From Genes to Organs: A Multi-Level Neurotoxicity Assessment Following Dietary Exposure to Glyphosate and Its Metabolite Aminomethylphosphonic Acid in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.2. Verification of Glyphosate and AMPA Concentrations in Feed

2.3. Acetylcholinesterase

2.4. Dopamine

2.5. Butyrylcholinesterase

2.6. Gene Expression

2.7. Brain Histology

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

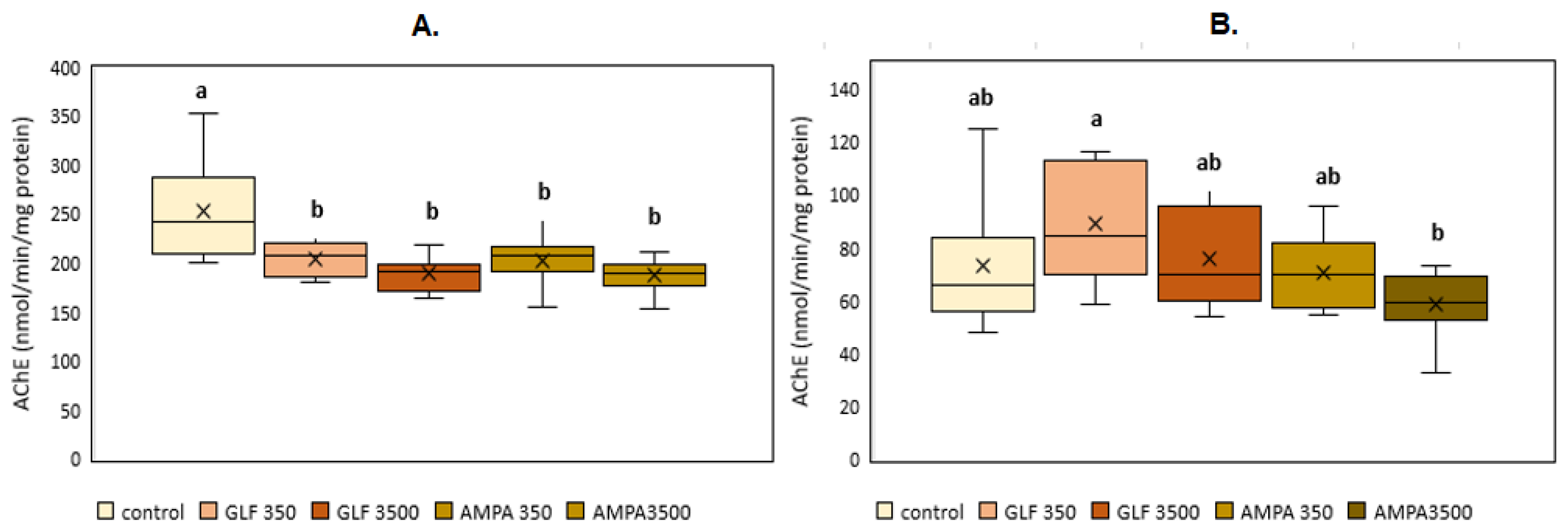

3.1. Acetylcholinesterase

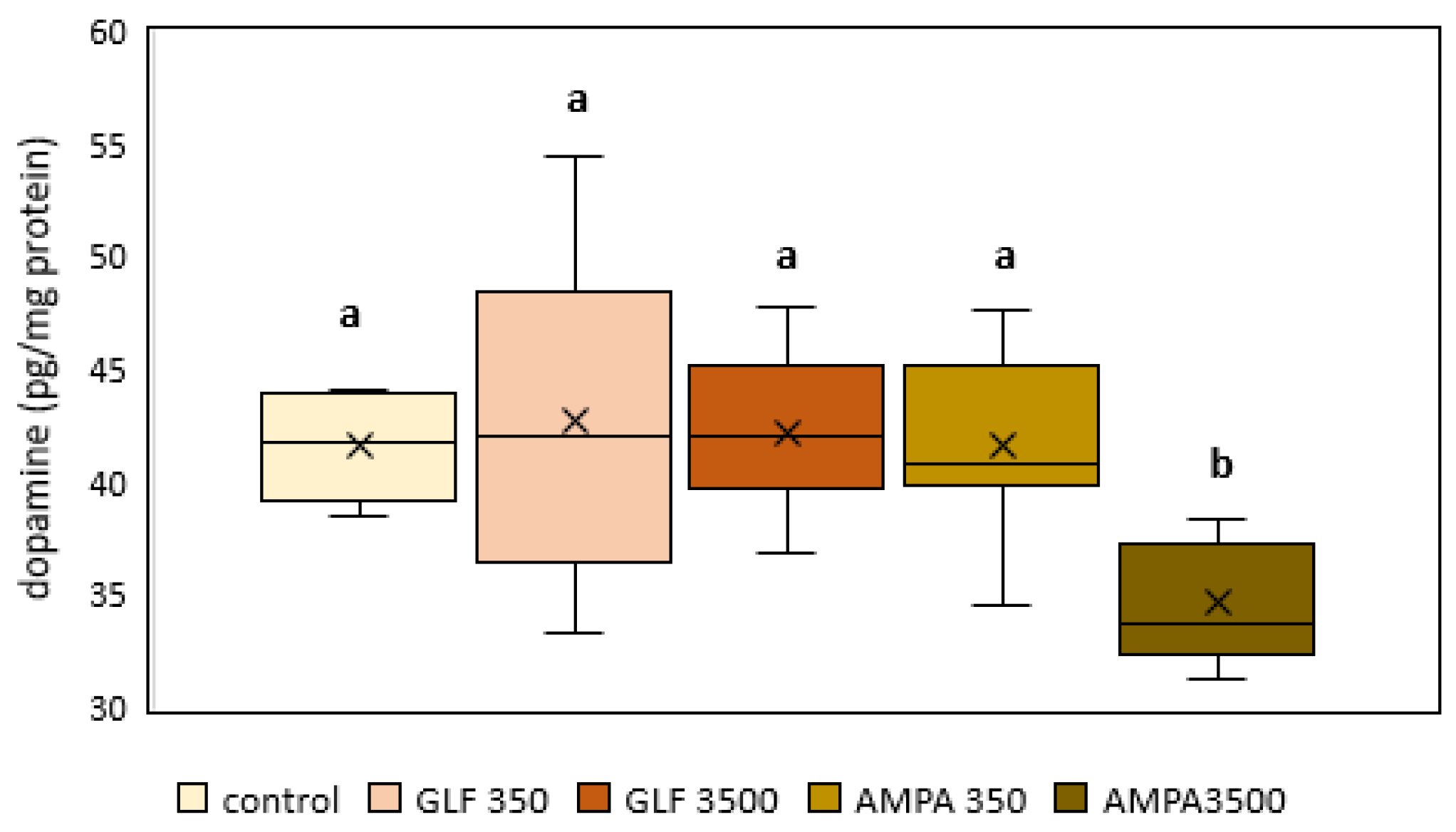

3.2. Dopamine

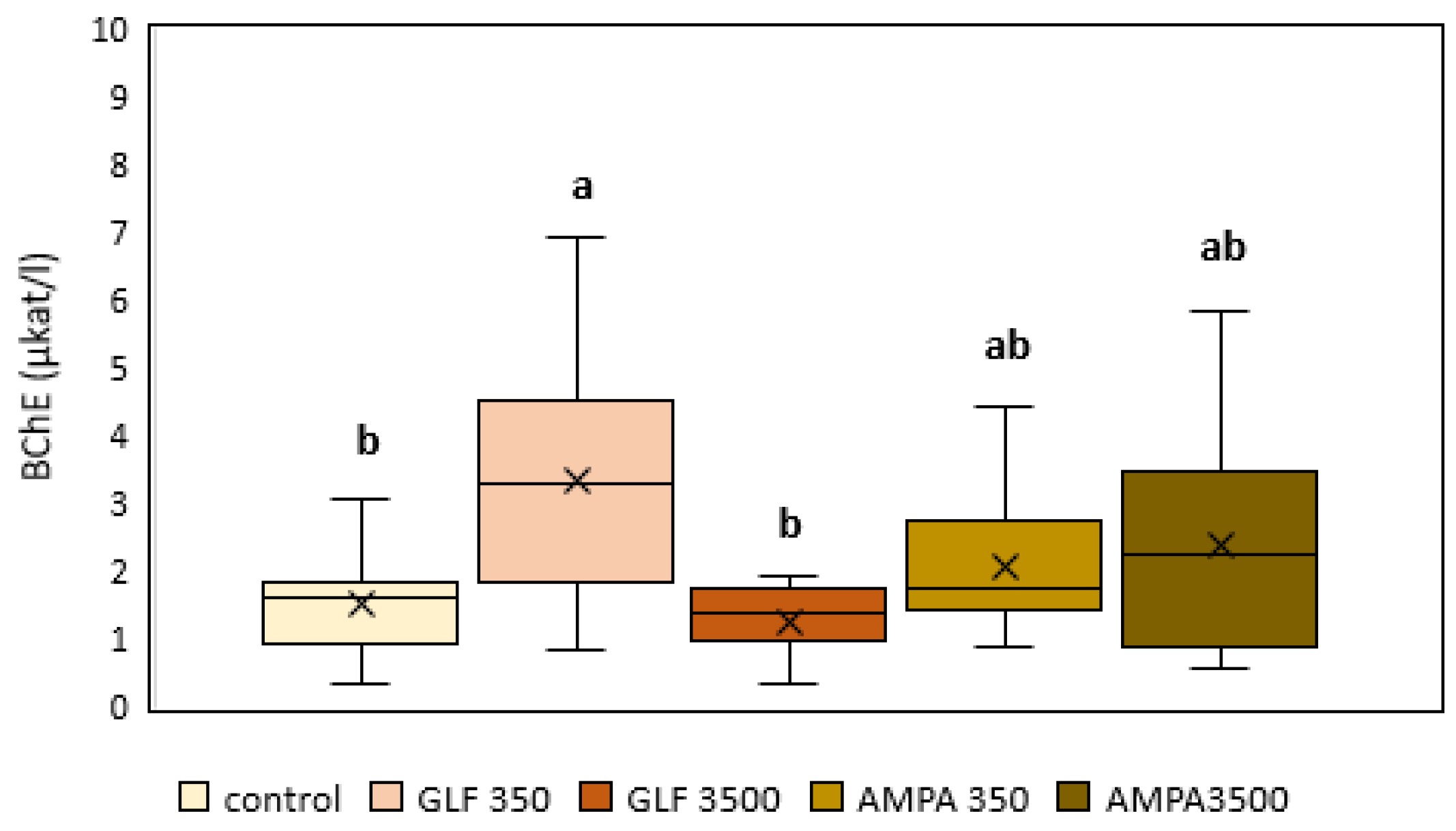

3.3. Butyrylcholinesterase

3.4. Gene Expression

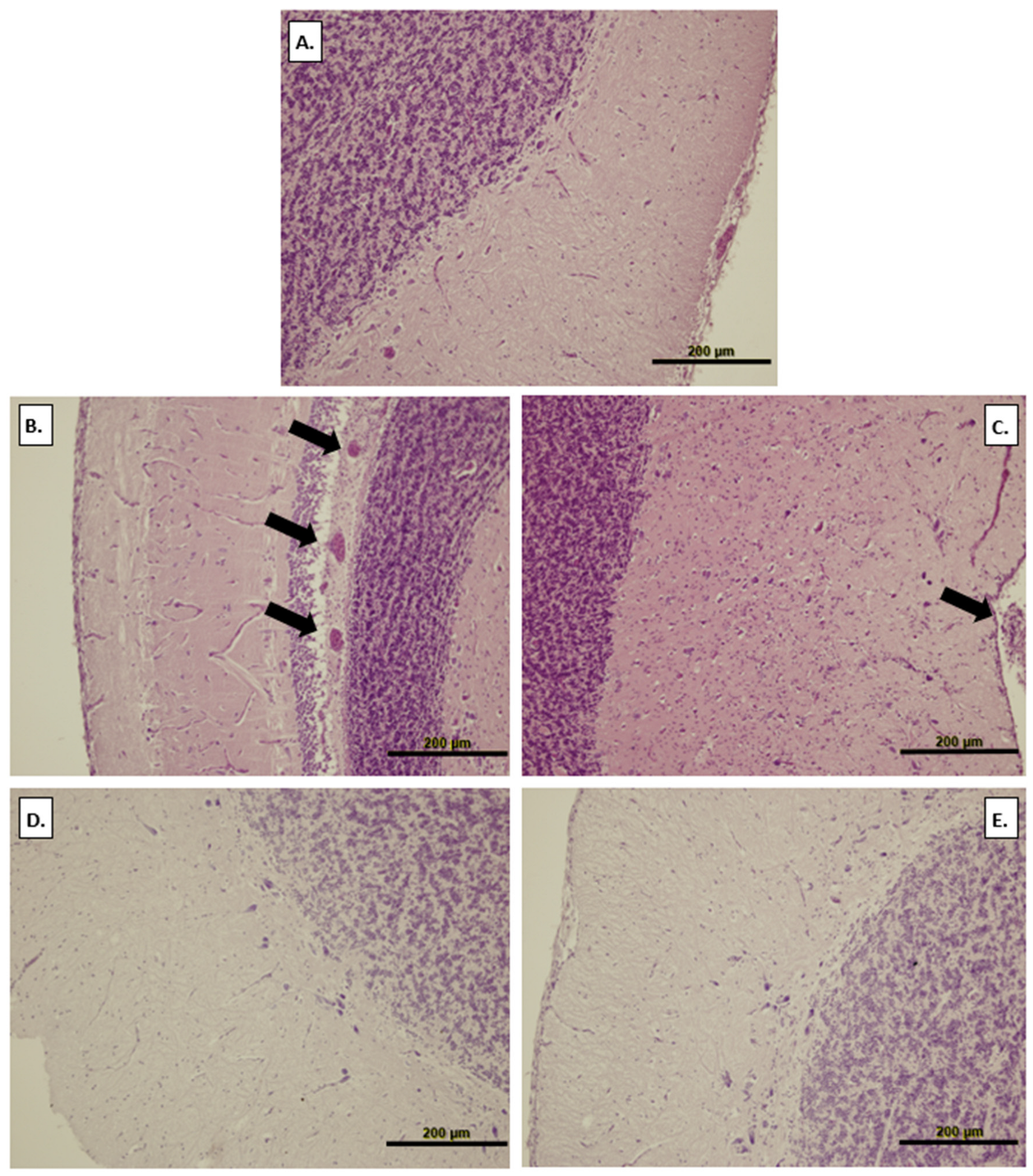

3.5. Brain Histology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AChE | acetylcholinesterase |

| AMPA | aminomethylphosphonic acid |

| AMPA 350 | experimental group exposed to 335.2 ± 27.0 µg/kg of AMPA |

| AMPA 3500 | experimental group exposed to 3441.0 ± 217.1 µg/kg of AMPA |

| BCA | bicinchoninic acid |

| BChE | butyrylcholinesterase |

| Ct | threshold cycle |

| DTNB | 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) |

| GLF | glyphosate |

| GLF 350 | experimental group exposed to 325.2 ± 31.6 µg/kg of glyphosate |

| GLF 3500 | experimental group exposed to 3310.0 ± 234.9 µg/kg of glyphosate |

| qRT-PCR | real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR |

References

- Szekacs, A.; Darvas, B. Forty years with glyphosate. In Herbicides-Properties, Synthesis and Control of Weeds; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; Volume 14, pp. 247–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, K.R.; Thompson, D.G. Ecological risk assessment for aquatic organisms from over-water uses of glyphosate. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2003, 6, 289–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresnakova, N.; Stara, A.; Velisek, J. Effects of glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA on aquatic organisms. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatyik, S.; Simon, G.; Olah, M.; Takacs, E.; Mesnage, R.; Antoniou, M.N.; Zaller, J.G.; Szekacs, A. Aquatic ecotoxicity of glyphosate, its formulations, and co-formulants: Evidence from 2010 to 2023. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costas-Ferreira, C.; Duran, R.; Faro, L.R. Toxic effects of glyphosate on the nervous system: A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babic, S.; Zelenika, A.; Macan, J.; Kastelan-Macan, M. Ultrasonic extraction and TLC determination of glyphosate in the spiked red soils. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2005, 70, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Brovini, E.M.; Cardoso, S.J.; Quadra, G.R.; Vilas-Boas, J.A.; Paranaiba, J.R.; Pereira, R.O.; Mendonca, R.F. Glyphosate concentrations in global freshwaters: Are aquatic organisms at risk? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 60635–60648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.J.; Pallet, K. The environmental fate and ecotoxicity of glyphosate. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2018, 29, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamy, L.; Barriuso, E.; Gabrielle, B. Glyphosate fate in soils when arriving in plant residues. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, B.B.; Giaquinto, P.C.; Silva, D.S.; Neto, C.M.S.; de Lima, A.A.; Darosci, A.A.B.; Portinho, J.L.; Carvalho, W.F.; Rocha, T.L. Ecotoxicology of glyphosate-based herbicides on aquatic environment. In Organic Pollutants; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesy, J.P.; Dobson, S.; Solomon, K.R.E. Ecotoxicological risk assessment for Roundup® herbicide. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2000, 167, 35–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, P.; Flores, F.; Mueller, J.F.; Carter, S.; Negri, A.P. Glyphosate persistence in seawater. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 85, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltracco, M.; Barbaro, E.; Morabito, E.; Zangrando, R.; Piazza, R.; Barbante, C.; Gambaro, A. Assessing glyphosate in water, marine particulate matter, and sediments in the Lagoon of Venice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16383–16391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Preliminary Ecological Risk Assessment in Support of the Registration Review of Glyphosate and Its Salts; U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; p. 318.

- Rendon-von Osten, J.; Dzul-Caamal, R. Glyphosate residues in groundwater, drinking water and urine of subsistence farmers from intensive agriculture localities: A survey in Hopelchén, Campeche, Mexico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, L.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Glyphosate, aminomethylphosphonic acid, and glufosinate ammonium in agricultural groundwater and surface water in China from 2017 to 2018: Occurrence, main drivers, and environmental risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandcoin, A.; Piel, S.; Baures, E. Aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) in natural waters: Its sources, behavior and environmental fate. Water Res. 2017, 117, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecna, J.; Zajicek, A.; Sanka, M.; Halesova, T.; Kaplicka, M.; Novakova, E. Pesticides in small agricultural catchments in the Czech Republic. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanton, N.; Cazenave, J.; Michlig, M.P.; Repetti, M.R.; Rossi, A. Biomarkers of exposure and effect in the armoured catfish Hoplosternum littorale during a rice production cycle. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Wang, L.; Xu, Q.; An, J.; Mei, Y.; Liu, G. Influence of glyphosate and its metabolite aminomethylphosphonic acid on aquatic plants in different ecological niches. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, E.; Sehonova, P.; Plhalova, L.; Blahova, J.; Svobodova, Z.; Faggio, C. Effects of glyphosate on early life stages: Comparison between Cyprinus carpio and Danio rerio. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 8542–8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.R.; Moraes, J.S.; Martins, C.M.G. Effects of the herbicide glyphosate on fish from embryos to adults: A review addressing behavior patterns and mechanisms behind them. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 251, 106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.; Bedrossiantz, J.; Ramirez, J.R.R.; Mayol, M.; Garcia, G.H.; Bellot, M.; Prats, E.; Garcia-Reyero, N.; Gomez-Canela, C.; Gomez-Olivan, L.M.; et al. Glyphosate targets fish monoaminergic systems leading to oxidative stress and anxiety. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shangguan, Y.; Zhu, P.; Sultan, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, X. Developmental toxicity of glyphosate on embryo-larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 236, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadikhah, D.; Varcheh, M.; Yalsuyi, A.M.; Forouhar Vajargah, M.; Mansouri Chorehi, M.; Faggio, C. Hematological and histopathological changes of juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) exposed to lethal and sublethal concentrations of roundup (glyphosate 41% SL). Aquac. Res. 2023, 1, 4351307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.M.; Caldas, S.S.; Primel, E.G.; da Rosa, C.E. Glyphosate adversely affects Danio rerio males: Acetylcholinesterase modulation and oxidative stress. Zebrafish 2017, 14, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Gan, J.; Yuan, K.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, G. Effects of aminomethylphosphonic acid on the transcriptome and metabolome of red swamp crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilherme, S.; Santos, M.A.; Gaivao, I.; Pacheco, M. DNA and chromosomal damage induced in fish (Anguilla anguilla L.) by aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA)–the major environmental breakdown product of glyphosate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8730–8739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheron, M.; Brischoux, F. Aminomethylphosphonic acid alters amphibian embryonic development at environmental concentrations. Environ. Res. 2020, 190, 109944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matozzo, V.; Fabrello, J.; Marin, M.G. The effects of glyphosate and its commercial formulations to marine invertebrates: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Songyan, L.; Honglin, L.; Di, H.; Yiqun, T.; Rui, Q.; Hailin, T.; Schichao, Z.; Yuanfei, L.; Yingping, H.; et al. Reproductive toxicity of glyphosate and its main metabolite aminomethyl phosphonic acid (AMPA) on zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2025, 385, 144548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance glyphosate. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, D.; Cavalli, V.L.L.O.; Rieg, C.E.H.; Domingues, J.T.; Dal-Cim, T.; Tasca, C.I.; Silva, F.R.M.B.; Zamoner, A. Mechanisms underlying the neurotoxicity induced by glyphosate-based herbicide in immature rat hippocampus: Involvement of glutamate excitotoxicity. Toxicology 2014, 320, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.M.; Carneiro, B.; Ochs, J. Glyphosate induces neurotoxicity in zebrafish. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 42, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Plata, I.; Giordano, M.; Diaz-Munoz, M. The herbicide glyphosate causes behavioral changes and alterations in dopaminergic markers in male Sprague-Dawley rat. NeuroToxicology 2015, 46, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattani, D.; Cesconetto, P.A.; Tavares, M.K.; Parisotto, E.B.; De Oliveira, P.A.; Rieg, C.E.H.; Leite, M.C.; Prediger, R.D.S.; Wendt, N.C.; Razzera, G.; et al. Developmental exposure to glyphosate-based herbicide and depressive-like behavior in adult offspring: Implication of glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress. Toxicology 2017, 387, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, C.E.; Bartos, M.; Bras, C.; Gumilar, F.; Antonelli, M.C.; Minetti, A. Exposure to a glyphosate-based herbicide during pregnancy and lactation induces neurobehavioral alterations in rat offspring. NeuroToxicology 2016, 53, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.A.; Ares, I.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Martinez, M.; Martinez-Larranaga, M.R.; Anadon, A. Neurotransmitter changes in rat brain regions following glyphosate exposure. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Herrera, N.; Mena, F.; Espinoza, M.; Romero, A. Neurotoxicity of organophosphate pesticides could reduce the ability of fish to escape predation under low doses of exposure. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Senthilkumaran, B. Recent advances in understanding neurotoxicity, behavior and neurodegeneration in siluriformes. Aquac. Fish. 2024, 9, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ding, W.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Zhu, G.; Ma, J. Single and combined effects of chlorpyrifos and glyphosate on the brain of common carp: Based on biochemical and molecular perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktug, G.U.L.; Yuce, P.A.; Gunal, A.Ç.; Faggio, C. Short-term effects of acetamiprid on common carp: Genotoxic, biochemical, and histopathological responses. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 118, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, A.; Muselik, J.; Rabiskova, M.; Dobiskova, R. Pharmaceutical Pellets Composition with a Particle Size of 0.1 to 10 mm for Oral Use for Aquatic Animals How to Prepare It. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CZ308210B6/en (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Mikula, P.; Hollerova, A.; Hodkovicova, N.; Doubkova, V.; Marsalek, P.; Franc, A.; Sedlackova, L.; Hesova, R.; Modra, H.; Svobodova, Z.; et al. Long-term dietary exposure to the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac and ibuprofen can affect the physiology of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) on multiple levels, even at “environmentally relevant” concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, D.; Andres, V.; Featherstone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Krohn, R.I.; Hermanson, G.T.; Mallia, A.K.; Gartner, F.H.; Provenzano, M.D.; Fujimoto, E.K.; Goeke, N.M.; Olson, B.J.; Klenk, D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985, 150, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusabio Technology, L.L.C. Fish Dopamine (DA) ELISA Kit. Available online: https://www.cusabio.com/ELISA-Kit/Fish-dopamineDA-ELISA-kit-118627.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Xing, H.; Han, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Xu, S. Alterations in mRNA expression of acetylcholinesterase in brain and muscle of common carp exposed to atrazine and chlorpyrifos. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 1666–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodkovicova, N.; Hollerova, A.; Caloudova, H.; Blahova, J.; Franc, A.; Garajova, M.; Lenz, J.; Tichy, F.; Faldyna, M.; Kulich, P.; et al. Do foodborne polyethylene microparticles affect the health of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalsuyi, A.M.; Vajargah, M.F.; Hajimoradloo, A.; Galangash, M.M.; Prokić, M.D.; Faggio, C. Evaluation of behavioral changes and tissue damages in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) after exposure to the herbicide glyphosate. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formicki, G.; Goc, Z.; Bojarski, B.; Witeska, M. Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity biomarkers in fish toxicology. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzegerald, J.A.; Konemann, S.; Krümpelmann, L.; Zupanic, A.; vom Berg, C. Approaches to test the neurotoxicity of environmental contaminants in the zebrafish model: From behavior to molecular mechanisms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebali, J.; Khedher, S.B.; Sabbagh, M.; Kamel, N.; Banni, M.; Boussetta, H. Cholinesterase activity as biomarker of neurotoxicity: Utility in the assessment of aquatic environment contamination. J. Integr. Coast. Zone Manag. 2013, 13, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.H.; Ku, H.O.; Kang, H.G.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Park, S.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Jang, I.; Bae, Y.C.; Woo, G.H.; et al. Acetylcholinesterase activity in the brain of wild birds in Korea—2014 to 2016. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 20, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colovic, M.B.; Krstic, D.Z.; Lazarevic-Pasti, T.D.; Bondzic, A.M.; Vasic, V.M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Pharmacology and toxicology. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, R.; Clasen, B.; Loro, V.L.; de Menezes, C.H.C.; Pretto, A.; Baldisserotto, B.; Santi, A.; de Avila, L.A. Toxicological responses of Cyprinus carpio exposed to a commercial formulation containing glyphosate. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 87, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares-Rubio, H.F.; Espinosa-Aguirre, J.J. Acetylcholinesterase activity in fish species exposed to crude oil hydrocarbons: A review and new perspectives. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merola, C.; Fabrello, J.; Matozzo, V.; Faggio, C.; Iannetta, A.; Tinelli, A.; Crescenzo, G.; Amorena, M.; Perugini, M. Dinitroaniline herbicide pendimethalin affects development and induces biochemical and histological alterations in zebrafish early-life stages. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braz-Mota, S.; Sadauskas-Henrique, H.; Duarte, R.M.; Val, A.L.; Almeida-Val, V.M.F. Roundup exposure promotes gills and liver impairments, DNA damage and inhibition of brain cholinergic activity in the Amazon teleost fish Colossoma macropomum. Chemosphere 2015, 135, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Ruan, P.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Li, X. Biochemical and molecular impacts of glyphosate-based herbicide on the gills of common carp. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.G.; Greig, N.H.; Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.L.; Enz, A.; Darvesh, S. Cholinesterases: Roles in the brain during health and disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2005, 2, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Moore, S.W. Why has butyrylcholinesterase been retained? Structural and functional diversification in a duplicated gene. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, J.B.; Bastos, V.C.; Silva Filho, M.V.; Machado, O.L.T.; Salles, C.M.C.; De Simone, S.G.; Bastos, J.C. A novel butyrylcholinesterase from serum of Leporinus macrocephalus, a neotropical fish. Biochimie 2006, 88, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazala Mahboob, S.; Ahmad, L.; Sultana, S.; Alghanim, K.; Al-Misned, F.; Ahmad, Z. Fish cholinesterases as biomarkers of sublethal effects of organophosphorus and carbamates in tissues of Labeo rohita. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2014, 28, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.S.; Sandrini-Neto, L.; Domenico, M.D.; Prodocimo, M.M. Pesticide effects on fish cholinesterase variability and mean activity: A meta-analytic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blahova, J.; Mikula, P.; Marsalek, P.; Svobodova, Z. Biochemical and antioxidant responses of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to sublethal concentrations of the antiepileptic and analgesic drug gabapentin. Vet. Med. 2025, 70, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Tan, Y. Hormetic response of cholinesterase from Daphnia magna in chronic exposure to triazophos and chlorpyrifos. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 23, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geetha, N. Mitigatory role of butyrylcholinesterase in freshwater fish Labeo rohita exposed to glyphosate based herbicide Roundup®. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 2030–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsagade, V.G. Dopamine system in the fish brain: A review on current knowledge. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2020, 8, 2549–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.C. The neurobiology of mutualistic behavior: The cleaner fish swims into the spotlight. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, B.; Nunes, B. Reliability of behavioral test with fish: How neurotransmitters may exert neuromodulatory effects and alter the biological responses to neuroactive agents. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, D.F.; Soares, M.C.; Taborsky, M. Dopamine modulates social behaviour in cooperatively breeding fish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 550, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, L.S.; De Souza, T.L.; de Morais, T.P.; de Oliveira Ribeiro, C.A. Toxicity of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) to the early stages of development of Steindachneridion melanodermatum, an endangered endemic species of Southern Brazil. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 102, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Hu, X.; Qi, D.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, S.; Hong, Y. Dopaminergic system disruption induced by environmentally realistic glyphosate leads to behavioral alteration in crayfish, Procambarus clarkii. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 301, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellot, M.; Carrillo, M.P.; Bedrossiantz, J.; Zheng, J.; Mandal, R.; Wishart, D.S.; Gómez-Canela, C.; Vila-Costa, M.; Prats, E.; Pina, B.; et al. From dysbiosis to neuropathologies: Toxic effects of glyphosate in zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 270, 115888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.A.A.; da Costa Klosterhoff, M.; Romano, L.A.; Martins, C.D.M.G. Histological evaluation of vital organs of the livebearer Jenynsia multidentata (Jenyns, 1842) exposed to glyphosate: A comparative analysis of Roundup® formulations. Chemosphere 2019, 217, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhunmwunse, N.O.; Ekaye, S.A.; Ainerua, M.O.; Ewere, E.E. Histopathological changes in the brain tissue of Africa catfish exposure to glyphosate herbicide. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2014, 18, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Brain | Gill |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.0203 ± 0.0043 a | 0.0003 ± 0.0000 a |

| GLF 350 | 0.0002 ± 0.0000 c ↓ | 0.0004 ± 0.0000 ab |

| GLF 3500 | 0.0009 ± 0.0007 cd ↓ | 0.0003 ± 0.0000 ab |

| AMPA 350 | 0.0062 ± 0.0038 bd ↓ | 0.0003± 0.0000 ab |

| AMPA 3500 | 0.0113 ± 0.0047 b ↓ | 0.0004 ± 0.0001 b ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferrara, S.; Mikula, P.; Hollerova, A.; Marsalek, P.; Tichy, F.; Svobodova, Z.; Faggio, C.; Blahova, J. From Genes to Organs: A Multi-Level Neurotoxicity Assessment Following Dietary Exposure to Glyphosate and Its Metabolite Aminomethylphosphonic Acid in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11877. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211877

Ferrara S, Mikula P, Hollerova A, Marsalek P, Tichy F, Svobodova Z, Faggio C, Blahova J. From Genes to Organs: A Multi-Level Neurotoxicity Assessment Following Dietary Exposure to Glyphosate and Its Metabolite Aminomethylphosphonic Acid in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11877. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211877

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrara, Serafina, Premysl Mikula, Aneta Hollerova, Petr Marsalek, Frantisek Tichy, Zdenka Svobodova, Caterina Faggio, and Jana Blahova. 2025. "From Genes to Organs: A Multi-Level Neurotoxicity Assessment Following Dietary Exposure to Glyphosate and Its Metabolite Aminomethylphosphonic Acid in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio)" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11877. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211877

APA StyleFerrara, S., Mikula, P., Hollerova, A., Marsalek, P., Tichy, F., Svobodova, Z., Faggio, C., & Blahova, J. (2025). From Genes to Organs: A Multi-Level Neurotoxicity Assessment Following Dietary Exposure to Glyphosate and Its Metabolite Aminomethylphosphonic Acid in Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11877. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211877