Excavation-Induced Disturbance in Natural Structured Clay: In-Situ Tests and Numerical Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. In Situ Tests Before and After Excavation

2.1. Case Description

2.2. Geotechnical Conditions

2.3. Instrumentation and Piezocone Test Before and After Excavation

2.4. Evaluation of Soil Disturbance After Excavation

3. Numerical Analyses

3.1. Numerical Model of the Excavation

3.1.1. Finite Element Model, Mesh, and Boundary Conditions

3.1.2. Material Models and Input Parameters

3.1.3. Steps for Numerical Simulation

- Establishing initial stress fields through K0 loading.

- Activating diaphragm walls and wall-soil interfaces.

- Resetting displacements induced by wall construction, then imposing horizontal wall displacements when the excavation depth was 8 m, and executing undrained elasto-plastic analysis.

- Imposing horizontal wall displacements when the excavation depth was 18.37 m, and executing undrained elasto-plastic analysis.

3.1.4. Model Validation

3.2. Soil Stress and Deformation Variations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Excavation-induced disturbance caused a decrease in the cone tip resistance. The disturbance degree of soil determined by cone tip resistance ranged from 0% to 50%.

- At identical locations, the disturbance degree of soil increased with excavation depth. Within the same CPTU boreholes, the disturbance degree firstly decreased and then increased with depth.

- The degree of soil disturbance is affected not only by the magnitude of the diaphragm wall horizontal displacement but also by its deformation distribution pattern. Although the horizontal displacement of the diaphragm wall increases with depth at shallow depths, the soil disturbance decreases, which is due to the formation of shear planes.

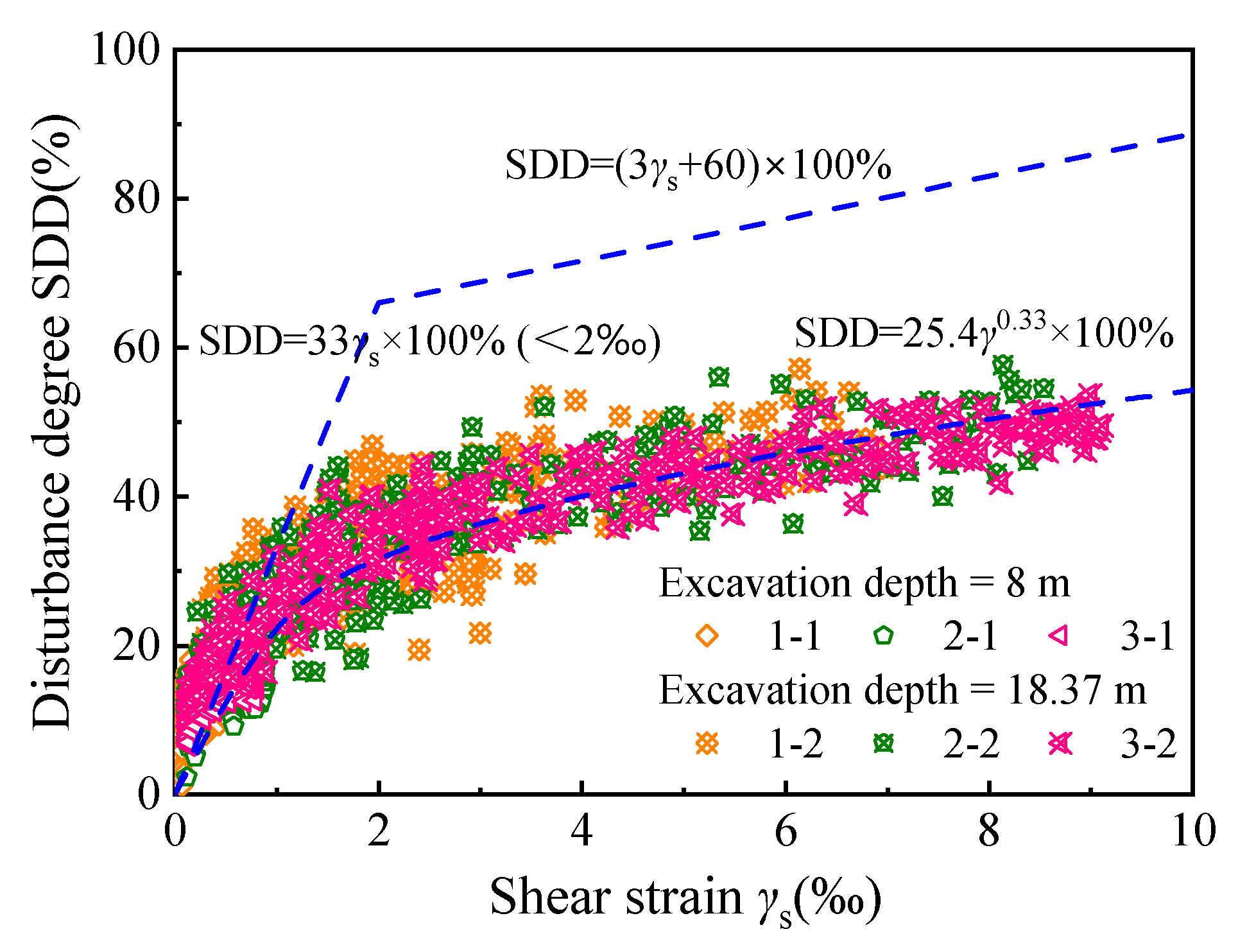

- The reason for excavation disturbance is the increase in shear stress caused by excavation. Consequently, soil shear strain can be associated with the disturbance degree of soil. Based on the numerical simulation and piezocone test results, it was found that the relationship between disturbance degree and shear strain can be expressed by a power function.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hong, Z.; Han, J. Evaluation of sample quality of sensitive clay using intrinsic compression concept. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, R.F.; Soares Gerscovich, D.M.; Danziger, B.R. Reconstructing oedometric compression curves for selecting design parameters. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagata, M.C.; Germaine, J.T. Sampling disturbance effects in normally consolidated clays. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2002, 128, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berre, T. Effect of sample disturbance on triaxial and oedometer behaviour of a stiff and heavily overconsolidated clay. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 51, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagata, M.; Germaine, J. Effect of OCR on sampling disturbance of cohesive soils and evaluation of laboratory reconsolidation procedures. Can. Geotech. J. 2005, 42, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemissa, M. Effects of disturbance on the behaviour of a normally consolidated soft clay. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2010, 14, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.-y.; Chen, R.-p.; Kang, X. Effects of tunneling-induced soil disturbance on the post-construction settlement in structured soft soils. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 80, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.S.; Lee, F.H.; Chong, P.T.; Tanaka, H. Effect of sampling disturbance on properties of Singapore clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2002, 128, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunne, T.; Berre, T.; Andersen, K.H.; Strandvik, S.; Sjursen, M. Effects of sample disturbance and consolidation procedures on measured shear strength of soft marine Norwegian clays. Can. Geotech. J. 2006, 43, 726–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.T.; Pineda, J.; Boukpeti, N.; Carraro, J.A.H.; Fourie, A. Effects of sampling disturbance in geotechnical design. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaqah, O.A.; Riemer, M.F. Minimizing sampling disturbance using a new in situ device. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2006, 26, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; Emdal, A.; Dijkstra, J. Consequences of sample disturbance when predicting long-term settlements in soft clay. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 1965–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, J.T.; Krage, C.P.; Albin, B.M.; DeGroot, D.J. Work-Based Framework for Sample Quality Evaluation of Low Plasticity Soils. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2018, 144, 04018074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, T.S.; Miura, N.; Chung, S.G.; Prasad, K.N. Analysis and assessment of sampling disturbance of soft sensitive clays. Geotechnique 2003, 53, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Tanaka, M. Main factors governing residual effective stress for cohesive soils sampled by tube sampling. Soils Found 2006, 46, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, S.; Long, M. Assessment of sample quality in soft clay using shear wave velocity and suction measurements. Geotechnique 2010, 60, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Ye, G.; Lan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, W. Research progress on disturbance mechanisms, evaluation methods and control measures for sampling of soft clay. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 47, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.; Tschuchnigg, F.; Schweiger, H.F.; Liu, S.; Shiau, J.; Cai, G. A numerical study of deep excavations adjacent to existing tunnels: Integrating CPTU and SDMT to calibrate soil constitutive model. Can. Geotech. J. 2025, 62, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ye, J.; Bian, X.; Chen, Y. Soil disturbance evaluation of soft clay based on stress-normalized small-strain stiffness. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Nakata, E.; Minami, M.; Hibino, E.; Tani, T.; Sakakibara, J.; Yamada, N. Estimation of the zone of excavation disturbance around tunnels, using resistivity and acoustic tomography. Explor. Geophys. 2004, 35, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, F.; Marcuello, A.; Ledo, J.; Queralt, P.; Falgàs, E.; Benjumea, B.; Velasco, V.; Vázquez-Suñé, E. Time-lapse cross-hole electrical resistivity tomography monitoring effects of an urban tunnel. J. Appl. Geophys. 2012, 87, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.F.; Sun, D.A.; Sun, J.; Fu, D.M.; Dong, P. Soil disturbance of Shanghai silty clay during EPB tunnelling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2003, 18, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.P.; Li, Z.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Ou, C.Y.; Hu, Q.; Rao, M. Failure Investigation at a Collapsed Deep Excavation in Very Sensitive Organic Soft Clay. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2015, 29, 04014078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Ye, J.; Zhao, C.; Bian, X. Soil disturbance induced by shield tunnelling in sensitive clay: In situ test and analyses. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 42, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Li, Z.; Yang, K.; Chen, Y.; Bian, X. Shield tunneling-induced disturbance in soft soil. Transp. Geotech. 2023, 40, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, W.; Ye, J.; Chen, Y.; Bian, X.; Gao, F. Soil movement mechanism associated with arching effect in a multi-strutted excavation in soft clay. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 110, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOHURD. Code for Investigation of Geotechnical Engineering; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Wu, K.; Liu, S.; Cai, G. Method for estimating three-dimensional effects on braced excavation in clay. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 141, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finno, R.J.; Blackburn, J.T.; Roboski, J.F. Three-dimensional effects for supported excavations in clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2007, 133, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaxis BV. Plaxis 2D. In Plaxis 2D User’s Manual; Plaxis BV: Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Y.-M.; Dang, P.H.; Lin, H.-D. How small strain stiffness and yield surface affect undrained excavation predictions. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, T.; Vermeer, P.A.; Schwab, R. A small-strain overlay model. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2009, 33, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Liu, S. Numerical Analyses of an Excavation Case in Thick Soft Clay with the Aid of SCPTU Test. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Wu, W., Zhou, Y., Leung, C.F., Li, X., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1147–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.P.; Liu, M.C.; Meng, F.Y.; Wu, H.N.; Li, Z.C. Soil Arching Effect Associated with Ground Movement and Stress Transfer Adjacent to Braced Excavation in Clayey Ground. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2023, 149, 2735–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Meng, F.; Liu, Z.; Chen, R. Observed soil arching-induced ground deformation and stress redistribution behind braced excavation. Can. Geotech. J. 2024, 61, 2735–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Chen, R.; Kang, X.; Li, Z. e-p curve-based structural parameter for assessing clayey soil structure disturbance. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 4387–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Chen, R.; Mooney, M.A.; Wu, H.; Jia, Q. Evaluation of shield tunneling-induced soil disturbance in typical structured clays. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil | St | ω (%) | γ (kN/m3) | e | IL | Ip | Es (MPa) | (kPa) | (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fill | - | 34.3 | 18.2 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 15.0 | 3.74 | 18.9 | 9.0 |

| Mucky silty clay | 4.5 | 36.0 | 17.9 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 14.1 | 3.57 | 13.3 | 13.0 |

| Sandstone | - | - | 25.3 | - | - | - | - | - | 38.4 |

| Soil | γ (kN/m3) | E′ (MPa) | ν′ | c′ (kPa) | φ′ (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fill | 18.2 | 10 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 30 |

| Sandstone | 25.3 | 500 | 0.3 | 2000 | 0.1 |

| Mucky silty clay | γ (kN/m3) | c′ (kPa) | |||

| 17.9 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 13.8 | 0.1 | |

| φ′ (°) | (MPa) | γ0.7 (10−4) | m | νur | |

| 26 | 56 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Lu, T.; Shan, Z.; Shen, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; He, H. Excavation-Induced Disturbance in Natural Structured Clay: In-Situ Tests and Numerical Analyses. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12201. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212201

Wang F, Lu T, Shan Z, Shen K, Wang Y, Zhang D, He H. Excavation-Induced Disturbance in Natural Structured Clay: In-Situ Tests and Numerical Analyses. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12201. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212201

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fangtong, Taishan Lu, Zhigang Shan, Kanmin Shen, Yong Wang, Dingwen Zhang, and Huan He. 2025. "Excavation-Induced Disturbance in Natural Structured Clay: In-Situ Tests and Numerical Analyses" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12201. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212201

APA StyleWang, F., Lu, T., Shan, Z., Shen, K., Wang, Y., Zhang, D., & He, H. (2025). Excavation-Induced Disturbance in Natural Structured Clay: In-Situ Tests and Numerical Analyses. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12201. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212201