PDCA-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in the Industrial Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

2.2. Methodological Proposal for Energy Assessment

2.3. Implementation of the Proposed Model

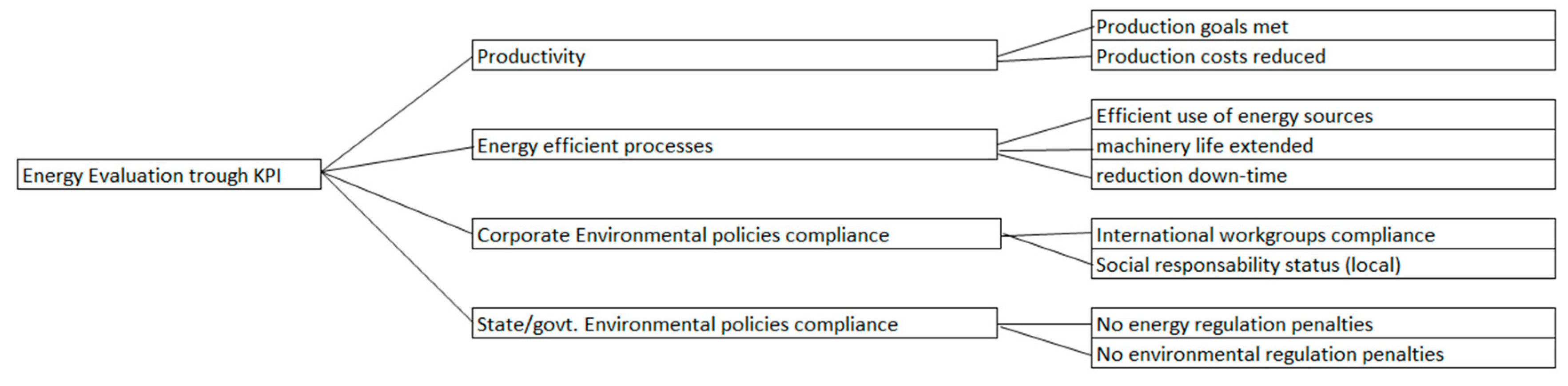

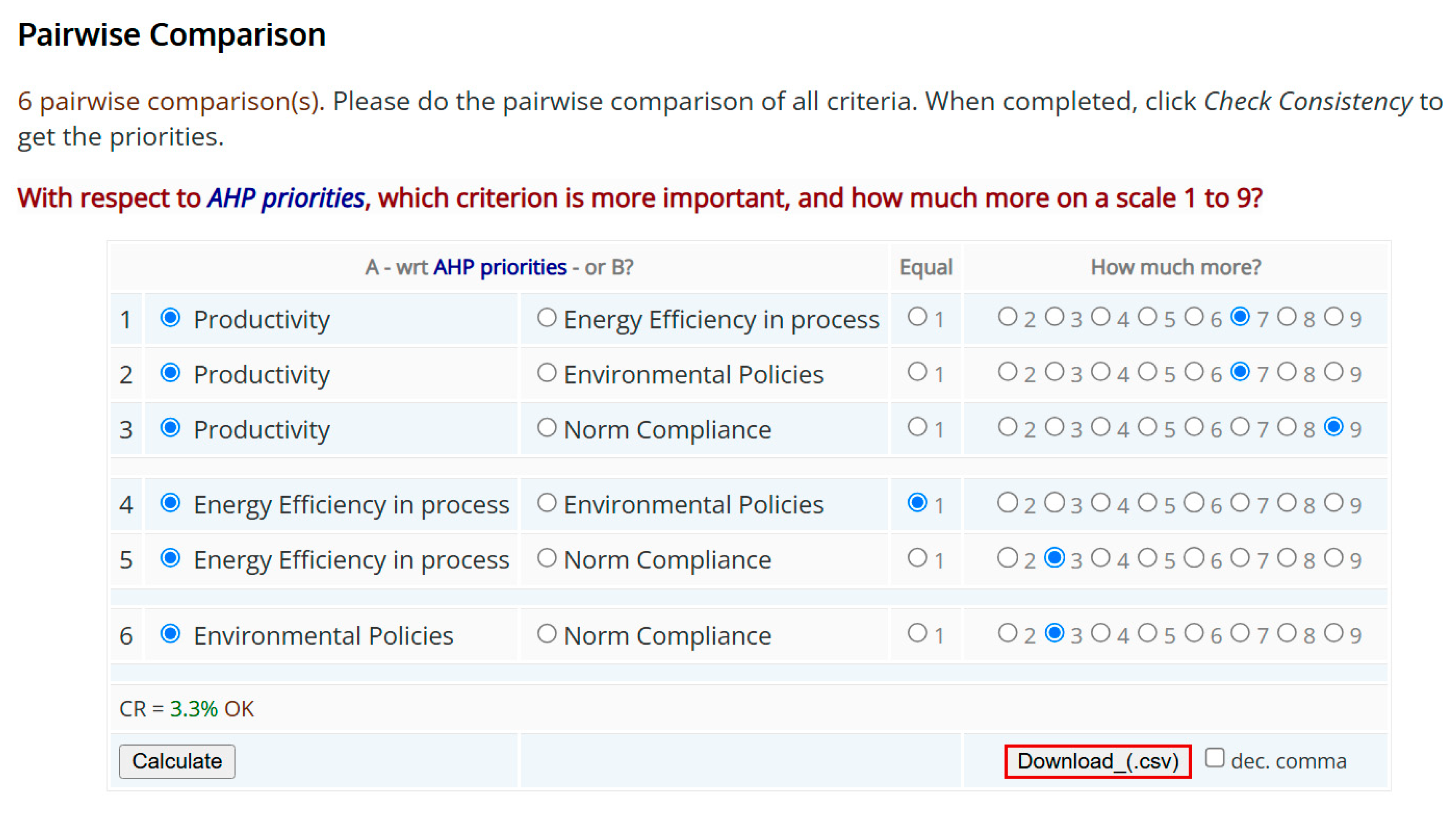

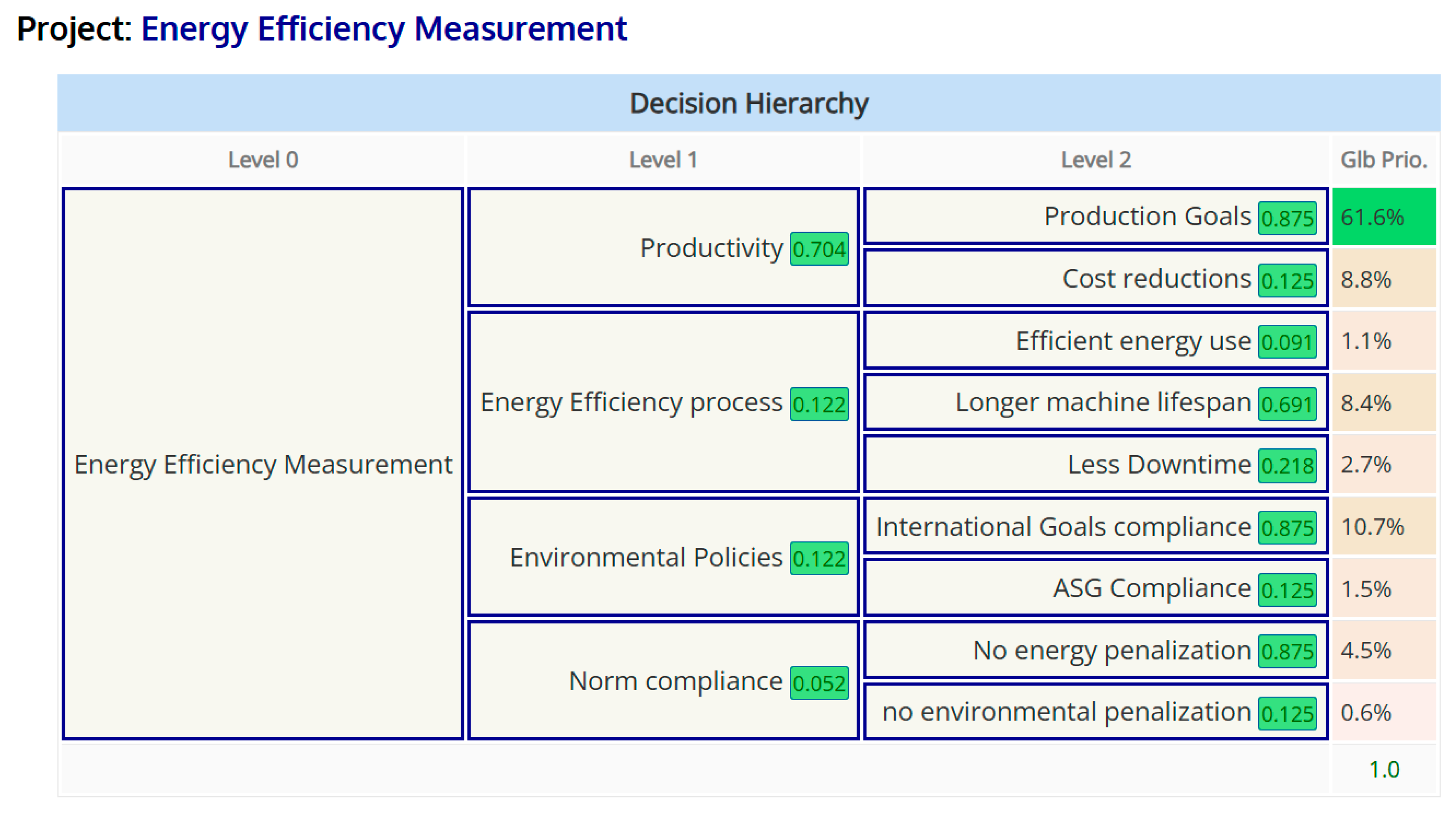

2.3.1. Stage I: Profiling and Planning

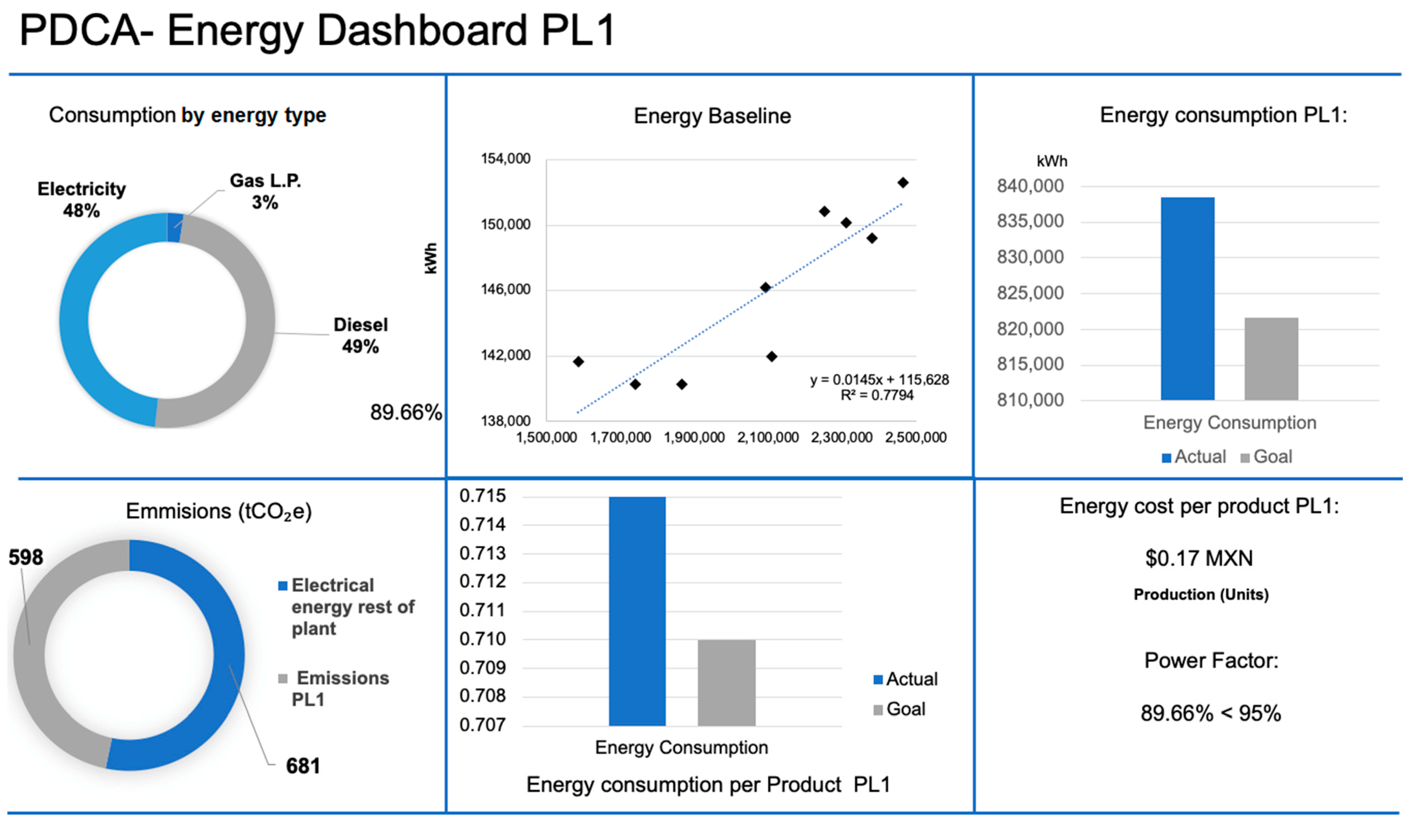

2.3.2. Stage II: Implementation

2.3.3. Stage III: Maintenance and Observation

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| AHP-OS | AHP Online System |

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| BSC | Balanced Scorecard |

| CFE | Federal Electricity Commission (Comisión Federal de Electricidad) |

| CRE | Energy Regulatory Commission (Comisión Reguladora de Energía) |

| EHS | Environmental/Health and Safety |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| KPIs | Key Performance Indicators |

| KPIEn | Key Performance Indicators for Energy |

| L | Litre |

| MXN | Currency code for the Mexican peso |

| M2KPIEn | Measurement Methodology with Energy-based KPI |

| PDCA | Plan-Do-Check-Act |

| PL1 | Power Lock Line 1 |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SEC | Specific Energy Consumption |

| SEU | Significant Energy Uses |

| tCO2 | Tonnes of carbon dioxide |

| tCO2e | Tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent |

| LP gas | Liquefied petroleum gas |

References

- Serna-Machado, C.A. Gestión energética empresarial una metodología para la reducción de consumo de energía. Prod. + Limpia 2010, 5, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ezici, B.; Eğilmez, G.; Gedik, R. Assessing the Eco-Efficiency of U.S. Manufacturing Industries with a Focus on Renewable vs. Non-Renewable Energy Use: An Integrated Time Series MRIO and DEA Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lin, B. Impact of Foreign Trade on Energy Efficiency in China’s Textile Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Sola, A.V.; de Paula-Xavier, A.A. Organizational Human Factors as Barriers to Energy Efficiency in Electrical Motors Systems in Industry. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 5784–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.A.; Mattos, C.R.; Balestieri, J.A.P. Energy Education: Breaking up the Rational Energy Use Barriers. Energy Policy 2004, 32, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narciso, D.A.C.; Martins, F.G. Application of Machine Learning Tools for Energy Efficiency in Industry: A Review. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.; Nasooti, M. A Decision Support Tool for Cement Industry to Select Energy Efficiency Measures. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 28, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguia, N.; Vargas-Betancourt, N.; Esquer, J.; Giannetti, B.F.; Liu, G.; Velazquez, L.E. Driving Competitive Advantage through Energy Efficiency in Mexican Maquiladoras. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3379–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, G.; Barletta, I.; Stahl, B.; Taisch, M. Energy Management in Production: A Novel Method to Develop Key Performance Indicators for Improving Energy Efficiency. Appl. Energy 2015, 149, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Li, W.; Thiede, S.; Kornfeld, B.; Kara, S.; Herrmann, C. Implementing Key Performance Indicators for Energy Efficiency in Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2016, 57, 758–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.; Thollander, P.; Andrei, M.; Karlsson, M. Specific Energy Consumption/Use (SEC) in Energy Management for Improving Energy Efficiency in Industry: Meaning, Usage and Differences. Energies 2019, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Moya, R. Guía Para Realizar Diagnósticos Energéticos y Evaluar Medidas de Ahorro En Equipos de Bombeo de Agua de Organismos Operadores de Agua Potable. 2014. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/268483/Gu_a_para_realizar_diagn_sticos_energ_ticos_y_evaluar_medidas_de_ahorro.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Samitier, L. ISO 50001 en la Industria de Procesos. 2019. Available online: https://es.linkedin.com/pulse/iso-50001-en-la-industria-de-procesos-luciano-samitier (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Andersson, E.; Thollander, P. Key Performance Indicators for Energy Management in the Swedish Pulp and Paper Industry. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, J.C.C.; Caicedo, O.F.P.; Oqueña, E.C.Q.; Medina, J.R.V.; Figueroa, E.D.L. El MGIE, un modelo de gestión energética para el sector productivo nacional. El Hombre Máquina 2008, 6, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.S.; Medeiros, C.F.; Vieira, R.K. Cleaner Production and PDCA Cycle: Practical Application for Reducing the Cans Loss Index in a Beverage Company. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putarungsi, P. Development of Conceptual Framework and Indicators for Assessment of Power Development Fund in Thailand. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 41, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, Z.K.; Szádoczki, Z.; Bozóki, S.; Stănciulescu, G.C.; Szabo, D. An Analytic Hierarchy Process Approach for Prioritisation of Strategic Objectives of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylan, O.; Alamoudi, R.; Kabli, M.; AlJifri, A.; Ramzi, F.; Herrera-Viedma, E. Assessment of Energy Systems Using Extended Fuzzy AHP, Fuzzy VIKOR, and TOPSIS Approaches to Manage Non-Cooperative Opinions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Niu, D.; Liang, Y. Sustainability Evaluation of Renewable Energy Incubators Using Interval Type-II Fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS with MEA-MLSSVM. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Algarin, C.A.; Polo Llanos, A.; Ospino Castro, A.J. An Analytic Hierarchy Process Based Approach for Evaluating Renewable Energy Sources. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2017, 7, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, B. Key Performance Indicators, 1st ed.; Financial Times Press: Harlow, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-273-75011-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Y.-C.; Lee, D.; Lin, C.-F.; Chang, C.-Y. The Energy Savings and Environmental Benefits for Small and Medium Enterprises by Cloud Energy Management System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7619-2608-5. [Google Scholar]

- May, G.; Stahl, B.; Taisch, M.; Kiritsis, D. Energy Management in Manufacturing: From Literature Review to a Conceptual Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1464–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, G.; Llano, E.; Globisch, J.; Durand, A.; Hettesheimer, T.; Alcalde, E. Increasing Energy Efficiency in the Food and Beverage Industry: A Human-Centered Design Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepel, K.D. Implementation of an Online Software Tool for the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP-OS). Int. J. Anal. Hierarchy Process 2018, 10, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luis-Ruiz, J.M.; Salas-Menocal, B.R.; Pereda-García, R.; Pérez-Álvarez, R.; Sedano-Cibrián, J.; Ruiz-Fernández, C. Optimal Location of Solar Photovoltaic Plants Using Geographic Information Systems and Multi-Criteria Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjono, H.; Seik, O.; Defan, J.; Simamora, B.H. Analytical Hierarchy Process (Ahp) In Manufacturing And Non-Manufacturing Industries: A Systematic Literature Review. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 158–170. [Google Scholar]

- Cacal, J.C.; Taboada, E.B.; Mehboob, M.S. Strategic Implementation of Integrated Water Resource Management in Selected Areas of Palawan: SWOT-AHP Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Bose, D. Principles of Management and Administration, 2nd ed.; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.: Delhi, India, 2012; ISBN 978-81-203-4581-2. [Google Scholar]

- SEMARNAT. Factor de emisión del sistema eléctrico nacional. 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/981194/aviso_fesen_2024.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Gobierno de México. Factores de Emision. 2015. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/235891/FACTORES_DE_EMISION_2015.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- The Investor Confidence Project. Project Development Specification—Industry and Energy Supply. 2018. Available online: https://ee-ip.org/fileadmin/user_upload/DOCUMENTS/Content/ICP_PDS_INDUSTRY_2018_ENG.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- The Australasian Energy Performance Contracting Association. Best Practice Guide to Measurement and Verification of Energy Savings: A Companion Document to “A Best Practice Guide to Energy Performance Contracts”; Australasian Energy Performance Contracting Association: Castle Hill, NSW, Australia, 2004; ISBN 0-646-44370-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. M&V Guidelines: Measurement and Verification for Performance-Based Contracts Version 5.0. 2024. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2024-10/mv_guide_5_0.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- AP Automatización. Ajuste en las Tarifas Eléctricas Y Cambios en el Factor de Potencia. 2024. Available online: https://ap-automatizacion.com/noticias/cambios-en-el-factor-de-potencia/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- AP Automatización. ¿Recibiste un cargo por bajo Factor de Potencia en el recibo CFE? 2024. Available online: https://ap-automatizacion.com/noticias/recibiste-un-cargo-por-bajo-factor-de-potencia-en-tu-factura-de-cfe/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Executive Summary—Energy Management for Industry—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-management-for-industry/executive-summary (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Energy Efficiency 2017; Energy Efficiency; OECD: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 978-92-64-28423-4. [Google Scholar]

| Data Required | Area/Provider | Document |

|---|---|---|

| a. Overall energy consumption | Facilities/EHS | Electrical Energy billing Gas provider bill Diesel provider bill |

| b. Weekly production | Planning/production | Weekly production goals |

| c. Yearly production forecast | Management/planning | Detailed production plan |

| d. Machine inventory | Maintenance/EHS | Detailed machine inventory |

| e. Weekly energy consumption | Maintenance/EHS | Electrical energy monitoring per consumption area (weekly) |

| Scale | Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equally important | Both criteria contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 | Moderate importance | Experience and judgement somewhat favour one criterion over the other |

| 5 | High importance | Experience and judgement strongly favour one criterion over the other |

| 7 | Very high importance | One criterion is very strongly favoured over the other. In practice, its dominance can be demonstrated |

| 9 | Extreme importance | The evidence strongly favours one factor over the other |

| 2, 4, 6 and 8 | Intermediate values between the above when it is necessary to qualify | |

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria |

|---|---|

| Cost savings | Cost/production Energy cost/production Savings through energy measures |

| Goals and corporate priorities met | Global consumption share CO2 emissions mitigation Energy consumption reduction |

| Process | Power factor and quality Down-time reduction Production loss due to maintenance |

| Energy Efficiency | Energy Baseline Production/energy Energy used by production unit |

| Group | ID | KPI | Process | Global | Priority | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2% Energy intensity reduction | Energy states | E0 | Valuable energy Consumption | ✓ | 25% | |

| E1 | Net production Energy | ✓ | 0% | |||

| E2 | Gross production Energy | ✓ | 0% | |||

| E3 | Net Energy usage | ✓ | 25% | |||

| E4 | Gross Energy usage | ✓ | 0% | |||

| E5 | Start-up Energy use | ✓ | 0% | |||

| E6 | Theoretical production time energy | ✓ | 0% | |||

| Energetic Typology | T1 | Production Energy Indicators | ✓ | 25% | ||

| T2 | Overall economic indicators | ✓ | 14% | |||

| T3 | Costs of EE and evolution of EE | ✓ | 25% | |||

| T4 | Energy Savings | ✓ | 14% | |||

| T5 | Overall energy costs | ✓ | 25% | |||

| Specific energy consumption | SEC | Specific Energy consumption | ✓ | 0% | ||

| SECx | Specific Energy consumption per product | ✓ | 25% | |||

| SECagg | Specific Energy consumption per product group | ✓ | 0% | |||

| SECpr | Specific primary Energy consumption per product | ✓ | 0% | |||

| Energy Indicators | P.F | Power Factor | ✓ | 14% | ||

| Desb. | Electric Unbalance | ✓ | 14% | |||

| THD | Total Harmonic Distortion in line | ✓ | 14% | |||

| EnBL | Energy Baseline | ✓ | 12% | |||

| Frec. | Line Frequency | ✓ | 14% | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vargas-Gurrola, L.; Aguilar-Virgen, Q.; Balderas-López, S.; Taboada-González, P. PDCA-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in the Industrial Sector. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12530. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312530

Vargas-Gurrola L, Aguilar-Virgen Q, Balderas-López S, Taboada-González P. PDCA-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in the Industrial Sector. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12530. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312530

Chicago/Turabian StyleVargas-Gurrola, Luis, Quetzalli Aguilar-Virgen, Silvia Balderas-López, and Paul Taboada-González. 2025. "PDCA-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in the Industrial Sector" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12530. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312530

APA StyleVargas-Gurrola, L., Aguilar-Virgen, Q., Balderas-López, S., & Taboada-González, P. (2025). PDCA-Based Methodology for the Evaluation of Energy Efficiency in the Industrial Sector. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12530. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312530