1. Introduction

Safe design of building structures is possible only when the environment where construction works are situated is well identified. The occurrence of slope movements is a very important factor for the design risk and serviceability evaluation. Reliable measurements of the slope movements can be obtained through several methods, and their combination allows us to properly identify the behavior of the slope. Besides the conventional methods, such as inclinometric and geodetic observation, methods utilizing an indirect approach to quantity evaluation are more frequently used. A TDR method (Time Domain Reflectometry) utilizing the measurement of the response to the electric impulse in the cable is one of these methods.

Inclinometry is one of the most utilized methods to measure ground movements with high reliability. The digital inclinometer is a highly accurate device for the measurement of underground movements or deformations via the leading tube angle. A vertical inclinometer is applied for the monitoring of lateral displacements in embankments, retaining walls, landslide areas, dams, columns, or sheeting walls. The probe is portable, and the measurements are performed in stages.

The inclinometric system consists of casings, the probe, the control cable, and the readout unit. Inclinometric casings are equipped with longitudinal slots in two perpendicular directions for the orientation of the probe. They are installed close to the vertical in the structure element or in the borehole. The space between the borehole wall and casing is filled with a cement–bentonite grout. It is suitable to orient the slots to the assumed direction of the displacements. The probe contains two sensitive servo-mechanical accelerometers that are rotated by 90°. During the measurement, the probe is led into the slots of the casing using the small leading wheels. The probe is pulled from the bottom to the top in 0.5 m intervals. At each stage, an angle readout is performed, and this data is converted to displacement. When we compare the stage measurements, a differential or integral propagation of the horizontal deformations can be plotted.

The TDR method was developed for the detection of failure in cables for the energy and communication industry [

1,

2]. This method is still used by the major energy networks to detect various failures or illegal consumption. The losses in some countries can reach up to 40% of the overall power consumption [

3]. Signalization of the damage and deformations in the cables is a method that can be utilized not only in the energy industry. Use of the TDR in the building industry began with underground structures in the 1950s, when monitoring of wall movements and depression deformations during surface mining was performed [

4]. The TDR method was then applied to the observation of potential landslides at rock and soil slopes.

TDR was first used in landslide research in the 1980s for monitoring underground coal mines [

5] and has since been applied to several other case studies [

2,

6,

7,

8]. The principle of TDR is based on an electrical signal sent through a coaxial cable. Shear movements deform the cable, creating a peak in the cable signature, and the depth can be inferred from the signal. Laboratory tests of TDR for detecting shear processes were performed by Baek et al. and Blackburn and Dowding [

9,

10]. Pasuto et al. compared TDR cables with inclinometer measurements and extensometers [

2].

TDR was later better known for measuring dielectric properties by adding a sensing waveguide to the end of the transmission device [

11,

12]. They found that TDR cables are less sensitive to deformation but can withstand greater displacement than conventional inclinometers. Studies reported that inclinometers can provide the magnitude and direction of ground deformation, while TDR is primarily used to locate active shear planes [

6,

13,

14]. However, the amplitude of the TDR-reflected pulse due to the clamped cable deformation is proportional to the slope displacement, in which the amplitude can be used to estimate the localized shear deformation. Dowding et al. and Aimone-Martin et al. introduced calibration tests to quantify the empirical relationship between the shear displacement in a rock mass and the intensity of the TDR reflection spike [

4,

15]. In general, there are several critical factors affecting the relationship between the TDR reflection signal and the shear displacement, including but not limited to cable resistance, cable–grout–soil interaction, and shear area size. To explain the effect of cable resistance on the amplitude of the reflection spike, Pierce et al. presented an influence plot to demonstrate the effect of different lengths of lead cables on a specific cable type and deformation mechanism [

16]. Dowding et al. proposed a finite-difference wave propagation model to simulate the effect of cable resistance and multiple reflections [

17]. Lin and Tang later provided a more comprehensive and efficient wave propagation model that accurately simulates the TDR response, including the resistance effect [

18]. Based on this model, Lin et al. proposed a more general correction procedure to compensate for the effect of cable resistance [

19]. Therefore, this factor is now satisfactorily addressed in the relationship between shear displacement and TDR reflection spike amplitude.

Chu et al. used TDR technology for an automatic long-term monitoring system for shale slope deformation [

20]. Compared with drilled ones, TDR monitoring detected three landslide surfaces that were not clearly observable from core boreholes. Chung et al. and Xu et al. tried to optimize the sensitivity of TDR for shear and deformation quantification by providing guidelines for the design of a TDR coaxial cable in a physical model [

21,

22]. Chung et al. followed up on previous work and combined grouts and cable types to determine potential factors affecting the response of TDR cable to shear zone localization [

23]. They pointed out better sensitivity with respect to TDR cable grouts and cable–grout–soil interaction. Dussud, in his dissertation, presented nine cases of slope monitoring with TDR equipment and presented advantages and recommendations with respect to the type of rock environment in which it is located [

24].

Chung et al. monitored the physical properties of moisture change and the effect of drying and wetting, and Curioni et al. monitored the permittivity of the environment using TDR measurements [

25,

26].

Monitoring of the slopes has great importance in built-up areas and sites where infrastructure is situated in the slope localities. The TDR system is suitable as an early warning system, working on the principle of continuous monitoring and evaluation of landslide activity at the slope [

27]. TDR equipment is applicable for the monitoring of slopes endangering the safety of roads, railroads, and buildings exposed to potential landslides. Deformation or failure can be monitored continuously along the apparatus. Automatic collection of the data can be integrated into an early warning system. The system can identify the movement and alert the operator of the TDR system or the occupants of the building structures. The slope condition can be accurately evaluated on an alert basis, and a decision about further actions can be made.

TDR has also been used in recent years to measure soil water content. Greco et al. compared TDR sensors with strain gauges and concluded that TDR may be more useful for landslide monitoring and early warning because TDR measurements of soil water content change continuously [

28]. More examples of TDR application for groundwater monitoring are given in Hennrich, Nishigaki, and Li and Zhang [

29,

30,

31]. Observation of the dielectric constant of the soil is another utilization of this method [

32]. Topp et al. derived a relationship between moisture content and the dielectric constant of the soil [

33]. Further studies proved that Topp’s equation does not provide accurate results for the heavy clays, organic soils, and soils with very high or very low density [

34]. Semi-empiric relations based on the dielectric laws show significant improvement compared to the empiric equation [

35].

Findings in the abovementioned studies were elaborated in a series of in situ applications of authors, within which the evaluation procedures of signals with consideration of various cables were calibrated to achieve a reliable output of TDR monitoring [

36,

37]. Study methodology combines traditional inclinometers, TDR probes, and numerical simulation to estimate the stability potential of the investigated area. Despite some useful benefits of TDR sounding, such as inexpensive installation and remote continuous collection of data, the lack of reliable determination of movement magnitude corrected by traditional inclinometry will be addressed in this paper. The study represents a contribution to the methodology of evaluation of stability risks using a multi-tool approach with consideration of practical application.

2. Materials and Methods

For quantification of the potential landslides at the selected site, a conventional method comprised a combination of conventional precise vertical inclinometers and TDR technology for the evaluation of the deformation along a vertical borehole and for the measurement of groundwater level. Inclinometers and piezometers were installed in the boreholes made during the geological survey.

2.1. Traditional Inclinometry

The inclinometric system consisted of casings, the probe, the control cable, and the readout unit. Inclinometric casings were equipped with longitudinal slots in two perpendicular directions for the orientation of the probe. The space between the borehole wall and casing was filled with a cement–bentonite grout. The slots were oriented in the direction of the slope displacements. The probe contains two sensitive servo-mechanical accelerometers that are rotated by 90°. During the measurement, the probe was led into the slots of the casing using the small leading wheels. The probe was pulled from the bottom to the top in 0.5 m intervals. At each stage, an angle readout was performed, and this data was converted to displacement. The overall measurement method accuracy according to the manufacturer is 1 mm/15 m of the probe. The parameters of the inclinometers are listed in

Table 1.

2.2. TDR (Time Domain Reflectometry)

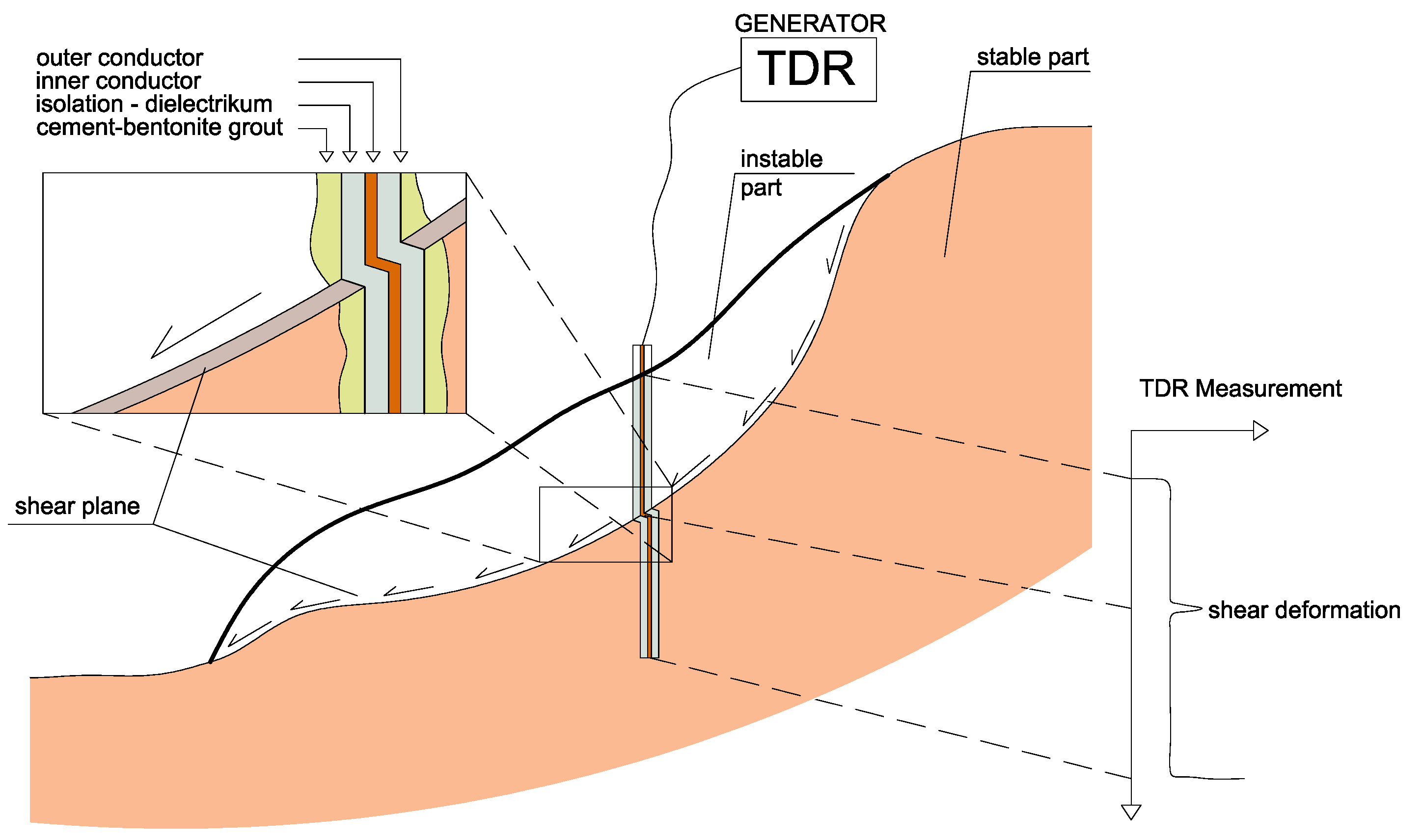

Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) is a method based on the electromagnetic principle and can be described as a “radar in cable”. The TDR testing system consists of components shown in

Figure 1.

The method is based on the emission of electromagnetic impulses along the whole length of the monitoring cable, which is installed in the monitoring borehole. The frequency of the impulses is usually in the interval from 100 to 300 per second. A coaxial cable with metallic or plastic coating is optimal for slope movement monitoring using the TDR method. The coaxial cable is an electric cable combined with two wires that are separated by a layer of dielectric material. Plastic or a combination of air and plastic is usually used as a dielectric. Cables with plastic dielectric are utilized for the monitoring of deformations, and cables with a combination of plastic and air dielectric are used for monitoring the groundwater level. Coaxial cables used with the TDR technology provide a space for the propagation of the electromagnetic impulses emitted from the TDR pulsator. Impulses travelling through the coaxial cable create an electromagnetic field. The propagation of the electromagnetic wave is controlled by the four basic parameters of the cable:

Inductance (L)—current flow along the wire induces the magnetic field whose power is controlled by the cable inductance;

Resistance (R)—defines the energy loss (wire resistance);

Capacitance (C)—voltage differences between external and internal wire;

Conductance (G)—dielectric between two wires has a small conductivity and dissipates the energy, which is defined by this quantity.

2.2.1. Deformation Measurement

Characteristic impedance

Zo is an important parameter of the cable and is defined as a function of the cable induction

L and capacity

C.A cable that is not damaged and has no mechanical failures along the whole length, such as bends or ruptures, has approximately constant impedance. If a change in the geometry takes place, emitted impulses meet the deformed zone and are reflected. This leads to a change in impedance

Zo at a given point. The return time of the emitted impulse at a known velocity of the electromagnetic energy in the cable localizes the exact position of the damage. Proportional amplitude and velocity of the shift within the time localizes the deformation zone, which is exactly and instantly determined. The reflected electric signal in the distance

x along the cable is analyzed at a given moment with the corresponding boundary conditions and is defined as

The change and drop in the voltage

V are caused by the electric current that travels through the given section with the changed cable parameters of inductance (

LΔ

x), adding resistance (

RΔ

x), conductance (

GΔ

x), and capacitance (

CΔ

x). Combining the parameters results in

The coefficient of reflection

ρr is defined as a ratio of the reflected impulse

vr and emitted impulse

vi, which is defined as

Using the cable detector of the signal, we can graphically analyze the coefficients of reflection, and the change in the coefficient of reflection is manifested as a drop in the chart. The velocity of the electromagnetic signal in the cable is an important parameter to determine the distance of the reflection point. The velocity is expressed as follows:

The size, importance, and type of failure can be determined following the coefficient of reflection ρr. Usually, two extreme cases can occur. The first, ρr = −1, takes place when there is a contact between external and internal wires (shear loading). The second, ρr = +1, takes place when the cable is ruptured or ended.

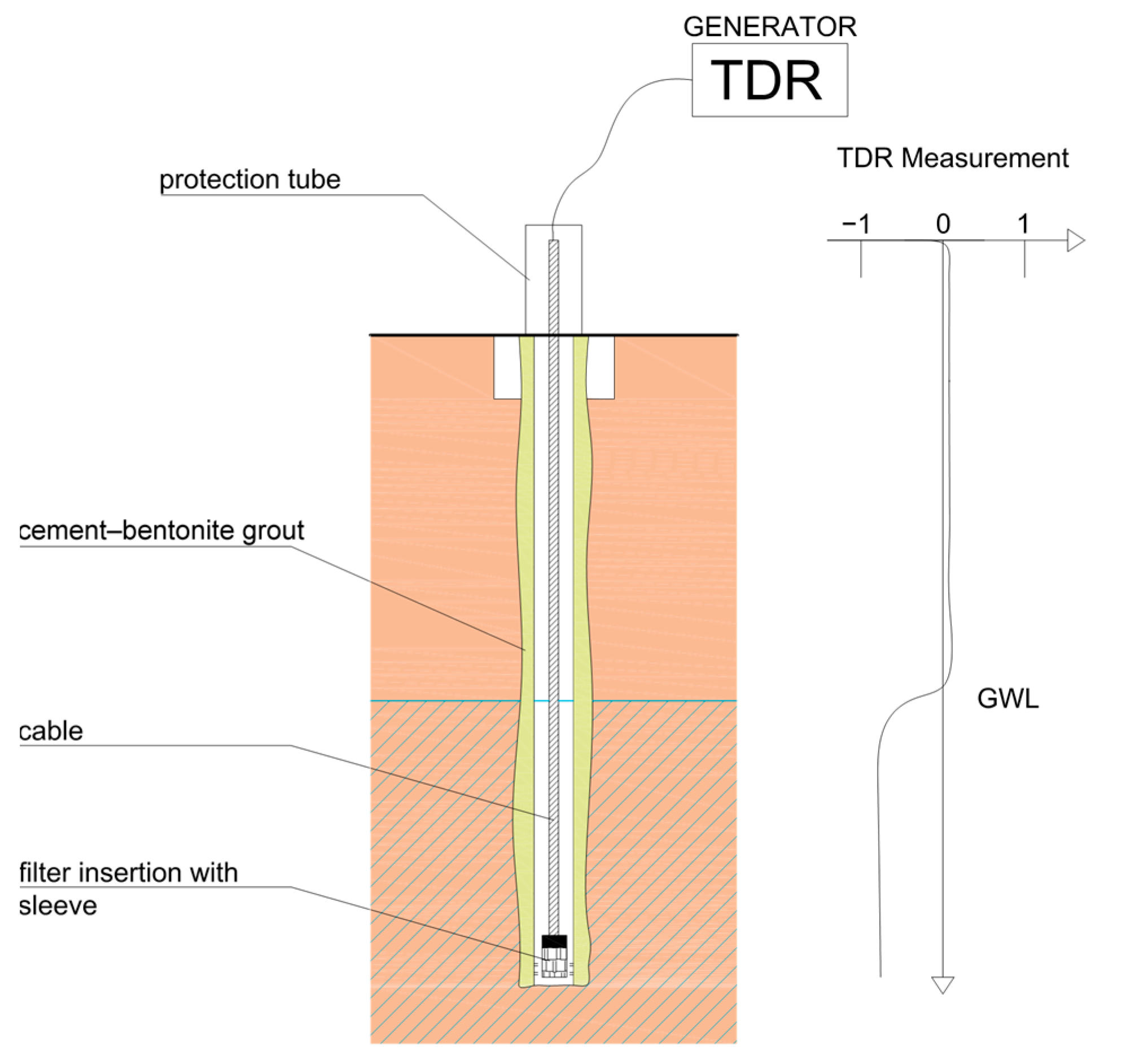

2.2.2. Groundwater Level Observation

Slope stability is unfavorably affected by the groundwater and oscillation of its level. High groundwater level is one of the primary factors causing slope deformations. Without knowledge about the cause of the creation of the geodynamic phenomenon, it is very difficult to predict its further development and potential risks. The TDR system allows for monitoring the groundwater level using special coaxial cables. The dielectric of these cables consists of air (hollow coaxial cables). The cables consist of smooth internal and corrugated copper wires, which are separated by an air gap and a polyethylene spiral. The external copper cover is protected by the PVC sleeve. Copper wires are supposed to be reliable in terms of the lifetime of the equipment. Usability of the device is limited by the filter congestion, which is located at the bottom end of the cable. The TDR piezometer installed at the locality in the case study is shown in

Figure 2.

In principle, the device acts as an open piezometer for monitoring the groundwater level. It consists of the borehole in which the casing is embedded. The perforated filter tube covered with the geotextile filled with sand or fine gravel is attached at the bottom of the cable. The hollow coaxial cable with the required length is then inserted into the casing. The gap between the borehole wall and the casing is filled with a cement–bentonite grout [

6].

The observation of the response offers two main curve shapes. If the impulse reaches the groundwater head, the reflection coefficient gets close to the zero value, and after passing below the water, the reflection coefficient reaches negative values close to the value of −0.6. This phenomenon is based on the physical principle where the water has a higher permittivity than air. The dielectric constant of water is 81, while that of the air is only around 1.0. The change in pore pressure Δ

u is calculated as

The accuracy of the measurement depends on the type of cable, the connectors used, and the length of the cable. Because the signal travels through sections with non-even velocity of impulse

vp,1 and

vp,2, it is necessary to take this fact into account. The overall trajectory of the travelled signal is

where

lp is the length of the lengthening cable,

lm is the length of the coaxial cable,

lk,i are particular lengths of the connectors, and

lr,i are the lengths of the potential reductions.

2.2.3. TDR Instrumentation

The suitability of the use and correct interpretation of TDR results for slope deformations depends on the appropriate combination and setting so that the composite cable–grouting has a stiffness similar to the stiffness of the soil. A more ideal case occurs in homogeneous soil. In our case, it was decided to choose the cable–grouting type, taking into account the recommendations [

19,

24,

38,

39,

40]. Cable and grouting specifications are listed in

Table 2.

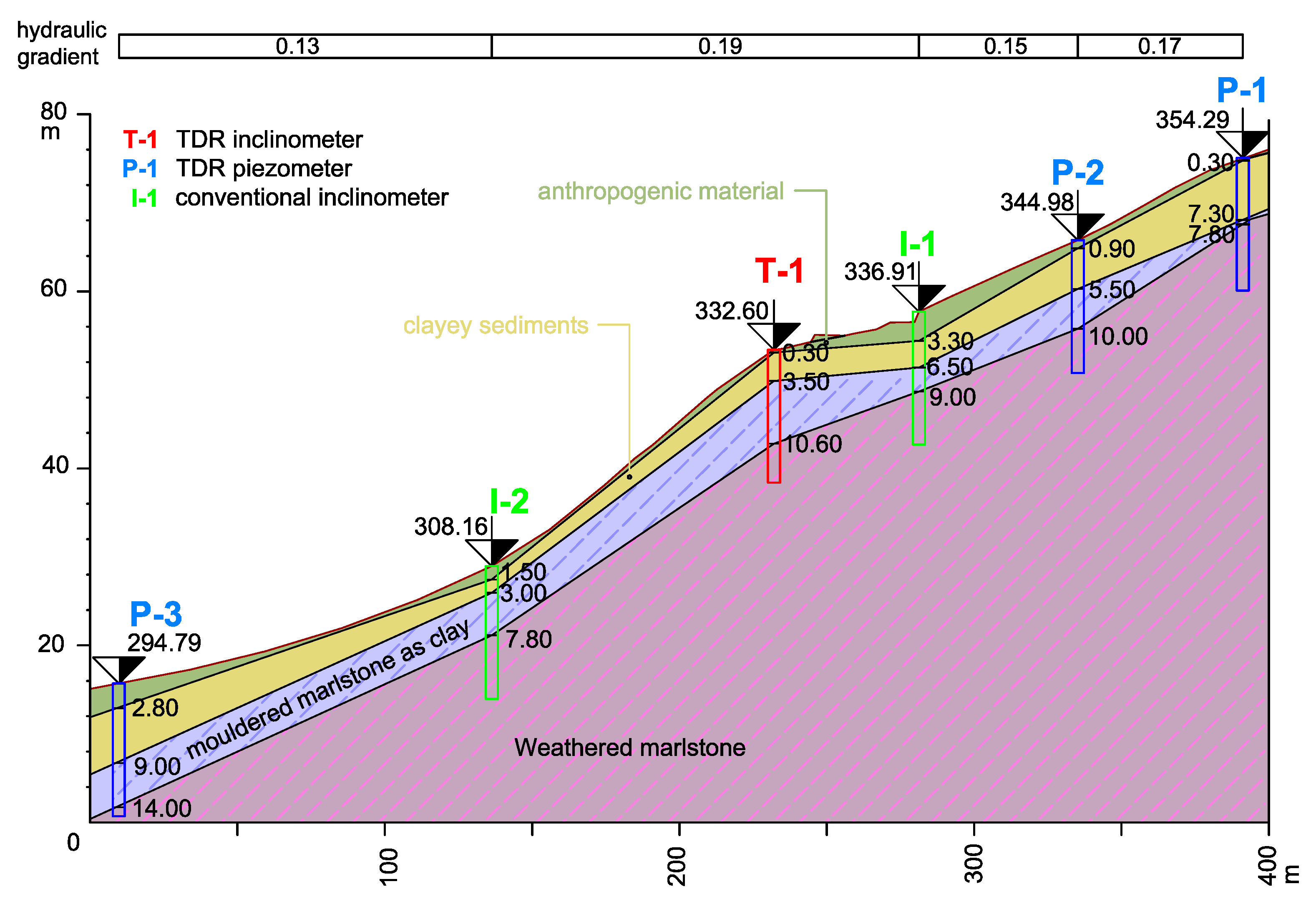

2.3. Monitored Site

The area of interest is represented by the built-up urban city quarter in the northwestern part of Slovakia, known for its favorable conditions for the formation of landslide activity (

Figure 3). In slope stability risk zoning, the area is classified as an unstable area with a confirmed old, stabilized landslide with an overall extent of up to 42,000 square meters.

The investigated area is markedly sloped, and it was affected by the geodynamic phenomena of sliding in the past. The area has not been monitored in detail yet, so the observation grid was proposed to investigate and evaluate the potential movements. Calculation of the actual stability and determination of the boundary conditions at which the slope reaches the critical state were the main tasks of the slope analysis.

The geomorphological conditions of the area are determined by geological composition, neotectonic development, and the geodynamic events that affected the area in the past. The general inclination of the slope is 12°. The relief of the investigated area and the adjacent territory reflects the relation between the resistance of the rocks to weathering and the morphology. The area is formed by the flysch complex with the superiority of marl, marlstone, and marl slate (Albian—Lower Cenomanian); and the flysch complex of marl, sandstone, and conglomerate (Upper Campanian—Maestrichtian).

Areas with a higher share of sandstone rocks, which are more resistant to weathering, are characterized by the higher energy of the relief. On the contrary, areas with a higher share of marlstone are characterized by softer forms with lower relief energy, such as depressions, saddle-backs, or erosion furrows. They are prone to excessive weathering, and a large eluvium–colluvium complex of clayey sediments is created in their territory. Together with the groundwater, this creates very good conditions for landslide activity and potential risk during the building process.

The slope is registered in the register of the landslides of the geological institute as a recently stabilized landslide covered by anthropogenic activity. The landslide does not show any indication of actual activity, but some marks of expected past activity exist, such as cracks in fencing walls or sidewalks (

Figure 4). We assume that certain favorable circumstances can trigger slope movement.

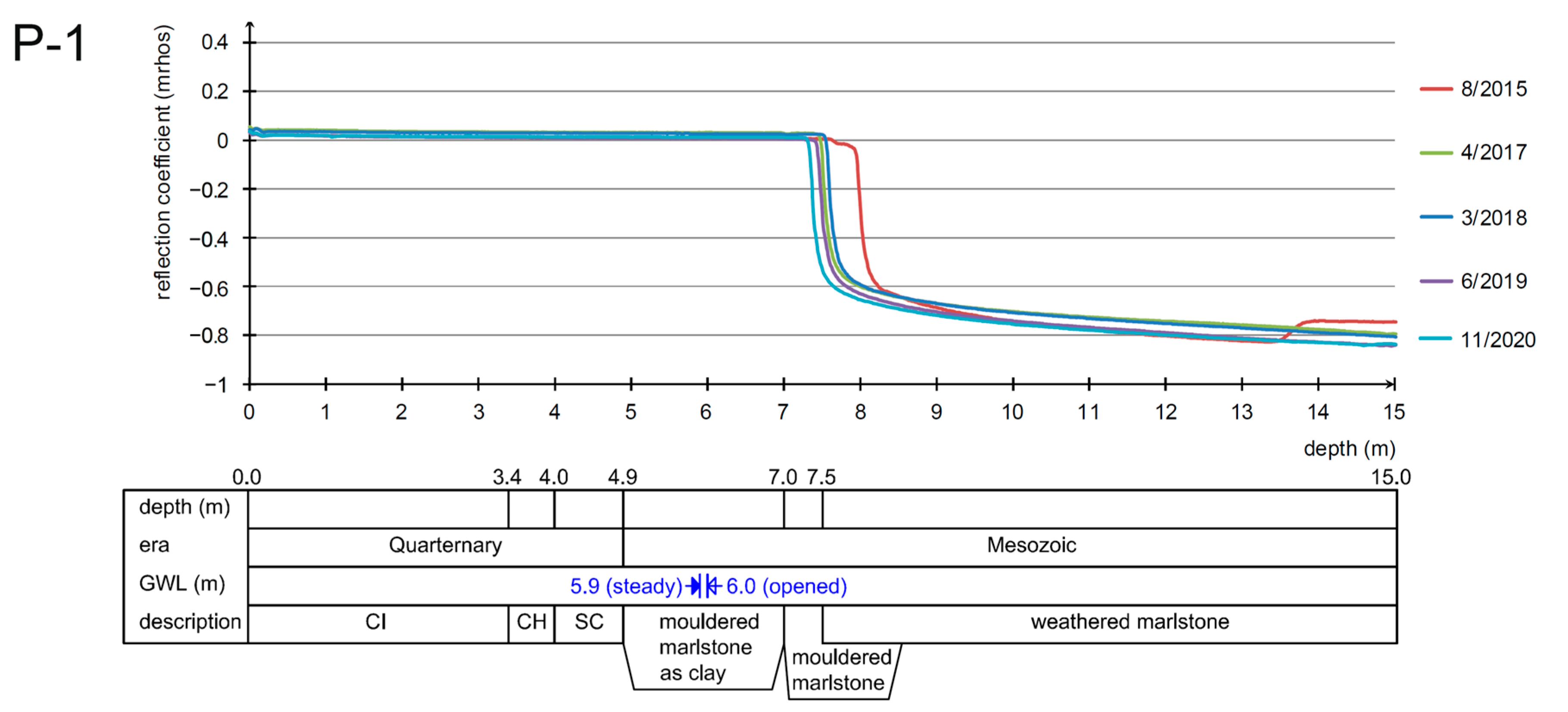

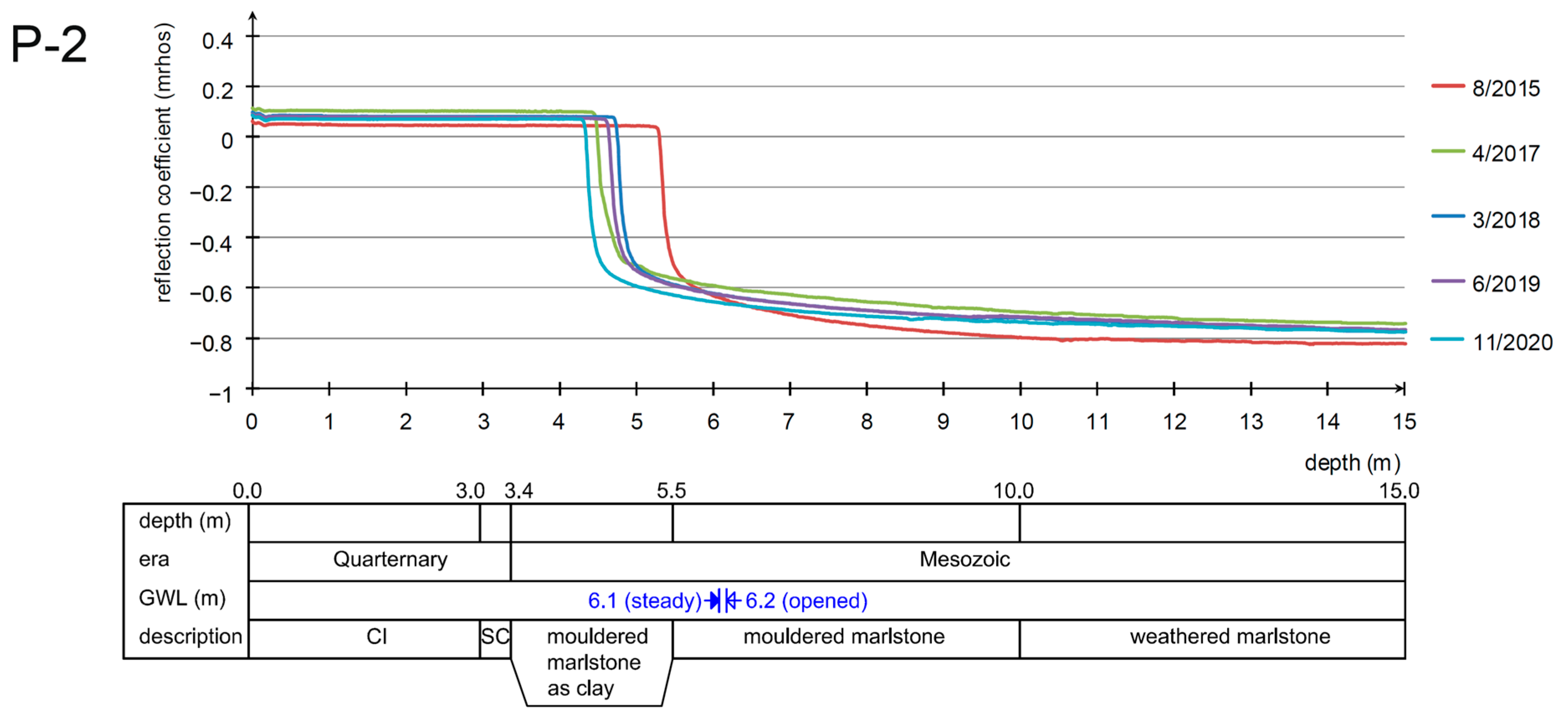

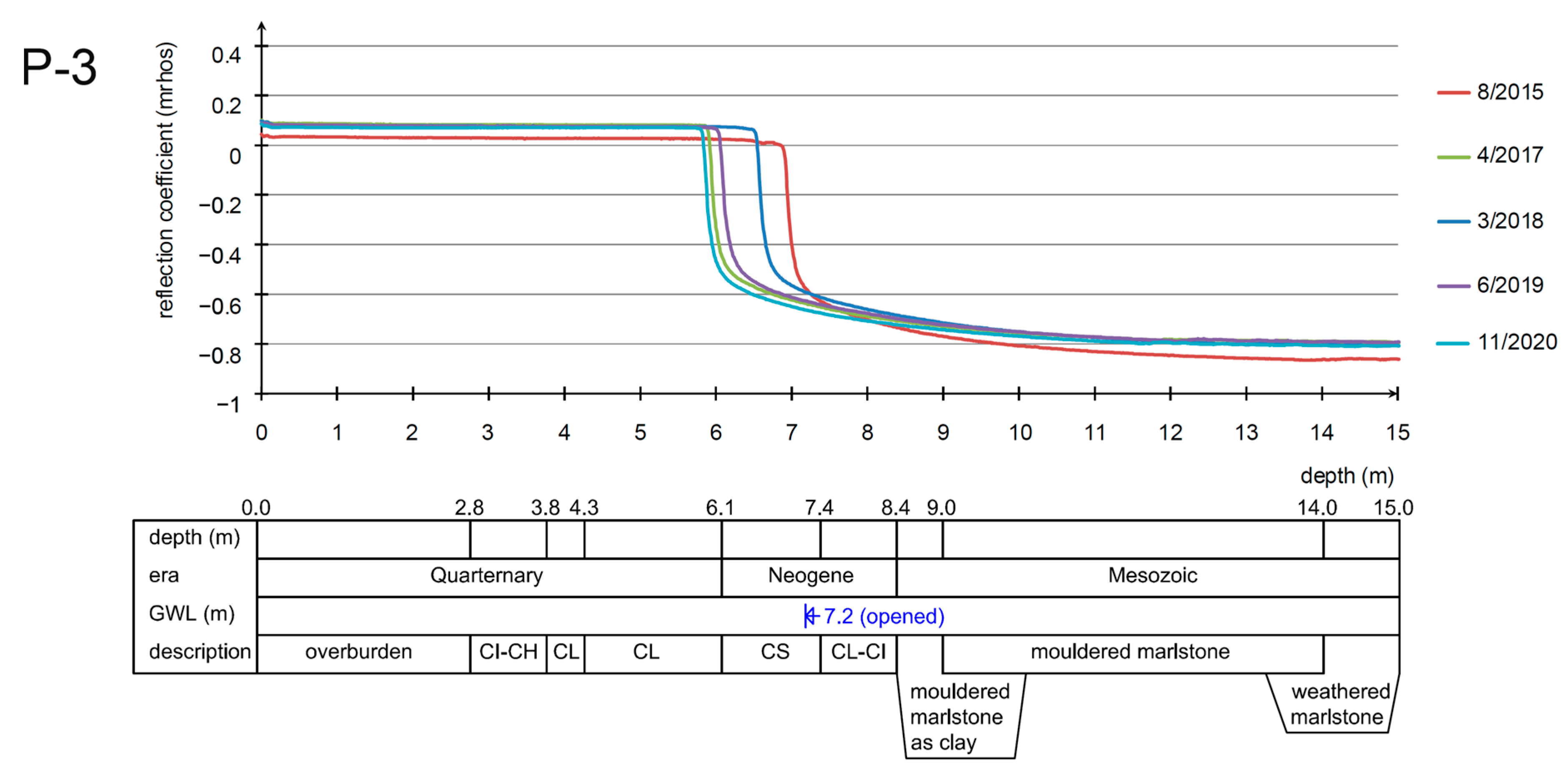

Geological conditions were investigated in the boreholes I-1 to I-2, T-1, and P-1 to P-3 up to 15 m under the terrain (

Figure 5). Monitoring equipment was installed in the boreholes after macroscopic analysis and sampling of the obtained rock and soil cores.

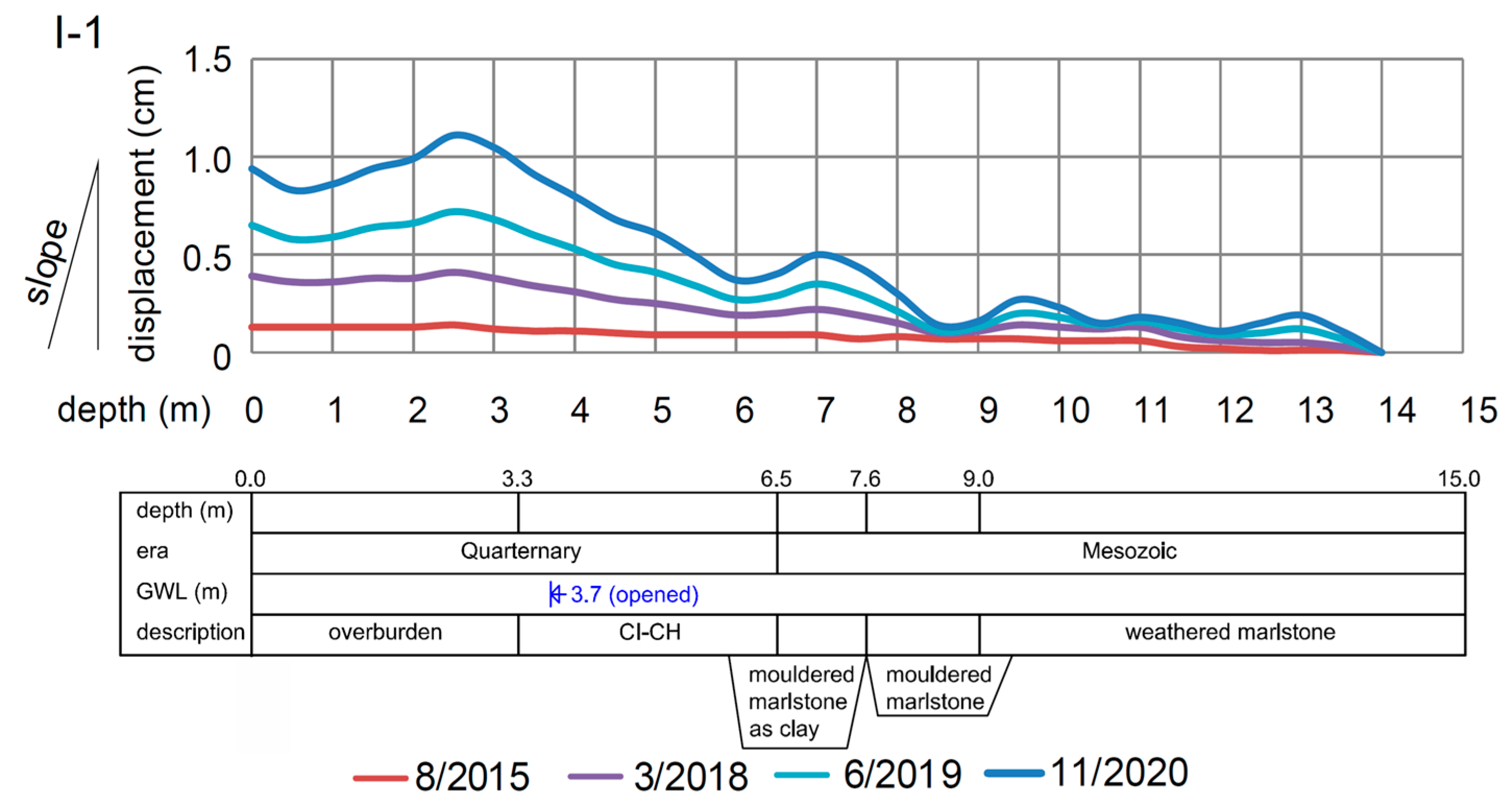

2.3.1. Geological Conditions

Rocks of the Pre-Quaternary era were verified in every survey borehole. These layers consist of weathered to mouldered marlstone of dark grey color, which continuously changes to mouldered marlstone towards the overburden. The boundary between these zones is hardly recognizable, but according to the boreholes, it lies at a depth of 7.5 to 14.0 m. The overall thickness of the weathered and mouldered marlstone was not examined during the survey, but the upper boundary lies at a depth of 3.0 to 9.0 m.

The upper part of the eluvium zone consists of mouldered marl that can be classified as an intermediate-plasticity clay with stiff to firm consistency. The overall thickness is 0.4 to 2.1 m, and the upper boundary is at a depth of 2.0 to 8.4 m (

Figure 6).

Pre-Quaternary rocks are covered with landslide colluvium and with the complex of Quaternary terrace and colluvium sediments in the boreholes P-1 and P-2.

Landslide colluvium consists of clay of intermediate to high plasticity and stiff to soft consistency at the bottom of the layer. The thickness varies from 1.1 to 5.6 m, and the upper boundary is at a depth of 0.3 to 2.8 m.

Terrace sediments are created by the clayey sand with a thickness of 0.4 and 0.9 m, respectively, and the upper boundary is at a depth of 3.0 and 4.0 m, respectively.

Overburden colluvium sediments were classified as a clay of intermediate to high plasticity and stiff to soft consistency. The thickness is from 2.4 to 3.5 m, and the upper boundary is at a depth of 0.2 and 0.3 m, respectively.

The top Quaternary layers consist of anthropogenic material as a backfill and can be classified as a silt containing communal and building waste with gravel and sand. The thickness varies from 0.3 to 6.5 m.

According to Eurocode 8, the area lies in a region with expected higher seismic activity. The intensity of a potential earthquake can reach up to 7° according to the MSK-64 scale. The closest epicenter of a recorded earthquake of intensity 8° is about 21 km away. The area is affected by confirmed and expected deep tectonic failures and faults. The basic seismic acceleration, according to Eurocode 8, is agr = 0.63 m·s−2.

2.3.2. Hydrogeological Conditions

Hydrogeological conditions are mainly determined by geological composition. The Mesozoic bottom creates only limited space for the groundwater flow, and the water is bounded by the crushed plates and banks of sandstone and slate. Groundwater flows in isolated horizons, which leads to the creation of the piezometric surface. Jointed sandstone rocks create good conditions for groundwater flow, but the flow is very limited in the marlstone rocks and eluvium–colluvium soils. This causes the creation of underground barrier springs.

Similarly, eluvium–colluvium clayey sediments are almost impermeable, and the flow is connected to the predisposition zones with higher amounts of fragmented material or sandy layers.

Groundwater flows from higher levels down the slope, and the amount of water depends on the seasonal change in moisture content in the massif. Groundwater was observed in the mouldered marlstone or fine sediments at a depth of 3.7 to 7.2 m. The water rose up to a level of 5.9 to 6.1 m under the terrain 24 h after initial observation. The groundwater has a tense character with uplift of 1.0 to 1.5 m after drilling in piezometers P-3 and P-2, respectively.

2.3.3. Geotechnical Parameters of Rocks and Soils

A total of 18 undisturbed samples for laboratory testing were prepared. Laboratory testing involved investigation of physical and strength parameters and identification of soil types—granulometry, consistency limits, and shear box tests with samples of size 10 × 10 cm. All tests were carried out according to Slovak technical standards STN.

The coefficient of filtration

kf was determined using a grain–size curve in accordance with Jáky’s theory for fine soils and the Carman–Kozeny theory for sands. Fine soils have a coefficient of filtration

kf in the interval from 2.148 × 10

−8 to 5.210 × 10

−9 m·s

−1 and sands in the interval from 2.137 × 10

−5 to 7.521 × 10

−5 m·s

−1. The strength parameters of soils are displayed in

Table 3.

Considering the macroscopic evaluation of cores, the laboratory results, and regional expertise, the adjusted parameters of rocks and soils were determined for typical rock and soil types (

Table 4).

2.4. Monitoring Works

The following methods of geotechnical monitoring were selected for the quantification of the underground activity of the landslide in the area (

Figure 5):

Traditional inclinometers in boreholes I-1 to I-2 using a digital vertical inclinometer;

TDR method (Time Domain Reflectometry) for inclinometric (borehole T-1) and piezometric measurements (boreholes P-1 to P-3).

TDR piezometers with the special Heliflex cable were installed up to the water-bearing part of the borehole for the observation of groundwater (

Figure 2).

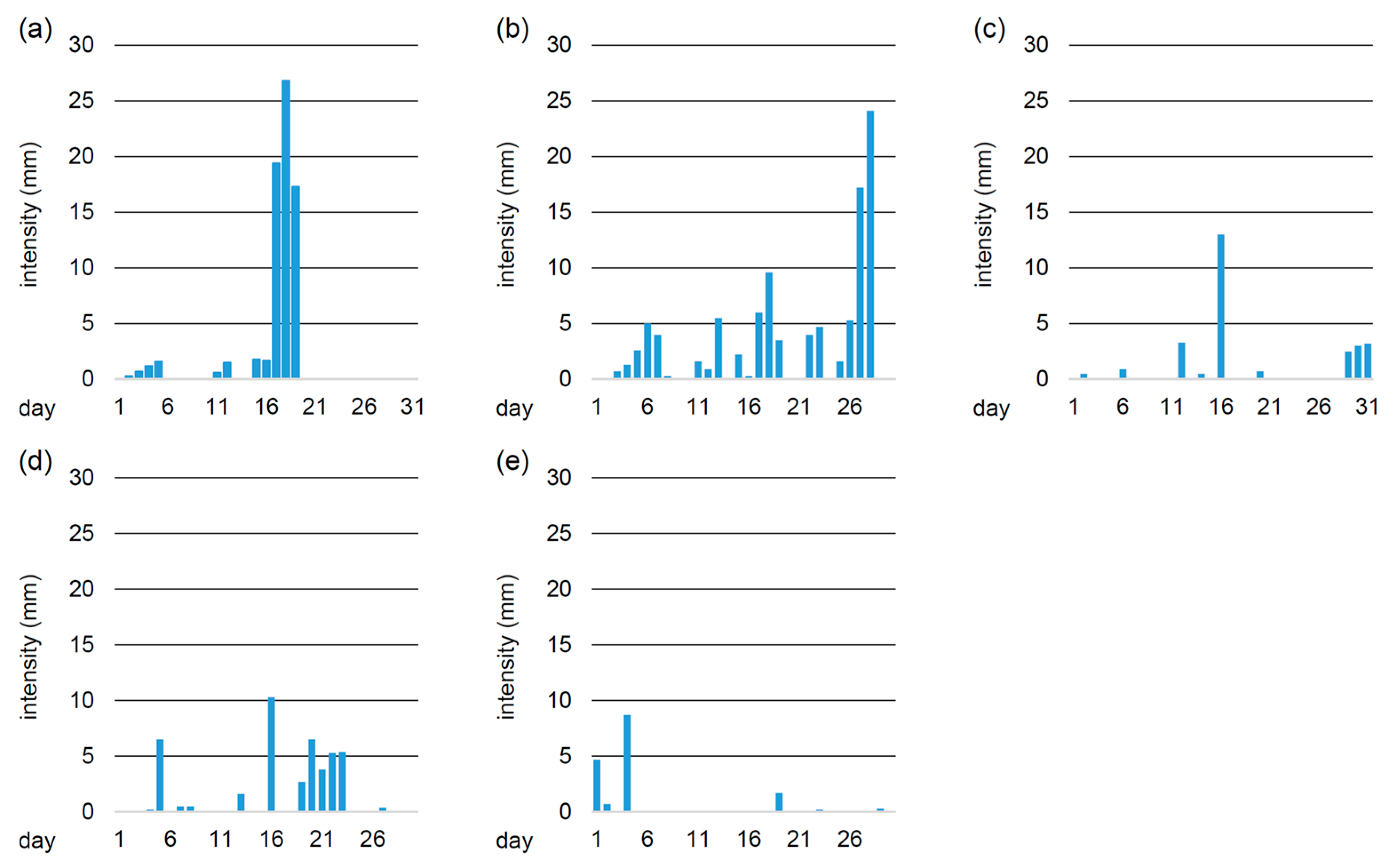

The layout of monitoring boreholes respects the terrain profile, where boreholes were situated close to sections with steeper inclination and thus higher potential of local sliding. In the case of piezometers, a local increase in groundwater level was observed in the basements of buildings. This phenomenon deviates from recent behavior and can be related to increasing construction activity in the upper parts of the area, together with the limited capacity of the obsolete dewatering system and climate factors.

The slope was monitored for five years, on a yearly basis in the last three years.

2.5. Numerical Modeling

For validation of monitoring data and estimation of the stability potential of the area, numerical modeling was adopted. The stability of the area was investigated in the characteristic profile (

Figure 5, red line). The profile starts in the borehole P-1 in the residential area and continues through the garages and the road under the residential area, and follows the pavement to the borehole P-3.

Calculation was performed in the software Plaxis 2D 8.5 using the Finite Element Method (FEM) with 15-noded elements. The Mohr–Coulomb material model was selected. The investigation of slope stability is based on the determination of the safety factor

FS when the shear strength parameters are reduced (friction angle and cohesion). The factor of safety

FS represents the ratio of the values of the initial shear strength parameters

φinput and

cinput and the reduced values

φreduced and

creduced at which the collapse of the slope takes place:

Before the calculation of the stability, an initial phase considering the actual state of the slope with the buildings and the pavements should be performed. This is performed through the gravity loading procedure instead of the usual K0 procedure. During the K0 procedure, the solver calculates the earth pressure that leads to the out-of-balance forces when the terrain or groundwater head is inclined. The initial state of our problem represents an inclined slope, so this procedure is unacceptable. When using the gravity loading procedure, the calculated forces are always balanced and correspond with the real state when no strains are allowed for the initial stage.

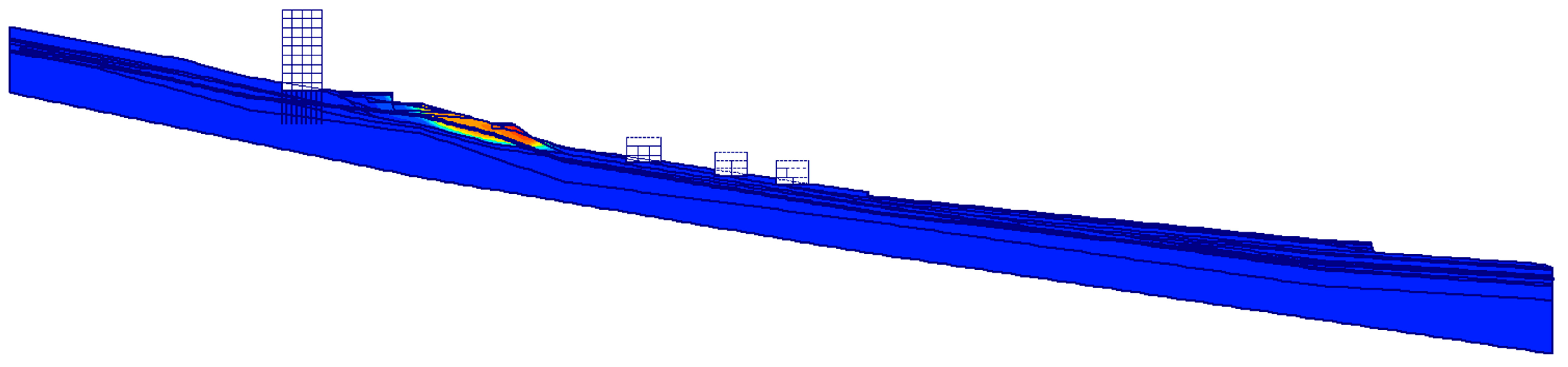

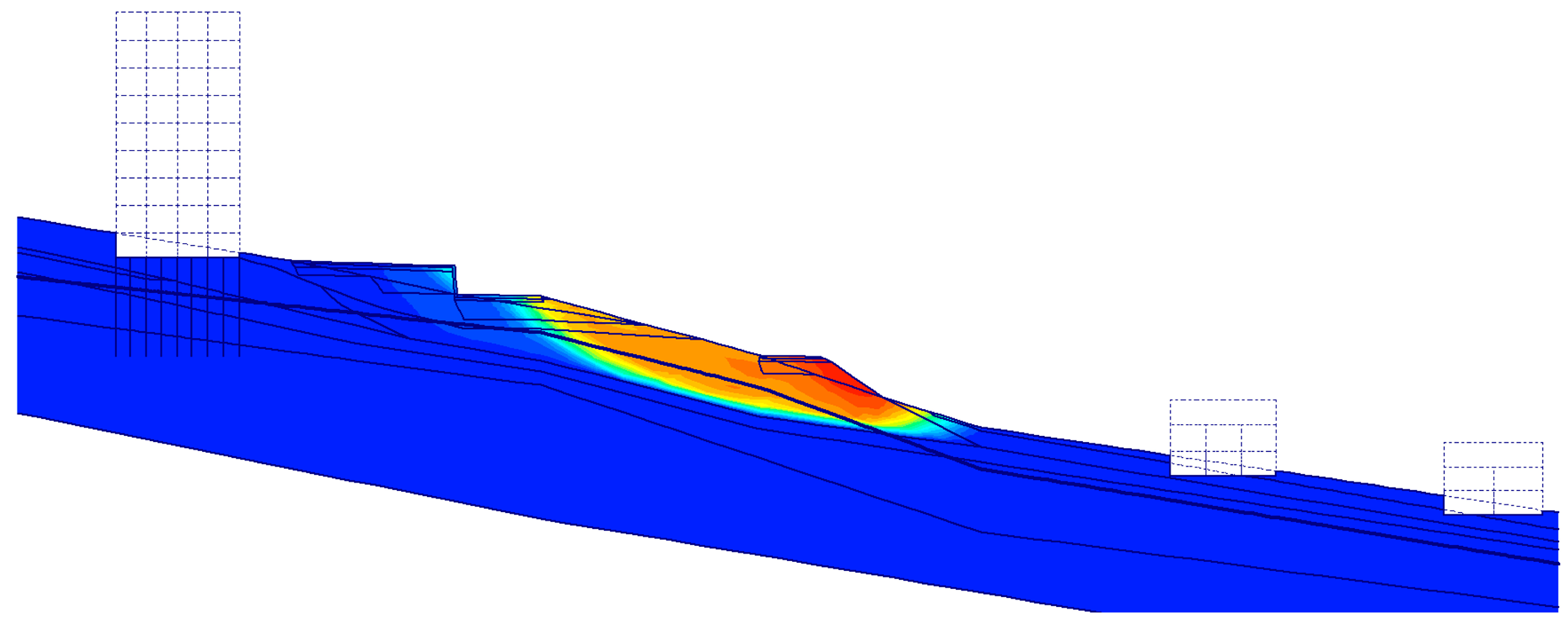

The factor of safety was calculated for the original state of the slope without the influence of anthropogenic activity. The scheme of the numerical model according to the monitoring profile (

Figure 5, red line) is plotted in

Figure 7.

For FEM modeling, the geotechnical parameters in

Table 3 and

Table 4 were applied to materials using the Mohr–Coulomb material model. There are no significant differences in various approaches for the calculation of slope stability, especially if the shape of the shear plane is determined by geological profile [

41,

42].

4. Discussion

The presented case study shows the requirement of the complex analysis of slope stability, including geological survey, monitoring, and stability evaluation. The measurements and numerical analyses have proven the global stability of the slope, but local surface sliding was observed. The change in the groundwater level can lead to loss of stability. The steepest part of the slope is the most affected. Marks of past movements are visible on the shallow-founded line objects, such as fence walls and sidewalks; the buildings, at this stage, show no signs of underground movements, such as cracks.

Considering the occurrence of weathered to mouldered marlstone, whose lower limit was not examined by the survey, we assume that the slope can slide along the deep-seated shear plane, which was not recorded in the boreholes. The depth of the plane is assumed to be up to 30 m. This fact was repeatedly noted at other landslide localities, especially in the case of larger areas. Therefore, the boreholes and monitoring equipment should be lengthened under the potential deep shear plane to verify its position.

The slopes affected by past movements often show creep deformations with very slow sliding. Considering the small interval of displacements, it is necessary to provide sufficient contact of the inclinometric borehole and the surrounding soil. This is fulfilled through the grout, which can, however, be a source of monitoring errors. According to the experience of the authors, an analysis of the overall accuracy of conventional inclinometry, including the influence of contact of ground and casing, lacks in practice. This is obvious when oscillation movements (“there and back”) are observed, which can be affected by seasonal changes in temperature and groundwater level. A replacement of grout with fine gravel in a major part of the borehole is one of the proposals that has already been applied in situ [

43].

Unpublished laboratory experiments of the authors to estimate the magnitude of movement using the TDR cable did not lead to a reliable output that can be reproduced in practical applications. Thus, the accuracy of the TDR method is limited to identification, or more precisely, to verification of potential shear planes and subsequent monitoring at a higher displacement rate in comparison with traditional inclinometry.

Numerical analyses show the loss of slope stability (safety factor equal to 1.0) when the groundwater generally reaches −1.0 m below the terrain. This level was recorded in the borehole I-2, but in TDR piezometers, the water table was observed much deeper. This local anomaly can be explained as a possible leakage of the nearby sewer and dewatering system. However, more frequent groundwater level monitoring is then required. An increase in the water content in the massif is one of the most frequent factors affecting the formation of ground movements. In the opinion of the authors, the application of FEM modeling is “cumbersome” when a quick forecast of landslide events is required. However, the modeling is very useful for the identification of critical sections and for the placement of monitoring works.

Utilizing more advanced material models in numerical modeling can improve the calculation of slope creep behavior, in addition to determining the propagation of shear planes with corresponding safety factors.

The necessity of improved monitoring performances could be achieved thanks to the installation of innovative instrumentation featuring automatic processes for data acquisition and elaboration. In particular, it could be possible to integrate into the existing system a multi-parametric automatic inclinometer in order to monitor different physical quantities with the same tool. Moreover, features like continuous data sampling, high frequency of acquisition, and near-real-time elaboration are extremely useful to implement Early Warning procedures, allowing the application of advanced algorithms and models to identify an impending failure and disseminate alert messages [

43,

44,

45].

Geotechnical monitoring can be combined with remote sensing methods and measurements at buildings to create a complex on-site monitoring system [

46,

47,

48]. That brings the possibility of predicting the moment of activation of ground movements based on actual monitoring data using a regression approach or machine learning [

49,

50,

51]. Unfortunately, the TDR method cannot reliably describe the magnitude or velocity of ground movements, but in the case of groundwater observation, data from TDR piezometers are highly valuable for real-time forecasts of landslide events, as a change in the water content in the ground is one of the most prominent factors that cause ground movements.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the slope stability reserve is a very complex task. Not only should global stability be investigated, but also partial sliding or creep effects should be monitored. These phenomena can endanger the particular objects on the slope in terms of both the serviceability and ultimate limit state.

Frequent observation of the groundwater level and the corresponding stability analysis based on the monitoring outputs are a necessary part of the examination. The capability of continual collection of data from TDR inclinometers and piezometers is very suitable for the real-time observation of landslide areas, especially in the case of potential sudden, large movements that can be predicted through frequent monitoring.

One of the main disadvantages compared to using an inclinometer is the inability to determine the orientation of movements. To date, the magnitude of the deformation can only be determined approximately, so a good approach is to apply TDR probes in localized shear zones. A combination of the TDR method with traditional inclinometry allows for combining the advantages of both methods, like low-cost continuous remote observation with TDR probes and precise determination of ground movement magnitude with traditional inclinometers.

Research into a wide range of installation configurations (including cable materials, sizes, thicknesses, and grout mixtures) will allow the creation of a number of standard installation types for different geological conditions. This should reduce some sources of error and lead to increased measurement accuracy.

The most significant advantages are the simple and comparatively inexpensive installation of a TDR system and the possibility of continuous monitoring of movements using remote data collection tools. This allows the impact of, for example, heavy rainfall on slope stability to be monitored in real time, which could lead to better prediction of landslide behavior by means of calibration of, e.g., numerical models, to understand the behavior of the monitored massif.