Abstract

Radiation therapy is one of the methods of cancer treatment, using ionizing radiation, which can lead to many negative skin changes. Therefore, its proper care is critical. This provided the impetus for an attempt to assess oncology patients’ knowledge of skin care during and after radiation therapy treatment. Methods: An anonymous and voluntary questionnaire survey was conducted among 100 patients during and after radiotherapy treatment at the Bohaterów Radomskiego Czerwca 76 Radom Oncology Center in Poland. The chi-square independence test was used to examine the independence of certain features. In case it was not possible to verify the hypothesis of the independence of features without the Yates correction, the chi-square independence test, with this correction, was used. Results: Fifty-three men and 47 women were included in the study, with prostate cancer (39%) and breast cancer (35%) being the most common, respectively. Most of the respondents were aged 56+. 67% of respondents indicated having negative skin lesions during or after radiation therapy treatment, which occurred most often in the areas of the head and neck (32%), chest (10%), and upper extremities (9%). 57% of respondents did not visit medical personnel or a cosmetologist for skin care. In contrast, 24% indicated a belief in a high level of knowledge about skin care during and after radiation therapy treatment. Conclusions: Analysis of the obtained results may lead to further development of certain issues in medicine. They are, among others, the need to increase awareness of society that has contact with oncological therapy on various actions which impact the maintenance of good skin condition, improvement of its appearance, and alleviation of symptoms which appear during or after radiotherapy.

1. Introduction

Fighting neoplasms is a long process that can combine several methods or a separate method of treatment for the fastest possible recovery. One of the treatment methods chosen for this purpose is radiotherapy, which uses ionizing radiation. Radiotherapy is used for many types of neoplasms and at various stages of treatment. The doses used are selected by a specialist to destroy or damage cancer cells. This minimizes the size of the tumor or makes it possible to remove the entire lesion while preserving healthy cells in the surrounding tissues [1,2,3,4].

Advances in oncology techniques are associated with continuous improvements in cancer treatment methods, but there is still no ideal method that would be able to combat neoplasms without causing any of the undesirable side effects. In radiotherapy, ionising radiation can cause many visible changes to the skin, which can cause discomfort to the patient. These changes are caused by several factors, such as the dose or location exposed to radiation, or the interval at which a given dose of radiation is administered, i.e., the fractionation method. Skin damage occurs in almost 95% of patients undergoing this treatment method [5]. All side effects are divided into two basic types: early, referred to as acute (usually manifest themselves quite quickly, often during radiotherapy or after its completion for three to six months), and late (develop slowly and are noticeable after 6 months or even several years).

The main tasks of skin care after radiotherapy include alleviating the symptoms of skin radiation, starting with proper hygiene and ending with proper protection. Any skin care products used by the patient should be consulted with a specialist before use, and the best solution will be to apply specially prepared products for post-radiation skin. The ingredients of cosmetics recommended for skin care after radiotherapy include: sodium hyaluronate, urea, allantoin, silver ions, beeswax, Shea butter, soybean oil, olive oil, squalane, d-panthenol, folic acid, aloe, Japanese knotweed extract, milk thistle fruit extract, coenzyme Q, ectoine, probiotics, ceramides, witch hazel, chamomile extract, etc. [6,7,8,9]. Among others, Villegas-Becerril et al. in their work based on clinical studies confirmed the efficacy of plant extracts and essential oils in alleviating radiation-induced dermatitis (RD) in patients undergoing radiotherapy [9]. Depending on the health condition and relative contraindications, there is a chance to perform some treatments that meet the needs of clients, although their number is significantly limited due to the health condition [10,11,12].

The most important indicators of typical skin toxicity during and after radiotherapy include: dry exfoliation of the epidermis with generalised erythema, severe erythema or patchy, moist exfoliation of the epidermis, extensive moist exfoliation outside skin folds, ulceration, bleeding and skin necrosis, chronic ulcerations and wounds, fibrosis, telangiectasia, secondary skin cancers, and radiation keratosis [13,14].

Clinical decisions regarding skin care in radiation dermatitis vary widely. For example, Finkelstein et al. [15] conducted a comprehensive review of international guidelines (MASCC—Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer, BCCA—British Columbia Cancer Agency, CCMB—Cancer Care Manitoba, ONS—Oncology Nursing Society, SCoR—Society and College of Radiographers, and ISNCC—International Society of Nurses in Cancer Care) on the prevention and treatment of skin lesions, as well as on standard hygiene and care issues. There is considerable variability in the outcomes and treatment methods selected for measurement. They emphasised that it is necessary to publish and implement new guidelines to optimise patient outcomes.

Similarly, Behroozian et al. [16] stated that despite the significant amount of available literature, scientific evidence confirming the effectiveness of interventions in the prevention and treatment of skin changes after radiotherapy is very diverse, most likely due to differences in study design, assessed outcomes, type of intervention, and patient population between studies. According to the authors, skin changes most often appear within 90 days of the start of treatment. In contrast, chronic skin changes, telangiectasia, fibrosis, etc., may appear months or even years after radiotherapy [17].

Based on a review of the literature, it was found that there are no clear standards or guidelines for the prevention and treatment of radiation dermatitis. Furthermore, there is a lack of comprehensive data on the subjective assessment of symptom severity in patients, the most common methods of care, and effective prevention and education in this area. Therefore, there is a need to conduct surveys using tools that take into account the patients’ perspective. This will make it possible to identify the key problems and preferences of this group of patients.

This prompted an attempt to determine the state of knowledge and behaviour of patients regarding skin changes during and after radiotherapy treatment. The results of the survey presented in the article may be used in the future to prepare an educational package and a process for referring patients to the clinic.

The survey aimed to assess patients’ knowledge and behavior regarding skin changes during and after radiotherapy treatment.

2. Research Methods and Tools

The study used a pilot method with a questionnaire containing 23 questions. The questionnaire consisted of a personal data sheet concerning gender, age, place of residence, education, and professional status. The rest of the survey contained original questions concerning, among other things: the stage of radiotherapy treatment, the type of cancer, the importance of skin care, how information about skin care is obtained, the frequency of visits to a cosmetologist or medical staff, knowledge about side effects, types of skin changes during or after radiotherapy, knowledge about cosmetic procedures that can be used in this group of patients, the time after which respondents noticed skin changes, the location of skin changes, and knowledge of active ingredients that are worth introducing into skin care. Based on the survey results, the following were presented:

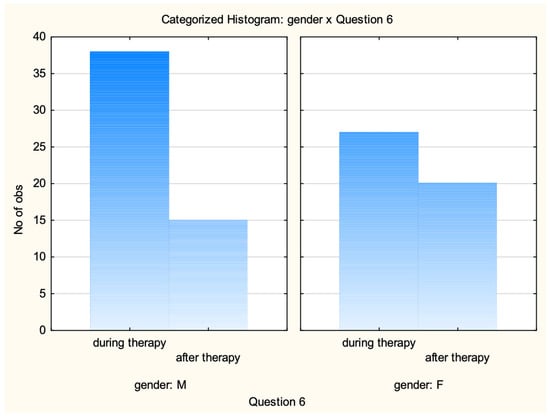

- Characteristics of the study group in terms of gender and stage of treatment, using the chi-square independence test;

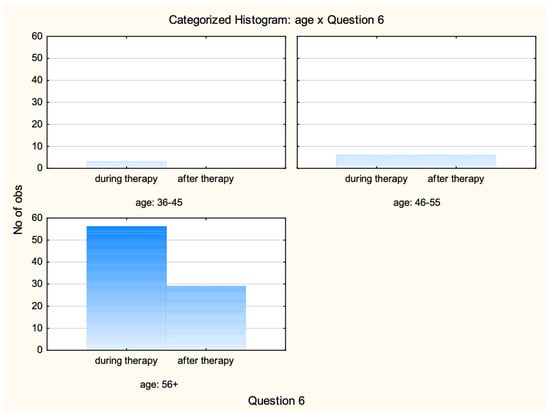

- Characteristics of the study group in terms of age and stage of treatment, using categorized histograms;

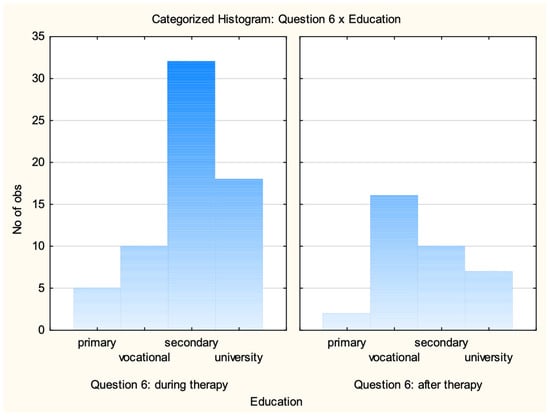

- Characteristics of the study group in terms of stage of education and treatment, using the chi-square test with Yates’ correction. Since p = 0.01338 < 0.05, the results indicate a relationship between education and the stage of treatment;

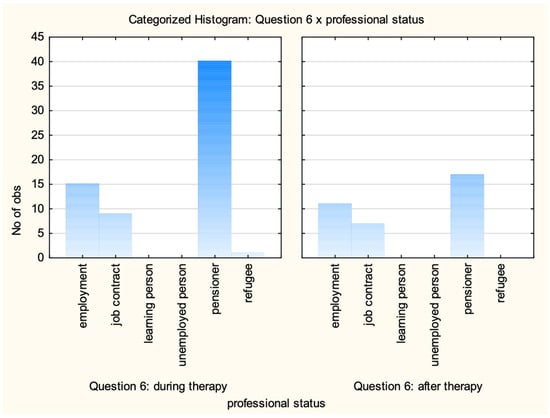

- The number of people undergoing and having undergone radiotherapy, depending on their professional status, using categorized histograms and frequency tables;

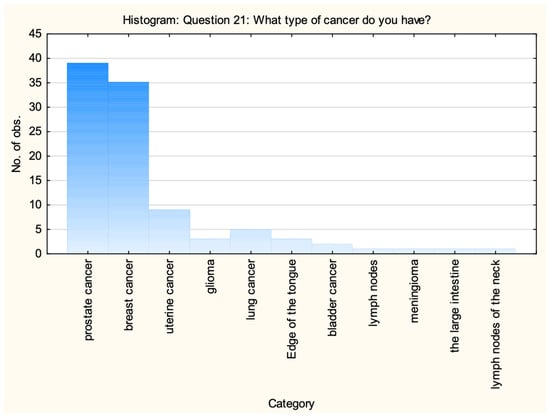

- Types of cancer in the study group, using a histogram;

- Assessment of the importance of skin care in correlation with gender, place of residence, age, and education, using frequency tables;

- Assessment of how information on skin care is obtained, using frequency tables;

- Assessment of the frequency of visits to a cosmetologist or medical staff for skin care, correlating with gender, age, place of residence, and education, using frequency tables;

- Assessment of knowledge about adverse effects that may occur during and after radiotherapy, using frequency tables;

- Assessment of types of skin changes during or after radiotherapy, using frequency tables;

- Assessment of respondents’ knowledge of cosmetic treatments that can be used during or after radiotherapy, using frequency tables;

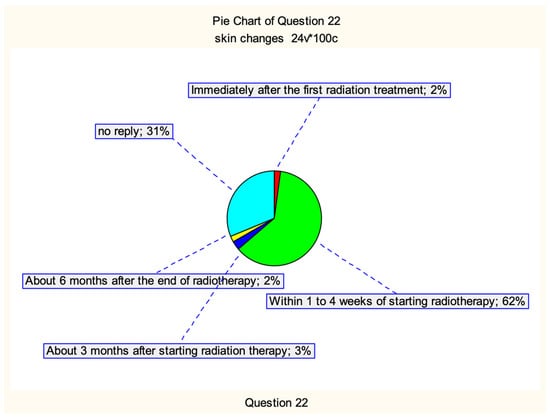

- Time after which respondents noticed skin changes related to radiotherapy, using a pie chart for qualitative data;

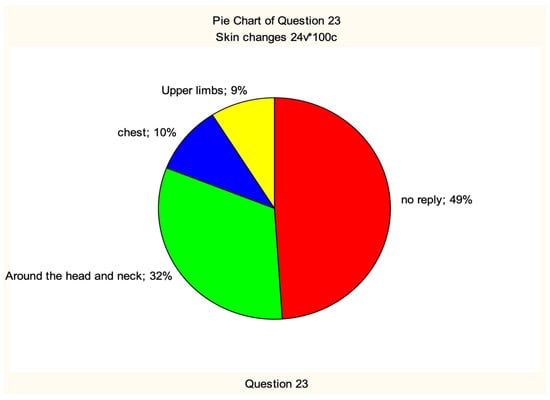

- Location of skin changes, depending on gender, using a pie chart for qualitative data

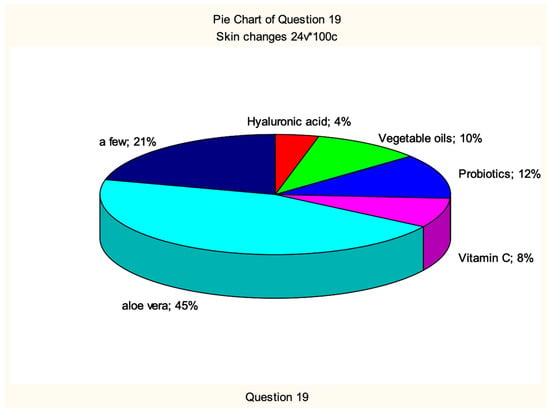

- Ingredients that are worth introducing into skin care, depending on gender, using a pie chart for qualitative data.

The study was anonymous and voluntary and was conducted among 100 adults aged 36 to 56+, 53 men and 47 women with cancer, treated with one of the methods, i.e., radiotherapy. The study was conducted at the Radom Oncology Center named after the Heroes of Radom June 76‘ (Radom, Masovian Province, Poland). It was a single-center project. The study was conducted in the first quarter of 2024. Eligibility criteria—the study group consisted of people with confirmed cancer, undergoing or having undergone radiotherapy, who voluntarily agreed to participate in the survey. At the beginning of the survey, there was information about the patient’s informed consent to participate in the study. Each person who agreed to participate completed the survey. Lack of consent meant that the patient did not complete the survey.

At any time, without giving a reason, respondents could withdraw their consent to participate in the rest of the study. Respondents were informed that the data collected for the study would not contain any personal data (e.g., name, address, social security number)—the survey was anonymous and would be stored in a secure location, accessible only to the authors of the study.

For all questions, the denominator was 100%, except for questions 10 (34%), 22 (70%), and 23 (70%). Question 10 was not analyzed in the article due to the small number of responses. However, it is expected that respondents did not answer questions 22 and 23 in full because they were the last questions, and respondents may have been tired.

The doses used in individual locations were as follows:

- Prostate cancer 50–70.2 Grey (Gy), fractional dose 2–2.6 Gy;

- Breast cancer/chest 40.05–53 Gy, fractional dose 2.5–2.67 Gy;

- Uterine cancer/pelvis 45–50.4 Gy, fractional dose 1.8–2 Gy;

- Glioma 40.05–60 Gy, fractional dose 2–2.67 Gy;

- Lung cancer 55–66 Gy, fractional dose 2–2.8 Gy;

- Bladder cancer 55–64 Gy, fractional dose 2–2.75 Gy;

- Lymph nodes 50–70 Gy, fractional dose 2–2.6 Gy;

- Rectum/large intestine 25–50.4 Gy, fractional dose 1.8–5 Gy;

- Cervical lymph nodes 50–66 Gy, fractional dose 2 Gy.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistica 14.0 software, English version 64-bit Statistica 14 ENG 64bit.

Descriptive statistical methods: diagrams, tables, and graphs were used for the development of statistical studies. The chi-square independence test was used to examine the independence of certain features. In case it was not possible to verify the hypothesis of the independence of features without the Yates correction, the chi-square independence test, with this correction, was used.

3. Survey Results

Characteristics of the Study Group

The study included 38 men and 27 women undergoing radiotherapy, and 15 men and 20 women after completing the treatment process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the research group by gender and stage of treatment.

The chi-square test of independence was used, taking into account the data from Figure 1 to check whether the stage of treatment depended on gender (Table 1). It was found that the stage of treatment at which the respondent was did not depend on gender.

Table 1.

Chi-square test results.

The data presented in Table 1 show that the p-value for the chi-square test of independence of characteristics p = 0.1359 > 0.05, so the hypothesis H0 should not be rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis H1—the stage of treatment at which the respondent is did not depend on gender.

Figure 2 shows the number of people during and after treatment depending on age.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the study group by age and treatment stage.

The above data are presented in the table of counts Table 2.

Table 2.

Table of counts (study group by age and treatment stage).

It turned out that the vast majority of people taking part in the study are women and men over the age of 56 years. 56 and 29 people, respectively. There were only three respondents under the age of 46 years, and they were all women undergoing treatment. There were 12 people in the age group 46–55, six of each sex.

Figure 3 presents the division of people during and after treatment depending on education.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the research group according to education and treatment stage.

Considering the results obtained (Figure 3) (since we only have a sample size of 2 in one case—only 2 people with primary education completed treatment), the chi-square test of independence of characteristics with Yates’ correction was used, based on which it was concluded that there is a relationship between education and the stage of treatment. The test results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the chi-square test with Yates correction.

The number of people undergoing and having undergone radiotherapy, depending on their employment status, is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The number of people undergoing and having undergone radiotherapy depending on their employment status.

It turns out that as many as 40 people undergoing treatment are pensioners. The highest number of pensioners is also found in the group of people who have completed radiotherapy (17). This may be because retired people have more time to take care of their health, and thanks to check-ups, they have the opportunity to be diagnosed faster and therefore to start the treatment process faster.

Considering the specific type of cancer (Figure 5), it was observed that among the examined, there were 39 men diagnosed with prostate cancer and 33 women with breast cancer, and nine with uterine body cancer.

Figure 5.

Neoplasm types in the study group.

The remaining people were three men with glioma, five with lung cancer, three with tongue cancer, two with bladder cancer, and one with neck lymph node neoplasm. In the case of women, there were two women with breast cancer, one woman with lymph node neoplasm, another one with meningioma, and one woman with colon cancer.

4. Survey Results on Skin Care During and After Radiotherapy

4.1. Assessment of the Importance of Skin Care

It turned out that both women and men believed that skin care during and after radiotherapy was an important element in improving well-being and quality of life. As many as 41 men and 43 women indicated a ‘yes’ answer. Only two men believed that it was not important, and 10 had no opinion on the subject. In turn, as many as 71 people aged 56+ years considered skin care during and after treatment to be essential. Only 14 people had no opinion on whether skin care was important. Surprisingly, as many as six of them came from cities with more than 500 thousand inhabitants. Residents of rural areas seemed to be more aware of this issue, unanimously indicating a ‘yes’ answer (17 individuals).

The larger the town the respondents came from, the more people had no opinion on the importance of skin care during and after radiotherapy. In turn, only two residents of cities with a population of 50–150 thousand considered skin care not to be important.

It can also be seen that two people with secondary education considered skin care not to be important. This group also included the largest number of people who had no opinion on the question asked.

4.2. Assessment of the Method of Obtaining Information About Skin Care

It turned out that the largest number of people indicated obtaining information from medical personnel (46%). It was certainly provided clearly because as many as 30 of the respondents considered their knowledge to be at an average level. In turn, those who searched for information on the Internet either did not understand the content provided there or were unable to find the information correctly because as many as six people considered their knowledge to be low or zero. In addition, only four people indicated a complete lack of knowledge about skin care during and after radiotherapy, and these were people looking for information on this subject on the Internet.

4.3. Assessment of the Frequency of Visits to a Cosmetologist or Medical Personnel for Skin Care

A very large number of people did not visit a specialist, as many as 57% (38 men and 19 women). Only 15 women and eight men visited a cosmetologist or medical personnel for skin care once a month. Therefore, almost twice as many women as men used the advice of a specialist quite regularly. Three men and 10 women decided to visit a specialist occasionally. These visits were once a year or less often.

Similar conclusions can be drawn by looking at the results generated depending on age. In this case, as many as 57 people taking part in the survey did not visit a cosmetologist or medical personnel for skin care. Most of them were people over 56 years of age. The oldest respondents (21 people) and two people aged 36–45 years visited a specialist once a month.

When comparing the answers to the above question based on place of residence, it can be seen that monthly visits were the domain of people from cities with 150–500 thousand inhabitants. In turn, the largest number, as many as 19 people from large cities (500 thousand+), did not use the advice of a specialist. Also, people with secondary education in the largest percentage (24%) did not go to a cosmetologist.

4.4. Assessment of Knowledge of Side Effects That May Occur During and After Radiotherapy Treatment

The largest number, 16 people, indicated the simultaneous occurrence of dry skin and erythema. Each of these ailments was indicated as occurring individually by seven people in the case of dry skin and three people in the case of erythema. All of the indicated ailments may occur according to seven respondents. As many as 9 people considered that none of the listed side effects could occur during or after radiotherapy treatment.

4.5. Assessment of the Types of Changes in the Skin Condition During or After Radiotherapy Treatment

The largest number of people indicated the occurrence of redness (56 people). At the same time, it was the only symptom in the case of 20 people. In the remaining cases, it was accompanied by other changes, e.g., itching, discolouration, delicate skin, or hypersensitivity to the sun. The only noticeable consequence of radiotherapy for two respondents was hypersensitivity to the sun. 33 people did not have any of the listed symptoms.

4.6. Assessment of the Respondents’ Knowledge of Cosmetic Treatments That Can Be Used During or After Radiotherapy

Respondents in as many as 69 cases considered that the cosmetic treatments listed should not be used. 13 people considered massage as acceptable, and 11—pedicure and manicure. Only three people considered that more than one treatment can be used. These were: massages, enzymatic peelings, manicure, and pedicure. Comparing the results of the responses by gender, we can see that:

- More women than men chose massage (10 F, 3 M) and manicure and pedicure (7 F, 4 M).

- Treatments using an electromagnetic field were chosen by only two men.

- Definitely more men than women considered that none of the presented treatments can be used.

4.7. The Time After Which the Respondents Noticed Skin Changes Related to Radiotherapy Treatment

Figure 6 presents the results of a survey concerning the time after which respondents noticed skin changes associated with radiotherapy treatment.

Figure 6.

The time after which the respondents noticed skin changes related to radiotherapy treatment.

62% of respondents noticed skin changes within 1–4 weeks of starting radiotherapy, and only 2% immediately after the first treatment, and another 2% after six months after the end of the treatment. Symptoms appeared after about 3 months of starting radiotherapy in 3% of respondents. 31% of people did not provide an answer. The most likely reason for this was that they did not experience any skin changes as a result of radiotherapy.

4.8. Location of Skin Changes

The respondents’ answers regarding the question about the location of skin changes are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Location of skin lesions.

Most respondents considered it to be the head and neck area (32%), followed by the chest (10%) and upper limbs (9%). As many as 49 respondents did not provide an answer to the question. There were 30 men and 19 women among them. With regard to gender, we can observe that women complained more often about lesions in the head and neck area (21 people) than men (11 people). Only men (9 respondents) noticed lesions in the upper limbs.

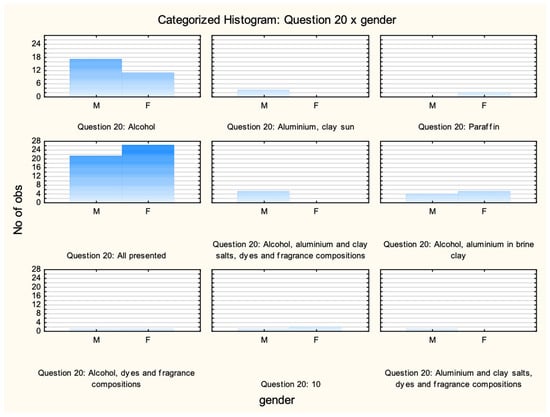

4.9. Ingredients Worth Introducing into Skin Care

Figure 8 presents the respondents’ answers regarding ingredients worth introducing into skin care.

Figure 8.

Ingredients worth introducing to skin care.

Definitely more men than women are in favour of introducing aloe vera to skin care (34 M, 11 F). On the other hand, women were more inclined to choose more ingredients (18 F, 3 M).

The largest number of people considered that all of the ingredients presented should be avoided (almost half—47 people). Alcohol was not good according to 28 respondents, and when including answers in which more sub-items were marked, this number increased to 96. Therefore, patients were aware of the risks resulting from the use of cosmetics based on alcohol (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Ingredients in cosmetics that, according to respondents, should be avoided depending on gender.

5. Discussion

The survey aimed to assess patients’ knowledge and behavior regarding skin changes during and after radiotherapy treatment. Skin lesions may appear as a radiation reaction either early during radiotherapy and up to three months after it, or late after more than three months post radiotherapy.

The results of the survey revealed a low level of knowledge in this area, indicating a need for more effective patient education before the start of therapy. For example, as many as 93% of respondents were unable to correctly identify the symptoms that may occur during and after radiotherapy.

It was found that the stage of treatment of the respondent does not depend on gender. However, there was a relationship between education and the stage of treatment. The fewest people had a primary education both during and after radiotherapy treatment. Most respondents were aged 56+ years. They were most often pensioners. The most common cancer among patients, according to surveys conducted among 100 people, both women and men, was prostate cancer (39%), followed closely by breast cancer (35%). Other neoplasms that appeared among the study group were: uterine body, lymph nodes, lungs, tongue, colon, glioma (3%), bladder, meningioma, and colon cancer. Both women (43%) and men (41%) believed that skin care during and after radiotherapy treatment was an important element in improving well-being and quality of life. As many as 67% of respondents indicated having negative skin changes during or after radiotherapy treatment. They most often appeared in the head and neck area (32%), chest (10%), and upper limbs (9%). In comparison with gender, it was observed that women more often than men had changes in the head and neck area. These were usually redness and delicate thin skin, and itching. According to the studies, these side effects appeared between 1 and 4 weeks after the procedure, which constituted 62% of the answers provided.

Most reactions occurred in the head and neck area within 1–4 weeks after a dose of 10–40 Gy. They were present in up to 32% of patients, gradually increasing in severity. Lesions within the chest wall occurred later after a dose of approximately 30–40 Gy. Skin lesions in the form of an early radiation reaction did not occur during radiotherapy in the abdominal and pelvic regions. The presumed reason for the lack of response in remaining patients was the absence of skin reactions.

When asked about basic information about radiotherapy, such as symptoms that might appear during and after treatment, only 7% of participants indicated all correct answers, which is rather a low result. A significant number indicated fatigue and dry skin as the main problems.

As many as 57% of the respondents, of which 38% men and 19% women, did not visit a cosmetologist or medical personnel for skin care. There was also a lack of knowledge about the cosmetic treatments that can be performed among patients. 68% of the respondents believed that all treatments were excluded during treatment. With regard to cosmetic ingredients, women were more inclined to choose different active ingredients. There are many scientific reports confirming the beneficial effects of cosmetics with active substances dedicated to the skin after radiotherapy e.g., aloe, chamomile, and thyme extracts [18], allantoin [19], and hyaluronic acid [20]. In addition to that, the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) on the prevention and treatment of adverse effects of radiotherapy manifested on the skin indicated the use of olive oil as an active ingredient [21]. 47% of respondents believe that all of the ingredients listed should be avoided, which is true. Only in the case of alcohol as an ingredient of cosmetic products, as many as 96% of respondents believed that it should not be included in the composition of cosmetics for people during or after radiotherapy treatment. It was interesting that 46% of respondents indicated medical personnel as the main way of obtaining information on proper skin care.

Similar conclusions can be found in the literature on the subject. The authors KOrana et al. [22] stated in their work that due to the low level of knowledge among patients, nurses must use a structured approach when conducting educational training on skin care during radiotherapy. In addition, they stated that the creation of instructions for patients after radiotherapy should be included in the general treatment plan in order to minimize undesirable side effects on the skin.

In turn, Kumar et al. [23] stated in their work that educational videos for patients increase their knowledge about radiation therapy and have proven to be very helpful. Before and after the consultation, surveys were conducted to assess the indicators reported by patients on a 5-point Likert scale. Patients in the group using videos reported significantly higher levels of confidence in their knowledge of the side effects of radiation therapy compared to the group without videos.

Many studies in the literature confirm that patients do not always correctly recognize the side effects of radiotherapy, which is reflected in both quantitative and qualitative studies [24]. Surveys conducted in various countries indicate significant variability in patient behavior. Some of them use conventional cosmetics, while others abandon skin care altogether and do not follow any specific recommendations after radiotherapy [25].

Furthermore, the lack of standardized assessment tools and differences in survey methodology make direct comparisons between countries and different centers difficult.

The paper presents cross-sectional research. The limitations of the research presented in the article include: a single-centre design; lack of patient responses to important questions in many cases; lack of clinical assessment of skin inflammation; and lack of RT parameters.

6. Conclusions

Analysing the presented research results, it can be concluded that the level of knowledge of patients about skin changes during and after radiotherapy treatment was not high. Despite many scientific sources, there is still a need for patients’ education about radiotherapy and skin care, which, as patients themselves have stated, is a very important aspect in the life of a sick person. This is particularly important since during this period the skin is even more exposed to injuries, external factors, and other negative changes. Appropriate awareness affects not only its quality but also leads to an increase in the level of its protection, which is so important during and after radiotherapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.; methodology, E.K., J.J., M.O. and M.M.; software, M.M.; validation, M.M.; formal analysis, E.K. and J.J.; investigation, E.K., J.J. and P.M.; resources, E.K., J.J. and P.M.; data curation, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K., M.O. and D.A.; writing—review and editing, E.K., J.J., M.O., D.A. and R.T.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, E.K., J.J. and R.T.; project administration, E.K.; funding acquisition, E.K., J.J., M.O., M.M., D.A. and R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project no. 3608/188/P entitled “Influence of active substances on physicochemical and usable properties of selected cosmetic products used in various disease entities”, funded by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Casimir Pulaski University of Radom (Project title: “Influence of active substances on physicochemical and usable properties of selected cosmetic products used in various disease entities”; Approval code: Resolution No. KB/04/2024; Date of approval: 14 May 2024).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the hospital Radom Oncology Center staff for their invaluable contributions and support throughout the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chargari, C.; Peignaux, K.; Escande, A.; Renard, S.; Lafond, C.; Petit, A.; Haie-Méder, C. Radiotherapy of cervical cancer. Cancer/Radiothérapie 2022, 26, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, C.; Lacas, B.; Pignon, J.P.; Le, Q.T.; Grégoire, V.; Grau, C.; Torres-Saavedra, P. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer: An individual patient data network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Wu, Y. High-dose hyperfractionated simultaneous integrated boost radiotherapy versus standard-dose radiotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer in China: A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pointer, K.B.; Pitroda, S.P.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: Open questions and future strategies. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, L.; Passante, M.; Cameli, N.; Cristaudo, A.; Patruno, C.; Nisticò, S.P.; Silvestri, M. Skin manifestations after ionizing radiation exposure: A systematic review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arct, J.; Pytkowska, K.; Dzierzgowski, S.; Neofitna, M. Oczar wirginijski (Hamamelis virginiana) w kosmetyce. Pol. J. Cosmetol. 2018, 21, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Marwicka, J.; Gałuszka, A.; Kotwica, M. Kosmeceutyki. Skład oraz oddziaływanie. Aesth. Cosmetol. Med. 2021, 10, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wszołek, K.; Piotrowska, A. Analiza składu wybranych kosmetyków dla pacjentów onkologicznych. Kosmetol. Estet. 2019, 8, 575–580. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Becerril, E.; Jimenez-Garcia, C.; Perula-de Torres, L.A.; Espinosa-Calvo, M.; Bueno-Serrano, C.M.; Romero-Ruperto, F.; Romero-Rodriguez, E.M. Efficacy of an aloe vera, chamomile, and thyme cosmetic cream for the prophylaxis and treatment of mild dermatitis induced by radiation therapy in breast cancer patients (the Alantel study). Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2024, 39, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuła, A.; Załęska, I.; Lizak, A.; Morawiec, M.; Drąg, J.; Wasylewski, M. Rola kosmetologa w diagnostyce oraz terapii nowotworowej. Kosmetol. Estet. 2018, 7, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Iżycki, D.M.; Janyszek, K.; Maciejewska, B.; Stankiewicz, M.; Zbrońska-Jankowska, I. Poradnik z Zakresu Kosmetologii Onkologicznej; Fundacja Otulina: Poznań, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.R.; Ma, L.; Xu, X.Y.; Zhou, S.; Xie, H.M.; Xie, C.S. Effects of aromatherapy on physical and mental health of cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy: A meta-analysis. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 30, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Meng, L.; Hou, X.; Qu, C.; Wang, B.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Radiation-induced skin reactions: Mechanism and treatment. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 11, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, A.J.; Kole, L.; Moran, M.S. Acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients: Challenges and solutions. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2017, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S.; Kanee, L.; Behroozian, T.; Wolf, J.R.; van den Hurk, C.; Chow, E.; Bonomo, P. Comparison of clinical practice guidelines on radiation dermatitis: A narrative review. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4663–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behroozian, T.; Goldshtein, D.; Wolf, J.R.; van den Hurk, C.; Finkelstein, S.; Lam, H.; Bonomo, P. MASCC clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of acute radiation dermatitis: Part 1) systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 58, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Sanz, J.; Rodríguez, N.; Duran, X.; Martínez, A.; Li, X.; Algara, M. Quantitative assessments of late radiation-induced skin and soft tissue toxicity and correlation with RTOG scales and biological equivalent dose in breast cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 24, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Garcia, C.; Perula-de Torres, L.A.; Villegas-Becerril, E.; Muñoz-Gavilan, J.J.; Espinosa-Calvo, M.; Montes-Redondo, G.; Romero-Rodriguez, E. Efficacy of an aloe vera, chamomile, and thyme cosmetic cream for the prophylaxis and treatment of mild dermatitis induced by radiation therapy in breast cancer patients: A controlled clinical trial (Alantel Trials). Trials 2024, 25, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzook, F.; Marzook, E.; El-Sonbaty, S. Allantoin may modulate aging impairments, symptoms and cancers. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 34, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.J.; Fang, H.F.; Wang, C.Y.; Chou, K.R.; Huang, T.W. Effect of hyaluronic acid on radiodermatitis in patients with breast cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 3965–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.C.; Wallen, M.P.; Chan, A.W.; Dick, N.; Bonomo, P.; Bareham, M.; Yoshidome, K. Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) clinical practice guidance for the prevention of breast cancer-related arm lymphoedema (BCRAL): International Delphi consensus-based recommendations. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 68, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korany, B.M.; Fathi, S.W.; Abdelkader, R.M.; Ibrahim, F.A. Effect of Post Radiation Instruction on Skin Outcomes among Patients Receiving Radiotherapy. Int. Egypt. J. Nurs. Sci. Res. 2025, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.A.; Balazy, K.E.; Gutkin, P.M.; Jacobson, C.E.; Chen, J.J.; Karl, J.J.; Horst, K.C. Association between patient education videos and knowledge of radiation treatment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 109, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.J.; Webster, J.; Chung, B.; Marquart, L.; Ahmed, M.; Garantziotis, S. Prevention and treatment of acute radiation-induced skin reactions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, H.J.; Lee, H.J.; Yang, J.I.; Kim, K.H.; Park, K.O.; Park, S.M.; Cho, K.H. Daily skin care habits and the risk of skin eruptions and symptoms in cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).