G-S-M-E: A Prior Biological Knowledge-Based Pattern Detection and Enrichment Framework for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sets and Preprocessing

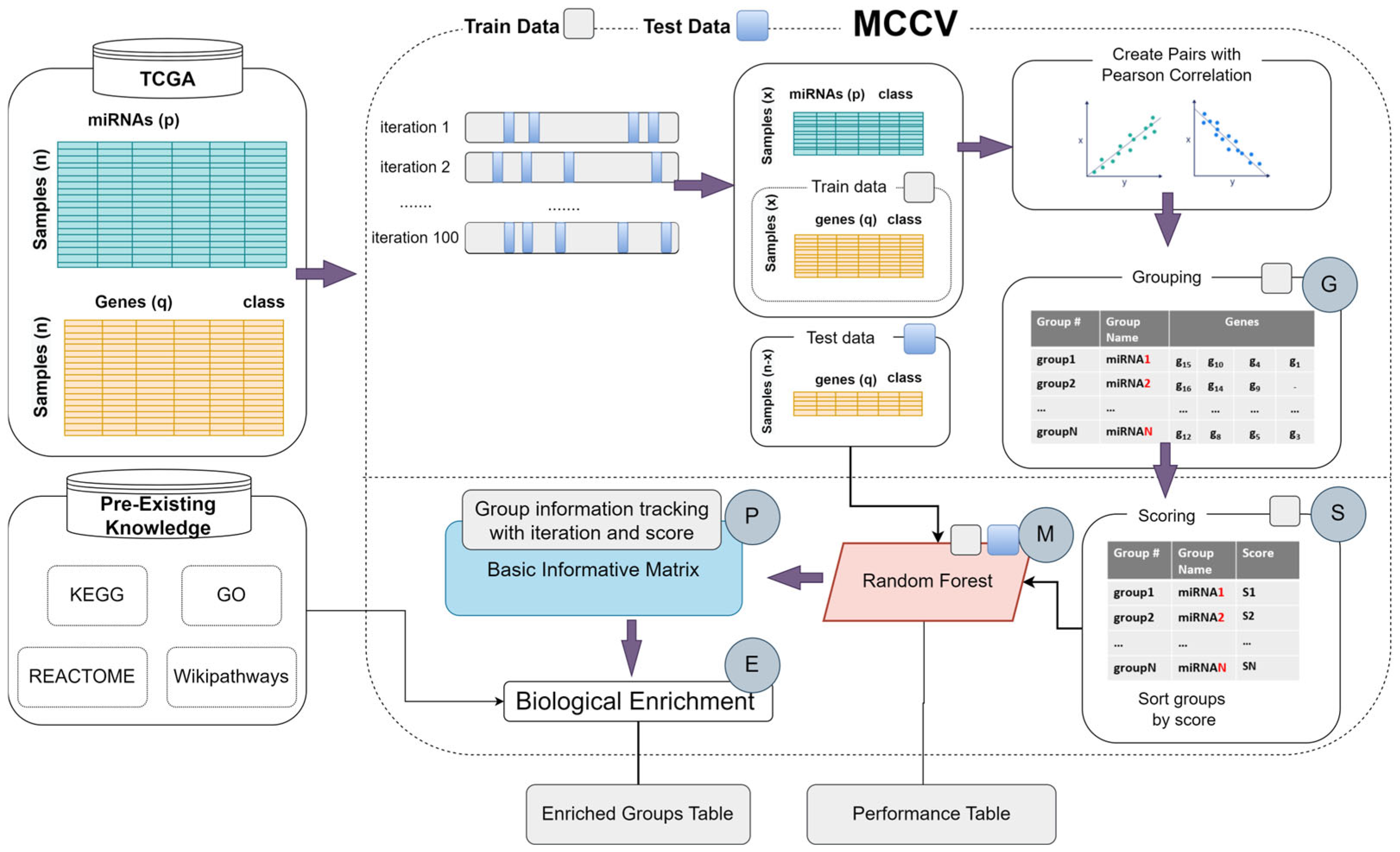

2.1.1. Design and Implementation of the G-S-M-E Tool

2.1.2. Components of the G-S-M-E Tool

- The G (grouping) component

- The S (Scoring) component

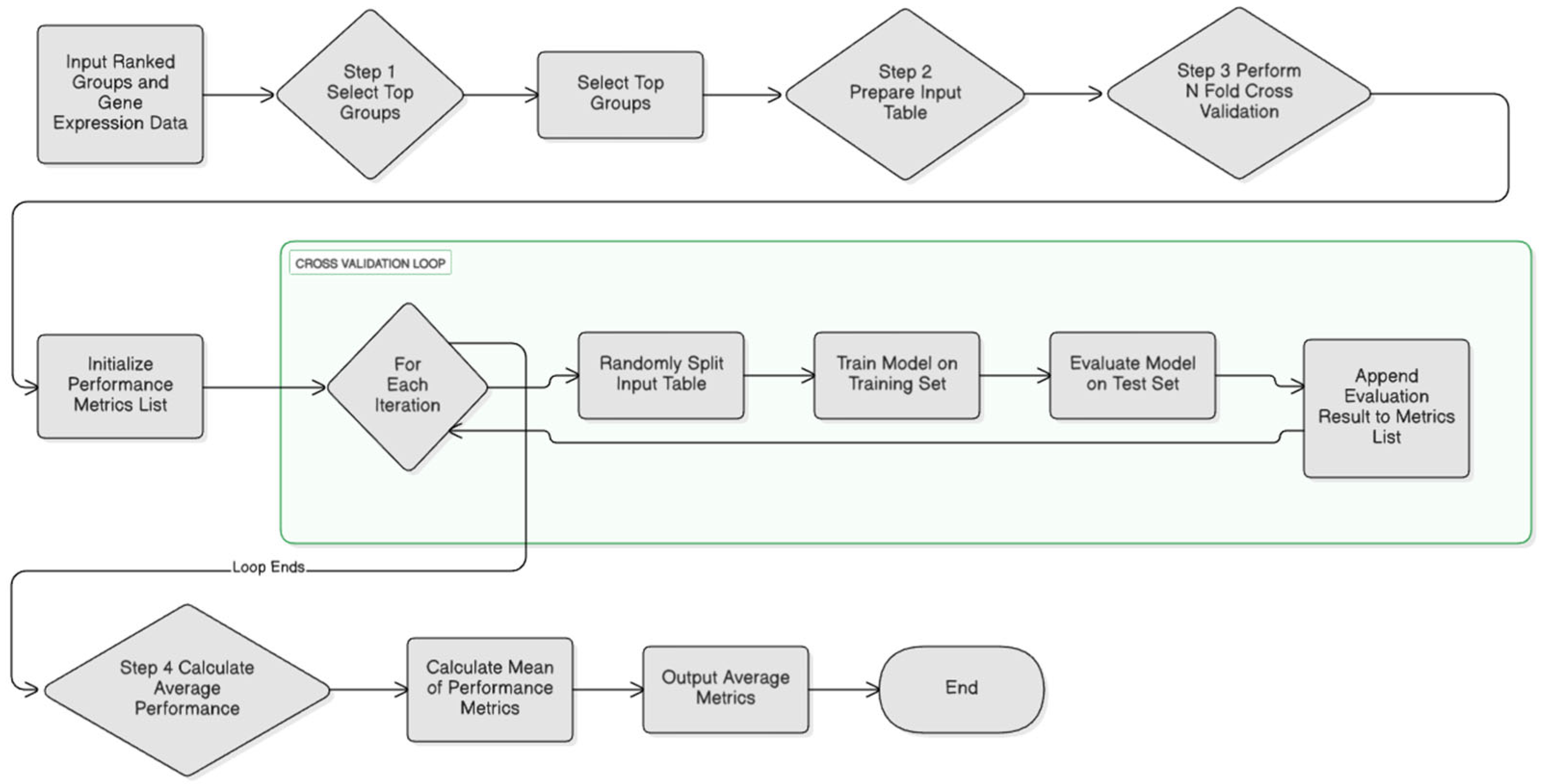

- The M (Modeling) component

- The P (Pattern Detection) component

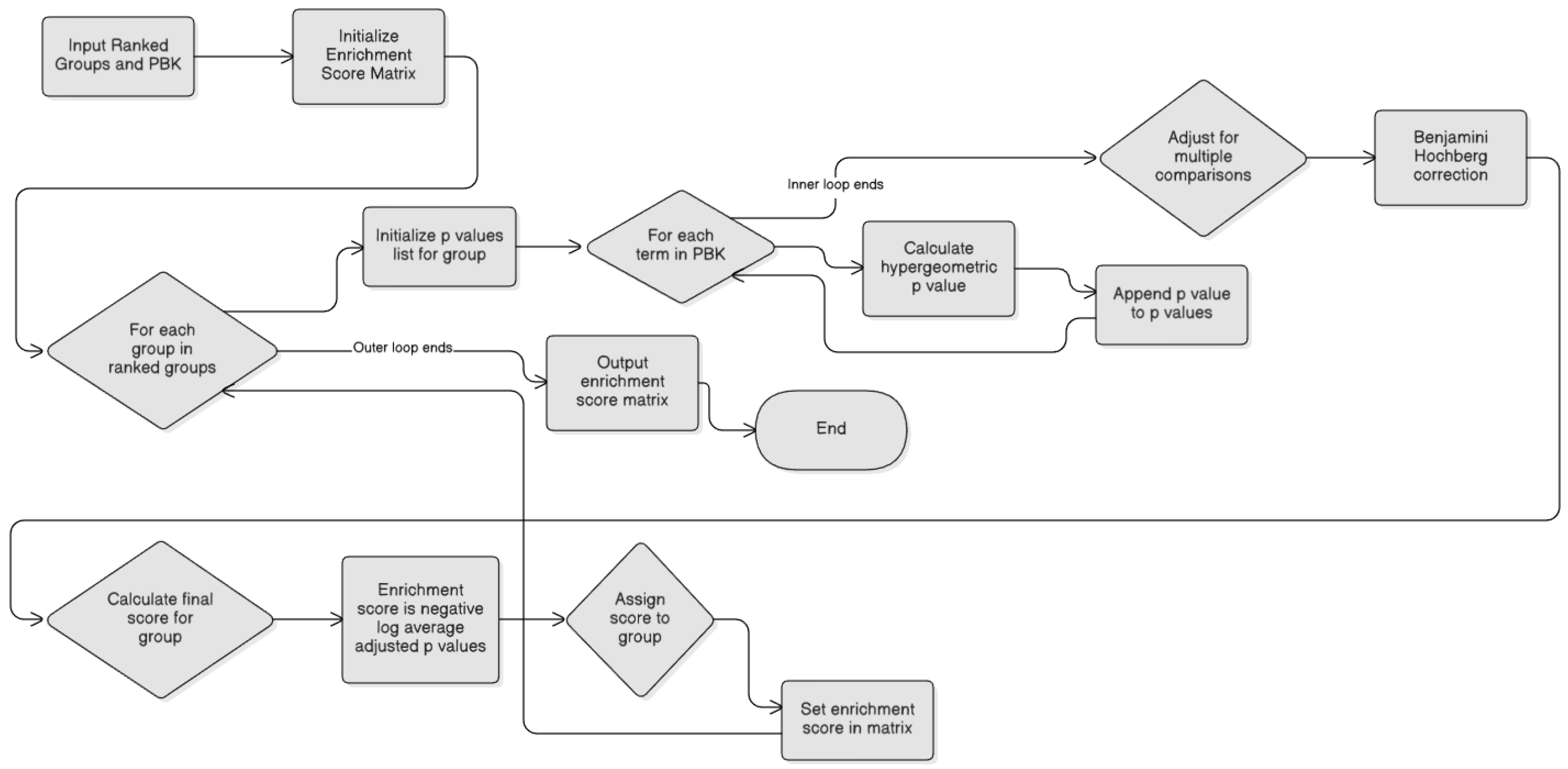

- The E (Enrichment) component: Enriched Groups with PBK

3. Results

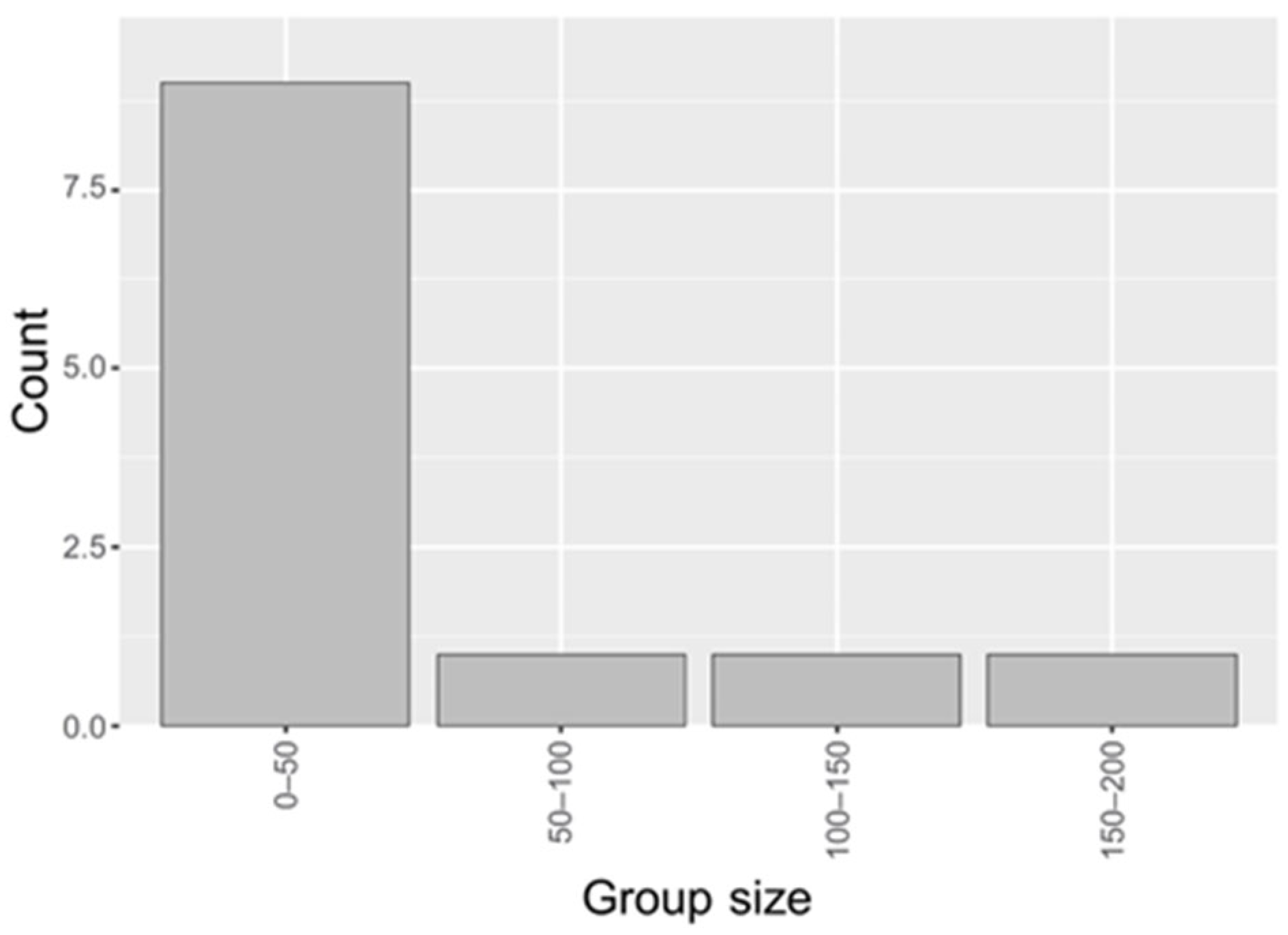

3.1. Identification of Significant Groups in the BRCA Dataset

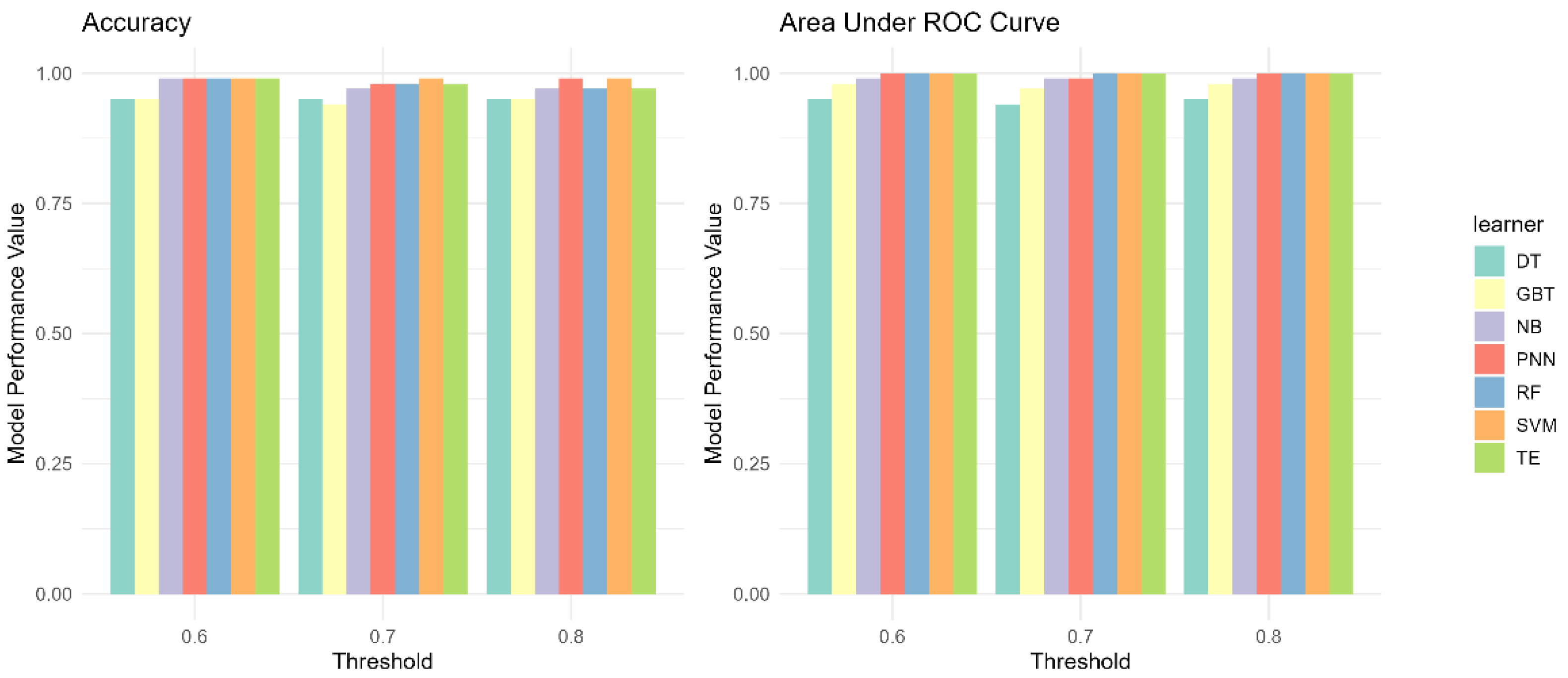

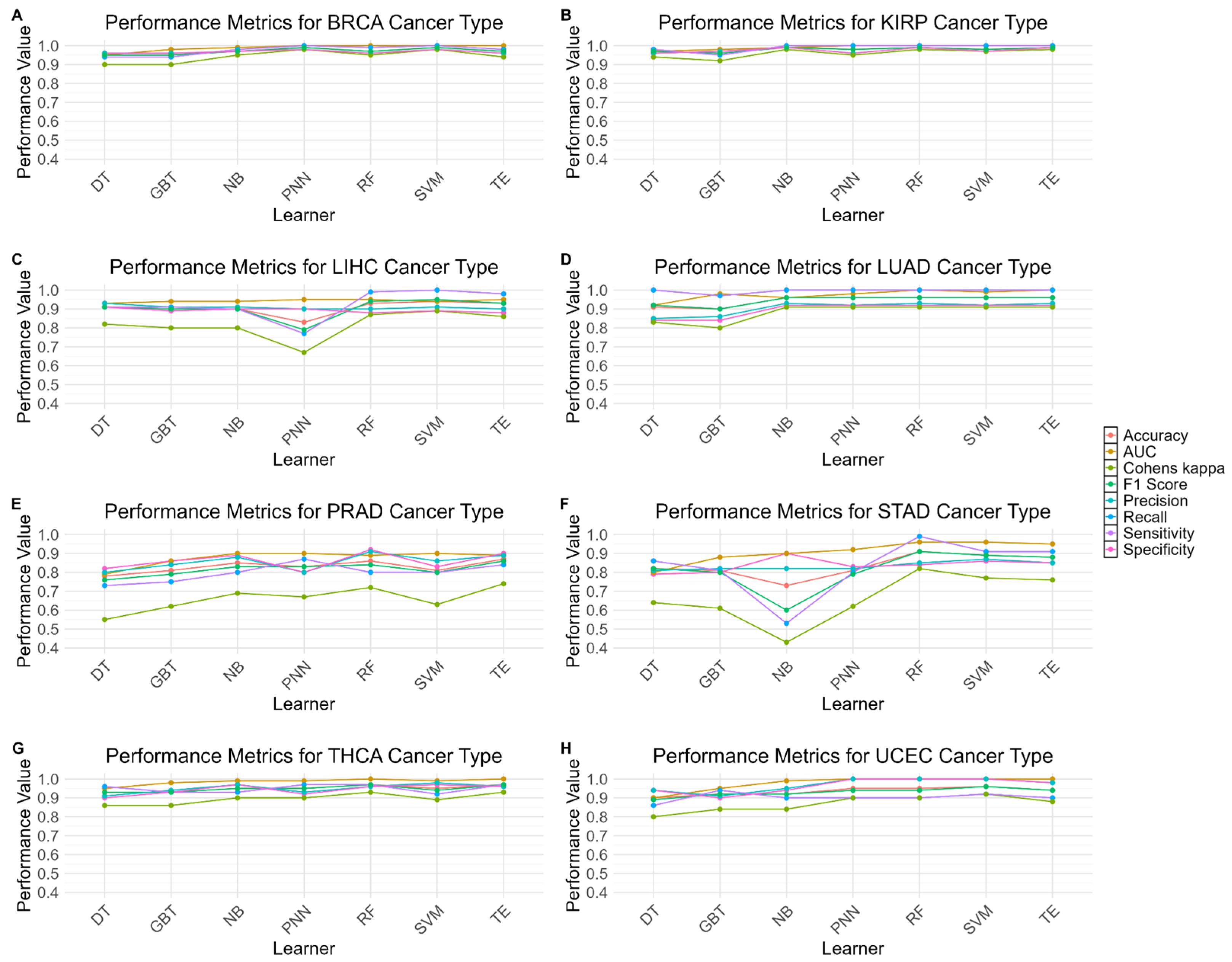

3.2. Performance Evaluation

3.3. Impact of Group Construction on G-S-M-E Classification Performance

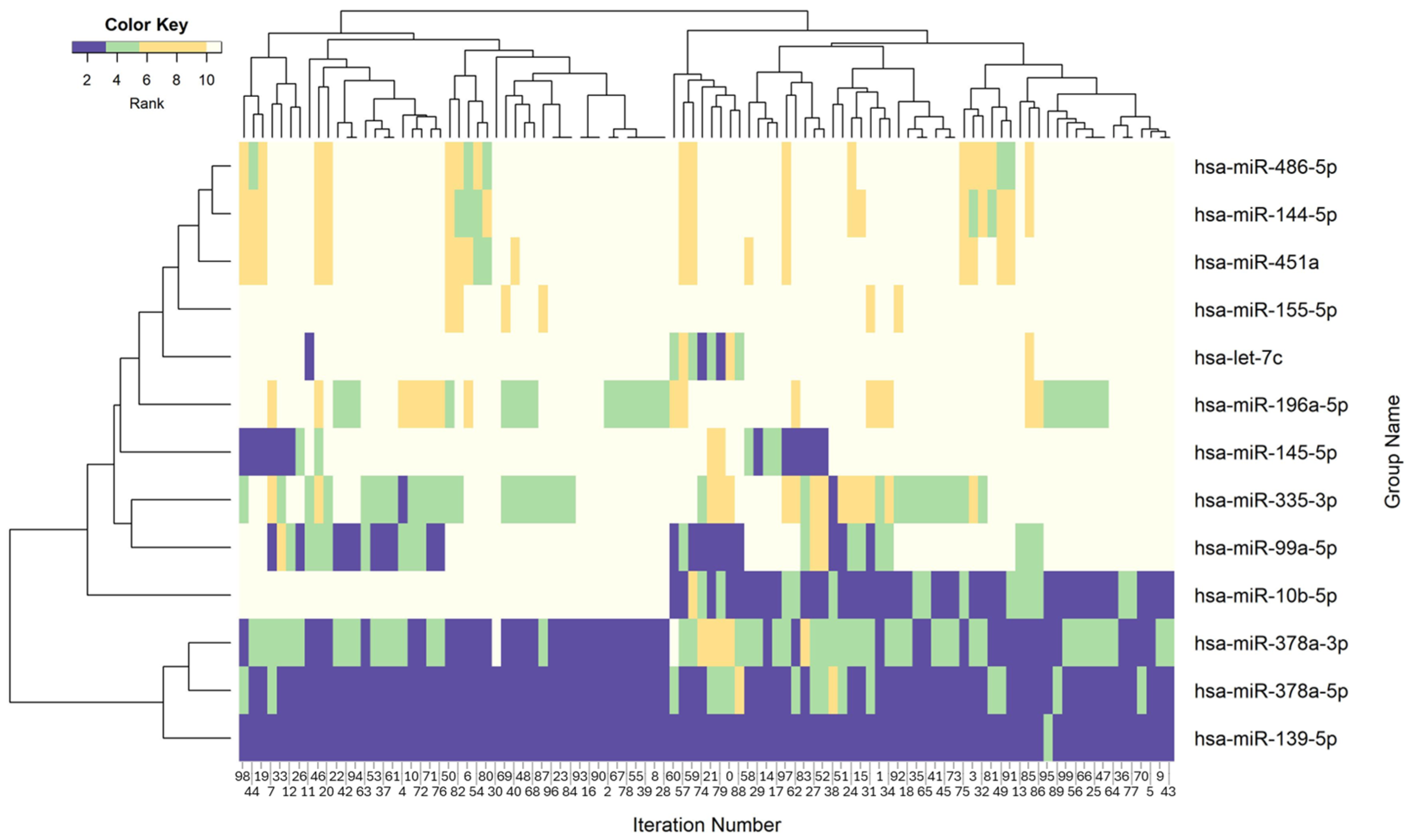

3.4. Molecular Patterns Within Identified Groups of BRCA

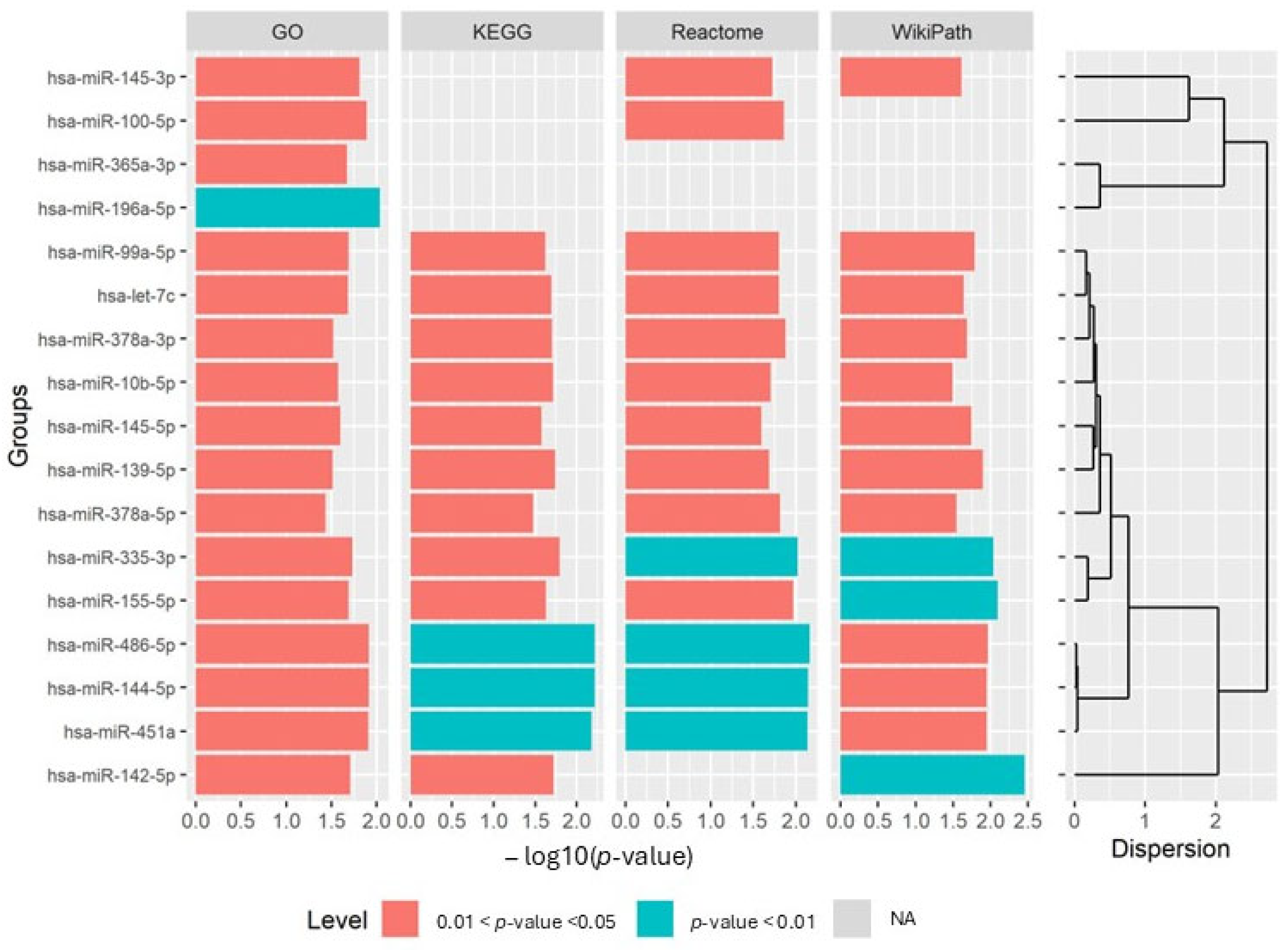

3.5. Identification of Post-Modified Groups via Functional Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological Validation of G-S-M-E Findings

4.2. Functional Validation of Post-Transcriptional Regulation via the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC): Application to LUAD and PDAC

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Decision Tree |

| GBT | Gradient Boosting Trees |

| MCCV | Monte Carlo Cross-validation |

| NB | Naïve Bayes |

| ORA | Over-representation Analysis |

| PBK | Prior Biological Knowledge |

| PNN | Probabilistic Neural Network |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TE | Tree Ensemble |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

References

- Govindaraj, V.; Kar, S. Role of microRNAs in oncogenesis: Insights from computational and systems-level modeling approaches. Comput. Syst. Oncol. 2021, 1, e1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.C.; Wani, S.; Steptoe, A.L.; Krishnan, K.; Nones, K.; Nourbakhsh, E.; Vlassov, A.; Grimmond, S.M.; Cloonan, N. Imperfect centered miRNA binding sites are common and can mediate repression of target mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broughton, J.P.; Lovci, M.T.; Huang, J.L.; Yeo, G.W.; Pasquinelli, A.E. Pairing beyond the Seed Supports MicroRNA Targeting Specificity. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tabatabaei, S.N.; Ruan, X.; Hardy, P. The Dual Regulatory Role of MiR-181a in Breast Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkovicova, D.; Smolkova, B.; Magyerkova, M.; Sestakova, Z.; Horvathova Kajabova, V.; Kulcsar, L.; Zmetakova, I.; Kalinkova, L.; Krivulcik, T.; Karaba, M.; et al. Down-regulation of traditional oncomiRs in plasma of breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 77369–77384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Narayan, R.; Subramanian, A.; Xie, X. Gene expression inference with deep learning. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommlet, F.; Szulc, P.; König, F.; Bogdan, M. Selecting predictive biomarkers from genomic data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Poulos, R.C.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Q. Machine learning for multi-omics data integration in cancer. iScience 2022, 25, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baião, A.R.; Cai, Z.; Poulos, R.C.; Robinson, P.J.; Reddel, R.R.; Zhong, Q.; Vinga, S.; Gonçalves, E. A technical review of multi-omics data integration methods: From classical statistical to deep generative approaches. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomorony, I.; Cirulli, E.T.; Huang, L.; Napier, L.A.; Heister, R.R.; Hicks, M.; Cohen, I.V.; Yu, H.-C.; Swisher, C.L.; Schenker-Ahmed, N.M.; et al. An unsupervised learning approach to identify novel signatures of health and disease from multimodal data. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kiryu, H. MODEC: An unsupervised clustering method integrating omics data for identifying cancer subtypes. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaradei, S.; Thafar, M.; Alsaedi, A.; Van Neste, C.; Gojobori, T.; Essack, M.; Gao, X. Machine learning and deep learning methods that use omics data for metastasis prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 5008–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldner-Busztin, D.; Firbas Nisantzis, P.; Edmunds, S.J.; Boza, G.; Racimo, F.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Limborg, M.T.; Lahti, L.; de Polavieja, G.G. Dealing with dimensionality: The application of machine learning to multi-omics data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valous, N.A.; Popp, F.; Zörnig, I.; Jäger, D.; Charoentong, P. Graph machine learning for integrated multi-omics analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Cai, G.; Li, Y.; Ou-Yang, L. SpaFusion: A multi-level fusion model for clustering spatial multi-omics data. Inf. Fusion 2025, 124, 103372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Liu, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, R.; Deng, W. MNMO: Discover driver genes from a multi-omics data based-multi-layer network. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Romano, J.D.; Ritchie, M.D. Network-based analyses of multiomics data in biomedicine. BioData Min. 2025, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Ye, W.; Tan, X.; Bao, Y.-J. Network-based multi-omics integrative analysis methods in drug discovery: A systematic review. BioData Min. 2025, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulos, C.; Hindupur, S.K.; Häfliger, L.; Behr, J.; Montazeri, H.; Hall, M.N.; Beerenwinkel, N. Network-based integration of multi-omics data for prioritizing cancer genes. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2441–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Shao, W.; Huang, Z.; Tang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Z.; Huang, K. MOGONET integrates multi-omics data using graph convolutional networks allowing patient classification and biomarker identification. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarada, T.N.; Rokne, J.G.; Alhajj, R. SNF-NN: Computational method to predict drug-disease interactions using similarity network fusion and neural networks. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. KEGG: New perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D353–D361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, J.; Du, W.; Liang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, F.; Tian, Y.; Ma, Q. Using Machine Learning to Measure Relatedness Between Genes: A Multi-Features Model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.-D.; Li, J.; Huang, K.-Y.; Shrestha, S.; Hong, H.-C.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.-G.; Jin, C.-N.; Yu, Y.; et al. miRTarBase 2020: Updates to the experimentally validated microRNA–target interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, gkz896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J.; Ramírez-Anguita, J.M.; Saüch-Pitarch, J.; Ronzano, F.; Centeno, E.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D845–D855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium; Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, X.; Qin, L.; Shi, W.; Bian, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Gu, J.; Hao, B.; et al. Integrative Analysis Extracts a Core ceRNA Network of the Fetal Hippocampus With Down Syndrome. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 565955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Fowdur, M.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; He, M.; Zhao, J. Differential expression and bioinformatics analysis of circRNA in osteosarcoma. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20181514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J.; Saüch, J.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. The DisGeNET cytoscape app: Exploring and visualizing disease genomics data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2960–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sticht, C.; De La Torre, C.; Parveen, A.; Gretz, N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, E.; Pučić-Baković, M.; Keser, T.; Gerstner, N.; Büyüközkan, M.; Štambuk, T.; Selman, M.H.J.; Rudan, I.; Polašek, O.; Hayward, C.; et al. A strategy to incorporate prior knowledge into correlation network cutoff selection. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yu, G.; Li, R.; Ressom, H.W. Incorporating prior biological knowledge for network-based differential gene expression analysis using differentially weighted graphical LASSO. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno, A.; López-Domínguez, R.; Villatoro-García, J.A.; Ramirez-Mena, A.; Aparicio-Puerta, E.; Hackenberg, M.; Pascual-Montano, A.; Carmona-Saez, P. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Regulatory Elements. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ietswaart, R.; Gyori, B.M.; Bachman, J.A.; Sorger, P.K.; Churchman, L.S. GeneWalk identifies relevant gene functions for a biological context using network representation learning. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomyen, Y.; Segura, M.; Ebbels, T.M.D.; Keun, H.C. Over-representation of correlation analysis (ORCA): A method for identifying associations between variable sets. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimand, J.; Isserlin, R.; Voisin, V.; Kucera, M.; Tannus-Lopes, C.; Rostamianfar, A.; Wadi, L.; Meyer, M.; Wong, J.; Xu, C.; et al. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g:Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 482–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, M.; Allmer, J.; İnal, Y.; Gungor, B.B. G-S-M: A Comprehensive Framework for Integrative Feature Selection in Omics Data Analysis and Beyond. bioRxiv 2024, 585514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-S.; Liang, Y.-Z. Monte Carlo cross validation. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2001, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthold, M.R.; Cebron, N.; Dill, F.; Gabriel, T.R.; Kötter, T.; Meinl, T.; Ohl, P.; Thiel, K.; Wiswedel, B. KNIME—The Konstanz information miner: Version 2.0 and beyond. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2009, 11, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnenführer, J.; De Bin, R.; Benner, A.; Ambrogi, F.; Lusa, L.; Boulesteix, A.-L.; Migliavacca, E.; Binder, H.; Michiels, S.; Sauerbrei, W.; et al. Statistical analysis of high-dimensional biomedical data: A gentle introduction to analytical goals, common approaches and challenges. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; He, Q.-Y. ReactomePA: An R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol. Biosyst. 2016, 12, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunnington, D.W.; Libera, N.; Kurek, J.; Spooner, I.S.; Gagnon, G.A. tidypaleo: Visualizing Paleoenvironmental Archives Using ggplot2. J. Stat. Softw. 2022, 101, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Use R! Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Role of miR-10b-5p in the prognosis of breast cancer. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søkilde, R.; Persson, H.; Ehinger, A.; Pirona, A.C.; Fernö, M.; Hegardt, C.; Larsson, C.; Loman, N.; Malmberg, M.; Rydén, L.; et al. Refinement of breast cancer molecular classification by miRNA expression profiles. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xiu, B.; Huang, S.; Chi, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, J.; et al. LINC00478-derived novel cytoplasmic lncRNA LacRNA stabilizes PHB2 and suppresses breast cancer metastasis via repressing MYC targets. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-J.; Liu, T.; Xiong, Y. Anti-cancer effect of LINC00478 in bladder cancer correlates with KDM1A-dependent MMP9 demethylation. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, E.; Zhu, J.; Feng, D.; Zhu, Y.; Dou, W.; Fan, Q.; Hu, J.; et al. Epigenetic silencing of miR-144/451a cluster contributes to HCC progression via paracrine HGF/MIF-mediated TAM remodeling. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, A.; Tang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Teschendorff, A.E. dbDEMC 2.0: Updated database of differentially expressed miRNAs in human cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D812–D818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.; Steptoe, A.L.; Martin, H.C.; Pattabiraman, D.R.; Nones, K.; Waddell, N.; Mariasegaram, M.; Simpson, P.T.; Lakhani, S.R.; Vlassov, A.; et al. miR-139-5p is a regulator of metastatic pathways in breast cancer. RNA 2013, 19, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsel, S.; Mäki-Jouppila, J.; Tambe, M.; Aure, M.R.; Pruikkonen, S.; Salmela, A.-L.; Halonen, T.; Leivonen, S.-K.; Kallio, L.; Børresen-Dale, A.-L. Excess of miRNA-378a-5p perturbs mitotic fidelity and correlates with breast cancer tumourigenesis in vivo. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 2142–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.-F.; Shi, Z.-M.; Li, D.-M.; Qian, Y.-C.; Ren, Y.; Bai, X.-M.; Xie, Y.-X.; Wang, L.; Ge, X.; Liu, W.-T.; et al. Estrogen-induced miR-196a elevation promotes tumor growth and metastasis via targeting SPRED1 in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.-Y.; He, R.-H.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.-J.; Wan, Z.; Zhou, C.-F.; Tang, Y.-J.; Li, Z.; Mcleod, H.L.; Liu, J. β-blockers inhibit the viability of breast cancer cells by regulating the ERK/COX-2 signaling pathway and the drug response is affected by ADRB2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Q.; Xu, K.; Luo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Ren, G. BTNL9 is frequently downregulated and inhibits proliferation and metastasis via the P53/CDC25C and P53/GADD45 pathways in breast cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 553, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Chen, Y.; Waili, N.; Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, Y. Associations of serum C-peptide and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins-3 with breast cancer deaths. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S.A.; Güngör, C.; Prenzel, T.; Riethdorf, S.; Riethdorf, L.; Taniguchi-Ishigaki, N.; Rau, T.; Tursun, B.; Furlow, J.D.; Sauter, G.; et al. Regulation of Estrogen-Dependent Transcription by the LIM Cofactors CLIM and RLIM in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Beeghly-Fadiel, A.; Lu, W.; Shi, J.; Xiang, Y.-B.; Cai, Q.; Shen, H.; Shen, C.-Y.; Ren, Z.; Matsuo, K.; et al. Pathway Analyses Identify TGFBR2 as Potential Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene: Results from a Consortium Study among Asians. Cancer Epidemiology. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cancer Type | TCGA ID | Number of Case Samples | Number of Control Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast invasive carcinoma | BRCA | 760 | 87 |

| Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma | KIRP | 290 | 32 |

| Liver hepatocellular carcinoma | LIHC | 367 | 44 |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | LUAD | 449 | 20 |

| Prostate adenocarcinoma | PRAD | 493 | 52 |

| Stomach adenocarcinoma | STAD | 370 | 35 |

| Thyroid carcinoma | THCA | 506 | 59 |

| Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma | UCEC | 174 | 23 |

| Group Name | miRNA Associated Genes |

|---|---|

| hsa-miR-139-5p | LRRN4CL, LOC90586, NRN1, TGFBR2, … |

| hsa-miR-378a-5p | SYNPO, C17orf103, HSPB6, … |

| … | … |

| hsa-miR-10b-5p | IL33, ADAMTS5, ABCA10, DMD, … |

| Scorej | Rank (Scorej) |

|---|---|

| ≥0.95 | 1 |

| ≥0.90 and <0.95 | 2 |

| … | … |

| ≥0.50 and <0.55 | 10 |

| <0.50 | 0 |

| P (gi, inj) | Significance Level |

|---|---|

| 1 | High significance (ranking) level of gi in iteration inj |

| 2 to 10 | Gradually decreasing significance level of gi in iteration inj |

| 0 | Group gi does not appear in iteration inj |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Unlu Yazici, M.; Bakir-Gungor, B.; Yousef, M. G-S-M-E: A Prior Biological Knowledge-Based Pattern Detection and Enrichment Framework for Multi-Omics Data Integration. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12669. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312669

Unlu Yazici M, Bakir-Gungor B, Yousef M. G-S-M-E: A Prior Biological Knowledge-Based Pattern Detection and Enrichment Framework for Multi-Omics Data Integration. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12669. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312669

Chicago/Turabian StyleUnlu Yazici, Miray, Burcu Bakir-Gungor, and Malik Yousef. 2025. "G-S-M-E: A Prior Biological Knowledge-Based Pattern Detection and Enrichment Framework for Multi-Omics Data Integration" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12669. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312669

APA StyleUnlu Yazici, M., Bakir-Gungor, B., & Yousef, M. (2025). G-S-M-E: A Prior Biological Knowledge-Based Pattern Detection and Enrichment Framework for Multi-Omics Data Integration. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12669. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312669