Abstract

Vehicle–road–cloud collaborative perception improves perception performance via multi-agent information sharing and data fusion, but it faces coupled trade-offs among perception accuracy, computing resources, and communication bandwidth. Optimizing agents’ intelligence or underlaying resources alone fails to resolve this conflict, limiting collaboration efficiency. We propose C4I-JO, a joint resource and intelligence optimization method for vehicle–road–cloud collaborative perception. We employ slimmable networks to achieve intelligent elasticity. Based on these, C4I-JO jointly optimizes four key dimensions to minimize resource consumption while meeting accuracy and latency constraints, including collaborative mechanisms to cut redundant communication, resource allocation to avoid supply–demand bottlenecks, intelligent elasticity to balance accuracy and resources, and computation offloading to reduce local burden. We propose a two-layer iterative decoupling algorithm that addresses the optimization problem. Specifically, the outer level leverages Second-Order Cone Programming (SOCP) and the interior-point method, while the inner level utilizes a Genetic Algorithm (GA). Simulations show that C4I-JO outperforms baselines in both resource efficiency and perception quality.

1. Introduction

Vehicle–road–cloud collaborative perception is a key enabler of autonomous driving in complex traffic scenarios, as it significantly improves environmental perception by leveraging multi-agent information sharing and fusion [1,2,3]. While collaboration overcomes the limitations of single-vehicle sensors, such as occlusions and limited field of view, it simultaneously imposes coupled and stringent demands on system resources, specifically requiring high-performance computing power and substantial, low-latency communication bandwidth.

Existing research predominantly addresses these demands in isolation. Most works focus on optimizing communication protocols to reduce bandwidth usage [4,5] or managing edge computing resource allocation for fixed tasks [6]. However, a critical gap persists: Current methods often assume a static AI model structure. They lack “intelligent elasticity”—the ability to dynamically adjust the neural network’s complexity in response to real-time channel fluctuations and processing loads. Optimizing the underlying infrastructure without enabling the application layer to adapt restricts overall system efficiency and performance under dynamic V2X conditions.

To address this fundamental limitation, we introduce a joint resource and intelligence optimization method for vehicle–road–cloud collaborative perception, named, C4I-JO. This method achieves joint optimization through multiple dimensions: collaborative mechanism, communication resource allocation, computing resource allocation, computation offloading, and intelligent elasticity. We construct an adaptive computing framework where a slimmable network [7] is employed to achieve intelligent elasticity to meet the demands of perception computing. Meanwhile, we employ an accuracy-aware coordination method to minimize system resource consumption under the premise of satisfying accuracy and delay constraints.

In conclusion, we present the following contributions:

- We use a slimmable network to construct an adaptive computing framework, which enables intelligent elasticity, thereby meeting the computational demands of perception tasks.

- We propose an accuracy-aware collaborative mechanism. By leveraging deep supervised learning, a nonlinear mapping is established between perception accuracy, network structure, and data density.

- We integrate MEC technology and utilize computation offloading technology to achieve the flexible offloading of computing tasks, thereby improving the overall computing efficiency.

- We design and solve a multi-objective optimization problem that comprehensively considers a collaborative mechanism, resource allocation, intelligent elasticity, and computation offloading, aiming to minimize overall resource consumption while satisfying accuracy and delay constraints. Unlike traditional V2X approaches that treat the AI model as a static black box and only optimize transmission resources, our method uniquely introduces “intelligent elasticity.” By jointly optimizing the collaborative mechanism, resource allocation, and the internal structure of the slimmable network, we achieve a superior Pareto frontier between perception accuracy and latency, adapting to dynamic constraints that fixed-model approaches cannot handle.

2. Related Work

2.1. Collaborative Perception

As a core application scenario of multi-agent systems in the perception module of autonomous driving, collaborative perception effectively addresses the problems of sensor occlusion and limited perception ranges existing in traditional single-agent perception through the information sharing mechanism between CAVs and infrastructure, and it has become a research focus in the realm of intelligent transportation systems (ITSs). Based on the different stages of information fusion, existing collaborative perception frameworks can be systematically divided into three categories: early fusion, intermediate fusion, and late fusion. Early fusion emphasizes the sharing of raw data, late fusion concentrates on decision-level integration, while intermediate fusion achieves the improvement of perception capabilities through feature-level interaction. Among them, the intermediate collaboration mechanism has become a mainstream research direction due to its advantage in balancing performance and computational efficiency, and it has shown significant potential for technological breakthroughs in recent years. Within the methodological system of intermediate collaboration, V2VNet [4] takes the lead in introducing a spatial-aware graph neural network (GNN) and constructs a topological modeling framework for inter-agent communication. Although this method improves collaborative performance through GNN, the scalar collaborative weight mechanism it adopts is difficult to accurately characterize the heterogeneous attention in the spatial domain. To address this limitation, DiscoNet [5] innovatively proposes a matrix-valued edge weight modeling scheme, which captures fine-grained dependencies in inter-agent interactions through high-resolution attention maps, and combines a teacher–student knowledge distillation framework to achieve the collaborative optimization of early–intermediate fusion, further advancing the performance boundary. AttFusion [8] adopts an encoder architecture, realizing feature compression and semantic preservation through multi-level 2D convolution and max-pooling operations. In terms of the communication mechanism’s design, Who2com [9] establishes the first communication protocol under bandwidth constraints, enabling efficient information interaction through a three-stage handshaking process. Its follow-up work, When2com [10], introduces a scaled universal attention mechanism and constructs a dynamic communication method based on information completeness evaluation, allowing agents to initiate collaboration only when perception is insufficient, thus significantly reducing resource consumption. Where2com [11] further proposes a spatial confidence-aware communication mechanism, which determines key perception regions by generating a spatial confidence map, realizing the collaborative optimization of feature selection and communication objectives and greatly saving bandwidth resources while ensuring perception accuracy.

Based on the category of participating agents, collaborative perception can be classified into vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) collaboration, vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) collaboration, and vehicle-to-everything (V2X) collaboration, which involves more types of agents. Compared with V2V collaboration, V2I collaboration has the potential to provide more reliable collaborative information due to the stable communication capability and global observation perspective of infrastructure; however, related research is still in its initial stage. V2X-ViT [12] first achieves the unified modeling of V2V and V2I. It learns the interaction relationships between different types of agents through a heterogeneous multi-agent self-attention model and combines a multi-scale window self-attention mechanism to capture long-range spatial dependencies in high-resolution scenarios. VIMI (Vehicle-Infrastructure Multi-View Intermediate Fusion) [13] focuses on camera-based collaborative perception. It realizes cross-scale correlations between vehicle and infrastructure features via a multi-scale cross-attention module, where a deformable convolutional network is used for multi-scale feature extraction, and cross-attention operations generate attention weights for each scale.

While these mechanisms effectively filter irrelevant data to save bandwidth, they all rely on fixed-structure perception models. Our approach introduces the dimension of intelligent elasticity by dynamically adjusting the perception model’s complexity.

2.2. Resource Allocation

The core technology evolution of V2X resource allocation revolves around two main threads: dynamic scheduling of communication resources and efficient utilization of computing resources. Existing studies have achieved phased breakthroughs in addressing challenges such as high mobility and heterogeneous demands, yet key gaps remain in scenario adaptation and collaborative optimization.

In terms of communication resource allocation, Xu et al. [14] propose a PPO algorithm-driven joint power–bandwidth allocation scheme. Through the collaborative scheduling of discrete and continuous resources, this scheme achieves a balance between system capacity and delay constraints in dynamic scenarios for the first time; Jiang et al. [15] integrate NOMA technology with deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to construct an energy efficiency optimization model. This model addresses the issue of low resource utilization in traditional NOMA technology, improving system energy efficiency by more than 30%. However, these studies do not fully consider the interference coupling relationship under complex topologies. Liu et al. [16] introduce digital twin technology to build a virtual mapping space and optimize the linked configuration of communication-caching resources through edge node collaboration, reducing transmission delay by 25%. Nevertheless, the load balancing problem in high-density scenarios remains unsolved. Liu et al. [17] combine integrated sensing and communications technology to design a DRL-driven joint channel–power–bandwidth allocation method, which achieves a 15–20% improvement in spectral efficiency in spectrum-scarce scenarios. Ji et al. [18] innovatively integrate GNN with DRL, modeling the interference relationship of V2X links through dynamic graphs. This approach increases the V2V transmission success rate, but slot collision issues still exist in extreme scenarios such as complex urban intersections.

In terms of computing resource allocation, edge computing-based collaborative perception resource allocation with roadside units (RSUs) as core nodes is a key research direction for balancing the real-time performance, accuracy, and resource efficiency of autonomous driving systems. Moreno et al. [19] propose a collaborative ITS architecture based on distributed RSUs, which enables efficient communication between vehicles and infrastructure through collaboration among RSUs. To address the multi-task resource competition problem faced by RSUs, Zobaed et al. [20] propose the “Edge-multi AI” framework, which ensures the efficient execution of multiple artificial intelligence models on edge nodes through the dynamic allocation of resources and the scheduling of tasks. Gu et al. [21] combine federated self-supervised learning with DRL to design a task offloading and resource allocation method for vehicle edge computing. Ye et al. [6] study an “accuracy-aware” collaborative perception and computing framework for CAVs. By sharing sensor data and computing resources among vehicles, this framework balances perception accuracy and computing overhead, ensuring reliable decision-making in complex traffic environments.

However, these resource allocation strategies are typically decoupled from the deep learning model’s internal computational complexity. Our C4I-JO method bridges this gap by making the resource allocation decision directly dependent on the dynamically chosen network width ().

2.3. Slimmable Network

As a dynamic resource adaptation framework, slimmable network achieves a refined trade-off between performance and computational efficiency through adaptively adjusting the network width. Its core value lies in replacing the traditional independent training paradigm of multiple models with a single shared-weight model, which reduces the training and deployment costs in multi-resource scenarios. To address the inefficiency of independent model training required in traditional multi-resource scenarios, Yu et al. [7] propose the core framework of slimmable networks, enabling multi-width shared training of a single network through switchable batch normalization. To expand the generality of the basic architecture, Yu et al. [22] propose a universal slimmable network (US-Net), which supports arbitrary width configurations and is compatible with networks without batch normalization. They innovatively design a sandwich rule and an in situ distillation method to solve the performance fluctuation problem in multi-width training. To tackle the issue that static width cannot adapt to the dynamic characteristics of inputs, Li et al. [23] propose a dynamic slimmable network (DS-Net), realizing real-time input-based width adjustment through a double-headed dynamic gate and verifying the efficiency advantages in dynamic scenarios. Wang et al. [24] address the high training cost of multi-resource adaptation in self-supervised learning by proposing DSP-Net. This model combines the slimmable concept with discriminative self-supervision and realizes the generation of multi-width subnets through a single pretraining process via in situ ensemble guidance and sandwich gate sparsification. Zhao et al. [25] tackle the problem of the poor performance of small models in contrastive self-supervision by introducing SlimCLR. It enhances the self-supervised performance of multi-width subnets through methods such as subnetwork slow start, online distillation, and loss weighting. For the memory constraints in MobileNet deployment, Bouguezzi et al. [26] propose Slim MobileNet. This model achieves a lightweight model and accuracy improvement by reducing the number of layers, replacing activation functions, and optimizing convolutional structures. Elminshawi et al. [27] integrate the slimmable mechanism into speech separation tasks, putting forward Slim-TasNet and a dynamic model. These two solutions respectively realize dynamic width adjustment based on speech features through an input utilization factor and a gating mechanism, thereby reducing computational complexity. Yu et al. [28] aim to improve the efficiency of channel pruning and propose AutoSlim. It uses slimmable networks to evaluate the performance of multi-channel configurations, iteratively prunes redundant channels based on prediction results, and converts the multi-width evaluation capability into a decision basis for automated pruning.

3. System Model

3.1. Vehicle-Road-Cloud Collaborative Perception Scenario

To improve readability and clarity, the key mathematical notations used in this paper are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key notations and definitions.

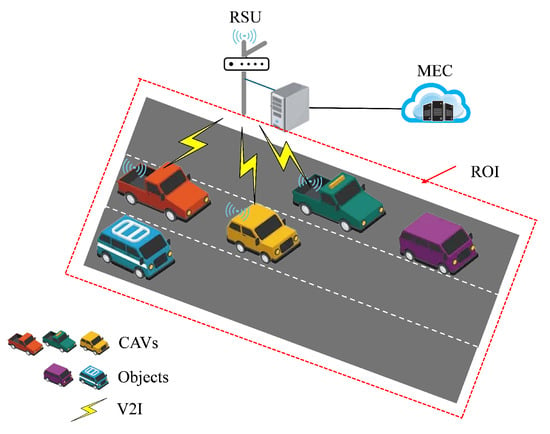

As shown in Figure 1, we investigate a vehicle–road–cloud collaborative perception scenario on urban roads. This scenario consists of Q CAVs equipped with sensors, one RSU with both sensing and computing capabilities, and one MEC unit with computing capabilities, where denotes the set of CAVs.

Figure 1.

Vehicle–road–cloud collaborative perception scenario.

CAVs and the RSU communicate via C-V2X, while the RSU and the MEC communicate through optical fibers. Specifically, the perception task is initiated by the RSU, along with Q assisting CAVs capable of collaborative perception. Let represent the set of assisting nodes, which includes all CAVs and the RSU, and denotes the index of an assisting node.

Assisting nodes perform perception tasks within a region of interest (ROI), detecting G objects. Let denote the set of objects to be perceived by assisting nodes, where represents the index of each object, and denotes the detection task of the q-th assisting node for object g. The perception tasks of assisting nodes include detecting the presence and positions of all G objects and estimating the category of each individual detected object, denoted as g.

3.2. Perception Data

Each CAV and RSU is capable of scanning its surrounding environment. For every scan, the LiDAR sensor of the q-th assisting node produces a set of 3D point clouds as raw perception data, represented by the set , where represents the 3D coordinates of the i-th point within the surroundings.

All assisting nodes share the same global coordinate system, since the local coordinate systems can be matched via a coordinate mapping. The positions of object is represented by its 3D bounding box, which is denoted as a six-dimensional vector . This vector denotes the center, length, width, and height of the 3D bounding box of object g.

For each object g, the raw perception data of the assisting node q surrounding it can be obtained from the raw LiDAR data .

3.3. Architecture

Bounding box detection refers to detecting whether there are objects within the ROI area of the RSU, and each object has a corresponding bounding box estimation. We adopt a two-stage collaborative perception method that combines late fusion and intermediate fusion. Late Coarse Fusion Stage: All CAVs and the RSU utilize a compact bounding box detection method to assess the 3D bounding box parameters of each potential object. Intermediate Fine Fusion Stage: Each assisting collaborative node then sends the detected bounding boxes together with intermediate features to the RSU for aggregation, thereby achieving more accurate bounding box detection and object classification results. The first stage is lightweight and involves very little communication and computing resources; therefore, we focus on the optimization of the second stage.

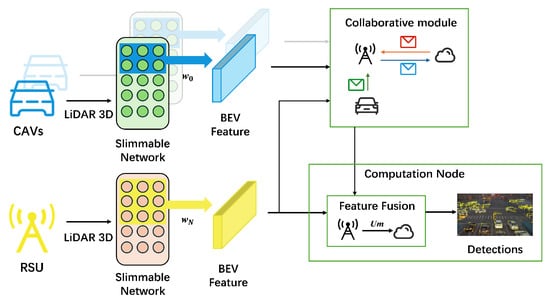

In the intermediate fine fusion stage, object detection based on shared bird’s-eye view (BEV) features usually uses an AI model to estimate the category probability of each object. The AI model requires intermediate feature transmission and fusion during the object detection process. Therefore, the entire process is divided into two sub-stages: the intermediate feature generation sub-stage and the feature fusion sub-stage, as shown in Figure 2. In the intermediate feature generation phase, the AI model leverages a slimmable network to dynamically adjust its structure based on the constraints of edge noise conditions, transforming point cloud data into intermediate features, thereby optimizing the efficiency of the model.

Figure 2.

Perception architecture.

Intuitively, the slimmable network acts as a “gearbox” for perception data transmission in V2X scenarios, allowing for real-time adaptation. For instance, in an ideal line-of-sight (LOS) condition with abundant bandwidth, the network uses a “full-width” () configuration to maximize accuracy. Conversely, in a congested intersection where bandwidth is scarce, the system instantly switches to a “slim” configuration (e.g., ). This elasticity significantly reduces the transmission data volume, preventing critical latency violations and packet loss, which is essential for maintaining safety in dynamic channel conditions.

Let represent the width ratio of a slimmable network for each assisting node in the system. Network width refers to the number of channels per layer, a key determinant of a model’s computational complexity and representational capacity. The network width ratio is the fraction of these channels that are actually engaged in computation. The RSU can perform computation offloading for detection tasks, with the offloading object being the MEC. Let U be a binary decision matrix, where indicates that the detection task for object g is offloaded to the MEC for computation. In the feature fusion sub-stage, all collaborative nodes participating in collaborative perception transmit their perceived BEV features to the RSU. If , the RSU then transmits these features to the MEC for corresponding computation.

In object detection for collaborative perception, the BEV features of potential object g generated by assisting node q are affected by the network width parameter of the feature generation network . Therefore, the BEV feature generation relationship is as follows:

where denotes the BEV features of potential object g generated by assisting node q.

Meanwhile, to measure the quality of BEV features , we propose a data quality evaluator . Specifically, we simulate the quality of the BEV features using the density of raw point cloud data and the width of the slimmable network. This design offers advantages in two key aspects. First, the density of point clouds directly reflects the granularity of perception data. A higher density provides richer spatial information, which helps capture subtle differences in spatial distribution and enhances the geometric completeness of BEV features. Second, the width of the network affects the representational capacity of AI model. Therefore, we extract object-aware sensing data from the raw point cloud data of assisting node q and combine it with the slimmable network width to construct a quality evaluation metric for . This framework not only improves the generalization ability of AI models in diverse scenarios but also provides a more precise and controllable quality prior for subsequent vehicle–road–cloud cooperation. The relationship is given as follows:

where represents the data quality of and is a real-valued quantity.

In the object detection process, for object g, up to assisting nodes can participate in collaborative perception (Q CAVs and 1 RSU). Let S denote the binary decision matrix: if and , it indicates that assisting node q can perceive object g and conduct collaborative perception with the RSU; if and , it indicates that the RSU can independently perceive object g. Therefore, the total perception data is the set of perception data from all participating assisting nodes involved in the collaboration:

Similarly, the data quality is defined as follows:

3.4. Computation Model

In the point cloud processing of object detection AI models, the overall computational demand increases with the growth of input data volume, thereby imposing higher requirements on computational resources. Let denote the available computational resources of collaborative node q and denote the available computational resources of computational node (), with the unit of Hertz (Hz). Define as the proportion of computational resources allocated by collaborative node q in the intermediate feature generation stage, and as the proportion of computational resources allocated by computational node in the feature fusion stage. Parameters and represent the complexity of the AI model in these two stages (with the unit of cycles per bit), indicating the average number of CPU cycles required to process each bit of sensory data. For each task , the computational demand at each stage is given as follows:

where denotes the size of the data. Therefore, the total computational demands of collaborative node q and computational node in their respective stages are denoted as and , respectively:

For each feature fusion task, data processing starts only after receiving the data transmitted by the auxiliary collaborative nodes. For explanation simplicity, it is assumed that the RSU (or MEC) has received all required data, after which the AI model deployed on it begins processing. The computation times of the two stages on collaborative node q and computational node are denoted as and , respectively, and their calculation methods are as follows:

Meanwhile, collaborative node q and computational node generate cumulative computing resource consumption and in their respective stages. Since the consumption of computing resources varies with time during task processing, we assume that its consumption pattern is as follows:

where represents the effective switching capacitance of the CPU on each collaborative node.

3.5. Communication Model

If assisting node q generates object-aware sensing data for object g, i.e., , but sub-task g is offloaded on the MEC, i.e., , then the object-aware sensing data should be transmitted from assisting node q to the RSU and subsequently from the RSU to the MEC. Define as the data size of a single observation point (in bits). The overall size of the perception data sent from assisting node q to the RSU (which may be used for different subtasks) is denoted as and expressed as

Orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) is used for V2X transmission. Assume that all V2I links operate on a shared spectrum with total bandwidth of , while the communication between RSU and MEC shares an optical transmission channel which is a fixed value. Let represent the continuous bandwidth distribution matrix in , where indicates the proportions of bandwidth allocation from assisting node q to the RSU for communication. Since no bandwidth needs to be allocated to the RSU, we have , and the total proportion of bandwidth allocation shall not exceed 1, which is given by

The mean transmission rate from assisting node q to the RSU is given by

where represents the transmission power of assisting node q, is the channel attenuation factor from assisting node q to the RSU, is the separation between assisting node q and the RSU, is the loss exponent, and represents the received interference power. We presume a fixed distance during the detection task and take into account the minimal delay requirement of the detection task: for example, . The mean transmission duration of all the perception data sent from assisting node q to the RSU is denoted as , which is given by

The amount of data transmitted from the RSU to the MEC is denoted as , which is

The mean transmission rate from the RSU to the MEC is denoted as R, and the transmission time of all sensing data sent from the RSU to the MEC is denoted as t:

3.6. Problem Formulation

The result of an object detection task is a multi-aspect confidence vector, where greater confidence scores indicate a greater likelihood that the detected object exists and belongs to a specific class. Therefore, the predicted confidence values are used as a measure of the model’s accuracy. We integrate the data and use the AI model to process it, estimating the perception accuracy based on the data quality , which can be evaluated using a collaborative accuracy prediction model. For small objects, fewer observation points are required for accuracy-aware, thus considering the bounding size of the objects during the accuracy calculation. The input of the model includes data quality and bounding box size, and the outcome is the accuracy:

The accuracy of any object g detected by the RSU can be predicted through the accuracy estimation learning model. We set that the observation accuracy of each object g should meet the accuracy threshold A, given by

Meanwhile, the completion time for assisting node q to finish the object detection task must also not exceed a threshold T. Since the data volume of the detection results is very small, the delay of data transmitted back from the MEC to the RSU is negligible, and we have a latency limitation as follows:

Since assisting nodes generate cumulative consumption of computing resources during the process of object detection, we set that the assisting nodes use the maximum computing resources in both task stages as their overall benchmark value, which is set as

We formulate the joint optimization problem to minimize the total weighted system cost. The objective function is conceptually defined as the sum of two coupled resource consumption instances: communication cost: determined by the sum of allocated bandwidth fractions , promoting efficient spectrum reuse; computation cost: determined by the normalized energy consumption derived from the operating frequencies and processing times of all nodes. This optimization is executed under three crucial physical and performance constraints; accuracy constraint: every detected object g must meet a minimum required confidence threshold A (Equation (20)); latency constraint: the total time required for sensing, feature transmission, and fusion must not exceed the safety-critical threshold T (Equation (21)); resource capacity constraint: total allocated bandwidth and computing cycles must not exceed the physical limits of the RSU and MEC server. Accordingly, the optimization problem is formulated as follows:

Problem P1 is subject to constraints in terms of topological structure, network structure, accuracy, latency, and resource capacity. Among these, both the topological constraints and communication resource constraints include Equation (14), while the accuracy constraint and latency constraint are, respectively, given by Equations (20) and (21). represents the importance of balancing the consumption of communication and computing resources.

4. Method

Since Problem P1 involves both discrete and continuous variables and the accuracy constraint derived from the DNN is a nonlinear constraint, it is relatively complex to solve. We observe that the accuracy constraint depends on the collaborative object selection matrix (S), the slimmable network width matrix (W), and the computation offloading matrix (U). The topological constraint depends on the collaborative object selection matrix (S), and both the latency constraint and resource constraint depend on the selection of collaborative objects, resource allocation, and changes in the slimmable network’s width.

Therefore, we propose a decomposition-based algorithm to solve Problem P1. This algorithm adopts a two-layer iterative structure. In the outer-layer module, a Genetic Algorithm (GA) is used to iteratively optimize the collaboration matrix S, network width matrix W, and computation offloading matrix U, satisfying the accuracy constraint and topological constraint, which is denoted as the tuple . Then, is passed to the inner-layer module, which only needs to find a solution to a resource allocation sub-problem to obtain the that meets the latency and resource constraints, as well as the total resource consumption cost. Finally, the Genetic Algorithm continues to generate the next generation of candidate sets, and continuous optimization is carried out to obtain the optimal solution.

4.1. Inner-Layer Module

Once the system is given , we define constants and , which represent that assisting node q and computing node utilize all their computing resources for intermediate feature generation and feature fusion, i.e., and . Similarly, we define constant , which represents that the system uses the entire communication bandwidth to transmit perception information, i.e., . We substitute into Problem P1 and obtain the following:

The resource allocation sub-problem P2 is a constrained optimization problem, where the goal function is curved because it satisfies the properties of positive semi-definite matrices. However, in the latency constraints, terms such as , , and are inherently non-convex, which makes the entire problem non-convex and unsuitable for direct solution using standard linear programming techniques. To address this issue, we adopt the framework of second-order cone programming (SOCP) to transform the non-convex latency constraints into convex forms.

We define the following new variables:

where , , and .

Substituting the new variables into the original latency constraints, the nonlinear constraints containing reciprocal terms can be transformed into linear constraints:

This linear constraint satisfies the convexity requirement; however, the variable substitution process introduces new nonlinear equality constraints:

To transform the nonlinear equality constraints of Equations (29)–(31) into convex constraints, we introduce the mean value inequality as a bridge.

For any positive real numbers a and b, the mean value inequality satisfies , where the equality holds if and only if . Then,

Multiplying both sides by two yields the linear inequality constraint:

Equations (38)–(40) are all convex constraints, however, the equivalence with the original equality constraints cannot be guaranteed solely through such linear inequalities. Therefore, it is necessary to further transform them into the standard constraint form of SOCP to ensure the equivalence of constraints during the optimization process.

The core constraint form of SOCP is that the Euclidean norm of a vector is not greater than a certain scalar. Specifically, for an q-dimensional second-order cone , the constraint can be expressed as , where is an -dimensional vector, t is a non-negative scalar, and denotes the Euclidean norm.

For Equation (38), we construct a one-dimensional vector , for which its Euclidean norm is

Meanwhile, we define the scalar . From Equation (38), we know that , which satisfies the requirement of the second-order cone constraint for a non-negative scalar. At this point, Equation (38) can be rewritten as

This inequality conforms to the standard form of the second-order cone constraint , that is,

where is a two-dimensional second-order cone.

Similarly, for Equations (39) and (40), we, respectively, construct one-dimensional vectors and and define scalars and , from which the corresponding second-order cone constraints can be obtained:

The original non-convex resource allocation sub-problem P2 is finally converted into a standard SOCP problem:

Subsequently, the interior point method is used for solving it.

4.2. Outer-Layer Module

The external optimization module adopts GA to iteratively optimize decision variables S, W, and U. Specifically, the algorithm first randomly initializes a population P consisting of I individuals, where each individual is composed of a set of decision variables .

During the evolution of the j-th generation, the internal optimization module is invoked to calculate the minimum resource consumption of each individual , using the formula given in (41). Then, the fitness function is defined as ; in other words, individuals with lower resource consumption have higher fitness. This transforms the resource consumption minimization problem into a fitness maximization problem that can be directly optimized by GA.

Based on the fitness evaluation results, the algorithm employs an elite selection method to select the two best-performing individuals as parent individuals (denoted as and , where a and b are the indices of the parent individuals in the j-th generation). Subsequently, a crossover operation is performed on the genes of the two parent individuals with a crossover probability : A crossover point is randomly selected in the decision variable sequence, and the gene segments on both sides of the crossover point are exchanged to generate a candidate offspring . For example, if the parent individuals and undergo crossover between W and U, the candidate offspring may be .

To maintain population diversity, a mutation operation is applied to the candidate offspring with a mutation probability : A random decision variable is selected, and its value is randomly perturbed (e.g., fine-tuning the real-coded value within a reasonable range or flipping the binary-coded bit) to obtain the mutated candidate offspring .

Afterwards, a constraint check is performed to verify whether satisfies all constraints (from P2). If it satisfies the constraints, it is incorporated into the -th generation population as a new individual ; if not, the parent individual with higher fitness (either or ) is copied to by default to ensure a stable population size.

The above processes of selection, crossover, mutation, and constraint checking are repeated until the number of iterations reaches the predefined maximum number of generations. At this point, the decision variables corresponding to the individual with the highest fitness in the population are the global optimal solution.

5. Experiments

5.1. Environmental Settings

To train the collaborative accuracy prediction model, we construct a cooperative perception scenario based on the OPENV2V dataset [8]. This scenario contains Q CAVs, one RSU, and one MEC unit, all of which are equipped with slimmable network models. The network width is set to to represent different model architectures.

For object detection, we use the AI model employed in Where2comm for implementation. We collect the object detection results of each frame and the cooperative topological relationships, and we employ the mean squared error (MSE) loss function to compute the discrepancy between the predicted values and the true labels, thus facilitating the training of the accuracy-aware model.

The perception latency requirement is set to , and the accuracy requirement is set to . Other system parameters (e.g., bandwidth, transmit power, computing resources) are detailed in Table 2. To simplify, we presume that all nodes have identical received noise power, transmit power, channel attenuation factor, and computing resources. By setting the weight coefficient , we consider the minimization of total computing resource cost and total communication resource cost to be of equal importance in the optimization objective.

Table 2.

System parameters in experiment.

5.2. Experimental Result

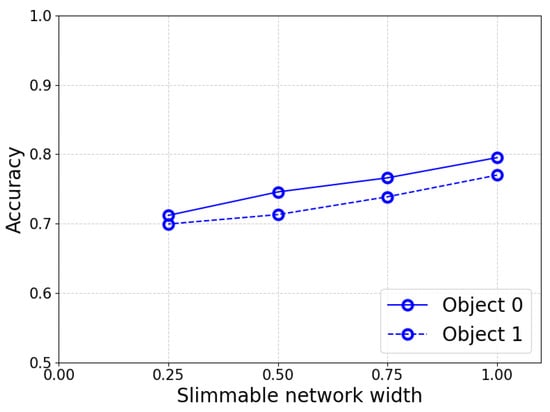

First, we demonstrate the necessity of incorporating bounding box dimension information into the input of the accuracy-aware perception model. Specifically, in the single RSU perception scenario, we systematically evaluate the correlation between the number of point clouds corresponding to target objects and their perception accuracy, with a focus on examining the impact of different target sizes (i.e., geometric scales). We take a larger truck and a smaller cyclist as examples. Figure 3 presents the perception accuracy achieved by the truck and the cyclist employing the respective two sets of perception data.

Figure 3.

Performance of slimmable network when observing different targets. Note that perception accuracy (y-axis) improves as the network width (x-axis) increases. Crucially, the marginal gain diminishes at higher widths, suggesting that a dynamic trade-off strategy can save resources without significantly compromising performance.

We first demonstrate the difference in perception accuracy between collaborative perception and single-RSU perception. Specifically, under the same edge noise conditions, we collect perception data from the RSU and assisting CAVs and test the perception accuracy of different perception mechanisms for the same object. Among them, the cooperative perception mechanism adopts slimmable network and computation offloading technology. As shown in Table 3, the perception accuracy under the cooperative perception mechanism is significantly superior to that under the single-RSU perception mechanism. This finding suggests that the feature fusion mechanism notably boosts the RSU’s object detection ability, thereby offering solid proof for the validity of the presented cooperative perception mechanism.

Table 3.

Differences in perception accuracy between cooperative perception mechanism and single-RSU perception mechanism.

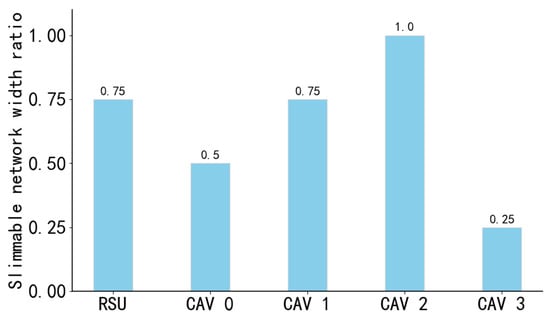

Meanwhile, to investigate the impact of slimmable network width on perception accuracy, we test the influence of slimmable networks on the perception accuracy of a single RSU. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the experiment also indicates that under the same conditions, the larger the width of the slimmable network, the higher the perception accuracy it can further achieve; however, this is accompanied by higher computing resource consumption. This further demonstrates that improving perception performance requires a trade-off between accuracy and resource consumption.

Figure 4.

Application of slimmable network in collaborative perception scenarios. This diagram illustrates the heterogeneous network width configurations assigned to different agents (RSU and CAVs). For instance, while CAV 2 operates at full width (1.0) to maximize feature quality, CAV 3 is restricted to a width of 0.25, demonstrating the system’s granular control over “intelligent elasticity” to adapt to individual link conditions.

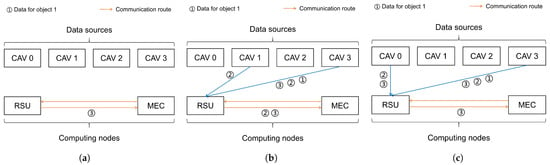

Next, we examined the performance of the proposed model, using a trained accuracy estimation learning model. Figure 5 illustrates the variations in collaborative perception and computation offloading methods across various scenarios. Every arrow in the figure represents the transmission of perception data.

Figure 5.

Collaborative perception and computation offloading schemes across various scenarios. (a) Under low accuracy requirements (), the RSU operates independently. (b) When accuracy demands an increase (), collaboration is triggered (blue arrows). (c) Under high computational intensity, tasks are further offloaded to the MEC (orange arrows). These transitions visually confirm the system’s dynamic decision-making capability in response to changing task demands.

Figure 5a,b show the collaborative perception and computation offloading methods under different accuracy requirements. For the lower accuracy requirement with , the RSU does not require collaborative perception to complete the target detection task. Figure 5b,c show the collaborative perception and computation offloading methods under different computational intensities. Specifically, to further verify the superiority of the proposed model in terms of resource consumption, we compare it with three representative benchmark methods. Table 4 summarizes the key characteristics of these methods, including differences in the granularity control of collaboration mechanism and slimmable network width allocation. Specifically, C4I-JO corresponds to our proposed method; SCFW selectively collaborates with some assisting CAVs but adopts a fixed network structure instead of a slimmable network; ACSW collaborates with all assisting CAVs within the perception range and incorporates the slimmable network; ACFW also collaborates with all assisting CAVs but does not use a slimmable network. Additionally, to verify the effectiveness of computation offloading technology, we further incorporated SCSW and conducted comparative experimental analyses between SCSW and C4I-JO, considering C4I-JO in two scenarios: with and without the adoption of computation offloading technology.

Table 4.

Experimental setup of baseline methods and our proposed method.

Table 5 provides a detailed comparison of the perception accuracy and processing latency of different methods in the object detection sub-task. Specifically, under the same scenario, we evaluated the perception accuracy of three objects (indexed as 0, 1, and 2), as well as the overall processing latency. The experimental results show that all four methods achieve satisfactory perception accuracy; however, the latency performance of ACFW fails to meet the system’s real-time requirement (20 ms) and is therefore excluded from subsequent analysis. By comparing C4I-JO and SCSW, we found that computation offloading technology can effectively reduce task processing latency. Meanwhile, considering that SCSW consumes less communication and computing resources than C4I-JO, as C4I-JO only uses computing resources on the RSU and does not communicate with the MEC, SCSW was also excluded from subsequent analyses. Specifically, the processing delay reported in Table 5 is estimated using the system models defined in Section 3. It comprises the computation time for feature extraction and fusion (calculated via Equations (9) and (10)) and the communication transmission time (calculated via Equations (16) and (18)). The results confirm that by offloading computation and adjusting model width, C4I-JO effectively minimizes the total latency defined in Equation (21). Through quantitative comparison, we can comprehensively evaluate the trade-off performance of the proposed model between perception accuracy and resource consumption.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of baseline methods and our proposed method. Note: Perception accuracy is measured as a confidence score (scale 0–1), and processing delay is measured in milliseconds (ms), calculated based on the summation of computation and transmission times defined in Equation (21).

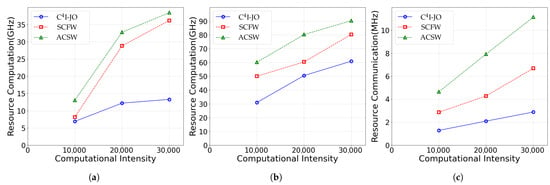

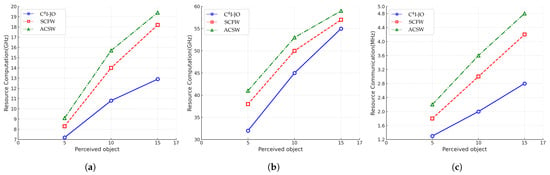

Figure 6 shows the change in resource consumption of each method as the computational intensity increases from 10,000 to 30,000. It can be observed that as the computational demand rises, all methods exhibit rising trends in both communication and computational resource consumption. Figure 7 illustrates the variation in resource consumption for each method as the number of perceived objects within the ROI increases. It can be observed that, with the rise in computational intensity and the greater number of perceived objects, all methods exhibit an ascending trend in both communication and computation resource consumption. Meanwhile, compared with the baseline methods, the proposed joint optimization method significantly reduces resource consumption while maintaining perception accuracy and latency performance. Such results firmly demonstrate the validity and advantages of the presented framework in enhancing resource utilization efficiency.

Figure 6.

Resource consumption with increasing computational intensity. (a) Total computing resource consumption in the intermediate feature generation phase. (b) Total computing resource in the feature fusion phase. (c) Total communication resource consumption. Observe that as the computational intensity rises, the proposed C4I-JO method (blue line) consistently maintains significantly lower resource consumption compared to the baselines (SCFW and ACSW), demonstrating the efficiency advantage gained by jointly optimizing intelligence elasticity and resource allocation.

Figure 7.

Resource consumption with increasing perceived objects. (a,b) Total computing resource consumption in feature generation and fusion phases. (c) Total communication resource consumption. Observe that while resource demand scales with the number of objects, the proposed C4I-JO method (blue line) exhibits a significantly slower rate of increase compared to benchmarks, highlighting its superior scalability in dense traffic scenarios.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a joint resource and intelligence optimization method C4I-JO for multi-vehicle collaborative perception. By introducing intelligent elasticity, we break the bottleneck of static AI models in dynamic V2X environments. Quantitative results demonstrate the superiority of this approach: C4I-JO achieves a low processing latency of 6 ms, which is approximately 53% lower than the baseline SCFW method (13 ms) and 57% lower than ACSW (14 ms), while maintaining high perception accuracy (confidence score > 0.9). Furthermore, the simulation results confirm that under high computational intensity (intensity = 30,000), our method reduces the total computing resource consumption by approximately 30% compared to full-width collaboration schemes. These results firmly establish that jointly optimizing the collaborative mechanism, resource allocation, and network width significantly improves resource utilization efficiency.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain for future work. First, our current model assumes perfect channel state information (CSI), which may not hold true in highly dynamic V2X environments. Future work will focus on enhancing the system’s resilience against communication failures and packet loss. Second, regarding scalability, the centralized optimization approach may face computational bottlenecks in extremely high-density traffic. We plan to explore hierarchical offloading strategies to address this. Finally, addressing the practical implementation challenges of synchronizing heterogeneous hardware across different vehicle platforms remains a priority.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; Methodology, L.X.; Validation, X.F.; Resources, G.Z.; Data curation, X.F.; Writing—original draft, L.X. and H.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Q.Y.; Supervision, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2022YFB4300400 and Grant 2023YFB4301900.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Liang Xin, Guangtao Zhou and Zhaoyang Yu were employed by China Unicom Smart Connection Technology Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bai, Z.; Wu, G.; Qi, X.; Liu, Y.; Oguchi, K.; Barth, M.J. Infrastructure-Based Object Detection and Tracking for Cooperative Driving Automation: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Aachen, Germany, 4–9 June 2022; pp. 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Feng, C.; Xie, X.; Shi, B.; Lu, H.; Lv, Y.; Yang, M.; Niu, Z. Multi-Sensor Fusion and Cooperative Perception for Autonomous Driving: A Review. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2023, 15, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Nguyen, D.C.; Azghadi, M.R.; Xia, Y.; Han, Q.-L.; Sun, S. V2X Cooperative Perception for Autonomous Driving: Recent Advances and Challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.03525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-H.; Manivasagam, S.; Liang, M.; Yang, B.; Zeng, W.; Tu, J.; Urtasun, R. V2VNet: Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication for Joint Perception and Prediction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.07519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, S.; Wu, P.; Chen, S.; Feng, C.; Zhang, W. Learning Distilled Collaboration Graph for Multi-Agent Perception. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2111.00643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Qu, K.; Zhuang, W.; Shen, X. Accuracy-Aware Cooperative Sensing and Computing for Connected Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 23, 8193–8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, N.; Yang, J.; Huang, T. Slimmable Neural Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.08928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Xiang, H.; Xia, X.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J. OPV2V: An Open Benchmark Dataset and Fusion Pipeline for Perception with Vehicle-to-Vehicle Communication. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2109.07644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Tian, J.; Ma, C.-Y.; Glaser, N.; Kuo, C.-W.; Kira, Z. Who2com: Collaborative Perception via Learnable Handshake Communication. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 6876–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Tian, J.; Glaser, N.; Kira, Z. When2com: Multi-Agent Perception via Communication Graph Grouping. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 4105–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Fang, S.; Lei, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, S. Where2comm: Communication-Efficient Collaborative Perception via Spatial Confidence Maps. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.12836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Xiang, H.; Tu, Z.; Xia, X.; Yang, M.-H.; Ma, J. V2X-ViT: Vehicle-to-Everything Cooperative Perception with Vision Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.10638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, S.; Huo, X.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Q. VIMI: Vehicle-Infrastructure Multi-view Intermediate Fusion for Camera-based 3D Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Joint Power and Bandwidth Allocation for Internet of Vehicles Based on Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 20th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Shenyang, China, 20–22 October 2021; pp. 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Song, T.; Song, X.; Wang, C.; Jin, Z.; Hu, J. Energy-Efficient Resource Allocation for NOMA-Enabled Vehicular Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 12042–12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tang, L.; Wang, W.; He, X.; Chen, Q.; Zeng, X.; Jiang, H. Resource Allocation in DT-Assisted Internet of Vehicles via Edge Intelligent Cooperation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 17608–17626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xia, M.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Gong, Y. Optimal Resource Allocation for Integrated Sensing and Communications in Internet of Vehicles: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 3028–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Wu, Q.; Fan, P.; Cheng, N.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Letaief, K.B. Graph Neural Networks and Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation for V2X Communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 3613–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Osaba, E.; Onieva, E.; Perallos, A.; Iovino, G.; Fernández, P. Design and Field Experimentation of a Cooperative ITS Architecture Based on Distributed RSUs. Sensors 2016, 16, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobaed, S.; Mokhtari, A.; Champati, J.P.; Kourouma, M.; Salehi, M.A. Edge-MultiAI: Multi-Tenancy of Latency-Sensitive Deep Learning Applications on Edge. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/ACM 15th International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing (UCC), Vancouver, WA, USA, 6–9 December 2022; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wu, Q.; Fan, P.; Cheng, N.; Chen, W.; Letaief, K.B. DRL-Based Federated Self-Supervised Learning for Task Offloading and Resource Allocation in ISAC-Enabled Vehicle Edge Computing. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 11, 12042–12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Huang, T. Universally Slimmable Networks and Improved Training Techniques. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.05134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, B.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Chang, X. Dynamic Slimmable Network. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.13258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Gao, J.; Li, L.; Hu, W. DSPNet: Towards Slimmable Pretrained Networks based on Discriminative Self-supervised Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.06075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Slimmable Networks for Contrastive Self-supervised Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2209.15525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguezzi, S.; Faiedh, H.; Souani, C. Slim MobileNet: An Enhanced Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 18th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Monastir, Tunisia, 22–25 March 2021; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elminshawi, M.; Chetupalli, S.R.; Habets, E.A.P. Slim-Tasnet: A Slimmable Neural Network for Speech Separation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics (WASPAA), New Paltz, NY, USA, 22–25 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Huang, T. AutoSlim: Towards One-Shot Architecture Search for Channel Numbers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.11728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).