Abstract

Speech recognition, as a key driver of artificial intelligence and global communication, has advanced rapidly in major languages, while studies on low-resource languages remain limited. Tongan, a representative Polynesian language, carries significant cultural value. However, Tongan speech recognition faces three main challenges: data scarcity, limited adaptability of transfer learning, and weak dictionary modeling. This study proposes improvements in adaptive transfer learning and NBPE-based dictionary modeling to address these issues. An adaptive transfer learning strategy with layer-wise unfreezing and dynamic learning rate adjustment is introduced, enabling effective adaptation of pretrained models to the target language while improving accuracy and efficiency. In addition, the MEA-AGA is developed by combining the Mind Evolutionary Algorithm (MEA) with the Adaptive Genetic Algorithm (AGA) to optimize the number of byte-pair encoding (NBPE) parameters, thereby enhancing recognition accuracy and speed. The collected Tongan speech data were expanded and preprocessed, after which the experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU (16 GB) using CUDA 11.8 under the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system. Experimental results show that the proposed method achieved a word error rate (WER) of 26.18% and a word-per-second (WPS) rate of 68, demonstrating clear advantages over baseline methods and confirming its effectiveness for low-resource language applications. Although the proposed approach demonstrates promising performance, this study is still limited by the relatively small corpus size and the early stage of research exploration. Future work will focus on expanding the dataset, refining adaptive transfer strategies, and enhancing cross-lingual generalization to further improve the robustness and scalability of the model.

1. Introduction

Speech recognition, as a core technology of artificial intelligence, is widely applied in security, education, healthcare, and defense, enhancing work efficiency and facilitating global communication. Within the global linguistic landscape, Tongan is a representative low-resource language. Although spoken by a relatively small population, it embodies rich cultural traditions and historical heritage, giving it significant value for cultural preservation and transmission. As vital channels for intercultural communication, low-resource languages have gained growing importance in global research and cultural exchange. Tongan, which integrates indigenous traditions with Western influences, represents a unique linguistic system that deserves greater attention in computational linguistics. Consequently, advancing research on Tongan speech recognition is not only academically significant but also contributes to the digital preservation and international dissemination of its linguistic resources.

In recent years, deep learning has greatly advanced speech recognition for resource-rich languages such as English and Chinese, thereby facilitating international linguistic communication [1]. In contrast, low-resource languages like Tongan still encounter major challenges, including data scarcity, complex dialectal variation, and significant cultural-contextual differences. Globally, more than 7000 languages exist, the majority of which are low-resource [2], and they generally lack sufficient annotated corpora as well as lexical and grammatical resources. For example, while high-resource languages such as English or Mandarin typically have access to over 10,000 h of labeled speech data, many low-resource languages possess fewer than 100 h of transcribed material, which severely limits model training and generalization. This deficiency severely constrains the effectiveness of conventional speech recognition systems. Furthermore, low-resource languages often encode unique cultural knowledge, while their dialectal diversity and expressive variability increase the difficulty of model training. Traditional methods based on Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), or Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) provide limited modeling capacity for such languages and struggle to capture complex acoustic features and fine-grained semantic patterns. In addition, extreme data sparsity makes it difficult to train deep models directly, as this frequently leads to overfitting and hinders further improvements in recognition performance.

Against this backdrop, transfer learning and end-to-end modeling emerge as promising strategies for low-resource language speech recognition. Transfer learning leverages pretrained models on high-resource languages and applies adaptive fine-tuning to capture phonetic features of the target language, thereby improving modeling efficiency and recognition performance [3]. This approach not only mitigates the shortage of annotated data but also enhances adaptability to linguistic variation. End-to-end systems, in turn, adopt unified neural architectures to directly map speech signals to text, simplifying the traditional pipeline of feature extraction, acoustic modeling, and language modeling [4]. Such frameworks achieve higher recognition accuracy and exhibit strong robustness to dialectal and pronunciation variations common in low-resource languages. Recent advances in neural architectures, such as Transformer and DeepSpeech, have further expanded opportunities in this field [5]. Despite these advances, models are prone to overfitting during transfer due to the scarcity of labeled data, while existing strategies often rely on fixed, coarse-grained parameter adjustments that lack fine-grained and dynamic adaptation across layers and linguistic features. Moreover, within end-to-end frameworks, the design of sub-word units and construction of efficient, expressive vocabularies remain critical obstacles—particularly for languages with complex structures and heterogeneous pronunciations. Therefore, developing targeted optimizations in transfer mechanisms and dictionary modeling is essential to further enhance the accuracy and robustness of speech recognition systems for Tongan and other low-resource languages.

To address these challenges, this study introduces three key innovations, focusing on data augmentation and sampling, cross-lingual transfer strategy, and dictionary parameter optimization for low-resource languages. First, to mitigate the issues of limited corpus size and imbalanced class distribution, a Supervised Random Augmentation with Deep Random Forest Filtering (SRA-DRF) algorithm is developed. This method integrates generative adversarial networks (GAN) with signal processing techniques to generate synthetic speech data and applies similarity-based filtering to retain high-quality samples. In addition, a weighted K-means stratified sampling strategy ensures balanced class representation, thereby enhancing feature learning and model generalization. Second, in the transfer learning stage, an adaptive layer-wise unfreezing strategy is proposed. This approach dynamically adjusts learning rates and performs top-down fine-tuning, preserving low-level general features while improving adaptability to target language characteristics. The effectiveness of this strategy is further validated through Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) visualization. Finally, for dictionary modeling, a hybrid MEA-AGA—combining the Mind Evolutionary Algorithm with the Adaptive Genetic Algorithm—is employed to automatically search for the optimal number of byte-pair encoding (NBPE) units, thereby improving recognition accuracy and decoding efficiency.

This paper is organized into seven sections as follows: Section 2 presents related work, reviewing the current research status of low-resource speech recognition, with a focus on challenges in data scarcity, transfer learning optimization, and dictionary parameter tuning, and briefly outlines the proposed strategies in this study. Section 3 details the proposed methods, including the design of the layer-wise adaptive transfer learning strategy and the MEA-AGA for dictionary parameter optimization. Section 4 describes the experimental setup, covering dataset sources, model configurations, and evaluation metrics. Section 5 reports the experimental results, including data augmentation, transfer learning, and dictionary optimization experiments, along with comparative analysis against mainstream methods to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approaches. Section 6 summarizes the overall contributions of this work in light of the experimental findings. Section 7 outlines future directions, addressing the current limitations and proposing potential areas for further exploration.

2. Related Work

2.1. Research Challenges

While deep learning has led to remarkable achievements in speech recognition for high-resource languages, its effectiveness in low-resource languages remains limited. These limitations mainly arise from three key aspects: data scarcity and corpus imbalance, model training strategy, and dictionary-based modeling optimization.

(1) Data scarcity and corpus imbalance

Low-resource languages often suffer from limited annotated data and a lack of publicly available corpora, resulting in a notable performance gap between their speech recognition systems and those of high-resource languages [6]. This scarcity poses significant challenges for effective modeling. In recent years, end-to-end speech recognition models have gained popularity due to their streamlined architectures and strong modeling capabilities. Researchers have begun applying these models to low-resource language tasks and have achieved preliminary progress.

Mukhamadiyev et al. [7] introduced a hybrid DNN-HMM and CTC-attention model for Uzbek speech recognition, achieving a WER of 14.3% on a medium-scale dataset. Kamper et al. [8] proposed a CNN-DTW-based keyword spotting system for Luganda, leveraging CAE features and multilingual bottleneck features, yielding over 27% performance gains under low-resource settings. Mamyrbayev et al. [9] developed a real-time recognition system for Kazakh using RNN-T, achieving a CER of 10.6% without relying on a language model, outperforming existing end-to-end approaches. Zhi et al. [10] conducted preliminary research on Mongolian using the ESPnet framework. Oukas et al. [11] built an end-to-end Arabic speech recognition model based on the Common Voice dataset, showing better performance with DeepSpeech compared to Wav2Vec. Changrampadi et al. [12] built a Tamil recognition system using DeepSpeech, expanding training data with online resources and semi-supervised techniques, and achieved a WER of 24.7%, surpassing Google’s results. Shetty et al. [13] incorporated language identity tokens and acoustic embeddings into a Transformer for Indian languages, achieving a 6–11% relative CER reduction compared to monolingual baselines. Pan et al. [14] introduced subword modeling and initialization strategies to improve recognition efficiency and convergence for Tibetan. Anoop et al. [15] developed the first Sanskrit speech processing system, using Mel-spectrogram augmentation and WFST decoding to achieve a 7.64% WER under ultra-low-resource conditions, demonstrating the feasibility of end-to-end architectures in such challenging scenarios.

Despite the promising potential of end-to-end approaches for various low-resource languages, several challenges remain. The scarcity of training data leads to overfitting and poor generalization while the large parameterization of end-to-end models makes convergence difficult and susceptible to local optima. Therefore, enhancing training efficiency and robustness remains a key focus in low-resource speech recognition research.

(2) Model training strategy

To address these challenges, transfer learning offers an effective solution. By leveraging knowledge acquired from source tasks, it improves learning efficiency and performance in target domains, substantially reducing dependence on large-scale labeled data. Transfer learning has shown notable advantages in low-resource settings and has achieved success in diverse applications such as medical diagnosis, image recognition, and industrial inspection [16,17,18,19]. As a result, it has become a widely adopted strategy in low-resource speech recognition research.

In low-resource speech recognition, fine-tuning pre-trained models remains the most commonly adopted transfer strategy. Mainzinger et al. [20] proposed adapter-based fine-tuning on Mvskoke, which significantly improved training efficiency and recognition accuracy, demonstrating strong parameter efficiency under limited data. Abdullah et al. [21] fine-tuned the Whisper model on Northern Kurdish using various parameter adaptation techniques, showing that adding auxiliary modules led to a notable WER reduction to 10.5%. Cui et al. [22] applied a multilingual, multi-task weakly supervised Whisper decoder to Burmese ASR, achieving a 5% absolute reduction in character error rate. Zeng et al. [23] employed transfer learning using a hybrid Transformer-LSTM structure for Malay ASR and introduced text augmentation strategies, achieving over 60% relative reduction in WER under low-resource conditions. Hjortnaes et al. [24] adopted transfer learning with the DeepSpeech model for Komi recognition and integrated a KenLM-based language model for output correction, resulting in more than 25% and 20% relative improvements in CER and WER, respectively. Bansal et al. [25] improved Mboshi speech-to-text translation using high-resource pretraining, achieving promising results with just four hours of data. Lee et al. [26] investigated cross-lingual transfer to predict phrase breaks in multilingual models, aiming for cost-effective adaptation. Baller et al. [27] enhanced RNN robustness to disfluent speech in low-resource languages such as Tunjia via transfer learning. Anoop et al. [28] introduced a MAML-based pretraining framework that outperformed multilingual joint training in rapidly adapting to Indian low-resource languages.

In recent years, research on transfer learning has further expanded toward multilingual and zero-shot paradigms, both of which aim to enhance model generalization under data-scarce conditions. In the multilingual direction, Yadav et al. [29] surveyed multilingual ASR models focusing on cross-lingual transfer and self-supervised learning, demonstrating that joint multilingual training can effectively improve recognition for low-resource languages. Yu et al. [30] proposed Master-ASR, a modular multilingual ASR framework that achieves scalable cross-lingual adaptation and robust low-resource performance through a modularize-then-assemble learning strategy, reducing inference overhead by 30% while improving character error rate by up to 2.41 over state-of-the-art models. For zero-shot learning, Yan et al. [31] introduced a transliteration-based framework for zero-shot code-switched ASR, which eliminates explicit language segmentation and leverages bilingual decoding with external language models to achieve effective recognition on Mandarin–English SEAME datasets. Another study [32] proposed a universal phonetic model that decomposes phonemes into phonetic attributes (e.g., vowels and consonants), enabling recognition for languages with no audio data and achieving an average 9.9% improvement in phone error rate across 20 unseen languages.

Transfer learning has shown considerable promise in mitigating the performance limitations of low-resource speech recognition. Nevertheless, most existing methods still rely on static fine-tuning strategies, which lack dynamic perception and adaptive adjustment mechanisms across different model layers and linguistic structures. In addition, the limited interpretability of current transfer mechanisms further constrains their optimization and wider applicability. These issues remain critical challenges in advancing low-resource speech recognition research.

(3) dictionary-based modeling optimization

In addition, dictionary-based modeling plays an essential role in improving recognition accuracy and has demonstrated strong adaptability across diverse languages. By optimizing the NBPE, recognition accuracy and output efficiency can be effectively balanced.

Hsiao et al. [33] explored the impact of sub-word vocabulary size on recognition performance using a VQ-BPE modeling approach for English and Chinese speech recognition. Their findings showed that setting the NBPE to 8000 led to accuracy improvements of 5.8% and 3.7% for English and Chinese, respectively, validating the effectiveness of dictionary granularity optimization. Deng et al. [34] proposed a Byte-Level BPE method that incorporates length and character penalty mechanisms. Trained on a 5k-hour bilingual corpus, the model achieved performance comparable to character-level models while reducing parameter size. Ma Jian et al. [35] introduced a BPE-dropout approach with sub-word length thresholds, which significantly reduced WER on THCHS30 and ST-CMDS datasets and improved recognition of rare and out-of-vocabulary words. In low-resource language studies, sub-word modeling strategies have also shown strong potential. Cai Yuqing et al. [36] addressed unit inconsistency in Tibetan ASR by combining BPE with a hybrid CTC-Attention framework. By adjusting the NBPE, the system achieved a WER of 9.0%, outperforming models based on syllables or components. Gaurav et al. [37] demonstrated that NBPE size significantly impacts recognition accuracy in Indian multilingual tasks, with a 7.5 k vocabulary yielding the best results. Turi et al. [38] developed an end-to-end ASR system for the Oromo language using a BPE tokenizer. Experiments showed that setting the NBPE to 500 achieved optimal performance, highlighting the value of sub-word unit tuning. Patel et al. [39] examined telephone speech recognition for Indian languages using a Conformer-based model, comparing character-level and various BPE granularities. The results indicated that a properly selected NBPE significantly improves accuracy, achieving a WER of 30.3% without external language model support, surpassing baseline methods.

Overall, NBPE, as a key parameter in sub-word modeling, exerts a significant influence on both the accuracy and efficiency of speech recognition systems. Although prior studies have demonstrated the benefits of NBPE optimization, most methods still depend on manual, experience-driven configurations. Systematic approaches for automated tuning and cross-lingual adaptation remain insufficiently explored and merit further investigation.

2.2. Proposed Method

In summary, low-resource speech recognition continues to face major challenges, including limited training data, insufficient adaptability in transfer learning, and the lack of systematic optimization in dictionary parameter tuning. To address these issues, this paper proposes the following improvements:

Data Augmentation: To mitigate the limitations of small-scale corpora, SRA-DRF algorithm is introduced. This method integrates GAN-based generation with signal processing techniques to produce high-quality synthetic speech, while similarity-based filtering ensures the reliability of augmented samples. In addition, to alleviate training bias caused by class imbalance, a weighted K-Means stratified sampling strategy is applied. This guarantees balanced class distributions across training, validation, and test sets, thereby improving model robustness and representation of diverse speech patterns.

Transfer Learning Optimization: To enhance the adaptability of pretrained models for low-resource tasks, a layer-wise adaptive transfer learning strategy is developed. This approach preserves general low-level acoustic features while progressively fine-tuning higher layers, guided by both the loss function trajectory and phonetic similarity between source and target languages. Moreover, Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) is employed to visualize feature alignment across layers, providing intuitive evidence of effective knowledge transfer.

Dictionary Parameter: Optimization: To overcome the lack of systematic sub-word granularity tuning, a novel MEA-AGA hybrid optimization algorithm is proposed, combining the Mind Evolutionary Algorithm with the Adaptive Genetic Algorithm. This approach automatically searches for the optimal NBPE, improving sub-word modeling accuracy without compromising decoding efficiency, and offering a more adaptive and stable strategy for low-resource language modeling.

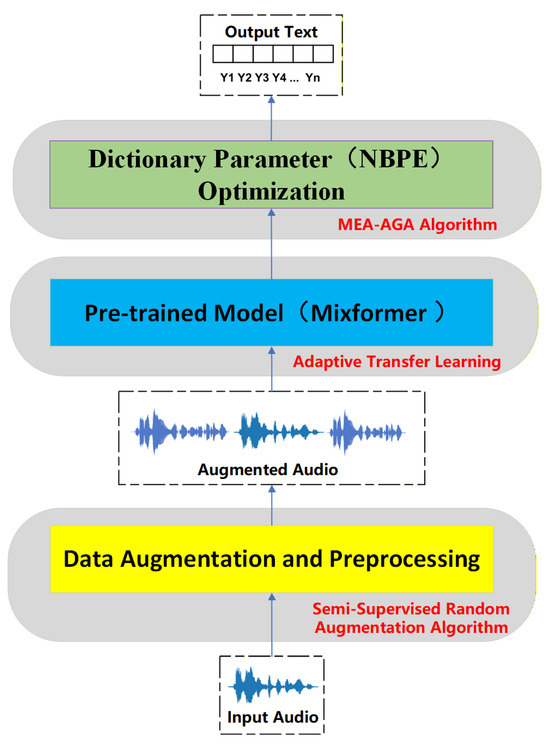

3. Methodology

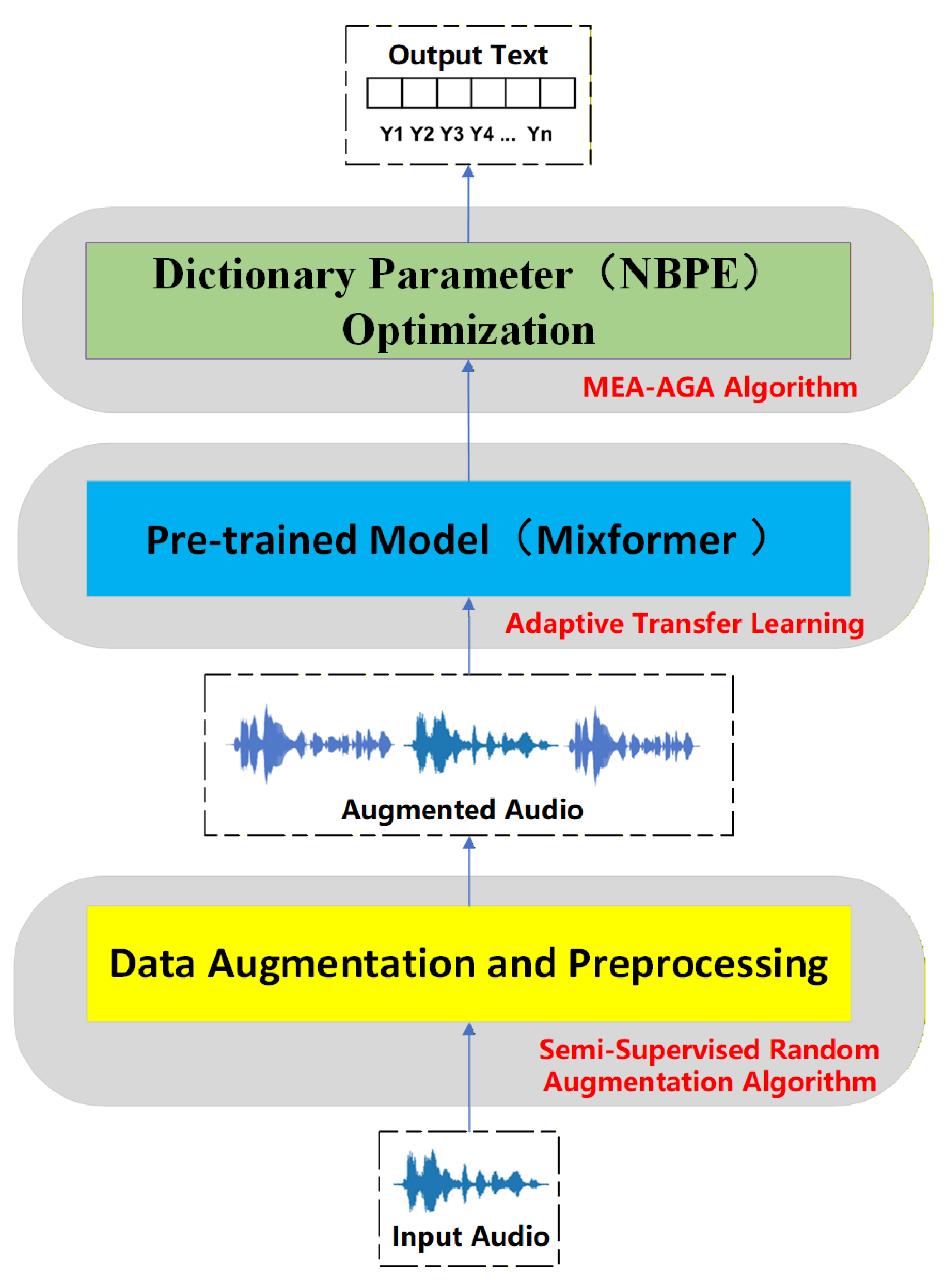

To provide a clear overview of the proposed framework, Figure 1 presents the overall model pipeline designed for low-resource speech recognition. The process begins with raw audio waveforms, which are subjected to data augmentation and preprocessing to expand the effective training corpus. The augmented data are then utilized within an adaptive transfer learning framework, where the pretrained Mixformer model is progressively fine-tuned to capture language-specific phonetic representations. Subsequently, the MEA-AGA is applied to optimize the NBPE parameters for dictionary modeling, enabling efficient subword decoding and accurate text generation.

Figure 1.

The model pipeline of the proposed low-resource speech recognition system.

3.1. Data Augmentation and Partitioning

In low-resource speech recognition tasks, data scarcity and class imbalance remain major factors that hinder model performance [40]. To improve training effectiveness and recognition accuracy, this section focuses on preprocessing and augmenting the original Tongan speech corpus, with the goal of constructing a balanced, diverse, and high-quality training dataset.

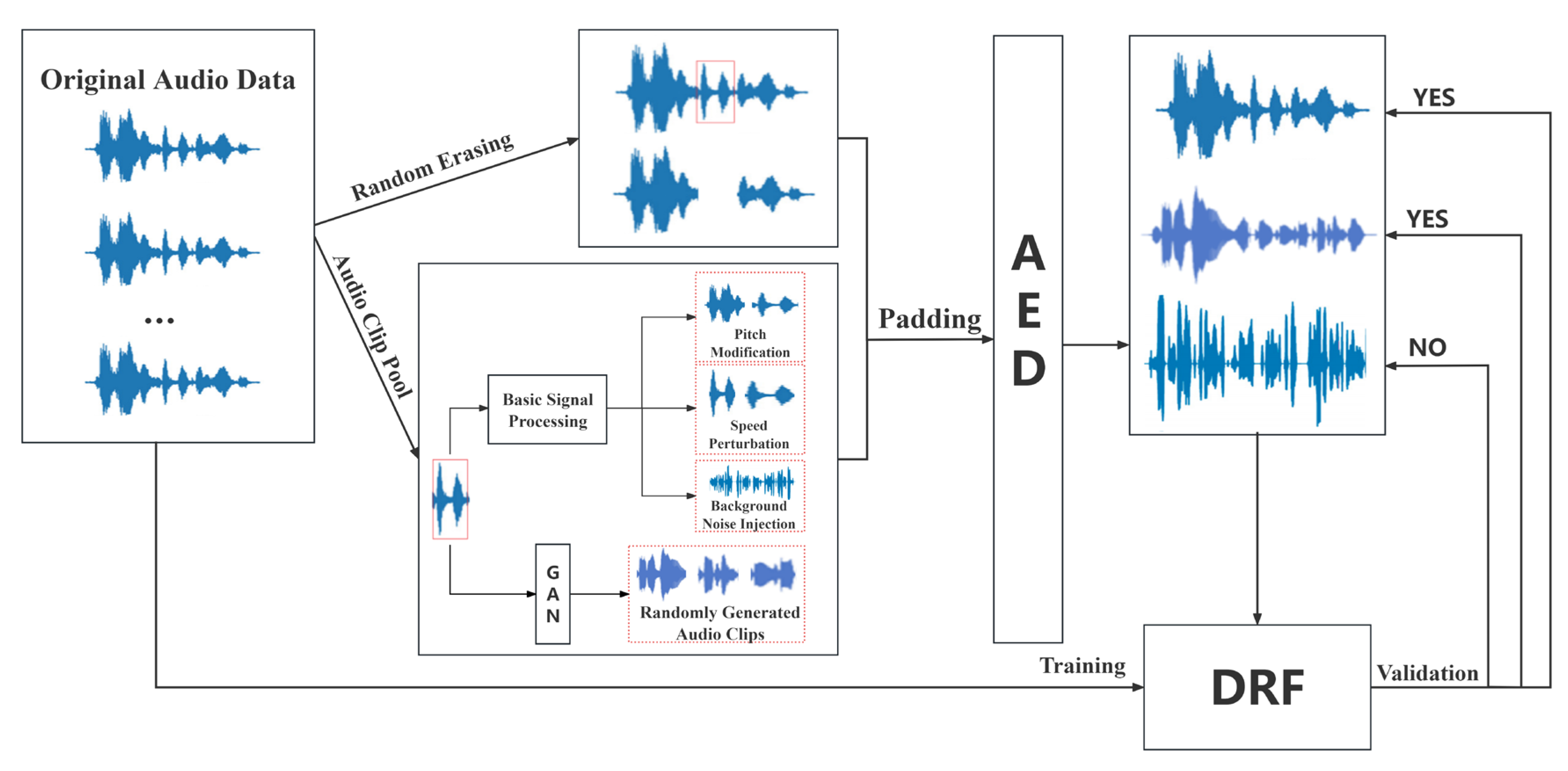

Data augmentation techniques are generally divided into signal processing-based and deep learning-based approaches. The former, such as speed perturbation, pitch shifting, and noise addition [41], are easy to implement but often introduce pronunciation distortions and fail to preserve language-specific features in low-resource settings. The latter, represented by Generative Adversarial Networks [42,43,44], generate higher-quality data but demand large datasets and significant computational resources, limiting their use in low-resource languages. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an SRA-DRF algorithm that integrates signal processing techniques with deep learning methods. This hybrid strategy not only increases data diversity but also reduces reliance on large datasets and computational resources, thereby enabling effective augmentation of Tongan speech data. The overall workflow is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Framework of the SRA-DRF (Supervised Random Augmentation with Deep Random Forest Filtering) algorithm.

Let denote the original Tongan audio feature matrix. Random segments are removed from , and the erased time spans are stored in a separate matrix referred to as the audio segment pool. The residual features, after the erasure process, are preserved in a new matrix denoted as .

is a masking matrix composed of 0 and 1, having the same dimensionality as . A value of 0 indicates that the corresponding data point is masked, while 1 means it is retained. denotes the amplitude of the frame of the utterance after the original data has been masked.

In the audio segment pool, signal processing and deep learning methods are jointly employed. On the one hand, the extracted audio segments are augmented through speed perturbation, pitch shifting, and noise addition. On the other hand, a GAN-based network is applied to generate additional realistic audio segments. The corresponding formulation is defined as follows:

where is the speed perturbation factor applied to modify speaking rate, is the pitch shift factor for adjusting vocal pitch. denotes the noise matrix that follows a Gaussian distribution, and is the noise strength coefficient. is the generator in the adversarial network; represents the noise input vector, which is randomly sampled and fed into the generator; denotes the generator’s parameters which control the properties of the generated audio. is the processed audio segment using signal-based operations on , while represents the audio segment generated by the GAN. These two types of augmented data are then combined into a unified audio segment pool :

Next, several candidate segments from the audio segment pool , which stores the erased portions of the original audio, are aligned with the residual speech features . An attention-based encoder–decoder (AED) module is then applied to integrate these segments, producing a supplementary data matrix :

Finally, the original Tongan corpus is utilized to train a DRF model. The augmented dataset is subsequently input to the model for evaluation, with the metric defined in Equation (8) adopted as the evaluation criterion.

Audio segments with higher scores are classified as Yes and retained as valid augmentations, while the rest are discarded.

After augmenting the speech data, the dataset must be partitioned in an appropriate manner to enhance the model’s generalization capability. A commonly adopted approach is K-Means clustering, which facilitates balanced class distribution [45,46,47]. Its mathematical formulation is defined as follows:

Here, denotes the cluster, represents the sample in the cluster, and is the cluster centroid.

This method performs well when clustering data with balanced class distributions. However, for tasks involving low-resource languages such as Tongan, the small dataset size and class imbalance may result in biased cluster centers. Direct application of traditional clustering often leads to convergence issues, misalignment between training and test sets, and reduced model stability and generalization capability [48].

To overcome these limitations, we modify the objective function by introducing a class-aware weighting term, which balances the influence of minority-class samples during clustering. The revised formulation is defined as:

The weight is used to adjust the influence of each sample in the cluster based on its class distribution, and is defined as:

where denotes the frequency of the class label , to which sample belongs in the dataset. The detailed definition is:

Here, is the total number of samples in the dataset, and is the number of samples belonging to class , which is calculated as:

is the indicator function, which equals 1 if the condition is satisfied, and 0 otherwise. denotes the full dataset. Finally, by substituting the above expressions, the improved K-Means clustering objective function is given as:

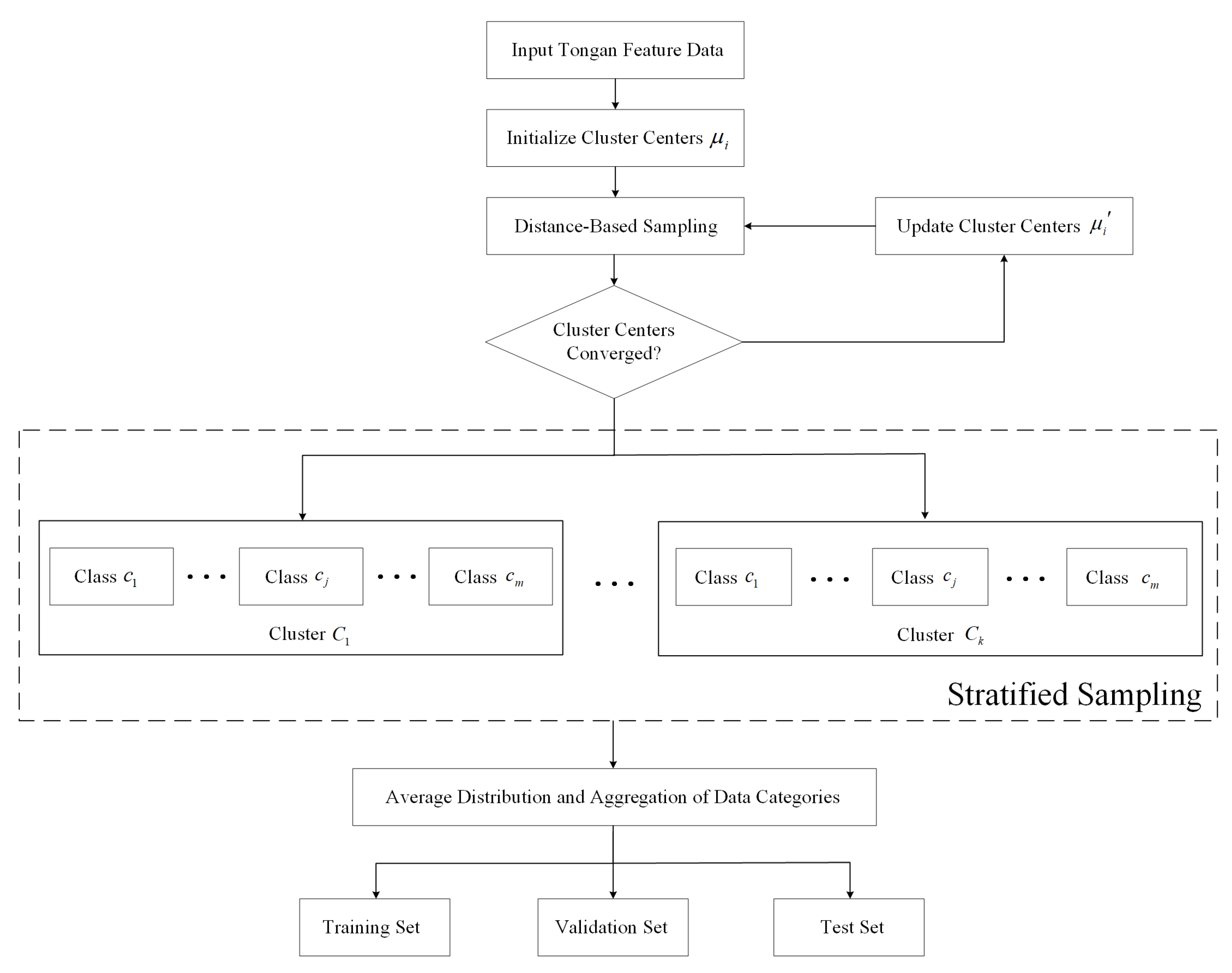

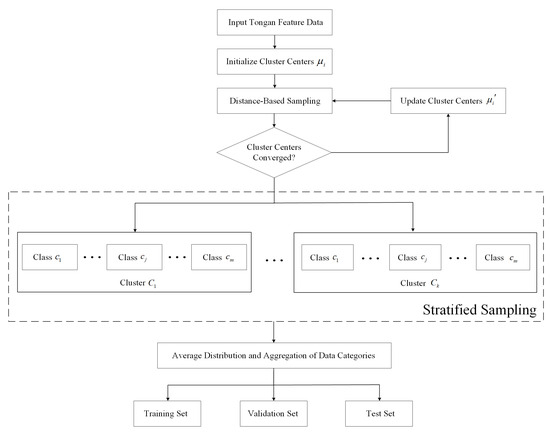

To achieve more balanced data partitioning, this study integrates stratified sampling with the improved weighted K-Means clustering method. Specifically, samples are first stratified according to their distances from the cluster centroids, and proportional sampling is then applied within each cluster to ensure balanced class representation across the training, validation, and test sets. The overall procedure of this data partitioning method is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tongan data partitioning flowchart based on weighted stratified sampling.

The basic steps of the algorithm are as follows:

(1) Based on the features extracted from the input Tongan speech data, perform statistical analysis to initialize k cluster centers (where i = 1, 2, …, k and k is the number of clusters).

(2) Calculate the weighted distance from each sample to each cluster center and assign the sample to the nearest cluster. For a given sample and cluster center , the distance is computed according to Equation (14).

(3) Update each cluster center based on the current cluster members and their weights. The new cluster center is computed as:

(4) Check whether the new cluster centers meet the convergence condition. If convergence is achieved, the algorithm terminates; otherwise, return to step (2) for further updates.

(5) After clustering, compute the proportion of each class within each cluster:

Here, , and represent, respectively, the proportion, the number of samples, and the total number of samples of class within cluster .

(6) Finally, stratified sampling is performed within each cluster based on the class distribution and the specified data split ratios. The total number of samples selected from each cluster is then used to construct the training, validation, and test sets. The formulas are defined as follows:

Here, , and represent the total number of training, validation, and test samples, respectively. is the number of clusters, is the number of classes, and , and represent the number of training, validation, and test samples from class within cluster .

3.2. Layer-Wise Unfreezing for Adaptive Transfer Learning

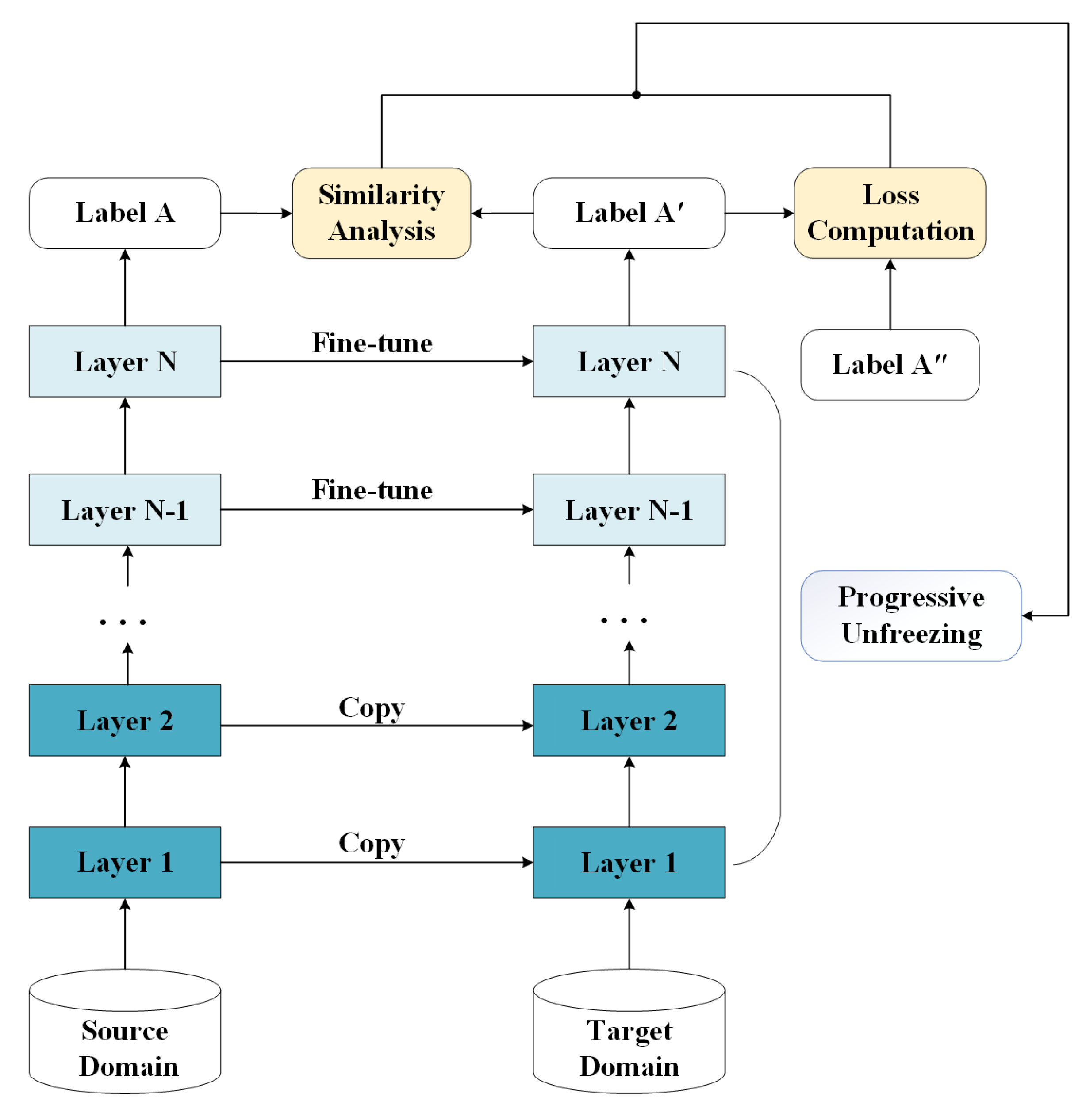

Transfer learning, which adapts knowledge from a source domain to a target task, has proven particularly effective in low-resource or highly specialized scenarios and has therefore attracted considerable academic attention [49]. However, for large-scale models such as Transformer, Wav2Vec, and GPT, significant challenges remain, including the risk of negative transfer and high computational costs. To address these issues, this study proposes an adaptive transfer learning approach based on layer-wise unfreezing. The overall network architecture and algorithmic workflow are illustrated in the figure below.

The model architecture adopted in this study incorporates a fine-grained feedback mechanism with a clear distinction between frozen and tunable layers, thereby improving the precision and efficiency of transfer learning. The unfreezing process follows a top-down strategy, where the number of trainable layers and the corresponding learning rates are initialized according to cross-lingual similarity. This design preserves pre-trained knowledge while gradually adapting the model to the target task. The overall architecture of the proposed adaptive transfer learning network is illustrated in Figure 4. As training progresses, a loss-driven adjustment strategy is applied to dynamically refine the unfreezing process, enabling more adaptive and task-specific optimization. The detailed training procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Figure 4.

Layer-wise unfreezing adaptive transfer learning network architecture.

The specific steps of the proposed algorithm are as follows:

(1) Model Initialization: This includes setting the maximum number of iterations , the pretrained model , the transfer model , the number of model layers , and the initial learning rate .

(2) Similarity and Loss Evaluation: The similarity between source and target languages is calculated using Cosine similarity, denoted as . Simultaneously, the overall training loss is computed to guide the subsequent unfreezing strategy.

(3) Determining the Number of Unfrozen Layers: The initial number of unfrozen layers is determined based on the computed similarity score. The definition and iterative update of the unfreezing depth are formulated as follows:

where and represent the change in loss values at iterations and , respectively, and the step size is set to 1.

(4) Learning Rate Adjustment: The learning rate is dynamically adjusted based on similarity and loss:

where and are time-dependent weighting coefficients that control the influence of similarity and loss, respectively. At the early stage of training, is set relatively high and decreases gradually, while starts low and increases gradually as training progresses.

where is a positive constant (set to 0.1) to control the rate of decay and growth. The initial values are and .

(5) Unfreezing Execution: Based on the determined unfreezing depth, the model is incrementally unfrozen from the top layer downward. The learning rate is applied accordingly to fine-tune each layer.

(6) Convergence Check: The process checks whether convergence criteria are met. If not, the algorithm returns to step (2) for further updates.

(7) Final Output: Once convergence is achieved, transfer training is completed, and the final target language recognition model is obtained.

To further assess the feature changes during the transfer process, this study employs the CKA similarity matrix to quantitatively analyze key layers of the network before and after fine-tuning. CKA measures the alignment of representations in kernel space across different layers or stages and is widely used in neural network visualization and interpretability research [50]. By comparing similarity scores across layers, the analysis reveals how hierarchical features are adjusted during transfer, providing theoretical support for the effectiveness of the layer-wise unfreezing strategy.

| Algorithm 1: Adaptive layer-wise unfreezing and learning rate scheduling for transfer learning |

| Require: Mpre, n, η0, α0, β0, L Ensure: Mtrans

|

3.3. Dictionary Parameter Optimization Driven by MEA-AGA

In automatic speech recognition, dictionary construction is a critical component, typically achieved through sub-word unit segmentation to standardize output. Among these, NBPE serves as a core parameter that directly impacts vocabulary coverage, sequence length, and model complexity. A small NBPE can increase coverage and reduce annotation cost, but it leads to longer sequences and greater training difficulty. Conversely, a large NBPE may simplify training but could weaken the model’s linguistic expressiveness [36]. In low-resource scenarios such as Tongan, optimizing NBPE is crucial to improving recognition performance. To this end, this study proposes the MEA-AGA method to determine the optimal dictionary configuration for Tongan.

The genetic algorithm (GA) is an optimization method inspired by natural evolution, which searches for optimal solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. However, traditional GA uses fixed parameter settings, making it prone to local optima and lacking adaptability. The adaptive genetic algorithm (AGA) addresses this by introducing dynamic parameter adjustment mechanisms, allowing the crossover and mutation rates to evolve throughout the search process, thereby enhancing global exploration and algorithm robustness. The functions are defined as follows:

In the equations, , , and are constants between 0 and 1. and denote the maximum and average fitness of the current population, respectively; represents the fitness of the better individual among the two selected for crossover; corresponds to the fitness of the individual undergoing mutation.

However, Equations (24) and (25) consider only individual fitness and neglect the overall evolution of the population, making it difficult to capture population-wide trends and potentially leading to local optima. To address this limitation, this study introduces improvements to both the crossover and mutation probability functions:

represents the maximum crossover probability, and is the maximum mutation probability. As shown in the equations, regardless of an individual’s fitness value, both the crossover and mutation probabilities are prevented from dropping to zero. This not only effectively preserves high-performing individuals but also avoids premature convergence to local optima.

However, the exponential terms in the equations tend to magnify differences in fitness values. When an individual’s fitness deviates substantially from the population mean, the resulting rapid growth or decay of the exponential component may induce excessive fluctuations in crossover and mutation probabilities. Such instability can lead to over-exploration and undermine the robustness of the algorithm. To mitigate this issue, fitness variance is introduced to further refine and stabilize the equations:

is a statistical measure used to quantify the dispersion of fitness values within the population. A larger variance indicates greater differences in individual fitness, while a smaller one implies a more uniform population. The calculation formula is as follows:

By incorporating fitness variance, the crossover and mutation probabilities are adjusted more smoothly, thereby suppressing drastic fluctuations induced by extreme fitness values. This adjustment enhances the stability of the algorithm and strengthens its capability to explore the solution space effectively.

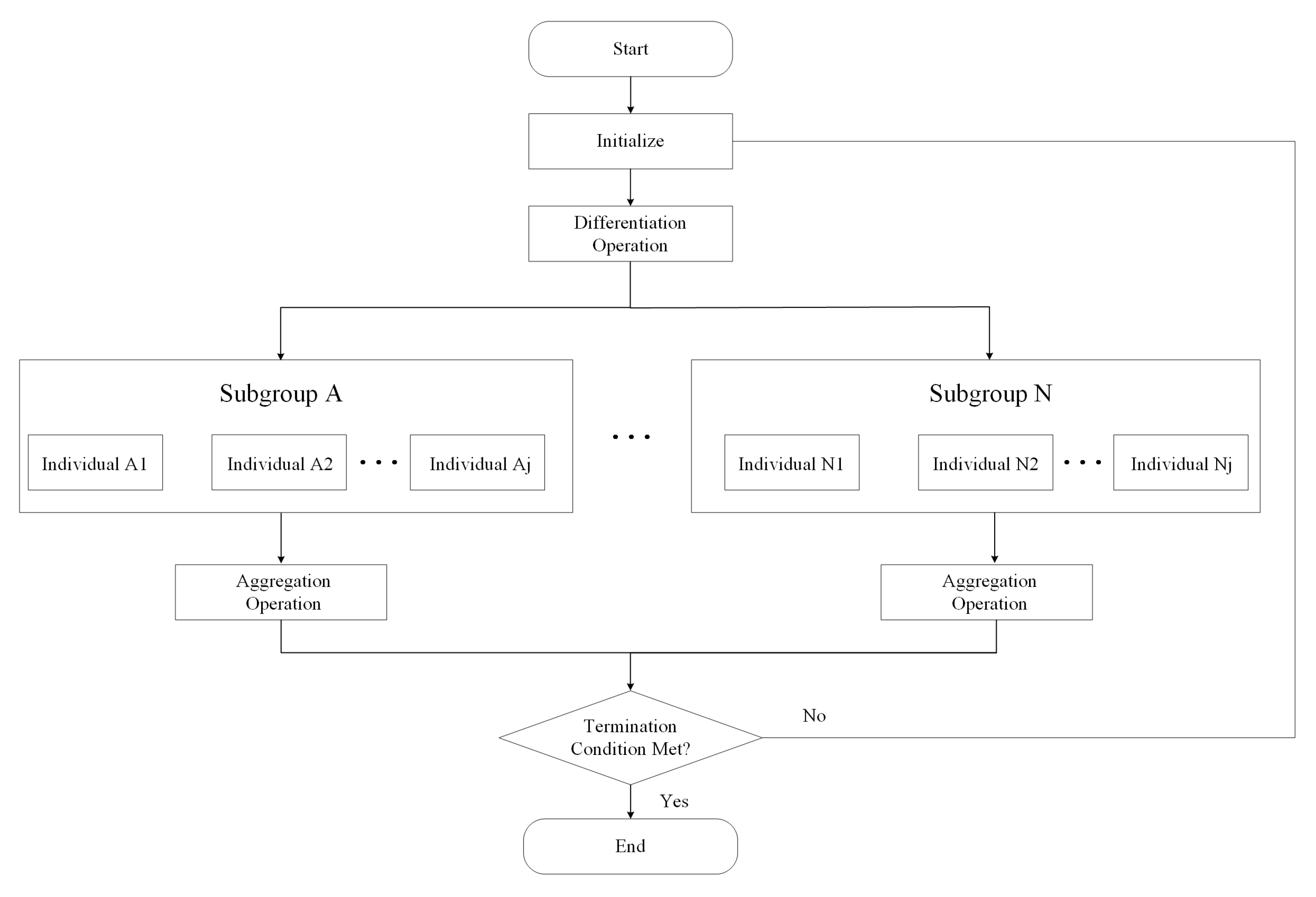

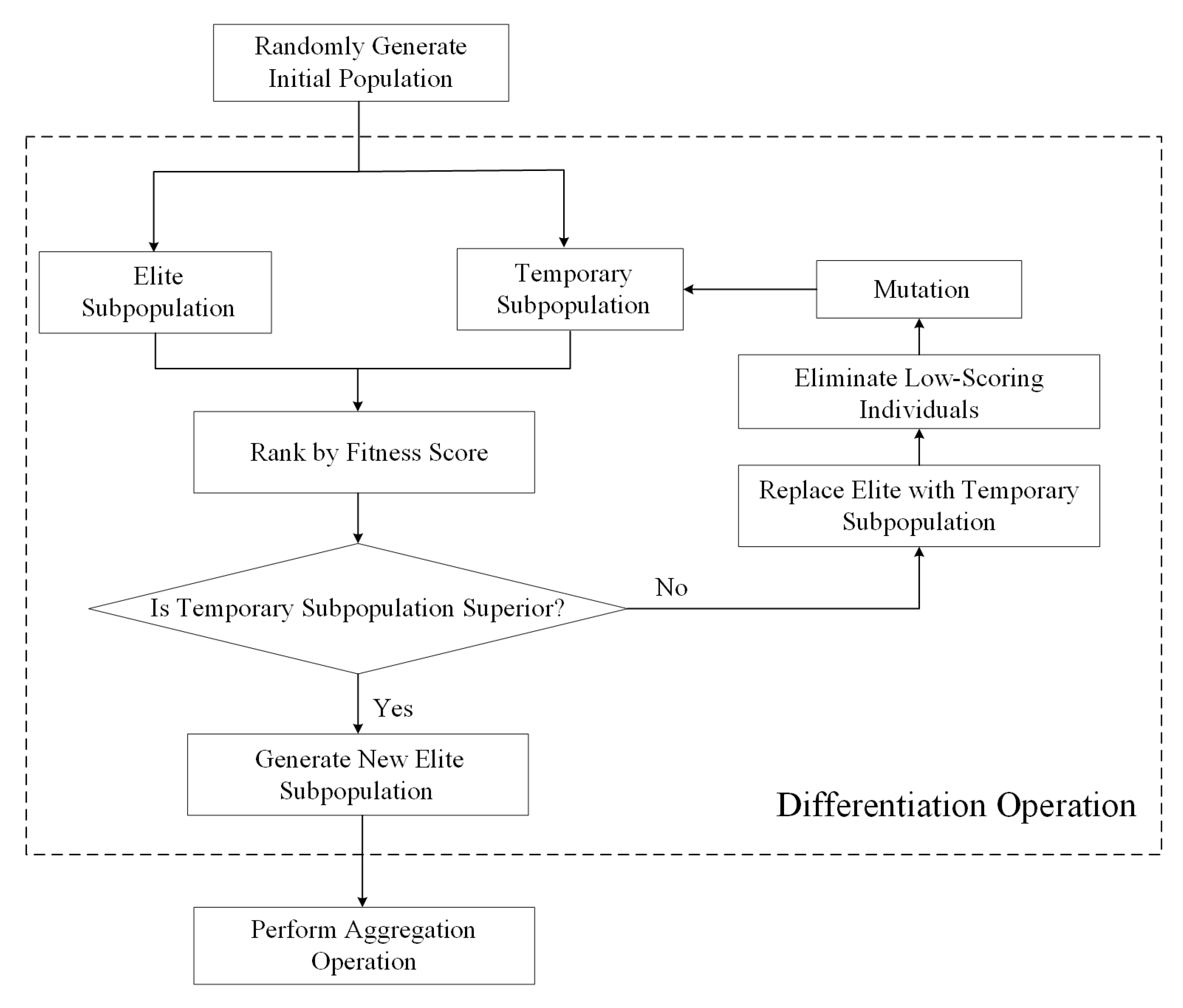

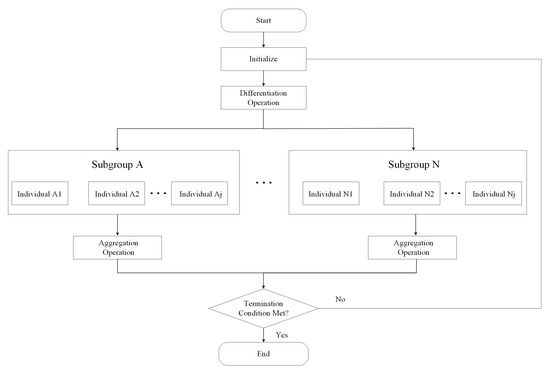

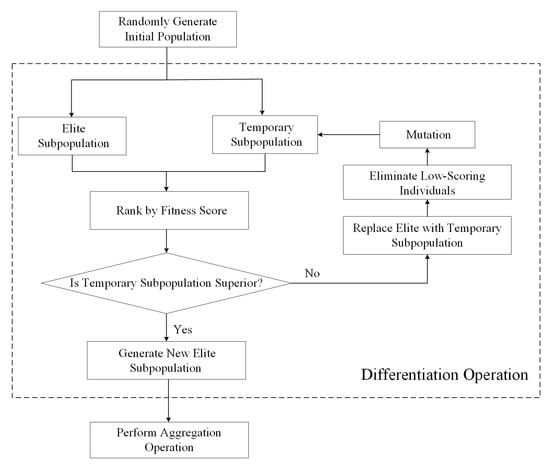

Although this strategy increases parameter flexibility, it is still susceptible to local optima in complex search spaces, particularly when fitness differences among individuals are minimal. This limitation reduces adaptability and hinders global exploration. Moreover, AGA encounters challenges in balancing evolutionary speed and search quality: overly aggressive adjustment rates may lead to divergence and inefficiency, whereas overly conservative rates restrict the search range and degrade performance. To address these limitations, this study integrates the MEA framework to further enhance AGA. MEA simulates human-like rapid evolution through learning and innovation, thereby improving both adaptability and global search capability. In each iteration, a randomly initialized population undergoes fitness-based selection to generate a central individual, which partitions the population into elite and temporary subpopulations. The elite group preserves high-quality solutions, while the temporary group performs exploratory search, together enabling cooperative optimization. The procedure is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

MEA flowchart.

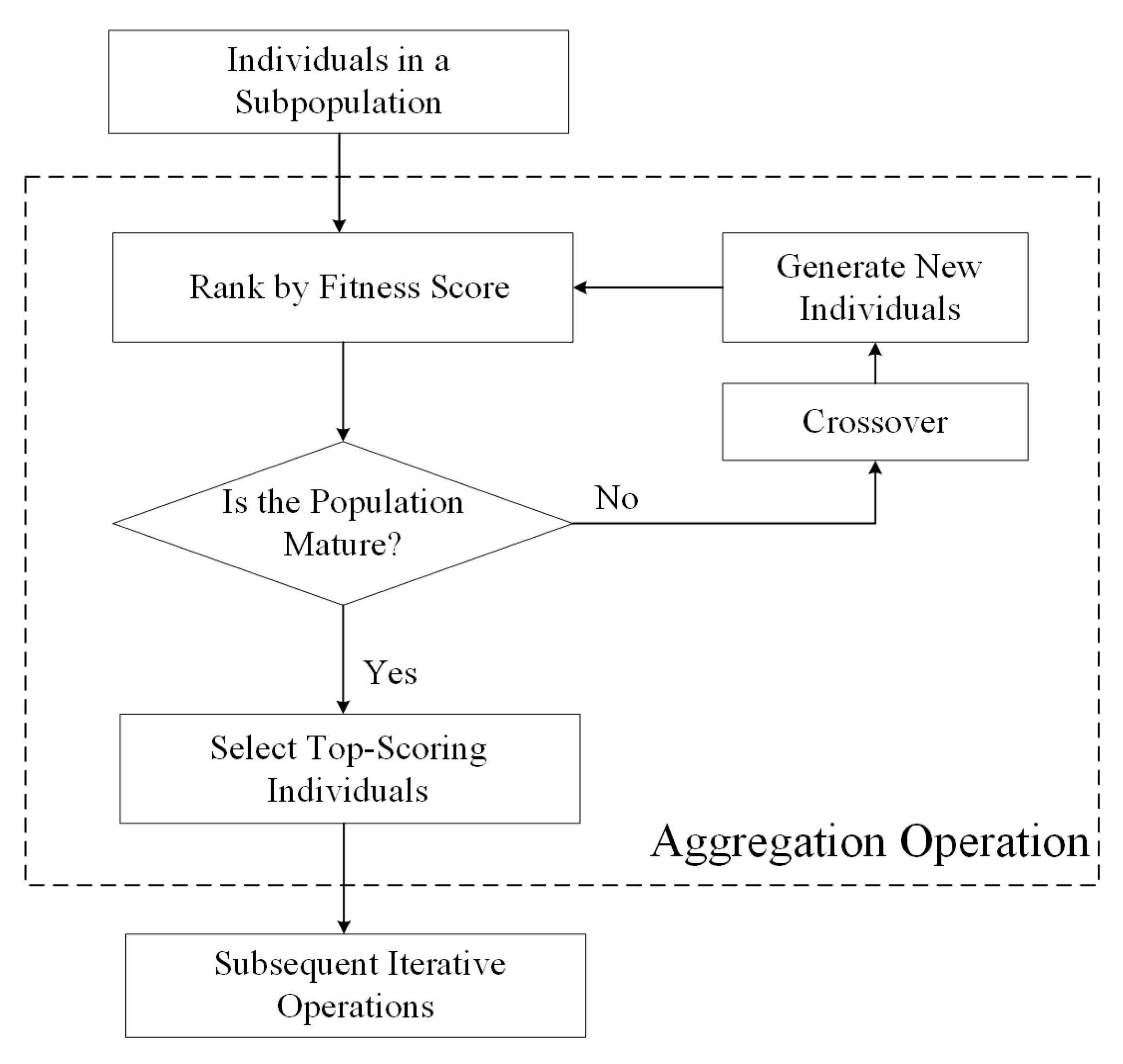

As illustrated in the figure, the algorithm achieves a balance between global exploration and local optimization through a two-phase “diversification–convergence” strategy. During the diversification phase, population diversity is increased to promote broad exploration of the search space and identify multiple promising candidate solutions. In the subsequent convergence phase, these candidate solutions are refined to enhance solution quality and improve convergence efficiency. The detailed procedures of the diversification and convergence phases are depicted in Figure 6 and Figure 7, respectively.

Figure 6.

Differentiation operation flowchart.

Figure 7.

Aggregation operation flowchart.

In the global search phase, a diversification operation is first conducted. The population is divided into elite and temporary subpopulations according to fitness values, facilitating competitive interactions that help identify multiple promising global optima. If a temporary subpopulation outperforms the current elite subpopulation in terms of fitness, it replaces the elite group and is incorporated into the set of optimal solutions. Meanwhile, the temporary subpopulation with the lowest fitness is discarded and reinitialized across the entire solution space. Since this phase emphasizes search breadth and allows for larger parameter perturbations, the mutation mechanism from (29) is adopted to expand the search range.

In the local search phase, a convergence operation is carried out. This operation involves a two-stage refinement of the elite subpopulation obtained during the diversification phase. Guided by the fitness function, it seeks to further enhance solution quality and approximate the global optimum. To prevent excessive parameter perturbation, the crossover mechanism is applied, with the crossover rate calculated using (28), thereby improving the precision of local search. When the optimal individual remains stable across successive iterations and no longer changes, the subpopulation is considered matured, marking the completion of the convergence process.

In summary, the MEA-AGA is employed to optimize the NBPE parameter in Tongan speech recognition, with the objective of balancing recognition accuracy, decoding speed, and training cost. Prior to the optimization process, a fitness function is defined to comprehensively evaluate multiple factors in the recognition process, including model accuracy, decoding efficiency, and training time. The calculation formula is as follows:

, , , and represent the word error rate on the validation set, the word error rate on the test set, the number of words recognized per second, and the model training time, respectively. The corresponding weight coefficients , , , and are set to 0.3, 0.3, 0.3, and 0.1, reflecting the equal importance of recognition accuracy and decoding speed, while giving relatively less emphasis to training time. In addition, to eliminate the influence of differing units of measurement, WPS and training time are normalized to ensure that all evaluation indicators fall within a comparable range.

The overall procedure of the proposed optimization algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 2, and its detailed steps are described as follows:

(1) Parameter Initialization: Set the maximum number of iterations, population size , crossover probability , and mutation probability .

(2) Population Initialization: Randomly generate 10 initial individuals .

(3) Fitness Evaluation: Calculate the fitness scores of all individuals in the population using (30).

(4) Diversification Operation: Sort individuals based on their fitness scores. The top five individuals form the elite subpopulation , and the bottom five form the temporary subpopulation . Determine whether the fitness score of the newly generated temporary subpopulation is higher than that of the elite subpopulation. If so, apply mutation (29) to the lowest-scoring temporary individual to generate a new temporary subpopulation , and return to step 3; otherwise, the diversification phase is complete, and the elite subpopulation is finalized.

(5) Fitness Calculation of the New Elite Subpopulation: Recalculate the fitness scores of all individuals in the new elite group using (30).

(6) Convergence Operation: Sort individuals in the elite subpopulation by fitness; the highest-scoring individual is identified as the winner. Determine whether the population has matured. If the winner changes, perform crossover (28) on the remaining individuals to generate new individuals, and return to step 5; otherwise, the convergence phase is complete, and the global optimal individual is obtained.

(7) Termination Check: Determine whether the stopping condition is met. If the maximum number of generations has been reached, the process ends and the current optimal NBPE value is output; otherwise, return to step 3 to continue iteration.

(8) Dictionary Construction: Based on the optimal NBPE value, segment Tongan words and construct the Tongan dictionary, which serves as a standard for both training and inference, ultimately enabling accurate and efficient Tongan speech recognition.

| Algorithm 2: MEA-AGA for Dictionary Parameter Optimization |

| Require: N, nmax, Pc, Pm, pop1~pop10 Ensure: Optimal NBPE

|

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Dataset Configuration

In transfer learning, the choice of source language plays a crucial role in determining model performance. This is especially relevant for low-resource speech recognition, where selecting a source language with abundant resources and phonetic structures similar to the target language can significantly improve transfer effectiveness and generalization. Tongan, the official language of the Kingdom of Tonga, belongs to the Polynesian language family and represents a typical low-resource case [51]. Due to historical colonization and the influence of modern education systems, English has gradually become one of the official languages and is widely taught as a second language in schools [52,53]. Prolonged language contact has resulted in extensive borrowing from English, both in vocabulary and phonological systems, creating notable similarities in phoneme distribution and speech structure. Furthermore, English, as the most resource-rich language, offers large-scale annotated corpora and well-developed pretrained models, providing a strong foundation for transfer learning. Therefore, this study selects English as the source language for building pretrained models to facilitate Tongan speech recognition.

This study employs two datasets. For English, the publicly available LibriSpeech corpus (960 h) is used for pretraining. For Tongan, the speech data were recorded in our laboratory by several professional researchers to ensure both speaker diversity and consistent recording quality. All recordings were conducted in a quiet indoor environment using a high-quality condenser microphone positioned approximately 20 cm from the speaker’s mouth. Each utterance was recorded by a single speaker without overlap to avoid multi-speaker interference. All recordings were captured in mono format, with no speaker diarization applied, as each utterance was produced by a single speaker. The sampling rate was set to 16 kHz. The transcription process was manually performed using Notepad++ and strictly aligned with the reference text to guarantee complete labeling accuracy. The recordings feature clear and standardized pronunciation, making them suitable for evaluating model performance and recognition robustness under low-resource conditions. In total, 1.44 h of Tongan speech data were obtained and divided into training, validation, and test sets. Detailed statistics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tongan corpus configuration (raw data).

As shown in the table, the Tongan dataset is relatively small in scale. Direct training on such limited data is likely to cause overfitting and reduce the model’s generalization capability. Therefore, in the subsequent experiments, the data will be appropriately augmented and expanded to reach a more reasonable scale.

4.2. Experimental Design

This study adopts the Mixformer network as the base architecture for transfer learning. The pre-trained weights are obtained from previous English speech recognition experiments that were trained on the LibriSpeech corpus [54]. The Mixformer model, containing approximately 90 million parameters, performs loss-based weighted fusion of the Conformer, Unified Conformer, and U2++ Conformer architectures to improve overall robustness. During decoding, it combines both CTC and attention mechanisms, incorporating a penalty function to dynamically optimize decoding paths, thereby achieving a balance between recognition accuracy and inference efficiency. Building on this foundation, the proposed layer-wise adaptive transfer strategy is applied to fine-tune the model, improving its adaptability and training efficiency for the Tongan language task.

To provide a clearer view of the model’s architecture and performance, Table 2 and Table 3 present the Mixformer’s core configurations, along with its training settings and recognition results on the English corpus.

Table 2.

Model architecture.

Table 3.

Parameter configuration and recognition results in English pretraining stage.

Experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU (16 GB, NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with CUDA 11.8, running on 64-bit Ubuntu 18.04. The environment was configured with Python 3.8 and PyTorch 2.1.2. Detailed parameter settings for the Tongan training stage are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parameter configuration in Tongan training stage.

In addition, standard training management techniques were employed, including early stopping based on validation loss and automatic checkpoint saving after each epoch. Furthermore, a warm-up followed by cosine-annealing learning rate scheduling was utilized to stabilize the training process and promote smoother convergence.

4.3. Performance Metrics

In speech recognition, evaluating model performance is critical. This study adopts Word Error Rate (WER) as the primary evaluation metric. WER is calculated by measuring the minimum edit distance—comprising substitutions, insertions, and deletions—between the recognized text and the reference text and dividing it by the total number of words in the reference. The formula is as follows:

Here, , , and represent the number of substitutions, deletions, and insertions, respectively, while denotes the total number of words. A lower indicates higher recognition accuracy.

In addition to recognition accuracy, decoding speed is also an important evaluation criterion. This study uses Words Per Second (WPS) to reflect the model’s real-time processing capability. The calculation formula is as follows:

represents the time required to complete an inference of speech recognition.

In addition, to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the data augmentation and partitioning strategies, this study conducts quantitative analysis from two perspectives: the similarity quality of augmented data and the class balance of the partitioned subsets.

For similarity evaluation, the proposed augmentation algorithm incorporates a DRF module to assess feature similarity between synthetic pseudo-samples and original samples. DRF filters and retains high-quality augmented samples based on a scoring mechanism, as detailed in (8).

For class balance evaluation, given that audio signal features are high-dimensional and structurally complex, making them difficult to interpret directly, this study employs the t-SNE dimensionality reduction algorithm to project the features into a two-dimensional space for intuitive visualization of data clustering. To quantitatively assess distributional divergence between subsets, a weighted total variance metric is introduced as follows:

, and denote the variances of the training, validation and test sets, respectively; , and represent the number of samples in the training, validation and test sets.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Data Augmentation Experiments

To address data scarcity and class imbalance in Tongan speech recognition, this study augments the original dataset using SRA-DRF combined with weighted stratified sampling. The effectiveness is evaluated from two perspectives: data partitioning and augmentation similarity.

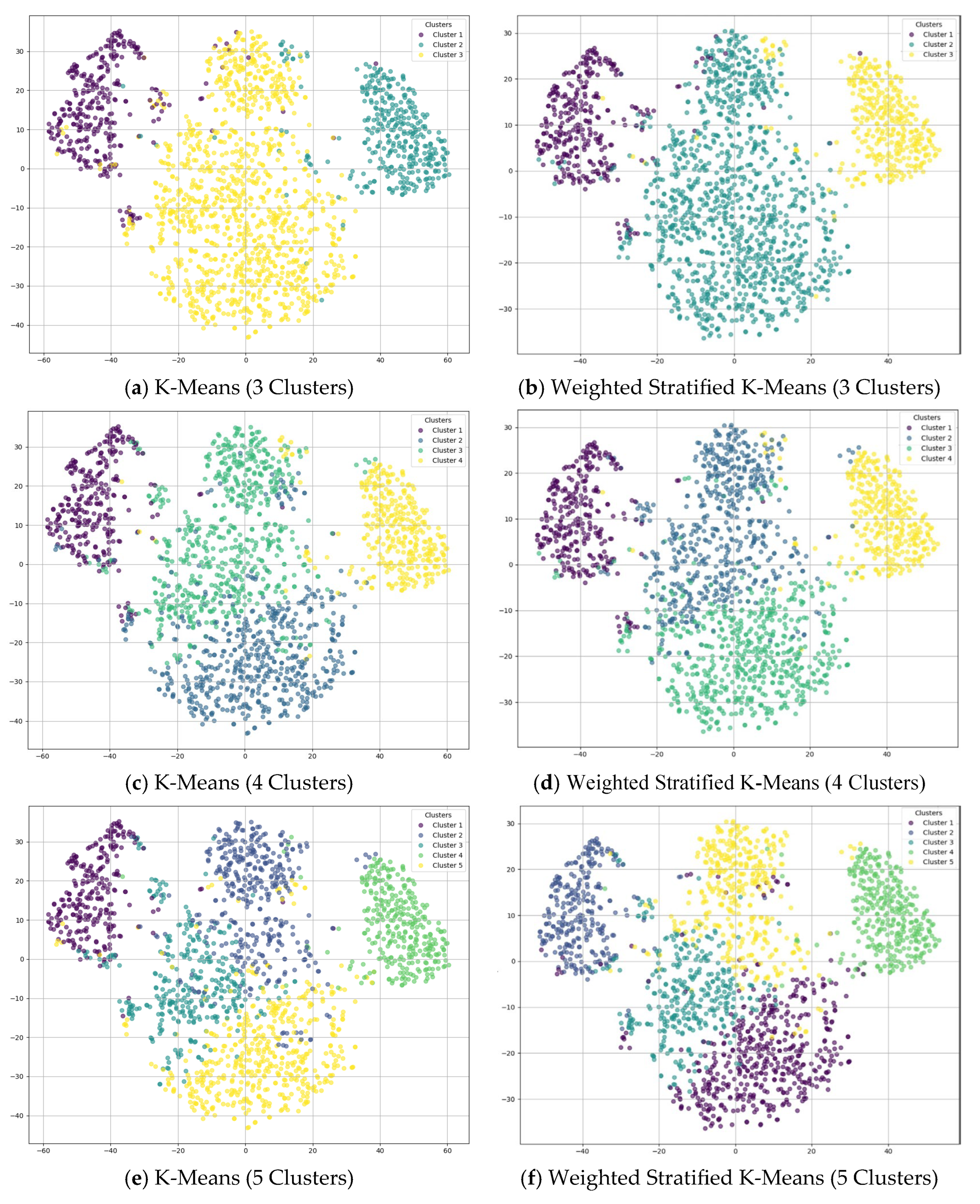

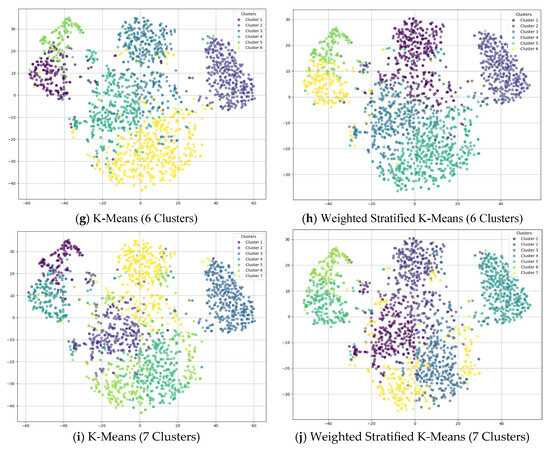

For the data partitioning experiment, given the large volume of augmented samples, qualitative analysis uses only a subset for t-SNE visualization to avoid visual clutter. It is important to note that the x- and y-axes in the t-SNE plots reflect only relative sample distribution without physical meaning; therefore, axis ticks are omitted in the corresponding figures. In contrast, quantitative analysis is performed on the full dataset to compute the total variance, ensuring comprehensive and representative evaluation. The data are clustered into 3 to 7 groups, and samples are further categorized into near, medium, and far subgroups according to their distances from cluster centers. Stratified sampling is then applied to construct the training, validation, and test sets. Finally, the proposed method is compared with the baseline approach both qualitatively and quantitatively, as shown below.

Figure 8 presents the clustering results of the traditional algorithm and the proposed method under different numbers of clusters (3–7). When the number of clusters is set to 3, the clustering is relatively coarse, making it difficult to distinguish the data effectively. As the number increases to 4 or 5, the data distribution becomes clearer, and clustering quality improves markedly. However, with 6 or 7 clusters, the boundaries become blurred and class overlap intensifies, leading to a decline in clustering performance. Comparing performance across different cluster settings, the traditional K-Means performs reasonably well with fewer clusters but exhibits severe class mixing as the number increases. In contrast, the proposed method maintains clearer separation even with higher cluster counts, alleviating the overlap issue to some extent and consistently outperforming the baseline.

Figure 8.

Comparison of clustering results.

Table 5 presents the dataset partitioning results obtained using K-Means and weighted stratified K-Means under different cluster numbers (three to seven). The experimental results indicate that although the total variance of K-Means generally decreases as the number of clusters increases, its performance becomes unstable at higher cluster counts (six or seven), particularly on the test set. In contrast, the proposed method maintains better balance even with fewer clusters and exhibits more stable variance trends as the cluster number increases, demonstrating improved consistency and uniformity in partitioning. Based on the overall evaluation, the configuration with five clusters—yielding the most balanced results—is selected for subsequent data partitioning. The final statistics are reported in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 5.

Quantitative comparison of dataset partitioning results.

Table 6.

Dataset partition statistics.

Table 7.

Final sample classification statistics.

To validate the effectiveness of the augmentation method, eight controlled experiments were conducted to examine the impact of different augmentation techniques and class sample distributions on classification accuracy. The experimental configurations and results are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Data augmentation effectiveness experiment.

In this study, the dataset consists of five categories (A, B, C, D, E), clustered by the weighted stratified sampling algorithm. In Experiment 1, data augmentation was performed using a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), which achieved a similarity of 79.60%. Experiment 2 applied traditional signal processing techniques such as speed and pitch perturbation, achieving a similarity of 88.62%. Experiment 3 integrated both approaches with the proposed augmentation algorithm, achieving the highest similarity of 90.63%. This result outperformed Experiments 1 and 2, demonstrating that the proposed method effectively enhances data quality and improves model robustness. Experiments 4–8 involved removing one category at a time from the Tongan dataset. The results show that removing any category led to a significant drop in accuracy, indicating that maintaining class balance plays a crucial role in data augmentation. Therefore, the dataset generated in Experiment 3, which achieved the highest classification accuracy, was selected for subsequent transfer learning experiments.

After data augmentation and partitioning, the final Tongan speech dataset consists of 8686 audio samples, divided into five categories: A (1946 samples), B (1820), C (1870), D (1804), and E (1846), totaling approximately 11.44 h. All audio files are stored in FLAC format and sampled at 16 kHz. The dataset distribution is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Configuration of the expanded data sample set.

In summary, the proposed data augmentation method not only expanded the corpus size but also preserved a high similarity in feature distributions between the augmented samples and the original data, confirming the effectiveness and practicality of the augmented corpus. The weighted stratified sampling strategy effectively improved class balance during dataset partitioning and enhanced the consistency across the training, validation, and test sets. Together, these two strategies enabled the development of a stable, high-quality low-resource speech dataset, providing a solid foundation for subsequent model training.

5.2. Transfer Learning Experiments

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed transfer learning strategy, this section conducts experimental validation from two perspectives: a visual analysis of the model migration process and a comparison of recognition performance after transfer.

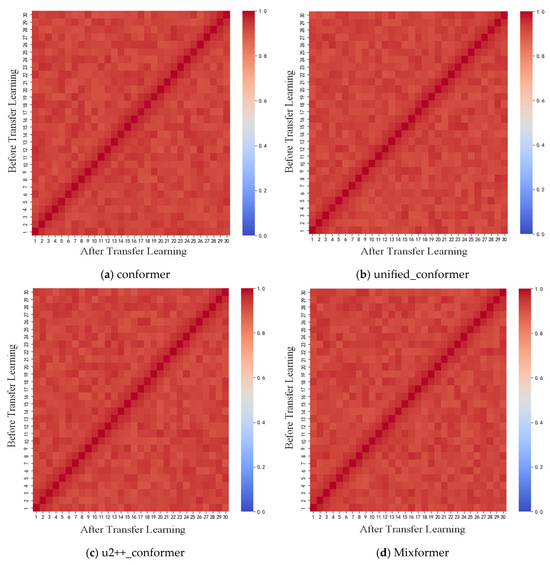

The experiment begins with a visualization-based analysis to examine structural changes in the model before and after fine-tuning. Given the complexity of the adopted architecture, it is impractical to cover all layers. To address this, a representative selection strategy is adopted: the lower layers are sampled using stratified sampling, and the last 30 upper layers are selected to align with the layer-wise unfreezing process and to observe the evolution of feature representations. The corresponding experimental results are presented below.

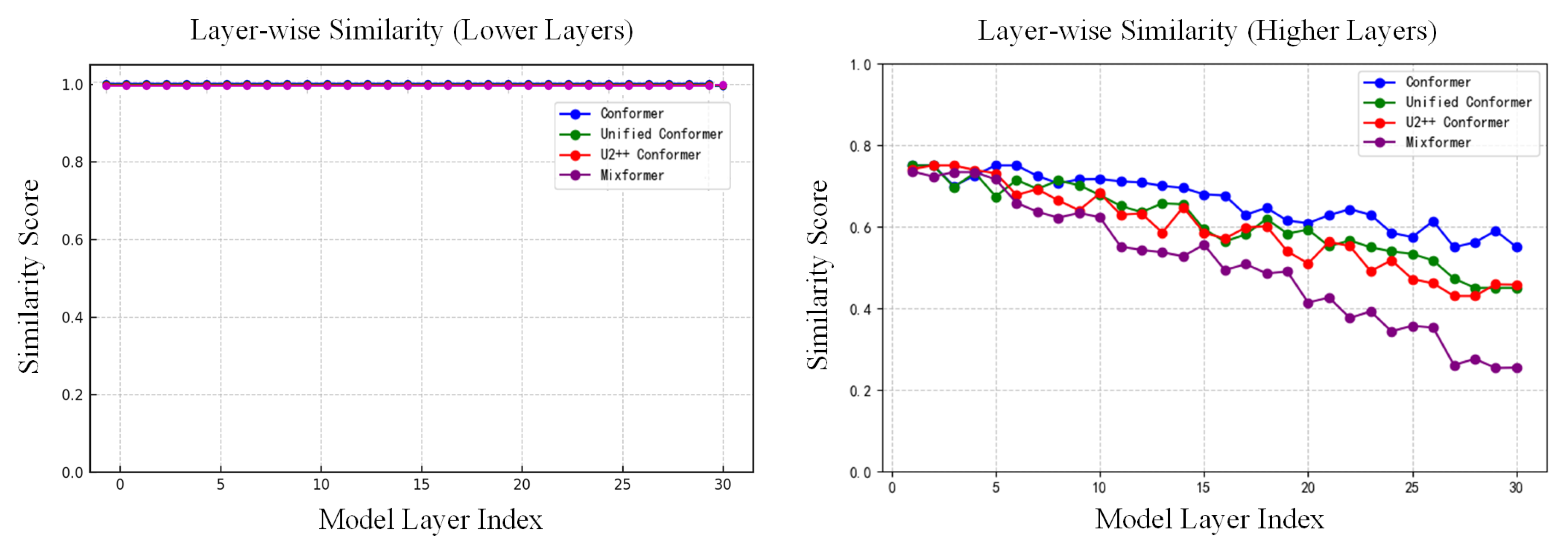

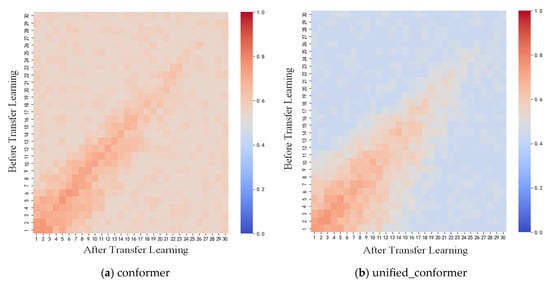

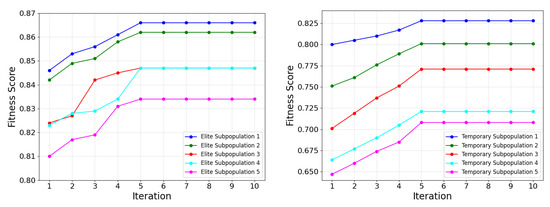

Figure 9 and Figure 10 present the CKA similarity matrices of four models before and after training, focusing on the lower and upper layers. The results show that the similarity patterns in the lower layers are highly consistent across all models, with values along the main diagonal close to 1. This suggests that lower-level features remain largely unchanged during fine-tuning and are minimally affected by parameter updates. In contrast, the upper-layer similarities gradually decrease with increasing depth, as reflected by the fading of the main diagonal. This trend suggests that parameter adjustments intensify progressively in higher layers. Such a pattern aligns well with the layer-wise unfreezing strategy discussed in Section 3.2, further confirming that higher-level representations gradually adapt to the target task, whereas lower-level structures remain stable. This demonstrates the effective implementation of the proposed transfer strategy.

Figure 9.

CKA similarity of low-level structures before and after transfer across models.

Figure 10.

CKA similarity of high-level structures before and after transfer across models.

Figure 11 quantitatively illustrates the changes in feature similarity across different layers. The similarity scores in the lower layers remain close to 1, indicating that these features remain stable during fine-tuning. In contrast, similarity in the upper layers decreases progressively with increasing depth, with the largest drop observed in the top layers, thereby confirming the effectiveness of the layer-wise unfreezing strategy. The extent of high-layer variation differs among models: Conformer exhibits the smallest change, while Unified Conformer and U2++ Conformer show more noticeable decreases. Mixformer demonstrates the most substantial drop, suggesting a more thorough adaptation of high-level features, which may enhance its potential for Tongan speech recognition tasks.

Figure 11.

Layer-wise similarity variation before and after transfer in different models.

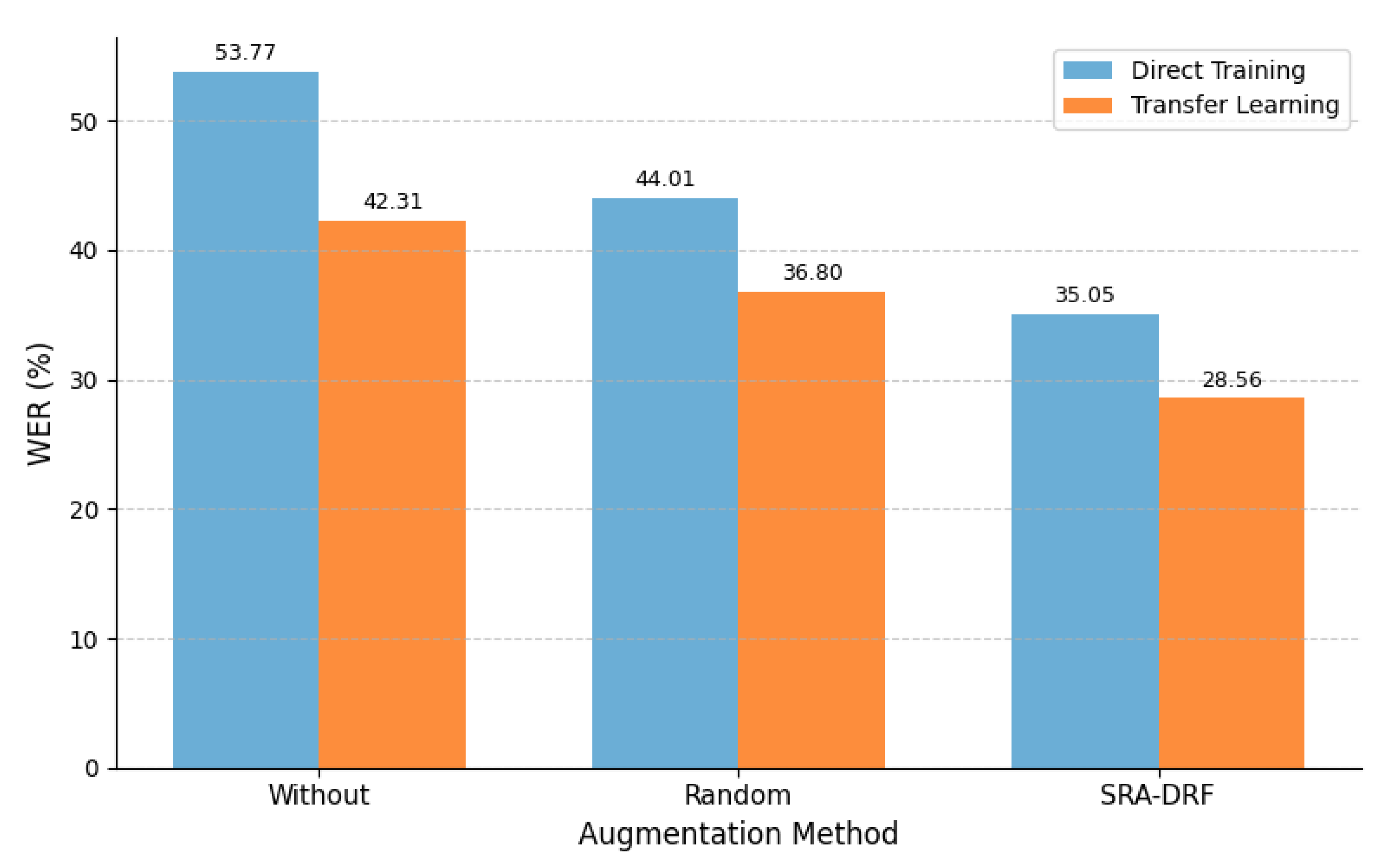

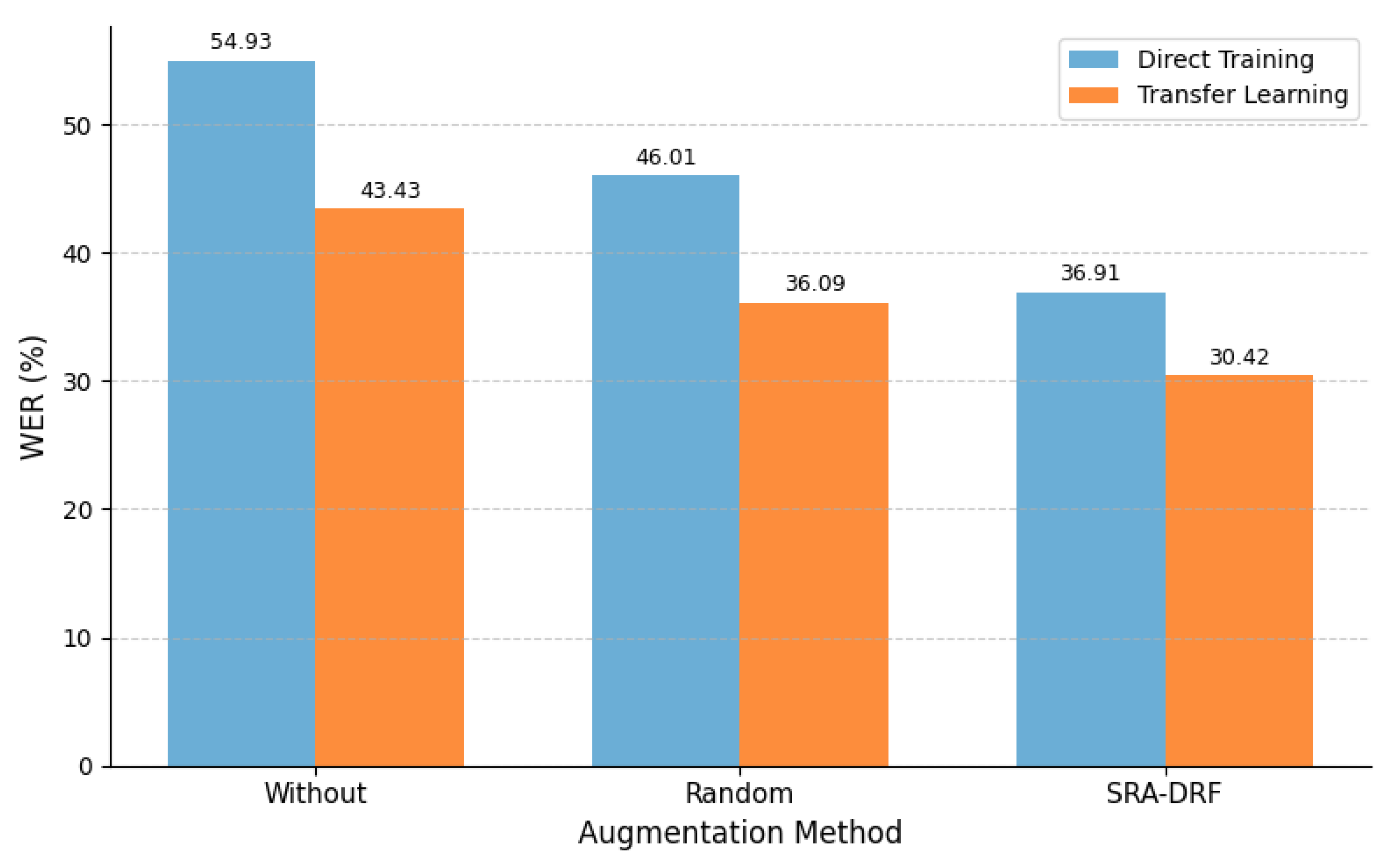

Building on the preceding visualization analysis, this section further evaluates recognition performance after transfer learning. Table 10, Figure 12 and Figure 13 summarizes the experimental results for the combinations of three data augmentation strategies (without augmentation, random augmentation, and the proposed method) and two training approaches (direct training and layer-wise transfer learning).

Table 10.

Comparison of data augmentation methods.

Figure 12.

Development set comparison of data augmentation methods.

Figure 13.

Test set comparison of data augmentation methods.

The results show that direct training without augmentation results in poor recognition accuracy. Random augmentation provides only modest and limited improvements. In contrast, the proposed method combined with layer-wise transfer markedly improves recognition accuracy while halving the required training epochs. A plausible explanation for this improvement lies in two main aspects. First, the SRA-DRF augmentation expands the training data with higher quantity and quality, avoiding invalid or overly dissimilar samples that may arise in random augmentation. Its selective mechanism guarantees that the generated audio remains acoustically consistent with the original recordings, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization ability and reducing learning bias. Second, the adopted transfer learning strategy enables the model to leverage the pretrained English representations, which share similar phonetic and acoustic characteristics with Tongan. This facilitates more efficient feature adaptation, leading to faster convergence and higher recognition accuracy. These findings highlight both the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed method in addressing data scarcity in low-resource languages, providing a promising modeling approach for Tongan speech recognition.

5.3. Dictionary Parameter Optimization Experiments

This section performs automatic optimization of the core dictionary parameter, NBPE, using the MEA-AGA, in order to determine the optimal dictionary size. The process begins with the differentiation phase to generate the initial population. The results are presented below.

Table 11 lists ten sets of NBPE parameters generated during the initial Differentiation phase, along with their corresponding WER, training time, and WPS performance metrics. The fitness scores, calculated according to (31), are used to rank these candidates The top five individuals are designated as the elite subpopulation, providing the foundation for subsequent optimization of dictionary parameters, while the remaining five are classified as temporary individuals, forming the temporary subpopulation.

Table 11.

Results of differentiation operation.

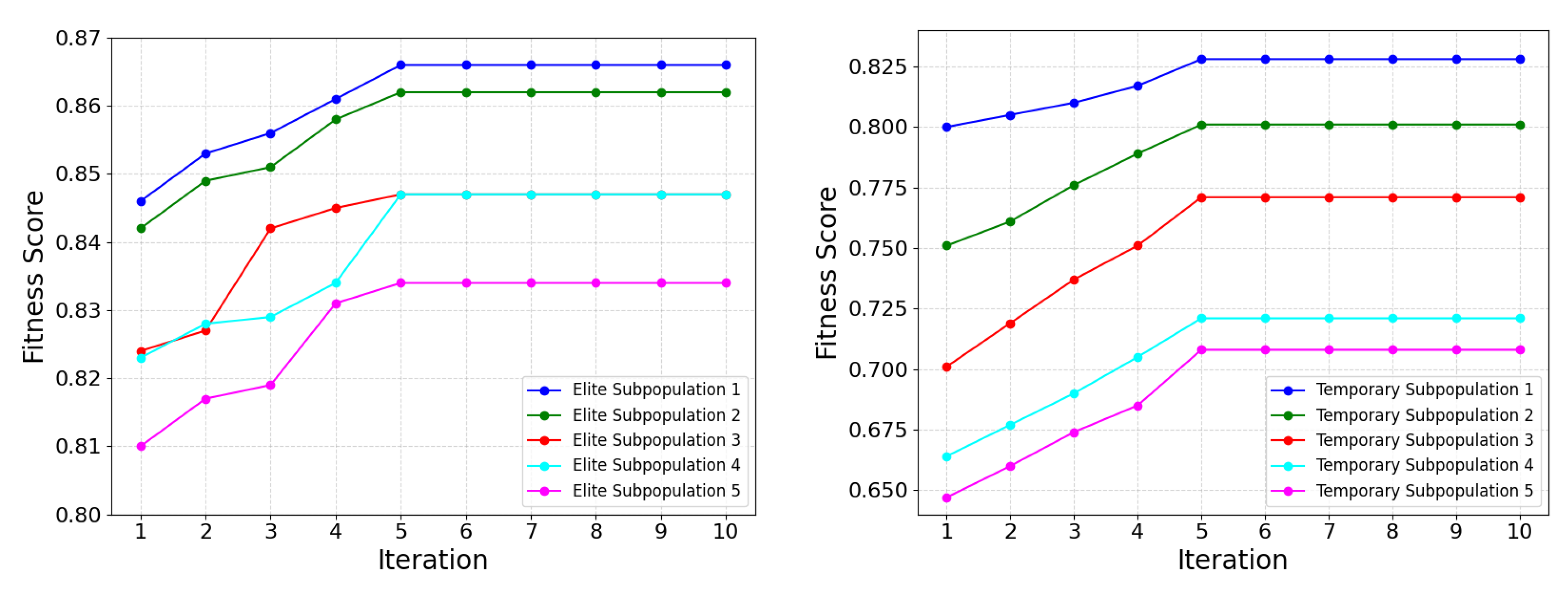

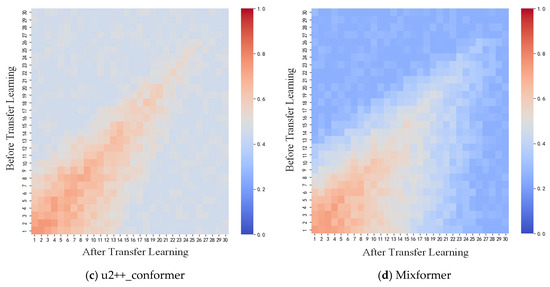

Building on this foundation, an Aggregation operation is applied to both the elite and temporary subpopulations to enable fine-grained search and improve overall optimization performance. Figure 14 illustrates the variation in fitness scores of the two subpopulations throughout the Aggregation process.

Figure 14.

Iteration process of the dominant and temporary subpopulation.

The results indicate that the MEA-AGA achieves stable performance in dictionary parameter optimization, with fitness scores steadily improving during the early stages and gradually converging in later iterations. The elite subpopulation consistently outperforms the temporary subpopulation, and the optimal solution stabilizes at a fitness value of 0.865. These findings validate the effectiveness of the algorithm. Detailed iterative results for each subpopulation are provided in Table 12 and Table 13.

Table 12.

Results of aggregation operation (dominant subpopulation).

Table 13.

Results of aggregation operation (temporary subpopulation).

Finally, the NBPE parameter was optimized using the MEA-AGA strategy. The experimental results indicate that when NBPE is set to 401, the model achieves WERs of 26.18% on the Dev set and 28.64% on the Test set, with a decoding speed of 68 WPS. These outcomes demonstrate a favorable balance between recognition accuracy and decoding efficiency, thereby validating the practical value of the proposed optimization strategy for low-resource language recognition tasks.

5.4. Comparative Analysis of Model Performance

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategies, a series of comparative experiments were conducted. The evaluation metrics included Dev-WER, Test-WER, and WPS. The results are summarized in Table 14, where “√” indicates that the corresponding strategy was applied, and “——” denotes that it was not.

Table 14.

Comparative analysis of model performance under different optimization strategy.

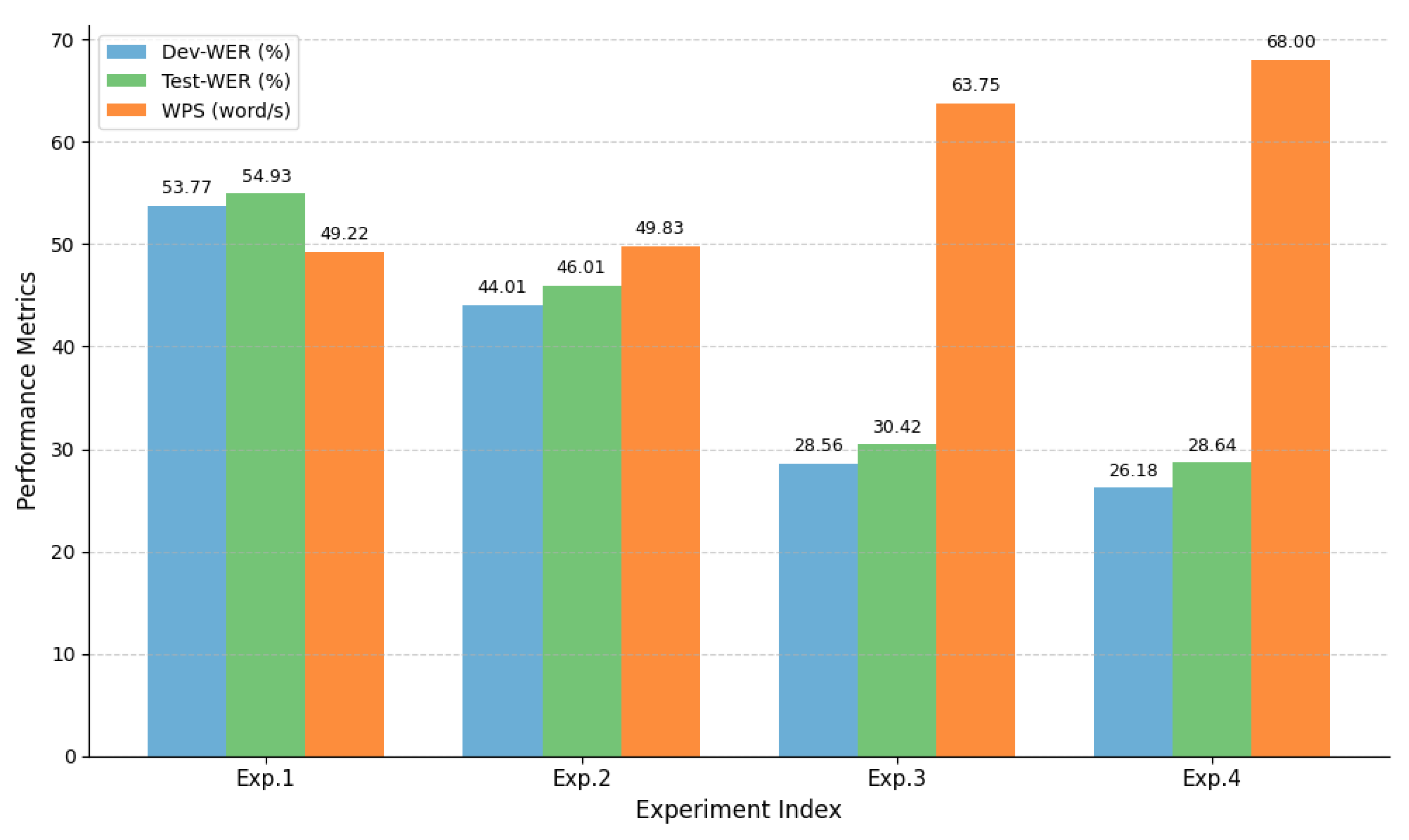

The experimental results are further visualized in Figure 15, which illustrates the performance variations under different optimization strategy combinations.

Figure 15.

Comparative analysis of model performance under different optimization strategy.

Experiment 1 serves as the baseline model without any optimization strategies. In Experiment 2, the proposed data augmentation and partitioning strategy is applied, which ensures both the quantity and quality of the expanded data while also addressing class imbalance. As a result, both dev-WER and test-WER are significantly reduced. This demonstrates its effectiveness in improving recognition accuracy and generalization, particularly for low-resource languages like Tongan. Experiment 3 additionally incorporates the layer-wise adaptive transfer learning strategy. By leveraging the similarity between English (source language) and Tongan (target language) in phonetic structures, the model achieves faster convergence and a further reduction in WER. These results highlight the adaptability and practicality of the proposed method for low-resource tasks. In Experiment 4, the NBPE value is optimized to refine vocabulary granularity, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity to represent Tongan linguistic features and improving both recognition accuracy and decoding speed.

In addition, Table 15 compares the performance of several mainstream models on the Tongan dataset. The results indicate that the proposed method surpasses the others in both recognition accuracy and inference efficiency, thereby demonstrating superior overall performance.

Table 15.

Comparative analysis of speech recognition performance of state-of-the-art models.

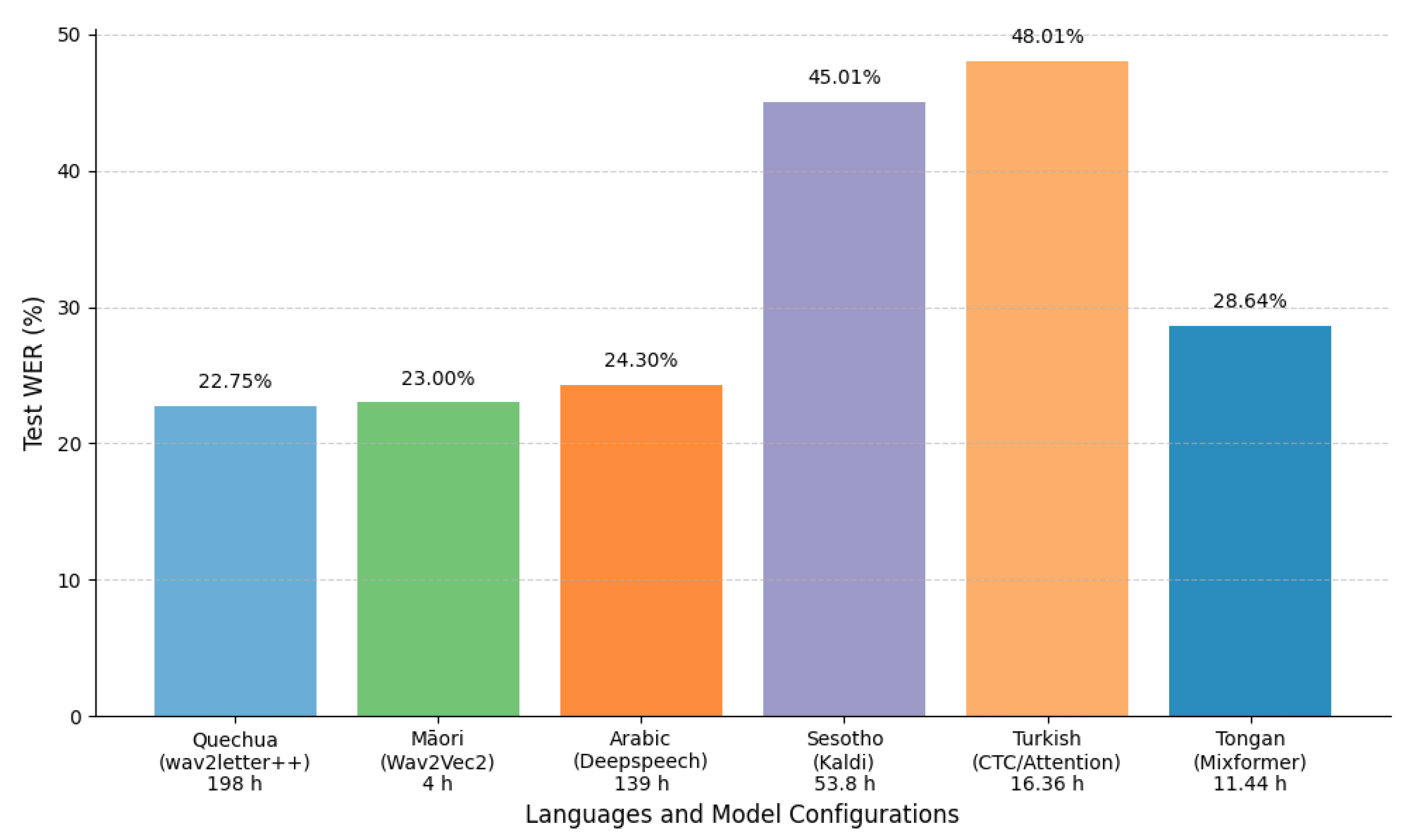

To further evaluate the overall performance of the proposed model, a horizontal comparison was conducted between the recognition results for Tongan and those reported for other low-resource languages. As shown in Table 16 and Figure 16, although the available Tongan corpus is relatively limited (11.44 h), the achieved recognition accuracy remains within a reasonable range, demonstrating performance that consistent with the dataset scale. This finding further underscores the practicality and adaptability of the proposed method in low-resource scenarios.

Table 16.

Performance comparison of speech recognition on other low-resource languages.

Figure 16.

Performance comparison of speech recognition on low-resource languages.

6. Conclusions

With the rapid development of deep learning and artificial intelligence, speech recognition technology has been widely adopted worldwide. However, most existing research has focused on resource-rich languages such as English and Chinese, while studies on low-resource languages like Tongan remain scarce. These languages typically lack systematic corpora and effective modeling approaches, leading to challenges such as data scarcity, limited model transferability, and inadequate dictionary modeling mechanisms.

To overcome these limitations, this study first constructs a pretrained model using resource-rich English corpora and then fine-tunes it on the target language, Tongan, through a layer-wise adaptive transfer learning strategy. This approach enables both efficient and accurate speech recognition. Moreover, it provides valuable theoretical and technical support for the preservation of Tongan linguistic and cultural resources, while also promoting international cultural exchange. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

(1) To address the issue of limited Tongan language data, this study proposes an SRA-DRF algorithm. By combining GAN-based synthetic data generation with traditional signal processing techniques, high-quality audio samples are produced. The effectiveness of the augmented data is validated through similarity comparison, demonstrating that the dataset size increases from 1.43 h to 11.44 h, with a similarity score of 90.63% between the augmented and original data. This effectively alleviates the problem of data scarcity. Furthermore, a weighted stratified sampling strategy is employed to achieve class-balanced partitioning, ensuring that the training, validation, and test sets maintain a complete and balanced sample distribution, thereby enabling the model to fully learn the features of each category.

(2) In the transfer learning phase, this study introduces a layer-wise adaptive strategy that preserves the low-level general features of the pretrained model while dynamically adjusting the learning rates of the higher layers according to loss values and source–target language similarity. Fine-tuning is applied primarily to the higher layers. The effectiveness and rationality of this strategy are further demonstrated through CKA similarity matrix analysis, which reveals distinct patterns of hierarchical feature adaptation.

(3) For optimizing the critical NBPE parameter in Tongan dictionary construction, this study proposes the MEA-AGA optimization algorithm. The NBPE value is optimized from an initial setting of 300 to 401. With this configuration, the optimized model achieves a Dev-WER of 26.18% and a Test-WER of 28.64% on the Tongan dataset, along with a decoding speed (WPS) of 68. Compared with the baseline model (Dev-WER 53.77%, Test-WER 54.93%, WPS 49.22), these results represent approximately 51.3% and 47.9% relative reductions in WER, and a 38.2% increase in decoding speed. These results demonstrate substantial improvements in both recognition accuracy and inference efficiency. Compared with mainstream approaches, the proposed method exhibits clear advantages and achieves performance within a reasonable accuracy range for low-resource language speech recognition.

Beyond its technical contributions, the development of speech recognition for low-resource languages such as Tongan also carries important ethical and societal significance. From a cultural perspective, it supports linguistic diversity by promoting the digital preservation and accessibility of endangered languages, helping safeguard intangible cultural heritage and enabling inclusive global communication. From an ethical standpoint, enhancing AI inclusivity helps narrow the digital divide and prevent the marginalization of smaller linguistic groups. At the societal level, improving recognition for minority languages contributes to cultural sustainability and supports education and social inclusion in multilingual regions.

7. Future Work

Although the proposed transfer strategy and parameter optimization algorithm have achieved promising results in Tongan speech recognition, several limitations remain. Future research can therefore be pursued in the following directions:

(1) Dataset Expansion: The current Tongan speech corpus remains relatively small. Although the proposed data augmentation and balanced partitioning strategies have partially alleviated data scarcity and mitigated imbalance to some extent, the corpus size and distribution are still limited compared with mainstream languages. This constraint may affect the model’s generalization performance across phonetic categories. Future work should prioritize the collection of larger and more balanced Tongan speech datasets with higher quality to further enhance model robustness and generalizability.

(2) Optimization of Transfer Strategies: Although the proposed framework effectively adapts pretrained models to low-resource speech recognition, it still relies on supervised fine-tuning. This dependency may limit adaptability when labeled data are scarce or domain variations occur. Future research could explore more flexible transfer learning paradigms to overcome these limitations. For instance, unsupervised or semi-supervised adaptation strategies could reduce reliance on annotated data, while zero-shot or few-shot learning mechanisms may enhance model generalization under extremely low-resource conditions.

(3) Broader Source Language Selection: In this study, English was selected as the source language due to its phonetic similarity to Tongan. Future research could investigate multilingual joint transfer strategies to enhance cross-lingual generalization. Moreover, given the demonstrated effectiveness of the proposed method for Tongan, its applicability to other low-resource languages deserves systematic evaluation to validate its universality and scalability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and D.J.; methodology, J.G. and Z.L.; software, Z.L. and W.Z.; validation, J.G. and D.J.; formal analysis, J.G.; investigation, Z.H. and W.Z.; resources, N.W. and R.C.; data curation, N.W. and W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, D.J.; visualization, J.G.; supervision, D.J.; project administration, D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program (Project No. 2023YFF0612100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the research is still ongoing, and early disclosure may affect subsequent work. However, the data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Jia for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this research. We also thank the students who participated in this project for their efforts and dedication, which were essential to the success of this study. Generative AI tools were used exclusively to improve the language and grammar of this manuscript. All scientific content, analyses, interpretations, and conclusions were entirely conceived, written, and verified by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Junhao Geng was employed by the company Beijing Research Institute of Automation for Machinery Industry Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Deng, L.; Hinton, G.; Kingsbury, B. New types of deep neural network learning for speech recognition and related applications: An overview. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 May 2013; pp. 8599–8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddow, B.; Bawden, R.; Barone, A.V.M.; Helcl, J.; Birch, A. Survey of Low-Resource Machine Translation. Comput. Linguist. 2022, 48, 673–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A.; Mohamed, A.; Hinton, G. Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 May 2013; pp. 6645–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Baskar, M.K.; Li, R.; Wiesner, M.; Mallidi, S.H.; Yalta, N. Multilingual Sequence-to-Sequence Speech Recognition: Architecture, Transfer Learning, and Language Modeling. In Proceedings of the IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Athens, Greece, 18–21 December 2018; pp. 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Hou, F.; Wang, R. A Novel Self-Training Approach for Low-Resource Speech Recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.05269. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhamadiyev, A.; Khujayarov, I.; Djuraev, O.; Cho, J. Automatic Speech Recognition Method Based on Deep Learning Approaches for Uzbek Language. Sensors 2022, 22, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Westhuizen, E.; Kamper, H.; Menon, R.; Quinn, J.; Niesler, T. Feature Learning for Efficient ASR-Free Keyword Spotting in Low-Resource Languages. Comput. Speech Lang. 2022, 71, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamyrbayev, O.; Oralbekova, D.; Kydyrbekova, A.; Turdalykyzy, T.; Bekarystankyzy, A. End-to-End Model Based on RNN-T for Kazakh Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI), Nagoya, Japan, 25–27 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, T.; Shi, Y.; Du, W.; Li, G.; Wang, D. M2ASR-MONGO: A Free Mongolian Speech Database and Accompanied Baselines. In Proceedings of the 2021 24th Conference of the Oriental COCOSDA International Committee for the Co-Ordination and Standardisation of Speech Databases and Assessment Techniques (O-COCOSDA), Singapore, 18–20 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oukas, N.; Zerrouki, T.; Haboussi, S.; Djettou, H. Arabic Speech Recognition Using Deep Learning and Common Voice Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), Sakheer, Bahrain, 20–21 November 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changrampadi, M.H.; Shahina, A.; Narayanan, M.B.; Khan, A.N. End-to-End Speech Recognition of Tamil Language. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2022, 32, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, V.M.; Mysore Sathyendra, N.J. Improving the Performance of Transformer-Based Low-Resource Speech Recognition for Indian Languages. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 8279–8283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Dang, J. Effective Training of End-to-End ASR Systems for Low-Resource Lhasa Dialect of Tibetan Language. In Proceedings of the 2019 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Lanzhou, China, 18–21 November 2019; pp. 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop, C.S.; Ramakrishnan, A.G. CTC-Based End-to-End ASR for the Low-Resource Sanskrit Language with Spectrogram Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2021 National Conference on Communications (NCC), Bangalore, India, 27–30 July 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.E.; Stone, P. Transfer Learning for Reinforcement Learning Domains: A Survey. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2009, 10, 1633–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Raghu, M.; Zhang, C.; Kleinberg, J.; Bengio, S. Transfusion: Understanding Transfer Learning for Medical Imaging. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32; Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, Inc.: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.; Bird, J.J.; Faria, D.R. A Study on CNN Transfer Learning for Image Classification. In Proceedings of the 18th UK Workshop on Computational Intelligence (UKCI 2018), Nottingham, UK, 5–7 September 2018; pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, R.; Li, J.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Z.; He, G.; Yan, R.; Gryllias, K. A Perspective Survey on Deep Transfer Learning for Fault Diagnosis in Industrial Scenarios: Theories, Applications and Challenges. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 167, 108487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainzinger, J.; Levow, G.-A. Fine-Tuning ASR Models for Very Low-Resource Languages: A Study on Mvskoke. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 4: Student Research Workshop), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.A.; Tabibian, S.; Veisi, H.; Mahmudi, A.; Rashid, T. End-to-End Transformer-Based Automatic Speech Recognition for Northern Kurdish: A Pioneering Approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.16330. [Google Scholar]