Taxonomic and Genomic Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 from Baengnokdam Crater Lake, Mt. Halla, and Its Cosmeceutical Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Isolation and Cultivation of the Strain

2.3. Phylogenetic and Genomic Analysis

2.4. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

2.5. Assembly Validation and Annotation

2.6. Physiological, Biochemical, and Chemotaxonomic Characterization

2.7. Digital DNA–DNA Hybridization (dDDH) Analysis Between Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 and Related Species

2.8. Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) Analysis Between Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 and Brevibacillus laterosporus DSM 25

2.9. In Silico Prediction of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42

2.10. Morphological Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42

2.11. Isolation, Purification, and Structural Identification of the Bioactive Compound from Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42

2.12. Assessment of Anti-Melanogenic Activity of Maculosin in B16F10 Melanoma Cells

2.13. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.2. Taxonomic Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42

3.3. Morphological Features Under Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.4. Genome Assembly and Annotation of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42

3.5. Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 as a Novel Strain via dDDH Analysis

3.6. Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 as a Novel Strain via ANI Analysis

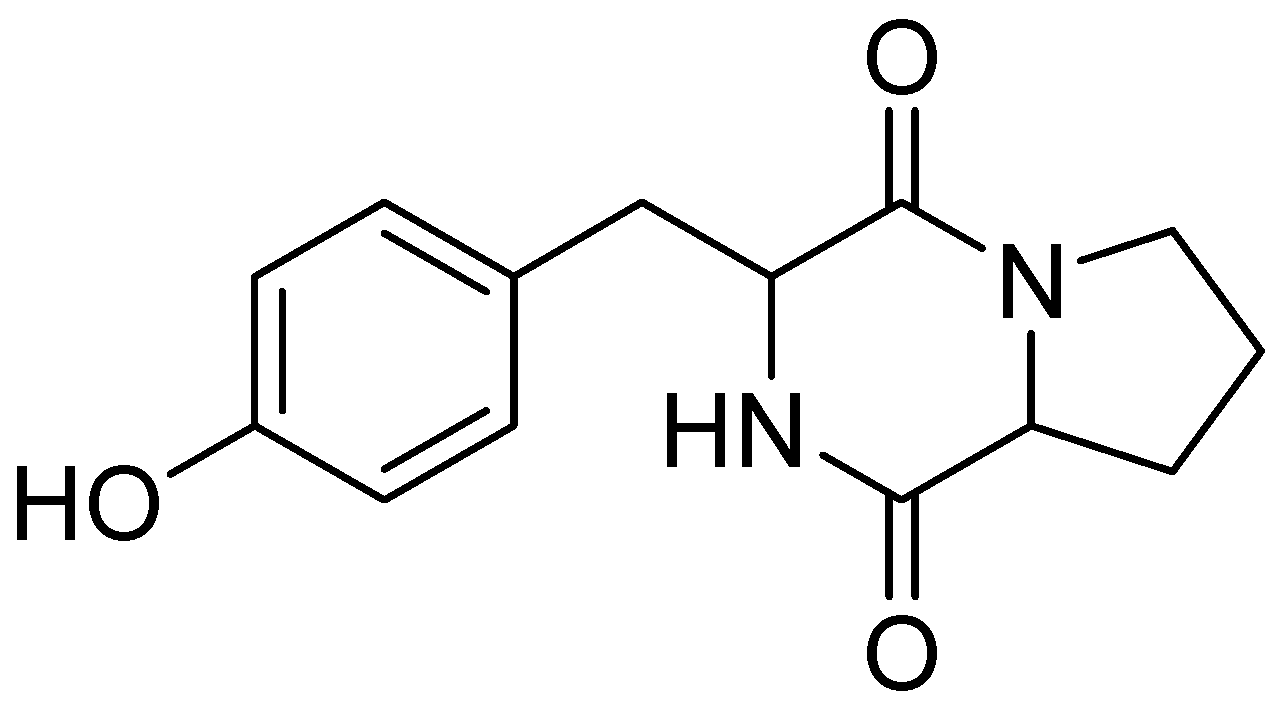

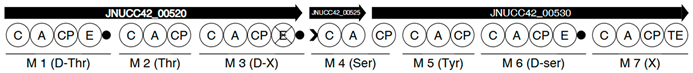

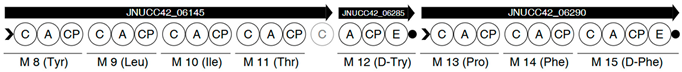

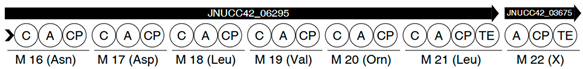

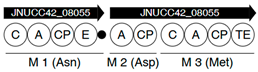

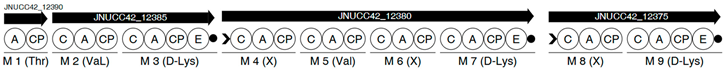

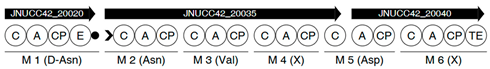

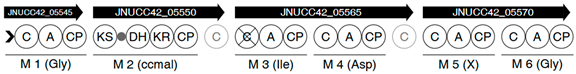

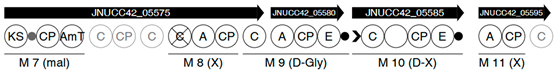

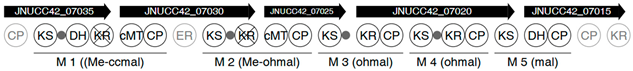

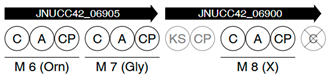

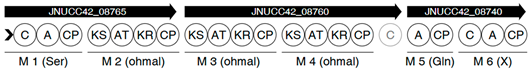

3.7. In Silico Prediction of Secondary Metabolites and Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Analysis

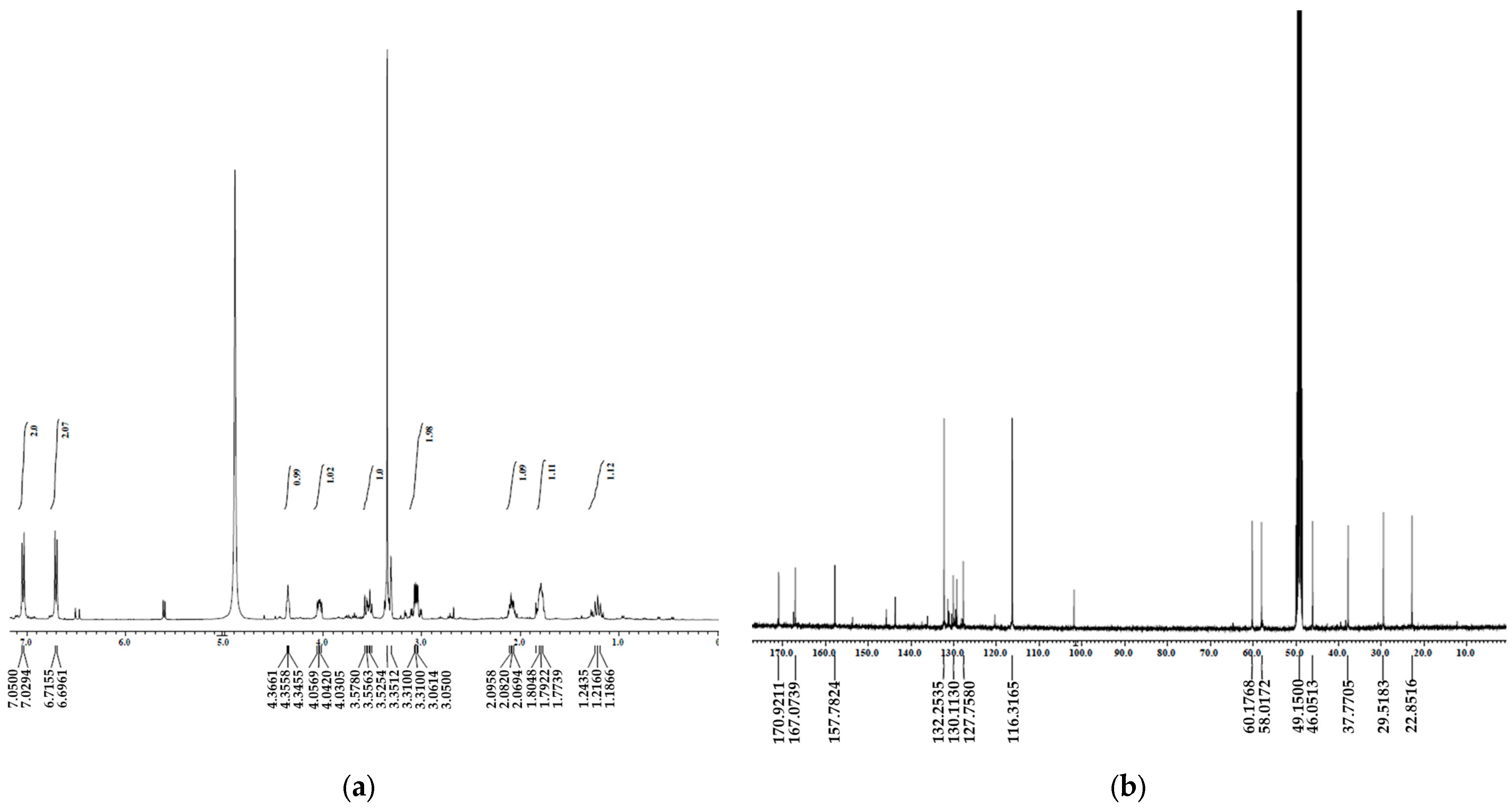

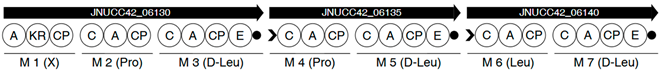

3.8. Isolation and Structural Identification of Maculosin [Cyclo(L-Pro-L-Tyr)] from Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42

3.9. Cytotoxicity and Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Maculosin in α-MSH-Stimulated B16F10 Melanocytes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, U.S.; Hong, S.S. Volcanological History of the Baengnokdam Summit Crater Area, Mt. Halla in Jeju Island, Korea. J. Petrol. Soc. Kor. 2017, 26, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, V.H.; Kurth, D.; Ordoñez, O.F.; Belfiore, C.; Luccini, E.; Salum, G.M.; Piacentini, R.D.; Farías, M.E. High-Up: A Remote Reservoir of Microbial Extremophiles in Central Andean Wetlands. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarracín, V.H.; Gärtner, W.; Farias, M.E. Forged Under the Sun: Life and Art of Extremophiles from Andean Lakes. Photochem. Photobiol. 2016, 92, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.N.; Hyun, C.G. Complete Genome Sequence and Cosmetic Potential of Viridibacillus sp. JNUCC6 Isolated from Baengnokdam, the Summit Crater of Mt. Halla. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, X.; Hyun, C.G. Isolation, Characterization, Genome Annotation, and Evaluation of Hyaluronidase Inhibitory Activity in Secondary Metabolites of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 41: A Comprehensive Analysis through Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, X.; Hyun, C.G. Isolation, Characterization, Genome Annotation, and Evaluation of Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity in Secondary Metabolites of Paenibacillus sp. JNUCC32: A Comprehensive Analysis through Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikita, K.; Kavya, I.K.; Shrivastava, S.; Ghosh, A.; Rawat, V.S.; Sodhi, K.K.; Kumar, M. Perspectives on the microorganism of extreme environments and their applications. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Aulitto, M. Advances in Extremophile Research: Biotechnological Applications through Isolation and Identification Techniques. Life 2024, 14, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzucu, M. Extremophilic Solutions: The Role of Deinoxanthin in Counteracting UV-Induced Skin Harm. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 8372–8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, F.; Costanzo, E.; Ionata, E.; Marcolongo, L. Biotechnological Potential of Extremophiles: Environmental Solutions, Challenges, and Advancements. Biology 2025, 14, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multisanti, C.R.; Celi, V.; Dibra, A.; Pintus, A.; Calogero, R.; Rizzo, C.; Faggio, C. Microbial Blue Bioprospecting: Exploring the Advances of Compounds Post-Discovery. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shida, O.; Takagi, H.; Kadowaki, K.; Komagata, K. Proposal for two new genera, Brevibacillus gen. nov. and Aneurinibacillus gen. nov. Int. J. Sys. Bacteriol. 1996, 46, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.K.; Bisht, S.S.; De Mondal, S.; Senthil Kumar, N.; Gurusubramanian, G.; Panigrahi, A.K. Brevibacillus as a biological tool: A short review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 105, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, F.; Zhou, L.; Wen, C.; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of Brevibacillus brevis BF19 reveals its biocontrol potential against bitter gourd wilt. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizukami, M.; Hanagata, H.; Miyauchi, A. Brevibacillus expression system: Host–vector system for efficient production of secretory proteins. Cur. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baindara, P.; Dinata, R. Brevibacillus laterosporus: A co-evolving machinery of diverse antimicrobial agents. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zai, X.; Weng, G.; Ma, X.; Deng, D. Brevibacillus laterosporus: A probiotic with important applications in crop and animal production. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dai, X.; Zhang, D.; Zeng, Y.; Ni, X.; Pan, K. Evaluation of probiotic properties of a Brevibacillus laterosporus strain. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Chun, J. Introducing EzBioCloud: A taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, H.M.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, S.; Afolayan, A.O.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN in 2025: A Global Core Biodata Resource for genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes within DSMZ Digital Diversity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, gkaf1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Oh, H.S.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korlach, J.; Bjornson, K.P.; Chaudhuri, B.P.; Cicero, R.L.; Flusberg, B.A.; Gray, J.J.; Holden, D.; Saxena, R.; Wegener, J.; Turner, S.W. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Methods Enzymol. 2010, 472, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, D.R.; Balasubramanian, S.; Swerdlow, H.P.; Smith, G.P.; Milton, J.; Brown, C.G.; Hall, K.P.; Evers, D.J.; Barnes, C.L.; Bignell, H.R.; et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 2008, 456, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.S.; Alexander, D.H.; Marks, P.; Klammer, A.A.; Drake, J.; Heiner, C.; Clum, A.; Copeland, A.; Huddleston, J.; Eichler, E.E.; et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2013, 10, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.J.; Abeel, T.; Shea, T.; Priest, M.; Abouelliel, A.; Sakthikumar, S.; Cuomo, C.A.; Zeng, Q.; Wortman, J.; Young, S.K.; et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marçais, G.; Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurture, G.W.; Sedlazeck, F.J.; Nattestad, M.; Underwood, C.J.; Fang, H.; Gurtowski, J.; Schatz, M.C. GenomeScope: Fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2202–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, F.A.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ioannidis, P.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3210–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, J.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A.; Christensen, H.; Arahal, D.R.; da Costa, M.S.; Rooney, A.P.; Yi, H.; Xu, X.W.; De Meyer, S.; et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19126–19131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Ouk Kim, Y.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. OrthoANI: An improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goris, J.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Klappenbach, J.A.; Coenye, T.; Vandamme, P.; Tiedje, J.M. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, N.J.; Mukherjee, S.; Ivanova, N.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Mavrommatis, K.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Pati, A. Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 6761–6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesco, R.; Trujillo, M.E. Update on the proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; Augustijn, H.E.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Koetsier, R.A.; Williams, S.E.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W32–W38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, S.C.; Charkoudian, L.K.; Medema, M.H. A standardized workflow for submitting data to the Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster (MIBiG) repository: Prospects for research-based educational experiences. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2018, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röttig, M.; Medema, M.H.; Blin, K.; Weber, T.; Rausch, C.; Kohlbacher, O. NRPSpredictor2—A web server for predicting NRPS adenylation domain specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W362–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemert, N.; Podell, S.; Penn, K.; Badger, J.H.; Allen, E.; Jensen, P.R. The natural product domain seeker NaPDoS: A phylogeny based bioinformatic tool to classify secondary metabolite gene diversity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.H.; Hwang, B.S.; Choi, A.; Chung, E.J. Isolation and characterization of strain Rouxiella sp. S1S-2 producing antibacterial compound. Korean J. Microbiol. 2020, 56, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, B.; Maharjan, R.; Rajbhandari, P.; Aryal, N.; Aziz, S.; Bhattarai, K.; Baral, B.; Malla, R.; Bhattarai, H.D. Maculosin, a non-toxic antioxidant compound isolated from Streptomyces sp. KTM18. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suutari, M.; Laakso, S. Microbial fatty acids and thermal adaptation. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1994, 20, 285–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliakus, M.F.; van der Oost, J.; Kengen, S.W.M. Adaptations of archaeal and bacterial membranes to variations in temperature, pH and pressure. Extremophiles 2017, 21, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stierle, A.C.; Cardellina, J.H.; Strobel, G.A. Maculosin, a host-specific phytotoxin for spotted knapweed from Alternaria alternata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 8008–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driche, E.H.; Badji, B.; Bijani, C.; Belghit, S.; Pont, F.; Mathieu, F.; Zitouni, A. A New Saharan Strain of Streptomyces sp. GSB-11 Produces Maculosin and N-acetyltyramine Active Against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogenic Bacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, S.; Cimmino, A.; Masi, M.; Evidente, A. Bacterial Lipodepsipeptides and Some of Their Derivatives and Cyclic Dipeptides as Potential Agents for Biocontrol of Pathogenic Bacteria and Fungi of Agrarian Plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 4591–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, C.; Horyanto, D.; Stanley, D.; Cock, I.E.; Chen, X.; Feng, Y. Antimicrobial Properties of Bacillus Probiotics as Animal Growth Promoters. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, C.; Cai, X.; Long, H.; Zhang, X.; Huang, A.; Zeng, Y.; Ren, W.; Xie, Z. Analysis of the Antioxidant Composition of Low Molecular Weight Metabolites from the Agarolytic Bacterium Alteromonas macleodii QZ9-9: Possibilities for High-Added Value Utilization of Macroalgae. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Liang, X.; Kim, H.M.; Hyun, C.G. In Vitro and In Silico Studies of Maculosin as a Melanogenesis and Tyrosinase Inhibitor. Molecules 2025, 30, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Ischia, M.; Wakamatsu, K.; Napolitano, A.; Briganti, S.; Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Kovacs, D.; Meredith, P.; Pezzella, A.; Picardo, M.; Sarna, T.; et al. Melanins and melanogenesis: Methods, standards, protocols. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013, 26, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoi, J.; Abe, E.; Suda, T.; Kuroki, T. Regulation of melanin synthesis of B16 mouse melanoma cells by 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and retinoic acid. Cancer Res. 1985, 45, 1474–1478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meena, M.; Samal, S. Alternaria host-specific (HSTs) toxins: An overview of chemical characterization, target sites, regulation and their toxic effects. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, D.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lian, X.Y. A rare diketopiperazine glycoside from marine-sourced Streptomyces sp. ZZ446. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yousef, A.E. Antimicrobial peptides produced by Brevibacillus spp.: Structure, classification and bioactivity: A mini review. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | (a) Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 | (b) B. laterosporus DSM 25T |

|---|---|---|

| pH range | ||

| pH 4.0~6.0 | + | – |

| pH 7.0 | +++ | ++ |

| pH 8.0 | +++ | + |

| pH 9.0 | +++ | – |

| pH 10.0 | + | – |

| NaCl tolerance | ||

| 1% | +++ | ++ |

| 3% | ++ | + |

| 5~20% | – | – |

| Temperature range | ||

| 10~20 °C | – | – |

| 30 °C | ++ | ++ |

| 37 °C | – | + |

| 40 °C | – | – |

| Assay | (a) Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 | (b) B. laterosporus DSM 25T | Diagnostic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| API 50CHB | |||

| D-Glucose | + | + | Shared trait |

| D-Fructose | – | + | B. laterosporus DSM 25 specific |

| Esculine | + | + | Shared trait |

| API ZYM: | |||

| Alkine phosphatase | + | + | Shared trait |

| Naphtol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase | + | + | Shared trait |

| Fatty Acid (%) | (a) Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 | (b) B. laterosporus DSM 25T |

|---|---|---|

| Straight-chain | ||

| 12:0 | Tr | – |

| 13:0 | Tr | – |

| 14:0 2OH | Tr | – |

| Branched | ||

| 15:0 iso | 27.78 | 35.39 |

| 15:0 anteiso | 37.24 | 38.62 |

| 16:0 iso | 4.21 | 4.46 |

| 15:1 anteiso A | Tr | – |

| 15:0 iso 3OH | Tr | – |

| Unsaturated | ||

| 14:1 ω5c | Tr | – |

| 15:1 ω5c | 2.27 | – |

| 16:1 ω11c | 1.40 | – |

| 18:1 ω9c | Tr | – |

| Lipid Class | (a) Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 | (b) B. laterosporus DSM 25T | Diagnostic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | + | + | Shared trait |

| Phosphatidylglycerol (PG) | + | + | Shared trait |

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | + | + | Shared trait |

| Unidentified aminophospholipid (APL) | + | + | Shared trait |

| Unidentified aminolipid (AL) | + | – | Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 specific |

| Unidentified phospholipid (PL) | + | + | Shared trait |

| Unidentified lipid (L) | + | + | Shared trait |

| Brevibacillus sp. Strain JNUCC 42 | |

|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 4,925,472 |

| Total number of contigs | 1 |

| Contigs N50 (bp) | 4,925,472 |

| Plasmid | 2 |

| G+C content (%) | 40.5 |

| Genome coverage | 197× |

| Number of chromosomes | 1 |

| Total number of predicted genes | 4674 |

| Total number of protein coding genes | 4272 |

| Total number of pseudogenes | 250 |

| Total number of tRNA-coding genes | 111 |

| Total number of rRNA-coding genes (5S, 16S, 23S) | 12, 12, 12 |

| Total number of ncRNA-coding genes | 5 |

| Subject Strain | dDDH (d0, in %) | C.I. (d0, in %) | dDDH (d4, in %) | C.I. (d4, in %) | dDDH (d6, in %) | C.I. (d6, in %) | G+C Content Difference (in %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brevibacillus laterosporus DSM 25 | 52.5 | [49.0–55.9] | 32.8 | [30.4–35.3] | 47.2 | [44.2–50.2] | 0.23 |

| Brevibacillus schisleri ATCC 35690 | 13 | [10.3–16.3] | 32.1 | [29.7–34.6] | 13.4 | [11.1–16.2] | 6.53 |

| Brevibacillus gelatini DSM 100115 | 12.8 | [10.1–16.1] | 30.2 | [27.8–32.7] | 13.2 | [10.9–16.0] | 11.25 |

| Brevibacillus formosus DSM 9885 | 12.8 | [10.1–16.1] | 30 | [27.6–32.5] | 13.2 | [10.9–16.0] | 6.67 |

| Brevibacillus panacihumi JCM 15085 | 12.8 | [10.1–16.0] | 30 | [27.6–32.5] | 13.2 | [10.8–15.9] | 10.24 |

| Bacillus timonensis MM10403188 | 12.6 | [9.9–15.9] | 29.6 | [27.2–32.1] | 13 | [10.7–15.8] | 3.5 |

| Brevibacillus invocatus JCM 12215 | 12.9 | [10.2–16.2] | 29.4 | [27.0–31.9] | 13.3 | [10.9–16.0] | 8.18 |

| Peribacillus huizhouensis DSM 105481 | 12.7 | [10.0–15.9] | 29.3 | [27.0–31.8] | 13.1 | [10.7–15.8] | 3.51 |

| Brevibacillus parabrevis NRRL NRS-605 | 12.8 | [10.1–16.1] | 28.7 | [26.3–31.2] | 13.2 | [10.8–16.0] | 11.42 |

| Bacillus cihuensis FJAT-14515T | 12.6 | [9.9–15.8] | 28.6 | [26.2–31.1] | 13 | [10.7–15.7] | 3.7 |

| Brevibacillus fortis NRRL NRS-1210 | 12.9 | [10.2–16.2] | 28.1 | [25.7–30.6] | 13.3 | [10.9–16.1] | 6.4 |

| Bacillus rhizoplanae CIP 111899T | 12.7 | [10.0–16.0] | 27.7 | [25.4–30.2] | 13.1 | [10.8–15.9] | 4.36 |

| Paenibacillus roseopurpureus MBLB1832 | 12.7 | [10.0–16.0] | 27 | [24.7–29.5] | 13.1 | [10.8–15.9] | 6.12 |

| Brevibacillus fluminis JCM 15716 | 12.9 | [10.2–16.1] | 25.1 | [22.8–27.6] | 13.3 | [10.9–16.0] | 9.61 |

| Neobacillus kokaensis ATCC 31382 | 12.7 | [10.0–15.9] | 23.8 | [21.5–26.3] | 13 | [10.7–15.8] | 1.23 |

| Brevibacillus dissolubilis CHY01 | 13.1 | [10.4–16.4] | 22.6 | [20.3–25.0] | 13.4 | [11.1–16.2] | 9.81 |

| Allocoprobacillus halotolerans LH1062 | 12.7 | [10.0–15.9] | 21.4 | [19.2–23.9] | 13.1 | [10.7–15.8] | 9.49 |

| Brevibacillus daliensis YIM B02290 | 14.9 | [12.0–18.3] | 21.1 | [18.9–23.5] | 15.1 | [12.6–17.9] | 0.14 |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| OrthoANIu value (%) | 87.10% |

| Genome A length (bp) | 4,924,560 |

| Genome B length (bp) | 5,399,880 |

| Average aligned length (bp) | 2,587,651 |

| Genome A coverage (%) | 52.55 |

| Genome B coverage (%) | 47.92 |

| Region | Type | From | To | Similarity Confidence | Most Similar Known Cluster | BGC Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NRPS-like | 21,621 | 63,033 | High | Kolossin | NRPS: Type I |

| 2 | NRPS, Betalactone | 77,952 | 144,990 | Low | Pelgipeptin A/B/C/D | NRPS: Type I |

| 3 | Cyclic-lactone-autoinducer | 643,636 | 664,148 | – | – | – |

| 4 | T3PKS | 875,138 | 916,193 | – | – | – |

| 5 | NRPS, TransAT-PKS-like | 1,079,447 | 1,175,950 | Low | Pelgipeptin A/B/C/D | NRPS: Type I |

| 6 | NRPS, NRPS-like | 1,250,225 | 1,421,338 | Low | Tyrocidine | NRPS: Type I |

| 7 | NRPS, T1PKS, TransAT-PKS | 1,481,493 | 1,587,122 | Low | Basiliskamide A/B | PKS |

| 8 | NRPS | 1,748,344 | 1,801,170 | – | – | – |

| 9 | NRPS-like, Terpene-precursor | 1,821,578 | 1,872,358 | – | – | – |

| 10 | NRPS, T1PKS | 1,895,712 | 1,963,165 | Low | Zwittermicin A | NRPS: Type I + PKS |

| 11 | Terpene | 1,965,095 | 1,986,993 | – | – | – |

| 12 | Cyclic-lactone-autoinducer | 2,270,172 | 2,290,830 | – | – | – |

| 13 | NRPS, NRPS-like, lanthipeptide-class-I | 2,669,622 | 2,764,544 | High | Bogorol A | NRPS: Type I |

| 14 | NIS-siderophore | 2,830,298 | 2,861,989 | High | Petrobactin | Other: Other |

| 15 | Cyclic-lactone-autoinducer | 2,947,446 | 2,968,092 | – | – | – |

| 16 | Cyclic-lactone-autoinducer | 3,549,524 | 3,570,170 | – | – | – |

| 17 | NRPS | 4,039,413 | 4,085,196 | – | – | – |

| 18 | NRPS | 4,228,982 | 4,294,481 | – | – | – |

| 19 | Azole-containing RiPP | 4,543,398 | 4,566,944 | – | – | – |

| 20 | RiPP-like | 4,739,197 | 4,750,937 | – | – | – |

| 21 | NRPS | 4,865,946 | 4,913,580 | – | – | – |

| Region | |

|---|---|

| 2 |  |

| 6 |  |

| |

| |

| 8 |  |

| 13 |  |

| |

| 17 |  |

| 18 |  |

| Region | |

|---|---|

| 5 |  |

| |

| 7 |  |

| |

| 10 |  |

| Position | δH, Mult. (J in Hz) | δC, Mult. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.35 (1H, m) | 58.0 |

| 2 | 167.0 | |

| 3 | 4.04 (1H, m) | 60.1 |

| 4 | 170.9 | |

| 5 | 2.08 (1H, m) 1.24 (1H, m) | 29.5 |

| 6 | 1.79 (1H, m) | 22.8 |

| 7 | 3.54 (1H, m) 3.35 (1H, m) | 46.0 |

| 8 | 3.06 (2H, m) | 37.7 |

| 9 | 127.7 | |

| 10 | 7.03 (1H, d, 8.2) | 132.2 |

| 11 | 6.70 (1H, d, 8.2) | 116.3 |

| 12 | 157.7 | |

| 13 | 6.70 (1H, d, 8.2) | 116.3 |

| 14 | 7.03 (1H, d, 8.2) | 132.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-H.; Moon, M.-Y.; Ko, M.-S.; Hyun, C.-G. Taxonomic and Genomic Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 from Baengnokdam Crater Lake, Mt. Halla, and Its Cosmeceutical Potential. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312681

Lee J-H, Moon M-Y, Ko M-S, Hyun C-G. Taxonomic and Genomic Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 from Baengnokdam Crater Lake, Mt. Halla, and Its Cosmeceutical Potential. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312681

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jeong-Ha, Mi-Yeon Moon, Mi-Sun Ko, and Chang-Gu Hyun. 2025. "Taxonomic and Genomic Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 from Baengnokdam Crater Lake, Mt. Halla, and Its Cosmeceutical Potential" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312681

APA StyleLee, J.-H., Moon, M.-Y., Ko, M.-S., & Hyun, C.-G. (2025). Taxonomic and Genomic Characterization of Brevibacillus sp. JNUCC 42 from Baengnokdam Crater Lake, Mt. Halla, and Its Cosmeceutical Potential. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312681