Abstract

We propose a novel target detection algorithm that addresses the issues of ignoring shape attributes in regression loss and the inability of the high-parameter PAFPN to jointly perceive scale–space–task information. Specifically, we construct a Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (LPAFPN) to reduce model parameters by shuffling and fusing features across channels. To further enhance its perception ability, we augment LPAFPN with a scale–space–task joint-perception enhancement module, terming the resulting network ALPAFPN, which can adaptively process joint information of scale, space, and task. Finally, we introduce a shape-scale bounding box regression loss method that focuses on the target’s intrinsic attributes to optimize the regression measurement, thereby boosting the detection accuracy. Experimental results show that the proposed algorithm outperforms state-of-the-art algorithms in terms of F1 score, Precision, and Mean Average Precision (mAP) on the PASCAL VOC and VisDrone2019-DET datasets.

1. Introduction

As one of the downstream tasks of computer vision, object detection aims to localize and recognize objects of interest from images or videos. It is now widely used in various fields, such as autonomous driving [1], robotic vision [2], and video surveillance [3].

Traditional object detection methods [4] typically employ manually designed sliding windows and feature extractors to predict object categories and locations. However, these methods may fail to retain accuracy and robustness with diverse objects and complex backgrounds [5]. Moreover, in real-world applications, factors like sensor quality and environmental conditions directly influence the accuracy and reliability of the acquired data, thereby significantly impacting the performance of detection models evaluated on the dataset [6].

In comparison with traditional methods, deep learning-based object detection methods demonstrate superior robustness by extracting deeper semantic features. Existing deep learning-based object detection methods [7] can be broadly categorized into two types: Transformer-based [8] models and CNN-based models [9]. Both paradigms effectively support parallel computation, thereby overcoming the inherent limitations of recurrent neural network (RNN) [10] models in parallel processing. In most cases, Transformer-based methods demonstrate superior performance in capturing global contextual information [11,12], whereas CNN-based object detection approaches exhibit lower computational complexity, rendering them more suitable for real-time applications with stringent latency requirements. CNN-based models are primarily divided into two-stage and one-stage paradigms. The former is typically represented by algorithms such as Faster R-CNN [13] and Mask R-CNN [14], while the latter includes frameworks like SSD [15] and RetinaNet [16]. In these classical approaches, there often exists spatial misalignment in predictions between classification and localization tasks. To overcome these shortcomings, the TOOD algorithm [17] designs a Task-Aligned Head to enhance the interaction of two tasks, thereby optimizing the spatial distribution of features learned for object detection. TOOD and YOLOv8 [18] adopt FPN [19] and PAFPN [20] as their feature fusion networks, respectively. Compared with FPN, PAFPN incorporates a bottom–up path augmentation to enhance multiscale feature fusion capabilities. However, PAFPN struggles to synergistically integrate scale, spatial, and task-specific information, while its reliance on standard convolutions may increase parametric complexity.

To address the limitations of PAFPN and the neglect of target shape attributes in existing regression losses, we propose a novel object detection algorithm via Shape-IoU Loss and Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network featuring scale–space–task collaborative enhancement. The approach not only designs a Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network with scale–space–task collaborative enhancement, but also introduces a shape-scale bounding box regression loss method, thereby improving detection accuracy while reducing model parameters. The principal contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We construct Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (LPAFPN), which integrates and shuffles information from standard convolutions and depth-wise separable convolutions to reduce Parameter Count.

- (2)

- We design Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network with scale–space–task collaborative enhancement (ALPAFPN), which enhances the perceptual capabilities of the model by synergistically processing features from distinct feature layers, spatial locations, and task-specific channels.

- (3)

- We introduce a shape-scale bounding box regression loss method that incorporates target shape attributes to optimize the regression loss function, thereby improving the detection accuracy of the model.

- (4)

- We conduct extensive experiments on the Pascal VOC dataset and VisDrone2019-DET dataset, and the experimental results reveal that the F1 score, Precision, and Mean Average Precision of LSCA are superior to those of the state-of-the-art methods.

2. Related Work

2.1. CNN-Based Methods

Existing CNN-based methods can be broadly classified into two main types: two-stage methods and one-stage methods [21].

The two-stage object detection approaches extract features of interest from these bounding boxes to detect objects after generating candidate bounding boxes. Faster R-CNN enhances detection speed by introducing the Region Proposal Network (RPN) [22]. Dynamic R-CNN [23] proposes a dynamic IoU threshold adjustment mechanism that adapts to the demand for high-quality samples during training by progressively optimizing the threshold. Sparse R-CNN [24] employs a fixed number of learnable sparse proposal boxes to perform classification and localization through a dynamic instance interactive head.

One-stage object detection methods directly predict the location and category of objects from images without generating candidate boxes. SSD introduces multireference and multiresolution detection techniques, thereby enhancing detection accuracy. YOLOv7 [25] achieves significant performance improvements by employing strategies such as dynamic label assignment and model structure reparameterization. YOLOv8 reduces the prediction of redundant bounding boxes by improving the anchor-free detection head, which achieves a balance between accuracy and speed in object detection tasks. YOLOv9 [26] designs the GELAN architecture to reduce computational complexity by optimizing model parameters. YOLOv10 [27] employs an NMS-free dual-label assignment strategy during training that maintains computational efficiency while capturing key detection features.

2.2. Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network

The Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network integrates multiscale features through top–down and bottom–up path aggregation. However, the PAFPN exhibits a relatively weaker capability in collaboratively processing scale, space, and task information. Additionally, the extensive number of input and output channels in the 3 × 3 convolutional layers of this architecture may lead to a substantial increase in the number of parameters. In response to the aforementioned issues, LSCA has developed a Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network with scale–space–task collaborative enhancement. This innovation not only reduces the Parameter Count of the model but also significantly improves its perceptual capabilities related to scale, space, and task information.

2.3. Loss Function

IoU Loss [28] describes the degree of match between the prediction box and the GT box. However, it encounters limitations when the IoU is zero, as it fails to differentiate the positional relationship between the two boxes due to the vanishing gradient problem. To mitigate this issue, Generalized IoU (GIoU) Loss [29] introduces the minimum enclosing box, which alleviates the vanishing gradient problem to some extent when IoU equals zero. Center IoU (CIoU) Loss [30] enhances the accuracy of object detection by incorporating constraints related to the normalized distance between the centroid of the prediction box and the GT box. In comparison to the aforementioned loss functions, the Scale-Invariant IoU (SIoU) Loss [31] provides a more precise measurement of the matching degree between the predicted and ground truth boxes by integrating angle-aware geometric constraints. While these loss functions primarily focus on the geometric relationship between the predicted and ground truth boxes, they fail to explicitly account for the actual shape of the target, thus neglecting the influence of inherent attributes of the target on bounding box regression. The Shape-IoU bounding box regression loss method is introduced to solve the above problems. This method takes into account the impact of geometric attributes such as the shape of the target on the positioning accuracy, so as to optimize the regression loss metric.

3. Method

3.1. Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network

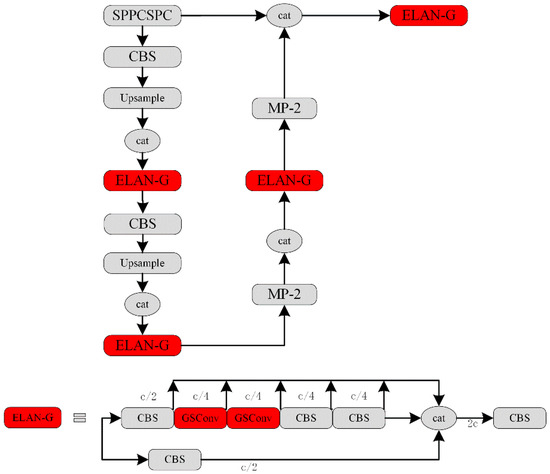

The Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network (PAFPN) partially enhances the expression ability of the model by integrating multiscale features through top–down and bottom–up paths. The 3 × 3 convolution in PAFPN maximally preserves hidden connections between channels, but this increases the number of parameters in the model. To address this problem, GSConv is introduced into the proposed model to construct LPAFPN, as shown in Figure 1 Through the shuffle operation, GSConv fuses the feature information generated by the 1 × 1 standard convolution and the depth-wise separable convolution, which reduces the Parameter Count while preserving the detection accuracy.

Figure 1.

Network Structure of LPAFPN.

Let and denote the input and output feature maps of GSConv, respectively. As can be seen from Equation (1), the feature maps are obtained by applying standard convolution, depth-wise separable convolution, and concatenation operations to ,

where is a 1 × 1 convolution with a stride of 1, and is a 5 × 5 depth-wise separable convolution using a stride of 1.

Let , , , , , , then can be formalized as Equation (2):

The number of model parameters is reduced without sacrificing detection accuracy, since the depth-wise separable convolution reduces model complexity, while the shuffle operation fuses cross-channel feature information in GSConv.

3.2. Scale–Space–Task Co-Enhanced Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network

GSConv serves as a basic building block in LPAFPN, where the shuffle operation is introduced to integrate the features extracted by the depth-wise separable convolution and the standard convolution. To solve the problem that LPAFPN may neglect the diversity of feature scales, spatial locations, and channel tasks, we construct ALPAFPN by introducing the scale–space–task attention mechanism (SSTA), which jointly processes scale, space and task information through cascading scale-aware, spatial-aware, and task-aware attention mechanisms. The scale-aware attention mechanism focuses on the scale size of the target, facilitating the learning of the feature importance from different layers, and enhancing the features of the layer of interest. The spatial-aware attention mechanism captures the spatial location information within the same layer and across different layers to extract more discriminative spatial features. The task-aware attention mechanism is designed to adaptively process feature data on different channels, which enables the achievement of objectives in multiple detection tasks.

3.2.1. Scale-Aware Attention Mechanism

Set . Let and be the input and output feature maps of the scale-aware attention mechanism, respectively. As illustrated in Equations (3) and (4), , which is obtained by resizing , is further processed via pooling, convolution, and activation operations to acquire the weight vector . If , , , then can be attained from Equations (5) and (6):

where .

3.2.2. Spatial-Aware Attention Mechanism

Let and be the input and output feature maps of the spatial-aware attention mechanism, respectively. Set , . Suppose that the weight matrix is divided into blocks according to Equation (7). Then can be acquired from Equation (8). If , , then can be obtained by the dot product of and , as demonstrated by Equation (9). Let , , then can be attained from Equation (10). Assume that and are divided into blocks as derived from Equations (11) and (12), then can be acquired from Equation (13).

3.2.3. Task-Aware Attention Mechanism

Let and be the input and output feature maps of the task-aware attention mechanism, respectively. Set . Then and are vectorized to generate and , respectively. If , , , , , then can be derived from Equation (14). Let , then the vectorized output feature map can be formalized as Equation (15).

SSTA facilitates the cooperative processing of scale, space and task information, thereby enhancing the perceptual capabilities of the model and improving its detection performance.

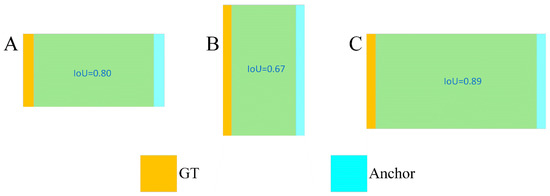

3.3. Shape-IoU Loss

The bounding box regression losses represented by CIoU, DIoU, and SIoU, which are integrated into the optimizer, play an important role in the localization task of object detection. However, the losses ignore the influence of the intrinsic properties such as the shape and scale of the target, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

GT frames and prediction frames.

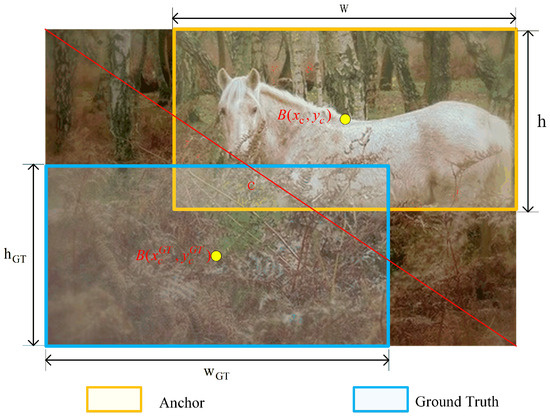

In Figure 2, for A and B, all bounding boxes maintain the same scale, while the ground truth boxes between A and B have different shapes. In A and C, the bounding boxes have the same shape, but the GT boxes differ in scale. The data presented in A and B illustrate that the deviation along the short side has a larger impact on the IoU values in comparison to the long side. From A and C, it can be observed that at smaller scales, the influence on the IoU values is more sensitive than at larger scales. To address this shortcoming, we introduce the shape-scale loss for bounding box regression (Shape-IoU Loss) that focuses on the intrinsic properties of the target, as shown in Figure 3. Shape-IoU Loss is computed by utilizing the shape and scale of the bounding boxes, which optimizes the metric of the regression loss to improve detection accuracy.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of Shape-IoU Loss.

Let scale represent the scale factor. Suppose that and are the width and height of the ground truth box, respectively. Then and can be computed by Equations (16) and (17):

where and indicate the shape of the GT box, and scale denotes the target size.

Let and denote the predicted box and the target box, respectively. Assume that w and h denote the width and height of the prediction box, respectively. Suppose that and are the coordinates of the center points in the predicted box and the labeled box, respectively. Let us assume that c is the diagonal length of the smallest rectangle enclosing both the prediction box and the GT box. Then the formulas for Shape-IoU Loss are as follows.

The regression accuracy is improved, since Shape-IoU Loss not only includes the geometric relationship between the target box and the predicted box, but also integrates the intrinsic properties including the shape and scale of the target.

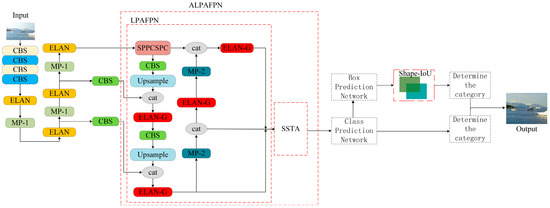

3.4. Overall Architecture of LSCA

The overview of LSCA is illustrated in Figure 4. First, after the input images are fed into the backbone to extract features, the LPAFPN module is constructed to integrate feature information across different channels and reduce the number of parameters in the model. Second, SSTA is designed to improve the representational capacity of the model by coordinating the processing of scale, space, and task information. Then, Shape-IoU Loss is introduced to focus on the shape and scale of the bounding box itself, thereby improving detection accuracy. Finally, we achieve the outcomes that are regions estimated to be objects from the detection head.

Figure 4.

Overall architecture of LSCA.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Dataset and Evaluation Metrics

We evaluated the proposed algorithm’s performance on the Pascal VOC dataset and VisDrone2019-DET dataset. To comprehensively validate the efficacy of the LSCA model, we not only calculated F1 score, Average Precision (AP), Mean Average Precision (mAP), Precision (P), Recall (R) and Parameter Count, but also plotted the P-R curves and F1 bar charts.

4.2. Experimental Platform and Training Details

The proposed model is trained and tested under Ubuntu18.04 OS with Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8255C CPU @ 2.50 GHz and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU. Pytorch 1.9.0 is employed as a deep learning framework.

In the training stage, the detection models are trained using SGD as the optimizer, with the epoch set to 100 and the batch size set to 8. The momentum factor and weight decay factor are set to 0.937 and 0.0005, respectively. The initial learning rate is set to 0.01, and the learning rate is dynamically adjusted via cosine annealing strategy. Additionally, L in Section 3.2 is set to 3.

4.3. Quantitative Analysis

4.3.1. Quantitative Analysis on Pascal VOC Dataset

In this section, Table 1 shows the comparison of Mean Average Precision (mAP) and Average Precision (AP) for each category of nine algorithms. It is noted that LSCA reaches the best AP in 13 classes, obtains suboptimal AP in 3 classes, and achieves 84.12% mAP, which is 10.04%, 9.09%, 10.92%, 11.71%, 8.93%, 1.14%, 6.61%, and 1.05% higher than those of ATSS [32], TOOD, Faster-RCNN, Dynamic Head [33], NAS-FCOS [34], YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and YOLOv9-c, respectively.

Table 1.

AP and mAP of the nine algorithms.

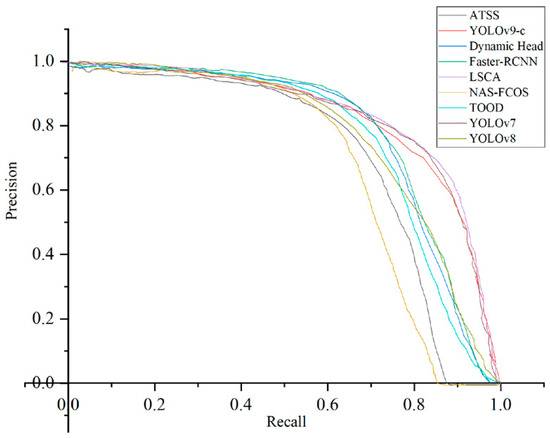

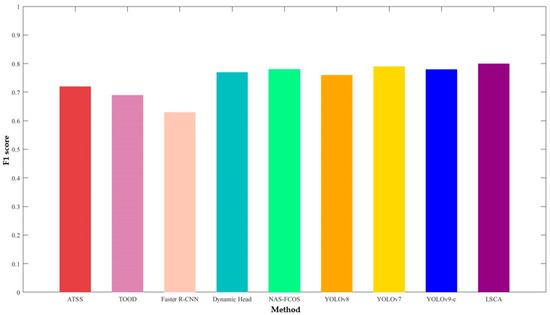

As shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, we performed P-R curve analysis and F1 bar chart analysis to evaluate the performance of LSCA.

Figure 5.

Comparison of P-R curves of the nine algorithms on the PASCAL VOC dataset.

Figure 6.

Comparison of F1 bar chart of the nine algorithms on the PASCAL VOC dataset.

As is well known, the closer the P-R curve is to the top right corner, the better the detection performance. As can be seen from Figure 5, the P-R curve of the proposed algorithm is closest to the upper right corner, suggesting that LSCA is superior to the compared algorithms.

Moreover, it is well known that the higher the location of the F1 bar chart, the better the overall performance. Following Figure 6, the F1 bar chart of LSCA is the highest, which shows that our presented method outperforms other state-of-the-art algorithms.

As shown in Table 2, the proposed LSCA achieves optimal results in terms of mAP, F1 score, and Precision when compared with twelve state-of-the-art object detection models, including ATSS, TOOD, Faster R-CNN, Dynamic Head, NAS-FCOS, YOLOv8, YOLOv7, YOLOv9-c, Lite YOLO-ID [35], YOLO-RACE [36], MLCA [37], and EfficientDet-D0 [38].

Table 2.

Comparison of objective evaluation indexes of the nine algorithms on the PASCAL VOC dataset.

4.3.2. Quantitative Analysis on VisDrone2019-DET Dataset

Table 3 lists the results of six evaluation indicators for eleven algorithms. It can be seen from Table 3 that the Mean Average Precision, F1 score, Precision, and Recall of the LSCA algorithm all perform better than those of the other ten mainstream comparative algorithms.

Table 3.

Comparison of objective evaluation indexes of the nine algorithms on VisDrone2019-DET dataset.

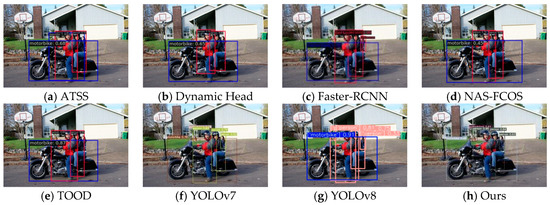

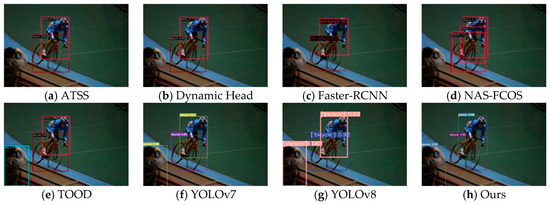

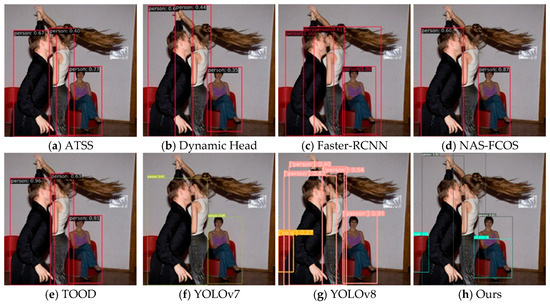

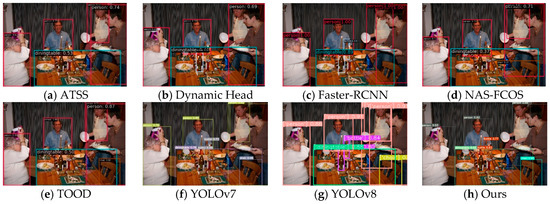

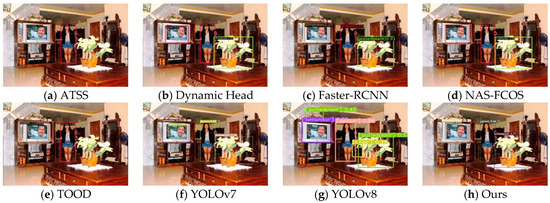

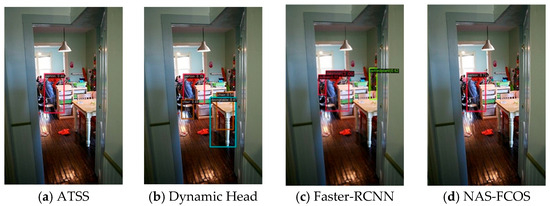

4.4. Qualitative Analysis

To qualitatively analyze the detection performance of the proposed algorithm, we selected six images from the Pascal VOC 2007 test set to compare with the algorithms of ATSS, Dynamic Head, Faster-RCNN, NAS-FCOS, TOOD, YOLOv7, and YOLOv8. Figure 7 shows the images to be detected, and Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 present the comparison of detection results from the eight algorithms.

Figure 7.

These tested samples are labeled as 1 to 6, from left to right.

Figure 8.

The detected results of image 1.

Figure 9.

The detected results of image 2.

Figure 10.

The detected results of sample 3.

Figure 11.

The detected results of image 4.

Figure 12.

The detected results of sample 5.

Figure 13.

The detected results of image 6.

Sample 1 contains three person labels, one motorbike label, and one potted plant label, and the scene in this sample is complex, with occlusion and incomplete targets. The experimental results are shown in Figure 8, which reveals that ATSS and YOLOv8 exhibit issues with duplicate detections for the motorbike and person targets, respectively. ATSS, Faster-RCNN, and YOLOv8 fail to detect the potted plant target. Dynamic Head, NAS-FCOS, and TOOD fail in detecting the person and potted plant targets. Only YOLOv7 and LSCA have no problems with duplicate detection and missed detection, and therefore yield the best detection performance.

The second sample to be detected consists of two persons and one bicycle. The scene of this sample is characterized by darkness and insufficient lighting, and the detection results are shown in Figure 9. It can be seen from Figure 9 that ATSS, Dynamic Head, and Faster-RCNN fail to detect the person target. TOOD incorrectly detects the person target. Even worse, NAS-FCOS exhibits issues of missed detection, false detection, and duplicate detection. It is worth noting that YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and the LSCA successfully avoid missed detection, false detection, and duplicate detection, while LSCA demonstrates more accurate localization of the person target.

The targets of test sample 3 are composed of three persons and two chairs. Overlap and occlusion occur in this sample, as shown in Figure 10. The results indicate that ATSS, Dynamic Head, Faster-RCNN and TOOD fail to detect the chair targets, while NAS-FCOS and YOLOv7 miss the detection of both chair and person targets. Additionally, YOLOv8 not only misses the detection of the two chair targets, but also suffers from duplicate detection. It is noted that LSCA achieves optimal detection performance without any issues of missed detection, duplicate detection, or false detection.

The labels of the fourth tested image include four persons, two bottles, one chair, and one dining table. The sample scenario is complex, with a large number of targets. The results are shown in Figure 11, from which we can observe that ATSS, Faster-RCNN, NAS-FCOS and TOOD fail to detect bottle or chair targets while Dynamic Head exhibits missed detection of person, bottle, and chair targets. In addition, YOLOv7 and YOLOv8 suffer from inaccurate localization and duplicate detection issues, respectively. In a word, LSCA reaches the best detection performance without the problems of duplicate detection, missed detection, and poor localization accuracy.

The fifth image to be detected consists of 2 person labels, 1 TV monitor label, and 1 potted plant label. The scene of this sample is characterized by a complex background and the presence of nested objects. Figure 12 shows the results which demonstrate that ATSS, Faster R-CNN, and NAS-FCOS are unable to detect the person targets while ATSS and Dynamic Head fail to detect the potted plant target and the TV monitor target, respectively. Meanwhile, TOOD exhibits missed detection and false detection for the potted plant and person targets, correspondingly. YOLOv8 not only misses the detection of the person target, but also has generated false positives for the potted plant and chair targets. Additionally, YOLOv7 exhibits inaccurate localization of the potted plant target. It is noteworthy that LSCA avoids false detection, missed detection, and poor localization accuracy, demonstrating the highest detection accuracy.

Test image 6 contains 2 person labels, 2 chair labels, and 1 dining table label, and the scene exhibits significant variations in the target scale with regard to small targets. By examining the detection results in Figure 13, we can see that Dynamic Head has the situation of missing detection of person targets, while YOLOv7 and YOLOv8 do not detect both chair and person targets, and ATSS, NAS-FCOS and TOOD struggle with missed detection of person targets, chair targets and dining table targets. Moreover, Faster-RCNN not only misses detecting the person targets and dining table targets, but also falsely identifies a potted plant target. In contrast, only LSCA achieves the best detection performance, committing neither missed nor false detection.

4.5. Ablation Study

To evaluate the effectiveness of GSConv, SSTA, and Shape-IoU, extensive ablation experiments are performed, and the results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation experiment results of the LSCA algorithm.

Table 4 illustrates the results of the ablation experiments. A comparison between rows 5 and 8 in Table 4 suggests that the absence of Shape-IoU results in a 0.68% decrease in mAP, which indicates that Shape-IoU improves the accuracy of bounding box regression loss by focusing on the intrinsic properties of targets. As can be seen from the sixth and eighth rows in Table 4, the mAP decreases by 0.95% due to the absence of SSTA, which enables adaptive processing of joint information related to scale, space, and task to enhance the model’s perception capabilities. From the detection results in row 7 and row 8 of Table 4, it can be seen that the mAP improves by 0.09% while the parameters increase by 1.5 M without GSConv. This shows that GSConv effectively shuffles and fuses the outputs from standard convolution and depth-wise separable convolution, reducing Parameter Count while almost maintaining model accuracy. Furthermore, comparing row 1 and row 8 in Table 4 reveals that the proposed algorithm achieves both reduced complexity and improved detection accuracy. Specifically, the integration of GSConv, SSTA, and Shape-IoU can bring a 1.14% improvement in mAP, and reduce parameters by 2.5 M.

As we can see from rows 1, 3, and 4 in Table 4, the introduction of SSTA and Shape-IoU into the baseline model can bring an mAP improvement of 1.08% and 0.76%, respectively. Rows 1 to 3 show that the incorporation of GSConv and SSTA reduces the Parameter Count by 1.7 M and 0.7 M, respectively. This demonstrates that SSTA contributes most to the improvement in network performance, while GSConv contributes to the greatest reduction in Parameter Count.

The results of the ablation study on GSConv are reported in Table 5. As illustrated in Table 5, GSConv achieves suboptimal results in both mAP and the number of parameters among the four convolution methods. Although GSConv exhibits an mAP value that is 0.04% lower than that of Conv, it has 1.7 M fewer parameters than Conv. Conversely, while the Parameter Count of GSConv is 0.2 M higher than that of PConv, its mAP is 0.76% higher than that of PConv. Compared with the other three convolution methods, GSConv reduces the Parameter Count while maintaining nearly the same detection accuracy. This validates the effectiveness of GSConv.

Table 5.

Ablation experimental results of GSConv.

The effectiveness of the proposed feature fusion network can be verified through the ablation experimental results with different numbers of SSTA modules in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, when the number of SSTA modules is greater than one, the performance of the proposed feature fusion network surpasses that of the baseline network. Notably, when two SSTA modules are employed, not only does the network achieve the optimal mAP, but its Parameter Count is also 0.73 M fewer than that of the baseline network. Therefore, it validates the effectiveness of the proposed feature fusion method.

Table 6.

Ablation experimental results of SSTA.

In the experiment, the SSTA module is integrated into several popular object detectors to evaluate its generalization capability. As shown in Table 7, the introduction of the SSTA module improves the mAP of the baseline detector by 0.92%, 0.93%, 1.08%, 0.92%, and 0.84% for Faster R-CNN, ATSS, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, and NAS-FCOS, respectively. This consistent improvement across diverse architectures confirms the module’s strong generalization performance.

Table 7.

Ablation study of the SSTA module on different algorithms.

The performance of the detection algorithm varies with different scale factors of the Shape-IoU loss function. As shown in Table 8, a scale factor of 1.2 yields the highest mAP value. Consequently, the proposed algorithm sets the scale factor at 1.2.

Table 8.

The selection of scale factors.

Table 9 presents the ablation experiment results of Shape-IoU. As shown in Table 9, DIoU, Wise-IoU, SIoU, and Shape-IoU achieve mAP improvements of 0.24%, 0.36%, 0.67%, and 0.76%, respectively, compared with CIoU. This indicates that Shape-IoU performs the best among the five methods, validating the effectiveness of the Shape-IoU method.

Table 9.

Ablation experiment results of Shape-IoU.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we present a novel one-stage object detection algorithm via Shape-IoU and a Lightweight Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network featuring scale–space–task collaborative enhancement. Specifically, we construct an LPAFPN that uniformly exchanges local feature information across different channels to fully integrate the information output from both standard convolution and depth-wise separable convolution, reducing the number of model parameters. Furthermore, ALPAFPN is designed to enhance the network’s representation capability by simultaneously perceiving scale information across feature layers, spatial information at different locations, and task information among different output channels. Moreover, the detection performance of the model is improved by introducing Shape-IoU Loss, which focuses on the shape and scale of targets to optimize the regression loss function. The experimental results demonstrate that, when compared with the state-of-the-art algorithms used on the Pascal VOC dataset and VisDrone2019-DET dataset, our approach achieves superior performance in terms of F1 score, Precision, and Mean Average Precision.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W. and Y.C.; Methodology, G.W., X.Z. and D.D.; Software, J.W.; Validation, G.W. and J.W.; Formal analysis, G.W., X.Z. and D.D.; Investigation, X.Z.; Resources, G.W., X.Z., J.W. and Y.C.; Data curation, G.W., D.D. and Y.C.; Writing—original draft, G.W., X.Z. and D.D.; Writing—review & editing, G.W.; Visualization, X.Z.; Supervision, G.W. and J.W.; Funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 11804209, in part by the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province under Grant 202403021221010, in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province under Grant 20230302121101, Grant 201901D111031 and Grant 201901D211173, and in part by the University Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shanxi Province under Grant 2020L0051 and Grant 2019L0064.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yuan, Q.; Chen, X.; Liu, P.; Wang, H. A review of 3D object detection based on autonomous driving. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 1757–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Tang, M.; Gu, C. An improved YOLOv5-based method for robotic vision detection of grain caking in silos. J. Meas. Eng. 2025, 13, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, S.M.; Kazemi, M.; Moallem, P.; Safayani, M. Video anomaly detection based on attention and efficient spatio-temporal feature extraction. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 6825–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Peng, B.; Gao, M.; Hao, H.; Li, X.; Mou, H. Object Detection Based on CNN and Vision-Transformer: A Survey. IET Comput. Vis. 2025, 19, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, C.; Henriques, R.; Castelli, M. Deep learning-based object detection algorithms in medical imaging: Systematic review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, M. Operational Environment Impact on Sensor Capabilities in Special Purpose Unmanned Ground Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2024 21st International Conference on Mechatronics-Mechatronika (ME), Brno, Czech Republic, 4–6 December 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Y.; Li, B.; Sun, H.; Chen, M.; Zhuang, W.; Zhang, Y. Engineering applications of artificial intelligence a knowledge-guided reinforcement learning method for lateral path tracking. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 139, 109588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, A.; Mehak, G.; Hussain, N.; Gelbukh, A.; Sidorov, G. Detection of Depression Severity in Social Media Text Using Transformer-Based Models. Information 2025, 16, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Rong, X.; Sun, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Lu, J. Adaptive Convolution for CNN-based Speech Enhancement Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, T.; Hashmi, K.A.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Object Detection with Transformers: A Review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.04670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yue, J.; Fu, J.; Wu, S. River floating object detection with transformer model in real time. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.-Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Wei, S. Automatic Ship Detection Based on RetinaNet Using Multi-Resolution Gaofen-3 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Scott, M.R.; Huang, W. TOOD: Task-aligned One-stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; An, P.; Hu, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, T. UAV-YOLOv8: A Small-Object-Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOv8 for UAV Aerial Photography Scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23, 7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, L. Intelligent analysis method of dam material gradation for asphalt-core rock-fill dam based on enhanced Cascade Mask R-CNN and GCNet. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 56, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandarias, J.M.; Garcia-Cerezo, A.J.; Gómez-de-Gabriel, J.M. CNN-Based Methods for Object Recognition with High-Resolution Tactile Sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 6872–6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Yan, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Yuille, A. Weakly Supervised Region Proposal Network and Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chang, H.; Ma, B.; Wang, N.; Chen, X. Dynamic R-CNN: Towards High Quality Object Detection via Dynamic Training. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Kong, T.; Xu, C.; Zhan, W.; Tomizuka, M.; Li, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. Sparse R-CNN: End-to-End Object Detection with Learnable Proposals. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fang, J.; Song, X.; Guan, C.; Yin, J.; Dai, Y.; Yang, R. Iou Loss for 2d/3d Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 16–19 September 2019; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection Over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.; Liu, W.; Ye, R.; Hu, Q.; Zuo, W. Enhancing Geometric Factors in Model Learning and Inference for Object Detection and Instance Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 8, 8574–8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU Loss: More Powerful Learning for Bounding Box Regression. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chi, C.; Yao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Li, S.Z. Bridging the Gap Between Anchor-Based and Anchor-Free Detection via Adaptive Training Sample Selection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–18 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, B.; Chen, D.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Dynamic Head: Unifying Object Detection Heads with Attentions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.08322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gao, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, P.; Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y. NAS-FCOS: Fast Neural Architecture Search for Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1906.04423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, X.; Song, Y. LiteYOLO-ID: A Lightweight Object Detection Network for Insulator Defect Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.-H.; Park, S.-W.; Park, J.; Jung, S.-H.; Sim, C.-B. YOLO-RACE: Reassembly and convolutional block attention for enhanced dense object detection. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2025, 28, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Lu, R.; Shen, S.; Xu, T.; Lang, X.; Ren, Z. Mixed local channel attention for object detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).