Multi-Property Infrared Sensor Array for Intelligent Human Tracking in Privacy-Preserving Ambient Assisted Living

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Achieving privacy protection at the sensor level.

- A multi-property sensors fusion architecture that integrates IR and ToF sensors for privacy-preserving 3D human tracking.

- A CNN architecture featuring a cross-sensor attention mechanism, designed for real-time inference on low-cost, non-GPU devices.

- Obtaining the XYZ three-dimensional coordinates of the human body in an indoor environment.

2. Related Work

2.1. Privacy in Ambient Assisted Living (AAL)

- Visual Privacy, which is the protection of a person’s physical appearance, including their “face, body, and any identifiable features”.

- Behavioral Privacy, which “pertains to the protection of an individual’s actions, routines, and habits”.

2.2. Privacy Protection Methods

- Visual Transformation: Camera-based systems have dominated human tracking and activity recognition research due to their rich spatial–temporal data. Early works [15] used RGB cameras with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to achieve sub-centimeter localization accuracy in controlled environments. Recent advancements in pose estimation [16] (e.g., OpenPose [17]) further improved robustness under occlusion. However, these systems inherently expose sensitive visual information, prompting studies to quantify privacy risks. Some methods to ensure privacy include altering the video feed by “blurring the face and body” or replacing the person’s image entirely with a 2D or 3D avatar. The avatar-based approach is often preferred as it offers a “higher level of privacy protection by completely replacing the original image while retaining the functionality of the surveillance system”.

- Data Abstraction: This method involves using vision-based systems that process raw video to extract only skeletal data to generate the action and event data of those being monitored.

- Non-Visual Sensing: According to a classification scheme mentioned in [18], privacy design is divided into different levels. Moving upwards in scope, it can be specified as sensor level, model level, system level, user interface level, and privacy at the user level.The above methods belong to the model level, system level, and user interface level. The most basic of these is at the sensor level, which avoids cameras altogether by using environmental sensors and wearables or other devices to monitor activities and emergencies.

- Wearable device [19,20]: It is possible to detect human position and posture via smart watch, smart shirt etc. However, most wearable devices need to be charged frequently and require remembering to wear them, which is more troublesome. Nevertheless, these methods can usually achieve good results [21]. Electromyography (EGM) sensors are also a common method. The system mentioned in [22] can collect 16 channels of muscle activity data during lower limb movement, and the accuracy of lower limb movement recognition reaches 97.88%.

- RF/Wi-Fi Sensing: Methods like [23,24] analyzed wireless signal reflections for motion detection. While privacy-friendly, these struggle with localization (root mean square error is approximately 0.5–2.0 m in method [23], and the percent error is approximately 5–40%, with a maximum of about 60% in method [24]).

- Thermal Imaging: Systems like [12] use a pixel Omron D6T-44L-06 thermopile infrared sensor to monitor the m experiment space, whose localization accuracy is 9.6 cm root mean square error. And [25] used thermal arrays to detect human and tracking their position. This method makes it difficult to obtain depth (Z-axis) data. Therefore, this method requires the infrared sensor to be placed on the ceiling, and only X- and Y-axis data can be obtained. Accuracy (i.e., error < 0.3 m) = 86.79% (three people), 97.59% (single person).

- Other non-visual, non-invasive devices: These devices are typically placed in the environment and do not require cameras or wearable devices. For example, Shao et al. (2019) developed a system using high-precision vibration sensors embedded in floors or furniture to monitor the daily activities and physical condition of older adults through subtle vibrations [26]. Yamamoto et al. (2019) used air pressure sensors placed on beds to measure vital signs and provide elderly care [27]. While these methods have shown promising results in specific areas and do not infringe on user privacy, they often provide limited or no spatial information. The lack of location data makes it difficult to perform more complex analyses such as gait assessment, fall detection, or detailed activity recognition.

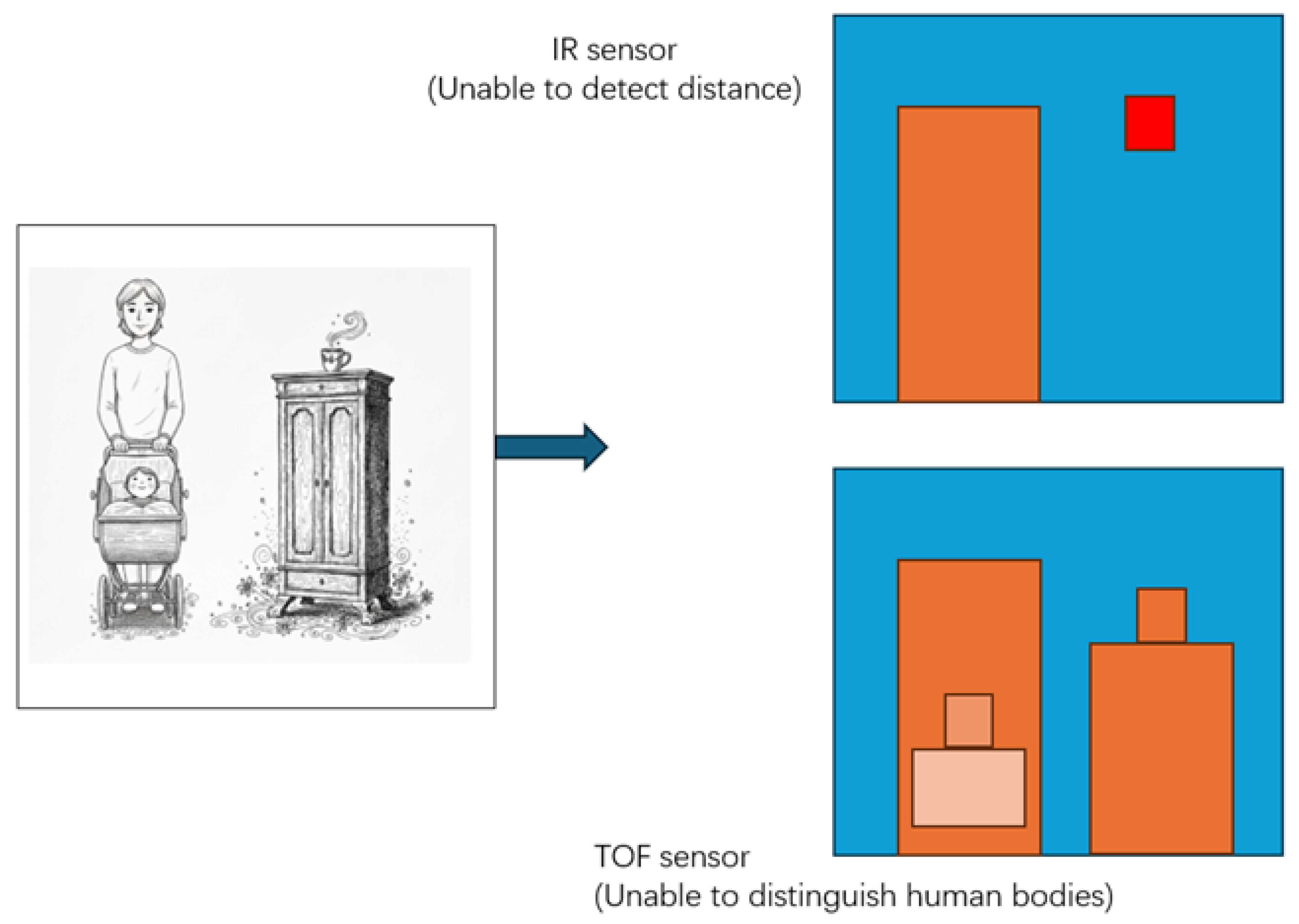

2.3. Sensor Selection

2.4. Previous Studies Using Low-Resolution IR Sensors

3. Method

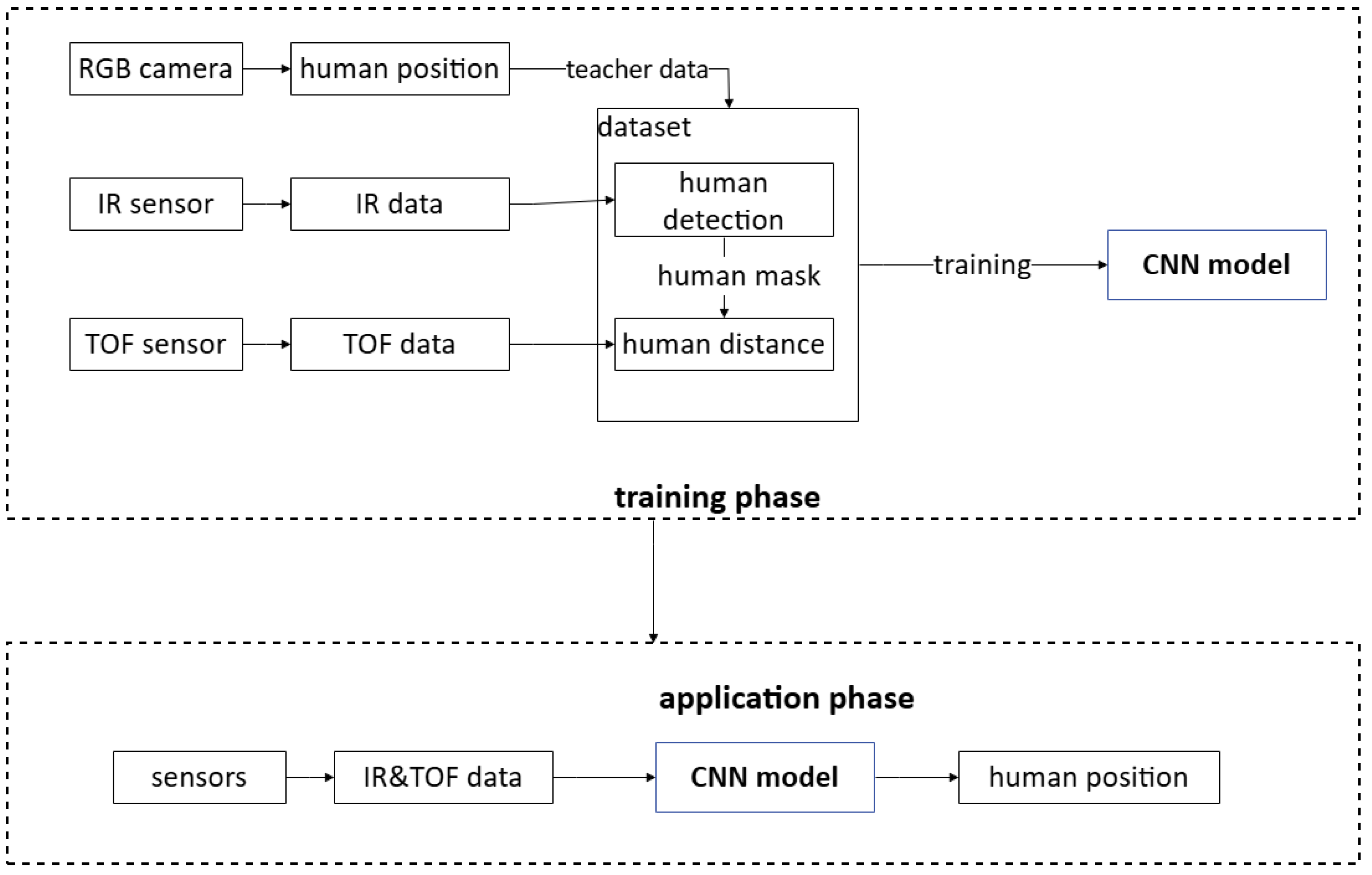

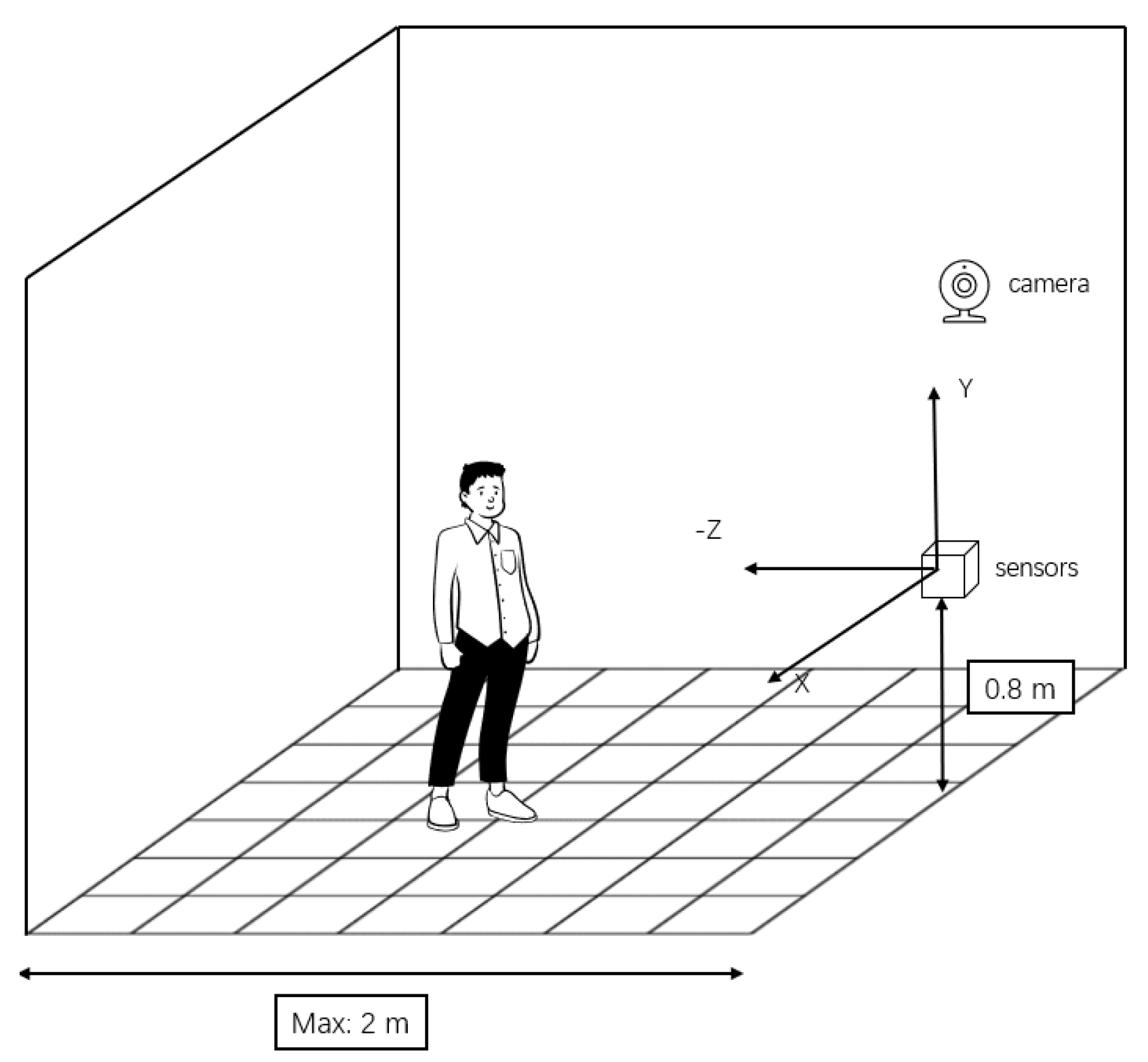

3.1. Proposed System Architecture

3.2. Sensor Configuration

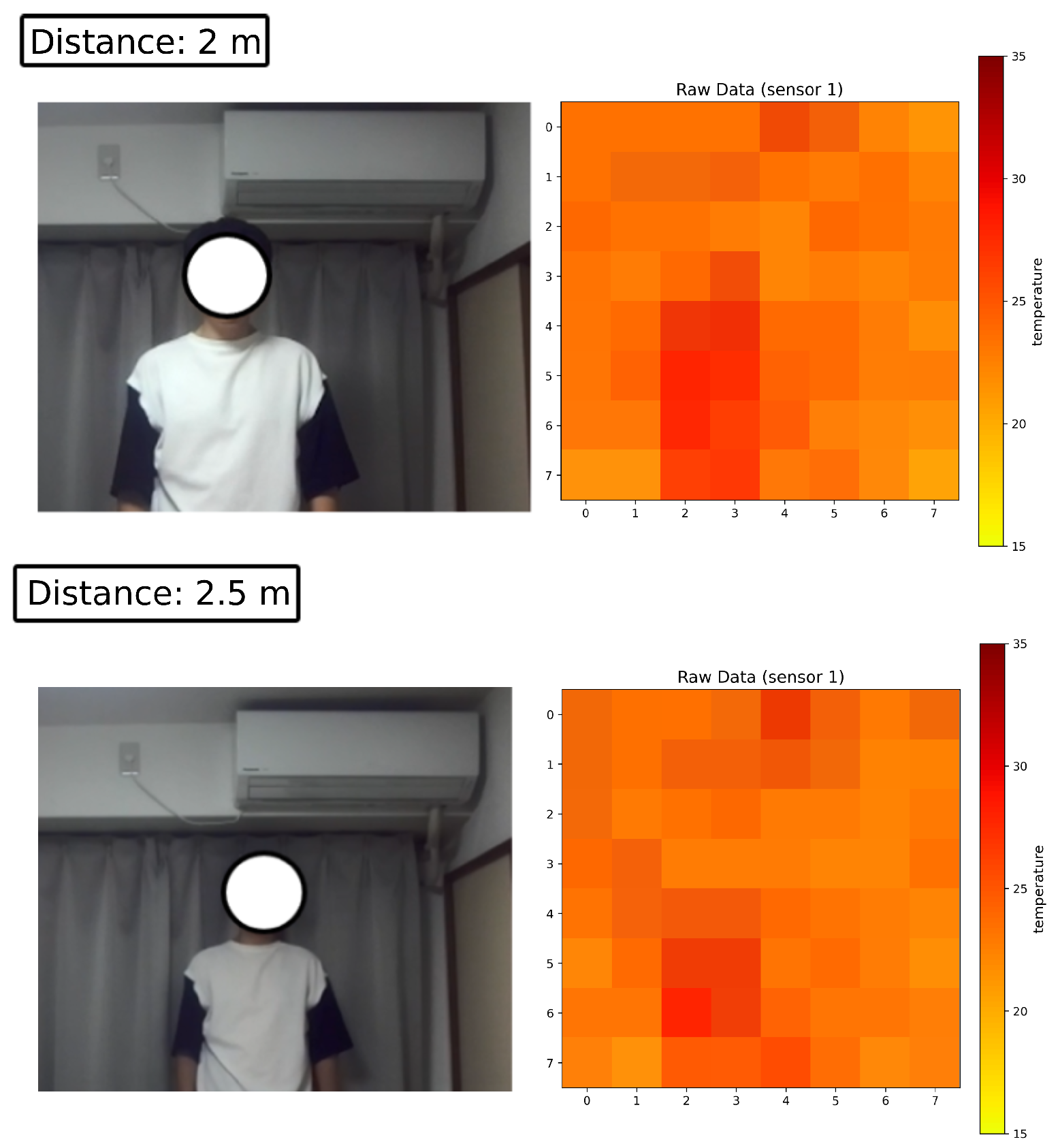

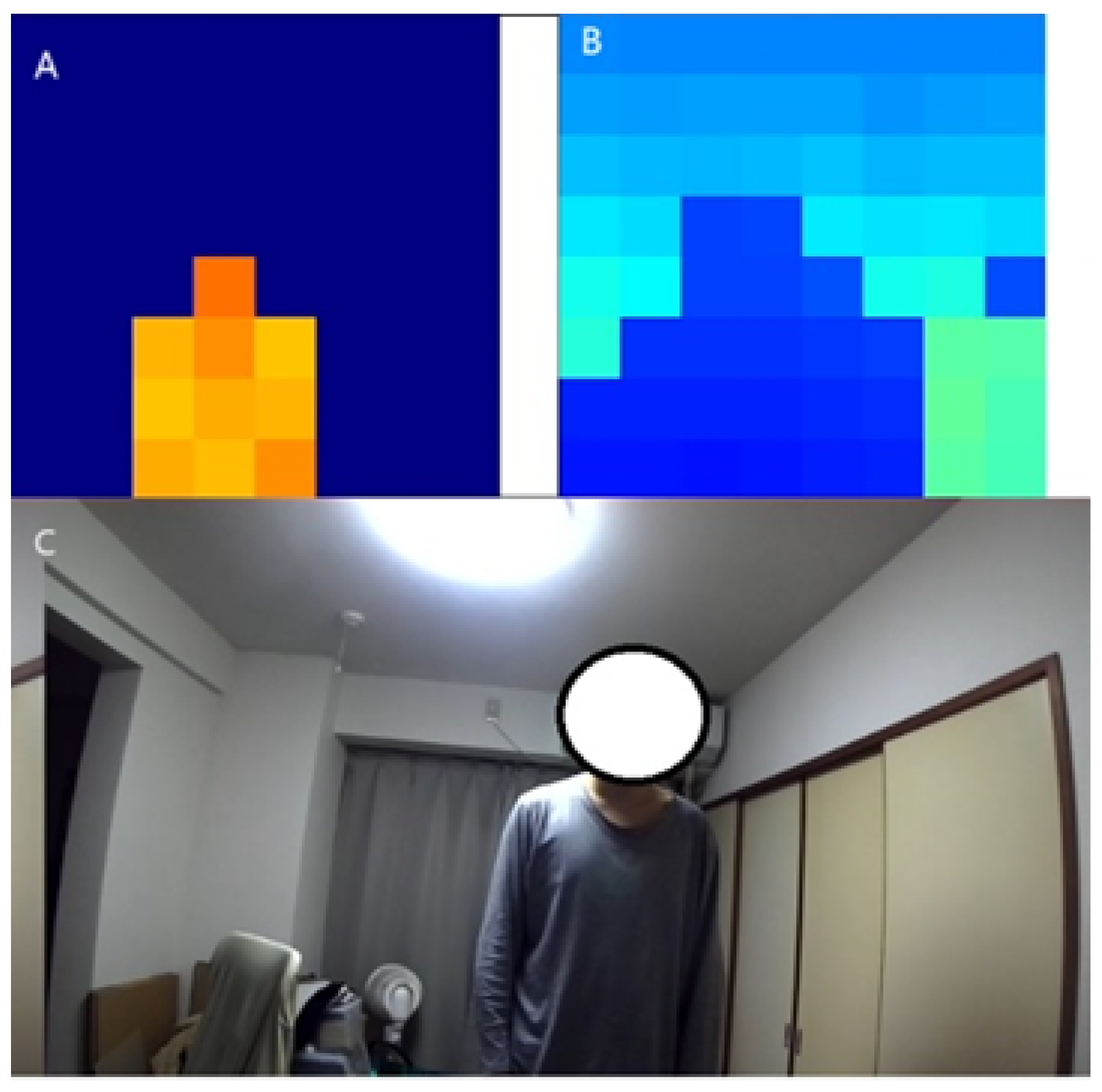

3.3. Data Preprocessing

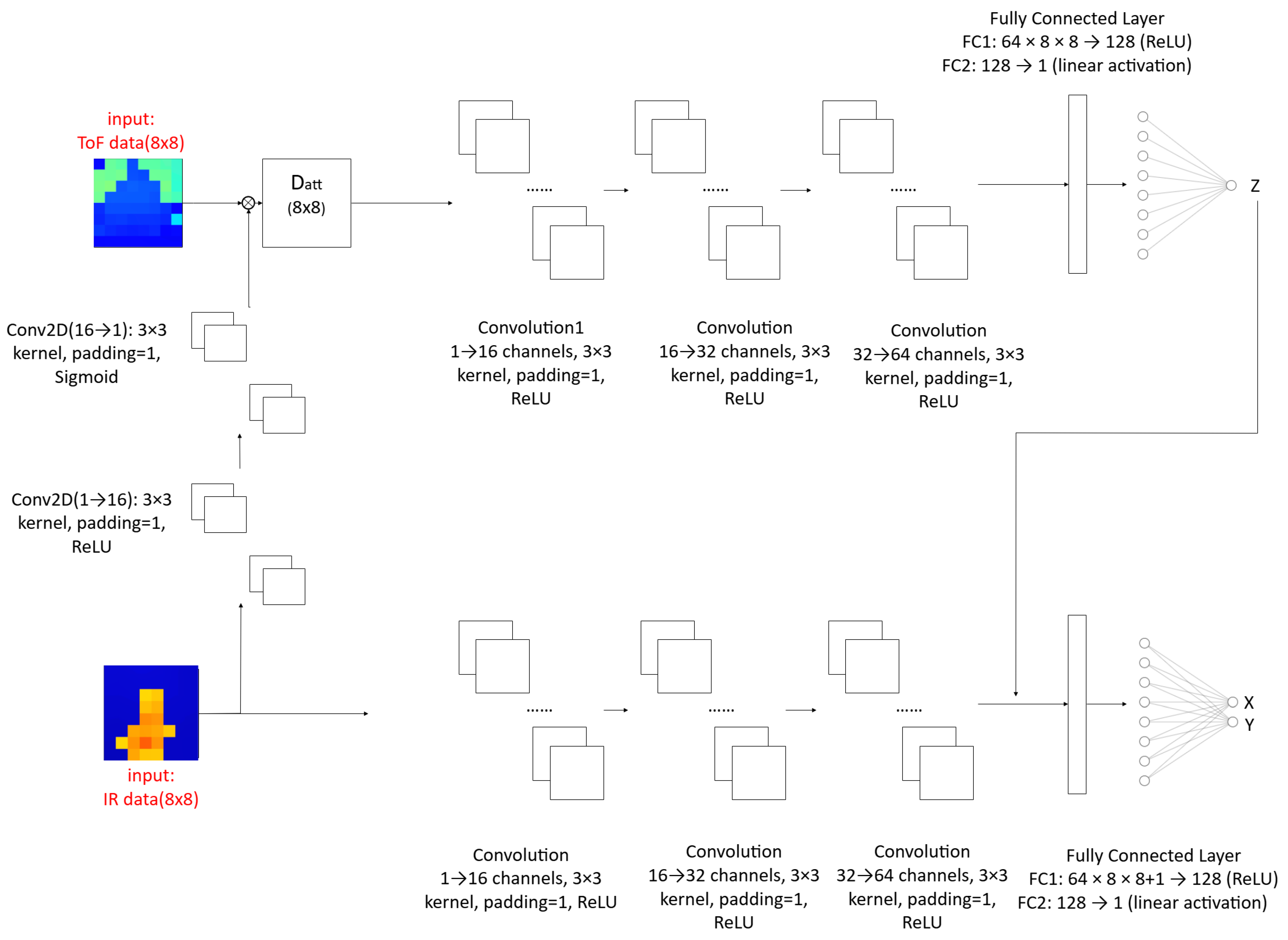

3.4. Proposed Network Architecture

- Cross-Sensor Attention ModuleDynamically enhances human-related depth features in ToF data using IR thermal patterns while suppressing background noise.

- IR Feature Extraction:Input: IR data (after initial filtering).Convolutional Processing:Conv2D (1→16): kernel, padding = 1, ReLU activation.Conv2D (16→1): kernel, padding = 1, Sigmoid activation.Output: An attention mask , where values near 1 indicate regions with human activity likelihood.

- ToF Feature Enhancement:Apply the attention mask M to raw ToF depth data D via element-wise multiplication, as shown in Equation (2).

where is the raw ToF matrix and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. This amplifies depth signals in human-occupied areas and suppresses static background interference (e.g., furniture). - Dual-Stream Processing

- ToF Stream (Z-axis Estimation):Objective: Estimate vertical positioning (height) from attention-enhanced ToF data.Convolutional Feature Extraction:Three sequential convolutional blocks used and the output: 64-channel feature map was obtained.Flatten into predicted vertical position z. Two fully connected (FC) layers:FC1: dimensions (ReLU).FC2: dimension (linear activation).Predicted vertical position z as the output was obtained.

- IR Stream (XY-axis Estimation):Estimate horizontal coordinates by fusing IR thermal data with predicted Z coordinate Z.Identical structure to ToF stream, three convolutional blocks ( channels). A 64-channel feature map was obtained.Concatenate with the predicted Z coordinate z,where is the final concatenated feature vector, is the flattened 4096-dimensional feature vector from the IR stream, and z is the predicted Z coordinate from the ToF stream.Two FC layers are applied:FC1: dimensions (ReLU).FC2: dimensions (linear activation).Predicted horizontal coordinates as the output is obtained.

- Loss Function:The network is trained using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss, a standard choice for regression tasks, as defined in the code by nn.MSELoss(); the equation is shown in Equation (4).where is the network’s predicted 3D coordinates, and is the ground truth coordinates. This loss function computes the average squared difference, applying equal importance to the errors in all three axes (x, y, and z), rather than prioritizing specific axes with different weights.

3.5. Key Mechanism Parameter Explanation

- kernel_size=3, padding=1: This configuration is applied to both convolutional layers to ensure the spatial dimensions of the feature maps are preserved (i.e., “same” padding). Maintaining the resolution is a critical design requirement, as the output attention mask must retain a direct spatial correspondence with the ToF sensor image. This alignment is necessary for the subsequent element-wise multiplication (gating) step.

- conv1(in=1, out=16): The initial layer functions as a feature extractor, expanding the single-channel IR input into a 16-channel feature space. The rationale for this expansion is to compensate for the information-sparse nature of the raw IR data. By increasing the feature dimensionality, the network is afforded the capacity to learn more complex and abstract representations, such as thermal gradients and edges, rather than being limited to raw temperature values.

- conv2(in=16, out=1): Conversely, the final convolutional layer performs dimensionality reduction, squeezing the 16-channel feature maps back into a single-channel output. This is conceptually necessary as the final output must serve as a unified spatial attention map, where each pixel location is assigned a single scalar importance value. This layer effectively integrates the multi-dimensional abstract features learned by conv1 into this final, cohesive weight map.

- Sigmoid() Activation: Sigmoid activation is applied to the final single-channel output. Its function is to normalize the logits from conv2 into a probabilistic range of [0, 1]. This normalization is essential for the map to function as a “soft gate” or mask. The resulting values act as coefficients for the subsequent element-wise multiplication: values approaching 1.0 signify high relevance (allowing the corresponding ToF data to pass through), while values approaching 0.0 signify low relevance (suppressing the ToF data).

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Environment and Dataset

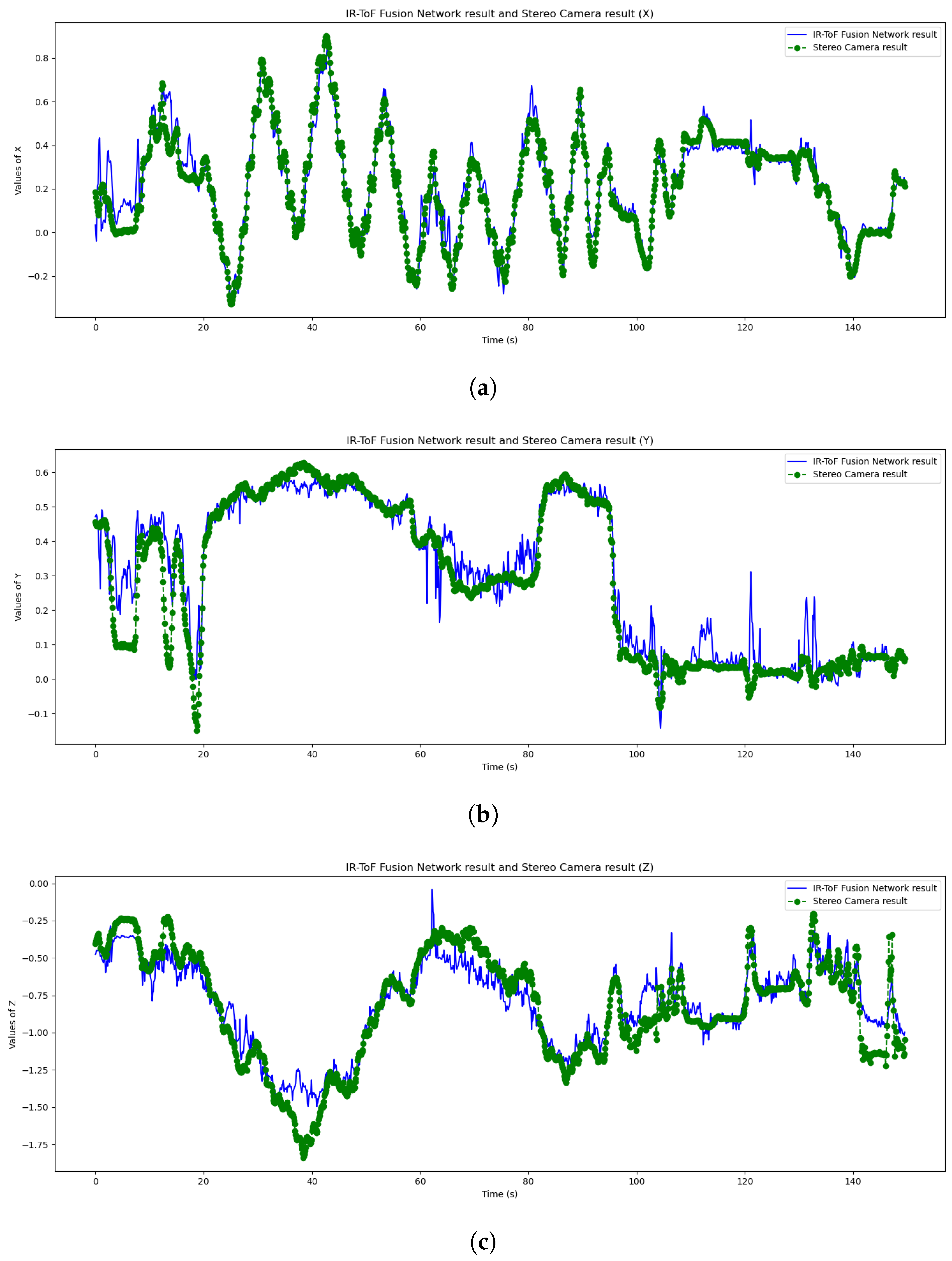

4.2. Results and Analysis

4.3. Testing of Various Walking Patterns

- Circle shape: Circle shape refers to the test subject’s movement in a circular trajectory in the test space, mainly testing the system’s tracking capability along the X–Z-axis (i.e., the person’s coordinates on the ground). The result is shown as Figure 11. And the error metrics are shown as Table 8.

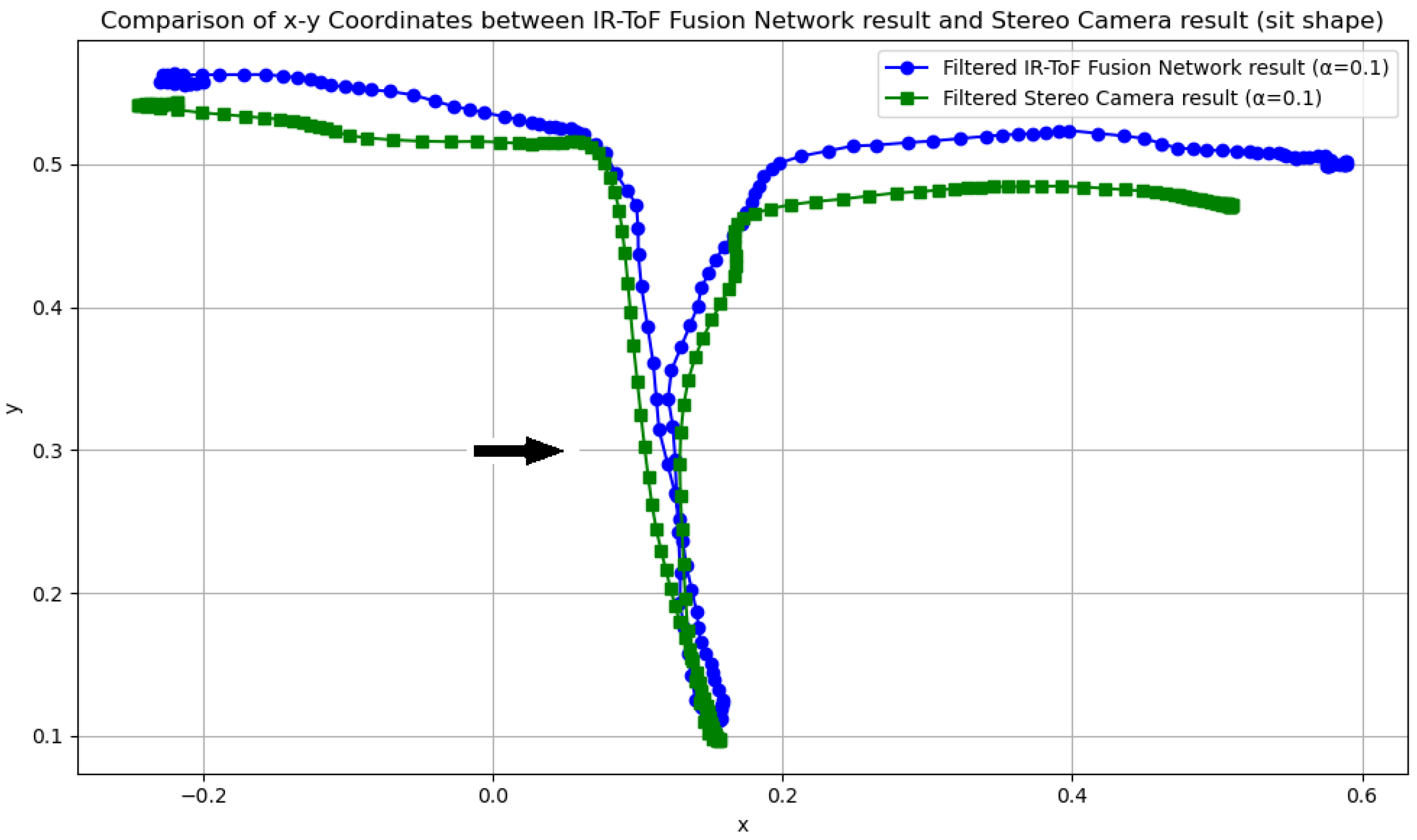

- Sit shape: The sit shape test is when the tester walks halfway through the test space, completes the sitting and standing movements, and then continues walking. It mainly tests the system’s tracking ability on the Y-axis (i.e., the change in height of the person). The result is shown as Figure 13. And the error metrics are shown as Table 10.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Privacy and Ethical Considerations

5.3. Analysis of System Performance and Limitations

5.4. Future Work

- Multi-Person Tracking: A primary direction is the development of multi-person tracking. This requires investigating optimal sensor placement (e.g., ceiling-mounting) to mitigate occlusion.

- Temporal Modeling for Occlusion Resilience: To address temporary occlusions (e.g., by furniture or self-occlusion), the current frame-by-frame model could be enhanced. Incorporating temporal models, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), LSTMs, or Transformers, would allow the system to predict a subject’s position based on motion history.

- Environmental Robustness: Future models should be trained to be more robust to thermal interference. This could involve dynamically adjusting the temperature filters based on ambient room temperature or developing a more sophisticated fusion logic that can differentiate human thermal patterns from static (e.g., heater) or sudden (e.g., sunlight) thermal noise.

- Generalizability via Federated Learning: The current model was trained in a specific environment. To improve generalizability across diverse home layouts and thermal conditions, Federated Learning is a promising approach. This would allow models to be collaboratively trained on datasets from multiple locations without centralizing raw sensor data, thus preserving user privacy.

- Hardware and Resolution Trade-offs: Further exploration of hardware, such as sensor grids, could further reduce identifiability risks. This must be balanced against the resulting loss in tracking accuracy, requiring a systematic study of the performance-privacy trade-off.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAL | Ambient Assisted Living |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| AoA | Angle of Arrival |

| AoD | Angle of Departure |

| BLE | Bluetooth Low Energy |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| EWMA | Exponentially Weighted Moving Average |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HAR | Human Activity/State Recognition |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IR | Infrared |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| NN | Neural Network |

| PIR | Passive Infrared |

| RGB-D | Red Green Blue-Depth |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RSSI | Received Signal Strength Indicator |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| ToF | Time-of-Flight |

References

- Cicirelli, G.; Marani, R.; Petitti, A.; Milella, A.; D’Orazio, T. Ambient Assisted Living: A Review of Technologies, Methodologies and Future Perspectives for Healthy Aging of Population. Sensors 2021, 21, 3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.; Gabralla, L.A.; Abubakar, S.; Chiroma, H. Detecting Elderly Behaviors Based on Deep Learning for Healthcare: Recent Advances, Methods, Real-World Applications and Challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 69802–69821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Islam, M.M.; Shehata, S.; Karray, F.; Quintana, Y. Smart Healthcare in the Age of AI: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145248–145270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, H.; Molyneaux, H.; Kondratova, I. Designing for Privacy and Technology Adoption by Older Adults. In Proceedings of the HCI International 2022 Posters, Virtual, 26 June–1 July 2022; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Camp, L.J.; Lorenzen-Huber, L.; Shankar, K.; Connelly, K. Privacy concerns in assisted living technologies. Ann. Telecommun. 2014, 69, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, N.A.Q.; Brady, A.M.; Ziefle, M.; Dinsmore, J. Barriers and Facilitators to Older Adults’ Acceptance of Camera-Based Active and Assisted Living Technologies: A Scoping Review. Innov. Aging 2024, 9, igae100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, P.; Wille, M.; Bröhl, C.; Theis, S.; Schäfer, K.; Knobe, M.; Mertens, A. Prevalence of Health App Use Among Older Adults in Germany: National Survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Lin, F.S. Exploring Older Adults’ Willingness to Install Home Surveil-Lance Systems in Taiwan: Factors and Privacy Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.B.; Zhang, Y.X.; Zhong, B.; Lei, Q.; Yang, L.; Du, J.X.; Chen, D.S. A Comprehensive Survey of Vision-Based Human Action Recognition Methods. Sensors 2019, 19, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, Z.; Nie, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Z. A Review on Human Activity Recognition Using Vision-Based Method. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 2017, 3090343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmacek, B.; Riveiro, M. Occupancy Prediction Using Low-Cost and Low-Resolution Heat Sensors for Smart Offices. Sensors 2020, 20, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, O.B.; Lazarescu, M.T.; Lavagno, L. Neural Networks for Indoor Person Tracking with Infrared Sensors. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2021, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newaz, N.T.; Hanada, E. A Low-Resolution Infrared Array for Unobtrusive Human Activity Recognition That Preserves Privacy. Sensors 2024, 24, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortenson, W.B.; Sixsmith, A.; Beringer, R. No Place Like Home? Surveillance and What Home Means in Old Age. Can. J. Aging/Rev. Can. Vieil. 2016, 35, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Sulaiman, N.A.A.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, S. A study of falling behavior recognition of the elderly based on deep learning. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 7383–7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Azhar, A.S.; Chin, W.; Kubota, N. Human Activity Recognition System Based on Continuous Learning with Human Skeleton Information. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 4713–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Hidalgo, G.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.E.; Sheikh, Y. OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S.; Climent-Pérez, P.; Florez-Revuelta, F. A Review on Visual Privacy Preservation Techniques for Active and Assisted Living. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 14715–14755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajari, S.; Kuruvinashetti, K.; Komeili, A.; Sundararaj, U. The Emergence of AI-Based Wearable Sensors for Digital Health Technology: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 9498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.; O’Shea, E.; Kenny, L.; Barton, J.; Tedesco, S.; Sica, M.; Crowe, C.; Alamäki, A.; Condell, J.; Nordström, A.; et al. Older adults’ experiences with using wearable devices: Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e23832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristoffersson, A.; Lindén, M. A Systematic Review of Wearable Sensors for Monitoring Physical Activity. Sensors 2022, 22, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, C.; Li, W.J.; Kang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, D.; Zhan, Z.; Chen, M.; Suo, J.; Zhao, Y. Enhanced Human Lower-Limb Motion Recognition Using Flexible Sensor Array and Relative Position Image. Pattern Recognit. 2026, 171, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dhanapal, R.K.; Ramakrishnan, P.; Balasingam, B.; Souza, T.; Maev, R. Active RFID Based Indoor Localization. In Proceedings of the 2019 22th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2–5 July 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; El-Tawab, S.; Yorio, Z.; Hilal, A. Indoor Localization Using 802.11 WiFi and IoT Edge Nodes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Conference on Internet of Things (GCIoT), Alexandria, Egypt, 5–7 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, M.; Ye, C.; Ohtsuki, T. Low-Resolution Infrared Array Sensor for Counting and Localizing People Indoors: When Low End Technology Meets Cutting Edge Deep Learning Techniques. Information 2022, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Kubota, N.; Hotta, K.; Sawayama, T. Behavior Estimation Based on Multiple Vibration Sensors for Elderly Monitoring Systems. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform. 2021, 25, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Shao, S.; Kubota, N. Heart Rate Measurement Using Air Pressure Sensor for Elderly Caring System. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Xiamen, China, 6–9 December 2019; pp. 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Tang, S.; Guo, P.; Niu, J. From Relative Azimuth to Absolute Location: Pushing the Limit of PIR Sensor Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, MobiCom ’20, London, UK, 21–25 September 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, B.; Sarangi, S.; Srirangarajan, S.; Kar, S. Indoor Localization Using Analog Output of Pyroelectric Infrared Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Barcelona, Spain, 15–18 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensing Modality | Advanced Applications | Indoor Positioning Accuracy | Privacy Risk Profile | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) | Fall detection, ADL recognition, gait analysis | Low | Low | Low |

| RGB Camera | ADL recognition, facial recognition | High | High | Medium |

| Depth Camera | Fall detection, ADL recognition, pose estimation | High | Medium | High |

| Thermal/IR | Fall detection, presence detection | Medium | Low-Medium | Low |

| mmWave Radar | Fall detection, ADL recognition, vital signs monitoring | High | Medium | High |

| Wi-Fi (Received Signal Strength Indicator, RSSI) | Fall detection | Low | Low | Low |

| BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) | Fall detection | Low (RSSI), High (AoA/AoD) | Low | Low (RSSI), High (AoA/AoD) |

| Acoustic (Mic. Array) | Event detection (falls, calls for help), voice interaction | High | High | Low |

| Environmental (Contact e.g.) | Presence detection | not applicable | Low | Low |

| Paper | Type of Sensor(s) | Objective | Notes | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al. [28] | 4 PIR | 2D Indoor Localization | Extracts “azimuth change” from raw PIR data and uses a particle filter for tracking. | Average localization error of approx. 0.64 m across all scenarios. |

| Mukhopadhyay et al. [29] | 4 PIR | 2D Indoor Localization | Estimates distance based on the “peak-to-peak value” of the analog PIR output. Uses Support Vector Regression (SVR) or multilateration to compute (x, y) coordinates. | RMS localization error of 0.65 m. |

| Tariq et al. [12] | 1 Thermopile ( Resolution) | 2D Indoor Tracking | Uses various neural networks (NNs), including one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-CNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM), to process raw sensor data directly without preprocessing. Sensor mounted on the ceiling of a m room. | Best RMSE of 0.096 m, achieved by the 1D-CNN model. |

| Bouazizi et al. [25] | 1 Thermopile (, , or Resolution) | 2D Indoor Localization and Counting | Uses deep learning and “super resolution” techniques to upscale low-resolution images for localization and counting. | For frames of size , detects a single person with accuracy 97.59% (means the proportion with an error of less than 0.3 m). |

| Newaz et al. [13] | 1 Thermopile ( Resolution) | Human Activity/State Recognition (HAR) | Uses a mathematical method and bilinear interpolation to detect states like “Sitting”, “Standing”, “Coming toward”, and “Going away”. | State Detection: “Standing Still” (98.9%), “Sitting Still” (96.7%), “Coming toward” (95.4%), “Going away” (95.1%). (Note: This is activity accuracy, not localization error in meters). |

| Item | Performance |

|---|---|

| Number of pixel | 64 (Vertical 8 × Horizontal 8 Matrix) |

| Frame rate | 10 fps |

| Output | Temperature |

| Temperature output resolution | 0.25 °C |

| Viewing angle | 60° |

| Item | Performance |

|---|---|

| Number of pixel | 64 (Vertical 8 × Horizontal 8 Matrix), or 16 (Vertical 4 × Horizontal 4 Matrix) |

| Frame rate | 15 fps |

| Output | Distance |

| Output resolution | 1 mm |

| Viewing angle | 45° |

| Parameter | Value/Setting |

|---|---|

| Data | |

| Batch Size | 32 |

| Shuffle | True |

| Data Source | CSV File |

| Parsing Method | ast.literal_eval |

| Optimization | |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning Rate (lr) | 0.001 |

| Loss Function | MSELoss (Mean Squared Error) |

| Training Control | |

| Validation Interval | Every 10 Epochs |

| Validation Metric | Average Euclidean Distance |

| Model Saving | Save model with lowest validation Euclidean distance |

| Metric | X | Y | Z | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (m) | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.095 | 0.172 |

| MSE (m2) | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.017 | 0.025 |

| Max Error (m) | 0.249 | 0.391 | 0.543 | (N/A) |

| Average Euclidean Distance (m) | 0.124 | |||

| Max Euclidean Distance (m) | 0.658 | |||

| Method | MSE (m2) | MAE (m) | Euclidean Distance (m) | Max X Error (m) | Max Y Error (m) | Max Z Error (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal sensor | 0.056 | 0.262 | 0.179 | 0.264 | 0.423 | 0.807 |

| ToF sensor | 0.099 | 0.4019 | 0.265 | 2.841 | 0.85 | 1.176 |

| Fusion | 0.025 | 0.172 | 0.124 | 0.249 | 0.391 | 0.543 |

| Error Type | X-Axis | Z-Axis | Total (X–Z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSE (m2) | 0.0036 | 0.0522 | 0.0279 |

| MAE (m) | 0.0465 | 0.1934 | 0.1199 |

| Maximum Error (m) | 0.1548 | 0.6630 | 0.6700 |

| Error Type | X-Axis | Z-Axis | Total (X–Z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSE (m2) | 0.0037 | 0.0213 | 0.0125 |

| MAE (m) | 0.0459 | 0.1244 | 0.0851 |

| Maximum Error (m) | 0.2162 | 0.3816 | 0.4386 |

| Error Type | X-Axis | Y-Axis | Total (X–Y) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSE (m2) | 0.0022 | 0.0010 | 0.0016 |

| MAE (m) | 0.0346 | 0.0273 | 0.0309 |

| Maximum Error (m) | 0.1178 | 0.0824 | 0.1226 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Q.; Kuwano, M.; Obo, T.; Kubota, N. Multi-Property Infrared Sensor Array for Intelligent Human Tracking in Privacy-Preserving Ambient Assisted Living. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212144

Song Q, Kuwano M, Obo T, Kubota N. Multi-Property Infrared Sensor Array for Intelligent Human Tracking in Privacy-Preserving Ambient Assisted Living. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212144

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Qingwei, Masahiko Kuwano, Takenori Obo, and Naoyuki Kubota. 2025. "Multi-Property Infrared Sensor Array for Intelligent Human Tracking in Privacy-Preserving Ambient Assisted Living" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212144

APA StyleSong, Q., Kuwano, M., Obo, T., & Kubota, N. (2025). Multi-Property Infrared Sensor Array for Intelligent Human Tracking in Privacy-Preserving Ambient Assisted Living. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 12144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152212144