Abstract

The widespread production and application of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) have created a global environmental and public health crisis. This review aimed to consolidate the foundational knowledge on PFASs by synthesizing research on their environmental fate, human health impact, analytical methods, and regulatory status and by highlighting their critical challenges. A comprehensive literature search focusing on publications from the last five years (2020–2025) was conducted using global scientific databases (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science) and regulatory reports (e.g., EPA, ECHA). The persistent and pervasive nature of PFASs stems from the highly stable carbon–fluorine (C-F) bond, leading to their widespread release from diverse industrial and consumer products into water, soil, and air. Key outcomes reveal significant analytical challenges in their detection, including sample matrix complexity, widespread laboratory contamination, and a lack of standards for the vast number of specific compounds. Critical research gaps were identified, particularly the limited data on PFAS concentrations in air and dust, the need for standardized analytical methods and reporting units, and the urgent necessity for developing scalable, sustainable remediation strategies. The ongoing environmental contamination and associated health risks necessitate continued, focused interdisciplinary research to improve detection, risk assessment, and the effective management of this complex class of pollutants.

1. Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a group of chemically stable, hydrophobic, and lipophobic compounds whose unique properties have made them exceptionally useful and widely adopted across numerous industries. However, their pervasive use in thousands of products worldwide for over 85 years has led to widespread environmental exposure because these persistent compounds do not readily biodegrade. Due to their specific chemical structure and persistence, PFASs are often called “forever chemicals”. They spread rapidly throughout the ecosystem, contaminating everything from rivers and groundwater to tap water. Simultaneously, efforts to remove or clean up contaminated areas frequently prove technically difficult, ineffective, and expensive. Potential health risks associated with PFASs include immune system disorders, hormonal and developmental issues, and an increased risk of certain types of cancer. Concerns about their impact on human health arise from their widespread occurrence, persistence in the environment, and ability to bioaccumulate. The global prevalence and harmful effects of PFASs on the human body, combined with the introduction of many new compounds into the environment, continue to pose challenges for fully understanding and managing the risks associated with their presence [1]. The problem is that each of these substances has different properties, is used for different purposes, or occurs as an unintended by-product of certain manufacturing processes. Even with major progress made in studying the origins and environmental pathways of this complex group of chemicals, many questions and challenges remain that the society will need to address in the upcoming years.

The growing knowledge on PFASs makes it impossible to definitively quantify their number or determine the precise impact of every specific molecule on human health. Literature sources consistently estimate that there are thousands of distinct chemical compounds [2,3,4]. According to the chemical database maintained by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), there are nearly 15,000 chemical compounds [5]. Furthermore, based on the PubChem classification, following the new PFAS definition published by the OECD in 2021, over 7 million types of PFASs have been identified globally, and this number continues to increase [6,7].

Due to their widespread environmental presence and negative impact on humans and ecosystems, several European Union Member States have proposed the complete elimination of PFASs from industry, or at least their significant reduction. These measures aim to reduce the release of PFASs into the environment and consequently lower human exposure. However, the long-range transport of these compounds complicates local restrictions. Current and proposed regulations often only target specific PFASs, overlooking the broader problem, which is further exacerbated by the lack of readily available, safe, and effective alternatives, as well as the need for the continuous evaluation of many other PFASs already in use.

Scientific interest in PFASs is enormous and constantly growing, as confirmed by the numerous publications in this area. A search for the term “PFAS” between 2020 and 2025 yielded nearly 51,331 results on ScienceDirect, 7055 on PubMed, and 7839 on Web of Science (August 2025). The objective of this review was to consolidate the foundational knowledge on PFASs, summarize the current state of research on their distribution in the environment, impact on human health, methods of detection, and regulatory restrictions, and present the latest scientific advances, while emphasizing critical challenges and unresolved research gaps in the field.

The literature search strategy covered only publications from the last 5 years (2020–2025). The primary search sources were global scientific literature bibliographies, including Google Scholar and PubMed, as well as Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, and MDPI. In addition to the peer-reviewed literature, this review also examined publications on legislation, as well as reports from relevant health agencies and regulatory authorities, including the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The literature included original works, reviews, observational and experimental studies, and government reports, as well as guides and websites.

Studies were qualified if they addressed one or more of the following topics: the characteristics and physicochemical properties of PFASs, their effects on human health and the environment, their occupational exposure, the health effects of PFAS exposure, restrictions on their use, the relevant regulatory frameworks, or their reduction strategies. This review also covered methods for detecting, identifying, and analyzing PFASs. The search was conducted by entering a specific title or keyword related to the topics selected for this review in the title and/or abstract of the publication. The examples of used keywords are as follows: “PFAS”, “perfluoroalkyl substances”, “polyfluoroalkyl substances”, “PFOA”, “PFOS”, and combinations of these names with words such as “occurrence”, “use”, “disposal”, “analysis”, “analytical methods”, “determination” (additionally supplemented with “in environmental samples”, “in biological samples”, “in air”, etc.), “environmental cycles”,” bioaccumulation”, “exposure”, “environmental pollution” (soil, water, air), “persistence in the environment”, “remediation”, “legal regulations”, “occupational exposure”, and “health effects” (“immune disorders,” “cancer,” “neurodevelopmental disorders”). Studies were included if they addressed one or more of the aforementioned topics. Only full-text, open-access articles published in English or Polish were considered. For certain topics, within the articles with only abstract, reference lists of eligible studies were further examined to identify additional sources providing detailed information relevant to gaps identified in the section content. The relevant data were independently extracted by each author and subsequently organized into thematic sections consistent with the structure of this review. Case studies and opinions, as well as lists, and editorials were excluded unless they contained unique data or perspectives. The results were subjected to qualitative synthesis, emerging evidence, and gaps in knowledge. In total, 136 studies and legal documents were included and described in this review. We aim to present the current state of research while highlighting critical problems and existing research gaps in this area.

2. What Are These Compounds?

According to OECD [8], “PFAS are defined as fluorinated substances that contain at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom (without any H/Cl/Br/I atom attached to it), i.e., with a few noted exceptions, any chemical with at least a CF3 or a perfluorinated methylene group (CF2) is a PFAS.” Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are organic compounds with very high chemical stability. Structurally, PFASs are generally categorized into compounds with a single aliphatic chain or polymeric compounds. A characteristic feature of their structure is the presence of fluorine atoms at each carbon atom instead of hydrogen atoms. However, this feature does not apply to the last carbon atom, which has a corresponding functional group. The general formula for perfluoroalkyl compounds is often represented as CnF2n+1-R, where n is the number of carbon atoms and R is the functional group.

The designation “perfluorinated” highlights that fluorine is the predominant element. The atomic structure of fluorine is crucial to the chemical and physical properties of PFASs: as the most electronegative element, it forms one of the strongest and most inert single bonds found in organic chemistry when bonded to carbon (C-F bond). The strength of the C-F bond increases further with a higher number of fluorine atoms bonded to the central carbon [6]. The most widely known PFASs are perfluorosulfonic acids and perfluorocarboxylic acids with carbon chain lengths from C4 to C14, particularly the eight-carbon acids: perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Another well-known compound in this group is perfluorooctanesulfonamide (PFOSA). In addition to carboxylic and sulfonic acids, PFASs also include less common functional groups, such as phosphinic acid, phosphonic acid, sulfonyl compounds, fluorotelomers, and perfluoropolyether [2,3,4,9,10,11]. Long-chain PFASs are typically defined as perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) with seven or more fully fluorinated carbon atoms and perfluoroalkanesulfonic acids (PFSAs) with six or more carbon atoms. Ultra-short-chain PFAS, on the other hand, are typically those with a carbon chain length of no more than three. These shorter-chain compounds are highly lipophobic and can be readily transported into marine ecosystems [12]. PFASs with shorter alkyl chains are more water-soluble than those with longer chains [13].

PFASs exhibit a wide range of physical and chemical properties, existing as gases, liquids, or high-molecular-weight solid polymers [14]. Their unique structure imparts specific physicochemical properties, making them resistant to other chemicals and conferring both hydrophobic and lipophobic characteristics. The fluorine-containing part of the chain is hydrophobic, while the functional groups at the chain’s end are polar as in the case of surfactants [15]. A single PFAS molecule consists of a mono- or polyfluorinated hydrophobic tail and a hydrophilic functional head, making it amphiphilic and oleophobic [6]. Physicochemical properties, such as the acid dissociation constant (pKa), air–water partition coefficient (Kaw), octanol–water partition coefficient (Kow), and liquid vapor pressure, are crucial for understanding the global transport and environmental circulation of these compounds [16]. PFASs can exist as cations, anions, or zwitterions, and these forms determine their electrical charge and physical and chemical properties, ultimately controlling their fate and transport in the environment [17].

PFASs also possess proteinophilic properties, meaning that upon entering the human system, they primarily attach themselves to proteins. The bonding of PFASs—especially longer-chain compounds like PFOA and PFOS—to common blood serum proteins (such as human serum albumin [HSA] and globulins) is considered to impact their delivery to active sites, their toxicity, and how long they remain in the body. PFASs vary in chain length and functional groups, which affects how they are transformed and cleared from the body, yet longer-chain types remain notably resistant to metabolic breakdown [13].

3. Occurrence and Use of PFASs

PFASs are entirely synthetic—man-made and not naturally occurring in the environment. Their non-stick, water-repellent, and high-temperature stability properties have driven their use in industrial and consumer products for decades. They are valued for their resistance to heat, water, and oil. Many also function as surfactants and are used, for example, as water and grease repellents [14]. Since the 1940s, they have been integral to manufacturing processes for items like non-stick cookware, fabrics, and food packaging, and their use continues across the chemical and consumer products industries [2].

PFASs have countless applications spanning most industries, including electronics, construction, aerospace, military, textiles, and automotive. They are used in the production of plastics and rubber, semiconductors, waterproof clothing, household goods, metals and alloys, food packaging, cleaning products, fire extinguishing foams, glass, optical devices, cables, and garden hoses [18,19,20,21,22]. Their use also extends to biotechnology, pharmaceutical industry, and mining. The lack of a complete list of specific industrial applications for compounds in this group [23] indicates that PFASs are potentially widespread in many everyday products. They may be present in carpets, furniture, paper, fabric coatings, and household items (including cables, solar panels, leather, and glass). They are most famous for their use in insulation materials, non-stick Teflon products (like frying pans), and firefighting products (e.g., firefighting foams), as well as in cosmetics and fluorinated waxes used by skiers.

PFASs serve as viscosity reducers in petroleum processing and, due to their hydrophobic properties, they are used in body and hair care products and as wetting agents in surface treatments for paper and printed food packaging. They are applied to textiles and surfaces to confer dirt- and grease-resistant properties. These compounds are often critical for delivering the high performance and durability needed in many products. This is especially true for PFASs used in medical technologies and can contribute to improving and prolonging patients’ lives, making it challenging to find suitable alternatives to replace them. PFASs are used as components of the final medical device, as part of an integral drug–device combination, or as auxiliary substances in the manufacturing process. Various components of analytical instruments incorporate PTFE or PVDF, for example, in the coating of dispensing tips. Tubes and connectors, dispensers, seals and valves for syringe pumps, O-rings, and sealants may also contain these compounds [14]. In many such applications, the current knowledge suggests that safer and equivalent alternatives are unavailable.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl compounds are also extensively used by fire services. PFOA and PFOS were historically used in the production of Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFFs). They are also used to coat firefighters’ clothing to enhance its hydrophobic and oleophobic properties and increase resistance to chemical and thermal hazards. However, it has been demonstrated that this coating can lead to the transfer of compounds to the inner layers of the clothing, allowing absorption into the body via sweat. PFASs are also released through mechanical abrasion from the surface of the clothing during use [24].

4. Environmental Persistence and Pathways

The extensive use of PFASs across nearly all industries has led to concerning environmental releases. Their extreme stability, conferred by the presence of the carbon–fluorine bonds, poses a significant threat. As noted, this is a polarized covalent bond, which is exceptionally stable due to the strong polarization associated with the large difference in electronegativity between the two atoms [4,6]. Consequently, PFASs are not easily broken down in the natural environment, cementing their status as “forever chemicals.” PFASs can be classified by their functional groups and physicochemical properties into categories such as ionic PFASs (i-PFASs) and neutral PFASs (n-PFASs), each with distinct environmental pathways [12]. I-PFASs have relatively higher air–water and n-octanol–water partition coefficients, so they tend to occur more frequently in aquatic environments. In contrast, n-PFASs are considered to be more volatile and are predominantly present in the gas phase.

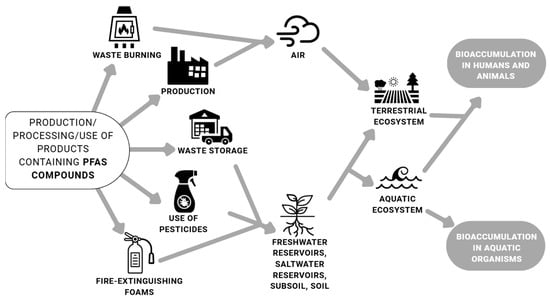

Atmospheric transport contributes to the global dissemination of these substances, meaning PFASs are not confined to their sources [25]. PFASs may be introduced into the environment via air, water, or sewage. Due to their high structural polarity, they are easily soluble and so transported in water. The key sources of PFASs in coastal waters include industrial wastewater, landfill site, and wastewater from sewage treatment plants. As a result, PFASs are directly released into runoff and carried into marine environments [12]. PFASs are deposited in aquatic systems depending on their chain length; longer PFASs are more prevalent in sediments and short-chain PFASs in water. Studies on the presence and spread of PFASs in marine ecosystems remain insufficient compared to studies about freshwater ecosystems. Nevertheless, some PFASs may pose a substantial risk to human health, for example, through the consumption of seafood [12]. The scheme of PFAS pathways of human and environmental exposure is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pathways of environmental and human exposure to PFASs [11,12,15,22].

While the exact environmental half-life of most PFASs is not well established, some polymers may persist in soil for over a millennium and other for over forty years [26]. Even while degrading, products are made of smaller PFASs, reinforcing their reputation as “forever chemicals”. The average half-life of most PFASs in soil can span years, increasing the likelihood of their absorption by plants and eventual entry into the human food chain. The uptake of PFASs by plants poses a direct threat to human health and significantly impacts the compounds’ fate and transport in the environment. PFASs primarily enter plants through their roots from the surrounding soil and water. For example, compounds used in firefighting foams are absorbed into the soil and then transported by groundwater into the wider environment [27]. Due to their high water solubility, PFASs are easily absorbed and transferred to plant tissues. However, water solubility varies depending on the specific PFAS, which in turn influences its transport and uptake by plants. Furthermore, the composition of PFAS isomers in soil, water, and living organisms is largely affected by location, which is linked to differences in how these compounds are manufactured.

According to Nannaware et al. [28], PFAS release methods into the environment should be categorized into two main types:

- Point Sources: these include sewage, firefighter training sites, wastewater treatment plants, and facilities manufacturing fluorine compounds.

- Non-Point Sources: these result from the disposal of PFAS-containing products, runoff from agricultural fields, precipitation, and the use of contaminated groundwater [28,29].

The use of PFAS-containing pesticides and insecticides in agriculture can lead to their unintended accumulation in soil and plants, negatively affecting crop yields. Studies have demonstrated that PFASs readily migrate into groundwater [26], tap and bottled water [30], and surface water [31]. They are released at almost every stage of their life cycle, from production, processing, and use to disposal [15].

The release of PFASs during recycling and lithium-ion battery fires in recent years has attracted increasing attention, but research in this area is still limited [32,33]. Due to the release of PFASs during recycling, there is a need to produce lithium-ion batteries that do not contain PFASs or to find alternative solutions [34,35,36].

5. Determination of PFASs in Environmental Samples: Analytical Methods, Challenges, and Research Gaps

Analytical methods that enable the determination of cumulative PFAS exposure are essential for assessing the risks associated with this class of chemicals [1]. Most studies in the literature are limited to analyzing compounds such as PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS (a common substitute for PFOS). The effective detection and management of PFASs necessitate advanced analytical tools capable of identifying these compounds at very low concentrations across diverse environmental matrices.

Numerous methods for determining PFASs have been described in the literature, primarily focusing on their occurrence in water, soil, and air [37,38,39,40,41,42], as well as in food packaging and used textiles [43,44]. Given their potential for bioaccumulation, studies also investigate PFASs in biological samples such as chicken feathers and human hair [45,46,47], plants [48,49,50,51], and the aquatic environment [52,53,54,55].

Water samples are the easiest to measure, as measurements can be performed directly on the samples. If the detection limit is too high, SPE should be performed. Most tests are carried out on water samples.

Liu et al. [56] reported significant advances in PFAS detection techniques in biological samples in recent years, with particular emphasis on methodological improvements such as the optimized pre-treatment of samples. However, PFAS analysis in biological matrices remains highly challenging due to the presence of matrix interferences, low analyte concentrations, the coexistence of multiple homologues and isomers, and poor sample stability. Both liquid and solid biological samples possess intricate compositions; for instance, the strong affinity of PFASs for proteins often results in incomplete extraction from protein-rich matrices. Additionally, inter-individual variability, environmental influences, and dynamic physiological changes further complicate quantification. These factors collectively impose stringent requirements on sample preparation and analytical detection techniques for PFASs in biological samples.

Sample preparation for analysis is crucial for non-aqueous matrices. Contamination and recovery efficiency pose serious analytical challenges in these cases. Soil and sediment samples require more intensive processing in comparison to water. After collecting such samples, they are often dried, sieved, extracted, and concentrated. The process of extracting PFASs from soil and sediments involves extraction with alkalis, acids, or organic solvents. The use of certain types of extraction can lead to a strong matrix effect that may change the recovery rate by approximately 30%. Matrix co-extractives (humic substances, lipids, salts) commonly suppress or enhance LC MS signals, and can coelute with short-chain PFASs or precursors, causing biased quantification unless addressed by clean up or dilution. These methods most often use solid-phase extraction (SPE) or supported liquid extraction (SLE), which for samples with high total suspended solids (TSSs) can lead to the clogging of cartridges. Analyzing PFASs in soils, sediments, and air is challenging due to complex extraction processes, strong matrix effects, widespread contamination from laboratories and reagents, variability in ionization and fragmentation, and the limited availability of standards and validated methods. These factors introduce compound-specific biases that compromise data comparability and prevent accurate total PFAS mass balance [38,39,57,58,59,60].

For indoor and outdoor air samples, a sampling process may last several hours and must be carried out using a sorbent, filters, a polyurethane foam (PUF), or XAD-2. Sampling can be either active or passive. Cascade impactors are also found in the literature for separating PFASs according to their particle size. The samples obtained in this way are extracted using solvents or SPE. When analyzing PFASs in air, problems such as low concentrations in air, which require very sensitive methods, and the influence of the matrix on possible interferences must be addressed. PFASs can occur in both gaseous and particulate forms, which require the use of different types of samplers in contrast to solid samples. Due to the lack of scientific research, many PFASs still do not have methods for their determination in air [40,41,61,62,63,64].

From an analytical perspective, PFASs present a major challenge for all laboratories. Understanding and limiting sources of contamination in PFAS analysis is crucial due to their pervasive use in various laboratory products and materials. Laboratory materials, solvents, and carryover from high-concentration samples or column contamination result in blank samples that can mask low-level environmental signals or cause false-positive results. The adsorption of PFASs onto surfaces or sampling tubes and in the laboratory causes losses and variability between samples. Rigorous field and procedural blanks are necessary and often reveal measurable contributions from PFASs.

Targeted analytical approaches for PFAS determination encompass multiple environmental and biological matrices, notably drinking water, surface water, and groundwater; air and airborne particulates; food; solids such as soil, sediments, and house dust; consumer products; and biological specimens including plasma, serum, urine, breast milk, and muscle [22].

Due to the ease with which per- and polyfluoroalkyl compounds enter groundwater, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends methods utilizing liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS), specifically the triple quadrupole detector, for their detection:

- Method 537.1: recommended for determining 18 PFASs, including PFOS and PFOA, in drinking water using solid-phase extraction (SPE).

- Method 533: For drinking water, this method uses the same type of chromatograph but additionally employs isotope dilution. It determines a total of 25 PFASs, including, in contrast to Method 537.1, compounds with shorter carbon chains.

- Method 8327: recommended for groundwater, surface water, and wastewater matrices; this method also utilizes LC/MS/MS chromatography with isotopic dilution of the sample.

- OTM-45: For airborne PFASs, this method involves collecting air samples and trapping PFASs on a fiberglass or quartz filter and a sorbent tube connected to a series of scrubbers. The resulting four air samples are analyzed separately using LC/MS/MS, and the amount of analytes is calculated using the isotope dilution method.

In accordance with the European Commission Notice (C/2024/4910) [65], the method described in standard EN 17892:2024 [66] has been proposed for the parameter “Sum of PFAS,” which specifies 20 particular per- and polyfluoroalkyl compounds found in drinking water. This method also uses the LC/MS/MS technique. Depending on the quantification limit of a given analyte, measurements can be performed directly on the water sample. However, if the quantification limits are insufficient (below 1 ng/L), solid-phase extraction must be used.

For determining the parameter “total PFAS,” analytical methods are used to collectively quantify per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, regardless of the carbon chain length. According to the European Commission Notice (C/2024/4910), these methods include the following:

- TOP (Total Oxidizable Precursors) testing;

- EOF-CIC (Combustion Ion Chromatography after organic fluorine extraction);

- LC-HRMS (liquid chromatography combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry).

These methods are currently considered substitute techniques that have not been fully validated and do not yet allow for the accurate quantitative determination of the “total PFAS” parameter. Such advanced methods provide the sensitivity and selectivity necessary to detect PFASs in complex samples, making them invaluable for both environmental monitoring and regulatory compliance. Table 1 summarizes these methods and their limitations.

Table 1.

Summary of current methods for determining PFASs in various matrices.

A review of non-targeted PFAS detection methods by Megson et al. [76] suggests a geographical bias in the literature, with most studies conducted in the United States and China. The authors note that further research is needed, particularly on the marine environment and the atmosphere, as well as more human biomonitoring studies on potentially exposed groups to better understand health risks, biotransformation routes, and the composition of commercial products. Future research must cover all geographic regions to achieve a more holistic understanding of PFAS distribution and global environmental impact. Idowu et al. [77] also highlight a critical research gap in measuring PFAS concentration in air and dust, describing it as insufficiently studied. Currently, most of the literature data focuses mainly on measuring PFAS concentrations in water, biological material, and soil. However, testing of air samples, which is also an important carrier for PFASs, is very often overlooked. More research should therefore be devoted to this neglected area. Idowu et al. [77] also noted a wide range of limits of detection (LOD values) across and within different sample matrices, underscoring the challenges associated with selecting appropriate PFAS quantification methods. They also suggest standardizing units for concentrations to enable the consistent comparison of results. Applying the wrong method to calculate the total PFAS content can lead to overestimation or underestimation, which would harm both PFAS manufacturers and environmental protection efforts. For instance, methods for determining total fluorine have limitations, so using different methods on the same sample can yield results that vary by several orders of magnitude. Therefore, a better standardization of both instrumental analysis methods and reporting is necessary. The main obstacles are also insufficient certified reference materials (CRMs), limited interlaboratory studies, and rare authentic standards for new/neutral PFASs, which hinder the comparability and accreditation of methods.

6. Environmental Impact and Remediation

The environmental impact of PFASs is multifaceted, affecting aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and microbial communities. PFASs affect the environment by accumulating in living organisms due to their hydrophobic, lipophobic, heat-resistant, and non-biodegradable properties. They influence microbial populations, with some microbes thriving in PFAS-contaminated environments while others decline [78]. However, little is still known about the effects of environmental exposure to PFASs, the combined toxicity at concentrations found in the environment, and how they interact with other anthropogenic stressors [79,80].

The concentration of PFASs in aquatic environments is influenced by physicochemical parameters such as pH, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen, which can affect their mobility and bioavailability [81]. Conventional biological and chemical treatment processes, including advanced oxidation processes, have proven insufficient for removing PFASs from wastewater [82]. Partitioning effects likely control the elution of long-chain compounds, while the leaching of smaller PFASs is influenced by climatic conditions [83]. The adsorption of PFASs in soils is, in turn, affected by soil composition and environmental factors, with hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions playing a significant role in their retention [84].

According to Abunada [82], the use and reuse of sewage sludge on farmlands is one of the primary contributors of soil pollution. Other sources include the degradation of fluorotelomer-based materials, which release PFCAs, precipitation, and irrigation. The toxicity of PFASs and their impact on soil microorganisms can degrade soil quality, negatively affect its functionality, disrupt soil enzyme activity, alter the availability of microorganisms, and damage cell structure. Contaminated soil is challenging because there is no specific strategy for in situ PFAS remediation. A main concern associated with PFAS in soil is the potential for plants to uptake and transfer PFASs, as well as the possible leaching of PFASs into deeper soil layers and groundwater [84].

Alain F. Kalmar et al. [84] point out that fluorinated volatile anesthetics like sevoflurane and desflurane, classified as PFASs, not only contribute to atmospheric pollution through their greenhouse effect but also produce degradation products such as hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), which introduce PFASs into aquatic ecosystems, posing a risk of long-term persistence.

To address the global challenge of PFAS pollution, there is an urgent need to develop sustainable and effective remediation strategies. Phytoremediation has emerged as a promising, environmentally friendly approach that can mitigate the spread of these persistent pollutants. However, resolving this issue requires interdisciplinary, innovative research to develop comprehensive and scalable solutions for effective PFAS management. Examples of methods for removing PFASs from the environment include bioremediation, chemical oxidation, adsorption, and photocatalytic degradation [85,86,87,88]. Certain studies also confirm the validity of high-temperature incineration and the plasma destruction of PFASs in waste [82]. Certain bacterial species have shown potential for PFAS bioremediation [89]. There are reports on the use of machine learning for the management of PFASs, including monitoring to predict contamination, optimizing removal technologies, and guiding management strategies [90].

As highlighted by Alam and Gang [27], exposure to PFASs occurs through multiple pathways, affecting humans, animals, and invertebrates, as well as fauna and flora. Differences in exposure patterns are observed in different geographical regions and demographic groups, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and risk reduction strategies. The main paradigm for the future of PFAS management is a change from simple removal, e.g., through adsorption on activated carbon, which generates problematic secondary waste, to permanent destruction. Electrochemical degradation (ED) is one of the most promising technologies in this area. It is a destructive method that works using only electricity and electrodes, minimizing the need for added chemicals and reducing secondary waste production to non-harmful salts, gases, and degraded organic matter. ED is effective against both short- and long-chain compounds [91]. Due to the persistence of PFASs, it is considered impossible to eliminate them. Therefore, the measures taken are mainly aimed at reducing their use and retreating existing sources. The rising awareness on PFAS-related environmental impacts may promote efforts to limit their use and foster the creation of sustainable alternatives. In parallel, informed consumers are increasingly likely to demand PFAS-free products, influencing manufacturers to prioritize alternatives [14].

7. Bioaccumulation in Humans and Animals

PFASs demonstrate a high potential for bioaccumulation in both humans and wildlife, primarily through binding to blood proteins, e.g., albumin or fatty acid-binding proteins, before accumulating in adipose tissue as is typical for most other bioaccumulative chemicals. This process occurs through absorption with limited excretion, resulting in increasing concentrations along the food chain [17].

While short-chain PFASs are eliminated more quickly (e.g., the half-life of PFBS in blood is 26 days), they still accumulate in various organs such as the lungs, kidneys, and brain. Available studies indicate that these compounds tend to accumulate in the blood, liver, kidneys, and bones. The geometric mean for the elimination half-life in human serum is 4.8 years for perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), 7.3 years for PFHxS (C6), and 3.5 years for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) [17,92].

Despite the phasing out of “older” PFASs such as PFOA and PFOS, these compounds continue to be the dominant ones detected in human serum. Concurrently, human exposure to short-chain PFASs, as well as newly emerging compounds like 6:2 CI-PFESA, is growing. Current estimates indicate that human exposure to PFASs from multiple pathways is approaching the tolerable intake levels recommended by global health authorities. Infants, however, experience comparatively higher exposure doses, reflecting their greater vulnerability and intake relative to body weight due to PFAS concentration in breast milk exceeding drinking water limits recommended in many Western countries [1].

The bioaccumulation of PFASs in human organs and tissues is a critical public health concern. Human biomonitoring studies have detected PFASs in blood, breast milk, placenta, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, cerebrospinal fluid, semen, nails, hair, feces, and urine. Therefore, advancing knowledge about the mechanisms of PFAS accumulation and associated health effects is essential for risk reduction and establishing effective regulatory policies and remediation strategies [93].

Modeling PFAS bioaccumulation is difficult because their properties differ significantly from known models of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), e.g., their amphiphilic properties, unlike the neutral, lipophilic properties of traditional POPs. PFASs, especially long-chain variants, preferentially bind to proteins (such as blood plasma proteins) and phospholipids in tissues (e.g., liver, blood) rather than to neutral fat. Their distribution in different tissues (e.g., liver vs. muscle) also varies depending on the compound and species. Active transport and elimination, bioavailability, and uptake of PFASs by plants and organisms further increase the variability of bioaccumulation factors. The models often oversimplify the complex biological mechanisms that govern the long half-lives and distribution of many PFASs in organisms [94,95].

8. Toxicity and the Effect of PFASs on Humans

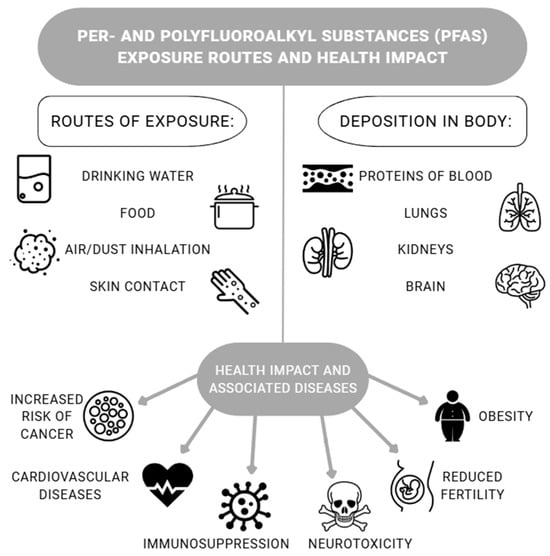

The main route of human exposure to PFASs (including the best-known compounds PFOS and PFOA) is through dietary intake and drinking water consumption (Figure 2). The systemic absorption of PFAS sin humans, therefore, occurs primarily through the digestive system. Some PFASs may pose a significant risk to human health through the consumption of seafood [12]. Absorption through the skin and respiratory tract is lower compared to that with ingestion, especially in people not regularly exposed to these chemicals [54]. Products containing PFASs (such as furniture and carpets) typically have a very long service life, meaning PFASs can be released from them over many years and found in dust and indoor air [16]. The differences in PFAS toxicity are influenced by their chemical diversity. Minor changes in the length of the perfluoroalkyl chain or functional group can significantly alter the toxicological profile. The persistence of some PFASs in the human body is a key factor in determining their toxicological risk. Compounds with long predicted half-lives are considered to pose an increased risk to human health due to chronic accumulation [96]. The long half-life of PFASs in the body causes the chronic exposure of tissues, where the chemicals continuously interact with nuclear and membrane receptors, causing health problems in many organ systems. Observed adverse effects span the entire lifespan, from prenatal developmental disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders to chronic adult diseases, including cancer, thyroid dysfunction, and serious metabolic and liver disorders [97]. Biological factors affecting toxicity such as species differences or individual susceptibility should also be mentioned, as well as obvious dependencies on the dose, frequency, route, and duration of exposure [98].

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances can cause health disorders in various human systems, mainly the nervous and endocrine systems. The harmful effects of long-chain PFASs on the endocrine system, for instance, are confirmed by the research [99].

Findings from epidemiological research indicate that PFAS exposure contributes to multiple physiological disturbances, notably decreased birth weight, immune system impairment, endocrine disruption, liver toxicity, and altered lipid metabolism [1]. According to the EPA [2], exposure to certain levels of PFASs can lead to reproductive effects (e.g., reduced fertility or elevated blood pressure in pregnant women) and developmental effects, disorders, or delays in children (including low birth weight, accelerated puberty, bone changes, or behavioral changes). Studies by Nnabuchi et al. [17] confirm that PFAS exposure is also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and disturbances in menstrual cycle. Some PFASs, e.g., PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, and PFUnDA, can cross the placenta, although at reduced concentrations compared to maternal blood levels. In fetuses, liver and lung research showed the highest accumulation of PFASs among the studied organs, suggesting potential organ-specific susceptibility [93].

Figure 2.

PFAS exposure and health effects on humans [2,11,16,17,27,100,101,102].

Exposure to PFASs is also associated with an increased risk of certain cancer, including prostate, kidney, and testicular cancer [100,101]. In 2023, the IARC classified PFOA as “carcinogenic to humans” (Group 1) based on sufficient evidence of cancer in experimental animals and strong mechanistic evidence in exposed humans. Strong mechanistic evidence supporting the IARC classifications for PFOA is based on consistent data confirming two key characteristics of carcinogens, namely epigenetic changes and immunosuppressive effects observed in exposed humans, even in the absence of overwhelming epidemiological data on cancer incidence [103]. There was limited evidence of cancer in humans for renal cell carcinoma and testicular cancer. PFOS was classified as “probably carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2B) based on strong mechanistic evidence [102].

There have also been reports that higher levels of PFASs may be associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer, and indications of a potential link between PFAS exposure and breast cancer, particularly in certain populations [104].

PFAS exposure is also associated with a reduced ability of the immune system to fight infections or elevated cholesterol levels that increase cardiovascular risk and/or the risk of obesity [101,105]. Perfluorinated substances affect immune cells by altering cytokine expression, which reduces the activity of macrophage-activating genes or induces inflammasomes in tissues such as the liver [105]. Immunosuppression may therefore be one of the most critical and widespread adverse health effects caused by PFASs, potentially affecting vaccine efficacy across the population and overall susceptibility to disease.

Studies have shown that PFASs have toxic effects on the human body, which depend on their concentration and type, and that they can act synergistically to harm the body [27,106,107,108]. Assessing their effects unequivocally is difficult because there are thousands of PFASs with potentially different effects and levels of toxicity. Humans are exposed to them at different stages of life and in diverse ways. The types and uses of PFASs change over time, complicating the tracking and assessment of exposure and health impacts. Simultaneously, most studies focus on a limited number of the better-known PFASs [2]. The number of substances, combined with the extreme environmental persistence and bioaccumulation potential of many variants, requires extensive analysis of factors influencing the variability of observed toxicity data. Given that people are exposed to a mixture of PFASs rather than individual substances, deLuca et al. [109] conclude that the combined effects of PFASs need to be better understood.

According to Shen [101], people exposed to high levels of PFASs at work or at home should undergo regular blood tests to monitor potential adverse health effects. The author emphasizes that those with blood concentrations above 20 ng/mL of seven commonly detected PFASs are most at risk for adverse health effects. Those with levels between 2 and 20 ng/mL are also at some risk, indicating a need for awareness and monitoring. Jun-Meng Jian et al. [16] assessed that blood type, area of residence and work, age, and gender are strongly associated with PFAS levels in blood samples. Urinary PFAS profiles varied with the size of PFASs and gender, confirming excretion through urine as a key elimination pathway. Levels in breast milk were influenced by maternal age, diet, and pregnancy stage, while data on hair and nails are still limited, though these provide a promising non-invasive means of exposure assessment.

Despite significant progress, particularly concerning the best-known PFOA and PFOS, there are still major gaps in knowledge concerning their toxicity. There is an urgent need to continue research aimed at characterizing the health effects associated with chronic exposure to low levels, especially in children. Moreover, humans are exposed to complex mixtures of PFASs and other environmental contaminants, but toxicity studies often focus on single compounds. Future research should therefore focus on understanding the complexity of mixtures by investigating the combined toxic responses of PFASs with other micropollutants that have shown antagonistic and synergistic effects [110,111]. The complexity involved in predicting the behavior and risks of the entire PFAS family—including unpredictable half-lives, QSAR (quantitative structure–activity relationship) limitations, high mobility of substitutes, and complex, dose-dependent modes of action—strongly supports a broad, precautionary regulatory strategy. This approach must prioritize the management of PFASs as a persistent, mobile chemical class, rather than pursuing the resource-intensive risk assessments of individual compounds that inevitably lag behind innovation and substitution [95].

Replacing PFASs with alternatives requires targeted toxicological studies on the cumulative effects of complex mixtures of these compounds and the full range of health effects caused by newer, emerging types of PFASs. Replacing PFOA and PFOS with shorter-chain analogs due to their reduced potential for bioaccumulation in humans (as they are less persistent and are excreted more rapidly from the body) poses a significant challenge in risk management. Despite the change in toxicokinetics, scientific evidence indicates that substitutes (e.g., alternative short-chain substances of the new generation, such as perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) and GenX (HFPO-DA)) may still have adverse effects on human health, and their toxicity profile is similar or sometimes more harmful than that of the PFASs they replace [97]. Furthermore, these short-chain alternatives are often more mobile in the environment, leading to widespread contamination and accumulation in the water cycle, thereby shifting the exposure burden rather than eliminating the underlying hazard. Comprehensive strategies for monitoring and reducing exposure to PFASs and their substitutes are essential for protecting public health [112].

A scientific challenge is certainly to generate information more quickly on the toxicity of commercially available PFASs as data are lacking on their modes of action and adverse effects. This requires an intense focus on high-throughput omics approaches (transcriptomics, high-content analysis) and machine learning models to rapidly cluster PFASs by biological activity [97]. New technologies, such as machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), enable the simulation of potential toxicity, including neurotoxicity associated with the impact of PFASs on the human brain or their influence on metabolic pathways in the human body. These simulations can help predict the effects of individual or entire groups of PFASs. Fang Cheng, et al. [113] believe that using modeling and AI in identifying PFAS sources offers promising opportunities for better understanding the pathways and sources of contamination. New methods, including high-throughput screening, molecular dynamics, and benchmarking, are seen as key strategies for accelerating data generation. However, a significant limitation is that the results obtained with these methods are intended for screening and identifying tests for further study rather than for the definitive determination of toxicity. They should undergo rigorous validation to ensure their reliability and accurate reflection of dose–response relationships across species. Regulatory agencies take a precautionary approach based on relative risk assessments obtained through these methods, as complete quantitative data for each new compound could take decades to obtain [95].

9. PFAS Exposure in the Workplace

Occupationally exposed populations exhibit some of the highest exposure to PFOA and PFOS, where the main route of exposure is inhalation, and potentially also skin absorption and dust ingestion. Many authors point to the limited number of studies focusing on PFAS exposure in the workplace, thus highlighting a gap in the existing literature [19]. Historically, workplace studies have focused primarily on fluorochemical plant workers involved in PFAS production, indicating a lack of understanding of the full extent of PFAS exposure in other occupations. Meanwhile, industries and occupations of particular concern for worker exposure include chrome plating, paper manufacturing, floor waxing, and textiles [23]. The highest exposure occurs not only among fluorochemical production workers [102] but also among firefighters and ski waxers [100].

High levels of PFAS exposure among chrome platers and welders, according to Göen et al. [114], can be attributed to the historical use of PFOS as a mist suppressant in electroplating baths. This may have affected not only workers directly involved in chromium plating but also those performing maintenance and repair tasks in these environments, such as welders. Potential sources of exposure also include waste management facilities [115] and areas of production and use of biostable substances, with industrial wastewater discharges. Additionally, some pesticides contain PFASs as inert ingredients, which can lead to contamination in agricultural and environmental settings. Firefighting facilities and training areas, which store, use, or release fluorinated firefighting materials like foam, are also particularly vulnerable [26]. The use of PFASs in electronic products also poses a significant potential for exposure (via inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact) for people involved in the disposal and recycling of e-waste [116]. Studies have shown the elevated levels of PFASs in urine, serum, and hair samples collected from electronic waste workers. However, the detailed epidemiological studies of at-risk populations are needed. It is important to recognize that PFAS exposure may also affect workers in less obvious occupations, requiring broader research and prevention strategies.

In a review by Paris-Davila et al. [117], ski waxing stations showed the highest concentrations of PFASs in the air among the studied occupations. Assessing the occupational exposure to specific PFASs in ski waxers can be difficult because manufacturers rarely disclose the exact composition of waxes. Furthermore, waxing occurs under varying conditions and temperatures. The compounds present in the blood serum of this group of workers are primarily PFOA, PFNA, PFDA, PFHpA, and PFDoDA. An analysis conducted by Lucas et al. [23] suggests that ski waxers and firefighters are subject to mixed PFAS exposure, often reaching or surpassing concentrations measured in occupationally exposed workers to PFASs and in populations consuming contaminated drinking water, and significantly exceeding background levels in the general population. Most studies have been conducted on serum samples from individuals exposed to PFASs both occupationally and in areas of potentially increased exposure. Communities adjacent to sites where PFASs are manufactured, stored, or used are considered to be most at risk [118].

The exposure of firefighters is slightly more complex. They are likely to be exposed to PFOS and PFHxS, as these are components of Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFFs), and PFOA and other PFASs may also be present in AFFFs as unintended by-products. Due to the widespread presence of PFASs in everyday equipment, firefighters are also exposed during firefighting operations, during which these compounds are released into air in the form of dust [119,120]. They may also be exposed to PFASs released from the clothing and personal protective equipment they wear, as well as during training and equipment cleaning. Potential exposure also occurs through their skin and digestive tract. According to a literature review, exposure among firefighters who began service after AFFFs were replaced with fluorine-free foams was similar to that in the general population. Mazumder et al. [119] emphasize that firefighters and fluorochemical plant workers may also have been exposed to contaminated drinking water. Studies show that these compounds are found in the blood of firefighters, yet there are few reports on other occupational groups exposed to compounds in this group [23], especially concerning blood concentration levels in workers. This highlights the need for quantitative studies on occupational exposure to PFASs in all populations of potentially exposed workers.

As evidenced from the literature review, there is a clear need for further research into occupational exposure across different industries and the development of recommendations to protect workers from the adverse health effects associated with PFAS exposure, including the implementation of safety protocols and guidelines tailored to specific industries where PFAS exposure is common [117,121].

10. Latest Regulations on Restricting the Production and Use of PFASs

Due to the persistent nature and risks posed to human health and the environment, the production, import, sale, and use of PFASs have been subject to systematic restrictions globally since the beginning of the 21st century. Many countries are introducing regulations that impose limits on selected PFASs in various products and materials, including food, water, and the workplace environment. The article by Schiavone C. and Portes C. [122] discusses the legislative measures taken by 2022 in the European Union, as well as in the USA, Canada, Australia, and the Asian and African regions, concerning the monitoring and restriction of PFAS content in consumer products and the environment. This began with the inclusion of certain PFASs in the requirements of the Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and Regulation (EC) 850/2004 on persistent organic pollutants, which was replaced by Regulation (EC) 2019/1021 [123,124].

Perfluorooctane sulfonates (PFOSs) and their derivatives have been subject to a global ban under the Stockholm Convention since 2009 and have been banned in the EU for over a decade [125]. Perfluorooctanoic acids and their derivatives were added to the Stockholm Convention and have been completely banned in the EU since 4 July 2020. Perfluorohexanesulfonates and their derivatives were added to the Convention in 2022.

PFOS and PFOA are classified as Group A, meaning participating countries must take measures to eliminate the production and use of these chemicals. PFHxS is classified as Group B, requiring measures to restrict production and use. These bans include the marketing of products containing these substances, effectively eliminating them from consumer products in the EU. In May 2023, the Stockholm Convention classified PFOS and PFHxS as persistent organic pollutants [126].

The European Union has adopted a systemic and centralized approach to managing and reducing the risks posed by PFASs to humans and the environment. The basic legal document regulating restrictions on hazardous chemicals is Regulation 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals [127]. Annex XVII of REACH concerns restrictions on the manufacture, placing on the market, and use of certain hazardous substances, mixtures, and articles, to which new regulations concerning PFASs are systematically introduced.

In recent years, European Commission Regulation 2021/1297 [128] was established, adding perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCA C9–C14), their salts, and related substances belonging to the PFAS group to Annex XVII. The manufacture and placing on the market of these compounds on their own are prohibited from 25 February 2023. The same prohibition applies to their use as a component of another substance, mixture, or article, except where the concentration of the acid is sufficiently low.

Further restrictions to Annex XVII of REACH were introduced by Commission Regulations (EU) 2024/2462 [129] and 1297 [128] recommending the addition of undecafluorohexanoic acid, its salts, and related substances. These regulations came into force on 10 October 2024, resulting in a ban on the marketing of these compounds on their own, as well as in concentrations equal to or greater than 25 ppb for the sum of PFHxA and its salts or 1000 ppb for the sum of PFHxA derivatives, measured in homogeneous material in various articles.

This ban targets items including textiles, leather, and fur intended for the general public, paper used for food packaging, cosmetic products, and fire-fighting foams. Transition periods were introduced to allow Member States to comply to the following:

- 10 April 2026: first bans take effect, e.g., on the use of PFHxA firefighting foams for training and by fire services, and use in clothing textiles, footwear, and food packaging.

- 10 October 2027: deadline for textiles, leather, and fur other than in clothing and related accessories.

- 10 October 2029: applies to more specialized applications, allowing industry time to find substitutes.

- Exemptions: some applications deemed critical are exempted from the ban, e.g., semiconductors, lithium-ion batteries, and hydrogen fuel cells, where no safe alternatives exist.

The recommendations of the Stockholm Convention and the REACH Regulation regarding the ban on the marketing or restriction of PFASs have led to changes in the production of certain types of PFASs. Since 2023, the production of long-chain PFASs (CF2 ≥ 7 for carboxylates and CF2 ≥ 6 for sulfonates) has decreased significantly in favor of short-chain PFAS (CF2 ≤ 6 for carboxylates and CF2 ≤ 5 for sulfonates) [130].

In May 2025, the European Commission published a draft of the next regulation introducing restrictions on the use of PFASs into Annex XVII of the REACH Regulation [127]. This draft proposes to restrict the use of PFASs containing at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom in the methyl (CF3) or methylene (CF2) group. Specifically, these substances will not be placed on the market or used in firefighting foams in a concentration equal to or greater than 1 mg/L for the sum of all PFASs within five years of the draft regulation’s enforcement. This restriction does not apply to PFASs already covered by the restrictions under entries 68 and 79 of Annex XVII of REACH and Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 [124].

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) has included two groups of PFASs on its Candidate List of Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC): perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) and its salts in 2020 and perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHA) and its salts in 2023 [125]. These are commonly used substitutes for PFOA and PFOS. Businesses placing these substances on the market are required to inform customers about the risks they pose to health and the environment. Furthermore, these substances may potentially be subject to a future marketing ban.

Another legal act regulating chemical safety in EU countries is Regulation 1272/2008 on the classification, labeling, and packaging of substances and mixtures [131]. This regulation obliges manufacturers, importers, and downstream users of hazardous substances and mixtures (which include all compounds from the PFAS group) to classify, label, and package them appropriately before placing them on the market. Currently, 12 PFAS have a harmonized classification and are labeled in accordance with CLP requirements (Table 2).

Table 2.

PFAS limit values and classification according to CLP [132].

These include perfluorooctanoic acid, lithium perfluorooctanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, which are frequently used across various sectors of the European economy and pose a risk to a large population of users and workers who manufacture, process, and use PFASs.

Further EU regulations limiting the risks posed by PFASs are directives and regulations setting maximum levels in drinking water and food to protect citizen health. Restrictions on PFAS content in drinking water were introduced by Directive 2020/2184 [133] on the quality of water intended for human consumption, which Member States were to implement as national legislation by 12 January 2023. According to the annexes, Member States must ensure the following:

- The total content of all PFASs (referred to as “PFAS total”) does not exceed 0.5 μg/L.

- The concentration level of the subset of 20 selected PFASs (referred to as “PFAS Sum”) is below 0.1 μg/L.

From 2024, following the publication of technical guidance on methods of analysis for the monitoring of PFASs in water intended for human consumption [65], Member States assessing water quality may decide whether to use “PFAS Total” or “Sum of PFAS” as a water quality indicator. By 12 January 2026, at the latest, Member States must take the necessary measures to ensure compliance with the parametric values set for PFASs by Directive 2020/2184 and are required to monitor water quality using methods established by the Commission.

The main source of human exposure is food of animal origin. For this reason, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) issued an opinion in 2020 on the risk assessment of PFASs in food [105], recommending new maximum levels. Maximum levels for PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, PFRHxS, and their sum in eggs, fish meat, meat, and offal were introduced on 1 January 2023 by Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/2388 [134]. The acceptable ranges for individual PFAS groups vary depending on the type of foodstuff:

- PFOS: 1.0 ÷ 50.0, PFOA: 0.3 ÷ 25.0 PFNA: 0.7 ÷ 45 PFHxS: 0.3 ÷ 3.0 [ng/kg].

- Total PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, and PFHxS: 1.7 ÷ 50.0 ng/kg.

Working environments are another source of complex PFAS mixtures, posing a threat across various economic sectors [17,102]. The European Commission has not yet set binding occupational exposure limit (OEL) values, despite these substances being classified as reprotoxic (Repro. 1B). Only a few EU countries, namely Belgium, Germany, Poland, and Switzerland, have set their own OEL values for selected PFASs (Table 2).

Occupational exposure limits are a primary indicator enabling employers to assess the risks posed by these hazardous substances in many areas of the global economy. Setting OELs for individual PFASs is a never-ending task due to the great number of substances in this group of hazardous substances. Therefore, further work on establishing BOELVs worldwide should focus on PFAS subgroups with similar toxic effects.

Due to the possibility of PFASs being absorbed by humans and animals through food, respiratory system, skin, and mucous membranes, it is advisable to expand scientific research aimed at establishing acceptable concentrations of PFASs or their metabolites in biological material (DSB) and developing methods for their determination, which will enable a correct assessment of the exposure of the population to PFASs.

As stated in articles by Schiavone C. and Portesi C. [122] and Thomas T. et al. [135], countries in Africa that have ratified the Stockholm Convention and developed national plans to implement POP reduction in the environment do not include measures to minimize exposure to PFASs. The reason for this is that these plans were developed before PFASs were included in the Convention list. No reports were found in the available literature concerning the introduction of legal regulations to limit exposure to PFASs in African countries after 2023.

Also, the activities until 2023 of countries in the Asia-Pacific region were presented by Schiavone C. and Portesi C. [122] and Thomas T. et al. [135]. The Stockholm Convention influences much of the PFAS regulations in the Asia-Pacific region. Countries including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand have prohibited or restricted PFASs. However, the regulatory landscape in these countries continues to evolve, with several of them adopting progressive measures that mirror approaches taken in the US and EU. Since Asian countries lack regulations on PFAS restrictions in food and various consumer products (clothing, toys, electronic equipment) commonly imported from Asian countries, it is also necessary to develop legal provisions to permit the import of these goods into the supply chain.

The regulatory system in the United States is fragmented and based on federal laws and laws with significant state-level impact. PFAS regulations are controlled by the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which requires all manufacturers (including importers) of PFASs and PFAS-containing products in any year since 2011 to report to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on chemical characteristics, uses, production and processing volumes, by-products, and environmental and health impacts. Under the TSCA, the EPA is taking action to monitor and reduce the risks posed by PFASs. The most recent legislation in the US is primarily the final rule published in April 2023 by the EPA concerning reporting and record-keeping obligations for PFOA and PFOS, aimed at better identifying the use of PFASs in the United States.

In April 2024, the EPA established the first-ever nationwide, legally enforceable National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR). Binding maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) were set for six PFASs: 4.0 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS and 10 ng/L for PFHxS, PFNA, and HFPO-DA. For a mixture of PFAS containing at least two or more of the following components, i.e., PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA and PFBS, it was determined that the sum of the concentration ratios (MCL hazard ratio) must not exceed 1. The EPA also provided scientifically documented maximum contaminant levels (MCLG) based on toxicological and epidemiological studies for the same PFASs: 0 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS and 10 ng/L for PFHxS, PFNA, and HFPO-DA. The established MCL values for PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, and PFBS will apply in all US states from 26 April 2029. If these values are exceeded, water supply systems, i.e., those in breach of federal regulations, will be required to take action as soon as possible to reduce PFAS levels. They will also have to notify users that the drinking water is not sufficiently clean [57].

11. Conclusions and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, critically analyzing their environmental impact, health effects, and regulatory status. Their exceptional chemical stability, which has led to their widespread industrial use for decades, has resulted in widespread environmental contamination due to their resistance to natural degradation. As a result, this serious long-term threat to the environment and human health requires comprehensive action.

This review summarizes recent advances in most key areas of PFAS research, offering a comprehensive perspective that is often missing in the literature. We have outlined the scale of the problem, highlighting gaps in knowledge, such as those concerning the complex effects of PFAS mixtures on human health and emerging short-chain alternatives. Since the complete elimination of PFASs is deemed impossible, an effort must be made toward source reduction. This involves incentivizing the development of safer, equivalent alternatives to PFASs, particularly in critical applications like medicine where their performance is currently unmatched. Research to characterize the toxicity of these newer, unregulated PFASs will help to assess risks and guide future mitigation actions. The toxicological characterization of “new-generation” short-chain PFASs is currently a critical research gap. Meanwhile, the intensive search for and the development of safe substitutes is an absolutely critical task.

Another fundamental challenge is the aforementioned toxicity of mixtures of different PFASs. The literature indicates a limited amount of in vivo and in vitro data on the toxicity of these mixtures. Therefore, it is essential to develop and apply a framework for grouping and assessing the toxicity of mixtures, in particular to better evaluate the dose-additivity approach. Scientific studies place great emphasis on PFOS and PFOA, while there are a huge number of PFASs, many of which remain unexamined. Many scientific studies only address individual PFASs when exploring their impact on human health, but their synergistic effects should also be investigated. Given the multitude of possible combinations, such studies require a lot of time and effort. Research conducted in the field of PFASs is mainly within a single discipline, e.g., analytical chemistry, toxicology, and occupational hygiene, and very rarely studies are interdisciplinary. The approach needs to be changed to a more holistic one in order to better understand the problem.

We also discussed analytical challenges and techniques, as well as the urgent need for the standardization and global monitoring of this group of compounds. PFASs have been studied for many years, but there are still no standardized protocols for sampling, processing, extraction, and ionization. The methods differ in terms of detectability, which makes it difficult to compare these studies correctly. Despite the existence of a huge number of PFASs, the available standards are only a fraction of all PFASs. Despite the increasing number of studies on the determination of PFASs in the environment, the vast majority currently concern water, with less attention paid to biomaterials, soil, sediments, and least of all air. PFAS analysis in soils, sediments, and air is challenged by difficult extractions, severe matrix effects, pervasive laboratory and reagent contamination, ionization and fragmentation variability, and a lack of standards and validated methods. These issues produce compound-dependent biases that hinder comparability and total PFAS mass closure. The scientific community must cooperate globally with government agencies to standardize analytical protocols worldwide in order to harmonize research on PFASs. In the era of developing machine learning, research should be conducted to integrate AI into non-target screening methods, which requires broader interdisciplinary cooperation.

The diversity of analytical methods used in different studies makes it difficult to compare data and fully understand the spread of PFASs.

Many authors also emphasize the need for further research, especially in the workplace, marine environment, and atmosphere, as well as in human biomonitoring, which, by its nature, integrates all sources and routes of exposure.

Most importantly, this review considers occupational exposure to PFASs and discusses recent regulatory changes in the US and EU in detail, highlighting, for example, the lack of harmonized occupational exposure limit values. Legislative proposals should aim not only to regulate the use of PFASs in the future but also to effectively address the problem of compounds that have already been released into the environment over the recent decades. Differences in legal regulations—from strict regulations in some regions to milder ones in others—pose a serious challenge to the international enforcement of laws. These regulatory differences make it difficult to conduct a comprehensive, comparative analysis of policy effectiveness, which in turn contributes to data discrepancies between regions. The harmonization of regulatory frameworks is necessary to reduce the complexity of regulatory compliance and minimize trade friction in international supply chains.

It is also necessary to seek and implement effective methods for removing PFASs from the environment, as conventional treatment methods are insufficient. Reducing the risks associated with PFASs must also be based primarily on prevention and reduction at source, before costly and complex remediation becomes necessary.

There is a real risk of exposure levels being exceeded, which could have serious consequences for health and the environment if PFAS emissions are not reduced. It is therefore necessary to undertake coordinated research efforts and fill the gaps in areas such as the toxicity of substitutes, the identification of innovative destruction technologies, and adaptation to a dynamic regulatory framework, legislation, and public health initiatives.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and the literature review. Resources, writing—original draft preparation and editing—E.D. and P.W.; writing on new regulations, review and editing—M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This task was completed on the basis of the results of research carried out within the scope of the 6th stage of the National Programme “Governmental Programme for Improvement of Safety and Working Conditions”, funded by state services of the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy. Task no. 5.ZS.04. The Central Institute for Labour Protection–National Research Institute is the Programme’s main coordinator.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. All data and citations used within this review are available online.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kannan, K.; Li, Z.-M.; Li, W. Chapter 10 Biomonitoring and health effects of PFAS exposure. In Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances: Occurrence, Toxicity and Remediation of PFAS; Naidu, R., Mallavarapu, M., Liu, Y., Umeh, A., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2025; pp. 399–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. PFAS Explained; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Newland, A.; Khyum, M.; Halamek, J.; Ramkumar, S. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)—Fibrous substrates. TAPPI J. 2023, 22, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunn, H.; Arnold, G.; Körner, W.; Rippen, G.; Steinhäuser, K.G.; Valentin, I. PFAS: Forever chemicals—Persistent, bioaccumulative and mobile. Reviewing the status and the need for their phase-out and remediation of contaminated sites. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CompTox Chemistry Dashboard. PFAS. 2025. Available online: https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical-lists/PFASSTRUCT (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Leung, S.C.E.; Wanninayake, D.; Chen, D.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Li, Q. Physicochemical properties and interactions of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—Challenges and opportunities in sensing and remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 166764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Zhang, J.; Thiessen, P.A.; Chirsir, P.; Kondic, T.; Bolton, E.E. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in PubChem: 7 Million and Growing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 16918–16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Reconciling Terminology of the Universe of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Recommendations and Practical Guidance; OECD Series on Risk Management of Chemicals, No. 61; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangri, S.; Kumari, R. Deteriorating women’s health due to rising exposure to per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A review. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 86, 01018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Choi, K. Perfluoroalkyl substances exposure and thyroid hormones in humans: Epidemiological observations and implications. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 22, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Xiao, F.; Shen, C.; Chen, J.; Park, C.M.; Sun, Y.; Flury, M.; Wang, D. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Subsurface Environments: Occurrence, Fate, Transport, and Research Prospect. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shao, Y.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lam, P.K.S.; Ruan, Y. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the marine environment: An overview and prospects. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 216, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto-Rodrigues, M.C.; Monteiro-Neto, J.R.; Teglas, T.; Toborek, M.; Quinete, N.S.; Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Adesse, D. Early-life exposure to PCBs and PFAS exerts negative effects on the developing central nervous system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 485, 136832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozben, T.; Fragão-Marques, M.; Tomasi, A. A comprehensive review on PFAS including survey results from the EFLM Member Societies. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2024, 62, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisci, S.; Suri, R. Occurrence and removal of poly/perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 84, 3442–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.-M.; Chen, D.; Han, F.-J.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, L.; Lu, X.; Wang, F. A short review on human exposure to and tissue distribution of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnabuchi, M.A.; Duru, C.E. PFAS toxicity and female reproductive health: A review of the evidence and current state of knowledge. Substantia 2025, 9, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Wang, Z. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2345–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]