Abstract

Current power systems are facing noticeable power quality (PQ) performance deterioration, which has been attributed to nonlinear loads, distributed generation, and extensive renewable energy infiltration (REI). These conditions cause voltage sags, harmonic distortion, flicker, and disadvantageous power factors. The traditional PI/PID-based scheme of control, when applied to Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTSs), demonstrates low adaptability and low anticipatory functions, which are required to operate a grid in real-time and dynamic conditions. Artificial Intelligence (AI) opens proactive, reactive, or adaptive and self-optimizing control schemes, which reformulate FACTS to thoughtful, data-intensive power-system objects. This literature review systematically studies the convergence of AI and FACTS technology, with an emphasis on how AI can improve voltage stability, harmonic control, flicker control, and reactive power control in the grid formation of various types of grids. A new classification is proposed for the identification of AI methodologies, including deep learning, reinforcement learning, fuzzy logic, and graph neural networks, according to specific FQ goals and FACTS device categories. This study quantitatively compares AI-enhanced and traditional controllers and uses key performance indicators such as response time, total harmonic distortion (THD), precision of voltage regulation, and reactive power compensation effectiveness. In addition, the analysis discusses the main implementation obstacles, such as data shortages, computational time, readability, and regulatory limitations, and suggests mitigation measures for these issues. The conclusion outlines a clear future research direction towards physics-informed neural networks, federated learning, which facilitates decentralized control, digital twins, which facilitate real-time validation, and multi-agent reinforcement learning, which facilitates coordinated operation. Through the current research synthesis, this study provides researchers, engineers, and system planners with actionable information to create a next-generation AI-FACTS framework that can support resilient and high-quality power delivery.

1. Introduction

1.1. Power Quality Challenges in Modern Grids

In modern power grids, maintaining power quality (PQ) is challenging owing to the increased infiltration of nonlinear loads of various forms, distributed energy resources (DERs), and renewable energy sources. The efficient planning of electric power systems is essential to meet both the current and future energy demands. In this context, reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a promising tool for control problems modeled as Markov decision processes (MDPs). Recently, its application has been extended to the planning and operation of power systems. This study provides a systematic review of advances in the application of RL and deep reinforcement learning (DRL) in this field. The problems are classified into two main categories: Operation planning including optimal power flow (OPF), economic dispatch (ED), and unit commitment (UC) and expansion planning, focusing on transmission network expansion planning (TNEP) and distribution network expansion planning (DNEP). The theoretical foundations of RL and DRL are explored, followed by a detailed analysis of their implementation in each planning area. This includes the identification of learning algorithms, function approximators, action policies, agent types, performance metrics, reward functions, and pertinent case studies. Our review reveals that RL and DRL algorithms outperform conventional methods, especially in terms of efficiency in computational time. These results highlight the transformative potential of RL and DRL in addressing complex challenges within power systems. These factors cause voltage sags, flickers, harmonics, and poor power factors, thus negatively affecting industrial, commercial, and residential infrastructures [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Traditional proportional-integral (PI) or proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers often fail to adapt well to such dynamic conditions. This failure is especially severe in an industrial environment, such as semiconductor manufacturing, where a PQ lapse can cause losses of up to USD 90,000 to even USD 1 million hourly. The use of renewable energy sources can also cause additional complexities, such as harmonics generated by inverters and the introduction of stochastic changes in production. Modern microgrids are more susceptible to such disruptions, which may cause disruption of sensitive electronic components and interfere with the production processes. IEEE Standard 1159-2019 [7,8] categorizes power quality phenomena according to their magnitude, duration, and spectral characteristics, and establishes measurement protocols and acceptance thresholds for diverse operating environments. The installation of renewable energy sources creates further complications in the regulation of power quality, such as inverter-generated harmonics, fluctuations in resource production settings, and unaligned phases in distribution networks. Modern microgrids are particularly vulnerable to these disturbances and can experience fast transients (or even rapidly moving clouds) that disrupt sensitive electronic devices and manufacturing processes [9]. These challenges necessitate an intelligent adaptive control paradigm capable of operating under uncertainty, ensuring a real-time response, and maintaining consistent PQ in distributed systems. Traditional proportional integral (PI)/PID-based controllers are inadequate in these environments. This encourages the combination of power-electronic-based modern devices with Artificial Intelligence (AI), which has the potential to predict, self-optimize, and scale control strategies for power quality enhancement [10].

1.2. FACTS Devices, Principles and Capabilities

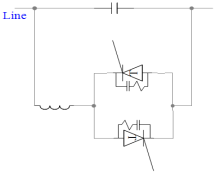

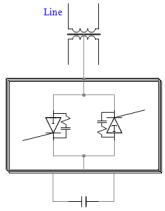

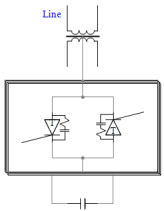

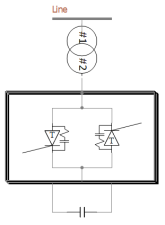

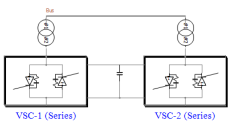

FACTS is a decisive element in the development of the quality of power and stability of systems by dynamically regulating the values of line parameters, such as voltage, impedance, and phase angle [11,12]. The power electronic controllers underneath it can quickly inject or accept reactive power, which is used to stabilize the voltage levels, increase the transmission capacity, and reduce transient disturbances [9,13]. Its main benefits include controlled load flow, reduced generation costs, enhanced stability, and minimized reactive power losses [12,14]. FACTS devices can be classified as shunt compensators (e.g., SVC and STATCOM), series compensators (e.g., TCSC), or hybrid devices (e.g., UPFC and IPFC), each designed to perform a unique role, such as voltage regulation, harmonic mitigation, and power flow management [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. However, traditional FACTS control methods demonstrate limitations in flexibility, which supports the need for more innovative and data-targeted control paradigms in modern grids typified by high influxes of distributed energy resources [23,24,25,26,27]. As illustrated in Figure 1, power quality disturbances affect the stability of the grid and equipment operation.

Figure 1.

Overview of Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTS).

1.3. Limitation of Conventional FACTS Control

Traditional FACTS control schemes, the models of which are usually based on PI regulators, rely on statistical parameters resulting from small-signal analyses and tuning through trial and error. These methods are satisfactory in the operating conditions of steady-state conditions, but display extreme deficiencies in modern power systems [11]. First, they are not predictable, particularly within the framework of integrating renewable energy, which leads respondents to not implement control policies. Second, the restrained flexibility requires manual retuning when the user changes the network settings and load profiles. Third, the approaches face challenges in multi-objective optimization when the power quality goals are incompatible with other operational goals [2,12]. These limitations highlight the need for intelligent controllers that not only react to but also allow the prevention of disturbances in advance, which artificial intelligence methods are beginning to provide [28,29].

1.4. Artificial Intelligence Controllers

FACTS control is being reshaped by artificial intelligence (AI) to allow real-time optimization with adaptive and predictive capabilities. Neural networks, fuzzy logic, and evolutionary algorithms can improve the performance of FACTS more than traditional methods can [15,30,31]. Unlike conventional methods, AI can use historical data to learn control and be optimized heuristically, thus proving to be especially effective in handling the issue of power quality under intricate grid conditions [11,12,31]. Recent studies have shown that AI can be utilized to enhance the audit of power quality, such as the control of harmonic distortion and the forecasting of voltage sag [32,33,34]. Such abilities can be particularly useful in microgrids and systems that typically use renewable resources, where dynamic variations and inverted power can occur [2,12,14]. Deep learning, fuzzy, and reinforcement learning have shown promising results; however, they have not been systematically analyzed to comprehend how various AI tools can be applied to tackle specific power quality concerns and the use of FACTS applications, particularly in light of practical implementation challenges such as explainability, real-time operation, and data requirements.

1.5. Research Gaps and Paper Contributions

This review determines the essential gaps in the research on AI integration with Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTS) in four main ways.

- Systematic Classification of AI Solutions to PQ-Focused FACTS Control: This study develops a new taxonomy based on which AI methods, including Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Graph Neural Networks (GNN), fuzzy logic, and reinforcement learning, are classified in respect to their ability to be used with a particular device and power quality targets. Taxonomy is classified in terms of control functionality, which can be voltage sag mitigation, harmonic suppression, and flicker reduction, consequently offering a guide on the relevant choice of AI models for each application.

- Quantitative analysis of AI-enhanced versus traditional Controllers: The study conducts a strict performance analysis of the AI-enhanced FACTSs in comparison to the traditional PI/PID controllers. Various power quality tests were analyzed, including the accuracy of voltage regulation, total harmonic distortion (THD) reduction, flicker reduction, response time, and effectiveness of reactive power compensation.

- Assessment of practical implementation issues: The authors evaluated the practical limitations of deployment, which comprise computational latency, model integrity, interpretability, and data quality, in addition to integration with the existing grid infrastructure. Special attention is paid to the differences in simulation results and hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) or field-level models.

- Roadmap to Future Research and Future Trends: Future promising research opportunities are nominated, including the use of digital twins to validate AI-FACTS, federated learning to create distributed intelligence, physics-based neural networks (PINNs) to create constraint-based control, and multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) to achieve coordinated microgrid control.

Together, these works address the gap between theoretical AI-FACTS studies and actual implementation and provide a new framework for future development of smart grids, in the presentation of applications of AI in smart grids. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides background information on the basic types of power quality disturbances and their effects on the performance of modern power grids. Section 3 provides an overview of the proposed advanced AI techniques, such as deep learning, reinforcement learning, and hybrid techniques, which are applied to power system control. Section 4 presents the manner in which such AI techniques have been combined with FACTS devices to enhance power quality parameters such as voltage stability, harmonic filtering, and flicker limitation. Section 5 describes the implementation issues, such as computational limitations, sensor accuracy, and interoperability. Section 6 concludes the paper, summarizes the findings, and lays out future ways in which intelligent and AI-assisted FACTSs can be achieved in a smart grid environment.

2. Overview of Power Quality Issues and FACTS Solutions

The definition of power quality (PQ) disturbances can incorporate a range of deviations in voltage, current, or frequency, with the capacity to impair the normal operation of equipment. In the current IEEE 1159-2019 standard [7]. PQ issues are categorized into several classes based on their severity, duration, and frequency of occurrence (FO). Such instabilities, whether transient or steady-state, are becoming increasingly significant problems in modern grids, especially those with large amounts of nonlinear loads and low renewable energy penetrations. In order to be able to plan effective control strategies, all these phenomena must be classified and their effect on grid reliability and operational efficiency understood.

2.1. Classification of Power Quality Disturbances and Cost Loss

PQ is defined as the set of electrical characteristics that allows electrical equipment to function properly without any significant loss of performance or life expectancy [12]. Various power quality disturbances are discussed in the following sections.

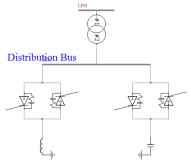

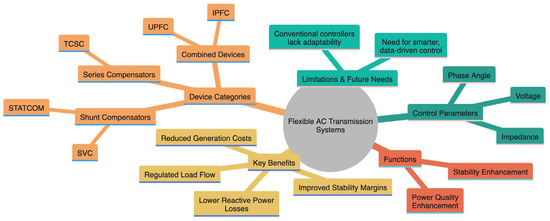

These disturbances have significant economic and operational impacts on industries worldwide. In industrial sections, equipment lifetime is reduced, and power losses are increased owing to problems that can affect the grid power quality. Interruption costs are related to faults in equipment repair, damaged products during the production stage, spoiled raw materials, protection systems, energy backup systems, and additional staff working hours. In some sectors, the loss can be staggering; per-minute interruption costs in the chemical sector reach approximately $135,000, in the food industry about $2500, and in the mechanical sector around $75,000 [35,36,37]. From a high-level perspective, power supply variations and voltage disturbances cost approximately $119 billion per year for industrial facilities in the US, according to an Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) report. In the meantime, 25 EU states suffer the equivalent of $160 billion in financial losses per year due to improper ID PQ [38,39]. This classification is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Power quality disturbances.

2.1.1. Voltage Magnitude Variations

Voltage Sags (Dips)

The disturbance caused by a reduction in the root mean square (RMS) voltage at 0.1 to 0.9 per unit over 0.5 cycles up to 1 min is called a voltage sag. As shown in industry data, the percentage of power quality disturbances experienced in industrial premises is about 70 per cent due to voltage sag [11,40,41]. Sags are generally categorized based on the level (strength) and duration, with severity increasing with increasing levels [40]. The major sources of such agitation are system faults (line-to-line, line-to-ground, etc.), large motor starting (in-rush current), transformer energization, and heavy load switching [42]. The mathematical characterization of this phenomenon is as follows:

where is the sag voltage (between 0 and 1), is the actual voltage level measured during the sag event, and is the standard operating voltage of the electrical system.

Voltage Swells

It is a transient rise in RMS voltage between 1.1 and 1.8 per unit occurring over a duration of 0.5 cycles to 1 min [37]. The formula associated with this fault is identical to that of a voltage sag. They are less common than sags, but may be equally dangerous and comparable [35,40]. The usual causes are line-to-ground faults (no faulty phases), load rejection, capacitor bank energization, and incorrect tap-up/down settings of transformers.

Long-Duration Voltage Variations

A long-lasting voltage abnormality (less than 0.9 per unit or greater than 1.1 per unit) that takes more than one minute is considered a long-duration voltage variation. This is because of load variations, switching operations, and poor system voltage regulation rather than fault conditions.

2.1.2. Waveform Distortion

Harmonics

Periodic waveforms in which sinusoidal components have frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency are referred to as harmonics. With the growth of nonlinear loads and the infiltration of renewable energy, harmonic distortion has become a ubiquitous challenge in contemporary power-grid systems. IEEE 519-2014 [43,44] recognized the limits of harmonic voltage and current distortion [40,45] at the PCC, with somewhat higher values and different conditions. The major causes of these disturbances are switch-mode power supplies, variable-frequency drives, LED lighting, arc furnaces, and battery chargers [40,42,46,47,48]. The measurement of this disturbance is followed by the following formula, which requires the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD):

where is the RMS voltage of harmonic order h and is the fundamental voltage. Another quantified method is for the Individual Harmonic Distortion (IHD), which is used as follows:

Beyond classical harmonics, recent studies highlight supraharmonics and common-mode EMI in the 9–150 kHz band of modern converter-rich systems, which can propagate through motor drives and distribution networks [40,43].

Interharmonics

Frequency components that are not integer multiples of the fundamental frequency have become increasingly common in modern power systems owing to the large-scale application of cycloconverters, arcing-type devices, induction motors operating at variable loads, and power electronic converters that utilize asynchronous switching. These Interharmonics may have a variety of negative effects, such as light flicker, thermal loading of capacitor banks, noise that interferes with control and protection signals, and interruptions in ripple control systems [49].

Notching

This phenomenon represents periodic voltage disturbances caused by the normal operation of power electronic devices during phase communication [50].

Noise

Noise is the voltage or current with spectral components below 200 kHz that are superimposed on the power waveform. Practically, this noise is typically divided into two categories: common mode noise, which propagates between the conductors and ground, and transverse mode noise, which influences the conductors of the line [9].

2.1.3. Voltage Fluctuations and Flicker

Voltage fluctuations refer to random changes in voltage, typically between 0.9 and 1.1. These changes in voltage often occur in the frequency range of 0.5–30 Hz, which can cause visible flicker [38,39]. The IEC 61000-3-7 and IEEE 1453-2015 [44] standards establish the planning and compatibility levels for flicker-severity assessments. Flicker severity was quantified using

- Short-term flicker severity (Pst): Measured over 10 min

- Long-term flicker severity (Plt): Measured over a 2 h period

Primary sources of voltage fluctuations include

- Arc furnaces

- Welding equipment

- Rolling mills

- Reciprocating pumps and compressors

- Wind turbines

- Large motor starting (repetitive)

2.1.4. Power System Imbalance

Voltage Unbalance

In the normal scenario of a three-phase voltage system, the magnitudes of the waves should be the same, with a 120° difference in their phases. However, an unbalanced voltage can occur because of abnormal grid conditions. Typical industry standards limit voltage unbalance to 2–3% [51]. This disturbance can be quantified using the following equation:

where V1 and V2 are the positive and negative sequence voltage components, respectively.

This phenomenon arises from several structural and operational factors in the power system. One key contributor is the uneven distribution of single-phase loads over the three phases, which can lead to current imbalance and voltage deviation. Moreover, open delta transformer configurations can often cause asymmetry in voltage magnitudes and related phase angles. Blown fuses in capacitors can also cause reactive power compensation disruption. In addition, asymmetric transformer impedances resulting from aging or manufacturing tolerances introduce unequal voltage drops under the load. Finally, non-transparent transmission lines contribute to mutual coupling, which distorts the problem throughout the entire network.

Current Unbalance

Similarly to voltage imbalance, current imbalance is a critical indicator of power-quality degradation. This term is often quantified as the Current Unbalance Factor (CUF), which is defined as [51]

where C1 and C2 are the positive and negative sequences of the current components, respectively.

This metric provides a percentage-based evaluation of asymmetry extension in the current waveform. A higher CUF indicates a greater deviation from the normal operation of the three-phase system, which can adversely affect various equipment, such as motors, transformers, and power electronic converters. Current and voltage imbalances can occur independently of each other. Even when the system voltage appears balanced, other factors such as unbalanced loading or nonlinear devices can cause issues with the CUF.

2.1.5. Power Frequency Variation

Power frequency deviations from the nominal 50 or 60 Hz beyond ±0.1 Hz indicate PQ issues. These arise from imbalances between generation and load [52]. Frequency stability encompasses steady-state variations and dynamic deviations caused by generator failures or load changes. Metrics such as the Rate of Change in Frequency (ROCOF), frequency nadir, and recovery time are used to assess performance and guide frequency control.

2.1.6. Transient Disturbances

Impulsive transients are sudden voltage or current changes with unidirectional polarity caused by lightning strikes, inductive switching, and electrostatics [53]. They have rapid rise times (1–10 µs), short durations (<50 µs), and high magnitudes (up to kV). Oscillatory transients affect both polarities and are categorized by frequency range: low (<5 kHz), medium (5–500 kHz), and high (500 kHz–5 MHz), which are related to switching and lightning events.

2.1.7. Power Factor and Reactive Power Issues

A low power factor has a high negative impact on both power quality and system efficiency [54]. These issues are caused by various factors, such as the current increment for the same active power transfer, high voltage drops across the lines, reduction in equipment capacity utilization, and increased system losses From a system-level perspective, improving PQ and efficiency in conversion chains complements broader sustainability goals identified by comparative life-cycle assessments of renewable electricity systems. For both sinusoidal (power factor, PF) and nonsinusoidal (displacement power factor, DPF) conditions, this occurrence can be quantified using the following equations:

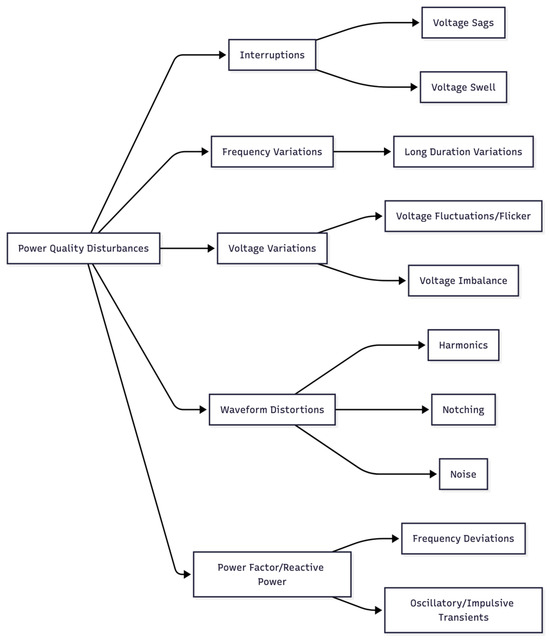

where PF is the power factor; true PF is the actual power of the system considering both the displacement and distortion components; P is the active power; Q is the reactive power; S is the apparent power; Vrms is the effective voltage; Irms is the effective current; DPF is the displacement power factor, which is related to the phase angle between voltage and current; and THDI is a measure of the amount of harmonic distortion present in the current waveform. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics, sources, and economic impacts of major power quality disturbances. Representative waveforms for these disturbances are shown in Figure 3, which contrasts the normal and distorted profiles.

Table 1.

Power quality disturbances.

Figure 3.

Representative waveforms of major power quality disturbances.

2.2. FACTS Devices, Classifications and Operating Principles

FACTS devices represent a sophisticated family of power electronic-based controllers, and their design is primarily intended to enhance the controllability, stability, and power transfer capabilities of AC transmission systems. This chapter focuses on various aspects of FACTS devices and their impact on increasing the functionality of the grid by mitigating disturbances [56].

where P is the active power transmission, Qs is the reactive power at the sending end, ∣Vs∣ and ∣Vr∣ are the voltage magnitudes at the sending and receiving ends, respectively, δs and δr are the voltage phase angles, and X is the line reactance.

FACTS devices provide dynamic control over the three main parameters.

- Line impedance (X)

- Voltage magnitude (∣V∣)

- Phase angle (δ)

This dynamic control is achieved by inserting reactive elements (such as inductors and capacitors) or direct voltage and current injection using power electronic converters that typically operate at high switching frequencies [42].

2.2.1. FACTS Device Classifications

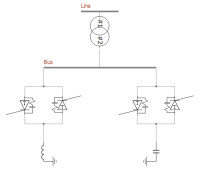

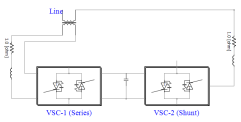

Series-Connected Controllers

These FACTS devices are connected in series with transmission lines through coupling transformers to control the impedance or voltage sources [11]. With this configuration, direct control of the power flow (i.e., relatively smaller ratings compared to shunt devices) is possible according to the following relationship:

where Xeffective is the effective line reactance after series compensation. Thyristor-controlled series reactors (TCSR) and thyristor-switched series reactors (TSSR) allow continuous adjustment of series inductive reactance using antiparallel thyristors, thereby providing dynamic power flow tuning [11]. A detailed comparative summary of FACTS categories, operating principles, and control objectives is provided in Appendix A.

2.2.2. Shunt-Connected FACTS Controllers

Shunt controllers [37] are connected in parallel with the system at specific points to have the most impact on the system (typical locations are at load buses or midpoints of long transmission lines), functioning as controllable current sources or variable impedances. It includes:

- Static Var Compensator (SVC): Comprised of thyristor-controlled reactors/capacitors, it provides fast voltage regulation and supports system stability under heavy or fluctuating loads [11].

- STATCOM (Static Synchronous Compensator): A voltage-source converter (VSC)-based shunt device offering rapid dynamic reactive compensation, harmonic filtering, flicker mitigation, and rapid support during faults [11]. The mathematical modeling details for these devices, including control equations and converter relationships, are summarized in Appendix A.1.

Practical PV-coupled deployments show that reduced-switch D-STATCOM topologies can maintain voltage and mitigate PQ issues while lowering switching burden, using modified SRF control in grid-tied operation [31].

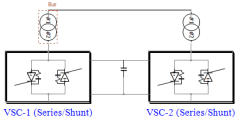

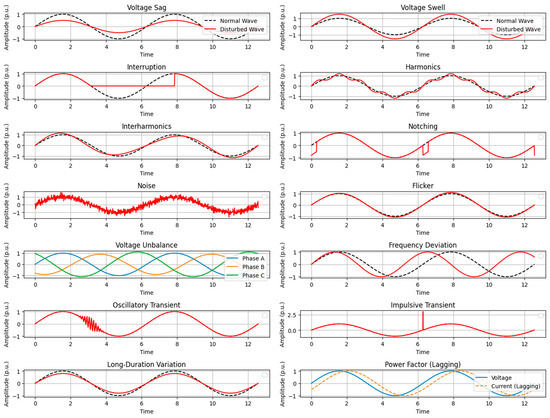

2.2.3. Combined Series-Shunt Controllers

Combined devices integrate both series and shunt controls for multimodal power optimization.

- Unified Power Flow Controller (UPFC): Simultaneously manages voltage magnitude, impedance, and phase angle using dual VSCs sharing a common DC link; UPFCs represent the most flexible FACTS technology for power flow control and quality enhancement [11].

- Interline Power Flow Controller (IPFC): Coordinates the power flow across multiple transmission lines using several VSCs connected to a shared DC link, optimizing grid utilization, and compensating multiple lines collectively [11].

2.2.4. Operating Principles and PQ Enhancement

FACTS devices enhance real-time voltage profiles and stability of the system by requiring active control of the magnitude of voltages, impedance, and phase angle, minimizing transmission losses, and facilitating power transfer up to thermal constraints [11], alleviating the problem of power quality disturbances, including voltage sags, flickers, and harmonics, and offering adaptive load flow management to overcome the challenges of integrating renewable energy.

To make its description more complete and thorough, Table 2 summarizes, characterizes, and classifies each type of FACTS device according to Table 2 and provides a schematic diagram as a visualization to better understand them. An example is the STATCOMs, which offers voltage support as well as harmonic/flicker reduction and is therefore crucial in renewable and load-dominated grids [11]. As detailed in Table 3, various FACTS devices differ broadly in terms of their response time and harmonic filtering capacity.

Table 2.

FACTS characteristics.

Table 3.

FACTS connection types and their construction features.

3. Fundamental of Artificial Intelligence in Power Systems

Although FACTS devices can help diminish the impact of numerous PQ disruptions owing to real-time reactive power and voltage control, their capability is sometimes limited by the static control logic. The response times to various PQ phenomena are often rapid and unpredictable, particularly in renewable-rich systems, necessitating adaptive responses. This makes the field ripe for AI to improve the detection, classification, and control of these disturbances, so FACTS devices can become proactive rather than reactive.

AI [31] is now revolutionizing power system operations, control, and analysis, thereby improving grid resilience and reliability. The given discussion presents the key AI technologies that can be used in the power domain and further elaborates on their implementations with reference to Harmonic Distortion mitigation in power-grid applications.

3.1. Core AI Technologies for Power System Applications

AI comprises computational methods that mimic human decision-making. Several branches of AI have proven to be highly effective in power system applications.

Machine Learning (ML) [28,72] is the heart of AI-driven power system solutions. It aids the system decision-making process to enhance its performance on data rather than only on pre-defined rules. ML algorithms analyze historical operational data for pattern recognition and relationship analysis [73,74,75,76]. The learning process is as follows:

Here, f maps the inputs x (e.g., system measurements) to the outputs (e.g., load forecasts or equipment status) with parameter optimization through iterative training. It is a key subset of ML with wide-ranging applications in power systems. An artificial neuron [77,78] computes

where xi is the inputs, w is the associate weight to each input, b is the bias, and is the activation function.

In modern Deep Learning applications, it is useful to recognize two main architectures (feedforward networks to address a static prediction problem and recurrent networks to process temporal sequences) to address such intricate power problems. Another extension, hierarchical features, provides a more accurate and effective solution by combining information at multiple levels.

Such an approach to uncertainty management suggests the use of degrees of truth, rather than binary logic. Fuzzy Logic [79] instead of using the conventional grid classification assigns values of membership, thus enabling a more flexible classification of operating conditions and appropriate distribution of control responsibility. The reduction in instability that accompanied the resulting increase in operational efficiency was significant.

where A represents the fuzzy test, x represents an element belonging to the universal set X, X is the domain where elements x are drawn from, and is the membership function.

Nature-inspired algorithms and swarm-type intelligence are subsets of optimization techniques [80] that have been implemented to optimize power system performance. These techniques follow a repetitive process to improve the population of candidate solutions using selection and variation mechanisms to achieve optimal results. They are particularly effective when implemented for optimization problems with nonconvex, discontinuous, and mixed-integer search spaces, where traditional methods tend to provide suboptimal results.

3.2. AI Applications Across the Power System Value Chain

Artificial intelligence technologies will be used in the entire lifecycle, both in the creation and use stages. An overview of the AI methods applied for power-quality enhancement is presented in Table 4.

- Deep Learning Renewable Forecasting: Deep learning-based models combine historical weather data, measured irradiance, and power generation measurements to predict wind and solar generation for better grid and dispatch planning [81].

- Predictive Maintenance: AI models based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) use sensor compositions, such as vibration, temperature, and acoustic sensor readings, to identify early signs of equipment and component deterioration, thus facilitating cost-efficient maintenance plans [82].

- Dynamic Line Rating (DLR): Models of neural networks combine ambient and operating variables to forecast real-time transmission limits; therefore, the utilization of the grid is optimized, and grid congestion is avoidable [83].

- Distribution Operations: Graph neural networks (GNNs) can model the network topology, spatial and temporal dependencies in load prediction, outage detection, and non-technical loss detection [84,85].

- Microgrid and Adaptive Control: Reinforcement learning algorithms find control policies to use energy management in uncertain conditions, thus maximizing the utilization of a grid and reducing costs [86].

Table 4.

AI applications in the power industry.

Table 4.

AI applications in the power industry.

| AI Application Area | AI Techniques Used | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Power Generation—Forecasting | Deep Learning (incorporating G: solar irradiance, T: temperature, C: cloud coverage) | Improved forecast accuracy, reduced reserve requirements, lower integration costs |

| Power Generation—Predictive Maintenance | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) | Early malfunction detection, reduced breakdowns, minimized unnecessary servicing |

| Transmission System—Dynamic Line Rating | AI models analyzing ambient temperature, wind speed, solar irradiation | Increased transmission capacity, reduced grid congestion, enhanced renewable integration |

| Distribution Management—Load Forecasting and Loss Detection | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Improved forecasting, better network reconfiguration, non-technical loss reduction |

| Microgrid Management—Optimal Control Policies | Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Optimized control policies, cost efficiency, reliability under uncertainty |

3.3. Advantages of AI in Power System Application

AI-driven approaches offer the following benefits.

- It has superior forecasting accuracy and reliability compared with traditional statistical methods.

- Adaptive modeling and control strategies continuously evolve as system patterns change, thereby reducing manual recalibration and operational overhead [81].

- Proactive fault detection, predictive disturbance mitigation, and dynamic optimization of conflicting objectives (quality, cost, and emissions) [87].

- Real-time optimization via gradient-based update rules:

3.4. Implementation Considerations and Challenges

The implementation of AI in power systems is affected by numerous obstacles that have been successfully addressed in previous studies. For uniformity, the specific PQ indices used for evaluating AI-based controllers are defined belowand in Appendix A.2.

- Data Quality and Integration: AI models require high-resolution, contextually relevant, and complete datasets. As mentioned in reference [88], the mitigation measures include advanced infrastructure for measurements, systematic data purification, and synthetic data generation.

- Model Interpretability: AI algorithms (many of which are opaque) compromise regulation and trust between operators. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques, including attention mechanisms, feature-importance analyses, and symbolic regression, are solutions to this issue and contribute to the understandability of the decision-making process.

- Computational Complexity and Latency: It centralizes AI solutions, high levels of latency and reliability issues can be expected. According to reference [89], edge AI platforms are used to compute on and around substations and control nodes, which is a significant improvement in the responsiveness and robustness of the system [90,91].

3.5. Regulatory and Organizational Challenges

In various scenarios, non-technical challenges pose greater barriers to AI adoption than technical ones. One major issue is that existing regulations are built around traditional rule-based control systems. AI-driven models that rely on probabilistic decision-making may not be easily accommodated in these frameworks. One approach to address this issue is to update policies and regulatory adjustments to ensure compliance and reliability of the data. Data fragmentation is a significant challenge. Various data-gathering organizations often manage their own isolated data sources. These entities may be reluctant to share critical information, and implementing AI across the entire system could be significantly complex and challenging. The lack of seamless data integration could hinder the full picture needed for optimal decision-making in AI models.

In addition to regulatory and data concerns, organizational resistance can slow AI adoption. Traditional operational frameworks have existed long enough for many power system professionals, who spend years working within them, and AI-driven decision-making system adoptability with new recruits is a challenging area. This requires new training, policy shifts, and changes in mindset. Resistance to change (because of a lack of trust in AI or concerns about job security) can cause an additional layer of difficulty in implementation [92].

3.6. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

With the growing adoption of AI in power system applications, various interceptional trends are expected to significantly influence future development. One of these is the hybrid AI methodology, which combines the strengths of different algorithms to improve the model’s performance and robustness. A notable example of this model is the use of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [93], which embeds physical power system equations directly into the neural network’s loss function. Utilizing this approach could enable the model to learn from both data and known system dynamics, while improving generalization and reducing the dependency on large datasets. The related function in the PINN framework is defined as

where represents the error based on the training data, encodes physical constraints derived from power system equations, and is a weighting factor that balances the influence of both terms. This combination allows AI models to maintain their alignment with physical laws while capturing complex data-driven patterns.

Another important learning method is federated learning [94], a decentralized training strategy that allows multiple local agents to collaboratively train a global model without any raw data sharing stage. This is useful for power systems, where data privacy and ownership are critical concerns across utilities and regions of interest. This model can be computed using the following formula:

where is the model trained on local dataset i, and N is the total number of participating agents. This approach provides users with sufficient assurance regarding data privacy, supports diverse operating conditions, and enables scalable model development without centralizing sensitive data.

In addition, digital twin technology [95] is evolving into a revolutionary concept in which AI-exploiting capabilities engage in real-time interactions with their physical counterparts. Such virtual copies can be used to perform large amounts of scenario testing, help in perfecting systems, and predict faults before they occur without risking real machinery. The mutual communication between physical and virtual systems results in the constant enhancement of both, making digital twins a critical instrument for smart grid advancement.

Finally, quantum computing [96] provides a futuristic method for addressing computational dilemmas in power system analysis. Quantum computing has the potential to solve optimization problems exponentially, which could enable a new level of capabilities in power grid management, planning, and control, particularly in situations in which classical algorithms cannot readily find a solution.

By expanding and developing these methods, AI’s role of AI will expand from supporting isolated system functions to orchestrating comprehensive interactions over different aspects of power systems (generation, distribution, and consumption). Table 5 provides a synthesized overview of state-of-the-art methods, including neural networks, support vector machines, fuzzy logic, deep reinforcement learning, and optimization metaheuristics, and their documented impacts on power quality disturbances, such as harmonics, voltage sags/swells, flicker, and imbalance.

Table 5.

AI techniques for power quality improvements.

4. AI Applications for Power Quality Enhancement, Monitoring, and Control

The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) into power quality (PQ) technologies has evolved the management practices in electrical distribution systems. Different power system issues, such as voltage sags, power factor correction, and real-time monitoring, have seen significant improvements owing to the utilization of AI-driven solutions. This section thoroughly explores this interconnected application, which offers the strength of AI methods to advance power quality management using detailed mathematical frameworks, comparative analysis, and sophisticated optimization strategies.

4.1. Advanced AI Technologies

4.1.1. Neural Network Architecture

Neural networks can be implemented in various PQ applications, where they leverage specialized structures that are suited to different scenarios.

Feedforward Neural Networks (FFNNs) are among the most fundamental architectures in deep learning, consisting of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [101]. In these networks, information travels in a single direction without feedback loops, rendering them suitable for tasks in which temporal dependencies are negligible. The output of each neuron is determined as follows.

where represents the input features, denotes the weight connecting input I to neuron j, is the bias term, and is the activation function.

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are a type of recurrent neural network (RNNs) with structures that specifically address long-term dependency issues. They are particularly useful for forecasting voltage drops and time disruptions in power networks [97]. LSTMs have a long-term cell state that develops over time and is regulated by forget, input, and output gates. The update rule for the cell state is provided by

where ct is the cell state at time, ft is the forget gate’s output, it is the input gate’s output, and is the candidate cell state.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are commonly used to extract spatial features from waveform (or image-based) data. CNNs are especially useful for disturbance classification in power quality applications for identifying patterns in voltage and current signals [98]. The convolution operation of each filter is expressed as

where is the output of the k-th convolutional filter, represents filter weights, and denotes input values within the filter window. The activation function is applied element-wise to the resulting sum.

For event recognition, hybrid wavelet–CNN pipelines have achieved accurate decomposition and classification of composite PQ disturbances, supporting near-real-time monitoring [102].

4.1.2. Fuzzy Logic Systems

Fuzzy logic controllers [11,79] are widely used for PQ applications owing to their ability to handle uncertainty and imprecise information. These controllers provide robust decision-making capabilities by mimicking human decision-making behavior and linguistic rules rather than relying solely on mathematical models. The fuzzy control process can be divided into four stages. The first is fuzzification, which involves transforming the numerical values of inputs into fuzzy sets with specific membership functions. Second, the input conditions were interpreted by applying a set of predetermined rules and fuzzy logic operators in the rule evaluation step. The aggregation step then integrates the outputs of each applicable rule into a single fuzzy response. Finally, defuzzification converts the combined fuzzy output to a crisp, implementable control signal that can be used within the system.

In PQ, especially for FACTS devices, fuzzy logic is instrumental in dynamically adjusting the control parameters. This method typically processes inputs, such as errors and changes in errors, to determine an appropriate control action. The mathematical representation of this procedure is as follows.

where , , are the membership functions representing the linguistic variables for the system inputs and outputs, e is the error, is the change in error, and is the appropriate control action.

These rules help optimize the performance of PQ devices, such as DVRs and DSTATCOMS, by ensuring real-time adaptive control.

4.1.3. Evolutionary and Swarm Intelligence Algorithms

Evolutionary computing and swarm intelligence algorithms have been widely applied to optimize and enhance the efficiency of PQ in control systems. By emulating biological processes and natural behaviors, these methods attempt to solve complex optimization problems efficiently.

PSO [98] is a population-based optimization technique inspired by the behaviors of birds and fish. This method attempts to refine the potential solutions using the particle velocity updates and positions according to the following mathematical equations:

Fuzzy logic controllers provide robust performance in power-quality applications by managing uncertainty and imprecision [103]. The basic fuzzy inference process involves the following:

where w is the inertia weight, c1 and c2 are acceleration coefficients, r1 and r2 are random values ensuring stochastic behavior, pbesti represents the personal best position of each particle, and gbest is the best global position found by the swarm.

This method has been widely used in PQ applications, such as voltage sag detection, harmonic compensation, and optimal placement of FACTS devices.

The genetic Algorithm (GA) provides robust optimization using the principles of natural selection, crossover, and mutation. By evolving candidate solutions to achieve optimal system performance, they can be used in power system quality control for various scenarios. Proportional–integral (PI) tuning in FACTS devices is a common application of this method. The goal of this optimization was to minimize the following fitness function:

where e(t) is the error signal between the desired and the actual value, u(t) is the control effort that is applied to the system, w1 and w2 are weighting accuracy for implementing the balance among accuracy and control energy.

With the optimization of control parameters, GA ensures improvement in transient response, reduces overshoot, and enhances stability in PQ devices. Combining this method with other AI techniques enables intelligent and adaptive power quality management, which significantly improves grid reliability [15].

4.2. AI Techniques for Voltage Sag Prediction and Mitigation

Voltage sag is a crucial issue in power systems that must be addressed. Its prediction and mitigation are vital for power quality management, where AI-driven techniques provide advanced predictive analytics and control mechanisms. Using these methods would enhance grid stability and reliability by enabling proactive responses to voltage disturbances. The representative test systems and simulation platforms referenced in this review are summarized below.

Predictive Analytics for Voltage Sag

In modern voltage sag prediction frameworks, multiple AI modules collaborate to perform specialized tasks, such as feature extraction, classification, and time-series forecasting [32].

For comprehensive voltage signal analysis, wavelet transform techniques are widely utilized [100] for feature extraction and selection; by breaking them down into multi-resolution components, they can effectively capture transient events. The mathematical formula is as follows:

where a is the scale parameter for the frequency resolution control, b is the translation parameter shifting the function in time, and is the mother wavelet function.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) with Gaussian kernel functions are commonly used for power quality disturbance classification, as they provide high accuracy and robustness [104]. The kernel function is as follows.

The decision function is given by

where xi, xj are feature vectors representing different dataset points, is the squared Euclidean distance between the feature vectors, is a hyperparameter that controls the influence of a single training, is the LaGrange multiplier, is the class label for each training sample, is the kernel function output, and is the bias term that helps to define the decision boundary in the feature space.

The ability to identify and detect temporal patterns that are reflective in historical voltage measurements is a chief benefit of using Long Short-term Memory (LSTM) networks in the prediction of phenomena involving voltages [105]. Mathematically, the temporal change in the internal state of the cell in the LSTM unit is formalized as follows:

In this formulation:

where ht represents the latent state of the network at the specific time step t, defining the temporal discovered features; Wc is a matrix containing information on successions between two successive states; xt is the value of the input data at step t, and here is the voltage signal being considered; and ot indicates the opening of the output result, which decides the number of contributions of the changed cell condition to the concealer representation.

4.3. Advanced FACTS Devices with AI Control

FACTS devices equipped with AI-based controllers are capable of real-time adaptive solutions for mitigating voltage sags using adjustable reactive power [106]. AI can enhance the precision and efficiency of these controllers, ensuring a rapid response to any grid disturbances of varying severity.

4.3.1. Static Synchronous Compensator (STATCOM) with AI Control

The operation of AI integration to STATCOM [19] can be formulated as

where VPCC voltage at the Point of Common Coupling (PCC), C is the capacitance of the DC-link capacitor, iL is the current load drawn from power system, iSTATCOM is currently injected by the STATCOM to compensate for voltage sags and maintain the grid stability, Imag is the magnitude of the compensating current, is adjusted by the AI model, wt is the grid regular frequency term, is phase angle that is optimized by a neural network controller. At distribution level, ANN-trained D-STATCOM controllers have been shown to enhance voltage regulation, power factor, and harmonic mitigation under time-varying loads [107].

4.3.2. Dynamic Voltage Restorer (DVR) with AI-Enhanced Sliding Mode Control

DVRs utilize advanced Sliding Mode Control (SMC) with AI-optimized procedures to compensate for voltage sags [108,109]. The sliding surfaces for the direct and quadrature-axis error compensation are defined by the following mathematical equations:

where sd and sq are sliding surface variables in the direct (d) and quadrature (q) reference frames, respectively; ed and eq are voltage errors in the d-q frame; and kd and kq are control parameters tuned by the AI-based optimizer.

In the AI-enhanced novel reaching law, the rapid convergence of the sliding mode control is as follows:

where is the adaptation coefficient controlling the rate of system response, exponent regulating the nonlinear behavior of the reaching law, is the sing function ensuring the correct switching behavior.

4.3.3. Unified Power Quality Conditioner (UPQC) with AI Algorithm

The UPQC is a multifunctional power quality device that uses both series and parallel compensators for the simultaneous mitigation of voltage sags, harmonics, and power imbalances. AI-based controllers can optimize their performance using a series Active Power Filter by adjusting the reference compensation voltage [19,110]:

where is the reference compensation voltage injected by the series APF, is the desired load voltage after compensation, is the measured distorted source voltage before compensation.

4.4. AI-Driven Dynamic Power Factor Correction and Reactive Power Compensation

AI-based power factor correction [106,111] plays a major role in enhancing power quality with dynamic reactive power compensation. Neural network-driven approaches offer precise real-time adjustments to ensure system efficiency and stability improvement.

4.4.1. Neural Network-Controlled Shunt Active Power Filters

Shunt active power filters (SAPFs) equipped with neural network control are one of the integrations of AI and FACTS. In this system, harmonic currents compensate to improve the power factor and mitigate distortions. The fundamental compensation principle is expressed as

where represents the load current is the desired source current.

The neural network can determine the desired source current based on the fundamental power calculations:

By continuously adjusting the compensation current, the neural network controls the P and Q, which are the active and reactive powers, respectively, to maintain the unity power factor of the grid.

4.4.2. Adaptive Reactive Power Compensation Algorithms

For advanced reactive power compensation techniques [104,112] that incorporate instantaneous power theory enhanced using neural-network-based optimization, the active and reactive power can be mathematically quantified as follows:

where p represents the instantaneous active power, q represents the instantaneous reactive power, and are the transformed voltage components, and are the transformed current components.

The neural network plays a vital role in optimizing the extraction of oscillating components (q and q) to enable selective harmonic compensation while preserving the fundamental reactive power component required for unity power factor correction.

The reference current required for compensation is computed as

Utilizing this approach enables precise reactive power compensation while ensuring a unity power factor and minimizing harmonic distortion.

4.4.3. Distribution Static Compensators with Intelligent Control

A D-STATCOM with the aid of AI-based control strategies could demonstrate enhanced dynamic performance for power factor correction and reactive power compensation. AI-driven approaches can adapt to system conditions in real time, thereby improving response time and stability [107]. The compensating reactive power in the D-STATCOM system is given by

where is the compensating reactive power, is the system voltage, is the compensatory current, is the compensating phase angle.

Based on this equation, the D-STATCOM can rapidly adjust its angle to maintain the power factor close to unity to ensure efficient power delivery and reduced losses.

The Adaptive Neural Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) integrates fuzzy logic and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for D-STATCOM improvement control. With this hybrid approach, the adaptability, learning capability, and robustness in handling nonlinear system behavior can be improved. The related equation can be quantified as follows:

where y is the ANFIS output, is the rule firing strength, is the output of individual fuzzy rules, and n is the total number of fuzzy rules.

Faster repose and better transient performance compared to traditional controllers can be considered as one of the benefits of this AI-driven controller.

4.5. Real-Time Power Quality Monitoring and Distributed Control

Rather than AI, the integration of other technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and edge computing, has revolutionized real-time power quality monitoring and control, allowing the system to lead to a more efficient and intelligent decision-making form of operation [100].

4.5.1. AI-Enhanced Disturbance Classification

Multistage AI structures have gained popularity in recent power quality monitoring systems as a means of realizing highly accurate classification of disturbances [32]. Our process starts with signal pre-processing, where we use techniques such as wavelet packet decomposition to extract the most critical features of the voltage waveforms. The next step is the feature selection phase, which uses a metric such as the Information Gain Ratio (IGR) to determine the most pertinent attributes to be used in the classification. Finally, the classification stage uses ensemble learning, in which the outputs of multiple models are integrated to improve the overall accuracy and robustness in detecting different disturbances of power quality.

The mathematical formulation for the IGR in features is as follows:

where IG(A) represents the information gain for attribute A and SplitInfo(A) measures the entropy of attribute A.

4.5.2. Disturbance Edge Computing Architecture

The utilization of edge computing, localized AI processing, and the distribution of computational tasks across multiple nodes enables [15]. This technology is important because it runs a lightweight neural network.

where is the output at the ith edge node, is the activation function, and with represent the weight matrix and input vector, respectively.

4.5.3. IOT-Integrated Monitoring System

In the framework of IoT-based monitoring [98], a top-down data processing strategy is used to guarantee efficient and scalable system operation. The sensor layer at the bottom measures high-resolution voltage and current waveforms in real time. This data is then sent to the edge processing layer, where the model performs a localized analysis with minimal latency. In addition, the fog computing layer integrates the data of several edge nodes and runs regional-level analytics to support intermediate decision-making. Finally, the cloud computing layer performs system-wide analysis and enables deeper insights and analysis, long-term trends, and global optimization of the entire grid infrastructure.

4.6. Optimization Strategies for Power Quality Systems

4.6.1. Multi-Objective Optimization for FACTS Device Placement

The suitable placement of FACTS devices employs multi-objective optimization to balance conflicting objectives [79]:

The common objective functions include:

- f1(x) is the voltage sag mitigation

- f2(x) is the installation and operational costs

- f3(x) is the power system losses

4.6.2. Metaheuristic Algorithms for Controller Parameter Optimization

Metaheuristic optimization techniques fine-tune the controller parameters in PQ systems for enhanced performance and reliability. Metaheuristics are also effective at wide-area damping controller tuning for FACTS; a Grey Wolf Optimizer demonstrated robust channel selection and controller design for oscillation damping. Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) is an approach in which the teacher and student are used for the TLBD algorithm to model the learning process [7]:

where represents the ith candidate solution, is the best-performing solution, is the population mean, is a randomly generated number, and is the teaching factor.

Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) algorithm which is inspired by the social hierarchy of gray wolves, the GWO algorithm upgrades its position using:

where is the current position of a gray wolf in the research space, is the position of the prey, or the current best solution, represents the distance vector between the prey and current wolf, and are the vector coefficient.

4.6.3. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Control

Deep Learning (DRL) could enable the adaptive control that allows an agent to learn optimal control strategies through interactions with its environment [87]. This process involves selecting actions based on the states, receiving rewards, and adjusting actions by considering the experience of the agent. The State-Action-Reward-State-Action (SARSA) [113] algorithm updates the Q values each time through the following equation:

where is the current estimate of the Q-value for state is the learning rate, is the reward received after acting, is the discount factor, and are the next state and action.

The utilization of this algorithm helps the controller adaptively improve and take actions based on real-time outcomes. For more advanced scenarios, Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [99] are used to approximate the Q-values using a deep neural network, particularly when the state or action space has a large number of numbers to be handled with traditional methods:

where contains various parameters (e.g., weights and biases) of the neural network and is the optimal Q-value that network aims to approximate.

This method uses experience (the technique called experience replay), which stores and randomly samples past interactions to improve learning stability and efficiency.

For the model effectiveness evaluation [102], multiple performance indicators were employed across three core functionalities. Some key performance indicators of voltage sag compensation systems are numerous. The response time is the time lag between the detection of a sag and the commencement of the mitigating action. To determine the quality of the waveform after compensation, the Voltage Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) was measured to indicate the capability of the system to provide a less distorted waveform. The voltage recovery profile measures how well the system can recover the voltage to the nominal value after a disturbance occurs. In addition, energy usage is provided during the compensation assessment, which is relevant to systems that use energy-storing elements.

In the power factor correction (PFC) context, performance is determined by the magnitude of power factor correction achieved, with a view to ensuring that the power factor is as close to unity as practical. The current THD measures the quality of the present waveform following compensation, and the reactive power compensation accuracy measures the accuracy with which this system delivers the required reactive power. The transient response characteristics describe how the system reacts to sudden changes in the load or voltage. In addition, monitoring system features are important and are evaluated based on detection accuracy, classification precision, false positive/negative rates, and the computational efficiency of algorithms used to recognize and classify power quality disturbances. A consolidated mapping of AI algorithms to specific FACTS control objectives is presented in Table 5.

4.7. Real-World Applications of AI Technology in Power Quality Management

Neural networks, reinforcement learning, fuzzy logic, and metaheuristic optimization are artificial intelligence technologies that have gone beyond laboratory and theoretical experiments to produce real-world, substantive power system applications. Their performance capabilities in terms of scale-based data analysis, dynamic behavior under scenario changes, and addressing complex control issues make them especially localized to modern electrical grids that must deal with issues arising from the advent of renewable sources and load variability.

Advanced utilities have implemented artificial neural networks (ANNs) for the detection and classification of harmonics in sophisticated monitoring systems. As an example, a utility in Europe has deployed ANN-based predictors that take in all waveforms captured by smart sensors to predict harmonic distortions and, thus, allow a proactive correction of shunt compensators to prevent overheating and failure of equipment [97].

Auto-voltage controls and autonomous microgrids Pilot projects on reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms have been tested to offer autonomous energy management and voltage control. These systems have higher levels of reliability and efficiency than fixed, formal controls, which are made possible by learning the best battery dispatch schedules and inverter settings under changing conditions of renewable generation and load.

To optimize the deployment and tuning of FACTS apparatuses, such as STATCOMs and SVCs, several operators of transmission systems have used Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms. Their search control systems are more efficient than manual tuning processes that minimize the loss of power and enhance stability in the voltage profile, and there are examples of their implementation in the North American and Asian market [101].

Fuzzy logic controllers have also been widely used in industrial factories that require high power regulation and reduction in flicker. Fuzzy systems with the ability to cater to sensor errors and nonlinear load behavior provide better compensator operation that is smooth and minimizes maintenance.

High-resolution monitoring and predictive maintenance of the grid with real-time AI and IoT grid sensors allow the incorporation of AI and IoT devices to reduce downtime and prolong asset life. Owing to the use of AI, a digital twin platform mimics real segments of the grid to analyze scenarios that boost operational planning and resilience [96]. Domain-specific applications, such as rail traction systems, report that AI-driven UPQC control improves voltage quality and power factor under highly dynamic loading profiles.

4.8. Comparative Case Studies

This subsection presents brief and to-the-point comparisons of AI-based controllers with conventional PI/PID controllers in typical FACTS applications, providing metrics such as response time, voltage-recovery responses, overall harmonic distortion, and control-point accuracy, evolved in identical operating-point research with an experimental or HIL study [45,46,114].

4.8.1. Flicker Mitigation (STATCOM)

Many experimental and peer-reviewed studies have shown that neuro-fuzzy/adaptive AI-controlled STATCOM attains better var-tracking, reduced overshoot, and additional power-quality indicators compared to suitably tuned PI/PID settings when comparing the performance over identical laboratory conditions, including conditions where the reactive power demand can be unbalanced or time varying. In distribution networks and wind-integrated systems, the coordinated control by STATCOM significantly enhances the voltage regulation and disruptive resilience as measured by quantifiable indices of power quality, which illustrate the out-of-depthless of the learning-based control schemes compared to the conventional baselines when the system is disturbed. These performance improvements become most visible when the device nonlinearities and cross-couplings are dominant, and anti-windup interactions together with saturation and protection boundaries are established in both AI-based and conventional implementations when there are significant events of major transient nature [18,95].

4.8.2. DVR of Voltage-Sag Compensation

According to both the experiment and HIL, the AI-controlled DVRs occupy the reported speeds of sags occurring during the experimental settings along with significantly lower overshoot and injected voltage THD relative to previously noted classical PI/PID representatives under the same disturbance libraries and instrumentation. Proper sag/swell operation and stable converter performance were also verified using well-established hardware testbeds, providing a strong empirical base for comparative claims regarding the recoveryy time, steady-state error, and harmonic distortion under equal operating conditions. Even in the case of safe deployment, which depends on the reliability of fault detection, phase-locked synchronization, and restriction of injected voltage or current with high rigidity constraints to meet thermal and protection criteria, regardless of the control paradigm used [93,94]. Comparative evaluations of DVR control strategies confirm measurable improvements in sag compensation dynamics and steady-state PQ indices across multiple controller designs.

4.8.3. New PQ Mitigation as a Combine Approach Using UPCQ

AI-coordinated UPQC controllers, including ANFIS/ANN hybrids, improve simultaneous harmonic rejection and voltage regulation, as well as DC-link stability and angularly couple series-shunt configuration of the microgrid, compared to decoupled PI/PID configurations in microgrid and feeder-level experimental systems. Relative studies systematically catalog the elimination of current and voltage THD and enhanced voltage-deviation qualities during compound disturbances, and workflow simulation-to-hardware validation demonstrates a consistent enhancement of multipurpose performance distributions compared to classical results. The benefits observed depend on the fidelity of the measurement, delay of communication, confidence-cognizant gating, and dangerous fallback protocols to independent loops, which reduce the risk in conditions of poor elaborate telemetry or high-speed topological changes in real-world deployments [89,92]. Table 6 consolidates improvements achieved by AI-controlled FACTS devices under the stated objective functions. As summarized in Figure 4, the comparison highlights AI-driven FACTS devices across case studies and baselines.

Table 6.

Improvements achieved by AI-controlled FACTS devices.

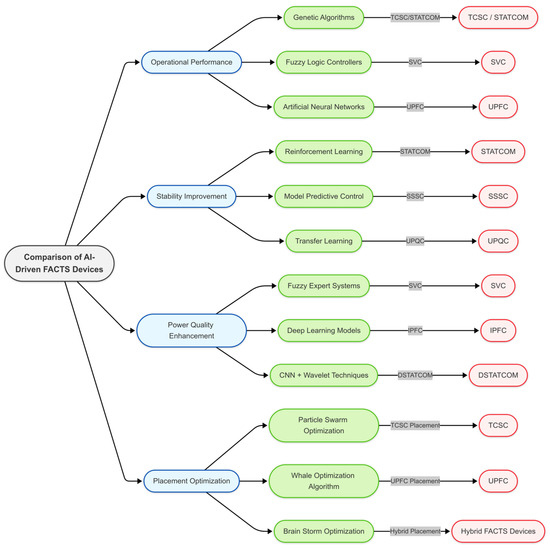

Figure 4.

Comparison of AI-driven FACTS devices.

5. Challenges, Future Research Directions, and Implications of AI-FACTS Integration

5.1. AI-FACTS Implication Challenges

Although significant progress has been made, there are considerable technical and practical challenges associated with the combination of artificial intelligence and FACTS devices in power quality management. The dependency on high-quality heterogeneous datasets is an important issue. The lack of sufficient data, noisy data, and prejudiced data undermine model generalization, causing failure under unobserved operating conditions. In addition, the high computational latency and resource demands also limit real-time applications, especially the demands in high-changing grid patterns with response times of less than a millisecond. The second salient challenge is model drift, in which the machine learning models gradually deteriorate in accuracy because of changes in the system, such as changes in the topology of the system, upgrading hardware, or alterations in the load profile. To reduce this drift, periodic retraining, adaptive algorithms, or the adoption of physics-based priors as part of hybrid models are required to maintain stability. In addition, the problem of AI model interpretability continues to interfere with operator confidence and regulatory adherence, highlighting the need to incorporate XAI systems into FACTS decision-making solutions.

5.2. Model Drift and Lifecycle Management

The operational constraints of AI-oriented FACTS controllers result from the mismatch between real-world conditions and the conditions used in training during seasonal load changes, changing mixes of DER, sensor recalibration or aging, and network reconfiguration. All of these individually create a shift in the distribution and affect the controller performance poorly if the conditions are not mitigated. To converter feeders, disturbance patterns and impedances change with topology and dispatch, thus requiring topology-dependent lifecycle reviews instead of offline tuning once [115,116,117].

5.2.1. Monitoring and Detection

Monitors and data should continually test feature-distribution drift by simple statistical procedures, such as the population stability index and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, and also through monitoring of residuals or errors between the outcomes of the model and data to detect consistent offered deviation at previously specified levels. Concurrently, Point of quality key performance indicators, such as THD, voltage-recovery time, overshoot of sags or swells, and flicker indices Pst and Plt, need to be plotted on control charts to identify performance degradation when operating in non-stationary mode [27].

5.2.2. Triggers and Policies

The drift tests, residual, and PQ key performance indicators (KPIs) should have quantitative thresholds igniting the alarms and launching the shadow mode of the candidate models on live data and rolling back to the known-good baseline to maintain the safety marginss. Vital data volumes and holdout situations as needed during revalidation must be defined in maintenance windows to ensure that revisions do not cause time constraints and that rare yet significant conditions are included in testing [17].

5.2.3. Failover and Risky Releases

Shadow deployment and A/B testing should be followed by model updates based on a proven baseline, and confidence-conscious gating should be implemented in such a manner that actuation returns to a safe deterministic policy if the confidence or data quality are found to be lower than the preset thresholds. There should be a deterministic contingency of classical controllers, such as PI/PID schemes with anti-windup and hard limits, which should be accessible at all times and guarantee voltage, current, and thermal limits during failover and recovery [17].

5.2.4. Edge-Cloud Orchestration

Algorithms that require a time-varying PQ control loop must run on the edge to achieve sub-cycles to tens to milliseconds latency, and consolidation, retraining, and validation must be performed in the cloud using signed artifacts and batched deployment to edge nodes. This division maintains local control when amputating communications and distributes the compute location with control importance within the distribution systems with FACTS and DERs.

5.2.5. Auditability, Diplomacy and Governance

Both versions of the model must be small but tracked by the provenance of training data, validation measures, and date of deployment, controller activities, and overrides are logged to assist in investigating incidents and regulatory audits. Explanations of the main actuation decisions made by operators are user-friendly and expedite root-cause analysis when the performance is poor in the field.

5.2.6. Retraining Strategy and Validation

Training must be planned proactively based on drift indicators and operation schedules using new data windows and holdout testing that resembles rare but crucial PQ actions in practice. Candidate models should be as effective as the baselines with respect to response time, voltage recovery quality, THD, and flicker, showing performance that meets or exceeds the performance of the baselines given the same disturbance libraries used in previous validation.

5.3. Future Research Directions

To cope with these issues, the further research agenda has several prospective orientations.

- Physics-constrained hybrid AI Hybrid models use data-driven learning models with analytical models to combine resilience to distributional change with reduced dependence on large labeled corpora in the application of PQ control mechanisms in complex grid architectures that use converters in many locations [68,118].

- PINNs incorporate power-system-level differential equations (including constraints on the network, networks, and modeling (and constraining) device dynamics) directly into the objective of the training task with the critical goals of ensuring feasibility and fast convergence [118].

- Federated and privacy-preserving learning models support multi-utility and multi-region model training without necessarily involving the exchange of raw data, preserving confidentiality, and meeting regulatory requirements while capturing the heterogeneity of operational regimes and enhancing the generalizability of AI-FACTS controllers [94].

- Federated architectures use cross-domain aggregation to support heterogeneity in sites, sensor arrays, and DER portfolios; using weighted client updates to reduce non-iid data distributions and concept drift, and this approach helps to increase the stability of globally deployed models that serve to reduce THD mitigation, sag/swell compensation, and properly flicker reduction [94].

- Digital twins and real-time simulations imply that temporally synchronized, high-fidelity, virtual copies of substations, feeders, and FACTS assets are created, such that controllers can be stress-tested in high-fidelity, physically sensitive, in silico, and alternative disturbances can be stress-tested in functions of a rarity database before any controllers can be deployed [12].

- Twin-guided adaptive control is an adaptive control technique that uses the closed-loop feedback of a pair of digital twins to tune artificial intelligence controllers to transiently provide a low-latency response and enhance voltage recovery statistics to mitigate production risk and alleviate response latency and voltage recovery requirements [39].

- Multi-agent reinforcement Learning The (MARL) determines the local juxtaposition goals of specific devices, including STATCOMs, DVRs, UPQCs, and DERs, and rallies the system-wide stability results through objective reinforcement and reward shaping actions in constrained communication among multiple agents [88].

- Safety-conscious grid control reinforcement learning, an explicit grid control problem, is combined with fallback and supervisory layers to ensure that the actions of the agents are within the voltage, current, and thermal parameters, and the responses with respect to the disturbance-rich environment meet the stringent and time-critical PQ feedback requirements [113].