Abstract

This study examines the seepage and damage behavior of coal under cyclic loading and unloading, typical in multi-layer coal seam mining. Four stress paths were designed: isobaric, stepwise, incrementally increasing, and cross-cyclic, based on real-time stress monitoring in protected coal strata. Seepage tests on gas-bearing coal were conducted using a fluid–solid coupled triaxial apparatus. The results show that axial compression most significantly affects axial strain, followed by volumetric strain, with minimal impact on radial strain. Permeability variation closely follows the stress–strain curve. Under isobaric cyclic loading (below specimen failure strength), specimens with higher initial damage (0.6) exhibit a sharp permeability decrease (75.47%) after the first cycle, with gradual recovery in subsequent cycles. In contrast, samples with lower initial damage (0.05) show higher permeability during loading, which eventually reverses, with unloading permeability surpassing loading permeability. Across all paths, a significant increase in residual deformation and permeability recovery exceeding 100% indicate the onset of instability. Continued cyclic loading increases damage accumulation, with different evolution patterns based on initial damage levels. These findings provide valuable insights into the pressure-relief permeability enhancement mechanism in coal seam mining and inform optimal gas drainage borehole design.

1. Introduction

High-gas outburst coal seam groups are widely distributed across China, where coal seams typically exhibit low initial permeability, inefficient gas extraction, and severe gas-related hazards [1,2,3]. The integration of protective layer pressure-relief mining and three-dimensional gas drainage technology is essential for mitigating these dynamic gas disasters [4,5,6]. In high-gas coal seam groups, multiple-protective-layer mining is frequently adopted. During this process, the protected seam is subjected to repeated mining disturbances, undergoing multiple cycles of loading and unloading [7,8,9]. When the protected seam is located at varying levels within the overburden after mining, the magnitude and trajectory of loading and unloading differ accordingly. These variations lead to discrepancies in permeability and damage evolution within the protected seam, resulting in distinct effects of pressure-relief permeability enhancement [10,11]. Therefore, studying the seepage and damage evolution of protected seams under different cyclic loading–unloading paths during multiple-protective-layer mining is of great significance for understanding the mechanisms of permeability enhancement and optimizing pressure-relief gas extraction in high-gas coal seam groups [12,13,14].

At present, extensive research has been conducted on the permeability evolution and damage characteristics of gas-bearing coal by numerous scholars [15,16,17]. Momeni et al. [18] studied revealed the three-stage evolution pattern of fatigue damage in granite through cyclic loading and unloading experiments. Mukherjee et al. [19] examined permeability controls in the sub-bituminous Walloon Coal Measures, finding that coal composition—especially telovitrinite content—primarily influences fracture intensity, while geological structures modulate this effect, jointly governing reservoir rheology. Casal et al. [20] investigated coal permeability evolution during thermal cycling in coking processes, showing that the alignment of maximum devolatilization with low-permeability zones controls pressure buildup under cyclic thermal loading. Wang et al. [21] used triaxial gas–solid coupling systems to demonstrate that the permeability of gas-bearing coal exhibits a logarithmic decline with increasing axial and confining stresses, and that cyclic loading–unloading induces cumulative permeability damage that intensifies with stress cycles. Liu et al. [22]’s study showed that the permeability of gas-bearing coal is highly sensitive to cyclic dynamic loading, with permeability evolution significantly influenced by loading frequency, amplitude, static stress level, and gas adsorption behavior. Li et al. [23] experimentally revealed that increasing pore pressure amplifies permeability loss, while coal exhibits axial compression and radial expansion during loading, with opposite responses during unloading, and that cumulative strain energy accumulation under higher pore pressures intensifies permeability reduction. Guo et al. [24] demonstrated that coal permeability evolution is jointly governed by effective stress, gas adsorption-induced deformation, and boundary conditions, which significantly influence coalbed methane (CBM) drainage efficiency and gas seepage behavior in coals. Yang et al. [25] revealed that cyclic loading significantly affects the stress–crack–permeability evolution within gas-bearing coal seams, demonstrating distinct permeability transition stages and strong correlations with acoustic emission characteristics during deformation. Fan et al. [26] demonstrated that the permeability evolution of coal, as a fractured dual-porosity medium, is strongly influenced by cyclic loading–unloading paths, stress history, and gas adsorption-induced deformation, which can cause significant permeability hysteresis and nonlinear stress–permeability coupling behavior. Ren et al. [27] revealed that coal permeability evolves differently under various mining-induced stress paths, such as protective coal mining, top-coal caving, and normal mining, and a new damage-based permeability model was proposed to characterize this behavior. Abdellah et al. [28] numerically simulated the mechanical behavior of various rocks under compression, revealing that strength and deformation are strongly influenced by confining pressure and loading rate.

In summary, although numerous studies have examined the evolution of permeability and damage characteristics of gas-bearing coal under single cyclic loading–unloading paths, comparative investigations of seepage behavior and damage evolution under multiple cyclic loading–unloading paths remain limited. A review of the mainstream literature over the past five years reveals that over 70% of studies focus exclusively on single fixed-amplitude paths, while research simultaneously involving and comparing three or more complex paths (such as intersecting or increasing paths) remains virtually nonexistent. This severe imbalance in research distribution has hindered in-depth exploration of the controlling influence on stress paths. Based on similarity simulation experiments that monitored the real-time stress state of protected coal bodies during coal seam group mining, this study designed four distinct cyclic loading–unloading stress paths; these four cyclic loading–unloading paths essentially encompass all stress conditions experienced by the protected coal body during coal seam group mining. Using a self-developed fluid–solid coupled triaxial seepage testing apparatus, permeability tests on gas-bearing coal were conducted under these four cyclic loading conditions. The objective was to elucidate the evolution patterns of permeability and damage in gas-bearing coal subjected to different cyclic stress conditions. The research outcomes offer valuable insights for understanding permeability enhancement mechanisms during pressure-relief mining of coal seam groups and for optimizing gas extraction strategies in such operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Setup

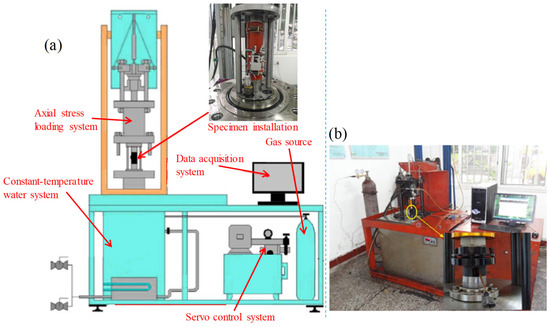

This study utilized a self-developed gas–heat fluid–solid coupling triaxial servo system. The schematic and physical configurations of the system are illustrated in Figure 1. This apparatus enables mechanical seepage testing of standard coal samples (Φ 50 mm × 100 mm) under various gas pressures, axial pressures, confining pressures, and temperatures. The axial pressure ranges from 0 to 100 MPa and the confining pressure from 0 to 20 MPa, both precisely regulated by the servo-loading system. Axial loading can be controlled in either force or displacement mode, with maximum axial deformation of 6 cm and circumferential deformation of 6 mm. Tests are conducted within a temperature range from ambient to 100 °C. Throughout the experiment, parameters including axial pressure, confining pressure, gas pressure, deformation, and flow rate are automatically recorded by the data acquisition system.

Figure 1.

Seepage test system of gas–heat fluid–solid coupling triaxial servo system. (a) Testing machine schematic diagram. (b) Physical image of testing machine.

2.2. Test Schemes

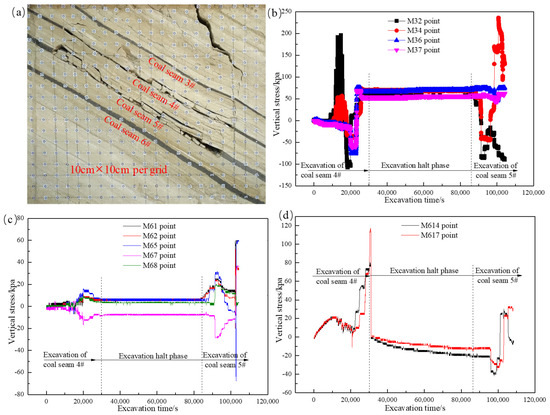

The authors previously conducted similarity simulation tests to monitor the real-time stress evolution of protected strata during the sequential mining of multiple protective layers within a coal seam group. The results of the similarity simulation model are presented in Figure 2a. During these tests, Coal Seams 4# and 5# were mined in sequence, and the stress conditions at various monitoring points in Coal Seams 6# and 3# were continuously recorded. The monitoring outcomes are shown in Figure 2b–d. As illustrated in Figure 2b, during the mining of Coal Seam 4#, the vertical stress at the monitoring point in Coal Seam 3# initially increased and then decreased, forming a complete loading–unloading cycle, with the peak vertical stress reaching approximately 200 kPa. During the suspension phase, the vertical stress remained nearly constant. In the subsequent mining of Coal Seam 5#, the vertical stress at the same monitoring points experienced another loading–unloading cycle, characterized by an increase followed by a decline, with a peak vertical stress of up to 235 kPa. The loading intensity during the first and second cycles at each monitoring point in Coal Seam 3# was approximately comparable. As shown in Figure 2c,d, during the excavation of Coal Seam 4#, the vertical stress at the monitoring point in Coal Seam 6# first rose and then dropped, forming a loading–unloading cycle with a maximum vertical stress of 120 kPa. During the mining suspension stage, the vertical stress at the monitoring point remained stable. When Coal Seam 5# was mined, the monitoring points in Coal Seam 6# again exhibited a loading–unloading process characterized by an initial increase followed by a reduction, with the peak vertical stress reaching about 60 kPa. However, the magnitude of loading and unloading differed among monitoring points in Coal Seam 6 during the two cycles. For points M61, M62, M65, M67, and M611, the intensity of the first cycle was lower than that of the second, whereas points M614 and M617 showed the opposite trend—the first cycle exhibited greater loading and unloading intensity than the second.

Figure 2.

Physical similarity simulation of multi-protective-layer mining and stress monitoring results at different points in the protected layer. (a) Similarity simulation model of the real-time stress evolution of protected strata during sequential mining of multiple protective layers within a coal seam group. (b) Stress state monitoring results at M32, M34, M36, and M37 monitoring points in Coal Seam 3# during the mining of Coal Seams 4# and 5#. (c) Stress state monitoring results at M61, M62, M65, M67, and M68 monitoring points in Coal Seam 6# during the mining of Coal Seams 4# and 5#. (d) Stress state monitoring results at M614 and M617 monitoring points in Coal Seam 6# during the mining of Coal Seams 4# and 5#.

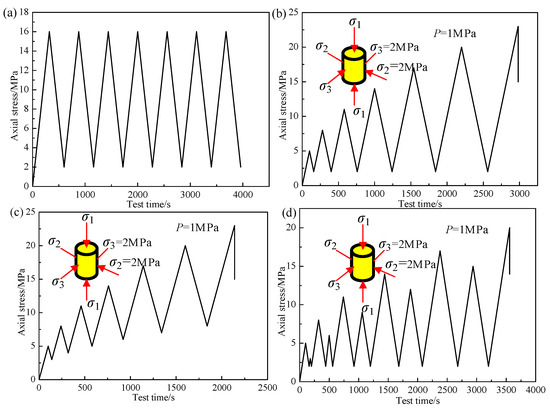

In summary, during the multi-protective mining of coal seam groups, the stress variation pattern within the protected layer exhibits repeated loading–unloading cycles. However, the magnitude of loading and unloading experienced at different monitoring points within the protected layer varies depending on their spatial locations. Three main patterns are observed: (1) the intensity of the previous loading–unloading cycle exceeds that of the subsequent one; (2) the intensity of the previous cycle is lower than that of the following cycle; and (3) both cycles exhibit approximately equal intensities. Based on these differences in stress states between adjacent loading–unloading cycles obtained from the similarity simulation results, four distinct cyclic loading–unloading paths were designed for the seepage tests, namely, isobaric cyclic loading–unloading, stepwise cyclic loading–unloading, incrementally stepwise cyclic loading–unloading, and cross-cyclic loading–unloading, as shown in Figure 3. The general testing procedure was as follows: ➀ Install the coal sample according to the specified requirements and fill the confining chamber with hydraulic oil. ➁ Apply axial and confining pressures at a loading rate of 0.1 kN/s until 2 MPa. Once stabilized, introduce gas pressure at 1 MPa and allow it to equilibrate. ➂ Upon completion, close the flowmeter and gas inlet, save the experimental data, and then release both axial and confining pressures before disassembling the specimen. This marks the end of one test cycle, after which subsequent cycles can be performed.

Figure 3.

Four different cyclic loading–unloading paths: (a) isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path, (b) stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path, (c) stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path, (d) cross-cyclic loading–unloading path.

2.3. Test Coal Sample

The coal specimens utilized in this study were obtained from the 1930 Coal Mine, situated in the Aiviergou mining area (Dabancheng District, Urumqi, Xinjiang, China). The mine extracts fat coal from the Jurassic Badaowan Formation, primarily from underground No. 4, 5, and 6 coal seams. The geological conditions are complex, featuring tectonic faults and a high water inflow risk. The mining depth ranges from the +2100 m to the +1800 m level.

Field coal samples were cored, cut, and polished into standard cylindrical specimens measuring 50 mm in diameter and 100 mm in length. For each seepage condition, two parallel tests were performed, yielding a total of eight test sets. The fundamental parameters of these specimens are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic information of test coal sample.

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Deformation and Permeability of Coal Samples Under Isobaric Cyclic Loading–Unloading Path

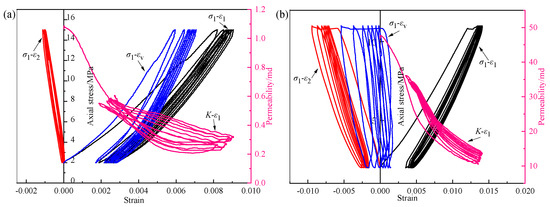

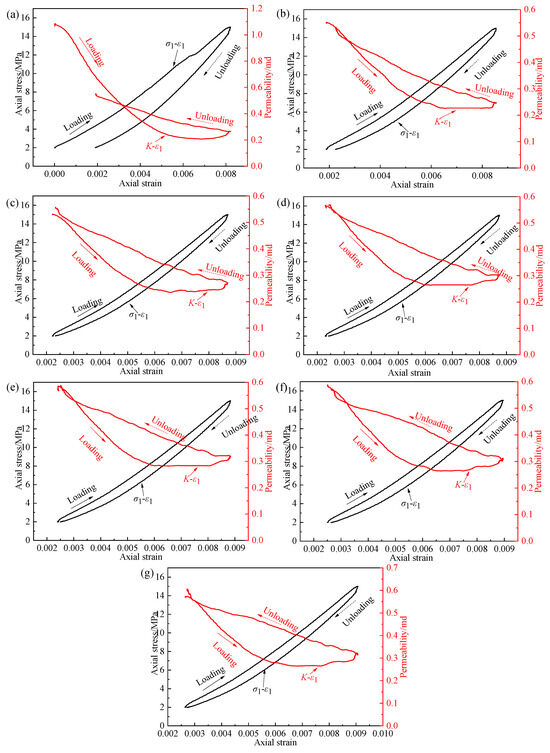

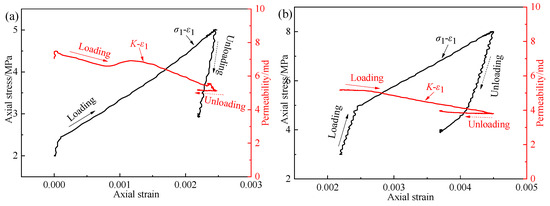

Two coal sample sets were subjected to isobaric cyclic loading–unloading seepage tests following the protocol in Figure 3. Their deformation and permeability evolution patterns are presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Strain and permeability curves of coal samples under isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) D1 coal sample; (b) D2 coal sample.

Figure 5.

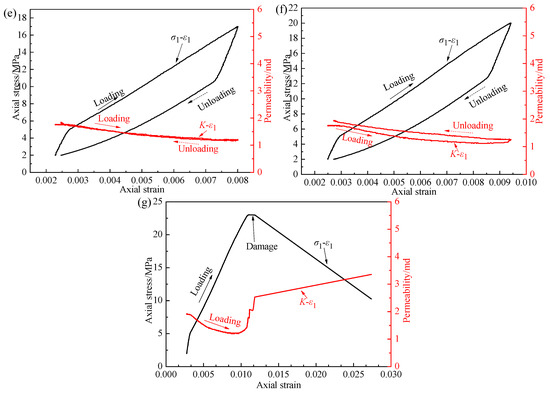

Stress–strain and permeability–strain curves of D1 coal sample at different cycle stages under isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) first cycle loading and unloading, (b) second cycle loading and unloading, (c) third cycle loading and unloading, (d) fourth cycle loading and unloading, (e) fifth cycle loading and unloading, (f) sixth cycle loading and unloading, and (g) seventh cycle loading and unloading.

As shown in Figure 4, axial loading and unloading have the most pronounced effect on axial strain, followed by volumetric strain, while radial strain is least affected. This suggests that the primary deformation occurs in the axial direction, with less influence in the radial direction under the given loading conditions.

In Figure 5, we observe that the hysteresis loop area of the D1 sample decreases most sharply after the first loading–unloading cycle, and this reduction becomes less significant in subsequent cycles. This behavior indicates a marked compaction of pores and fractures in the sample during the first cycle. Specifically, the D1 sample’s permeability decreases substantially after the first cycle (with a reduction rate of approximately 75.47%) and then gradually increases in later cycles. The unloading phase consistently exhibits higher permeability compared to the loading phase during each cycle. This can be attributed to the fact that, after the first cycle, many of the pores and fractures compact, resisting reopening during the unloading phase. Additionally, new microfractures form during the loading phase, causing permeability to increase in later cycles. During unloading, these newly formed fractures do not open significantly, so permeability remains higher in unloading than in loading. Moreover, the increase in permeability during later loading cycles is due to the continued generation and expansion of fractures with increased axial pressure (Figure 5b–g). This suggests that while the sample undergoes damage and compaction during the early cycles, it also experiences an increasing number of microfractures that enhance permeability during the loading phase.

Throughout the testing, permeability changes remain relatively smooth, which indicates that the maximum applied pressure in the isobaric loading–unloading tests did not exceed the sample’s failure strength. As a result, no catastrophic failure occurred, allowing the coal sample to retain structural integrity despite progressive damage.

3.2. Analysis of Deformation and Permeability of Coal Samples Under Stepwise Cyclic Loading–Unloading Path

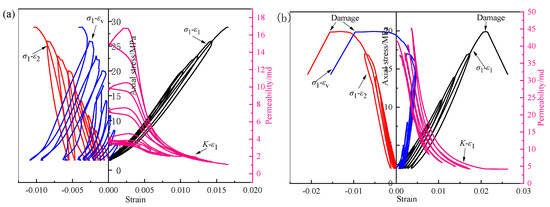

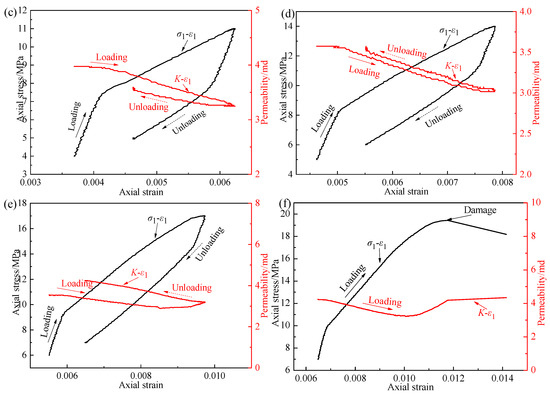

Two coal sample sets were subjected to stepwise cyclic loading–unloading seepage tests following the protocol in Figure 3. Their deformation and permeability evolution patterns are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Variation curves of strain and permeability of coal samples under stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) J1 coal sample; (b) J2 coal sample.

Figure 7.

Stress–strain and permeability–strain curves of J2 coal sample at different cycle stages under stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) first cycle loading and unloading, (b) second cycle loading and unloading, (c) third cycle loading and unloading, (d) fourth cycle loading and unloading, (e) fifth cycle loading and unloading, and (f) sixth cycle loading and unloading.

As shown in Figure 6, under stepwise cyclic loading–unloading conditions, axial compression has the greatest influence on axial strain, followed by volumetric strain, while radial strain is least affected. This indicates that most of the deformation occurs in the axial direction, with less influence on the radial direction during loading.

In Figure 7, the permeability behavior of the J2 sample shows a marked change across the cycles. During the first loading phase, permeability exceeds that in the unloading phase, suggesting that the sample is still in a relatively intact state with less compaction. However, upon returning to the initial stress state after unloading, permeability does not fully recover and remains significantly lower than in the loading phase. This observation indicates that some pore structures and fractures have been compacted and closed during the first loading cycle, restricting their ability to reopen during the unloading phase. In the second cycle, the permeability curve during loading intersects with that during unloading, and for the first time, the permeability during unloading partially surpasses the permeability during loading. This shift suggests that after the initial compaction, fracture expansion begins to dominate during loading. As loading proceeds, new microfractures are continuously formed, and some pores that were compacted during the first cycle may begin to reopen, particularly during the unloading phase. This reopening of pores and fractures under gas pressure leads to an increase in permeability during unloading, which surpasses the permeability during loading (see Figure 7b–e).

The stepwise cyclic loading path progressively increases peak values with each cycle, leading to the formation of additional cracks and pores. Consequently, permeable pathways expand over time, causing the difference between pre- and post-cycle permeability to widen. This indicates an increasing damage accumulation in the coal sample as the cyclic loading progresses. Finally, when the cyclic loading peak exceeds the sample’s failure strength, the sample undergoes failure, and the strain increases sharply (see Figure 7f). This dramatic increase in strain and the corresponding permeability changes indicate that the coal sample has reached its failure point, where further deformation and fracture propagation lead to a significant loss of structural integrity.

3.3. Analysis of Deformation and Permeability of Coal Samples Under Stepwise Incrementally Increasing Cyclic Loading–Unloading Path

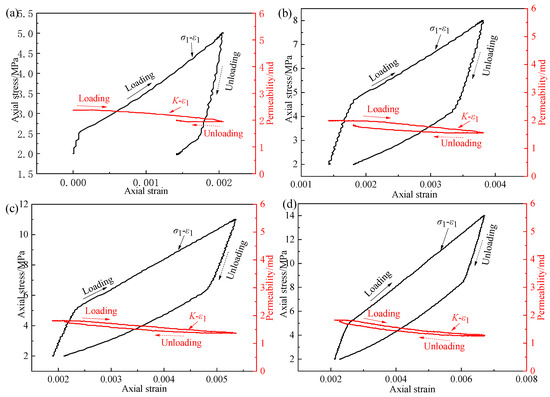

Two coal sample sets were subjected to stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading seepage tests following the protocol in Figure 3. Their deformation and permeability evolution patterns are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Change curves of strain and permeability of coal samples under stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) Z1 coal sample; (b) Z2 coal sample.

Figure 9.

Stress–strain and permeability–strain curves of Z1 coal sample in different cycle stages under stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) first cycle loading and unloading, (b) second cycle loading and unloading, (c) third cycle loading and unloading, (d) fourth cycle loading and unloading, (e) fifth cycle loading and unloading, and (f) sixth cycle loading and unloading.

As shown in Figure 8, the permeability of the coal sample under stepwise incremental cyclic loading–unloading generally follows the trend of the stress–strain curve, indicating a strong coupling between mechanical deformation and fluid flow.

Figure 9a–c show that during the first three cycles, the permeability of the Z1 sample is higher in the loading phase than in the unloading phase. This behavior is primarily controlled by compaction of pre-existing pores and fractures in the early cycles. Under axial compression, these pores and fractures gradually close, reducing the effective flow pathways, and they remain mostly closed during unloading, resulting in lower permeability in the unloading phase. After the third cycle, the deformation behavior changes. During subsequent loading, fracture expansion becomes the dominant mechanism, leading to the formation of new secondary fractures. These newly formed fractures provide additional flow channels, enhancing permeability. Simultaneously, pores and fractures that were loosened or formed during unloading can reopen under the influence of gas pressure, which further increases the permeability during the unloading phase. As a result, the unloading permeability eventually exceeds the loading permeability, as illustrated in Figure 9d–f.

Overall, the observed evolution of permeability reflects the transition from compaction-dominated behavior in the early cycles to fracture-expansion-dominated behavior in later cycles, highlighting the interplay between mechanical damage accumulation and fluid transport in coal under cyclic loading.

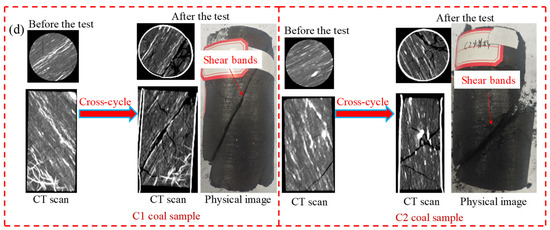

3.4. Analysis of Deformation and Permeability of Coal Samples Under Cross-Cyclic Loading–Unloading Path

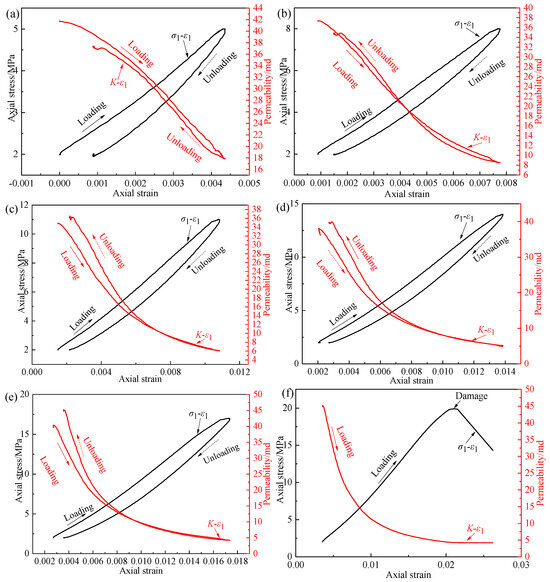

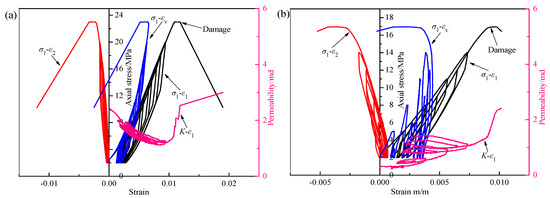

Cross-cyclic loading–unloading seepage tests were conducted on two coal samples following the plan in Figure 3, and their deformation and permeability evolution are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. Because the stress path alternates between large and small peak cycles, the permeability at each large peak follows the same stress–strain pattern; therefore, Figure 11 only presents permeability–strain and stress–strain curves for each major peak.

Figure 10.

Change curve of strain and permeability of coal samples under cross-cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) C1 coal sample; (b) C2 coal sample.

Figure 11.

Stress–strain and permeability–strain curves of C1 coal sample at different cycle stages under cross-cyclic loading–unloading path: (a) first cycle loading and unloading, (b) third cycle loading and unloading, (c) fifth cycle loading and unloading, (d) seventh cycle loading and unloading, (e) ninth cycle loading and unloading, (f) eleventh cycle loading and unloading, and (g) thirteenth cycle loading and unloading.

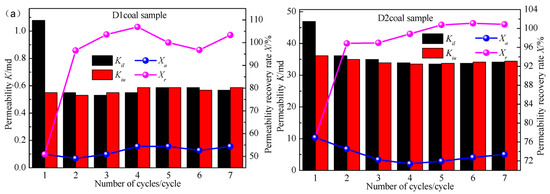

As illustrated in Figure 10, the permeability variation of coal samples under cross-cyclic loading and unloading shows a distinct correlation with the stress–strain evolution, similar to the other three loading–unloading paths. This pattern is further demonstrated in Figure 11a–d, where the permeability of coal sample C1 is higher during the loading phase than during unloading in the first four cycles. This difference is likely attributed to the increased compaction and pore structure alteration under loading, which initially reduces permeability. However, by the fifth cycle (Figure 11e), the permeability during loading and unloading approaches equality, indicating a balance in the material’s response to cyclic loading.

After the fifth cycle, as shown in Figure 11f,g, permeability during the unloading phase exceeds that during loading. This suggests that the coal sample undergoes a structural recovery or dilation during unloading, possibly due to the relaxation of stress and the reopening of pores that were compressed during loading. The increasing permeability during unloading may also be a result of accumulated microstructural changes that enhance pore connectivity and flow paths. The overall trend underscores the complex interplay between stress-induced compaction and recovery during the cyclic loading–unloading process.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Residual Deformation in Coal Samples Under Four Types of Cyclic Loading–Unloading Stress Path

To accurately analyze the deformation patterns of coal samples under four cyclic loading–unloading stress paths, this study employs cumulative residual deformation and relative residual deformation to examine the deformation characteristics of coal samples under these four cyclic stress paths. Cumulative residual deformation is defined as the difference between the deformation after each cyclic loading–unloading cycle and the deformation during the first loading cycle [29], calculated as follows:

In the equation, ∑εi denotes the cumulative residual deformation after the i-th cycle, εiu represents the deformation after loading and unloading during the i-th cycle, and ε1l indicates the deformation during the first loading cycle.

The permanent plastic deformation resulting from each cycle of loading and unloading is referred to as relative residual deformation, calculated using the following formula:

In the equation, Δεi denotes the relative residual deformation after the i-th cycle, and εil represents the deformation during the i-th loading cycle.

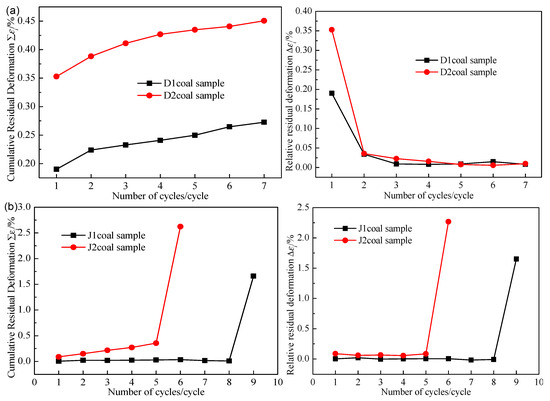

Substituting the deformation results from the four cyclic loading and unloading tests into Equations (1) and (2) yields the residual deformations at different stages of the four cyclic loading and unloading cycles, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Residual deformation at different cycle stages in four cycle loading–unloading paths: (a) isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path, (b) stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path, (c) stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path, and (d) cross-cyclic loading–unloading path.

As shown in Figure 12, due to the relatively large initial damage of the coal sample under the isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path, and since the maximum loading pressure in the isobaric cyclic loading–unloading test did not exceed the sample’s failure strength, the relative residual deformation reached its maximum during the first cyclic loading–unloading cycle. In subsequent cycles, the deformation decreased sharply and remained relatively consistent, without exhibiting the abrupt increase typically associated with sample failure instability. The patterns of cumulative residual deformation and relative residual deformation under the remaining three cyclic loading–unloading paths were consistent. Cumulative residual deformation gradually increased with the number of cycles, exhibiting a sharp increase upon sample failure. Relative residual deformation underwent three distinct phases throughout the cyclic loading–unloading process: initial pore compaction, elastic phase, and sample yielding phase. During the pore compaction stage, primary pores and fractures within the coal sample gradually close during loading. After unloading, these compacted pores and fractures cannot fully recover, resulting in significant irreversible deformation. Consequently, relative residual deformation gradually decreases during compaction. In the elastic stage, deformation generated during loading is largely recovered during unloading, leading to relatively stable and minimal changes in relative residual deformation. During the yield stage, the coal sample generates numerous new secondary fractures and pores that continuously expand under loading. The deformation incurred during loading becomes irreversible upon unloading, causing the relative residual deformation to steadily increase until it surges dramatically at the point of failure and instability. In summary, the abrupt increase in relative residual deformation serves as a precursor to failure and instability. Monitoring the deformation patterns of coal bodies is therefore crucial for predicting their failure and instability.

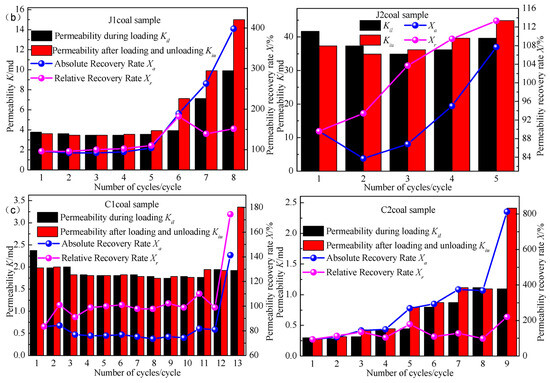

4.2. Analysis of Permeability Recovery Rates in Coal Samples Under Four Types of Cyclic Loading–Unloading Stress Path

To accurately analyze the variation patterns of permeability in coal samples under four cyclic loading–unloading stress paths, this study employs both absolute permeability recovery and relative permeability recovery to characterize permeability behavior under these four cyclic stress conditions. The absolute permeability recovery rate is defined as the ratio of permeability after each cyclic loading–unloading cycle to the permeability during the first loading cycle [30], calculated as follows:

In the equation, Kiu denotes the permeability after the i-th loading–unloading cycle, and K1l denotes the permeability during the first loading cycle.

The ratio of the permeability after each loading–unloading cycle to the permeability during the current loading cycle is referred to as the relative permeability recovery rate. Its calculation formula is as follows:

In the equation, Kil denotes the permeability during the i-th cyclic loading.

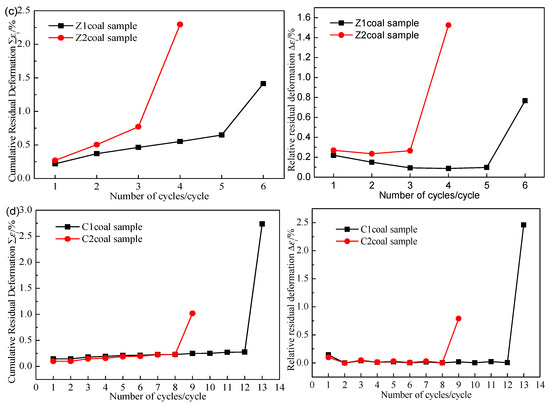

As the axial compressive stress at the end of each cycle increases with the number of cycles in the stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path, the initial and unloading axial compressive stresses differ for each cycle. Consequently, the absolute and relative permeability recovery rates at various stages cannot be calculated using Equations (3) and (4). Therefore, permeability data from the remaining three cyclic loading–unloading tests were substituted into Equations (3) and (4) to determine the permeability recovery rates at different stages, as illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Permeability recovery rate at different cycle stages of three cycle loading and unloading paths: (a) isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path, (b) stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path, and (c) cross-cyclic loading–unloading path.

As shown in Figure 13, the absolute permeability recovery rate of coal samples D1 and D2 gradually increases with the number of loading–unloading cycles. In contrast, the relative permeability recovery rate first decreases and then gradually rises. The main reasons are as follows: these coal samples experienced substantial initial damage, resulting in wider initial fissures. During the first loading phase, the area of fissure closure exceeded that of newly formed secondary fractures, causing a reduction in permeability. After several cycles, the closure area became smaller than the area of newly generated fractures, leading to a gradual increase in permeability. For coal samples J1, C1, and C2, both absolute and relative permeability recovery rates increased slowly at first, then sharply at failure. This is because the initial damage of these samples was minor, and throughout cyclic loading–unloading, the formation of new fractures during loading consistently exceeded the closure of existing ones. Consequently, cumulative damage intensified, and permeability rose steadily until it surged during failure. Furthermore, Figure 13 shows that the relative permeability recovery rate exceeded 100% before failure, indicating that it can serve as a precursor to instability—when the relative recovery rate surpasses 100%, the coal sample is approaching failure.

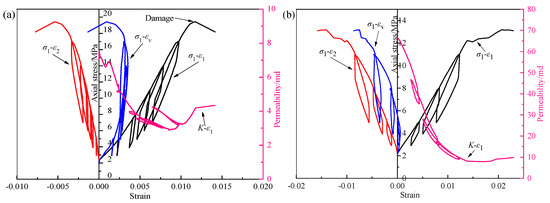

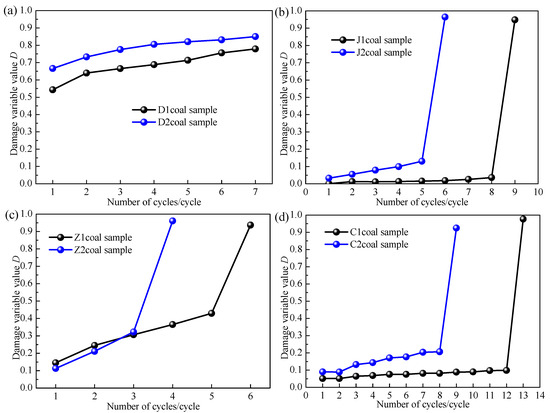

4.3. Analysis of Damage Characteristics in Coal Samples Under Four Types of Cyclic Loading–Unloading Stress Path

To evaluate the degree of damage in coal rock under loading conditions, an elastic modulus-based method was adopted. Using the damage equation for elastoplastic materials with one-dimensional irreversible plastic deformation proposed in Reference [31], the damage and failure behavior of coal samples at various stages under four different cyclic loading–unloading paths were analyzed. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the equation, D represents the damage variable value of the coal sample, εei denotes the residual plastic strain after the i-th loading–unloading cycle of the coal sample, ε indicates the axial strain of the coal sample, E signifies the initial elastic modulus of the coal sample, and Ei represents the elastic modulus during the i-th loading–unloading cycle of the coal sample.

The test results of the eight specimen groups under the four cyclic loading–unloading paths were substituted into Equation (5) to calculate the damage variables at different stages of the four cyclic loading–unloading paths for the eight specimen groups, as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Damage variable values at different cycle stages under four cycle loading and unloading paths: (a) isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path, (b) stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path, (c) stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path, and (d) cross-cyclic loading–unloading path.

As shown in Figure 14, coal sample damage increased progressively with cyclic loading–unloading. However, the damage evolution patterns varied depending on initial sample conditions. Samples with high initial damage exhibited substantial early damage that continued to grow steadily across cycles. This observation supports earlier findings that the loading phase contributes to ongoing damage accumulation. Samples with low initial damage showed minimal early degradation, with gradual damage growth until the applied axial stress exceeded the coal strength, triggering rapid damage escalation and failure.

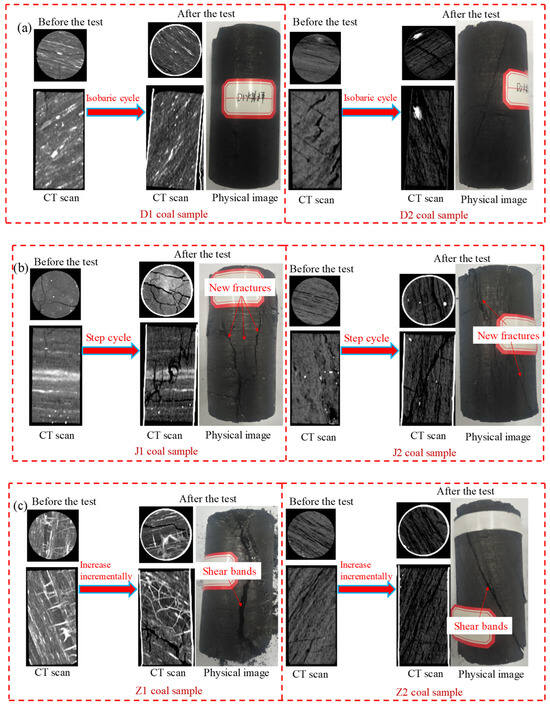

X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans were performed using a SOMATOM Ccope (Shanghai, China) system before and after the seepage test to detect internal damage within the specimens. Scan parameters were set to a tube voltage of 345 kV and a current of 130 μA. Acquisition parameters were set to a slice thickness of 1 mm and an image pixel resolution of 1024 × 1024. By comparing CT slices of damaged and undamaged specimens, microcracks, voids, and other damage features were identified and qualitatively analyzed. The scan results are shown in Figure 15. As seen in samples D1 and D2, tested under isobaric loading–unloading paths, the applied pressure did not exceed their failure strength, so both remained intact after testing (Figure 15a). In contrast, low-damage samples (J1, J2, Z1, Z2, C1, and C2) exhibited gradual damage accumulation followed by a sharp increase in the yield stage, leading to shear failure (Figure 15b–d).

Figure 15.

CT and physical images of coal samples before and after the test under four cyclic loading and unloading paths: (a) isobaric cyclic loading–unloading path, (b) stepwise cyclic loading–unloading path, (c) stepwise incrementally increasing cyclic loading–unloading path, and (d) cross-cyclic loading–unloading path.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

To explore the permeability evolution and damage characteristics of gas-bearing coal under different cyclic loading conditions, this study designed four cyclic loading–unloading stress paths based on real-time stress monitoring from a similarity simulation experiment of protected coal seams during multi-seam mining. Permeability tests were conducted using a self-developed fluid–solid coupled triaxial seepage apparatus. The main findings are as follows:

- (1)

- Among the four cyclic loading–unloading paths, axial compression exerted the strongest influence on axial strain, followed by volumetric strain, while radial strain was least affected. The permeability variation closely corresponded to the stress–strain behavior of the coal samples.

- (2)

- Under isobaric cyclic loading and unloading (with stresses below the sample’s failure strength), specimens with greater initial damage (0.6) showed a significant permeability drop (75.47%) after the first cycle, followed by gradual recovery during subsequent cycles.

- (3)

- Under stepwise, incrementally increased, and cross-cyclic loading–unloading paths, samples with minor initial damage (0.05) initially showed higher permeability during loading than unloading. As cycling continued, permeability during both phases converged, eventually becoming higher in the unloading phase.

- (4)

- A sharp rise in relative residual deformation and a relative permeability recovery rate exceeding 100% were identified as precursors to coal sample failure instability across all four loading paths, and the relative permeability recovery rate exceeding 100% may serve as a quantitative failure criterion.

- (5)

- Damage accumulation in coal samples increased progressively with the number of cycles. However, the evolution pattern depended on the initial damage level. Highly damaged samples experienced rapid deterioration from the start, whereas those with minimal initial damage exhibited gradual degradation until failure occurred once the axial compressive stress exceeded the sample strength.

Looking ahead, the experimental laws and quantitative precursors identified in this study provide a solid empirical foundation for future theoretical work. A primary subsequent step will be to develop a micromechanics-based constitutive model that can capture the observed hysteresis and path-dependent behavior. The robustness of such a model should then be verified through numerical simulations under contrasting scenarios, as a direct extension of this experimental research.

Author Contributions

Data Curation, B.L.; Funding Acquisition, B.L. and Y.L. (Yunpei Liang); Methodology, J.W.; Validation, Y.L. (Yong Li) and Z.M.; Writing—Original Draft, B.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.L. (Yunpei Liang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52204132 and 52174166) and the Independent Research Project of State Key Laboratory for Fine Exploration and Intelligent Development of Coal Resources, CUMT (SKLCRSM24X002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with this research are available and can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support received from Yong Yuan in data analysis and manuscript editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Li, Z.; Wei, G.; Liang, R.; Shi, P.; Wen, H.; Zhou, W. LCO2-ECBM technology for preventing coal and gas outburst: Integrated effect of permeability improvement and gas displacement. Fuel 2021, 285, 119219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xu, J.; Peng, S.; Qin, L.; Yan, F.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, B. Influence of different coal seam gas pressures and their pulse characteristics on coal-and-gas outburst impact airflow. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 2749–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Shi, J.; Wilkins, A. A Numerical Evaluation of Coal Seam Permeability Derived from Borehole Gas Flow Rate. Energies 2022, 15, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Gong, H.; Wang, G.; Yang, X.; Xue, H.; Du, F.; Wang, Z. N2 injection to enhance gas drainage in low-permeability coal seam: A field test and the application of deep learning algorithms. Energy 2024, 290, 130010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wang, M. Study on Deep Hole Blasting for Roof Cutting, Pressure Relief and Roadway Protection in Deep Multi-Coal Seam Mining. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Fu, H.; Huo, B.; Fan, C. Permeability enhancement of coal seam by lower protective layer mining for gas outburst prevention. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 8878873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhao, C.; Guo, H. Collaborative gas drainage technology of high and low level roadways in highly-gassy coal seam mining. Fuel 2022, 323, 124325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, B. Variation characteristics of coal rock layer and gas extraction law of surface well under mining pressure relief. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, H. Stress sensitivity of permeability in the loading and unloading process of broken coal-rock masses under different influencing factors. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 080701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zou, Q.; Liang, Y. Experimental research into the evolution of permeability in a broken coal mass under cyclic loading and unloading conditions. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.; Song, D.; Li, Z.; He, X.; Dou, L.; Xue, Y.; Yang, H. Numerical simulation study on pressure-relief effect of protective layer mining in coal seams prone to rockburst hazard. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 6421–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zou, Q. Seepage and damage evolution characteristics of gas-bearing coal under different cyclic loading–unloading stress paths. Processes 2018, 6, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, L.; Pan, J.; Li, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, S. Evolution of Broken Coal’s Permeability Characteristics under Cyclic Loading–Unloading Conditions. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 2279–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, X.; Xu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Chen, B. Evolution of gas permeability and porosity of sandstone under stress loading and unloading conditions. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 087149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Wang, E.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Yao, W. Resistivity and damage of coal under cyclic loading and unloading. Eng. Geol. 2023, 323, 107234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Tian, S.; Zeng, S.; Hao, D. Permeability and Stress Sensitivity of Coals with Different Fracture Directions Under Cyclic Loading–Unloading Conditions: A Case Study of the Xutuan Coal Mine in Huaibei Coalfield, China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Liu, Q.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, J.; Majid, K.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Guo, M.; Hong, T. Experimental study on resistivity evolution law and precursory signals in the damage process of gas-bearing coal. Fuel 2024, 362, 130798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, A.; Karakus, M.; Khanlari, G.R.; Heidari, M. Effects of cyclic loading on the mechanical properties of a granite. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 77, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Rajabi, M.; Esterle, J. Relationship between coal composition, fracture abundance and initial reservoir permeability: A case study in the Walloon Coal Measures, Surat Basin, Australia. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2021, 240, 103726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, M.D.; Díaz-Faes, E.; Alvarez, R.; Díez, M.A.; Barriocanal, C. Influence of the permeability of the coal plastic layer on coking pressure. Fuel 2006, 85, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, X.; Cui, B.; Hao, J.; Chen, P. Study on the Permeability Change Characteristic of Gas-Bearing Coal under Cyclic Loading and Unloading Path. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 5562628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Evolution of permeability and sensitivity analysis of gas-bearing coal under cyclic dynamic loading. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, C.; Zhou, B.; Shuang, H.; Lin, H.; Peng, S.; Liu, H. Deformation and Seepage Characteristics of Gassy Coal Subjected to Cyclic Loading–Unloading of Pore Pressure. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 2775–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, K.; Qu, B.; Yuan, L.; Xu, C. Coal permeability evolution characteristics: Analysis under different loading conditions. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cao, J.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; Guo, J. Mechanical response characteristics and permeability evolution of coal samples under cyclic loading. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 1588–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, S. Evaluation of permeability damage for stressed coal with cyclic loading: An experimental study. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 216, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Li, B.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J. Coal permeability evolution during damage process under different mining layouts. Energy Sources Part A 2025, 47, 4010–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, W.R.; Bader, S.A.; Kim, J.G.; Ali, M.A.M. Numerical simulation of mechanical behavior of rock samples under uniaxial and triaxial compression tests. Mining Miner. Depos. 2023, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Guo, Y.; Xu, H.; Dong, H.; Du, F.; Huang, Q. Deformation and permeability evolution of coal during axial stress cyclic loading and unloading: An experimental study. Geomech. Eng. 2021, 24, 519–529. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, M.; Jiang, C.; Xing, H.; Zhang, D.; Peng, K.; Zhang, W. Study on damage of coal based on permeability and load-unload response ratio under tiered cyclic loading. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielski, J.; Skrzypek, J.J.; Kuna-Ciskal, H. Implementation of a model of coupled elastic-plastic unilateral damage material to finite element code. Int. J. Damage Mech. 2006, 15, 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).