Optimization of the Technical Parameters of Universal Freight Wagons

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Information on operating costs in the European Union (EU) is incomplete, difficult to access and completely non-functional [13]. As an example, it is stated that even in countries with published methodologies for determining infrastructure access charges, a carrier cannot calculate its costs accurately. The reason for this is the presence of numerous conditions depending on the type and prices of energy sources, the presence or absence of engineering facilities (tunnels, bridges, etc.), route traffic, track development and many others.

- There are huge differences in capital costs across countries and regions. For example, the cost of building a railway track varies from 1.5 to 70 million EUR/km [6]; the cost of fixed (station and ancillary) equipment ranges from EUR 2 to 100 million [6]; the cost of new rolling stock varies in a ratio of minimum to maximum price of 1:9 (own studies); the ratios for land, electrification, signaling systems, etc., are approximately similar.

- There are large differences in operating costs, including infrastructure access charges ranging from 0.5 to 11.5 EUR/train-km [13], cost of energy sources, cost of repair and maintenance of rolling stock, wages, etc.

- It should depend solely on the design parameters of the wagon and the physical properties of the cargo;

- It should ensure maximum use of the permissible wagon gross weight on the given rail track;

- There must be sufficiently simple functional dependencies between it and the other parameters related to the optimization;

- There must be a minimum corresponding to the minimum of the “adjusted costs”. wages, etc.;

2. Analysis of Technical Optimization Parameters

2.1. Absolute Technical Parameters

2.2. Relative Technical Parameters

2.2.1. Axle Load

2.2.2. Load per Linear Meter

2.2.3. Tare Coefficients

2.2.4. Specific Volume and Specific Area

3. Basic Principles for Optimization of the Specific Volume (Area) of Freight Wagons

3.1. Optimization Criterion

- ty and t′y are relative variable components of the tare weight per unit volume or area, respectively, determined by Equation (23):

- Tp is the constant component of the tare weight, including the weight of the drawing gear equipment, doors, hatches, running gear, elements of the braking equipment and other elements whose weight does not depend on the linear dimensions of the wagon;

- vy and fy are the current values of the specific volume and specific area of the wagon;

- ai is the relative share in the cargo turnover of the i-th cargo as determined in Equation (26);

- vyi and fyi are the specific volume and specific area of the i-th cargo;

- is a constant, which, in general, can be equal to or less than 1 (B < 1 if the data on the transported cargo is incomplete);

- k is the nearest number from the row indices in Equation (15) for which the load capacity P is used (k = 1, …, m);

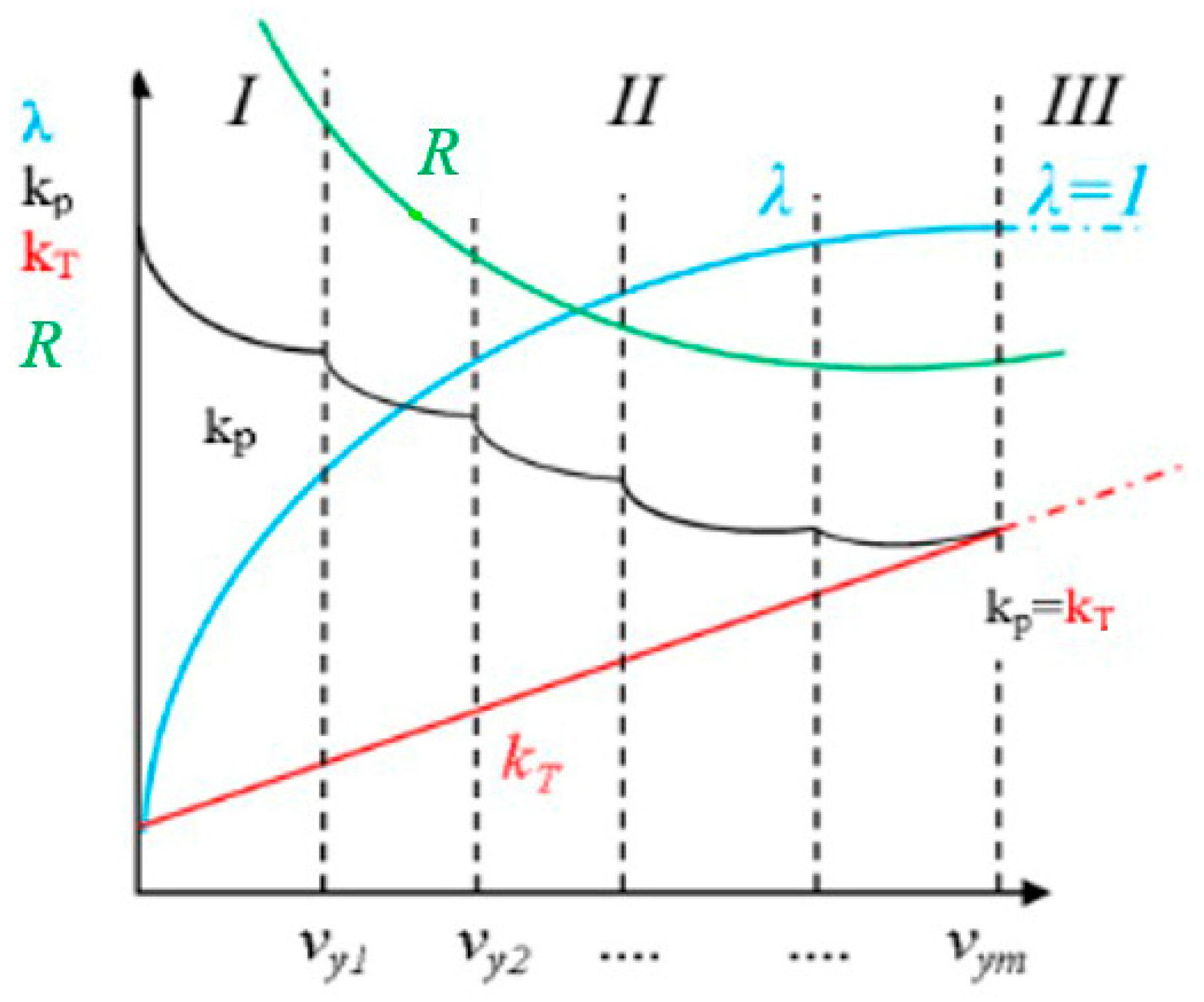

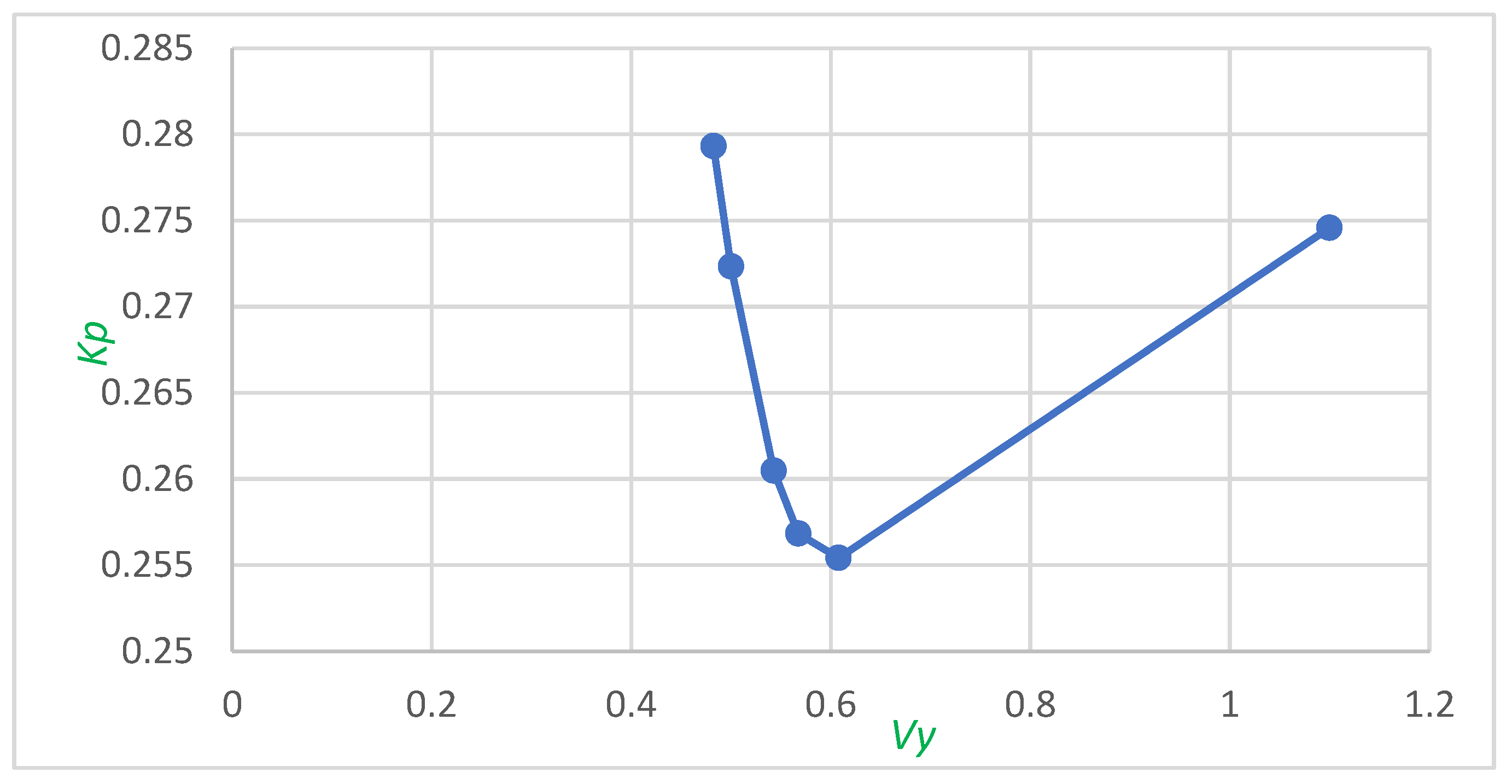

- A, A′ and C are coefficients, constant for a given type of wagon, which are determined by Equation (24):The graphical variation in λ, kT and kp is shown in Figure 3. For completeness of the figure, the graph of the change in the adjusted cost parameter R is also given. The nature of the change in the functions R = R(vy) and kp = kp(vy) is similar. The difference between the two curves is that the theoretical curve R = R(vy) is defined as a continuous function, while the curve kp = kp(vy) is considered as a partially continuous function.

- The load capacity utilization coefficient λ (see Equation (20)) increases non-linearly with increasing specific volume of the wagon body. It reaches its maximum λmax = 1 when the specific volume (area) of the wagon body corresponds to the lightest cargo type, i.e., when Equation (25) is satisfied:In this case, all expected cargo types can be loaded into the wagon, but to a height corresponding to the maximum load capacity Pmax = n·p0 − T of the wagon. From this, two main conclusions follow:

- -

- The parameters specific volume vy, and therefore geometric volume V should not be increased above vymax, as this leads to an increase in the tare weight T of the wagon and a decrease in its load capacity P;

- -

- At vy = vym = vymax, the geometric volume of the wagon will be fully used only when transporting the lightest cargo. For all other cargoes, there will be an unusable volume, leading to the transportation of excess tare weight T and a decrease in the load capacity of the vehicle P.

- 2.

- The technical tare coefficient kT increases linearly with increasing specific volume (area) of the wagon body as given in Equation (21). Therefore, using the value of vy > vymax increases the tare weight of the wagon T and reduces its load capacity P, which makes the vehicle inefficient.

- 3.

- The loading tare coefficient kp is changed as follows:

- According to hyperbolic law in the interval 0 < vy < vy1 (zone I in Figure 3), there is a constant decrease with increasing specific volume (area). The reason for this is that in this interval none of the cargoes will use the wagon’s load capacity and, therefore, the sum in the denominator of Equation (20) will be equal to zero;

- In the interval vy1 ≤ vy ≤ vym (zone II in Figure 3), the function kp = kp(vy) is partially continuous, with the inflection points corresponding to the values of the argument vy = vy1, vy2…, vym. The reason for this is that the sum of Equation (20) increases with increasing vy, and the sum decreases. The minimum of the function is located exactly in this interval;

- In the interval vym < vy < ∞ (zone III in Figure 3), the loading tare coefficient kp equals the technical one (kT where λ = 1) and increases linearly with increasing specific volume of the wagon body.

3.2. Specific Volume (Area) Optimization Methodology

3.2.1. Finding the Minimum of a Non-Linear Partially Continuous Function

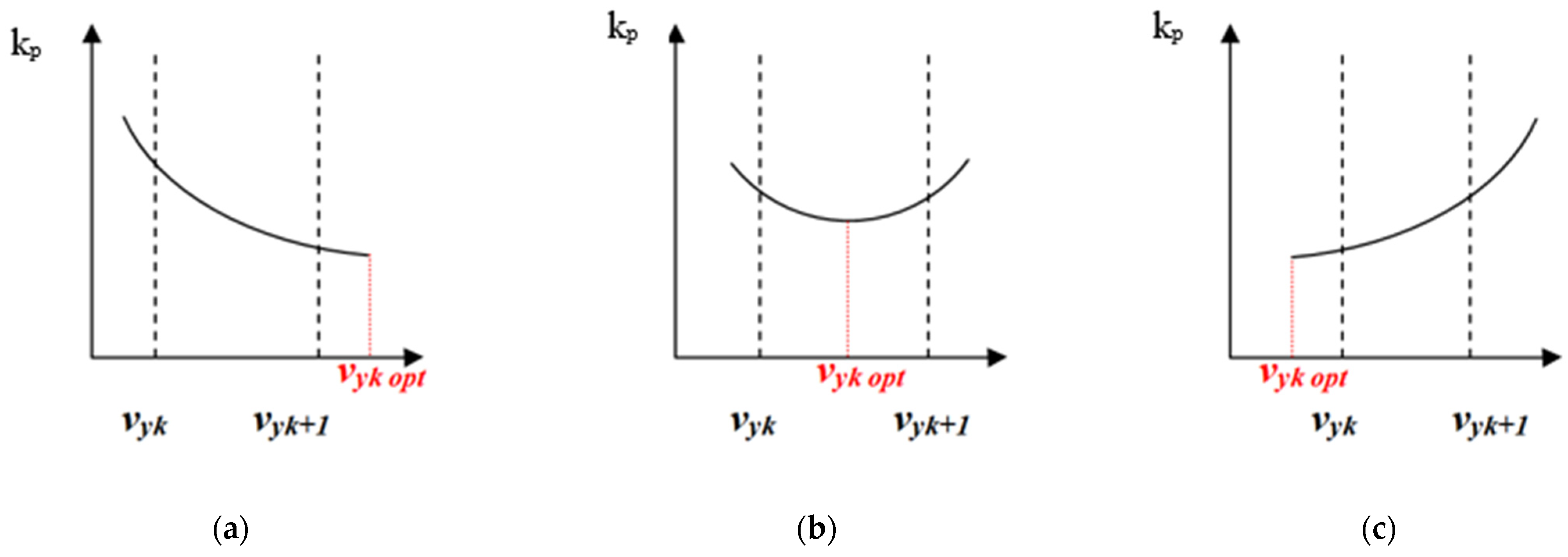

- vyk opt > vyk+1 (Figure 4a)—since the function is decreasing in the entire interval [vyk, vyk+1], the function is decreasing too. Therefore, the local minimum of kp will be obtained at the value of the argument vy = vyk+1;

- vyk < vyk opt < vyk+1 (Figure 4b)—the local minimum of kp is in the interval [vyk, vyk+1] and corresponds to the value of the argument vy = vyk opt;

- vyk opt < vyk (Figure 4c)—in this case, the function is increasing in the entire interval [vyk, vyk+1], from which it follows that the local minimum of kp is obtained at the value of the argument vy = vyk.

3.2.2. Algorithm for Optimization of Specific Volume (Area)

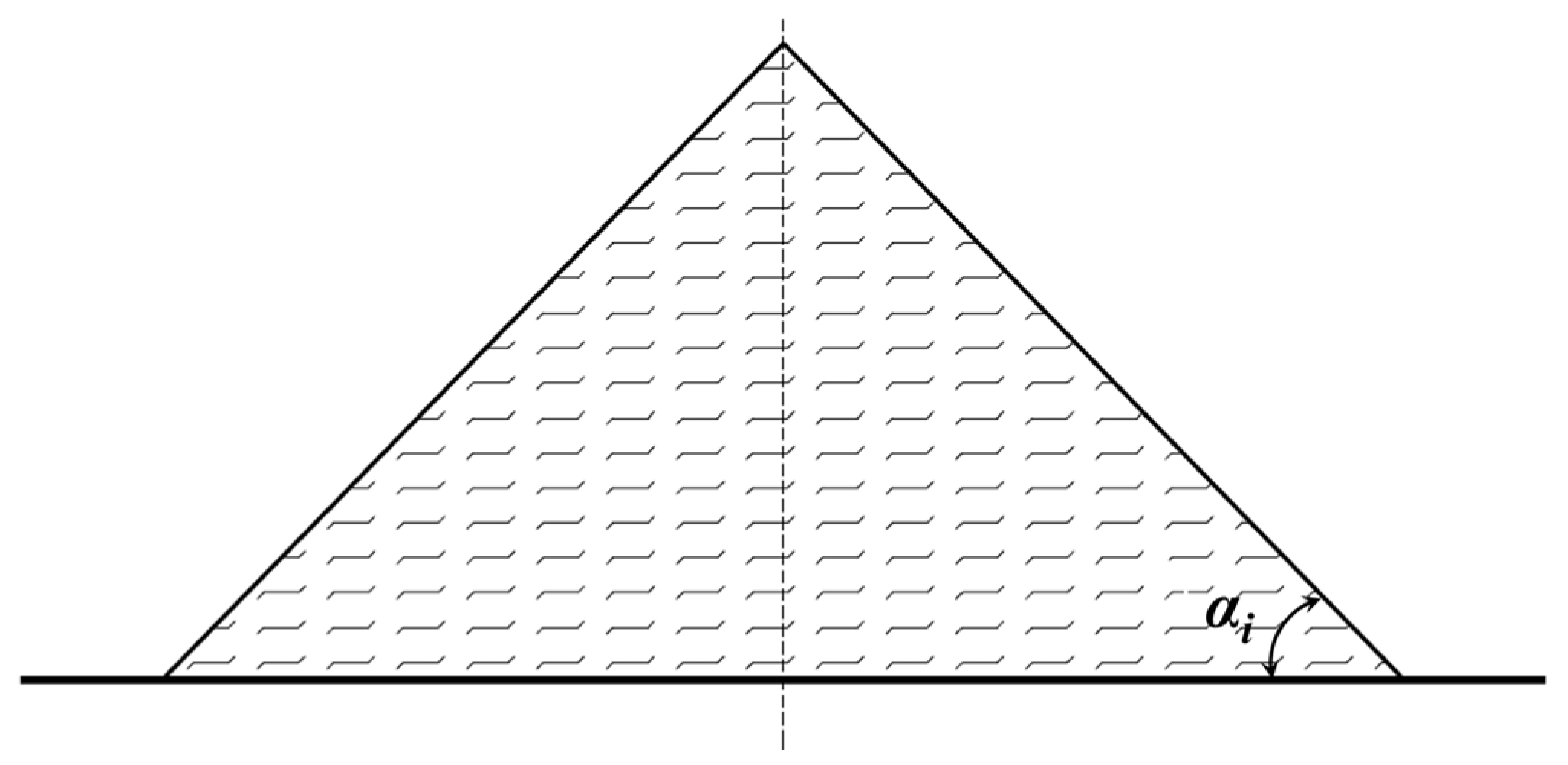

- For optimization purposes, the following initial data are required for each load:—number of cargo types—m, density—γi, angle of repose—αi, mass of the cargo—Mi, average transportation distance—Li. The mass of the cargo—Mi and average transportation distance—Li can be replaced by the parameter average transportation work Si = Mi·Li.

- The relative share in the total cargo turnover for each of the transported cargo types is determined using Equation (26):

- 3.

- The maximum values of the wagon volume utilization coefficients φimax for each load are determined using the data from Table 1.

- 4.

- The specific volumes vyi required for the full use of the wagon capacity and volume for each cargo type are calculated using Equation (27):

- 5.

- The ascending order of specific volumes is formed using Equation (28):

- 6.

- The absolute minimum of the loading tare coefficient kp is determined in the following sequence:

- The optimal values of the specific volume vykopt are calculated for each of the intervals vyk < vy < vyk+1 from the row obtained in step 5 using Equation (29):Equation (29) is obtained after finding the first derivative of the function kp = kp(vy) in the interval [vyk, vyk+1], equating the obtained result to zero and solving for vy:

- For the intervals for which the condition in Equation (30) is met

- The local minima kpk min are calculated using Equation (31) after replacing vy with vykopt from Equation (29) in Equation (22):

- For the intervals for which condition (30) is not met, the boundary values k′pk are determined at vy = vyk using Equation (32):

- The loading tare coefficient kp is calculated for the boundary value between zone II and III (Figure 3) at vy = vym using Equation (33):

- The local minima from Equations (31)–(33) are compared, with the absolute minimum kp min corresponding to the smallest of them using Equation (34):

- 7.

- The optimal value of the specific volume vyopt corresponds to the absolute minimum of the loading tare coefficient kp min.

3.3. Methodology for Determining the Parameters Volume, Tare Weight and Load Capacity of the Optimized Wagon

3.3.1. Determining the Geometric Volume of the New Freight Wagon

3.3.2. Determining the Tare Weight and Load Capacity of the New Freight Wagon

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETP | Economic technical parameters |

| UIC | Union internationale des chemins de fer (International Union of Railways) |

| EU | European Union |

| TSI | Technical Specification for Interoperability |

| BDZ-TP | Bulgarian State Railways-Freight Transport Ltd. |

Table of Notations

| Notation | Parameter Description | Unit |

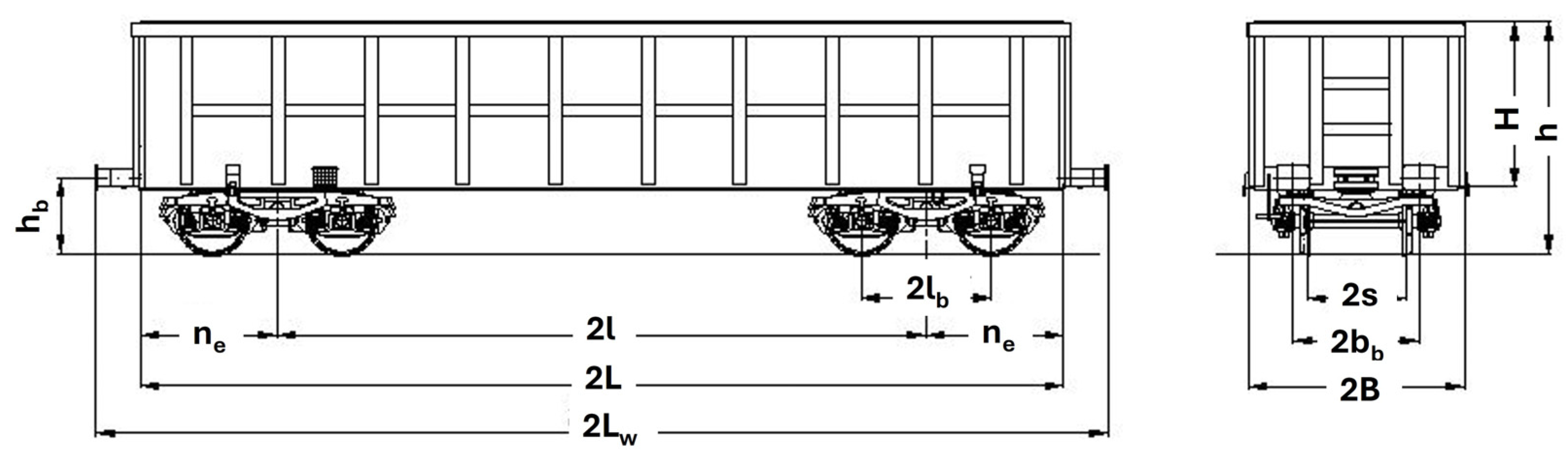

| 2Lw | Total length of the wagon (with buffers) | m |

| 2L | Length of the wagon body (without buffers) | m |

| 2l | Pivot distance | m |

| ne | Length of the end part | m |

| 2lb | Base of the bogie (axles distance in the bogie) | m |

| 2B | Width of the wagon | m |

| 2bb | Distance between the buffers | m |

| 2s | Track gauge | m |

| H | Height of the wagon body | m |

| hb | Height of the buffers from the rail head | m |

| h | Total height of the wagon from the rail head | m |

| F | Area of the wagon floor | m2 |

| V | Volume of the body | m3 |

| T | Own weight of the wagon (tare weight) | t |

| P | Load capacity (maximum permissible payload) | t |

| Q | Gross weight of the wagon | t |

| n | Number of axles | - |

| p0 | Axle load | t/axle |

| q | Load per linear meter | t/m |

| kT | Technical tare coefficient | - |

| kp | Loading tare coefficient | - |

| λ | Coefficient of load capacity utilization | - |

| λv | Coefficient of load capacity utilization for specific volume | - |

| λf | Coefficient of load capacity utilization for specific area | - |

| au | Relative share in the freight turnover of the cargo goods for which the wagon’s load capacity is used | - |

| an | Relative share in the freight turnover of the cargo goods for which the wagon’s load capacity is not used | - |

| vy | Specific volume | m3/t |

| fy | Specific area | m2/t |

| vyT | Specific volume of respective loads | m3/t |

| fyT | Specific area of respective loads | m2/t |

| kO | Operational tare coefficient | - |

| αe | Empty mileage coefficient | - |

| Pad | Average dynamic load | t |

| VT | Cargo volume | m3 |

| φ | Volume utilization coefficient | - |

| αi | Angle of repose of bulk cargo | ° |

| HT | Height of the cargo | m |

| γ | Density | t/m3 |

| ty | Relative variable components of the tare weight per unit volume | t/m3 |

| ty′ | Relative variable components of the tare weight per unit area | t/m2 |

| Tp | Constant component of the tare weight | t |

| B | Constant equal to the sum of the relative shares in the cargo turnover | - |

| A | Constant coefficient for a given type of wagon | - |

| A′ | Constant coefficient for a given type of wagon | - |

| C | Constant coefficient for a given type of wagon | - |

| vykopt | Optimal specific volume of cargo k | m3/t |

| m | Number of cargo types | - |

| Mi | Mass of the i-th cargo | t |

| Li | Average transportation distance | km |

| Si | Average transportation work | t.km |

| kpk min | Local minimum of loading tare coefficient | - |

| k′pk | Boundary value of loading tare coefficient | - |

| fy opt | Optimal specific area of the wagon body | m2/t |

| Vnew | Volume of newly designed wagon | m3 |

| Vprot | Volume of the prototype wagon | m3 |

| ζ | Correction coefficient | - |

| vy prot | Specific volume of the prototype wagon | m3/t |

| Tnew | Tare weight of the new freight wagon | t |

| Pnew | Load capacity of newly designed wagon | t |

References

- Matthiesen, S. Gestaltung—Prozess und Methoden (Designing—Process and Methods). In Pahl/Beitz Konstruktionslehre (Pahl/Beitz Design), 9th ed.; Bender, B., Gericke, K., Eds.; Springer Vieweg: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 397–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadur, L.A. Wagons. Design, theory and calculations, 1st ed.; Transport: Moscow, Russia, 1980; Available online: https://www.studmed.ru/shadur-lared-vagony-konstrukciya-teoriya-i-raschet_893a40e66cf.html (accessed on 30 October 2025). (In Russian)

- Dolinayová, A.; Ľoch, M.; Kanis, J. Modelling the influence of wagon technical parameters on variable costs in rail freight transport. Res. Transp. Econ. 2015, 54, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhr, H.; Schneider, P.; Karch, S. Schienengüterverkehr (Railway freight Transport), 1st ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023; pp. 30–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoliov, V.; Slavchev, S. Wagons, 1st ed.; Technical University Sofia: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2014; pp. 16–36. ISBN 978-619-167-135-9. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso, D.; Restuccia, A. A Tool for Railway Transport Cost Evaluation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 111, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.F.M.; Saad, N.H.; Yahaya, M.I.; Shuib, A.; Mohamed, W.M.W.; Amin, A.N.M. Cost of Rolling Stock Maintenance in Urban Railway Operation: Literature Review and Direction. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 30, 1045–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Bruzelius, N.; van Wee, B. Comparison of Capital Costs per Route-Kilometre in Urban Rail. Europ. J. Transp. Infrastr. Res. 2008, 8, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.G. Relationship Between rail Service Operating Direct Costs and Speed; Study and Research Group for Economics and Transport Operation, International Union of Railways & Fundacìon de los Ferrocarriles Españoles (UIC): Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, N.; Økland, A.; Halvorsen, S. Consequences of differences in cost-benefit methodology in railway infrastructure appraisal—A comparison between selected countries. Transp. Policy 2012, 22, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, A. Comparable Cost Calculation for Infrastructure of Road and Rail. In Proceedings of the Conference on Applied Infrastructure Research (InfraDay), Berlin, Germany, 29 October 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, J.P. Prices and Costs in the Railway Sector; LITEP (Laboratoire d’Intermodalitè des Transports Et de Planification), Ecole Politechnique Federale de Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, L.S. Railway Access Charges in the EU: Current Status and Developments Since 2004; OECD-ITF Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schöne, A.; Kunz-Kaltenhäuser, P. Track access charges in the European Union railroad sector: A consideration of company organization and institutional quality. Ilmenau Econ. Disc. Pap. 2022, 27, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Anupriya; Graham, D.J.; Carbo, J.M.; Anderson, R.J.; Bansal, P. Understanding the costs of urban rail transport operations. Transp. Res. Part B Meth. 2020, 138, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Song, Y.; Qi, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, X. Real-Time Global Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Connected PHEVs Based on Traffic Flow Information. IEEE Trans. Intel. Transp. Sys. 2024, 25, 20032–20042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Lan, P.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Peng, F.; Hong, J. Multi-U-Style micro-channel in liquid cooling plate for thermal management of power batteries. Appl. Ther. Eng. 2024, 256, 123984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UIC CODE 510-2; Trailing stock: Wheels and Wheelsets, 4th ed. UIC: Paris, France, 2004. Available online: https://shop.uic.org/en/51-running-and-suspension-gear/914-trailing-stock-wheels-and-wheelsets-conditions-concerning-the-use-of-wheels-of-various-diameters.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- EN 13260:2020; Railway applications—Wheelsets and bogies—Wheelsets—Product requirements. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- TSI WAG.; Technical Specifications for Interoperability—Rolling stock—Freight Wagons. European Union Agency for Railways: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Jong, J.C.; Chang, E.F. Models for estimating energy consumption of electric trains. J. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2005, 6, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, V.; Nocchia, S. Maintenance and repair of rolling stock. Weld. Int. 2008, 22, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Yang, A.S.; Tsao, H.L. Study on rolling stock maintenance strategy and spares parts management. In Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Railway Research, Montréal, QC, Canada, 4–8 June 2006; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Tsao, H.L. Rolling stock maintenance strategy selection, spares parts’ estimation, and replacements’ interval calculation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 128, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findik, F.; Turan, K. Materials selection for lighter wagon design with a weighted property index method. Mater. Des. 2012, 37, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilov, V. Lightening Freight Wagons Through Appropriate Choice of ETP and Calculation Methods (in Bulgarian). Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Sofia, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 4-axle Open Wagon for Carriage of Ores and Bulk Goods Type Eamnos. BDZ-Cargo Website. Available online: https://bdzcargo.bdz.bg/en/wagon-fleet/wagon-freight-open-4-axled-for-the-carriage-of-ores-and-loose-goods-eamnos-type.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- BDZ-TP Consolidated Activity Report for Year 2022 (in Bulgarian). Available online: https://p1.bdz.bg/c/i/cifs-31122022-19615.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- National Statistical Institute. Goods Carried and Transport Performance by the Railway Transport—Annual Data for 2022. Available online: https://infostat.nsi.bg/infostat/pages/reports/result.jsf?x_2=772 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

| Wagon Type | Cargo Type | φmax |

|---|---|---|

| Open and flat wagons | bulk | 1 + (3/8)·tg αi ≤ 1.35 |

| non-bulk | 1.35 | |

| Covered wagons | all | 0.9 |

| Tank wagons | all | 0.99 |

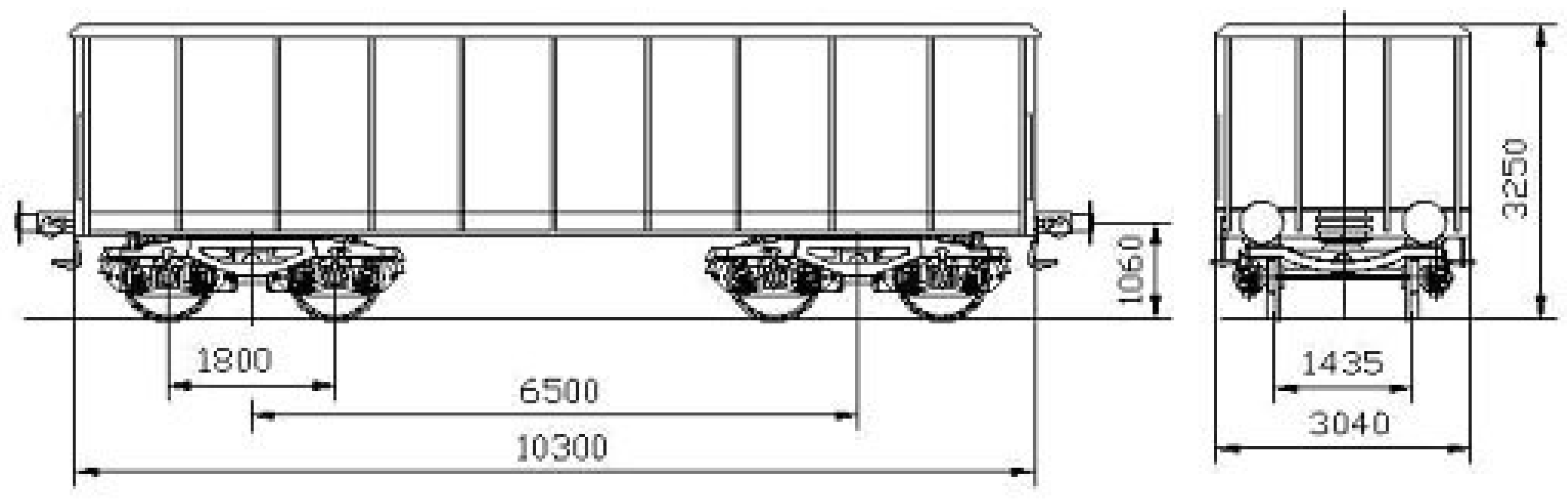

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of axles | - | 4 |

| Axle load | t/axle | 20 |

| Maximum load capacity | t | 61 |

| Tare weight | t | 19 |

| Pivot distance | m | 6.5 |

| Wagon floor area | m2 | 30 |

| Geometric volume of the wagon | m3 | 56 |

| Cargo No. | Unit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo type | - | Solid mineral and plant-based fuels | Ferrous metal ores | Scrap | Limestone | Inert materials | Copper ore | Other | - |

| Density γi | t/m3 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | - | - |

| Angle of repose αi | Degree ° | 20 | 22 | 0 | 25 | 25 | 22 | - | - |

| Cargo weight Mi | 103 t | 320.24 | 732.36 | 440.06 | 314.6 | 734.06 | 452 | 103.45 | 3096.77 |

| Average transport work Si = Mi·Li | 106 t·km | 108 | 221.42 | 133.06 | 100.04 | 233.4 | 174.28 | 193.45 | 1163.65 |

| Volume utilization coefficient φmax | - | 1.136 | 1.151 | 1 | 1.174 | 1.1748 | 1.151 | - | - |

| Relative share in cargo turnover ai | - | 0.093 | 0.190 | 0.114 | 0.086 | 0.201 | 0.150 | 0.166 | 1 |

| Specific volume for the full use of the wagon capacity and volume vyi | m3/t | 1.100 | 0.543 | 0.5 | 0.608 | 0.567 | 0.482 |

| Parameter | Unit | Values for Prototype Wagon | Values for Optimized Wagon Iteration 1 | Values for Optimized Wagon Iteration 2 | Values for Optimized Wagon Iteration 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric volume of the wagon V | m3 | 56 | 37.086 | 38.000 | 37.957 |

| Maximum load capacity P | t | 61 | 62.520 | 62.427 | 62.432 |

| Tare weight T | t | 19 | 17.480 | 17.573 | 17.568 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoilov, V.; Purgic, S. Optimization of the Technical Parameters of Universal Freight Wagons. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12673. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312673

Stoilov V, Purgic S. Optimization of the Technical Parameters of Universal Freight Wagons. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12673. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312673

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoilov, Valeri, and Sanel Purgic. 2025. "Optimization of the Technical Parameters of Universal Freight Wagons" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12673. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312673

APA StyleStoilov, V., & Purgic, S. (2025). Optimization of the Technical Parameters of Universal Freight Wagons. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12673. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312673