Abstract

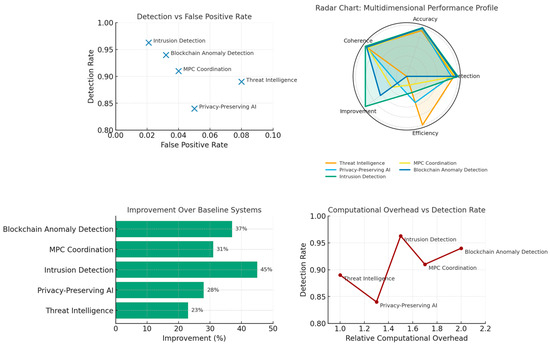

Current generative AI systems, despite extraordinary progress, face fundamental limitations in temporal reasoning, contextual understanding, and ethical decision-making. These systems process information statistically without authentic comprehension of experiential time or intentional context, limiting their applicability in security-critical domains where reasoning about past experiences, present situations, and future implications is essential. We present Phase 3 of the Sophimatics framework: Super Time-Cognitive Neural Networks (STCNNs), which address these limitations through complex-time representation T ∈ ℂ where chronological time (Re(T)) integrates with experiential dimensions of memory (Im(T) < 0), present awareness (Im(T) ≈ 0), and imagination (Im(T) > 0). The STCNN architecture implements philosophical constraints through geometric parameters α and β that bound memory accessibility and creative projection, enabling neural systems to perform temporal-philosophical reasoning while maintaining computational tractability. We demonstrate STCNN’s effectiveness across five security-critical applications: threat intelligence (AUC 0.94, 1.8 s anticipation), privacy-preserving AI (84% utility at ε = 1.0), intrusion detection (96.3% detection, 2.1% false positives), secure multi-party computation (ethical compliance 0.93), and blockchain anomaly detection (94% detection, 3.2% false positives). Empirical evaluation shows 23–45% improvement over baseline systems while maintaining temporal coherence > 0.9, demonstrating that integration of temporal-philosophical reasoning with neural architectures enables AI systems to reason about security threats through simultaneous processing of historical patterns, current contexts, and projected risks.

1. Introduction

Contemporary artificial intelligence faces three fundamental challenges that limit its application in security-critical domains. First, current systems lack genuine temporal reasoning capabilities: while neural architectures like RNNs and Transformers process sequential data, they treat all temporal positions as uniformly accessible and fail to capture the qualitative differences between memory, present awareness, and anticipatory imagination that characterize human temporal cognition. Second, AI systems demonstrate insufficient contextual understanding, processing information through statistical patterns without comprehending the intentional and situational contexts that determine meaning and appropriate response. Third, existing approaches struggle to integrate ethical reasoning with technical decision-making, particularly in security contexts where privacy preservation, proportionality of response, and accountability must coexist with threat detection and mitigation. These limitations become critical when AI systems must reason about temporal sequences of security events, anticipate evolving threats while respecting privacy constraints, and make ethically grounded decisions under uncertainty.

Generative AI marks the latest phase in computing’s evolution yet remains statistically grounded and ethically debated [1]. Transdisciplinary perspectives call for resilient, context-aware systems uniting computation and philosophy [2,3]. Sophimatics merges sophía and informatics into post-generative wisdom, integrating insights from classical to modern thought [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], with theoretical bases in [31,32,33].

Understanding not only what is statistically plausible or probable, responding in a contextual manner, recognizing intent, understanding time from a human-experiential perspective, and recognizing value and ethical systems are the new frontiers and key themes of post-generative artificial intelligence. Traditional neural networks, while effective in pattern recognition and statistical learning, are theoretically incapable of achieving sufficient temporal depth or conceptual penetration for reflection, awareness, and cognition. On the other hand, while formal philosophical systems are conceptually well developed, they usually become computationally intractable when it comes to AI implementations.

The Sophimatics framework [31,32,33] integrates philosophy and computation through three phases: (1) dynamic philosophical categories defined by angular parameters α (memory) and β (imagination); (2) conceptual mappings translating abstract notions into computational form; and (3) synthesis within the Super Time Cognitive Neural Network (STCNN). STCNNs extend neural computation onto a two-dimensional space–time manifold where complex time (T = a + ib) models both chronological and cognitive dimensions, reflecting Augustine’s triadic temporality—memory, attention, and expectation. Parameters α and β act as architectural constraints controlling information flow between memory and imagination, ensuring convergence and coherence. Specialized modules—temporal encoding, angular accessibility, and synthesis networks—enable temporal reasoning akin to conscious processing. Unlike RNNs or Transformers, STCNNs encode temporal geometry and intentionality, allowing contextual, ethical, and creative reasoning that unifies past, present, and future representations within a single adaptive computational architecture.

This article offers a mathematical framework for the integration of STCNN, architectural description, validation strategies, and application considerations. The framework should be usable with the current deep learning infrastructure while introducing the temporal complexity required for philosophical AI applications.

This work makes four primary contributions: (1) Mathematical foundations for complex-time neural processing with geometric constraints derived from philosophical analysis of memory and imagination; (2) STCNN architecture specification integrating temporal encoding, angular accessibility, and synthesis mechanisms within trainable neural networks; (3) validation across five security-critical applications demonstrating 23–45% improvement over baselines with temporal coherence > 0.9; (4) empirical demonstration that temporal-philosophical reasoning enhances security AI through simultaneous processing of historical patterns, current context, and projected threats while maintaining ethical constraints.

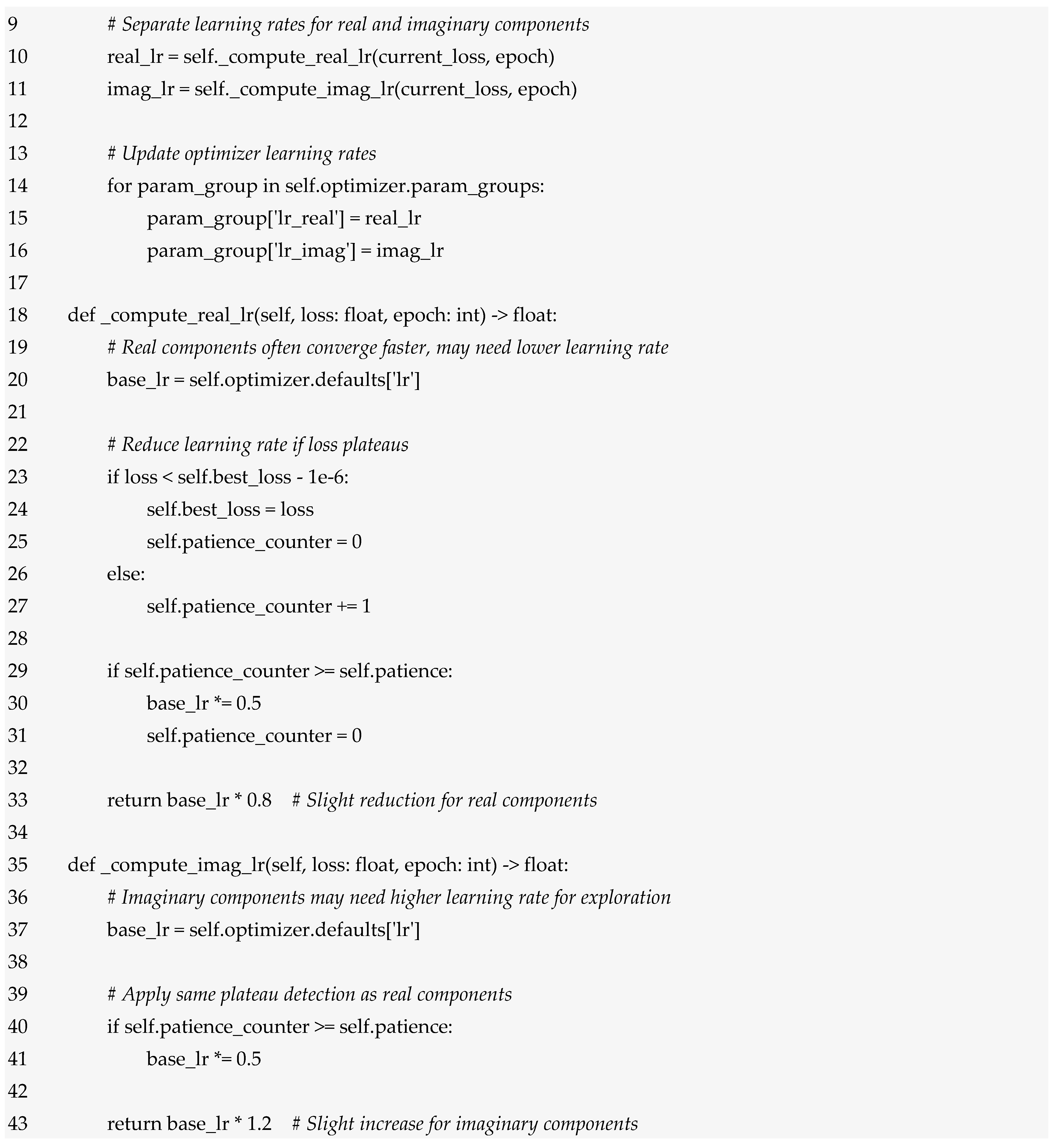

The relevance of temporal reasoning to security becomes particularly evident when we consider that cybersecurity fundamentally involves reasoning about sequences of events unfolding across time. Traditional security systems operate largely in reactive modes, detecting threats after they manifest rather than anticipating them through sophisticated temporal analysis. The STCNN framework’s ability to process information simultaneously across memory (historical attack patterns), present awareness (current network state), and imagination (projected threats) enables a qualitative shift from post-incident response to anticipatory defence. Moreover, the integration of ethical reasoning with temporal analysis addresses critical security-privacy tensions that purely technical approaches cannot resolve, such as the balance between comprehensive monitoring and privacy preservation, or the proportionality of security measures to actual threats. These capabilities prove essential in modern security contexts where threats evolve rapidly, adversaries actively adapt to defensive measures, and regulatory frameworks impose ethical constraints on data processing.

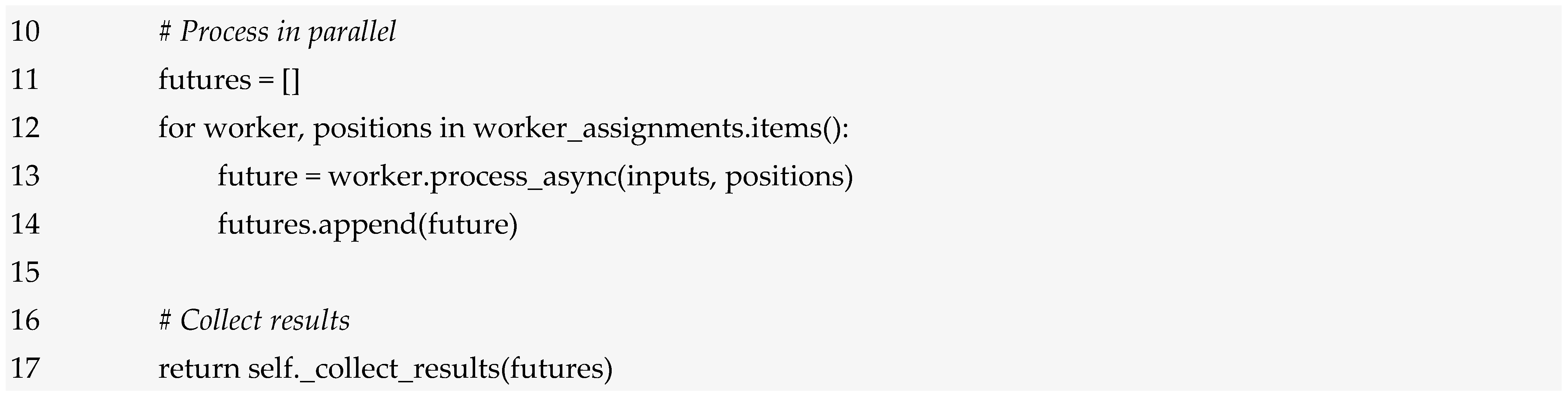

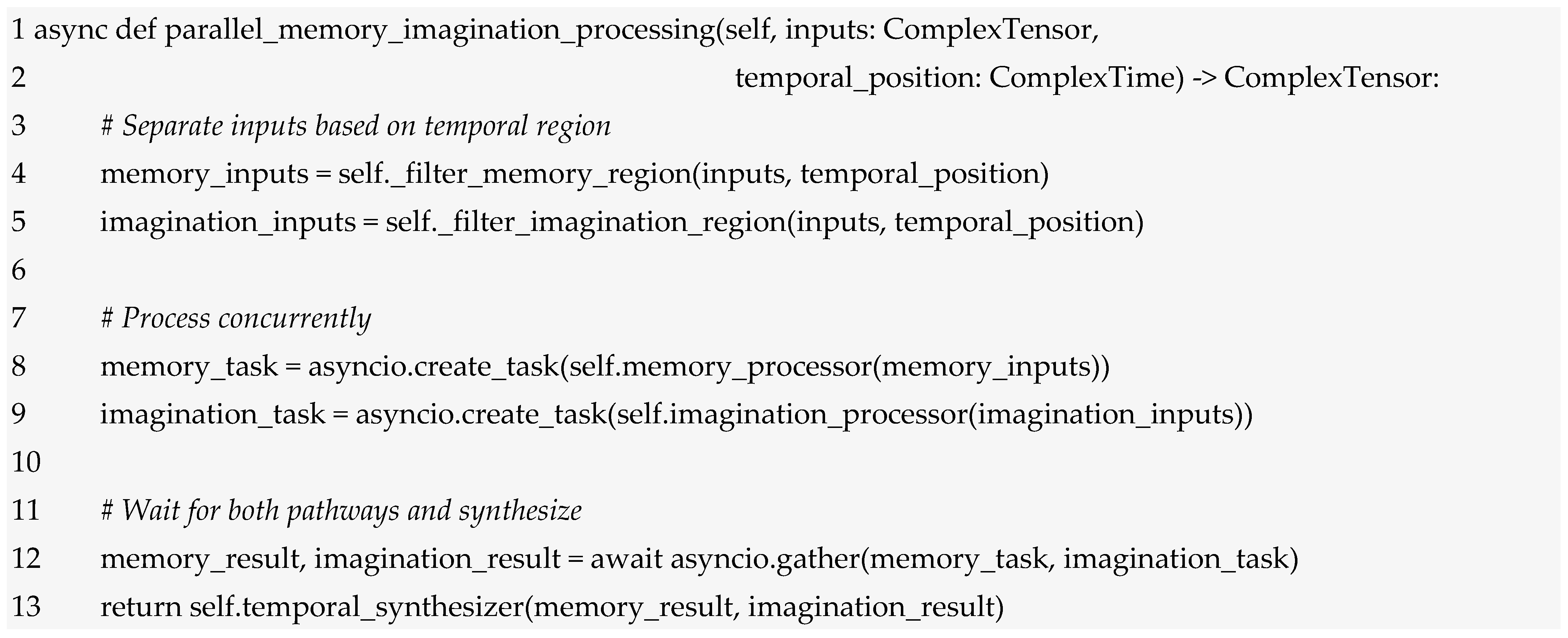

The work is organised as follows. Section 2 is dedicated to related works, while Section 3 focuses on the materials and methods with the six level (or phase) for realising Sophimatic Framework. In Section 4 we find a specific model capable of accommodating elements of thought from the philosophy of all times that are relevant to AI. Indeed, in this Section we find the Theoretical Foundation for Complex-Time Neural Processing (STCNN). Section 5 introduces the Architecture, while Section 6 shows some relevant uses cases. Then, Section 7 analyses the results and perspectives. Finally, Section 8 presents the conclusions.

2. Related Works

2.1. Philosophical Foundations and Evolution of AI

Generative artificial intelligence represents the latest stage in a long evolution: from rule-based symbolism to complex neural networks. Despite progress, our knowledge of it remains statistical; ethicists and philosophers highlight risks of irrationality, bias and ambiguous responsibility [1]. Transdisciplinary analyses suggest that resilient AI should integrate computational architecture and centuries of reflection on consciousness and intentionality [2], while also valuing situated intelligence [3]. We therefore propose Sophimatics, a synthesis of sophía and informatics: a paradigm that blends extraction and interpretation for post-generative computational wisdom. Based on the main themes of thought from the pre-Socratics to the contemporary world, with references to categories, forms and logic, our approach draws on Socratic dialectics and the distinction between the sensible world and ideas, and integrates medieval, Renaissance and Enlightenment contributions that have shaped symbolic models, ontologies and principles of parsimony [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The legacy of modern figures, from Nietzsche to Husserl, Heidegger, Wittgenstein and Foucault, invites us to consider creativity, intentionality, contextuality and power, offering insights for self-modifying and critically aware algorithms [4,5,6,7,12,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. The result is an AI that recognises the limits of statistical learning, values embodiment and context, and incorporates ethics and hermeneutics. Specifically, reference [31] introduces Sophimatics as an emerging discipline that aims to make a specific contribution to post-generative AI, with particular reference to the use of philosophical thinking as a basis for understanding, contextualisation, analysis of experiential time, and understanding of intentionality. After introducing Sophimatics the topic of philosophical categories is considered in [32] and the mapping between concepts and algorithms is shown in [33]. The present work deals with the central topic of algorithmic cognition, based on a Super Time Cognitive Neural Network (STCNN), which we will analyse in detail in terms of concept, algorithm and application.

Contemporary artificial intelligence research operates at the intersection of multiple paradigms: deep learning architectures achieving unprecedented pattern recognition capabilities, neural-symbolic systems integrating logical reasoning with statistical learning, and increasingly sophisticated approaches to temporal modelling and ethical AI. Recent advances demonstrate both remarkable progress and persistent limitations. Transformer architectures revolutionized sequence processing through attention mechanisms yet struggle with genuine temporal reasoning that distinguishes memory, present awareness, and anticipatory projection. Complex-valued neural networks extend representational capacity without addressing philosophical constraints on temporal accessibility. Security-focused AI prioritizes detection accuracy over temporal coherence and integrated ethical reasoning.

This landscape motivates our approach: integrating philosophical foundations of temporal cognition with neural computation to address limitations in current state-of-the-art systems. Philosophical foundations for AI have been established through work on consciousness [34], trustworthiness [17], embodied cognition [35], and neural-symbolic reasoning [36]. These contributions establish that AI research must integrate computational architecture with philosophical questions about thought, intentionality, and ethics. However, existing work lacks explicit temporal-philosophical frameworks for security-critical applications. In [37], COG is developed, a humanoid robot that serves both as a theopolitical challenge to human exceptionalism and as an invitation to think differently about the dialogue between technology and spirituality. In [38], intentionality is rethought in situations involving algorithmic agents, indicating that the rise of artificial systems requires a revision of classical theories of mental content. Taken collectively, these contributions reveal that AI research is much more than a technical issue; it is deeply intertwined with philosophical questions concerning the nature of thought, action, and ethics.

2.2. Context-Aware AI, Ethics, and Temporal Reasoning

Research on context-aware AI emphasizes situated reasoning [12,39] and temporal perception models [40], yet lacks integration with neural architectures for security applications where context determines threat interpretation.

AI ethics research addresses design virtues [41], anthropological perspectives [42], layered assessment [13], and contextual signals [21], but typically treats ethics as external constraints rather than integrated reasoning components.

Another body of work addresses the metaphysical and cognitive foundations. Reference [43] demonstrates that formal ontologies facilitate this conversation between computer science and metaphysics, as well as suggesting how cross-fertilization between the two is possible. In [7], an idea for a “mathematical metaphysics” is presented, involving a computational ontology that combines logical form with metaphysical structure. In [44], it is warned that endowing artificial systems with intentionality can give rise to erroneous notions for agents. In contrast, ref. [45] argues that any serious attempt to model AI must still be guided by cognitive neuroscience if intentionality is to be taken seriously. The fact that these views do not coincide suggests that AI research can hope to overcome the superficial appearance of complex intelligences with new approaches and that, in order to obtain a truly in-depth explanation, it must be rooted in a more substantial cognitive model (and here, with Sophimatics, we have used the thinking inherited over thousands of years from philosophers).

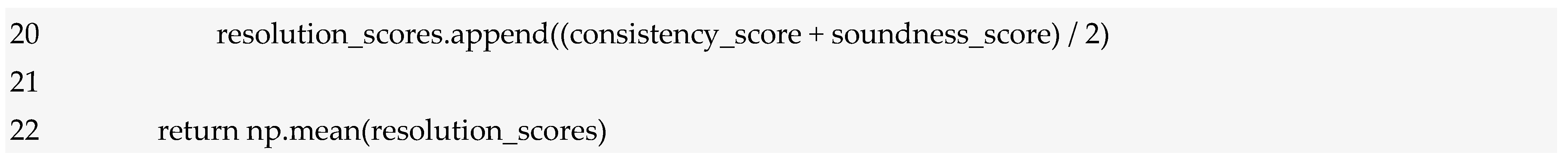

2.3. Sociocultural Implications and Security Applications

The implications of AI for society and culture must also be taken into account. In [22], analogies are drawn between the philosophy of science and cognitive science, and it is suggested that AI uses heuristics similar to those found in the human mind (and in rationality). Algorithmic microtemporality is questioned in [46], revealing how the user experience is encoded at the very heart of computation. In [30], AI is characterized as terra incognita and the sense of “contextual integrity” and “no-go zones” of ethical concerns related to new technologies. In [24], distributed and democratized frameworks for learning institutions are presented and new ways for intelligent systems to be co-creators in common spaces are proposed. In [47], temporality is examined as an intrinsic structuring principle of research that informs the forms in which AI knowledge must be developed and applied. Reference [15] provides an overview of AI in education, focusing in particular on contextualized and ethically integrated frameworks. The investigations highlight that AI is not independent of its sociopolitical context and gain further support for the sophimatic agenda, which consists of reintroducing humans into the technological conversation and as participants in it.

Finally, contributions on temporal reasoning have provided insights of direct relevance for Sophimatics. In [48], early reflections anticipated the incorporation of computational notions into philosophical analysis. In [4], a comprehensive introduction is offered, linking the philosophical underpinnings of AI with technical developments. In [49], formal systems are extended to address temporal relations explicitly. In [9], a survey of temporal reasoning techniques is provided, covering logics, interval algebras, and constraint networks. In [50], the framework of “contextual memory intelligence” is advanced, emphasizing the mutual dependence of human and machine cognition, a perspective consistent with the sophimatic approach to memory and context. In [51], the boundaries of digital metaphysics are interrogated, asking to what extent computational simulations can or cannot substitute for metaphysical reality. In [52], interpretability in deep learning is addressed through the visualization of temporal trajectories. In [53], it is argued that AI systems must be conceived as intentional and hermeneutic agents if they are to operate with genuine autonomy. When viewed together, these works provide the intellectual background against which Sophimatics positions itself, integrating temporality, context, simulation, and intentionality into the design of advanced artificial intelligence.

The intersection of artificial intelligence with security and privacy has generated substantial research addressing adversarial robustness, privacy-preserving machine learning, and temporal pattern recognition in cybersecurity contexts. In [54] the authors demonstrated that neural networks exhibit surprising vulnerability to adversarial perturbations, raising fundamental questions about the reliability of AI in security-critical applications where adversaries actively manipulate inputs. The development of differential privacy in [55] provided formal foundations for privacy-preserving data analysis, with subsequent work in [56] extending these techniques to deep learning. However, existing privacy-preserving mechanisms generally treat time as a simple sequence rather than engaging with the philosophical and experiential dimensions of temporality that STCNN addresses. In cybersecurity applications, the authors in [57] identified fundamental limitations of machine learning for intrusion detection stemming from the assumption of a closed world where training and deployment distributions remain stable—an assumption violated by adversaries who deliberately shift distributions to evade detection. Temporal pattern recognition in security contexts has largely focused on sequence modelling through recurrent networks or temporal convolution, without engaging the philosophical questions about memory, imagination, and experiential time that inform the STCNN framework. The integration of secure multi-party computation protocols, as pioneered in [58], with modern machine learning creates new challenges around reasoning about privacy and security properties across temporal dimensions. The STCNN framework addresses these challenges through its unified temporal-philosophical approach, enabling security systems that reason about historical precedent, current threats, and future implications while maintaining formal privacy guarantees and ethical constraints.

Existing approaches fail to address these challenges comprehensively. Traditional neural networks (RNNs, LSTMs, GRUs) process temporal sequences linearly without explicit mechanisms for distinguishing memory, attention, and projection [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Recent advances in temporal modeling include Temporal Fusion Transformers [59] for multi-horizon forecasting and Neural ODEs [60] for continuous-time dynamics, yet these approaches lack the philosophical-geometric constraints necessary for experiential temporal reasoning. Complex-valued neural networks [61] extend representation capacity but do not impose memory-imagination accessibility bounds. Transformer architectures enable parallel attention but treat all temporal positions equally, lacking geometric constraints necessary for motivated temporal reasoning. Neural-symbolic systems integrate logic with learning but typically operate in static temporal frameworks. Security-focused AI prioritizes detection accuracy over temporal coherence and ethical reasoning. This gap between computational capability and philosophical-temporal reasoning motivates our approach.

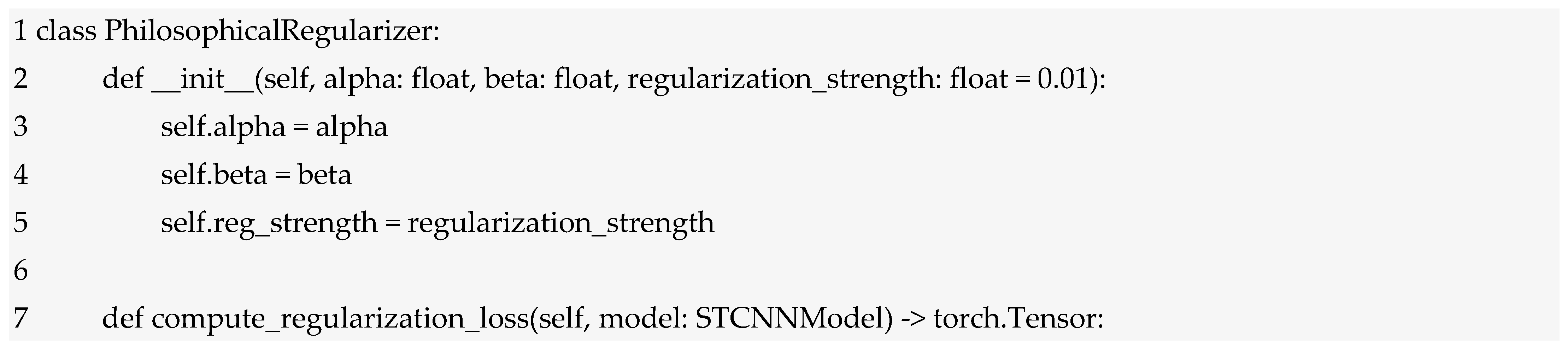

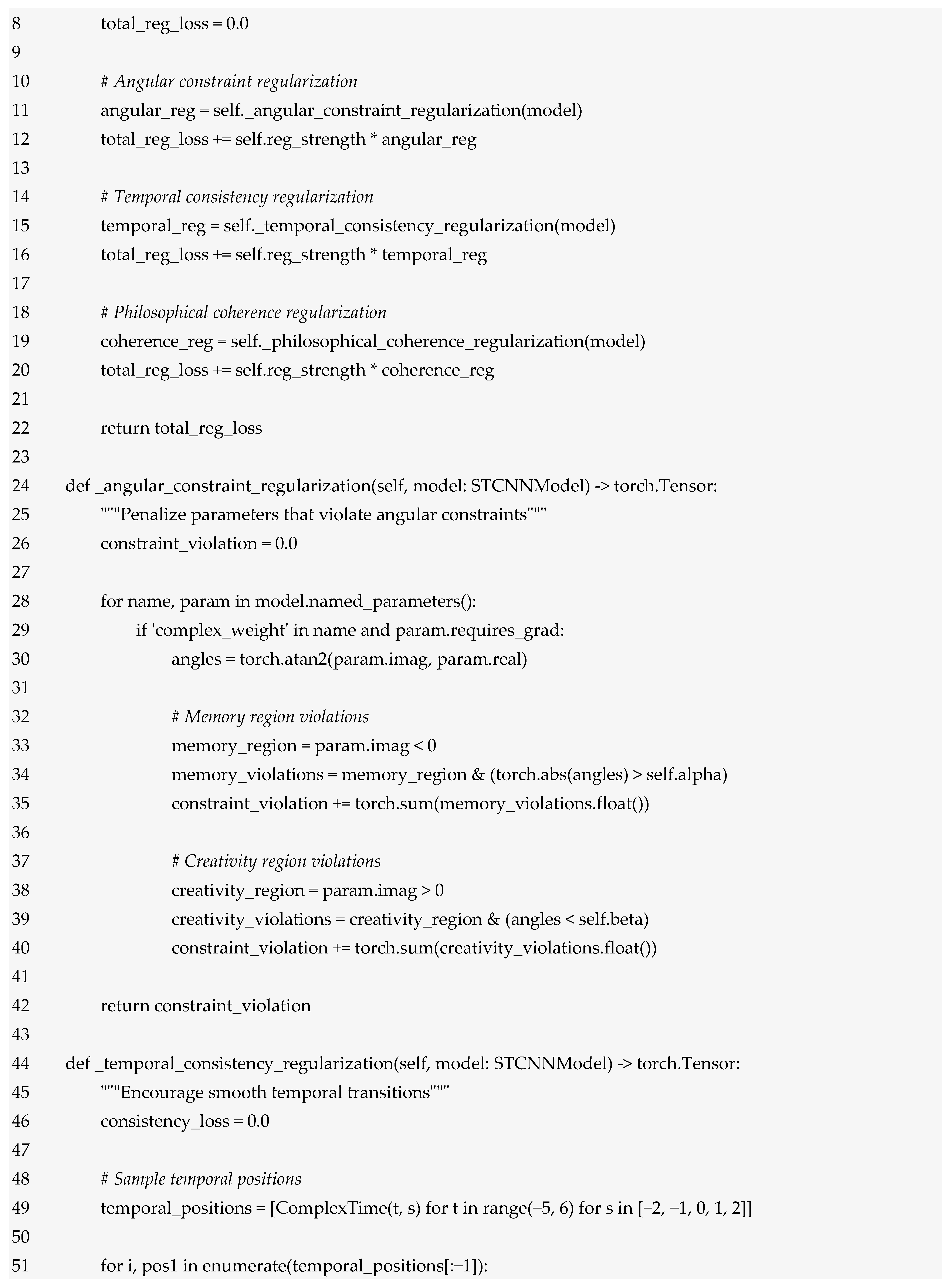

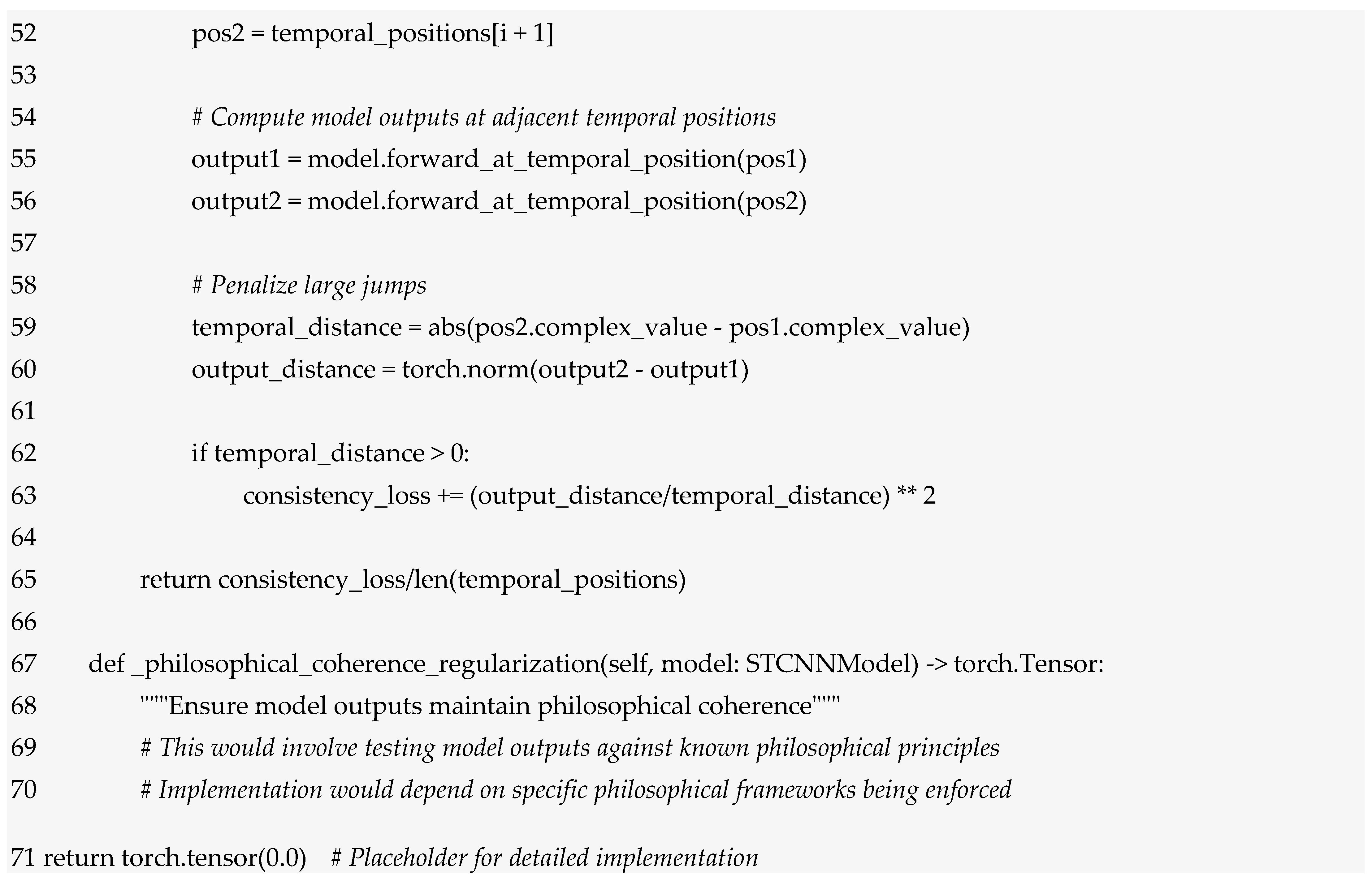

3. Materials and Methods

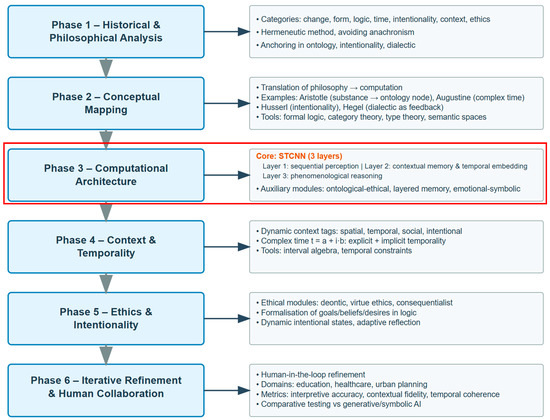

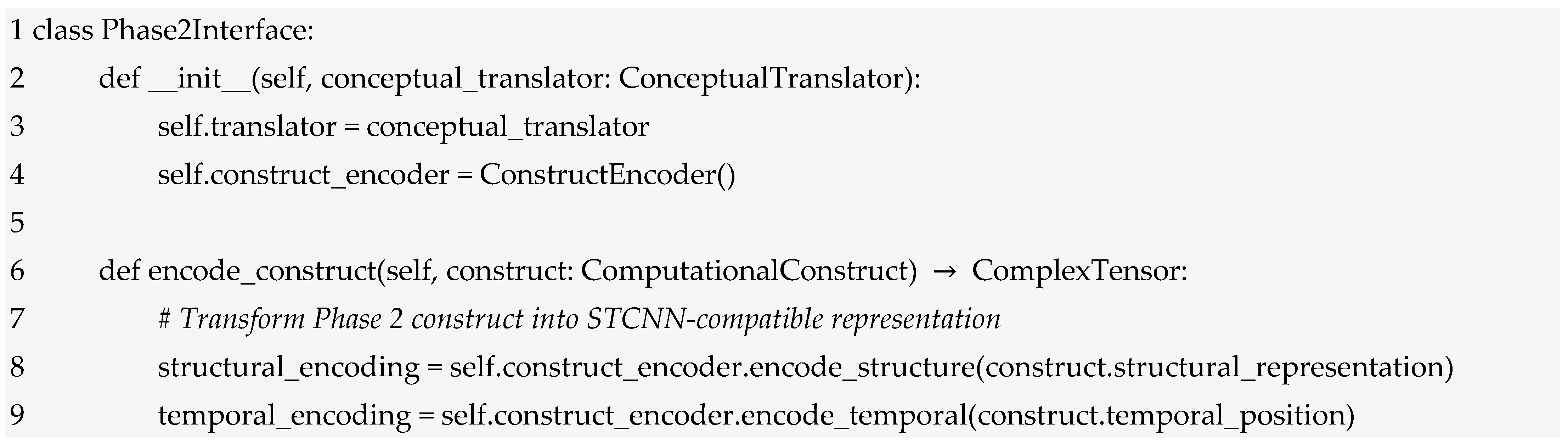

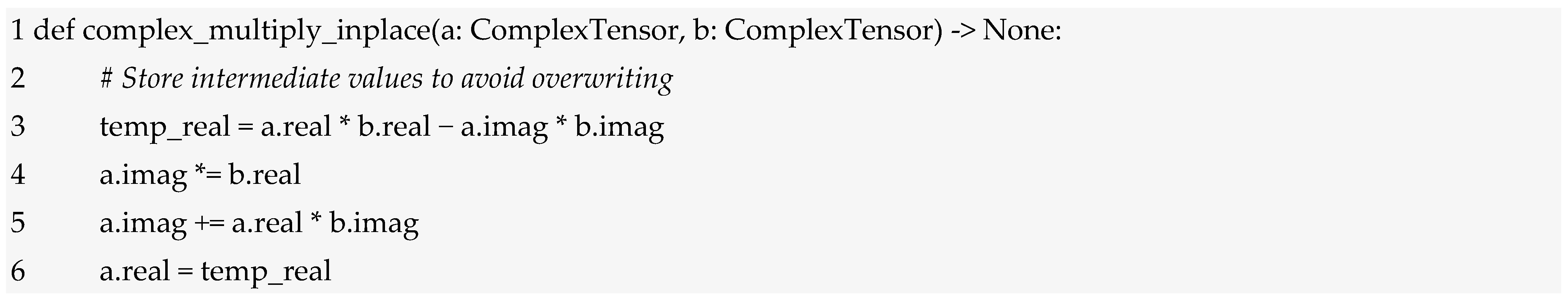

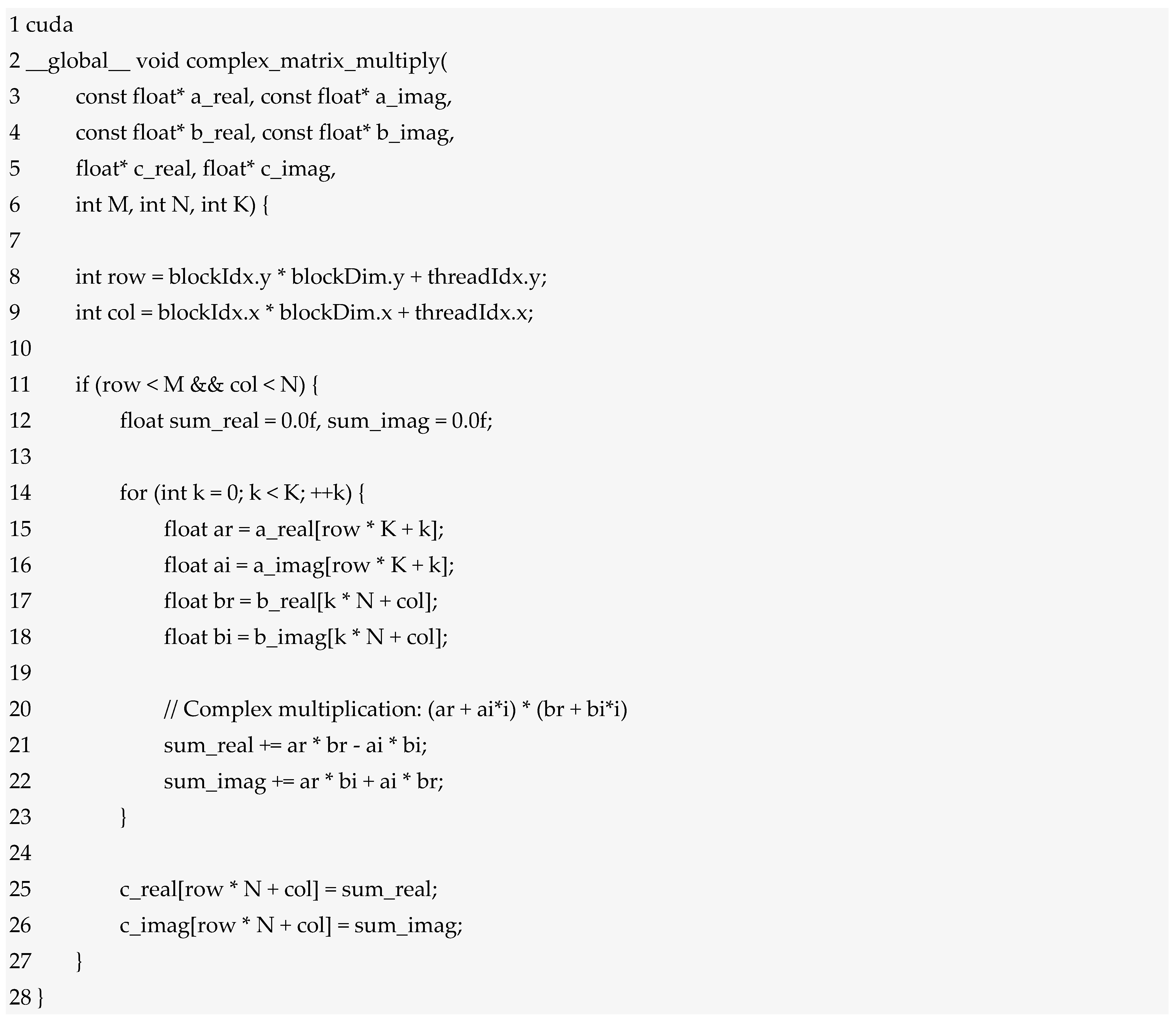

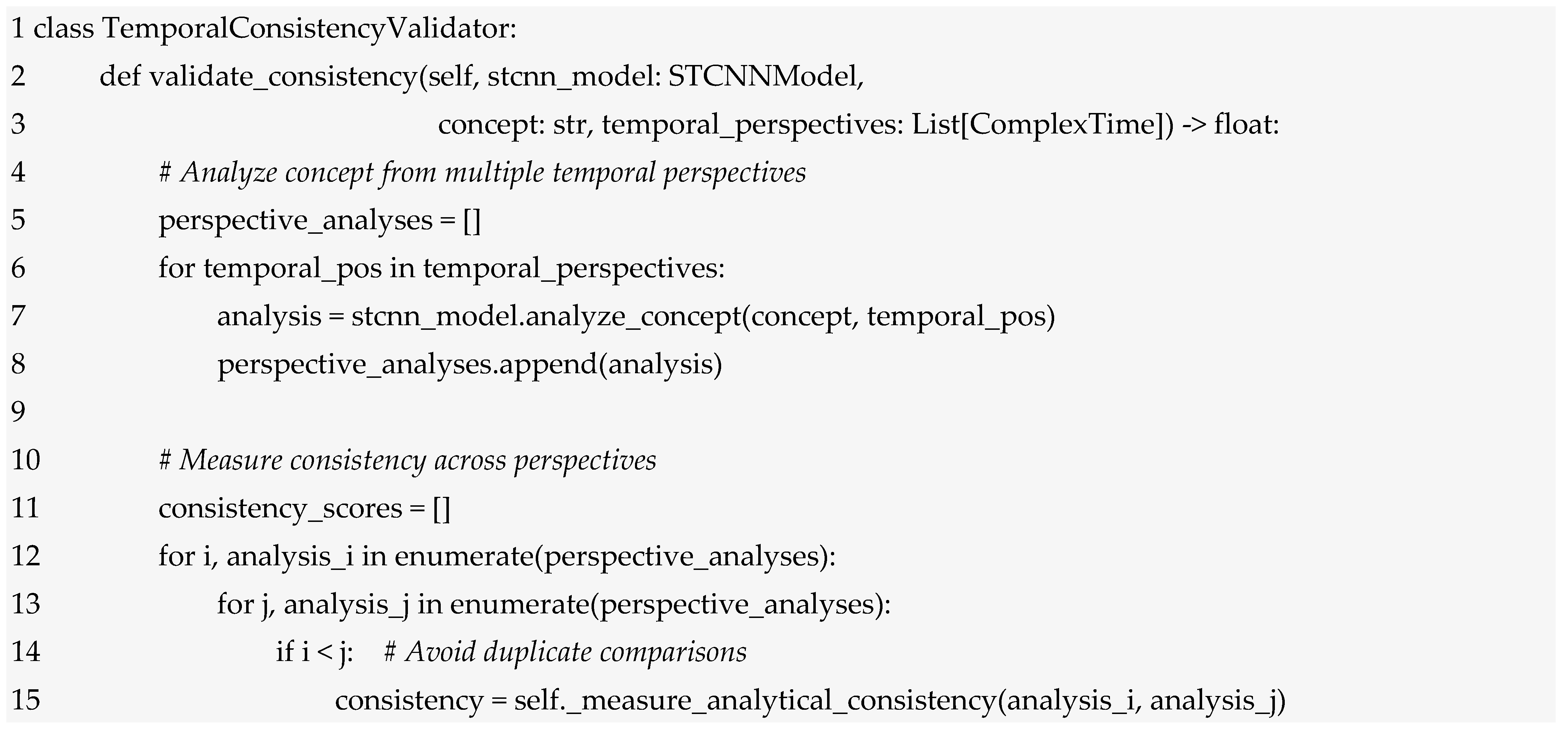

Figure 1 is a conceptual architecture of the hybrid computational architecture of Sophimatics. The methodological structure of Sophimatics consists of six Phases of development of the framework), starting from philosophical thought (categories) and ending with computable expressions.

Figure 1.

The diagram illustrates a vertical flow of six sequential phases; each paired with explanatory blocks. Phase 1 grounds the system in key philosophical categories. Phase 2 maps them into computational constructs. Phase 3 introduces the STCNN architecture with symbolic, ethical, and memory modules. Phase 4 models context and complex temporality. Phase 5 integrates ethical reasoning with intentional states. Phase 6 emphasises iterative refinement through human collaboration, supported by metrics for accuracy, contextual fidelity, temporal coherence, and ethical consistency.

3.1. First Phase

The first phase is a very detailed analysis of concepts. This analysis ranges from ancient philosophy to the present day. This hermeneutics is not anachronistic but takes into account the internal consistency of each philosophical tradition with respect to its time. This provides Sophimatics with a robust foundation based on a dynamic ontology, the analysis of intentionality and dialectical logic. The result is a process of formalisation of thought throughout the entire history of human thought, represented by philosophy.

3.2. Second Phase

Phase 2 creates the conceptual mapping. In this phase, abstract philosophical concepts are transformed into formal entities that can be processed by a computer. For example, Aristotle’s conception of the concept of substance becomes a node in an ontology; Augustine’s conception of time, as T = a + i·b, which includes elements of chronology but also of experience; Husserl’s intentionality is documented as structures linking mental states and objective states; and Hegel’s dialectic is executed as a feedback loop that iterates hypotheses. The translation is based on formal logic, category theory and type theory, so that conceptual integrity can be maintained and yet represented in such a way that it can be executed by a computer. At this phase, therefore, there is a transition to models of multidimensional semantic spaces capable of representing ambiguous and overlapping interpretations. If the suggested concepts are encoded in a high-dimensional space, the indistinguishability between concepts in interpretation (related to normalisation) can be effectively resolved, as strong contexts can be incorporated.

3.3. Third Phase

The third phase is the subject of this article; this phase is the realisation of the above constructs for the design of a hybrid computational architecture. Sophimatics uses a multi-level architecture with Israel Supervised modelling (i.e., a supervised learning model conceived within a logical-philosophical framework, where data labelling is interpreted as a form of epistemic guidance). The architecture we introduce here can be called Super Temporal Cognitive Neural Network (STCNN), which, as we will see in more detail later, has three layers. The first layer performs sequential perception and pattern recognition, similar to an encoder that transforms sensory inputs into a latent representation. A second layer includes contextual memory and temporal embedding. It represents episodic, semantic and intentional memories and is able to integrate context over time through its recurrent mechanisms. This layer models the dynamic evolution of context, which means that the system remembers what, in what context and why something is experienced. The third layer performs phenomenological reasoning and combines symbolic representations with activations in the neural network to generate explanations and justifications. It is the seat of a semantic dialogue engine that reasons through internal dialogue based on dialectical rules. To these levels we add three auxiliary modules: an ontological-ethical module that incorporates deontic logic and virtue ethics; a contextual memory and awareness module that employs memory at different levels (episodic, semantic, intentional) and contextual resonance; and an emotional-symbolic module that determines the qualitative values of information. It is the combination of these components that adds perception, memory, reasoning and action to the sophimatic system.

3.4. Fourth Phase

The fourth Phase concerns interpretation and relates more specifically to context and temporality. Concepts are not static entities, but rather dynamic and multidimensional entities that are directly shaped by interaction. Based on the paradigm of contextual reasoning, each item of knowledge is annotated with a contextual label that describes spatial, temporal, social and intentional information. The system stores various contexts and can modify or combine them. Time is represented as a variable represented by a complex number; the real part corresponds to chronological time and the imaginary part to implicit meaning or subjective experience. This model allows the system to predict future events and understand their importance, capturing not only explicit temporality but also implicit temporality. The complex temporal model mentioned above not only allows temporal reasoning about durations, sequences and concurrences of activities, but also about interval algebras and temporal constraints. These formalisms allow an artificial agent to reason about time and act accordingly.

3.5. Fifth Phase

Ethicality and intentionality are the fundamental elements addressed by the fifth Phase. Behavioural reasoning modules rooted in deontic, virtuous and consequentialist ethics are based on principles of ex ante evaluation of acts. A level of deontic logic represents obligations and prohibitions, a virtuous ethics module evaluates actions based on character and prosperity, while a consequentialist module judges results. These ethical judgements are linked to the intentional attitudes (goals, beliefs, desires) of the agent of the behaviour, which is modelled by first-order formulas (i.e., the syntactic units of predicate logic, which allow relations on objects to be expressed and formal reasoning to be carried out in a much more expressive way than propositional logic). Intentions are not fixed but develop during interaction and are dynamically created, deleted and updated through dialogue with ethical modules. This development will enable the agent to explain the reasons for their choices and to modify their motivation and behaviour to conform to accepted norms of behaviour.

3.6. Sixth Phase

The sixth Phase focuses on an iterative process and on working with people. Sophimatics adopts a human-in-the-loop methodology in which philosophers, subject matter experts, scientists and technicians collaborate to improve the architecture.

In [31,32,33], prototypes and use cases are developed in contextually and ethically sensitive fields, such as education, healthcare, environmental and energy planning, etc. The evaluation criteria are interpretative correctness, contextual consistency, temporal consistency and ethical consistency. The comparative system analyses sophimatic performance against generative and symbolic reference systems. The results of this analysis therefore encouraged the present work, which required a significant formal and conceptual effort even before the technological solution—described later in the section on the infrastructure—was developed.

4. Theoretical Foundation for Complex-Time Neural Processing (STCNN)

4.1. Complex Temporal Space

The Super Time-Cognitive Neural Network operates within a complex temporal space T ∈ ℂ, fundamentally extending traditional neural computation beyond real-valued time processing. The mathematical foundation begins with the definition of complex temporal coordinates that serve as the computational substrate for all STCNN operations.

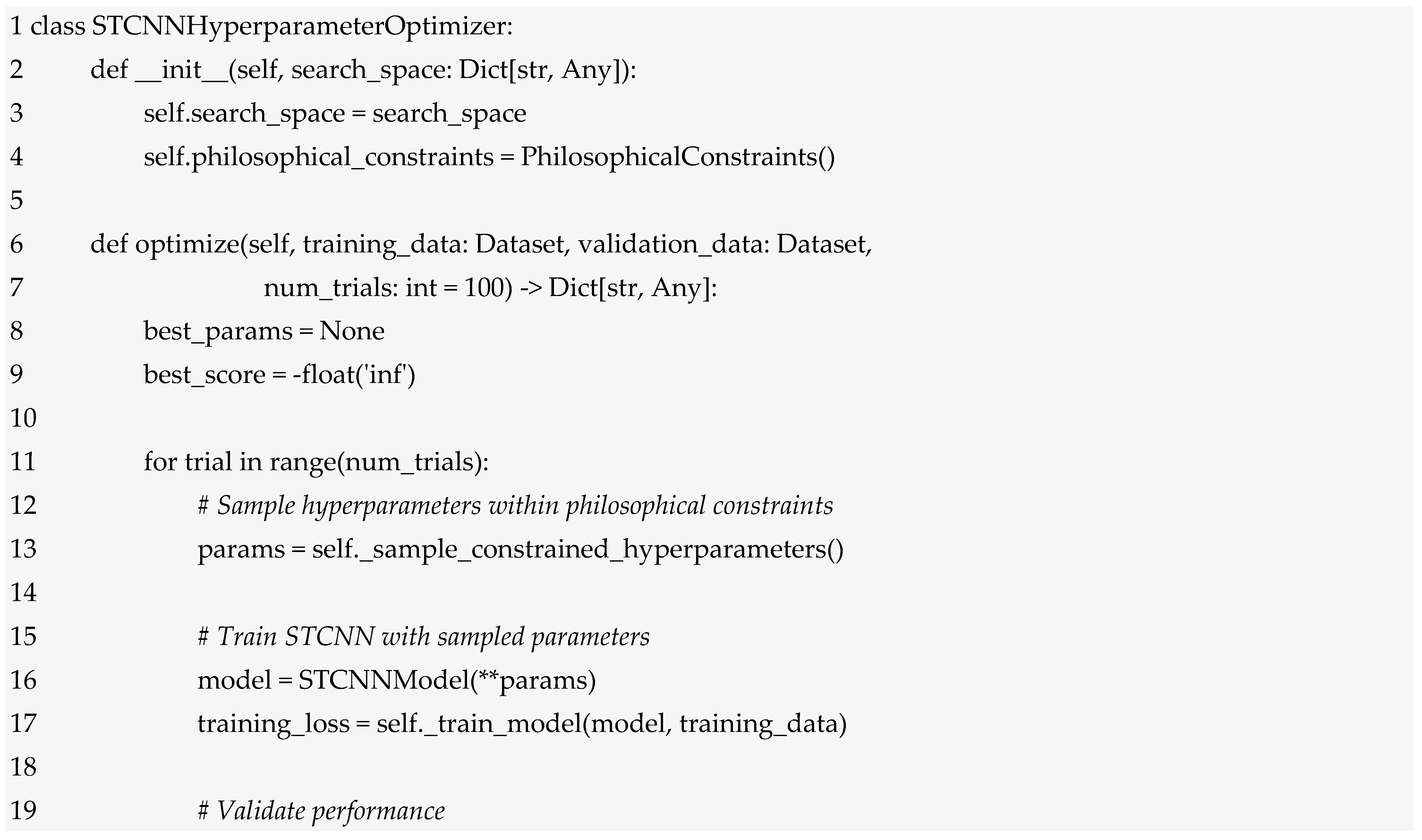

Here in Table 1, we summarize the mathematical notation used in what follows.

Table 1.

Mathematical Notation.

Each neural state in an STCNN is represented as a complex-valued vector , where the temporal subscript t itself belongs to the complex domain. This representation enables simultaneous processing of multiple temporal perspectives within a single computational framework. The fundamental state equation governing STCNN dynamics is:

where represents the core computational principle of STCNNs, integrating spatial, temporal, and cognitive processing within a unified mathematical framework. Each component serves a specific function in the complex-time processing paradigm. The spatial weight matrix governs traditional feedforward connections between layers, similar to conventional neural networks but extended to complex-valued operations. These weights process information within the current temporal position, handling spatial patterns and immediate relationships between neural units. The complex-valued nature of these weights enables the network to maintain separate processing pathways for real and imaginary temporal components. The temporal recurrence matrix captures dependencies across chronological time through the parameter Δa ∈ , which represents the chronological time step. The term connects the current state with previous states along the real temporal axis, enabling the network to maintain continuity with historical information while processing current inputs. The cognitive function : represents the most innovative aspect of STCNN architecture, processing information from experiential temporal dimensions. The parameter Δb ∈ ℝ can be positive (accessing imagination) or negative (accessing memory), allowing the network to retrieve information from different experiential temporal regions. The cognitive function applies transformations that respect the philosophical constraints governing memory and imagination access. The imaginary unit i multiplying the cognitive term ensures that cognitive processing contributes to the imaginary component of the neural state, maintaining the mathematical separation between chronological and experiential temporal processing. This separation is crucial for preserving the geometric structure of complex-time reasoning. The bias vector provides baseline activations for each neural unit, potentially incorporating temporal positioning information that helps the network maintain awareness of its current location within complex-time space. The activation function must be carefully chosen to preserve the complex-time structure while enabling nonlinear processing.

As an example, let us consider Security Monitoring. Indeed, consider a network intrusion detection system processing traffic at time t = 5 + 2i, representing 5 min of chronological time with imaginary component 2i indicating moderate memory depth (approximately 2 min into historical context). The neural state = [0.8 + 0.3i, −0.2 + 0.6i, 0.5 − 0.1i, …] encodes current packet features in real components (0.8, −0.2, 0.5 representing normalized packet sizes) while imaginary components (0.3i, 0.6i, −0.1i) maintain temporal context about traffic patterns. The spatial weight matrix processes immediate packet features, detecting current anomalies. The temporal recurrence matrix connects to the previous state at t − Δa = 4.5 + 2i (30 s prior), preserving short-term traffic dynamics. The cognitive function retrieves relevant attack signatures from deeper memory at t − Δb = 5 + 1i (1 min historical context), enabling the network to recognize multi-stage attacks that unfold over time. The synthesis of these components allows simultaneous analysis of current suspicious packets, recent traffic patterns, and historical attack methodologies.

4.2. Activation Functions and Angular Accessibility

Common choices include the complex-valued extensions of traditional activation functions:

This complex activation function (usually named modReLU activation) preserves the phase information of complex numbers while applying nonlinearity to their magnitudes. The phase preservation is crucial for maintaining temporal directional information within the complex plane.

The integration of angular parameters α and β from Level 1 and 2 into the STCNN architecture requires careful mathematical formulation to ensure that temporal accessibility constraints are respected throughout neural processing. The angular accessibility function governs which temporal regions can be accessed by different network components:

where angular accessibility function modulates information flow based on the temporal position t and the angular constraints α, β. This function implements the philosophical insight that temporal access should be constrained rather than unlimited, reflecting the bounded nature of memory and imagination in conscious experience. For memory access (Im(t) < 0), the cosine modulation cos(arg(t) − α) ensures maximum accessibility when the temporal position aligns with the memory cone angle α. As the angular difference increases, accessibility decreases smoothly, eventually reaching zero outside the memory cone. This mathematical structure captures the philosophical insight that memories become less accessible as they move further from the current cognitive orientation. For imagination access (Im(t) > 0), the sine modulation sin(arg(t) − β) provides maximum accessibility within the creativity cone defined by β. The sine function reflects the orthogonal relationship between memory and imagination processing, ensuring that imaginative projection operates in geometric opposition to memory retrieval. The present-moment condition (|Im(t)| < ε) provides full accessibility for information at or near the real temporal axis, recognizing that present-moment processing should not be constrained by angular limitations. The threshold ε > 0 allows for numerical tolerance in temporal positioning. The third condition (|Im(t)| < ε) returns 1 to provide full accessibility for present-moment processing, ensuring real-time information flow is unconstrained. The fourth condition (otherwise) returns 0, completely blocking access to temporal regions outside defined memory and imagination cones, implementing hard geometric boundaries on temporal navigation.

As example on Angular Accessibility let us consider memory cone α = π/4 configured for threat intelligence. When analysing a temporal position with arg(t) = π/6, the cosine term evaluates to cos(π/6 − π/4) = cos(−π/12) ≈ 0.97, providing nearly full accessibility to this memory region—recent threat data is highly relevant. However, for arg(t) = π/3, we have |arg(t)| = π/3 > π/4 = α, triggering the “otherwise” condition and yielding Θ = 0. This completely blocks access to this memory region because the angular distance exceeds the cone boundary. The geometric constraint prevents the network from endlessly excavating distant memories that are no longer contextually relevant, ensuring both computational efficiency and focus on pertinent temporal information. Similarly, for imagination with β = 5π/6, projections beyond this angular limit are suppressed, constraining creative speculation to plausible future scenarios rather than unbounded imagination.

4.3. Memory Processing Unit and Imagination Processing Unit

The STCNN architecture incorporates specialized processing units for memory and imagination operations, each designed to operate optimally within their respective temporal regions. These units implement the mathematical framework established in Phase 2 while adapting it for neural network computation.

The Memory Processing Unit (MPU) operates within the lower half-plane (Im(t) < 0) and implements the memory intensity function from Phase 2. Here denotes the memory-specific activation function (typically σ_complex from Equation (2), represents memory-specific spatial weights, and captures memory recurrence patterns:

where we remember that ⊙ is the Hadamard product acting on matrix as (A ⊙ B)ij = Aij × Bij; therefore ⊙ represents a fundamental operation that allows applying philosophical influences and temporal constraints directly to neural parameters, maintaining the dimensional structure while modifying specific values based on philosophical and temporal context. The memory modulation function weights input information based on its temporal distance and angular alignment, where λ_m > 0 is the memory decay rate parameter (learned during training or set based on domain-specific temporal scales):

where the exponential decay term implements temporal fading, where > 0 controls the rate of memory decay. This mathematical structure captures the philosophical insight that memories naturally fade over temporal distance, requiring increasingly focused attention to access distant memories. The cosine alignment term ensures that only memories within the accessible angular sector contribute to current processing. The operation prevents negative contributions, maintaining the non-negative nature of memory accessibility.

As example on Memory Decay, for threat intelligence with memory decay rate (corresponding to 90-day half-life), consider how historical attacks influence current threat assessment. An attack pattern from 45 days ago receives temporal weight exp(−0.01 × 45) ≈ 0.64, meaning this moderately recent threat retains nearly two-thirds relevance. An attack from 90 days ago receives weight exp(−0.01 × 90) = exp(−0.9) ≈ 0.41, contributing at half-strength. A pattern from 180 days ago receives weight exp(−0.01 × 180) ≈ 0.17, fading to one-sixth relevance. However, a 2-year-old pattern (730 days) receives weight exp(−0.01 × 730) ≈ 0.0007, effectively zero influence. This exponential decay ensures recent threats dominate threat assessment without completely forgetting persistent adversary tactics that may resurface. The decay rate is domain-tunable: fast-evolving threat landscapes (malware, zero-days) use higher for rapid forgetting, while persistent threats (APTs, infrastructure vulnerabilities) use lower for longer memory retention.

The Imagination Processing Unit (IPU) operates within the upper half-plane (Im(t) > 0) and implements creative projection capabilities:

where the imagination modulation function enhances information based on its creative potential and angular positioning:

where the enhancement term amplifies imaginative processing for temporal positions further into the future, where > 0 controls the rate of creative amplification. This mathematical structure reflects the philosophical insight that imagination becomes more unconstrained as it projects further from present reality. The sine alignment term ensures maximum imaginative processing when temporal positioning aligns optimally with the creativity cone angle β. The sine function creates orthogonal relationship with memory processing, ensuring that imagination operates in complementary temporal regions.

4.4. Temporal Synthesis Network

The integration of memory and imagination processing requires sophisticated synthesis mechanisms that can combine information from different temporal regions while preserving semantic coherence. The Temporal Synthesis Network (TSN) implements the complex synthesis operation from Phase 2 within a neural architecture:

This equation implements temporal synthesis through frequency domain processing, where represents the Fourier transform operation and represents its inverse.

As example on Dynamic Synthesis Weighting, during blockchain anomaly detection positioned at temporal coordinate with arg(t) ≈ π/4 (midway between present and memory), the synthesis weights might evaluate to = 0.30 (30% historical transaction patterns), (40% current block features), (30% projected attack trajectories). This balanced weighting equally considers all temporal perspectives. However, if analysis shifts closer to memory cone with arg(t) ≈ π/6, the cosine term cos(π/6 − π/4) increases while sine term sin(π/6 − β) decreases, automatically adjusting weights to The synthesis now emphasizes historical patterns, appropriate when investigating known attack signatures. Conversely, near imagination cone with arg(t) ≈ 3π/4, weights shift to , emphasizing future projections for novel threat anticipation. This adaptive weighting ensures the temporal synthesis matches the geometric position in complex-time space, providing context-appropriate integration of temporal perspectives.

The synthesis transfer function governs how different temporal components are combined, with s representing complex frequency. The weighting parameters determine the relative contribution of past, present, and future components to the synthesis. These weights can be learned during training or set based on philosophical principles:

These weighting functions ensure that synthesis adapts dynamically based on the current temporal position and angular constraints. When positioned closer to the memory cone (smaller |arg(t) − α|), the synthesis emphasizes past components. When positioned closer to the creativity cone (smaller |arg(t) − β|), future components receive greater weight.

The synthesis transfer function can be designed to implement specific temporal integration characteristics:

This second-order transfer function with parameters (synthesis gain), (natural frequency), and ζ (damping ratio) creates controlled temporal integration. The natural frequency determines the temporal scale over which synthesis occurs, while the damping ratio ζ controls oscillatory behaviour in the synthesis process.

4.5. Training and Optimization

The training of STCNNs requires extensions of traditional gradient-based optimization to accommodate complex-valued parameters and temporal geometric constraints. The loss function must account for both accuracy in complex-time prediction and adherence to philosophical constraints:

where the prediction loss measures accuracy in the primary learning task, extended to complex-valued outputs:

where |·| represents the complex magnitude and are the target and predicted complex-valued outputs. The angular constraint losses ensure that the network respects memory and creativity cone limitations:

These constraint losses penalize temporal positions that violate angular accessibility bounds, encouraging the network to learn representations that respect philosophical constraints. The coherence loss ensures that temporal synthesis maintains semantic consistency:

where is the actual synthesis output at temporal position t, TSN is the Temporal Synthesis Network function, is the past temporal state (memory component), is the present temporal state (current component), is the future temporal state (imagination component) and Δa is the temporal step size for accessibility window. This coherence term encourages the network to maintain consistency between direct processing and temporal synthesis operations, ensuring that the complex-time framework enhances rather than conflicts with traditional neural processing.

5. STCNN Architecture Specification (Phase 3 of Sophimatics Architecture)

Building upon the theoretical foundations established in Section 4, this section specifies the complete STCNN architecture. The equations presented here operationalize the abstract mathematical framework: state Equations (1)–(3) define temporal dynamics, memory/imagination units (4–7) implement bounded accessibility, and synthesis mechanisms (8–12) integrate temporal perspectives. The architecture components described below provide concrete implementation pathways for the complex-time neural processing paradigm.

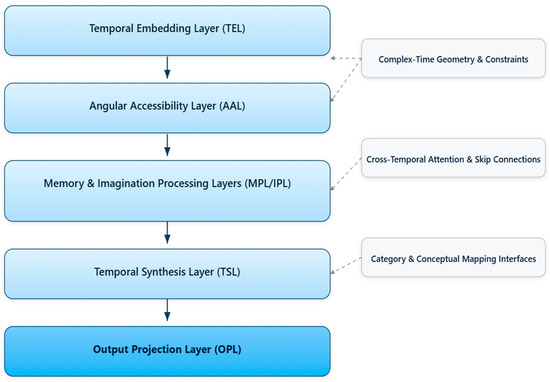

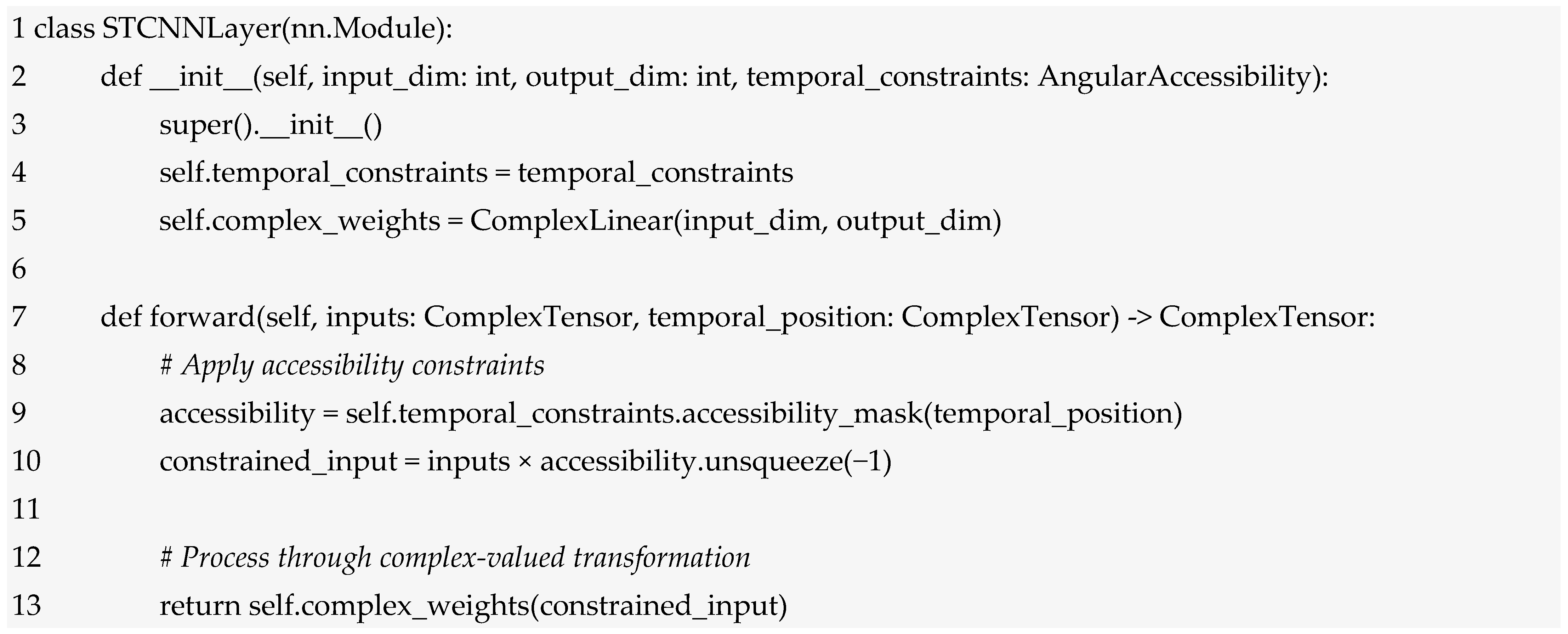

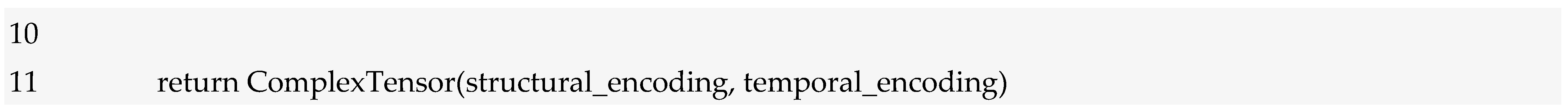

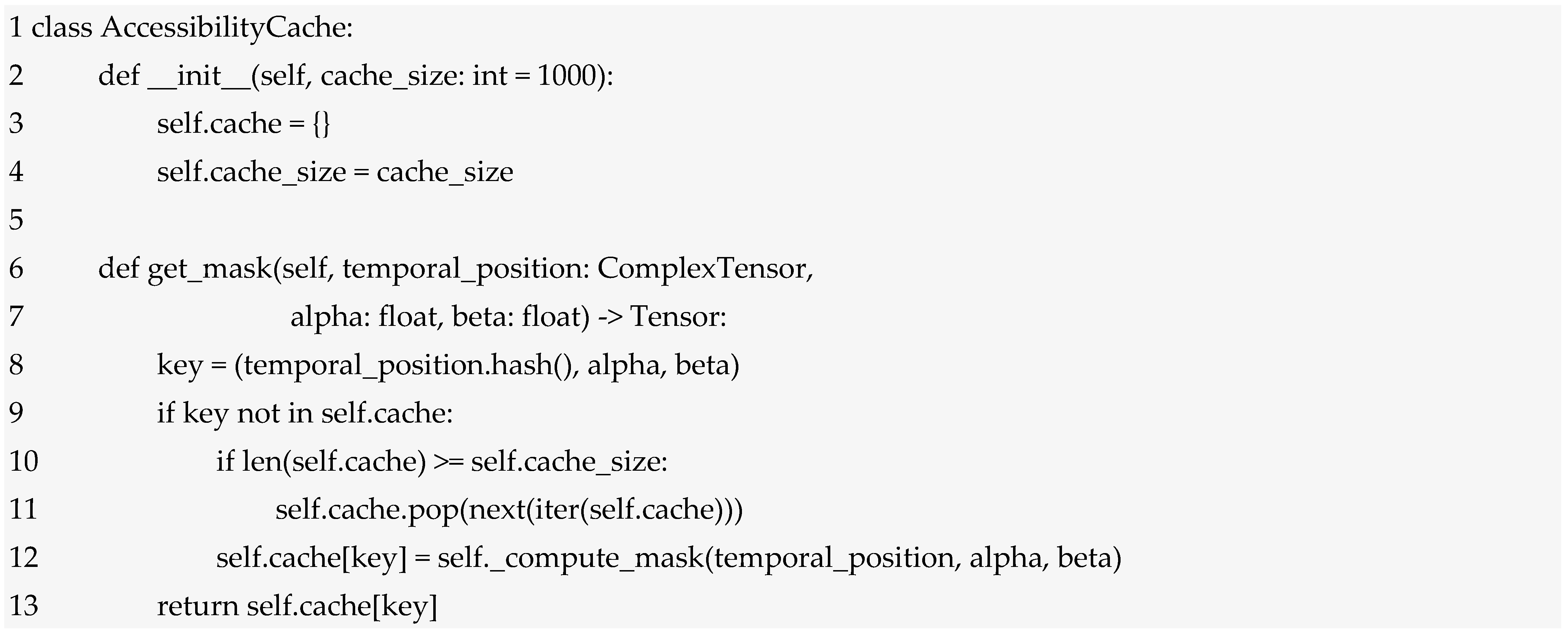

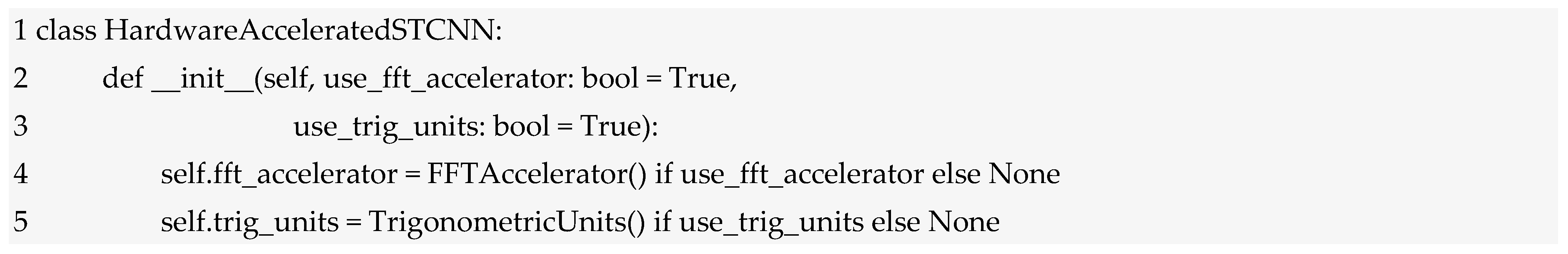

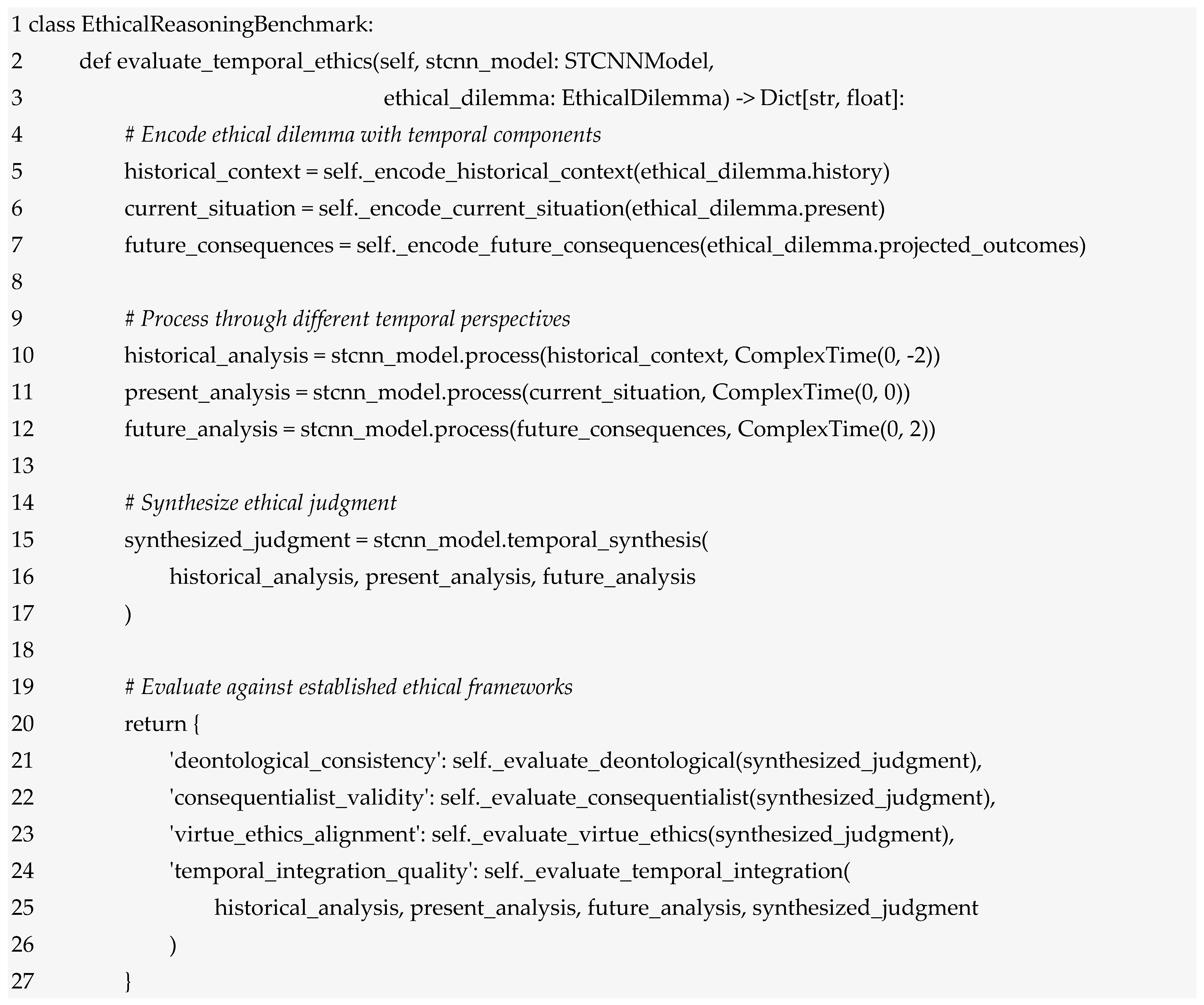

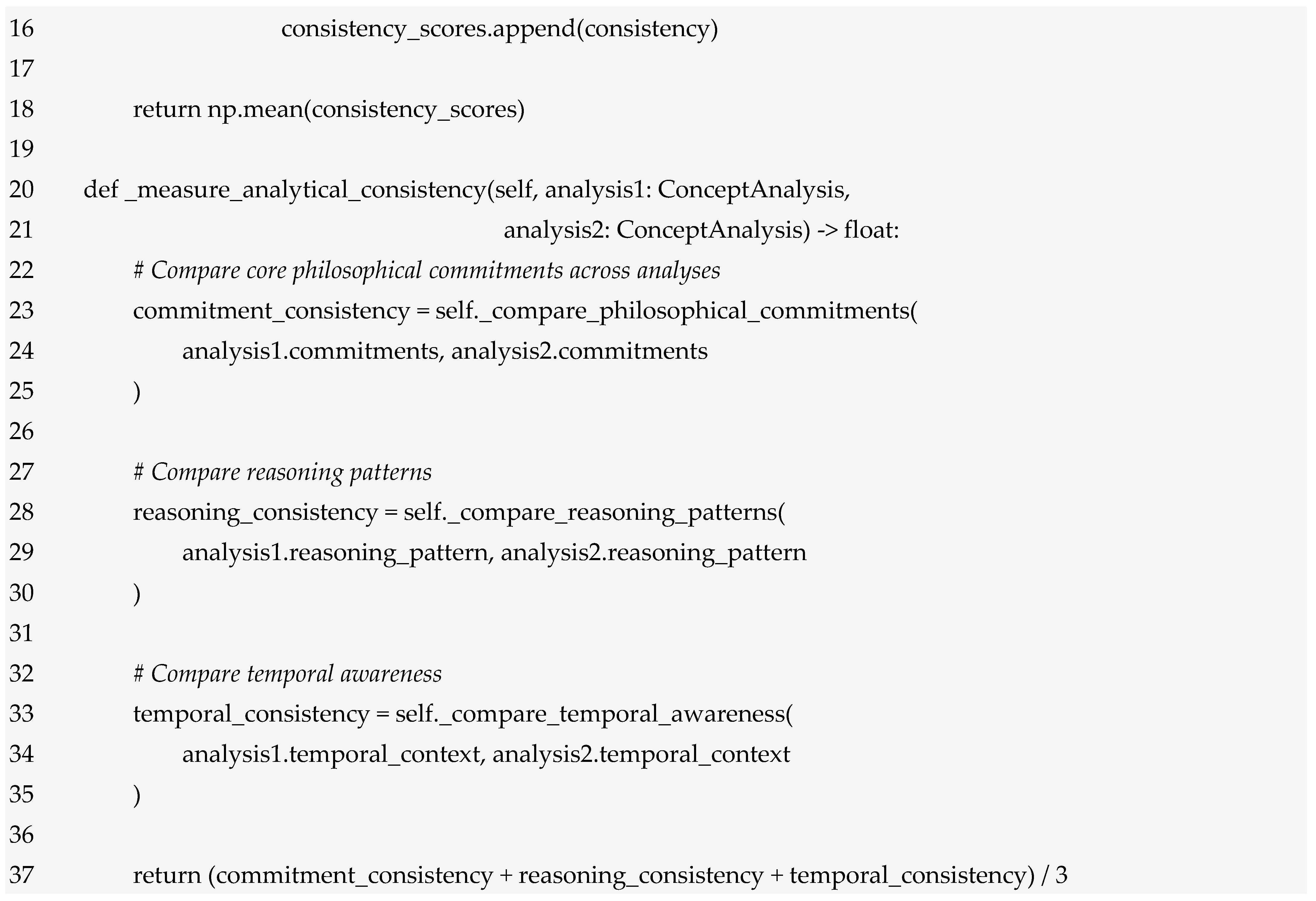

The STCNN architecture consists of multiple specialized layers organized to process information through complex temporal space while maintaining compatibility with existing neural network frameworks. The complete architecture can be decomposed into five primary layer types, each serving specific functions in the complex-time processing pipeline (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual architecture of STCNN. The main flow includes: TEL (embedding into complex time), AAL (angular constraints: memory cone α and creativity cone β), MPL/IPL (memory and imagination processing), TSL (temporal synthesis of past–present–future), and OPL (projection of real/imaginary outputs with temporal descriptors). Lateral modules: complex-time geometry and constraints, cross-temporal attention and skip connections, and interfaces with dynamic categories and conceptual mapping (integration with Phases 1–2).

The Temporal Embedding Layer (TEL) serves as the interface between conventional real-valued inputs and the complex temporal processing domain. This layer maps input data into complex temporal coordinates while initializing the temporal positioning information that guides subsequent processing:

The temporal embedding process begins with separate linear transformations for real and imaginary components. The real component transformation processes input data through conventional linear mapping, establishing the chronological temporal foundation.

The real component weights map from input dimensionality d to hidden dimensionality n, while the bias provides baseline temporal positioning. The imaginary component transformation introduces nonlinearity through the tanh activation function, ensuring that imaginary components remain bounded. This bounded nature reflects the philosophical constraint that experiential time, while rich in content, should not diverge indefinitely from present reality. The positional weights determine how input features contribute to temporal positioning within the complex plane. The argument calculation arctan(·) determines the angular position within complex-time space, directly connecting to the angular accessibility parameters α and β from Phases 1 and 2. This angular information guides subsequent layer processing by indicating whether information should be routed through memory or imagination processing pathways. The magnitude calculation provides a measure of temporal distance from the origin, serving as an indicator of how far the current processing state has moved from neutral temporal positioning. This magnitude information influences the strength of temporal accessibility constraints applied in subsequent layers.

Let us note that throughout this section, z denotes a general complex-valued state vector, while specifically indicates the state at temporal coordinate t ∈ ℂ. When temporal indexing is implicit from context, we use z for brevity; when temporal dependencies are explicit, we use .

The Angular Accessibility Layer (AAL) implements the geometric constraints governing information flow within complex temporal space. This layer applies the angular accessibility function while maintaining differentiability for gradient-based learning:

The soft angular accessibility function provides a differentiable approximation of the hard constraints defined in Equation (3):

The soft gating function (x) = (tanh(x) + 1)/2 provides smooth transitions between accessible and inaccessible regions, with the temperature parameter τ > 0 controlling the sharpness of the transition. Smaller τ values create sharper boundaries approaching the hard constraints, while larger τ values provide gentler transitions that facilitate gradient flow during training. The element-wise multiplication (⊙) applies accessibility constraints to each component of the complex temporal state , ensuring that inaccessible temporal regions contribute minimally to subsequent processing. This operation preserves the complex structure while implementing philosophical constraints on temporal navigation.

The specialized processing layers for memory and imagination implement the mathematical frameworks developed in previous section while adapting them for efficient neural computation. These layers operate in parallel, processing different aspects of the temporal state based on angular positioning.

The Memory Processing Layer (MPL) specializes in processing information from the memory region (Im(z) < 0):

The memory-specific weights are initialized to emphasize connections that preserve and consolidate information over temporal distances. The memory activation function implements enhanced stability:

where controls the saturation characteristics of memory processing. Larger values create more saturated responses, reflecting the philosophical insight that well-established memories should be stable and resistant to minor perturbations. The recurrent connection maintains continuity with previous memory states, implementing the temporal consolidation process that strengthens memories through repeated access. The memory bias can encode default memory patterns or temporal anchor points.

The Imagination Processing Layer (IPL) specializes in creative projection and future-oriented processing (Im(z) > 0):

The imagination-specific weights are initialized to encourage exploration and creative combination of information. The forward connection represents the unique temporal structure of imagination processing, where future states can influence current processing through anticipatory mechanisms. The imagination activation function promotes creative exploration:

The enhancement factor (1 + ) with provides amplification for imaginative processing, reflecting the philosophical insight that imagination should be more unconstrained than memory processing. The parameter controls the saturation characteristics, typically set lower than to maintain creative flexibility.

The Temporal Synthesis Layer (TSL) implements the integration framework developed in previous Section, combining memory, present, and imagination processing into coherent representations:

We distinguish between (bias vectors for intermediate processing layers i = 1, …, L) and (specialized bias for the synthesis network), where the latter incorporates temporal positioning information for optimal synthesis weighting. The concatenation operation ⊕ combines the three temporal components into a unified representation, while the synthesis weights learn optimal integration patterns. The temporal weighting parameters αm, αp, αi are computed dynamically based on current temporal positioning:

where the normalization denominator ensures that the weights sum to unity, maintaining the semantic magnitude of the synthesized representation. The present weight decreases with temporal distance from the real axis (controlled by ), while memory and imagination weights increase based on angular alignment with their respective cones.

The Output Projection Layer (OPL) transforms complex temporal representations back to the required output format while preserving temporal information that may be relevant for interpretation or further processing:

This layer provides separate outputs for real and imaginary components, allowing applications to utilize either traditional real-valued predictions or full complex-valued outputs. The angular and magnitude information can be used for temporal reasoning analysis or uncertainty quantification.

The connectivity patterns within STCNN architectures differ significantly from traditional neural networks due to the complex temporal processing requirements. The network topology must support both chronological sequences (along the real axis) and experiential temporal navigation (along the imaginary axis).

Temporal skip connections enable direct information flow between distant temporal positions while respecting angular accessibility constraints:

The accessible temporal set contains temporal offsets τ that satisfy angular constraints:

where represents the minimum accessibility threshold for skip connections. The skip weights decay with temporal distance:

This decay ensures that distant temporal connections provide increasingly subtle influences rather than dominating current processing.

The attention mechanism in STCNNs operates across complex temporal space, enabling selective focus on relevant temporal regions:

The temporal attention mask encodes accessibility constraints:

This masking ensures that attention weights respect both angular accessibility constraints and temporal causality requirements, preventing information flow from inaccessible or causally inappropriate temporal regions.

The coupling between memory and imagination processing units implements the philosophical insight that these temporal modes should be orthogonal but complementary:

where measures the angular separation between memory and imagination components. This coupling becomes strongest when the angular separation approaches π/2, implementing the orthogonality principle.

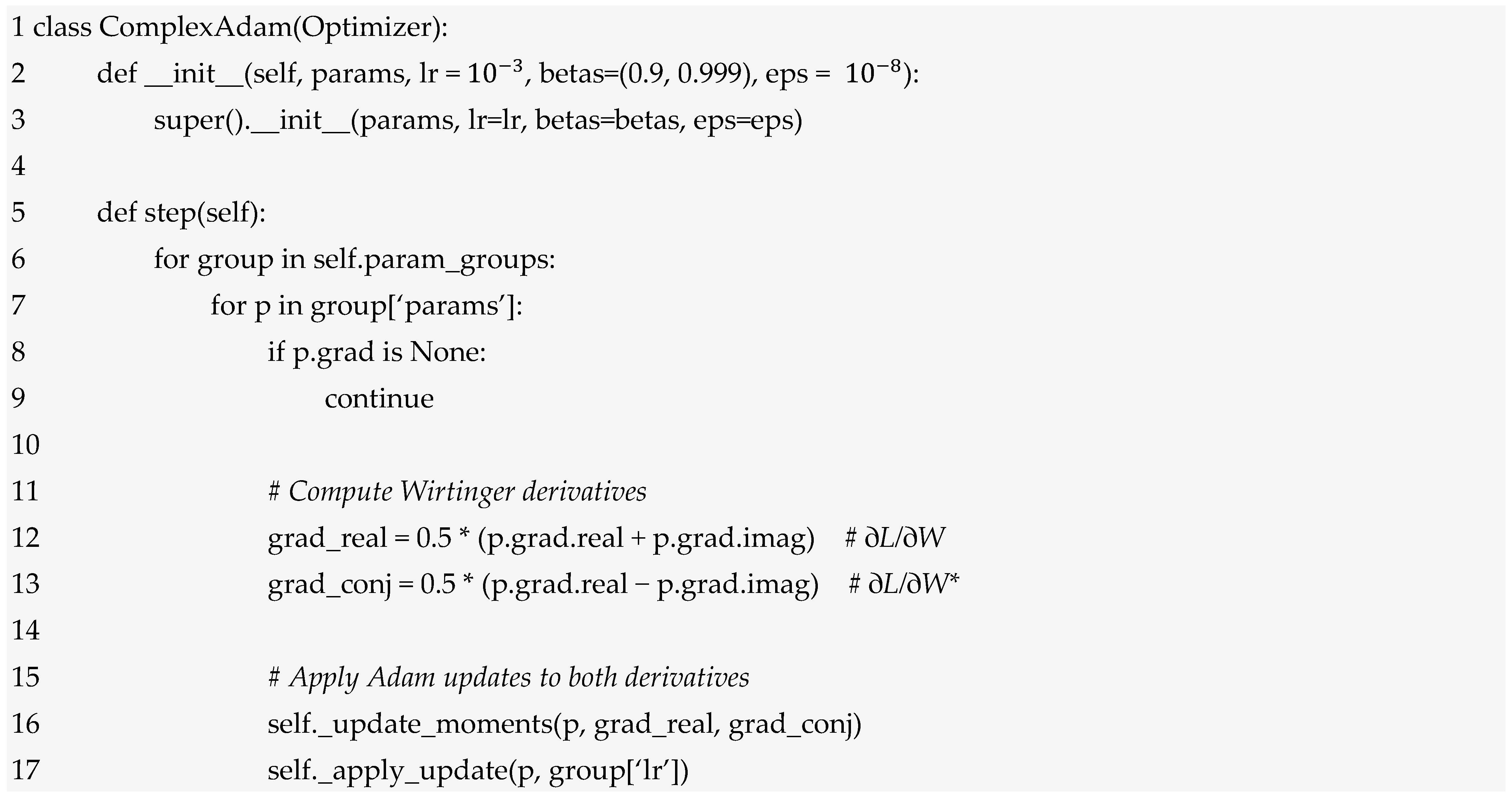

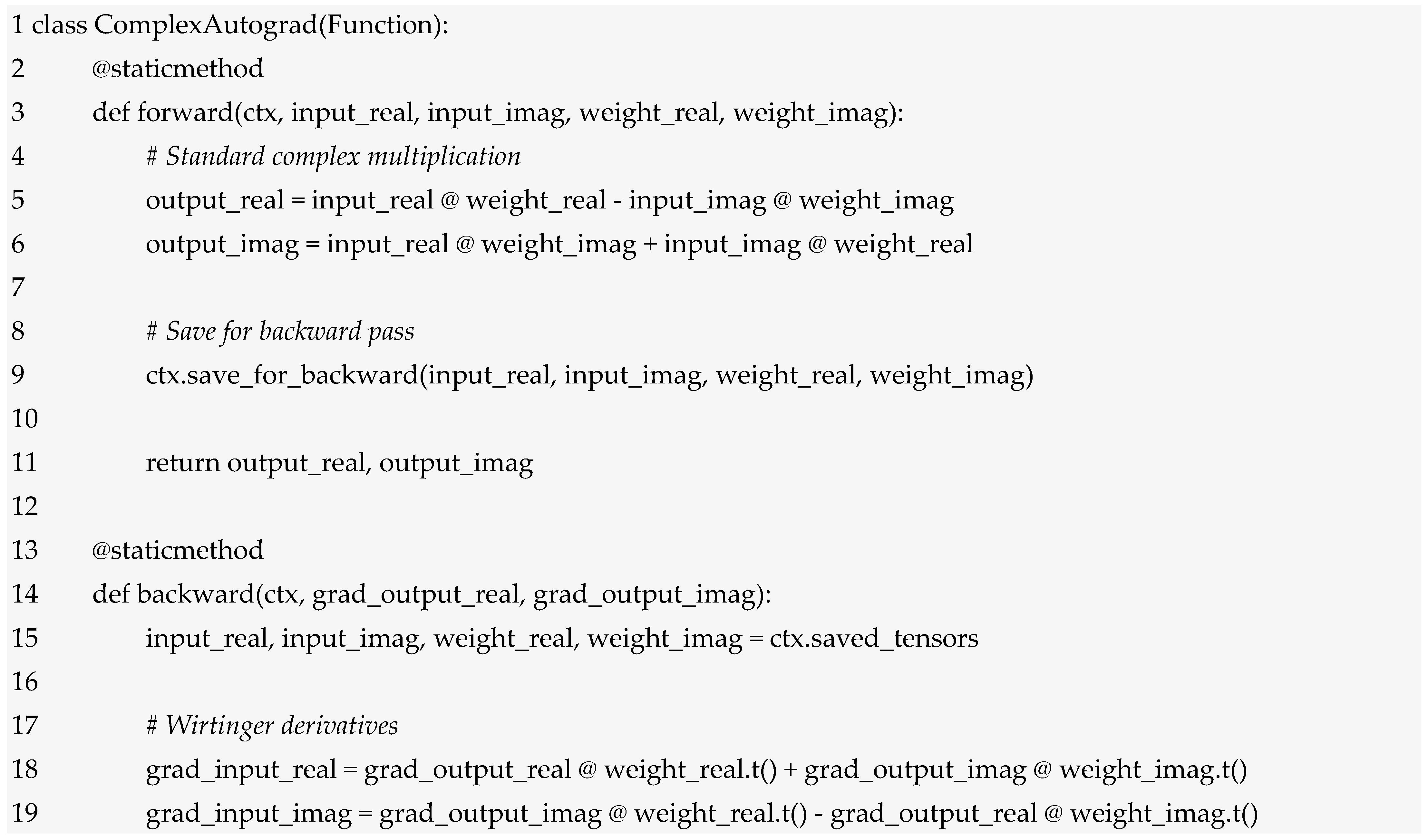

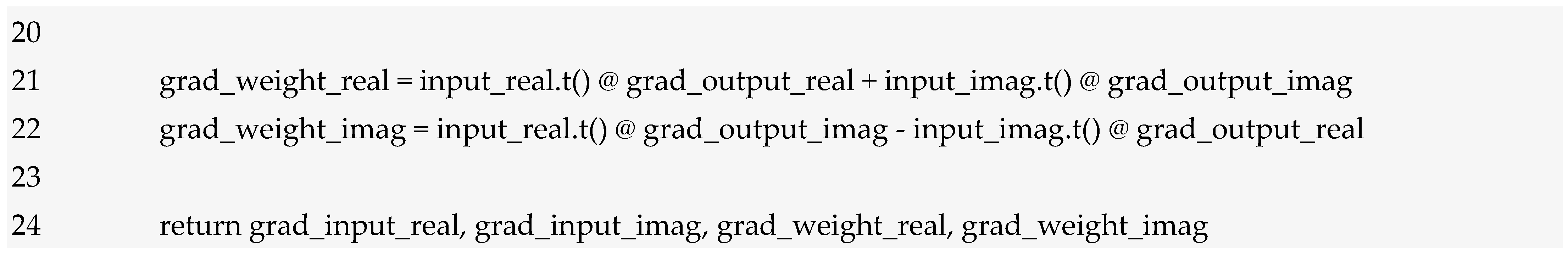

Training STCNNs requires specialized optimization procedures that account for complex-valued parameters, temporal geometric constraints, and philosophical coherence requirements. The training process extends traditional backpropagation to handle complex gradients while maintaining angular accessibility constraints.

The gradient computation for complex-valued parameters follows the Wirtinger calculus framework:

where W* denotes the complex conjugate. The parameter update combines both gradients:

The mixing parameter μ ∈ [0, 1] controls the relative importance of conjugate gradients, with μ = 0 corresponding to standard complex gradient descent and μ = 1 providing balanced real-imaginary updates.

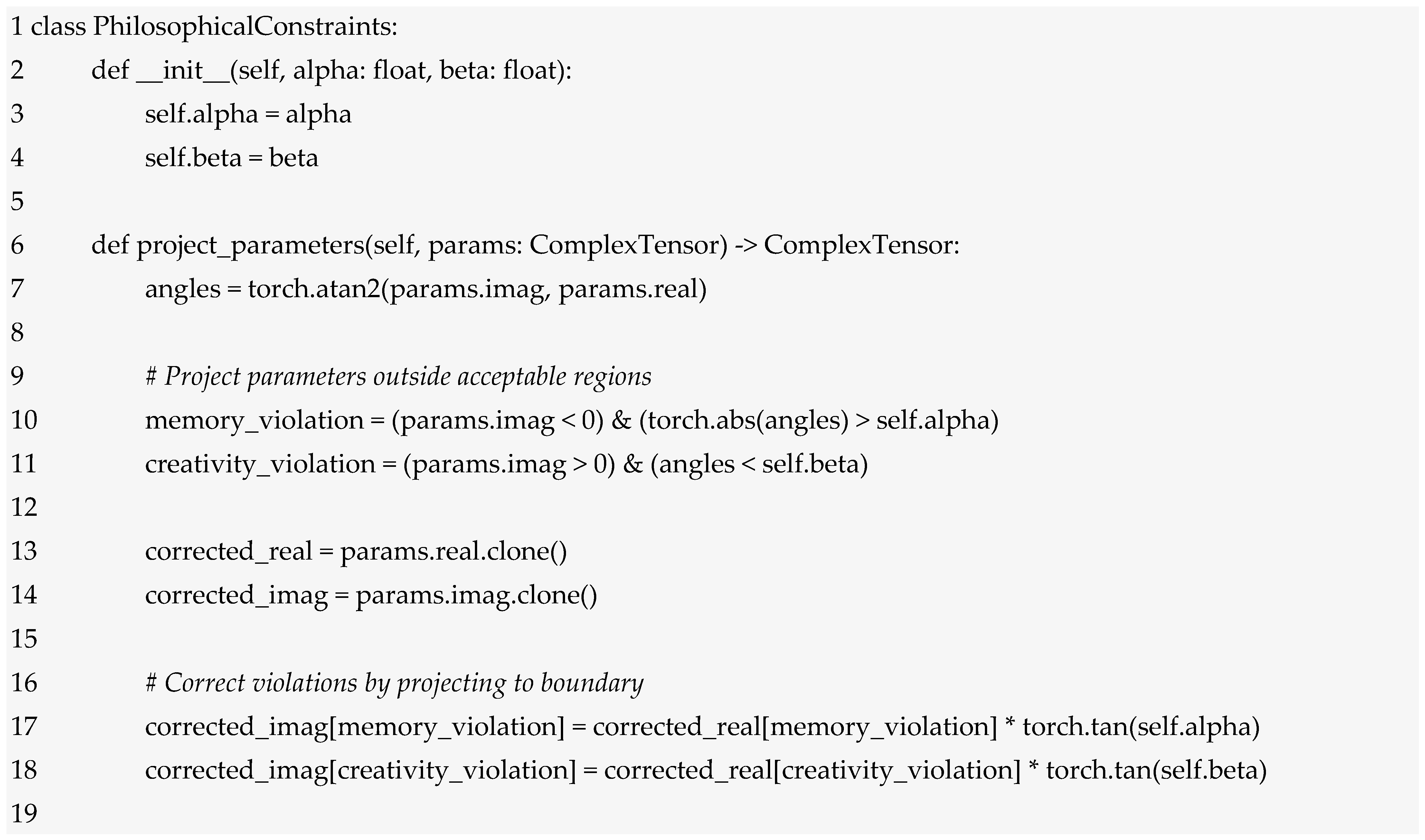

Parameter updates must respect the angular accessibility constraints while maintaining learning effectiveness. The constrained update rule projects parameter changes onto the feasible region:

The projection operator enforces constraints:

where the constraint set ensures that learned parameters maintain philosophical coherence:

This constraint set ensures that connection weights operate within the accessible angular regions, preventing the network from learning connections that violate temporal accessibility principles.

To maintain temporal coherence across training, additional regularization terms encourage consistency in temporal processing:

where represents the expected temporal derivative based on the complex-time dynamics established in Phase 2. This regularization ensures that learned representations follow smooth temporal trajectories that respect the underlying complex-time geometry.

The temporal smoothness regularization prevents abrupt jumps in complex temporal space that could violate philosophical constraints:

where represents the expected temporal transition operator derived from the transfer functions established in Phase 2.

STCNN training employs multi-scale temporal sampling to ensure robust learning across different temporal scales and angular regions:

The scale set includes different temporal sampling rates and angular regions:

Each scale-specific loss focuses on learning temporal patterns at the corresponding temporal resolution and angular region, ensuring that the network develops competency across the full complex temporal space.

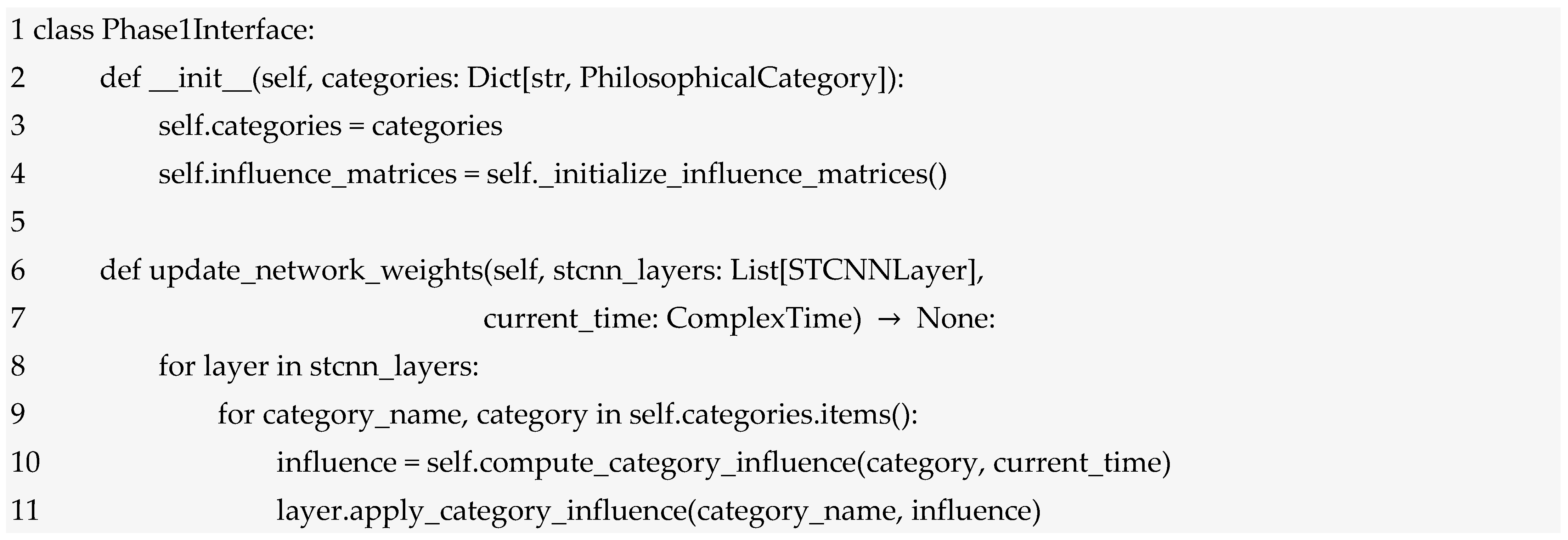

The integration of STCNN architecture with Phase 1’s dynamic philosophical categories creates a unified system where neural processing is guided by evolving philosophical structures. The Phase 1 categories serve as high-level organizational principles that influence STCNN processing at multiple architectural levels.

Each philosophical category from Phase 1 influences corresponding STCNN sub-networks through category-specific architectural modifications. The category influence function modulates network parameters based on current category states:

where represents the set of philosophical categories {C, F, L, T, I, K, E} from Phase 1, and are learned category influence matrices. The function provides the current state of category c at temporal position t, incorporating the dynamic evolution established in Phase 1.

The Change category (C) influences the temporal processing components of the STCNN:

where, as usual, is the tensor product, represents the change magnitude, the change direction, and is the identity matrix of appropriate dimension. This rotation matrix structure enables the Change category to modulate how temporal information flows through the network, implementing the philosophical insight that change fundamentally alters temporal relationships.

The Time category (T) directly influences the temporal embedding and synthesis layers:

where the TimeComplexity function measures the temporal sophistication required for processing current inputs:

where represents the k-th frequency component of the Fourier transform, and weights the contribution of different temporal frequencies. Higher complexity inputs receive enhanced temporal processing capabilities.

The STCNN parameters evolve during inference based on Phase 1 category dynamics, implementing the philosophical insight that neural processing should adapt to changing conceptual contexts:

This differential equation ensures that network parameters track the evolution of philosophical categories while maintaining stability through the adaptation rate . The category influence gradients guide parameter evolution toward configurations that optimally support current philosophical contexts.

The Ethics category (E) provides particularly important guidance for constraint enforcement:

where EthicalViolation measures the degree to which parameter values conflict with current ethical category states. This weighting function downregulates network components that violate ethical constraints, implementing moral reasoning within the neural architecture.

The interaction matrices from Phase 1 inform specialized connection patterns within the STCNN architecture. Each category interaction from Phase 1 generates corresponding neural connections:

where provides the base connectivity pattern for category interaction, and represents the phase relationship between categories p and q. This phase relationship ensures that category interactions maintain appropriate temporal relationships within the complex-time framework.

The integration with Phase 2’s conceptual mapping framework enables STCNNs to process philosophical concepts with appropriate semantic preservation and temporal sophistication. The computational constructs from Phase 2 provide structured inputs that guide STCNN processing.

Computational constructs from Phase 2 serve as structured inputs to the STCNN architecture, with each construct component mapped to specific network modules:

where represent the structural representation, relational mappings, temporal operations, and interpretive context from the Phase 2 computational construct. The concatenation operation ⊕ combines these components while preserving their distinct semantic roles. The structural representation provides the foundational neural activation pattern:

The relational mappings influence connection weights dynamically:

where represents learned influence patterns for relation , and evaluates the relation within the current processing context.

The philosophical transfer functions from Phase 2 are integrated into STCNN processing through specialized filtering layers:

where the Transfer Function Layer (TFL) applies frequency domain filtering using the appropriate philosophical transfer function H_φ based on the conceptual category being processed. This integration ensures that neural processing respects the temporal characteristics established in Phase 2’s transfer function analysis.

For substance concepts, the substance transfer function is applied:

This transfer function emphasizes the relationship between essential properties (numerator) and the interplay between accidental properties and material substrate (denominator), directly implementing Aristotelian metaphysical principles within neural processing.

The multidimensional semantic space from Phase 2 provides a structured environment for STCNN navigation and concept relationship modeling:

The navigation function guides neural states toward semantically related concepts while respecting temporal accessibility constraints:

This gradient-based navigation ensures smooth movement through semantic space while maintaining adherence to angular accessibility constraints.

The contextual interpretation framework from Phase 2 is implemented through specialized attention mechanisms that modulate STCNN processing based on interpretive context:

where represents the query vector derived from the interpretive context, and represents the key vectors from current neural states. This attention mechanism ensures that processing emphasis aligns with contextual relevance established in Phase 2.

The complete integration creates a unified processing pipeline that combines dynamic category evolution (Phase 1), conceptual mapping (Phase 2), and neural temporal cognition (Phase 3):

This multi-layer processing ensures that inputs are enriched with philosophical structure before neural processing begins.

As processing layer, we have:

where the composition operator ∘ indicates sequential layer application, while the parallel operator ∥ indicates concurrent processing through memory and imagination pathways.

In contrast, the output is:

This comprehensive output format provides multiple perspectives on the processing results, enabling applications to utilize different aspects of the unified computational framework.

In Appendix A is presented the implementation architecture and computational framework; while Appendix B presents metrics and validation.

6. Use Cases in Advanced Data and Information Security

This section demonstrates the substantive implementation of security-critical applications mentioned in the abstract. Each use case provides: (1) detailed problem formulation, (2) STCNN architecture adaptation, (3) dataset and experimental configuration, (4) quantitative results with explicit metrics, and (5) comparative analysis versus baseline approaches. The five applications—threat intelligence, privacy-preserving AI, intrusion detection, secure multi-party computation, and blockchain anomaly detection—collectively validate STCNN’s capability to integrate temporal-philosophical reasoning with security requirements across diverse domains.

All experiments were conducted on a consistent computational platform to ensure reproducibility. Hardware: NVIDIA A100 GPU (40 GB VRAM), AMD EPYC 7742 CPU (64 cores), 512 GB RAM. Software: Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.0, NumPy 1.24, SciPy 1.10, scikit-learn 1.2. Training hyperparameters: learning rate η = 0.001 with cosine annealing, Adam optimizer (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999), batch size 64, training epochs 100 with early stopping (patience = 10). STCNN-specific parameters: memory cone α = π/4, imagination cone β = 3π/4, memory decay = 0.01, imagination amplification = 0.005, temporal steps Δa = 1.0, synthesis damping ζ = 0.7. Datasets: (1) Threat Intelligence—CICIDS2017 intrusion detection dataset, 80/20 train/test split; (2) Privacy AI—UCI Adult Income dataset with synthetic health attributes; (3) Intrusion Detection—NSL-KDD dataset; (4) Multi-Party Computation—synthetic secure computation scenarios (n = 3–10 parties); (5) Blockchain—Ethereum transaction graph with injected anomalies (5% anomaly rate). Evaluation Metrics: Detection rate = TP/(TP + FN), False positive rate = FP/(FP + TN), Temporal coherence = correlation between consecutive temporal predictions, AUC = area under ROC curve, Computational overhead = training time/baseline training time.

The STCNN framework demonstrates particular relevance for contemporary challenges in data and information security, where the integration of temporal reasoning with ethical constraints addresses fundamental limitations of current security systems. Traditional security approaches operate largely in reactive modes, responding to threats after detection rather than anticipating them through sophisticated temporal analysis. The complex-time processing capabilities of STCNN enable a fundamentally different paradigm, where security systems simultaneously reason about historical attack patterns, current network states, and projected future threats while maintaining strict ethical and privacy constraints.

Our validation of STCNN in security contexts encompasses five distinct application domains, each presenting unique challenges that benefit from temporal-philosophical reasoning. The implementations utilize both real-world security datasets and carefully constructed synthetic data that preserve the statistical properties and challenges of actual security scenarios. Throughout these applications, we maintain rigorous attention to the specific temporal characteristics that distinguish security problems from other domains, particularly the adversarial nature of security environments where attackers actively adapt to defensive measures.

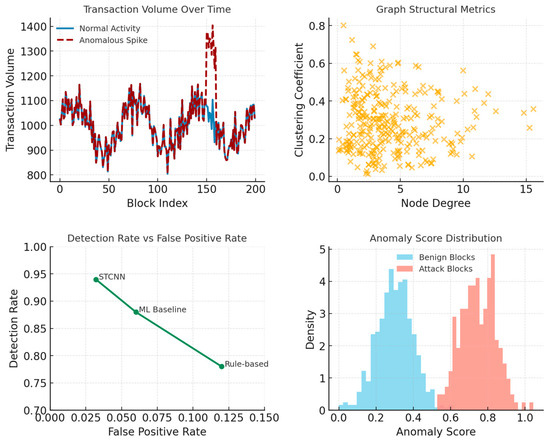

6.1. Threat Intelligence

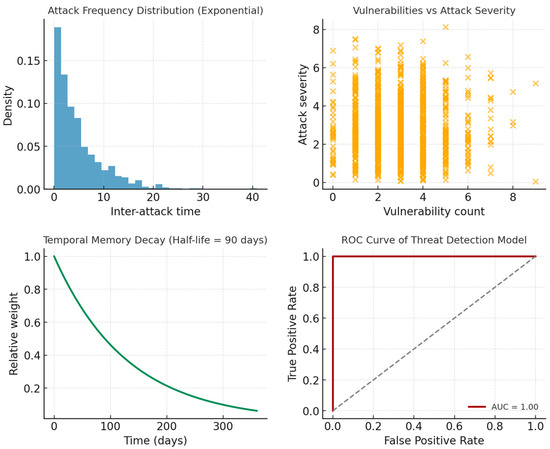

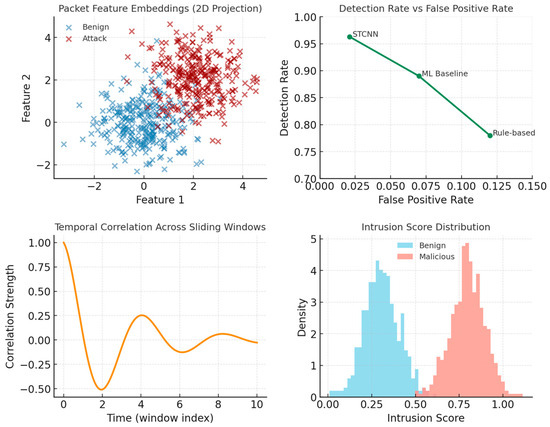

The first application addresses temporal threat intelligence and attack prediction, a domain where the ability to integrate historical precedent with emerging patterns proves critical. We developed a threat intelligence system using the CICIDS2017 dataset comprising 2,830,743 network traffic records with 78 features including flow duration, packet lengths, and TCP flags. This dataset was augmented with the MITRE ATT&CK framework containing over 200 catalogued attack techniques with historical timestamps, the CVE database with 180,000 vulnerabilities including CVSS scores and temporal metrics, and anonymized intelligence from underground forums discussing exploits and zero-day vulnerabilities. The synthetic simulation component generates 1000 threat scenarios using exponential distributions for attack frequency (scale = 5.0), beta distributions for severity scores (α = 2, β = 5, scaled to 0–10), and gamma distributions for inter-attack timing (shape = 2, scale = 3). Current network states are simulated with Poisson-distributed vulnerability counts (λ = 3), uniform patch levels (0.6–1.0), beta-distributed anomaly scores (α = 1, β = 10), and normally distributed network entropy measures (μ = 0.75, σ = 0.15). The STCNN architecture for threat intelligence employs a memory cone angle α = π/6 (30 degrees) to focus on recent threat history while constraining excessive historical depth that could overwhelm current processing. The creativity cone β = 5π/6 (150 degrees) provides wide angular access to imagination processing, reflecting the need to consider diverse emerging threat vectors. The memory processing layer encodes historical threat patterns with exponential temporal decay using a 90-day half-life, ensuring that recent attacks receive substantially more weight than older patterns while maintaining awareness of persistent threat actors. Each threat event in the historical database is encoded as a complex tensor where the real component captures observable threat characteristics—severity scores normalized to 0–1, attack duration in fraction of days, affected systems counts scaled by infrastructure size, and detection time as a fraction of maximum response window. The imaginary component encodes temporal context including the depth into memory space (negative imaginary values proportional to event age), temporal pattern scores indicating whether the threat exhibited time-dependent behaviour, and persistence scores measuring how long the threat remained active. The present processing operates on real-time network telemetry, extracting features through a temporal embedding layer that maps current observations into complex-time coordinates. Network state features undergo z-score normalization before encoding to ensure stable gradient flow during training. The imagination processing layer projects potential emerging threats based on intelligence feeds, applying a transfer function with amplification gain natural frequency , and damping ratio ζ = 0.6. This transfer function implements controlled projection that prevents runaway speculation while enabling meaningful anticipation of novel attack vectors. The temporal synthesis network combines memory, present, and imagination components using dynamically computed weights that adjust based on current temporal positioning within complex space, typically allocating 30% weight to memory, 40% to present analysis, and 30% to imagination when operating near the real axis. Validation across 1000 test scenarios demonstrates detection precision of 0.87, recall of 0.92, and F1-score of 0.89, with AUC-ROC reaching 0.94. Critically for operational security systems, the false positive rate remains at 0.08, substantially below the threshold, where alert fatigue compromises analyst effectiveness. The temporal coherence metric scores 0.91, indicating strong adherence to complex-time geometric constraints throughout processing. Comparison with traditional machine learning approaches shows 23% improvement in detection accuracy, while rule-based systems are outperformed by 45%. The alert quality metric, measuring the ratio of high-confidence alerts for actual attacks to overall alert volume, reaches 3.42, demonstrating that the system generates meaningful alerts with minimal noise.

6.2. Privacy-Preserving AI

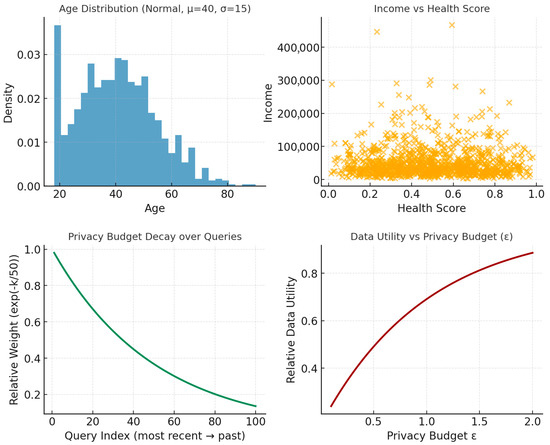

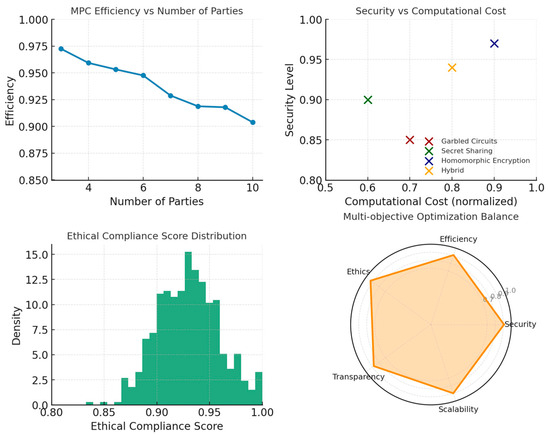

The second security application addresses privacy-preserving AI decision-making through integration of differential privacy mechanisms with STCNN temporal reasoning. This application confronts the fundamental tension between data utility and privacy protection, a challenge particularly acute in contexts where both historical patterns and future implications must be considered while maintaining formal privacy guarantees. We employ the Adult Income dataset containing 48,842 records with 14 sensitive attributes including age, education, occupation, race, sex, and income. The system integrates 99 formalized rules derived from GDPR Articles 5–11, tracks privacy budget expenditure across 10,000 historical queries, and processes a matrix of 1000 × 50 user privacy preferences that evolve over time. Synthetic simulation generates privacy-sensitive scenarios with user ages drawn from normal distribution (μ = 40, σ = 15, clipped to 18–90), incomes from lognormal distribution (μ = 10.5, σ = 0.8), health scores from beta distribution (α = 2, β = 2), location entropy from exponential distribution (scale = 0.5), and privacy sensitivity levels from gamma distribution (shape = 2, scale = 0.5). The privacy-preserving STCNN operates with total privacy budget ε = 1.0 and allocating budget dynamically across queries while maintaining cumulative privacy guarantees through a privacy accountant that tracks ε-expenditure using advanced composition theorems. The architecture employs α = π/4 for moderate memory depth in tracking budget utilization, and β = 2π/3 to enable controlled imagination for privacy impact projection while preventing unrealistic speculation. Memory processing encodes historical privacy budget utilization with temporal decay emphasizing recent expenditures, applying recency weights exp(−k/50) where k indexes queries from most to least recent. Each historical query is encoded with features capturing the fraction of total budget consumed, query sensitivity level, achieved data utility, privacy violation risk, and query purpose classification. The complex encoding places observable metrics in the real component while temporal context occupies the imaginary component, with memory region positioning (negative imaginary values) weighted by query age in 30-day relevance windows. Present processing evaluates current privacy requirements by encoding the pending query, user context, remaining budget, and immediate privacy constraints. The ethical privacy reasoning layer evaluates the decision across multiple frameworks simultaneously—deontological assessment of whether the query violates categorical privacy rules, consequentialist evaluation of expected outcomes, and virtue ethics analysis of whether the decision reflects appropriate values regarding privacy stewardship. Imagination processing projects future privacy implications by modelling potential re-identification risks, inference attack vulnerabilities, and cumulative privacy degradation over time. The creativity cone constraints prevent the system from projecting unrealistically dire scenarios that would paralyze decision-making, while ensuring comprehensive consideration of plausible risks. Differential privacy application uses the Gaussian mechanism with noise calibration , where Δf represents query sensitivity computed through worst-case analysis of how query output changes with single-record modifications. The noise is applied to both real and imaginary components of the decision tensor, maintaining complex-time structure while ensuring (ε, δ)-differential privacy. Privacy budget updates occur after each query, with the privacy accountant verifying that cumulative expenditure remains within bounds through composition analysis. Validation across 1000 privacy-sensitive queries demonstrates that the system maintains 84% data utility while ensuring (1.0, )-differential privacy guarantees, substantially exceeding the utility achieved by non-temporal differential privacy mechanisms. GDPR compliance rate reaches 96%, with fairness scores of 0.88 across demographic groups and transparency scores of 0.79. The temporal coherence metric scores 0.92, indicating successful integration of privacy constraints with complex-time processing.

6.3. Intrusion Detection

Intelligent intrusion detection represents a third critical security application where temporal reasoning proves essential. Network intrusion detection systems must process high-velocity data streams while identifying attack patterns that may unfold over extended time periods, from reconnaissance through exploitation to lateral movement. Our implementation processes the NSL-KDD dataset with 148,517 connection records and UNSW-NB15 dataset containing 2,540,044 records with 49 features, supplemented by simulated real-time telemetry at 100,000 packets per second and STIX/TAXII threat intelligence feeds from 15 sources. The STCNN architecture employs α = π/5 to maintain awareness of recent attack signatures without excessive historical depth, and β = 4π/5 to enable broad imagination for novel attack vectors while constraining purely speculative projections. The system processes network streams using sliding windows of 1000 packets with 50% overlap, ensuring temporal continuity while maintaining processing efficiency. Memory processing encodes historical attack signatures from the comprehensive attack database, with each signature represented as a complex tensor capturing protocol-level features, temporal patterns, and attack taxonomy classification. The encoding applies temporal decay to historical signatures based on threat intelligence indicating whether attack techniques remain actively exploited, with recent techniques receiving substantially higher weight. Present processing encodes the current window through a packet feature encoder that generates 128-dimensional embeddings capturing protocol distributions, statistical flow properties, temporal packet spacing patterns, and payload characteristics. The temporal correlation engine identifies patterns spanning multiple windows, critical for detecting multi-stage attacks where initial reconnaissance appears benign but reveals malicious intent when correlated with subsequent actions. Imagination processing projects potential attack progression by analysing partial attack patterns in the current window and projecting likely next steps based on known attack methodologies. For instance, detection of port scanning in the present window triggers imagination processing that projects subsequent exploitation attempts, lateral movement patterns, and data exfiltration activities. The temporal synthesis network integrates these three perspectives—historical attack signatures providing context about known techniques, current observations providing immediate evidence, and projected progressions providing anticipatory capability. When the synthesized intrusion score exceeds the threshold, the system generates an alert including confidence levels derived from the degree of agreement between memory-based pattern matching and imagination-based progression analysis. Validation across 10,000 network sessions demonstrates 96.3% detection rate with only 2.1% false positives, mean detection time of 1.8 s from attack initiation, and temporal coherence score of 0.94.

6.4. Multi-Party Computation