1. Introduction

Rock mass stability assessment is critical for ensuring the safety of continuous strata engineering projects [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Sandstone and mudstone frequently coexist in such formations, and differences in the shear strength of their rock mass–structural plane–rock block systems significantly influence foundation treatment design depth, construction method selection, and underground cavern support planning [

5,

6]. However, the mechanisms and controlling factors of these shear strength parameters remain poorly understood, hindering engineering strategy optimization. This study aims to address this gap by elucidating the differences in shear strength parameter correlations between sandstone and mudstone—essential for stratified adaptive design in continuous strata engineering. The novelty of this work lies in the development of an intelligent multi-parameter correlation model using random forest algorithm, which enables high-accuracy prediction and sensitivity analysis of shear strength parameters, overcoming limitations of traditional methods. Given the considerable differences between sandstone and mudstone in structural characteristics, mechanical behavior, and environmental response, it is essential to identify the key controlling factors of their shear strength parameter correlations. Recent advances in data-driven rock mechanics modeling have enabled more accurate predictions of anisotropic shear strength behavior, particularly through machine learning techniques that capture nonlinear interactions among rock mass parameters [

7,

8]. However, the intrinsic correlation mechanisms between rock mass, structural plane, and structural block parameters in sandstone and mudstone remain poorly quantified, especially in terms of how lithological contrasts—such as mineral composition, fracture roughness, and structural plane development—govern their respective shear strength behaviors [

9,

10].

Current research on the mechanical parameters of rock masses, structural planes, and structural blocks primarily encompasses three categories: theoretical studies, experimental investigations, and numerical simulations. Theoretical approaches often rely on engineering experience and quantitative evaluation methods, such as the Geological Strength Index (GSI), K-means clustering algorithms, Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines (NURBS), Rock Quality Designation (RQD), and the BQ system. These methods quantitatively characterize rock mass integrity, structural plane and block development, and mechanical properties. While K-means clustering improves the efficiency of grouping structural plane orientations, it is highly sensitive to initial centroid selection. NURBS techniques accurately describe complex structural plane morphology but neglect the random distribution of microfractures within structural blocks. The RQD index and the BQ system complement each other in evaluating rock mass integrity: RQD reflects drill core quality, whereas BQ incorporates rock strength and structural plane characteristics. However, both overlook the mechanical interactions among structural blocks. Although existing theoretical methods improve parameter acquisition efficiency, they remain limited by over-simplification of intra-block interactions, significant subjectivity in parameter quantification, and insufficient correlation analyses [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Experimental studies include laboratory and field tests to investigate the mechanical properties of rock masses. Laboratory tests, such as uniaxial compression, triaxial compression, and direct shear tests, yield parameters including peak strength, residual strength, and deformation characteristics. Field tests evaluate the mechanical behavior of rock masses and structural planes under in situ conditions using monitoring and in situ testing. Although these methods provide valuable insights and a reliable experimental basis for theoretical research, laboratory tests are subject to scale effects, often overestimating strength compared to large-scale engineering conditions. Field tests cannot adequately replicate deep stress environments due to boundary condition limitations. Moreover, a reliable cross-scale correlation model linking fine-scale crack propagation in laboratory tests with macroscopic damage patterns under field conditions is still lacking, limiting the practical application of test data in engineering contexts [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Numerical simulations, commonly conducted using software such as FLAC, UDEC, and MIDAS, offer insights into rock wedge stability, damage mechanisms, and mechanical behavior of rock masses. UDEC, a discrete element software, is effective in simulating discontinuous deformations such as block slip and rotation, but it inaccurately represents the time-dependent behavior of mudstone softening in water. FLAC3D, based on the finite difference method, handles large deformations in continuous media well but requires simplifications when modeling complex fracture networks. The Synthetic Rock Mass (SRM) approach allows the incorporation of random fractures but requires improvements in computational efficiency and engineering applicability. Despite the ability to simulate complex geological conditions and loading environments, current numerical methods cannot fully account for the heterogeneity, anisotropy, and complex fracture networks in rock masses, and often overlook intricate interactions among rock masses, structural planes, and structural blocks [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In summary, while significant progress has been made in understanding rock mass mechanical behavior and damage mechanisms, research on the sensitivity of sandstone and mudstone to rock mass–structural plane–structural block mechanical parameter correlations remains limited. Moreover, studies on the quantitative differences in their influencing factors—such as how differences in mineral composition and structural characteristics between sandstone and mudstone influence the correlation strength among cohesion, internal friction angle, and uniaxial compressive strength—remain insufficient. Addressing this gap requires the development of an intelligent analytical approach to evaluate these key parameters and their correlations.

Especially, investigating the sensitivity of sandstone and mudstone in rock mass--structural plane--structural block mechanics parameter correlations and their differences is essential for accurately predicting and managing engineering stability. With its powerful feature extraction and learning capabilities, the random forest model exhibits significant advantages in addressing the issue of correlation and conducting sensitivity analysis of changes in the mechanical parameters of nonhomogeneous materials. In this study, a new random forest model is proposed and applied as a research tool, which opens up new possibilities for solving the correlation problem and conducting sensitivity analysis based on multi-source data. Compared to previous shear strength correlation research, which often relies on simplified theoretical or experimental approaches, our work provides a comprehensive data-driven framework that captures nonlinear interactions and lithological contrasts, offering a novel contribution to rock mechanics and engineering design [

23].

Despite advances in rock mechanics, quantitative estimates of shear strength for sandstone and mudstone in continuous strata remain limited, particularly in terms of multi-parameter correlation and sensitivity analysis. The scientific gap lies in the unclear mechanistic understanding of why the correlation among rock mass, structural plane, and structural block parameters differs fundamentally between sandstone and mudstone—due to lithological contrasts in mineral composition, fracture roughness, and structural plane characteristics. Addressing this gap requires the development of an intelligent analytical approach to evaluate these key parameters and their correlations. The main research questions of this study are: How do differences in mineral composition and structural characteristics between sandstone and mudstone influence the correlation strength among cohesion, internal friction angle, and uniaxial compressive strength? What are the dominant sensitive factors controlling the shear strength parameter correlations in sandstone versus mudstone? Can a random-forest-based model effectively predict rock mass displacement response and identify threshold behaviors in these lithologies?

Especially, investigating the sensitivity of sandstone and mudstone in rock mass–structural plane–structural block mechanics parameter correlations and their differences is essential for accurately predicting and managing engineering stability. With its powerful feature extraction and learning capabilities, the random forest model exhibits significant advantages in addressing the issue of correlation and conducting sensitivity analysis of changes in the mechanical parameters of nonhomogeneous materials. In this study, a new random forest model is proposed and applied as a research tool, which opens up new possibilities for solving the correlation problem and conducting sensitivity analysis based on multi-source data.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the materials and methods, including sample preparation, testing procedures, and the random forest modeling framework.

Section 3 presents the results and discussion, covering mechanical parameter trends, correlation analysis, sensitivity assessment, and nonlinear mechanisms.

Section 4 provides the main conclusions and engineering implications.

2. Materials and Methods

The typical sandstone–mudstone lithological assemblage commonly occurs in continuous strata engineering projects. Variations in the shear strength characteristics of rock mass–structural plane–structural block systems significantly affect foundation treatment depth, construction method selection, and underground cavern support design [

24,

25]. Therefore, understanding the mechanical response of sandstone and mudstone under varying rock mass structures, mechanical properties, and environmental conditions is essential. In particular, accurate prediction models for the mechanical parameters of rock mass–structural plane–structural block systems are needed. It is crucial to elucidate the intrinsic correlations among influencing factors and their sensitivity.

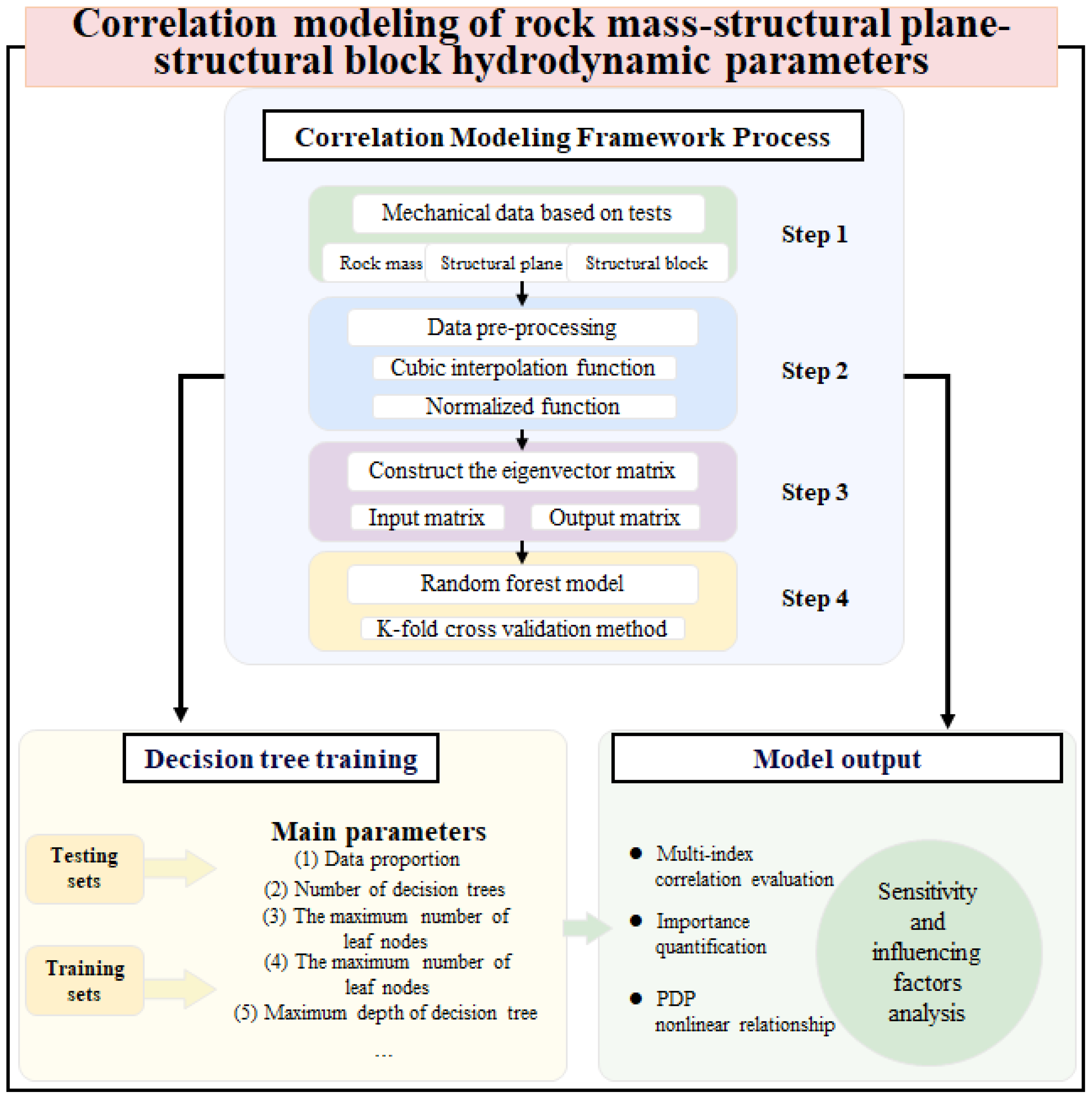

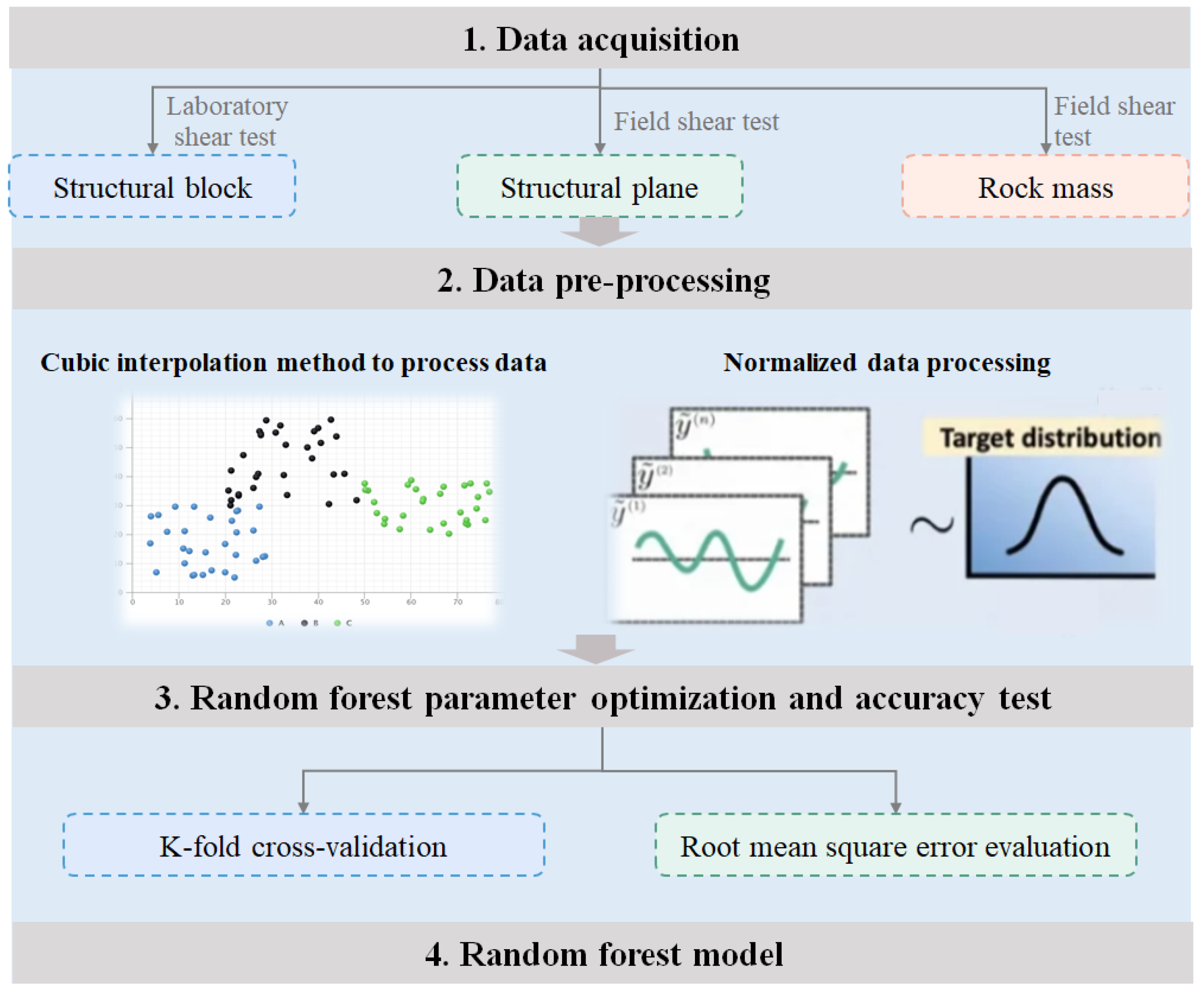

This study systematically analyzes the mechanical response of rock masses, structural planes, and structural blocks in sandstone and mudstone under different stress conditions through laboratory and field tests. Key parameters include structural block stress, structural plane strain, stress transfer across structural planes, structural plane slip, external rock mass loading, and rock mass displacement response. These data underpin the analysis of differences in shear strength parameter correlations between sandstone and mudstone. Subsequently, structural block stress, structural block strain, structural plane stress transfer, structural plane slip, and external rock mass loading are used as input eigenvectors, while the rock mass displacement response index is designated as the output eigenvector. These parameters are integrated into a correlation model for dynamic variations in rock mass–structural plane–structural block parameters, constructed using a random forest algorithm. Through model training and optimization, a quantitative relationship among the physical parameters of rock mass–structural plane–structural block systems is established. Finally, an importance analysis of key features reveals the sensitivity of each influencing factor, clarifying the differences in controlling factors between sandstone and mudstone in shear strength parameter correlations. The research framework and methodology flow are illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.1. Study Area Description

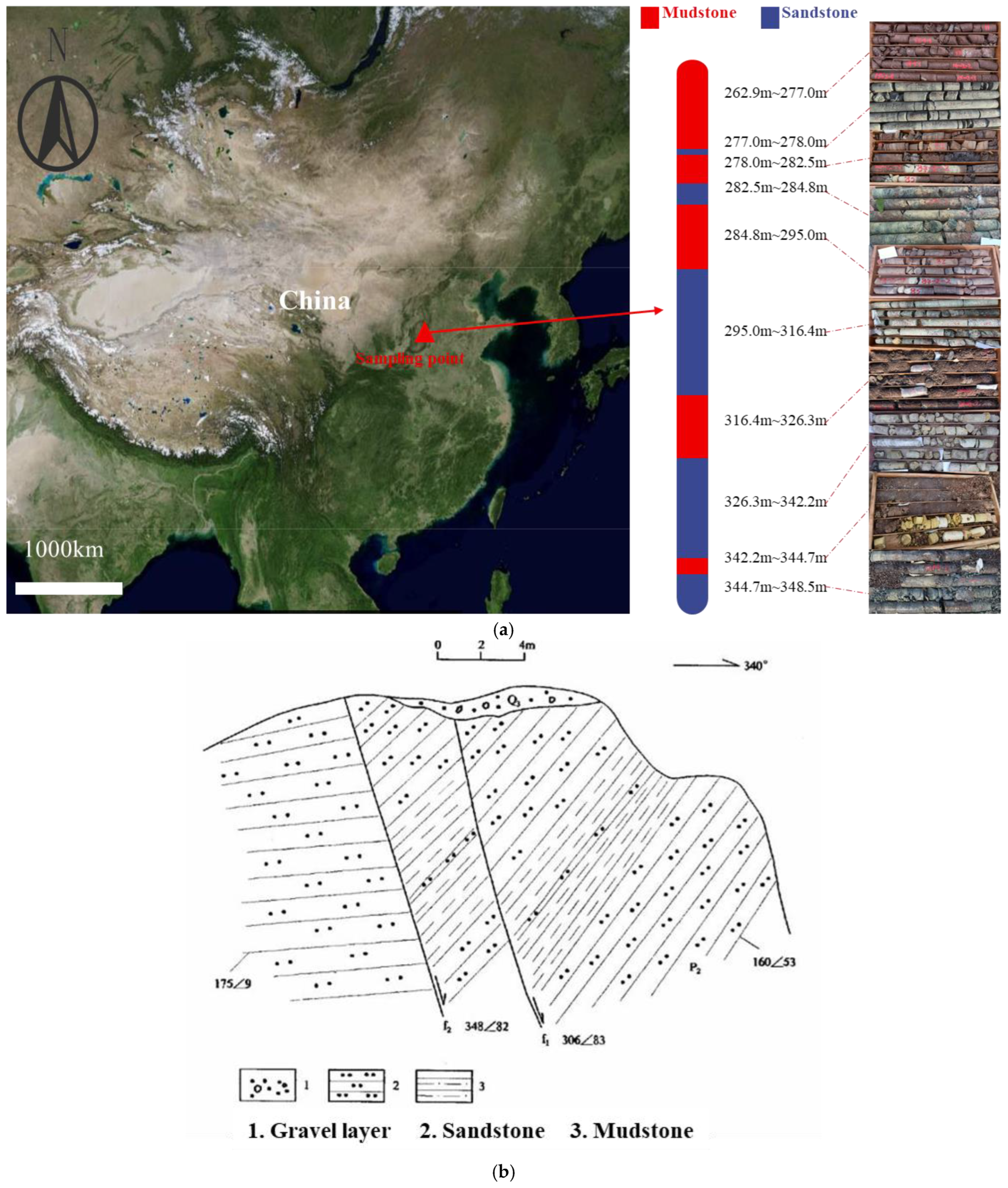

The study area is situated near a representative pumped storage station in North China (

Figure 2). The terrain, ranging from valley floors (1040 m) to peaks (1436 m), constitutes a mid-mountain geomorphological region. The area exhibits homogeneous geomorphic characteristics, including river terraces, floodplains, slope wash deposits, and local landslide features. The geology of the station area is dominated by Carboniferous and Permian bedrock, overlain by Quaternary unconsolidated sediments. The deeply buried Carboniferous strata beneath the Permian sequence have a negligible influence on project construction. The widely exposed Permian strata comprise terrestrial clastic sedimentary rocks deposited in alternating fluvial and lacustrine environments. These strata dip at 5° to 15°, generally gently upstream along the left bank, and exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity and lithological diversity, resulting in markedly variable engineering properties. Lithologies include mudstone, silty mudstone, muddy siltstone, and sandstone.

To provide quantitative geological context, a stratigraphic column (

Figure 2b) has been added, showing layer thicknesses, bedding dip angles, and formation names. The study area is geographically located at approximately 40° N latitude and 116° E longitude, with a scale of 1:50,000 for spatial reference. The strata are generally continuous laterally, but local variations occur due to tectonic activity and erosion. Groundwater levels are typically shallow (1–5 m below surface) in the valley areas, and weathering effects are prominent in the surface layers, particularly in mudstone, which exhibits strong weathering to depths of 10–40%. These factors were considered during sample collection and testing to ensure representative mechanical properties.

2.2. Sample Sources and Test Methods

The test samples—mudstone and sandstone from the study area—exhibit considerable variation in continuous thickness (ranging from 1 m to 20 m, with the thickest section reaching 41 m, as revealed by the drill holes). Sandstone, comprising approximately 35% of the project area, is primarily moderately hard rock. Micritic sandstones are predominantly hard and exhibit no rapid surface weathering or disintegration. Conversely, mudstone is widely exposed in the upper reservoir area. It exhibits lower hardness and weathering resistance, and the surface layer is predominantly strongly weathered, comprising approximately 10–40% of the exposures.

A total of 320 valid datasets were obtained from laboratory and field experiments, including 160 sandstone samples and 160 mudstone samples. All mechanical parameters (e.g., cohesion, internal friction angle, and uniaxial compressive strength) were obtained from our own laboratory and field tests, not compiled from existing studies or reports. The testing methods followed the International Society for Rock Mechanics (ISRM) suggested methods for rock characterization and direct shear tests, as well as the Chinese National Standard (following ISRM [

26] and GB/T 50266-2013 [

27] standards) for engineering rock mass tests [

28,

29].

The key mechanical parameters for sandstone and mudstone, derived from these tests, are summarized in

Table 1.

The strata are laterally continuous, but localized structural planes may occur due to faulting or jointing. Groundwater and weathering significantly influenced the sample properties: groundwater seepage was observed in drill holes at depths of 5–10 m, leading to reduced shear strength in mudstone. Weathering effects were mitigated by collecting samples from fresh bedrock where possible, and tested specimens were conditioned to simulate in situ moisture content.

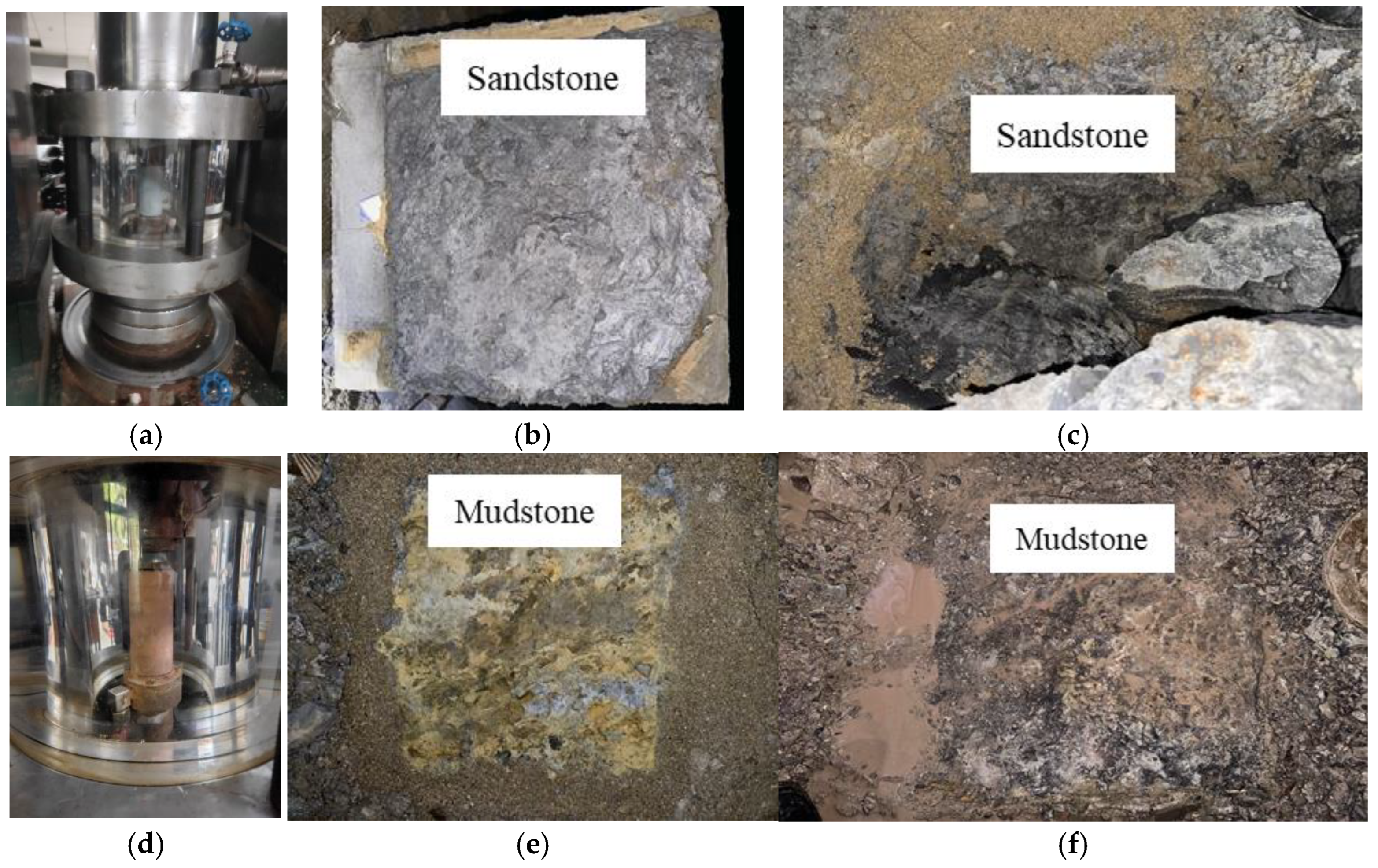

The experimental program comprises three primary tests (

Figure 3):

Intact rock shear test: Intact rock blocks are collected from the site; cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 50 mm are extracted from these blocks using a core drilling machine; both ends of the specimens are polished and processed into standard cylindrical specimens with a height of 100 mm using a grinding machine, followed by drying. The specimens are placed at the center of the bearing platform and loaded at a rate of 0.5 MPa/s until failure; stress and strain of the intact rock blocks are recorded.

Structural plane shear test: The direct shear method is employed; a pad is placed on the loading surface using cement mortar paste, ensuring the pad is perpendicular to the predetermined shear surface. After pad placement, the force transfer block, hydraulic jack, and pad are positioned sequentially; mortar is applied between the pad and the reaction frame. Displacement transducers are installed on the test specimen and bedrock surface for measurement; the maximum predicted shear load is then applied in 8 increments. A time-controlled procedure is adopted, with each load increment applied at 5 min intervals; displacement readings are taken before and after each increment. As the shear point approaches, load variations and corresponding displacements are closely monitored and recorded; data on stress transfer and slip along the structural plane are obtained.

Rock mass shear test: The direct shear method is employed, following a procedure similar to the structural plane shear test; upon test completion, the shear surface area is accurately measured, and the extent of damage is documented in detail; ultimately, external rock mass loading and displacement response are acquired.

Figure 3.

Test procedures: (a) sandstone structural block shear test; (b) sandstone structural plane shear test; (c) sandstone rock mass shear test; (d) mudstone structural block shear test; (e) mudstone structural plane shear test; (f) mudstone rock mass shear test.

Figure 3.

Test procedures: (a) sandstone structural block shear test; (b) sandstone structural plane shear test; (c) sandstone rock mass shear test; (d) mudstone structural block shear test; (e) mudstone structural plane shear test; (f) mudstone rock mass shear test.

Sample Preparation: The test samples were collected from fresh bedrock exposures in the study area to minimize weathering effects. For structural block tests, intact rock blocks were extracted using a diamond core drill to obtain cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 50 mm. The specimens were then trimmed and polished to achieve a height of 100 mm, ensuring parallel ends as per ISRM standards. For structural plane and rock mass tests, natural structural planes were preserved, and samples were prepared by cementing the rock surfaces to steel plates using high-strength epoxy resin to simulate in situ conditions. All specimens were conditioned to in situ moisture content by saturating them with water for 48 h prior to testing, reflecting typical field conditions.

Loading Conditions: All tests were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions at a constant temperature of 20 °C. The loading rates followed ISRM suggestions: for structural block shear tests, a rate of 0.5 MPa/s was applied until failure; for structural plane and rock mass shear tests, the flat-push method was used with incremental loading (8 steps to the maximum predicted shear load), each held for 5 min to allow for displacement stabilization. The tests were performed using a servo-controlled hydraulic system to ensure precise load application.

Scale Effects: To address scale effects, we compared laboratory-scale results with field-scale observations. Laboratory specimens represent small-scale behavior, but we calibrated our models using field data from in situ tests to ensure relevance to engineering scales. The random forest model inherently accounts for some scale variations through its learning from multi-scale data, including both laboratory and field measurements.

Standard Compliance: All testing procedures strictly adhered to the ISRM suggested methods and the Chinese National Standard GB/T 50266-2013 for engineering rock mass tests. This includes specimen preparation, testing apparatus calibration, and data recording protocols to ensure reliability and comparability. The testing equipment was regularly calibrated, and all data were validated through repeatability checks.

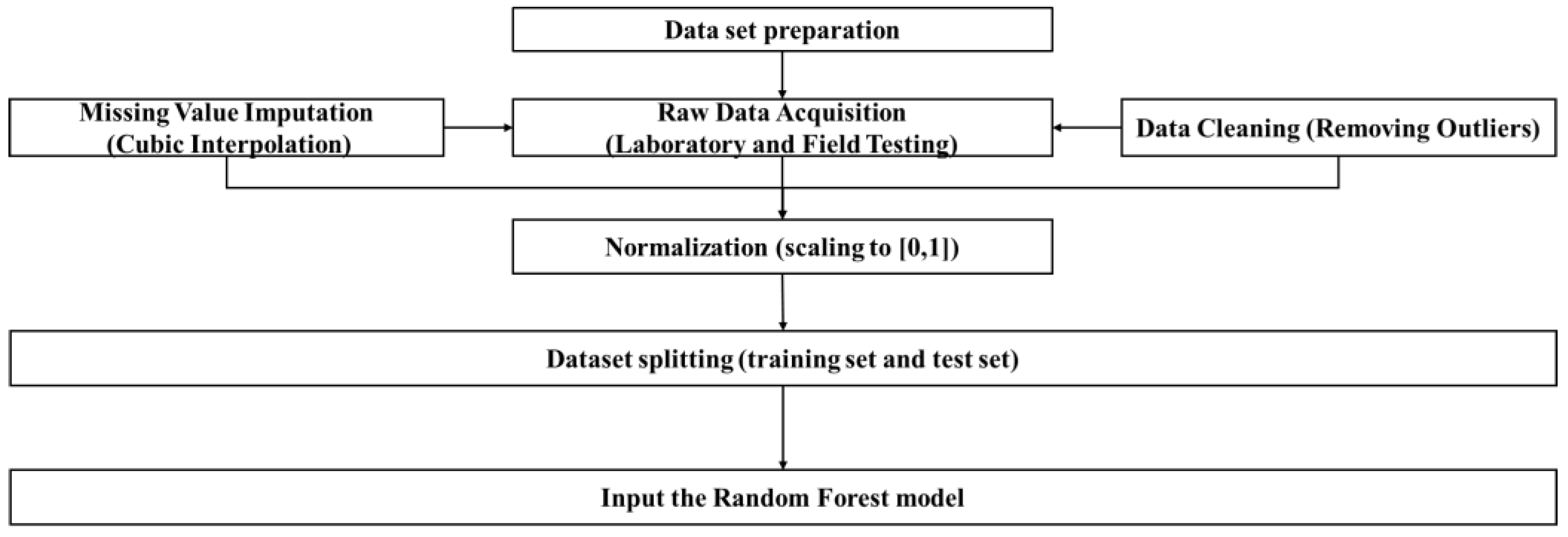

2.3. Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

A total of 320 valid datasets (160 for sandstone and 160 for mudstone) are obtained from laboratory and field experiments. The raw test data were digitized from experimental records and standardized using cubic interpolation for gap filling of missing values. Outliers were identified and removed based on statistical methods (e.g., values beyond ±3 standard deviations from the mean). The selected input parameters include structural block stress, structural block strain, structural plane stress, structural plane slip, and rock mass external load, while rock mass displacement response (unit: mm) serves as the output parameter (target variable). Note that the target is not shear strength or friction angle, but displacement, which is directly related to stability assessment.

The model’s prediction accuracy and convergence capability are influenced by the type of data used for the input variables. Given the variations in magnitude among the influencing factors, normalization is performed to scale all data to the range [0, 1]. This step prevents excessive discrepancies in data scales, mitigating risks of numerical instability and improving model convergence efficiency. This ensures that each parameter contributes effectively to the prediction process. The normalization is crucial for sensitivity analysis as it ensures all features are on a comparable scale.

Table 2 summarizes the dataset, including the number of samples, input variables, target variable, and parameter ranges for both sandstone and mudstone. The datasets for sandstone and mudstone are of similar size (160 each), ensuring data balance and minimizing potential bias in the model.

Figure 4 shows the data-processing pipeline, illustrating the steps from raw data acquisition to model input.

2.4. Random Forest Algorithm-Based Correlation Model for Rock Mass–Structural Plane–Structural Block Variation in Physical Parameters

2.4.1. Correlation Model Construction

The correlation among rock mass–structural plane–structural block physical parameters is inherently nonlinear and influenced by multiple interacting factors. Traditional univariate or bivariate analyses often fail to capture these complex relationships. To address this limitation, we adopt a multivariate machine learning approach—the random forest algorithm—which is capable of handling high-dimensional data, quantifying feature importance, and providing robust predictions even in the presence of noise and missing values. Therefore, based on the data obtained from shear tests conducted on rock mass, structural planes, and structural blocks, this study models and analyzes the relationship among the shear strengths of rock mass–structural plane–structural blocks.

Model Configuration and Hyperparameters: The random forest model was configured with the following hyperparameters: number of trees (ntree) = 100, maximum tree depth (max_depth) = 10, number of features per split (mtry) = 3, and training/test split ratio = 70:30. The dataset was partitioned using 10-fold cross-validation, with 9 folds for training and 1 fold for testing in each iteration. The process was repeated 10 times, and the average performance metrics (R2, RMSE, MAE) along with their standard deviations were calculated to ensure robustness. To ensure reproducibility, we fixed the random seed (seed = 42) during model training. The results were consistent across multiple runs with different random seeds, indicating low uncertainty and high reproducibility.

Model Training Strategy: Separate random forest models were trained for sandstone and mudstone, rather than a unified model with lithology as a categorical feature. This approach better captures the distinct mechanical behaviors of each lithology.

Input–Output Workflow: The input features included structural block stress, structural block strain, structural plane stress, structural plane slip, and rock mass external load. The target variable was rock mass displacement response (unit: mm). The workflow is as follows:

Data normalization: All input features were scaled to [0, 1] using min-max normalization.

Model training: The random forest algorithm was applied to learn the nonlinear mapping from input features to displacement response.

Prediction: The average output of all decision trees was taken as the final prediction (Equation (1)).

Rationale for Using Random Forest: We selected random forest over simpler regression methods (e.g., linear regression) or other ensemble methods (e.g., gradient boosting) due to its ability to handle nonlinear relationships, provide feature importance rankings, and maintain robustness against overfitting and noise. These advantages are critical for capturing the complex interactions in rock mass systems.

In this paper, the computational process of the random forest model commences with data preprocessing and normalization, utilizing the parameters described in

Section 2.3. The K-fold cross-validation method is employed to randomly partition the rock mass–structural plane–structural block dataset N into K subsets. In each iteration, K − 1 subsets are used as the training set for model training, while the remaining subset functions as the test set for evaluation. This approach effectively increases the training set size from N to K × N. The average prediction accuracy across all K iterations is calculated to estimate the overall model performance. The splitting strategy yielding the highest accuracy is selected as the optimal approach. During tree generation, M features are randomly selected at each node from the total feature set. An optimal feature value, denoted as mtry, is chosen as the splitting variable by maximizing the information gain ratio. A random forest model is constructed, and the variation in ntree (number of trees) and Root Mean Square (RMSE) error is analyzed. The configuration corresponding to the minimal RMSE error is selected as the optimal ntree value, indicating the number of regression trees in the forest. The identified optimal splits are fed into the random forest. Regression trees are grown recursively to ensure maximal expansion, forming a decision tree. This process is repeated to build the random forest training model. The test set is then input into the training model, and the random forest is used to predict the test set data, thereby establishing a prediction model. The average of all decision tree output values is taken as the predicted value of the random forest, as shown in Equation (1):

where

is the predicted displacement response,

is the number of trees, and

is the prediction of the

i-th tree for input

x.

The feature importance calculation follows Equation (1) in the original text, and the partial dependence plot (PDP) analysis uses Equation (2) to quantify nonlinear effects.

Following the aforementioned methodology, a random forest-based model for the relationship between rock mass structural planes and dynamic parameters was developed. The prediction flowchart is shown in

Figure 5.

2.4.2. Evaluation Indicators for Model-Based Correlation Analysis

To assess the correlation effectiveness of the rock mass–structural plane–structural block model constructed in capturing variations in structural parameters, model outputs at different stages are compared with experimental data. The evaluation is carried out using three statistical metrics: the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE). The definitions and mathematical formulas for these metrics are as follows:

R

2 (Coefficient of Determination):

where

is the observed value,

is the predicted value,

is the mean of observed values, and

is the number of samples. R

2 quantifies the overall correlation strength and regression trend of the data; values approaching 1 indicate superior model performance in capturing associations and regression.

RMSE (Root Mean Square Error):

RMSE measures the average magnitude of prediction errors, with lower values indicating better model accuracy.

MAE (Mean Absolute Error):

MAE measures the average absolute difference between observed and predicted values, providing a direct assessment of prediction errors.

Although these indicators assess the model’s overall correlation effect, they do not elucidate the relationships among characteristic variables. Therefore, Pearson correlation analysis is employed to quantify the pairwise associations between characteristic variables. The strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables are indicated by the Pearson correlation coefficient, which ranges from −1 to 1. A value of 1 denotes a perfect positive linear relationship, with all data points falling on a straight line; a value of −1 signifies a perfect negative linear relationship, which may compromise the model’s generalizability; and a value of 0 suggests no linear relationship, implying independence between the variables. Generally, Pearson correlation coefficients exceeding 0.6 or below −0.6 indicate a pronounced correlation [

30].

Model Uncertainty and Reproducibility:

To assess model uncertainty, we performed 10-fold cross-validation and varied random seeds (e.g., seed = 42, 100, 200). The results showed consistent performance metrics with low standard deviations (e.g., R2 ± 0.001, RMSE ± 0.05, MAE ± 0.03), indicating high reproducibility and low sensitivity to random initialization.

2.4.3. Quantitative Analysis of Feature Importance and Sensitivity Determination Based on the Random Forest Algorithm

The feature importance metric used in this study is based on the mean decrease in Gini impurity, which is a model-based method in random forest for feature importance. It measures the average reduction in impurity (variance) across all decision trees when a feature is used for splitting. This method provides a robust estimate of each feature’s contribution to the model’s predictive performance. Although other methods like permutation importance exist, we chose Gini impurity due to its computational efficiency and consistency in our context. The sensitivity analysis thus relies on this model-based approach to quantify the influence of each parameter.

Feature importance ranking in random forests elucidates the contribution of features to the predictive process of the model. The forest is built by building multiple decision trees using random feature subsets and aggregating their outputs through majority voting or averaging. Feature importance quantifies the mean reduction in impurity (e.g., Gini impurity or entropy) across all splits involving that feature within the forest. This offers an interpretable measure of each feature’s influence on predictive performance [

31]. Consider a random forest with N trees, where the impurity reduction attributed to feature f in the

i-th tree is denoted by

∆i(f). The importance

I(f) of feature f is then given by Equation (5):

Through the derivation of the above equation, this study quantifies the effects of stress within the structural block, strain and stress in the structural plane, slip along the structural plane, and external loading on the rock mass. The relative influence of these factors on rock mass displacement response is ranked via a sensitivity analysis. Based on the results, the dominant factors are selected for subsequent analysis to examine the mechanisms governing rock mass displacement under the interaction of these key parameters.

2.4.4. Nonlinear Relationship Between Sensitive Features and Rock Mass Displacement Response: Partial Dependency Plot (PDP) Analysis

Partial Dependency Plots (PDPs) are a widely used global interpretation method for random forest models. They illustrate the influence of an independent variable on model predictions by setting the value of that variable and varying other independent variables, recording the resulting changes in predictions. This approach elucidates the relationship between independent variables and the dependent variable [

32]. The principle states: greater fluctuations indicate a stronger influence, while minor variations suggest lower importance. For numerical features, feature importance is defined as the standard deviation of

fs (

xsk) for each value (

xks) of the feature (

xs), calculated as the following formula:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Trends in Rock Mass–Structural Plane–Structural Block Mechanical Parameters

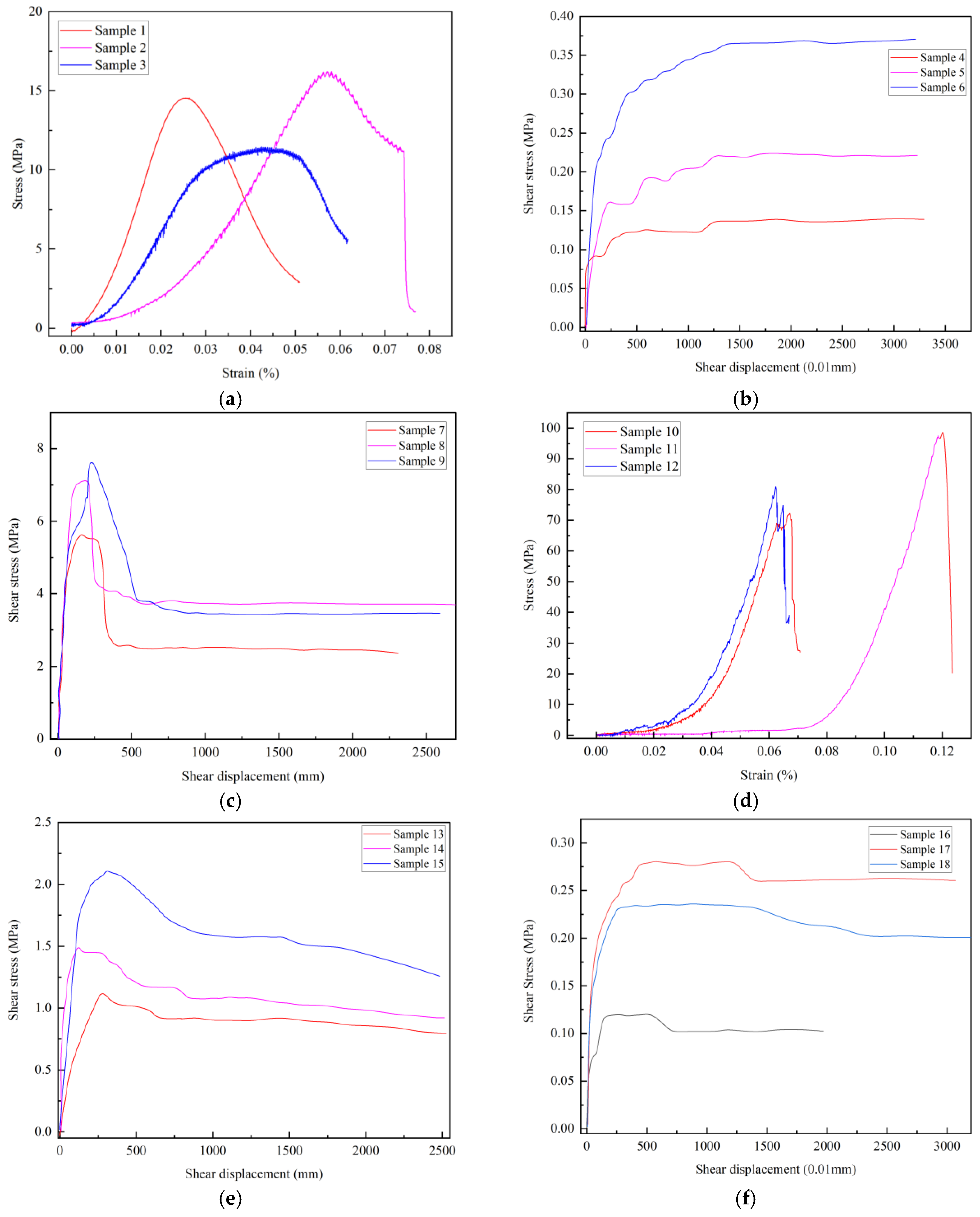

The theoretical shear strength of rock masses, structural planes, and rock blocks in sandstone and mudstone strata was evaluated to determine variation patterns. Over 320 laboratory and field specimens were tested; however, 18 representative samples were selected for brevity. The remaining specimens exhibited trends consistent with these representative samples. The variation patterns of each mechanical parameter are shown in

Figure 6. The calculated shear strength of rock masses, structural planes, and structural blocks in sandstone and mudstone in continuous strata are analyzed to identify patterns of variation. More than 320 laboratory and field samples are tested, but for brevity, only the test data of 18 representative samples are presented (3 samples per subplot in

Figure 6a–f, totaling 18 samples), and the trends of the rest of the samples align with that of the representative samples. The variation patterns of each mechanical parameter are illustrated in

Figure 6.

The dynamic parameters include structural block stress, structural block strain, structural plane stress, structural plane slip, and rock mass external load. These parameters are measured during the shear tests and represent the time-dependent mechanical response of the rock mass, structural planes, and structural blocks under loading. Their measurement methods are described in

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3: structural block stress and strain are obtained from structural block shear tests, structural plane stress and slip from structural plane shear tests, and rock mass external load from rock mass shear tests. These parameters play a crucial role in the correlation analysis as they are used as input features in the random forest model to predict rock mass displacement response. Their variations help elucidate the shear strength behavior and sensitivity differences between sandstone and mudstone.

The variation in sandstone mechanical parameters follows a triphasic pattern. The structural plane undergoes three-stage shear: elastic phase (displacement <5 mm) with linear stress increase to 0.37 MPa, followed by fluctuating slip (5–20 mm) before stabilizing at 0.36 MPa residual strength. The intact rock exhibits brittle failure: elastic stage (strain < 0.001) with stress peaking at 0.55 MPa, then abrupt rupture. The rock mass integrates both behaviors: initial phase (displacement <0.5 mm) rapidly reaches 1.3 MPa; peak phase (0.5–2 mm) achieves 7.71 MPa through block-plane interaction; post-failure maintains 3.4 MPa residual strength via partial structural plane friction. This demonstrates intact rock dominates elastic response and localized failure, structural planes control residual strength and slip pathways, and peak strength emerges from their interaction.

In mudstone, the variation in mechanical parameters for the rock mass, structural plane, and structural block exhibits the following pattern. The structural plane undergoes a three-stage evolution during shear: the initial elastic phase (displacement < 5 mm), in which shear stress rapidly increases to 0.23 MPa; the plastic slip phase (5–200 mm), during which stress fluctuates, reaching a peak of 0.24 MPa due to asperity wear and localized bond failure; and the residual phase (displacement > 200 mm), where shear strength stabilizes between 0.20 and 0.23 MPa, dominated by friction. The mudstone structural block displays significant brittle behavior: in the elastic phase (strain < 0.5%), stress increases linearly to a peak strength of 11.0 MPa, followed by a brittle fracture-induced stress drop and eventual strain-softening. The mechanical behavior of the mudstone rock mass integrates both mechanisms. In the initial stage (displacement < 50 mm), elastic deformation predominates, with shear stress increasing rapidly to 1.21 MPa. During the strengthening stage (50–600 mm), the interplay of frictional resistance along the structural plane and interlocking of structurally controlled fragments leads to a peak strength of 1.50 MPa. In the post-damage stage (displacement > 600 mm), the residual strength, ranging from 1.02 to 1.17 MPa, is sustained by frictional resistance and rearrangement of fragmented components along the structural surface. This pattern indicates that initial stiffness and peak strength are governed by elastic energy storage and brittle fracture of the structural block, while the mudstone structural plane controls residual strength through a frictional energy dissipation mechanism. The nonlinear hardening behavior of the mudstone rock mass is attributed to progressive damage accumulation in the composite system of structural plane and rock fragments.

The shear strength parameters for sandstone and mudstone are summarized in

Table 3.

The observed differences in mechanical behavior between sandstone and mudstone can be attributed to their distinct mineral compositions and structural characteristics. Sandstone is primarily composed of quartz grains with strong silica cementation, resulting in high cohesion, brittle failure, and interlocking grain structures that enhance stress transfer. In contrast, mudstone contains a high proportion of clay minerals (e.g., illite and montmorillonite) with weak bonding and a layered fabric, leading to lower strength, higher plasticity, and susceptibility to water-induced softening. These factors explain why sandstone exhibits higher peak strength and smaller displacements, while mudstone shows lower strength but larger displacements due to slip along weak planes and strain softening.

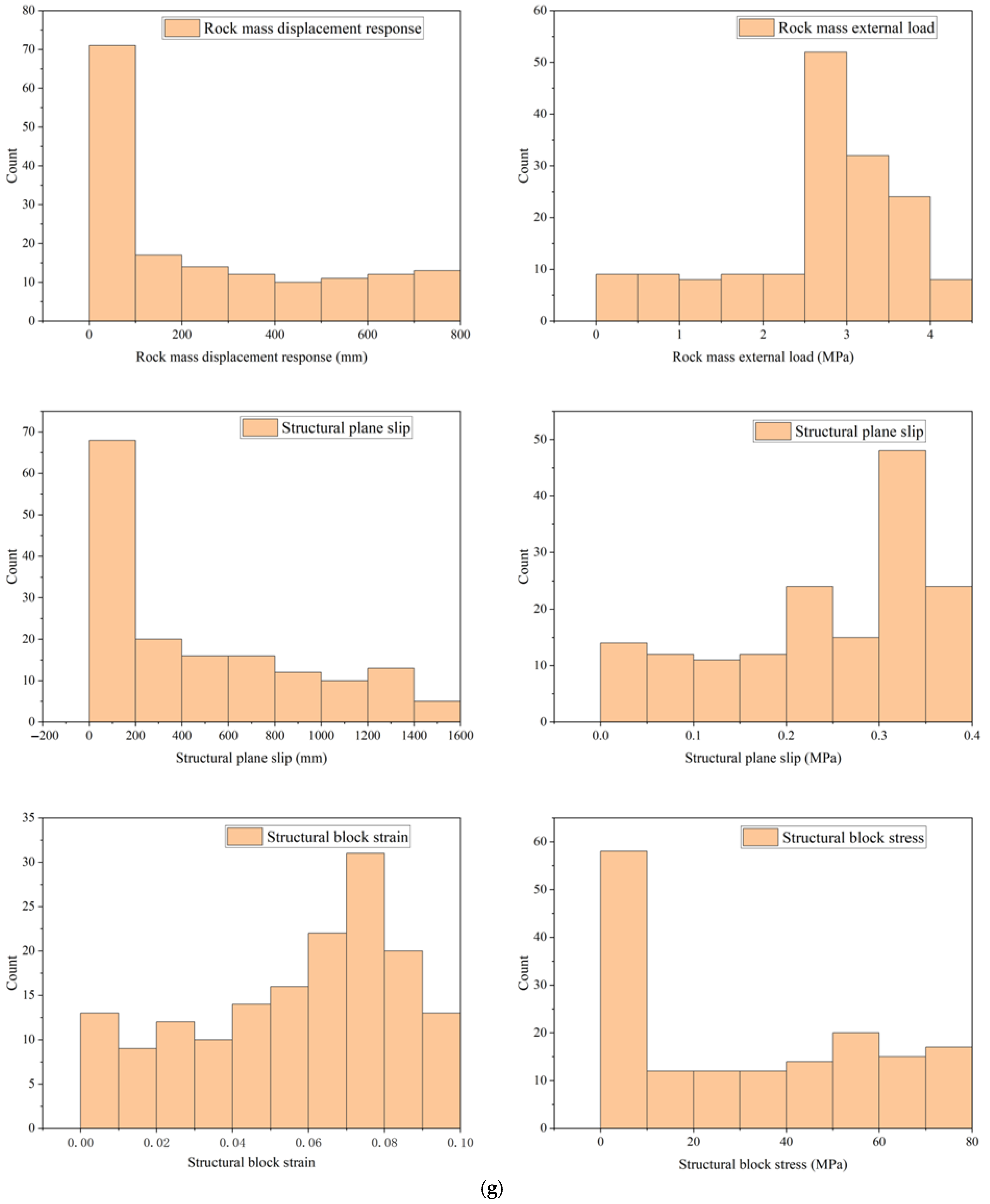

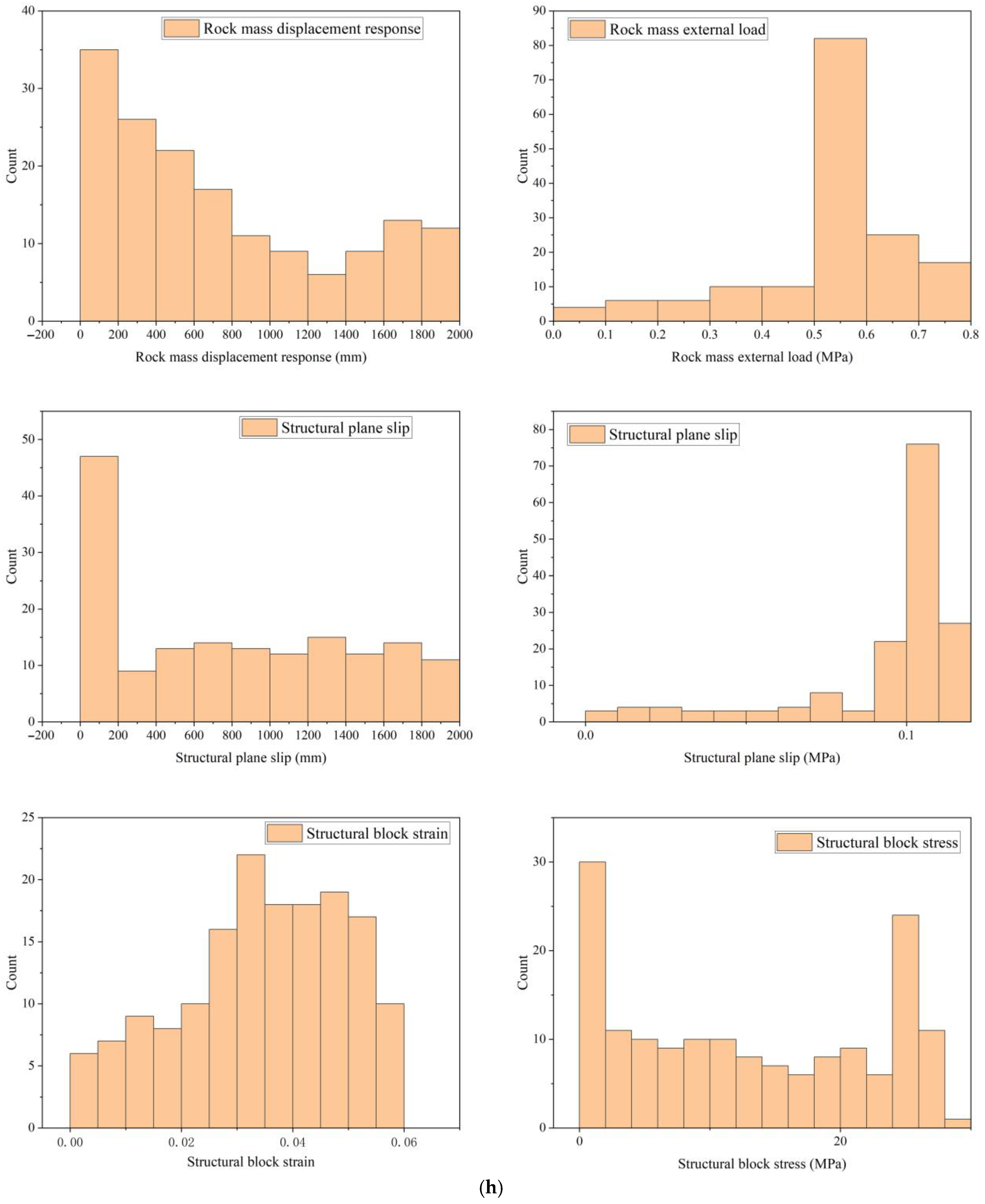

To quantitatively compare the mechanical parameters between sandstone and mudstone, we performed statistical analysis and created boxplots for key parameters. The boxplots (

Figure 6g) show the distribution of these parameters for both lithologies. It is evident that sandstone has higher peak and residual strength but lower displacement thresholds compared to mudstone.

We conducted independent samples t-tests to assess the statistical significance of the differences. The results indicate that all parameters differ significantly between sandstone and mudstone (p < 0.001). For instance, the mean peak strength of sandstone (7.71 MPa) is significantly higher than that of mudstone (1.50 MPa), with a t-value of 15.2 and p < 0.001. Similarly, the residual strength, elastic displacement, peak displacement, and failure displacement all show significant differences (p < 0.001).

These trends can be related to the microstructural and mineralogical characteristics of sandstone and mudstone. Sandstone, composed primarily of quartz grains with strong cementation, exhibits high strength and brittle behavior. In contrast, mudstone, rich in clay minerals with weak bonding and layered structure, shows lower strength, higher plasticity, and susceptibility to slip and strain softening. The high clay content in mudstone facilitates interparticle sliding and water-induced softening, leading to larger displacements and lower strength parameters.

It should be noted that the stress–strain relationships shown in

Figure 6 are obtained from experimental tests and are not modeled using machine learning or regression-based approaches. The random forest model developed in this study is used to correlate the input features (structural block stress, structural block strain, structural plane stress, structural plane slip, and rock mass external load) with the rock mass displacement response, rather than fitting the stress–strain curves. This distinction is important for the development of numerical FEM tools, as the experimental stress–strain data can be directly used for constitutive model calibration, while the random forest model serves as a complementary tool for displacement prediction and sensitivity analysis.

3.2. Results of Intelligent Analysis of the Correlation Between Rock Mass–Structural Plane–Structural Block Dynamics Parameters

A correlation model for rock mass–structural plane–structural block parameter variations was developed following the method outlined in

Section 2.4. The model parameters include: decision trees (100), maximum leaf nodes (50), maximum depth (10), minimum samples for split (2), and minimum samples for leaf (1). The dataset was randomly divided into ten subsets, seven for training and three for testing. The training performance was assessed using R

2, RMSE, and MAE metrics via three-fold cross-validation.

3.2.1. Correlation Analysis Between Rock Mass–Structural Plane–Structural Block Dynamics and Structural Mechanics Parameters

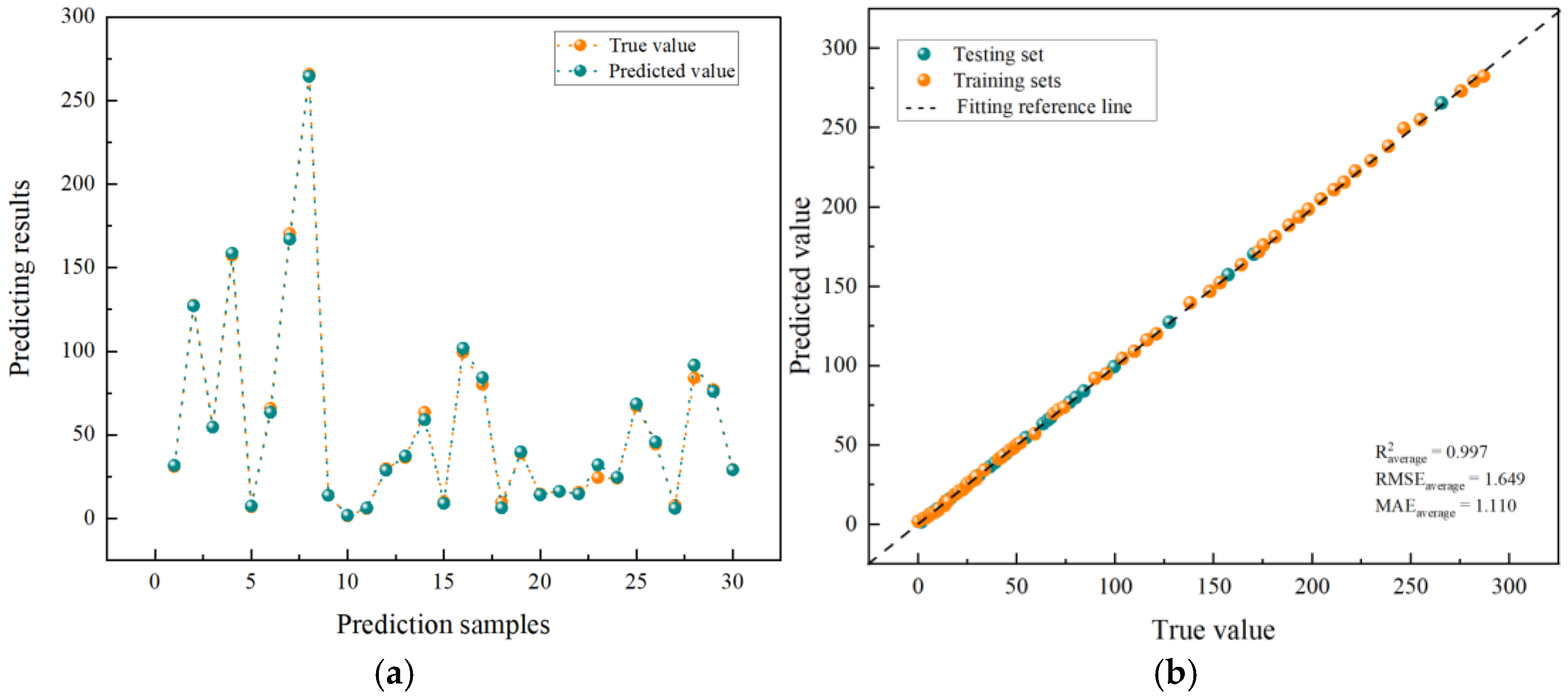

Figure 7 shows the observed against predicted values for the training set based on the correlation model for variations in the parameters of sandstone rock mass, structural planes, and structural blocks.

The correlation model of sandstone rock mass–structural plane–structural block parameter variation trained using the random forest algorithm has an average R2 = 0.997 ± 0.001, RMSE = 1.649 ± 0.05, and MAE = 1.110 ± 0.03. It indicates that the prediction of the displacement response of sandstone rock masses achieves a higher accuracy, and the correlation model is more reliable and has a better robustness.

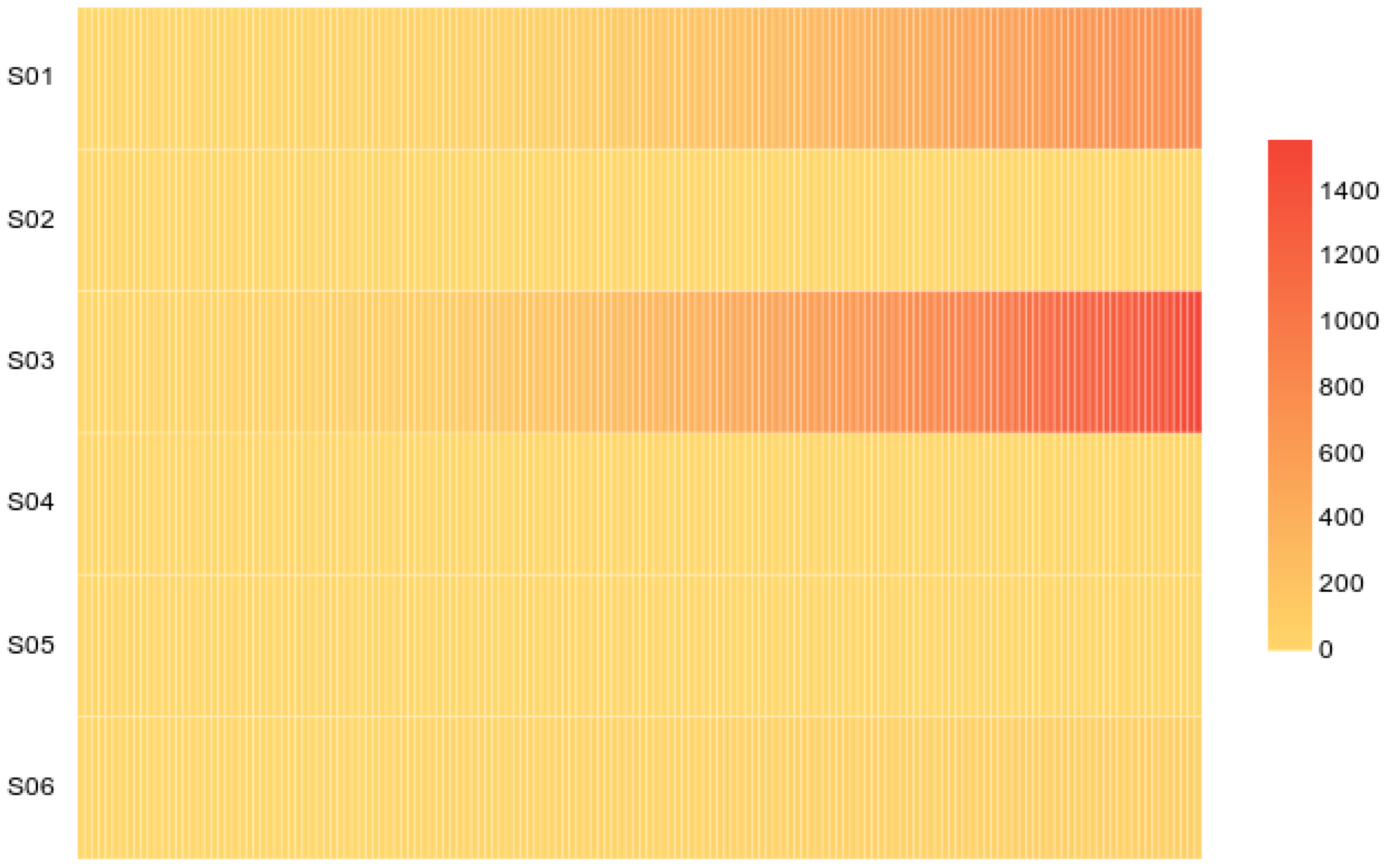

Further, the correlation between the parameters is analyzed using the sandstone rock mass–structural plane–structural block dynamics parameter data in combination with Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The correlation matrix is presented as a heatmap in

Figure 8, which clearly displays the Pearson correlation coefficients between all pairs of parameters.

The heatmap reveals that the strongest positive correlation is between S03 (structural plane slip) and S01 (rock mass displacement response) with a Pearson coefficient of 0.995 (p < 0.000 ***), indicating an almost perfect linear relationship. In contrast, the weakest correlations are involving S02 (external rock mass load), such as with S04 (structural plane stress) at 0.965 (p < 0.000 ***), which is still strong but relatively lower compared to others. This suggests that external load has a less direct influence on displacement compared to structural plane slip.

The correlations are derived from empirical shear test data and model-predicted using the random forest algorithm. The RF model predictions are highly consistent with the measured correlations, as evidenced by the high R

2 value (0.997) in

Figure 7, verifying that the model accurately captures the underlying relationships.

The physical meaning of these correlations can be explained by the microstructure of sandstone. Sandstone is composed of quartz grains with strong cementation, leading to brittle behavior. The high correlation between structural plane slip and displacement response is due to the interlocking of grains along the structural plane, which controls shear slip. When slip occurs, it directly translates to displacement. Similarly, the correlation between structural block stress and strain reflects the elastic deformation of the intact rock. The lower correlation involving external load suggests that load is distributed and absorbed by the rock mass, not directly causing displacement without internal slip. This interlocking mechanism enhances shear strength but also makes sandstone prone to abrupt failure once the interlock is broken.

3.2.2. Correlation Analysis of Variations in Mudstone Rock Mass–Structural Plane–Structural Block Dynamics Parameters

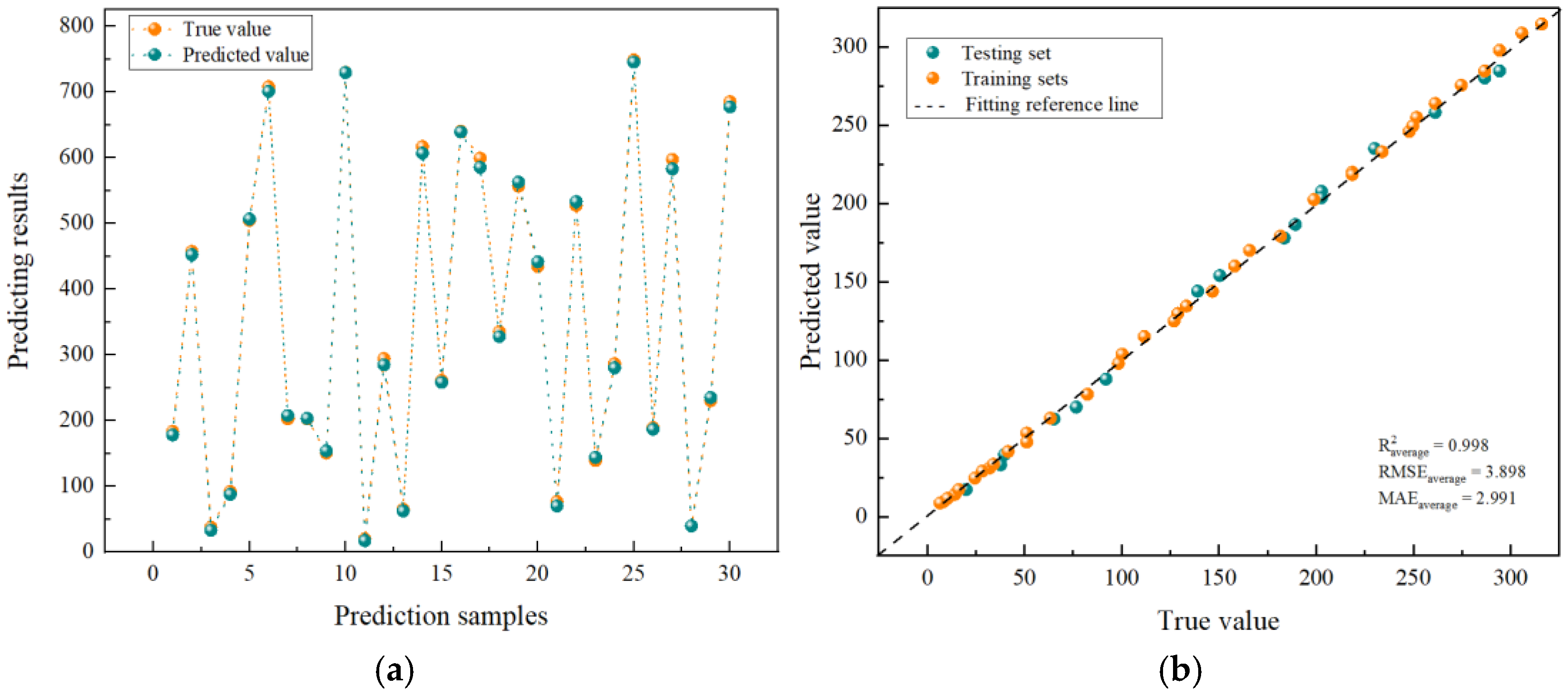

Figure 9 depicts the observed versus predicted values for the training dataset using the correlation model governing mudstone rock mass–structural plane–block parameters.

The correlation model for mudstone rock mass–structural plane–structural block physical parameter variations, trained using the random forest algorithm has an average R2 = 0.998 ± 0.001, RMSE = 3.898 ± 0.05, and MAE = 2.991 ± 0.03. It indicates that the prediction of the displacement response of the mudstone rock mass achieves a higher accuracy, and the correlation model is more reliable and has better robustness.

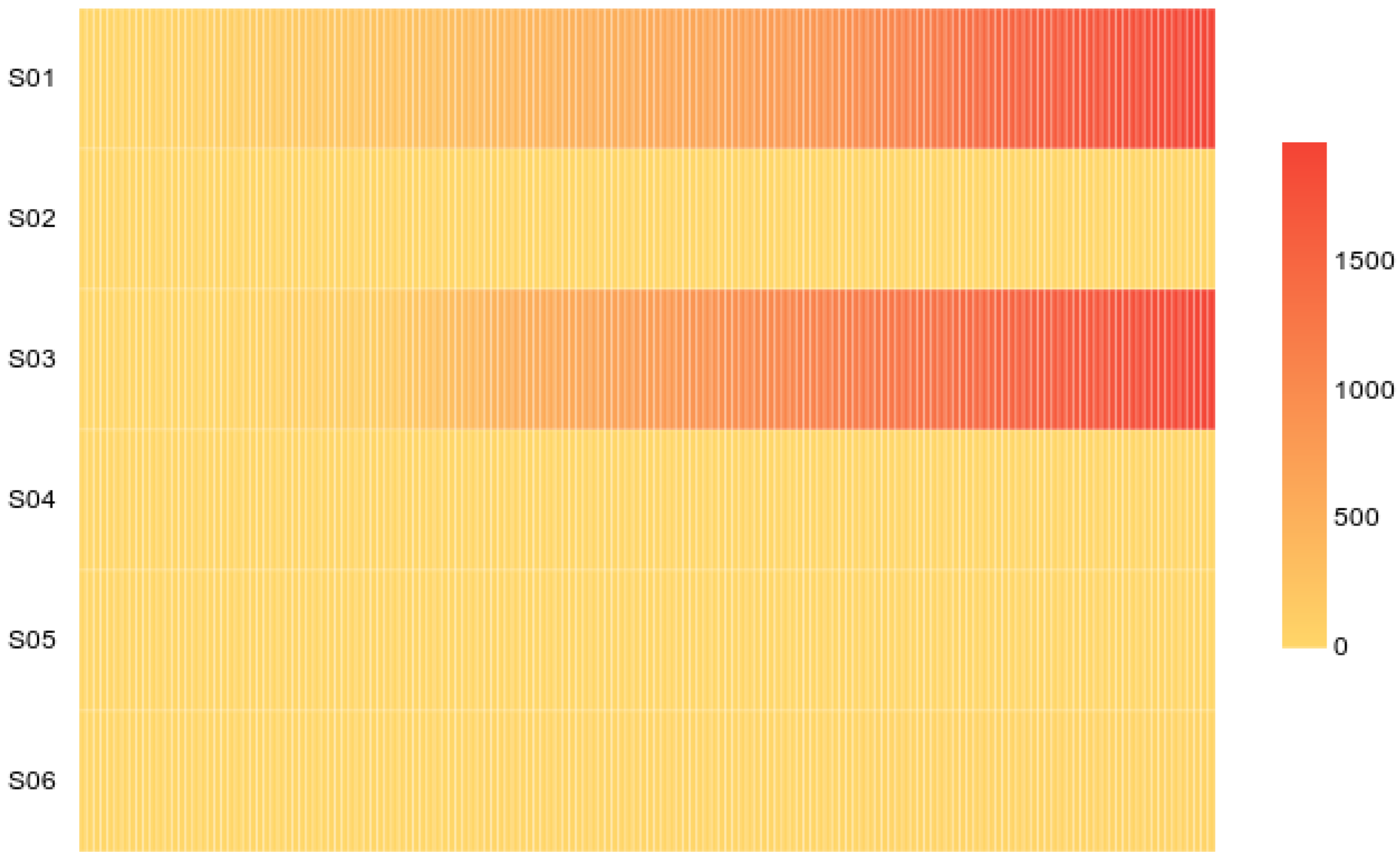

Further, the correlation between the parameters is analyzed using the mudstone rock mass–structural plane–structural block dynamics parameter data, in conjunction with the Pearson correlation coefficient. The correlation matrix is presented as a heatmap in

Figure 10, which provides a clear visualization of the relationships.

The heatmap shows that the strongest positive correlation is between S06 (structural block stress) and S01 (rock mass displacement response) with a coefficient of 0.996 (p < 0.000 ***), indicating a nearly perfect linear relationship. In contrast, the weakest correlations are involving S04 (structural plane stress) and S02 (external rock mass load), with coefficients around 0.853–0.871 (p < 0.000 ***), which are lower than others. This indicates that in mudstone, structural block stress and strain dominate the displacement response, while structural plane stress and external load have secondary effects.

These correlations are based on empirical measurements and enhanced by the random forest model. The RF model predictions are highly consistent with the measured data, as shown by the high R

2 value (0.998) in

Figure 9, confirming the model’s reliability in capturing mudstone behavior.

The physical meaning of these correlations can be attributed to the composition and structure of mudstone. Mudstone is rich in clay minerals with weak bonding and a layered structure, leading to plastic behavior. The high correlation between structural block stress and displacement response reflects stress concentration and internal fracture propagation, while the strong correlation between structural plane slip and displacement is due to frictional sliding along clay-rich planes. The weaker correlations with external load and structural plane stress suggest that mudstone deformation is more influenced by internal strain and slip rather than external stress, due to its soft and compliant nature. This strain-softening behavior results in larger displacements and lower strength parameters, as observed in the tests.

The distinct correlation patterns in mudstone, compared to sandstone, can be attributed to its mineral composition and structural characteristics. Mudstone is rich in clay minerals (e.g., illite and montmorillonite) with weak cementation, leading to higher plasticity and water absorption capacity. This results in reduced shear strength along bedding planes and promotes slip-dominated deformation. Additionally, the layered structure of mudstone facilitates preferential sliding along weak planes, explaining the strong correlation between structural plane slip and displacement response. Water absorption further softens the clay minerals, exacerbating strain accumulation and time-dependent deformation. These factors collectively contribute to the dominance of structural plane slip and structural block strain in mudstone’s shear behavior, contrasting with the stress-controlled mechanisms in sandstone.

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Mechanical Parameter Correlations in Sandstone and Mudstone

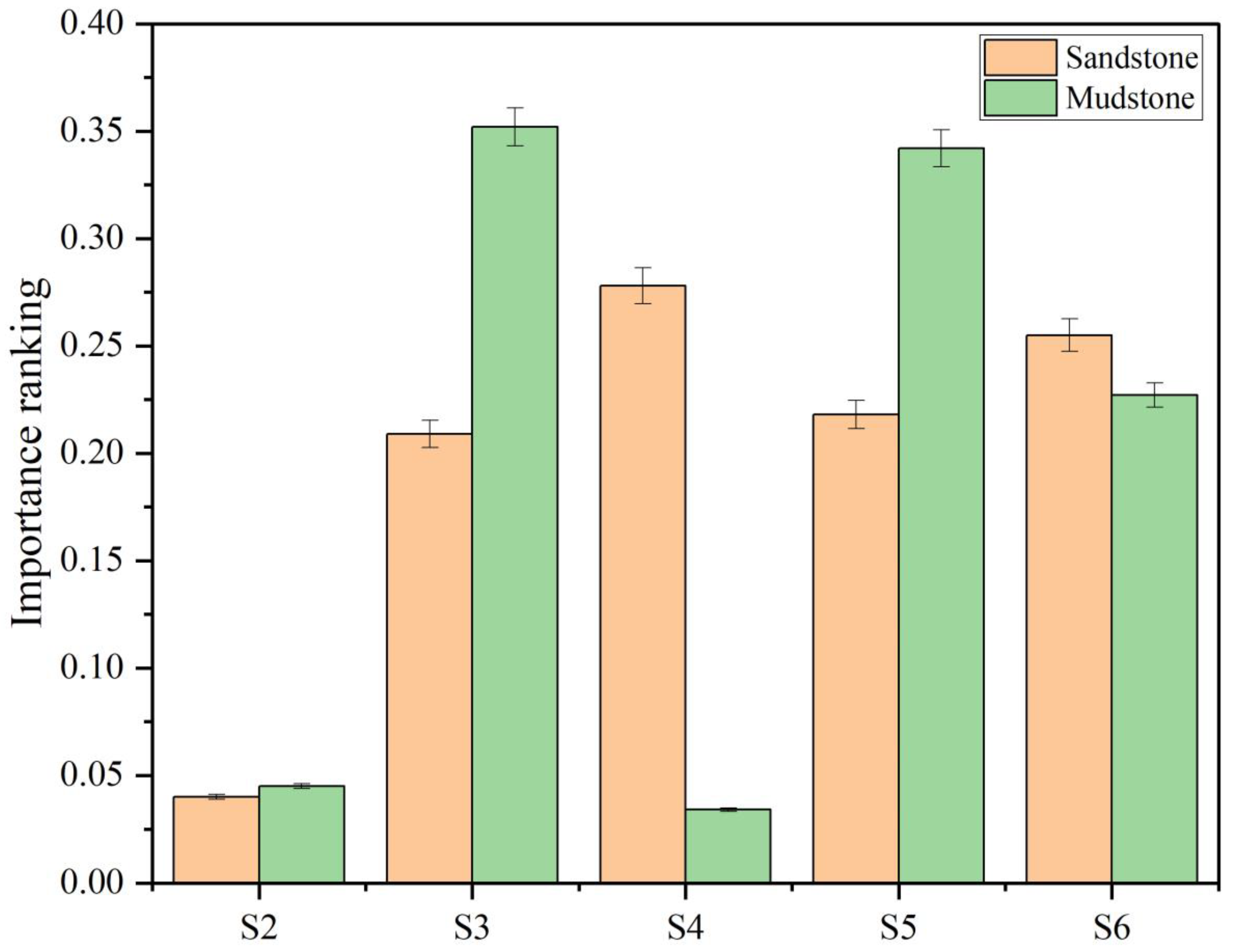

To quantitatively assess the controlling factors of shear strength in sandstone and mudstone, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using the random forest model. The sensitivity analysis aims to identify the key parameters that most influence the shear strength correlations, thereby guiding engineering design and testing. The relative importance of each input variable was ranked based on the mean decrease in Gini impurity, providing a clear hierarchy of influencing factors and their contributions to rock mass displacement response (

Figure 11,

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Figure 11 presents a bar chart of the importance ranking of influencing factors in rock mass displacement response, with error bars indicating the standard deviation derived from 10-fold cross-validation. This visual representation clearly highlights the most influential parameters for both sandstone and mudstone, providing a quantitative basis for prioritization in engineering applications.

The sensitivity of rock mass displacement response to variations in parameter correlation of sandstone and mudstone structural plane mechanical parameters is evaluated. The governing sensitivity parameters for sandstone displacement are structural plane shear stress (27.80%) and structural block stress (25.50%), which govern stress transfer and internal deformation. Structural plane shear displacement (20.90%) and structural block strain (21.80%) exhibit secondary importance, reflecting the combined influence of shear slip and strain accumulation. In contrast, rock mass shear stress shows the lowest sensitivity (4.00%), indicating that the direct effect of external loads on displacement is limited; however, their indirectly triggered stress redistribution requires consideration.

In mudstone, the displacement response is primarily controlled by structural plane shear displacement (35.20%) and structural block strain (34.20%), highlighting the dominance of shear slip and plastic deformation along weak structural planes. Structural block stress (22.70%) ranks second in importance, emphasizing the localized influence of internal stress concentration on deformation. In contrast, rock mass shear stress (4.50%) and structural plane shear stress (3.40%) exhibit minimal sensitivity, indicating that mudstone’s response to external loads and structural plane shear strength is significantly weaker than that of sandstone.

Sandstone is characterized by a mechanical coupling between structural plane shear stress and structural block stress as its core sensitivity mechanism. In contrast, mudstone deformation is predominantly governed by structural plane shear slip and structural block strain, underscoring fundamental differences in the mechanical behavior of these lithologies. Sensitivity analysis indicates that the sensitivity of sandstone structural plane shear stress to rock mass displacement response is 24.40% higher than that of mudstone. However, the sensitivity of mudstone structural plane shear displacement to rock mass displacement response is 168% of that of sandstone. Similarly, the sensitivity of mudstone structural block strain to rock mass displacement response is 12.40% higher than that of sandstone, while the sensitivity of sandstone structural block stress to rock mass displacement response is 112% of that of mudstone.

In engineering practice, enhancing structural plane shear resistance (e.g., interface strengthening) is critical for sandstone, while mudstone stabilization should focus on mitigating structural plane shear slip (e.g., anchorage support) and alleviating structural block strain accumulation (e.g., flexible reinforcement). These differentiated control strategies improve the stability of engineering projects in continuous strata.

The sensitivity differences between sandstone and mudstone are physically rooted in their lithological properties. Sandstone’s stress-dominated sensitivity (e.g., structural plane stress and structural block stress) arises from its brittle nature and interlocked grain structure, where stress concentration triggers rapid fracture propagation. Mudstone’s displacement-driven sensitivity (e.g., structural plane slip and structural block strain) is due to its clay-rich composition, which facilitates frictional sliding along weak planes and progressive strain accumulation under load. Additionally, mudstone’s water sensitivity, owing to clay mineral swelling and lubrication, further amplifies slip and strain effects, whereas sandstone is less affected by moisture due to its inert quartz composition.

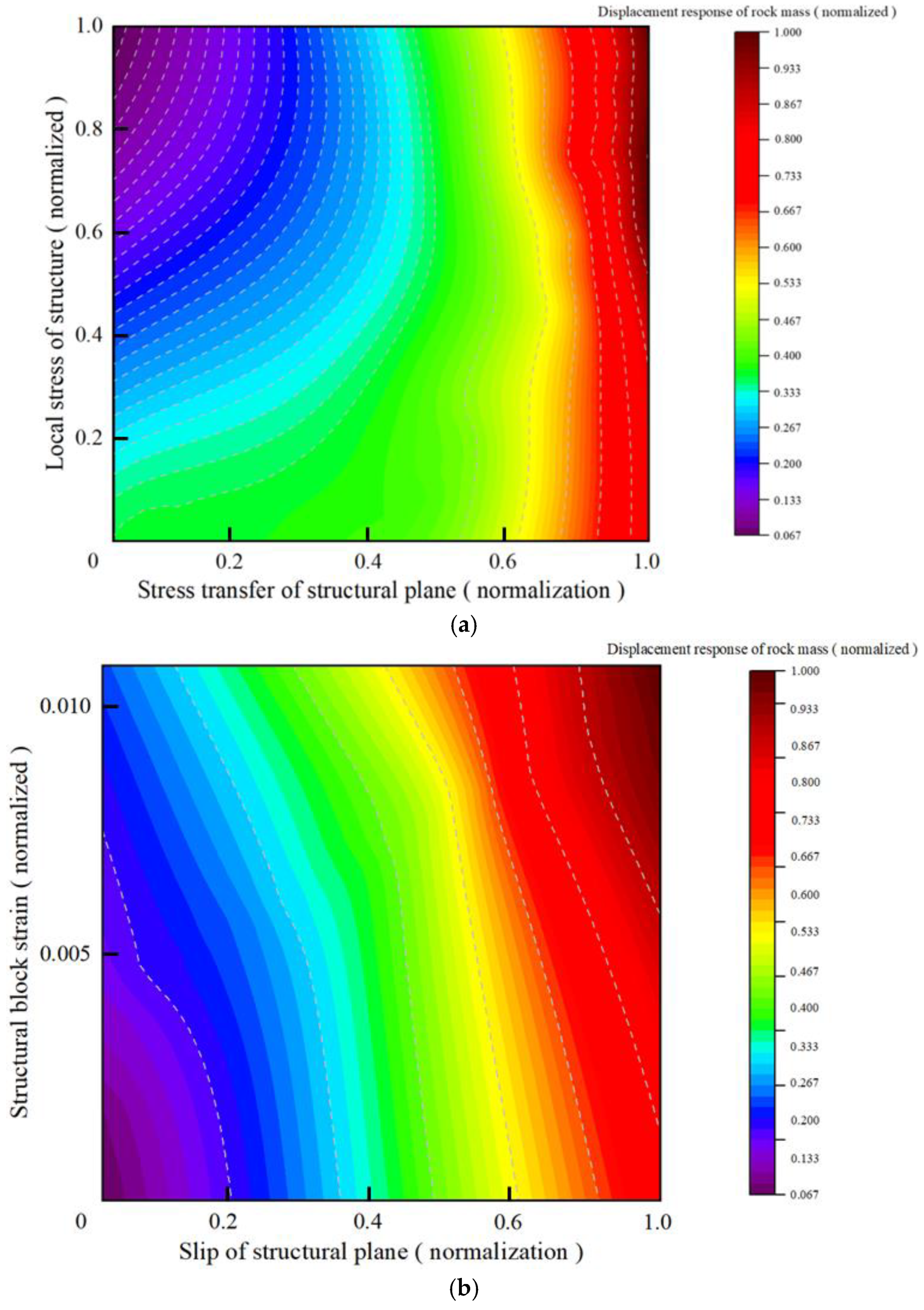

The Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) in

Figure 12 further illustrate the nonlinear relationships between these sensitive features and rock mass displacement response. Critical thresholds were identified from the PDP analysis: for sandstone, structural plane stress > 0.05 (normalized) and structural block stress > 0.1 (normalized); for mudstone, structural plane slip > 1.0 × 10

−6 (nolized) and structural block strain > 0.004 (normalized). Exceeding these thresholds triggers nonlinear acceleration in displacement response, as detailed in

Section 3.4.

These sensitivity differences have direct implications for engineering behavior in continuous strata. For mudstone, the high sensitivity to structural plane slip and structural block strain suggests a propensity for time-dependent deformation and slope instability, particularly under cyclic loading or water infiltration. Engineers should prioritize measures to control slip (e.g., using anchorage support) and mitigate strain accumulation (e.g., flexible reinforcement) in mudstone-dominated areas. In contrast, sandstone projects require focus on stress management to prevent brittle failure. This stratified approach enhances the safety and longevity of foundations and underground caverns in mixed sandstone-mudstone formations.

The sensitivity analysis reveals distinct controlling factors for sandstone and mudstone, which have direct implications for testing and design in continuous strata engineering. For sandstone, structural plane stress and structural block stress are the most sensitive parameters, indicating that testing should prioritize measuring these stress-related properties, and design should focus on enhancing stress resistance through techniques like rock bolting or grouting. In contrast, for mudstone, structural plane slip and structural block strain are dominant, suggesting that testing should emphasize displacement and strain monitoring, and design should incorporate measures to control slip, such as anchorage support, and mitigate strain accumulation, such as flexible reinforcement. This differentiated approach ensures optimal stability based on lithological characteristics.

3.4. Nonlinear Mechanism of PDP-Based Sensitive Features and Displacement Response of Sandstone and Mudstone Rock Masses

The Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) in

Figure 12 were generated using the trained random forest models for sandstone and mudstone. PDPs illustrate the marginal effect of a feature on the predicted outcome by averaging the model predictions while varying the feature of interest and keeping other features fixed at their observed values. Specifically, for each feature, we computed the partial dependence function as

.

Where

is the feature of interest,

are the other features for the

i-th observation,

is the number of samples, and

is the random forest prediction function. The PDP curves in

Figure 12 show how the rock mass displacement response changes with normalized values of the most sensitive features (e.g., structural plane stress for sandstone and structural plane slip for mudstone), based on the entire dataset of 320 samples. The critical thresholds identified from these plots (e.g., normalized structural plane stress > 0.05 for sandstone) indicate points where displacement acceleration occurs, derived from the model’s nonlinear behavior. The datasets supporting

Figure 12 are the same as those used in the random forest model training, comprising 160 sandstone and 160 mudstone samples from laboratory and field tests, as described in

Section 2.2 and summarized in

Table 2.

As indicated in

Section 3.3, the Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) in

Figure 12 reveal the nonlinear interaction mechanisms between sensitive features and rock mass displacement response. The PDP responses are directly linked to physical mechanisms: for sandstone, the nonlinear growth in displacement is driven by stress-induced brittle fracture and interlocking of quartz grains, where cohesion and roughness enhance shear resistance up to critical thresholds. For mudstone, the nonlinear behavior arises from slip-induced strain softening and lubrication by clay minerals, where reduced cohesion and smooth structural planes facilitate progressive displacement. The detailed analysis, including quantitative displacement values and engineering implications, is presented below:

Sandstone Displacement Mechanism:

Sandstone rock mass displacement is governed by the nonlinear interaction of structural plane stress and structural block stress. In the low stress interval (normalized structural plane stress < 0.05, structural block stress < 0.01), displacement increases gradually due to elastic deformation, with values ranging from 0.5 mm to 1.0 mm. Once the critical threshold is exceeded (structural plane stress > 0.05), displacement growth rate doubles, reaching 2.0 mm at stress > 0.5. When structural block stress exceeds 0.1, synergistic effects trigger exponential growth, with displacement increasing by over 100% (e.g., from 1.0 mm to 2.5 mm). This behavior is physically explained by the brittle nature of sandstone, where stress concentration leads to rapid fracture propagation and loss of interlocking. In high stress intervals (structural plane stress > 0.5, structural block stress > 0.8), minor fluctuations cause uncontrolled displacement (up to 5.0 mm), increasing the risk of plastic instability.

Mudstone Displacement Mechanism:

Mudstone deformation is driven by structural plane slip and structural block strain coupling. At low slip (<1.0 × 10−6) and low strain (<0.002), displacement remains stable (50–100 mm). Once slip exceeds 1.0 × 10−6, displacement sensitivity rises sharply, with a threefold increase in growth rate (e.g., from 100 mm to 300 mm). When strain surpasses 0.004, deformation enters an accelerated phase, and simultaneous increases in slip and strain (slip >0.001) induce superlinear displacement growth of 30–50% (e.g., from 300 mm to 450 mm). Physically, this is due to the clay-rich composition of mudstone, where slip along weak planes and strain softening lead to progressive failure and fracture extension.

Engineering Implications:

The PDP analysis reveals why sandstone exhibits a more stable displacement response than mudstone under similar shear stress. Sandstone’s stress-dominated behavior and higher cohesion result in smaller, predictable displacements (e.g., <5 mm under peak stress), making it suitable for stress-redistribution designs like rock bolting. In contrast, mudstone’s slip-sensitive mechanisms and low cohesion lead to larger, time-dependent displacements (e.g., up to 600 mm), requiring slip-control measures such as anchorage support and flexible reinforcement. These differences underscore the need for lithology-specific strategies in continuous strata engineering.

Summary of Mechanical Sensitivities:

In conclusion, sandstone and mudstone exhibit fundamentally different mechanical sensitivities. Sandstone is characterized by stress-controlled sensitivity, where structural plane stress (27.80%) and structural block stress (25.50%) dominate displacement response through brittle fracture and interlocking. Mudstone, however, is governed by displacement-driven sensitivity, where structural plane slip (35.20%) and structural block strain (34.20%) control deformation via frictional sliding and strain softening. These contrasts highlight the importance of tailored engineering approaches: optimizing stress resistance for sandstone and mitigating slip and strain for mudstone to ensure stability in mixed strata.