Enabling Reliable Freshwater Supply: A Review of Fuel Cell and Battery Hybridization for Solar- and Wind-Powered Desalination

Abstract

1. Introduction

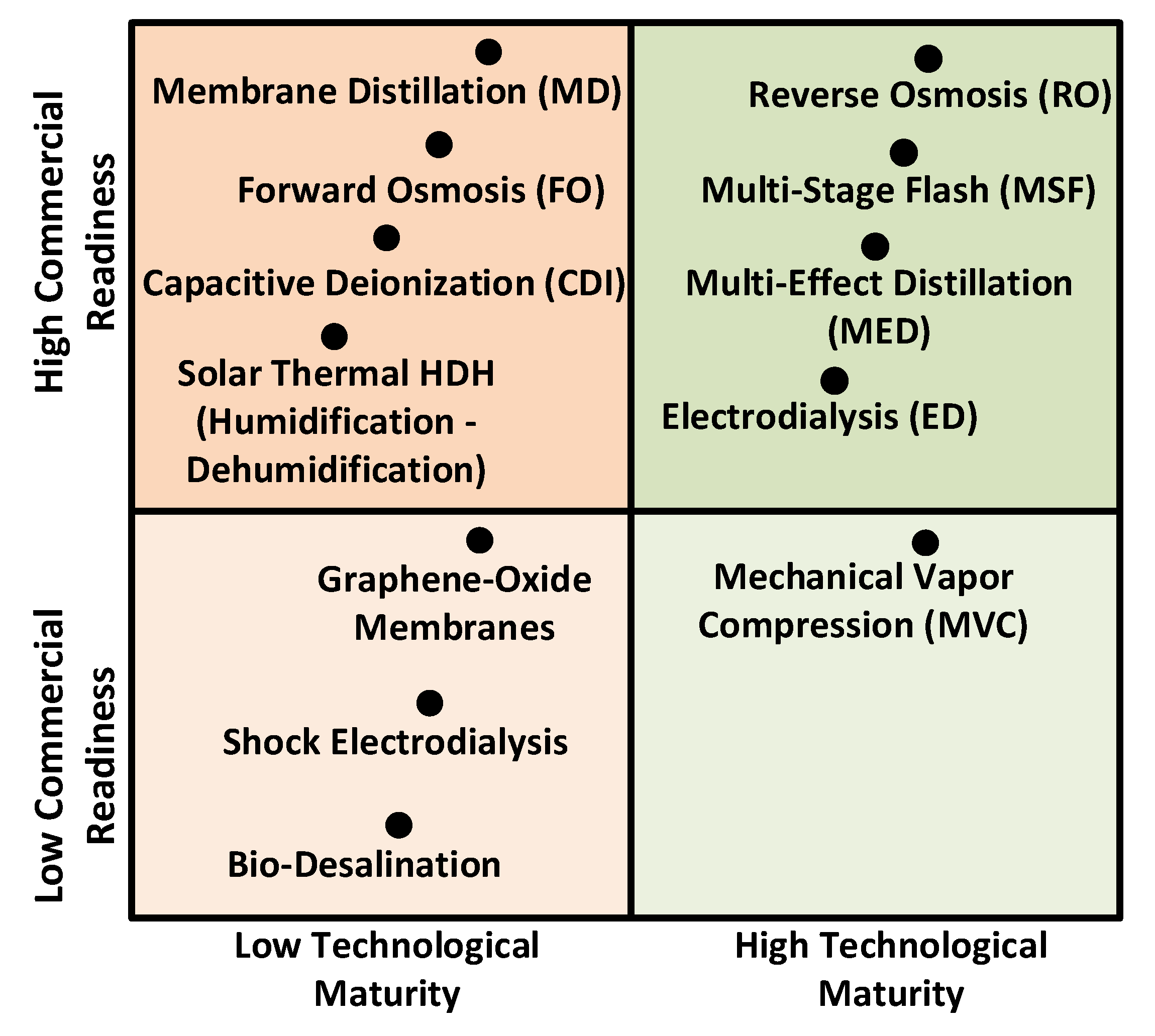

2. Desalination Technologies

2.1. Established Processes

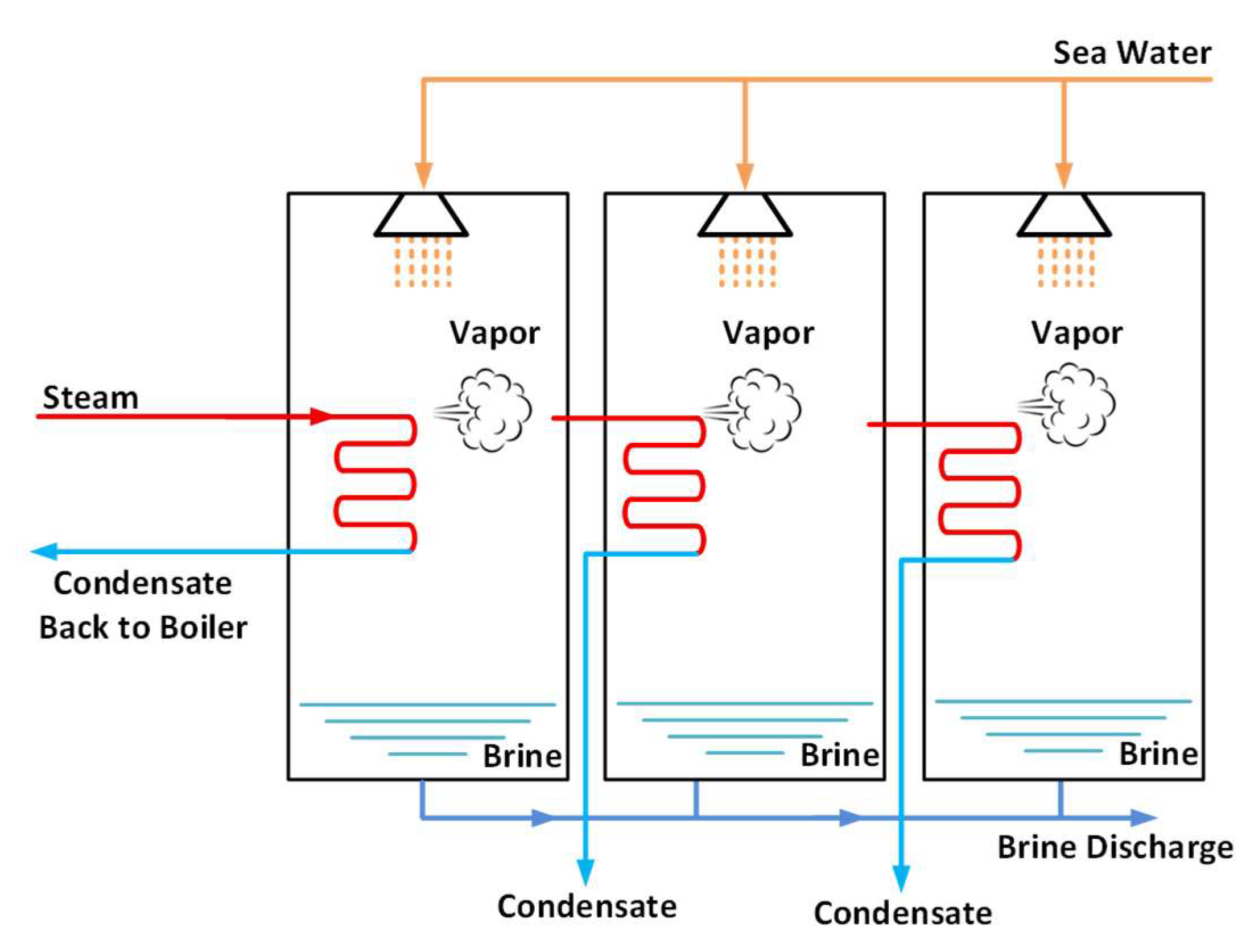

2.1.1. Multi-Effect Distillation (MED)

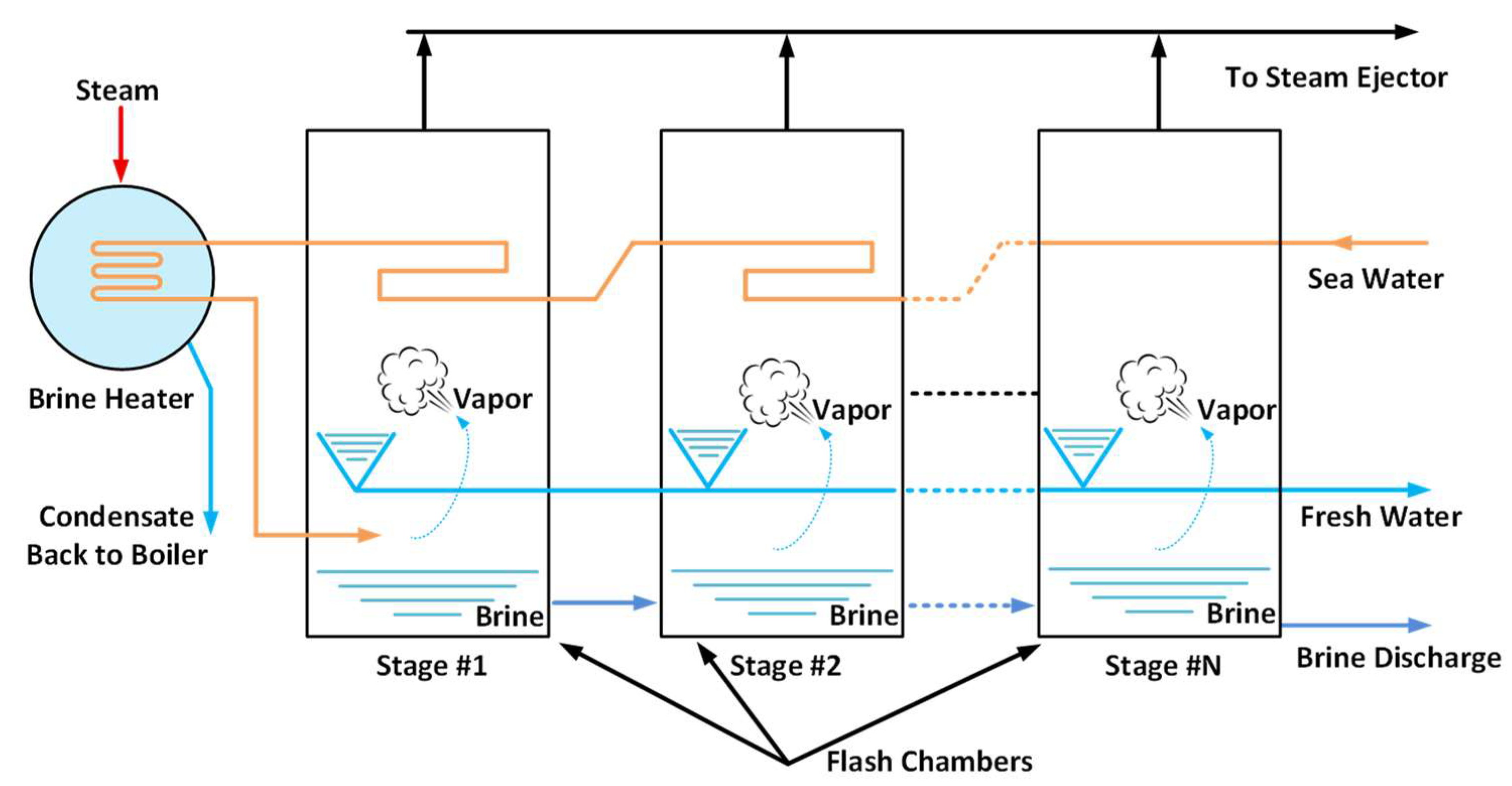

2.1.2. Multi-Stage Flash (MSF)

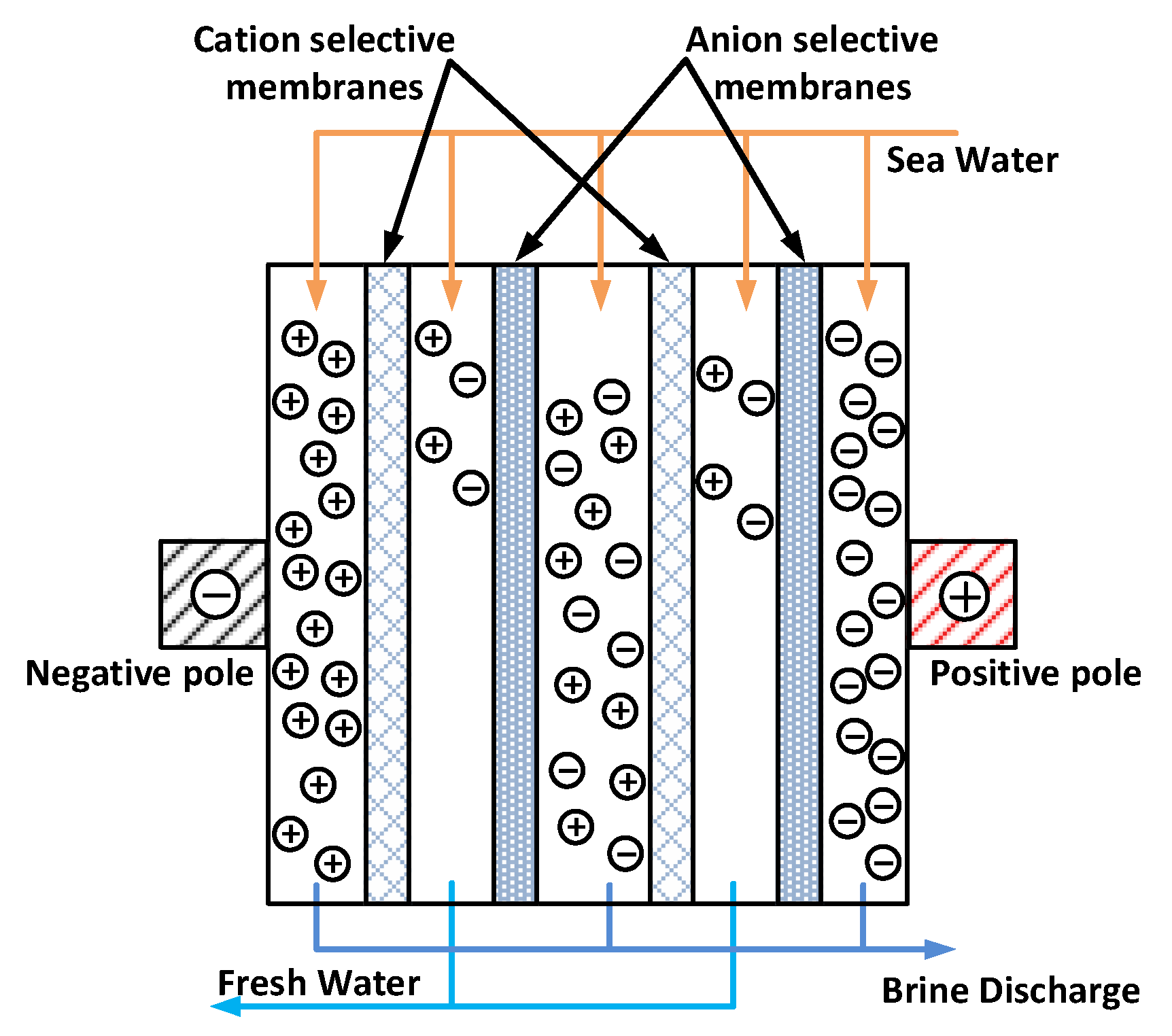

2.1.3. Electrodialysis (ED)

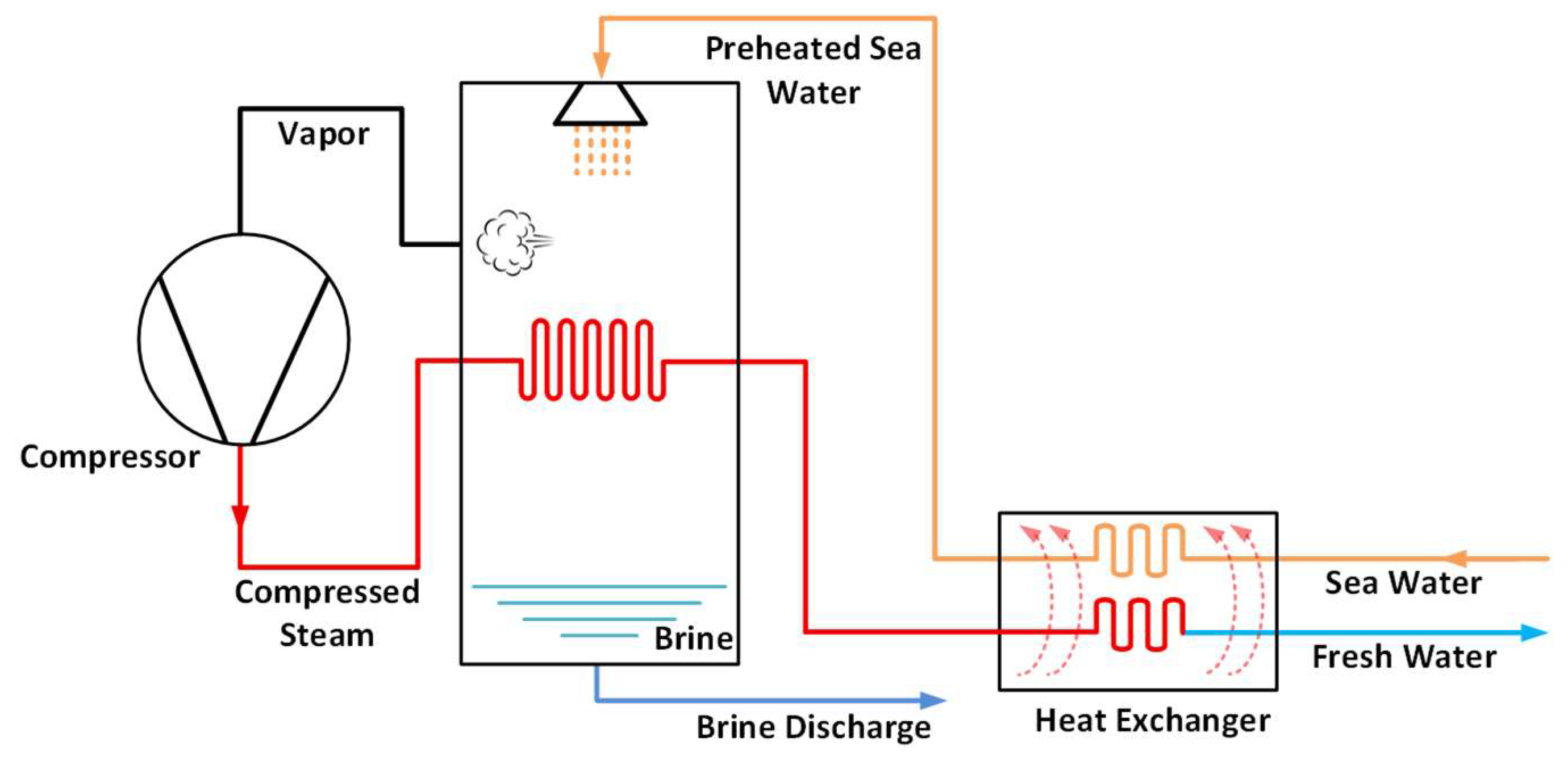

2.1.4. Mechanical Vapor Compression (MVC)

2.1.5. Reverse Osmosis (RO)

2.2. Emerging Processes

2.2.1. Molecular Sieving by Graphene Oxide

2.2.2. Shock Electrodialysis (SED)

2.2.3. Forward Osmosis (FO)

- Thermal separation is used for volatile solutes like ammonia-carbon dioxide;

- Membrane distillation, which uses low-grade heat to evaporate water from the diluted draw solution, is effective for a range of solutes, leaving behind the reconcentrated solute;

- Nanofiltration (NF) or low-pressure RO, particularly for recovery of non-volatile ionic draw solutes like sodium chloride (NaCl) or magnesium sulfate (MgSO4).

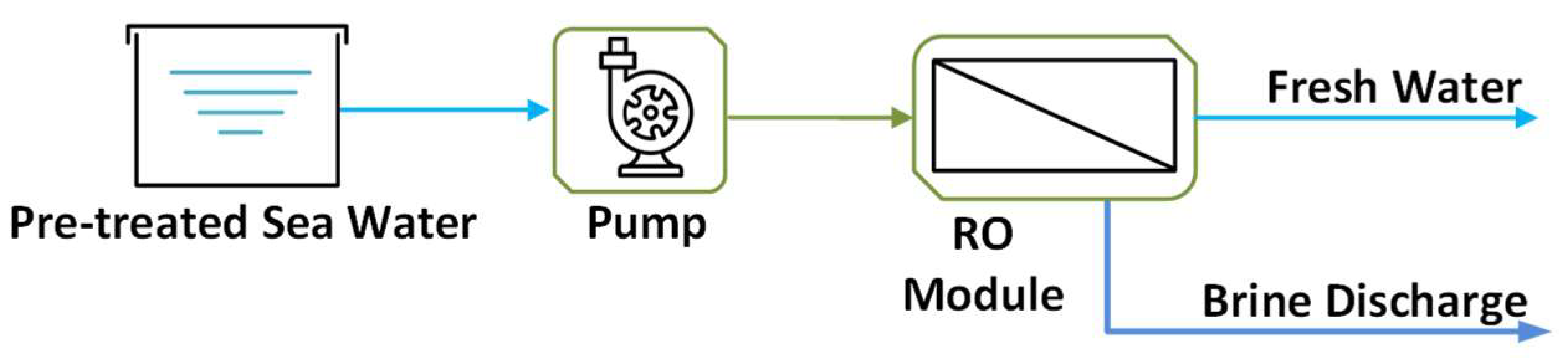

2.3. RES-Powered Desalination Systems

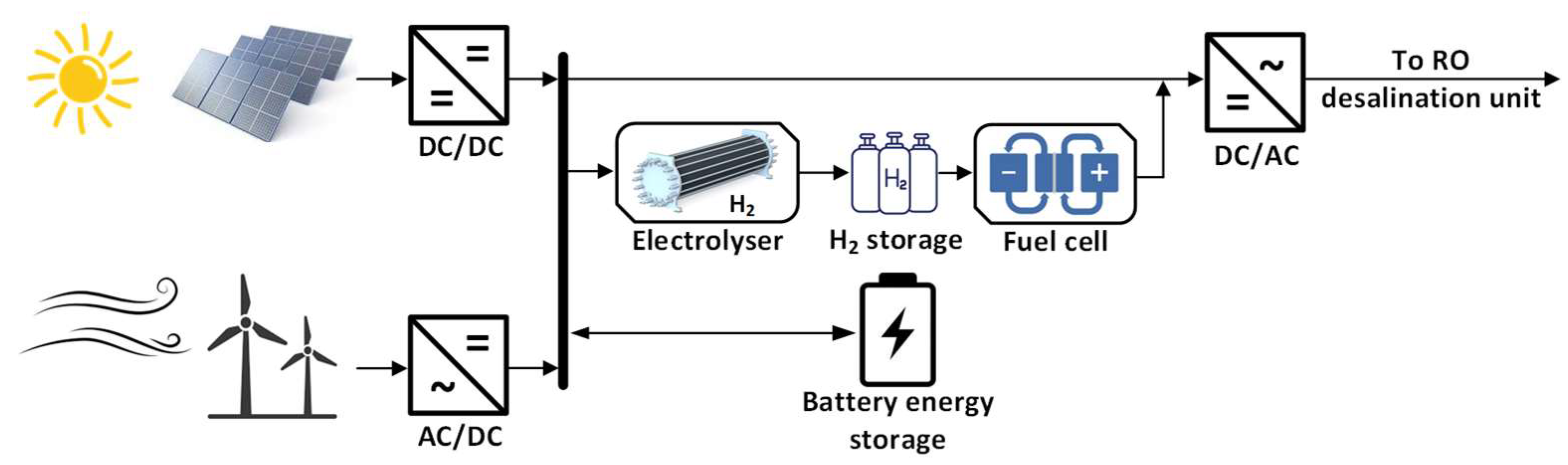

3. Battery Energy Storages

3.1. Lead-Acid Batteries

- Flooded (Vented) Lead-Acid (FLA): The traditional design where the electrolyte is in liquid form and requires periodic maintenance (topping up with distilled water) to compensate for water loss due to electrolysis and evaporation [66]. They are robust and low-cost but require ventilation due to gas emission during charging.

- Valve-Regulated Lead-Acid (VRLA): Sealed batteries that recombine internally generated gases, eliminating the need for watering.

- Absorbent Glass Mat (AGM): Uses a fiberglass mat to absorb the electrolyte, making it spill-proof, resistant to vibration, and capable of delivering high currents. It has a low self-discharge rate and is suitable for applications requiring reliability with minimal maintenance.

- Gel: The electrolyte is gelled with silica, which immobilizes it. These batteries are highly resistant to shock, vibration, and deep discharges, and have a very low self-discharge rate. However, they are sensitive to overcharging and require careful charge voltage control.

3.2. Lithium-Ion Batteries

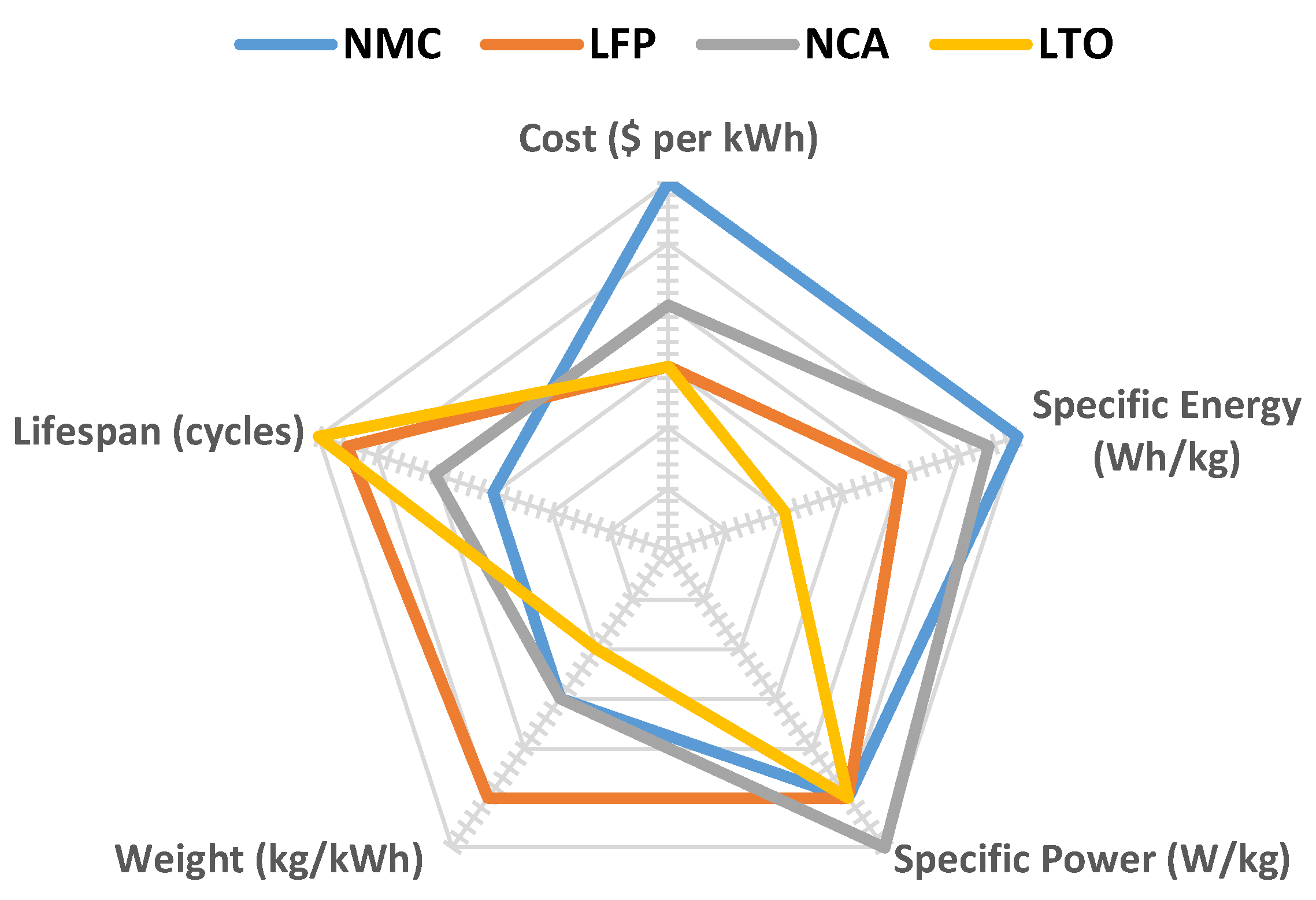

- Lithium Titanate Oxide (LTO): Represents a unique lithium-ion chemistry that replaces the traditional graphite anode with one made of lithium titanate. This fundamental change grants LTO exceptional advantages, most notably extremely fast charging, a very long cycle life, and superior safety due to its high thermal stability and elimination of lithium plating [70]. However, these benefits come at the cost of lower energy density and a higher upfront cost compared to NMC or LFP batteries. LTO is ideally suited for applications where reliability, rapid cycling, and safety are paramount, such as in public transportation buses, and grid frequency regulation.

- Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC): Offers a balance of energy density, cycle life, and cost. Its cathode blends nickel, manganese, and cobalt, offering greater stability and longer cycle life than NCA variants, though at a slightly lower energy density [71]. NMC batteries are prevalent in electric vehicles, power tools, and renewable energy storage due to their reliability [72]. Widely used in medium- to large-scale energy storage.

- Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide (NCA): High specific energy and good longevity but requires careful thermal management. Its cathode combines nickel for reversibility, cobalt for stability, and aluminum to reduce structural stress during cycling. NCA batteries offer high energy and power density, making them suitable for electric vehicles and power tools [73]. Common in grid storage and automotive applications.

- Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP): Distinguished by its exceptional safety, long cycle life, and stability. Though lower in energy density than NMC or NCA, its operational safety and durability is high [74]. These batteries are particularly well-suited for renewable energy-powered RO desalination due to their safety, long cycle life, and cost-effectiveness. Their superior thermal stability reduces fire risk, a critical advantage in remote or arid locations, while their ability to endure frequent charging and discharging aligns perfectly with solar or wind intermittency. Although LFP has a lower energy density than NMC and NCA resulting in larger battery banks, this is often an acceptable trade-off for stationary RO applications where space is less constrained than in vehicles (Figure 9). The technology’s main limitations, reduced performance in cold climates and difficulties in state-of-charge estimation due to its flat voltage curve, can be mitigated with proper system design, insulation, and advanced battery management software. The material composition of LFP batteries is more sustainable, leveraging abundant and non-toxic iron and phosphate. LTO batteries, however, depend on rarer titanium resources, creating potential supply constraints and a less favorable environmental footprint. For these reasons, LFP has become the leading storage choice for sustainable, off-grid, and hybrid-powered RO desalination systems.

3.3. Nickel-Based Batteries

- Nickel-Metal Hydride (Ni-MH): Ni-MH batteries represent an advanced class of nickel-based electrochemistry, distinguished by their replacement of toxic cadmium with a hydrogen-absorbing alloy. This key material change results in a more environmentally benign profile and a significant improvement in energy density over Nickel-Cadmium systems [77]. Ni-MH batteries offer several operational advantages, including a reduced susceptibility to the “memory effect,” a longer cycle life, and a lower self-discharge rate, which enables better charge retention over time. These characteristics, combined with their capability for high-power delivery, have established Ni-MH as the technology of choice for applications such as hybrid electric vehicles and high-drain portable power tools. However, for the continuous, high-cyclicity duty of supporting renewable-powered reverse osmosis desalination, their lower round-trip efficiency and energy density compared to modern lithium-ion alternatives often render them less optimal.

- Nickel-Cadmium (Ni-Cd): Ni-Cd batteries constitute another established nickel-based technology, characterized by their ability to deliver high power with a rapid discharge rate, making them suitable for applications such as power tools and emergency lighting. Their key operational advantages include a long cycle life, robustness in harsh environments, and stability in sealed, maintenance-free configurations, positioning them as a historical alternative to lead-acid batteries in demanding use cases [78]. However, these benefits are counterbalanced by significant drawbacks. Ni-Cd batteries are highly susceptible to the “memory effect,” which can permanently reduce usable capacity if not managed correctly, and they offer a shorter service life than Ni-MH equivalents. Most critically, the use of toxic cadmium raises serious environmental concerns, limiting their suitability for modern applications where environmentally benign alternatives are available.

4. Fuel Cell Technologies

4.1. Fuel Cell Role in Renewable-Powered Desalination

4.2. Fundamentals and Design Aspects Relevant to Coastal Plants

4.3. Technology Families and Their Fit for Desalination Duty

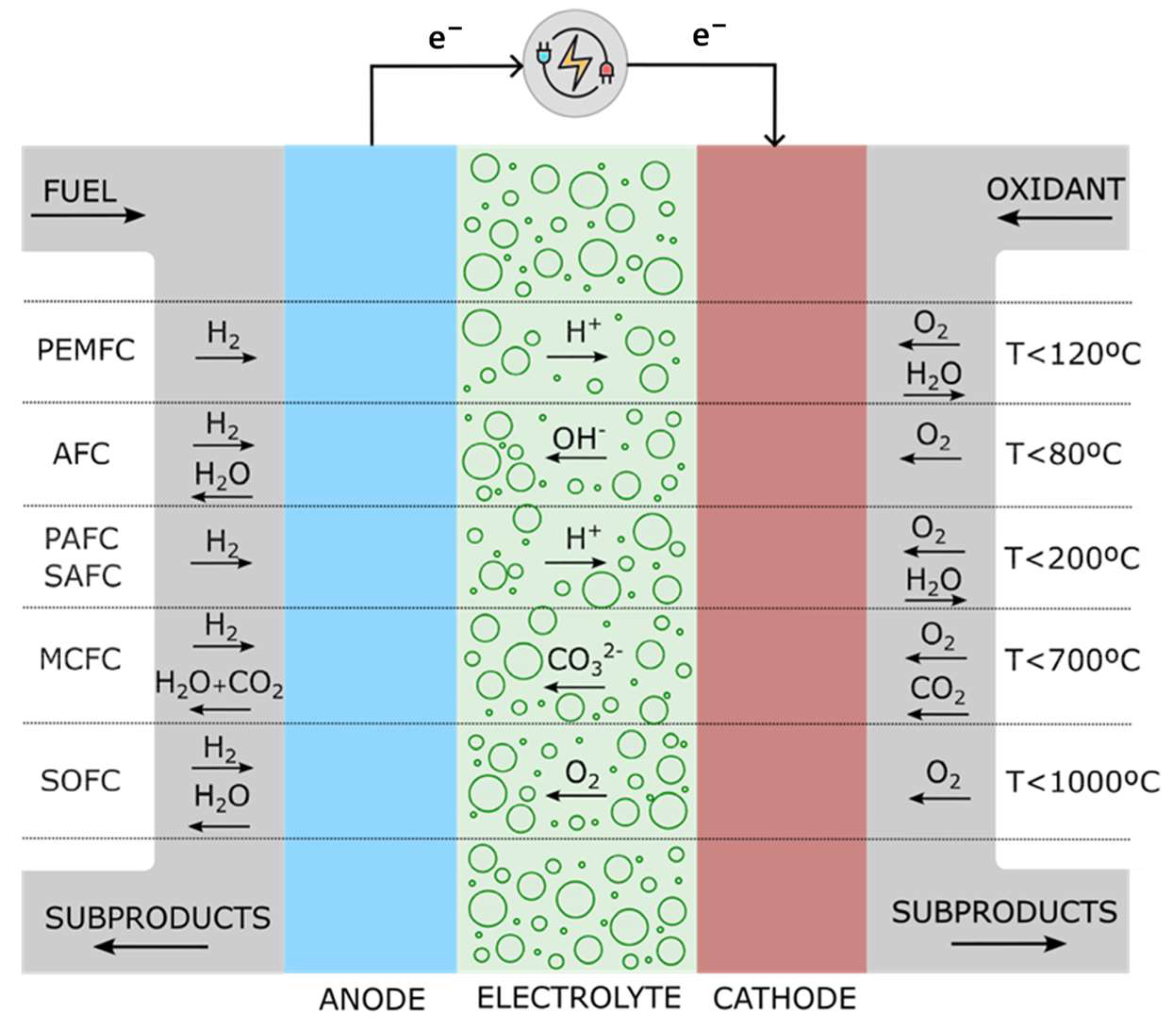

- Alkaline fuel cells (AFCs) use an aqueous alkaline electrolyte, typically potassium hydroxide. Electrodes are often composed of non-precious metals, with nickel-based catalysts being common for both the anode and cathode [85]. Hydroxide ions move from the cathode to the anode; at the anode, hydrogen reacts with OH− to form water and electrons, and at the cathode oxygen combines with water and electrons to regenerate OH−. The operating temperature is modest, usually around 60–80 °C, which simplifies thermal management and enables quick starts. The major drawback is sensitivity to carbon dioxide: CO2 in the air or in the fuel converts the electrolyte into carbonates and degrades performance. In a coastal, open-air setting, sensitivity is a serious design constraint unless CO2 scrubbing is provided [86]. AFCs can be effective in small, islanded RO plants, which are a typical case where very fast starts are valuable and frequent on/off cycles are required, provided CO2 levels can be controlled. Recent anion-exchange membrane variants aim to reduce CO2 uptake by replacing liquid KOH with a solid membrane, but these systems are less mature than polymer electrolyte fuel cells [87].

- Proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) employ a solid polymer electrolyte that conducts protons. Their electrodes require high activity at low temperatures, necessitating platinum or platinum-group metal (PGM) catalysts, typically supported on carbon, for both the anode and cathode. However, the reliance on these noble metals contributes significantly to the overall system cost and raises concerns about long-term resource sustainability and supply chain security. At the anode, hydrogen splits into protons and electrons; protons cross the membrane and combine with oxygen at the cathode to form water. PEMFCs operate near 60–80 °C, with high-temperature formulations reaching around 120 °C [88]. They are compact, respond rapidly to load changes, and start readily from cold, which makes them a natural partner for battery-smoothed RO operation. They are not affected by CO2 in air, but they require very clean hydrogen because the catalysts are sensitive to carbon monoxide, sulfur compounds, and ammonia [89]. The heat they produce is low-grade but still useful for feed preheating or low-temperature tasks. In most small to medium hybrid plants that prioritize operational simplicity and frequent cycling, PEMFCs provide the best overall match [90].

- Phosphoric acid fuel cells (PAFCs) and sulfuric acid variants use liquid acids as electrolytes, so the charge carrier is also the proton, but the operating window moves up to roughly 150–200 °C. At these temperatures, the stack yields a steadier flow of medium-grade heat, which can be absorbed by membrane distillation units, thermal pretreatment, or space and water heating within the facility. PAFCs are designed for stationary baseload operation; they ramp and start more slowly than PEMFCs and have lower power density, while still requiring noble-metal catalysts. They tolerate some impurities better than PEMFCs but remain sensitive to carbon monoxide and sulfur, so fuel quality control is still necessary [91].

- Solid Acid Fuel Cells (SAFCs) utilize a solid-state electrolyte, where the charge carrier is the proton. They operate in an intermediate temperature range of 200–300 °C. This temperature provides several key advantages: it yields useful waste heat for thermal processes, enhances tolerance to fuel impurities like carbon monoxide, and eliminates the need for noble-metal catalysts. While they offer improved stability and simpler water management compared to lower-temperature PEMFCs, their power density is typically lower, and a critical challenge remains maintaining stable performance by preventing dehydration or decomposition of the electrolyte phase [92].

- Molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFCs) operate much hotter, generally between 600 and 700 °C. The electrolyte is a molten carbonate salt held in a ceramic matrix. The mobile ionic species is CO32−, which forms at the cathode by reacting oxygen with carbon dioxide. Because carbonate ions carry charge, the cathode requires a controlled supply of CO2, which is usually recirculated from the anode exhaust. At the anode, hydrogen reacts with CO32− to produce water, CO2, and electrons [93]. High temperature brings several advantages: platinum-group metal catalysts are unnecessary, as nickel-based electrodes are sufficiently active, and the electrochemical reactions are highly efficient, leading to superior electrical conversion efficiency compared to lower-temperature fuel cells (LTFC). Critically, the high-grade heat is not merely a byproduct but a fundamental output that justifies the thermal investment. It represents a form of upgraded energy capable of performing thermodynamic work, such as driving thermal desalination processes or powering Rankine cycles for additional electricity. This creates a highly efficient cogeneration system where one unit of fuel input simultaneously produces both electricity and valuable thermal energy, a synergy that is more efficient than separate systems for power and heat generation. The primary operational trade-off for these advantages is a lack of dynamic responsiveness, the stacks are designed for long, steady campaigns and are poorly suited for frequent start-stop cycles or rapid load-following. Furthermore, the balance of plant must handle the challenges of hot, corrosive salt environments and complex CO2 logistics. Where the desalination complex is large and continuous, and thermally integrated, MCFCs can therefore deliver exceptional overall efficiency by maximizing both electrical and useful thermal output from the same unit of hydrogen fuel [94].

- Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) push the temperature envelope further. Their ceramic electrolytes, often yttria-stabilized zirconia, conduct oxide ions from cathode to anode. At the cathode, oxygen molecules accept electrons and become O2−; at the anode, hydrogen reacts with O2− to form water and release electrons back to the circuit [95]. Operating temperatures from approximately 600 °C to 1000 °C allow internal reforming and flexible fueling with clean natural gas, hydrogen, or syngas, without noble metals [96]. Like MCFCs, SOFCs are not designed for frequent thermal cycling; they are most comfortable in steady baseload service [97]. The quality of the heat they produce is exceptionally high. In desalination hubs that combine RO with thermal processes, SOFCs unlock cogeneration layouts that use the electrical output for high-pressure pumps and the thermal output for multi-effect or multi-stage systems, absorption chillers, or district heating and cooling that shares infrastructure with the water plant.

4.4. Hybridization with Batteries and Power Electronics

4.5. Integration Challenges and Mitigations in Coastal Deployment

4.6. Choosing the Right Fuel Cell for the Application

4.7. Thermal Management in Fuel Cell Systems

5. Energy Management Strategies

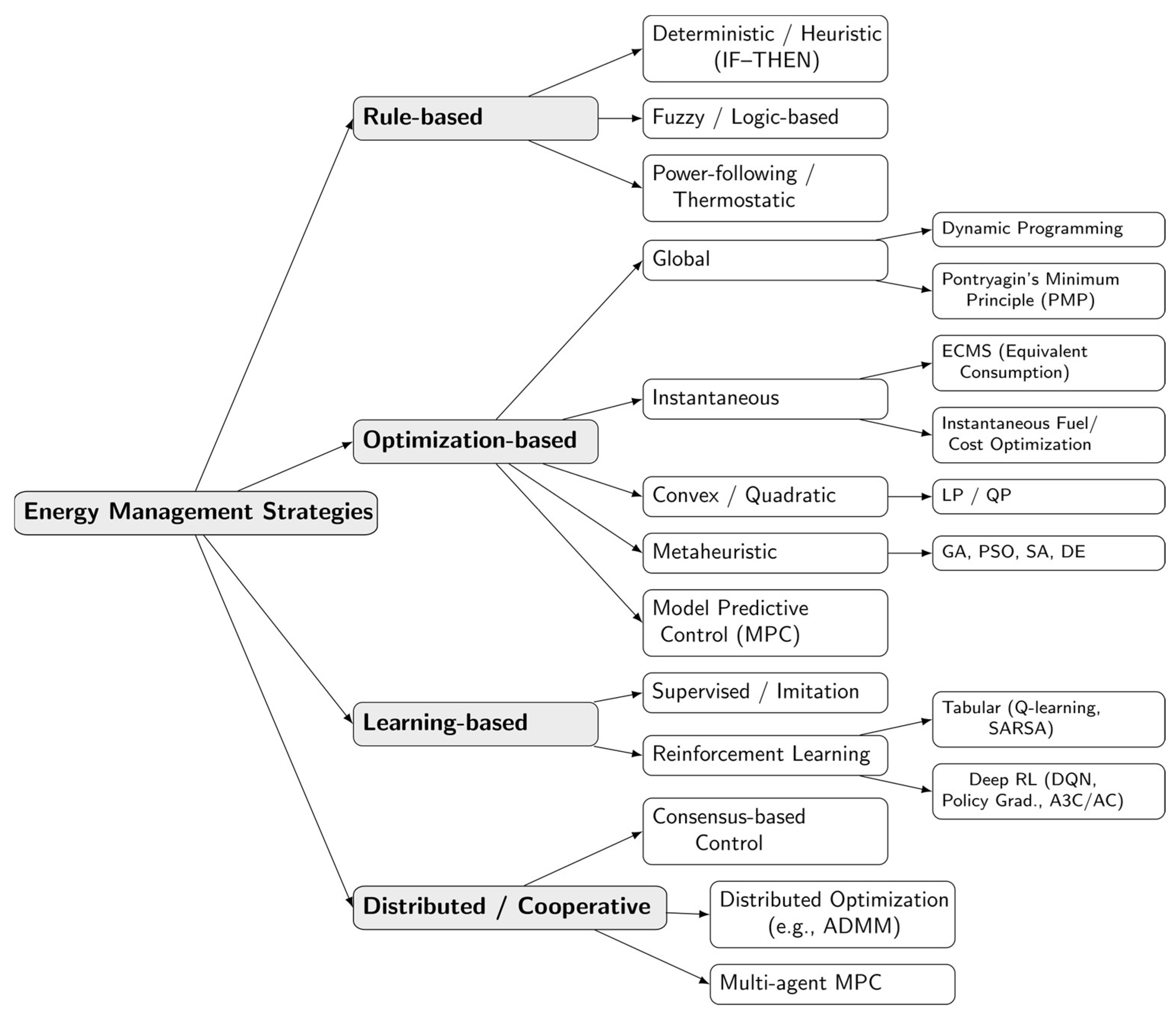

5.1. Rule-Based Strategies

5.1.1. Fuzzy Logic

5.1.2. Filter-Based Power Splitting

5.1.3. Finite-/Multi-State Logic

5.1.4. GA-Tuned Fuzzy and Neuro-Fuzzy (ANFIS)

5.2. Optimization-Based Strategies

5.2.1. Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (ECMS)

5.2.2. Dynamic Programming (DP)

5.2.3. Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle (PMP)

5.2.4. Model Predictive Control (MPC)

5.2.5. Convex/QP and Mixed-Integer Programming

5.2.6. Other Metaheuristics

5.2.7. Robust and Stochastic Optimization

5.2.8. Degradation-Aware Optimization

5.3. Learning-Based Strategies

5.3.1. Reinforcement Learning (RL)

5.3.2. Supervised Learning

5.4. Distributed and Cooperative Control

5.4.1. Consensus-Based Control

5.4.2. Distributed Optimization (ADMM)

5.4.3. Multi-Agent MPC

5.5. Selection Guidelines

5.6. State of Health Estimation for Degradation-Aware EMS

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMM | Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers |

| AEM | Anion-Exchange Membranes |

| AFC | Alkaline Fuel Cells |

| AGM | Absorbent Glass Mat |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Network-based Fuzzy Inference Systems |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| BHS | Battery–Hydrogen Storage |

| CAES | Compressed Air Energy Storage |

| CEM | Cation-Exchange Membranes |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| DoD | Depth of Discharge |

| DP | Dynamic Programming |

| ECMS | Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy |

| ED | Electrodialysis |

| EDR | Electrodialysis Reversal |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| ERD | Energy Recovery Devices |

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| FC | Fuel Cell |

| FLA | Flooded Lead-Acid |

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Control |

| FO | Forward Osmosis |

| GO | Graphene-Oxide |

| HESS | Hybrid Energy Storage System |

| ICP | Ion Concentration Polarization |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| LTFC | Low-Temperature Fuel Cell |

| LTO | Lithium Titanate Oxide |

| MCFC | Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells |

| MED | Multi-Effect Distillation |

| MG | Microgrid |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MSF | Multi-Stage Flash |

| MVC | Mechanical Vapor Compression |

| NCA | Nickel Cobalt Aluminum |

| NMC | Nickel Manganese Cobalt |

| P2D | Pseudo-Two-Dimensional |

| PAFC | Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells |

| PCM | Phase-Change Materials |

| PEMFC | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells |

| PGM | Platinum-Group Metal |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PHS | Pump Hydro Storage |

| PMP | Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| RT | Real Time |

| SED | Shock Electrodialysis |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| SOFC | Solid Oxide Fuel Cells |

| SOH | State of Health |

| SWRO | Seawater Reverse Osmosis |

| TVC | Thermal Vapor Compression |

| VFD | Variable Frequency Drives |

| VRLA | Valve-Regulated Lead-Acid |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

References

- National Ocean Service. Available online: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/wherewater.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Water for Life: Making it Happen. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43224 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Yang, S.-R.; Chen, X.-R.; Huang, H.-X.; Yeh, H.-F. Innovation in Water Management: Designing a Recyclable Water Resource System with Permeable Pavement. Water 2024, 16, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Vicidomini, M.; Calise, F.; Duić, N.; Østergaard, P.A.; Wang, Q.; da Graça Carvalho, M. Review of Hot Topics in the Sustainable Development of Energy, Water, and Environment Systems Conference in 2022. Energies 2023, 16, 7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.; Estrela, T.; Lora, J. Desalination in Spain. Past, Present and Future. La Houille Blanche 2019, 105, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoudi, S.; Jamoussi, B. Desalination Technologies and Their Environmental Impacts: A Review. Sustain. Chem. One World 2024, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWA. Desalination–Past, Present and Future. Available online: https://iwa-network.org/desalination-past-present-future/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Desalination in the Context of Global Water Security. Available online: https://onewater.blue/article/desalination-in-the-context-of-global-water-security-10629f3f (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- European Commission and the European Environment Agency, Climate-ADAPT, Desalination. 2023. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/adaptation-options/desalinisation (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Liyanaarachchi, S.; Shu, L.; Muthukumaran, S.; Jegatheesan, V.; Baskaran, K. Problems in Seawater Industrial Desalination. Processes and Potential Sustainable Solutions: A Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Romero, L.T. Review on Solar Photovoltaic-Powered Pumping Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Kirpichnikova, I. Model of Solar Photovoltaic Water Pumping System for Domestic Application. In Proceedings of the 2021 28th International Workshop on Electric Drives: Improving Reliability of Electric Drives (IWED), Moscow, Russia, 27–29 January 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoudi, M.; Hemida, H.; Sharifi, S. Offshore Energy Island for Sustainable Water Desalination—Case Study of KSA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.P.; Fajardo, A.; Lara-Borrero, J. Decentralized Renewable-Energy Desalination: Emerging Trends and Global Research Frontiers—A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review. Water 2025, 17, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, W.; Machorro-Ortiz, A.; Jerome, B.; Naldoni, A.; Halas, N.J.; Dongare, P.D.; Alabastri, A. Decentralized Solar-Driven Photothermal Desalination: An Interdisciplinary Challenge to Transition Lab-Scale Research to Off-Grid Applications. ACS Photon. 2022, 9, 3764–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ang, L.; Ng, K.C. Energy-water-environment nexus underpinning future desalination sustainability. Desalination 2017, 413, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengel Gálvez, R.M.; Caparrós Mancera, J.J.; López González, E.; Tejada Guzmán, D.; Sancho Peñate, J.M. Application of Electric Energy Storage Technologies for Small and Medium Prosumers in Smart Grids. Processes 2025, 13, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.; Ramos, F.; Pinheiro, A.; Junior, W.d.A.S.; Arcanjo, A.M.C.; Filho, R.F.D.; Mohamed, M.A.; Marinho, M.H.N. Case Study of Backup Application with Energy Storage in Microgrids. Energies 2022, 15, 9514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cai, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Yan, N.; Ma, S. Research on Optimal Allocation Method of Energy Storage Considering Supply and Demand Flexibility and New Energy Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Wuhan, China, 30 October–1 November 2020; pp. 4368–4373. [Google Scholar]

- Shively, D.; Gardner, J.; Haynes, T.; Ferguson, J. Energy Storage Methods for Renewable Energy Integration and Grid Support. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Energy 2030 Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–18 November 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1334680/europe-battery-storage-capacity/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Rey, S.O.; Romero, J.A.; Romero, L.T.; Martínez, À.F.; Roger, X.S.; Qamar, M.A.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Gevorkov, L. Powering the Future: A Comprehensive Review of Battery Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.S.; Coelho, P.J.; Ferreira, A.F.; Surra, E. A Systematic Analysis of Life Cycle Assessments in Hydrogen Energy Systems. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ji, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Ni, H.; Zhu, Y. Review and Outlook of Fuel Cell Power Systems for Commercial Vehicles, Buses, and Heavy Trucks. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, M.; Tolj, I.; Barbir, F. Review of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell-Powered Systems for Stationary Applications Using Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2024, 17, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, A.; Arias, P.; Gevorkov, L.; Trilla, L.; Obrador Rey, S.; Roger, X.S.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Filbà Martínez, À. Optimizing Performance of Hybrid Electrochemical Energy Storage Systems through Effective Control: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilfoos, T. The evolution of the value of water power during the Industrial Revolution. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2025, 95, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, A.; Lokiec, F. Advanced MED process for most economical sea water desalination. Desalination 2005, 182, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Zhang, M.; Yao, A.; Zhang, H.; Jia, L.; Sun, W.; Xue, H. Design and performance analysis of a dual-nozzle ejector with an auxiliary nozzle for wide operating conditions in multi-effect distillation systems. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 66, 104077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergani, Z.; Triki, Z.; Menasri, R.; Tahraoui, H.; Kebir, M.; Amrane, A.; Moula, N.; Zhang, J.; Mouni, L. Analysis of Desalination Performance with a Thermal Vapor Compression System. Water 2023, 15, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feria-Díaz, J.J.; López-Méndez, M.C.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.P.; Sandoval-Herazo, L.C.; Correa-Mahecha, F. Commercial Thermal Technologies for Desalination of Water from Renewable Energies: A State of the Art Review. Processes 2021, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, D.; Franzitta, V.; Guercio, A. A Review of the Water Desalination Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Talamantes, F.J.; Velázquez-Limón, N.; Aguilar-Jiménez, J.A.; Casares-De la Torre, C.A.; López-Zavala, R.; Ríos-Arriola, J.; Islas-Pereda, S. A Novel High Vacuum MSF/MED Hybrid Desalination System for Simultaneous Production of Water, Cooling and Electrical Power, Using Two Barometric Ejector Condensers. Processes 2024, 12, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Toala, A.N.; Valverde-Armas, P.E.; Mendez-Ruiz, J.I.; Franco-González, K.; Verdezoto-Intriago, S.; Vitvar, T.; Gutiérrez, L. Brackish Water Desalination Using Electrodialysis: Influence of Operating Parameters on Energy Consumption and Scalability. Membranes 2025, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, F.; Arbós, R. Desalination of brackish river water using electrodialysis reversal (EDR): Control of the THMs formation in the Barcelona (NE Spain) area. Desalination 2010, 253, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.; Orfi, J.; Mokraoui, S. Hybrid Mechanical Vapor Compression and Membrane Distillation System: Concept and Analysis. Membranes 2025, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xing, Z.; Wang, X.; He, Z. Analysis of a single-effect mechanical vapor compression desalination system using water injected twin screw compressors. Desalination 2014, 333, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criscuoli, A. Water–Energy Nexus: Membrane Engineering Towards a Sustainable Development. Membranes 2025, 15, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, M.; Deng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Meng, H. Theoretical design of high-efficiency graphene oxide (GO) lamellar membranes for desalination through interface regulation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 134137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Fang, Z.; Hu, X. Modified graphene oxide (GO) embedded in nanofiltration membranes with high flux and anti-fouling for enhanced surface water purification. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Alkhadra, M.A.; Bazant, M.Z. Theory of shock electrodialysis II: Mechanisms of selective ion removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 589, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhadra, M.; Gao, T.; Conforti, K.; Bazant, M.Z. Small-scale desalination of seawater by shock electrodialysis. Desalination 2020, 476, 114219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. Design of Forward Osmosis Desalination Configurations: Exergy and Energy Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, A.S.T.; Imandoust, M.; Montazeri, A.; Zahedi, R. Technical, economic and environmental evaluation and optimization of the hybrid solar-wind power generation with desalination. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Smidl, V. Simulation Model for Efficiency Estimation of Photovoltaic Water Pumping System. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 18–20 March 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dhoska, K.; Spaho, E.; Sinani, U. Fabrication of Black Silicon Antireflection Coatings to Enhance Light Harvesting in Photovoltaics. Eng 2024, 5, 3358–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Rassõlkin, A.; Vaimann, T. Comparative Simulation Study of Pump System Efficiency Driven by Induction and Synchronous Reluctance Motors. Energies 2022, 15, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Šmídl, V.; Sirový, M. Model of Hybrid Speed and Throttle Control for Centrifugal Pump System Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 563–568. [Google Scholar]

- Bakman, I.; Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V. Predictive control of a variable-speed multi-pump motor drive. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Istanbul, Turkey, 1–4 June 2014; pp. 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V.; Lehtla, T.; Raud, Z. PLC-based hardware-in-the-loop simulator of a centrifugal pump. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 5th International Conference on Power Engineering, Energy and Electrical Drives (POWERENG), Riga, Latvia, 11–13 May 2015; pp. 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Muñoz, A.C.; Debbat, M.B.; Pepiciello, A.; Domínguez-García, J.L. Triple Active Bridge Modeling and Decoupling Control. Electronics 2025, 14, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Romero, L.T.; Martínez, À.F. Modern MultiPort Converter Technologies: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Martínez, À.F. Modern Trends in MultiPort Converters: Isolated, Non-Isolated, and Partially Isolated. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 63th International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University (RTUCON), Riga, Latvia, 10–12 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yahya, W.; Saied, K.M.; Nassar, A.; Qader, M.R.; Al-Nehari, M.; Zarabia, J.; Zhou, J. Optimization of a hybrid renewable energy system consisting of PV/wind turbine/battery/fuel cell integration and component design. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 94, 1406–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua, S.R.; Yeon, A.N.; Park, S.; Kwon, K. Solar–Hydrogen Storage System: Architecture and Integration Design of University Energy Management Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilion, F. Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Desalination. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba-Alawi, A.H.; Nguyen, H.-T.; Yoo, C. Sustainable design of a solar/wind-powered reverse osmosis system with cooperative demand-side water management: A coordinated sizing approach with a fuzzy decision-making model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 295, 117624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba-Alawi, A.H.; Nguyen, H.-T.; Aamer, H.; Yoo, C. Techno-economic risk-constrained optimization for sustainable green hydrogen energy storage in solar/wind-powered reverse osmosis systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhang, B.; Ghaebi, H.; Javani, N. Techno-Economic Modeling of a Novel Poly-Generation System Based on Biogas for Power, Hydrogen, Freshwater, and Ammonia Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Kuo, P.-C.; Aziz, M. Novel Renewable Seawater Desalination System Using Hydrogen as Energy Carrier for Self-Sustaining Community. Desalination 2024, 579, 117475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Romero, L.T.; Martínez, À.F. Advances on Application of Modern Energy Storage Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), Tenerife, Spain, 19–21 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dascalu, A.; Cruden, A.J.; Sharkh, S.M. Experimental Investigations into a Hybrid Energy Storage System Using Directly Connected Lead-Acid and Li-Ion Batteries. Energies 2024, 17, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, R.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, Y. On-line measurement of internal resistance of lithium ion battery for EV and its application research. Int. J. u-e-Serv. Sci. Technol. 2014, 7, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Trilla, L. The Synergy of Renewable Energy and Desalination: An Overview of Current Practices and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, A.D.; Hallett, J.P.; Riley, D.J.; Shah, N.; Payne, D.J. Lead Acid Battery Recycling for the Twenty-First Century. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, A.S.; Fajarna, R.; Asrol, M.; Mozar, F.S.; Harito, C.; Pardamean, B.; Speaks, D.; Djuana, E. Estimation of Lead Acid Battery Degradation—A Model for the Optimization of Battery Energy Storage System Using Machine Learning. Electrochem 2025, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Ghenai, C. Performance evaluation and optimal design of stand-alone solar PV-battery system for irrigation in isolated regions: A case study in Al Minya (Egypt). Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 36, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B. Self-discharge in rechargeable electrochemical energy storage devices. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 67, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoy, K.R.; Lukong, V.T.; Yoro, K.O.; Makambo, J.B.; Chukwuati, N.C.; Ibegbulam, C.; Eterigho-Ikelegbe, O.; Ukoba, K.; Jen, T.-C. Lithium-ion batteries and the future of sustainable energy: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 223, 115971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhuang, W.; Yin, G. Rule-filter-integrated Control of LFP/LTO Hybrid Energy Storage System for Vehicular Application. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 1542–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neunzling, J.; Winter, H.; Henriques, D.; Fleckenstein, M.; Markus, T. Online State-of-Health Estimation for NMC Lithium-Ion Batteries Using an Observer Structure. Batteries 2023, 9, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador Rey, S.; Canals Casals, L.; Gevorkov, L.; Cremades Oliver, L.; Trilla, L. Critical Review on the Sustainability of Electric Vehicles: Addressing Challenges without Interfering in Market Trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, A.-I.; Świerczyński, M.; Stroe, D.-I.; Teodorescu, R.; Andreasen, S.J. Lithium ion battery chemistries from renewable energy storage to automotive and back-up power applications—An overview. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (OPTIM), Bran, Romania, 22–24 May 2014; pp. 713–720. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, D.; Chang, M.-J.; Hung, I.-M. The Effect of Different Amounts of Conductive Carbon Material on the Electrochemical Performance of the LiFePO4 Cathode in Li-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.; Zhan, C. A critical review on nickel-based cathodes in rechargeable batteries. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, U.; Gandhi Ayyavu, P.; Panchal, H.; Shanmugam, D.; Balasubramani, S.; Al-rubaie, A.J.; Al-khaykan, A.; Oza, A.D.; Hem-brom, S.; Patel, T.; et al. Efficient Battery Models for Performance Studies-Lithium Ion and Nickel Metal Hydride Battery. Batteries 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsais, P.-J.; Chan, L.I. 11—Nickel-based batteries: Materials and chemistry. In Electricity Transmission, Distribution and Storage Systems; Melhem, Z., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Southton, UK, 2013; pp. 309–397. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinsky, M.A.; Koch, J.M.; Young, K.-H. Performance Comparison of Rechargeable Batteries for Stationary Applications (Ni/MH vs. Ni–Cd and VRLA). Batteries 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, H.; Sayed, E.T.; Al-Dhaifallah, M.; Obaid, M.; El-Sayed, A.H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A.G. Fuel cell as an effective energy storage in reverse osmosis desalination plant powered by photovoltaic system. Energy 2019, 175, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo Gonzalez, H.; Bianchi, F.D.; Torrell, M.; Bernadet, L.; Eichman, J.; Tarancón, A.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Predictive control for mode-switching of reversible solid oxide cells in microgrids based on hydrogen and electricity markets. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 102, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, L.; Bordons, C.; Rosa, F. Integration of fuel cell technologies in renewable-energy-based microgrids optimizing operational costs and durability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 63, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, Ł.; Sztekler, K.; Bujok, T.; Boruta, P.; Radomska, E. Seawater Treatment Technologies for Hydrogen Production by Electrolysis—A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressel, M.; Hilairet, M.; Hissel, D.; Bouamama, B.O. Model-based aging tolerant control with power loss prediction of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 11242–11254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, A.B.; del Pozo Gonzalez, H.; Trilla, L. Hydrogen-Based Grids: Technologies and P2H2P Integration. In Energy Systems Integration for Multi-Energy Systems: From Operation to Planning in the Green Energy Context; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Ding, J.; Lin, B. Current Challenges on the Alkaline Stability of Anion Exchange Membranes for Fuel Cells. ChemElectroChem 2023, 10, e202300445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriday, T.B.; Middleton, P.H. Alkaline fuel cell technology—A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 18489–18510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawahdeh, A.I.; Moh’d, A.A.N.; Al-Sarhan, T.N. Performance evaluation for a high temperature alkaline fuel cell integrated with thermal vapor compression desalination. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.D.; Kunusch, C.; Ocampo-Martinez, C.; Sánchez-Peña, R.S. A gain-scheduled LPV control for oxygen stoichiometry regulation in PEM fuel cell systems. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2013, 22, 1837–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgaldi, S.; Alaefour, I.; Li, X. Impact of Manufacturing Processes on Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Performance. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahl, S.; Costa-Castelló, R. Model-based analysis for the thermal management of open-cathode proton exchange membrane fuel cell systems concerning efficiency and stability. J. Process Control 2016, 47, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammes, N.; Bove, R.; Stahl, K. Phosphoric acid fuel cells: Fundamentals and applications. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.; Mohamad, A.B.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Loh, K.S. A review on synthesis and characterization of solid acid materials for fuel cell applications. J. Power Sources 2016, 322, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, A.L. Molten carbonate fuel cells. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybiński, O.; Milewski, J.; Szabłowski, Ł.; Szczęśniak, A.; Martinchyk, A. Methanol, ethanol, propanol, butanol and glycerol as hydrogen carriers for direct utilization in molten carbonate fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 37637–37653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo Gonzalez, H.; Torrell, M.; Bernadet, L.; Bianchi, F.D.; Trilla, L.; Tarancón, A.; Domínguez-García, J.L. Mathematical modeling and thermal control of a 1.5 kW reversible solid oxide stack for 24/7 hydrogen plants. Mathematics 2023, 11, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernadet, L.; Buzi, F.; Baiutti, F.; Segura-Ruiz, J.; Dolado, J.; Montinaro, D.; Tarancón, A. Thickness effect of thin-film barrier layers for enhanced long-term operation of solid oxide fuel cells. APL Energy 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo Gonzalez, H.; Bernadet, L.; Torrell, M.; Bianchi, F.D.; Tarancón, A.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O.; Dominguez-Garcia, J.L. Power transition cycles of reversible solid oxide cells and its impacts on microgrids. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Ali, M.A.; Alizadeh, A.; Zhou, J.; Dhahad, H.A.; Singh, P.K.; Almojil, S.F.; Almohana, A.I.; Alali, A.F.; Shamseldin, M. Recurrent neural networks optimization of biomass-based solid oxide fuel cells combined with the hydrogen fuel electrolyzer and reverse osmosis water desalination. Fuel 2023, 346, 128268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandarianto, F.A.; Ichsani, D.; Taufany, F. Thermal and Fluid Flow Performance Optimization of a Multi-Fin Multi-Channel Cooling System for PEMFC Using CFD and Experimental Validation. Energies 2025, 18, 5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, S. Cryogenic Cooling and Fuel Cell Hybrid System for HTS Maglev Trains Employing Liquid Hydrogen. Cryogenics 2025, 149, 104109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, S.K.; Saxena, D. Energy management system for smart grid: An overview and key issues. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4067–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moigne, P.; Rizoug, N.; Mesbahi, T.; Bartholomes, P. A New Energy Management Strategy of a Battery/Supercapacitor Hybrid Energy Storage System for Electric Vehicular Applications. In Proceedings of the 7th IET International Conference on Power Electronics, Machines and Drives (PEMD), Manchester, UK, 8–10 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.; Xiao, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Tao, X.; Qian, Q.; Jiang, M.; Yu, W. Power Allocation and Capacity Optimization Configuration of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems in Microgrids Using RW-GWO-VMD. Energies 2025, 18, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Bathaee, S.M.T. Multi-objective genetic optimization of the fuel cell hybrid vehicle supervisory system: Fuzzy logic and operating mode control strategies. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 12512–12521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caux, S.; Hankache, W.; Fadel, M.; Hissel, D. On-line fuzzy energy management for hybrid fuel cell systems. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 2134–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemi, H.; Ghouili, J.; Cheriti, A. A real time fuzzy logic power management strategy for a fuel cell vehicle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 80, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azib, T.; Hemsas, K.E.; Larouci, C. Energy Management and Control Strategy of Hybrid Energy Storage System for Fuel Cell Power Sources. Int. Rev. Model. Simul. (IREMOS) 2014, 7, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzougui, H.; Kadri, A.; Amari, M.; Bacha, F. Energy Management of Fuel Cell Vehicle with Hybrid Storage System: A Frequency Based Distribution. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Paris, France, 23–26 April 2019; pp. 1853–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebarki, N.; Rekioua, T.; Mokrani, Z.; Rekioua, D.; Bacha, S. PEM fuel cell/battery storage system supplying electric vehicle. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 20993–21005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassam, A.M.; Phillips, A.B.; Turnock, S.R.; Wilson, P.A. An improved energy management strategy for a hybrid fuel cell/battery passenger vessel. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 22453–22464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, A.A.; Rezk, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Enhancing the operation of fuel cell-photovoltaic-battery-supercapacitor renewable system through a hybrid energy management strategy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 6061–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, C.; Bocklisch, T. Simulation-based investigation of energy management concepts for fuel cell-battery-hybrid energy storage systems in mobile applications. Energy Procedia 2018, 155, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounica, V.; Obulesu, Y.P. Hybrid Power Management Strategy with Fuel Cell, Battery, and Supercapacitor for Fuel Economy in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Application. Energies 2022, 15, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, D.; Chedid, R.; Panik, F.; Karaki, S.; Jabr, R. Dynamic programming technique for optimizing fuel cell hybrid vehicles. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 7777–7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.-H.; German, R.; Trovão, J.P.F.; Bouscayrol, A. Real-Time Energy Management of Battery/Supercapacitor Electric Vehicles Based on an Adaptation of Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.D.P.; Bianchi, F.D.; Dominguez-Garcia, J.L.; Gomis-Bellmunt, O. Co-located wind-wave farms: Optimal control and grid integration. Energy 2023, 272, 127176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Cronje, W.; van Wyk, M.A. Design Optimization of a Hybrid Energy System through Fast Convex Programming. In Proceedings of the 2014 5th International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Modelling and Simulation (ISMS), Langkawi, Malaysia, 27–29 January 2014; pp. 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Ghaithan, A.M.; Al-Hanbali, A.; Attia, A.M. A multi-objective optimization model based on mixed integer linear programming for sizing a hybrid PV-hydrogen storage system. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 9748–9761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Shi, T. Wind-Photovoltaic-Storage Cooperative Bidding Strategy Based on Differential Evolutionary Game. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Harbin, China, 10–12 May 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chauhan, P.; Singh, N. Capacity optimization of grid connected solar/fuel cell energy system using hybrid ABC-PSO algorithm. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 10070–10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Bu, J.; Sun, B. Research on Smooth Wind Power Control Strategy for Hybrid Energy Storage Based on MPC. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th Conference on Fully Actuated System Theory and Applications (FASTA), Nanjing, China, 4–6 July 2025; pp. 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassourou, M.; Blesa, J.; Puig, V. Robust economic model predictive control based on a zonotope and local feedback controller for energy dispatch in smart-grids considering demand uncertainty. Energies 2020, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zou, C.; Tang, X.; Liu, T.; Hu, L. Cost-optimal energy management of hybrid electric vehicles using fuel cell/battery health-aware predictive control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 35, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Partridge, J.; Bucknall, R. Cost-effective reinforcement learning energy management for plug-in hybrid fuel cell and battery ships. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Zheng, J.; Ma, J.; Dong, Z.; Chen, Z.; Qin, Y. Application of machine learning in fuel cell research. Energies 2023, 16, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo Gonzalez, H.; Bianchi, F.D.; Cutululis, N.A.; Dominguez-Garcia, J.L. Providing frequency support to offshore energy hubs using hydrogen and wind reserves. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 343, 120139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Luo, L.; Tian, Z.; Shen, J.; He, D.; Dong, Z. ADMM-based health-conscious energy management strategy with fuel cell and battery degradation synergy real-time control for fuel cell vehicle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 333, 119812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Huangfu, Y.; Xu, L.; Pang, S. Online energy management strategy considering fuel cell fault for multi-stack fuel cell hybrid vehicle based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2022, 328, 120234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, H.D.P.; Domínguez-García, J.L. Non-centralized hierarchical model predictive control strategy of floating offshore wind farms for fatigue load reduction. Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Min, H.; Zhao, H.; Sun, W.; Zeng, B.; Ma, Q. A Data-Driven Prediction Method for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Degradation. Energies 2024, 17, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Yoo, S. Diagnostic method for PEM fuel cell states using probability distribution-based loss component analysis for voltage loss decomposition. Appl. Energy 2023, 330, 120340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Vilathgamuwa, M.; Farrell, T.; Choi, S.S.; Li, Y.; Teague, J. A computationally-efficient electrochemical-thermal model for small-format cylindrical lithium ion batteries. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 4th Southern Power Electronics Conference (SPEC), Singapore, 10–13 December 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, K. Lithium-Ion Battery Condition Monitoring: A Frontier in Acoustic Sensing Technology. Energies 2025, 18, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Liang, W.; Chen, M.; Xu, R. High-Temperature Stability of LiFePO4/Carbon Lithium-Ion Batteries: Challenges and Strategies. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Vodovozov, V. Study of the centrifugal pump efficiency at throttling and speed control. In Proceedings of the 2016 15th Biennial Baltic Electronics Conference (BEC), Tallinn, Estonia, 3–5 October 2016; pp. 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovozov, V.; Lehtla, T.; Bakman, I.; Raud, Z.; Gevorkov, L. Energy-efficient predictive control of centrifugal multi-pump stations. In Proceedings of the 2016 Electric Power Quality and Supply Reliability (PQ), Tallinn, Estonia, 29–31 August 2016; pp. 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology | Energy Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Cost/m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MED | Therma, Electrical | High efficiency, operates at lower temperatures, good for cogeneration | High capital cost, complex construction, corrosion and scaling concerns | $0.8–$2.5 |

| MSF | Thermal, Electrical | Reliable, robust, handles poor feedwater quality, large capacity | Very high energy consumption, high operating temperature promotes scaling | $1.0–$3.0 |

| ED | Electrochemical | Highly efficient for brackish water, low pressure operation, high water recovery | Not suitable for seawater, membrane cost and replacement, pre-treatment required | $0.4–$1.0 |

| MVC | Thermal | All thermal energy from electrical input, compact, modular, good for remote areas | Limited to small-to-medium scale, high electrical consumption, high maintenance costs | $1.5–$3.0 |

| RO | Electrical | Lowest energy consumption (for membranes), modular, widespread, lower capital cost | Extensive pre-treatment required, membrane fouling and replacement, brine management | $0.5–$1.5 |

| GO | Electrical | Potential for very high permeability and selectivity, potential for lower energy, antifouling properties | Early R&D stage, challenges with scalability, long-term stability in water, and membrane swelling | - |

| SED | Electrical | Membrane-less (avoids fouling/scaling), potential for high recovery rates and treatment of challenging feeds | Early R&D conceptual stage, challenges in scaling up from microfluidics, system complexity | - |

| Strategy | Optimality | Computational Cost | RT Performance | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuzzy Logic | Sub-optimal | Very-Low | Excellent | Low |

| Filter-Based | Sub-optimal | Low | Excellent | Low |

| ECMS | Near-Optimal | Low to Medium | Good | Medium |

| MPC | Near-Optimal | Medium to High | Depends on model | High |

| PSO, GA, DE | Good | Extremely High | Poor | High |

| RL | Data-driven optimal | Very High (training) Low (execution) | Good after training | Very High |

| Robust Optimization | Conservative Optimal | High | Fair | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gevorkov, L.; Gonzalez, H.d.P.; Arias, P.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Trilla, L. Enabling Reliable Freshwater Supply: A Review of Fuel Cell and Battery Hybridization for Solar- and Wind-Powered Desalination. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212145

Gevorkov L, Gonzalez HdP, Arias P, Domínguez-García JL, Trilla L. Enabling Reliable Freshwater Supply: A Review of Fuel Cell and Battery Hybridization for Solar- and Wind-Powered Desalination. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212145

Chicago/Turabian StyleGevorkov, Levon, Hector del Pozo Gonzalez, Paula Arias, José Luis Domínguez-García, and Lluis Trilla. 2025. "Enabling Reliable Freshwater Supply: A Review of Fuel Cell and Battery Hybridization for Solar- and Wind-Powered Desalination" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212145

APA StyleGevorkov, L., Gonzalez, H. d. P., Arias, P., Domínguez-García, J. L., & Trilla, L. (2025). Enabling Reliable Freshwater Supply: A Review of Fuel Cell and Battery Hybridization for Solar- and Wind-Powered Desalination. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12145. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212145