Abstract

The world has adopted so many IoT devices but it comes with its own share of security vulnerabilities. One such issue is ARP spoofing attack which allows a man-in-the-middle to intercept packets and thereby modify the communication. Also, this allows an intruder to gain access to the user’s entire local area network. The ACI-IoT-2023 dataset captures ARP spoofing attacks, yet its absence of specified extracted features hinders its application in machine learning-aided intrusion detection systems. To combat this, we present a framework for ARP spoofing detection which improves the dataset by extracting ARP-specific features and evaluating their impact under different time-window configurations. Beyond generic feature engineering and model evaluation, we contribute by treating ARP spoofing as a time-window pattern and aligning the window length with observed spoofing persistence from the dataset timesheet—turning window choice into an explainable, repeatable setting for constrained IoT devices; by standardizing deployment-oriented efficiency profiling (inference latency, RAM usage, and model size) reported alongside accuracy, precision, recall and F1-scores to enable edge-feasible model selection; and by providing an ARP-focused, reproducible pipeline that reconstructs L2 labels from public PCAPs and derives missing link-layer indicators, yielding a transparent path from labeling to windowed features to training evaluation. Our research systematically analyzes five models with multiple time-windows, including Decision Tree, Random Forest, XGBoost, CatBoost, and K-Nearest Neighbors. This study shows that XGBoost and CatBoost provide maximum performance at the 1800 s window that corresponds to the longest spoofing duration in the timesheet, achieving accuracy greater than 0.93%, precision above 0.95%, recall near 0.91%, and F1-scores above 0.93%. Although Decision Tree has the least inference latency (∼0.4 ms.), its lower recall risks missed attacks. By contrast, XGBoost and CatBoost sustain strong detection with less than 6$ ms inference and moderate RAM, indicating practicality for IoT deployment. We also observe diminishing returns beyond (∼1800 s) due to temporal over-aggregation.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) now spans smart homes, wearable healthcare, industrial control, and critical infrastructure. Heterogeneous devices, decentralized architectures, and constrained resources expose IoT networks to diverse attacks. In particular, higher-layer threats such as botnet-driven DDoS, obfuscation-assisted malware evasion, and false-data injection in cyber–physical systems are well documented and have shaped L3–L7-centric defenses [1,2,3]. By contrast, link-layer integrity remains uneven in practice.

We therefore focus on ARP spoofing—an often overlooked Layer 2 vector that poisons IP–MAC bindings in the broadcast domain to enable man-in-the-middle interception, modification, or disruption. While enterprise networks may mitigate the risk with managed switches, VLANs, or Dynamic ARP Inspection, many IoT deployments lack uniform policies and device agents, creating a persistent blind spot. This motivates lightweight, time-windowed link-layer features and resource-aware classifiers tailored for constrained environments.

Adopting static ARP tables, Dynamic ARP Inspection (DAI), and DHCP snooping, can provide limited protection. Nonetheless, these approaches often depend on stringent configuration policies and uniform infrastructure controls, which are not feasible due to the lack of resources or the ever-changing nature of IoT settings. In many instances, IoT deployments function within loosely managed networks–occasionally even behind consumer-grade routers–where configuring infrastructure level is often untenable. Furthermore, static or signature-based defenses do not function well because IoT devices regularly change IP or MAC associations because of mobility, firmware updates, and power cycling. As a result, there needs to be more adaptive, intelligent, and resource-aware mechanisms to detect spoofing behaviors that exploit ARP’s trust by default property.

Link-layer attacks such as ARP spoofing remain undetected in many instances. On the contrary, the same cannot be said about attacks at other layers such as HTTP or TCP. The two latter threats see huge attention in comparison with the former threats. Currently, solutions for intrusion detection systems (IDS) with deep packet inspection are designed and optimized up to Layer 3. As a result, such solutions likely miss some layer-wise patterns. Strategies for securing IoT must include a solution for such a blind spot. Interestingly enough, many legacy or reduced footprint IoT operating systems do not support a host-based firewall agent. Also, sophisticated anomaly detection may not be possible for every IoT device because of CPU and memory.

Because of these challenges, there is need for some lightweight and real-time ARP spoofing detection systems which do not need heavy feature extraction and processing. The system must be resilient when the structure of a network changes due to IoT. Moreover, the system must be able to detect unknown attack variations.

Although the approaches based on machine learning show promise in enabling adaptive detection of threats, they require a reasonable amount of labelled data for training in addition to features engineered to capture spoofing specifics. Publicly available datasets and testbeds are not primarily focused on the IOT ARP layer. Consequently, a lack of robust empirical grounding hampers researchers’ ability to develop and test their models, creating significant obstacles in their work.

1.1. Motivation and Problem Statement

Although machine learning has yielded good results in many intrusion detection tasks, its application to ARP spoofing detection faces challenges for multiple reasons. Chief among these is the lack of appropriate datasets. The IoT network datasets available today mainly consist of upper layer attacks such as DDoS, dictionary brute-forcing attempts, or MQTT-based attacks. As such, ARP-level data are either very poorly represented in the literature or completely lacking. There is either a lack or inadequacy of any spoofing attack label on ARP traffic where it is logged, rendering supervised learning unusable.

The ACI-IoT-2023 dataset [4] is a recent dataset that contains the raw PCAP files from real or emulated IoT environments. Importantly, it records times when ARP spoofing is thought to take place. However, the extracted features from this dataset focus on higher-layer attacks only and miss out on the essential ARP indicators. These include request/reply ratios, MAC/IP anomalies, or timing anomalies. Without these features and labels, researchers will face difficulties in re-extracting the traffic from the raw PCAPs, manually identifying and labelling spoofing attacks and engineering domain-specific features. If not conducted systematically, it is a long process and can be inconsistent.

Thus, the task transcends mere categorization. Researchers may find packets in the spoofing window, but capturing the ARP spoofing essence requires a time-based analysis. ARP spoofing frequently has a brief duration. The attacker sends replies over time to make the victim save wrong MAC-IP connections. To highlight this tendency, one needs to survey the ARP traffic through time-window analysis along with temporal aspects. Likewise, many IoT systems utilize energy-saving modes which can create momentary spikes or sporadic disconnections in signal light. One can observe a static IP and MAC entity which helps in monitoring the functionality of some critical hosts in the network system.

Given these issues, the main objective is to enhance ARP spoofing detection with additional ARP features and labels in an existing IoT dataset and to develop a machine learning pipeline that is resource-friendly and realistically deployable in IoT environments. A solution like this would serve both researchers benchmarking new detection techniques as well as practitioners requiring utilities to secure their deployments.

1.2. Motivation for a Feature-Rich ARP Dataset

ARP spoofing detection goes beyond mere labeling, and it entails the analysis of link-layer behavior. Within packet frequency, opcode, and MAC-IP binding distributions, ARP spoofing will likely manifest as an anomaly rather than the spike. It is important to engineer and analyze time-window features. By summing the ARP packets in the given time interval, one can compute statistics such as

- Frequency Ratios: The ratio of ARP requests to ARP replies.

- Unique Mappings: The number of unique MAC addresses per IP or unique IPs per MAC.

- Timing Metrics: Average inter-arrival times, standard deviation of arrival times, and spikes in ARP replies.

Analyzing packets in isolation cannot reveal any anomalies but using those features helps detect them. An aggressor may employ only a handful of malicious responses, spaced out over time and hiding them amongst ordinary packets. Time-window amalgamation is useful in these instances as they expose fundamental variance of normal activities.

It is not easy, however, to engineer these features, particularly for large PCAPs and IoT topologies. “All the devices in the experiment are timestamped in sync, aligned with the known time a DOS attacks occurs, and any device that goes down periodically (switching off or to sleep state) is properly handled.” This highlights the importance of a robust and systematic ARP spoofing extraction pipeline to create effective training and testing datasets.

1.3. Research Contributions

This research contributes to the IoT security landscape in several key ways:

- Deployment-Oriented Efficiency Profiling. Whereas many studies report only classification metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, and F1), we add deployment critical measurements Inference Latency, RAM Usage, and Model Size so model selection is guided by both detection quality and resource feasibility on IoT/edge devices.

- Time-Window ARP Modeling. We treat ARP spoofing as a frame pattern and choose the window length by how long spoofing typically persists in practice. This turns window choice from trial-and-error into an explainable, repeatable setting that remains effective without heavy payload parsing—useful for constrained IoT devices.

- ARP-Focused Dataset Enablement. We reconstruct ARP-layer labels and derive link-layer indicators from public PCAPs where such features are absent in extracted CSVs, enabling supervised learning and reproducible benchmarking for L2 spoofing.

- Reproducible Pipeline with Explanatory Ablations. We document a transparent, scriptable pipeline—from labeling through windowed feature construction to training/evaluation under a fixed stratified split with a held-out test set—and include ablations that explain observed performance patterns rather than reporting aggregates only.

1.4. Organization of the Paper

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2, in which we review related work on MITM detection for the IoT, as well as a survey of public IoT datasets with respect to coverage and gaps in MITM. In Section 3, we present our approach to label data in accordance with the attack timeline. In Section 4, we describe our experimental setup and evaluation protocol, including ablation and generalization analyses. Section 5 summarizes the detection results over varying window lengths and classifiers, and models the trade-offs and snapshot efficiency. The implications, limitations, and deployment considerations are discussed in Section 6. Section 7 concludes the paper. To finish, in Section 8, we describe possible future work, in particular, adaptive time-window and other link-layer protocol extensions.

2. Related Work

In the field of network securities and safety, IDS has witnessed a lot of advancement. This part of the report will look over how IDS evolved from rule-based to AI-based systems. The IDS’s evolution is first presented, ranging in effort from rule-based to anomaly-based and then now using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques [5,6,7]. Next, we examine the challenges and developments of intrusion detection systems in terms of the IoT and edge computing settings [8,9,10]. We focus on the detection of Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) spoofing attacks, which are a common and sustained type of attack in LANs and IoT. We finish by checking out the limitations of previously used datasets for ARP spoofing behaviours and how the ACI-IoT-2023 dataset supplements those deficiencies through further feature engineering and tailored extraction [11].

2.1. Evolution of Intrusion Detection Systems

Intrusion detection systems (IDS) have evolved from rule-based models to hybrid frameworks integrating behavioral and statistical analysis. Early systems like MIDAS and Haystack relied on fixed patterns, later extended by signature-based tools such as Snort and Bro/Zeek for real-time threat recognition [12,13,14]. However, these systems struggled to detect novel threats. Anomaly-based IDS addressed this by modeling normal behavior and identifying deviations, but suffered from high false positives. Hybrid approaches were developed to combine rule matching with anomaly detection for improved adaptability [15,16,17,18,19,20]. This historical progression sets the foundation for integrating adaptive ML techniques into modern IDS design.

2.2. The Use of AI and Machine Learning in IDS

AI and machine learning have significantly enhanced IDS by enabling automated threat recognition. Supervised models like SVM, Decision Trees, and Gradient Boosting offer high accuracy, while unsupervised methods such as One-Class SVM, DBSCAN, and K-Means help discover unknown threats [21,22,23,24]. Deep learning models (CNN, LSTM, GRU, and DNN) further improve feature extraction and sequence learning [25,26]. Ensemble learning, adversarial defense, and explainable AI (XAI) continue to address challenges in interpretability and robustness [27,28,29,30,31]. In IoT, where computational resources are limited, lightweight models and optimization techniques such as pruning or quantization are essential [32,33]. However, many ML-based IDS frameworks still face challenges in interpretability and deployment under constrained environments.

2.3. IDS for IoT and Edge Computing Environments

Conventional IDS frameworks typically assume sufficient computing resources, which is rarely true in IoT contexts. IoT devices often operate under strict constraints in power, memory, and processing capacity [34], and use diverse protocols that hinder standard IDS deployment. Lightweight IDS designs have emerged, prioritizing model simplicity, memory usage, and communication efficiency [35]. Techniques such as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation help compress complex ML models for constrained endpoints [36]. Edge computing enables on-site traffic analysis, reducing latency and bandwidth usage [37]. Some IDS frameworks leverage gateways for early anomaly detection or as hosts for federated learning [38], allowing collaborative training without exposing raw data [39]. Reinforcement learning is also used to adapt detection strategies in dynamic environments [40]. Although techniques like transfer learning and multi-domain generalization exist, deploying IDS in real-world verticals such as IIoT, IoMT, or V2X still demands real-time guarantees and layered defense mechanisms [41,42,43,44]. These constraints highlight the need for models that balance detection performance with resource efficiency for real-world IoT applications.

2.4. Limitations of Existing Datasets

Numerous public datasets have been proposed for intrusion detection system (IDS) evaluation, but most lack sufficient coverage of Layer 2 attacks such as ARP spoofing. Early datasets like KDD’99 and its improved variant NSL-KDD [45,46] focused heavily on TCP/IP Layer 3+ threats and are now considered outdated in terms of traffic diversity and protocol realism. More recent datasets such as BoT-IoT [47], MedBIoT [48], and MQTT-IoT-IDS2020 [49] expand coverage to IoT-specific scenarios but continue to omit ARP-layer visibility. CICIDS2017 [50] is widely used for network intrusion benchmarks, yet lacks Layer 2 attack instances.

Recent dataset IoT-23 [51] provides diverse real-world IoT traffic but does not include Layer 2 ARP spoofing data.

In contrast, the ACI-IoT-2023 dataset includes raw PCAP traces with ARP spoofing attacks and provides a documented attack timeline for ground truth alignment. This makes it a practical foundation for reproducible machine learning research targeting Layer 2 attacks. A custom feature extraction pipeline can be applied to derive ARP-specific characteristics for training and evaluation in lightweight ARP spoofing detection systems.

Table 1 provides a comparative summary of commonly referenced datasets with respect to ARP spoofing availability and their suitability for ML-based detection.

Table 1.

Comparison of public datasets for ARP spoofing in IoT intrusion detection research.

2.5. ARP Spoofing Detection Using Machine Learning

ARP spoofing is a very serious Layer 2 threat on local networks and IoT networks due to un-authentication in the ARP protocol. Attackers can carry out man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks by poisoning the ARP cache so as to forge replies and associate their MAC address with the IP address of another legitimate machine. Conventional mitigation strategies are often unscalable or depend on the infrastructure, making them unappealing to heterogeneous and decentralized systems like the Internet of Things (IoT) [52,53,54,55].

To solve these problems, applications of machine learning (ML)-based approaches are increasing in ARP spoofing detection. Past studies indicate that classifiers such as Decision Trees, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, CatBoost, and KNN can classify spoofed ARP traffic based on its various statistical and temporal metrics including ARP frequency, inter-arrival time, MAC–IP mismatches etc. [56,57,58]. Many of the works measure the performance using accuracy-related measures precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC. However, there is less focus on actual limitations in resource-constrained deployments. Although accuracy is important, it will not help a malware detector completely if it does not perform well in terms of memory size and CPU and also takes a long time to work on the input data.

This highlights the need to evaluate the detection of ARP spoofing more from the classification perspective but also on an implementation level on constrained IoT hardware. Table 2 summarizes the selected ML models considered in this study with brief traits and deployment implications.

Table 2.

Comparison of AI models for ARP spoofing detection in constrained IoT deployments.

3. Methodology

In this section, we describe the methodology proposed to detect ARP spoofing in IoT implementation which involves data preprocessing, feature engineering, and supervised machine learning model selection and metrics. Our method focuses on the detection of ARP spoofing attacks using time-window feature engineering and lightweight ML models.

3.1. Dataset Preparation and ARP Spoofing Extraction

3.1.1. Dataset Source

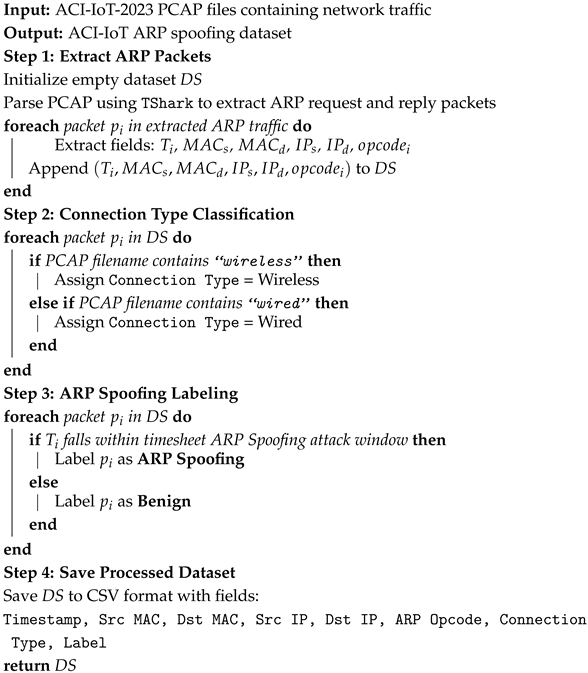

We use the ACI-IoT-2023 dataset, which contains IoT traffic with both benign and attack activities. However, the released feature set does not annotate ARP spoofing; such attacks exist only within the accompanying PCAP files. To bridge this gap, we developed a PCAP processing pipeline that extracts ARP request/reply frames and assigns labels by aligning packets with curated attack time-window, thereby constructing an ARP-specific dataset (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1: ARP spoofing dataset generation from ACI-IoT dataset |

|

3.1.2. Extracted ARP Features

The extracted dataset, ACI-IoT ARP spoofing dataset, includes key ARP attributes used for subsequent feature engineering and model training as Table 3. However, while ARP Opcode differentiates request and reply messages, it alone is insufficient for detecting ARP spoofing. To enhance the detection capability, we introduce time-window feature engineering(Algorithm 2) to capture abnormal MAC-IP behaviors over time.

| Algorithm 2: ARP spoofing feature extraction and enhancement |

|

Table 3.

Extracted ARP spoofing features from ACI-IoT dataset.

3.2. Feature Engineering

To improve how we detect ARP spoofing, we came up with some new features as Table 4. These features help us measure behaviour over time. Plus, we made sure that the time-window does not go much longer than the maximum attack time we defined in the dataset. The impact of different time-window w on detection performance will be further analyzed in the Section 4.

Table 4.

Computed ARP spoofing features for model training.

3.3. Machine Learning Model Selection

We trained a number of models and see their performance accuracy and efficiency concerning ARP spoofing detection. The models selected for evaluation include the following:

- Decision Tree (DT): A rule-based model that provides interpretability with low computational overhead.

- Random Forest (RF): An ensemble learning method that reduces overfitting by combining multiple decision trees.

- XGBoost (XGB): A Gradient Boosting algorithm optimized for speed and performance.

- CatBoost (CB): A Gradient Boosting model designed for categorical data processing.

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): A non-parametric, distance-based classification model.

All the models were trained and tested for the best accuracy and computational efficiency for their feasibility in IoT implementation. The dataset was divided into training and testing splits in the ratio of 80/20. Further, we examined model performance during varied time-window w and tracked inference latency, RAM usage, and model size during the testing stage. The hyperparameter specification used across all experiments is provided in Table A3 and Table A4.

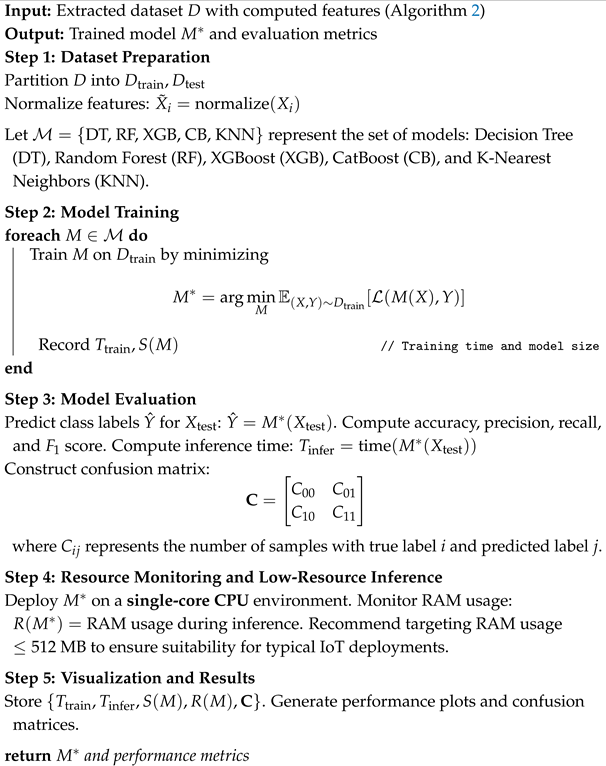

3.4. Resource-Constrained Inference Setup

To simulate real IoT environments, which have limited computing resources, we analyzed the model performance under limited computing conditions. ARP spoofing detection is mainly deployed in IoT devices (Algorithm 3), so we focused on computational efficiency.

| Algorithm 3: ARP spoofing detection model training and inference |

|

CPU and Memory Constraints

This ensures that the proposed detection framework is efficient and flexible whereas in the real world, IoTs computing resources are scant.

- During inference, the models were tested on a single-core CPU environment.

- RAM use was monitored to assess model viability for resource-constrained IoT devices.

- The 512 MB RAM mark serves as a rule-of-thumb for lightweight feasibility. It is not absolute; exceeding it usually confines deployment to higher-performance IoT devices or edge platforms.

3.5. Model Evaluation Metrics

The performance of each model was assessed using both classification accuracy and computational efficiency, and the evaluation metrics are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation metrics for ARP spoofing detection models.

3.5.1. Classification Performance Metrics

Each model was evaluated using standard classification metrics:

- Accuracy: The proportion of correctly classified instances:

- Precision: The percentage of ARP spoofing predictions that were actually malicious:

- Recall: The model’s ability to detect all ARP spoofing attempts:

- F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing false positives and false negatives:

These metrics were computed using the test dataset to ensure model generalization.

3.5.2. Computational Efficiency Metrics

Since deployment on IoT devices is a primary goal, we analyzed the following:

- Inference Latency (ms): The time taken for a model to classify a new ARP packet. This was measured using Python’s time() function to compute execution time per inference.

- Model Size (KB): The storage footprint of the trained model, affecting IoT deployment feasibility. The model file size was obtained using os.path.getsize(model_file).

- RAM Usage (MB): The memory consumption during model inference. This was monitored using psutil.Process().memory_info().rss to track runtime memory allocation.

These factors guided the selection of models best suited for real-time IoT deployment.

3.6. Methodology Summary

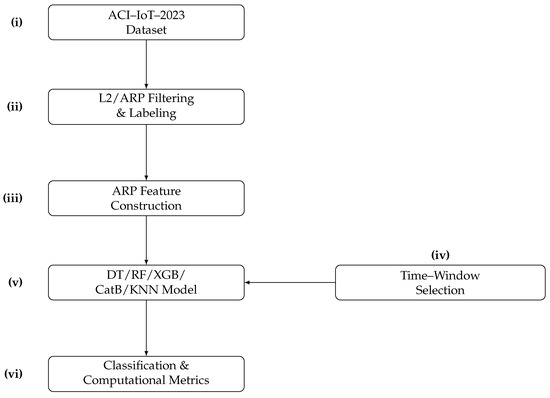

Figure 1 overviews our pipeline. We (i) select the ACI-IoT-2023 dataset; (ii) filter PCAPs to ARP and align labels to the attack timeline; (iii) construct lightweight link-layer features (counts/ratios, MAC-IP uniqueness, and simple timing cues); (iv) choose the time-window w that governs training and inference (right callout); (v) train standard classifiers (DT, RF, XGB, CatB, and KNN); and (vi) evaluate classification and computational efficiency (latency, RAM, and model size). This compact flow clarifies how each stage connects without heavy notation.

Figure 1.

Diagram for lightweight training approach for research.

4. Experiment

This section describes how we evaluate the ARP spoofing detection mechanism. In this part, we have discussed the processing of the dataset, training of the model, inference constraints, and evaluation criteria. This will ensure that the performance evaluation is realistic under the computational limitations of the IoT.

We also analyze how various time-window w sizes affect the model performance to ascertain the most suitable feature extraction window for ARP spoofing detection. In the Section 5 we discuss how different w affect classification accuracy and inference latency as well as memory consumption.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset Processing

Our experiments were conducted on the ACI-IoT-2023 dataset, which was processed using a custom extraction pipeline to generate a new dataset that contains labeled ARP traffic.

- Packet Capture Processing: Using TShark, we extracted ARP requests and replies from the dataset’s PCAP files.

- Feature Engineering: Constructed time-window statistical features to improve ARP spoofing detection.

- Time-Window: We tested multiple time-window w ∈ {60 s, 300 s, 600 s, …, 3000 s} to evaluate their impact on classification performance.

- Final Dataset: The processed dataset was used as input for all training and evaluation tasks.

4.1.2. Experimental Environment

The experiments were conducted in a controlled computing environment with the following specifications:

- Processor: Intel Core i7-12700K @ 3.60 GHz.

- RAM: 32 GB DDR4 3200 MHz.

- OS: Ubuntu 22.04 LTS.

- Program language: Python 3.10.12

- ML Libraries:

- -

- Classification Algorithms: DecisionTreeClassifier, RandomForestClassifier, KNeighborsClassifier (Scikit-learn), XGBClassifier (XGBoost), and CatBoostClassifier (CatBoost).

- -

- Other dependencies: pandas, numpy, psutil, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score, accuracy_score, confusion_matrix, train_test_split, and SimpleImputer.

All models were trained and tested under similar conditions of hardware and software to ensure consistent benchmarking. Even though all available resources of the system were utilized for training, inference of the model was specifically tested in a single-core CPU environment to evaluate the feasibility for real-world IoT deployment.

4.2. Model Training and Testing

4.2.1. Train–Test Split

To evaluate model performance, we applied a stratified 80/20 hold-out on the raw timestamped records, preserving the benign and ARP-spoofing proportion in both partitions. For each time-window w, the window-derived features (e.g., fixed-window counts and ratios) were then computed independently within each partition, ensuring that aggregation never crossed the train/test boundary and thus preventing temporal leakage. Models were trained on the 80% partition and evaluated once on the held-out 20% partition; all reported classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1) and efficiency measurements (inference latency, RAM usage, and model size) were obtained on the test set under single-core inference.

4.2.2. Dataset Partitions

- The 80% training set: Used exclusively to fit model parameters for each w. Hyperparameters are fixed a priori (see Table A3).

- The 20% test set: Held out and never used during training; used once for independent evaluation to report classification metrics and efficiency measurements.

4.2.3. Validation Approach

Given the temporal structure of windowed samples, we favored a leakage-aware, deployment-oriented hold-out rather than random K-fold cross-validation, which can inadvertently mix adjacent contexts in different folds. Time-aware validation schemes (e.g., blocked/episode-level or rolling-origin) are orthogonal to our comparison of window sizes and are planned as complementary robustness analysis in future work.

4.2.4. Machine Learning Models

We trained the following models for ARP spoofing detection:

- Decision Tree (DT)

- Random Forest (RF)

- XGBoost (XGB)

- CatBoost (CB)

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

Each model was first trained using default parameters. Limited adjustments were applied based on validation performance to balance detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

4.2.5. Feature Importance Analysis

To understand feature contributions, we analyzed feature importance scores from tree-based models (Random Forest, XGBoost, and CatBoost).

4.3. Constrained Resource Inference Testing

To simulaterealistic IoT deployment constraints, we evaluated model inference under a single-core CPU environment.

Single-Core Execution

- Models were tested on a single-threaded execution environment, ensuring realistic lightweight deployment conditions.

- We measured RAM usage and inference latency during testing to assess feasibility for resource-constrained IoT devices.

4.4. Performance Evaluation

4.4.1. Classification Metrics

Each model was evaluated based on

- Accuracy: Correctly classified instances as a proportion of total instances.

- Precision: Percentage of ARP spoofing predictions that were actually malicious.

- Recall: The proportion of actual ARP Spoofing cases correctly identified.

- F1-score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall.

A confusion matrix was also generated to assess false positives (FPs) and false negatives (FNs).

4.4.2. Computational Efficiency

Considering the resource constraints of IoT devices, we evaluated the following:

- Inference Latency (ms): Time taken for a model to classify new network packets. This was measured using Python’s time() function.

- Model Size (KB): The storage footprint of the trained model. The model file size was obtained using os.path.getsize(model_file).

- RAM Usage (MB): Memory consumption during inference. This was monitored using psutil.Process().memory_info().rss to track runtime memory allocation.

These measurements were taken during single-core execution, ensuring real-world feasibility for IoT edge deployment.

5. Results

The performance metrics of the ARP spoofing detection models are discussed in this section. These metrics include the accuracy of detection, the computational cost of the models, and the performance with various time-window. The metrics used for evaluation are the classification performance (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) and the consumption of computational resources (train time, inference latency, model size, and RAM consumption). All results are achieved from experiments in resource-constrained settings where model inference was limited to one CPU core.

5.1. Classification Performance Analysis

To evaluate the impact of different time-window w on model performance, we conducted experiments using w ∈ {60 s, 300 s, 600 s, …, 3000 s}. Larger time-windows provide more temporal information but may also introduce redundant data.

When w exceeds the longest spoofing duration documented in the ACI-IoT-2023 timesheet (∼1800 s), metrics tend to plateau or show slight regression due to temporal dilution benign and attack segments being averaged within a single window, so we regard ∼1200–1800 s as a practical operating regime. The decrease from 1500 s to the next step is a local transition effect: boundary aliasing briefly mixes benign and spoofed segments, the number of windows falls and window-level class proportions shift, and several discrete indicators (e.g., MAC-IP uniqueness) change non-monotonically; with a slightly larger w, aggregation realigns with spoofing persistence and the metrics recover.

Table 6 summarizes the classification performance of each model across different time-windows. The results indicate that an optimal w exists where the balance between detection accuracy and computational overhead is maintained.

Table 6.

Classification performance metrics across different time-windows.

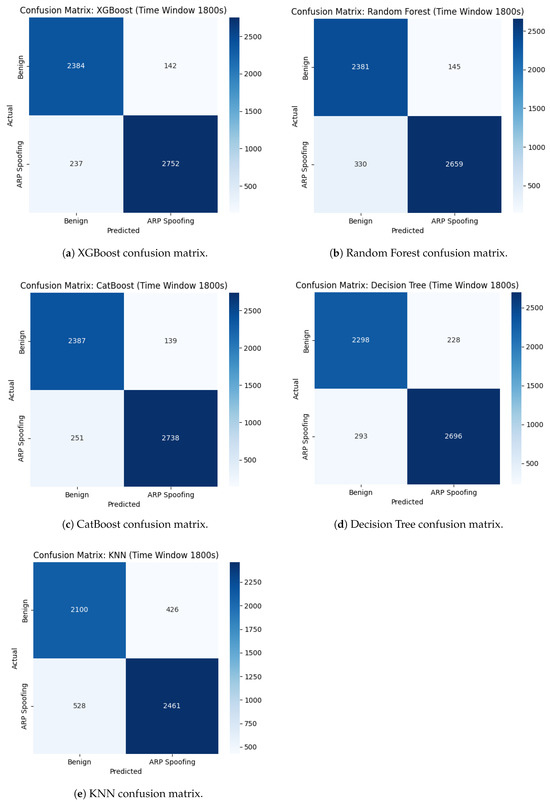

5.2. Confusion Matrices

To further analyze model performance, Figure 2 presents confusion matrices for the XGBoost and Random Forest models, which demonstrated the best classification accuracy.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrices for different models at time-window 1800 s. (a) XGBoost; (b) Random Forest; (c) CatBoost; (d) Decision Tree; (e) KNN.

5.3. Computational Efficiency Analysis

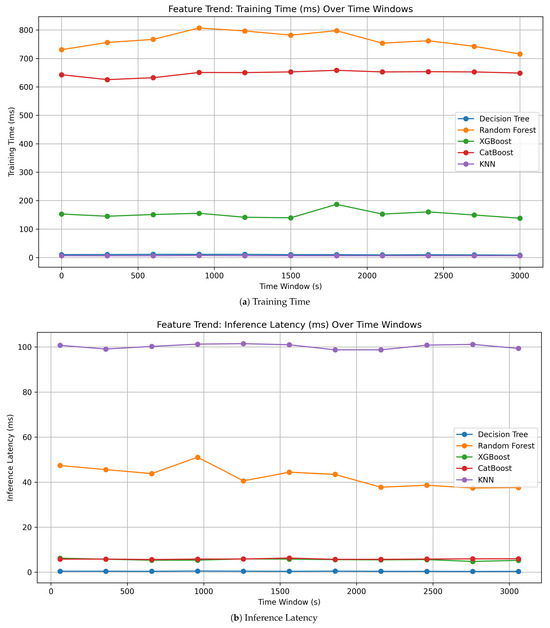

Per-sample inference time is essentially independent of w because prediction operates on a fixed-size feature vector; what grows with larger windows is the pre-aggregation waiting time required to accumulate one window before prediction—the external time to first decision.

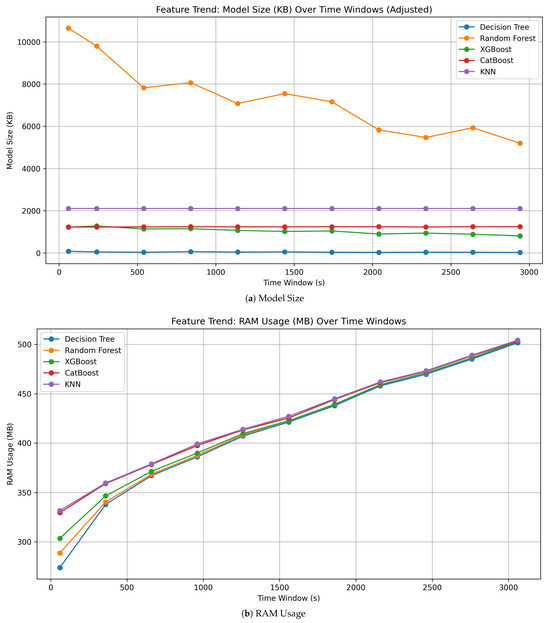

In addition to classification accuracy, we evaluated the computational efficiency of different models under varying time-window w. Larger w values incorporate more statistical context but also increase RAM consumption.

Table 7 presents the computational cost associated with each model, considering training time, inference latency, model size, and RAM usage across different w values. These results highlight the trade-off between accuracy and resource consumption, which is crucial for real-world IoT deployments.

Table 7.

Computational efficiency metrics across different time-windows.

5.4. Performance Visualization

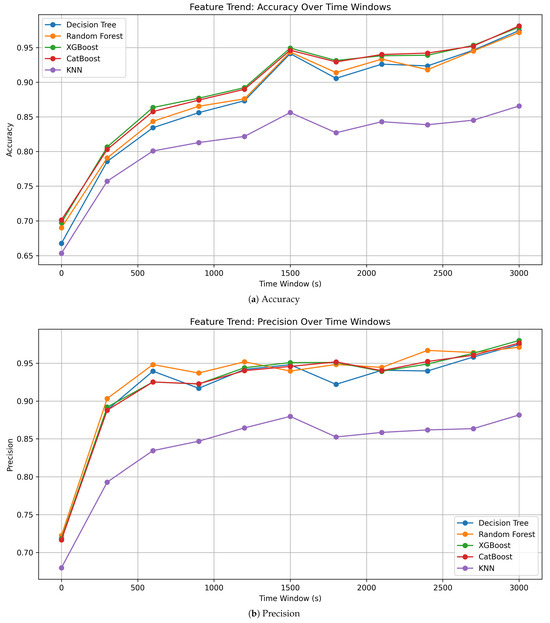

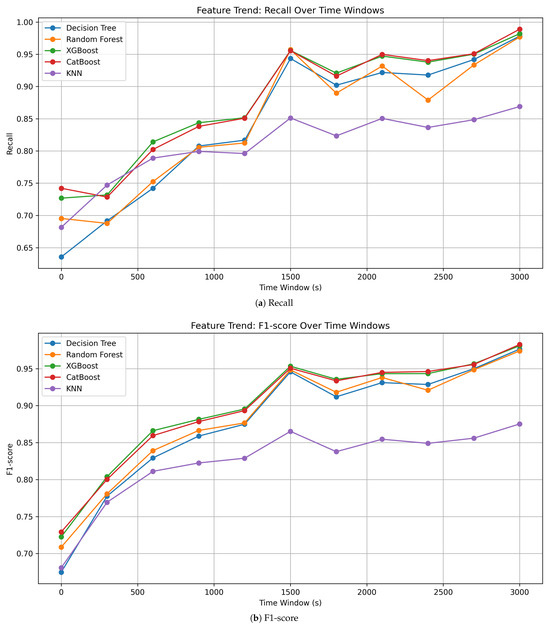

Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 visualize the trends of accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, training time, inference latency, model size, and RAM usage across different time-windows.

Figure 3.

Accuracy and precision across time-windows.

Figure 4.

Recall and F1-score across time-windows.

Figure 5.

Training time and inference latency across time-windows.

Figure 6.

Model size and RAM usage across time-windows.

6. Discussion

This section analyzes the experimental results, focusing on classification performance, the impact of time-window selection, computational efficiency, and a comparison with existing research on ARP spoofing detection.

6.1. Evaluation of Classification Results

As shown in Table 6, Figure 3 and Figure 4 XGBoost and CatBoost consistently achieve the highest accuracy and F1 score in most time-windows. This confirms that Gradient Boosting models are suitable for detecting ARP spoofing attack in network traffic.

Key observations include the following:

- XGBoost and CatBoost: This model had the best performance and stable output in most of the time-windows. For example, at the window of 1800 s, both of them have more than 93% for accuracy and F1-score. Feature importance analysis indicates that anomaly-based indicators such as ARP reply count were significant in classification.

- Random Forest: This model works almost similar in accuracy and recall as SVM in mid-to-large time-windows, but it consumes a lot more RAM and takes up a much larger model size. Therefore, it is not suitable for deployment in resource-constrained IoT devices.

- Decision Tree: This model attained 92.6% accuracy at 1800s which was quite high. However, its recall was relatively low at 60 s and 390 s, and the model portrayed a high false negative rate. Thus, the model may result in undetected ARP spoofing attacks in smart systems.

- KNN: This model consistently did worse than tree-based models on all metrics. Distance-based similarity in high-dimensional feature space makes it ineffective for our application. Moreover, its recall did not exceed 80% even with bigger time-windows, showing it is unsuitable for ARP spoofing.

The confusion matrices in Figure 2 further corroborate these conclusions. XGBoost and CatBoost maintain a reasonable trade-off between false positives and false negatives across various time-window settings.

6.2. Impact of Time-Window Selection

The selection of an appropriate time-window is a critical factor in ARP spoofing detection. Our results show:

- Short time-window (e.g., 60 s) captured transient anomalies, leading to higher recall but also increased false positives.

- Long time-window (e.g., 3000 s) resulted in smoother feature aggregation, improving precision but slightly reducing recall.

- Optimal time-window (1200 s–1800 s) achieved the best balance, maximizing F1-score while minimizing misclassifications.

Notably, precision continues to increase beyond 1800 s, reaching 0.98 at 3000 s; however, this is accompanied by a drop in recall and a growing discrepancy between training and testing accuracy. This pattern reflects a form of over-aggregation, where excessively large time-windows compress multiple behaviors into a single statistical profile. The resulting loss of temporal granularity reduces the diversity of training samples and may induce overfitting-like behavior, particularly in detecting short-lived or bursty ARP spoofing events.

This suggests that the adaptive time-window mechanism may help to dynamically adjust to changing network conditions. However, according to the authors’ timesheet, longer time-windows over 1800 s offer diminishing returns and risk degrading detection robustness due to temporal over-aggregation.

6.3. Computational Efficiency Considerations

Because of the constraints on IoT devices, efficiency is a key factor in model selection. Table 7, Figure 5 and Figure 6 show comparison of all those evaluated with respect to training time with inference latency and model size and RAM usage.

- Training Time: Random Forest and CatBoost required longer training times, but since training is an offline process, this is an acceptable trade-off.

- Inference Latency: Decision Tree exhibited the lowest inference latency, making it highly suitable for real-time deployment.

- Model Size: Random Forest had the largest model size across all evaluated models; however, its size gradually decreased as the time-window increased, suggesting that deeper trees were pruned or simplified over time.

- RAM Usage: All models showed an increase in RAM usage as the time-window expanded, eventually converging to similar levels. This reflects the growing volume of features and data being processed, which imposes constraints on edge deployment scenarios.

6.4. Comparison with Existing Research

Compared to traditional ARP spoofing detection approaches, our method presents several key advantages:

- Most existing research has focused on detection without considering resource constraints. We explicitly evaluate models under single-core execution and report inference latency, RAM usage, and model size in addition to accuracy, precision, recall, and F1.

- ACI-IoT-2023 originally lacked extracted ARP spoofing features. We reconstruct ARP-layer labels from PCAPs and introduce ARP-specific link-layer indicators, improving dataset usability for supervised learning and reproducible benchmarking.

- We model ARP spoofing as a time-based process and choose the aggregation window to reflect typical spoofing persistence, turning window selection from ad hoc sweeps into an explainable, repeatable setting suitable for constrained devices.

- The approach is lightweight, operating on link-layer headers and timing only, which complements infrastructure/heuristic defenses (e.g., DAI/SDN, entropy, or binding checks) where uniform controls or agents are unavailable.

These contributions mark a significant step toward practical ARP spoofing detection in IoT networks.

6.5. Limitations

Although the results are promising, there are limitations with our study:

- Dataset Scope: The ACI-IoT-2023 dataset is adopted for effectively enhancing ARP spoofing detection. However, it must be noted that it may not cover all varieties of IoT network environments. Real-world adversarial conditions may impact the generalizability of the model. Moreover, it is likely that the dataset only contains a subset of all possible ARP spoofing attack types. Future testing can be conducted on bigger, diverse datasets for improved robustness.

- Computational Constraints: The results show that the application of machine learning for ARP spoofing detection can be achieved under a single-core execution environment with RAM usage below 512MB, making it feasible for IoT applications. The inference latency of the models varies and some algorithms such as KNN take a heavier toll. Models like CatBoost and XGBoost offer a good balance between efficiency and outcome, though some optimization could be necessary for extreme edge devices.

- Lack of Real-Time Adaptive Mechanisms: Our models rely on predefined time-window for feature extraction, which might not adapt to changing conditions in the network. An alternate way that is more adaptive can be including a real-time anomaly detection or dynamically modulating the feature aggregation.

- Security Issues: The machine learning models can be tricked by attackers who subtly change network data to avoid detection using various techniques. Improving resilience against malicious samples and looking into counteractive measures, impediments, or challenges is a significant area of research.

- Data Reliability and Noise Sensitivity: Our windowed ARP features assume reasonable data quality, yet IoT traffic may include isolated/burst noise, drift, or dropouts that bias window statistics and classification. In LANs, device churn (join/leave), DHCP renewals, broadcast storms, port scans, varying host counts, or wireless interference can inflate ARP replies or unique MAC–IP mappings and trigger spurious requests. Related work [59,60,61] on data reliability assessment and analytics motivates this.

Through acknowledgment of these limitations, we highlight the importance of further research into improving the adaptability, computational efficiency as well as the security of the machine learning-based ARP spoofing detection for IoT networks.

7. Conclusions

This study proposed a machine-learning-based framework for ARP spoofing detection in IoT networks. We addressed a critical limitation of ACI-IoT-2023, namely the lack of ARP-specific feature extraction and labels, by introducing a tailored feature-engineering pipeline and labeling procedure. Our empirical analysis leads to the following findings:

- Effectiveness of Gradient Boosting: Across the evaluated time-window, XGBoost and CatBoost consistently delivered the strongest accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, reflecting their ability to capture non-linear interactions among windowed ARP features. Confusion matrices indicate reduced false positives and false negatives compared with Decision Tree, Random Forest, and KNN.

- Time-Window Selection Matters: Performance generally improves as the time window grows, but only up to a point. We observed diminishing returns and early signs of overfitting beyond roughly 1800 s. Small time-windows (e.g., 60 s) can increase recall at the expense of more false positives, whereas very large time-windows (e.g., 3000 s) may increase precision yet miss short-lived attacks. A balanced window in the range of 1200–1800 s offered the best trade-off between responsiveness and robustness in our setting.

- Computational Trade-offs: Ensemble models (Random Forest, XGBoost, and CatBoost) improved detection but incurred higher memory footprints and larger model sizes than a single Decision Tree. Decision Tree remained the most lightweight with competitive accuracy, while KNN showed the slowest inference and the weakest classification performance, making it unsuitable for real-time detection.

- Feasibility on Constrained Devices: All models were evaluated under a single-core CPU constraint. Peak RAM usage remained below 512 MB as measured in our emulated edge environment (QEMU, single-core ARM ≈ 1.0 GHz, 512 MB RAM, no GPU, OpenWrt). We use 512 MB as a practical benchmark for lightweight feasibility rather than a hard cap; models exceeding this footprint typically target higher-performance IoT gateways or edge nodes.

- Advancing ARP Spoofing Research: The proposed ARP-oriented feature set—centered on time-windowed rates, inter-arrival statistics, MAC–IP inconsistency patterns, and reply counts—improves classification over traditional threshold-based tool (e.g., Arpwatch, and ArpON), which often suffer from elevated false alarms due to fixed rules.

- Enhancing ACI-IoT-2023: We augment ACI-IoT-2023 by deriving ARP-specific labels and engineered features (e.g., ARP reply count, and rolling aggregates), thereby making the dataset more suitable for reproducible ARP spoofing research and comparative evaluation.

In summary, machine learning substantially strengthens ARP spoofing detection for IoT when models are evaluated jointly on detection quality and computational efficiency. Future work will focus on robustness against adversarial manipulation, online adaptation (e.g., drift-aware models), real-time mitigation integration, and validation across diverse IoT verticals and hardware profiles, including federated or privacy-preserving training at the edge.

8. Future Work

Even though our paper establishes a base for machine learning-based ARP spoofing detection for IoT environments, we believe that there is still a lot of scope for future work.

- Optimizing Computational Efficiency for IoT Edge Devices: Our models run on one core and use less than 512MB of RAM, but we still require more optimization for IoT. The models should greatly focus on optimization through compression techniques such as quantization and pruning to reduce computational cost. Deployment of the models through TinyML frameworks such as TensorFlow Lite or ONNX Runtime and use of hardware acceleration (ARM NEON, NPU, and TPU) for efficient real-time inference operations should be conducted.

- Developing Adaptive and Real-Time Detection Mechanisms: The present method applies constant timeframes to collate features, which may not adjust appropriately to dynamic behavior of networks. Further research may investigate the selection of dynamic time-windows based on spatial–temporal correlation of features. Detection schemes based on reinforcement learning might also self-adjust. Also, combinations of rule-based detections of anomalies with the application of models from machine learning result in flexibility and robustness.

- Enhancing Security Against Adversarial Attacks: Employ adversarial training techniques like FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method) and PGD (Projected Gradient Descent) to enhance defenses against evasion attacks. Future systems could incorporate specific mechanisms for detecting adversarial examples, leveraging zero-trust networking principles that could minimize exposure to spoofing at the architecture level.

- Deployment and Integration with Existing Security Frameworks: Future works can explore integration of systems within IoT security platforms for realism. This involves embedding the detection system into Software-Defined Networking (SDN) controllers for policies enforcement, extending well-established IDS like Suricata or Snort with ARP spoofing modules, and conducting field tests on edge hardware platforms like Raspberry Pi or NVIDIA Jetson Nano to assess deployment feasibility and performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-M.Y., J.-N.L. and K.-C.C.; methodology, Y.-M.Y. and J.-N.L.; software, Y.-M.Y.; validation, Y.-M.Y. and J.-N.L.; formal analysis, Y.-M.Y.; investigation, Y.-M.Y. and J.-N.L.; resources, J.-N.L. and K.-C.C.; data curation, Y.-M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-M.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.-N.L. and K.-C.C.; visualization, Y.-M.Y.; supervision, J.-N.L. and K.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan under Grant NSTC 113-2221-E-606-012, NSTC 114-2634-F-004-002-MBK, and in part by the National Defense Advanced Science Technology Research Program of Taiwan under Grant 114F114014.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are publicly available from IEEE Dataport at https://dx.doi.org/10.21227/qacj-3x32 (reference number: qacj-3x32).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from “The National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan” and “The National Defense Advanced Science Technology Research Program of Taiwan”, which made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1 provides a detailed description of extracted ARP spoofing features.

Table A1.

Detailed description of extracted ARP spoofing features.

Table A1.

Detailed description of extracted ARP spoofing features.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Timestamp () | The exact time when the ARP packet was captured. |

| Source MAC Address () | The MAC address of the sender in the ARP packet. |

| Destination MAC Address () | The MAC address of the intended receiver in the ARP packet. |

| Source IP Address () | The IP address of the sender in the ARP request or reply. |

| Destination IP Address () | The target IP address in the ARP request or reply. |

| ARP Opcode () | The operation type: 1 for request, 2 for reply. |

| Connection Type | Indicates whether the packet originated from a wired or wireless network, derived from the PCAP filename. |

| Label | Classification of the ARP packet: benign or ARP spoofing, based on attack timestamps from the dataset’s timesheet. |

Appendix A.2

Table A2 provides a detailed description of computed ARP spoofing features.

Table A2.

Detailed description of computed ARP spoofing features.

Table A2.

Detailed description of computed ARP spoofing features.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Ratio of ARP requests to replies within a fixed window. High values may indicate abnormal request flooding. | |

| Number of unique MAC addresses mapped to the same IP in a time-window, detecting MAC spoofing. | |

| Number of unique IPs associated with a single MAC in a time-window, useful for detecting ARP poisoning. | |

| ARP packet frequency in a specific time-window. | |

| Mean time interval between consecutive ARP packets. | |

| Standard deviation of ARP packet intervals, useful for detecting inconsistent ARP patterns. | |

| Count of ARP reply packets observed in a time-window. |

Appendix A.3

Table A3 summarizes the hyperparameters used in all experiments.

Table A3.

Hyperparameters for models.

Table A3.

Hyperparameters for models.

| Model | Hyperparameters in Our Experiment |

|---|---|

| Decision Tree | max_depth = 12 |

| Random Forest | n_estimators = 200; max_depth = 12; min_samples_split = 3 |

| XGBoost | n_estimators = 300; max_depth = 8; learning_rate = 0.05 |

| CatBoost | iterations = 300; depth = 8; learning_rate = 0.05; verbose = 0 |

| KNN | n_neighbors = 5 |

Appendix A.4

Table A4 summarizes the hyperparameters definitions.

Table A4.

Hyperparameter definitions.

Table A4.

Hyperparameter definitions.

| Hyperparameter | Definition (Role/Typical Effect) |

|---|---|

| n_estimators | Number of trees/boosting rounds. More rounds increase capacity and stability up to diminishing returns; larger models and longer training. |

| max_depth | Maximum depth of a tree. Caps model complexity and path length; deeper trees fit finer patterns but may overfit and grow size/latency. |

| min_samples_split | Minimum samples required to split a node (trees). Higher values regularize (shallower trees), lower values allow finer splits. |

| learning_rate | Boosting step size (shrinkage). Smaller values improve generalization but require more rounds to reach similar accuracy. |

| iterations | Total boosting iterations (CatBoost). Equivalent to n_estimators; increases capacity and training cost. |

| depth | Tree depth in CatBoost (oblivious trees). Controls interaction order captured; larger values increase expressiveness and variance. |

| n_neighbors | Number of neighbors in KNN. Smaller k = lower bias/higher variance (sensitive); larger k = smoother but may miss minority patterns. |

| verbose | Training log level (e.g., CatBoost). Affects output only; no impact on learned model. |

References

- Bala, B.; Behal, S. AI techniques for IoT-based DDoS attack detection: Taxonomies, comprehensive review and research challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 52, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafin, S.S.; Karmakar, G.; Mareels, I. Obfuscated Memory Malware Detection in Resource-Constrained IoT Devices for Smart City Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.A.; Hasan, M.K.; Alkhayyat, A.; Islam, S.; Sharma, R.; Alkwai, L.M. False data injection attack in smart grid cyber physical system: Issues, challenges, and future direction. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 107, 108638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, N.; Bierbrauer, D.; McKenzie, M.; Nack, E. ACI IoT Network Traffic Dataset 2023. 2023. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/documents/aci-iot-network-traffic-dataset-2023 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Forrest, S.; Hofmeyr, S.A.; Somayaji, A.; Longstaff, T.A. A sense of self for unix processes. In Proceedings of the 1996 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 6–8 May 1996; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.F.; Hsu, Y.F.; Lin, C.Y.; Lin, W.Y. Intrusion detection by machine learning: A review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 36, 11994–12000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczak, A.L.; Guven, E. A Survey of Data Mining and Machine Learning Methods for Cyber Security Intrusion Detection. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 1153–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarpelao, B.B.; Miani, R.S.; Kawakani, C.T.; de Alvarenga, S.C. A survey of intrusion detection in the Internet of Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 84, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabouni, N.; Mosbah, M.; Zemmari, A.; Sauvignac, C.; Faruki, P. Network intrusion detection for IoT security based on learning techniques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2671–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staddon, E.; Loscri, V.; Mitton, N. Attack categorisation for IoT applications in critical infrastructures: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nack, E.A.; McKenzie, M.C.; Bastian, N.D. ACI-IoT-2023: A Robust Dataset for Internet of Things Network Security Analysis. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2024–2024 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), Washington, DC, USA, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.E. An Intrusion-Detection Model. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1987, SE-13, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, M. Snort: Lightweight Intrusion Detection for Networks. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Systems Administration Conference (LISA ’99), Seattle, WA, USA, 7–12 November 1999; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson, V. Bro: A System for Detecting Network Intruders in Real-Time. In Proceedings of the 7th USENIX Security Symposium, San Antonio, TX, USA, 26–29 January 1998; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Patcha, A.; Park, J.M. An Overview of Anomaly Detection Techniques: Existing Solutions and Latest Trends. Comput. Netw. 2007, 51, 3448–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddabachigari, S.; Abraham, A.; Grosan, C.; Thomas, J. Modeling intrusion detection system using hybrid intelligent systems. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2007, 30, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.J.; Lin, C.H.R.; Lin, Y.C.; Tung, K.Y. Intrusion Detection System: A Comprehensive Review. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2013, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.H.; Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. Network anomaly detection: Methods, systems and tools. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Hu, J.; Slay, J. A Holistic Review of Network Anomaly Detection Systems: A Comprehensive Survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 128, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. Network Anomaly Detection: A Machine Learning Perspective; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 1–219. ISBN 978-1439839439. [Google Scholar]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folino, G.; Sabatino, P. Ensemble based collaborative and distributed intrusion detection systems: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 66, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, R.; Apthorpe, N.; Feamster, N. Machine learning ddos detection for consumer internet of things devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE security and privacy workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24 May 2018; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkamala, S.; Janoski, G.; Sung, A. Intrusion Detection Using Neural Networks and Support Vector Machines. In Proceedings of the 2002 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–17 May 2002; Volume 2, pp. 1702–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, C.; Zhu, Y.; Fei, J.; He, X. A Deep Learning Approach for Intrusion Detection Using Recurrent Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 21954–21961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Maglaras, L.; Moschoyiannis, S.; Janicke, H. Deep learning for cyber security intrusion detection: Approaches, datasets, and comparative study. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2020, 50, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albulayhi, K.; Abu Al-Haija, Q.; Alsuhibany, S.A.; Jillepalli, A.A.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Sheldon, F.T. IoT intrusion detection using machine learning with a novel high performing feature selection method. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikissagbe, B.R.; Adda, M. Machine Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Methods in IoT Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Han, F.; Cao, J.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S. Cloud computing-based forensic analysis for collaborative network security management system. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2013, 18, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Paxson, V. Outside the Closed World: On Using Machine Learning for Network Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the 31st IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, USA, 16–19 May 2010; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson, S. The base-rate fallacy and the difficulty of intrusion detection. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. (TISSEC) 2000, 3, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Hu, L.; Hou, Y.; Li, X. A lightweight intelligent network intrusion detection system using one-class autoencoder and ensemble learning for IoT. Sensors 2023, 23, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihan, S.D.A.; Anbar, M.; Alabsi, B.A. Meta-Learner-Based Approach for Detecting Attacks on Internet of Things Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, J.; Azad, M.A.; Amad, R.; Salah, K.; Alazab, M.; Iqbal, R. A Review of Performance, Energy and Privacy of Intrusion Detection Systems for IoT. Electronics 2020, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanigaivelan, N.K.; Nigussie,, E.; Kanth, R.A.; Virtanen, S.; Isoaho, J. Distributed Internal Anomaly Detection System for the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2016 13th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zawish, M.; Davy, S.; Abraham, L. Complexity-driven model compression for resource-constrained deep learning on edge. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 3886–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayanan, M.; Simoens, P.; Xiao, Y.; Pillai, P.; Chen, Z.; Ha, K.; Hu, W.; Amos, B. Edge Analytics in the Internet of Things. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2015, 14, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothukuri, V.; Khare, P.; Parizi, R.M.; Pouriyeh, S.; Dehghantanha, A.; Srivastava, G. Federated-learning-based anomaly detection for IoT security attacks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Chai, W. Collaborative Learning for Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Grauman, K., Cesa-Bianchi, N., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Huang, W.; Long, J.; Zhang, K.; Li, K.C.; Zhang, D. Deep reinforcement learning for resource protection and real-time detection in IoT environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6392–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhareth, G.; Ilyas, M. Optimized Intrusion Detection for IoMT Networks with Tree-Based Machine Learning and Filter-Based Feature Selection. Sensors 2024, 24, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubhi, K.; Alharbi, F.; Alofi, A.; Alnefaie, E.; Shakshir, A.; Ghaleb, B. A Secured Intrusion Detection System for Mobile Edge Computing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, H.; Belguith, S.; Alhomoud, A.; Jemai, A. A survey of IoT security based on a layered architecture of sensing and data analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Gomez, K.; Sithamparanathan, K.; Asghar, M.R.; Russello, G.; Zanna, P. Mitigating DDoS Attacks in SDN-Based IoT Networks Leveraging Secure Control and Data Plane Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolfo, S.; Fan, W.; Lee, W.; Prodromidis, A.; Chan, P. KDD Cup 1999 Data. UCI Machine Learning Repository. 1999. Available online: https://kdd.ics.uci.edu/databases/kddcup99/kddcup99.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Tavallaee, M.; Bagheri, E.; Lu, W.; Ghorbani, A.A. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 8–10 July 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroniotis, N.; Moustafa, N.; Sitnikova, E.; Turnbull, B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the internet of things for network forensic analytics: Bot-iot dataset. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Manzanares, A.; Medina-Galindo, J.; Bahsi, H.; Nõmm, S. MedBIoT: Generation of an IoT Botnet Dataset in a Medium-sized IoT Network. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy - ICISSP. INSTICC, Valletta, Malta, 25–27 February 2020; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindy, H.; Tachtatzis, C.; Atkinson, R.; Bayne, E.; Bellekens, X. Mqtt-iot-ids2020: Mqtt internet of things intrusion detection dataset. IEEE Dataport 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward Generating a New Intrusion Detection Dataset and Intrusion Traffic Characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP), Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Parmisano, A.; Erquiaga, M.J. IoT-23: A Labeled Dataset with Malicious and Benign IoT Network Traffic. 2020. Available online: https://www.stratosphereips.org/datasets-iot23 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Bruschi, D.; Ornaghi, A.; Rosti, E. S-ARP: A secure address resolution protocol. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, Vegas, NV, USA, 8–12 December 2003; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco Systems. Understanding and Configuring Dynamic ARP Inspection. Technical Report, Cisco Technical Documentation. 2019. Available online: https://www.cisco.com (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Ramachandran, A.; Nandi, S. Detecting ARP Spoofing: An Active Technique. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems Security (ICISS), Kolkata, India, 19–21 December 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Dash, C. Detecting and Preventing ARP Spoofing Attacks Using Real- Time Data Analysis and Machine Learning. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 2347–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Deb Barma, M.K.; Saha, A. ARP Spoofing Detection Using Machine Learning Classifiers: An Experimental Study. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2023, 67, 727–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, H.; Al-Raweshidy, H.; S Awad, W. ARP spoofing detection for IoT networks using neural networks. In Proceedings of the Industrial Revolution & Business Management: 11th Annual PwR Doctoral Symposium (PWRDS), Manama, Bahrain, 13 August 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Sun, Y.; Fu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Ma, X.; Zheng, K.; Huang, X. ARP poisoning prevention in Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th international conference on information technology in medicine and education (ITME), Hangzhou, China, 19–21 October 2018; pp. 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafin, S.S.; Karmakar, G.; Mareels, I.; Balasubramanian, V.; Kolluri, R.R. Sensor Self-Declaration of Numeric Data Reliability in Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2025, 74, 2751–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Yang, K.; Ran, P.; He, S.; Chen, J. Reliable evaluation for the AI-enabled intrusion detection system from data perspective. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0334157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodeji, A.; Liu, Y.-k.; Chao, N.; Yang, L.-q. A new perspective towards the development of robust data-driven intrusion detection for industrial control systems. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2020, 52, 2687–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).