1. Introduction

Personalized medicine requires sophisticated logistics as well as appropriate storage and transport of tailor-made Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) [

1]. While liquid or solid dosage forms are commonly used and can be stored for years, printed artificial tissues require dedicated handling and pose storage challenges that—so far—have only been encountered in the fields of cryopreservation, blood banking, and organ donation. In particular, failures in batch processing or delays must be avoided at all costs. Concepts currently under discussion include direct linkage of manufacturing and patient application within specialized clinics, or centralized production combined with safe transport of ATMPs [

2,

3,

4]. In any case, protocols for short- and long-term storage must be developed, including non-destructive, rapid quality control methods to ensure product stability.

Common storage conditions for sensitive pharmaceutical and medical materials today range from −15 to −25 °C, or between 2 and 8 °C for short-term storage. When gentle storage conditions and low energy consumption are required, freezing stress must be avoided [

5,

6]. Frozen storage and transport at −20 °C are also routinely used in the food industry for cold-chain logistics [

7]. If long-term storage is needed, or when cell-based products must be preserved, cooling to −196 °C is possible, as applied in various cell-based applications [

5,

8]. However, storage at −196 °C is costly due to specialized equipment and high energy demand—besides the potential impact on the material itself. An alternative is storage at −80 °C, a temperature used for certain COVID-19 vaccines [

5] as well as for fibroblasts encapsulated in alginate microspheres [

9,

10]. Currently, only short-term cell storage is routinely implemented. In summary, appropriate storage conditions depend on the specific product and its stability.

To ensure quality and stability throughout production, logistics, and storage, non-destructive, reliable, and rapid monitoring is required. For practical implementation in healthcare environments, analytical tools that are commonly available in medical settings are preferred. Non-destructive analytical methods are needed to monitor product quality, including scaffold stability. As an initial step toward quality control and as proof of principle, 3D-printed scaffolds were studied under typical storage conditions in this work. The critical quality attributes (cQAs) addressed here concern geometric properties, structural integrity, composition, and water loss.

In this article, we describe a workflow for quality monitoring in contexts requiring controlled freezing conditions according to the current standard of the Parenteral Drug Association [

11], with a focus on structural integrity as a cQA. Scientific analy-ses of cell localization, viability, and optimization of cooling gradients to avoid local pro-duct stress have been investigated elsewhere [

12,

13,

14,

15]. One well-established imaging method suitable for large, non-transparent objects—and previously applied for the analy-sis of 3D-printed constructs [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]—is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Widely used in medicine for high-contrast imaging of soft tissue, MRI allows rapid image acquisition without contrast agents [

22,

23,

24]. In this study, MRI was combined with mass monitoring, as deviations in mass can serve as an early indication of internal changes that warrant further investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Analytical Workflow

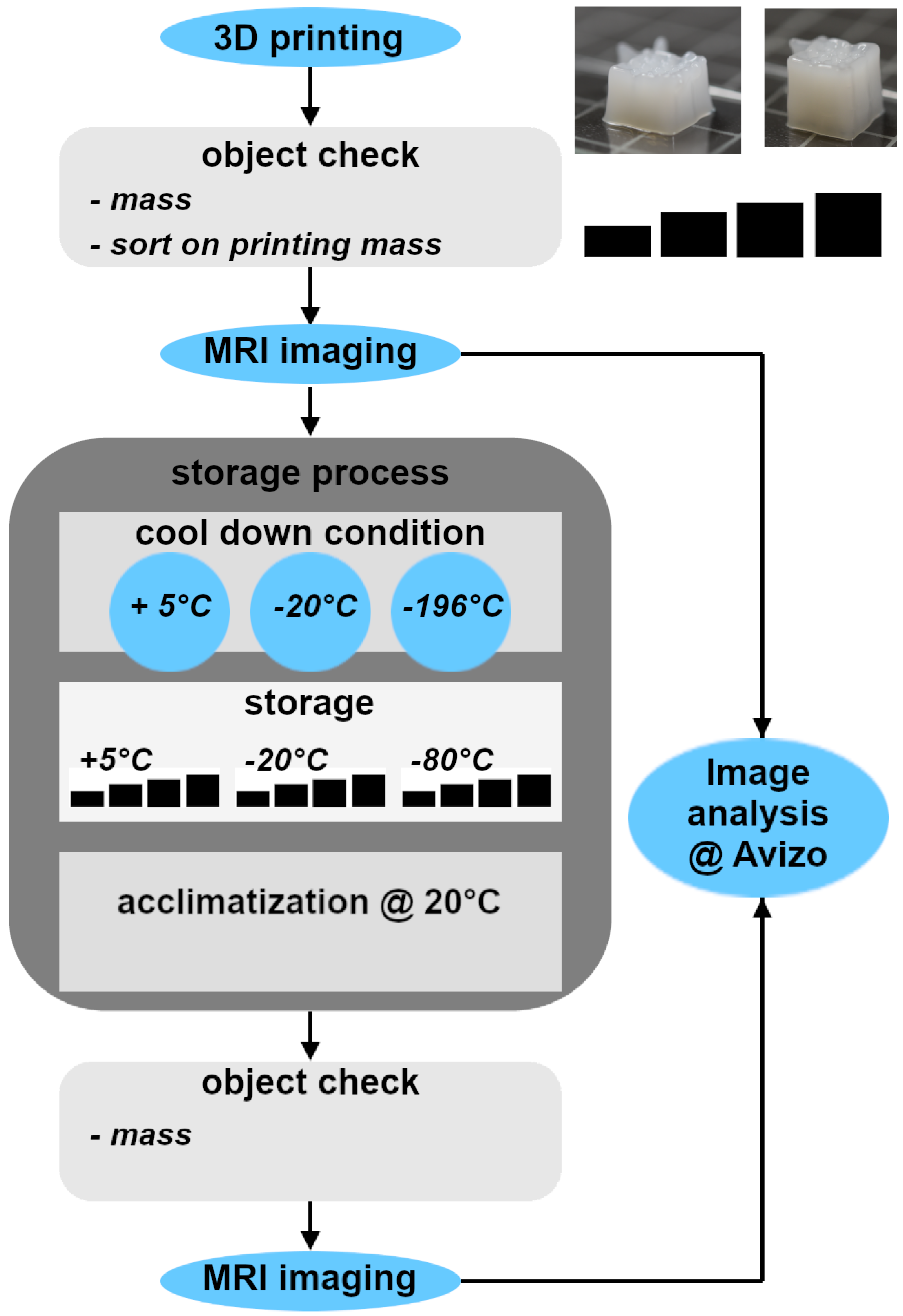

The general workflow combining 3D printing of hydrogels or bioprinting of biomaterials, including cells, initial object characterization via mass and shape, storage, characterization of the stressed objects and consecutive analysis is depicted in

Figure 1.

2.2. Three-Dimensional Printing of Hydrogel

The 3D printing was performed as described in [

17]. In brief, a lattice structure composed of a hydrogel made from an alginate–nanocellulose blend (Bioink “Cellink”, Cellink AB, Gothenburg, Sweden; one single batch of the ready-to-use material; product information available at the manufacturer’s website) was printed at room temperature (22 ± 1 °C) using a pneumatic extrusion-based device (3DDiscovery, regenHU, Villaz-St-Pierre, Switzerland). The printed construct formed a rectangular lattice with outer dimensions of approximately 10 mm × 10 mm in the

x- and

y-directions.

Characterization of the hydrogel was carried out by the manufacturer: its rheological properties range from 2.6 to 7.5 kPa·s at 0.01 s−1 and 1.0 to 1.9 Pa·s at 200 s−1. The pH of the solution is reported as 6.5–7.4. The material was supplied in 3 mL cartridges as a ready-to-use formulation and was applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions without additional preparation steps. It consists of alginate and hydrated cellulose fibrils and is suitable for bioprinting applications, including those using living cells. The accompanying gelation solution, also part of the commercial “Cellink” product, contains 50 mM calcium chloride.

The printed geometry was a rectangular lattice with outer dimensions of about 10 mm × 10 mm in the

x- and

y-directions. The printing height (

z-dimension) of the scaffolds was varied to produce hydrogel lattices of different masses. Gelation via crosslinking with Ca

2+ ions was achieved by immersing the printed objects in the ready-to-use gelation solution (Bioink, Cellink, Gothenburg, Sweden) for 20 min at room temperature (22 ± 1 °C). Excess moisture was removed afterward [

17]. All samples were prepared carefully and consistently, thereby avoiding variations in preparation such as differences in swelling or degree of crosslinking. Varying these parameters is reasonable for future studies once the analytical tools are fully established. For this study, material parameters were therefore considered as constant.

The resulting masses of the printed hydrogel objects ranged from 429 mg to 1010 mg (moist mass). Since the statistical errors of both MRI and mass measurements are known, and confidence in new workflows and analytical methods requires an understanding of both reproducibility and the applicable bandwidth, this approach was chosen. The resulting differences in surface-to-volume ratio may influence structural integrity during storage.

2.3. Hydrogel Mass

Before the mass was determined, the hydrogel lattices were checked for condensation of water droplets on their surface. If present, any excess moisture was carefully removed with a wiping tissue. The masses were recorded at room temperature by special accuracy balances directly after printing and again after storage. Mass changes along the process chain were calculated as follows:

The same approach was chosen for volume changes due to storage at low temperatures.

2.4. Protocol of Sample Treatment: Data Acquisition and Storage Processes

All

samples were positioned individually within a 20 mL single-use vial (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) after the initial weighing. The vials were then sealed with a lid and parafilm and subsequently transferred to the MRI device. For each of the three storage process types, four hydrogel samples with varying masses were selected (

Table 1). Storage conditions were chosen according to common storage scenarios. Uncontrolled cooling was considered as a “worst case scenario”.

Samples designated for cooled storage were placed in a refrigerator at +5 °C for 22–24 h in sealed vials. For storage at −20 °C, samples were kept in a freezer for 22–24 h, also in sealed vials. The third storage process combined rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen with subsequent storage at −80 °C to simulate long-term storage. For this procedure, the single-use vials containing the samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen for 30 min, during which evaporation could occur through the loosely closed lid. Afterwards, the vials were sealed and stored in a freezer at −80 °C for 20 h.

After the designated storage times, all samples were equilibrated to room temperature (20 ± 2 °C) for 60 min in their sealed vials before MRI measurement at +20 °C. Each storage condition was applied to four 3D-printed objects, resulting in n = 4 per condition.

Please note that the objects had different initial masses and dimensions as it is reality of 3D printed hydrogel-based scaffolds. Nevertheless, similar masses allow a direct first impression on the overall reproducibility over the above described workflow.

2.5. Imaging and Image Analysis

An Avance HD III SWB 200 MHz spectrometer capable of imaging, equipped with a MICWB40 20 mm birdcage probe (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany), was used for MRI. All samples were measured at 20 °C in ambient air to achieve high image contrast. The measurement duration of the selected “rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement” (RARE) protocol (Callaghan, 1991; Bernstein et al., 2004) [

22,

23] was 26 min (see

Supporting Information, Table S1), as described in detail in [

17].

In brief, a series of 15 axial slices through the object was acquired with an inter-slice distance of 0.5 mm for both freshly printed and stored lattices. Using an in-plane field of view of 12 mm × 12 mm, 12.5 mm × 12.5 mm, or 13 mm × 13 mm, the chosen geometric parameters ensured sufficient coverage of the sample. A maximum in-plane digital resolution of 47 μm/px (x–y direction) was achieved. By accepting a lower z-resolution of approximately 0.4 mm, the measurement time could be reduced compared to acquiring a full 3D data set, resulting in a so-called 2.5D image data set of the hydrogel lattice.

The measured image stacks before and after storage of the hydrogel lattices were analyzed within the software Avizo Amira (Version 2022.1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). Before analysis, the orientation of the slices was aligned with the “Register Images” function. An image thresholding routine was executed, using the following sequence of standard Avizo operations “Auto Thresholding”, “Closing by Reconstruction”, “Remove small Spots”, “Erosion and Opening” followed by a “Marker-Based Watershed”. The generated data was used to approximate the 3D volume of the stack by considering the inter-slice distance of 0.5 mm appropriately.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Analysis of the 3D Printed Objects

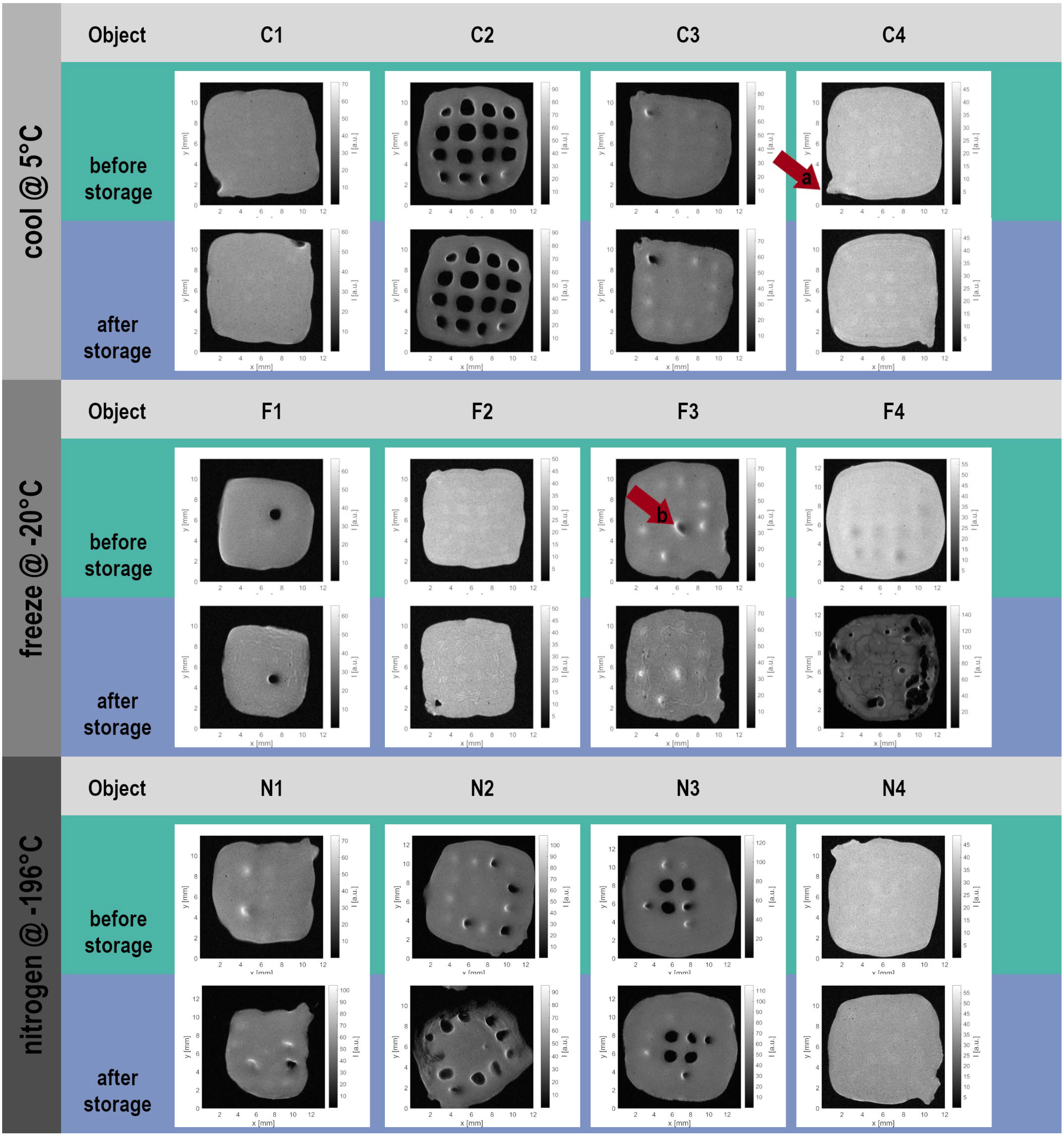

The 2.5D MRI data sets were reconstructed into image stacks and examined for visual changes as an initial qualitative analysis. The observations from four objects under each of the three storage conditions are summarized below and already demonstrate the impact of storage conditions at the qualitative level:

The four objects stored at +5 °C showed high similarity in contour and shape before and after storage (

Figure 2 (C1–C4)). The overall outline and small protrusions at the ends of extruded lines within each layer (example in object “C4

before”, arrow a) remained intact. Even the internal structure was preserved at the spatial resolution of MRI, as seen from the very small air bubbles (small black dots within the object) in object C1. The defined central lattice structure in object C2 was also maintained. In object C3, the lattice holes appeared more pronounced after storage. Brighter regions in the grayscale MR images represent higher water content or greater water-molecule mobility than the surrounding hydrogel, suggesting that the hydrogel may have shrunk while liquid water remained trapped within the channels between printed strands. Similar observations were made for object C4.

Storage at −20 °C (

Figure 2 (F1–F4)) did not affect the overall contour of the hydrogel lattices in three of the four samples. However, the objects exhibited shrinkage, indicating a loss of embedded water. In object F3, a channel that had been filled with air before storage (F3

before, arrow b) appeared filled with water afterward. A closer inspection revealed changes in the internal structure across all samples: water-rich regions appeared brighter, whereas dense areas appeared darker. In object F4

after, pronounced internal damage was visible as dark lines and a row of lattice holes, suggesting reduced water content and potentially crack formation induced by freezing. In contrast, F1

after–F3

after showed marbling patterns with lighter regions, indicating inhomogeneous water distribution and increased transverse relaxation times. Such features are commonly associated with water in less restricted environments. Macroscopically, these may represent water-filled cracks or regions of hydrogel with lower density.

For the objects frozen at −196 °C (

Figure 2 (N1–N4)), the effects of storage were more variable compared to the +5 °C and −20 °C conditions. While the outer contour was largely preserved, the degree of shrinkage differed markedly: object N1 showed substantial shrinkage, whereas N3 and N4 shrank only slightly. Water that filled internal lattice holes before storage was removed and replaced by air. Object N2 shows a minor destruction of the hydrogel starting at one edge of the structure after storage. N4 shows a decent modification of the inner structure.

3.2. Impact of Storage Conditions on Mass and Volume of Hydrogel Lattices

MRI measurements and mass determination were used as orthogonal analytical techniques (

Figure 3) to quantitatively characterize the 3D-printed hydrogel lattices before and after storage. Again, the results obtained after the three storage procedures are compared with the initial state of the printed lattices.

After storage at 5 °C (C1

after–C4

after), the mass and volume of the four hydrogel samples were slightly reduced, corresponding to 91.5–100.3% of the initial volume and 95.9–100.9% of the initial mass (i.e., <8.5% volume loss and <4.1% mass loss). The agreement between the 3D volume calculations based on MR images (Avizo) and the mass measurements was high. The largest percentage deviation occurred in object C1, which had the lowest initial mass among the four samples in this group. Analysis of object C2 (

Supplementary Material, Figure S1) revealed only minor changes. With an initial mass of 642 mg, the calculated volume after storage increased by 0.3%, whereas the measured mass decreased by 1.2%, equivalent to a theoretical difference of 7.7 mg. This deviation may result from false-positive detection of a water droplet or an imaging artifact in the MRI data and provides an estimate of the statistical error of the measurements and subsequent data processing, which is below 5%. Both the volume and mass analyses showed small decreases for samples C3 and C4.

Samples F1–F4 stored at −20 °C lost volume and mass due to freezing effects (

Figure 3B). While three samples (F1–F3) showed shrinkage of 10.8–14.5% and good agreement between volume and mass measurements, one sample exhibited much stronger shrinkage: F4

after retained only 64.0% of its initial 3D volume (36% loss) and 71.6% of its initial mass (28.4% loss), indicating substantial water loss accompanied by deformation. Notably, F4 was the sample with the highest initial mass in the F-series. The complementary nature of the two analytical methods becomes clear: although mass determination provides high precision, it cannot reveal local structural changes within the samples. Non-destructive imaging techniques are required to obtain internal structural insight.

Object F4

after (

Figure S2) showed not only an increase in porosity in the MR images, but also darker ridges between larger bright regions. The outer surface appeared rough, whereas it had appeared smooth before storage (

Figure 2, F4

before). Such roughness introduces uncertainty in volume calculations, as the inter-slice distance of 0.5 mm is relatively large compared to the size of the surface irregularities detected within the

xy-slices. Consequently, mass may serve as a more accurate integral measure under these circumstances. MRI, however, provides crucial information about the internal structural integrity of the hydrogel, as reflected in the grayscale image contrast. The MR signal intensities of the darker ridges and brighter regions differ substantially within the hydrogel cube. Whereas mass offers only a single integrated value, MR imaging enables segmentation of these regions and identification of internal structures or defects. For more detailed analyses, MRI with higher spatial resolution and optimized contrast parameters should be considered, potentially using higher magnetic fields.

The mass loss of samples N1–N4 stored at −196 °C showed good reproducibility: 91.4–93.8% of the initial mass was retained after storage (

Figure 3C). The 3D volume analysis in Avizo agreed well with the mass measurements for two samples (N3 and N4). For the two smaller objects, volumes of 72.2% (loss: 27.8%, N1

after) and 105.8% (apparent divergence: −5.8%, N2

after) were calculated. N1 and N2 clearly illustrate the limitations of the analytical approach and are therefore included in the study: While the increased volume of N2 is a false positive estimation with numerical errors on the order of a few percent, the large loss for N1 possibly hints at unrecorded parts of the object N1

after. Parts of the object might be lost either during acquisition or during thresholding: As the sample N1 is one of the low-mass objects (initial mass 566 mg, i.e., small height along

z in comparison to the

x and

y dimensions) and shrinkage in the axial plane is visible in the images in

Figure 2, a shrinkage along

z will increase the uncertainty of volume calculation in Avizo. The measurement was performed with an inter-slice distance of 0.5 mm, which may have resulted in outer regions of the scaffold falling between slices and therefore being missed. Furthermore, in slice 2 of N2

after (

Figure S3), a shadow is visible; however, the area detected by the software for volume calculation is defined by a user-selected threshold, which may lead to false-positive errors. Depending on the chosen threshold, this numerical error can vary considerably, and therefore the selection of the threshold requires particular attention during data analysis.

4. Discussion

The workflow combining MRI and mass measurements was chosen to monitor the impact of different hydrogel storage processes in terms of shape fidelity, internal structural preservation, and mass conservation—critical quality attributes for product stability. In addition, both techniques, MRI and weighing, are available in medical environments. Beyond the costly clinical MRI scanners used for human imaging, low-field MRI systems based on permanent magnets are available and could be well suited for quality control of scaffolds. While the surfaces of extrusion-printed 3D objects are somewhat irregular—and the volume calculated from MR images in Avizo depends strongly on the geometric MRI parameters—mass determination is straightforward but provides only global information. For this study, which used geometrically simple objects, mass therefore served as an independent and complementary analytical tool.

For gentle storage at +5 °C, excellent agreement between mass and volume data was achieved. After freezing at −196 °C, shrinkage in the z-direction was observed, which represents the smallest dimension of the low-mass hydrogels. In this case study, the mass measurements indicated that low-resolution 2.5D MRI reaches its limits in approximating the volume of complex three-dimensional objects. These limitations may be mitigated by full 3D imaging, ideally at higher magnetic field strengths to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The advantage of non-destructive imaging for assessing the internal structure of non-transparent objects became particularly clear for the hydrogels stored at −20 °C: MRI detected changes within the interior of the hydrogels, whereas mass measurements only revealed higher mass loss in those objects with larger initial mass.

A limitation of this preliminary case study—while demonstrating the potential of combined analytical approaches—was the spatial resolution of the 2.5D MRI protocol. Short measurement times were required to minimize moisture loss from the hydrogels, but this also introduced uncertainty in volume estimation. Future work may focus on elucidating the nature of structural changes induced by freezing and storage, which will require further optimization of MRI parameters. Moreover, deformed or more complex structures could be characterized using advanced MRI techniques. Additional opportunities lie in applying sophisticated data-analysis strategies, such as those developed for image recognition in human imaging [

25,

26].

5. Conclusions

Complementary analytical tools—mass measurement and MRI—revealed the impact of storage on 3D-printed hydrogels. The storage conditions significantly affected both the mass and volume of the hydrogel lattices, as detected by weighing and volume reconstruction, respectively. While the overall shape of the prints was preserved, water-filled regions were emptied due to freezing processes. Beyond these macroscopic measures, MRI also revealed internal structural changes within the hydrogels: in one sample, dark lines indicated crack formation, whereas in others, bright regions suggested areas of lower hydrogel density, pointing to density inhomogeneities within the cross-linked lattices.

These two orthogonal methods may provide a suitable workflow for rapid, non-destructive characterization of bioprinted hydrogels. Further methodological refinement could enable at-line quality control of artificial tissues and potentially allow post-implantation monitoring via MRI.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152312648/s1, Figure S1: MR images of object C2 before (C2before) and after (C2after) the storage at 5 °C.; Figure S2: Detailed view of object F4

after after the storage at −20 °C, Figure S3: Object N1

after after the storage at −196 °C/−80 °C. Table S1: Main parameters of the MRI RARE sequence applied in the study.

Author Contributions

B.S.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft—review and editing. S.G.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft—review and editing. G.G.: Investigation, Writing—original draft—review and editing. J.H.: Writing—original draft—review and editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as project SOP_BioPrint under contract number 13XP5071B. Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is kindly acknowledged for financial support of the instrumental facility Pro2NMR at KIT.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nicolas Schork for assisting with the MRI measurements and Polina Bruck for supporting the image analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| cQA | Critical quality attributes |

| ATMP | Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products |

References

- Hunsberger, J.; Harrysson, O.; Shirwaiker, R.; Starly, B.; Wysk, R.; Cohen, P.; Allickson, J.; Yoo, J.; Atala, A. Manufacturing Road Map for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Technologies. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, R.P.; Ruck, S.; Medcalf, N.; Rafiq, Q.A. Decentralized manufacturing of cell and gene therapies: Overcoming challenges and identifying opportunities. Cytotherapy 2017, 19, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criswell, T.; Swart, C.; Stoudemire, J.; Brockbank, K.; Floren, M.; Eaker, S.; Hunsberger, J. Shipping and Logistics Considerations for Regenerative Medicine Therapies. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iancu, E.M.; Kandalaft, L.E. Challenges and advantages of cell therapy manufacturing under Good Manufacturing Practices within the hospital setting. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 65, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, E.R. Disrupting vaccine logistics. Int. Health 2021, 13, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windisch, J.; Reinhardt, O.; Duin, S.; Schütz, K.; Rodriguez, N.J.N.; Liu, S.; Lode, A.; Gelinsky, M. Bioinks for Space Missions: The Influence of Long-Term Storage of Alginate-Methylcellulose-Based Bioinks on Printability as well as Cell Viability and Function. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2300436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, S.; Villeneuve, S.; Mondor, M.; Uysal, I. Time–Temperature Management Along the Food Cold Chain: A Review of Recent Developments. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.; Ehrhart, F.; Zimmermann, D.; Müller, K.; Katsen-Globa, A.; Behringer, M.; Feilen, P.J.; Gessner, P.; Zimmermann, G.; Shirley, S.G.; et al. Hydrogel-based encapsulation of biological, functional tissue: Fundamentals, technologies and applications. Appl. Phys. A 2007, 89, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, G.; Lee, K.H.; Magalhães, R.; Wen, F.; Gouk, S.S.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Kuleshova, L.L. Cryoreservation of alginate–fibrin beads involving bone marrow derived mesenchymal stromal cells by vitrification. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, S.; Wu, Y.; Chakraborty, N.; Mohanty, P.; Ghosh, G. Impact of alginate concentration on the viability, cryostorage, and angiogenic activity of encapsulated fibroblasts. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 65, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANSI/PDA Standard 02-2021; Hawkins, B.; Loper, K.; Abazari, A.; Alder, B.; Arcidiacono, J.A.; Ballica, R.; Brower, S.; Elliott, J.T.; Gayed, B.; Goh, C.W.; et al. Cryopreservation of Cells for Use in Cell Therapies, Gene Therapies, and Regenerative Medicine Manufacturing: An Introduction and Best Practices Approach on How to Prepare, Cryopreserve, and Recover Cells, Cell Lines, and Cell-Based Tissue Product. PDA (Parenteral Drug Association): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021.

- Chua, K.J.; Chou, S.K. On the study of the freeze–thaw thermal process of a biological system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 3696–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzinger, S.; Limbrunner, S.; Hubbuch, J. Automated image processing as an analytical tool in cell cryopreservation for bioprocess development. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadiut, O.; Gundinger, T.; Pittermann, B.; Slouka, C. Spatially Resolved Effects of Protein Freeze-Thawing in a Small-Scale Model Using Monoclonal Antibodies. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.; Hubbuch, J. Temperature Based Process Characterization of Pharmaceutical Freeze-Thaw Operations. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 617770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesti, M.; Eberhardt, C.; Pagliccia, G.; Kenkel, D.; Grande, D.; Boss, A.; Zenobi-Wong, M. Bioprinting Complex Cartilaginous Structures with Clinically Compliant Biomaterials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 7406–7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmieg, B.; Gretzinger, S.; Schuhmann, S.; Guthausen, G.; Hubbuch, J. Magnetic resonance imaging as a tool for quality control in extrusion-based bioprinting. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 17, 2100336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gretzinger, S.; Schmieg, B.; Guthausen, G.; Hubbuch, J. Virtual Reality as Tool for Bioprinting Quality Inspection: A Proof of Principle. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 895842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, S.; Schmieg, B.; Wendling, P.; Guthausen, G.; Hubbuch, J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Time-Dependent Wetting and Swelling Behavior of an Auxetic Hydrogel Based on Natural Polymers. Polymers 2022, 14, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatamikia, S.; Zaric, O.; Jaksa, L.; Schwarzhans, F.; Trattnig, S.; Fitzek, S.; Kronreif, G.; Woitek, R.; Lorenz, A. Evaluation of 3D-printed silicone phantoms with controllable MRI signal properties. Int. J. Bioprinting 2025, 11, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangal, M.; Anikeeva, M.; Priese, S.C.; Mattern, H.; Hövener, J.-B.; Speck, O. MR based magnetic susceptibility measurements of 3D printing materials at 3 Tesla. J. Magn. Reson. Open 2023, 16–17, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, P.T. Principles of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Microscopy; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, M.A.; King, K.F.; Zhou, X.J. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences; Academic Press, Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blümich, B. NMR Imaging of Materials; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Modersitzki, J. Numerical Methods for Image Registration; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggrawal, H.O.; Andersen, M.S.; Modersitzki, J. An Image Registration Framework for Discontinuous Mappings Along Cracks. In Biomedical Image Registration; Špiclin, Ž., McClelland, J., Kybic, J., Goksel, O., Eds.; WBIR 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).