Abstract

The development of new technologies, improved by advances in artificial intelligence, has enabled the creation of a new generation of applications in different scenarios. In medical systems, adopting AI-driven solutions has brought new possibilities, but their effective impacts still need further investigation. In this context, a chatbot prototype trained with large language models (LLMs) was developed using data from the Santa Catarina Telemedicine and Telehealth System (STT) Dermatology module. The system adapts Llama 3 8B via supervised Fine-tuning with QLoRA on a proprietary, domain-specific dataset (33 input-output pairs). Although it achieved 100% Fluency and 89.74% Coherence, Factual Correctness remained low (43.59%), highlighting the limitations of training LLMs on small datasets. In addition to G-Eval metrics, we conducted expert human validation, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative aspects. This low factual score indicates that a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) mechanism is essential for robust information retrieval, which we outline as a primary direction for future work. This approach enabled a more in-depth analysis of a real-world telemedicine environment, highlighting both the practical challenges and the benefits of implementing LLMs in complex systems, such as those used in telemedicine.

1. Introduction

Technologies have significantly shaped the field of healthcare, revolutionizing how medical services are delivered and improving patient outcomes [1]. Although there is a well-defined development path, it was only in recent decades that the integration of digital technologies has transformed healthcare with the adoption of more efficient, precise, and patient-centered systems [2,3]. The resulting scenario has been a healthcare landscape that is increasingly adaptive to global needs, enabling advancements in areas such as telemedicine, wearable health monitoring, and data-driven decision-making.

In this complex scenario, telemedicine has played a crucial role in expanding access to health services, especially in isolated communities [4,5]. Emerging in the 1960s, its initial proposal was to offer remote medical care to populations with limited access to health services [6]. Later, with advances in computer and networking technologies, new functionalities have been added to telemedicine systems [7,8]. In recent years, promising innovations in artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and computer networks have brought significant evolution to telemedicine, enabling activities such as “telehealth consultation” and teleconferences aimed at complex diagnoses [9,10].

The evolution of artificial intelligence has allowed a whole new set of applications. Particularly, the advancement of large language models (LLMs) has opened up new possibilities in human–machine interactions, with virtual assistants earning a prominent place in this decade [11]. Overall, these models are trained to follow human instructions through language, supporting data knowledge processing but also the execution of various tasks. Therefore, the integration of LLMs into complex systems expands their functionalities by allowing the creation of innovative solutions, such as chatbots for technical support, automation of clinical processes, and information retrieval, contributing significantly to the efficiency and quality of health services [12].

While the use of LLM chatbots in healthcare continues to grow [13,14], there is also significant potential to enhance the capabilities of telemedicine systems. Recently, several biomedical chatbots have emerged, such as DoctorGLM, Clinical Camel, PMC-LLaMa, Med-Alpaca, ChatDoctor, and Huatuo [15], each one addressing a particular medical scenario or population target. Due to the complexities of telemedicine, especially in a developing world, the adoption of such chatbots can be a valuable resource.

The present article focuses on STT-Chat, a chatbot developed to meet the specific needs of telemedicine assistance in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Santa Catarina’s Telemedicine and Telehealth System (STT) is a comprehensive tool that allows synchronous and asynchronous telemedicine and telehealth services [16]. It is a fully operational digital service that supports the population throughout the State. Despite the system’s effectiveness in adopting the public health policies of the region, some challenges are posed for effective data retrieval: the increasing complexity from ever-growing volumes of performed tests and the high number of internal users. Because of this, it is more challenging for system users to quickly locate information and efficiently get technical help

There are many benefits to using chatbots in telemedicine, as some recent results have brought important reflections for many practical scenarios [17,18]. For the particular case of STT, the technical manuals to support users are distributed across different documents, which can make it difficult to quickly locate specific information. Yet, when this data is used to create a particular chatbot, relevant information can be quickly accessed, leading to improved system efficiency. Therefore, STT-Chat emerges as a promising tool in this context.

The practical details of implementing this chatbot and its initial evaluation are addressed in the present article. Its main contributions include (1) the development and fine-tuning of STT-Chat with the Llama 3 8B model on a domain-specific, proprietary dataset (33 pairs), via supervised fine-tuning with QLoRA to align with a conversational style and instruction-following in the STT context rather than to encode comprehensive factual knowledge; (2) a crucial architectural insight, supported by the low Factual Correctness score (43.59%), demonstrating that a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) component is essential for factual retrieval; and (3) a systematic evaluation of the chatbot’s construction and application in a real telemedicine setting in a developing country.

The next sections of this article are organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 details the methodology, including the dataset construction (Section 3.1) and the fine-tuning procedure (Section 3.2). Section 4 presents the experimental results. Section 5 discusses the findings and limitations. Finally, Section 6 concludes this paper.

2. Related Works

The integration of artificial intelligence into the healthcare domain has been driven by numerous compelling factors. As seen in recent years, many different scenarios have benefited from AI tools, with LLM-based chatbots gaining relevance. This section reviews the recent literature in this area, highlighting recent studies in this field that have influenced our investigation.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, healthcare systems are under heavy pressure, facing challenges to manage the increased demand on their infrastructures [19,20]. In this context, there is a need for innovative solutions to overcome the limitations and challenges imposed by this post-pandemic scenario. Due to the new dynamics resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic [21], telemedicine and digital transformation have been largely promoted. This “transformation” influenced by COVID-19 has happened while new AI-based tools started to emerge, helping to pave the way for a new generation of healthcare services. The resulting scenario has favored more effective and affordable AI tools to support complex applications, like those experienced by telemedicine in developing countries.

Some recent works can be highlighted. The work in Ref. [22] presents a healthcare chatbot, the eHealth AI Chatbot, designed to support a data system aimed at helping patients and medical staff. Users can consult medical information with privacy and security through a chatbot interface that uses the Matrix protocol for secure and decentralized communication. The answers to the posted questions are provided by large language models (LLMs), which check for restricted access to patient information and use various methods to provide correct answers, based on patient-specific data.

Recently, a study in Indonesia investigated the use of LLMs to address a growing HIV epidemic, a health problem exacerbated by geographic and sociocultural challenges [23]. The research proposed the integration of language models into large-scale telehealth (TH) platforms, optimizing clinical consultations. The study reported that in the context of HIV in Indonesia, cases showed better adherence to treatment, with increased testing and decreased HIV transmission rates, in addition to generating epidemiological data [23]. The technology could eventually be expanded as a triage and referral channel for care, expanding the reach of patients in healthcare services [23].

Another relevant work is LLaVA-Med, a large multimodal model focused on biomedicine [15]. The development of LLaVA-Med was based on a dataset of language and biomedical image instructions. It uses a self-instruction methodology to build a data curation pipeline, with the support of ChatGPT-4 and external data. The results of LLaVA-Med were promising, surpassing the capabilities of previous models, including those considered as Supervised State-Of-The-Art.

Authors in Ref. [24] developed the BioMedLM, a language model trained exclusively on biomedical abstracts and articles from “The Pile”, a dataset with 2.7 billion parameters, trained exclusively on biomedical texts. The primary objective in developing this model was to create a smaller, more specialized alternative with fewer parameters, thereby reducing the computational demands typical of large language models [24]. BioMedLM is an autoregressive model, similar to GPT, trained exclusively on PubMed abstracts and articles. As a result, the model can produce satisfactory and useful answers, competing with larger models, as it achieves a score of 57.3% on the MedMCQA (dev) and 69.0% on the MMLU Medical Genetics exam [24].

The Med-PaLM 2, developed by Google Research, is a language model specialized in the medical domain that has achieved 86.5% on the MedQA dataset, outperforming its predecessor by over 19% [25]. In a comparative evaluation of 1066 questions, physicians demonstrated a preference for model-generated responses over those provided by human professionals, highlighting its potential for advanced clinical applications [25].

The BioBERT model stands out as a pre-trained language model designed specifically for biomedical text-mining tasks, as presented in Ref. [26]. As the volume of documents and information in the biomedical field continues to grow, it becomes essential to apply advanced natural language processing techniques to extract strategic information efficiently. BioBERT focuses primarily on tasks such as biomedical named entity recognition, relation extraction, and question answering, supporting the understanding of complex biomedical texts and enhancing information retrieval [26]. This solution was created before the age of LLM-based chatbots, bringing important initial contributions.

Babylon Health, founded in 2013 by Dr. Ali Parsa, who has extensive experience in the healthcare field, was one of the first companies to revolutionize telemedicine, integrating virtual consultations with AI-assisted diagnostics. The Babylon app allows users to report their symptoms through a chatbot, where an AI model evaluates the information entered and returns recommendations to patients without the need for doctors [27]. The company emphasizes that this service should only be used for mild cases and is especially useful for people with busy lives who cannot attend a doctor’s office in person. In more serious cases, the service recommends that the patient seek medical attention in person for a proper evaluation [27].

STT-Chat, trained with LLMs, differentiates itself from other solutions by its central focus on supporting information retrieval and technical assistance in telemedicine systems. While other medical chatbot approaches are geared towards clinical consultations, STT-Chat is a fine-tuned and specialized model that supports information retrieval within the STT.

This approach can be expanded to other system modules, as long as a specialized dataset is developed to perform LLM training, highlighting its great potential. It is possible to explore this technology in the system to design a multimodal model to support the tracking of lesions and dermatitis in the area of dermatology, promoting innovation in remote care.

Table 1 summarizes the reviewed works.

Table 1.

Related works that exploited AI to support medical queries.

Furthermore, it should be noted that most related studies focus on clinical consultations or large-scale biomedical benchmarks, usually supported by large biomedical databases. In contrast, STT-Chat was developed from a specialized dataset, created from the technical documentation of the Santa Catarina Telemedicine and Telehealth System (STT), with a specific focus on information retrieval and technical support for internal users.

3. Methods

According to the defined objectives, the proposed approach is centered on the construction of an LLM-based chatbot to support information retrieval in telemedicine systems in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. To this end, the following steps were adopted:

- 1.

- Development of a specialized dataset using the “golden corpus” technique, based on questions and answers aimed at user technical support;

- 2.

- Fine-tuning of the pre-trained Llama 3 model [29] with the developed dataset, adapted to the STT-Dermatology domain;

- 3.

- Quantification of the adjusted model to optimize its size and allow its use on devices with limited computational resources;

- 4.

- Compilation of the adjusted model using the Ollama framework [30] and integration into a graphical interface through OpenWebUI [31].

The next subsections further discuss the key aspects of the proposed approach.

3.1. Dataset

In the context of LLMs, it is widely recognized that a high-quality, noise-free, domain-focused dataset will result in a more efficiently tuned model aligned with the desired objective [32]. Furthermore, developing a custom dataset offers significant advantages over data widely available on the internet, such as greater control over the content, improvements in model performance, and protection against Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs)—attacks that aim to infer information about the training data from the model’s results.

One of the most important steps to obtain an adjusted LLM model was the construction of a specialized dataset that would be meaningful within the STT telemedicine system. One of the components of the STT system is the STT-Dermatology module. To assist internal users, this specific module has technical documents that guide tasks such as filling out reports and using available resources. These documents, which cover the period up to 2024, contain only operational instructions and frequently asked questions from internal users. Therefore, the material does not include sensitive or identifiable information and is fully anonymized. We strictly adhere to the principles of the Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD), ensuring that privacy and confidentiality are fully respected at all stages of the research [33].

While the dataset demonstrates promising capabilities due to its curation, it has significant limitations. The dataset, consisting of only 33 question-and-answer tuples, proved insufficient to perform meaningful fine-tuning on a large language model like Llama 3 8B. Therefore, the fine-tuning was intended to align a conversational style and instruction-following with the STT-Dermatology context, rather than incorporating factual knowledge into the model. It is important to highlight that the small number of tuples is directly related to the limited amount of retrievable information in the STT technical documents, which contained only three pages of frequently asked questions from internal users and their respective answers. Due to the small size of the dataset, it was not divided into training, validation, and testing subsets, as this separation would further reduce the amount of available data and compromise the fine-tuning process.

In the future, to mitigate this gap, the support team responsible for serving these users could continually feed new documentation, enabling, over time, the construction of a more robust and representative dataset with a larger number of tuples for future iterations of the model.

Therefore, to create the dataset, information was manually collected from these technical documents using the golden corpus technique which was then organized into a structured dataset with the Pandas library, in the format X (question) and Y (answer). The data was configured as chat templates. After development, the dataset was made available on the Hugging Face platform, optimizing its use and sharing and allowing its instantiation through an inference API, using tags in the following structure:

[INST] Question [/INST] Answer

The dataset is openly available at https://huggingface.co/datasets/Brunapupo/teledermato-data, accessed on 1 October 2025. The tuples are in Portuguese, the study’s native language. However, they were translated into English to reach the target audience.

After developing the dataset, it was uploaded to the Hugging Face platform in the .parquet format, widely used for handling large volumes of data. This made it possible to use the specialized dataset for technical assistance to users of the STT-Dermatology module via the Hugging Face inference API, in the same way that the inference APIs for large language models are used on the platform.

3.2. Fine-Tuning the Chatbot

The fine-tuning process was conducted using the Hugging Face ecosystem. The pre-trained model, “meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B”, was instantiated through the inference API and fine-tuned with the specialized STT dataset. Given the small size of the dataset (33 pairs), fine-tuning was primarily aimed at aligning conversational style and instruction-following to the STT-Dermatology context, rather than to encode factual knowledge.

According to Saahil Afaq and Dr. Smitha Rao [34], an epoch represents a complete pass through the entire dataset, during which the model’s weights are updated at each simulation cycle. When the same dataset is processed again, a new epoch begins. To achieve satisfactory results, it is essential to be aware of two main issues: overfitting, which occurs when the model learns excessively, including the noise present in the data, thus compromising its performance on new samples; and underfitting, which arises when the model fails to adequately learn the patterns from the training data.

Moreover, the strategic definition of hyperparameters has a significant influence on training outcomes. In this study, only one epoch was used, considering the critical size of the dataset, in order to reduce the risk of overfitting and preserve the model’s generalization capability.

Within this methodological framework, we acknowledge a factual anchoring gap that should be addressed by a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) component, which is not included in the present version but is identified as the natural path for evolution. As a result, we obtained a model aligned with the system’s needs and implemented it entirely in Python 3.11.0. Below, we detail the training configurations and adjustments that underpin the reported results:

- Instantiation of specialized model and dataset: The pre-trained model meta-llama/Meta-Llama-3-8B was combined with the specialized dataset teledermato-data and instantiated via an API.

- Loading the dataset: The dataset was loaded using the Transformers library with the load-dataset function. Only the training data was processed, ensuring focus on examples relevant to fine-tuning.

- Quantization with QLoRA: The model was quantized to 4 bits using the QLoRA technique, significantly reducing memory consumption. This step was essential to optimize computational use and speed up the training process.

- Tokenizer configuration: The tokenizer has been tuned to convert text into model-compatible numeric tokens, as well as define padding tokens and ensure consistency in input length.

- Optimization with LoRA: The Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique was used to optimize the fine-tuning process, reducing computational costs without compromising model quality.

- Hyperparameter configuration: Fundamental hyperparameters such as batch size, learning rate, number of epochs, and evaluation strategy were defined to ensure training efficiency and performance.

- –

- Output directory: output_dir=new_model

- –

- Number of epochs: 1

- –

- Training batch size: per_device_train_batch_size: 1

- –

- Evaluation batch size: per_device_eval_batch_size: 1

- –

- Gradient accumulation steps: 2sq

- –

- Optimizer: paged_adamw_32bit

- –

- Evaluation strategy: steps

- –

- Evaluation steps: 0.2

- –

- Logging steps: 1

- –

- Warmup steps: 10

- –

- Logging strategy: steps

- –

- Learning rate: 2 × 10−4

- –

- fp16: False

- –

- bf16: False

- –

- Sequence length grouping: True

- –

- Monitoring tool: wandb

- Supervised training: Training was performed using SFTTrainer, which integrated the model, dataset, tokenizer, and configured hyperparameters. The maximum sequence length (max-seq-length) was set to 512 to avoid GPU memory limitations.

- Saving and sharing the model: After fine-tuning, the adjusted model was saved locally and uploaded to the Hugging Face Hub, allowing its storage and access via an API for practical use.

- Compiling the model with Graphical Interface using Ollama and Open WebUI: To create a graphical interface and access it through a local URL, OpenWebUI was used together with Ollama to run the adjusted model simply and efficiently.

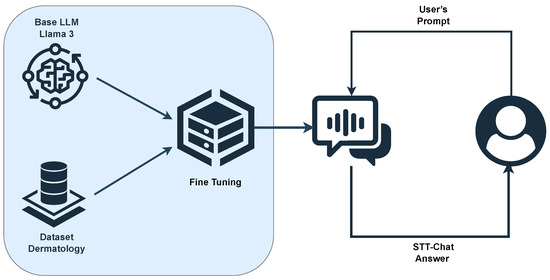

Figure 1 presents the flow of the fine-tuning process performed on the pre-trained Llama 3 model, using the created STT-Dermatology dataset. The illustration highlights the main steps, from the preparation of the dataset to the development of the fine-tuned and specialized model for the STT-Dermatology domain.

Figure 1.

Processing pipeline of the proposed approach.

4. Results

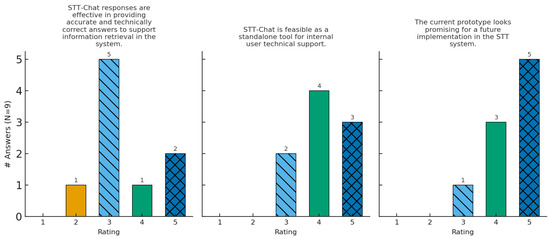

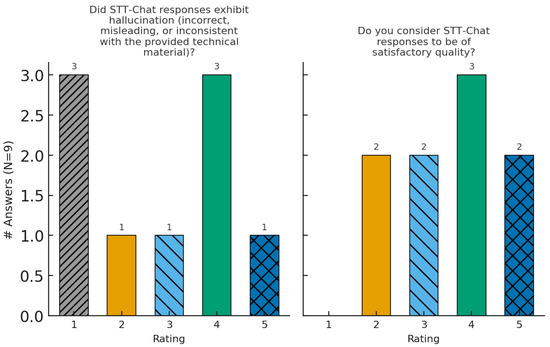

The results of the experimental prototype are presented in Table 2 and in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Although these data can be explored from different perspectives, in this work we adopt two complementary approaches: (i) an automatic evaluation with G-Eval, a framework that uses GPT-4 with chain-of-thought to fill out a form and considers scores of Correctness, Relevance, Conciseness, Fluency, Harmfulness, and Coherence for the answers. This method has already been demonstrated by Spearman with human judgments in the summarization task [35]; (ii) a qualitative evaluation conducted by a panel of experts.

Table 2.

Pass rates of STT-Chat responses evaluated using G-Eval metrics.

Figure 2.

Distribution of expert-panel ratings for Q1–Q3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of expert-panel ratings for Q4–Q5 (same axes as Figure 2).

The human evaluation performed by the experts was conducted independently from the automated analysis performed with G-Eval. The expert panel, composed of members of the STT technical team with over ten years of experience at the institution, did not have prior access to the results of the quantitative analyses produced by G-Eval, and their opinions were exclusively qualitative. In this context, assertiveness was interpreted based on both evaluation approaches.

4.1. Automatic Evaluation (G-Eval)

Table 2 summarizes the pass rates achieved with G-Eval. STT-Chat reached perfect Fluency (100%) and very high scores in Safety (97.44%) and Coherence (89.74%), indicating that the generated responses are well-formed and logically consistent. Relevance was also high (82.05%), showing that the system generally stays on topic. In contrast, Conciseness scored 61.54% and Correctness only 43.59%, suggesting that several responses were overly verbose or contained factual inaccuracies that should be corrected in future iterations.

The total number of samples was 39 responses (n = 39), generated by the STT-Chat model from test-set prompts and automatically evaluated using the G-Eval (GPT-4) framework across the six metrics presented in Table 2. All reported percentages correspond to the proportion of approved responses relative to this total.

4.2. Initial Results

Table 3 presents an initial question about the dermatology module of the STT system (referred herein as STT-Dermatology).

Table 3.

First interaction.

Response Analysis: The answer provided by the chatbot is correct, considering that STT-Dermatology is focused on sending reports and sharing dermatological images remotely. This functionality allows medical professionals to perform diagnoses remotely, highlighting the usefulness of the system in telemedicine contexts.

Table 4 presents the second interaction.

Table 4.

Second interaction.

Response Analysis: The chatbot was able to identify the question and provide a correct answer, highlighting the importance of detailed image review in the reporting process. The answer was accurate in explaining that the system’s tools allow for careful analysis of images, ensuring proper evaluation of exams.

Then, a third prompt was created and submitted, as described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Third interaction.

Response Analysis: This example shows that, even with grammatical errors, the chatbot was able to identify and respond correctly. An interesting observation is that the dataset does not include information that the preview image of the skin submitted for analysis appears next to the form in the system. In this way, the pre-trained Llama3 model brought additional information from the general data present in its original training, which occurred due to the fine-tuning process.

Finally, Table 6 summarizes some examples of questions related to common user prompts in the context of STT-Dermatology. It is possible to observe that, in general, the responses were correct and coherent, without presenting “hallucinations”.

Table 6.

Some common questions questions and answers for the STT-Chat.

Response Analysis: It can be seen that although the answers are correct and consistent with the questions, one point for improvement is the lack of detailed step-by-step instructions, as would be necessary, for example, to fill out a report. This gap occurs because the dataset needs to be fed with specific information about the processes and the step-by-step process for completing tasks and functionalities, such as sending images and issuing dermatological reports.

In short, the initial evaluation demonstrated a potential effectiveness of STT-Chat in understanding user interactions, even in the face of writing errors and generalized questions outside the scope of the domain. Furthermore, the chatbot proved to be consistent in providing accurate responses, without losing the general context, thereby proving its capability of supporting the recovery of relevant information within the STT system.

4.3. Expert-Panel Evaluation

The selection criteria for the evaluators included STT employees with 5 to 20 years of experience, professionals who have in-depth knowledge of the system. The participants were software developers, project managers, and other stakeholders directly involved in the management and maintenance of STT.

With this group, the aim was to verify the feasibility of integrating the chatbot into STT and analyzing its effectiveness in providing technical support to internal users, such as reporting physicians. In addition, the intention was to measure the quality of the responses generated and identify areas for improvement in the prototype.

To collect feedback from the team, a structured survey form was created, consisting of questions that addressed specific functionalities and usability aspects of the tool. Each question was evaluated on a Likert scale from 1 (minimum) to 5 (maximum), allowing for a quantitative analysis of the responses. The form was applied to the technical team in November 2024.

Below, a brief guided reading of Figure 2 and Figure 3 is presented. The Figures gather histograms, each corresponding to the questions Q1–Q3 of the questionnaire. The x axis shows the Likert scale from 1 (absence) to 5 (best evaluation), while the y axis indicates the absolute number of responses.

Table 7 Presents the five survey questions (Q1–Q5) used in the expert-panel evaluation, which was conducted with nine STT professionals (n = 9).

Table 7.

Survey questions used in the expert-panel evaluation (Q1–Q5).

Table 8 summarizes the pass rates achieved with G-Eval. STT-Chat reached perfect Fluency (100 %) and very high scores in Safety (97.44 %) and Coherence (89.74 %), indicating that the generated responses are well-formed and logically consistent. Relevance was also high (82.05 %), showing that the system generally stays on topic. In contrast, Conciseness scored 61.54 % and Correctness only 43.59 %, suggesting that several responses were overly verbose or contained factual inaccuracies that should be corrected in future iterations.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) for each survey question answered by the expert panel ().

Overall, analysis of the results of this validation process showed that the use of large language models (LLMs) in telemedicine systems is feasible and can provide high-impact support on platforms such as STT. The predominantly positive evaluations, combined with the low standard deviations observed in most questions, reinforce the acceptance and perception of technical feasibility among the participants, professionals directly involved in the operation and maintenance of the system. Although the present study did not employ a formal inter-rater agreement metric, the low standard deviation observed in the key questions (such as Q2 and Q3) indicates a consistent level of agreement among the experts’ judgments, thereby reinforcing the reliability of the qualitative assessment.

However, there is still room for improvement, since some responses presented hallucinations (incorrect or inconsistent answers). This problem is inherent to LLMs, which have the characteristic of generating different answers for the same prompt, which can result in broader or less accurate information. In any case, the behavior of an LLM can be adjusted by configuring decoding parameters such as temperature, top-k, and top-p, that control the randomness and accuracy of the generated answers.

In summary, the validation results highlighted that STT-Chat is a promising prototype, with great potential to assist the technical support of the STT system. However, its implementation requires adjustments to ensure more accurate answers, free from hallucinations and aligned with the specific domain of STT, fully meeting user expectations and the requirements of the telemedicine area.

5. Discussion

After performing the LLM-based construction and validation, all proposed objectives were achieved. The first one was the development of a specialized dataset, based on the technical documentation of the STT-Dermatology module of the STT system. This step was fundamental to support the fine-tuning process and ensure that the chatbot could provide accurate and relevant responses.

Although the created dataset was essential for adapting the model to the STT domain and aligning its responses with the specific communication style of the telemedicine environment, it was possible to identify some technical limitations. The considered technical manuals did not contain many detailed instructions on the processes and steps required to complete the tasks and functionalities, such as sending images and issuing dermatological reports. This limitation resulted in responses with different levels of detail, where some presented a detailed step-by-step process, while others were more objective and succinct.

The work would also benefit from the expansion of the dataset, which currently has only 33 tuples. This reduced number limits domain coverage and may compromise the model’s generalizability. Due to these limitations, the role of fine-tuning is limited to adapting the model to a communication style and its ability to follow specific instructions in the STT domain, without the goal of incorporating factual knowledge into the pre-trained Llama 3 8B model. This shortcoming directly resulted in the low Factual Correctness score (43.59%), a classic failure mode for Factual Retrieval with small datasets. To overcome this problem in future steps, we recommend adopting an RAG pipeline, an essential and still missing component for achieving accurate and scalable information retrieval. The current prototype represents only the fine-tuned generation layer, which will serve as the basis for integrating this pipeline.

In parallel, it is recommended to also update technical manuals, which must be supplemented by additional information from support teams, including more detailed instructions and well-defined steps for performing system tasks. This approach would allow for the creation of a more comprehensive and instructive dataset, resulting in a higher quality-adjusted model, capable of offering more complete responses aligned with user needs.

The AI training was carried out by fine-tuning the pre-trained Llama 3 model, with the specialized dataset developed in this work. However, obtaining the computational power necessary to train an LLM was one of the main challenges faced. Initially, the scripts were executed on an A100 GPU in Google Colab, which, although efficient, was expensive and had limited availability. This restriction resulted in long waiting times to test the code and models of the Llama family, which in turn delayed the progress of the research.

This limitation was overcome by accessing a more robust computing infrastructure, provided by a Jupyter notebook equipped with two NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 cards, accessible through the PyTorch framework (version 2.1.0, CUDA 11.8), totaling 48 GB of VRAM. This solution allowed the successful completion of the AI training, resulting in a refined and specialized model for STT-Dermatology technical manuals.

The adjusted model revealed some points of improvement that are recommended for application during AI training. One of these points is the use of decoding parameter settings, such as temperature, top-k, and top-p, which control the randomness and accuracy of the generated responses. Such settings can contribute to responses being more aligned and accurate in the context of the STT system.

Another possibility for improvement was the loss of context observed after implementing the adjusted model in a graphical interface. During the validation process, it was found that the model, when executed locally in Ollama, produced more complete and contextualized responses. However, when integrated into a graphical interface, the responses became more generic, with a greater propensity for hallucinations and loss of context.

In addition, ethical and data privacy issues are key aspects that must be considered when implementing large-scale language models in medical systems, such as STT. There are ongoing discussions around the world about how regulators should address the legal and ethical challenges of using LLMs in healthcare [36]. Training large-scale language models primarily uses data mined and extracted from digital sources, often containing personal information.

Access to such data, especially those related to healthcare, requires approval from an ethics committee, justifying its purpose, and consent must be informed and aligned with the public interest [36]. The necessary infrastructure can be another challenge, since implementing and maintaining large language models in production requires high computational power, requiring a robust framework to process large volumes of data.

As threats to validity, although our study demonstrates the promising capabilities of LLMs in health information retrieval and supporting telemedicine systems, it is not without limitations. In order to reinforce the validity of the results obtained with the expert panel, it would be ideal to calculate inter-rater agreement metrics. At the current stage of the research, however, the data is insufficient to apply this type of analysis. The panel is already being expanded by including physicians who report the results and by generating new question-and-answer pairs in order to reach a significant sample size for little-explored but valuable statistical methods, such as the inter-rater agreement coefficient.

Finally, in order to allow transparency and replicability of the results, additional resources are described in Appendix A.

6. Conclusions

In this article, the STT-Chat was presented, an LLM-based chatbot specialized in the Telemedicine and Telehealth System (STT). Validation occurred on two fronts: (i) automatic evaluation with G-Eval analyses and (ii) qualitative evaluation by a panel of experts from the STT team. Our findings suggest that incorporating Large Language Models (LLMs) into healthcare systems can support and facilitate information retrieval. The STT-Chat prototype has the potential to be integrated into the system, provided the improvements discussed in this article are implemented. It is hoped that this study will contribute to research in artificial intelligence applied to complex healthcare systems, such as STT, and that the adoption of such chatbots will improve information retrieval and support in healthcare systems.

In future work, updates in the STT technical manuals will be implemented, with more specific instructions, including step-by-step instructions on how to use the system. With this, new tuples of questions and answers will be developed for the dataset, resulting in more accurate and detailed answers. Integrating an RAG pipeline will be a priority in the next steps, enabling scalable and verifiable information recovery within the STT ecosystem. Furthermore, adjustments to the model integration process in graphical interfaces, combined with advanced decoding settings, can help reduce context loss and improve response accuracy. Such advances can consolidate the use of LLMs as a strategic tool in telemedicine, expanding their applicability and impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; methodology, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; software, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; validation, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; formal analysis, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; investigation, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; data curation, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; writing—original draft, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; writing—review and editing, B.D.P., D.G.C., R.I., A.v.W., A.S.R.P. and D.D.J.d.M.; visualization, B.D.P., D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; supervision, D.G.C. and D.D.J.d.M.; project administration, R.I., A.v.W. and A.S.R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. We also would like to thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and the Telemedicine Laboratory (LabTelemed) of Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) for supporting in part this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Reproducibility and Data Availability

This work is fully reproducible. All datasets, code, and scripts used in the experiments are openly available:

- Dataset: The complete set of question–answer tuples used to train the STT-Chat model is publicly available on Hugging Face at https://huggingface.co/datasets/Brunapupo/teledermato-data, accessed on 1 October 2025.

- Source Code: Python scripts for fine-tuning the Llama 3 model and compiling the interface are available in the GitHub repository: https://github.com/Brunapupo/stt-chat-llm, accessed on 1 October 2025.

- Video Demonstration: A recorded demonstration of the model in operation is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b452FFSvaow&t=1271s, accessed on 1 October 2025.

- Reproduction Environment: Experiments were conducted using GPUs (NVIDIA A100 and RTX 3090, total 48 GB VRAM). The provided scripts can be executed in any compatible PyTorch environment with Hugging Face Transformers.

References

- Amin, S.U.; Hossain, M.S. Edge Intelligence and Internet of Things in Healthcare: A Survey. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib, I.; Shamayleh, A.; Ndiaye, M. Healthcare and the Internet of Medical Things: Applications, Trends, Key Challenges, and Proposed Resolutions. Informatics 2024, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Huang, D.; Wu, D.; He, H.; Wei, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wang, R.; Peng, L. A Survey of Internet of Medical Things: Technology, Application and Future Directions. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.J.; Bhat, C.R. Telemedicine Adoption before, during, and after COVID-19: The Role of Socioeconomic and Built Environment Variables. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 192, 104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenoghena, C.O.; Ohize, H.O.; Adejo, A.O.; Onumanyi, A.J.; Ohihoin, E.E.; Balarabe, A.I.; Okoh, S.A.; Kolo, E.; Alenoghena, B. Telemedicine: A Survey of Telecommunication Technologies, Developments, and Challenges. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2023, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, R.L. Telemedicine and Health Care. Telemed. J. E-Health 2002, 8, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltzfus, M.; Kaur, A.; Chawla, A.; Gupta, V.; Anamika, F.; Jain, R. The role of telemedicine in healthcare: An overview and update. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Takahashi, D.; Hu, F. Telemedicine Usage and Potentials. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Hong Kong, China, 11–15 March 2007; pp. 2736–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakor, M.Y.; Khaleel, M.I. Recent Advances in Big Medical Image Data Analysis Through Deep Learning and Cloud Computing. Electronics 2024, 13, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallauer, J.; von Wangenheim, A.; Andrade, R.; Macedo, D.D.J. A Telemedicine Network Using Secure Techniques and Intelligent User Access Control. In Proceedings of the 21st IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Jyväskylä, Finland, 17–19 June 2008; pp. 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friha, O.; Ferrag, M.A.; Kantarci, B.; Cakmak, B.; Ozgun, A.; Ghoualmi-Zine, N. LLM-based edge intelligence: A comprehensive survey on architectures, applications, security and trustworthiness. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 5799–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviainen, J.; Rantala, J. Chatbot breakthrough in the 2020s? An ethical reflection on the trend of automated consultations in health care. Med. Health Care Philos. 2022, 25, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazi, Z.A.; Peng, W. Large Language Models in Healthcare and Medical Domain: A Review. Informatics 2024, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, B.N.; Leitão, A.; Nascimento, G.; Campos-Fernandes, A.; Cercas, F. Can ChatGPT Support Clinical Coding Using the ICD-10-CM/PCS? Informatics 2024, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wong, C.; Zhang, S.; Usuyama, N.; Liu, H.; Yang, J.; Naumann, T.; Poon, H.; Gao, J. LLaVA–Med: Training a Large Language–and–Vision Assistant for Biomedicine in One Day. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.00890. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Inácio, A.; Andrade, R.; von Wangenheim, A.; de Macedo, D.D.J. Designing an information retrieval system for the STT/SC. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom), Natal, Brazil, 15–18 October 2014; pp. 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.; Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S.; Gohil, K. Can We Trust a Chatbot like a Physician? A Qualitative Study on Understanding the Emergence of Trust toward Diagnostic Chatbots. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 165, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Seth, I.; Hunter-Smith, D.J.; Rozen, W.M.; Seifman, M.A. Investigating the Impact of Innovative AI Chatbot on Post-Pandemic Medical Education and Clinical Assistance: A Comprehensive Analysis. ANZ J. Surg. 2024, 94, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niaz, M.; Nwagwu, U. Managing healthcare product demand effectively in the post-COVID-19 environment: Navigating demand variability and forecasting complexities. Am. J. Econ. Manag. Bus. (AJEMB) 2023, 2, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Y. Sharing service in healthcare systems: A recent survey. Omega 2024, 129, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.G.; Peixoto, J.P.J. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of smart-city initiatives to face new outbreaks. IET Smart Cities 2020, 2, 64–73. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342044985_COVID-19_Pandemic_A_Review_of_Smart_Cities_Initiatives_to_Face_New_Outbreaks (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pap, I.A.; Oniga, S. eHealth Assistant AI Chatbot Using a Large Language Model to Provide Personalized Answers through Secure Decentralized Communication. Sensors 2024, 24, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, D.; Za’in, C.; Chan, H.M.; Haryanto, A.; Agustiono, W.; Yu, K.; Hamilton, K.; Kroon, J.; Xiang, W. A blueprint for large language model-augmented telehealth for HIV mitigation in Indonesia: A scoping review of a novel therapeutic modality. Health Informatics J. 2024, 31, 14604582251315595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, E.; Venigalla, A.; Yasunaga, M.; Hall, D.; Xiong, B.; Lee, T.; Daneshjou, R.; Frankle, J.; Liang, P.; Carbin, M.; et al. BioMedLM: A 2.7B Parameter Language Model Trained on Biomedical Text. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.18421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Amin, M.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A Pre-trained Biomedical Language Representation Model for Biomedical Text Mining. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, M. The Inside Story of Babylon Health. Prospect Magazine. 2020. Available online: https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/ideas/technology/40385/the-inside-story-of-babylon-health (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Puel, A.; Meurer, M.I.; von Wangenheim, A.; Macedo, D.D.J. BUCOMAX: Collaborative Multimedia Platform for Real-Time Support of Diagnosis and Teaching Based on Bucomaxillofacial Diagnostic Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), New York, NY, USA, 27–29 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta AI Team. LLaMA 3: Advancing the State of Large Language Models with Efficiency and Scalability. 2024. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/meta-llama-3/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ollama Team. Ollama: A Platform to Run and Customize Large Language Models Locally with Privacy and Performance. 2024. Available online: https://ollama.com/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Open WebUI Team. Open WebUI is an Extensible, Self-Hosted AI Interface that Adapts to Your Workflow, All While Operating Entirely Offline. 2024. Available online: https://openwebui.com/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Shi, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Lu, W. Know where to go: Make LLM a relevant, responsible, and trustworthy searcher. Decis. Support Syst. 2025, 188, 114354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Lei n° 13.709, de 14 de Agosto de 2018—Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais (LGPD). Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. 2018. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2018/lei/l13709.htm (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Afaq, S.; Rao, S. Significance of Epochs on Training a Neural Network. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 485–490. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Significance-Of-Epochs-On-Training-A-Neural-Network-Afaq-Rao/c010c03972a0b37cd41cab710877595b3576512f (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Iter, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, R.; Zhu, C. G-Eval: NLG Evaluation Using GPT-4 with Better Human Alignment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.16634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minssen, T.; Vayena, E.; Cohen, I.G. The challenges for regulating medical use of ChatGPT and other large language models. JAMA 2023, 330, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).