Abstract

In the field of natural language processing, depression forecasting from social media has gained extensive attention, as platforms like X (formerly Twitter) offer real-time user-generated content that can reflect psychological states. Common approaches typically rely on static text analysis, which overlooks how users’ emotions change over time. To address this limitation, we propose a temporal modeling approach that applies deep learning models to capture both textual and temporal patterns in users’ tweet histories. Our experiments evaluated LSTM networks and Transformer architectures with pretrained embeddings on a dataset of over 3 million tweets. We demonstrate that incorporating temporal features significantly improved performance in depression forecasting. The best setting, which combines Llama 2 embeddings with personalized time-difference features, achieved 99.4% accuracy and 0.996 AUC. These results highlight the importance of modeling temporal dynamics for improving depression forecasting and suggest that personalized temporal signals provide capabilities beyond static content analysis.

1. Introduction

Depression is a common and serious mental health condition that can significantly impact people’s thoughts, emotions, motivation, behavior, and overall quality of life. Mental health professionals agree that early diagnosis and intervention are crucial, as they can effectively reduce the long-term negative effects of depression and improve the recovery outcomes. However, many people struggling with depression cannot get help due to social stigma, lack of awareness, or limited access to mental health services. This makes early detection important and also challenging [1].

The rise in social networking service (SNS) has opened up new possibilities for mental health research. Social media platforms such as X (formerly known as Twitter) allow users to share their thoughts, emotions, and daily experiences in real time. These not only can reflect the individualized emotional activities of users, but also provide valuable approaches for exploring users’ psychological states. As a result, researchers have begun to explore the use of social media data for detecting mental health conditions, especially depression.

Earlier researchers have used Natural Language Processing (NLP) to find signs of depression in posts on social media. However, for the most part, their methods were static. They usually determine whether a person is in a depressed state based on simple information contained in the content which the person posted. This approach often overlooks the dynamic nature of emotional changes and fails to capture how depressive symptoms may develop or fluctuate over time. To address this limitation, our study proposes a time series-based approach for depression detection, which is supported by the fact that some studies have demonstrated temporal associations between social media use and depression [2]. We aim to analyze the sequence of emotional patterns in a user’s tweet history, rather than treating each post in isolation. By modeling how emotional states change over time, we hope to improve both the accuracy and timeliness of depression prediction.

Specifically, we implemented two widely used deep learning architectures for NLP, the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Transformer-based models, to capture both temporal dependencies and contextual meanings within users’ tweets. The core element of this approach is to utilize pretrained embeddings from models like RoBERTa and Llama 2 to extract high-quality, nuanced textual features for the tweet. We then extract the most appropriate temporal features for integration with these textual features. The final objective is to identify an optimal feature combination for these sequence-based deep learning architectures, thereby enhancing depression prediction accuracy.

In summary, the main contributions of our study are as follows:

- We propose a novel temporal modeling approach for depression forecasting that integrates deep learning architectures with both textual and temporal features. This design addresses the limitation of previous research that relied primarily on static text analysis, which overlooks how users’ emotions change over time.

- We introduce and demonstrate the influence of a personalized time-difference feature for depression forecasting. This feature calculates the time difference between each user’s tweet and their self-reported diagnosis post, which has been shown to perform better compare to specific time indicators.

2. Related Research

Research on depression detection using social media has rapidly evolved over the past decade, employing both traditional machine learning and advanced deep learning approaches. AlSagri et al. analyzed both users’ tweet content and network activity features. The researchers extracted features such as first-person pronouns, TF-IDF, sentiment, synonyms, and various account measures (e.g., number of followers, posts, mentions) and applied classifiers like SVM, Naive Bayes, and Decision Tree. The results indicated that utilizing a richer set of features leads to higher accuracy and F-measure scores, with the SVM-linear classifier demonstrating the best performance, achieving an accuracy of 82.5% and an F-measure of 0.79 [3]. Naseem et al. reformulate depression identification as an ordinal classification task to identify depression severity levels (Minimal, Mild, Moderate, Severe) on Reddit. The authors built a new dataset based on clinical depression standards and proposed a hierarchical attention method optimized to factor in increasing depression severity levels through a soft probability distribution. Their experiments demonstrated that this method outperforms state-of-the-art models and analyzed the minimum number of posts required for identification, suggesting that combining more than one post, especially up to 10, improves accuracy [4]. These approaches treated the detection as a single classification problem based on aggregated features, failing to model the progression or fluctuation of symptoms over time.

Some studies have also incorporated temporal information. For example, Reece et al. developed computational models to predict the emergence and track the course of depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Twitter users. By collecting Twitter data and clinical diagnosis details, they extracted predictive features related to affect, linguistic style, and context. A key finding was their models successfully detect depression and PTSD onset from Twitter data several months prior to clinical diagnosis, with state-space temporal analysis revealing plausible timelines for illness progression and recovery [5]. Although this work emphasizes the importance of time analysis, their approach mainly focuses on the daily and weekly emotional changes in patients. In contrast, our research pays more attention to the individualized temporal dynamics among different individuals.

Kumar et al. propose a novel model, the AD prediction model, for predicting anxious depression in real-time tweets. The model defines a feature set using a 5-tuple vector: word (presence of anxiety-related words using a custom lexicon), timing (more than 2 posts during odd hours), frequency (more than 3 posts in an hour), sentiment (over 25% negative polarity posts in 30 days), and contrast (over 25% polarity contrast in 24 h). An ensemble voting classifier, combining Multinomial Naïve Bayes, Gradient Boosting, and Random Forest, was used. Preliminary analysis results for 100 sampled users showed the model achieved a classification accuracy of 85.09% and an F-score of 79.68% [6]. The limitation of this rule-driven approach is that it cannot generalize well to large-scale data with different linguistic patterns. Our framework directly learns representations from millions of tweets through large pretrained embeddings, significantly outperforming such methods in predictive accuracy.

The rise in large language models (LLMs) has provided more possibilities for research approaches. Lan et al. proposes DORIS, a novel depression detection system that combines medical knowledge with LLMs to achieve both high accuracy and explainability. DORIS annotates high-risk texts for symptoms, summarizes mood courses from high-emotional posts using LLMs, and integrates these medical-knowledge-guided features with a Gradient Boosting Trees (GBT) classifier. Experimental results on a benchmark dataset show that DORIS significantly outperforms existing baselines in AUPRC, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrating medical knowledge and the explanatory power of LLMs [7]. Liu et al. introduces a framework that uses ChatGPT, BERT, and SHAP to enhance mental health interventions. The system has a 93.76% accuracy rate. ChatGPT generates responses, which are then classified by BERT to ensure reliability. SHAP is then used to provide insights into the AI’s recommendations, making the intervention more interpretable. The research demonstrates the promise of using LLMs in healthcare to improve patient care and counseling practices [8]. Although these methods are highly effective, they mainly focus on the capabilities of LLMs in terms of text and semantic analysis, that often lack a deep, personalized temporal analysis component. Our temporal modeling approach can explicitly capture the evolution of users’ emotional patterns over time.

3. Method

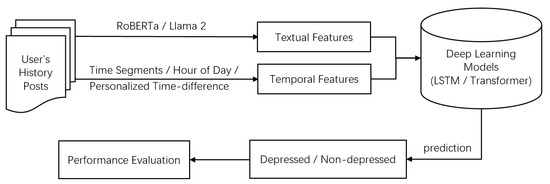

In this section, we describe the overall design of our proposed framework for depression forecasting. The methodological workflow is illustrated in Figure 1. Starting with the preprocessing of a large-scale Twitter dataset, the framework then proceeds to feature extraction, where both semantic embeddings (RoBERTa and Llama 2) and temporal features (time segments, hour of day, and personalized time-difference) are extracted. These features are subsequently integrated into deep learning architectures, including LSTM and Transformer models, to capture both contextual meanings and temporal dependencies. Finally, the trained models produce binary classifications of depressed versus non-depressed users, which are systematically evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and AUC.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of the proposed approach.

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

The data used in this experiment was sourced from the research conducted by Shen et al. [9]. It contains a total of 3,203,150 tweets, which were posted by 5895 users labeled as depressed and 4765 users labeled as non-depressed. And the time range of the tweets is from 2009 to 2017, which to some extent, bypasses special periods (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) that might have affected users’ emotional baselines. To build this dataset, a specific method for labeling users was employed. A user was designated as a depressed user if they posted a tweet containing a key phrase such as “(I’m/I was/I am/I’ve been) diagnosed depression.” Following this initial trigger, all of the user’s tweets from the past month were collected. In contrast, if a user has never posted any tweets containing the keyword “depression”, then this user is classified as a non-depressed user. By following this approach, we can separate users into two groups based on their self-reported behavior and then label the content they post.

To ensure the quality and fairness of the dataset, we applied several preprocessing steps. Retweets, as well as tweets consisting solely of URLs or user mentions, were removed, as they typically lack informative linguistic content. All remaining tweets were converted to lowercase, tokenized, and cleaned by removing excessive punctuation and non-informative emojis. At the same time, we deliberately preserved features characteristic of social media language, such as elongated words (e.g., “soooo sad”) and informal abbreviations, as these often carry meaningful emotional signals.

Furthermore, due to the significant difference in the number of tweets between the depression user group and the non-depression user group, we assigned weights to each group to balance the data. Specifically, the weight for each class was calculated inversely proportional to its frequency in the training set. This ensures that samples from minority classes contribute more to the loss function, thereby reducing the bias of the model towards the majority class. This approach can be straightforward to implement and effectively addresses class imbalance without altering the original data distribution, avoids potential overfitting that can occur with oversampling or synthetic sample generation.

3.2. Feature Extraction

3.2.1. Textual Features

In order to capture the semantic characteristics contained in the tweets, we utilized pretrained word embeddings, a critical technique in NLP where models are trained on vast corpora of text before being adapted to specific downstream tasks. We first employed RoBERTa, a robustly optimized variant of BERT for word embedding. It was trained on significantly more data over a longer period, using larger batch sizes and longer sequences to better understand context. Crucially, it introduced a dynamic masking strategy instead of BERT’s static masking, meaning the masked tokens change with each training epoch. These optimizations result in RoBERTa having enhanced performance across various downstream NLP tasks [10]. In our work, we fine-tuned RoBERTa on the collected Twitter dataset to extract sentiment scores for each tweet. These scores were used as primary text features to reflect users’ emotional expressions over time.

In parallel, we recognized the potential impact of subtle semantic differences that might not be fully captured by a sentiment score alone. Therefore, we also explored a second, cutting-edge approach using Llama 2 [11] for sentence embedding. The embedding approach was introduced by Jiang et al. The core idea is to adapt existing prompt-based representation methods for large language models (LLMs) and integrate in-context learning by creating a demonstration set of sentence-word pairs where a single word represents the sentence’s meaning. They show that this approach allows LLMs to generate high-quality sentence embeddings without fine-tuning, achieving performance comparable to current contrastive learning methods [12].

By comparing the outputs from both the fine-tuned RoBERTa model and the Llama 2 embedding approach, we were able to conduct a comprehensive analysis to assess not only the general sentiment but also the more nuanced, holistic semantic content of each tweet, providing a richer, multi-faceted understanding of the users’ emotional expressions. Therefore, we set the embedding dimensions of both RoBERTa and Llama 2 to 768 to minimize any interfering factors. To extend this analysis beyond individual tweets and capture broader trends, we adopted a similar approach to the research described in Farruque et al. [13]. By averaging all the tweet embeddings within a single day or a fixed period, the semantic information of that day or that time period can be represented.

3.2.2. Temporal Features

To model the evolution of users’ emotional states, we adopted a sliding window approach to observing sentiment scores at different sizes. We referred to standard time scales such as hourly and daily, and divided the window size into short-term and long-term as follows:

- The short-term window is designed to capture hourly sentiment fluctuations within a single day.

- The long-term window is constructed to capture daily sentiment trends across one week.

For each scale, sliding windows were applied to generate corresponding feature sequences, which were then aligned by time steps. Missing values at unobserved steps were handled using masking mechanisms.

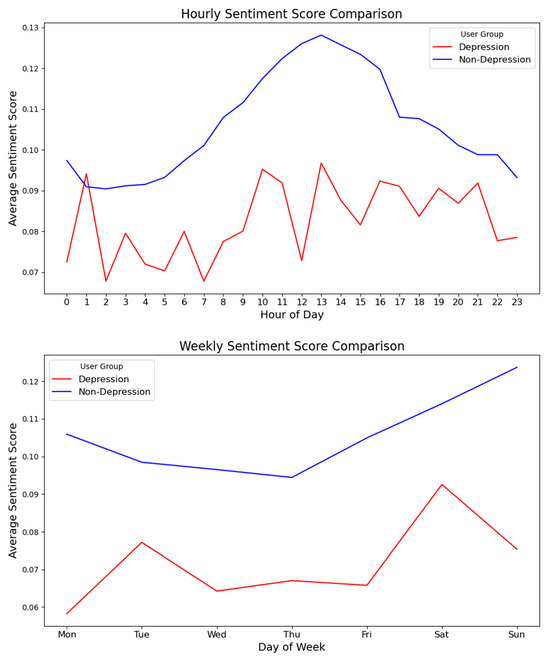

This method allows us to observe patterns and trends in emotional expression over hours and days. This work builds upon and complements prior research, such as that by Wu et al., which modeled daily mood swings as a psychiatric signal and incorporated textual and emotional characteristics via knowledge distillation [14]. Figure 2 presents the average sentiment scores for both depressed and non-depressed users across these different windows sizes, highlighting distinct emotional trajectories between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Temporal trends of sentiment scores.

As shown in Figure 2, the comparison of hourly sentiment scores can clearly illustrate the daily emotional change pattern of the users. The non-depressed group displays a clear and stable diurnal rhythm, with their sentiment scores rising in the morning, peaking around noon, and then slowly dropping off in the evening. The depressed group, however, shows a much more unstable emotional trajectory. Their average sentiment score is consistently lower than the non-depressed group, and fluctuates throughout the day, which indicates an unpredictable and unstable emotional state. From this, it can be seen that although the emotional states of the two user groups were constantly changing throughout the entire week, their emotional trajectories were significantly different, which indicates that their emotional patterns could be predictable.

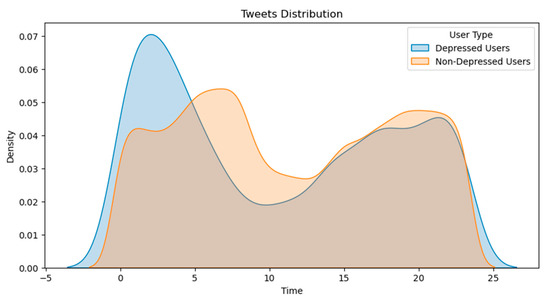

In addition to sentiment trends, we also analyzed the distribution of tweet activity across a 24-h period. As shown in Figure 3, the non-depressed users have two primary peaks in their posting activity. The first peak occurs in the morning, from around 7 a.m. to 10 a.m., which coincides with the usual time when people get up and start working. Another more obvious peak is observed in the evening, roughly from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m., which is usually the time when people relax and engage in leisure activities. In comparison, the posting activity of users with depression tends to be more concentrated during the late-night to early-morning hours, from around 12 a.m. to 3 a.m. This behavioral pattern aligns with existing clinical findings that associate insomnia and disrupted sleep schedules with depressive symptoms. Incorporating such temporal behavioral cues may significantly enhances a model’s ability to distinguish between depressed and non-depressed users, allowing the model to make more accurate predictions by considering both the content and the timing of a user’s activity on social media.

Figure 3.

Distribution of tweets over 24 h by user group.

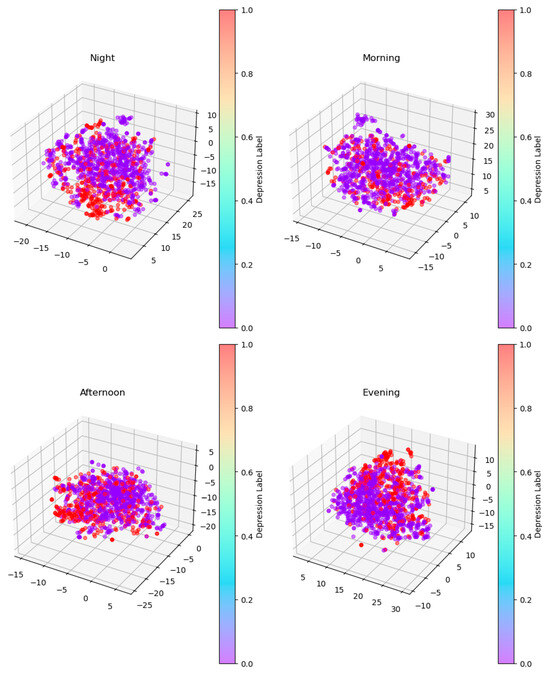

To further analyze users’ behavior patterns, we divided the 24-h of a day into four time periods: Night (00:00–06:00), Morning (06:00–12:00), Afternoon (12:00–18:00), and Evening (18:00–23:00). This division allows us to observe the distribution of users within specific time periods of a day, thereby providing a more intuitive understanding of the activity patterns across different groups. Figure 4 visualizes how the tweets of depressed and non-depressed users cluster during each of these periods. As the plots show, during morning and afternoon, the distribution of depressed users (represented in red) and non-depressed users (represented in purple) is relatively even, with no obvious distinction. This suggests that during typical daytime hours, the posting habits and content of the two groups are broadly similar.

Figure 4.

Temporal tweet distribution by user group.

However, a distinct clustering pattern emerges during the night and evening hours. During evening, the two clusters show a tendency to diverge, and the depressed users cluster appearing more isolated. In the Night plot, the red clusters representing depressed users appear denser and form a relatively distinct grouping from the purple clusters representing non-depressed users. This is consistent with the previous observations. The content and emotional expression of depressed users’ tweets during late-night hours are significantly different from those of users who are not in a depressed state.

These visualizations confirm that temporal patterns can serve as an important factor for distinguishing between different user groups. While daytime behavior may be similar, the late-night and evening posting activity of depressed users contains unique features that distinguish them from the non-depressed population.

3.2.3. Feature Combination

Before being fed into the models, for discrete types like temporal segments, we used one-hot encoding; for cyclical data such as the hour of the day, we used sine and cosine encoding for processing. Then, by combining the embedding features of the text, we constructed a fixed-length time series feature (number of users, time steps, features) as the input of the model. The first dimension represents the total number of users. The second dimension varies according to different time windows. The third dimension is the feature obtained by concatenating the text features and the time features.

3.3. Model Architecture

To effectively capture the temporal dynamics and evolving emotional patterns within tweet sequences, we implemented and compared two deep learning architectures commonly employed in sequence modeling tasks: LSTM networks [15] and Transformer-based models [16]. These architectures were chosen due to their proven capability to model dependencies across time and capture sequential context in a variety of NLP tasks.

The LSTM model is specifically designed to retain long-term dependencies in sequences. This is particularly useful for understanding how a user’s emotional patterns develop gradually or shift over extended periods. By maintaining a memory of previous states through its unique gating mechanism, the LSTM can effectively capture subtle, progressive fluctuations in mood over time. In our setup, we fed a sequence of tweets which were represented by a feature vector that combining sentiment and temporal information features into the LSTM model. The final hidden state of the LSTM, which theoretically encapsulates the cumulative trajectory of user’s emotional changes, is then used to classify user’s groups.

The Transformer model, in contrast, offers a different effective approach. It relies on self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of each tweet in the sequence, regardless of its position. This allows it to model relationships between distant tweets more efficiently and capture global trend of emotional changes without being limited by sequence length or order, which is beneficial when users have highly varied tweeting patterns. In our experiment, each tweet in a user’s sequence was encoded into a feature vector which consisted of the sentiment scores and temporal features. These feature vectors were then fed into a multi-head self-attention Transformer encoder. Sinusoidal positional encodings were added to preserve temporal order, since our model must learn the temporal patterns from sequences. The output representations were pooled and passed through dense layers to produce the final classification, which identifies the user as either depressed or non-depressed.

By comparing the performance of these two models, we could assess which architecture is better suited for capturing the specific, nuanced temporal patterns and emotional fluctuations present in our dataset.

3.4. Experiment Setup

We first divided 70% of the users in the dataset into a training group, while the remaining 30% were used for the test group to assess the model’s performance on unseen data. To optimize the models’ hyperparameters, we employed 5-fold stratified cross-validation within the training set by user, tune parameters like hidden sizes, dropout rates, and learning rate. This procedure ensured we selected the best configuration based on validation loss to prevent overfitting and improve generalization.

We used the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4 and a batch size of 32. Training ran for up to 50 epochs, with early stopping (patience = 3 epochs) monitored on validation loss to prevent overfitting. We applied L2 weight decay (1 × 10−5) and kept dropout layers active during training. In preliminary experiments, these settings (hidden sizes, dropout rates, learning rate) followed common practice in NLP tasks to balance model capacity and generalization.

To evaluate the impact of temporal information on model performance, we experimented with different combinations of textual and temporal features:

- Setting A: Textual Features Only. In this baseline setting, we used only textual features to classify users. The feature vectors for each tweet were derived solely from the output of the RoBERTa and Llama 2 models, capturing the semantic and emotional content of the tweets. This setting provided a foundational benchmark, allowing us to assess how well a model can perform without any knowledge of when the tweets were posted;

- Setting B: Textual Features + Temporal Segments. We combined textual features with the four temporal segments (Night, Morning, Afternoon, Evening), as we defined in Section 3.2.2 earlier. This setup enables the model to utilize users’ behavioral patterns at different time periods as predictive signals;

- Setting C: Textual Features + Hour of Day. This setting uses the specific time period (0–23) when each tweet is posted as a time feature, which differs from the broader time segments in setting B. This provides the model with a precise, high-resolution time background, enabling it to observe daily emotional cycles in greater detail;

- Setting D. Textual Features + Time Difference. This setting introduced a unique and highly relevant temporal feature: the time difference (in days) between each tweet and the user’s self-reported depression diagnosis post. This feature directly connects each piece of user data to a specific point in their personal timeline relative to a known event. For depressed users, this feature allows the model to analyze how their emotional expression changes as they approach or move away from their self-diagnosis. We attempt to explore personalized temporal contexts that is directly related to potential diseases through this setting.

4. Result

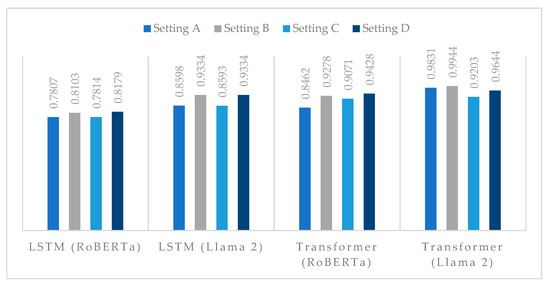

In this section, we will present a detailed comparison of model performance across different feature combinations and model architectures. As shown in Table 1, through the evaluation we can see that integrating temporal features significantly improved model performance.

Table 1.

Model performance.

There are a few points worth noting. First, adding temporal features (B–D) consistently boosts performance over the static baseline (A). For example, the LSTM with Llama 2 embeddings rose from 81.03% accuracy in A to 93.34% in B and 99.44% in D. Figure 5 provides a more intuitive illustration for the accuracy of each model with different settings. This highlights the significance of observing the trajectory of emotional changes, when sentiment analysis of single tweets alone is less predictive than patterns over time.

Figure 5.

Accuracy of each model with different settings.

Second, Llama 2-based embeddings outperformed RoBERTa in nearly all cases. In Setting A, LSTM (Llama 2) achieved 81.03% vs. 78.07% for LSTM (RoBERTa). In Setting B, recall jumped from 0.8185 to 0.9610 with Llama 2. This suggests LLM-derived embeddings capture subtler sentiment cues than fine-tuned RoBERTa alone. Notably, when adding temporal info (C/D), both model types improved, but LSTM (Llama 2) remained strongest.

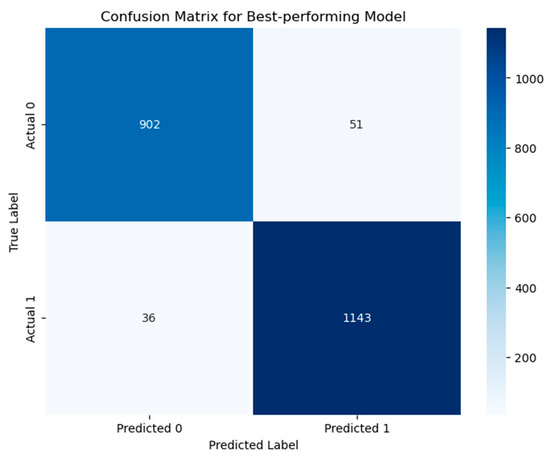

Third, the LSTM often matched or exceeded the Transformer, especially with fine-grained temporal data. Intuitively, LSTMs’ memory may better exploit ordered time gaps for mood changes, whereas Transformers may miss very long dependencies or minute fluctuations. Both models achieved high AUC (>0.98) in Setting D, indicating robust discrimination. Figure 6 shows the confusion matrix for best-performing model.

Figure 6.

Confusion Matrix for Best-performing Model.

In summary, our enhanced analysis clearly shows that finer temporal modeling yields superior depression detections. These results highlight the importance of modeling the trajectory of users’ emotional changes rather than relying solely on static textual representations. Depression is not always evident in isolated tweets; rather, it often manifests as a gradual or fluctuating pattern over time. Notably, compared to using only general temporal features like segments (setting B) or hours of the day (setting C), setting D yielded the most significant and crucial results. This indicates that simple, generic time information is not enough to fully reflect the unique behavioral patterns of depressed users, and that personalized temporal information is of great value for user classification

5. Discussion

Our findings emphasize that depression detection can benefit not only from semantic analysis of text, but also from understanding when and how consistently emotional content is expressed over time. In our experiments, the night period showed the highest discriminative power, supporting the hypothesis that late-night activity is a potential behavioral marker of depression. Incorporating time-based features, such as posting periods (e.g., Night, Morning) and sentiment trends over time, significantly improved model performance.

When sentiment scores were aggregated over different time windows, models were better able to capture emotional fluctuations that are often overlooked in static classification approaches. We achieved significant predictive results by introducing a personalized time difference relative to each user’s self-reported diagnosis date. The uniqueness of this feature is that it links every tweet to a specific, clinically relevant anchor point in the user’s personal timeline. This allows the model to analyze how a user’s emotional and behavioral patterns change before and after a diagnosis. For example, the model can learn that a user might exhibit stronger negative emotions and irregular posting behavior in the period leading up to their diagnosis, a pattern that simple timestamps cannot reveal. Additionally, it provides a unique chronological context for each user, enabling the model to understand that the “when” of a post is far more important than the “what time.” This personalized temporal dimension allows the model to more accurately identify behavioral signals that are closely related to the development process of depression.

In Table 2, we compare and summarize our best-performing model with the representative methods from recent studies.

Table 2.

Comparison of methods in recent research.

6. Conclusions

We propose a temporal modeling approach for depression forecasting using deep learning on social media data. The core idea is to integrate both textual features (from pretrained embeddings like RoBERTa and Llama 2) and temporal features into deep learning models (LSTM and Transformer). We analyzed general temporal cues (time segments and hour of day) but found the most significant impact from a personalized time-difference feature. Combining Llama 2 embeddings with the personalized time-difference feature (Setting D) in an LSTM network achieved the optimal performance. Based on these contributions, there are still some issues that need to be explored:

6.1. Model Applicable Boundaries

This model is currently only applicable to English-speaking Twitter users. It is important to note that the proposed model should be considered as an auxiliary signal rather than a diagnostic tool in clinical settings. And what the model predicts is only users who are suspected to have a risk of depression, rather than directly classifying them as people with depression.

6.2. Limitations

There are certain limitations in applying artificial intelligence to predict depression on social media platforms, which require careful consideration. Considering the differences in language style exist among various populations, including factors such as age, gender, cultural background, and geographic region. Models primarily trained on English-language tweets from a singular population may not generalize effectively, leading to biased or inaccurate diagnoses for diverse user groups. And using multilabel datasets, such as the approach proposed by Abu Bakar Siddiqur Rahman et al. [17], might offer a more detailed and precise method for identifying depression. These will be a future research direction.

Another important point is that, although the tweets are publicly accessible, users may not have anticipated or consented to their data being analyzed for the purpose of assessing their mental health status. Using personal data beyond its intended purpose can infringe upon a user’s right to privacy and might raise some issues related to ethics and privacy. For example, a casually posted comment expressing negative emotions might be misinterpreted as a sign of depression, leading to unnecessary worry or stigmatization for the user. Therefore, any such analysis must be approached with great care.

6.3. Future Work

Since human behaviors are inherently time-dependent, and the personalized time-difference feature is not strictly bound to a specific modality but rather models temporal intervals, there is potential for its extension to other modalities. Beyond focusing on textual content, the link between depression and temporal factors may also be explored from other perspectives. For example, based on facial expressions [18,19,20], speech [21,22,23], human activity recognition (HAR) [24,25] and electroencephalogram (EEG) [26,27,28], etc. In future work, we plan to expand this framework to include these multimodal signals, cross-platform behaviors (such as on Reddit, Instagram), and multilingual environments to accommodate different occasions and requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S. and I.P.; methodology, Z.S. and I.P.; software, Z.S.; validation, Z.S. and I.P.; formal analysis, Z.S.; investigation, Z.S.; resources, I.P.; data curation, Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.S.; writing—review and editing, I.P.; visualization, Z.S.; supervision, I.P.; project administration, I.P.; funding acquisition, I.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in reference [9].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Fine, M.J. Temporal Associations Between Social Media Use and Depression. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsagri, H.S.; Ykhlef, M. Machine Learning-Based Approach for Depression Detection in Twitter Using Content and Activity Features. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2020, E103-D, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, U.; Dunn, A.G.; Kim, J.; Khushi, M. Early Identification of Depression Severity Levels on Reddit Using Ordinal Classification. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 2563–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, A.G.; Reagan, A.J.; Lix, K.L.M.; Dodds, P.S.; Danforth, C.M.; Langer, E.J. Forecasting the Onset and Course of Mental Illness with Twitter Data. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, A.; Arora, A. Anxious Depression Prediction in Real-Time Social Data. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Cheng, Y.; Sheng, L.; Gao, C.; Li, Y. Depression Detection on Social Media with Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.10750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, X.; Peng, S.; Zhang, C. Leveraging ChatGPT to Optimize Depression Intervention through Explainable Deep Learning. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1383648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Jia, J.; Nie, L.; Feng, F.; Zhang, C.; Hu, T.; Chua, T.-S.; Zhu, W. Depression Detection via Harvesting Social Media: A Multimodal Dictionary Learning Solution. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; AAAI Press: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2017; pp. 3838–3844. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Huang, S.; Luan, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhuang, F. Scaling Sentence Embeddings with Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.16645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farruque, N.; Goebel, R.; Sivapalan, S.; Zaïane, O. Deep Temporal Modelling of Clinical Depression through Social Media Text. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2024, 6, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Hua, Y.; Lin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J. Exploring Social Media for Early Detection of Depression in COVID-19 Patients. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 3968–3977. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Łukasz; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.B.S.; Ta, H.-T.; Najjar, L.; Azadmanesh, A.; Gönul, A.S. DepressionEmo: A Novel Dataset for Multilabel Classification of Depression Emotions. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 366, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chaturvedi, I.; Ji, S.; Cambria, E. Sequential Fusion of Facial Appearance and Dynamics for Depression Recognition. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 150, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, W.C.; Granger, E.; Lopez, M.B. Facial Expression Analysis Using Decomposed Multiscale Spatiotemporal Networks. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Shang, Y.; Liu, T.; Shao, Z.; Guo, G.; Ding, H.; Hu, Q. Spatial–Temporal Attention Network for Depression Recognition from Facial Videos. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Cao, C. Automated Depression Analysis Using Convolutional Neural Networks from Speech. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 83, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloshban, N.; Esposito, A.; Vinciarelli, A. What You Say or How You Say It? Depression Detection Through Joint Modeling of Linguistic and Acoustic Aspects of Speech. Cogn. Comput. 2022, 14, 1585–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhu, Z.; Jing, X. Deep Learning for Depression Recognition from Speech. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2024, 29, 1212–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, F.; Alam, S.; Bahadur, E.H.; Masum, A.K.M.; Rahman, M.Z. Deep Learning for Depression Symptomatic Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Innovations in Science, Engineering and Technology (ICISET), Chattogram, Bangladesh, 25–28 February 2022; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.F.I.; Anjum, F.; Alam, S.; Bahadur, E.H. Depression Detection through Activity Recognition: Deep Learning Models Using Synthesized Sensor Data. J. Basic. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 571–590. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiei, A.; Zahedifar, R.; Sitaula, C.; Marzbanrad, F. Automated Detection of Major Depressive Disorder with EEG Signals: A Time Series Classification Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 73804–73817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Kumar Bajpai, M.; Kumari Bharti, K. Spatio-Temporal Features Based Deep Learning Model for Depression Detection Using Two Electrodes. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 086015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sütçübaşı, B.; Ballı, T.; Metin, B.; Elif Tülay, E. Neural Signatures of Depression: Classifying Drug-Naïve MDD Patients with Time- and Frequency-Domain EEG Features during Emotional Processing. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2025, 6, 025035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).