Abstract

The growing demand for accessible communication technology for the deaf and hearing-impaired illustrates the importance of systems for recognizing sign language that are both accurate and deployable on resource-constrained platforms. Many existing deep learning solutions deliver strong recognition performance but rely on computationally intensive architectures, making them unsuitable for real-time use in mobile and embedded environments. This research introduces a lightweight framework that combines Tailored MobileNet with a Self-Attention module for discriminative feature extraction and integrates optimized machine learning classifiers for efficient prediction. Systematic hyperparameter optimization using Grid Search and cross-validation showed the k-Nearest Neighbors classifier as the most successful classifier. The proposed model was evaluated on four image-based datasets and on one video dataset demonstrating the robustness and effectiveness of the approach, with 99% accuracy across multiple datasets. By achieving high recognition accuracy, model compactness, and computational efficiency on benchmark datasets, this research provides a foundation for the development of practical, scalable sign language recognition systems, highlighting a promising direction for future work in mobile and embedded assistive technologies.

1. Introduction

Sign language is a vital communication tool for individuals with hearing and speech impairments, incorporating gestures, emotions, and nonverbal cues with regional variations [1]. Despite its importance, barriers persist, particularly in low-income regions with limited resources. Over 1.5 billion people experience hearing loss globally, including 430 million with disabling conditions, a number projected to surpass 700 million by 2050 [2]. People with hearing or speech disabilities often face challenges in conveying their thoughts, ideas, and needs through general languages such as English, Arabic, Iranian, Persian, Greek, Hindi, Urdu, or Bangla due to their inability to speak [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. To overcome this, they rely on a specialized system of signs, postures, and symbols, which incorporate facial expressions, body movements, head gestures, and hand and finger postures, collectively known as sign language [11,12]. The number of hearing-impaired individuals in the workforce has been steadily increasing. According to WHO (World Health Organization), 5% of the global population, equating to 466 million people, belong to this community, including 432 million adults and 34 million children. Consequently, the hearing-impaired community must learn sign language to convey their needs and establish effective communication with both hearing and non-hearing-impaired individuals for essential purposes such as education, healthcare, and employment. Advanced technologies like machine learning and computer vision have enabled progress in sign language recognition (SLR) [13], fostering inclusivity by bridging communication gaps without human interpreters [14]. However, existing sign language recognition approaches often require high computational resources to achieve strong accuracy, which limits their practical deployment on mobile or embedded devices [15,16,17]. Although these models often achieve high accuracy under controlled conditions, their large size makes them unsuitable for mobile deployment. Consequently, there exists a critical gap between high-accuracy models developed in research and the practical requirements of real-world, on-device SLR applications, which demand a careful balance of accuracy, speed, and model compactness. Addressing this trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency remains a major challenge in SLR. This study addresses the dual challenge of achieving robust recognition accuracy and computational efficiency in SLR. It emphasizes the development of a lightweight and portable SLR model optimized for mobile and embedded devices.

This study aims to bridge the gap between recognition accuracy and computational efficiency for SLR by proposing a novel hybrid architecture specifically designed for deployment on resource-constrained mobile and embedded devices. Our primary objective is to achieve accuracy comparable to large-scale models while reducing the computational footprint by orders of magnitude. We propose a tailored MobileNet architecture with a Self-Attention module, combined with a K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifier: the Tailored MobileNet–Self-Attention–KNN (TMSK) model. The TMSK model achieves a significant reduction in memory usage while preserving state-of-the-art recognition accuracy.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Lightweight Framework (TMS): We propose the ‘Tailored MobileNet with Self-Attention’ (TMS) framework, specifically designed to tackle the problem of efficient SLR on resource-constrained mobile devices. TMS integrates a MobileNet backbone with a Self-Attention module, which efficiently captures spatial and contextual features while minimizing computational overhead. This makes the framework suitable for real-world SLR applications where model size and inference speed are critical.

- Modular Classification: To address the challenge of deploying SLR systems in real-time applications, we design a modular classification approach that allows for integration with various machine learning classifiers. Through systematic hyperparameter optimization using Grid Search and cross-validation, the k-Nearest Neighbors classifier was identified as the optimal choice for achieving a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Its integration with the TMS framework forms the TMSK model, which is shown to be highly effective for on-device use.

- Cross-Dataset Robustness: The framework’s robustness is rigorously validated across multiple datasets to address the generalization problem in SLR. By testing the model on four image-based datasets and one video dataset, we demonstrate strong generalization across different signing modalities, languages, and data types. This ensures that the model can be deployed effectively in diverse real-world settings, such as multilingual communities and assistive technologies, where variability in sign language use is a major challenge.

This document is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review on the topic, while Section 3 describes the methodology, including dataset details, preprocessing and augmentation, model design, and classifier optimization via Grid Search. Section 4 presents the experimental evaluation across multiple datasets, highlighting both recognition accuracy and memory efficiency. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Related Work

Numerous studies have explored SRL, with recent research introducing a new variation in sign structure that aligns subunits with phonology in spoken language [18]. Stokoe paradigm defines sign language components based on hand shape, alignment, and motion [19]. Hand shape, which conveys specific meanings, is determined by palm orientation and finger positioning and can be either static or dynamic. A static posture, captured in a single image frame, can fully represent the meaning of a sign, including in continuous signing scenarios [18]. Capturing sequential frames is crucial for understanding the complete context of a dynamic gesture, a concept referred to as the movement-hold framework. While the relationship between hand motions and positions has been effectively represented for two-handed signs, these approaches are particularly efficient for one-handed signs.

Researchers have predominantly employed sensor-based systems and vision-based sensors for gesture-based SLR. Vision-based systems are favored for their benefits, including affordability, portability, and user-friendliness. Tangsuksant et al. propose a method for American Sign Language (ASL) recognition using 3D geometric features and the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) classification. The system utilizes a glove with colored markers and two cameras to capture 3D coordinates, achieving 95% accuracy [20]. Ragab et al. [21] present a SLR system using the Hilbert Curve-based Model. It segments hand images, applies the Hilbert curve to extract features, and classifies gestures using Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Random Forest (RF). A significant number of researchers are focused on creating SLR systems utilizing various statistical, mathematical models, and machine learning and deep learning techniques [18,19,22,23,24,25]. Morillas-Espejo et al. proposed a real-time platform for Spanish SLR, utilizing Convolutional Neural Network (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Network (RNNs), and Vision Transformers for finger-spelling interpretation, achieving 79.96% accuracy on unseen data [26]. Liu et al. employed a multi-stage approach that integrated Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC) with 3D-ResNet, attaining word error rates (WER) of 36.7% on the CSL dataset and 32.7% on the RWTHPHOENIX-Weather dataset [27]. Koller et al. integrated CNN and HMM into a hybrid model, reducing WER by 20% across three benchmark datasets [28,29]. Cui et al. proposed a model incorporating 3D-CNN and attention mechanisms, attaining the accuracy of 0.95 on the ChaLearn dataset [30].

Huang et al. introduced a pooling-based approach for extracting temporal features [31], whereas Qambrani et al. [32] propose a hybrid pipeline for static Auslan sign language digit recognition using CNNs and classical classifiers, including SVM and Random Forest (RF). The model achieves high accuracy in recognizing hand gestures from a grayscale dataset of 6000 images. Naglot and Kulkarni [33] proposed a real-time American SLR system using the Leap Motion Controller. The system captures hand gestures through the Leap Motion sensor and classifies them using a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) neural network. The model achieves a recognition accuracy of 96.15% for 26 ASL alphabet signs. Chowdhury et al. [34] proposed a Hybrid Efficient Convolution (HEC) model integrating EfficientNet-B3 for Isolated Dynamic SLR (IDSLR) in cluttered backgrounds, achieving 93.17% accuracy on the BdSL-OPA-23-GESTURES dataset. Kurdish Sign Language (KuSL) classification model [35] demonstrates superior accuracy and adaptability, achieving 99.05% training accuracy and outperforming prior KuSL detection approaches. Khuzayem et al. [36] proposed android-based system utilizes deep learning techniques to translate isolated Saudi Sign Language (SSL) into text and audio. Diksha Kumari and Anand [37] utilized MobileNetV2 with an attention-based LSTM for gesture recognition, achieving 84.65% accuracy on the WLASL dataset and outperforming several state-of-the-art methods. Abdul et al. [38] employed an attention-based LSTM model integrated with MediaPipe for Arabic Sign Language recognition, achieving over 85% accuracy using a dataset of fifty common gestures collected from multiple volunteers.

Saha et al. [39] introduced a novel MAdaline Neural Network-based Model for American SLR. This model uses an advanced feature set and removes the need to crop irrelevant background by leveraging the MAdaline network. It recognizes the ASL alphabet (A-Z) and outperforms standard algorithms in accuracy. Hariharan et al. developed a deep learning-based ASL recognition system using a modified ResNet-101 CNN [40,41]. The method includes image pre-processing, edge-based segmentation, and classification, achieving 97% accuracy and outperforming other models like ResNet-50 and ResNet-18. It accurately identifies all 36 ASL signs, including numbers and alphabets. Nikolas Adaloglou et al. [42] introduced a SLR system utilizing deep learning techniques. Their approach relied on computer vision methods to interpret sign language from continuous video input. Murred et al. [43] proposed a deep learning-based sign language recognition model. Using a densely connected CNN trained on 1300 labeled sign language images, their system achieved 95% accuracy in gestures classification. The primary aim was to demonstrate how unsegmented video sequences could be translated into glosses, despite the challenge that glosses typically represent shorter time spans than the full actions in the videos. Dongxu Li et al. [44] developed a deep learning method for SLR using the large-scale WLASL dataset, which includes over 2000 ASL phrases. Multiple models were tested for word-level sign recognition, achieving a top-10 accuracy of 62.63% across the dataset.

3. Materials and Methods

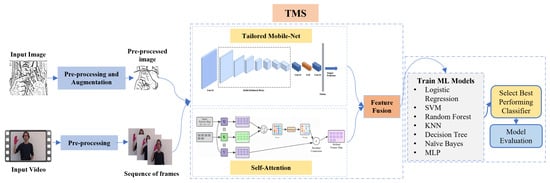

The proposed SLR framework follows a structured pipeline designed to balance recognition accuracy with computational efficiency for deployment on resource-constrained devices. As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall process encompasses four main stages: (1) data acquisition (2) preprocessing and data augmentation, (3) feature extraction using a tailored MobileNet architecture with Self-Attention mechanism, feature fusion and embedding, and (4) classification using optimized machine learning models.

Figure 1.

Overall pipeline of the proposed SLR framework.

The process begins with the acquisition of sign language data from a data source that might contain static images or dynamic video sequences. These inputs undergo careful preprocessing to normalize size, enhance quality, and augment diversity while preserving the semantic meaning of gestures. The preprocessed data is then fed into our hybrid feature extractor, which combines the efficiency of MobileNet’s depthwise separable convolutions with the contextual modeling capabilities of Self-Attention. This fusion generates discriminative feature representations that capture both local spatial patterns and global dependencies within sign gestures.

The extracted features are subsequently used to train multiple machine learning classifiers, with hyperparameters systematically optimized through grid search and cross-validation. This modular approach allows for selecting the optimal classifier based on performance and computational constraints.

The following subsections provide detailed descriptions of each component: Section 3.1 introduces the diverse datasets employed for evaluation; Section 3.2 outlines the preprocessing and augmentation strategies performed on image-based datasets or video dataset; Section 3.3 details the tailored MobileNet + Self-Attention architecture (TMS); and Section 3.4 explains the classifier optimization process.

3.1. Datasets

In this work, we utilized two types of datasets: image-based and video-based.

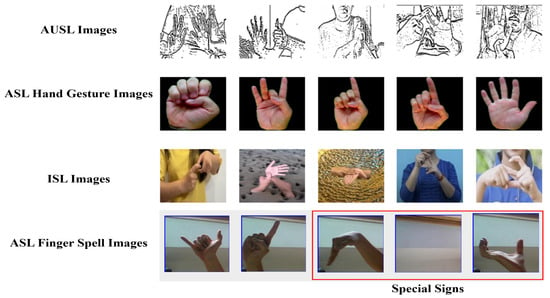

Four image-based datasets are employed: AUSL (Australian Sign Language) (AUSL https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rithwikchhugani/auslan-sign-language-fingerspelling-dataset (accessed on 3 September 2025)), ASL MNIST (American Sign Language Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology), (ASLM https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ayuraj/asl-dataset (accessed on 3 September 2025)) ASL Finger Spell (ASLF https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/grassknoted/asl-alphabet (accessed on 3 September 2025)), and ISL (Indian Sign Language) (ISL https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/soumyakushwaha/indian-sign-language-dataset (accessed on 3 September 2025)). All datasets were downloaded from Kaggle, an open-source repository that provides public access for research use. Each dataset contains static hand gesture images representing alphabets, numbers, or special signs, covering a wide range of scales, complexities, and background variations.

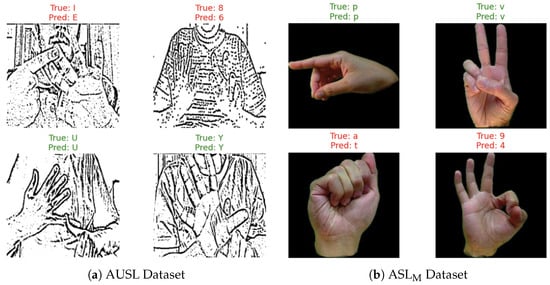

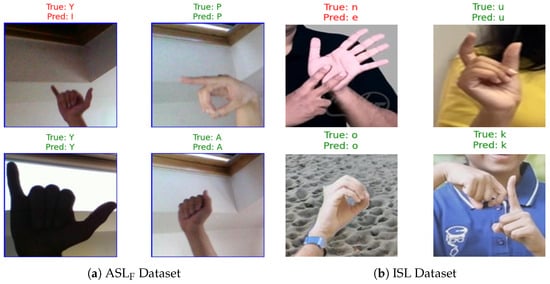

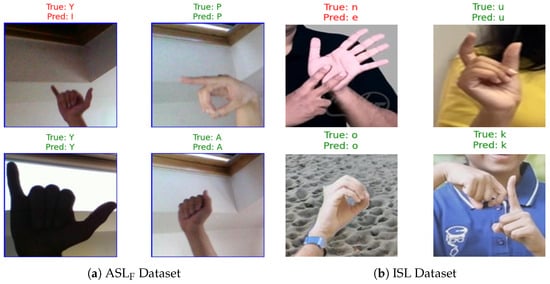

As detailed in Table 1, the selected datasets cover a broad range of sign language representations. AUSL and ASLM include both alphabetic and numeric signs, whereas ASLF focuses on finger-spelled letters and special signs such as (del, space, nothing). ISL dataset is smaller in size, it adds complexity through diverse backgrounds and variations in sign execution. This diversity provides a strong basis for evaluating the robustness and generalization ability of the proposed framework. Representative samples from each dataset are shown in Figure 2, illustrating the visual challenges addressed in this study.

Table 1.

Summary of image datasets used in this study.

Figure 2.

Samples of Image Datasets.

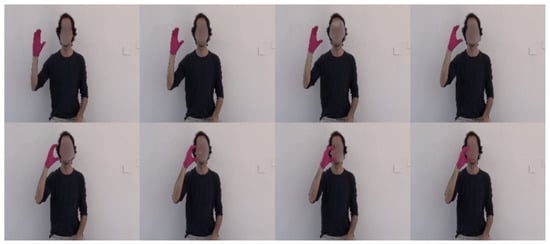

To evaluate the framework on dynamic gestures, we employed the LSA64 video dataset for Argentinian Sign Language. Unlike static image datasets, LSA64 presents the additional challenges of temporal variation, motion blur, and inter-frame differences. The dataset contains 3200 video samples representing 64 distinct signs (LSA64 complete sign list available at https://facundoq.github.io/datasets/lsa64/ (accessed on 3 September 2025)) performed by 10 non-expert subjects, covering common nouns and verbs used in everyday communication.

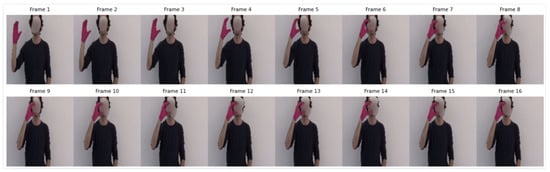

As summarized in Table 2, the dataset incorporates significant variability through different recording environments (outdoor/natural lighting vs. indoor/artificial lighting) and sign types (one-handed and two-handed). Participants wore fluorescent gloves to facilitate hand segmentation, maintaining consistent hand detection across varying background conditions. This setup ensures that the primary challenge remains in recognizing hand shapes and movements rather than dealing with segmentation artifacts. Representative frames demonstrating the visual characteristics of the dataset are shown in Figure 3, with faces blurred to ensure privacy.

Table 2.

LSA64 Dataset: Sign Vocabulary and Characteristics.

Figure 3.

Sample frames extracted from LSA Dataset (the faces are blurred for privacy reasons).

3.2. Preprocessing and Augmentation

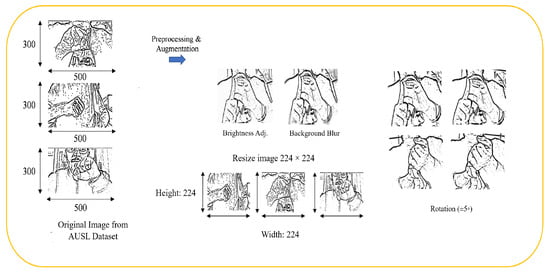

The preprocessing pipeline was carefully designed to improve the quality of the input data while ensuring that the semantic meaning of sign gestures remained unchanged. For image-based datasets, hand regions were localized using MediaPipe Hands to detect landmarks and compute bounding boxes around the region of interest. The preprocessing steps are described below:

Image resizing: Each detected hand region was cropped with a fixed 20-pixel margin, this value was chosen empirically to ensure full hand coverage while maintaining a balance between complete hand inclusion and minimal background, which produced stable and accurate crops across all gesture classes. The cropped images were then resized to pixels to meet the model’s input requirements.

Data augmentation: Controlled augmentations were applied to improve robustness, including small random rotations (), Gaussian blurring, and mild brightness adjustments. The rotation operation is defined as:

where X is the original image, denotes the rotation transformation, and is the augmented output.

Normalization: All images were normalized to the range [0, 1] using pixel-wise scaling:

where I represents the raw pixel intensity values. This normalization stabilizes optimization, accelerates convergence, and prevents numerical instabilities during training.

Horizontal or vertical flips were deliberately avoided in this study. While some prior works in SLR applied such flips merely as a means of dataset enlargement [45,46], later analyses have shown that flipping can invert hand orientation and handedness, thereby altering the semantic meaning of signs [47]. Figure 4 represents the preprocessing and augmentation steps.

Figure 4.

Preprocessing and Augmentation Steps for Image-base Datasets.

To prepare the video dataset for model training, we extracted a fixed number of frames from each video in a consistent manner. Each video contains 60 frames; using all of them would introduce substantial redundancy and greatly increase the computational cost. Therefore, (N = 16) frames sampling strategy was implemented using uniform temporal spacing throughout the duration of each video to ensure a consistent representation of all gesture phases: early (onset), middle (peak), and late (offset). In [48], the LSA64 dataset was used for SLR and 20 frames were selected per video, achieving 93.7% accuracy. We aimed to reduce the number of frames to reduce the computational cost, still preserving the key temporal dynamics of the sign language gestures. While the selection of 16 frames was not empirically optimized, we manually verified that the 16 frames capture the dynamics of the gesture well, with no repetition of frames. Additionally, our approach achieved higher recognition accuracy, indicating that the chosen frames were sufficient to capture the critical temporal information necessary for accurate recognition. Decreasing this number may degrade the performance. The sampling positions were calculated using

where T is the total number of frames in the video. This mechanism was included in the preprocessing pipeline purely for robustness and generalizability, ensuring compatibility with other datasets that may contain fewer than 16 frames per sample. Each frame was resized to pixels, converted from BGR to RGB, normalized to the range [0, 1], and cropped at the center () to focus on the region of interest. Finally, each video was stored as a four-dimensional array , where N is the number of frames, H and W are the spatial dimensions, and 3 corresponds to the RGB color channels. Figure 5 represents extracted frames from a video.

Figure 5.

Frames extracted from LSA Dataset.

This 4D representation is necessary because it preserves both spatial information (what appears in each frame) and temporal information (how frames change over time). If frames were saved only as separate images, the model would treat them as independent pictures, thereby losing the temporal dynamics that are essential for video data processing. By keeping frames together as one sequence, the dataset provides a consistent and structured input format for deep learning models that must learn from both appearance and motion.

3.3. Tailored MobileNet Self-Attention Model (TMS)

The proposed feature extraction model integrates a tailored MobileNet backbone with a self-attention mechanism. This design leverages the computational efficiency of MobileNet’s depthwise separable convolutions, which significantly reduce model complexity and inference time while maintaining high representational power. Meanwhile, self-attention mechanism enhances the network’s ability to capture long-range spatial dependencies and focus on semantically important hand regions, such as finger articulation and orientation, while suppressing irrelevant background information. This selective focus improves feature separability and reduces confusion between visually similar gestures, which leads to higher recognition accuracy. As a result, the combined architecture achieves an optimal balance between lightweight computation and discriminative feature learning, making it well-suited for real-time sign language recognition applications.

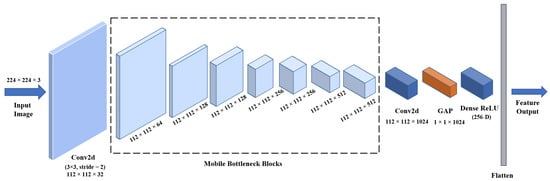

3.3.1. Tailored MobileNet

To efficiently extract visual features from sign language images, we employed a Tailored MobileNet backbone. Unlike using a pre-trained MobileNetV2, our tailored lightweight MobileNet variant is designed from scratch, employing depthwise separable convolutions and pointwise convolutions with customized stride handling, consistent batch normalization after both depthwise and pointwise layers, and an additional dense projection layer, which greatly reduced computational complexity while preserving expressive capacity [49]. This design forms the lightweight backbone of the TMS feature extractor compared to the standard MobileNet. Instead of applying a standard convolution across all channels, the operation is divided into two parts: (1) a depthwise convolution that filters each input channel separately, and (2) a pointwise () convolution that combines the output across channels.

Figure 6 illustrates the proposed Tailored MobileNet architecture, consisting of an initial convolutional block, seven bottleneck modules, and a final stage that applies a Global Average Pooling (GAP) and a Dense layer for feature embedding. GAP provides a smoother and more generalizable representation by averaging spatial activations, thus reducing sensitivity to local outliers or noise. This design choice aligns with established practices in lightweight CNN architectures [50,51].

Figure 6.

Tailored MobileNet architecture for visual feature extraction.

Given an input feature map , the Tailored MobileNet architecture extracts efficient spatial features through a series of operations. First, an initial convolutional block is applied:

where stride (2, 2) is used for spatial downsampling.

The downsampled features are passed through multiple bottleneck modules. Instead of applying standard convolution across all channels, each bottleneck module performs depthwise convolution followed by pointwise convolution. For a feature map at layer ℓ, the depthwise convolution applies a spatial kernel independently to each input channel:

where denotes the depthwise kernel applied to the k-th channel. This step focuses on extracting localized spatial patterns within each channel.

Next, a pointwise convolution is performed to recombine the channel information and produce richer feature interactions:

where is a convolutional filter that projects the input channels into output channels. Multiple bottleneck modules progressively extract and refine features while reducing spatial dimensions through stride operations.

Finally, to reduce the spatial dimensions while retaining global context, a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer is applied:

where and are the spatially reduced dimensions after bottleneck processing. The resulting descriptor (with ) is compact and lightweight, capturing essential spatial information while maintaining low computational cost.

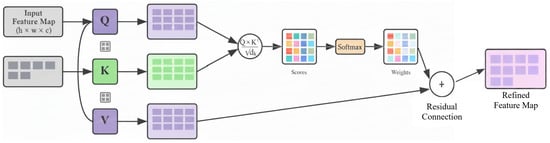

3.3.2. Self-Attention Block

Although MobileNet efficiently captures localized spatial features, it has limited capacity to model long-range dependencies across different regions of the image. To address this, we incorporated a Self-Attention block, inspired by the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [52], which enables the network to assign adaptive importance to spatial regions and model global context relationships. Figure 7 illustrates the self-attention block.

Figure 7.

Self-Attention Architecture.

In parallel to the MobileNet branch, a Self-Attention block processes the preprocessed input image to capture global spatial dependencies. Given the input feature map , it is reshaped into a sequence representation , where represents the total number of spatial locations.

Three learnable linear projections are applied to compute the query (Q), key (K), and value (V) matrices:

where are trainable projection matrices that map features from the input channel dimension to the latent dimension d. The query matrix represents what each spatial location queries, the key matrix represents the searchable content, and the value matrix contains the feature information to be aggregated. This transformation maps the spatial features into a latent space suitable for attention computation.

Next, similarity scores between spatial locations are obtained using scaled dot-product attention:

where represents the raw similarity scores computed as dot products between query and key vectors, and is the dimension of the key vectors. The value of d was set to 128, corresponding to the dimensionality of the query and key vectors in the Self-Attention block. This configuration strikes a balance between feature expressiveness and computational efficiency, considering that the input to the attention block contains 256 feature channels. The scaling factor prevents the dot products from growing excessively large, stabilizing the gradient flow. The softmax function normalizes these scores into a probability distribution, ensuring that the weights sum to one along each row and highlight the most relevant spatial dependencies.

The attention weights are then used to compute a weighted combination of value vectors:

where is the attention-weighted feature output that aggregates global contextual information across the entire feature map. To stabilize learning and preserve original spatial information, a residual connection is added:

where combines the original features with attention-refined features. The sequence is reshaped back to spatial form and flattened to produce the final attention descriptor . This parallel module ensures that the Self-Attention block independently captures long-range spatial dependencies complementary to the MobileNet features. The self-attention module adds minimal computational overhead, as it operates on a downsampled feature map with a reduced latent dimension. The resulting increase in FLOPs is negligible compared to the base MobileNet, while enhancing feature discriminability and maintaining a lightweight, efficient architecture. Table 3 shows the computational cost in FLOPs and GFLOPs for different components. Tailored MobileNet is efficient as compared to standard MobileNetV2. The Self-Attention Module adds 1.032 GFLOPs, and the combined TMS model totals 1.647 GFLOPs, with an overhead of 0.16.

Table 3.

FLOPs, GFLOPs, and Overhead for Components.

3.3.3. Feature Fusion

The MobileNet and Self-Attention modules process the input image in parallel, producing complementary feature representations. Unlike traditional late-fusion or ensemble-based pipelines, we perform feature-level fusion by concatenating embeddings from the custom Mobile-Net and the self-attention block before classification. The MobileNet branch outputs a compact descriptor that captures efficient spatial-channel features, while the Self-Attention branch outputs a global descriptor that encodes contextual dependencies.

These two feature modules are concatenated to form a unified representation:

where merges the local and global information from both feature extractors. This feature space allows the fully connected layers to learn complementary information from both the MobileNet () and Self-Attention () branches, improving discriminative power while maintaining computational efficiency.

The concatenated features are further refined through fully connected layers with ReLU activation, normalization, and dropout regularization to form a compact fused feature vector . This final representation effectively combines the efficiency of MobileNet with the global awareness of the Self-Attention stream. This hybrid fusion approach effectively combines the parameter efficiency of MobileNet with the contextual awareness of Self-Attention, making it suitable for robust sign language recognition.

3.4. Machine Learning Classifiers and Hyperparameter Optimization

The fused feature representations () of the MobileNet and Self-Attention hybrid extractor were used to train a diverse set of conventional classifiers. The classifiers considered in this study include Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Naïve Bayes (NB), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). This selection covers a wide range of algorithmic approaches to ensure a complete evaluation.

For each classifier, hyperparameters were systematically optimized using grid search coupled with five-fold cross-validation. The objective of the grid search is to identify the hyperparameter set that maximizes the mean validation accuracy across all folds, thereby ensuring robust and generalizable performance.

Formally, for a given classifier g with hyperparameters , the optimal hyperparameters are determined by

where denotes the classifier instance trained on the i-th training fold and evaluated on the corresponding validation fold . This rigorous process mitigates the risk of overfitting and ensures that the selected hyperparameters yield stable performance.

Cross-validation was employed to ensure reliable and unbiased performance estimation of the machine learning classifiers trained on features extracted using the MobileNet and Self-Attention modules. This process validated the robustness and generalization capability of the classification stage across different data splits. The proposed framework employs a two-stage learning strategy, where the deep network functions as a feature extractor and the KNN serves as the classification layer. This modular separation enables efficient retraining when new gestures are introduced, minimizes overfitting on limited gesture datasets, and enhances generalization to unseen signs. The framework also achieved computational efficiency through its lightweight feature extraction design, combining MobileNet’s compact architecture with the self-attention mechanism to maintain high accuracy with minimal memory requirements Section 4.

4. Results

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed TMS framework across multiple sign language datasets. We first describe the evaluation metrics and experimental setup, followed by detailed performance analysis on both image-based and video-based datasets.

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the model’s performance, we employed four key evaluation metrics commonly used in SLR: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score. Table 4 provides the formal definitions and purposes of each metric.

Table 4.

Evaluation Metrics.

4.2. Experimental Setup

To thoroughly evaluate the proposed framework, we conducted six experiments on image datasets and one on video data, as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Data Splits and Sample Distribution for Image Dataset Experiments.

The experimental design follows a progressive complexity approach:

- Exp #1 establishes baseline performance on the large AUSL dataset;

- Exp #2–4 evaluate cross-dataset generalization;

- Exp #5 evaluates ability to generalize to special sign categories;

- Exp #6 assesses performance when training exclusively on limited, complex data.

For all training and fine-tuning phases, on-the-fly data augmentation was applied by generating two rotated versions () of each image. This in-memory operation effectively tripled the number of training samples per epoch without requiring additional storage. As a result, the effective number of training instances was approximately three times larger than the original dataset sizes reported in Table 5.

In Exp #1, the model was trained and tested on the AUSL dataset, establishing a baseline referred to as the AUSL-trained model. Dataset was divided into 80% training and 20% testing subsets using stratified sampling to preserve class balance. These splits were used for model training and within-domain evaluation. In addition, a 5-fold cross-validation procedure was applied on the training data to verify model stability and reduce bias arising from a single split. In Exp #2, this baseline model was fine-tuned on 80% of the ASLM dataset, referred to as the AUSL+ASL-trained model. During fine-tuning, the early seven layers of the AUSL-trained model were frozen, while the last ten layers and six layers of the newly added dense blocks were made trainable. This strategy aligns with common transfer learning practices, that normally freeze from one third to half of the layers [53,54,55]. Fully connected layers with dropout and batch normalization were integrated to enhance generalization. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of and a batch size of 32, which provided a good balance between stable convergence and efficient memory utilization. The BatchNormalization layers used batch statistics (mean and variance) during training and moving averages of these statistics during inference, ensuring consistent feature normalization and stable performance. An adaptive Reduce-on-Plateau scheduler automatically reduced the learning rate by a factor of 0.5 when the validation loss did not improve for several epochs, helping to stabilize convergence and achieve better fine-tuning performance near the optimal weights. This fine-tuning strategy allowed the model to retain basic visual representations while effectively adapting to variations in ASL signs, since AUSL dataset consists of two-handed signs and ASLM is composed of one-handed signs. This approach is designed to extend the feature space of the model beyond two-hand configurations. Fine-tuning enabled the model to retain knowledge from AUSL while learning additional discriminative features specific to single-hand gestures, resulting in a more comprehensive representation of sign variations. The features extracted from this model were then used to train the previously selected machine learning classifiers and then evaluated on the ASL test set.

The AUSL+ASL-trained model in Exp #3 and 4 was evaluated on the alphabetic subsets of the ASLF and ISL datasets, respectively. Inference was restricted to the shared label space between the training and test datasets. Label mapping was applied to align ISL labels with the corresponding training classes, ensuring consistent evaluation across datasets. While in Exp #5, the model was further fine-tuned on the subset of special sign (SP) of ASLF to allow testing across all sign categories. This configuration allowed us to assess the model’s ability to generalize beyond alphabetic and numeric gestures. Finally, in Exp #6, the model was completely trained on 80% of the ISL dataset (555 samples) and evaluated on the remaining 20% (139 samples). This last experiment, conducted without any pre-trained initialization, aimed to evaluate the model’s performance and learning capability when trained directly on a small, complex dataset.

For video-based evaluation, we used 3200 videos of the LSA64 dataset with the configuration detailed in Table 6. The dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing, with 16 frames uniformly sampled from each video to capture temporal dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency.

Table 6.

Experimental Setup for LSA64 Video Dataset.

4.3. Experiments on Image Datasets

This subsection presents the experimental evaluation of the proposed TMS feature extractor and its integration with different machine learning classifiers on image datasets. The experiments were designed to assess classifier performance, analyze prediction errors, and evaluate cross-dataset generalization.

Table 7 summarizes the classification performance in terms of Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy for both experiments. Overall, KNN achieved the best trade-off between accuracy and model compactness, reaching 99.6% and 97.8% accuracy in Exp #1 and Exp #2, respectively, with a compact model size. This makes it particularly suitable for resource-constrained deployments.

Table 8 shows the hyperparameter selection for the classifiers used in this study. The optimal configuration was obtained with k = 3, distance-based weighting, and the Euclidean metric. The cross-validation results are summarized in Table 9, which includes the mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals for each metric as well. The results confirm that the model’s performance remains consistently high across all folds, demonstrating strong generalisation.

For Experiment #1, the KNN classifier achieved a mean accuracy of , with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of [99.48, 99.62]. For Experiment #2, #3 and #4, the mean accuracy was , with a 95% CI of [96.46, 98.25]. For Experiment #5, the KNN classifier achieved a mean accuracy of , with a 95% CI of [100, 100]. For experiment #6, the mean accuracy was , with a 95% CI of [98.85, 99.38].

4.3.1. Classifier Comparison and Selection

The performance of several machine learning classifiers was first evaluated combined with the TMS feature extractor in Exp #1 and Exp #2. The two experiments yielded consistent results, confirming the robustness of the extracted features and the stability of the models across different data distributions.

Table 7.

Classifier Performance Comparison in Exp #1 and Exp #2 (%) with Model Size.

Table 7.

Classifier Performance Comparison in Exp #1 and Exp #2 (%) with Model Size.

| Classifier | Exp #1 | Exp #2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | A (%) | Model Size | P% | R% | F1% | A% | Model Size | |

| SVM | 99.5 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 99.5 | 115.2 MB | 96.4 | 96.0 | 97.0 | 96.5 | 16.9 MB |

| Random Forest | 98.1 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 36.1 MB | 94.7 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 94.4 | 15.2 MB |

| Logistic Regression | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 4.5 MB | 95.8 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 3.4 MB |

| Decision Tree | 63.1 | 63.2 | 63.1 | 63.1 | 6.5 MB | 61.8 | 60.4 | 60.0 | 60.4 | 3.9 MB |

| Naïve Bayes | 62.8 | 66.1 | 62.8 | 62.8 | 9 MB | 84.5 | 82.7 | 83.0 | 82.7 | 4.9 MB |

| MLP | 98.3 | 98.3 | 98.3 | 98.3 | 115.7 MB | 97.1 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 57.4 MB |

| KNN | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 5 MB | 97.8 | 97.7 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 3.1 MB |

Table 8.

Hyperparameters for Classifiers.

Table 8.

Hyperparameters for Classifiers.

| Classifier | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | C: [0.01, 0.1, 1, 10], Solver: [lbfgs, liblinear] |

| SVM | C: [0.1, 1, 10], Kernel: [linear, rbf], Gamma: [scale, auto] |

| Random Forest | n_estimators: [100, 200, 300], max_depth: [10, 20, None], min_samples_split: [2, 5, 10] |

| KNN | n_neighbors: [1,3, 5, 7, 9], Weights: [uniform, distance], Metric: [euclidean, manhattan] |

| Decision Tree | max_depth: [10, 20, None], min_samples_split: [2, 5, 10], Criterion: [gini, entropy] |

| Naive Bayes | var_smoothing: [1 , 1 , 1 ] |

| MLP | Activation: [relu, tanh], alpha: [0.0001, 0.001], learning_rate_init: [0.001, 0.01] |

Table 9.

5-Fold Cross-Validation Results for KNN.

Table 9.

5-Fold Cross-Validation Results for KNN.

| Fold No. | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | A (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | A (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp #1 | Exp #2, #3, #4 | |||||||

| 1 | 99.49 | 99.49 | 99.49 | 99.49 | 97.07 | 96.77 | 96.78 | 96.77 |

| 2 | 99.53 | 99.53 | 99.53 | 99.53 | 96.79 | 96.53 | 96.50 | 96.53 |

| 3 | 99.65 | 99.65 | 99.65 | 99.65 | 97.98 | 97.76 | 97.76 | 97.76 |

| 4 | 99.52 | 99.52 | 99.52 | 99.52 | 98.64 | 98.51 | 98.50 | 98.51 |

| 5 | 99.56 | 99.56 | 99.56 | 99.56 | 97.53 | 97.26 | 97.29 | 97.26 |

| Mean ± Std | 99.55 ± 0.05 | 99.55 ± 0.05 | 99.55 ± 0.05 | 99.55 ± 0.05 | 97.60 ± 0.66 | 97.37 ± 0.71 | 97.37 ± 0.71 | 97.37 ± 0.71 |

| CI | [99.48, 99.62] | [99.48, 99.62] | [99.48, 99.62] | [99.48, 99.62] | [96.78, 98.42] | [96.46, 98.25] | [96.46, 98.25] | [96.46, 98.25] |

| Exp #5 | Exp #6 | |||||||

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 99.21 | 99.26 | 99.23 | 98.91 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 99.18 | 99.23 | 99.20 | 99.23 |

| 3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 98.87 | 98.93 | 98.90 | 98.93 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 99.43 | 99.38 | 99.40 | 99.38 |

| 5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 98.91 | 98.85 | 98.88 | 98.85 |

| Mean ± Std | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 99.12 ± 0.22 | 99.13 ± 0.21 | 99.13 ± 0.21 | 99.13 ± 0.21 |

| CI | [100, 100] | [100, 100] | [100, 100] | [100, 100] | [98.87, 99.43] | [98.85, 99.38] | [98.85, 99.38] | [98.85, 99.38] |

Among the other classifiers, SVM and RF exhibited strong performance (above 90% accuracy) but required substantially larger models (over 100 MB). Logistic Regression maintained good predictive ability (around 95%) with minimal memory requirements, while Decision Tree and Naïve Bayes showed lower overall performance and higher sensitivity to data variability.

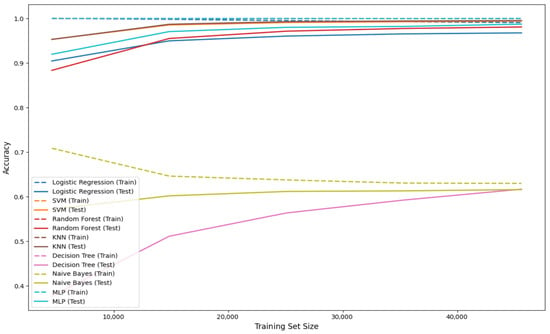

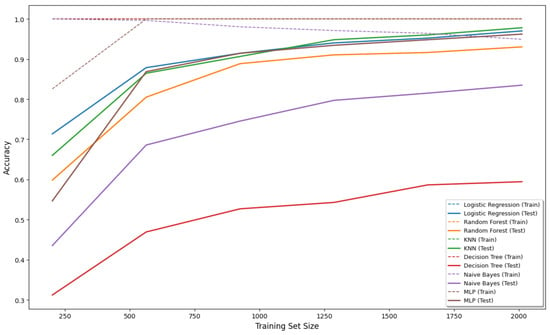

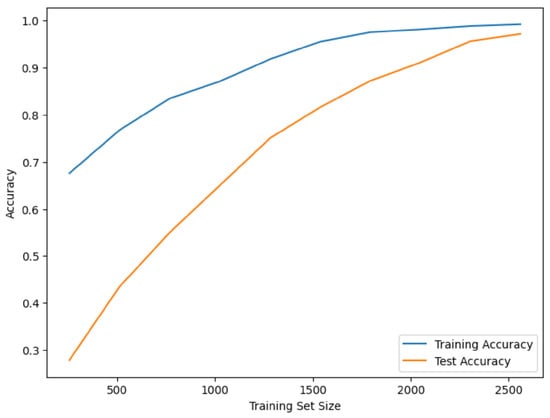

Figure 8 and Figure 9 depict the learning curves of the classifiers. In Exp #1 the classifiers were trained on a range of data from (0 to 57,005) data from the AUSL dataset, while in Exp #2 the classifier was trained on a range from 0 to 2012 that is ASLM. In both cases, accuracy improves consistently as the training set size increases, reflecting effective learning behavior and confirming the generalization capability of the models.

Figure 8.

Learning curves for multiple classifiers in Exp #1.

Figure 9.

Learning curves for multiple classifiers in Exp #2.

Based on these results, the KNN classifier was selected as the reference model for subsequent experiments, as it combines high accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency. From this point onward, we will refer to TMSK as the integration of the TMS feature extractor with the KNN classifier.

4.3.2. Cross-Dataset Performance Analysis

The proposed TMSK framework was evaluated across multiple datasets to assess its generalization capability. Table 10 summarizes the comprehensive results, demonstrating consistently high performance across different sign languages and modalities.

Table 10.

Cross-Dataset Performance of TMSK Framework.

In Exp #1, the AUSL-trained model achieved excellent results with a precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy of 99.6% on AUSL datasets that contains alphanumeric signs. When fine-tuned on the ASLM dataset (Exp #2), the AUSL+ASL-trained model maintained excellent results with slightly lower yet still remarkable scores of 97.8% across all metrics. The model continued to perform robustly in Exp #3 and #4, achieving high scores across various alphabetic datasets. Notably, Exp #5 where we test the special signs recognition achieved perfect scores, demonstrating the model’s robustness and adaptability. The perfect accuracy on special signs is due to the distinctiveness of these gestures, which are visually completely different from other signs in the dataset.

Exp #6 is conducted training and testing on the ISL dataset, consisting of sign language gesture images captured in complex and dynamic background environments. Due to the high variability in lighting conditions and background clutter, the preprocessing pipeline for this dataset was slightly more elaborate compared to previous experiments.

Each image was normalized and resized to ensure compatibility with the model architecture and to enhance generalization. Despite the inherent challenges of the ISL dataset, the model achieved high accuracy across all metrics, further confirming its robustness. Comparing these results with Exp #4, which used a different model, reveals a significant improvement in accuracy, from 91.7% in Exp #4 to 99.3% in Exp #6, when the model was trained and tested on the same data distribution.

4.3.3. Error Analysis and Discussion

Table 11 shows the misclassifications across experiments, with errors of 1% or more highlighted. In Exp #1, errors primarily occurred between visually similar signs, such as 6 → 7 (1.3%), C → D (1.5%), and Z → 8 (1.0%). Exp #2 exhibited similar confusion, notably between I → L (2.3%) and M → N (1.5%). In Exp #3, misclassifications like Y → I (1.3%), S → U (3.3%), and E → I (2.3%). Exp #4 recorded errors like A → 0 (1.3%), E → C (2.4%), N → E (1.2%), and X → D (3.5%). While our current model does not include architectural modifications specifically targeting visually similar sign pairs (such as M → N), this remains a challenging issue, especially for signs with similar hand shapes. Despite this, the overall error rate remains low, indicating that the model is performing well in most cases.

Table 11.

Misclassifications from different experiments.

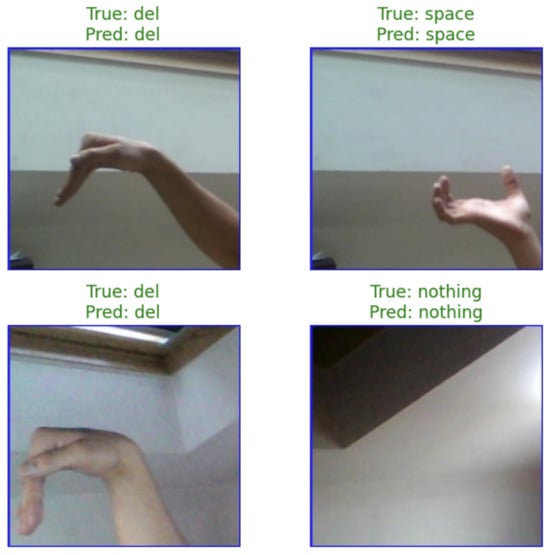

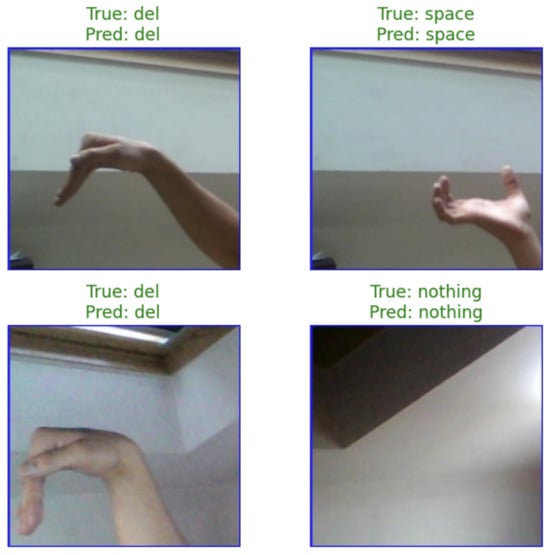

Figure 10 shows examples of accurate (green) and misclassified (red) predictions from Exp #1 and #2. The accurate predictions demonstrate reliable recognition of various signs, while the misclassified samples reflect challenges caused by subtle variations in hand shape and orientation. Figure 11 shows examples of accurate (green) and misclassified (red) predictions from the ASLF dataset (a) and ISL dataset (b): the misclassified cases highlight challenges arising from visually similar hand gestures or complex sign variations across different signing contexts. In contrast, since all special signs were correctly classified in Exp #5, Figure 12 shows only accurate predictions.

Figure 10.

Accurate and misclassified predictions on AUSL and ASLM.

4.4. Performance Analysis on Video Dataset

The proposed framework was validated on the LSA64 video dataset to demonstrate its capability in processing dynamic sign language gestures and capturing temporal dependencies. This evaluation confirms the model’s applicability beyond static image recognition to real-world continuous signing scenarios where motion dynamics are essential.

Figure 13 illustrates the learning behavior of the classfier, where the test accuracy progressively rises and converges toward the training accuracy as the dataset size increases. This consistency demonstrates that the model generalizes well with more data, while the initially high training accuracy highlights KNN’s tendency to closely fit limited training samples.

As detailed in Table 12, the model achieved outstanding performance with 99.1% accurate predictions. The high accuracy on video data demonstrates the framework’s effectiveness in processing temporal sequences and capturing gesture dynamics. A closer inspection of sign-level errors reveals that only a small subset of signs were misclassified, each one with an error rate of 10%.

Figure 11.

Accurate and misclassified predictions on ASLF and ISL.

Figure 12.

Accurate predictions of special signs.

Table 12.

Performance on the LSA64 dataset.

Overall, the results underscore the robustness of the proposed TMSK framework in effectively handling real-world, video-based sign language inputs.

Figure 13.

Performance on LSA64 Video Dataset.

5. Discussion

This study proposed the Tailored MobileNet Self-Attention KNN (TMSK) framework as a solution to the dual challenge of achieving high recognition accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency for resource-constrained deployment.

The experimental results presented in Section 4 validate our initial hypothesis that combining local spatial feature extraction with global contextual modeling can outperform conventional deep learning approaches. The hybrid design of TMSK leverages MobileNet to efficiently extract fine-grained spatial features through depthwise separable convolutions, while the Self-Attention module captures long-range dependencies and emphasizes semantically important hand regions. This synergy allows the framework to generalize effectively across multiple datasets and handle both static gestures and dynamic signing sequences. Notably, the model achieved 99.1% accuracy on the LSA64 video dataset, demonstrating its ability to capture temporal dynamics essential for continuous sign recognition. In addition to its high performance, the compact model size marks a practical advancement, making the framework suitable for deployment on mobile and embedded platforms. This efficiency supports the development of accessible communication tools for deaf and hard-of-hearing communities, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Furthermore, the experimental results indicate that the TMSK framework possesses strong potential for practical applicability. Its efficiency and robust performance suggest suitability for future integration into assistive technologies, educational applications, and gesture-based human–computer interfaces. In particular, the model’s low computational cost demonstrates the feasibility of on-device processing, which could enable responsive and efficient sign language recognition in real-world environments.

5.1. State of the Art Comparison

When compared with established architectures on similar datasets (Table 13), TMSK consistently outperforms previous methods. This improvement is largely due to its hybrid design: MobileNet efficiently captures local spatial features, while the self-attention mechanism models long-range dependencies between hand regions, something conventional approaches struggle to achieve.

Table 13.

Performance Comparison with Standard Pre-trained Baseline Models and Existing Studies.

5.2. Computational Performance and Practical Deployment Analysis

Table 14 presents a comparative analysis of the proposed TMSK model against modern state-of-the-art architectures. The TMSK model attains 99.6% and 99.1% in precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy, while maintaining a compact model size on AUSL and LSA64 datasets. Despite being lightweight, TMSK shows excellent computational efficiency, outperforming both MobileOne and YOLOv8. MobileOne was slightly more accurate on AUSL, but it required a much larger model size, while YOLOv8 achieved higher FPS but had lower accuracy compared to TMSK. These results emphasize TMSK’s strong balance between accuracy, model compactness, and real-time inference capability.

Table 14.

Performance comparison with modern SOTA architectures.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

While TMSK demonstrates strong performance across multiple datasets, several limitations of the evaluated datasets may affect the generalizability of our findings:

Limited Vocabulary Coverage: The evaluated image-based datasets focus mainly on alphabetic and numeric signs, covering only a small fraction of complete sign language vocabularies (AUSL: 36 classes; ASL_M: 36; ASL_F: 29; ISL: 23). Real-world communication involves thousands of lexical signs and grammatical constructions not represented here.

Static vs. Dynamic Signing: All image-based datasets contain static hand postures, insufficient to capture the dynamic nature of natural sign language. While LSA64 includes video sequences, it still consists of isolated signs rather than continuous conversational signing, missing smooth transitions and temporal dependencies.

Limited Sample Diversity and Size: Small dataset sizes (e.g., ISL: 694 samples; ASL_M: 70 per class) may limit statistical reliability and increase overfitting risk. Additionally, signer diversity in terms of age, gender, hand size, skin tone, and regional variations is limited.

Controlled Recording Conditions: Most datasets were recorded under controlled laboratory settings with uniform lighting, plain backgrounds, and standardized camera angles, which do not reflect real-world challenges such as varying illumination, occlusions, cluttered backgrounds, or non-frontal viewpoints.

Absence of Non-Manual Components: Facial expressions, head movements, and body posture, which convey critical grammatical and semantic information, are largely missing. TMSK focuses on hand shape and motion, potentially missing up to 50% of linguistic information.

5.4. Future Work

For future work, we plan to extend TMSK towards real-world sign language recognition by leveraging datasets with continuous signing, incorporating non-manual components, increasing diversity in recording conditions and signer demographics, expanding sample sizes to capture natural variation, and designing evaluation protocols that assess generalization to completely unseen signers and environments. We plan to conduct an ablation study to isolate and evaluate the impact of each component of our proposed methodology. Additionally, hardware optimization strategies such as model quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation will be explored to further reduce computational requirements, enabling deployment on highly constrained devices such as smartwatches or AR glasses.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces the TMSK framework, a hybrid model for sign language recognition (SLR) that effectively combines Tailored MobileNet, Self-Attention, and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). The primary aim of this work was to address a key gap in existing SLR systems by achieving high recognition accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for resource-constrained platforms.

The proposed approach demonstrates impressive accuracy and generalization capabilities across multiple benchmark datasets, including AUSL, ASL, ISL, and LSA64. Through systematic optimization and cross-validation, the TMSK framework achieved 99.6% accuracy on image-based datasets and 99.1% accuracy on the LSA64 video dataset, with a compact model size. These results confirm that the model effectively balances performance and efficiency, making it a strong candidate for further development towards real-time applications. By leveraging its lightweight design, the proposed framework outperforms several baseline architectures in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. This work contributes to the advancement of efficient and portable SLR systems, providing a foundation for future research into practical applications in assistive communication and human–computer interaction.

Future work will focus on validating this framework in fully unconstrained, real-world environments to bridge the gap between laboratory performance and practical deployment.

Author Contributions

All authors I.Q., L.P., F.R. and W.N. contributed to the conception, design, implementation, and analysis of the study. The first author I.Q., conducted experiments and drafted the first version of the manuscript, while the co-authors L.P., F.R. and W.N. provided technical guidance, validation, and manuscript revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The code is available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/IRFAN-QUTAB/Mobile-Net-Based-Sign-Language-Recognition- (accessed on 13 November 2025). Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The links are provided in the dataset section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AUSL | Australian Sign Language |

| ASLM | American Sign Language (Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology) |

| ASLF | American Sign Language Fingerspelling |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| ISL | Indian Sign Language |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbor |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| LSA64 | Argentinian Sign Language (64-Signs) |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SLR | Sign Language Recognition |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TMS | Tailored MobileNet Self-Attention |

| TMSK | Tailored MobileNet Self-Attention and KNN as classifier |

References

- Green, J.; Hodge, G.; Kelly, B. Two decades of sign language and gesture research in Australia: 2000–2020. Lang. Doc. Conserv. 2022, 16, 32–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, M.D.; Bernardi, M.; Kleppe, S.; Walz, K. Hearing Loss: Genetic Testing. Genes 2024, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Shin, J.; Al Mehedi Hasan, M.; Rahim, M.A.; Okuyama, Y. Rotation, Translation and Scale Invariant Sign Word Recognition Using Deep Learning. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 44, 2521–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Shin, J.; Okuyama, Y.; Tomioka, Y. Multistage spatial attention-based neural network for hand gesture recognition. Computers 2023, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Hirooka, K.; Suzuki, K.; Lee, H.S.; Jang, S.W. Korean sign language recognition using transformer-based deep neural network. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Jang, S.W.; Lee, H.S.; Shin, J. Multi-stream general and graph-based deep neural networks for skeleton-based sign language recognition. Electronics 2023, 12, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencherif, M.A.; Algabri, M.; Mekhtiche, M.A.; Faisal, M.; Alsulaiman, M.; Mathkour, H.; Al-Hammadi, M.; Ghaleb, H. Arabic sign language recognition system using 2D hands and body skeleton data. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59612–59627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadami, A.; Taheri, A.; Meghdari, A. A Transformer-Based Multi-Stream Approach for Isolated Iranian Sign Language Recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.09544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmalaki, A.; Ghaderzadeh, A.; Maihami, V. Recognition of Persian Sign Language Alphabet Using Gaussian Distribution, Radial Distance and Centroid-Radii. Recent Adv. Comput. Sci. Commun. Former. Recent Patents Comput. Sci. 2021, 14, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Potamianos, G.; Sapountzaki, G.; Goulas, T.; Efthimiou, E.; Fotinea, S.E.; Maragos, P. Greek sign language recognition for an education platform. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 24, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, Y.; Claudio, K.S.; Budiman, V.M.; Achmad, S.; Kurniawan, A. Sign language recognition system for communicating to people with disabilities. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 216, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.A.; Miah, A.S.M.; Sayeed, A.; Shin, J. Hand gesture recognition based on optimal segmentation in human-computer interaction. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd IEEE International Conference on Knowledge Innovation and Invention (ICKII), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 21–23 August 2020; pp. 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wali, A.; Shariq, R.; Shoaib, S.; Amir, S.; Farhan, A.A. Recent progress in sign language recognition: A review. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2023, 34, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihan Camgoz, N.; Hadfield, S.; Koller, O.; Bowden, R. Subunets: End-to-end hand shape and continuous sign language recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 3056–3065. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Tai, Y.W. Fully convolutional networks for continuous sign language recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 697–714. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qurishi, M.; Khalid, T.; Souissi, R. Deep learning for sign language recognition: Current techniques, benchmarks, and open issues. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 126917–126951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, H. Iterative alignment network for continuous sign language recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 4165–4174. [Google Scholar]

- Rajalakshmi, E.; Elakkiya, R.; Subramaniyaswamy, V.; Alexey, L.P.; Mikhail, G.; Bakaev, M.; Kotecha, K.; Gabralla, L.A.; Abraham, A. Multi-semantic discriminative feature learning for sign gesture recognition using hybrid deep neural architecture. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalakshmi, E.; Elakkiya, R.; Prikhodko, A.L.; Grif, M.G.; Bakaev, M.A.; Saini, J.R.; Kotecha, K.; Subramaniyaswamy, V. Static and dynamic isolated Indian and Russian sign language recognition with spatial and temporal feature detection using hybrid neural network. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2022, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangsuksant, W.; Adhan, S.; Pintavirooj, C. American Sign Language recognition by using 3D geometric invariant feature and ANN classification. In Proceedings of the The 7th 2014 Biomedical Engineering International Conference, Fukuoka, Japan, 26–28 November 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ragab, A.; Ahmed, M.; Chau, S.C. Sign language recognition using Hilbert curve features. In Image Analysis and Recognition, Proceedings of the 10th International Conference, ICIAR, Aveiro, Portugal, 26–28 June 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, A.S.M.; Hasan, M.A.M.; Shin, J. Dynamic hand gesture recognition using multi-branch attention based graph and general deep learning model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 4703–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, B.; Rajalakshmi, E.; Elakkiya, R.; Kotecha, K.; Abraham, A.; Gabralla, L.A.; Subramaniyaswamy, V. Development of an end-to-end deep learning framework for sign language recognition, translation, and video generation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 104358–104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabwan, B.A.; Gazzan, M.; Ismil, O.A.; Farah, E.A.; Almula, S.M.; Ali, Y.A. Hand Gesture Classification for the Deaf and Mute Using the DenseNet169 Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 16–18 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 933–937. [Google Scholar]

- Urmee, P.P.; Al Mashud, M.A.; Akter, J.; Jameel, A.S.M.M.; Islam, S. Real-time bangla sign language detection using xception model with augmented dataset. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International WIE Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (WIECON-ECE), Bangalore, India, 15–16 November 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Morillas-Espejo, F.; Martinez-Martin, E. A real-time platform for Spanish Sign Language interpretation. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 2675–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xue, W.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, T.; Chen, S. TB-Net: Intra-and inter-video correlation learning for continuous sign language recognition. Inf. Fusion 2024, 109, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, O.; Zargaran, S.; Ney, H.; Bowden, R. Deep sign: Enabling robust statistical continuous sign language recognition via hybrid CNN-HMMs. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2018, 126, 1311–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yuan, L.; Wen, R.; Wang, Q. Sign language recognition based on concept learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 25–28 May 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, R.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C. A deep neural framework for continuous sign language recognition by iterative training. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2019, 21, 1880–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, H.; Li, W. Attention-based 3D-CNNs for large-vocabulary sign language recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2018, 29, 2822–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qambrani, S.A.; Dahri, F.A.; Bhatti, S.; Banbhrani, S.K. Auslan Sign Language Image Recognition Using Deep Neural Network. Soc. Sci. Rev. Arch. 2025, 3, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglot, D.; Kulkarni, M. Real time sign language recognition using the leap motion controller. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Coimbatore, India, 26–27 August 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, P.K.; Oyshe, K.U.; Rahaman, M.A.; Debnath, T.; Rahman, A.; Kumar, N. Computer vision-based hybrid efficient convolution for isolated dynamic sign language recognition. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 19951–19966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama Rawf, K.M.; Abdulrahman, A.O.; Mohammed, A.A. Improved recognition of Kurdish sign language using modified CNN. Computers 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khuzayem, L.; Shafi, S.; Aljahdali, S.; Alkhamesie, R.; Alzamzami, O. Efhamni: A deep learning-based Saudi sign language recognition application. Sensors 2024, 24, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D.; Anand, R.S. Isolated video-based sign language recognition using a hybrid CNN-LSTM framework based on attention mechanism. Electronics 2024, 13, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Ameer, R.; Ahmed, M.; Al-Qaysi, Z.; Salih, M.; Shuwandy, M.L. Empowering communication: A deep learning framework for Arabic sign language recognition with an attention mechanism. Computers 2024, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Lahiri, R.; Konar, A.; Nagar, A.K. A novel approach to american sign language recognition using madaline neural network. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Athens, Greece, 6–9 December 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, U.; Devarajan, D.; Kumar, P.S.; Rajkumar, K.; Meena, M.; Akilan, T. Recognition of American sign language using modified deep residual CNN with modified canny edge segmentation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 38093–38120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhar, P.; Bhagat, N.K.; G N, R. Deep learning methods for indian sign language recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 10th International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE-Berlin), Berlin, Germany, 9–11 November 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adaloglou, N.; Chatzis, T.; Papastratis, I.; Stergioulas, A.; Papadopoulos, G.T.; Zacharopoulou, V.; Xydopoulos, G.J.; Atzakas, K.; Papazachariou, D.; Daras, P. A comprehensive study on deep learning-based methods for sign language recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 24, 1750–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureed, M.; Atif, M.; Abbasi, F.A. Character Recognition of Auslan Sign Language using Neural Network. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Math. Sci. 2023, 2, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Rodriguez, C.; Yu, X.; Li, H. Word-level deep sign language recognition from video: A new large-scale dataset and methods comparison. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Snowmass Village, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 1459–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Baihan, A.; Alutaibi, A.I.; Alshehri, M.; Sharma, S.K. Sign language recognition using modified deep learning network and hybrid optimization: A hybrid optimizer (HO) based optimized CNNSa-LSTM approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanni, K.F.; Islam, S.; Sultana, Z.; Alam, T.; Mahmood, M. DeepBdSL: A Comprehensive Assessment of Deep Learning Architectures for Multiclass Bengali Sign Language Gesture Recognition. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 20–22 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 2219–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Kvanchiani, K.; Kraynov, R.; Petrova, E.; Surovcev, P.; Nagaev, A.; Kapitanov, A. Training strategies for isolated sign language recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, G.M.R.; Junior, G.B.; de Almeida, J.D.S.; de Paiva, A.C. Sign Language Recognition Based on 3D Convolutional Neural Networks. In Image Analysis and Recognition; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); LNIP; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10882, pp. 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Incel, O.D.; Bursa, S.Ö. On-device deep learning for mobile and wearable sensing applications: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 5501–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network in network. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.4400. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sarhan, N.; Lauri, M.; Frintrop, S. Multi-phase fine-tuning: A new fine-tuning approach for sign language recognition. KI-Künstliche Intell. 2022, 36, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajbakhsh, N.; Shin, J.Y.; Gurudu, S.R.; Hurst, R.T.; Kendall, C.B.; Gotway, M.B.; Liang, J. Convolutional neural networks for medical image analysis: Full training or fine tuning? IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2016, 35, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosinski, J.; Clune, J.; Bengio, Y.; Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 3320–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Mishra, R. Enhancing Sign Language Recognition: Leveraging EfficientNet-B0 with Transformer-based Decoding. Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Scope (IRJMS) 2024, 5, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).