests [,,,], which has yielded extensive macroscopic data and provides insights into the phenomenon. Nevertheless, current research methods also face several limitations, such as high costs, data variability, and poor repeatability. Moreover, these studies often overlook the influence of particle shape.

In recent years, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) [] has proven to be a powerful tool for exploring the behavior of crushable granular materials, including shear strength, volumetric expansion, breakage evolution, force chain transmission, and energy distribution. Using various DEM algorithms, researchers have conducted extensive numerical simulations of particle breakage and provided microscopic interpretations of experimental phenomena. These studies have considered multiple factors, such as stress paths (e.g., Wang et al., 2021 []), particle shape (e.g., Ueda et al., 2013 []), and particle size [].

Although extensive research has been conducted on this topic, the anisotropy of stiffness induced by particle shape and its underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood for calcareous sand. In this study, based on the Yade open-source 3D DEM platform [], a series of triaxial numerical simulations is conducted to investigate the effects of different particle breakage rates on the stiffness, deformation characteristics, microscopic behavior, and anisotropy of calcareous sands with varying particle shapes. This study aims to quantify the stiffness anisotropy of calcareous sand through numerical simulations, and elucidate the effects of particle breakage on anisotropy.

2. Details of Numerical Simulation

2.1. Initial Parameters and Procedure

In this study, the small-strain shear modulus () is employed to characterize the stiffness properties of calcareous sand in different directions across various stress stages. To facilitate the acquisition of in multiple directions, a cubic numerical model with dimensions of 10 × 10 × 10 mm was established based on DEM. The particle radii ranged from 0.24 to 0.48 mm, with a uniform particle size distribution, and the interparticle contact relationships were modeled using the Hertz-Mindlin nonlinear contact model. Specific parameter values are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primary parameter values in numerical simulations.

During the simulation, isotropic confining pressures of 50 kPa, 100 kPa, 200 kPa, 400 kPa, 800 kPa, and 1200 kPa were applied to avoid stress-induced anisotropy. Given the variability in the actual strength of different calcareous sand particles, and to validate the universality of the particle breakage algorithm for calcareous sand particles of varying strengths, the particle strength was not directly referenced to a specific type of calcareous sand. Instead, four common levels of particle breakage were defined based on the particle breakage rate at 800 kPa: no breakage (0%), low breakage (1%), mid breakage (5%), and high breakage (10%). This approach allowed for the investigation of the macro- and micro-scale characteristics of calcareous sand under identical conditions, solely influenced by varying degrees of particle breakage. All simulations were repeated at least three times under identical conditions to ensure reproducibility. The results showed that the variation in shear modulus values was less than 1% across repetitions, indicating high consistency.

2.2. Particle Shape

To simulate the various shapes of calcareous sand particles, three representative shapes were selected based on previous morphological studies [] of calcareous sand particles: chunky, stripy, and dendritic. The specific shapes are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected representative shapes of calcareous sand particles.

2.3. Algorithm for Particle Breakage

Previous studies on particle breakage simulation using DEM can generally be divided into two approaches. The first is the “Parallel Bond” method. In this approach, all particles are generated during sample preparation. Some particles are connected using the Parallel Bond Model to form aggregates. The aggregates are then linked through elastic models. For instance, Jin et al., 2025 [], proposed an improved coarse-graining method for strongly cemented systems. Their method derived scaling relationships for microscopic parameters including elastic strain energy, damping dissipation energy, and rolling friction energy. This approach significantly improved computational efficiency (up to 83 times) while accurately reproducing the mechanical behavior and failure characteristics of the original system. However, even with improved computational efficiency, extensive contact detection among numerous particles within aggregates remains time-consuming.

The second method, called “particle replacement,” avoids this issue more effectively. In this approach, each particle represents an individual grain during sample preparation. During simulation, particles meeting predefined breakage criteria are replaced according to specific replacement rules. Considering both simulation accuracy and computational efficiency, this study adopts the second approach. Specifically, the numerical simulation employs a post-replacement method to simulate calcareous sand particle breakage. When interparticle contact forces meet specific strength criteria, particles are considered broken. Subsequently, original particles are replaced by new ones following predetermined replacement criteria. The strength criterion adopted in this study to determine particle breakage is the Gladkyy-modified Mohr-Coulomb-Weibull combined strength criterion [], which utilizes the Mohr-Coulomb law with tensile and compressive cutoffs and considers the influence of particle size on single-particle strength. The relationship between particle strength and particle size conforms to the Weibull distribution.

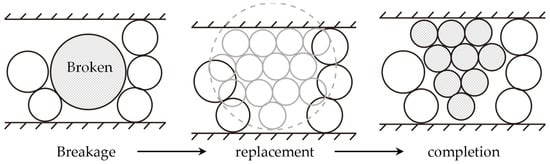

The particle replacement criterion is derived from Brzeziński’s algorithm [], with specific modifications illustrated in Figure 1. When a particle fractures according to the failure criterion, nine smaller particles with equal radius are used for replacement, balancing computational efficiency and accuracy. To ensure mass conservation, the replacement process involves expanding the filling area into the surrounding region. If the surrounding space is insufficient for successful replacement, the process is abandoned. This study optimizes the behavior during replacement failure based on laboratory experiments by introducing a “delayed failure” mechanism [], simulating the phenomenon of “fracture without fragmentation” due to spatial constraints: when space is insufficient, the particle is assumed to have already fractured (a). But the fractured particles are densely packed without affecting neighboring particles, maintaining their original shape without replacement. When sufficient space becomes available later (b), the fractured particles are released, influencing the surrounding particles (c). At this point, regardless of whether the failure conditions are still met, particle replacement is performed.

Figure 1.

Particle fragmentation pattern. (adapted from []).

2.4. Algorithm for Small-Strain Shear Modulus

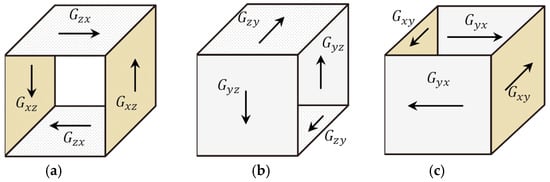

The small-strain shear moduli on three orthogonal directions labeled as , and obtained by simple shearing are used to characterize the stiffness anisotropy of calcareous sand, as illustrated in Figure 2, where x, y, and z represent three mutually perpendicular directions. According to previous research [,,,,], during the elastic phase, the small-strain shear modulus is solely dependent on the stress within the respective plane. For instance, is influenced only by and , and is independent of .

Figure 2.

Shear moduli for small strains in different orientations: (a) shear mode 1, (b) shear mode 2, and (c) shear mode 3.

2.5. Characterization of Microscopic Anisotropy

To measure how anisotropic the contact normals are in a granular system, we can use a fabric tensor. This method was proposed in earlier work []. The tensor is built by analyzing the statistical distribution of contact normal vectors:

where represents the unit normal vector of the contact, and denotes the number of inter-particle contacts. The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the fabric tensor can reflect the degree of anisotropy concentration and the principal direction of the contact normal orientations. Consequently, the anisotropy concentration coefficient is defined as:

where (for ) are the three eigenvalues of the fabric tensor. Additionally, the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue is selected as the dominant principal direction of anisotropy.

3. Stiffness Anisotropy of Calcareous Sands with Different Particle Shapes During Isotropic Stress Compression

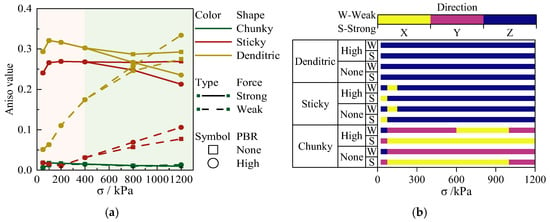

3.1. The Variation in Small-Strain Shear Modulus with Isotropic Stress

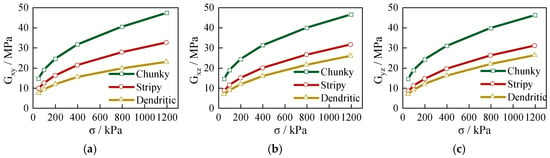

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between the small-strain shear modulus and confining pressure for calcareous sands with different particle shapes under conditions with no particle breakage. Overall, for all particle shapes, and are consistently similar across various conditions, whereas differs significantly, being higher than and . Particle shape exerts a pronounced influence on both the initial magnitude of the shear modulus and its increasing rate with confining pressure. The shear modulus rises significantly as the confining pressure increases. Among the three particle shapes tested, chunky particles exhibit the highest shear modulus and the fastest rate of increase. Stripy particles show intermediate values for both modulus and its rate of increase. In contrast, dendritic particles have the lowest shear modulus and the smallest rate of increase. For example, at 1200 kPa, the shear modulus of chunky particles is approximately three times that at 50 kPa, whereas the shear modulus of dendritic particles is only about twice that at 50 kPa. Notably, chunky particles consistently demonstrate the highest modulus across all stress levels.

Figure 3.

The relationship between shear modulus for calcareous sands with different shapes and the confining pressure with no particle breakage: (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

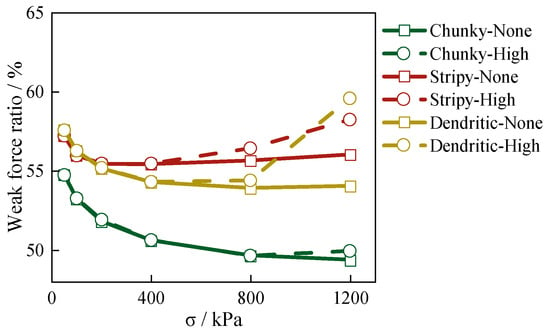

3.2. Anisotropy of the Small-Strain Shear Modulus

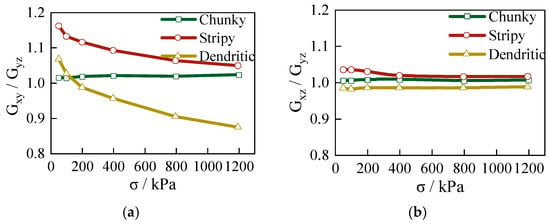

To intuitively characterize the anisotropy of the shear modulus in calcareous sand, the ratios of and were employed. As illustrated in Figure 4, the relationship between the shear modulus ratio and confining pressure for particles with different shapes without particle breakage is presented. It is evident that at low confining pressures, for irregularly shaped calcareous sand particles (i.e., stripy and dendritic particles) is significantly greater than 1 (~1.15 at 50 kPa), while remains consistent and close to 1 across all confining pressures. This indicates that the anisotropy of calcareous sand, induced by particle shape, is primarily manifested in the difference between the vertical and horizontal directions. Specifically, the horizontal shear modulus is notably larger than the vertical one. At lower confining pressures (50 kPa or 100 kPa), the ratio is highest for stripy particles, followed by dendritic particles, and lowest for chunky particles (exhibiting no anisotropy, ~1). As the confining pressure increases, the ratio decreases, and for dendritic particles of calcareous sand, it reduces to less than 1 (~0.9). This suggests that with increasing confining pressure, the vertical shear modulus of dendritic calcareous sand gradually surpasses the horizontal one, demonstrating significant sensitivity to confining pressure. Since , the subsequent discussion will focus on and as representative parameters.

Figure 4.

The relationship between the shear modulus ratio of calcareous sands with different shapes and the confining pressure with no particle breakage: (a) ; (b) .

3.3. The Impact of Particle Breakage on the Anisotropy of Small-Strain Shear Modulus

Particle breakage is a significant characteristic of calcareous sand. This study investigates four representative levels of particle breakage. In laboratory studies of calcareous sand, the breakage model proposed by Hardin and the relative breakage index [] are commonly used as indicators of particle breakage. However, only indirectly reflects the degree of particle breakage and does not directly represent the particle breakage rate (PBR). Therefore, this study introduces PBR as the indicator of particle breakage, calculated as the number of broken particles divided by the total number of particles in the sample. It is impractical to directly specify the particle breakage ratio (PBR) at the macroscopic level. This is because the breakage criterion for individual particles depends on their intrinsic strength, not the PBR. In this study, we use PBR values of 0%, 1%, 5%, and 10% at 800 kPa confinement to represent different breakage levels. These levels correspond to none, low, medium, and high breakage, denoted as None, Low, Mid, and High, respectively. The actual breakage rates for different particle shapes, as shown in Table 3, exhibit relative distinctions of no more than 3% compared to the preset breakage rates, confirming that the actual breakage rates align with the preset values.

Table 3.

The actual particle breakage rate corresponding to different particle shapes and the generated particle breakage rate (PBR).

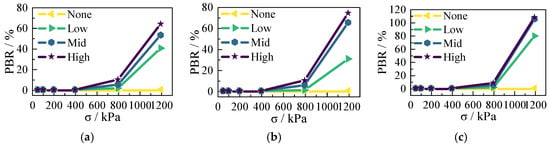

As the confining pressure increases, the degree of particle breakage in calcareous sand varies depending on the particle shape, as illustrated in Figure 5. Under low confining pressures (<400 kPa), particle breakage is negligible, and its impact can be disregarded. However, under high confining pressures, particle breakage becomes significant. Based on the breakage rates of particles with different shapes, 800 kPa and 1200 kPa were selected as representative conditions for “moderate breakage” and “extreme breakage”, respectively. These pressures were used to investigate the influence of particle breakage on the anisotropy of small-strain shear modulus.

Figure 5.

The relationship between particle breakage rate for calcareous sands with different shapes and confining pressure: (a) chunky; (b) stripy; (c) dendritic.

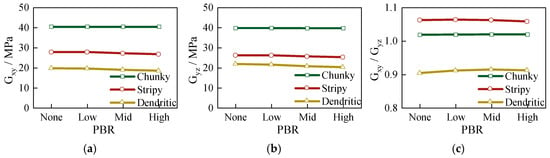

Figure 6 illustrates the variation in shear moduli of calcareous sands with different particle shapes under a confining pressure of 800 kPa as a function of the degree of particle breakage. As shown in Figure 6a,b, the shear moduli of calcareous sands with varying shapes exhibit significant differences as the degree of particle breakage increases from “None” to “High”. Chunky calcareous sand consistently maintains higher shear modulus values, approximately 40 MPa, for both and , whereas stripy-shaped and dendritic calcareous sands exhibit relatively lower shear stiffness. The shear modulus decreases slightly with increasing particle breakage. Figure 6c demonstrates that the anisotropy of the shear modulus in irregularly shaped calcareous sands decreases marginally with increasing particle breakage, though the overall reduction is not substantial.

Figure 6.

The relationship between shear moduli for calcareous sands with different particle breakage rates and shapes under moderate particle breakage: (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

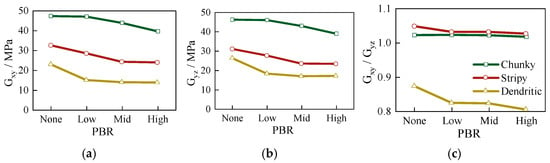

Under a confining pressure of 1200 kPa, the degree of particle breakage in calcareous sand significantly increased. Figure 7 illustrates the impact of the degree of particle breakage on the anisotropy of the shear modulus in calcareous sand. As the degree of particle breakage increases, both the shear modulus and the degree of anisotropy in calcareous sand decrease markedly. For example, Stripy particles exhibit a shear strength reduction from 32 kPa (no breakage) to 25 kPa (high breakage), achieving only 78% of the original strength. Significant particle breakage even eliminates the anisotropy induced by the shape of stripy calcareous sand. As a result, the ratio decreases from approximately 1.05 to nearly 1. Furthermore, the ratio for dendritic calcareous sand decreases further, indicating that the shear modulus in the vertical direction is significantly greater than that in the horizontal direction. This shift results in a change in the dominant direction of the shear modulus, rotating by 90°. These findings demonstrate that particle breakage has a significant influence on the shear modulus and anisotropy of calcareous sand. In the following analysis, the underlying mechanisms are examined by comparing cases with no particle breakage and high particle breakage.

Figure 7.

The relationship between shear moduli for calcareous sands with different particle breakage rates and shapes under extreme particle breakage: (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

4. The Intrinsic Mechanism of Stiffness Anisotropy Induced by the Particle Shape for Calcareous Sand

4.1. The Influence of Particle Shapes on the Coordination Number

The coordination number, defined as the average number of contacts per particle, serves as an indicator of the microscopic compaction degree of a specimen. According to Thornton [], in scenarios where suspended particles may exist, the mechanical coordination number, , should be employed and calculated by the following formula,

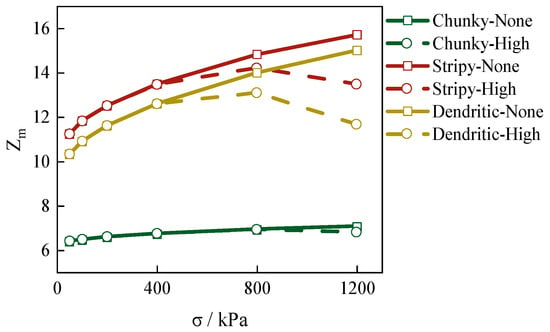

where represents the total number of contacts, is the total number of particles, and and denote the number of particles with zero and one contact, respectively. Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between the coordination number and confining pressure for calcareous sands with different shapes under conditions of high and no particle breakage. As the confining pressure increases, the coordination number of calcareous sands with no particle breakage exhibits an upward trend. For instance, the coordination number of branching calcareous sand rises from 11 at 50 kPa to 15 at 1200 kPa. This indicates a positive correlation between the coordination number and confining pressure. Notably, the coordination numbers of stripy and dendritic calcareous sands are significantly higher than those of chunky sands. Combined with previous findings, it is evident that for a given particle shape, a higher coordination number corresponds to greater shear stiffness in calcareous sands. However, for different particle shapes, particularly between chunky and stripy/dendritic sands, the relationship between coordination number and stiffness is less pronounced. This is attributed to the influence of particle shape and orientation, where a small number of strong interactions in chunky particles are replaced by a larger number of weak interactions in other shapes, making direct comparisons of shear stiffness based on coordination number unreliable. In the low confining pressure range (), particle breakage is negligible, and the coordination numbers under varying breakage rates are nearly identical. Under high confining pressures, particle breakage becomes significant. This breakage decreases the coordination number of calcareous sands. As a result, both contact density and shear modulus are reduced. For example, in stripy calcareous sands, the coordination number drops to 13 under high particle breakage. This value is only 86% of the coordination number observed with no particle breakage.

Figure 8.

The relationship between the coordination numbers of calcareous sands and the confining pressure under conditions of “High” and “None” particle breakage.

4.2. The Internal Anisotropic Characteristics of Calcareous Sand Induced by Particle Shapes

Based on the macroscopic-scale results, the influence of particle breakage on stiffness anisotropy induced by shape is primarily observed at 800 kPa and 1200 kPa. Moreover, the extent of this influence is directly proportional to the particle breakage rate. Therefore, a statistical comparison of microscopic information (mainly focus on contact forces) was conducted under 1200 kPa, focusing on scenarios with “High” and “None” particle breakage.

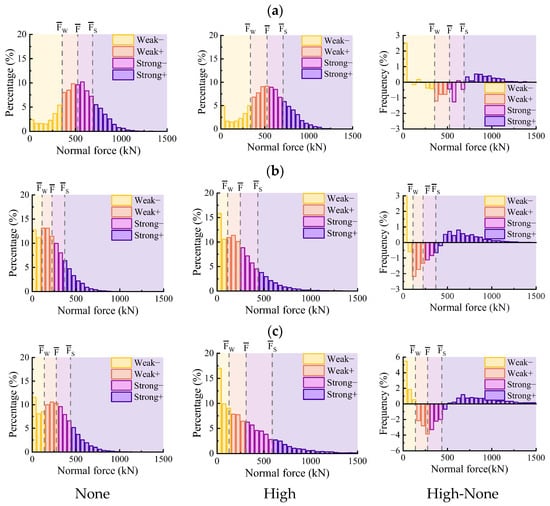

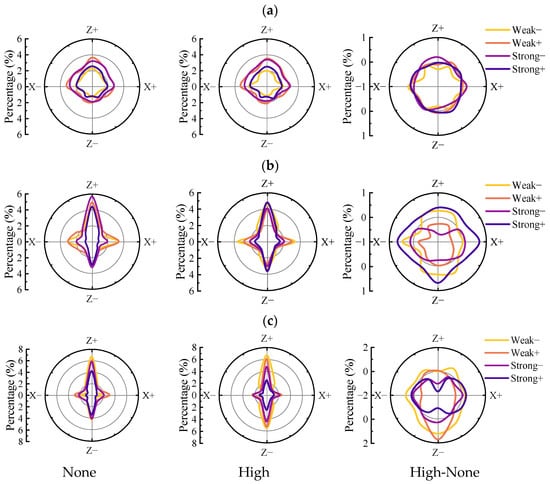

4.2.1. Magnitude of Contact Force

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of normal contact forces for calcareous sands with different particle shapes under different confining pressures and particle breakage rates. Based on the definition proposed by Radjai et al. [], contact forces greater than the average value are classified as strong contact forces, while those below the average are categorized as weak contact forces. In this study, in accordance with the characteristics of contact forces observed in numerical simulations, the figure distinguishes four types of contact forces using different colors: weak− (yellow), representing the weaker portion of weak normal contact forces, which is lower than the mean of weak contact forces; weak+ (orange), representing the stronger portion of weak normal contact forces; strong− (purple), representing the weaker portion of strong normal contact forces, which is lower than the mean of strong contact forces; and strong+ (dark purple), representing the stronger portion of strong normal contact forces. Additionally, the figure includes three dashed lines corresponding to , and , where is the mean of weak contact forces and separates weak− and weak+, is the mean of all contact forces and separates weak+ and strong−, and is the mean of strong contact forces and separates strong− and strong+.

Figure 9.

The distributions and variations in normal contact forces of calcareous sands for: (a) chunky particle; (b) stripy particle; and (c) dendritic particle.

As illustrated in Figure 10, under the confining pressure of 1200 kPa without particle breakage, the contact force distribution of chunky calcareous sand follows a normal distribution, with forces clustering around the mean. In contrast, the contact force distributions of stripy and dendritic calcareous sands exhibit a left-skewed pattern, with a significant increase in the proportion of smaller contact forces. This indicates that particle shape significantly influences the overall distribution of contact forces in calcareous sand. Particle breakage further affects the distribution of contact forces. Under high particle breakage, particularly for stripy and dendritic calcareous sands, the distribution pattern shifts from left-skewed to exponential form. In the weak− and strong+ contact force ranges, the overall frequency increases substantially, while frequencies in other ranges decrease significantly, resulting in a V-shaped curve. Specifically, particle breakage increases the number of both higher and smaller contact forces while reducing the number of forces near the mean.

Figure 10.

The proportion of weak contact forces with confining pressure for calcareous sand specimens with high and no particle breakage.

The proportion of weak forces within a sample significantly influences its deformation, with a higher proportion leading to greater deformation and reduced stiffness. Particle breakage alters the distribution of contact forces within the sample, thereby affecting the proportion of weak forces and, consequently, the macroscopic stiffness. Figure 10 illustrates the relationship between the proportion of weak forces and confining pressure for calcareous sands with different shapes under varying particle breakage rates. Generally, as confining pressure increases, the proportion of weak contact forces within calcareous sands decreases in the absence of particle breakage, resulting in an increase in shear modulus. Chunky calcareous sands exhibit a lower proportion of weak force chains compared to stripy and dendritic calcareous sands, leading to a higher shear modulus under the same confining pressure. The particle breakage rate also affects the proportion of weak forces, with higher breakage rates corresponding to a higher proportion of weak contact forces. This suggests that particle breakage reduces the effective contact points between particles, thereby weakening stress transmission. Additionally, new contacts formed after particle breakage typically exhibit smaller contact forces.

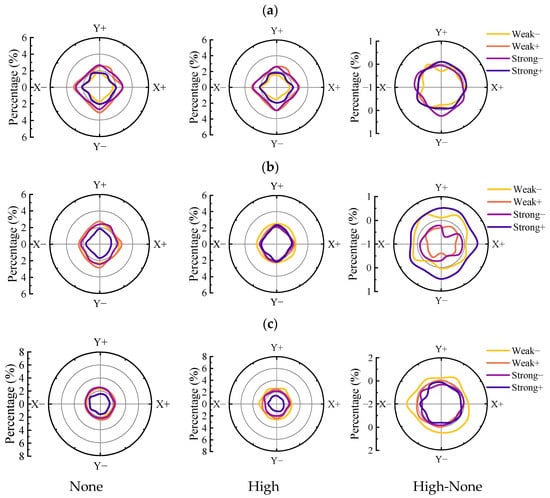

4.2.2. Direction of Contact Force

The magnitude of interparticle contact forces influences the shear modulus. This section investigates the impact of the direction of contact forces on the anisotropy of the shear modulus, with contact normal (i.e., the normal direction of interparticle contact) used to characterize the direction of contact forces. Figure 11 illustrates the distribution of the contact normal in XY plane for calcareous sands with different particle shapes under varying particle breakage rates. In the figure, the closer the line is to the edge, the greater the number of contacts in that direction. In the difference plot, the further the line is from the zero scale (i.e., the closer it is to the outer edge or the center of the circle), the more significant particle breakage affects the contacts in that direction. Specifically, proximity to the outer edge indicates an increase in contact proportion, while proximity to the center indicates a decrease.

Figure 11.

The distribution and difference in contact normal in XY plane for calcareous sands with different particle shapes under varying particle breakage rates for: (a) chunky particle; (b) stripy particle; and (c) dendritic particle.

As shown in Figure 11, the distribution of contact normal in XY plane is consistent for calcareous sands with different particle shapes, exhibiting a circular pattern. This suggests that the contact forces are uniformly distributed in XY plane. Additionally, particle breakage does not introduce a dominant direction in the variation in contact orientation. Instead, the variation agrees with that in Figure 11. That is, contacts corresponding to weak− and strong+ increase, while those corresponding to weak+ and strong− decrease. This indicates that as the particle breakage rate increases, the distribution of contact force undergoes uniform changes across all directions, thereby reducing the degree of anisotropy induced by particle shape.

The contact normal in XZ plane differs from that in XY plane, as illustrated in Figure 12. In XZ plane, the contact distribution for chunky calcareous sands still exhibits minimal variability, displaying a circular pattern. This indicates that the interparticle contacts in XZ plane are uniformly distributed, and the differences caused by particle breakage are also isotropic, consistent with XY plane. Consequently, the macroscopic characteristics of chunky calcareous sand are characterized as isotropic.

Figure 12.

The distribution and difference in contact normal in XZ plane for calcareous sands with different particle shapes under varying particle breakage rates for: (a) chunky particle; (b) stripy particle; and (c) dendritic particle.

In contrast, for stripy and dendritic calcareous sands, the weak contact force directions (weak− and weak+) in XZ plane are concentrated along X and Z axes, while dispersing in other directions, forming a four-pointed star distribution. The strong contact force directions (strong− and strong+) of stripy and dendritic calcareous sand in XZ plane are predominantly concentrated along Z-axis, exhibiting a spindle-shaped distribution. This results in greater shear constraints in XY plane from Z-direction, leading to and manifesting anisotropy. The influence of particle breakage also demonstrates significant anisotropy, with the weak contact force directions (weak− and weak+) showing pronounced changes along Z-axis, forming a spindle-shaped distribution. Specifically, weak− contacts increase while weak+ contacts decrease. The strong contact forces (strong− and strong+) in XZ plane exhibit a concentrated decay along Z-axis. This suggests that the impact of particle breakage on the micro-contact force directions in calcareous sand is primarily concentrated along Z-axis, weakening the strong contact forces and increasing the weak contact forces in this direction, thereby reducing the degree of anisotropy.

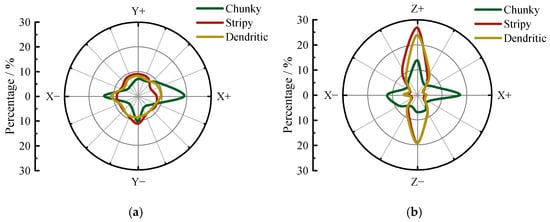

According to previous studies [], when calcareous sand particles undergo breakage, multiple failure surfaces may occur. However, these failure surfaces are closely aligned with the direction of the maximum contact force, allowing the direction of the maximum contact force to approximate the particle breakage direction. Figure 13 shows the distribution of particle breakage orientations for calcareous sands with different particle shapes under a confinement of 1200 kPa for high degree of particle breakage. It is evident that chunky calcareous sand particles exhibit no significant preferential direction of fragmentation across different planes, with only variations in the number of failures. This suggests that the contact force-induced failure of chunky calcareous sand particles does not exhibit a dominant spatial orientation. In contrast, for stripy and dendritic calcareous sand particles, the particle breakage tends to concentrate in Z-direction within XZ plane, displaying a spindle-shaped distribution. In XY plane, however, the breakage counts are relatively uniform. This indicates that the contact force-induced failure of irregularly shaped calcareous sand particles primarily occurs along Z-direction, which enhances the reduction in the strong contacts in Z-direction and further reduces the stiffness anisotropy.

Figure 13.

The distribution of particle breakage directions in calcareous sands with different particle shapes: (a) in XY plane; and (b) in XZ plane.

Figure 14 illustrates the anisotropy degree of contact normal and the related principal direction for both strong and weak contact forces in calcareous sands with different particle shapes under varying particle breakage rates and stress levels. The results reflect the concentration degree and direction of contact forces, with the specific calculation method detailed in Equation (2). As shown in the figure, for chunky calcareous sands, the anisotropy degree of all contact networks is minimal, nearly zero, and remains relatively unchanged with increasing pressure. This indicates that the anisotropy degree is largely unaffected by pressure variations, and the influence of contact normal anisotropy is negligible. Consequently, the principal direction of anisotropy for chunky calcareous sands lacks significant meaning. Hence, the stiffness of chunky calcareous sands is isotropic.

Figure 14.

The degree of anisotropy in the contact normal for calcareous sands with different shapes and the related principal orientation: (a) the degree of anisotropy; and (b) the principal orientation.

In contrast, for stripy and dendritic calcareous sands, the anisotropy degree of contact normal generally increases within the low-stress range (approximately 0–400 kPa) but decreases in the high-stress range, while the anisotropy degree of weak contact forces increases. Notably, for dendritic calcareous sands, the anisotropy degree of weak contact forces surpasses that of strong contact forces. Additionally, as particle breakage increases, the concentration degree of strong contact forces tends to decline, whereas that of weak contact forces rises, indicating that particle breakage reduces the concentration of strong contact forces while enhancing that of weak contact forces. The decrease in anisotropy in contact normal can reduce the anisotropy in macro stiffness.

Except for chunky calcareous sands, which exhibit no dominant direction, the principal directions of both strong and weak contact forces for stripy and dendritic calcareous sands are aligned along Z-axis, demonstrating a clear dominance. Furthermore, as stress increases, the distribution of the fabric tensor remains stable, showing no significant changes, which suggests that particle breakage does not alter the dominant concentration direction of contact normal.

5. Discussion

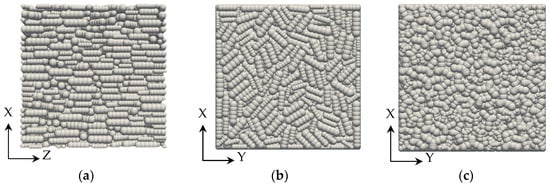

5.1. Factors Influencing the Anisotropy of Calcareous Sand

5.1.1. Particle Shape

The particle shape of calcareous sand is the fundamental cause of its anisotropy of macro properties, such as shear modulus. Through isotropic compression tests on chunky calcareous sand, it was observed that due to its relatively uniform shape, minimal anisotropy of stiffness is induced under isotropic confining pressure, with the small-strain shear modulus primarily governed by confining pressure and particle breakage. In contrast, stripy and dendritic calcareous sands exhibit pronounced stiffness anisotropy. In the microscopic point of view, the macroscopic anisotropy arises from the directional alignment of irregularly shaped calcareous sand particles under gravitational deposition, resulting in a layered distribution along the gravitational direction (as illustrated in Figure 15a for stripy calcareous sand as an example). Under low confining pressure, the smaller interparticle contact forces allow calcareous sand to undergo horizontal displacement much easier along the bedding planes, leading to lower shear moduli of and . Conversely, in the gravitational (vertical) direction, the interlocking effect of particle shapes (as shown in Figure 15b,c) enhances interparticle shear stiffness. This discrepancy in horizontal and the gravitational deposition direction results in macroscopic anisotropy (e.g., ).

Figure 15.

Different cross-sections of calcareous sand samples: (a) XZ cross-section of stripy calcareous sand; (b) XY cross-section of stripy calcareous sand; and (c) XY cross-section of dendritic calcareous sand.

5.1.2. Confining Pressure

The shear modulus of calcareous sand generally increases with confining pressure, but the anisotropic behavior varies depending on the particle shape. Chunky calcareous sand, characterized by less pronounced shape features, exhibits a significant increase in shear modulus under higher confining pressure, with minimal impact on anisotropy. In contrast, stripy and dendritic calcareous sands show a smaller increase in shear modulus along the horizontal direction compared to other directions, leading to a gradual reduction in anisotropy at small strains. Notably, for dendritic calcareous sand, which initially exhibits relatively low anisotropy, a polarity reversal of anisotropy may occur when the confining pressure exceeds 200 kPa, causing the originally dominant direction to become subordinate.

From a microscopic perspective, the influence of confining pressure to the stiffness anisotropy of calcareous sand is attributed to the formation of a layered structure under gravitational deposition as the pressure increases. This results in a concentration of strong contact forces along the gravitational direction. Since the shear stiffness of calcareous sand is primarily governed by these strong contact forces [], the vertical shear stiffness is significantly enhanced. Conversely, the shear stiffness around the vertical direction, which is mainly provided by the interlocking effect of particle shapes, exhibits a less increase. Consequently, macroscopic anisotropy diminishes, and the shear stiffness around the horizontal direction may transition from being dominant to subordinate.

5.1.3. Particle Breakage

Particle breakage significantly influences the shear modulus and anisotropy of calcareous sand. Under low confining pressures, the rate of particle breakage is minimal, resulting in negligible effects on the shear modulus and anisotropy. However, under high confining pressures, the rate of particle breakage increases substantially, leading to an overall reduction in the shear modulus and a decrease in anisotropy. For chunky calcareous sand, which lacks distinct particle shapes, particle breakage primarily reduces the shear modulus. In contrast, for stripy and dendritic calcareous sand, particle breakage not only diminishes the overall stiffness but also reduces the degree of anisotropy in the stiffness.

At the microscopic level, particle breakage reduces shear stiffness by disrupting the strong contact forces within calcareous sand and altering the shape characteristics of the particles. The stiffness primarily relies on strong contact forces, which exhibit spatial anisotropy. Consequently, the disruption of strong contact forces due to particle breakage is concentrated in the direction of gravitational deposition, thereby reducing the shear stiffness in the horizontal direction. Additionally, the destruction of particle shapes reduces the particle interlocking and further diminishes the horizontal shear stiffness. However, since the horizontal shear stiffness is mainly provided by strong contact forces aligned with the gravitational direction, the impact of changes in particle shape characteristics on stiffness is relatively minor. In the horizontal direction, shear stiffness is primarily provided by the interlocking effect resulting from particle shapes; therefore, the destruction of particle shapes due to breakage is the primary cause of stiffness reduction. The reduction in shear stiffness involved in the horizontal direction is greater than that in the vertical direction, which in turn reduces the macroscopic anisotropy of calcareous sand.

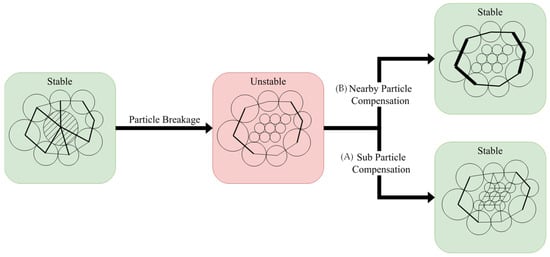

5.2. Increased Contact Forces Within the Strong + Range

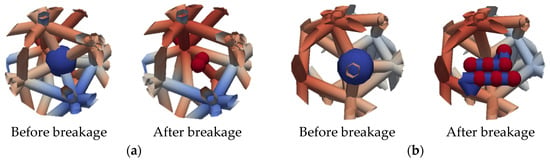

According to previous studies [,], particle breakage primarily disrupts strong contact forces acting along particles, leading to a reduction in the dominant portion of strong contact forces within the contact system, referred to as the strong+ component in the study. However, in this study, an increase in strong+ contact forces was observed after particle breakage. This phenomenon is attributed to stress redistribution induced by particle breakage. Following particle breakage, the originally stable contact system becomes unstable as particles bearing strong contact forces are disrupted, necessitating stress redistribution to compensate for the lost contact forces (the unbalance forces). Previous research [] suggests that sub-particles generated from breakage form multiple weak contacts with surrounding particles, which is the compensation mechanism termed “sub-particle compensation”. However, this mechanism requires sub-particles to establish contact with neighboring particles. In this study, under isotropic confining pressure with relatively small strain, smaller particles resulting from breakage preferentially displace to fill voids that larger particles cannot occupy, rather than bearing the disrupted contact forces. Consequently, when the strain is insufficient for sub-particles to re-establish contact, the surrounding contact forces increase, transitioning from the weak+ and strong− ranges to the strong+ range to compensate for the lost contact forces. This results in an increase in the proportion of strong+ contact forces, which follows another compensation mechanism referred to as “surrounding particle compensation”.

Schematic diagrams of these two stress compensation mechanisms are presented in Figure 16. In this study, both mechanisms occurred simultaneously after particle breakage, with surrounding particle compensation being predominant. If the criterion for distinguishing between the two mechanisms is whether newly generated particles establish contact with surrounding particles, then surrounding particle compensation accounted for over 95% of the cases in this study. Consequently, the overall system exhibited an increase in strong+ contact forces and a decrease in strong− and weak+ forces. Figure 17 provides examples of the two compensation mechanisms, where blue particles represent the original parent particles before breakage, and red particles represent the resulting sub-particles after breakage. As shown in Figure 17a, during surrounding particle compensation, the contact forces acting on surrounding particles significantly increased (indicated by the reddening of colors), while no new contacts were observed between red sub-particles. In contrast, Figure 17b illustrates that during sub-particle compensation, newly generated particles compensated for the lost contact forces (evidenced by numerous blue new contacts between sub-particles and surrounding particles), with minimal increase in contact forces on surrounding particles. The surrounding particle compensation mechanism also explains the phenomenon observed in Figure 17, where the coordination number decreased below that of low confining pressure conditions after particle breakage under high confining pressure, yet the overall stiffness of the specimen increased, as shown in Figure 17. This is attributed to the overall reduction in the number of contacts following particle breakage. A similar mechanical behavior was observed in studies on gangue backfill materials (Wu et al. []). During axial loading, cracks mainly develop near the “force chain skeleton.” The contact forces around this skeleton are the first to fail. This failure leads to the breakage of gangue particles, the rearrangement of particle positions, and greater subsidence that fills the pores. This mechanical behavior is consistent with the “surrounding particle compensation” mechanism proposed in this study. It confirms that such behavior exists not only in the calcareous sand studied here but may also occur in other particle breakage systems.

Figure 16.

Two modes of contact force compensation following particle breakage. (A) “Sub-particle compensation” mechanism: The newly formed sub-particles establish new contacts with surrounding particles to compensate for force loss. (B) “Surrounding particle compensation” mechanism: The sub-particles fail to form new contacts after breakage, while the contact forces of surrounding particles significantly increase.

Figure 17.

Evidence of two contact force compensation modes during particle breakage: (a) the “surrounding particle compensation” mode and (b) the “sub-particle compensation” mode.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the stiffness anisotropy of calcareous sand induced by particle shape and the underlying mechanisms, addressing the gap in understanding how particle morphology and breakage influence mechanical behavior. The characteristics and the micro mechanisms of stiffness anisotropy in calcareous sand induced by particle shape are investigated in this study based on DEM simulations. The effects of particle breakage are also considered. Unlike previous studies, this research provides a comprehensive quantitative analysis of stiffness anisotropy and its micro-mechanisms. The main findings are as follows.

- The irregular particle shape is the fundamental cause of stiffness anisotropy in calcareous sand under isotropic compression. Under gravitational deposition, stripy and dendritic calcareous sand particles exhibit directional alignment, resulting in significant spatial anisotropy in the distribution of interparticle contact normal. This leads to pronounced anisotropy in shear modulus, with the horizontal shear modulus being greater than the vertical shear modulus. The contact directions of stripy and dendritic particles exhibit a spindle-shaped distribution, with strong contact forces concentrated in the vertical direction. The dominant contact direction aligns closely with the gravitational deposition direction, confirming that the geometric arrangement of particles is the structural origin of anisotropy.

- As the confining pressure increases, the shear modulus of calcareous sand increases, while the stiffness anisotropy induced by irregular particle shapes decreases. However, the degree of anisotropy varies for different particle shapes. Notably, dendritic calcareous sand undergoes a polarity reversal in anisotropy at high confining pressures, transitioning from a larger horizontal shear modulus to a larger vertical shear modulus. Confining pressure exerts a dual effect on the degree of anisotropy. On one hand, it increases the coordination number of particles, enhancing interlocking and overall stiffness; on the other hand, it increases the rolling resistance around the vertical axis. The polarity reversal in dendritic particles at confining pressures above 200 kPa arises from the pronounced vertical interlocking provided by their multi-branch structure under high pressure, causing the vertical shear stiffness to exceed the horizontal shear stiffness and resulting in a 90° shift in the dominant contact direction.

- Particle breakage reduces both the shear modulus and the degree of anisotropy in calcareous sand. At high confining pressures, particle breakage significantly weakens structural integrity by disrupting existing strong contact forces, thereby reducing overall shear stiffness. Additionally, due to the spatial anisotropy of contact normals, particle breakage predominantly disrupts strong contact forces in the vertical direction, leading to stress redistribution. This process homogenizes the distribution of contact normal, which in turn reduces the stiffness of anisotropy.

- After particle breakage, the original system of strong contact forces is disrupted, and stress redistribution compensates for the lost contact forces. Two compensation mechanisms are observed: sub-particle compensation, where broken sub-particles establish weak contacts with other particles, and surrounding particle compensation, where under isotropic confining pressure with minimal strain, the fragments fail to fill the voids and cannot bear the contact forces, leading to increased contact forces in the surrounding particles. The dominant surrounding particle compensation mechanism leads to an increase in microscopic strong+ contact forces, while strong− and weak+ contact forces decrease. This behavior is not limited to the calcareous sand examined in this study; it may also occur in other particle breakage systems.

The findings directly link the problem of anisotropic behavior in calcareous sand to the objectives of quantifying its micro-mechanical origins and the role of particle breakage. While the DEM model provides valuable insights into the stiffness anisotropy of calcareous sand, it has certain limitations. The model assumes idealized particle interactions. It does not account for all real-world complexities, such as variations in particle surface roughness or environmental conditions. Computational constraints also limit the number of simulation runs. This restricts the ability to perform systematic parametric studies, such as those based on design of experiments (DoE). Each 3D DEM simulation with breakable particles requires substantial CPU time (8–72 h per run depends on breakage). As a result, only targeted sensitivity analyses were possible—for example, varying confining pressure (50–1200 kPa), particle shape descriptors, and breakage ratios (0%, 1%, 5%, 10%).

Future studies should focus on experimental validation to confirm the numerical findings. Laboratory tests are needed to provide direct evidence for the two contact force redistribution modes proposed in this study. Researchers should also explore the effects of additional factors—such as moisture content and particle size distribution—on the mechanical behavior of calcareous sand. Future work could also incorporate more realistic particle shapes. For example, Chen et al. [] demonstrated DCGAN’s ability to generate highly realistic and morphologically diverse particle assemblages. This approach could better simulate anisotropic behaviors in natural calcareous sands. Furthermore, statistical design-of-experiment frameworks should be adopted in future studies. Such approaches would systematically explore the multidimensional parameter space of DEM simulations. They would enable quantification of interaction effects among particle morphology, contact properties, and breakage criteria. This would support model calibration and optimization within computational feasibility limits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G., K.S. and Q.Y.; Methodology, Y.G., K.S. and Q.Y.; Software, K.S.; Validation, Y.G., K.S., Q.Y., L.S. and X.T.; Formal analysis, K.S.; Investigation, Y.G., K.S. and Q.Y.; Resources, Y.G.; Data curation, K.S.; Writing—original draft, K.S.; Writing—review & editing, Y.G. and Q.Y.; Visualization, Y.G., L.S. and X.T.; Supervision, Y.G.; Project administration, Y.G.; Funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42072295) and National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC3005203).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Quan Yuan was employed by the company Guangzhou Metro Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, X.Z.; Jiao, Y.Y.; Wang, R.; Hu, M.J.; Meng, Q.S.; Tan, F.Y. Engineering characteristics of the calcareous sand in Nansha Islands, South China Sea. Eng. Geol. 2011, 120, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, H.G. Simple Shear Behavior of Calcareous and Quartz Sands. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2011, 29, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.S.; Ismail, M.A. Monotonic and cyclic behavior of two calcareous soils of different origins. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2006, 132, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.H.; Zhang, Q.F.; Ding, Z.; Xia, T.D.; Gan, X.L. Experimental and Estimation Studies of Resilient Modulus of Marine Coral Sand under Cyclic Loading. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Elmamlouk, H.; Agaiby, S. Static and cyclic behavior of North Coast calcareous sand in Egypt. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 55, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, S.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wu, B. Monotonic behavior of interface shear between carbonate sands and steel. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Long, Z.L.; Kuang, D.M.; Gong, Z.M.; Yu, P.Y.; Xu, G.B. Approach to 3D reconstruction of calcareous sand using 2D images of multi-view. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.B.; Sun, G.; Liu, J.M.; Zou, Y.S.; Yu, J.T. Structural Characteristics and Correlation Analysis of Calcareous Sand Based on 3D Reconstruction. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 4090–4097. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Su, Y.; Zou, K.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W. Coupling effects of morphology and inner pore distribution on the mechanical response of calcareous sand particles. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chai, S. Test on Lateral Earth Pressure Coefficient of Coral Sand with Some Shapes and Contents. J. Tianjin Chengjian Univ. 2020, 26, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, S.; Guo, Z.; Si, T.; Li, Y. Effect of particle shape on the liquefaction resistance of calcareous sands. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 137, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Cui, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yamamoto, H. Experimental investigation on mechanical behavior and particle crushing of calcareous sand retrieved from South China Sea. Eng. Geol. 2021, 280, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Hou, M.; Wang, J. Discrete element simulation study on mechanical behavior of cemented calcareous sand considering particle shape and breakage. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2022, 39, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Wu, H.; Gu, X.; Zhou, Q. Particle shape effects on dynamic properties of granular soils: A DEM study. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 161, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tang, H.; Shahin, M.A.; Zhao, H.; Karrech, A.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, H. Multiscale simulation study for mechanical characteristics of coral sand influenced by particle breakage. Powder Technol. 2025, 449, 120387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Haegeman, W.; Cnudde, V. Anisotropic small-strain stiffness of calcareous sand affected by sample preparation, particle characteristic and gradation. Géotechnique 2021, 71, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, K.; Yuan, Q.; Shi, T. Stiffness Anisotropy and Micro-Mechanism of Calcareous Sand with Different Particle Breakage Ratios Subjected to Shearing Based on DEM Simulations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, A.; Sharma, K.G.; Venkatachalam, K.; Gupta, A.K. Testing and modeling two rockfill materials. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2003, 129, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, H.; Ding, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, W. Influence of Particle Breakage on Critical State Line of Rockfill Material. Int. J. Geomech. 2016, 16, 04015031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, J.M.; Salami, Y. Particle breakage in granular materials—A conceptual framework. Can. Geotech. J. 2018, 55, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, P.V.; Yamamuro, J.A.; Bopp, P.A. Significance of particle crushing in granular materials. J. Geotech. Eng. 1996, 122, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Santosh, M.; Luo, Z.; Hao, J. Large igneous provinces linked to supercontinent assembly. J. Geodyn. 2015, 85, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.F.; Wang, B.S.; Chi, S.C. Particle breakage of rockfill during triaxial tests. Chinese J. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 37, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F. Characteristics of particle breakage of sand in triaxial shear. Powder Technol. 2017, 320, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; Weng, L. Experimental study on crushable coarse granular materials during monotonic simple shear tests. Geomech. Eng. 2018, 15, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tahmasebi, P.; Lin, C.; Zahid, M.A.; Dong, C.; Golab, A.N.; Ren, L. A comprehensive study on geometric, topological and fractal characterizations of pore systems in low-permeability reservoirs based on SEM, MICP, NMR, and X-ray CT experiments. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 103, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 1979, 29, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, J.J.; Wang, Z.N. Evolution of critical state of calcareous sand during particle breakage. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 43, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T.; Matsushima, T.; Yamada, Y. DEM simulation on the one-dimensional compression behavior of various shaped crushable granular materials. Granul. Matter 2013, 15, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, G.R.; Harireche, O. Discrete element modelling of soil particle fracture. Geotech. 2002, 52, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilauer, V.; Angelidakis, V.; Catalano, E.; Caulk, R.; Chareyre, B.; Chevremont, W.; Yuan, C. Yade Documentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.00611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.; Ma, H.; Yang, Z.; Jing, Y.; Tu, H. A novel coarse-grained discrete element method for simulating failure process of strongly bonded particle materials. Powder Technol. 2025, 464, 121212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladkyy, A.; Kuna, M. DEM simulation of polyhedral particle cracking using a combined Mohr–Coulomb–Weibull failure criterion. Granul. Matter 2017, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, K.; Gladky, A. Clump breakage algorithm for DEM simulation of crushable aggregates. Tribol. Int. 2022, 173, 107661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, T.; Yuan, Q.; Sun, K. The creep characteristics and related evolution of particle morphology for calcareous sand. Powder Technol. 2024, 431, 119077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokoe, K.; Lee, S.; Knox, D.P. Shear Moduli Measurements under True Triaxial Stresses. In Proceedings of the Advances in the Art of Testing Soils Under Cyclic Conditions: Proceedings of a Session/Sponsored by the Geotechnical Engineering Division in Conjunction with the ASCE Convention, Detroit, MI, USA, 24 October 1985; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- STOKOE, K.H.I.; Hwang, S.K.; Lee, J.K.; Andrus, R.D. Effects of various parameters on the stiffness and damping of soils at small to medium strains. In Proceedings of the Pre-Failure Deformation of Geomaterials: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Pre-Failure Deformation Characteristics of Geomaterials, Sapporo, Japan, 12–14 September 1994; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994; pp. 785–816. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, K.H.I.; Lee, J.N.K.; Lee, S.H.H. Characterization of soil in calibration chambers with seismic waves. In Proceedings of the Calibration Chamber Testing: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Calibration Chamber Testing/ISOCCT1, Potsdam, NY, USA, 28–29 June 1991; pp. 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.; Sharma, S.; Fahey, M. A Small True Triaxial Apparatus with Wave Velocity Measurement. Geotech. Test. J. 2005, 28, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, R.; Demars, K.; Fioravante, V.; Capoferri, R. On the Use of Multi-directional Piezoelectric Transducers in Triaxial Testing. Geotech. Test. J. 2001, 24, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, M. Fabric tensor in granular materials. In Proceedings of the Deformation and Failure of Granular Materials, Delft, The Netherlands, 31 August–3 September 1982; IUTAM Symposium: Delft, The Netherlands, 1982; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, B.O. Crushing of Soil Particles. J. Geotech. Eng. 1985, 111, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C. Numerical simulations of deviatoric shear deformation of granular media. Geotechnique 2000, 50, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjai, F.; Wolf, D.E.; Jean, M.; Moreau, J.J. Bimodal Character of Stress Transmission in Granular Packings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.R.; Wood, D.M. Point load tests and strength measurements for brittle spheres. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2009, 46, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Yu, J.Y. Microstructural response during shearing process of dense sand. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2021, 52, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Gao, Y. Particle Crushing and Anisotropy of Calcareous Sand During Triaxial Shearing. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Architectural, Civil and Hydraulic Engineering (ICACHE 2023), Online, 14 October 2023; Atlantis Press International BV: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 228, pp. 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Guo, W.; Luo, F.; Li, M. Simulation experimental investigations on particle breakage mechanism and fractal characteristics of mixed size gangue backfill materials. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Ma, L.; Shi, X.; Li, H.; Zhu, H. Randomly generating realistic calcareous sand for directional seepage simulation using deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 7297–7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).