Abstract

The use of conventional fuels for heat, energy, or motion production is largely determined by the concentration of water in the fuel. Therefore, the knowledge of the moisture content is of particular importance for combustion efficiency. Specifically, the presence of water in fuels can cause corrosion, and during preheating the water vapor can cause extinguishing of the flame, while at low temperatures it can cause blockage of the network by ice that can be formed. In general, the presence of water can contribute to the development of organic and inorganic substrates that may contribute to fuel turbidity, a fact that is addressed by the addition of chemical additives. In the present work, the possibility of removing moisture from heating diesel fuel through the properties of ionic and non-ionic organic polymers, namely polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyethylene oxide (PEO), was studied. The experimental data obtained by the addition of the polymers to the diesel showed that the fuel’s physicochemical properties were within the suitability limits, while the moisture content was decreased from 62 mg/kg to 50 mg/kg and 53 mg/kg, respectively, for PVA and PEO polymers. A mathematical expression of adsorption was used to simulate the experimental findings. In addition, the sulfur content was decreased from 941 mg/kg to 937 mg/kg when PVA was used. The methodology proposed for improving the physicochemical properties of heating diesel through organic polymers can optimize its combustion behavior to be more environmentally friendly.

1. Introduction

In recent years, engineers and researchers have been willing to develop fuels and engines in order to decrease the harmful exhaust emissions with significant environmental impact [1,2]. It is well known that the presence of humidity in diesel has a negative effect on the combustion process and general storage of the fuel, resulting in lower efficiency; greater environmental pollution, since the conditions do not ensure complete combustion; and higher maintenance costs for fuel storage tanks. Water cannot be completely removed from diesel fuels. It can enter the fuel during production processes or from the storage and transportation network, and the presence of water promotes the growth of fungi and bacteria, which can lead to blockage of fuel filters. Water and sediment content in the fuel may also cause rust and damage to fuel system components. Water and sediment contribute to the blockage of filters in distribution networks and can create problems due to corrosion and wear of the spraying system. Diesel fuel with a high-water content can lead to the formation of iron oxide particles inside the fuel tank [3,4]. This causes internal rusting of the fuel lines, pumps, and injectors when the engine is not in use. This problem has been reported in engines that have not been run for a while and have developed rust problems. The formation of fuel emulsions with water can give the fuel a turbid appearance, causing problems in its marketing. This issue can be addressed by the use of appropriate additives. The use of additives is expensive and time-consuming [5].

Diesel fuel is any liquid fuel specifically designed for use in a diesel engine, a type of internal combustion engine in which fuel ignition takes place without a spark as a result of compression of the inlet air and then injection of fuel. Therefore, diesel fuel needs good compression ignition characteristics. The most common type of diesel fuel is a specific fractional distillate of petroleum fuel oil, but alternatives that are not derived from petroleum, such as biodiesel, biomass-to-liquid (BTL) or gas-to-liquid (GTL) diesel, are increasingly being developed and adopted. To distinguish these types, petroleum-derived diesel is usually called petrodiesel [3]. Diesel is a high-volume product of oil refineries [4]. Diesel fuel is very similar to heating diesel, which is used in central heating. Central heating is a type of building heating installation. It involves producing heat for space heating and/or hot water using a central system installed in a building, apartment building, or building complex. This central system consists of a set of interconnected devices and instruments, namely the boiler, the burner, the circulator, the fuel tank, the safety devices, the pipes, the chimney, and the radiators. The energy produced is transferred to the various spaces through a heating medium (water, steam, or air) while the distribution is achieved through a network of pipes or air ducts, or even a combination of both. In practice, the differences between the two types of fuel are found in the higher cetane number of the engine (50–55 versus ~40 of the heating), in the viscosity (the engine is thinner), and in the sulfur content. From an environmental point of view, the use of heating oil is particularly burdensome since the sulfur content ranges from about 1000 ppm, while in diesel fuel it is only 10 ppm. Marine fuel oil has about 10,000 ppm. Water in fuel can damage a fuel injection pump. Some diesel fuel filters also trap water. Water contamination in diesel fuel can lead to freezing in the fuel tank. The freezing water that saturates the fuel may sometimes clog the fuel injector pump [6]. Once the water inside the fuel tank has started to freeze, gelling is more likely to occur. When the fuel is gelled, it is not effective until the temperature is raised and the fuel returns to a liquid state. For the process of removing water from fuels, the following techniques are used: (a) the technique of heating the oil storage tanks with a long residence time in the fuel tanks, (b) the use of chemical demulsifiers, and (c) the method of electrostatic precipitation. The cost study for each technique depends on its use in each fuel, the volume of the fuel, etc. The technique proposed with polymers is simpler, easier, and has a very low cost [7,8,9,10].

The methodology proposed in this work is based on the use of hydrophilic polymers for the removal of moisture [11,12], while the reduction in moisture and sulfur in diesel fuel using polymers with polar groups is examined for the first time. Specifically, the use of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyethylene oxide (PEO) polymers is recommended. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVOH, PVA, or PVAl) is a water-soluble synthetic polymer with a molecular weight of 85,000–125,000 g/mol. It has the idealized formula [CH2CH(OH)]n. It is used in papermaking, textile warp sizing, as a thickener and emulsion stabilizer in polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) adhesive formulations, in a variety of coatings, and in 3D printing [9,10,11]. It is a white powder and odorless. It is commonly supplied as beads or as solutions in water. Without an externally added crosslinking agent, PVA solution can be gelled through repeated freezing-thawing, yielding highly strong, ultrapure, biocompatible hydrogels, which have been used for a variety of applications such as vascular stents, cartilages, contact lenses, etc. [13,14,15]. Polyethylene oxide (PEO) is an intrinsically uncharged (nonionic) polymer with an MW typically up to 106 g/mol, although a very high molecular weight PEO of 100,000 g/mol was measured and confirmed by SEC-MALLS [16]. It can be obtained by the catalytic polymerization of ethylene oxide, resulting in a relatively linear structure. Such a high-MW PEO is, however, susceptible to degradation caused by the presence of certain metal ions such as Fe3+ and Cr3+. Such a nonionic polymer is expected to flocculate silica suspension by interparticle bridging, more notably through hydrogen bonding since no electrostatic attraction can come from an uncharged polymer chain. PEO chain adsorption can occur between ether oxygen and OH groups presented at the particle or oxide surface (silanol or aluminol groups). Optimum hydroxylation is hence desirable on the oxide surface [16,17,18].

In this specific methodology, a polymer quantity of 0.1 g was used, which was added to a fuel volume of 20 mL (so that the amount of additive does not exceed 5 kg per ton of fuel, which is the limit for the use of additives in fuels), and the moisture value in the fuel was determined. The final diesel is a new fuel with physicochemical properties within the limits, while the moisture and sulfur values have been significantly reduced so that it has greater combustion efficiency and more environmentally friendly behavior. The use of low-cost and easy-to-produce polar polymers in the moisture removal process is being applied for the first time, and has no industrial application to date. The use of polymers for sulfur removal is presented in the international literature for the first time and there are no relevant studies on this subject. Optimization of these techniques could lead to an industrial application, offering a new perspective to the hydrocarbon industry.

2. Experimental Study

2.1. Experimental Procedure

Two different types of polymers, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyethylene oxide (PEO) (Figure 1), were used in the present study. The physicochemical properties of diesel heating fuel are given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical formulas of polymers (a) PVA and (b) PEO.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of diesel heating fuel.

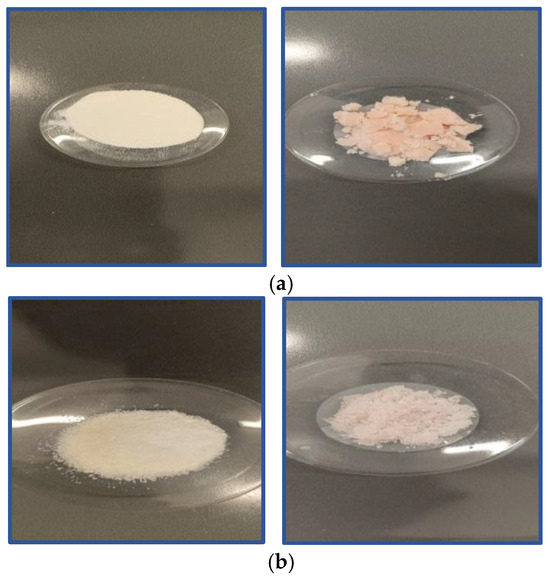

An experimental procedure for introducing the polymer into diesel fuel was carried out with the aim of observing its behavior. Specifically, a small amount of the polymer (0.1–0.3 g) was introduced into a quantity (20–60 mL) of fuel and then filtered. The two forms of the polymer—i.e., its dry, crystalline structure and its state after entering the fuel—are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Polymers as laboratory materials before and after treatment with diesel: (a) PVA and (b) PEO.

In brief the experimental procedure was as follows: A polymer mass of 0.1–0.3 g was selected because it allows the use of the polymer as an additive (the volume of additives must not exceed 5 kg per ton). The choice of the measurement volume of 20–60 mL for the fuel was made due to the Karl Fisher moisture analyzer (Titroline A-plus, Schott, Germany) (this is the volume of fuel that it accepts). A series of experiments were carried out in order to determine the influence of (i) polymer residence time in the fuel, (ii) polymer mass, and (iii) fuel volume. By keeping the fuel’s volume and polymers’ mass constant, measurements were performed at different residence times per 10 min. Data given herein present the changes every half hour since the phenomenon had a dynamic balance between bound water and time. It was observed that at the time of 60 min the greatest reduction in water from the fuel was achieved. Subsequently, by keeping the time interval of 60 min, the amount of polymer mass was increased from 0.1 to 0.2 g and 0.3 g. It was observed that the increase in mass did not lead to an increase in the reduction in water. Similarly, the increase in fuel volume from 20 to 40 and 60 mL did not lead to an increase in the removed water.

2.2. Thermal Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric (TGA) and Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) measurements were performed on a simultaneous thermal analyzer STA 503 device (BAEHR Thermo-Analyse GmbH, Hüllhorst, Germany). TGA/DTA tests were conducted in a temperature range from 300 °C to 6000 °C with a heating rate of 20 °C/min, under controlled dry nitrogen (N2) flow, while the weight loss (TGA) and temperature difference (ΔT) were continuously monitored.

2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The calorimetric measurements were performed using a temperature-modulated DSC apparatus (TA Instruments, TA Q200, New Castle, DE, USA), calibrated with sapphires for heat capacity and indium for temperature and enthalpy. The samples, of ~5–12 mg in mass, were sealed in TZero Aluminum Hermetic TA pans (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) in the temperature range from 20 to 250 °C in a high-purity nitrogen atmosphere. Two temperature scans were performed. In scan 1, a heating scan from 20 up to 200 °C at 10 K/min was performed. In scan 2, the sample was cooled from 200 to 20 °C at 20 K/min and heated up to 250 °C at 10 K/min.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Stability (TGA)

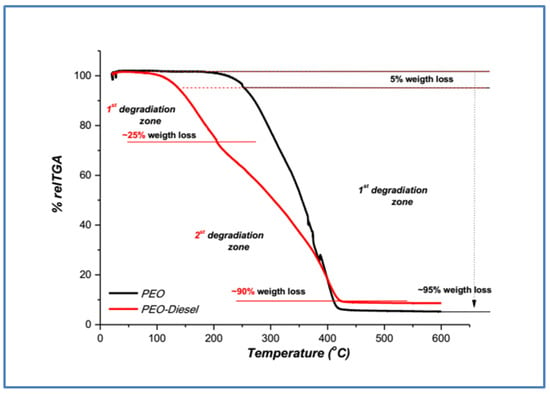

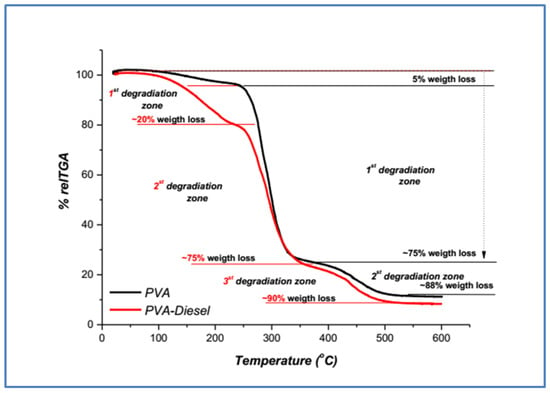

The results of dynamic thermal degradation in the thermobalance are thermogravimetric (TG) (mass loss% vs. temperature), as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, for neat polymers (PEO and PVA) and after their addition in the fuel, PEO-diesel and PVA-diesel.

Figure 3.

TGA thermograms of neat PEO and treatment PEO-diesel polymer samples.

Figure 4.

TGA thermograms of neat PVA and treatment PVA-diesel polymer samples.

3.1.1. Poly(ethylene Oxide) TGA Samples Characterization

From the TGA curve, it is evident that thermal degradation of the PEO polymer occurs through one degradation step in the temperature region from 225 to 420 °C. The degradation of the PEO-diesel sample occurs through two degradation steps; the first weight loss, ~25%, occurs below 200 °C and can be attributed to the evaporation of the adsorbed water and the presence of a quantity of diesel [26]. The second weight loss, ~90%, from 200 to 430 °C due to the polymer degradation. The TGA curve for the PEO-diesel sample moves in lower temperatures, and the characteristics of TG, T5%, Tmax, and weight loss (%) (Table 2) are lower than neat PEO. The PEO-diesel thermal stability, represented as T5%, is significantly lower (251 °C) than the PEO (135 °C). The final mass losses are approximately 5% for PEO and 10% for PEO-diesel.

Table 2.

Thermal degradation characteristics of the neat polymers (PEO and PVA) and the treatment polymer samples (PEO-diesel and PVA-diesel).

3.1.2. Poly(vinyl Alcohol) TGA Samples Characterization

As we can see in Figure 4, there are three main weight-loss stages for both PVA and PVA-diesel samples. For the neat PVA polymer, the first weight loss occurs below 260 °C, while for the PVA-diesel sample, it takes place below 240 °C and is significantly larger, ~20%. This fact can be attributed to the presence of water and diesel adsorption after removing the sample from the fuel [27]. The second weight loss, ~75%, from 260 to 380 °C and the third weight loss, ~90%, from 380 to 500 °C in the case of both samples, take place in the same way and are attributed to the PVA degradation after removal from the fuel. The final mass losses are approximately 12% for PEO and 10% for PEO-diesel.

As can be seen from Figure 3 and Figure 4, for the two treatment polymer samples, PEO-diesel and PVA-diesel, the weight loss that occurs below ~130 °C (T5%) is due to water evaporation (Table 2). The first weight loss zone, from ~130 °C to ~250 °C, is ~25% w/w for the PEO-diesel and ~20% w/w for the PVA-diesel (Figure 3 and Figure 4) and is due to the evaporation of the residual strongly adsorbed water and the adsorbed diesel [12]. After 250 °C, the degradation continues for each of the two treatment polymer samples (PEO-diesel and PVA-diesel) in a similar way as the corresponding neat polymer (PEO and PVA). All samples after ~450 °C lost ~90% w/w of their total mass (Table 2).

3.2. DSC Analysis

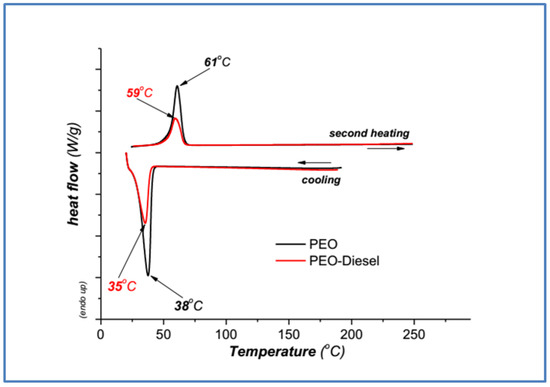

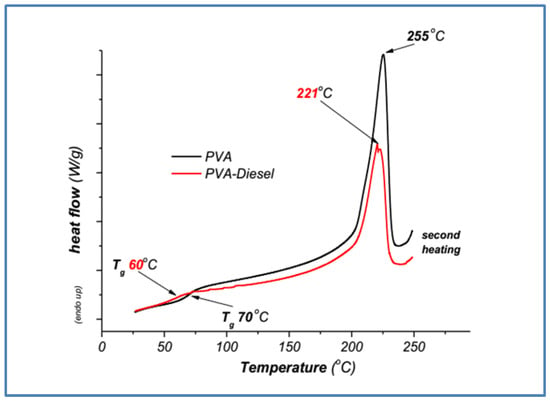

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) analysis was carried out to study the thermal behavior of pure poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) and PEO and PVA after addition in diesel (PEO-diesel, PVA-diesel). In Figure 5 and Figure 6, heat flow (W/g) is plotted against temperature (°C) during the second heating of the samples.

Figure 5.

DSC curves of neat poly(ethylene oxide) and treatment poly(ethylene oxide) samples.

Figure 6.

DSC curves of neat poly(vinyl alcohol) and treatment poly(vinyl alcohol) samples.

3.2.1. Poly(ethylene Oxide) DSC Samples Characterization

The results of the DSC investigation of PEO are shown as normalized DSC curves in Figure 5. The DSC heating curves show one endotherm transition during the cooling, which represents the melting of the crystal phase of the semi-crystalline polymer, and the melting temperature (peak position) at the second heating. It was observed that the addition of PEO in diesel has some influence on the crystallization and melting behavior of the polymer. Furthermore, in the PEO sample after addition in diesel (PEO-diesel), the intensity of the melting peak becomes weaker, perhaps because the crystallinity of PEO decreases, that is, the extent of the amorphous part of the polymer increases due to absorbed water [28].

The melting point (Tm) and crystallization temperature (Tc) are presented in Table 3. A small decrease in melting and crystallization temperatures of PEO is observed. The crystallization temperature was down to 3 °C and the melting point to 2 °C [29].

Table 3.

DSC measurements of the neat polymers (PEO and PVA) and the treatment polymer samples (PEO-diesel and PVA-diesel).

3.2.2. Poly(vinyl Alcohol) DSC Samples Characterization

The glass transition temperature is arguably one of the most important parameters for characterizing polymeric materials. The DSC thermogram in Figure 6 shows the thermal behavior of the PVA and PVA-diesel samples. A decrease in the glass transition temperature from 70 °C (PVA) to 60 °C (PVA-diesel) [30] indicates the effect of diesel as a plasticizer. Also, the melting temperature is reduced from 255 °C to 221 °C, showing a decrease in thermal stability due to the addition of diesel. This decrease is probably due to the presence of diesel, which acts as a plasticizer, reducing the Tg and Tm of PVA. Residual moisture absorbed during the removal of the polymer from diesel appears to further affect its thermal stability. The melting point (Tm) and the glass transition temperature (Tg) are presented in Table 3.

The shifts in melting temperature peaks (Tm) and glass transition temperature (Tg) observed in the DSC curves (Figure 2 and Figure 3) show a more significant decrease, by 10 °C in Tg and by 24 °C in Tm, between pure PVA and PVA-diesel (Table 3). This is probably due to the intense adsorption of water molecules through hydrogen bonds due to the presence of –OH in the polymer, which takes place between the chains of the hydrophilic PVA polymer and the water molecules, as well as the adsorbed diesel fuel. Whereas, in the PEO polymer lacking –OH functional groups, a smaller decrease, by 3 °C in Tg and by 2 °C in Tm, is observed between the pure PEO and PEO-diesel samples (Table 3).

3.3. Effect of Polymer Addition and Humidity of Diesel

In the experimental procedure, the removal of moisture through the polymer was studied as a function of three parameters: residence time of the polymer in the fuel, mass of the polymer added to the fuel, and volume of the fuel into which the polymer is introduced. Keeping two of the three above factors constant, their effect on the removal of moisture from the fuel was studied in order to draw the final conclusions about the action of the polymer (Table 4). From the analysis of the values, the conclusion is drawn that in a time of 60 min and with the use of a polymer mass of 0.1 g in a fuel volume of 20 mL, the greatest reduction in fuel moisture is achieved. Also, after using the polymer, the physicochemical properties of the fuel were observed not to dissolve, so the fuel is immediately channeled for use and does not require storage.

Table 4.

Effect of the hydrophilic polymers PAV and POE on the humidity content of diesel heating fuel.

From the analysis of the values in Table 4, it is concluded that in 60 min and using a PAV mass of 0.1 g in a diesel volume of 20 mL, a reduction in fuel humidity from 62 mg/g to 50 mg/g is achieved, i.e., a reduction of approximately 20%, and using a POE mass of 0.1 g in a diesel volume of 20 mL, a reduction in fuel humidity from 62 mg/g to 53 mg/g is achieved, i.e., a reduction of approximately 15%. Other studies performing kinetics [31] with hydrogel for water removal from marine diesel showed a peak of water removal in just 60 min of approximately 80%.

Moreover, it was considered useful to determine whether the introduction of the polymer into the fuel affects the fuel’s other physicochemical properties, making it unsuitable for use in combustion engines. Thus, measurements of a series of physicochemical properties of the fuels were made before and after the use of the polymer, and the results are presented in Table 5. As shown in Table 5, the physicochemical properties of the fuel are not affected by the addition of the polymer, and they continue to have values within the limits. Also, in the case of the polar polymer, a reduction in the amount of sulfur in the fuel is observed, which is of particular importance due to the risk of sulfur emissions after combustion, which can harm the environment.

Table 5.

Effect of polymers with and without polar groups on the physicochemical properties of diesel fuel.

The experimental findings indicated that the use of polymers reduces the humidity content in the fuel, specifically by approximately 20% and by 15%, respectively. This is of great importance since the risk of inefficient combustion caused by humidity can be reduced. The explanation for the reduction in humidity by polymers is based on the creation of hydrogen bonds. For polymer PVA, these bonds form between the hydroxyl group of the polymer and the water molecules of the fuel. For polymer POE, these bonds form between the ether group of the polymer and the water molecules of the fuel and are stronger than the forces between water molecules and fuel molecules with 12 to 18 carbon atoms [32].

At this stage, the applied techniques provided information only on water retention and not on the mechanism of its binding to polymers. This is an interesting part, but it is a study with chemical criteria that can be performed in other works with more specialized techniques. From the analysis carried out with the above methods, it was found that the hydrophilic polymer interacts with the fuel. After the polymer enters the diesel and is removed from it by filtration, it has bound an amount of moisture that comes exclusively from the fuel. Because the polymers have a high molecular weight and are water-soluble through (polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) MW 85,000–125,000 fully hydrolyzed (99+%), polyethylene oxide (PEO) MW > 100,000 fully hydrolyzed (99+%)), the numerous polar groups adsorb a large number of water molecules from the fuel. This interaction removes water from the fuel, and the use of the fuel becomes more environmentally friendly and more efficient for the industry.

High levels of sulfur in diesel are harmful to the environment because they prevent the use of catalytic diesel particulate filters that control particulate emissions, as well as more advanced technologies such as nitrogen oxide adsorbers to reduce emissions. In addition, sulfur in the fuel is oxidized during combustion, producing sulfur dioxide and sulfur trioxide, which in the presence of water vapor are quickly converted to sulfuric acid, one of the chemical processes that results in acid rain. However, the sulfur reduction process also reduces the lubricity of the fuel, which means that additives must be added to the diesel to help lubricate engines [33,34].

The reduction of sulfur by using the polymer gives the opportunity to study the action of polar polymers in this direction. Especially for Greece, where the quantity in metric tons for the used heating diesel for the period 2015–2022 was at a very high rate (up to 1,388,665) [35]. With the observation that the use of the polymer reduced the sulfur from 941 mg to 937 mg, i.e., approximately 4 mg per kg of fuel, it becomes clear that for the total use of heating diesel, the sulfur percentage could be reduced if the above methodology were used in the processing of oil by approximately 42 tons of sulfur.

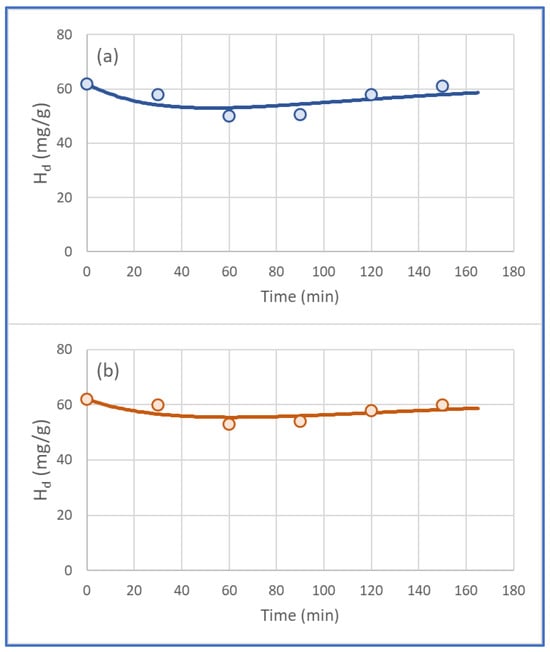

4. Theoretical Prediction of Humidity Content vs. Time

In order to predict the humidity of diesel vs. time after the addition of PVA and POE, a first-order exponential moisture absorption model can be used (Equation (1)).

where (mg/g) is the moisture content of diesel at time t (min), (mg/g) is the equilibrium moisture content of diesel, (mg/g) is the moisture content of the polymer at time t, (mg/g) is the equilibrium moisture content of the polymer, (1/min) is the first-order rate coefficient for moisture removal due to the polymer, and (1/min) is the first-order rate coefficient for moisture absorbance of diesel. The initial moisture content of the polymers (t = 0) was assumed to be negligible.

The mathematical model was calibrated to the experimental data (Table 4) in order to obtain the values for the kinetic parameters. The fitting process and the solution of the differential equation vs. time were conducted using the numerical algorithm implemented in the Aquasim computer program (version 2.1) [36]. This was achieved by minimizing the sum of squared deviations between experimentally measured data and model-predicted values, following the Least Squares Method. The mathematical equations were then solved using the DASSL algorithm [37], which is based on the implicit (backward differencing) variable step, variable-order Gear integration technique. The integration begins with by the program with default initial values for the kinetic parameters (equal to 1). Table 6 shows the values of (1/min) and (1/min), obtained from the fitting of Equation (1) to the experimental data, as well as the values of and (mg/g) and the correlation coefficient R2.

Table 6.

Values of parameters based on Equation (1) according to the least squares method using Aquasim.

The higher values of for the PVA verify the higher humidity removal using this polymer in diesel heating fuel. The values of for both polymers were similar, as was expected, since the 2nd term on the right side of Equation (1) depends on the properties of diesel only. Higher equilibrium moisture content ( (mg/g)) was observed for the polymer for the PVA than the POE, indicating that PVA has greater adsorption capacity. The value of the equilibrium moisture content of diesel ( (mg/g)), was kept equal to the initial experimental value of 62 mg/g, considering that is the value at equilibrium for the conditions used.

Figure 7 represents the theoretical and experimental profile of moisture vs. time for both polymers used in this study. Results from the fitting process indicated that the theoretical calculations were in good agreement with the experimental data. The moisture variations vs. time for both PVA and POE were adequately simulated (Figure 7), although the R2 values were not high enough (Table 6). The discrepancy between graphical presentation and statistics was due to the limited changes in moisture content ( (mg/g)) of diesel vs. time t [38].

Figure 7.

Experimental (markers) and theoretical (lines) profiles vs. time (60 min) of diesel moisture using (a) 0.1 g PVA and (b) 0.1 g POE polymer, respectively, in a diesel volume of 20 mL.

It should be noted that the mathematical model predicted, in accordance with the data shown in Table 4 and Figure 7, for both PVA and PEO, that the moisture content reaches its lowest value at 60 min and then increases at longer residence times. This was probably due to the dynamic equilibrium between bound water on the surface of the polymer and residence time. A mechanism like a sponge that binds water, reaches saturation, and removes the water again can be proposed. However, specialized techniques must be applied to study the binding speed and the water-binding mechanisms, which, however, are not a field of research in this work. The final conclusion of the 60 min removal time can be directly applied to the industrial process.

5. Conclusions

The proposed methodology can complement the existing process of removing moisture from liquid fuels, which is based mainly on mechanical applications. Specifically, based on the observation that polar groups of amino acids show a change in their degree of hydration in aqueous solutions (reference), an attempt was made to study whether this behavior can also occur in petroleum distillation products. Thus, the phenomenon of the polymer entering the fuel and its removal through filtration was studied, resulting in a reduction in the moisture content of the fuel as a function of specific parameters, such as the residence time of the polymer in the fuel, the mass of the polymer added to the fuel, and the volume of fuel into which the polymer is introduced. From the application of the proposed methodology, it becomes clear that the properties of the fuel not only have not changed, but in many cases they have shown significant improvement, helping to make their use more efficient and environmentally friendly.

Based on the above methodology, the possibility is given to investigate the general application of the method in the removal of moisture and acidity from liquid natural fuels as well as from biodiesel. The goal is to optimize their suitability parameters so that ultimately their use is more environmentally friendly, and the entire method can be part of anti-pollution technologies for the environment. The points of the proposed methodology that make it necessary for the use or support and complement of the mechanical methods currently applied for the removal of moisture from fuels are the following:

- The polymer does not remain in the fuel after its use.

- The amount of polymer used is of the order of additives in fuels.

- The method can be applied at any point in the production process and transportation of petroleum products but also in their consumption areas.

- The raw material for the synthesis of the polymer, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) MW 85,000–125,000 fully hydrolyzed (99+%), polyethylene oxide (PEO) MW > 100,000 fully hydrolyzed (99+%), is harmless and environmentally friendly.

- The cost of acquiring the polymer is low, while it can be synthesized in the laboratory and used more than once.

- Applications on a large scale of thermal treatments of crude oil that may alter the characteristics of the final products are avoided. Of course, the application of the proposed methodology to the production process of petroleum products must undergo further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G.T. and A.K.; methodology, C.G.T., A.K., A.S., I.A.V., and G.T.; investigation, A.S., I.A.V., G.T., and A.K.; resources, C.G.T. and A.K.; data curation, A.S., I.A.V., and G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, G.T., C.G.T., and A.K.; writing—review and editing, I.A.V. and C.G.T.; supervision, C.G.T., A.K., and I.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ershov, M.A.; Savelenko, V.D.; Shvedova, N.S.; Kapustin, V.M.; Abdellatief, T.M.M.; Karpov, N.V.; Dutlov, E.V.; Borisan, D.V. An evolving research agenda of merit function calculations for new gasoline compositions. Fuel 2022, 322, 124209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatief, T.M.M.; Ershov, M.A.; Kapustin, V.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Kamil, M.; Olabi, A.G. Recent trends for introducing promising fuel components to enhance the anti-knock quality of gasoline: A systematic review. Fuel 2021, 291, 120112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, J.H.; Handwerk, J.H.; Glenn, E. Petroleum Refining: Technology and Economics, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Knothe, G.; Sharp, C.A.; Ryan, T.W. Exhaust Emissions of Biodiesel, Petrodiesel, Neat Methyl Esters, and Alkanes in a New Technology Engine. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeq, A.M. Combustion Advancements: From Molecules to Future Challenges, 1st ed.; Lulu Press, Inc.: Morrisville, CA, USA, 2023; ISBN 979-8-9907836-1-4. [Google Scholar]

- AFS. Water Contamination in Fuel: Cause and Effect—American Filtration and Separations Society; Archived from The Original on 23 March 2015; AFS: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhan Opinder, K.; Tang Sheng, Y.; Brinkman Dennis, W.; Carley, B. Causes of poor filterability in jet fuels. Fuel 1998, 67, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, J.; Tremblay Andrι, Y.; Dubι Marc, A. Glycerol removal from biodieselusing membrane separation technology. Fuel 2010, 89, 2260–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastek, T.Q. Improving cold flow properties of canola-based biodiesel. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Tatarchuk, B.J. Supported silver adsorbents for Sulphur removal from hydrocarbon fuels. Fuel 2010, 89, 3218–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanaktsidis, C.G.; Favvas, E.P.; Tzilantonis, G.T.; Scaltsoyiannes, A.V. A new fuel (D-BD-J) from the blending of conventional diesel, biodiesel and JP8. Fuel Proc. Techn. 2014, 127, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanaktsidis, C.G.; Christidis, S.G.; Favvas, E.P. A novel method for improving the physicochemical properties of diesel and jet fuel using polyaspartate polymer additives. Fuel 2013, 104, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallensleben, M.L. Polyvinyl Compounds, Others. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Alavi, S. Recent Advances in Starch, Polyvinyl Alcohol Based Polymer Blends, Nanocomposites and Their Biodegradability. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 85, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelnia, H.; Ensandoost, R.; Moonshi, S.S.; Gavgani, J.N.; Vasafi, E.I.; Ta, H.T. Freeze/thawed polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels: Present, past and future. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 164, 110974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyethylene Glycol as Pharmaceutical Excipient. Available online: https://pharmaceutical.basf.com (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Kahovec, J.; Fox, R.B.; Hatada, K. Nomenclature of regular single-strand organic polymers. Pure Appl. Chem. 2002, 74, 1921–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zhong, T.; Wan, W.; Yang, Q.; Li, A.; Zhang, X.; Lin, M. Bioprinting-Based PDLSC-ECM Screening for in Vivo Repair of Alveolar Bone Defect Using Cell-Laden, Injectable and Photocrosslinkable Hydrogels. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 3534–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 12185:2024; Crude Petroleum, Petroleum Products and Related Products—Determination of Density—Laboratory Density Meter with an Oscillating U-Tube Sensor. 2nd ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 3405:2019; Petroleum and Related Products from Natural or Synthetic Sources—Determination of Distillation Characteristics at Atmospheric Pressure. 5th ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 2719:2016; Determination of Flash Point—Pensky-Martens Closed Cup Method. 4th ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 12937:2000; Petroleum Products—Determination of Water—Coulometric Karl Fischer Titration Method. 1st ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- ISO 20846:2019; Petroleum Products—Determination of Sulfur Content of Automotive Fuels—Ultraviolet Fluorescence Method. 3rd ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Borges, M.E.; Díaz, L.; Gavín, J.; Brito, A. Estimation of the content of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) in biodiesel samples from dynamic viscosity measurements. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4264:2018; Petroleum Products—Calculation of Cetane Index of Middle-Distillate Fuels by the Four Variable Equation. 3rd ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Kjellander, R.; Florin, E. Water structure and changes in thermal stability of the system poly(ethylene oxide)–water. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases 1989, 12, 3901–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, H.; Daneault, C. Chemical Modification of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) in Water. Appl. Sci. 2015, 5, 840–850. [Google Scholar]

- Takei, T.; Kurosaki, K.; Nishimoto, Y.; Sugitani, Y. Behavior of Bound Water in Polyethylene Oxide Studied by DSC and High-Frequency Spectroscopy. Anal. Sci. 2002, 18, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jin, J.; Song, M.; Pan, F. A DSC study of effect of carbon nanotubes on crystallization behavior of poly(ethylene oxide). Thermochim. Acta 2007, 456, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyfantis, G.C.; Cingolani, R.; Athanassiou, A.; Bayer, I.S. Effect of trifluoroacetic acid on the properties of polyvinyl alcohol and polyvinyl alcohol–cellulose composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 277, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, I.D.; dos Santos, F.B.; Miranda, N.T.; Vieira, M.G.A.; Fregolente, L.V. Polymer hydrogel for water removal from naphthenic insulating oil and marine diesel. Fuel 2022, 324, 124702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favvas, E.P.; Tsanaktsidis, C.G.; Tzilantonis, G.T.; Christidis, S.G. H2O removal from diesel and JP8 fuels: A comparison study between synthetic and natural dehydration agents. J. Engin. Sci. Techn. Rev. 2014, 4, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Emission Facts: Average Carbon Dioxide Emissions Resulting from Gasoline and Diesel Fuel; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Date Anil, W. Analytic Combustion: With Thermodynamics, Chemical Kinetics and Mass Transfer; Google eBook; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Consumption of Petroleum Products, Under the Link “Environment and Energy > Energy > Petroleum Products (Consumption)”. 2022. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/el/statistics/-/publication/SDE15/- (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Reichert, P. Aquasim 2.0-User Manual, Computer Program for the Identification and Simulation of Aquatic Systems; EAWAG: Dübendorf, Switzerland, 1998; ISBN 3-906484-16-5. [Google Scholar]

- Petzold, L. A description of DASSL: A differential/algebraic system solver. In Scientific Computing; Stepleman, R.E., Ed.; IMACS/North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliadou, I.A.; Bari Chowdhury, A.K.M.M.; Akratos, C.S.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Pavlou, S.; Vayenas, D.V. Mathematical modeling of olive mill waste composting process. Waste Manag. 2015, 43, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).