Abstract

During the laser cladding process, the distribution of the temperature field directly influences the morphology, microstructure, and residual stress state of the cladding layer. However, the process involves transient characteristics of rapid heating and cooling, making it challenging to study temperature field variations directly through experimental methods. Therefore, numerical simulation has become a crucial tool for gaining a deeper understanding of the laser cladding mechanism, providing theoretical basis and guidance for optimizing process parameters. This study systematically integrates COMSOL Multiphysics coupling simulation with Jmatpro material thermal property data to perform simulations of temperature field evolution, melt pool flow behavior, and Marangoni effects during laser cladding of nickel-based alloy (IN718) onto an EA4T steel substrate. It highlights the influence patterns of different process parameters (e.g., laser power, scanning speed) on the temperature gradient and flow characteristics of the molten pool, providing an in-depth theoretical basis for understanding the formation mechanism of the molten pool and microstructure control.

1. Introduction

Laser technology demonstrates significant application value in industrial manufacturing due to its unique processing characteristics [1,2]. Its high-precision energy control capability enables selective processing of minute areas, making it particularly suitable for scenarios such as precision welding, surface modification, and additive manufacturing [3,4]. The technology’s excellent automation compatibility facilitates seamless integration into digital manufacturing platforms, achieving precise process control and enhanced repeatability [5]. Simultaneously, the concentrated heat input and extremely short duration of laser processing effectively control the heat-affected zone, minimizing workpiece deformation, residual stress, and microstructural damage. This provides critical process advantages for enhancing processing quality and optimizing product performance [6].

Song et al. [7] established and validated a thermal conduction finite element model for laser cladding using ABAQUS (https://www.3ds.com/zh-hans/products/simulia/abaqus, accessed on 28 October 2025). The model analyzed the temperature distribution and thermal cycles in single-pass cladding, revealing that peak temperature and melt pool size are positively correlated with laser power but inversely correlated with cladding rate. Liu et al. [8] simulated the cladding of FeCoCrNi alloy onto 316 stainless steels using ANSYS Workbench (https://www.ansys.com/products/ansys-workbench, accessed on 28 October 2025). The results demonstrated that while increasing laser power elevated melt pool temperature and expanded the HAZ, excessively high power induced cracks, whereas moderate power ensured sound metallurgical bonding. Zhang et al. [9] revealed through simulation that for laser cladding of T-shaped components, clamping methods influence both the magnitude and distribution of residual stress and deformation, while cladding paths and speeds mainly control their peak values. Han et al. [10] established a finite element model in Ansys-Workbench to study the coating morphology-temperature field relationship for Ni60 alloy clad on 316L steel. By investigating laser power, spindle speed, and spot radius, they identified that a parameter set of 1400 W, 60 r/min, and a 1.5 mm radius produces a 0.22 mm remelted zone and optimal metallurgical bonding. Zhang et al. [11] demonstrated through simulation that during multi-layer cladding of 316L steel, scanning speed outweighs laser power in controlling the peak temperature. Therefore, residual stresses are effectively reduced by selecting a lower laser power or a higher scanning speed.

Hunt et al. [12] analyzed the growth of columnar and equiaxed grains during directional solidification, proposing a model to account for both single-phase and eutectic equiaxed growth. A simplified expression predicting the occurrence of fully equiaxed structures was derived, and the effect of equiaxed growth on the eutectic spacing was discussed. Ye et al. [13] established a multiphysics finite element model for multi-layer, multi-pass laser cladding of 0Cr16Ni5Mo1 stainless steel. The flow and heat transfer behavior and characteristics of the molten pool under different laser power and overlap rate conditions were analyzed. The variation patterns of the temperature field, flow field, molten pool geometry, and dilution rate, along with their influencing factors, wessre investigated. Xiong et al. [14] developed a phase-field model to analyze changes in solid–liquid interface undercooling and nucleation density, with experimental validation confirming the simulation’s accuracy. Azizi et al. [15] proposed using phase-field simulation at the dilution limit and non-dilution limit methods to investigate the effect of build orientation on microstructural evolution in LPBF-AlSi alloy systems. At relevant solidification rates, no significant differences were observed in microstructures formed with or without solute trapping effects. Hadadzadeh et al. [16] investigated the effect of build orientation on the equiaxed grain transformation in DMLS-processed AlSi10Mg alloy (EOS GmbH, Krailling, Germany). Two identical cladding layers were printed vertically and horizontally under identical process parameters. The vertical sample exhibited a different ratio of columnar to equiaxed grains compared to the horizontal sample, with corresponding changes in precipitates.

This study conducted a detailed investigation of the temperature field generated during laser cladding, focusing on the formation process of the molten pool and the internal flow behavior induced by the Marangoni effect. The molten pool under different process parameters was simulated using COMSOL software (https://www.comsol.com/, accessed on 28 October 2025), and the effects of each parameter on the maximum temperature in the molten pool and the trend of temperature change were systematically investigated. These findings contribute to elucidating the mechanism of laser cladding and provide theoretical foundations for subsequent optimization of process parameters.

2. Thermal Properties of Materials

During the laser cladding process, as laser energy is input, the temperatures of the powder and substrate rapidly rise to their melting points within a short time. The substrate and powder transition from their original solid phase to a liquid phase, causing changes in material properties such as density and specific heat capacity. To achieve simulations that more closely approximate reality, it is necessary to obtain the relationship between the thermal properties of the powder material and substrate material and temperature.

IN718 refers to Inconel 718, a nickel-based superalloy commonly used in high-temperature structural applications. IN 718 powder is widely used in additive manufacturing, particularly suited for producing complex-shaped aerospace engine components via laser powder bed fusion technology. This is due to its excellent weldability and superior strength at moderate temperatures. The alloy’s higher chromium (Cr) and molybdenum (Mo) content provides superior corrosion resistance compared to other nickel-based alloys, such as IN 625. During laser cladding, IN 718 powder achieves strong metallurgical bonding with various substrates, delivering low dilution rates and high cladding quality. Additionally, the IN718 alloy exhibits high fatigue strength and outstanding resistance to stress corrosion cracking. These properties ensure exceptional long-term service stability in extremely demanding environments. Simultaneously, IN 718 powder exhibits favorable machinability, facilitating subsequent precision machining after laser cladding. This is particularly advantageous for achieving final dimensional and topographical requirements on complex-shaped components [17,18]. The chemical composition of IN 718 is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mass fraction of chemical composition for IN 718 (wt%).

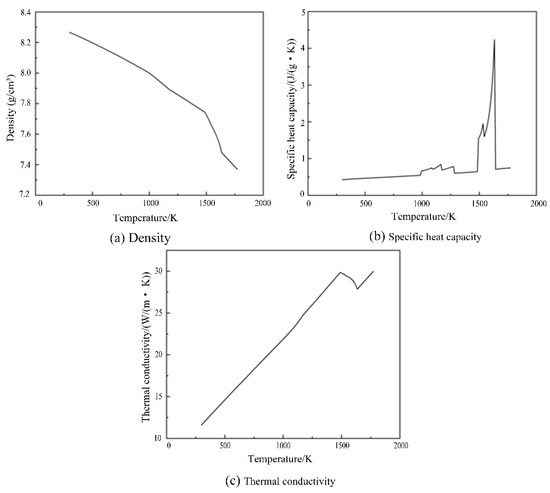

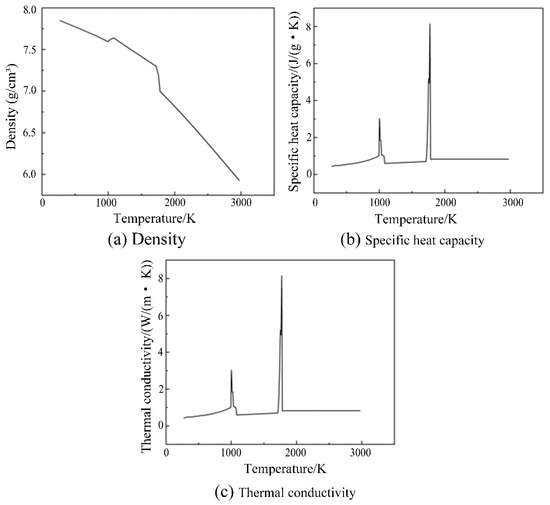

For this experiment, the built-in parameters of the professional software Jmatpro (https://www.sentesoftware.co.uk/, accessed on 28 October 2025) were utilized to obtain the temperature-dependent thermal properties of IN718 [19,20,21], as shown in Figure 1. The chemical composition of EA4T steel was employed in JMatPro to calculate its thermal properties. The resultant data were subsequently utilized as the foundational input for temperature field modeling and associated simulations. The resulting thermal properties are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Temperature-dependent thermophysical properties of IN718 obtained from JmatPro.

Figure 2.

Temperature-dependent thermophysical properties of EA4T steel obtained from JmatPro.

3. Establishment of Laser Cladding Temperature Models

3.1. Basic Assumptions of the Model

The laser cladding process is a complex phenomenon involving multiple physical phenomena. To reduce computational costs, certain experimental conditions are idealized, leading to the following reasonable assumptions for the laser cladding process [22,23,24]:

- (1)

- When the metal in the molten pool becomes liquid, its flow state is laminar and behaves as an incompressible Newtonian fluid.

- (2)

- The effects of powder delivery gas and shielding gas on the experimental environment are disregarded.

- (3)

- The initial ambient temperature is set to 273.15 K.

- (4)

- Both the cladding layer and substrate are isotropic materials.

3.2. Establishment of Heat Source Models

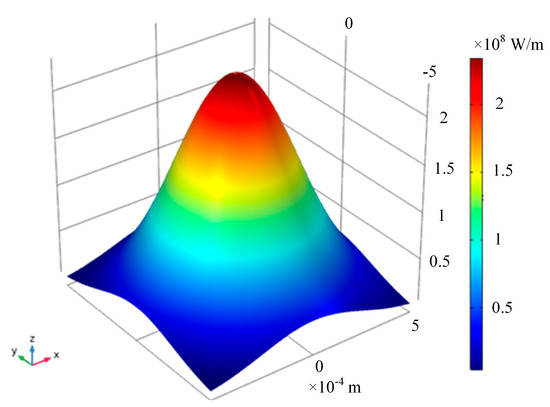

In laser cladding temperature field simulations, the accuracy of the heat source model directly impacts the precision of the simulated temperature distribution. An accurate heat source model enables more precise simulation of temperature variations during actual cladding processes. Common heat source models for laser cladding temperature field simulations include Gaussian distribution and double ellipsoid models. This paper adopts the Gaussian distribution heat source mode. The Gaussian model is typically accurate for shallow melt pools or surface-dominant heating but may not capture volumetric absorption effects. In the Gaussian heat source model, laser energy exhibits a Gaussian distribution on the workpiece surface. Heat density peaks at the center and gradually diminishes outward, making it suitable for simulating surface heat sources, particularly when heat input is concentrated at the surface [23,25]. Its expression is

Here, P represents the laser power, rb denotes the laser radius, and r indicates the distance to the laser center.

The above Gaussian light source expression describes the distribution of a Gaussian light source on a plane. However, in actual simulations, the light source moves over time, causing changes in its position. Therefore, the light source must be processed by introducing a time parameter into the Gaussian light source model. Concurrently, considering the laser energy absorption efficiency, the heat source model undergoes deformation processing. This yields the expression for a moving Gaussian heat source [20]:

Here, η denotes the laser absorption efficiency, while fx(t) and fy(t) represent the time-varying position coordinates of the laser center. These can be expressed as

Here, v represents the scanning speed in laser cladding. The heat source model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Gaussian light source model.

3.3. Marangoni Effect

During laser cladding, the Marangoni effect critically influences process outcomes by governing molten pool flow, which in turn affects clad morphology and cooling rates. This thermo-fluid phenomenon is driven by surface tension gradients, primarily induced by the steep temperature difference between the central laser spot and the cooler pool periphery. Since surface tension typically decreases with temperature, liquid metal is drawn from the high-temperature, low-tension center toward the low-temperature, high-tension edges, resulting in Marangoni convection. Accurate simulation of this effect is thus crucial for understanding and optimizing the process.

To accurately simulate the influence of the Marangoni effect on melt pool flow during laser cladding, a multiphysics coupled simulation integrating the heat conduction equation, fluid dynamics equations, and surface tension gradients is required. First, establish the temperature distribution under laser input [20,26]:

Here, ρ denotes the material density, cp represents the specific heat capacity of the material, T indicates the material temperature, k signifies the thermal conductivity, and Q denotes the laser-input heat source.

The fluid flow equations in the molten pool are typically described by the Navier–Stokes equations, which include the mass conservation equation and the momentum conservation equation. The mass conservation equation is

where is the fluid velocity within the molten pool.

The equation of conservation of momentum is [20,26]

Here, p represents pressure, μ denotes the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, and is the volumetric force.

The relationship between the Marangoni effect and surface tension is as follows:

Here, γ (T) denotes surface tension, and represents the surface gradient operator. The introduction of surface tension incorporates convection into fluid dynamics.

3.4. Boundary Conditions and Mesh Partitioning

Regarding temperature fields in the simulation of laser cladding, establishing correct and reasonable boundary conditions is crucial. These conditions directly determine the accuracy of simulation results and their fidelity to actual physical phenomena. Depending on the specific environment, the boundary conditions vary. For the upper surface of the material, the boundary conditions are [26,27,28]:

The boundary equations for other surfaces are

Here, h represents the convective heat transfer coefficient between the substrate and the external environment surface, Te denotes the ambient temperature, ε is the surface emissivity, and σ is the Boltzmann constant.

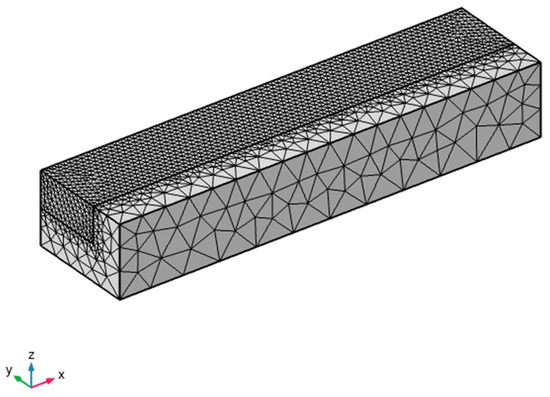

To reduce computational load, a symmetric geometric model was employed during calculations. Based on computational importance, the model was divided into two regions: the molten pool section and the region distant from the molten pool. The mesh density was allocated according to the required computational accuracy for each region. All sections employ free tetrahedral meshing. For the melt pool region, the maximum element size is 0.1 mm, with a minimum of 0.005 mm. For the substrate far from the melt pool, the maximum element size is 0.6 mm, and the minimum is 0.108 mm [26,27,28]. The meshing results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Simulation model delineation results.

4. Temperature Field Simulation Results

4.1. Single-Channel Single-Layer Temperature Field Simulation Results

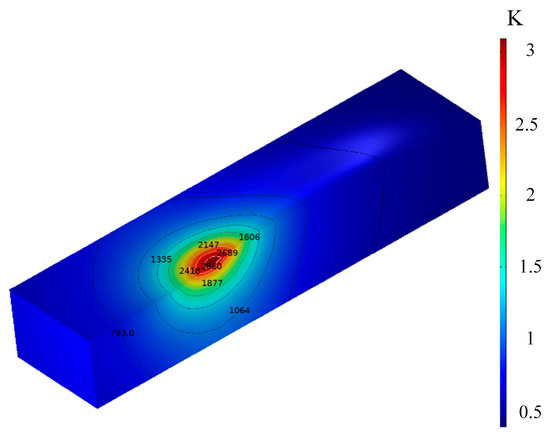

Based on the optimal process parameters obtained above—namely, laser power of 420 W, scanning speed of 7 mm/s, and powder feed rate of 1.1 r/min—these values were substituted into the macro-scale temperature field model for simulation and calculation. The resulting temperature distribution is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Temperature field at optimal laser parameters.

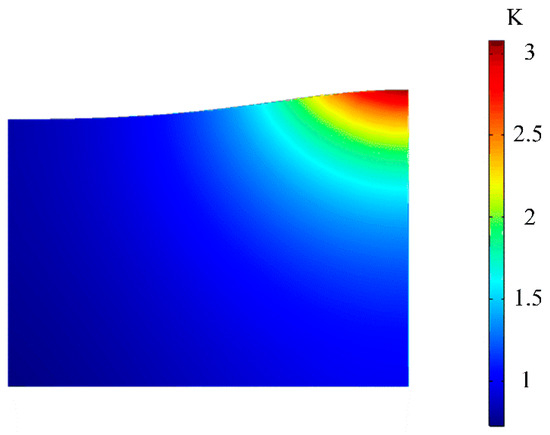

Under the aforementioned process parameters, the simulated temperature field results are shown in Figure 5. It can be observed that the maximum temperature in the field reaches 3100 K, exceeding both the melting temperature of IN718 and the melting point of EA4T steel, with the red region indicating the molten pool. The temperature distribution across the molten pool cross-section is depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Cross-section temperature distribution.

The temperature gradient holds significant physical importance in laser cladding. The temperature gradient within the molten pool refers to the direction and rate of temperature change within the pool. Its expression is

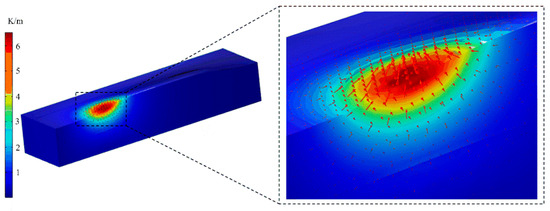

A higher temperature gradient increases both the solidification rate and cooling rate, which promotes rapid solidification and refines grain structure, thereby enhancing coating properties. Conversely, a lower temperature gradient reduces the cooling rate, facilitating more complete grain growth and leading to coarse-grained microstructures that degrade coating quality. The temperature gradients corresponding to the simulation results are shown in Figure 7. The arrows in Figure 7 indicate the direction of the temperature gradient.

Figure 7.

Molten pool temperature gradient results.

As shown in Figure 7, under the direct influence of the laser input, the center of the molten pool is continuously heated. Consequently, the temperature gradient at the molten pool center exhibits significant variation, reaching a maximum value of 6.52 × 106 K/m. In contrast, the surrounding areas of the molten pool experience smaller temperature changes due to their greater distance from the laser, resulting in a relatively lower temperature gradient compared to the pool center.

During laser cladding, extremely high temperature gradients cause localized areas of the material to undergo uneven thermal expansion and contraction. The molten pool center rapidly heats up and expands under laser exposure, while the surrounding cooler regions constrain this expansion, generating thermal stresses within the material. Subsequently, during the rapid cooling and solidification phase, thermal stresses induced by temperature gradients that are not fully released through plastic deformation become retained as residual stresses. Therefore, larger temperature gradients result in more pronounced thermal stresses, ultimately leading to higher residual stresses [27,29].

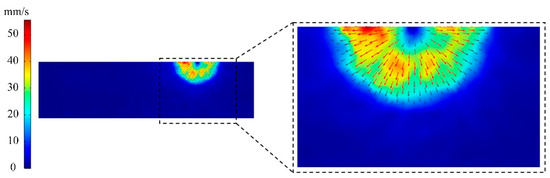

The Marangoni effect simulation and results are depicted in Figure 8. The arrows in Figure 8 indicate the direction of the flow field velocity. Observation reveals that during laser cladding, the maximum velocity induced by the Marangoni effect reaches 55.6 mm/s, while the minimum velocity is zero. The maximum velocity occurs along the laser scanning path, whereas the minimum velocity is found at the melt pool center. This phenomenon stems from the critical relationship between the Marangoni effect and surface tension: the laser center exhibits reduced surface tension due to laser energy input, while the melt pool edges maintain higher surface tension, leading to increased velocity.

Figure 8.

Simulation diagram of the Marangoni effect.

Additionally, the velocity at the rear end of the melt pool is higher than that at the front end. At the leading edge of the melt pool, proximity to the laser center results in high temperatures and concentrated heating. Despite the elevated temperature, surface tension changes gradually. The rear of the melt pool experiences lower temperatures compared to the front. As the distance from the laser increases, the temperature decreases progressively, causing the melt pool to cool and begin solidifying. Consequently, surface tension transitions from lower to higher values, creating a surface tension gradient. The significant temperature difference enhances the manifestation of the Marangoni effect. Overall, the simulated peak temperature aligns well with the results of Mo et al., who reported similar temperature ranges under comparable laser power conditions [29]. Meanwhile, the Marangoni velocity falls within the range of melt pool flow velocities reported in multiphysics simulations by Wang et al. and Liu et al., which is consistent with the fluid dynamics described in studies of Marangoni-driven flow during laser processing [20,30].

4.2. Effect of Laser Power on Temperature Field

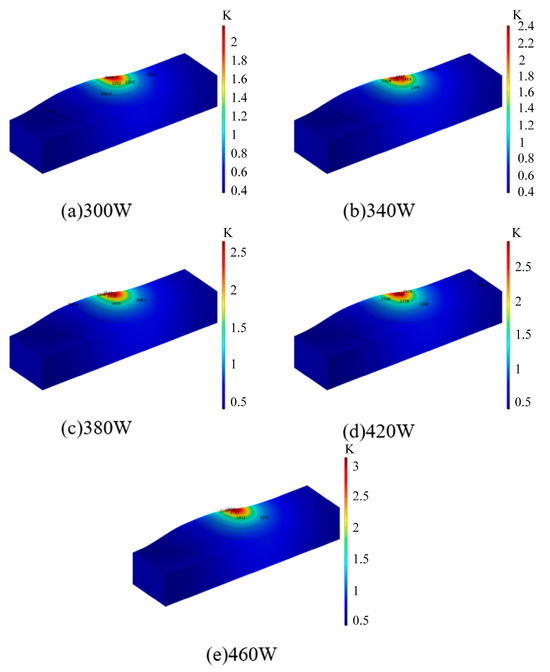

When investigating the effect of laser power on temperature field variations, the laser power was varied while keeping all other parameters constant to control the variables. Laser powers of 300 W, 340 W, 380 W, 420 W, and 460 W were set, with a scanning speed of 7 mm/s. The simulation results are shown in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9.

Effect of laser power on temperature field.

As shown in Figure 9, as the laser power increases from 300 W to 460 W, the maximum temperature of the molten pool also gradually rises from 2.08 × 103 K to 2.98 × 103 K. This occurs because the increased laser power delivers greater energy, causing more energy to enter the molten pool and thereby raising its temperature. Concurrently, this also indicates the formation of a deeper molten pool.

The increase in laser power leads to a deeper melt pool due to greater energy penetration, which enhances metallurgical bonding but also increases the risk of excessive substrate dilution. The associated higher temperature gradients promote finer grain structures through increased cooling rates, potentially improving coating hardness and strength. However, excessively high power may also lead to issues such as cracking, elemental burning loss, or a shift from columnar to equiaxed grain growth, which could affect mechanical anisotropy. Therefore, optimizing laser power is critical to achieving a balance between sound microstructure and desirable coating properties. Future work will incorporate experimental validation to quantitatively correlate these simulated thermal conditions with microstructural characteristics [31,32].

4.3. Effect of Scanning Speed on Temperature Field

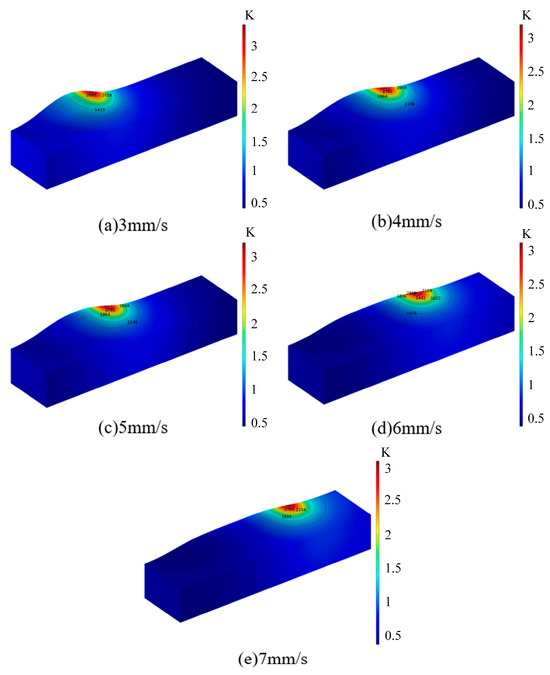

The laser power was set to 300 W, with scanning speeds of 3 mm/s, 4 mm/s, 5 mm/s, 6 mm/s, and 7 mm/s simulated. The resulting temperature field simulation is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Effect of scanning speed on temperature field.

As the scanning speed increases, the maximum temperature gradually decreases. The effect of scanning speed on the maximum temperature is less pronounced compared to that of laser power, further validating that laser power has the most significant impact on experimental results in this study. Simultaneously, observation of the model reveals that the height of the cladding layer progressively diminishes with increasing scanning speed. This occurs because the scanning speed was incorporated as a parameter into the cladding layer dynamic model during model creation, thereby enhancing the realism of the simulation.

Increasing the scanning speed reduces the heat input per unit length, which leads to a higher cooling rate and a steeper thermal gradient. This promotes rapid solidification, generally resulting in a finer grain structure that can enhance the coating’s hardness and strength. However, if the scanning speed is too high, the excessively high cooling rate may also increase the risk of cracking due to heightened thermal stresses. Conversely, a lower scanning speed provides a lower cooling rate, allowing grains to grow more fully, which may lead to coarser microstructures and potential deterioration in coating properties. Therefore, optimizing the scanning speed is crucial for achieving a balance between a refined microstructure and acceptable residual stress levels to ensure high coating quality [33,34].

5. Conclusions

This study employs coupled simulations using COMSOL Multiphysics to analyze the temperature field evolution, melt pool flow behavior, and Marangoni effect during the laser cladding of nickel-based alloy (IN718) onto an EA4T steel substrate. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The maximum temperature of the molten pool gradually increased from 2080 °C at 300 W to 2980 °C at 460 W, with the melt pool size increasing accordingly. As the scanning speed increased, the maximum melt pool temperature decreased from 3190 °C at 3 mm/s to 2980 °C at 7 mm/s, accompanied by a reduction in melt pool size.

- (2)

- The simulation successfully captured the metal flow within the melt pool caused by the Marangoni effect. This provides valuable insights into melt pool formation and flow dynamics, laying the groundwork for subsequent microstructure investigations. The simulated temperature field and flow field values fall within the range of results from previous similar studies, demonstrating the consistency of the hydrodynamic effects driven by the Marangoni effect during laser processing.

- (3)

- The quantified relationships between process parameters (laser power, scanning speed) and the resulting thermal characteristics (temperature, gradient, Marangoni flow) provide a direct theoretical basis for selecting parameters in industrial applications to control microstructure, minimize defects like cracking, and ultimately improve coating quality and process reliability.

The current model incorporates several necessary simplifications to ensure computational feasibility, including the assumption of laminar and incompressible Newtonian fluid flow within the molten pool, which may not fully capture potential turbulent behaviors under high scanning speeds. Additionally, the latent heat effects during solid–liquid phase transformation are neglected, which could influence the accuracy of the predicted temperature history and solidification behavior. The Marangoni effect is modeled using a temperature-dependent surface tension gradient without accounting for possible solute-induced variations, which represents a simplification of the actual thermo-fluid dynamics. Future work will aim to incorporate more comprehensive multiphase and turbulence models to enhance the predictive capability of the simulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G. and T.Y.; data curation, S.H.; formal analysis, L.S. and C.Z.; funding acquisition, T.Y.; resources, Y.G.; software, S.H.; validation, L.S. and C.Z.; writing—original draft, S.H. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research on Deformation, Wear, and Impact Resistance of Extra-Long Working Face Chains: Technical Services (No. 2024020900110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Longfeng Sun was employed by the company Jiangnan Shipyard (Group) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, J.; Wu, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J. Multi-objective process optimization and strengthening mechanism analysis of U-groove-assisted laser cladding Ni-based composite coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 716, 164676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J. Material removal mechanism and surface morphology of ceramic reinforced nickel-based composite coatings by ultrasonic grinding. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51 Pt A, 48295–48317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Mu, Z.; Luo, M.; Huang, A.; Pang, S. Laser Spot Micro-Welding of Ultra-Thin Steel Sheet. Micromachines 2021, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodo, G.; Sorrentino, L.; Turchetta, S.; Moffa, G. Laser treatment design for CFRP bonding: An innovative approach to reduce process time. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2025, 142, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, D.A.; Risbridger, D.; Mills, B.; Rakhmatulin, I.; Kong, X.; Erden, M.; Esser, M.J.D.; Carter, R.M.; Chantler, M.J. Three Approaches to the Automation of Laser System Alignment and Their Resource Implications: A Case Study. Electr. Eng. Syst. Sci. 2024, 9, 11090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, S.; Li, G.; Lu, F. Study on the formation mechanism of HAZ microcracks in FB2 heat-resistant steel by laser cladding. Mater. Charact. 2025, 221, 114750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, J. Numerical Simulation Analysis of Temperature Field in Laser Cladding under Low Heat Input. Weld. Technol. 2025, 54, 63–68+145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Luo, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, Z. Simulation of Temperature and Stress Fields in Laser Cladding Process of FeCoCrNi Coatings. Heat Treat. Met. 2025, 50, 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liang, S.; Luo, R.; Wang, X. Numerical Simulation of Laser Cladding on T-Shaped Components. J. Civ. Aviat. Univ. China 2025, 43, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Dou, W. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Verification of Ni60 Alloy Cladding Layer on 316L Stainless Steel Surface via Laser Cladding. Electroplat. Finish. 2025, 47, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Tang, Q.; Pan, W.; Ma, Z.; Hu, T. Numerical Simulation Study on Temperature and Stress Fields of Single-Pass Multi-Layer Laser Cladding on Axial Surfaces of 316L Stainless Steel. Manuf. Technol. Mach. Tools 2025, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.D. Steady state columnar and equiaxed growth of dendrites and eutectic. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1984, 65, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.-L.; Sun, A.-D.; Zhai, W.-Z.; Wang, G.-L.; Yan, C.-P. Finite element simulation analysis of flow heat transfer behavior and molten pool characteristics during 0Cr16Ni5Mo1 laser cladding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 2186–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingda, X.; Guoli, Z.; Gaoyang, M.; Chunming, W.; Ping, J. A phase-field simulation of columnar-to-equiaxed transition in the entire laser welding molten pool. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 858, 157669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Ofori-Opoku, N.; Greenwood, M.; Provatas, N.; Mohammadi, M. Characterizing the microstructural effect of build direction during solidification of laser-powder bed fusion of Al-Si alloys in the dilute limit: A phase-field study. Acta Mater. 2021, 214, 116983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadadzadeh, A.; Amirkhiz, B.S.; Li, J.; Mohammadi, M. Columnar to equiaxed transition during direct metal laser sintering of AlSi10Mg alloy: Effect of building direction. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 23, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, R. Precipitation around welds in the nickel-base superalloy, Inconel 718. Acta Metall. 1985, 33, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Funakoshi, Y.; Kawashima, H.; Matsunaga, H. Inferior fatigue resistance of additively-manufactured Ni-based superalloy 718 and its dominating factor. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 176, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, W.; Liang, Q. Effect of solution treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of laser-cladded Stellite 6 coatings on 2507 duplex stainless steel. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Lin, J.; Peng, L.; Wang, X. Numerical simulation of heat transfer and flow behavior of molten pool under figure-8 oscillating laser cladding. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 220 Pt A, 110279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, F.; Liu, M. Study on the finite element simulation for the cutting of Ni60 laser cladding layer based on heterogeneous modeling. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 190, 113239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Y. Multifield modeling of coating profile and substrate stress distribution in laser cladding of hot stamping dies. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 190, 113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Wu, D.; Zheng, C.; Huang, K.; Yi, X. Numerical simulation and experimental research on the effects of substrate preheated on the cracks, microstructure, and properties of laser cladding WC-Ni60AA coatings. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Feng, M.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.; Lian, G. Molten pool flow and microstructure evolution in laser cladding of SiC/Mo-based coating. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 252, 127482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Shi, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Y. Laser cladding of diamond reinforced composite coatings on the rotary tiller blade with complex curved surface: Cladding paths and residual stress. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 516, 132734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Cheng, Z. Simulation and experimental investigations on the effect of Marangoni convection on thermal field during laser cladding process. Optik 2020, 203, 164044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Xing, Y.; Yin, S. Numerical simulation of temperature field and stress field of laser cladding Stellite6. Next Mater. 2025, 7, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Hu, D.; Lv, H.; Yang, Q. Experimental and numerical simulation studies of the flow characteristics and temperature field of Fe-based powders in extreme high-speed laser cladding. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 170, 110317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, B.; Li, T.; Xiao, C.; Shi, F.; Liu, W. Numerical simulation and experimental study of temperature and stress fields during laser cladding of multi-layer Ni60A alloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192 Pt B, 113536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, G.; Ren, K.; Di, Y.; Wang, L.; Rong, Y.; Wang, H. Marangoni flow patterns of molten pools in multi-pass laser cladding with added nano-CeO2. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59 Pt A, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Ji, S.; Shi, T.; Shi, S.; Fu, G. Statistical and experimental study of effects of process parameters on Ti-6Al-4V coaxial wire-feed laser cladding. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2026, 39, 100041. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Wu, C.; Cui, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C. Study on microstructure, mechanical properties, wear and cavitation erosion resistance of FeCrNiTi0.3Al0.3 high entropy alloy coatings by laser cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Ye, C. The formation characteristics analysis of cladding layer in the laser additive manufacturing on inclined substrate under the different scanning speed conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2026, 219, 110242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, J. Influence of scanning speed on the microstructure, nanoindentation characteristics and tribological behavior of novel maraging steel coatings by laser cladding. Mater. Charact. 2023, 205, 113335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).