Abstract

In this paper, a stability analysis was conducted of the lateral torsional buckling of the beam of a braced portal frame. The elastic critical resistance (ECR) of the frame was estimated for: (a) a volumetric 3D model (Abaqus/CAE 2017) including the interaction of the component members (beam, columns) in welded corner joints and (b) a simplified 1D bar model (LTBeamN, v 1.0.3) including the parameters of elastic restraint (at support nodes) for the so-called critical member extracted from the structure. In the case of the analysed portal frame, the critical member that determines the lowest elastic critical load of the frame was the transversely bent beam. The following parameters of the elastic restraint of the beam in the support members were taken into account: (1) restraint against warping, (2) restraint against lateral rotation, and (3) restraint against rotation in the bending plane My. The paper demonstrates that the use of a simplified model can enable an efficient and, from an engineering point of view, sufficiently accurate estimation of the ECR of the analysed braced portal frame. The underestimation of the calculated elastic critical resistance of the structure in the simplified 1D model (discrepancies of −10.3% to −18.8%) is compensated for by the lack of the need to prepare a relatively complex volumetric 3D model of the frame (Abaqus). Warping restraint, when neglected, reduces ECR by up to 25% for HEA300 columns.

1. Introduction

One of the so-called eigenvalues of steel bar structures (e.g., frames or grillages) is elastic critical resistance (ECR). This resistance can be measured by the elastic critical load (ECL) that, when exceeded, causes a bifurcation of the equilibrium of the structure, i.e., the structure loses its elastic stability.

The loss of spatial stability of steel bar structures can be considered on the level of the entire structure (3D), e.g., frame [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9], grillage [10,11,12,13,14] or dome [15,16,17,18], or on the level of a critical member (1D) extracted from the structure, e.g., a column or beam, with consideration of the degree of its elastic restraint in the nodes. The choice of the method used to efficiently determine the elastic critical resistance of the structure largely depends on its complexity, which affects the scale of the task. For structures that are simple in terms of geometry and loads, e.g., flat structures, their ECR can be correctly determined using two methods (i.e., in a spatial 3D system and on the level of an extracted 1D bar member), and the independently determined ECLs can be compared with each other, as was confirmed, for instance, in [10].

Software based on the finite element method (FEM) can be used for a spatial (3D) and comprehensive analysis of the stability of steel bar structures. A relatively accurate 3D model of a steel structure can be prepared, for instance, in the Abaqus or ANSYS software. In the case of Abaqus, it is possible to use volumetric [10,19,20] or shell [6,7,11,21,22] finite elements to model the entire structure, including the detailed features of the structures of joints (e.g., frames or grillages) at which the members of the system (beams, columns) are connected. The topology of the joints, e.g., beam-to-column, in bar structures is crucial for determining their elastic critical resistance, which was confirmed, for example, in [1,2,3,4]. For some rigid connections, e.g., welded nodes, it is possible to obtain full continuity in the transmission of cross-section forces (including bimoments) and displacements (including warping). Structures with such joints can be classified as ‘fully continuous’ systems [23,24].

A relatively accurate stability analysis of steel bar structures, including flat portal frames, can be performed using advanced, developed finite element formulations, e.g., [2,25,26,27]. In [25] kinematic models to simulate the torsion warping restraint and transmission at thin-walled frame joints were proposed. The proposed kinematic models can be used in the stability analysis of frames using beam finite element models. It is discussed how several connection configurations (unstiffened, diagonal-stiffened, box-stiffened, diagonal/box stiffened) influence the torsion warping transmission between the connected members. The obtained results were compared with the values obtained from FEM simulations for the shell model (ANSYS software).

In [26,27] a finite element formulation for the analysis of flat frames with moment connections was proposed. In the moment connections, a box-stiffened connection is used. A simple characterisation the elastic warping behaviour of the connection was taken into account, allowing for their good interaction with the beams’ finite elements. The proposed solutions allow for taking into account the interactions between the beams and columns of the frame. Good agreement of the results was obtained compared to the FEM simulations for the shell model (Abaqus software).

In turn, in [2] it was proposed to determine the critical load of flat frames, including portal frames, using the full beam formulation. The virtual work equation takes into account nonconservative moments and conservative bimoment, which do not occur in typical energy approaches, e.g., [27,28,29,30,31]. The proposed full beam formulation [2] together with the consideration of the strain energy of the joints allows for the analysis of lateral torsional buckling of flat frames. Formulas for consideration of strain energy in the plane of the joint stiffener are presented, taking into account the frequently encountered types of stiffening of welded frame corners (e.g., diagonal-stiffened, box-stiffened, diagonal/box-stiffened). The obtained results were compared with the results of FEM simulation for the shell model (ANSYS software) and the results obtained from typical energy approaches. The high efficiency of the proposed full beam formulation in the stability analysis of flat frames was confirmed.

A concise list of articles describing the development of methodologies for determining critical loads, including critical loads for flat frames, is presented, among others, in [2,27].

Available finite element formulations allow for relatively accurate determination of the elastic critical load for selected types of flat frames, including portal frames [2,27]. They allow for taking into account the stiffness of the beam–column connection, which is very important when determining the ECR of a structure. Their use, however, requires the engineer to have experience in the often advanced numerical preparation of a model of the analysed structure. In such a case, determining the elastic critical load of a frame, e.g., a portal frame, will require much more time and may not be an easy task.

As mentioned earlier, the spatial loss of stability of the structure can also be considered on the level of an extracted bar member (1D), e.g., a beam or column, which is the so-called critical member of the analysed system. In this case, when determining the elastic critical resistance of the member, the conditions of its elastic restraint in the support nodes must be taken into account. In the vast majority of cases, these are elastic restraints that have a non-linear effect on the value of the determined ECL [21,32,33,34,35,36]. In the literature on the subject, including [1,10,21,32,34,36,37,38,39,40], there are analytical formulas available that allow for the estimation of selected parameters of the elastic restraint of the beam in the support nodes. Once these parameters are known, the critical moment Mcr of lateral torsional buckling of the beam can be determined numerically (e.g., in the LTBeamN software) and, in the case of relatively simple loading diagrams, converted into the elastic critical load of the member. Studies [10,41,42] confirm the efficiency and effectiveness of the determination of bar ECR using this method. Based on the Mcr of, e.g., a beam, the relative slenderness (), the reduction factor for lateral torsional buckling () and the lateral torsional buckling resistance moment Mb,Rd can be determined [23].

However, it should be emphasised that for spatial steel structures (frames, grillages), it is not always easy to extraction the so-called critical member (e.g., critical beam). This is related, among other things, to the effect of mutual interaction of bars, which occurs especially in fully continuous systems. Such segregation of structural members into the critical bar and stiffening bars is fairly easy in simple systems. For instance, in study [10], the authors determined the elastic critical load of an H-type simple beam grillage. In this case, the critical beam was the transversely loaded coupling beam, elastically restrained in supporting beams.

In this paper, a simplified method of estimating the critical load for a portal frame, compared to the advanced ones, e.g., [2,27], is proposed. The proposed solution requires the extracted of a critical member (1D) of the frame, which determines the loss of its spatial stability, and the estimation of its elastic critical resistance, taking into account the elastic restraint at the support nodes. The analysis takes into account a portal frame braced in its plane, in which the transversely loaded element is a beam. The load was applied to the top flange of the beam. The critical member of the analysed braced portal frame was extracted based on numerical simulations of the spatial (3D) frame model in Abaqus (FEM). It was found that for the assumed spans of the component members of the frame (beam, columns), the types of cross-sections considered in the analysis and the transverse load applied to the top flange of the beam, the critical member determining the lowest ECL of the frame was the beam. The essentials of this analysis are discussed in further sections of this article.

When determining the elastic critical resistance of the beam, the parameters of its elastic restraint in the welded corners of the frame were taken into account. The assumed parameters (stiffnesses) were estimated based on the bar model and applied in the bar model beam. In the stability analysis, the author considered the impact of: (a) the type of cross-section of the bars (beam, column), (b) the length of the component bars of the frame (beam, column), (c) the method of loading the beam.

It is obvious that the proposed simplified 1D method for estimating the elastic critical resistance of a braced portal frame has its limitations compared to the exact solutions proposed, e.g., in [2,27]. It does not allow for direct consideration of the physical behaviour of the joint in the transmission of displacements, including warping, between connected members. Its advantage, however, is the simplicity of engineering application. It requires analytical estimation of the elastic restraint parameters of the critical member at the support nodes. These parameters are then applied in commercial calculation software, such as LTBeamN, to determine, for simple loading diagrams, the elastic critical load.

The purpose of this paper is to: (a) perform a numerical simulation of the behaviour of a simple, braced portal frame within the elastic critical range, (b) investigate the possibility of determining ECR in braced portal frames based on the analysis of the elastic stability of the critical beam, taking into account the parameters of its elastic restraint in the nodes (simplified 1D model), (c) investigate whether a simplified 1D model with parameters for elastic restraint of the critical member at the support nodes can replace/check/confirm the ECR calculations of the frame based on a much more complex 3D model, (d) investigate the influence of the elastic restraint against lateral rotation (rotation in the beam lateral torsional buckling plane) on the ECL of the critical beam in the lack of members in the plane of action of the elastic restraint, and (e) assess the impact of the change in columns height on the elastic critical resistance of the frame from the condition of the lateral torsional buckling of the beam.

2. Diagram of the Analysed Frame

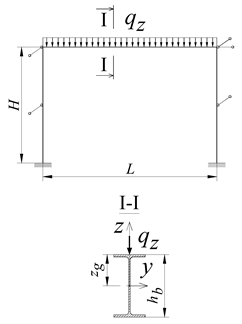

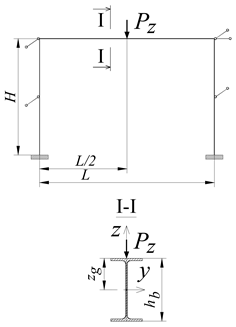

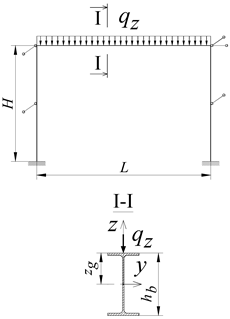

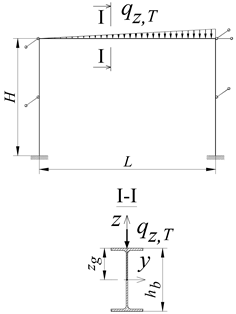

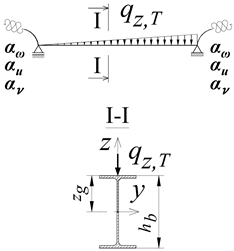

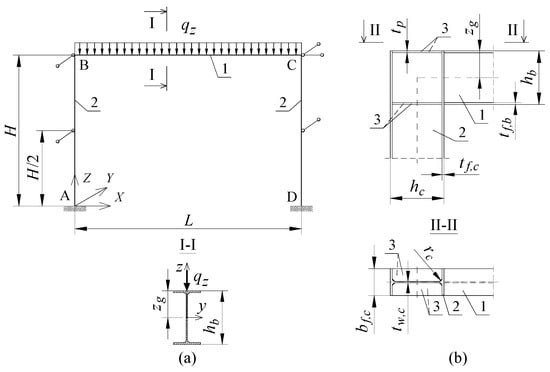

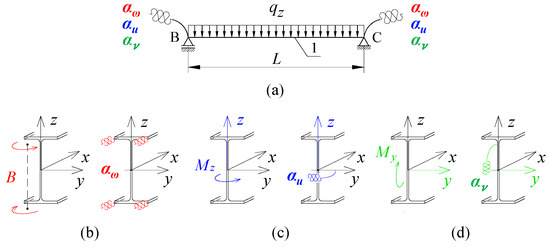

The static diagram of the braced portal frame analysed in the paper is shown in Figure 1a. It was assumed that the frame was braced in its plane (translation blockage) at the height of the beam axis. In the direction perpendicular to the plane of the transverse system, translation was blocked at the corners of the frame (B, C) and in the middle of columns height (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Static diagram of the analysed portal frame. (b) Construction details of corners B and C of the frame. (1—beam, 2—column, 3—flat stiffener).

The B-C beam (Figure 1) was connected to A-B and D-C columns by welding (full penetration butt welds). In corners B and C, the classic stiffening method was used, i.e., flat stiffeners at the height of the beam flanges (Figure 1b). The stiffener thickness (tp) was assumed to be equal to the beam flange (tf,b). It was assumed that the resistance of the welds connecting the beam to the column was not lower than the resistance of the connected members. This makes it possible to maintain full continuity in the transmission of displacements, including warping, and the transmission of cross-sectional forces, including bimoments. At this stage of the analysis, the author did not consider the influence of post-welding stresses and strains in the welded corner joints B and C on the elastic critical resistance (ECR) of the frame. It was assumed that A-B and D-C columns are fully fixed at nodes A and D (Figure 1a).

In the analysis, the author considered two variants of beam cross-section, i.e., IPE300, for the span L = 6 m, and IPE500, for the span L = 9 m. Two types of column cross-section were adopted for each beam variant. For IPE300 (L = 6 m), the columns of the frame were made of the IPE300 or HEA300 section. The author considered four variants of column height H = 3, 4, 5 or 6 m. For IPE500 (L = 9 m), in turn, the author used columns made of the IPE500 or HEA300 section. In this case, the author considered column heights H = 4.5, 6, 7.5 and 9 m.

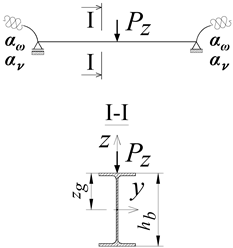

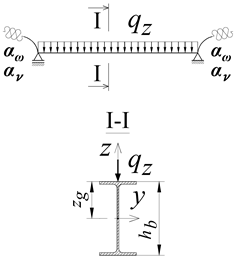

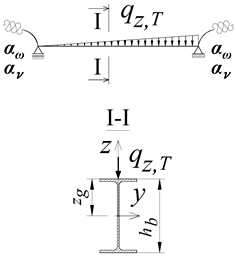

The loading of the portal frame was applied to the top flange (zg = hb/2) of the B-C beam (Figure 1a). Three variants of the transverse load of the beam were considered: (a) concentrated force (Pz) at the midspan of the beam, (b) uniformly distributed load (qz) along the beam, and (c) non-uniformly distributed load (qz,T) along the length of the beam (triangle distributed load).

The geometric dimensions of the adopted cross-sections and their characteristics were selected according to [43].

In the paper, it was assumed that in the corner joints B and C of the analysed braced portal frame (Figure 1a) there is a fully continuous connection model [24], the behaviour of which does not affect the analysis. In order to verify whether the adopted solution of the joint structure (Figure 1b) meets this assumption, an appropriate classification was carried out in accordance with EN 1993-1-8 [24]. Since the critical load was determined in the elastic range, the connection was classified based on its rotational stiffness.

For the assumed parameters of the portal frame components, the welded single-sided corner joints B and C (Figure 1b) were classified as rigid. The classification of beam–column connection according to Eurocode [24] is given in Appendix A.

3. Estimation of the Parameters of the Elastic Restraint of Beam in the Frame Corner

The analysed frame (Figure 1a) consists of three bar members, i.e., A-B and D-C columns and B-C beam. Elastic critical resistance (ECR) was determined for the spatial (3D) frame model and for a critical member (1D) extracted from the structure, elastically restrained in the support nodes. Based on numerical simulations performed in Abaqus software (FEM), the author determined that for the adopted spans of the component members of the frame (beams, columns) and the transverse gravitational load applied to the top flange of the beam, the critical member determining the lowest ECL of the frame would be the beam. The results of the numerical simulations based on which the critical member was selected are included in further sections of this paper.

In this chapter, the author provides a method for estimating the parameters of the elastic restraint of the B-C beam, the critical member of the braced portal frame (Figure 1a) in the welded corner joints B and C, classified as rigid (cf. Table A1).

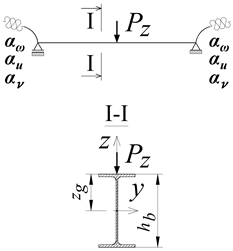

Figure 2a shows the analytical model of the B-C beam, extracted from the system of the analysed frame (cf. Figure 1a). The welded connections used in joints B and C of the frame ensure the elastic restraint of the beam against: (a) warping αω of the support cross-section (Figure 2b), (b) lateral rotation αu of the beam (Figure 2c), and (c) rotation of the beam in the plane of its bending αv (Figure 2d), resulting from the susceptibility of the columns to bending in the plane of the frame.

Figure 2.

(a) Analytical model of the B-C beam. (b) Elastic restraint against warping αω of the beam cross-section at the support. (c) Elastic restraint against lateral rotation αu of the beam. (d) Elastic restraint against rotation in the beam bending plane αv. (1—beam).

The stiffness of the elastic restraint αω (Figure 2b) against warping expresses the value of the bimoment B caused by a unit warping dφ/dx [21,33,44]:

where B—bimoment in the support node, dφ/dx—warping of the beam cross-section.

Stiffness αω (1) ranges from αω = 0 for the full freedom of warping to αω = ∞, for complete warping blockage.

The elastic restraint against warping of the cross-section of the beam in joints B and C is affected (Figure 1b) by the stiffness of the free torsion of the column (at the beam cross-section height) [39] and the stiffness of the free torsion of flat stiffeners, restraining the warping of the cross-section of the column. Stiffness of elastic restraint αω is expressed as:

where It,c—Saint-Venant torsional constant of the column, G—Kirchhoff’s modulus, h0,b = hb − tf,b—theoretical height of beam cross-section at flange axes, h0,c = hc − tf,c—theoretical height of column cross-section at flange axes, —torsional moment of inertia of the flat stiffener. The remaining symbols are shown in Figure 1b.

The stiffness of elastic restraint αu (Figure 2c) against the lateral rotation of the beam in the support nodes (rotation about the z-z axis of the cross-section) expresses the value of the bending moment Mz caused by a unit lateral rotation (du/dx) [33]:

where Mz—bending moment relative to the minor axis of the cross-section in the support node, du/dx—rotation about the z-z axis in the support node.

Stiffness αu (3) ranges from αu = 0 for the full freedom of lateral rotation to αu = ∞, for complete lateral rotation blockage.

In the study, the author assumed that in corners B and C of the frame (Figure 1), the rotation of the beam about the minor axis of its cross-section (z-z) corresponds to the torsion of the column relative to its longitudinal axis (x-x). Such engineering simplification was introduced because the conditions of a rigid beam–column connection between the frame members were met. It was assumed that the torsion moment Mx of the column was equal to the bending moment Mz of the beam. The torsion angle of the column was determined as for a cantilever bar (fixed in nodes A and D), with the assumption that the torsion moment acts at the point of its connection with the beam (node B, C). Its value was determined according to [45], assuming no torsion blockage on the free end of the cantilever bar (column). Note: The critical member of the frame is the beam, i.e., the column is an elastic support for the beam, not the other way around. This assumption is consistent with the idea of the so-called critical member and stiffening member given, for example, in [46], in which the local stability of walls in thin-walled sections was analysed, taking into account the conditions of elastic restraint of the component walls. The critical member (with the lowest load-bearing capacity) is elastically restrained in the adjacent stiffening members. However, in the analysis of the stiffness of the stiffening member loaded with the excitation reaction (from the critical member), a free support can be assumed at the point of their connection [46]. In the case of thin-walled cross-section walls, an elastic restraint of the critical plate in the stiffening plates was assumed, for which a free support was assumed on the same edge. From an engineering point of view, the adopted analytical simplification is a conservative approach.

After accounting for the formula for the column torsion angle [45], corresponding to the lateral rotation of the beam du/dx about the minor axis of the cross-section, the stiffness of the elastic restraint αu can be formulated as follows:

where H—column height, —lateral-torsional characteristic of the column, Iω,c—warping constant of the column.

The stiffness of elastic restraint αv (Figure 2d) against the rotation in the bending plane of the beam (rotation about the y-y axis of its section) expresses the value of the bending moment My caused by a unit rotation in the beam bending plane (dv/dx) [35]:

where My—bending moment relative to the major axis of the cross-section in the support node, dv/dx—rotation about the y-y axis in the support node.

Stiffness αv (5) ranges from αv = 0 for the full freedom of rotation in the bending plane to αv = ∞, for its complete blockage.

For the analysed frame (Figure 1a), with the columns fixed in the support nodes A and D, the elastic restraint against rotation in the beam bending plane (αv) in nodes B and C caused by the elastic action of the columns can be expressed with the following formula:

where Iy,c—second moment of inertia in bending about the y-y axis of the column.

Formula (6) was written in the same manner as the one used in the classic Cross method [47].

The practical calculations of the stiffness of elastic restraint αω, αu, αv for the adopted parameters of the analysed portal frame are given in the next chapter of the article.

4. Numerical Determination of the Critical Elastic Resistance of the Portal Frame

Finite element method (FEM) was used to determine the elastic critical resistance of the frame. The analysis was conducted for the volumetric model (3D), taking into account the behaviour of the entire structure (cf. Figure 1a), and the bar model (1D), taking into account the extracted B-C beam (critical member) and the parameters of its elastic restraint in nodes B and C (cf. Figure 2a).

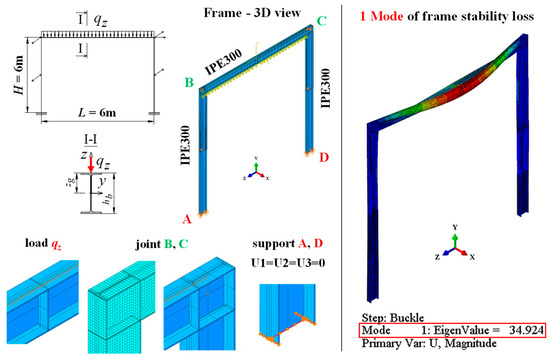

4.1. Volumetric 3D Model—Abaqus

The elastic critical resistance of the braced portal frame (Figure 1a) was determined in the Abaqus software [48] based on finite element method (FEM). The spatial 3D model of the frame was prepared using C3D8R volumetric finite elements (elements with eight nodes, six degrees of freedom in each node). The numerical model takes into account the physical stiffeners of the frame corner joints B and C (cf. Figure 1b). The modelled frame members (beam, columns and joints) were discretised using an FEM mesh with an average mesh size of 20 × 20 × t/4 [mm] (t—wall thickness). The boundary conditions in A and D joints accounted for the blockage of translation, rotation and warping of the support cross-section of the column about its major axes of inertia. Such fixing conditions were obtained by blocking the translation in three directions (U1 = U2 = U3 = 0) of the frontal planes of the support cross-sections of the columns. In the corner joints B and C and at the midspan of the A-B and D-C columns, horizontal translation was blocked (U1 = 0) in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the transverse system of the frame. Also, horizontal translation was blocked in joint C (U3 = 0) in the plane of the frame (cf. Figure 1a).

As already mentioned, the modelled portal frame members were discretised with an FEM mesh with an average mesh size of 20 × 20 × t/4. When selecting the mesh size, the results of 3D Abaqus numerical simulations performed for the grillages were taken into account [10]. At that time, tests were carried out of the mesh size on the determined ECR value. Since the analysed structures (portal frame, grillage) have similar geometric parameters, when determining the ECR of the portal frame (Figure 1a), a mesh with the same parameters as in the grillage was adopted [10].

Table 1 presents the results of additional verification of the mesh size for the FEM model adopted in the work. For this purpose, a numerical model (C3D8R volumetric elements) was prepared for the portal frame analysed in [27] using a 20 × 20 × t/4 [mm] (t—wall thickness) mesh. From the simulation in Abaqus, the critical load Pcr of the frame was obtained and compared (Table 1) with the values presented in [27].

Table 1.

Comparison of elastic critical load Pcr of the portal frame [27].

Small differences in the Pcr values (Table 1) allow us to conclude that for the mesh size adopted in the work (20 × 20 × t/4), the obtained ECR values of the portal frame can be treated as a reference.

The loading of the portal frame was applied in the middle of the width of the top flange (zg = hb/2) of the B-C beam (Figure 1a). The load was applied in the form of (a) a concentrated load at the midspan of the beam, modelled as a concentrated load applied to one node of the mesh, (b) a uniformly distributed load along the length of the beam, modelled as a concentrated load with a constant value applied to the nodes of the mesh in the middle of the width of the flange, and (c) a non-uniformly distributed load with a linearly variable value applied to mesh nodes in the middle of the width of the flange. The method of modelling different parts of the structure for an example portal frame is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A three-dimensional model of an example portal frame made in Abaqus software.

The calculation of the critical load was performed in the elastic range, using the computational step of the buckling procedure.

As mentioned earlier, the elastic critical resistance was determined for the prepared 3D models of the portal frame. The ECR was also determined for a critical member (1D) extracted from the structure, elastically restrained in the support nodes. The critical member of the analysed frame is the member (beam, column) initiating its spatial loss of stability at the lowest ECL value. In order to determine the critical member for the prepared 3D models of the portal frame, the author conducted numerical simulations of the behaviour of the structure in the elastic critical range. The analysis was conducted for the following adopted parameters: (a) spans and types of cross-sections of frame component members (beam, columns) and (b) variants of the transverse gravitational load applied to the top flange of the frame beam.

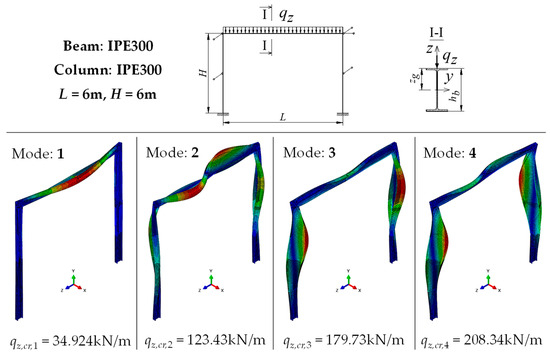

Figure 4 shows the first four modes of the loss of stability of an example portal frame obtained from numerical simulations of the 3D model of the structure. The frame whose component members (beam, columns) were made of an IPE300 section was uniformly loaded (qz) along the length of the beam with a transverse load applied in the middle of the width of the top flange (zg = hb/2) of beam. The elastic critical loads (qz,cr) were determined taking into account the maximum column height (H) for this frame variant. For such geometric parameters of the column, the column has the highest susceptibility to buckling, which may cause it to be the causal member (critical member) of the spatial loss of stability of the frame. Figure 4 shows the first four modes of frame stability loss and their corresponding eigenvalues.

Figure 4.

Modes of the stability loss of an example portal frame modelled in the Abaqus software (beam IPE300 - L = 6 m, column IPE300 - H = 6 m).

For the lowest value of the elastic critical load (qz,cr,1) of the frame, corresponding to the first mode of its spatial loss of stability (Figure 4), the critical member is the beam, which results from its significant deformations. The ECR of the frame is determined by the lateral-torsional mode of stability loss of the beam, elastically restrained in the columns, in accordance with one half-wave of displacements with a shape close to a sinusoidal function. Very slight deformations of the columns result from the continuity of deformation in the joints.

A different situation was observed for the second eigenvalue (qz,cr,2) of the portal frame. In this case, the lateral torsional buckling of the beam took the form of two half-waves of displacements, similar in shape to two half-waves of the sine function. For the second eigenvalue (qz,cr,2), the lateral-torsional deformations of the columns increase (in comparison with those obtained for qz,cr,1), but they still result from the continuity of deformations in the joints. The column as a critical member of the analysed portal frame does not appear until the third (qz,cr,3) and fourth (qz,cr,4) eigenvalue. In this case, advanced lateral-torsional deformations of the columns occur, associated with lateral-torsional deformations of the beam, but with much smaller amplitudes.

Table 2 contains example results of the numerical simulations of 3D models of the portal frame. For a frame loaded uniformly (qz) along the length of the beam, the first four eigenvalues are shown. Similarly to Figure 4, the elastic critical load (qz,cr) was determined for the maximum columns height (H) in the individual frame variants. The author analysed the spatial deformations of the 3D models (cf. Figure 4) for the first four eigenvalues of the system to extraction the critical member (beam, column) responsible for initiating the elastic loss of stability of the frame.

Table 2.

Comparison of the values of elastic critical resistance of the portal frame loaded uniformly.

For the example frames (Table 2), the lowest value of the elastic critical load qz,cr,1 (rows 1, 5, 9, 13) is associated with the lateral-torsional loss of stability of the beam (critical member), according to one half-wave of the sine function (cf. Figure 4). For the second eigenvalue qz,cr,2 (rows 2, 6, 10 and 14), the critical member of the frame is still the beam. In this case, its spatial loss of stability has a course similar to two half-waves of the sine function (cf. Figure 4). The second elastic critical load of the frame (rows 2, 6, 10 and 14) is approx. 3.5 times greater than the first ECL (rows 1, 5, 9 and 13). It is only for the third eigenvalue qz,cr,3 that the column made of an IPE section (rows 3 and 11) becomes the critical member of the frame (cf. Figure 4). For columns made of the HEA section (rows 7 and 15), even the third eigenvalue of the frame is determined by the lateral torsional buckling of the beam. Columns made of wide flange sections (e.g., HEA) are characterised by higher free and constrained torsional stiffness compared to columns made of narrow flange sections (e.g., IPE). Consequently, using wide flange sections for the columns makes it possible to obtain an increased spatial stiffness of the analysed portal frame and higher ECR values of the structural system (cf. col. VI).

For the remaining variants of frame loading, i.e., Pz and qz,T, a similar correlation was found between the eigenvalue (qz,cr,1, qz,cr,2, qz,cr,3, qz,cr,4) of the elastic critical resistance and the criteria for the extraction of the critical member of the system (beam, column).

An analysis of Table 2 and Figure 4 indicates that for the adopted static, geometric, and load parameters of the analysed frames, the critical member determining the lowest value of the critical load (qz,cr,1) is the beam. Consequently, the elastic critical resistance of the frame (Figure 1a) can also be determined for the bar model (1D) based on the critical resistance of the beam, elastically restrained in the corners of the frame.

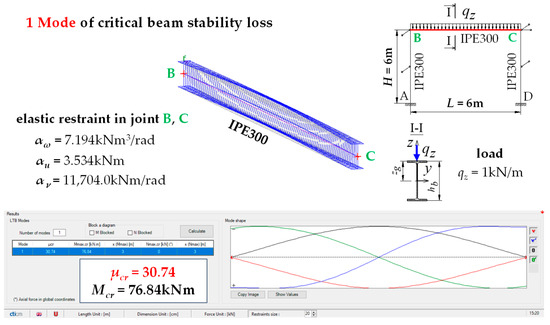

4.2. Bar 1D Model—LTBeamN

The elastic critical resistance from the condition of the lateral torsional buckling of the beam of the analysed portal frame (Figure 1a) was also estimated using the bar model (1D) in the LTBeamN software [50]. The software is based on thin-walled bar elements (FEM) with seven degrees of freedom at the node.

The LTBeamN is a well-known engineering software that allows the determination of the so-called critical moment (Mcr) of lateral-torsional buckling for transversely loaded mono- or bisymmetric beams. For simple static diagrams of beams, e.g., single-span beams loaded with a single load type (e.g., Pz, qz, qz,T), Mcr determined from the calculations can easily be converted into the critical load of the beam (e.g., Pz,cr, qz,cr, qz,T,cr). The software allows for taking into account, among others, complex conditions of elastic restraint of beams in support nodes. In the default software settings, the analysed beams are discretized using 100 bar (thin-walled) finite elements.

The elastic critical resistance of the analysed frame (Figure 1a) was determined based on the critical resistance of the B-C beam (1D model), taking into account its elastic restraint in nodes B and C (cf. Figure 2a). This critical resistance, in turn, was determined based on Mcr determined using the LTBeamN software. According to the adopted static diagram of the portal frame (Figure 1a), the B-C beam is braced in the longitudinal direction (blockage of horizontal translation in node C) and secured in the support nodes (at the beam–column contact) against displacement in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the analysed transverse system (blockage of horizontal translation in nodes B and C). The vertical translation of the support nodes of the B-C beam is blocked by the A-B and D-C columns.

For the analysed B-C beam (Figure 2a), the parameters of elastic restraint (αω, αu, αv) in the support nodes (B, C) were estimated based on analytical Formulas (2), (4) and (6). Table 3 provides a summary of the values of the above-mentioned parameters.

Table 3.

Summary of estimated stiffnesses of the elastic restraint of the B-C beam for the assumed geometric parameters of the portal frame.

Figure 5 shows the results of calculations from the LTBeamN software (elastic critical load of an example beam B-C constituting the beam of a portal frame).

Figure 5.

Elastic critical resistance and lateral torsional buckling mode for an example B-C beam (beam IPE300 - L = 6 m, column IPE300 - H = 6 m) according to the LTBeamN software.

The proposed 1D bar model (LTBeamN), taking into account the elastic restraint parameters (αω, αu, αv) at the support nodes, requires checking the accuracy of the ECR estimation of the beam representing the portal frame. For this purpose, the critical load of the portal frame analysed in [2] was compared with the critical load estimated (according to the 1D model) for the beam of this frame. The geometric and material parameters of the frame analysed in [2] were taken from [27]. The analysed frame was loaded in its plane with two concentrated forces applied at equal distances along the length of the beam. The critical load Pcr of the frame [2] was determined taking into account the advanced description of the full beam formulation, to which standard types of frame corner stiffening, e.g., Box-stiffened, can be added. The obtained results [2] were compared with the FEM simulation results for the shell model (ANSYS software) and the results obtained from typical energy approaches. The high efficiency of the method proposed in [2] was confirmed. Since the critical member of the frame, due to the applied loading diagram, is the beam, it was decided to determine its Pcr using the proposed 1D bar model (LTBeamN). Using the geometric parameters, including the Box-stiffened corner type, and the material parameters of the portal frame [27], the parameters of the elastic restraint of beam in the frame corners were estimated using Formulas (2), (4) and (6): αω = 12.506 kNm3/rad, αu = 11.517 kNm, αv = 12,264 kNm/rad. Taking into account the beam length corresponding to the span of the portal frame [27], the critical load was determined in the LTBeamN software: Pcr = 272.55 kN. The critical load determined in [2] (Element: 7 DOF, beam: 30 elements, column: 20 elements) for the Box-stiffened corner type is: Pcr = 280.4 kN. Using the proposed 1D bar model (LTBeamN), a comparable value of the beam critical load was obtained, a difference of −2.8%, in relation to the frame critical load value determined by the method proposed in [2]. The obtained discrepancies allow us to conclude that for the proposed portal frame (Figure 1a) with a Box-stiffened corner (Figure 1b), the critical load can be estimated using a 1D engineering bar model (LTBeamN).

5. Comparative Analysis of the Elastic Critical Resistance of the Portal Frame

In this chapter, a comparative analysis of the elastic critical resistance of the frame, determined using the Abaqus software (3D model), with the critical resistance of the elastically restrained beam B-C, determined using the LTBeamN software (1D model), was performed. For the 1D bar model, the elastic restraint parameters (αω, αu, αv) in the nodes resulting from the geometry of the frame structure (cf. Table 3) and the analysed transverse load (concentrated force Pz, uniform load qz, triangular load qz,T) applied to the top flange (zg = hb/2) of beam B-C were taken into account.

In Table 4, the author compared the elastic critical resistance Pz,cr of the structure loaded with the concentrated force Pz at the midspan of the B-C beam.

Table 4.

Comparison of the elastic critical resistance Pz,cr of the portal frame.

The values included in Table 4 indicate that the ECR (Pz,cr) of the portal frame determined for the model of the extracted critical beam (1D) and calculated using the LTBeamN software (column VII) is smaller in comparison with the ECR determined in the Abaqus software (column VI). The discrepancies in the results range from −11.4% (row 12) to −17.5% (row 8).

Table 5 compares the values of the elastic critical resistance qz,cr (rows 1–16) and qz,T,cr (rows 17–32) of the frame structure, loaded uniformly qz or in a triangle qz,T along the length of the beam B-C, determined using the Abaqus and LTBeamN software. The results are presented in a similar arrangement as in Table 4.

Table 5.

Comparison of the elastic critical resistance qz,cr or qz,T,cr of the portal frame.

In the LTBeamN software (Table 5, column VII), the author obtained, similarly as for the concentrated force Pz (Table 4), smaller critical loads (qz,cr, qz,T,cr) of the frame in comparison with the loads determined in the Abaqus software (Table 5, column VI). In this case, the discrepancies in the results were in the range (column VIII) from −10.3% (row 9) to −18.8% (row 24).

The discrepancies (Table 4 and Table 5, column VIII) of the elastic critical loads (Pz,cr, qz,cr, qz,T,cr) indicate that for the adopted geometric parameters of the portal frame (Table 3) loaded at the height of the top flange of the beam (zg = hb/2), the proposed method for the analytical estimation of the stiffness coefficients of elastic restraint (αω (2), αu (4) and αv (6)) of the B-C beam (Figure 2a) in the frame system is moderately conservative and can be regarded as satisfactory from the engineering perspective. Considering the estimated parameters αω, αu and αv in the LTBeamN software enables a relatively fast determination of the elastic critical load without the need to prepare a complex volumetric solid numerical model of the portal frame, e.g., in the Abaqus software. The proposed analytical-numerical solution (in the 1D model) produces lower (conservative) values of critical loads (Pz,cr, qz,cr, qz,T,cr), from −10.3% to −18.8% (cf. Table 4 and Table 5), in comparison with the volumetric model according to the Abaqus software. The underestimation of the elastic critical loads is caused, among others, by the failure to take into account the spatial behaviour of individual details of the corner joints B and C of the portal frame in the 1D model (Figure 1b). The spatial 3D model of the frame (Abaqus software), prepared from volumetric finite elements, enables full continuity in the transmission of displacements (deformations) between the members connected in joints B and C. Moderately underestimated values of the determined critical loads in the model of the extracted critical beam are a conservative estimation from the perspective of engineering calculations.

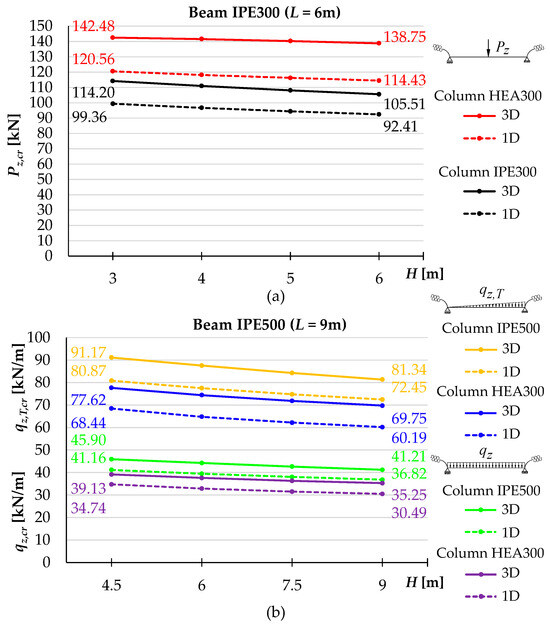

Figure 6 shows exemplary curves of variation in critical loads Pz,cr (Figure 6a) and qz,T,cr, qz,cr (Figure 6b) of the frame as a function of the variable height of the columns determined according to both models (3D, 1D). The critical loads were determined for the loads applied at the height of the top flange (zg = hb/2) of the B-C beam.

Figure 6.

Examples of critical load variation curves: (a) IPE300 beam loaded with concentrated force Pz, (b) IPE500 beam loaded non-uniformly qz,T or uniformly qz.

Increasing the height of the columns (H) of the analysed portal frame (Figure 1a) causes an essentially linear decrease in its elastic critical resistance from the condition of lateral torsional buckling of the beam (Figure 6). For the IPE300 beam (L = 6 m) and the IPE300 columns (Figure 6a), the increase in column height (from 3 to 6 m) caused a decrease in Pz,cr (continuous black line) by 7.6% (Abaqus software). For the HEA300 columns (continuous red line), the author observed a decrease by 2.6%. For the IPE500 beam (L = 9 m), loaded non-uniformly qz,T or uniformly qz (Figure 6b), increasing the height H (from 4.5 to 9 m), irrespective of the cross-section of the column, caused a decrease in the critical load by 10% (Abaqus software). During the determination of the critical load according to the 1D model in the LTBeamN software, the height of the columns (H) was considered in the parameters of the elastic restraint αu according to (4) and αv according to (6) of the B-C beam in the support nodes.

Table 6 compares the values of the elastic critical resistance of the B-C beam, elastically restrained (αv, αω, αu) in the support nodes (cf. Figure 2a), with the critical resistance of the beam determined with consideration of: (a) elastic restraint against αv and αω (for αu = 0) and (b) elastic restraint against αv (for αω = αu = 0). The B-C beam was loaded at the height of the top flange (zg = hb/2) with: (a) concentrated force Pz applied at the midspan of the beam, (b) load qz distributed uniformly, (c) load qz,T distributed over a triangle. The calculations were performed in the LTBeamN software.

Table 6.

Comparison of the elastic critical resistance of the B-C beam.

Disregarding the impact (Table 6) of the elastic restraint against lateral rotation (αu = 0) of the B-C beam in the corner joints B and C of the frame (column VII) causes a negligibly small decrease in the critical resistance of the beam (column VIII). In the vast majority of cases, the decrease in critical load (Pz,cr, qz,cr, qz,T,cr) did not exceed 1.0%. In the case of a flat portal frame (Figure 1a), this is mainly due to the lack of members transferring the Mz bending of the beam and located in the plane of action of the elastic restraint (αu). Moreover, the obtained results confirm the small influence of the torsional stiffness of the A-B and D-C columns of the analysed portal frame (Figure 1a) on its critical resistance from the condition of the lateral torsional buckling of the B-C beam.

The impact of the elastic restraint against lateral rotation (αu) of the critical beam in the support nodes on its elastic critical resistance is much greater in grillages [10]. In structures of this category, the αu of the critical beam depends on the flexural stiffness of the supporting beams. For a simple H-type grillage [10] with a critical beam coupling the support beams, ignoring this parameter resulted in a decreas e in the ECR of the beam by 25%.

When the impact (Table 6) of the elastic restraint against warping (αω = 0) and elastic restraint against lateral rotation (αu = 0) of the B-C beam in corner joints B and C (column IX) is also disregarded, the critical resistance of the beam decreases more significantly (column X). For a frame made entirely of IPE300 sections (beam/columns), in most cases, the decrease in critical load (Pz,cr, qz,cr, qz,T,cr) did not exceed 11%. For the HEA300 column, in turn, the critical resistance of the B-C beam decreased by 25%. The higher decrease in the critical resistance of the IPE300 beam (column X) for the HEA300 columns (rows 5–8, 21–24, 37–40) in comparison with the IPE300 columns (rows 1–4, 17–20, 33–36) was caused, among others, by the significant difference in the value of the moment of inertia for the free torsion of the cross-section of the column (It,cHEA300 ≈ 4.1It,cIPE300) used to estimate stiffness αω (2). For the frame with the IPE500 beam and IPE500 columns (rows 9–12, 25–28, 41–44) or HEA300 columns (rows 13–16, 29–32, 45–48), the decrease in the critical resistance of the B-C beam assuming αω = αu = 0 (column IX) did not exceed 13% (column X).

Table 6 does not show the elastic critical load of the B-C beam determined without the impact of the elastic restraint against rotation αv in its bending plane. Considering αv = 0 would be equivalent to assuming free support of the beam in bending about its major axis. Such a static diagram of the beam is inconsistent with the diagram of the analysed braced portal frame (Figure 1a). For the analysed B-C beam, it would also be incorrect to assume it to be fully fixed, i.e., αv = ∞, because the A-B and D-C columns do not permit to maintain such a static diagram due to their susceptibility to bending My. Consequently, to obtain reliable results for the analysed beam, it is necessary to consider the coefficient of elastic restraint αv. More information about the impact of the elastic restraint against the rotation of the beam in its bending plane on the critical resistance has been included, in particular, in paper [35].

As already mentioned, the analysis of the obtained critical loads (Table 6) for the braced portal frame (Figure 1a) loaded at the height of the top flange (zg = hb/2) shows a small influence of the stiffness αu on the ECR of the critical beam (column VIII). Omitting this parameter of the elastic restraint of the B-C beam, i.e., assuming αu = 0, causes a slight decrease in its critical load. In this case, the elastic critical resistance of the beam depends mainly on the elastic restraint against warping (αω) and against rotation in the beam bending plane (αv). For the analysed B-C beam, it was decided to determine, taking into account the stiffness αω and αv, an important design parameter, namely the critical moment (Mcr) of lateral torsional buckling. Mcr(αω, αv) was determined in the LTBeamN software, taking into account αω and αv (Table 3), and estimated analytically according to [35]. The determined critical moments are given in Appendix B (Table A2). The obtained discrepancies in the Mcr(αω, αv) values ranged from −5.2% to +0.3%. The obtained results (Table A2) allow us to conclude that for selected loading diagrams of a flat portal frame, the critical moment of lateral torsional buckling of the beam can be estimated, taking into account the stiffnesses αω and αv, using [35].

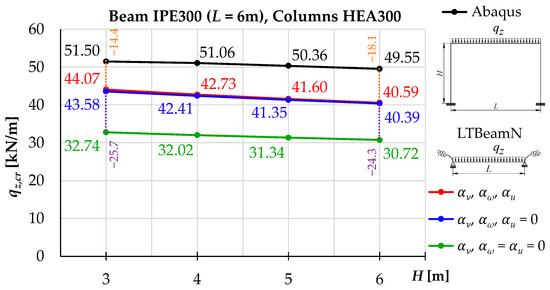

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the elastic critical load qz,cr determined for the frame consisting of an IPE300 beam and HEA300 columns. The frame was loaded uniformly (qz) at the height of the top flange of the beam (zg = hb/2). Figure 7 was prepared based on the values included in Table 5 and Table 6.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the elastic critical load qz,cr of an example frame.

Considering the stiffnesses αv, αω and αu (red line) in the LTBeamN software (Figure 7) made it possible to determine the elastic critical load of the frame, from the condition of the lateral torsional buckling of the beam, in a conservative manner relative to the Abaqus software (black line). The percentage differences between the qz,cr values range from −14.4 to −18.1%. By considering (in the LTBeamN software) only the stiffness αv (αω = αu = 0), the author obtained a reduction in the critical load of the beam by approx. −25% (green line) relative to its full elastic restraint (red line). In comparison with the full 3D model (Abaqus software—black line), in turn, the reduction in elastic critical resistance was approx. −37% (green line, LTBeamN software). Such underestimation of the elastic critical resistance of the frame (beam) does not contribute to its economical and optimal design.

6. Summary and Conclusions

In this paper, a stability analysis was carried out for the lateral torsional buckling of the beam of a braced portal frame (Figure 1a). The elastic critical load was determined for: (a) a volumetric 3D model (Abaqus software) and (b) a 1D bar model (LTBeamN software). The simplified model included a critical member extracted from the structure, in this case a beam and the parameters of its elastic restraint in the support nodes (i.e., in the beam–column joint).

In the analysis, it was assumed that the loaded member was the beam. The transverse load was applied only to the top flange (zg = hb/2) of the B-C beam (Figure 1a). The assumed location of the transverse load of the beam is often encountered in engineering practice. Other variants of the load application point ordinate, including the centre of gravity or the bottom flange of the beam, will be the subject of further studies.

The results (Table 4 and Table 5) indicate that for the simplified model (for the critical beam), the accuracy of determination of the elastic critical load of the B-C beam in the LTBeamN software, while considering the elastic action of the support nodes, is sufficient from an engineering perspective. The underestimation of the elastic critical resistance of the structure, ranging from several to over a dozen percent, is compensated for by the lack of need to prepare the volumetric 3D model of the frame (Abaqus software). The underestimation of the elastic critical load of the beam (1D model) results from: (a) a simplified form of formulas for the parameters of the elastic restraint of the beam in the frame corners, which results from the ‘bar’ consideration (i.e., reduced to the cross-section axis) of the boundary conditions of the elastic restraint and (b) the lack of physical consideration of the complex interaction between frame members in the joint area (interaction of the component walls of the cross-section, stiffener details, etc.). A more accurate determination of the parameters of the elastic restraint of the beam at the frame corners will require taking into account additional factors, which may significantly complicate the calculation model. The author anticipates further research on improving the form of analytical formulas for elastic restraint parameters.

In the case of the analysed portal frame, there is an essentially linear dependence (Figure 6) between the increase in frame column height and the decrease in its elastic critical resistance from the condition of the lateral torsional buckling of the beam. Doubling the height of the columns resulted in a several percent decrease in the elastic critical load.

In the case of the analysed portal frame (Figure 1a), in which columns A-B and D-C are made of open cross-sections profiles (I, H), the influence of the elastic restraint of lateral rotation (αu) of beam B-C in the support nodes on its ECR is negligible (Table 6). This is due mainly to the lack of members transferring the Mz bending of the beam and located in the plane of action of the elastic restraint. Additionally, the considered column cross-sections (I, H) are characterised by relatively low torsional stiffness. In the case of a frame with slender columns, the influence of the elastic lateral rotation restraint (αu) of the beam at the support nodes on its ECR will be even smaller. In this case, the restrained torsional stiffness of the column decreases, which results from the increase in the distance between the frame corner (beam–column joint) in relation to the full restraint against warping in the frame support node. The extension of the portal frame into more complex structural systems, e.g., a spatial frame, will result in an increase in the value of the αu coefficient, because there will be members transferring bending and located in the plane of action of the elastic restraint. In the opinion of the author of this paper, during the determination of the ECR of the beam (in the LTBeamN software) for a typical flat portal frame, it is possible to disregard the impact of the elastic restraint against the lateral rotation (αu) of the beam in its support nodes (in the corners of the frame) to simplify engineering calculations. However, this situation is different from grillage structures, where the restraint against the lateral rotation of the critical beam depends on the flexural stiffness and the number of supporting beams. For a simple H-type grillage [10] with a critical beam coupling the lateral support beams, ignoring this nodal parameter resulted in a decrease in the ECR of the beam by 25%. Disregarding the impact of the elastic restraint against the warping (αω) of the support cross-section of the B-C beam, in turn, resulted—for the selected geometric parameters of the portal frame—in a decrease in its critical resistance by 25% (Table 6). Consequently, it is reasonable to consider this support parameter when determining the critical load of the beam. Disregarding it could result in an excessively conservative selection of the cross-section of the B-C beam and, consequently, a less economical design of this class of portal frame.

General note: The value of the αu parameter is influenced by the geometry of the structural system (e.g., flat frame, spatial frame, grillage) in the form of the presence or absence of members transferring bending and located in the plane of the elastic restraint (in the case of a grillage αu is significant, but not for a flat frame because there are no members transferring bending and located in the plane of the elastic restraint).

The numerical tests carried out for typical braced portal frames made of open cross-section profiles (I, H) and loaded at the height of the top flange of the beam allowed us to conclude that: (a) the ECR of the frame can be estimated based on the ECR of the critical beam, taking into account the parameters of its elastic restraint at the welded frame corners (simplified 1D bar model), (b) the influence of the elastic restraint of beam (critical member) on the lateral rotation (αu) in the welded 2D frame corner is negligible and can be neglected to simplify the calculations, (c) the critical moment of lateral torsional buckling of the beam (critical member) for the analysed load diagrams (Table 6) can be estimated according to [35], and (d) for the adopted geometric parameters of the braced portal frame (beam/column cross-sections, span L, height H), in most cases there is a relationship of the resistance following ECR1D ≈ 0.87ECR3D (in the case of the frame with beam—IPE300 and column—HEA300, the relationship was found at the level of ECR1D ≈ 0.81ECR3D).

It should be noted that the elastic critical resistances of the portal frame, on the basis of which the conclusions were presented, were determined and estimated using the following assumptions: (1) the portal frame is braced in its plane (at corner C) and in the direction perpendicular to its plane (at corners B and C and at half the height of columns A-B and D-C), (2) the columns are fully fixed at nodes A and D, (3) the transverse load of the frame was applied to the top flange (zg = hb/2) of the B-C beam, (4) three common loading diagrams are taken into account (Pz, qz, qz,T), (5) the beam and columns are made of hot-rolled bisymmetrical I-beams (cross-sections of class no higher than 3 [23]), and (6) the adopted geometric dimensions of the frame meet the condition H = (0.5 ÷ 1)L.

The adopted assumptions constitute a limitation of the simplified 1D model (Figure 2a) proposed in the paper for estimating the ECR of a portal frame from the beam lateral torsional buckling condition. In the 1D solution proposed in this paper, it was assumed that the beam over its entire span (i.e., between the column axes, Figure 1a) is modelled by a single bar element. In fact, this model describes well the behaviour of the beam along the length between the inner flanges of the columns. However, the beam fragments near the supports (already within the connection) are complex plate–wall elements characterised by a more complex state of deformation and stress distribution.

Such an assumption, i.e., adopting a bar model over the entire beam span (i.e., between the column axes), significantly simplifies the 1D calculation model. On the other hand, the adopted solution does not allow for direct consideration of the physical behaviour of the joint (built from shields and plates) in the transfer of deformations between the connected members (beam–column), replacing it with an analytical estimate of the stiffness reduced to the axis of the bar element.

The stability analysis performed is a starting point for the analysis of the elastic stability of more complex structural systems (frames, grillages), with consideration of the interaction of the component members. The next stage of the research will be: (a) development of a procedure for extracting the critical member in more complex bar structures and (b) estimation of the ECR of the system from the condition of lateral torsional loss of stability based on the ECR of the extracted critical member (taking into account the parameters of its elastic restraint in the remaining part of the structure).

Funding

The APC was financed by the research subsidy entitled ‘Loss of stability and load-bearing capacity of single- and double-branch thin-walled steel members’ with number 02.0.22.00/1.02.001 SUBB.BKKB.25001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| αω | elastic restraint against warping in the support node |

| αu | elastic restraint against lateral rotation in the support node |

| αv | elastic restraint against rotation in the beam bending plane in the support node |

| B | bimoment in the support node |

| dφ/dx | warping of the beam cross-section |

| Mz | bending moment in the support node |

| du/dx | rotation about the z-z axis in the support node |

| My | bending moment in the support node |

| dv/dx | rotation about the y-y axis in the support node |

| Pz | concentrated force load at the midspan of the beam |

| qz | uniformly distributed load along the beam |

| qz,T | non-uniformly distributed load along the length of the beam |

| Pz,cr | elastic critical load—concentrated force load |

| qz,cr | elastic critical load—uniformly distributed load |

| qz,T,cr | elastic critical load—non-uniformly distributed load |

| L | beam span |

| h0,b | theoretical height of beam cross-section at flange axes |

| H | column height |

| h0,c | theoretical height of column cross-section at flange axes |

| Iy,c | second moment of inertia in bending about the y-y axis of the column |

| It,c | Saint-Venant torsional constant of the column |

| Iω,c | warping constant of the column |

| k | lateral-torsional characteristic of the column |

| Id | torsional moment of inertia of the flat stiffener |

| E | Young’s modulus |

| G | Kirchhoff’s modulus |

| Sj,ini | the initial stiffness of the connection |

| k1 | factor accounting for the stiffness of the column web panel in the shear zone |

| k2 | factor accounting for the stiffness of the column web in the compression zone |

| k3 | factor accounting for the stiffness of column web in the tension zone |

| AVC | shear area of the column |

| β | transformation factor |

| z | lever length |

| Ib | second moment of area of the cross-section beam |

Appendix A

Classification of beam–column connection according to Eurocode.

In the case of welded single-sided corner joints (Figure 1b), the initial stiffness of the connection Sj,ini is determined using the formula [24]:

where E—Young’s modulus, z = hb − tf,b—lever length, ki—stiffness factor of the i-th component of the connection. The remaining symbols are shown in Figure 1b.

For the analysed joint type (Figure 1b), the standard [24] recommends taking into account three reliable stiffness factors: (a) k1 factor accounting for the stiffness of the column web panel in the shear zone, (b) k2 factor accounting for the stiffness of the column web in the compression zone, (c) k3 factor accounting for the stiffness of column web in the tension zone. The applied flat stiffeners of the joint (Figure 1b), according to [24,51], make it possible to disregard the susceptibility of the column web in the compression zone (k2 = ∞) and tension zone (k3 = ∞). However, it is necessary to consider the factor k1, i.e., column web panel stiffness in the shear zone, which can be determined using Formula (A2) according to [24]:

where AVC = Ac − 2bf,ctf,c + (tw,c + 2rc)tf,c—shear area of the column, Ac—column cross-section area, β ≈ 1—transformation factor [24], z = hb − tf,b—lever length. The remaining symbols are shown in Figure 1b.

To classify a connection with respect to rotational stiffness, it is necessary to compare the initial stiffness of the connection Sj,ini (A1) with the limit stiffnesses specified in [24]. In the case of elastic analysis of a structure, the rigid connections, i.e., fully continuous connections, require the fulfilment of the following criterion:

where Ib—second moment of area of the cross-section beam (Ib = Iy,b), Lb—beam span between column axes (Lb = L), kb—factor. Since the frame is braced in its plane, factor kb = 8 [24].

Table A1 compares the determined initial stiffnesses of the connections Sj,ini (A1) with the stiffnesses determined from Formula (A3), for the adopted frame parameters (beam/column cross-section, beam span, column height).

Table A1.

Classification of joints B and C due to rotational stiffness according to [24].

Table A1.

Classification of joints B and C due to rotational stiffness according to [24].

| Item | Beam L [m] | Column | Sj,ini (A1) [kNm/rad] | kbEIb/Lb (A3) [kNm/rad] | Type of Connection | Type of Framing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| 1 | IPE300 L = 6 m | IPE300 | 59,230.59 | 23,408.00 | rigid | continuous |

| 2 | HEA300 | 87,176.18 | 23,408.00 | rigid | continuous | |

| 3 | IPE500 L = 9 m | IPE500 | 233,178.42 | 89,973.33 | rigid | continuous |

| 4 | HEA300 | 145,613.53 | 89,973.33 | rigid | continuous |

Appendix B

Comparison of the critical moment Mcr(αω, αv) of lateral torsional buckling of B-C beam was determined using the LTBeamN (FEM) software and estimated analytically according to [35].

The procedure for determining the critical moment of lateral torsional buckling of the B-C beam in the LTBeamN software is the same as the procedure for determining its ECR (compare Section 4.2).

Analytical estimation [35] of the critical moment of lateral torsional buckling of B-C beam consists of determining (a) indexes of elastic restraint κω and κv (based on αω and αv) of the beam, (b) critical moments Mcr,o(κω, κv = 0) for a simply supported beam, and Mcr,u(κω, κv = 1), for a bilaterally fixed beam, (c) coefficient of interaction η(κv), (d) critical moment Mcr(κω, κv).

Table A2 compares the critical moments of lateral torsional buckling of B-C beam determined in the LTBeamN software with the moments estimated according to [35].

Table A2.

Comparison of the critical moment of lateral torsional buckling of B-C beam.

Table A2.

Comparison of the critical moment of lateral torsional buckling of B-C beam.

| Item | Load Diagram | Beam L [m] | Column | Critical Moment Mcr(αω, αv) of B-C Beam [kNm] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | H [m] | LTBeamN | Analytical Estimation [35] | % [-] VII-VI | |||

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII |

| 1 |  | IPE300 L = 6 m | IPE300 | 3 | 89.25 | 88.02 | −1.4 |

| 2 | 4 | 90.52 | 88.78 | −1.9 | |||

| 3 | 5 | 91.50 | 89.45 | −2.2 | |||

| 4 | 6 | 92.32 | 90.05 | −2.5 | |||

| 5 | IPE300 L = 6 m | HEA300 | 3 | 98.87 | 99.14 | 0.3 | |

| 6 | 4 | 99.84 | 99.58 | −0.3 | |||

| 7 | 5 | 100.73 | 100.00 | −0.7 | |||

| 8 | 6 | 101.48 | 100.39 | −1.1 | |||

| 9 | IPE500 L = 9 m | IPE500 | 4.5 | 240.22 | 236.96 | −1.4 | |

| 10 | 6 | 243.53 | 238.95 | −1.9 | |||

| 11 | 7.5 | 246.15 | 240.71 | −2.2 | |||

| 12 | 9 | 248.33 | 242.28 | −2.4 | |||

| 13 | IPE500 L = 9 m | HEA300 | 4.5 | 249.02 | 242.72 | −2.5 | |

| 14 | 6 | 251.87 | 245.53 | −2.5 | |||

| 15 | 7.5 | 253.82 | 247.76 | −2.4 | |||

| 16 | 9 | 255.11 | 249.56 | −2.2 | |||

| 17 |  | IPE300 L = 6 m | IPE300 | 3 | 82.10 | 79.96 | −2.6 |

| 18 | 4 | 73.87 | 71.87 | −2.7 | |||

| 19 | 5 | 75.46 | 73.42 | −2.7 | |||

| 20 | 6 | 76.73 | 74.69 | −2.7 | |||

| 21 | IPE300 L = 6 m | HEA300 | 3 | 117.30 | 115.95 | −1.2 | |

| 22 | 4 | 110.39 | 108.93 | −1.3 | |||

| 23 | 5 | 104.18 | 102.71 | −1.4 | |||

| 24 | 6 | 98.61 | 97.15 | −1.5 | |||

| 25 | IPE500 L = 9 m | IPE500 | 4.5 | 221.55 | 216.10 | −2.5 | |

| 26 | 6 | 199.22 | 194.16 | −2.5 | |||

| 27 | 7.5 | 203.42 | 198.26 | −2.5 | |||

| 28 | 9 | 206.73 | 201.65 | −2.5 | |||

| 29 | IPE500 L = 9 m | HEA300 | 4.5 | 209.62 | 204.59 | −2.4 | |

| 30 | 6 | 214.15 | 209.58 | −2.1 | |||

| 31 | 7.5 | 217.30 | 213.15 | −1.9 | |||

| 32 | 9 | 219.61 | 215.83 | −1.7 | |||

| 33 |  | IPE300 L = 6 m | IPE300 | 3 | 92.20 | 87.60 | −5.0 |

| 34 | 4 | 82.30 | 78.58 | −4.5 | |||

| 35 | 5 | 76.71 | 74.40 | −3.0 | |||

| 36 | 6 | 78.05 | 75.85 | −2.8 | |||

| 37 | IPE300 L = 6 m | HEA300 | 3 | 134.32 | 127.32 | −5.2 | |

| 38 | 4 | 125.57 | 119.50 | −4.8 | |||

| 39 | 5 | 117.83 | 112.55 | −4.5 | |||

| 40 | 6 | 111.00 | 106.36 | −4.2 | |||

| 41 | IPE500 L = 9 m | IPE500 | 4.5 | 248.79 | 236.71 | −4.9 | |

| 42 | 6 | 221.93 | 212.26 | −4.4 | |||

| 43 | 7.5 | 206.85 | 200.88 | −2.9 | |||

| 44 | 9 | 210.24 | 204.75 | −2.6 | |||

| 45 | IPE500 L = 9 m | HEA300 | 4.5 | 213.29 | 208.31 | −2.3 | |

| 46 | 6 | 217.99 | 213.85 | −1.9 | |||

| 47 | 7.5 | 221.14 | 217.75 | −1.5 | |||

| 48 | 9 | 223.50 | 220.63 | −1.3 | |||

References

- Masarira, A. The Effect of Joints on the Stability Behaviour of Steel Frame Beams. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2002, 58, 1375–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; He, W.J.; Zhan, W.; Li, B.H. Full Beam Formulation for the Lateral Torsional Buckling Analysis of Elastic Frames by Considering the Structural Detail of Beam-to-Column Joint. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 183, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczubiej, G.; Cichoń, C. Global static and stability analysis of thin-walled structures with open cross-section using FE shell-beam models. Thin-Walled Struct. 2014, 82, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, S.; Rasmussen, K.J.R. A model for warping transmission through joints of steel frames. Thin-Walled Struct. 2014, 82, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimidis, S.; Deodatis, G.; Kontoroupi, T.; Ettouney, M. Loss-of-stability induced progressive collapse modes in 3D steel moment frames. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2015, 11, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giżejowski, M.; Szczerba, R.; Gajewski, M.; Stachura, Z. Resistance assessment of steel planar frame fabricated from slender web plate girders. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Archit. 2015, XXXII, 73–92. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicki, K.; Szewczyk, P.; Paczkowski, W.; Wróblewski, T.; Skibicki, S. Torsional Stability Assessment of Columns Using Photometry and FEM. Buildings 2020, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalochairetis, K.E.; Gantes, C.J. Elastic Buckling Load of Multi-Story Frames Consisting of Timoshenko Members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2012, 71, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystosik, P. On Stability of Unbraced Steel Frames with Semi-Rigid Joints. Ce/Pap. Proc. Civ. Eng. 2017, 1, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, R.; Szychowski, A.; Vican, J. Elastic Critical Resistance of the Simple Beam Grillage Resulting from the Lateral Torsional Buckling Condition: FEM Modelling and Analytical Considerations. Materials 2023, 16, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-M.; Hwang, S.-Y.; Hwang, M.-O.; Choi, B.H. Inelastic Buckling of Torsionally Braced I-Girders under Uniform Bending: I. Numerical Parametric Studies. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2010, 66, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yura, J.; Helwig, T.; Herman, R.; Zhou, C. Global Lateral Buckling of I-Shaped Girder Systems. J. Struct. Eng. 2008, 134, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, B.; Burdette, E.G. Effects of Cross-Frame on Stability of Double I-Girder System under Erection. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2152, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rageh, A.; Sun, C.S.; Linzell, D.G.; Puckett, J.A. Dataset for large-scale, lateral-torsional buckling tests of continuous beams in a grillage system. Data Brief 2022, 44, 108532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabojszcza, P.; Radoń-Kobus, K.; Kossakowski, P.G. Verification of Numerical Models of Steel Bar Coverings Using Experimental Tests—Preliminary Study. Metals 2024, 14, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, L.; Luo, B.; Ruan, Y. A Comparative Study on the Stability Performance of the Suspen-Dome, Conventional Cable Dome, and Ridge-Beam Cable Dome. Buildings 2023, 13, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoń, U.; Zabojszcza, P.; Sokol, M. The Influence of Dome Geometry on the Results of Modal and Buckling Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhen, C.; Li, W.; Ma, C. A Novel Stability Analysis Method of Single-Layer Ribbed Reticulated Shells with Roof Plates. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 200, 111902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijak, R.; Brzezińska, K. Reduction in the Critical Moment for Lateral Torsional Buckling of Coped Beams. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 797, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Lin, C.; Sun, D.; Lu, S.; Wen, T. Numerical analysis and design methodology for steel frames with fuse system. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.-L.; Trahair, N.S. Distortion and warping at beam supports. J. Struct. Eng. 2000, 126, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuteir, B.W.; Labed, A. Study of the Elastic and Inelastic Resistance to Lateral Torsional Buckling of Steel Semi-Compact I-Sections. Numer. Methods Civ. Eng. 2023, 8, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1993-1-1; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 1993-1-8; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-8: Design of Joints. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Basaglia, C.; Camotim, D.; Silvestre, N. Torsion Warping Transmission at Thin-Walled Frame Joints: Kinematics, Modelling and Structural Response. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2012, 69, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Mohareb, M. Finite-Element Formulation for the Lateral Torsional Buckling of Plane Frames. J. Eng. Mech. 2013, 139, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraei, A.; Mohareb, M. Lateral Torsional Buckling Analysis of Moment Resisting Plane Frames. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 134, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, S.P.; Gere, J.M. Theory of Elastic Stability, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Larue, B.; Khelil, A.; Gueury, M. Elastic Flexural–Torsional Buckling of Steel Beams with Rigid and Continuous Lateral Restraints. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2007, 63, 692–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trahair, N. Torsion Equations for Lateral Buckling. Eng. Struct. 2016, 128, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamani, M.A.M.; Roberts, E.R. Energy equations for elastic flexural–torsional buckling analysis of plane structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2009, 47, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, S.; Kerdal, D.E.; Jaspart, J.P. Effect of end connection restraints on the stability of steel beams in bending. Adv. Steel Constr. 2008, 4, 243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, R.; Szychowski, A. Lateral Torsional Buckling of Steel Beams Elastically Restrained at the Support Nodes. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebastard, M.; Couchaux, M.; Santana, M.; Bureau, A.; Hjiaj, M. Elastic Lateral-Torsional Buckling of Beams with Warping Restraints at Supports. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 197, 107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, R.; Szychowski, A. The Effect of Steel Beam Elastic Restraint on the Critical Moment of Lateral Torsional Buckling. Materials 2022, 15, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Ho, G.W.M.; Liu, S.-W.; Chen, L.; Chan, S.-L. Advanced line-finite-element for lateral-torsional buckling of beams with torsion and warping restraints. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 224, 109103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, J. Influence of Constructional Details on the Load Carrying Capacity of Beams. Eng. Struct. 1996, 18, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giżejowski, M. Lateral buckling of steel beams with limited rotation ability at supports. Inżynieria Bud. 2001, 10, 589–594. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Živner, T.J. The Influence of Constructional Detail to Lateral-Torsional Buckling of Beams. Procedia Eng. 2012, 40, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, R.; Szychowski, A. Lateral-Torsional Buckling of Beams Elastically Restrained against Warping at Supports. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2015, LXI, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czubacki, R.; Lewiński, T. Application of the Rayleigh Quotient Method in the Analysis of Stability of Straight Elastic Bars. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2024, LXX, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, R.; Szychowski, A. A New Formula for the Critical Moment of Lateral Torsional Buckling of Beams Elastically Restrained at the Support Nodes. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogucki, W.; Żyburtowicz, M. Tables for Designing Metal Structures, 7th ed.; Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Gotluru, B.P.; Schafer, B.W.; Pekoz, T. Torsion in Thin-Walled Cold-Formed Steel Beams. Thin-Walled Struct. 2000, 37, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Życzkowski, M. Technical Mechanics. Strength of Structural Members; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1988. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szychowski, A. Buckling of the Stiffened Flange of the Thin-Walled Member at Longitudinal Stress Variation. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2015, LXI, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, H. Analysis of Continuous Frames by Distributing Fixed-End Moments. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1932, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaqus 2016. In Abaqus/CAE User’s Guide; PDF Documentation; Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corp.: Johnston, RI, USA, 2015; Available online: http://130.149.89.49:2080/v2016/pdf_books/CAE.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Sahraei, A.; Mohareb, M. Upper and Lower Bound Solutions for Lateral-Torsional Buckling of Doubly Symmetric Members. Thin-Walled Struct. 2016, 102, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LTBeamN Software, version 2.0.1; CTICM: Saint-Aubin, France. Available online: https://www.cticm.com/logiciel/ltbeamn/ (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Giżejowski, M.; Ziółko, J. General Construction. Volume 5. Steel Structures of Buildings. Eurocode Design with Calculation Examples; Arkady: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).