Abstract

Adequate ridge width and thermal control are critical for predictable implant site preparation. This in vitro study compared conventional osteotomy (CO), osseodensification (OD), and OsseoShaper (OS) protocols in standardized polyurethane foam blocks simulating narrow D2 ridges. A total of 18 osteotomies (n = 6 per group) were prepared under protocol-specific irrigation. Ridge width was measured at 3, 6, and 9 mm apical to the crest before and after osteotomy using a digital caliper, and expansion (ΔW) was calculated. Intraoperative thermal changes (ΔT) were recorded in real time with an infrared thermal camera. OD achieved consistent expansion at all depths (p < 0.05), while OS produced significant widening at the 3 and 6 mm levels; CO yielded only a minor but significant gain at the 3 mm level. At the intergroup level, OS showed significantly greater crestal expansion than CO at 3 mm (p = 0.006). All protocols generated comparable thermal changes (mean ΔT 7.4–8.2 °C), remaining well below the critical 47 °C threshold. Within the limitations of this in vitro model, OD and OS enhanced ridge expansion compared with CO, particularly at the crestal level, where expansion is most critical. All protocols maintained thermally safe profiles, supporting their clinical applicability.

1. Introduction

Successful implant site preparation requires not only an appropriate osteotomy design but also the preservation of native bone and effective control of intraosseous heat generation. These factors are particularly critical in narrow alveolar ridges, where limited crestal width compromises standard implant placement and increases the risk of cortical plate perforation or the need for grafting procedures [1,2,3,4].

Conventional osteotomy protocols that employ a sequence of subtractive drilling steps effectively create the osteotomy site but simultaneously reduce bone density and ridge volume. This loss of native bone is particularly disadvantageous in narrow ridges, where even minor reductions may affect treatment feasibility [5,6,7]. To overcome these limitations, alternative site preparation techniques have been developed. Osseodensification (OD) employs specially designed burs rotating counterclockwise (CCW) to compact bone, thereby preserving ridge integrity and facilitating horizontal expansion [8,9,10,11,12]. Similarly, the OsseoShaper (OS) instrument, as part of the Nobel Biocare N1 concept, utilizes a low-speed, torque-sensitive design that maintains vital bone through controlled shaping rather than aggressive cutting [13,14,15].

Another critical factor during osteotomy is thermal change. Prolonged exposure of bone to temperatures ≥47 °C for at least 1 min can lead to irreversible osteonecrosis, while intraosseous temperature is affected by factors such as drill design, rotational speed, irrigation, and bone density [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Narrow ridges with relatively thick cortical walls may further limit heat dissipation, emphasizing the importance of understanding the protocol-specific thermal behavior under such conditions [17,19,22].

Because human bones exhibit significant variability, rigid polyurethane foam blocks are widely used in experimental research. These materials replicate the density and mechanical properties of natural bone while providing standardization and reproducibility under controlled conditions [22,23,24]. Using narrow ridge artificial bone models, the performance of different osteotomy techniques can be objectively evaluated in terms of ridge expansion and thermal changes.

Although several studies have evaluated the individual performance of OD and the OS system, direct comparative data remain scarce, particularly for narrow alveolar ridges. Most investigations have focused on implant stability parameters, such as insertion torque and resonance frequency analysis [3,5,7,14], whereas relatively few have evaluated ridge expansion and thermal changes as primary outcomes [8,10,11,12,16,25]. To date, only a limited number of studies have directly compared OD and OS under standardized in vitro conditions, and most of them have emphasized implant stability rather than ridge expansion or thermal behavior [9,11,15,16].

The aim of this in vitro study was to compare three osteotomy protocols—Conventional Osteotomy (CO), Osseodensification (OD), and OsseoShaper (OS)—in terms of ridge expansion (ΔW) and intraoperative thermal changes (ΔT) under simulated narrow D2 alveolar ridge conditions. The null hypothesis was that no significant differences would be observed among the three techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This in vitro experimental study evaluated three osteotomy protocols—Conventional Osteotomy (CO), Osseodensification (OD), and OsseoShaper (OS)—in terms of ridge expansion and thermal changes in narrow alveolar ridge models simulating D2 bone density. As the entire study was performed on synthetic bone blocks without the use of human or animal tissues, ethical approval was not required.

2.2. Bone Model

Rigid polyurethane foam blocks (180 × 130 × 40 mm; Sawbones, Pacific Research Laboratories Inc., Vashon Island, WA, USA; Ref. No: 1522-04) were used to simulate type D2 bone. These blocks are validated by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) as standardized materials for evaluating endosseous implants and surgical instruments [24]. Each block was sectioned into narrow ridge segments measuring 3.5 × 130 × 40 mm, thereby creating standardized ridge models with a crestal width of 3.5 ± 0.5 mm. The blocks had a density of 0.48 g/cm3 and a compressive strength of approximately 18 MPa, which are representative of D2 bone quality, ensuring that the model accurately reflects the corresponding biomechanical environment.

2.3. Study Groups

A total of 18 osteotomies were prepared and randomly allocated into three groups (n = 6 per group), according to the site preparation technique applied (CO, OD, or OS). An a priori power analysis was performed using G*Power software (version 29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) based on the study by Az and Ak [25] entitled “Comparison of Temperature Changes during Implant Osteotomy: Conventional, Single, and Osseodensification Drilling.” Specifically, the intergroup comparison of temperature changes of their study (D2 bone at 800 rpm and D4 bone at 1600 rpm) was used as the reference. The calculations indicated that, to detect intergroup differences in thermal outcomes with 90–95% power at α = 0.05, a minimum of six osteotomies per group (total n = 18) was required. Accordingly, six samples were allocated to each of the three groups in the present study. Although the power calculation was based on thermal changes, this sample size was also considered sufficient for evaluating ridge expansion outcomes under the same experimental conditions. The same operator carried out all osteotomy procedures to avoid inter-operator variability, and all ridge width measurements were performed by an examiner who was blinded to group allocation.

2.4. Osteotomy Protocol

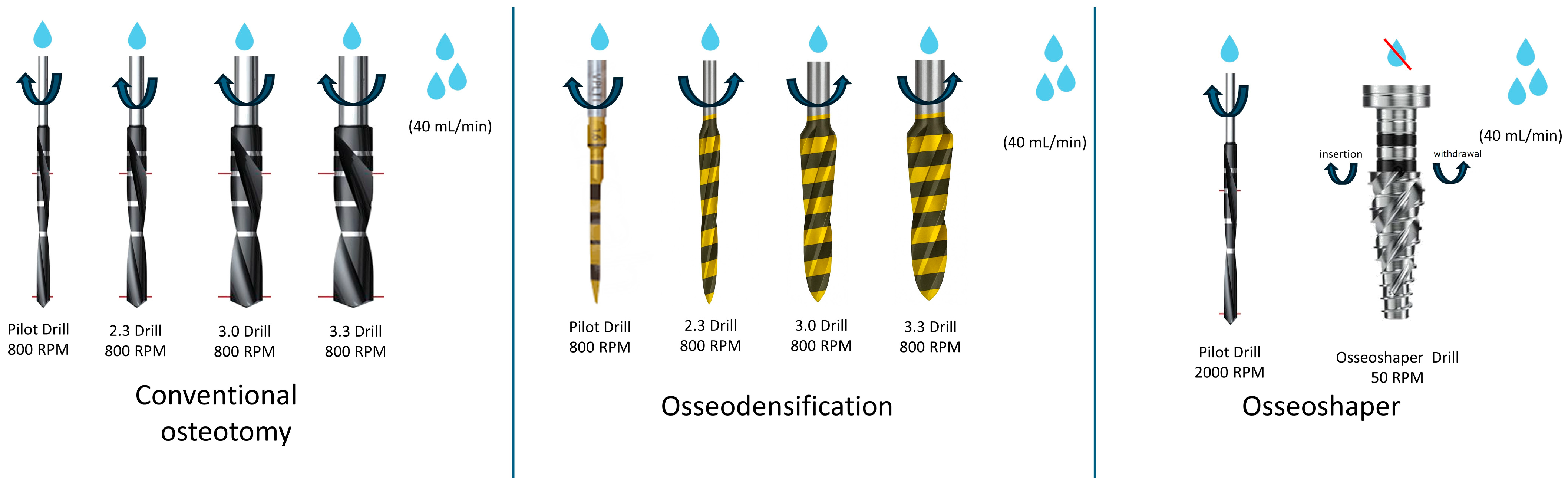

The osteotomy protocols, instruments, operating parameters, and irrigation conditions for each group are schematically illustrated in Figure 1. In addition, a representative intraoperative image of the drilling procedure showing the drilling procedures for CO, OD, and OS techniques is provided in Supplementary Figure S1 to depict the osteotomy phases and instrumentation used in each protocol.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of drilling sequences, operating parameters, and irrigation conditions for Conventional Osteotomy (CO), Osseodensification (OD), and OsseoShaper (OS) protocols. The figure illustrates the drill sequence, rotational speed (rpm), and irrigation settings used in each technique. Each group included six osteotomy sites (n = 6).

2.5. Thermal Monitoring

All osteotomies were performed at room temperature (21 ± 1 °C). ΔT was recorded using an infrared thermal camera (UNI-T UTI720E, UNI-T, Dongguan, China) positioned 25 cm from the osteotomy site. The camera was stabilized using the original foam holder, which prevented movement and maintained constant alignment with the sample throughout all recordings. The device had an infrared resolution of 256 × 192 pixels (49,152 pixels), a field of view of 56° × 42°, a spectral range of 8–14 μm, a thermal sensitivity (NETD) ≤ 50 mK, an accuracy of ±2 °C or ±2%, and an image acquisition frequency of 25 Hz. The emissivity setting was standardized at 0.95 for bone-like materials before each measurement, consistent with previous infrared thermographic studies on bone and polyurethane models [20,21,26]. The experimental setup and the infrared thermography monitoring process are illustrated in Supplementary Figure S2.

Thermal monitoring was performed by placing a fixed crosshair on the alveolar crest within the thermal video display, and single-point temperature values were recorded. The baseline thermal value (iT) was defined as the crosshair temperature during the one second immediately prior to osteotomy, while the maximum intraoperative thermal value (mT) was determined as the highest crosshair value observed during drilling. Peak values were visually confirmed by the operator to ensure consistency across all measurements. The thermal change (ΔT) was calculated as mT − iT.

Temperature was recorded at a single fixed point (crosshair positioned at the crestal region), as this site is expected to exhibit the highest temperature rise during osteotomy. This approach ensured standardized and reproducible measurements across all samples, although it does not capture potential variations at other regions of the osteotomy site.

To avoid cumulative heating, osteotomies were performed with a minimum spacing of 35 mm, and blocks were allowed to return to baseline thermal value before the next osteotomy. After each osteotomy, the thermal camera display was monitored until the crosshair temperature returned to within ±0.5 °C of the initial baseline value, which typically required approximately 2–3 min before the subsequent osteotomy was initiated.

2.6. Ridge Expansion Assessment

Each rigid polyurethane foam block measured approximately 130 mm in length, 40 mm in width, and 3.5 mm in crestal thickness. Both long crestal edges of each block were used for osteotomy preparation. Along each ridge, three osteotomies were prepared with a minimum spacing of 35 mm between adjacent sites to avoid thermal or mechanical interference. This distance was empirically determined based on preliminary trials to ensure that the heat generated at one site did not affect adjacent measurements.

Ridge width was measured once before and after osteotomy using a stainless steel digital caliper (TLS Robotik, Bağcılar, Istanbul, Türkiye); measuring range 0–150 mm; resolution 0.01 mm; accuracy ± 0.02 mm). The device was calibrated prior to each measurement session. Measurements were performed at 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm apical to the alveolar crest (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Expansion (ΔW) at each level was calculated as the difference between post- and pre-osteotomy values. All measurements were performed once by a single examiner with 17 years of clinical experience in oral and implant surgery. No repeated measurements were performed.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Given the relatively small sample size (n = 6 per group), the results of the normality test were interpreted with caution; therefore, sensitivity analyses were also performed using non-parametric alternatives (Kruskal–Wallis) to confirm the robustness of the findings. Depending on the distribution and comparison type, the following statistical methods were applied:

Intragroup comparisons (T0 vs. T1 ridge width at 3, 6, and 9 mm levels): Data showed normal distribution; therefore, paired t-tests were used. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Intergroup comparisons (changes in ridge width, ΔW): Data did not show normal distribution; thus, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed. When significant differences were detected, pairwise comparisons among CO, OD, and OS groups were conducted using Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction. Results are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR).

Thermal changes (ΔT): Although data showed normal distribution, the small group size was considered; therefore, one-way ANOVA was used as the primary test, and non-parametric verification (Kruskal–Wallis) was additionally performed. Results are reported as mean ± SD.

The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

2.8. Disclosure of GenAI Use

Generative AI (ChatGPT, GPT-5 model; OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA; https://chat.openai.com; accessed 25 October 2025) was used to assist in drafting parts of the Materials and Methods section, figure captions, and for language refinement. All scientific content, data analysis, and interpretation were performed by the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Ridge Expansion—Intragroup Comparisons

Intragroup comparisons showed that OD produced significant ridge expansion at all levels (3, 6, and 9 mm), whereas OS demonstrated significant changes at 3 mm and 6 mm. CO showed a significant difference only at the 3 mm level. Detailed intragroup results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intragroup comparisons of ridge width (T0–T1).

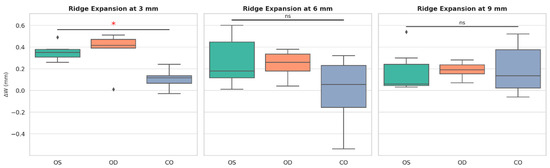

3.2. Ridge Expansion—Intergroup Comparisons

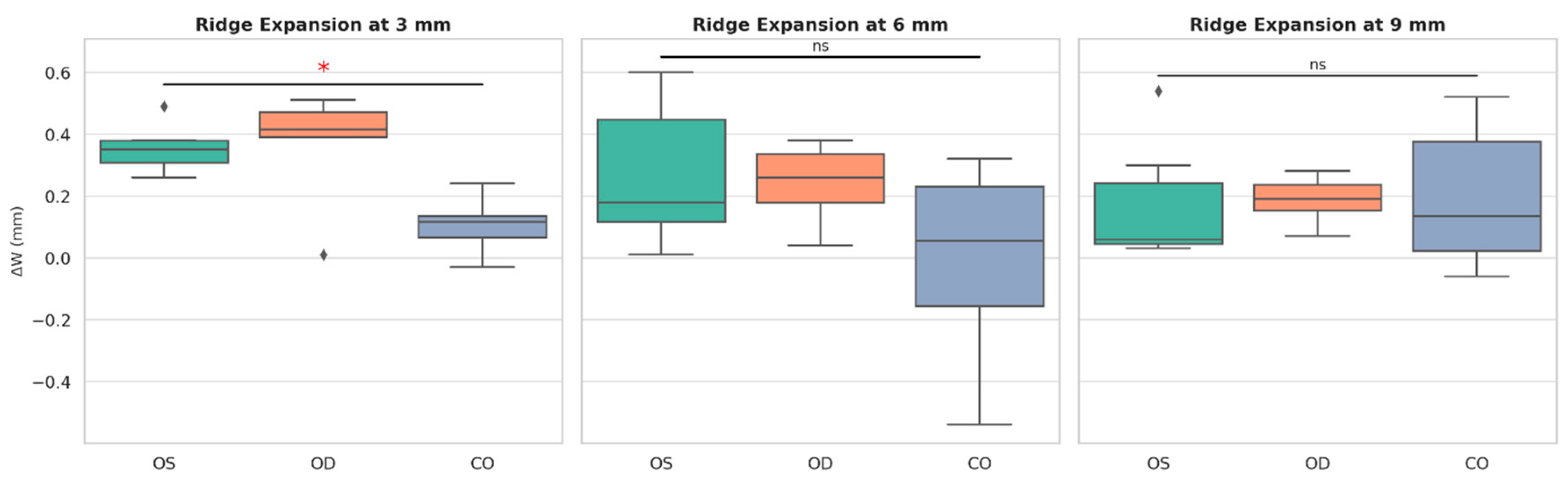

Intergroup comparisons of ΔW revealed a statistically significant difference only at the 3 mm level (p < 0.05). Post hoc analysis indicated that this difference resulted from greater expansion in OS compared with CO (p < 0.05). No significant intergroup differences were observed at the 6 mm and 9 mm levels. Results are summarized in Table 2a,b, while the intergroup differences are graphically illustrated in Figure 2, where a significant difference between OS and CO is indicated at the 3 mm level (* p < 0.05), and non-significant comparisons at 6 mm and 9 mm are marked as ns.

Table 2.

(a) Intergroup comparisons of ridge width changes (ΔW). (b) Post hoc Bonferroni results at the 3 mm level.

Figure 2.

Box plots illustrating ΔW at 3, 6, and 9 mm apical levels for the three osteotomy protocols. Boxes represent the median and interquartile range (IQR); whiskers indicate the range; black diamonds denote individual measurements. A statistically significant difference was observed between OS and CO at the 3 mm level (* p < 0.05), whereas no significant differences were found at 6 mm and 9 mm (ns).

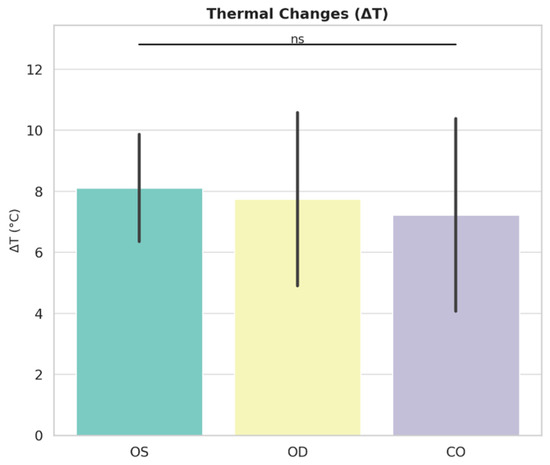

3.3. Thermal Changes

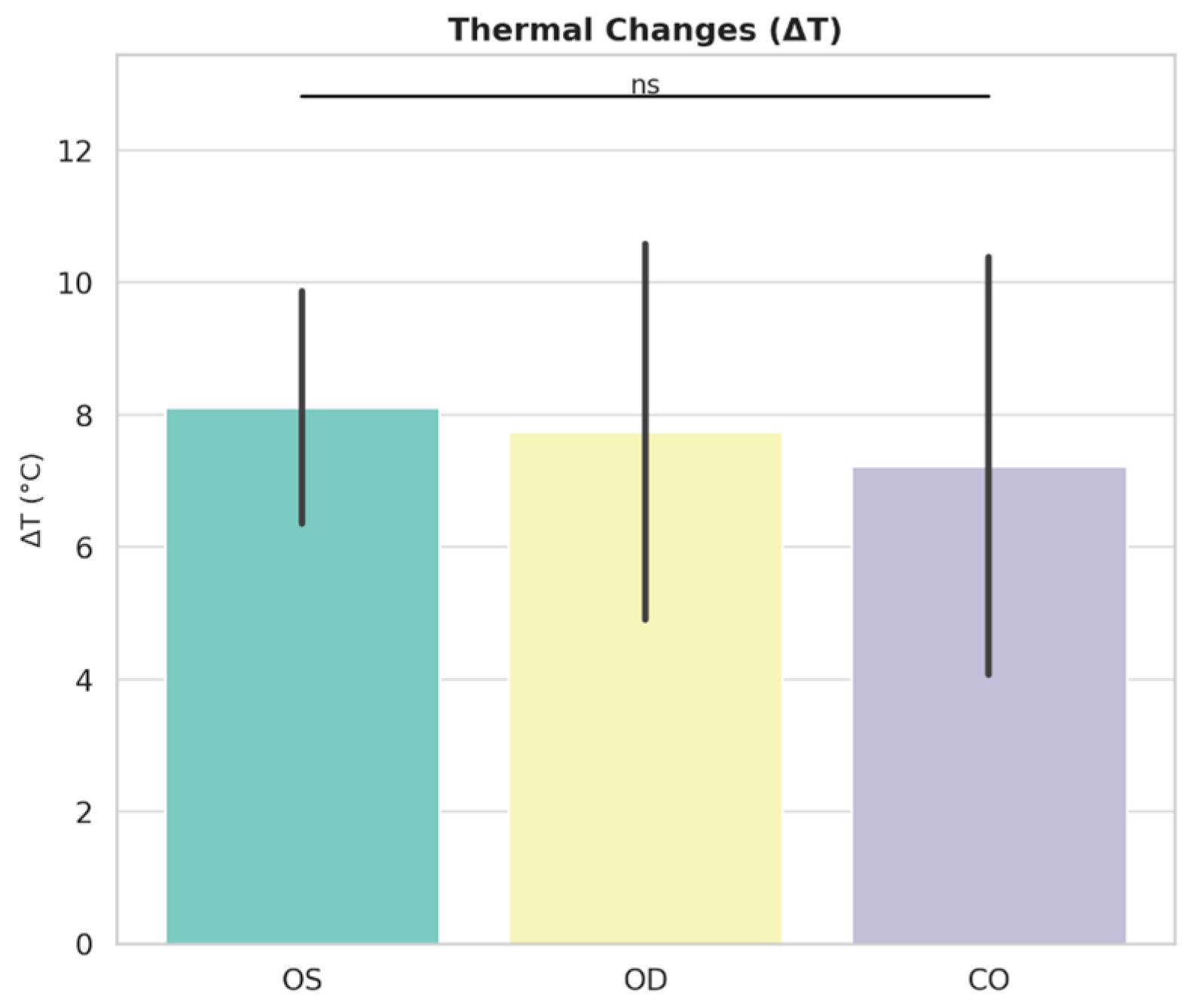

All protocols generated comparable intraoperative thermal changes, with mean ΔT values ranging between 7.4 and 8.2 °C. These values remained well below the critical 47 °C threshold for osteonecrosis, confirming the thermal safety of each protocol (Table 3, Figure 3). Intergroup comparisons showed no statistically significant differences among CO, OD, and OS (p = 0.830).

Table 3.

Intergroup comparisons of thermal changes (ΔT, °C).

Figure 3.

ΔT for the three osteotomy protocols. Bars represent mean values ± standard deviation (SD); black dots denote individual measurements. Intergroup comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences (ns), and all mean values remained well below the critical 47 °C threshold for osteonecrosis.

3.4. Overall Findings

Both OD and OS facilitated ridge expansion more effectively than CO, particularly at the crestal level. Thermal changes were comparable across all protocols, confirming their safety under the specified irrigation conditions (CO and OD with continuous irrigation; OS with an irrigated pilot followed by low-speed shaping without irrigation).

4. Discussion

This in vitro study compared three osteotomy protocols—CO, OD, and OS—with respect to ridge expansion and intraoperative thermal changes in narrow alveolar ridge models simulating D2 bone. The main findings were that OD achieved consistent intragroup widening at all levels, OS produced significant expansion at the 3 mm and 6 mm levels, and CO showed a small but significant increase only at the 3 mm level. At the intergroup level, statistically significant differences were observed only at the crestal 3 mm, where OS outperformed CO. All protocols generated comparable thermal changes, remaining well below the critical threshold of 47 °C, thus confirming their thermal safety under the specified irrigation conditions applied to each protocol.

Clinical and radiographic studies have reported similar findings, demonstrating that OD can allow implant placement in narrow ridges without the need for grafting procedures [8,10,11,12]. Meta-analyses have further confirmed that OD improves primary stability and ridge preservation compared with CO [9,11]. Nevertheless, some studies have cautioned that excessive lateral compaction may predispose to microfractures or cortical plate dehiscence [22,27,28], which could not be assessed in this in vitro model and therefore remains an important limitation for direct clinical translation. Future histological or micro-CT analyses in animal or human bone may help clarify whether such microfractures or cortical dehiscence occur in vivo.

The OS technique also demonstrated measurable expansion, with intragroup significance observed at the 3 mm and 6 mm levels and superiority to CO at the crestal level. This outcome is consistent with the design of the OS system, which incorporates low-speed, torque-sensitive site preparation and a tri-oval implant geometry [15]. In line with these features, previous reports have shown that controlled shaping facilitates predictable osteotomy formation while minimizing unnecessary bone removal [15]. Our findings support these reported advantages, although the current evidence base for the OS system remains limited compared with that for OD and CO, underscoring the need for further experimental and clinical validation.

When compared with OD, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two protocols in this study. However, this lack of distinction may be related to the standardized D2-density rigid polyurethane foam model and the narrow crest dimensions, which could have masked subtle clinical differences. To better clarify the relative advantages of OD and OS, future investigations should examine a broader range of bone densities and clinical scenarios. In line with this need, a recent ex vivo study by Uçkun et al. [16] reported that osteotomy strategy significantly influenced primary stability while maintaining intraosseous temperature within safe limits, reinforcing the clinical relevance of protocol selection. Particularly for OS, larger-scale and long-term studies are required to strengthen the current limited evidence base.

As expected, CO showed limited expansion, with a significant increase only at the 3 mm level. This finding is consistent with its subtractive drilling nature, whereby sequential drilling removes bone and decreases local density rather than preserving it [5,6,7]. Despite these inherent limitations, CO remains the most widely used and standardized protocol in implant dentistry, primarily because of its predictability and long clinical track record. In our study, CO also maintained thermally safe conditions, reinforcing its role as a reference technique for evaluating newer approaches. However, the minimal ridge changes observed are consistent with previous reports, confirming that CO provides little potential for ridge preservation in narrow alveolar crests.

All techniques maintained thermal safety, as the observed ΔT values translated into maximum temperatures (mT) well below the 47 °C threshold for osteonecrosis [17]. These results are consistent with previous studies, which have demonstrated that irrigation flow, drill design, and operational parameters are the primary factors influencing heat generation during osteotomy [18,19,20,21]. Although OD typically generates higher frictional resistance [9,11,21,22], sufficient irrigation likely prevented excessive heat accumulation, which may explain the absence of significant differences compared with CO. Similarly, low-speed, torque-limited preparation methods such as OS have been associated with favorable thermal performance [16,19,20,21].

Methodologically, it should be noted that thermal monitoring in this study relied on single-point measurements, which, while reproducible, may underestimate localized hot spots compared with region of interest (ROI) or multi-point analyses. Furthermore, infrared thermography records surface rather than intrabony temperatures, although its validity for comparative in vitro studies has been confirmed in previous studies comparing it with thermocouple-based methods [26].

Rigid polyurethane foam blocks with D2-equivalent density and compressive strength were selected to ensure standardization and repeatability. Such blocks are validated by ASTM for evaluating endosseous implant procedures [24] and are widely used in experimental studies to mimic the trabecular and cortical architecture of human bone [23,24]. However, unlike vital bone, they lack vascular perfusion, remodeling capacity, and biological variability, indicating that both ridge expansion and thermal dissipation values observed in this study may differ from those under in vivo conditions.

Clinically, our findings suggest that both OD and OS serve as effective alternatives to CO in narrow ridges, particularly at the crestal level, where ridge expansion is most crucial. Importantly, all techniques demonstrated thermally safe profiles under irrigation, supporting their clinical feasibility and reducing concerns regarding heat generation.

In line with prior reviews and meta-analyses on bone-preserving osteotomy strategies in narrow ridges, osseodensification has consistently been associated with significant crestal widening [9,11], while maintaining thermally safe profiles under adequate irrigation [17,18,25]. Clinical studies included in these reviews reported ridge gains of approximately 2–5 mm for OD in selected narrow-ridge indications [8,10]. However, the effect sizes remain variable and dependent on factors such as ridge width, cortical thickness, drill sequence, and irrigation parameters. Our in vitro findings are consistent with this evidence: both OD and OS achieved notable expansion at the crestal level, and all protocols remained below the critical 47 °C threshold when performed under technique-specific cooling conditions [17,25,26]. Collectively, these data place the present dimensional and thermal outcomes within a broader clinical context, without extending the inferences to primary stability, which was beyond the scope of this study.

This study has several limitations. First, the in vitro polyurethane foam model cannot fully replicate biological variability, vascular heat dissipation, or bone healing potential. Second, the relatively small sample size, while statistically powered for thermal outcomes, may not detect subtle differences in ridge expansion. Third, implant stability parameters such as insertion torque and resonance frequency analysis were not evaluated, although they are highly clinically relevant. Fourth, thermal monitoring relied on a single crosshair measurement point, which provides standardized and reproducible data but may potentially underestimate localized peak values compared to multi-point or ROI analyses.

In addition, ridge expansion was assessed using a single set of caliper measurements, without repeated assessments. Although a single examiner with 17 years of clinical experience in oral and implant surgery performed all measurements to minimize variability, intra-observer reliability was not calculated. Within the limitations of this in vitro design, the present study can be considered a pilot framework to guide future clinical investigations. Future studies should include repeated measurements and assess implant stability parameters under in vivo conditions to provide more robust clinical validation.

Future research should further expand upon these findings by including preclinical animal models or human clinical trials across different bone densities. In addition, evaluating implant stability parameters, such as insertion torque and resonance frequency analysis, as well as conducting histological assessments, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the biological and mechanical effects of bone-preserving osteotomy techniques. Moreover, long-term clinical studies are needed to determine the clinical success, predictability, and long-term performance of OD and OS protocols in daily practice.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, within the limitations of this in vitro study, both OD and OS demonstrated significantly greater ridge expansion compared with CO, while all techniques maintained thermally safe and controlled profiles. These findings support the clinical potential of bone-preserving osteotomy strategies for managing narrow alveolar ridges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152111669/s1, Figure S1: Representative photographs of the osteotomy procedures for the three drilling protocols: (A) Conventional Osteotomy (CO), (B) Osseodensification (OD), and (C) OsseoShaper (OS). The figure depicts the drilling stages and instrument positioning for each technique; Figure S2: Experimental setup for thermal monitoring showing (A) the infrared thermal camera (UNI-T UTI720E) positioned 25 cm from the polyurethane block and (B) a representative thermographic image captured during drilling; Figure S3: Schematic representation of the reference levels (3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm) used for ridge expansion analysis. Measurements were performed at these standardized depths below the crestal surface using a digital caliper; Figure S4: Representative photograph showing ridge width measurement using a digital caliper. The device was positioned perpendicular to the crestal surface to record ridge expansion at the reference levels defined in Supplementary Figure S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., G.M.Y.-Ü., and G.D.; methodology, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., and G.M.Y.-Ü. and G.D.; investigation, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., and G.M.Y.-Ü.; resources, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., G.M.Y.-Ü.; data curation, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., and G.M.Y.-Ü.; formal analysis, performed by an independent biostatistician under the coordination of F.G.Ç.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.Ç.; writing—review and editing, F.G.Ç., G.M.Y.-Ü., and G.D.; visualization, F.G.Ç.; supervision, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., G.M.Y.-Ü., and G.D.; project administration, F.G.Ç., M.Ç., and G.M.Y.-Ü. Experimental photographs were taken by G.M.Y.-Ü., and osteotomy preparation and implant placement procedures were performed by M.Ç. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI ChatGPT (GPT-5, September 2025 version) for text editing and figure preparation. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited the generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cenk Mısırlı (Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Trakya University, Türkiye) for kindly providing access to the thermal infrared camera (UNI-T UTI720E) used in this study. The authors also acknowledge the technical assistance received during the experimental procedures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CO | Conventional Osteotomy |

| OD | Osseodensification |

| OS | OsseoShaper |

| ΔW | Ridge width expansion |

| ΔT | Thermal change |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CCW | Counterclockwise |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| ROI | Region of interest |

References

- Koutouzis, T.; Bembey, K.; Sofos, S. The Effect of Osteotomy Preparation Techniques and Implant Diameter on Primary Stability and the Bone-Implant Interface of Short Implants (6 mm). Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2025, 40, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpudaswamy, S.; Ali, S.S.A.; Karthigeyan, S.; Ponnanna, A.; Nadhini, Y.; Eazhil, R. Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Two Different Drill Designs on Insertion Torque and Primary Stability during Osteotomy–An In Vivo Animal Study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16 (Suppl. 3), S2288–S2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, D.; Chochlidakis, K.; Barmak, A.B.; Agliardi, E.; Lo Russo, L.; Ercoli, C. Insertion and Removal Torque of Dental Implants Placed Using Different Drilling Protocols: An Experimental Study on Artificial Bone Substitutes. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möhlhenrich, S.C.; Heussen, N.; Modabber, A.; Kniha, K.; Hölzle, F.; Wilmes, B.; Abouridouane, M.; Klocke, F. Influence of Bone Density, Screw Size and Surgical Procedure on Orthodontic Mini-Implant Placement—Part A: Temperature Development. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Heitzer, M.; Bock, A.; Peters, F.; Möhlhenrich, S.C.; Hölzle, F.; Modabber, A.; Kniha, K. Relationship between Implant Geometry and Primary Stability in Different Bony Defects and Variant Bone Densities: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2020, 13, 4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misch, C.E.; Abbas, H. Contemporary Implant Dentistry, 3rd ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Althobaiti, A.K.; Ashour, A.W.; Halteet, F.A.; Alghamdi, S.I.; AboShetaih, M.M.; Al-Hayazi, A.M.; Saaduddin, A.M. A Comparative Assessment of Primary Implant Stability Using Osseodensification vs. Conventional Drilling Methods: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e46841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.A.; Mendes, J.M.; Salazar, F.; Pacheco, J.J.; Rompante, P.; Moreira, J.F.; Mesquita, J.D.; Adubeiro, N.; da Câmara, M.I. Osseodensification vs. Conventional Osteotomy: A Case Series with Cone Beam Computed Tomography. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A.D.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Bordea, I.R.; Xhajanka, E.; Romeo, D.M.; Romeo, M.; Zappone, C.M.F.; Malcangi, G.; Scarano, A.; Lorusso, F.; et al. The Effectiveness of Osseodensification Drilling Protocol for Implant Site Osteotomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Materials 2021, 14, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, R.D.; Bede, S.Y. The Use of Osseodensification for Ridge Expansion and Dental Implant Placement in Narrow Alveolar Ridges: A Prospective Observational Clinical Study. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 2114–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontes Pereira, J.; Costa, R.; Nunes Vasques, M.; Salazar, F.; Mendes, J.M.; Infante da Câmara, M. Osseodensification: An Alternative to Conventional Osteotomy in Implant Site Preparation—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, U.Y.; Rodrigues, S.J.; Talreja, K.S.; Mundathaje, M. Osseodensification—A Novel Approach in Implant Dentistry. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2018, 18, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, M.; Delgado-Ruiz, R.A.; Kucine, A.; Rugova, S.; Balanta, J.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L. Multistepped Drill Design for Single-Stage Implant Site Preparation: Experimental Study in Type 2 Bone. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2015, 17, e472–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-C.; Huang, H.-L.; Fuh, L.-J.; Tsai, M.-T.; Hsu, J.-T. Influence of Implant Length and Insertion Depth on Primary Stability of Short Dental Implants: An In Vitro Study of a Novel Mandibular Artificial Bone Model. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, G.; Staas, T.; Urban, I. A Retrospective Observational Study Assessing the Clinical Outcomes of a Novel Implant System with Low-Speed Site Preparation Protocol and Tri-Oval Implant Geometry. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe Uçkun, G.; Saygılı, S.; Çakır, M.; Geçkili, O. Effect of Osteotomy Strategy on Primary Stability and Intraosseous Temperature Rise: An Ex-Vivo Study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, R.A.; Albrektsson, T. The Effect of Heat on Bone Regeneration: An Experimental Study in the Rabbit Using the Bone Growth Chamber. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1984, 42, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehemar, S.H. Factors Affecting Heat Generation during Implant Site Preparation: A Review of Biologic Observations and Future Considerations. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 1999, 14, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, C.; Lucchiari, N.; Frigo, A.C.; Stecco, C.; Zanette, G.; Dotto, V.; Sivolella, S. Temperatures Generated during Implant Site Preparation with Conventional Drilling versus Single-Drill Method: An Ex-Vivo Human Mandible Study. Minerva Stomatol. 2019, 68, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchiari, N.; Frigo, A.C.; Stellini, E.; Coppe, M.; Berengo, M.; Bacci, C. In Vitro Assessment with the Infrared Thermometer of Temperature Differences Generated during Implant Site Preparation: The Traditional Technique versus the Single-Drill Technique. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2016, 18, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlhenrich, S.C.; Abouridouane, M.; Heussen, N.; Hölzle, F.; Klocke, F.; Modabber, A. Thermal Evaluation by Infrared Measurement of Implant Site Preparation between Single and Gradual Drilling in Artificial Bone Blocks of Different Densities. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 45, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misic, T.; Markovic, A.; Todorovic, A.; Colic, S.; Miodrag, S.; Milicic, B. An In Vitro Study of Temperature Changes in Type 4 Bone during Implant Placement: Bone Condensing versus Bone Drilling. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2011, 112, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comuzzi, L.; Tumedei, M.; D’Arcangelo, C.; Piattelli, A.; Iezzi, G. An In Vitro Analysis on Polyurethane Foam Blocks of the Insertion Torque (IT) Values, Removal Torque Values (RTVs), and Resonance Frequency Analysis (RFA) Values in Tapered and Cylindrical Implants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM F1839-08(2021); Standard Specification for Rigid Polyurethane Foam for Use as a Standard Material for Testing Orthopaedic Devices and Instruments. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Az, Z.A.A.; Ak, G. Comparison of Temperature Changes during Implant Osteotomy: Conventional, Single, and Osseodensification Drilling. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 22, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, S.; Egert, C.; Freitag-Wolf, S.; Mehl, C.; Kern, M. Intraosseous Temperature Changes during Implant Site Preparation: In Vitro Comparison of Thermocouples and Infrared Thermography. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2018, 33, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Arioka, M.; Liu, Y.; Aghvami, M.; Tulu, S.; Brunski, J.B.; Helms, J.A. Effects of Condensation and Compressive Strain on Implant Primary Stability: A Longitudinal, In Vivo, Multiscale Study in Mice. Bone Jt. Res. 2020, 9, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, G.A.; Romanos, G.E. Biological Mechanisms Underlying Complications Related to Implant Site Preparation. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 88, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).