Abstract

Focusing on underground reservoir coal pillar dams subjected to long-term water immersion, this study employed a self-developed non-destructive water saturation apparatus to prepare monolithic and composite coal–rock specimens with varying moisture conditions. Through uniaxial compression tests combined with acoustic emission (AE) monitoring technology, the mechanical failure characteristics and energy dissipation behavior of these specimens were systematically investigated. The results indicated that both the UCS and elastic modulus (E) of the single-rock specimens decreased with increasing water content. Conversely, the mechanical properties of the composite specimens were significantly influenced by the properties and water saturation state of the rock components within the composite. When the rocks within the composite specimens share identical moisture conditions, higher rock strength correlates with greater specimen strength and strain. Under identical lithological conditions, the peak stress (σc), peak strain (εc), and elastic modulus (E) of the composite specimens decreased with increasing rock moisture content, which exhibited reductions of 45%, 21.8%, and 13.5% in σc, εc, and E, respectively, under saturated conditions. Acoustic emission (AE) monitoring data revealed that AE events in coal–rock composite specimens under uniaxial loading exhibited distinct spatial distribution patterns. Furthermore, as the rock moisture content increased, the ultimate failure mode of the composite specimen progressively shifted from shear failure within the coal matrix toward tensile failure of the composite as a whole. An analysis of the energy characteristics of coal–rock composite specimens under uniaxial compression revealed that rock properties and moisture content significantly influence energy absorption and conversion during loading. With increasing rock moisture content, the total energy, elastic strain energy, and dissipated energy at the peak load exhibited decreasing trends, reflecting the weakening effect of water on energy dissipation in coal–rock composites. This study systematically investigated the instability mechanisms of coal–rock composites from three perspectives—mechanical properties, failure modes, and energy dissipation—thereby providing valuable insights for evaluating the long-term stability of underground reservoir coal pillar dams subjected to prolonged water immersion.

1. Introduction

Underground reservoirs in coal mines utilize goafs as storage spaces to safely store and use water through the construction of coal pillar dams and artificial dams [1,2,3]. Between these two, coal pillar dams serve as critical rock masses within underground reservoirs, bearing not only the overburden pressure but also continuous water immersion from the stored water in the goafs. The stability of coal pillar dams under water immersion is fundamentally governed by water–rock (coal) interactions. Extensive research in this field has established that water infiltration significantly degrades mechanical parameters of rocks, including peak strength and elastic modulus [4,5,6,7,8]. Based on these well-documented weakening mechanisms, rational design approaches for coal pillar dam width and stability assessment have been developed, thereby providing a technical foundation for the large-scale implementation of underground reservoirs in coal mines [9,10,11]. However, engineering practice indicates that the stratigraphic composition of long-distance coal pillar dams exhibits zonal variations, leading to zone failure under identical mining stresses. Furthermore, failure patterns differ for the same lithology under varying water saturation conditions. Compared to pure coal specimens, the deformation and failure characteristics of coal–rock composite specimens more closely approximate the actual failure behavior of in situ engineering coal bodies. Consequently, a dual-medium model has been proposed to investigate the instability and failure characteristics of coal pillar dams under geological influence [12].

Regarding laboratory testing of the mechanical properties of coal–rock composite specimens, uniaxial compression tests have been conducted. These investigations revealed the influence of factors such as lithological combinations, coal-to-rock height ratios, and contact surface inclination angles on mechanical parameters, including strength and deformation under uniaxial loading conditions. The mechanical behavior of coal–rock composites is largely governed by the coal matrix within the composite. Under cyclic loading and unloading conditions, the damage to and failure of coal–rock composites exhibit a more fragmented pattern than under uniaxial loading [13,14,15,16]. Acoustic emission (AE) monitoring technology has been employed to analyze the microscopic damage mechanisms [17,18]. Using acoustic emission monitoring technology, the fracture evolution behavior of coal–rock composite specimens during uniaxial loading has been analyzed, revealing the acoustic–thermal effects and failure mechanisms at the microstructural level [19,20,21]. Focusing on the time effects during the load-bearing process of coal–rock composites, graded loading creep experiments have been designed on composite specimens to investigate the creep characteristics of coal under the influence of overlying rock [22,23]. For water-rich coal–rock bodies, studies have examined the evolution of mechanical properties and damage patterns under water–rock interactions, revealing that the strength degradation of coal–rock composites exhibits certain time effects and heterogeneity [24,25].

Considering the loading rates, dynamic loading and combined dynamic-static loading tests have been conducted on coal–rock composites. These tests analyzed the mechanical responses and failure modes under varying stress conditions and identified the influence of rock properties on coal failure within the composite under identical stress conditions. The findings revealed distinct macroscopic responses and precursor AE signals in coal–rock composites subjected to high static loads [26,27,28]. Further, based on experimental data, a nonlinear mechanical model was established for the failure behavior of coal–rock assemblies. Using the model, key factors influencing the overall mechanical properties were identified and the distinct stages of crack evolution during loading processes summarized [29]. Another study focused on the coal within composite specimens and developed a damage-constitutive model for coal under uniaxial loading conditions. This model was applied to analyze the damage progression in coal pillars subjected to dynamic and static loads [30]. Furthermore, scholars have systematically examined the effects of the height ratio [31,32], lithology [33,34], dip angle of the contact surface [35,36], and combination patterns [37] in coal–rock composites on their energy evolution, thereby shedding further light on the energy-driven mechanisms behind the instability and failure of such composites. Theoretical analyses indicate that the mechanical properties of coal–rock composite specimens more accurately reflect the mechanical behavior of underground engineering coal bodies. Furthermore, lithological combinations, coal–rock height ratios, and contact surfaces exert significant influence on the mechanical performance of coal–rock composites [38,39,40,41].

In addition to laboratory testing, discrete element software such as PFC and 3DEC [42,43,44,45] has been employed to establish parallel bonding models of coal–rock composites. These models simulated the macroscopic mechanical properties under varying lithological combinations and coal–rock height conditions while investigating the AE characteristics, crack propagation processes, and failure modes during loading. Through numerical simulation, researchers have clarified the microscopic failure mechanisms of coal–rock composites, thereby validating the results obtained from laboratory experiments.

In summary, while significant research has been conducted on the mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of coal–rock composites with varying characteristics—including combination types, height ratios, and interfacial geometries—resulting in substantial findings, systematic investigations into the mechanical behavior of such composites under different moisture content conditions remain lacking. Therefore, it is essential to study the mechanical performance of coal–rock combinations under varying roof lithologies and moisture states. This study employed a proprietary non-destructive water saturation apparatus to conduct water saturation tests on coal and rock. Four coal–rock monolithic and nine composite specimens were tested under varying water content conditions. Uniaxial compression tests were performed on the specimens, and their mechanical properties, AE characteristics, macroscopic fracture patterns, and energy dissipation patterns were determined. This provides a foundation for the design, stability monitoring, and early warnings for coal pillar dams.

2. Sample Preparation and Test Scheme

2.1. Sample Preparation

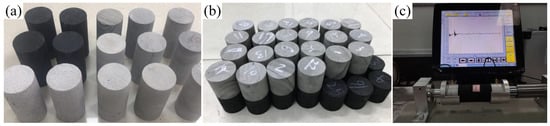

Large coal samples (300 mm × 300 mm × 200 mm) were selected from 33,301 return drift of the 3-1 coal seam at the Chahasu Coal Mine in Ordos City, Inner Mongolia. Roof rock cores (Φ75 mm) were drilled from the same area. The samples were sealed in cling film and transported to the laboratory in foam-lined wooden boxes. In the laboratory, samples were further drilled and ground perpendicularly to the rock bedding to produce standard specimens with a diameter of 50 mm and heights of 50–100 mm, as illustrated in Figure 1. In accordance with the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM) regulations, specimen end faces were orientated perpendicularly to the axial direction (with an error margin of ≤0.001 radians) and nonparallelism not exceeding 0.02 mm. The processed specimens comprised four lithologies: coal, sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone. A P wave (RSM-SY6, Wuhan Zhongyan Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China, sampling frequency: 0.1 μs, pulse width: 20 μs) was used to eliminate specimens with significant velocity variations within the same lithology. This ensured homogeneity among specimens of identical lithology and minimized experimental error. Table 1 presents the measured basic physical parameters of the specimens, revealing minimal dispersion and high consistency across all samples.

Figure 1.

Standard samples. (a) Pure coal and rock samples; (b) coal–rock combined samples; (c) P-wave testing of the samples.

Table 1.

Physical properties of specimens.

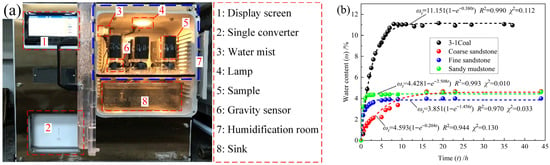

In this experiment, we investigated the mechanical properties of roof–coal seam composite structures under water, necessitating non-destructive water immersion treatment of the samples. The procedure is as follows: coal samples were dried in a vacuum-drying oven (Model 101-2, Changge Mingtu Machinery Co., Ltd.) at 105 °C for 5 h. Subsequently, the samples were immersed in water using our proprietary non-destructive water immersion apparatus [46,47], as illustrated in Figure 2a. The non-destructive water immersion apparatus incorporated an air humidifier that converted water from the reservoir into mist. This mist was channeled into the humidification chamber through a pipe to maintain constant humidity. Changes in the gravitational weight of the coal sample within the humidification chamber were monitored in real time using sensors. These measurements were converted using a signal converter and displayed on a screen as a dynamic moisture content curve.

Figure 2.

Non-destructive water immersion treatment of samples. (a) Structure of non-destructive water immersion device [46,47] and (b) water content curve.

Using this apparatus, water content curves of the specimens with respect to time were obtained, as shown in Figure 2b. The saturated water content of coal, sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone was 11.06%, 4.56%, 4.67%, and 4.0%, respectively. In accordance with the experimental objectives, specimens of sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone were prepared in dry, natural, and saturated states, respectively, along with coal specimens in their natural state (where the pristine specimen’s moisture content was half the saturated moisture content). Finally, using an epoxy resin adhesive, the sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone specimens at different moisture states were bonded separately to the coal, forming Φ50 × 100 mm sandy mudstone–coal, coarse sandstone–coal, and fine sandstone–coal cylindrical composite standard specimens. Because the epoxy resin adhesive was very thin, the width of the adhesive substances at the interface between the rock and coal sample was very small and can be neglected. The experiment used three types of pure rock samples, one type of pure coal sample, and nine types of coal–rock combined samples, and each type had at least three samples. The sample labels and combination forms are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lithology combinations and coal–rock height ratios of the samples.

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

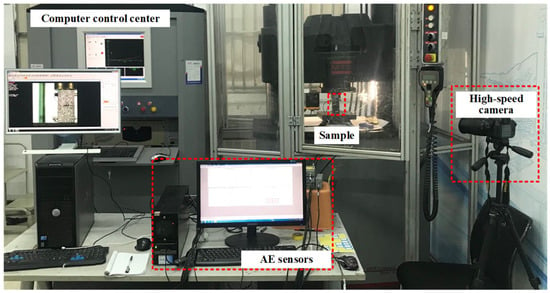

The uniaxial loading testing system employed an electrohydraulic servo universal testing machine (MTS C64.106/10; MTS Industrial Systems (China) Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). This system can facilitate mechanical tests, such as compression and shear, on coal–rock specimens. The testing machine employs an electrohydraulic servo control with a maximum test force of 1000 kN, a load measurement accuracy of ±0.5%, and a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. Displacement measurement accuracy is ±0.5%, and strain measurement accuracy is ±0.5%. The testing system and monitoring equipment are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Uniaxial compression testing of samples.

2.3. Experimental Methods

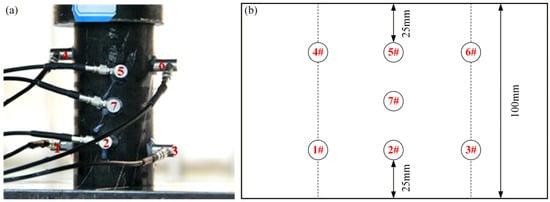

An AE monitoring system (PCI-2, Physic Acoustics Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) was employed to acquire AE energy and its cumulative values during the loading of the coal rock specimens. This monitoring system featured eight selectable parameter channels, each equipped with an 18-bit analog-to-digital converter and a frequency range of 1 kHz to 3 MHz. Software control enabled the selection of four high-pass and six low-pass filter ranges. To ensure experimental consistency, all specimens (including both homogeneous monolithic and coal–rock composite specimens) used an identical AE sensor layout. Seven AE sensors (NANA-30, Acoustic Physics Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) were bonded to the specimen surface using a thermoplastic adhesive. Specifically, on the front face of the specimen, sensors 2, 7, and 5 were arranged axially, with sensor 7 positioned at the midpoint between 2 and 5. On the two side faces, sensors 1 and 4, as well as 3 and 6, were symmetrically distributed. Each sensor was positioned 25 mm from the upper and lower ends of the specimen to form a three-dimensional spatial monitoring network covering the specimen surface (Figure 4). The primary technical parameters of the AE monitoring system are detailed in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Acoustic emission (AE) sensor layout diagram (1–7 denote the AE sensors). (a) Physical diagram. (b) Exploded view.

Table 3.

Technical parameters of acoustic emission (AE) probe.

To capture the fracture morphology of the composite specimens under uniaxial loading, a digital single-lens reflex camera (D5200, Nikon (China) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used to document the entire failure process. This camera features a 24.1-megapixel CMOS sensor and an EXPEED 3 image processor, delivering high image clarity amid complex, noisy backgrounds. The camera was positioned approximately 1.5 m in front of and to the left of the specimen. At the initiation of each test, the loading system, acoustic emission monitoring system, and camera were simultaneously activated to record data. Displacement loading was applied at a rate of 0.03 mm/min.

The mechanical parameters of the specimens were determined through uniaxial compression tests. It should be specifically noted that the elastic moduli (E) of the specimens in this study were determined from the stress–strain curves obtained during uniaxial compression testing, representing the slope of the curve within the elastic stage. This slope was obtained by performing linear least-squares fitting on the data points within the elastic range. Physically, it represents the tangent modulus within this interval, characterizing the material’s stiffness during elastic deformation. Furthermore, this study used uniaxial compressive strength (σc) to represent the peak stress of the specimens, which corresponds to the highest point on the stress–strain curve.

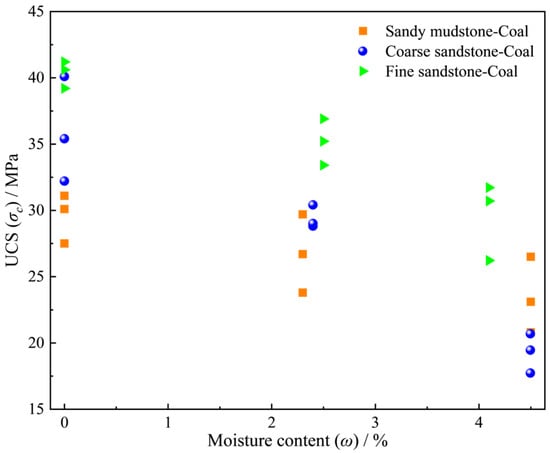

As shown in Figure 5, due to the inherent heterogeneity of the coal–rock mass, the uniaxial compressive strength exhibits certain dispersion across specimen groups even under identical lithology and moisture content conditions. Nevertheless, this inherent variability does not obscure the clear trend of strength degradation with increasing moisture content. To maintain focus on the core research objective and avoid redundancy in data presentation, one representative dataset from each set of replicate tests was selected for subsequent analysis.

Figure 5.

Relationship between unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and moisture content in combined coal–rock of different lithology.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Post-Peak Stress and Deformations of Coal–Rock Combined Body

As shown in Figure 6a, the uniaxial compressive strengths (UCSs) of sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone in their pristine states were 36.84, 36.13, and 64.24 MPa, respectively, all exceeding the compressive strength of pure coal samples (30.1 MPa). The axial compressive strength and elastic modulus of the pure rock samples decreased with increasing water content. For the sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone, the UCS decreased by 63.6%, 69.16%, and 42.52%, respectively, when the moisture content increased from dry to saturated, whereas, the elastic moduli decreased by 42.36%, 60.60%, and 33.72%, respectively. Physicochemical interactions between the water and coal–rock samples diminished their mechanical properties. The water adsorbed within the specimens reacted with the minerals, causing significant alterations in the mechanical parameters. Concurrently, adsorbed water reduced the intermolecular cohesive forces and intermolecular friction, leading to reduced mechanical strength and more pronounced plasticity.

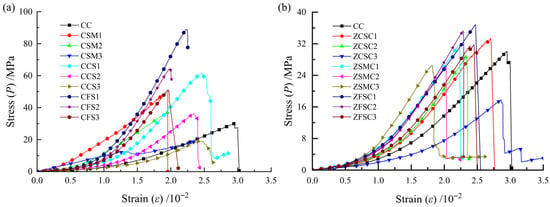

Figure 6.

Stress–strain curves of samples. (a) Pure coal and rock samples; (b) coal–rock combined samples.

As depicted in Figure 6b, the coal–rock composite specimens formed by bonding pure coal and pure rock at a 1:1 height ratio exhibited stress–strain curves similar to those of pure coal and pure rock specimens, which were divided into five stages: consolidation, elastic, microfracture stable fracture development, unstable fracture development, and post-peak stages. Notably, the unstable fracture development and post-peak stages were indistinct in all coal–rock composite specimens. The stress–strain curves exhibited a rapid decline after reaching the uniaxial compressive strength, demonstrating pronounced brittle failure characteristics. The compressive strength of composite specimens was 19.44–40.6 MPa, with elastic moduli of 2.283–2.805 GPa. Evidently, the compressive strength of the composite specimens was closely related to the properties and moisture content of the rock within them.

3.2. Effect of Lithology and Rock Moisture on Mechanical Properties

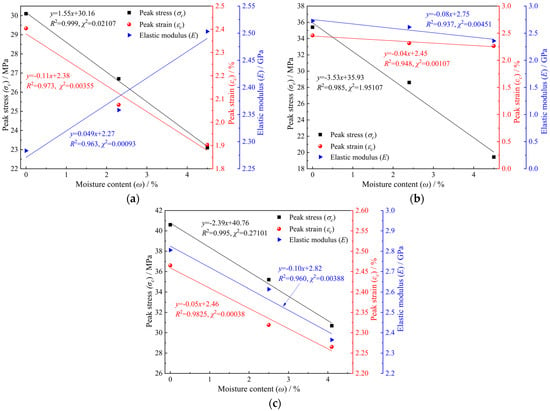

Figure 7 illustrates the variations in mechanical parameters (peak stress, peak strain and elastic moduli) of coal–rock composites with different lithologies relative to rock moisture content. Linear regression analysis of the dataset produced R2 values ranging from 0.937 to 0.999, with χ2 values maintained at low levels (minimum: 0.00038), indicating excellent fitting quality. These results demonstrate a strong correlation between the mechanical properties of coal–rock composites and the moisture content of the rock component. When the rocks were in a dry state, the peak stress (σc) values for the coal–rock composite samples were ranked as follows: fine sandstone–coal (40.6 MPa) > coarse sandstone–coal (35.4 MPa) > sandy mudstone–coal (30.1 MPa). This sequence remains unchanged even when the rock is in a naturally saturated state. However, when the rock was in a saturated water-bearing state, the peak stress (σc) magnitude sequence was: fine sandstone–coal (30.69 MPa) > sandy mudstone–coal (23.1 MPa) > coarse sandstone–coal (19.44 MPa). This pattern in the strength parameters of composite specimens results from the combined effects of the rock’s inherent mechanical strength and the rock–coal interface interaction: from a rock strength perspective, fine sandstone (high quartz content, dense cementation) > coarse sandstone (coarse-grained) > sandy mudstone (rich in weak clay minerals). Consequently, the strengths of the dry and naturally saturated composite specimens were largely consistent. However, under saturated conditions, water exerts a less pronounced weakening effect on the mechanical properties of sandy mudstone than on coarse sandstone. This phenomenon may be attributed to the physicochemical interactions (constrained lattice expansion) within the clay mineral-rich sandy mudstone upon water saturation, which locally fill micro-fractures and compact intergranular voids. Composite failure typically occurs at the weakest structural point from the perspective of rock–coal interface behavior. Fine sandstone, which is dense and rigid, forms a tight mechanical interlock and provides effective contact with coal. Coarse sandstone, with its larger grains, is prone to fragmentation at the interface as loading progresses. Silty mudstone, possessing a relatively soft and smooth surface, relies more on the limited mechanical interlocking with coal, making it comparatively susceptible to slip failure.

Figure 7.

Comparison of mechanical parameters for composite specimens under different moisture content. (a) Sandy mudstone–coal composite specimen. (b) Coarse sandstone–coal composite specimen. (c) Fine sandstone–coal composite specimen.

For both the coarse sandstone–coal and fine sandstone–coal composite specimens, the peak stress (σc), peak strain (εc), and elastic modulus (E) decreased with increasing rock moisture content under different water-bearing states. Specifically, when the coarse and fine sandstones transitioned from dry to saturated conditions, the peak stresses (σc), peak strains (εc), and elastic moduli (E) of the coal–rock composite decreased by 45%, 21.8%, and 13.5%, respectively; for fine sandstone–coal composites, these values decreased by 24.4%, 8.1%, and 15.7%, respectively. Similarly, the peak stress (σc) and peak strain (εc) of the sandy mudstone–coal composite specimens decreased with increasing moisture content of the sandy mudstone. When the sandy mudstone transitioned from a dry to a saturated state, the peak stress (σc) and peak strain (εc) of the composite specimen decreased by 23.3% and 20.8%, respectively, whereas the elastic modulus increased by 9.6%.

3.3. Effect of Rock Moisture on Microcracks and Macro-Failure Patterns

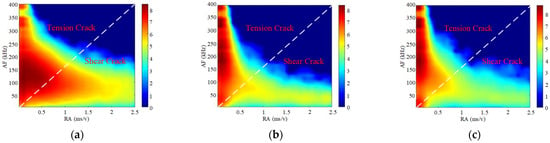

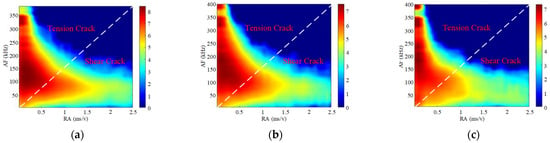

The rise in time-to-amplitude ratio (RA) and average frequency (AF) values in the AE monitoring data can be utilized to distinguish crack types within the coal rock. Here, RA (ms/v) denotes the ratio of the rise time to amplitude, while AF (kHz) represents the ratio of the impact count to the duration. Research indicates that shear fractures within coal–rock materials typically manifest as sonic emission signals with low AF and high RA values, whereas tensile fractures exhibit the opposite characteristics [24,48]. Based on the experimental AE monitoring results, density contour plots of the RA–AF relationship for coal–rock composite specimens with varying lithologies and moisture content are presented in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. Using the 45° axis as the boundary, the density contour plots were divided into a tensile fracture zone on the left and a shear fracture zone on the right. Within these plots, the color gradient from blue to red indicates the data density ranging from sparse to dense, with deep red denoting maximum data density and deep blue indicating zero density. Data signals near the boundary line represent the mixed tension–shear crack zone within the specimen.

Figure 8.

RA–AF test specimen and failure mode of sandy mudstone–coal composite (ω represents the moisture content of rock in composite specimens). (a) Dry state (ω = 0). (b) Natural state (ω = 2.3%). (c) Saturated state (ω = 4.5%).

Figure 9.

RA–AF specimen and failure mode of coarse sandstone–coal composite (ω is the moisture content of the specimen). (a) Dry state (ω = 0). (b) Natural state (ω = 2.4%). (c) Saturated state (ω = 4.5%).

Figure 10.

RA–AF specimen and failure mode of fine sandstone–coal composite (ω is the moisture content of the specimen). (a) Dry state (ω = 0). (b) Natural state (ω = 2.5%). (c) Saturated state (ω = 4.1%).

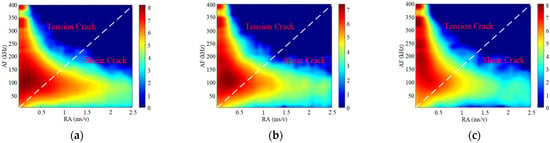

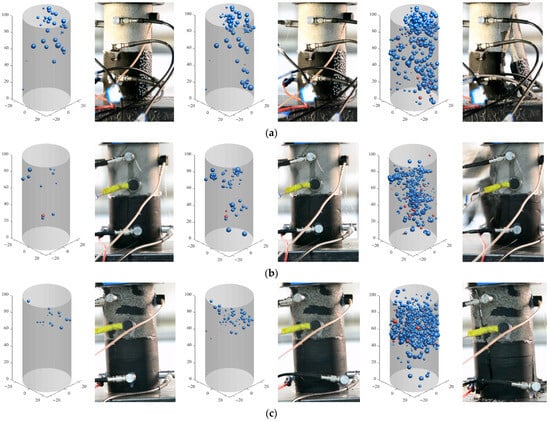

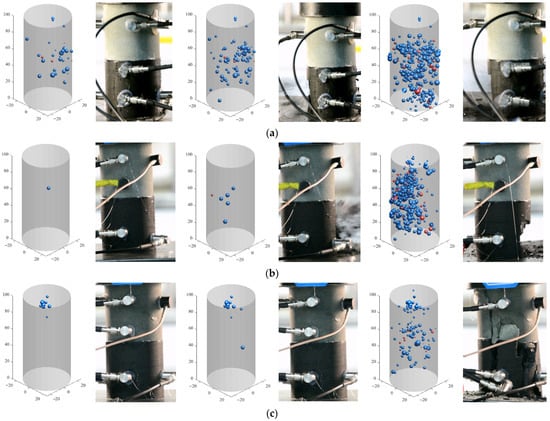

Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 indicate that under uniaxial loading, the AF values of the coal–rock composite specimens ranged from 0 to 400 kHz, while the RA values ranged from 0 to 2.5 ms/v. The data distribution within the tensile fracture zone exhibited relatively broad variability. The RA–AF relationship density plots for specimens of different lithology and moisture content all exhibited high data density in the tensile fracture zone near the vertical axis (AF value), whereas data density in the shear fracture zone near the horizontal axis (RA value) was low. As summarized in Table 4, under identical lithological conditions, the proportion of shear fracture decreases and that of tensile fracture increases with rising rock moisture content. These observations collectively indicate that under uniaxial compression, tensile failure predominates in specimens with different lithologies and moisture content. Dry rock, which possesses greater cohesive strength, generated numerous AE events during uniaxial loading, resulting in high RA and AF data densities with broad distribution ranges.

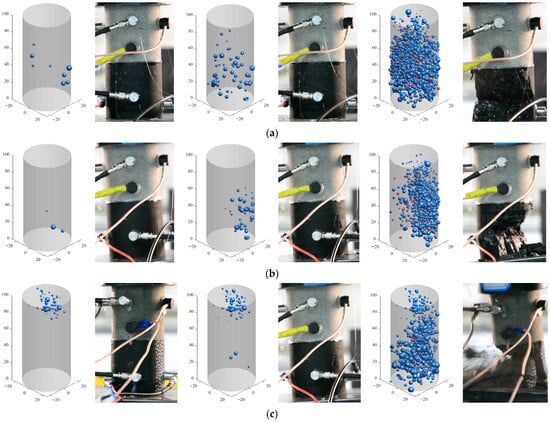

Figure 11.

Spatial distribution of AE events in sandy mudstone–coal composite specimens with different moisture content. (a) Dry state. (b) Natural moisture content. (c) Saturated.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of AE events in coarse sandstone–coal composite specimens with different moisture content. (a) Dry state. (b) Natural moisture content. (c) Saturated.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of AE events in fine sandstone–coal composite specimens with different moisture content. (a) Dry state. (b) Natural moisture content. (c) Saturated.

Table 4.

Effect of moisture content on the failure modes of coal–rock composites.

As the moisture content increased, the number of various fracture types within the composite decreased, and their distribution was concentrated toward the vertical axis. To more intuitively analyze the evolution patterns of damage-fracturing and microfracture spatial distribution across different stages before peak load is reached in water-bearing coal-rock composite specimens, the spatial development characteristics of fracture zones at locations 0.3σc, 0.6σc, and σc were investigated based on AE event localization results. The corresponding results are presented in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, which are arranged left to right in order of increasing stress levels and include physical photographs of the specimens at each stress stage. The fracture locations within the specimen are represented by spheres, with the sphere size and color denoting the energy released during fracture initiation. Different colors are used to distinguish between the fracture types: blue indicates tensile fracture events, and red indicates shear fracture events.

Figure 11 illustrates the spatiotemporal evolution of AE events in the sandy mudstone–coal composite specimens with varying moisture content. Upon reaching a loading stress of 0.3σc, the sandy shale–coal composite specimens exhibit minor low-energy tensile fractures near coal–rock interfaces or within strata. Under dry, naturally moist, and saturated conditions, coal-derived AE events constituted 13.89%, 25.00%, and 0% of the total events, respectively. As loading stress increased from 0.3σc to 0.6σc, both the quantity and energy level of AE events within the composite specimen increased slightly, with tensile fractures in coal remaining predominant. As the water content increased, the fracture locations gradually shifted toward and concentrated on sandy mudstone, particularly in the saturated state, where fractures predominantly occurred within this component. This indicates the severe mechanical degradation of sandy mudstone under hydrogeological action, rendering it the primary medium for fracture development within the composite. Upon reaching the loading stress level of σc, AE events increased rapidly, predominantly exhibiting shear fracture signals. Under dry, naturally moist, and saturated conditions, coal-derived AE events accounted for 32.61%, 25.94%, and 17.42% of the total events, respectively. The composite specimen failed through a combined tensile–shear mode characterized by overall tensile cracking.

Figure 12 illustrates the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the AE events in the coarse sandstone–coal composite specimens with varying moisture content. When the applied stress level reached 0.3σc, and minor low-energy tensile fractures occurred near the coal–rock interface or within the rock layers of the composite specimens. Under dry, naturally moist, and saturated conditions, the AE events originating from coal accounted for 63.64%, 100%, and 0% of the total events, respectively. As the applied stress level increased from 0.3σc to 0.6σc, both the number and energy levels of AE events within the composite specimens rose slightly, with tensile fractures in the coal still predominating. Furthermore, as the moisture content increased and fracture locations gradually concentrated toward the coarse sandstone portion. This phenomenon is caused by the closure, compression, and sliding of microfractures within the rock under the influence of water. Upon reaching σc, AE events surged, with both the energy levels and quantity of shear fracture signals markedly increasing. Under dry, naturally moist, and saturated conditions, the coal-derived AE events constituted 64.07%, 40.23%, and 36.67% of the total events within the composite specimen, respectively. The composite specimen exhibited failure in a combined tensile–shear mode dominated by overall tensile cracking, although the degree of damage to the coal was relatively high.

Figure 13 illustrates the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of the AE events in fine sandstone–coal composite specimens with different moisture content. When the applied stress level reached 30% of σc, the fine sandstone–coal composite specimen exhibited a small number of low-energy tensile fractures. When the fine sandstone was in dry, naturally moist, and saturated states, the AE events originating from the coal within the composite accounted for 77.78%, 100%, and 0% of the total events, respectively. As the applied stress level increased from 0.3σc to 0.6σc, the number and energy level of AE events within the composite specimen rose slightly. With increasing moisture content, the fracture locations gradually became concentrated in the upper fine sandstone sections. However, owing to the superior mechanical properties of fine sandstone compared with coal, fractures predominantly occurred within the coal body. Upon reaching σc, the number of AE events increased rapidly to a maximum, with both the energy level and quantity of shear fracture signals markedly increasing. Under dry, naturally moist, and saturated conditions, the AE events in the coal within the composite specimen accounted for 56.97%, 51.76%, and 57.22% of the total events, respectively. The composite specimens failed in the coal tensile mode.

The three-dimensional spatial localization results of AE events provides direct evidence for understanding the failure mechanism of the composite specimens. During the initial loading phase (0.3σc), fracture events within the composite specimens were relatively infrequent and exhibited a random, dispersed distribution. Upon reaching 0.6σc, fracture events began to increase significantly, exhibiting pronounced spatial distribution variations attributable to differing coal–rock properties within the composite. With further loading, fracture events became increasingly concentrated and internal cracks progressively propagated toward the specimen surface, ultimately coalescing to form a dominant macroscopic fracture plane.

The spatial distribution heterogeneity of fracture events within the composite specimens is primarily associated with lithology and their water-bearing state. For weak sandy mudstone–coal assemblies, fracture events primarily occur within the sandy mudstone fraction, particularly evident under saturated conditions, indicating that sandy mudstone may be the primary failure medium under such states. For the relatively hard, coarse sandstone–coal and fine sandstone–coal composite specimens, fracturing events predominantly occurred within the coal. Although the coarse and fine sandstones exhibited minor fracturing signals during the initial loading phase under saturated conditions, the composite specimens still experienced overall failure due to the rapid development of cracks within the coal. Photographic evidence from the combined specimen failures indicates that the failure modes correlate with both rock properties and moisture content. Specifically, as the moisture content increased, the ultimate failure mode transitioned from shear failure within the coal body to tensile failure of the entire combined body.

3.4. Effect of Rock Moisture on Energy Evolution of Coal–Rock Combined Body

Moisture content plays a significant role in the energy evolution characteristics of coal (rock) specimens [49]. Studies [44,50] have shown that the energy storage capacity of coal–rock deteriorates markedly with increasing moisture content. Therefore, investigating how moisture content affects the energy evolution of coal–rock composites under uniaxial compression is essential for deciphering their macroscopic failure mechanisms.

The deformation process of coal–rock specimens under external loading constitutes a cycle of energy absorption and conversion. Apart from being transformed into releasable elastic strain energy and energy dissipated by damage, a small portion of the input energy is consumed through friction and thermal radiation. For practical computational purposes, these negligible quantities of energy losses (friction and thermal radiation) are frequently disregarded [51]. Consequently, the experimental system can be reasonably simplified as a closed system without heat exchange with the external environment. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the work done by the external force is entirely converted into recoverable elastic strain energy stored during deformation and dissipated energy consumed [52], expressed as:

where U is the energy generated by the work done by external forces, Ue is the releasable elastic strain energy, and Ud is the energy dissipated during the deformation, and failure of the coal-rock specimen.

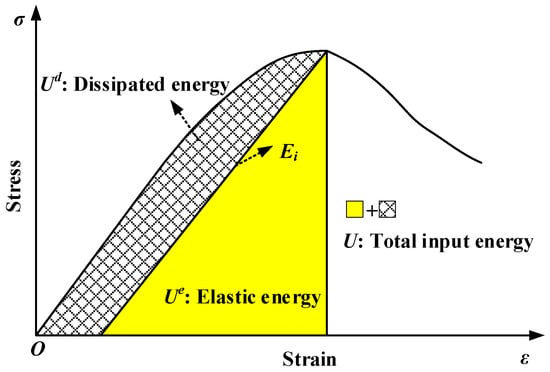

The relationship between the releasable elastic strain energy Ue and the dissipated energy Ud is illustrated in Figure 14. The yellow area represents the releasable elastic strain energy, Ue, which corresponds to the elastic strain energy released per unit volume of rock upon unloading. The area enclosed by the stress–strain curve and the unloading elastic modulus Ei represents the dissipated energy Ud.

Figure 14.

Energy relationship during deformation of coal rock specimens under loading [33].

It should be noted that the unloading curve in Figure 13 is simplified as a linear segment, whereas actual unloading processes typically exhibit nonlinear responses. Tomiczek, K. [53] indicates that the unloading modulus Ei should be calculated based on the tangent modulus at 0.8σc. However, during testing, to prevent potential impact damage to the equipment resulting from sudden specimen failure, the system was programmed to automatically terminate loading once the strain rate exceeded a predefined threshold. Consequently, complete unloading curves were not obtained, preventing direct determination of the unloading elastic modulus Ei. Thus, this study adopted the initial elastic modulus E as a substitute for Ei in calculating elastic parameters. This substitution approach has been validated in previous studies [54,55].

Under triaxial stress loading conditions, the strain energy of various sections within the coal–rock specimen can be expressed in the principal stress space as follows:

where and represent the average unloading elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the composite, respectively. Owing to the heterogeneity between coal and rock, it is difficult to precisely define the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the coal–rock composite. For practical computational purposes, a simplified approach was adopted in which the initial elastic modulus E and Poisson’s ratio ν obtained from uniaxial compression tests were used to approximate and , respectively.

In this study, the triaxial stress state of underground coal pillar dams was simplified to a uniaxial stress condition to investigate damage deformation under axial stress, i.e., σ2 = σ3 = 0. Equation (3) can be simplified as:

Using Equations (1) and (4), the uniaxial compression test data for the coal–rock composite specimens under varying moisture conditions were processed to calculate the total input energy U, elastic strain energy Ue, and dissipated energy Ud during the loading process.

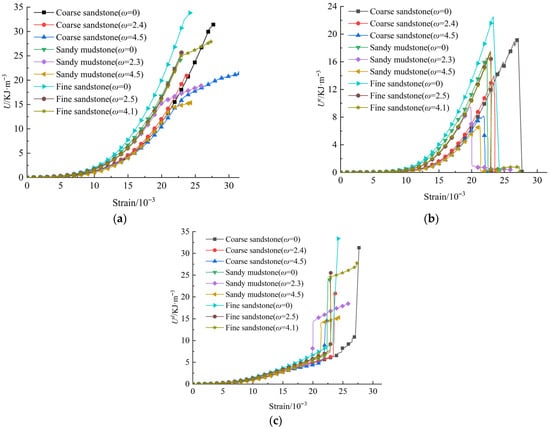

Figure 15 shows the values of U, Ue, and Ud for coal–rock combinations with different lithologies and moisture content. The total input, elastic strain, and dissipated energies at the peak point are denoted UA, UAe, and UAd, respectively (Table 5). U and Ud increased with strain, initially at a modest rate before rapidly accelerating to peak values at the maximum stress. The releasable elastic strain energy Ue first increased and then decreased with strain, peaking at the maximum stress. Owing to the initial compaction process during loading, the applied stress on the coal–rock composite specimen did not rapidly increase with deformation during this period. Consequently, the dissipated energy curve increased earlier than the elastic strain energy curve. The deformation of the coal–rock composite specimen involves both rock and coal components, and changes in the moisture content significantly influence the deformation at each stage, thereby affecting the energy evolution. As shown in Table 3, under identical moisture conditions (dry state), the fine sandstone–coal composite specimens exhibited the highest total energy and elastic strain energy at peak values, amounting to 32.02 and 22.49 kJ/m3, respectively. These values exceeded those of the coarse sandstone–coal composite specimens by 5.4% and 15.87% and were 35.79% and 35.89% higher than those of the sandy mudstone–coal composite specimens. However, the dissipated energy showed little difference (peak dissipated energies for fine sandstone–coal, coarse sandstone–coal, and sandy mudstone–coal were 9.53, 7.03, and 10.97 kJ/m3, respectively).

Figure 15.

Variation curves of total energy, elastic strain energy, and dissipated energy for coal–rock composite specimens under different lithologies and moisture conditions. (a) U. (b) Ue. (c) Ud.

Table 5.

Results of total energy, elastic strain energy, and dissipated energy of coal–rock combination sample at overall peak value.

Under identical lithological conditions, the UA, UAe, and UAd values at peak load generally decrease as the moisture content increases. Taking the fine sandstone–coal composite specimens as an example, when the fine sandstone transitioned from dry to saturated moisture conditions, the composite’s UA, UAe, and UAd values at the peak load decreased by 22.92%, 22.85%, and 23.08%, respectively. However, for the sandy mudstone–coal composite specimens, the UAd value at saturation exceeded that at natural moisture content. The analysis suggested that the increased moisture content substantially reduced the strength of the sandy mudstone. Consequently, the influence of sandy mudstone on the overall failure of the composite specimen increased rather than decreased, leading to heightened energy dissipation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Applicability of the RA–AF Analysis Method for Coal–Rock Composites

Previous studies have confirmed the feasibility of using the RA–AF analysis method to distinguish between tensile and shear fractures during the failure process of coal–rock composites [48]. However, as an empirical criterion, the identification accuracy of this method is heavily dependent on sensor type, arrangement, wave propagation path, and the material properties of the specimen. Due to the inherent material heterogeneity of coal–rock composites, acoustic waves propagating inside the composite specimen (particularly at coal–rock interfaces) undergo varying degrees of attenuation and reflection, which may introduce uncertainty in the accuracy of acoustic emission localization. Therefore, it is necessary to incorporate the macroscopic post-failure morphology of the specimens as supplementary validation for the reliability of the RA–AF analysis method applied in this study.

According to relevant studies [56], crack types can be distinguished based on fracture orientation and the movement of adjacent blocks: when a fracture is aligned parallel to the loading direction and the blocks on both sides separate perpendicularly to the fracture plane, it is identified as a tensile fracture, and when a fracture is inclined and tangential sliding occurs along the fracture surface, it is classified as a shear fracture. As indicated in Section 3.3 of this paper, under uniaxial compression, tensile fractures dominate the internal cracking in all specimens. This conclusion can be further validated by the failure patterns shown in Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12. The post-failure specimens exhibit a typical tensile–shear composite failure mode, with tensile mechanisms being predominant. This observation aligns with the previously stated conclusion that “tensile failure dominates,” thereby supporting the feasibility of using the RA–AF analysis method for fracture-type discrimination in this study.

4.2. Limitations and Prospects

While this study provides a preliminary investigation into the effects of moisture content on the mechanical properties and energy dissipation characteristics of coal–rock composites, the factors influencing the failure mechanisms of these composites warrant further investigation. These primarily encompass the following areas.

- (1)

- Insufficient investigation of coal–rock interface characteristics. The mechanical behavior of coal–rock composites is neither a simple superposition of the individual mechanical properties of coal and rock nor solely governed by either constituent. Instead, it represents a complex systemic response determined collectively by the intrinsic strength of the rock, interfacial effects, and water–rock interactions. As a vulnerable region within coal–rock composites, the idealized single contact surface in laboratory settings differs somewhat from the coal–rock interfaces encountered at engineering scales. Current bonding methods for coal–rock composites primarily include AB adhesive [37,57] and direct contact [32]. Existing studies indicate that the choice of bonding method significantly influences the failure characteristics of coal–rock composites, particularly near the coal–rock interface [58], which poses challenges for accurately studying the influence of rock moisture content on microcrack development and failure modes in coal–rock composites using acoustic emission techniques, as undertaken in this study. Although the interfacial effects in coal–rock composites were not analyzed in depth in this research, the consistency between the RA–AF-based classification and the macroscopic failure morphology still supports the reliability of the conclusions drawn. Further investigation into coal–rock interface characteristics is crucial for clarifying the failure mechanisms of coal–rock composites and will be one of the key focuses of our subsequent research.

- (2)

- Inadequate investigation into the weakening effects of immersion time on the mechanical properties of coal–rock composites. While this study focused on the influence of moisture content on the mechanical characteristics and energy dissipation behavior of coal–rock composites, it does not account for time-dependent effects. However, under actual engineering conditions, coal pillar dams are subjected to long-term seepage-stress coupling environments, where the deterioration of mechanical performance and overall stability represents a progressive process. Previous research has demonstrated that under prolonged water immersion, the mechanical parameters of coal–rock specimens (including strength, elastic modulus, cohesion, and internal friction angle) continuously decrease with extended immersion duration, exhibiting significant time-dependent deterioration [24,59]. Therefore, future research should integrate mechanical testing with multi-field coupled numerical simulations to thoroughly investigate the instability mechanisms of coal pillar dams under long-term water immersion, thereby improving the evaluation methods and control strategies for their long-term stability.

5. Conclusions

In this study, uniaxial compression tests were conducted on individual coal–rock specimens and composite specimens with varying moisture content. The tests identified the degradation characteristics of the mechanical properties of individual coal–rock specimens under different moisture conditions and investigated the influence of rock properties and moisture state within composite specimens on their mechanical behavior and energy characteristics. The research findings led to the following conclusions.

- (1)

- The water immersion test results indicated that the moisture content (ω) of coal rock specimens increased logarithmically with immersion duration (R2 > 0.94, χ2 < 0.13), progressing through three distinct phases: rapid, gradual, and stable. The uniaxial loading tests revealed that both the UCS and E of the coal rock specimens decreased linearly with increasing moisture content. For sandy mudstone, coarse sandstone, and fine sandstone, the UCS decreased by 63.6%, 69.16%, and 42.52%, respectively, when the moisture content increased from dry to saturated, while the elastic modulus decreased by 42.36%, 60.60%, and 33.72%, respectively.

- (2)

- When the rocks within the composite specimens possess identical moisture conditions, a greater rock strength correlates with increased specimen strength and strain. Under identical lithological conditions, as the rock moisture content increases, the peak stress, peak strain, and elastic modulus of the composite specimens decrease proportionally. This trend was most pronounced in the coarse sandstone–coal composite specimens. When the coarse sandstone transitioned from a dry to a saturated state, the peak stress, peak strain, and elastic modulus of the coal–rock composite specimens decreased by 45%, 21.8%, and 13.5%, respectively.

- (3)

- The AE monitoring results indicated that the AE events within the coal–rock composite specimens under uniaxial loading conditions exhibited distinct spatial distributions. As the applied stress level increased from 30% to 85% of the uniaxial compressive strength, both the number and energy levels of the AE events within the composite specimens increased slightly. Tensile fracture remained predominant within the coal layer, with fracture locations becoming progressively concentrated in the upper rock portion as the rock moisture content increased. As the rock moisture content increased, the ultimate failure mode of the composite specimens shifted from shear failure within the coal matrix to tensile failure of the entire composite structure.

- (4)

- The properties of the rock and its moisture content significantly influenced the energy absorption and conversion of the composite specimens during loading. Under similar moisture conditions, the fine sandstone–coal composite specimens exhibited the highest total energy U and elastic strain energy Ue at peak load, although the dissipated energy remained relatively similar. Under identical lithological conditions, the peak values of U, Ue, and Ud for the composite specimens decreased as the rock moisture content increased, demonstrating aqueous weakening of energy dissipation characteristics and consequently uncovering the intrinsic mechanism governing macroscopic mechanical deterioration from an energy perspective.

Author Contributions

Y.F.: experimental investigation, analysis, methodology, writing—original draft. Q.X.: writing—review and editing, supervision, data curation. Z.X.: conceptualization, methodology. C.Z.: experimental investigation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52404153) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20241649).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Shengyan Chen and Zhisen Zhang for their valuable assistance in the writing—review and editing stage of this manuscript. Their insightful comments and constructive suggestions greatly improved the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, H.Q.; Xu, J.J.; Fang, J.; Cao, Z.G.; Yang, L.Z.; Li, T.X. Potential for mine water disposal in coal seam goaf: Investigation of storage coefficients in the Shendong mining area. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, F.; Xing, Z.; Wang, L.C. Impacts of Underground Reservoir Site Selection and Water Storage on the Groundwater Flow System in a Mining Area-A Case Study of Daliuta Mine. Water 2022, 14, 3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.S.; Yang, W.; Shan, R.L.; Wang, S.; Fang, J. Ultimate water level and deformation failures of the artificial dam in the coal mine underground reservoir. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 162, 108367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasantha, P.L.P.; Ranjith, P.G. The Taguchi approach to the evaluation of the influence of different testing conditions on the mechanical properties of rock. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ferrari, A.; Ewy, R.; Duranti, L.; Laloui, L. Impact of Water Saturation on the Anisotropic Elastic Moduli of a Gas Shale. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 4645–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabat, Á.; Tomás, R.; Cano, M. Advances in the understanding of the role of degree of saturation and water distribution in mechanical behaviour of calcarenites using magnetic resonance imaging technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 303, 124420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypkowski, K.; Zagórski, K.; Zagórska, A. Determination of the Extent of the Rock Destruction Zones around a Gasification Channel on the Basis of Strength Tests of Sandstone and Claystone Samples Heated at High Temperatures up to 1200 °C and Exposed to Water. Energies 2021, 14, 6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, A.; Arman, H.; Yagiz, S.; Abdelghany, O.; Amin, B.M.; Ahmed, A.; Paramban, S.; Saima, M.A. Strength characterization of limestone lithofacies under different moisture states. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yao, Q.L.; Wang, F.R.; Xiao, L.; Ma, J.Q.; Kong, F.L.; Shang, X.B. Tracer Test Method to Confirm Hydraulic Connectivity Between Goafs in a Coal Mine. Mine Water Environ. 2024, 43, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Zhao, X.D.; Han, Z.; Ji, Y.; Qiao, Z.J. Reasonable Size Design and Influencing Factors Analysis of the Coal Pillar Dam of an Underground Reservoir in Daliuta Mine. Processes 2023, 11, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, K.; Gao, Y.; Qi, Z.; Cai, M. Influence of Water Immersion on Coal Rocks and Failure Patterns of Underground Coal Pillars Considering Strength Reduction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.P.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhou, H.Y.; Yi, C.; Chen, Z.J. Study on Two-Body Mechanical Model Based on interaction Between Structural Body and Geo-Body. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 1457–1464. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dou, L.M.; Lu, C.P.; Mu, Z.L.; Zhang, X.T.; Li, Z.H. Rock burst tendency of coal-rock combinations sample. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2006, 23, 43–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.L.; Liu, X.S.; Shen, B.; Ning, J.G.; Gu, Q.H. New approaches to testing and evaluating the impact capability of coal seam with hard roof and/or floor in coal mines. Geomech. Eng. 2018, 14, 367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Yang, K.; He, X.; Chi, X.L.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zhang, J.Q. Mechanical Characteristics and Energy Dissipation Trends of Coal-Rock Combination System Samples with Different Inclination Angles under Uniaxial Compression. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 7702751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Q.; Zuo, J.P.; Liu, H.Y.; Zuo, S.H. The strength characteristics and progressive failure mechanism of soft rock-coal combination samples with consideration given to interface effects. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 138, 104593. [Google Scholar]

- Chajed, S.; Singh, A. Acoustic Emission (AE) Based Damage Quantification and Its Relation with AE-Based Micromechanical Coupled Damage Plasticity Model for Intact Rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 2581–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, S.Q.; Liu, Z.L.; Sun, B.W.; Yang, J.; Xu, J. Study on mechanical properties and deformation of coal specimens under different confining pressure and strain rate. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 118, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.Z.; Chi, X.L.; Liu, W.J.; Wang, C.C.; Wu, X.H. Mechanical properties and energy migration mechanisms of coal-rock composite with different height ratios under gas-containing conditions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 7996–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.P.; Wang, Z.F.; Zhou, H.W.; Pei, J.L.; Liu, J.F. Failure behavior of a rock-coal-rock combined body with a weak coal interlayer. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2013, 23, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.M.; Song, D.Z.; Li, Z.H.; Liu, B.B.; Liu, J. Research on AE and EMR response law of the driving face passing through the fault. Saf. Sci. 2019, 17, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Liu, X.S.; Tan, Y.L.; Ma, Q.; Wu, B.Y.; Wang, H.L. Creep Constitutive Model and Numerical Realization of Coal-Rock Combination Deteriorated by Immersion. Minerals 2022, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yao, Q.L.; Wei, F.; Chong, Z.H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, C.B.; Li, J. Effects of water intrusion and loading rate on mechanical properties of and crack propagation in coal–rock combinations. J. Cent. South Univ. 2017, 24, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.B.; Tang, W.; Chen, S.J.; Wang, E.Y.; Wang, C.T.; Li, T.; Zhang, G.H. Damage Effect and Deterioration Mechanism of Mechanical Properties of Fractured Coal-Rock Combined Body Under Water-Rock Interaction. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 513–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.N.; Chi, X.L.; Yang, K.; Lyu, X.; Fu, Q.; Wang, Y. Water-bearing effect on mechanical properties and interface failure mode of coal-rock combination samples. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2023, 41, 1252–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.F.; Chen, X.H.; Chen, G.B.; Qiu, L. Experimental study on dynamic mechanical responses of coal specimens under the combined dynamic-static loading. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.B.; Li, Q.; Zhang, G.H.; Teng, P.C.; Gong, B. Energy Distribution Law of Dynamic Failure of Coal-Rock Combined Body. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 6695935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.Y.; Dou, L.M.; Luo, X.; Zheng, Y.D.; Huang, J.L.; Andrew, K. Seismic effort of blasting wave transmitted in coal-rock mass associated with mining operation. J. Cent. South Univ. 2012, 19, 2604–2610. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.P.; Chen, Y.; Song, H.Q. Study progress of failure behaviors and nonlinear model of dee pcoal-rock combined body. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2021, 52, 2510–2521. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.S.; Tan, Y.L.; Ning, J.G.; Lu, Y.W.; Gu, Q.H. Mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of coal in coal-rock combined body. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 11, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, C.P.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, H.Y. Numerical investigation on crack development and energy evolution of stressed coal-rock combination. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2020, 133, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.B.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Fu, Q.; Li, Q.X. Mechanical Damage Characteristics and Energy Evolution Laws of Primary Coal-Rock Combinations with Different Coal-Rock Ratios. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.J.; Liu, J.J.; Yang, Y.T.; Wang, P.D.; Wang, Z.M.; Song, Z.Y.; Liu, J.M.; Zhao, S.Q. Failure energy evolution of coal-rock combination with different inclinations. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Jin, Q.; Li, S.; Lin, H.; Zhou, R.; Lei, W.; Ma, X.; Yuan, X. Evolution of static fracture mechanics and energy dissipation characteristics of composites based on different interface angles. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.Y.; Zhang, D.X.; Zhao, T.B.; Li, Y.R.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Wang, C.W.; Wu, W.B. Influence of Rock Strength on the Mechanical Characteristics and Energy Evolution Law of Gypsum-Rock Combination Specimen under Cyclic Loading-Unloading Condition. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Q.P.; Wang, X.R.; Wang, Z.Q.; Lu, S.Q.; Sa, Z.Y.; Wang, H. Dynamic multifractal characteristics of acoustic emission about composite coal-rock samples with different strength rock. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 164, 112725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yin, D.W.; Wang, F.; Jiang, N.; Li, X.L. Effects of combination mode on mechanical properties of bi-material samples consisting of rock and coal. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 2156–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.S.; He, X.Q.; Zhu, C.W. Study on mechanical property and electromagnetic emission during the fracture process of combined coal-rock. Proc. Earth Planet Sci. 2009, 1, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.M.; Zuo, J.P.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, R.S. Research on strength and failure mechanism of deep coal-rock combination bodies of different inclined angles. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 1332–1339. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Jiang, Y.D.; Zhan, S.J.; Wang, C. Frictional sliding tests on combined coal-rock samples. J. Rock Mech. Geotechnol. Eng. 2014, 6, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.B.; Gu, X.B.; Guo, W.Y.; Gong, X.F.; Xiao, Y.X.; Kong, B.; Zhang, C.G. Influence of rock strength on the mechanical behavior and P-velocity evolution of coal-rock combination specimen. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tan, Y.L.; Liu, X.S.; Gu, Q.H.; Li, X.B. Effect of coal thicknesses on energy evolution characteristics of roof rock-coal-floor rock sandwich composite structure and its damage constitutive model. Compos. Part B 2020, 198, 108086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.W.; Chen, S.J.; Chen, B.; Xia, Z.G. Simulation Study on Strength and Failure Characteristics of Coal-Rock Composite Sample with Coal Persistent Joint. Arch. Min. Sci. 2019, 64, 609. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L.; Zuo, J.P.; Liu, D.J.; Wang, Z.B. Deformation failure characteristics of coal-rock combined body under uniaxial compression: Experimental and numerical investigations. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 3449–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, G.B.; Li, Q.H.; Cao, B.; Li, Y.H. The Effect of Crack Characteristics on The Mechanical Properties and Energy Characteristics of Coal-Rock Composite Structure. Acta Geodyn. Geomater. 2022, 19, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.Q.; Yao, Q.L.; Chong, Z.H.; Li, Y.H.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Z.C. Experimental study on the moisture migration and triaxial mechanical damage mechanisms of water-bearing coal samples. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 160, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yao, Q.L.; Yu, L.Q.; Zhu, L.; Chong, Z.H.; Li, Y.H.; Li, X.H. Mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of coal specimen with different moisture under uniaxial loading. Rock Soil Mech. 2023, 32, 462–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.L.; Chen, T.; Tang, C.J.; Majid, S.; Wang, S.W.; Huang, Q.X. Influence of moisture on crack propagation in coal and its failure modes. Eng. Geol. 2019, 258, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ju, F.; Xu, J.; Yan, C.S.; Xiao, M.; Ning, P.; Wang, T.F.; Si, L.; Wang, Y.B. Effects of Moisture Content and Loading Rate on Coal Samples: Mechanical Properties and Failure Mechanisms. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 2025, 58, 3391–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, J.C.; Si, X.F.; Wu, W.X.; Li, S.P. Failure characteristics and energy properties of red sandstone under uniaxial compression: Water content effect and its application. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Cai, M.F. Energy evolution mechanism and failure criteria of jointed surrounding rockunder uniaxial compression. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.Q.; Li, C.B.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M.; Gao, M.Z.; Zhang, Z.T.; Zhang, Z.P.; Li, R.; Xie, J. Energy evolution of coal at different depths under unloading conditions. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 4637–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiczek, K. Researches on the ability of rocks to accumulate elastic energy and rock bursting. Part I. Coefficients of the ability of rocks to accumulate elastic energy WE and rock bursting PES. Min. Tunn. Constr. 2011, 17, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.P.; Ju, Y.; Li, Y.L. Criteria for strength and structural failure of rocks based on energy dissipation and energy release principles. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 17, 3003–3010. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, J.C.; Si, X.F.; Lin, F.; Wu, W.X. An energy-based method for uniaxially compressed rocks and its implication. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.Q.; Stead, D.; Elmo, D. Numerical simulation of microstructure of brittle rock using a grain-breakable distinct element grain-based model. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 78, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.X.; Wang, G.Q.; Li, F.; Tang, Y.J.; Yuan, M.Q. Study on the characteristics of acoustic-thermal precursors of destabilization damage in coal-rock combination bodies with different proportions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25661. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.B.; Wang, C.Y.; Tian, Z.C.; Li, T.; Wang, E.Y.; Gao, N.; Xu, Z.R.; Zhang, G.H.; Chen, W.; Shang, J.X. Review on the Research Progress of Dynamic Failure Response of Coal-Rock Combined Body. Mital Mine 2024, 12, 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H.J.; Zhang, H.M.; Zhang, J.F. Research on Damage Mechanism and Mechanical Characteristics of Coal Rock under Water Immersion. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).