Abstract

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) compromises executive control, yet brief exercise may yield acute cognitive benefits. We tested whether a single ~10 min bout of physical, cognitive, or combined physical-cognitive exercise modulates Stroop performance in older adults with MCI (MoCA) under heightened postural demand (tandem stance). In a within-subject design (n = 28), participants completed three sessions: physical, cognitive, and combined physical-cognitive exercise protocols. Stroop performance was tested seated and in tandem stance pre-exercise (order counterbalanced) and again in tandem stance post-exercise. Pre- and post-exercise physiological markers (heart rate, blood pressure, SpO2, glucose) and workload (NASA-TLX) were recorded; balance was assessed with a 30 s Tandem Stance Test. Posture (seated vs. tandem) did not affect baseline Stroop levels. Across sessions, Stroop performance improved acutely after the physical and cognitive exercises—most robustly after the physical testing—whereas the combined condition produced the smallest changes. The physical and combined sessions increased heart rate and systolic pressure; SpO2, diastolic pressure, glucose, NASA-TLX, and tandem-stance balance were unchanged among all sessions. These results indicate that a single light- to moderate-intensity session can acutely enhance executive function for MCI and that a challenging posture does not impose any dual-task cost. Furthermore, single-task exercise may be more effective for rapid cognitive gains than combined mental and physical protocols in individuals with MCI.

1. Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a prevalent prodromal stage of dementia marked by deficits in memory, attention, executive function, and information-processing speed [,]. Selective attention and processing speed are particularly important because they determine how effectively older adults can interpret and respond to environmental demands [] and may be partly preserved through cognitive reserve mechanisms [,]. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies have shown that MCI involves neuronal loss, synaptic dysfunction, and disrupted frontoparietal connectivity [,], all of which impair executive control. Yet, recent evidence suggests that these deficits can be partly compensated for. In detail, Fan et al. (2025) [] showed, using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), that individuals with MCI maintain near-normal performance by recruiting additional prefrontal and parietal regions during demanding executive tasks such as the Stroop test. Such compensatory activation suggests that MCI patients may preserve executive performance under low-demand conditions, particularly when seated []. Although sitting is common in daily life, many functional and cognitively demanding activities occur while standing or moving, engaging both balance and executive control. Maintaining balance during standing tasks engages continuous sensorimotor integration and executive resources []. Challenging postures such as tandem stance, i.e., one foot placed directly in front of the other, are expected to increase postural sway and attentional cost relative to sitting or normal standing. According to the posture-first principle, when attentional resources are limited, the nervous system prioritizes balance over concurrent cognitive tasks []. Recent findings indicate that depending on the individual characteristics that influence the postural load experienced by a person, standing posture may have a positive, detrimental, or no effect on cognitive control [,]. Against this background, testing Stroop performance during a more demanding balance condition, e.g., tandem stance, offers a way to examine how heightened postural challenge interacts with executive function in older adults with MCI.

The Stroop test, which assesses selective attention and the ability to inhibit competing stimuli [,], is well suited to investigate these mechanisms. Acute interventions may modulate Stroop performance, reflecting short-term changes in attention and executive control. For example, a single bout of dynamic sitting exercise improved Stroop outcomes and sleep quality in older adults with cognitive impairment []. Both physical and cognitive training provide neuroprotective effects: physical exercise improves cerebral blood flow and enhances executive function [], while cognitive training strengthens attentional networks []. Previous studies in heathy older adults have shown that a single session of cognitive exercise is effective in improving executive performance [,]. Nevertheless, in older adults with MCI, who already exhibit reduced cognitive reserve [], acute cognitive activity could temporarily deteriorate subsequent executive performance []. Sustained mental workload may increase sympathetic activation and cerebral oxygen demand, leading to transient fatigue and reduced attentional capacity []. Furthermore, while a combined physical-cognitive exercise task has been proven to be effective in healthy older adults [,], there is no evidence in the literature that these acute effects extend to individuals with MCI. Existing studies in this population have focused primarily on long-term cognitive or combined physical-cognitive interventions, which are generally associated with cognitive benefits [,,].

To the best of our knowledge, there is gap in literature on how postural challenge modifies these acute exercise effects. Previous studies on cognitive-motor interference in MCI have mainly examined walking or simple standing tasks, whereas few have investigated whether executive performance is preserved when attention is taxed by a more destabilizing posture such as a tandem stance. Thus, it remains unclear whether a single session of cognitive or combined physical-cognitive exercise acutely enhances or impairs attentional resources and executive performance, particularly when performed concurrently with a demanding motor task.

This study aims to investigate whether a single session of physical, cognitive, or combined physical-cognitive exercise modulates Stroop performance in older adults with MCI when the test is performed in a tandem stance, a condition of heightened postural demand. Because acute exercise can transiently modify heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and blood glucose, all of which are closely linked to cerebral metabolism and cognitive performance [,,,], these physiological markers were monitored together with Stroop outcomes. Measuring them alongside cognitive outcomes provides a multidimensional view of how different exercise modalities influence brain function []. Based on evidence that postural control and executive function compete for shared attentional resources [,,] and that MCI involves reduced cognitive reserve despite brain compensatory activation [,], we hypothesized that performing the Stroop test in tandem stance would impair performance, particularly in the interference condition. We further expected that physical exercise may momentarily increase postural demand during tandem stance due to fatigue. Accordingly, we hypothesized that (a) physical exercise will acutely enhance Stroop performance, most notably in the interference condition, reflecting short-term facilitation of prefrontal executive function []; (b) cognitive exercise alone will impair Stroop performance during a tandem stance, because the prior mental workload may temporarily deplete attentional resources and induce fatigue, thereby limiting the capacity to cope with a concurrent balance challenge [,]; (c) combined physical-cognitive exercise will produce no significant changes in Stroop performance, because in individuals with MCI the cognitive component may induce a transient fatigue that counteracts the facilitative effects of physical exercise, while the increased postural demand resulting from physical fatigue may further attenuate potential benefits, leading to no observable improvement in executive function.

The findings of the present study will contribute to understanding the capacity of older adults with MCI to preserve Stroop performance under increased balance demands. This knowledge is essential for designing physical and combined physical-cognitive exercise protocols that effectively enhance cognition while ensuring postural safety and reducing fall risk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-eight older adults (14 women, 14 men) with MCI as well as a mean age of 73.29 ± 6.81 years and body mass index of 28.58 ± 3.39 participated in the study. All were functionally independent and did not report any chronic health conditions that could interfere with movement or balance, such as neurological disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease or stroke), serious musculoskeletal problems, or poorly controlled cardiovascular or metabolic diseases. Eligibility was confirmed through medical history, standardized cognitive (Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] score 17–25) and motor assessments (Berg Balance Scale score above 45). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the study aims and procedures. Ethical approval was granted by the Local Ethics Research Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sport Science at Serres Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Approval No. ERC-012/2024).

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Executive Function

Executive function, selective attention, and processing speed were measured with the Stroop Color-Word Test following the adaptation described in [] In the most common version of the Stroop test, originally proposed by Stroop in 1935 [], participants are required to correctly identify as many items as possible in 45 s across three conditions. The first two conditions represent a “congruent” context: (a) the Word Reading condition (W), in which participants read color names printed in black ink, and (b) the Color Naming condition (C), in which they name the color of solid-colored squares. The third condition represents an incongruent context, the Color-Word (interference) condition (CW), where a color word appears in a mismatched ink color (e.g., the word “red” printed in green). In this condition, participants must inhibit the automatic response of reading the word and instead name the ink color.

The predicted CW score (Pcw) is calculated as

where W and C are the count of correct items in word reading and color naming during the congruent conditions of the Stroop test, respectively.

The interference score (IG) was derived as

where CW is the count of selected words that were consistent with the shown colors during the incongruent condition of the Stroop test. A negative IG value represents a pathological ability to inhibit interference, with lower scores indicating greater difficulty in interference inhibition [].

2.2.2. Perceived Exertion

Exercise intensity was monitored with the standardized Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale (RPE) []. This is a useful tool for assessing physical exertion levels and even fatigue based on an individual’s perceived effort during exercise. The scale ranges from 6 to 20, with the lowest value (6) representing “no effort” and the highest value (20) indicating “extremely maximal effort” [,].

2.2.3. Workload Assessment

Perceived task load was measured with the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), which provides a weighted overall workload score from six subscales: mental, physical, and temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration []. Higher scores reflect greater perceived workload.

2.3. Physiological Markers

Blood glucose (mg/dL) was assessed with a portable glucose meter (ControlBios TD-4277, New Taipei City, Taiwan). Heart rate (HR) and oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded with a finger pulse oximeter (Medisana, PM 100, GmbH 41460, Neuss, Germany). Systolic blood pressure (SBD) as well as diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were assessed via an automated sphygmomanometer (Omron M2 Basic Hem 7121J-E, Omron Healthcare Co., Kyoto, Japan).

2.3.1. Measurement Procedure

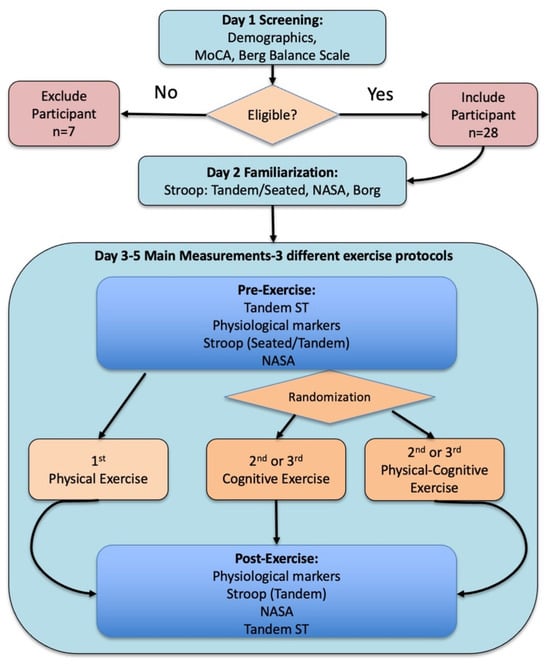

Data collection was conducted on four separate days, in addition to one familiarization session held prior to the main measurements (Figure 1). On Day 1, participants completed a demographic questionnaire and underwent cognitive (MoCA) and balance (Berg Balance Scale) assessments. A total of 35 older adults were initially approached from the local community through simple notices and referrals from local senior centers. After the screening process, 28 people met the criteria and agreed to participate in the study.

Figure 1.

Measurement procedure overview: The measurement procedure included three main stages: (i) participant screening (demographics, MoCA, Berg Balance Scale, and eligibility confirmation), (ii) familiarization with the Stroop test, NASA-TLX, and Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), and (iii) main measurements: pre- and post-exercise assessments of balance (Tandem Stance Test, Tandem ST), cognitive performance (Stroop test), perceived workload (NASA) and physiological markers (SpO2, HR, BP, Glu). The physical exercise protocol was always completed first to determine the exercise protocol duration, whereas the cognitive exercise and combined physical–cognitive exercise protocols were performed in a randomized order. During each experimental session, participants completed the following sequence: (1) Tandem Stance Test, (2) Stroop test in seated position, (3) physiological markers assessment, (4) Stroop test in tandem stance (the order of tests 2 and 4 was randomized), (5) NASA-TLX (always after the Stroop test in tandem stance), (6) exercise protocol, (7) physiological markers assessment, (8) Stroop test in tandem stance, (9) NASA-TLX, and (10) Tandem Stance Test.

On a separate day (Day 2), a familiarization session was conducted to introduce the NASA-TLX workload scale, the Borg perceived exertion scale, and the Stroop test. Participants practiced each assessment to ensure comprehension. The Stroop test was performed multiple times, both in a seated position and tandem stance, to minimize learning effects during the experimental sessions (Figure 1).

The main measurements were then performed on three additional days (Days 3–5). In each session, participants performed the Stroop test both before and immediately after one of the three exercise protocols—physical exercise, cognitive exercise, and combined physical-cognitive exercise—in randomized order, with at least three days between sessions to allow recovery and avoid carryover effects.

Before each exercise protocol, the Stroop test was administered under two conditions, seated and tandem stance, with the order counterbalanced between participants to control for order effects. Immediately after each exercise protocol, the Stroop test was administered only in the tandem stance condition. Furthermore, in both the pre- and post-exercise assessments, physiological data (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation [SpO2], and blood glucose levels) were recorded immediately before the Stroop test, and the NASA-TLX workload questionnaire was completed immediately after the Stroop test while participants remained in a tandem stance (Figure 1).

Finally, balance was assessed before and after each exercise protocol using the 30 s Tandem Stance Test [], scored from 0 (unable to maintain stance) to 5 (stable balance with minimal sway) (Table 1). This assessment provided additional information on whether fatigue or postural instability influenced post-exercise Stroop performance. Τhe post-exercise balance test was conducted after the Stroop assessment, approximately 3–5 min following the end of the exercise.

Table 1.

Score description of the Tandem Stance evaluation [].

2.3.2. Exercise Protocol

All participants first completed a physical exercise session to determine the individualized exercise duration. This duration was then applied to all three exercise protocols. The order of the subsequent cognitive and combined physical-cognitive exercise sessions was randomized to control for possible order effects (e.g., learning, fatigue, and adaptation) and ensure that any differences in outcomes were attributable to the exercise condition rather than the sequence of administration.

2.4. Physical Exercise

The first session consisted solely of a physical exercise task. Participants alternated 45 s of on-the-spot walking at a comfortable, self-selected pace, with five sit-to-stand repetitions from a chair without armrests, with heart rate and oxygen saturation continuously monitored throughout the session. Exercise duration was individualized, and participants used Borg’s Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale (6–20) to maintain light to moderate intensity (≤12, ≈60–65% HRmax). Heart rate and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored throughout the session. Exercise was terminated if participants (i) reported an RPE > 12, (ii) could not maintain correct movement form, (iii) showed abnormal cardiovascular responses (HR > 85% HRmax, or SpO2 < 90%), or (iv) experienced dizziness, chest discomfort, or other adverse symptoms.

2.5. Cognitive Exercise

In the cognitive exercise session, participants remained seated to minimize physical fatigue and completed four distinct cognitive tasks:

- Category verification: raise a hand when an incorrect item was named within a category, e.g., a non-fruit under “fruits” or a lake under “cities”.

- Arithmetic calculations: raise hand for incorrect calculations.

- Letter recognition: raise a hand, when a presented word began with a different letter than specified.

- Contextual categorization: raise a hand when the item did not belong in a given context, e.g., an object not found in a living room.

No verbal responses were used to avoid respiratory interference in the combined physical-cognitive session. Session duration matched that of the physical exercise. Physiological parameters and perceived exertion (Borg scale) were assessed to ensure consistency between sessions.

2.6. Combined Physical and Cognitive Exercise

This session integrated both components. Participants performed the physical exercise task (repetitive sets of the 45 s on-the-spot walking with the five sit-to-stand repetitions) while completing the same cognitive tasks as above. The total duration and walking tempo were aligned with that of the physical exercise task. Heart rate and SpO2 were continuously monitored, and Borg RPE was recorded to index perceived exertion.

Throughout all three sessions, exercise intensity and duration were individualized based on initial testing and participants’ subjective fatigue to maintain protocol consistency and ensure safety.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 29.0.2.0 (20). Descriptive statistics are presented as means and standard deviations (x ± SD). Normality of data distribution was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variances with Levene’s test. To examine the effect of posture (seated vs. Tandem Stance) on Stroop performance, a paired-sample t-test was conducted. To examine the effect of exercise on Stroop performance and physiological outcomes, a two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA was applied with the following within-subject factors: (1) time (comparison between pre- and post-exercise measurements, reported in results and discussion as exercise effect) and (2) type of exercise protocol (comparison among the three exercise protocols: physical, cognitive, and combined physical-cognitive). When a significant interaction between effect of time and type of exercise protocol was detected, pairwise post hoc comparisons were conducted using paired-sample t-tests to compare pre- and post-exercise values within each exercise condition. The Benjamini–Hochberg correction was subsequently applied to control the false discovery rate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). Effect sizes were reported as Cohen’s d for pairwise comparisons and as partial eta squared (η2) for ANOVA effects.

3. Results

The mean MoCa score was 20.25 ± 3.43, indicating mild cognitive impairment among the participants. The mean Berg Balance Scale score was 53.54 ± 3.26, consistent with a low risk of falls and functional independence. All participants performed the physical and cognitive tasks successfully. The mean duration of exercise was 9.32 ± 2.96 min.

3.1. Effect of Posture on Stroop Performance

Posture (seated vs. tandem stance) had no effect on Stroop Test Performance, with no differences for any outcome measures. During the reading condition, the number of words correctly read was 76.75 ± 17.30 in the seated position and 73.93 ± 19.06 in the tandem stance (t(27) = 0.93, p = 0.359). During the color-naming condition, the number of correctly named colors was 55.79 ± 15.59 in the seated position and 53.60 ± 13.74 in the tandem stance (t(27) = 0.65, p = 0.519). During the interference condition, the number of correctly named words was 27.25 ± 9.63 in the seated position and 24.36 ±10.08 in the tandem stance (t(27) = 1.28, p = 0.211). Τhe Pcw value was 31.55 ± 6.93 and 30.65 ±7.20, (t(27) = 0.81, p = 0.427), and the interference score was −4.3 ±10.18 and −6.3 ± 7.57, (t(27) = 0.89, p = 0.383) for the seated and tandem stance, respectively. Τhe overall score of NASA-TLX was 61.05 ± 9.67 in the seated position and 63.95 ± 9.93 in the tandem stance (t(27) = 0.93, p = 0.359). None of the six NASA-TLX subscales showed significant differences between the two postures.

3.2. The Effect of Exercise on Stroop Performance

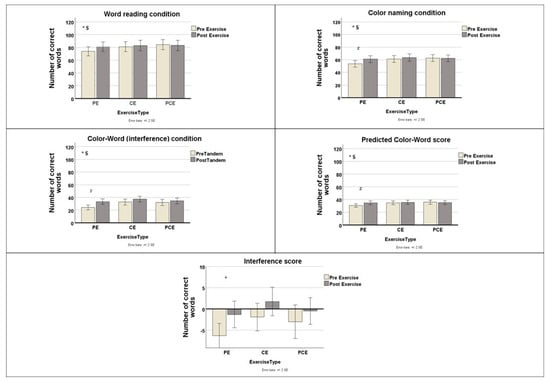

During the reading condition, the number of words read was 73.93 ± 19.06 before the physical exercise and 81.07± 19.30 after it; 81.00 ± 20.37 before the cognitive exercise and 82.86 ± 21.84 after it; and 84.36 + 21.09 before the physical-cognitive exercise and 83.07 ± 21.17 after it. There was no significant main effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 3.07, p = 0.091, partial η2 = 0.102. However, a significant interaction effect was found between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(2, 54) = 3.43, p = 0.040, partial η2 = 0.113 (Figure 2). Post hoc analyses using paired-samples t-tests comparing pre- and post-exercise scores revealed no significant differences after Benjamini–Hochberg correction for the physical exercise [t(27) = −2.30, BH-adjusted p = 0.090, d = 0.43], cognitive exercise [t(27) = −0.95, BH-adjusted p = 0.524, d = 0.18], or physical-cognitive exercise [t(27) = 0.68, BH-adjusted p = 0.503, d = 0.13].

Figure 2.

Mean ± standard deviation values of Stroop task performance during tandem stance before (white bars) and after (gray bars) exercise across the three exercise types: Physical Exercise (PE), Cognitive Exercise (CE), and Physical-Cognitive Exercise (PCE). White bars represent pre-exercise data, and gray bars represent post-exercise. * Statistically significant main effect of exercise (p < 0.05). $ Statistically significant interaction between effect of exercise and type of exercise protocol (p < 0.05). # Statistically significant pre–post differences within each exercise type (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected, p < 0.05).

During the color-naming condition, the number of correctly named colors was 53.61 ± 13.74 before the physical exercise and 61.00 ± 14.24 after it; 61.36 ± 14.58 before the cognitive exercise and 63.46 ± 15.42 after it; and 62.78 ± 14.53 before the physical-cognitive exercise and 62.18 ± 13.92 after it. There was a statistically significant effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 8.057, p = 0.009, η2 = 0.230 (Figure 2). Additionally, a significant interaction effect was found between the type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(1.516, 40.932) = 4.16, p = 0.032, η2 = 0.134. Post hoc analyses using paired-sample t-tests comparing pre- and post-exercise values revealed a significant improvement in the color-naming condition only after the physical exercise [t(27) = −2.84, BH-adjusted p = 0.024, d = 0.54] but not after cognitive exercise [t(27) = −1.29, BH-adjusted p = 0.309, d = 0.25] or physical-cognitive exercise [t(27) = 0.452, BH-adjusted p = 0.655, d = 0.009].

During the interference condition, the number of corrected words was 24.36 ± 10.08 before the physical exercise and 33.36 ± 11.31 after it; 32.75 ± 12.22 before the cognitive exercise and 37.36 ± 11.86 after it; and 32.11 ± 13.02 before the physical-cognitive exercise and 34.64 ± 12.49 after it. There was a statistically significant main effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 25.501, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.486. Further, a statistically significant interaction effect was found between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(1.45, 39) = 4.206, p = 0.033, partial η2 = 0.135 (Figure 2). Post hoc analyses using paired-sample t-tests comparing pre- and post-exercise values revealed significant differences after physical exercise [t(27) = −4.21, BH-adjusted p = 0.003, d = 0.80] and after cognitive exercise [t(27) = −3.89, BH-adjusted p = 0.003, d = 0.74] but not after physical-cognitive exercise [t(27) = −1.57, BH-adjusted p = 0.128, d = 0.30].

Τhe Pcw values were 30.65 ± 7.20 before the physical exercise and 34.65 ±7.91 after it; 34.66 ± 8.04 before the cognitive exercise and 35.61 ± 8.64 after it, and 35.74 ± 8.18, before the physical-cognitive exercise and 35.14 ± 7.86 after it. There was a statistically significant main effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 5.991, p < 0.021, partial η2 = 0.182. Also, a significant interaction effect was found between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(1.49, 40.11) = 6.632, p < 0.007, η2 = 0.197 (Figure 2). Post hoc analyses using paired-sample t-tests comparing pre- and post-exercise values revealed significant differences only after the physical exercise [t(27) = −2.84, BH-adjusted p = 0.008, d = 0.59] but not after cognitive exercise [t(27) = −1.225, BH-adjusted p = 0.231, d = 0.23] or physical-cognitive exercise [t(27) = 0.875, BH-adjusted p = 0.389, d = 0.17].

The interference score was −6.3 ± 7.57 before the physical exercise and −1.3 ± 8.35 after it; −1.9 ± 8.59 before the cognitive exercise and 1.75 ± 8.87 after it; and −3.03 ± 10.47 before the physical-cognitive exercise and −0.5 ± 8.25 after it. There was a statistically significant effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 16.086, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.373 (Figure 2). However, no significant interaction effect was found between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(1.61, 43.64) = 0.641, p = 0.5, partial η2 = 0.023.

There was no significant main effect of exercise on self-corrected errors or examiner-corrected errors across all Stroop test conditions.

3.3. Subjective Cognitive Workload NASA-TLX

There was no significant main effect of exercise on subjective cognitive workload, as measured by the total NASA-TLX score or any of its six subscales: Total NASA-TLX F(1, 27) = 0.234, p = 0.633, partial η2 = 0.009; Mental Demand F(1, 27) = 0.375, p = 0.546, partial η2 = 0.014; Physical Demand F(1, 27) = 2.395, p = 0.133, partial η2 = 0.081; Temporal Demand F(1, 27) = 0.049, p = 0.827, partial η2 = 0.002; Performance F(1, 27) = 0.00, p = 1.000, partial η2 =0.000; Effort F(1, 27) = 2.848, p = 0.103, partial η2 = 0.095; and Frustration F(1, 27) = 0.031, p = 0.862, partial η2 = 0.001 (Table 2). Moreover, no significant interaction was found between exercise and type of exercise protocol for any NASA-TLX dimension.

Table 2.

NASA-TLX scores (mean ± SD) across dimensions and type of exercise protocol.

Despite the absence of significant differences, the overall NASA-TLX scores (~60–63 across exercise types) suggest that participants perceived the Stroop task as imposing a moderate to high cognitive workload, with consistently elevated ratings for mental demand, effort, and physical demand. These results indicate that while exercise did not alter the perceived workload, the task itself was cognitively challenging for the participants.

3.4. Effect of Exercise on Tandem Stance Balance Performance

Balance performance scores during the tandem stance were 4.82 ± 0.55 before the physical exercise and 4.82 ± 0.61 after it; 4.79 ± 0.69 before the cognitive exercise and 4.93 ± 0.26 after it; and 4.75 ± 0.70 before the physical-cognitive exercise and 4.71 ± 0.71 after it.

There was no significant main effect of exercise on balance performance, F(1, 27) = 0.383, p = 0.541, partial η2 = 0.014. Furthermore, there was no significant interaction effect between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(1.31, 35.23) = 0.802, p = 0.454, partial η2 = 0.029.

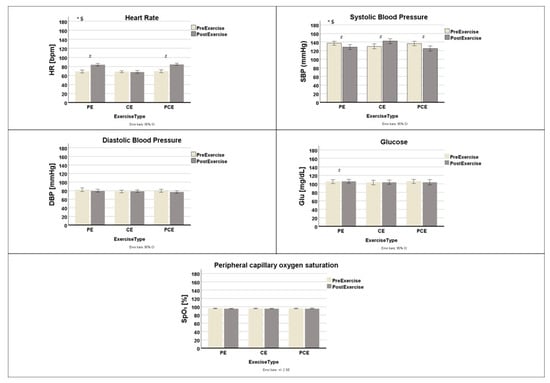

3.5. Effect of Exercise on Heart Rate

The heart rate was 68.82 ± 7.83 bpm before the physical exercise and 83.5 ± 7.42 bpm after it; 68.18 ± 6.04 bpm before the cognitive exercise and 67.93 ± 7.41 bpm after it; 69.07 ± 8.07 bpm before the physical-cognitive exercise and 84.54 ± 6.19 bpm after it (Figure 3). There was a significant effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 90.816, p ≤ 0.001, partial η2 = 0.771. Also, there was a significant interaction between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(1.57, 42.51) = 31.555, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.539. Post hoc paired-sample t-tests comparing pre- and post-exercise heart rate showed significant increases following both physical exercise (t(27) = −7.799, BH-adjusted p = 0.003, d = 1.47) and physical-cognitive exercise (t(27) = −8.237, BH-adjusted p = 0.003, d = 1.55). In contrast, no significant change in heart rate was observed after the cognitive exercise (t(27) = 0.23, BH-adjusted p = 0.82, d = 0.01).

Figure 3.

Mean ± standard deviation values of physiological markers (heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and blood glucose) measured before (white bars) and after (gray bars) each exercise session: Physical Exercise (PE), Cognitive Exercise (CE), and Physical-Cognitive Exercise (PCE). White bars represent pre-exercise measurements, and gray bars represent post-exercise measurements. * Statistically significant main effect of exercise (p < 0.05). $ Statistically significant interaction between effect of exercise and type of exercise protocol (p < 0.05). # Statistically significant pre–post differences within each type of exercise protocol (Benjamini–Hochberg corrected, p < 0.05).

3.6. Effect of Exercise on Blood Pressure (SBP/DBP)

SBP values were 137.25 ± 12.46 mm Hg before physical exercise and 142.29 ± 14.92 mm Hg after it; 130.07 ± 14.43 mm Hg before cognitive exercise and 124.93 ± 14.91 mm Hg after it; 128.43 ± 14.92 mm Hg before physical-cognitive exercise and 136.43 ± 13.35 mm Hg after it (Figure 3). There was a significant main effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 5.04, p = 0.033, partial η2 = 0.157, and a significant interaction between exercise and type of exercise protocol, F(2, 54) = 10.52 p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.280. Post hoc analysis using paired-sample t-tests comparing pre- and post-exercise values revealed significant increases in SBP after physical [t(27) = −2.49, BH-adjusted p = 0.019, d = −0.47] and physical-cognitive exercise [t(27) = 2.66, BH-adjusted p = 0.02, d = 0.50]. In contrast, a significant decrease in SBP was observed after cognitive exercise [t(27) = −3.47, BH-adjusted p = 0.006, d = −0.66].

DBP values were 82.36 ± 10.57 mm Hg before physical exercise and 80.21 ± 8.63 mm Hg after it; 78.14 ± 7.93 mm Hg before cognitive exercise and 78.96 ± 7.13 after it; 79.57 ± 9.33 mm Hg before physical-cognitive exercise and 77.07 ± 7.71 mm Hg after it (Figure 3). There was no effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 3.16, p = 0.086, partial η2 = 0.105.

3.7. Effect of Exercise on Blood Glucose

The mean pre-exercise blood glucose values were 105.46 ± 12.56 mg/dL before physical exercise, 103.21 ± 14.11 mg/dL before cognitive exercise, and 106.04 ± 12.43 mg/dL before combined physical–cognitive exercise. Following the exercise protocols, the corresponding values were 106.04 ± 11.69 mg/dL, 104.07 ± 12.71 mg/dL, and 103.75 ± 15.90 mg/dL, respectively (Figure 3). There was no significant effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 0.068, p = 0.797, and no interaction between type of exercise protocol and exercise, F(2, 54) = 1.021, p = 0.367.

3.8. Effect of Exercise on Oxygen Saturation (SpO2)

SpO2 values were (95.71 ± 1.94)% before physical exercise and (95.36 ± 1.73)% after it; (95.57 ± 2.08)% before cognitive exercise and (95.32 ± 1.85)% after it; (95.43 ± 2.17)%, before physical-cognitive exercise and (95.43 ± 2.10)% after it (Figure 3). There was no significant effect of exercise, F(1, 27) = 2.31, p = 0.140, partial η2 = 0.079. Furthermore, no significant interaction was found between exercise and type of exercise protocol, F(2, 54) = 0.543, p = 0.584, partial η2 = 0.020.

4. Discussion

This study examined the acute effects of three exercise types, physical, cognitive, and combined physical-cognitive, on executive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Despite their cognitive deficits, participants demonstrated good balance, as indicated by their Berg Balance Scale score (53.54 ± 3.26). Notably, the more challenging tandem stance did not impair Stroop performance compared to the seated condition, suggesting that postural demands did not exacerbate cognitive interference in this population, rejecting our initial hypothesis. It is possible that compensatory neural mechanisms described in previous imaging studies [] may help preserve executive control even under increased postural load.

Overall, the results partly supported our hypotheses regarding the impact of exercise on Stroop performance. Consistent with exercise-induced facilitation, Stroop performance improved significantly after physical and cognitive exercise, with the largest and most consistent gains observed after physical exercise. Contrary to our expectation of mental fatigue, cognitive exercise led to selective improvements rather than deterioration in performance. In line with our final hypothesis, the combined physical-cognitive exercise yielded the smallest effects. Across all conditions, perceived workload (NASA-TLX) and tandem-stance balance remained unchanged. Taken together, these findings indicate that a single ~10 min bout of light- to moderate-intensity exercise can acutely enhance executive function in older adults with MCI and that the anticipated dual-task cost of a challenging posture did not emerge in this cohort.

4.1. Effect of Physical Exercise

A brief session (~10 min) of light-to-moderate physical exercise improved Stroop performance, particularly in the naming and interference conditions. In agreement with our findings, previous studies have found that physical activity can acutely enhance prefrontal executive functions, especially those related to inhibition and selective attention in individuals with MCI [], in healthy older adults []. The cognitive gains after the examined physical exercise were accompanied by physiological activation, as shown by the increases in heart rate and systolic blood pressure, while oxygen saturation, diastolic blood pressure, and blood glucose remained stable. This physiological profile is consistent with previously reported acute-exercise responses. Increased heart rate and systolic blood pressure reflect enhanced cardiac output and possibly increased cerebral perfusion, mechanisms known to facilitate cortical processing and to stimulate the release of neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which support neuroplasticity and executive control [,,]. Furthermore, evidence in healthy adults has shown that even 15 min of postprandial exercise may be too short to lower the glycemic peak []; thus, our average 9 min, modest-intensity physical exercise likely fell below the threshold needed to lower glucose meaningfully. The maintenance of SpO2 and blood glucose following the light-to-moderate exercise indicates that oxygen and glucose delivery to the brain remained adequate. Such responses suggest that the exercise stimulus was sufficient to induce systemic physiological changes that could potentially support enhanced cerebral perfusion [], providing a plausible explanation for the observed Stroop performance improvements.

NASA-TLX scores confirmed that perceived mental demand was unaffected, supporting the view that the improved Stroop performance reflected more efficient neural processing rather than a reduction in task difficulty or an increase in mental effort. Balance stability further indicates that physical exercise protocol did not induce postural fatigue.

4.2. Effect of Cognitive Exercise

Contrary to our initial expectation, cognitive exercise alone did not impair Stroop performance; instead it was followed by a measurable improvement, suggesting that a single ~10 min moderate-difficulty mental task can acutely prime attentional control and conflict resolution in MCI. Similar rapid benefits after short cognitive challenges have been described for healthy adults, possibly due to acutely heightened alertness and prefrontal activation []. Physiologically, cognitive exercise elicited only minimal systemic change: heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood glucose, and oxygen saturation remained stable, in line with reports that purely cognitive tasks produce little cardiovascular or metabolic activation []. This confirms that the task did not impose substantial cardiovascular or metabolic load. Furthermore, subjective workload, as measured by NASA-TLX, showed no significant changes after cognitive exercise. Improved Stroop performance with unchanged NASA-TLX ratings implies improved neural efficiency. Participants performed better without perceiving the task as more demanding, an important consideration for individuals with limited cognitive reserve.

Consequently, it seems that a single short cognitive session can acutely facilitate selective attention in older adults with MCI while avoiding the resource depletion and transient fatigue sometimes reported after prolonged mental effort []. Previous studies in healthy older adults found that a single 15 to 30 min session of cognitive exercise significantly improves the performance of an executive task [,]. In this way, such brief interventions may extend the well-established long-term benefits of cognitive training [] into an acute context, offering a rapid and practical means to prime executive control [].

4.3. Effect of Combined Physical-Cognitive Exercise

The combined physical-cognitive exercise session produced modest but non-significant Stroop improvements that did not surpass those achieved by physical or cognitive exercise alone. Neither the color-naming nor interference conditions showed significant post-exercise gains.

Physiological responses mirrored those of physical exercise, confirming that the systemic stimulus was primarily physical. As in the physical exercise condition, combined physical-cognitive exercise elicited significant elevations in heart rate and systolic blood pressure, confirming a robust cardiovascular response consistent with transient increases in cerebral blood flow and neurotrophic factor release such as BDNF and IGF-1 [,,]. Oxygen saturation, diastolic blood pressure, and blood glucose remained stable, a pattern expected after brief light-to-moderate activity, and possibly suggest adequate oxygen and substrate delivery to the brain.

The added cognitive load neither amplified physiological activation nor improved executive outcomes. Two mechanisms may explain the attenuated cognitive gain: resource competition, where concurrent motor and cognitive demands tax shared neural networks and limit net improvement, and subtle fatigue, whereby added mental load offsets the arousal-related facilitation of exercise. Dual-task research shows that MCI populations frequently display larger interference effects when motor and cognitive demands approach their attentional capacity [,]. These factors likely diluted the acute benefits of physical-cognitive exercise despite its adequate cardiovascular stimulus.

Subjective workload ratings (NASA-TLX) also remained stable, suggesting that participants perceived the Stroop task as equally demanding before and after exercise and that the dual-modality stimulus did not increase conscious effort. Balance performance was unaffected, suggesting that the concurrent cognitive challenge did not destabilize postural control or induce fatigue—an important consideration for older adults with MCI.

4.4. Comparison Between Exercise Protocols

In older adults with MCI, acute improvements in executive control are most reliably achieved through physical exercise. Cognitive exercise can also provide selective gains, whereas combined physical-cognitive exercise appears to require careful tailoring of task complexity to prevent cognitive overload. The absence of Stroop improvement after the combined protocol—despite clear benefits from physical and cognitive exercises individually—highlights a potential limitation of simultaneous physical-cognitive interventions, particularly when cognitive testing is performed under a challenging posture such as a tandem stance. Although previous studies in healthy adults have shown that acute combined exercise at light to moderate intensity has a general facilitative effect on cognitive performance and is superior to a single-task exercise [,], the present results indicate that this may not apply to individuals with MCI. In this population, concurrent physical and cognitive demands may compete for shared attentional or neural resources, thereby limiting performance enhancement. Importantly, none of the protocols increased perceived mental demand or reduced the ability to maintain a tandem stance. These findings underscore the importance of individually tailoring exercise programs for older adults with MCI—optimizing intensity, cognitive load, and postural challenge—to maximize cognitive benefits while minimizing fatigue or interference effects.

A potential limitation of the present study is that the physical exercise protocol used to determine the duration of the other two exercise protocols was always performed first. Although the sequence of the remaining two protocols was randomized, this design choice could have introduced baseline differences in Stroop performance across exercise sessions, despite the familiarization session that was implemented to minimize such effects. However, repeated-measures analyses of the pre-exercise Stroop values showed no significant differences in the number of correctly named words for the color and word conditions between sessions. In the color-word (interference) condition, the number of the correctly named words as well as both the Pcw and IG scores showed a significant effect of session timing, suggesting some variation across trials. Nevertheless, when controlling for pre-exercise performance using ANCOVA, no significant differences were found between exercise types. Similarly, when the relative change [(post − pre)/pre × 100] was analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA, no significant differences emerged. These findings suggest that the potential influence of baseline variation on the observed exercise effects was minimal.

A further limitation could be that balance was evaluated 4–5 min after the end of the exercise protocol; therefore, any fatigue-related deterioration in balance performance may have subsided by the time of assessment. Nevertheless, previous studies indicate that fatigue-related reductions in muscle strength can persist for up to 10 min post-exercise []. Thus, although the possibility of transient balance deficits cannot be entirely ruled out, it is likely that any such effects would still have been present 3–5 min after exercise cessation.

The modest sample size (N = 28) could be a factor affecting the main outcome of the present study. However, the within-subject repeated-measures design substantially increased statistical power by minimizing inter-individual variability. Post hoc analyses in G*Power 3.1 confirmed that the study achieved excellent power (1 − β ≥ 0.99) for the main time effects and the time × type of exercise protocol interactions across the reading, naming, and color-word Stroop conditions. Only the interference index interaction showed moderate power (1 − β = 0.49) due to its small observed effect size. Overall, the design provided adequate sensitivity to detect the primary within-subject effects. However, caution is warranted when generalizing the findings.

This study was conducted at the overall sample level and did not account for individual differences, such as the degree of cognitive impairment or baseline fitness. Given the heterogeneity of MCI, these factors may influence how older adults respond to different types of exercise. Although inclusion criteria ensured general comparability, we cannot exclude the possibility of intrasubject variability, which could affect our main outcomes. However, repeated-measures ANCOVAs controlling for the MoCA score confirmed that cognitive level did not significantly moderate Stroop performance changes across exercise conditions. Significant or trend-level time effects remained, while all MoCA-related interactions were non-significant (p > 0.24). This indicates that improvements in Stroop performance were primarily driven by within-subject effects of exercise and that these improvements appeared consistent across participants, regardless of their individual cognitive status. Future studies should consider classifying participants into MCI subgroups to better understand how individual variation affects cognitive outcomes.

An additional limitation could be daily exercise and dietary habits, which are known to affect both cognitive and physiological responses. Although none of the participants were involved in systematic training and reported similar activity levels, and although we asked them to maintain their usual routines and avoid caffeine, alcohol, and strenuous activity on the day of testing, these factors could not be directly controlled. Future studies should consider monitoring or documenting participants’ daily habits to better isolate the effects of acute exercise.

5. Conclusions

The present findings suggest that a single ~10 min bout of light- to moderate-intensity exercise can acutely enhance executive function in MCI and that the anticipated dual-task cost of a challenging posture was not observed in this cohort. The magnitude of this enhancement depended on the type of exercise protocol: physical exercise showed the most consistent acute improvements in Stroop performance, cognitive exercise provided selective facilitation, and combined physical-cognitive exercise was the least effective. These findings indicate that more complex, dual-task exercise protocols are not necessarily better for acute cognitive benefits in older adults with MCI. Brief, single-task exercise may be more effective for rapid cognitive gains than combined mental and physical protocols. Nevertheless, further intervention studies are needed to determine the appropriate training program to obtain sustained benefits in cognition in individuals with MCI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and E.G.; methodology, L.M., E.G., K.D. and D.A.P.; software, L.M. and E.G.; validation, L.M., E.G., K.D. and D.A.P.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, L.M., E.G., K.D. and D.A.P.; resources, L.M.; data curation, E.G. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.; writing—review and editing, L.M., E.G., K.D. and D.A.P.; visualization, E.G. and L.M.; supervision, L.M.; project administration, L.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received to support this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Ethics Research Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sport Science at Serres Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Approval No. ERC-012/2024, Approval Date: 14 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| RPE | Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

References

- Bai, W.; Chen, P.; Cai, H.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Sha, S.; Xiang, Y.-T. Worldwide Prevalence of Mild Cognitive Impairment among Community Dwellers Aged 50 Years and Older: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Epidemiology Studies. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild Cognitive Impairment as a Diagnostic Entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomporowski, P.D. Effects of Acute Bouts of Exercise on Cognition. Acta Psychol. 2003, 112, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker-Drob, E.M.; Johnson, K.E.; Jones, R.N. The Cognitive Reserve Hypothesis: A Longitudinal Examination of Age-Associated Declines in Reasoning and Processing Speed. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.M.; Stern, Y. Cognitive Reserve in Aging. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2011, 8, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P. The Adaptive Brain: Aging and Neurocognitive Scaffolding. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning-Dixon, F.M.; Brickman, A.M.; Cheng, J.C.; Alexopoulos, G.S. Aging of Cerebral White Matter: A Review of MRI Findings. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Li, H.; Chen, K.; Yang, G.; Xie, H.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, M. Brain Compensatory Activation during Stroop Task in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Functional near-Infrared Spectroscopy Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1470747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleville, S.; Chertkow, H.; Gauthier, S. Working Memory and Control of Attention in Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neuropsychology 2007, 21, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollacott, M.; Shumway-Cook, A. Attention and the Control of Posture and Gait: A Review of an Emerging Area of Research. Gait Posture 2002, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-A.; Hwang, I.-S.; Wu, R.-M. Improving Dual-Task Control With a Posture-Second Strategy in Early-Stage Parkinson Disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 1540–1546.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, N.; Zinchenko, A.; Halle, M.; Geyer, T. Withstand Control: Standing Posture Differentially Affects Space-Based and Feature-Based Cognitive Control through Enhanced Physiological Arousal. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, E.R.; Dames, H.; Kiesel, A.; Dignath, D. Does Body Posture Reduce the Stroop Effect? Evidence from Two Conceptual Replications and a Meta-Analysis. Acta Psychol. 2022, 224, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroop, J.R. Studies of Interference in Serial Verbal Reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935, 18, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, C.M. Half a Century of Research on the Stroop Effect: An Integrative Review. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 109, 163–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Irandoust, K.; Modabberi, S. An Acute Bout of Dynamic Sitting Exercises Improves Stroop Performance and Quality of Sleep in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment. Int. Arch. Health Sci. 2019, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, C.H.; Erickson, K.I.; Kramer, A.F. Be Smart, Exercise Your Heart: Exercise Effects on Brain and Cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 Year Multidomain Intervention of Diet, Exercise, Cognitive Training, and Vascular Risk Monitoring versus Control to Prevent Cognitive Decline in at-Risk Elderly People (FINGER): A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Feng, T.; Mei, L.; Li, A.; Zhang, C. Influence of Acute Combined Physical and Cognitive Exercise on Cognitive Function: An NIRS Study. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini-Laplagne, M.; Dupuy, O.; Sosner, P.; Bosquet, L. Acute Effect of a Simultaneous Exercise and Cognitive Task on Executive Functions and Prefrontal Cortex Oxygenation in Healthy Older Adults. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, B.; Anthony, M.; Chen, S.; Turnbull, A.; Baran, T.M.; Lin, F.V. Brain Small-Worldness Properties and Perceived Fatigue in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2022, 77, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duschek, S.; Muckenthaler, M.; Werner, N.; del Paso, G.A.R. Relationships between Features of Autonomic Cardiovascular Control and Cognitive Performance. Biol. Psychol. 2009, 81, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L. Exercise Training for Cognitive and Physical Function in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e30168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Tian, H.; Thabane, L.; Ma, J.; Wu, H.; Zhong, Q.; Gao, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T. The Effects of Dual-Task Training on Cognitive and Physical Functions in Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment; A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 9, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Funahashi, S. Neural Mechanisms of Dual-Task Interference and Cognitive Capacity Limitation in the Prefrontal Cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, S.; Cortez, C.; Smith, E.; Rattanavong, J.; Ross, S.; Kline, G.; Wiechmann, A.; Dyson, H.; Mallet, R.T.; Shi, X. Enhanced Cerebral Oxygenation during Mental and Physical Activity in Older Adults Is Unaltered by Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1535045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Addamo, P.K.; Raj, I.S.; Borkoles, E.; Wyckelsma, V.; Cyarto, E.; Polman, R.C. An Acute Bout of Exercise Improves the Cognitive Performance of Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2016, 24, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, C. Glucose Improvement of Memory: A Review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 490, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.D. Determinants of Maximal Oxygen Transport and Utilization. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1996, 58, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gobbi Porto, F.H.; Coutinho, A.M.N.; de Sá Pinto, A.L.; Gualano, B.; de Souza Duran, F.L.; Prando, S.; Ono, C.R.; Spíndola, L.; de Oliveira, M.O.; do Vale, P.H.F.; et al. Effects of Aerobic Training on Cognition and Brain Glucose Metabolism in Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 46, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.Z.H.; Lindenberger, U. Relations between Aging Sensory/Sensorimotor and Cognitive Functions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2002, 26, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, E.; Dawes, H.; Smith, L.; Dennis, A.; Howells, K.; Cockburn, J. Cognitive Motor Interference While Walking: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, S.; Schumacher, V. The Interplay between Cognitive and Motor Functioning in Healthy Older Adults: Findings from Dual-Task Studies and Suggestions for Intervention. Gerontology 2011, 57, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Oteng-Amoako, A.; Speechley, M.; Gopaul, K.; Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C.; Muir-Hunter, S.W. The Motor Signature of Mild Cognitive Impairment: Results from the Gait and Brain Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.K.; Labban, J.D.; Gapin, J.I.; Etnier, J.L. The Effects of Acute Exercise on Cognitive Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Brain Res. 2012, 1453, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, C.J.; Freshwater, S.N. Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Uses; Stoelting: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpina, F.; Tagini, S. The Stroop Color and Word Test. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998; ISBN 0880116234. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical Bases of Perceived Exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, H.; Gustafson, K.; Ahmadnezhad, P.; Liao, K.; Mahnken, J.D.; Brooks, W.M.; Burns, J.M. Psychometric Properties of NASA-TLX and Index of Cognitive Activity as Measures of Cognitive Workload in Older Adults. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hile, E.S.; Brach, J.S.; Perera, S.; Wert, D.M.; VanSwearingen, J.M.; Studenski, S.A. Interpreting the Need for Initial Support to Perform Tandem Stance Tests of Balance. Phys. Ther. 2012, 92, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, T.; Luo, J. A Study on the Impact of Acute Exercise on Cognitive Function in Alzheimer’s Disease or Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients: A Narrative Review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 59, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, B.; Breitenstein, C.; Mooren, F.C.; Voelker, K.; Fobker, M.; Lechtermann, A.; Krueger, K.; Fromme, A.; Korsukewitz, C.; Floel, A.; et al. High Impact Running Improves Learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2007, 87, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Bugatti, M.; Otto, M.W. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Exercise on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 60, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, A.; Nicolò, A.; Bazzucchi, I.; Sacchetti, M. The Effects of Postprandial Walking on the Glucose Response after Meals with Different Characteristics. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T. Immediate and Short-Term Effects of Single-Task and Motor-Cognitive Dual-Task on Executive Function. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-T.; Yeh, N.-C.; Yang, Y.-R.; Hsu, W.-C.; Liao, Y.-Y.; Wang, R.-Y. Effects of Different Dual Task Training on Dual Task Walking and Responding Brain Activation in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, T.; Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Uemura, K.; Anan, Y.; Suzuki, T. Cognitive Function and Gait Speed under Normal and Dual-Task Walking among Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mademli, L.; Arampatzis, A. Effect of Voluntary Activation on Age-Related Muscle Fatigue Resistance. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).