Abstract

Dengue is a life-threatening disease that is transmitted by mosquitoes. Dengue fever has no proper treatment. Early, proper diagnosis is essential to minimize complications and enhance outcomes in patients. This research uses a clinical and hematological dataset of dengue to assess the effectiveness of the Gradient Boosting (GB) classification model with and without feature selection. It initially employs a standalone GB model, achieving impeccable results for classification, at 100% accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall. In addition, the Bird Swarm Algorithm (BSA)-based metaheuristic technique is implemented on the GB classifier to execute wrapper-based feature selection so that features are reduced and achieve better results. The BSA-GB model yielded an accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.62%, recall of 99.24%, and precision of 100%, but it only selected five features in total. An additional test with a five-fold cross-validation was employed for better performance and model evaluation. Folds 1 and 2 showed especially good results. Although fold 2 selected only four features, it still showed high results, compared to fold 1, which selected five features. In this context, fold 2 achieved an accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.65%, recall of 99.30%, and precision of 100%. Means of hyperparameters were also calculated across folds to make a generalized GB model, which maintained 99.49% of accuracy with just three features, namely, Hemoglobin, WBC Count, and Platelet Count. To enhance transparency, counterfactual explanations were performed to analyze the misclassified cases, which indicated that minimum changes in input features modify the predictions. Also, an evaluation of the SHAP value result designated WBC Count and Platelet Count as the most important features.

1. Introduction

Dengue fever (DF) is a mosquito-borne, viral disease. Basically, DF spreads from mosquitoes to people. It can be life-threatening without proper treatment and care and is among the leading international public health concerns of the past several decades. DF disease is caused by the dengue virus (DENV) [1]. DENV has four nearly similar but different serotypes, which are DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4, and it is spread primarily by the mosquito Aedes aegypti, with Aedes albopictus being a secondary vector [1]. DF predominantly occurs in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, with the highest rate shown in urban and semi-urban environments. Even in rural areas, many people are affected by DF. Many people infected with the dengue virus may not show symptoms or only have a mild illness, but in some cases, it can cause serious and even life-threatening problems. The World Health Organization (WHO) has collected information on DF and has stated that the estimated number of dengue infections each year ranges around 100–400 million [2]. According to the WHO, the highest number of DF was recorded in 2023 across 80 nations [2]. Over 6.5 million infections and over 7300 dengue-related deaths have been documented since the start of 2023 due to continuous transmission and an unanticipated increase in dengue incidence [2]. In addition, according to the WHO, in the Americas, there were 2300 fatalities and 4.5 million cases of DF. In Asia, Bangladesh (321,000), Malaysia (111,400), Thailand (150,000), and Vietnam (369,000) reported the highest number of cases [2].

DF typically occurs as a mild or asymptomatic illness in most cases of individuals [2,3]. Recovery can take within one to two weeks. However, in a few cases, this disease can quickly progress to severe dengue fever if not treated promptly and can even lead to death. In the early stage, DF is usually detected within 4 to 10 days [2,3]. Classic symptoms of a DF patient include high-grade fever (up to 40 °C or 104 °F) [2,3]. Other symptoms include severe headache, pain behind the eyes, muscle and joint pain, nausea, vomiting, swollen lymph nodes, and skin rash [2,3]. Most importantly, secondary infections with dengue pose a much higher risk of severe disease due to antibody-dependent enhancement [4]. In particular, dangerous and critical phases of DF can occur after the fever subsides. During this stage, the symptoms of severe abdominal pain, vomiting, tachypnea, bleeding from gums, fatigue, visible blood in vomit or stool, excessive thirst, pale skin, and profound weakness are more prevalent [2,3]. If this symptom appears in any patient, immediate medical treatment should be provided. If the treatment is not provided properly, organs can fail in DF patients. Additionally, in some cases, DF-positive patients may experience weakness and fatigue for up to a week following clinical recovery, requiring supportive care.

There is currently no specific treatment for DF [2]. Thus, early detection of DF symptoms can increase the chances of quick recovery. The machine learning (ML) approach is used all over the world to identify any kind of disease as it is better for quick outcomes. In essence, by integrating historical cases with weather and population data, machine learning and deep learning enable precise forecasting.

Nirob et al. (2025) have worked on a larger multi-center dataset involving 1523 dengue-confirmed patients, incorporating detailed blood profiles [5]. They have applied a statistical test on their dataset, introducing dengue-positive patients presented with lower WBC and RBC counts and higher hemoglobin levels and monocyte percentages [5]. Mayrose et al. (2023) performed a study using a dataset, which contains peripheral blood smear (PBS) images acquired from 94 blood smear slides of different subjects (54 dengue-infected subjects and 40 normal controls) [6]. The authors used a Support Vector Machine (SVM), achieving an accuracy of 95.74% [6]. Dsilva et al. (2024) used a dataset that contains 314 digitized peripheral blood smear (PBS) images (163 dengue, 151 normal) [7]. The authors applied five YOLOv8 scaled variants on their dataset, with the YOLOv8s and YOLOv8l achieving the best mean accuracy of 99.3% across five independent experiments [7]. In addition, the SVM achieved 98.7% accuracy using 10-fold cross-validation [7]. Ho et al. (2020) employed a clinical dengue dataset (PubMed) in their study. They applied Decision Tree (DT), Deep Neural Network (DNN), and Logistic Regression (LR) and attained area-under-the-curve results of 84.6%, 85.87%, and 83.75%, respectively [8]. Iqbal et al. (2019) utilized a Dengue Outbreak (75 samples) dataset and employed the LogitBoost model, achieving an accuracy of 92%, sensitivity of 90%, and specificity of 90% [9].

2. Materials and Methods

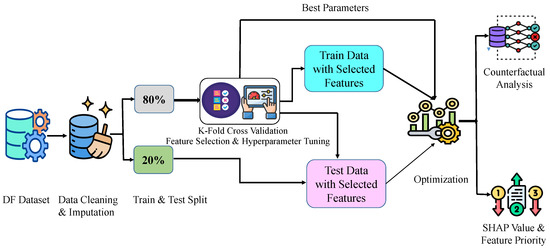

We performed a classification process to distinguish between patients with DF and those without DF using a predictive clinical and hematological dataset for dengue fever. This is a labeled dataset. This study applied supervised machine learning for classification. Primarily, the data were preprocessed and initiated with data splitting using a valid ratio, and then the classification results were analyzed. Then, the optimization algorithm was performed with cross-validation to select features and hyper-tuning for the classifier parameters. This research used the Gradient Boosting (GB) classifier and the Bird Swarm Algorithm (BSA)-based metaheuristic algorithm to select the features and hyperparameters for the classifier. Finally, SHAP was introduced to analyze the impact of each feature, and Diverse Counterfactual Explanations (DiCE) were applied to explain misclassifications. The overall approach of the working methodology is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sequential representation of methodology.

2.1. Dataset

This DF dataset was obtained from the Mendeley Data website at https://doi.org/10.17632/xrsbyjs24t.1 (accessed on 2 June 2025). The data for the DF dataset were collected from Upazila Health Complex, Kalai, Joypurhat, Bangladesh [10]. This dataset contains eight features and one target feature. Out of the eight features, one feature is categorical, and the other seven are numerical. The categorical feature is Sex, which carries Male, Female, and Child. The target feature is Final Output, which presents the DF (1)- and Non-DF (0)-affected patients. In addition, this dataset holds information on 1003 patients. Among these patients, 14 patients do not contain a class label that has been removed. However, other numerical missing feature values have been imputed using mean imputation across the entire dataset before any model training or validation. We considered up to two decimal points for the imputed values. Some information about this dataset is presented in Table 1. Furthermore, this dataset holds 320 non-DF- and 669 DF-affected patients.

Table 1.

Dataset feature summary.

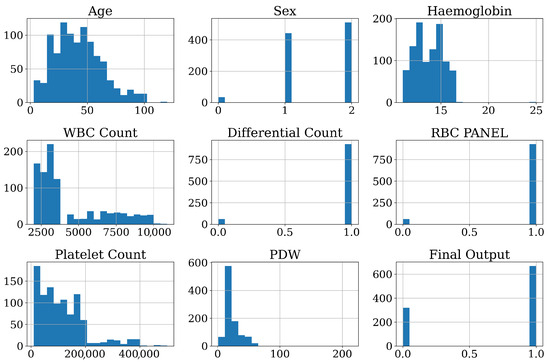

Figure 2 presents the distribution of features of the DF dataset. The age distribution shows that most patients are younger than those in the DF dataset. The sex feature, which has been encoded, shows that male (2) is more prevalent for this dataset. Hemoglobin levels are normally distributed, with most values centered around the expected physiological range. The white blood cell (WBC) count exhibits a right-skewed distribution, suggesting that many patients have lower WBC counts, which aligns with typical dengue symptoms. The differential count and RBC panel features look like binary or categorical types and display distinct separations in values. The platelet count is a key factor for DF. Platelet Distribution Width (PDW) is right-skewed, specifying significant variability in platelet size among all patients. Lastly, the final output is the target feature, which contains a binary output. The distribution of target features is relatively balanced.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of distribution of features.

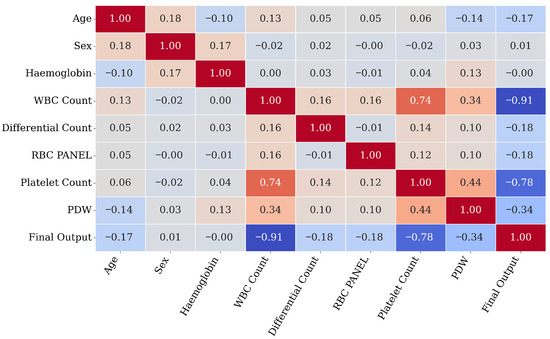

Figure 3 illustrates the correlation matrix heatmap explaining the relationship between two clinical features. Notably, platelet count and WBC count exhibit a strong correlation with the target feature. This correlation suggests their importance in predicting dengue cases. In addition, PDW also shows a moderate correlation with the target feature. Hemoglobin and Age display a weak correlation. Overall, the heatmap focuses on platelet count and WBC count as key predictive features in the DF dataset.

Figure 3.

Representation of correlation matrix.

2.2. Classification Model

In this research, a GB classifier is used, which is an ML algorithm especially used for classification tasks. GB is an ensemble method, which means it builds a strong model by adding the predictions of many weak models—typically Decision Trees [11]. GB classifier uses an iterative ensemble construction procedure whereby a further tree in the ensemble is trained to minimize the error of the previous ensemble [11]. The algorithm optimizes a loss function, usually logarithmic loss, using gradient descent, thus refining leaf node predictions [11]. Largely in comparison to other methods of machine learning, the GB classifier has been found to possess significant improvements with regard to the analysis of complex data, its ability to take into account non-linear relationships, and its propensity to reach high prediction accuracy.

For this research, the number of estimators, the learning rate, the maximum depth, and the minimum sample split hyperparameters are used for the GB classifier. The boundary condition is applied for the number of estimators: 100 to 300, learning rate: 0.001 to 0.2, etc. All hyperparameters’ ranges and types are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Boundary conditions for GB classifier hyperparameters.

2.3. Feature Selection Algorithm

Feature selection (FS) is the method of finding and extracting a pertinent subset of features from an original dataset [12]. In most datasets, not all features contribute equally to increase model performance. FS plays a crucial role in selecting the most important features. FS algorithms are categorized into three main types: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods [12]. Metaheuristic algorithms fall under the wrapper category [12]. Metaheuristic-based BSA has been used in this research to find the most prominent features and hyperparameters for the classifier.

The BSA swarm intelligence-based metaheuristic optimization technique was motivated by the natural foraging, vigilance, and flight behaviors seen in bird communities [13]. In the context of FS, BSA is a wrapper method. BSA identifies the most crucial feature sets that correlate with the output. BSA was first proposed by Xian-Bing Meng, X.Z. Gao, Lihua Lu, Yu Liu, and Hengzhen Zhang in 2016 [13].

The BSA emulates three core actions of birds: foraging, vigilance, and flight. Denote by the location of the the i-th bird in the j-th dimension at iteration t.

- (1)

- Foraging behavior:

In each iteration, each bird updates its position with the best of its own and the global best position of the swarm:

where C and S are cognitive and social coefficients.

- (2)

- Vigilance behavior:

If a bird does not forage, it moves towards the swarm center while considering competition with others:

where is the average swarm position in dimension j, is a randomly chosen bird , and are positive constants.

- (3)

- Flight behavior:

Birds periodically fly to new sites. The swarm is divided into producers and scroungers:

where is a Gaussian random number, is the following coefficient, and denotes the position of a producer.

In our study, BSA was employed to optimize the hyperparameters of GB classifier and feature selection purpose. To ensure reproducibility, the optimization seed is fixed at 1, with 30 epochs and a population size of 30. The random state is set to 42. The optimization search space includes four hyperparameters and a binary feature selection vector that represents all candidate features in the dataset. The population is randomly initialized within the defined limits. The goal of the optimization is to maximize the F1-score on the training set. Convergence is defined as either completing 30 epochs or stabilizing the global best fitness value.

2.4. Evaluation Techniques

This section outlines traditional evaluation standards for measuring the performance of the model through standard classification metrics: Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, and Recall, all obtained from the confusion matrix. Furthermore, the confusion matrix (CM) acts as a key instrument in this context. It consists of four categories determined by the predicted and actual classes. These four categories are as follows:

- True Positive (TP): Accurately identified as the positive class.

- False Positive (FP): Incorrectly identified as the positive class.

- True Negative (TN): Accurately identified as the negative class.

- False Negative (FN): Incorrectly identified as the negative class.

The metrics for classification are computed using the following mathematical formulas:

2.5. DiCE

DiCE is a counterfactual (CF)-type explanation method that generates “what-if” scenarios for machine learning models, explaining how input features would need to change to alter the outcome [14]. DiCE focuses on producing multiple and diverse sets of CFs, allowing users to explore different possibilities to achieve a desired outcome [14]. Additionally, DiCE facilitates the creation of various CF explanations and offers adjustable parameters that control the diversity and closeness of these explanations to the original input [14]. The objective of optimization for DiCE is defined in Equation (9), wherein denotes the set of k counterfactuals generated for a particular input x:

In this method, the term indicates the classification loss, steering each counterfactual toward the desired target class y. The proximity component restricts the creation of counterfactuals that stray too far from the original instance x, thereby maintaining realism. Finally, employs Determinantal Point Processes (DPPs) to enhance the diversity among the generated counterfactuals, ensuring the resulting set offers several unique and practical alternatives. The hyperparameters and control the trade-off between proximity and diversity.

2.6. Shap Method

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a great game-theory-based approach to explaining the prediction of machine learning models [15]. It assigns a contribution value to each feature for a specific prediction based on Shapley values [16]. SHAP is coherent and locally accurate, i.e., SHAP values sum up to the model prediction. It provides information about global feature importance and contribution to individual predictions. SHAP is model-agnostic and is being extensively utilized for explainable AI, particularly for complex models such as Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, Random Forest, and Neural Networks [17].

3. Results

In this research, the result section has been segregated into five subsections: cross-validation performance of multiple baseline classifier, cross-validation performance of metaheuristic-based BSA technique feature selection and model tuning, performance with mean optimized hyperparameters of GB, counterfactual analysis, and SHAP analysis. This research focuses on these three subsections and properly analyzed the results. Furthermore, using the GB classifier without selecting features, classification performance was evaluated. In addition, before using K-fold cross-validation, the metaheuristic-based BSA technique was applied. Then, the classification metrics and selected features were observed.

The GB classifier was applied without feature selection techniques and was used on the DF dataset. The model classified the dataset with perfect accuracy (Acc.) score, a perfect precision (Pre.) score, a perfect recall (Rec.) score, and a perfect F1-score (all of which were 100%). The results obtained in the following indicate that the classifier made no false positives or false negatives when classifying the actual classes of the DF dataset. In addition, the metaheuristic-based BSA technique was applied before using K-fold cross-validation. In this case, the model achieved a near-perfect accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.62%, recall of 99.24%, and an outstanding precision score of 100%. These results demonstrate the model’s performance, robustness, and reliability. Age, Hemoglobin, WBC Count, RBC PANEL, and Platelet Count features were selected in this case. Table 3 presents the performance of the models (with and without feature selection) without cross-validation.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of GB classifier and without cross-validation.

3.1. Cross-Validation Performance of Multiple Baseline Classifiers

Initially, we examined the multiple baseline classifiers with default settings through 5-fold cross-validation. Table 4 presents the average results of various baselines and well-known classifiers, including GB classifier. Most classifiers, such as XGBoost, CatBoost, AdaBoost, Extra Tree, Gradient Boosting, and LightGBM, reached a mean test accuracy of 99.90% using all eight features. Random Forest and Decision Tree achieved mean test accuracies of 99.80% and 99.70%, respectively. Logistic Regression and Support Vector Machine showed comparatively lower mean test accuracy scores of 98.89% and 98.38%, respectively.

Table 4.

Mean results of multiple baseline (with default settings) classifier models through 5-fold cross-validation.

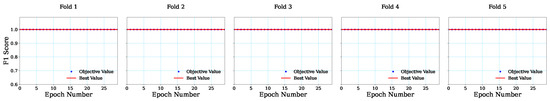

3.2. Cross-Validation Performance of Optimized Model

This research applied a five-fold cross-validation strategy to evaluate the performance of the GB classifier using the metaheuristic-based BSA technique. In this case, traditional cross-validation is used, and 5-fold cross-validation techniques are attained in this research. For each fold, the train and test are followed by the traditional cross-validation rule. Each fold found the best hyperparameters for the GB classifier. All five folds successfully achieved an F1-score value of 1 as the cost function, as illustrated in Figure 4. The figures demonstrate the fitness evolution by F1-score over 30 epochs for each fold. In addition, each fold exhibited stable fitness without any variation in the F1-score for the feature selection process.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of cost function for each fold.

In fold 1, the GB classifier achieved 123 estimators, a learning rate of 0.026290649684422046, a maximum depth of 3, and a minimum sample leaf value of 0.11270886918815179, respectively. The selected features were Age, Hemoglobin, WBC Count, RBC PANEL, and Platelet Count. Fold 2 achieved 272 estimators, a learning rate of 0.10946381155170341, a maximum depth of 7, and a minimum leaf sample value of 0.17277171739483901, respectively, for the GB classifier. In fold 3, the following hyperparameters were selected by BSA for the GB classifier: 273 estimators, a learning rate of 0.11098454855482953, a maximum depth of 7, and a minimum sample leaf value of 0.17367334962437836. In fold 4, the following hyperparameters were set for the GB classifier: the number of estimators was 276, the learning rate was 0.1115327873312052, the maximum depth was 7, and the minimum sample leaf value was 0.17389236160325644. Lastly, in fold 5, the number of estimators was 274, the learning rate was 0.11083835916758633, the maximum depth was 7, and the minimum sample leaf value was 0.17371313028572308. Each fold from folds 2 to 5 selected Age, WBC Count, RBC PANEL, and Platelet Count as their features, and all the information is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

GB classifier hyperparameters and selected features per fold.

Additionally, this research was evaluated using classification metrics performance (Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, and Recall) on both the training and test cases for each fold, which are represented in Table 6. For each fold, the GB classifier achieved perfect training scores for accuracy, F1, precision, and recall. These results strongly suggest that the training data fit the GB classifier model perfectly without any classification errors. Further, the evaluation of test data revealed the performance variability of the GB classifier, highlighting the model’s effectiveness.

Table 6.

Model performance metrics per fold.

Folds 1, 2, and 4 achieved test accuracies of 99.49%, indicating that nearly all test instances were correctly classified, whereas folds 3 and 5 performed well but slightly lower than other folds, achieving accuracy scores of 98.99% and 99.48%, respectively. In addition, the model achieved an F1-score of 99.62% and a perfect precision of 100%, indicating no false positives, while fold 1 achieved a recall of 99.24%. In fold 2, the classification model obtained an F1-score, precision, and recall of 99.23%. In fold 4, the model achieved an F1-score of 99.61% and a precision of 99.22%. Notably, the recall score achieved 100%, which indicates that the model identified all actual positive classes predicted correctly. In fold 5, the F1-score reached a near-perfect score of 99.61%, as well as a precision of 98.55% and a recall of 99.27%. These results highlight the GB model’s effectiveness and capability. Finally, the mean cross-validation performance result is displayed in the last row, in which a mean accuracy of 99.39%, mean F1-score of 99.40%, mean precision of 99.26%, and mean recall of 99.55% were obtained.

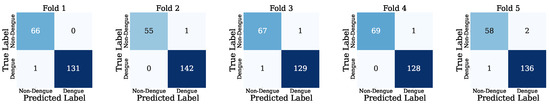

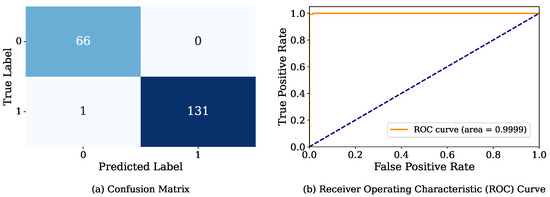

Figure 5 presents the confusion matrix for each fold. Fold 1 demonstrates that only one instance gave the wrong result. In this case, the actual class of this instance is DF, but the model incorrectly predicted it as Non-Dengue. In folds 2 and 4, each fold has one instance that was incorrectly predicted, whose actual class is Non-Dengue, but the model predicted it as Dengue. The GB model incorrectly predicted two instances in fold 3. In this case, one instance was actually class DF but shows Non-DF. In addition, another instance was actually class Non-DF, but the model predicted it as DF. Finally, in fold 5, the model incorrectly predicted three instances; two instances’ actual classes are DF, but the model wrongly predicted them as Non-DF, and the other instance was actually class Non-DF, but the model incorrectly defined it as DF.

Figure 5.

Visual presentation of each fold confusion matrix.

Figure 6 visually represents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve for each fold. The ROC has provided a graphical evaluation of a model’s classification performance by plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate. In this study, the ROC curves of fold 1 and fold 3 achieved an area-under-the-curve (AUC) score of 0.9999, indicating an almost perfect separability between the positive and negative classes. Meanwhile, folds 2 and 4 obtained an AUC of 1.0000, representing perfect separability. Fold 5 achieved the lowest AUC among all folds, with a value of 0.9996, which also indicates almost perfect separability between the positive and negative classes. The general results indicate the robustness and reliability of the GB classifier model.

Figure 6.

Fold-wise ROC curve visualization.

3.3. Performance with Mean Optimized Hyperparameters of GB

In this subsection, the average values of the hyperparameters n_estimators, learning_rate, max_depth, and min_samples_split are obtained from all five folds. The average hyperparameter values are demonstrated in Table 7. In this research, the average hyperparameter values are used in a metaheuristic-based BSA technique to select the best features and evaluate classification metrics.

Table 7.

Average hyperparameter values.

The metaheuristic-based BSA technique involved selecting three features, which are Hemoglobin, WBC Count, and Platelet Count. We have already observed that in each fold, these WBC Count and Platelet Count features are common. In this context, this technique also found that these two features are the most important and achieved a promising result. In this case, the model achieved training accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall scores of 100%. Furthermore, the model attained a test accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.62%, recall of 99.24%, and a precision of 100%, representing no false positives. The overall results are recorded in Table 8.

Table 8.

Model performance using average optimized hyperparameters.

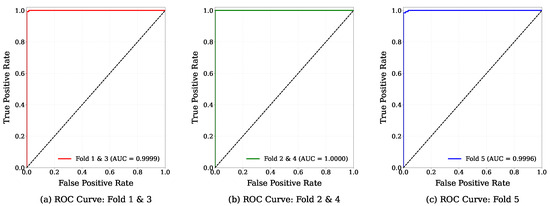

In addition, Figure 7 presents the confusion matrix and ROC curve. In this case, the confusion matrix shows only one incorrectly predicted instance. The actual class of this instance is DF, but the model predicted it as Non-DF. In addition, the ROC achieved an AUC of 0.9999, which means close-to-perfect separability between the positive and negative classes.

Figure 7.

Visual illustration of confusion matrix and ROC curve for mean optimized hyperparameters of GB.

3.4. Counterfactual Analysis

Table 9 shows misclassified instances across five cross-validation folds. In this context, the index 397 of the DF dataset is misclassified in fold 1. Fold 2 has a misclassified index of 926; the indices of 71 and 440 are misclassified in fold 3. In fold 4, only one misclassification is observed at index 312. Lastly, fold 5 exhibits comparatively higher misclassification with indexes 790, 861, and 960.

Table 9.

Misclassification results per fold.

Table 10 presents the DiCE analysis on the misclassified index. For index 397, this instance shows a meaningful increase in WBC Count from 2200 to 10,743.3, changing the actual class DF (1) to Non-DF (0).

Table 10.

DiCE analysis on misclassification instances.

For index 926, the WBC Count level significantly decreased from 8600 to 2864.9, and the actual output was switched from Non-DF (0) to DF (1).

For index 71, WBC Count has an actual value of 4338.03 and the class is DF (1), but after CF, the value of WBC Count is 10,743.3 and the new class is Non-DF (0). In addition, the value of WBC count decreased from 7300 to 2864.9, changing the actual class Non-DF (0) to the new class DF (1).

For index 312, WBC Count and Platelet Count changed. In this context, the WBC Count value significantly changed from 4338.03 to 3737.7, while the Platelet Count value changed from 150,000 to 105,669.1, altering the output class Non-DF (0) to DF (1).

The WBC Count value notably increased from 3400 to 10,765.2 in index 2, switching the actual class DF (1) to the new class Non-DF (0). In addition, the index of 861 changed the Platelet Count value from 190,000 to 35,224.6, producing a new output class from Non-DF (0) to DF (1). Finally, for index 960, WBC Count and Platelet Count changed their value and generated a new outcome. In this context, the value of WBC Count slightly changed, while the Plate Count value remarkably decreased from 233,000 to 78,641.2, creating a new class DF (1) from the actual class Non-DF (0).

Table 11 provides the DiCE interpretation on correctly classified instances. In this case, we have analyzed two correctly classified instances (1 and 1000). For index 1, WBC Count value increased from 3000.0 to 10,743.3, altering the actual class DF (1) to the new class Non-DF (0). In addition, for index 1000, WBC Count and Platelet Count values changed, switching the actual class Non-DF (0) to the predicted new class DF (0).

Table 11.

DiCE analysis on correctly classified instances.

3.5. SHAP Analysis

In our study, we used SHAP version 0.48.0. SHAP values were computed using SHAP’s TreeExplainer. SHAP values were calculated only on the held-out test dataset. This approach prevents any information from leaking in from the training data and also ensures an unbiased estimate of feature contributions.

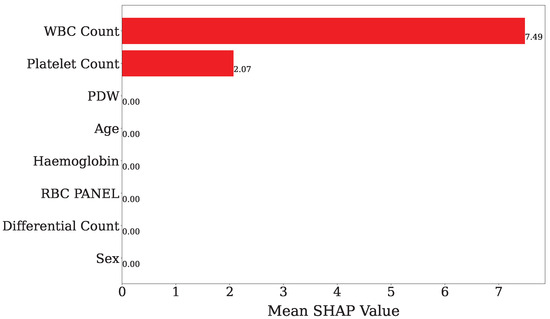

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of the features according to the mean SHAP value. This value was obtained using only the GB classifier. In this case, WBC Count has the highest SHAP value of 7.49, while the Platelet Count holds second position, at 2.07. Therefore, WBC Count and Platelet Count are the most important features among all features, whereas other features indicate that the SHAP values are not visible, which means they are less important features.

Figure 8.

Presentation of features’ mean SHAP value using only GB classifier model. The x-axis shows the average SHAP value, which indicates how much each feature influences the outcome. The y-axis lists the features in order of their importance.

4. Discussion

Table 12 shows the comparison of various dengue-related results with our research outcomes on the DF dataset. In this study, we have compared our work with the image-based dataset, which is not directly comparable with our tabular dataset. The dataset used in this study is relatively underexplored in previous studies. For this reason, we could not find enough related work concerning this dataset to compare our work. We have observed that Nirob et al. (2025) worked on a dengue dataset and performed a T-test and Z-test, with the tests conveying an important result, that is, WBC and RBC counts are influential for dengue-positive patients [5]. Mayrose et al. (2023) performed on a PBS-image dataset, achieving an accuracy of 95.74% using SVM [6]. In addition, Dsilva et al. (2024) used an SVM (10-fold cross-validation) and YOLOv8 on the PBS-image dataset, achieving an accuracy of 98.7% and 99.3%, respectively [7]. Ho et al. (2020) used a clinical dengue dataset, to which DT, DNN, and LR models were applied, achieving an AUC of 84.6%, 85.87%, and 83.75%, respectively [8]. Iqbal et al. (2019) performed a study on a dataset of 75 outbreak samples and used the LogitBoost model, achieving a model an accuracy of 92%, sensitivity of 90%, and specificity of 90%, respectively [9]. Nonetheless, none of the earlier studies are directly comparable to our research due to differences in the datasets. In this study, we utilized the Dengue Fever dataset, which was recently published.

Table 12.

Comparison with various dengue-based works and our work results on a dengue dataset.

In this study, we used a clinical and hematological dengue dataset. Firstly, we applied only the GB classifier, obtaining the best accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall results, and all these results are 100%. For better analysis and to reduce the number of features, we applied the GB classifier with a metaheuristic-based BSA algorithm, achieving an accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.62%, recall of 99.24%, and an outstanding precision score of 100%. In this case, the BSA model selected five among the eight features. For better evaluation and to reduce the features, we performed a five-fold cross-validation strategy, in which both folds 1 and 2 gave better results, with fold 1 selecting five features, and fold 2 selecting 4 features. From the feature selection perspective, we found that fold 2 achieved a better result, obtaining an accuracy of 99.49%, indicating the model’s superior performance and accuracy. The F1-score result was 99.65%, which shows the balance between performance and reliability. The precision score was 99.30%, which indicates how reliable the model is when it predicts positive cases. Finally, recall was 100%, which indicates how good the GB model is at finding all actual cases.

In addition, the mean values of the hyperparameters n_estimators, learning_rate, max_depth, and min_samples_split were used in the GB classifier and were obtained from all five folds. In this case, the model employed an accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.62%, recall of 99.24%, and precision of 100%. In this context, BSA selected three features, Hemoglobin, WBC Count, and Platelet Count, which suggests that a minimal feature subset can yield optimal outcomes.

We analyzed the misclassified results using counterfactual explanations, which mainly describe the small changes in input features of switching the previous class. In addition, we analyzed SHAP values, which indicate that the WBC Count and Platelet Count are important features among all features. Riffat et al. reported that dengue-infected patients mostly had low platelet counts [18]. Another study found a significant association between the WBC count and the risk of developing a severe form of dengue [19]. We can conclude that our findings support these observations because WBC Count and Platelet Count are associated with dengue fever.

Our proposed models demonstrate improved performance while achieving substantial feature reduction. However, one limitation of this study is the size of the dataset. Additionally, there is no publicly available dataset with a similar set of features, which has prevented us from validating our model on external data. In the future, if a comparable dataset becomes available, we intend to evaluate our model on it to further assess its generalizability.

5. Conclusions

Dengue fever (DF), also known as breakbone fever, is one of the most common diseases transmitted by the Aedes mosquito. In reality, this fever has no specific treatment, but early detection and supportive care can save lives. This study used a clinical and hematological dengue dataset to check how the Gradient Boosting (GB) classifier works with and without using feature selection. First, the standalone GB model achieved perfect classification performance—reaching 100% in accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall. A Bird Swarm Algorithm (BSA)-based metaheuristic was used to select features to improve interpretability and reduce the computational complexity of a model. The BSA-GB framework returned very competitive results with an accuracy of 99.49%, F1-score of 99.62%, recall of 99.24%, and precision of 100%, and reduced the number of features to five out of the total eight features.

Our method was later tested using five-fold cross-validation, the results of which proved the reliability of the model, with the best results being achieved in fold 1 and fold 2. Importantly, fold 2 chose only four features, but its performance was rather high, demonstrating its effectiveness. In addition, the performance values remained high despite the reduced number of features, and this indicated that the GB model was robust enough even with average hyperparameter values that used all the folds. Specifically, three major characteristics, namely, Hemoglobin, WBC Count, and Platelet Count, were enough to keep the classification performance virtually perfect.

Counterfactual explanations were used to offer a deeper insight into how the model makes decisions by indicating small inputs that would alter the prediction. Moreover, SHAP analysis noted that WBC Count and Platelet Count played a major role, and therefore, they are crucial in clinical diagnostics. As a whole, the suggested BSA-GB model is a dependable, comprehensible, and effective method of classifying dengue on fewer but significant features.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D., P.S., J.-J.T. and A.-A.N.; Formal analysis, P.D. and P.S.; Investigation, P.D., P.S. and A.-A.N.; Methodology, P.D., P.S., J.-J.T. and A.-A.N.; Resources, P.D.; Software, P.D. and P.S.; Supervision, J.-J.T. and A.-A.N.; Validation, P.D., P.S., J.-J.T. and A.-A.N.; Visualization, P.D., P.S., J.-J.T. and A.-A.N.; Writing—original draft, P.D.; Writing—review and editing, P.S., J.-J.T. and A.-A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed from the following URL: https://doi.org/10.17632/xrsbyjs24t.1 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

We utilized some of the large Language Models, such as ChatGPT-V4.0 and DeepSeek-V3.1, accessed on 15 September 2025, to enhance sentence structure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guzman, M.G.; Halstead, S.B.; Artsob, H.; Buchy, P.; Farrar, J.; Gubler, D.J.; Hunsperger, E.; Kroeger, A.; Margolis, H.S.; Martínez, E.; et al. Dengue: A continuing global threat. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8 (Suppl. S12), S7–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dengue and Severe Dengue. WHO Fact Sheets. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Guzman, M.G.; Harris, E. Dengue. Lancet 2015, 385, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martina, B.E.E.; Koraka, P.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Dengue virus pathogenesis: An integrated view. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirob, M.A.S.; Siam, A.F.K.; Bishshash, P.; Assaduzzaman, M.; Haque, M.A.; Mahmud, A. A comprehensive hematological dataset for dengue incidence in Bangladesh. Data Brief 2025, 60, 111664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayrose, H.; Bairy, G.M.; Sampathila, N.; Belurkar, S.; Saravu, K. Machine learning-based detection of dengue from blood smear images utilizing platelet and lymphocyte characteristics. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dsilva, L.R.; Tantri, S.H.; Sampathila, N.; Mayrose, H.; Bairy, G.M.; Belurkar, S.; Saravu, K.; Chadaga, K.; Hafeez-Baig, A. Wavelet scattering-and object detection-based computer vision for identifying dengue from peripheral blood microscopy. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2024, 34, e23020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-S.; Weng, T.-C.; Wang, J.-D.; Han, H.-C.; Cheng, H.-C.; Yang, C.-C.; Yu, C.-H.; Liu, Y.-J.; Hu, C.H.; Huang, C.-Y.; et al. Comparing machine learning with case-control models to identify confirmed dengue cases. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Islam, M. Machine learning for dengue outbreak prediction: A performance evaluation of different prominent classifiers. Informatica 2019, 43, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, O.; Mahmud, A. A benchmark dataset for analyzing hematological responses to dengue fever in Bangladesh. Data Brief 2024, 57, 111030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, B.; Anuradha, J. A review of feature selection and its methods. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2019, 19, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-B.; Gao, X.Z.; Lu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. A new bio-inspired optimisation algorithm: Bird Swarm Algorithm. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2016, 28, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothilal, R.K.; Sharma, A.; Tan, C. Explaining machine learning classifiers through diverse counterfactual explanations. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Spain, 27–30 January 2020; pp. 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- den Broeck, G.V.; Lykov, A.; Schleich, M.; Suciu, D. On the tractability of SHAP explanations. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 74, 851–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehboob, R.; Munir, M.; Azeem, A.; Naeem, S.; Tariq, M.A.; Ahmad, F.J. Low platelet count associated with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Int. J. Adv. Chem. (IJAC) 2013, 1, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.K.; Ghosh, B.; Chakraborty, A.; Hazra, S.; Goswami, B.K.; Bhattacharjee, S. Haematological parameters as predictors of severe dengue: A study from northern districts of West Bengal, India. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2025, 62, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).