Abstract

Wake vortex is a critical factor affecting aircraft safety and airport runway capacity. To assess the runway capacity of mixed operations for training and transport airports, this study first simulated the wake vortex dissipation process of the commonly used A321 aircraft at Luoyang Beijiao Airport using a wake vortex prediction model. The SR20 training aircraft was selected as the subject for wake vortex encounters, with the rolling moment coefficient used as an indicator to assess the risk of wake encounters, and the wake vortex safety separation was calculated. Finally, a runway capacity model based on runway average service time for mixed training and transport operations was developed, calculating both runway landing capacity and the total runway capacity in the continuous landing and interleaved takeoff mode. The simulation results indicate that under different atmospheric BV frequencies, the safe wake vortex separations for the A321–SR20 combination are 6375 m, 6188 m, and 5700 m, respectively, representing reductions of 31.5%, 33.2%, and 38.4% shorter than the current CCAR-93TM-R6 regulatory separations, and compared to the RECAT 1.5 and RECAT-EU standards. Under reduced separation conditions, runway capacity demonstrated improvement across various atmospheric conditions and operational modes.

1. Introduction

Wake vortex is a pair of swirling airflows generated at the wingtips during aircraft flight, characterized by its intensity, long duration, and large spatial scale. It poses a significant safety threat to following aircraft, especially during takeoff and landing phases [1]. To reduce the threat of wake vortex encounters during aircraft operations, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) has developed wake vortex separation standards based on operational experience (ICAO Doc 4444), which have been in place since the 1970s. These standards classify aircraft by their maximum takeoff weight and provide corresponding safety separation for different aircraft pairings. The aim of these standards is to establish a safety separation between the leading and following aircraft to prevent wake vortex-related safety incidents. As civil aviation continues to develop, a critical research topic has emerged: how to reduce wake vortex separation while ensuring safety, in order to enhance airport operational capacity. In airports with mixed operations of transport and training aircraft, where civil transport aircraft and training aircraft share the same airspace and exhibit significant differences in weight and flight speed, wake vortex separation and the configuration of training flight procedures become key factors limiting runway capacity enhancement. With the increasing demand for civil air transport, analyzing the safety impact of wake vortices from transport aircraft on training aircraft, calculating the wake vortex safety separation, and simulating the operation modes of both civil transport and training flights are crucial for quantifying airport runway service levels and improving runway capacity efficiency.

The aircraft wake vortex significantly impacts airspace utilization, Wang et al. [2] proposed an improved hybrid deep learning network Inception-VGG16 to enhance the accuracy of aircraft wake vortex identification. The model extracts Doppler radar data features from multi-scale and deep spatial levels, and its recognition performance was validated using experimental data collected at Chengdu Shuangliu Airport. Pan et al. [3] explored aircraft wake vortex identification using a deep learning approach. The study focused on the wake vortices generated by aircraft during takeoff and landing, particularly in the near-field phase, where the low altitude and ground effect make the vortex more dangerous. Using the YOLO v3 deep learning model, the study identified wake vortices through laser radar scanning and deep neural network simulations. The results showed that the model could accurately recognize wake vortices, providing air traffic controllers with valuable decision-making support to ensure flight safety. Roa et al. [4] conducted an assessment of runway capacity at Chicago O’Hare International Airport, aiming to study the impact of wake vortex separation on runway limitations. The assessment utilized a Monte Carlo simulation model, considering static and dynamic wake vortex separations, aircraft fleet mix, runway occupancy time (ROT), aircraft approach speeds, wake vortex circulation, environmental conditions, and operational error buffers. Their results showed that when the simulated RECAT II/III separation times were shorter than the ROT from the simulation, reducing the separation time could enhance runway capacity.

Existing research on the impact of wake vortex separation on runway capacity generally does not fully consider the complexity introduced by the mixed operations of transport and training flights. However, transport aircraft and training aircraft differ significantly in terms of type, flight performance, and operational modes, leading to different wake vortex characteristics and encounter risks. Therefore, this study focuses on the Training and Transport operations scenario at airports:

- Based on the context of reducing wake encounter safety separation, it simulates the wake vortex evolution process for transport aircraft and integrates wake encounter response analysis to systematically assess the wake vortex safety separation requirements for a medium aircraft in the front and a light aircraft in the back during the approach and landing phase.

- Furthermore, a runway capacity assessment model is developed to quantify airport operational capacity under different wake vortex separation strategies.

The earliest studies on aircraft wake vortices were conducted through outdoor observational methods. Based on the lifecycle of wake vortex evolution and dissipation, the process is divided into the near field, extended near field, far field, and dissipation stages. CROW [5] proposed that the evolution and dissipation of wake vortices are influenced by long-wave instability. To further accurately quantify and analyze the evolution behavior of wake vortices, Greene [6] developed a semi-empirical approximation model that integrates atmospheric parameters such as BV frequency, turbulence, and Reynolds number to predict the motion and decay characteristics of aircraft wake vortices. By calculating air viscosity forces and buoyancy, the model determines the circulation, velocity, and position of wake vortices, and verifies that wake vortex decay is mainly caused by Crow instability. The model’s predictions align well with field observation data. For the study of wake vortex evolution and dissipation near the ground, Sarpkaya et al. [7] proposed the APA wake vortex prediction model, incorporating the ground effect of wake vortices. This model enhances the ability to simulate and predict near-ground wake vortices and is used in the Aircraft Vortex Spacing System (AVOSS) to reduce wake vortex safety risks. Holzäpfel [8] introduced the Probabilistic Two-Phase (P2P) prediction model, noting that the descent rate of the wake vortex has a nonlinear relationship with vortex strength. The model uses probabilistic intervals for wake vortex position and strength to explain the deviations between model predictions and deterministic vortex behavior. Through comparison with detection data, the model’s validity and applicability were verified. Campos et al. [9] studied the impact of leading aircraft wake on the lift, rolling moment, and roll stability of following aircraft, and calculated the wake vortex safety separation for different aircraft types under varying atmospheric conditions. Luo et al. [10] investigated the evolution of A333 aircraft wake vortex under different turbulence dissipation rates using large eddy simulation, and calculated the rolling moment coefficient (RMC) of the ARJ21 aircraft. The results showed that the wake separation for the ARJ21 following the A333 during the approach phase is reduced by approximately 33% compared to the ICAO RECAT standard. PAN et al. [11] studied the effect of different BV frequencies on aircraft wake vortex evolution and constructed a wake hazard zone for the A320 and ERJ190 aircraft following the A330 wake, calculating the wake vortex safety separation. With the rapid development of deep learning, its application in aircraft wake vortex research has been extensive, Deng et al. [12] proposed the TransCNN model, a hybrid framework combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers to improve aircraft wake vortex identification and safety interval assessment. The model integrates multi-scale hybrid attention modules and global feature fusion to enhance feature extraction, achieving an impressive accuracy of 99.09% in wake vortex detection, surpassing traditional methods by 12.09%. Additionally, Deng et al. [13] introduced the PA-TLA model, a parallel hybrid architecture combining Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and an attention mechanism. The PA-TLA model efficiently predicts aircraft wake evolution and significantly outperforms other models, achieving up to 35% improvement in prediction efficiency.

Appropriate wake vortex separation is a key factor in enhancing airport runway capacity and optimizing takeoff and landing scheduling. Aircraft must maintain the specified minimum time or separation during takeoff or landing to ensure that following aircraft do not enter hazardous wake vortex regions. This separation standard, based on wake vortex classification and aircraft performance, directly determines the number of aircraft movements that a runway can accommodate per unit time, becoming one of the bottlenecks restricting runway operational efficiency. In recent years, the concept of Time-Based Separation (TBS) has been proposed [14], aiming to dynamically adjust the separation time based on current weather conditions such as wind speed and direction, in order to maintain a consistent wake vortex decay level. In particular, under strong headwind conditions, the time interval between following flights can be significantly shortened, thus improving runway usage efficiency. By converting wake vortex separation into a time-based separation format, a more refined assessment of runway capacity can be achieved. Tee et al. [15] simulated different runway operational scenarios by adding flights from low-cost carriers to assess their impact on airport runway capacity. The results indicated that assigning a dedicated runway for medium arriving aircraft could improve runway service capacity. Hu et al. [16] based on ASDE-X data and the RUNSIM model, proposed a composite separation rule that combines wake vortex separation and ROT limitations, in order to assess the impact of ROT limitations on runway throughput capacity during peak periods at airports and estimate the effectiveness of new ROT separation rules in avoiding go-around events. Chen et al. [17] proposed the concept of a runway expansion system and developed a runway arrival, departure, and mixed operations capacity assessment model for general aviation airports. Maltinti et al. [18] introduced a new method for designing Rapid Exit Taxiways, which, through real-world airport validation, can effectively increase runway hourly capacity and reduce ROT. Tascón et al. [19] used system dynamics methods to predict air traffic flow at Bogotá’s capital airport and assess the impact of future traffic demand on runway capacity, suggesting the need to add more runways to cope with traffic growth challenges. Katsuhiro et al. [20] proposed a data-driven simulation approach, considering actual operational constraints and weather conditions, to evaluate the impact of smaller aircraft separation standards on the available airspace and runway capacity at Tokyo International Airport. The results showed that adopting RECAT standards could reduce terminal area guidance time by 7–10%, increase airspace capacity by 10%, and significantly reduce route and departure delay times. Cetek et al. [21] developed a discrete-event simulation model to analyze the runway capacity of training airports under different operational scenarios. Itoh et al. [22] proposed a data and queue-based model approach to analyze the impact of new, reduced aircraft separation standards on arrival delays within a 100 nautical mile radius of the airport. The experimental results indicated that this strategy could increase aircraft arrival capacity to 120% of the original. Chen et al. [23] proposed an improved stochastic frontier analysis method based on causal statistical modeling, which can capture key factors and interactions affecting runway system capacity, providing precise runway capacity estimates for short-term decision-making. Mascio et al. [24] optimized the mixed operation mode using the RECAT separation matrix and parallel runway coordination rules, achieving high-precision capacity prediction. Comparing this with the fast simulation method, they revealed that the runway capacity on the airside can be increased by up to 18%. The contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- By constructing a multi-model analysis approach, the H-B wake vortex initialization model for the A321 aircraft is developed, and the wake vortex evolution and dissipation model is used for simulation calculations.

- Based on the simulation results of the A321 wake vortex, the strip method is employed to establish the force model for the SR20 training aircraft. The wake vortex safety separation for the SR20 training aircraft following the A321 during the approach and landing phase is calculated using the RMC risk Threshold.

- By incorporating the flight rules of training aircraft, a runway capacity model for mixed operations at airports is constructed. This model assesses both the current separation standards and the reduced separation intervals for runway landing capacity and interleaved landing and takeoff capacity, and compares the results with the runway capacity based on airport operational separation standards.

2. Methods

2.1. Model Building Process and Methodology

The core objective of this study is to predict the wake vortex of civil aviation aircraft, analyze the wake encounter risk for training aircraft, and determine the wake safety separation, which is then used to assess the runway capacity. The research scenario involves mixed operations of training flights and civil air transport. In this scenario, due to the significantly lower speed of training aircraft compared to civil aircraft, their longer flight times during the approach and landing phases affect runway operational efficiency.

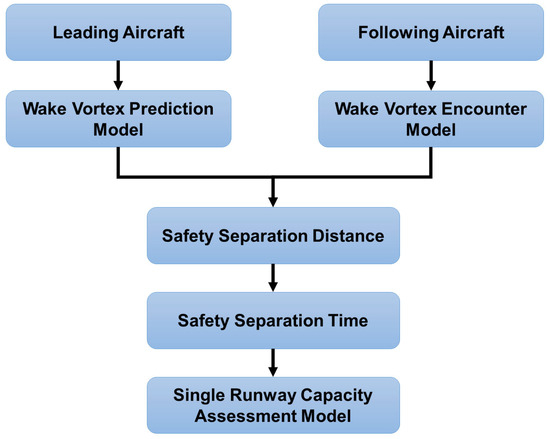

First, the wake vortex prediction model is developed based on the approach phase parameters of civil aircraft to predict the wake vortex circulation, velocity distribution, and provide foundational data for subsequent risk analysis. A wake encounter risk analysis model is then established based on the wake prediction results to assess the wake encounter risks between training aircraft and civil aircraft under different atmospheric conditions. By calculating the RMC that the following training aircraft can tolerate, the minimum safe separation between the training and civil aircraft can be determined, avoiding safety issues caused by wake vortices. This model not only considers the performance of training aircraft and the set benchmark meteorological conditions but also accounts for the particularities of the flight tasks, such as the low speed and high maneuverability of training flights, ensuring a more comprehensive risk assessment in mixed operational scenarios. Finally, the runway capacity assessment model combines the results of the first two models, taking into account the difference in approach speeds between the two types of aircraft, converting the safety separation into a time interval, and using this conversion to assess the maximum capacity of a runway at the airport. By converting the safety separation into a time interval, the model enables a more accurate assessment of the maximum throughput capacity of the airport under specific flight conditions.

As shown in Figure 1, this model not only provides a quantitative analytical tool for runway capacity at airports but also helps air traffic controllers in effectively planning flight intervals to improve operational efficiency. In a mixed operation environment, the model takes into account the specific needs of civil air transport and training flights, thereby optimizing the airport scenario.

Figure 1.

Runway capacity assessment methodology flow.

2.2. Wake Vortex Prediction Model

Based on the aircraft parameters, the Hallock-Burnham (H-B) wake vortex induced velocity initialization model [25] is constructed, as shown in Equation (1) below:

In Equation (1), M denotes the aircraft weight, g is the gravitational acceleration, p represents the air density, B is the wingspan, and V is the true airspeed of the aircraft. ωs is the characteristic velocity of the wake vortex. Vy(r) is the vertical induced velocity of the aircraft wake vortex at a distance r from the vortex core center, Γ0 is the initial circulation of the vortex pair, and rc is the vortex core radius, where rc is taken as 0.052B.

The simulation of the wake vortex evolution and dissipation phase adopts the prediction method proposed by Sarpkaya [26], and the initial parameters for wake vortex modeling are listed in the table. The wake vortex evolution and dissipation process is divided into two stages: the near-field dissipation phase and the far-field dissipation phase. During this process, the characteristic time t0 of the near-field vortex, the duration tc, the turbulence dissipation rate ε, the dimensionless turbulence dissipation rate ε*, the Brunt–Väisälä (BV) frequency N [27], and the dimensionless buoyancy frequency N* are closely related. The relevant equations are as follows:

During the near-field dissipation phase of the wake vortex, this process can be described by an approximate model. From Equation (4), the circulation Γn of the wake vortex during the near-field dissipation phase can be derived, where Γ0 represents the initial circulation of the wake vortex. After the dissipation in the near-field phase, the buoyancy of the air, gravity, and viscous forces will affect the dissipation of the far-field vortex. During this phase, wake vortices induce sinking motions, and the dissipation rate increases significantly. The variation in wake vortex intensity over time is given by Equation (5), where Γf represents the circulation of the wake vortex after near-field dissipation:

The experimental setup includes three cases of dimensionless BV frequency: 0, 0.25, and 0.5. The wake vortex evolution is calculated at different times, with the average circulation of the circular surface with a radius ranging from 5 to 15 m being nondimensionalized [28]. The average circulation is given by the following equation:

2.3. Wake Encounter Model

During the final approach phase, the following aircraft will encounter the wake vortex of the leading aircraft in the longitudinal direction within the final region. When the following training aircraft encounters the induced velocity field formed by the wake vortex of the leading A321 aircraft during its approach and landing, it will generate additional lift on the wings. Due to the unequal aerodynamic forces on the left and right wings, the aircraft will experience a rolling moment, causing varying degrees of roll. If the rolling moment exceeds the control capacity of the training aircraft, making it difficult for the aircraft to correct the roll, it will pose a threat to the flight safety of the training aircraft.

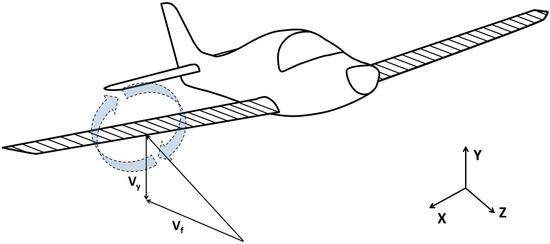

The force model for the following training aircraft is simplified by strip modeling, as shown in Figure 2. When the following aircraft encounters the wake vortex of the leading aircraft, additional lift is generated on each strip due to the vertical induced velocity. The calculation process is as follows:

In Equation (7), ΔLw represents the additional lift on the wing surface caused by the wake vortex of the leading aircraft, p is the air density, Bf is the span length of the training aircraft’s wing in the X direction, Vf is the flight speed of the training aircraft, Csl(x) is the wing chord length in the spanwise direction of the training aircraft, and x is the distance from the training aircraft’s wing strip to the origin of the coordinate system. The variation in the lift coefficient, Cw(x), can be calculated using the following equation:

As shown in Equation (8), Vy(x) is the induced velocity of the wake vortex from the leading aircraft acting on the training aircraft’s wing section, and Cθ is the slope of the lift curve. This can be further used to derive the rolling moment Mw experienced by the following training aircraft’s wing:

The dimensionless RMC is used as an indicator for evaluating the wake vortex encounter risk of different aircraft types, as shown in Equation (10). In the final approach phase, the RMC limit for medium and light aircraft is approximately 0.05 to 0.07 [29,30]. Exceeding this safety threshold will lead to aircraft instability and loss of control. Considering both the safety of wake vortex encounters and operational efficiency, the RMC safety threshold was set to 0.06. This value was selected as a balanced choice, ensuring both safety and operational efficiency. The RMC can be calculated using the following equation:

In the equation, Sf represents the wing area of the following training aircraft.

Figure 2.

SR-20 wing force analysis model.

2.4. Runway Capacity Assessment Model

Runway capacity is defined as the maximum number of aircraft that can be served by the runway per unit of time, typically represented as the weighted average service time for all types of aircraft. Before developing the mathematical model for the runway capacity at Luoyang Beijiao Airport, several assumptions were made: first, the airport’s ground facilities support the normal operation of medium and light aircraft; second, meteorological conditions are favorable, meeting the operational requirements for continuous approach, landing, and takeoff; and third, air traffic controllers are qualified to meet the operational requirements of the airport.

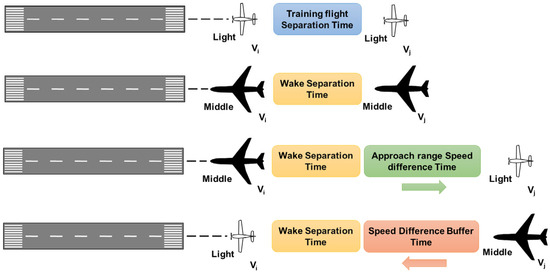

In the runway capacity assessment experiment of this study, environmental factors such as wind conditions and temperature variations were not modeled or considered, primarily based on the following two reasons. First, to accurately quantify the nonlinear relationship between wake vortex separation and runway capacity, it is necessary to eliminate the coupling effects of environmental parameters as much as possible using the control variable method, so as to isolate the impact of environmental variables. Second, from the perspective of the benchmarking and comparability of capacity assessments, existing capacity assessment experiments typically do not incorporate environmental factors such as wind speed, temperature, and air pressure as variable inputs, nor do they provide mechanisms for modeling dynamic weather changes. To ensure the reproducibility and consistency of results across different studies, capacity assessments generally rely on fixed meteorological assumptions. Therefore, this study chooses to conduct the capacity assessment experiment under standardized calm wind meteorological assumptions, which aligns with the normative requirements of the current assessment framework, as shown in Figure 3 for aircraft approach separation.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of aircraft approach separation.

In the mixed operations scenario of transport and training flights, this study optimizes the runway capacity model for aircraft during the final approach phase under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) and Visual Flight Rules (VFR). For IFR, RASRij represents the radar wake time separation requirement between the leading and following aircraft during approach. This separation requirement mandates that two consecutive approaching aircraft maintain a sufficient radar wake safety separation to ensure that the leading aircraft i and the following aircraft j do not violate the minimum separation requirements set by air traffic control during the approach phase.

As shown in Figure 4, different approach scenarios are illustrated. The approach speed of medium aircraft performing civil aviation transport operations is higher than that of light aircraft engaged in training flights. When a light aircraft is the leading aircraft, the speed difference results in a “catch-up” effect in the final approach segment, causing the relative separation between the two aircraft to gradually decrease over time. To address this effect, the RASR between the leading and following aircraft is adjusted to compensate for the reduction in spatial wake separation caused by the speed difference. A time buffer term is introduced to ensure operational safety. Conversely, when the leading aircraft is a medium aircraft, the speed difference increases the temporal separation between the two aircraft during the approach phase. The separation between the two aircraft during the approach phase is calculated as shown in the following:

In Equation (11), Dij,w represents the minimum wake safety separation between the two approaching aircraft, Vi is the approach speed of the leading aircraft, Vj is the approach speed of the following aircraft, and Dapp is the distance of the final approach path.

Figure 4.

Approach aircraft combination categories diagram.

According to the actual operational regulations of the airport, the separation time Tij (AA) for aircraft using the same runway for consecutive takeoff and landing is the maximum of the leading aircraft’s runway occupancy time ARORi and the time interval for the following aircraft to pass the runway threshold RASRij. Therefore, we have:

The time interval between consecutively arriving aircraft at the runway threshold is weighted and summed to obtain the average runway service time:

In Equation (13), E[T(AA)] represents the average service time on the runway for an arriving aircraft. Assuming that the aircraft arrive in a random sequence, Pij represents the probability of a pair of consecutive aircraft, where the type of the leading aircraft is i with probability Pi, and the type of the following aircraft is j with probability Pj. These probabilities satisfy the following conditions:

The reciprocal of the expected value of the average service time on the runway for an arriving aircraft gives the continuous arrival capacity of a runway Cs(AA):

In air traffic control regulations, priority is generally given to landing aircraft over departing aircraft. Furthermore, at any given moment, only one aircraft can occupy the runway. A departing aircraft cannot be cleared for takeoff when a landing aircraft is within a specified distance from the runway threshold. To account for this, the time interval ADASRij between two consecutive aircraft that one landing and one departing must satisfy the following relationship:

In Equation (16), ROTAi represents the time duration the runway is occupied by the landing aircraft, ROTDi denotes the time for the last departing aircraft’s runway roll in the interval ADASRij, and k is the number of departing aircraft inserted between the landing aircrafts i and j. The term E(TDi) denotes the expected value of the continuous departure interval. In practical applications, empirical values of ARORi and ROTAi are typically set at 50 seconds, while the empirical value for ROTDi is 45 seconds. DisAD refers to the distance at which the controller issues the landing clearance to the following aircraft, which is typically set at 4 km from the runway threshold.

Additionally, under this operational scenario, the time interval between two consecutive landing aircraft in the approach phase must satisfy the following condition:

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Platform

All experiments were conducted on a computer configured with the Windows operating system. The hardware specificatsions of the computer include an Intel i7 processor, 32 GB of RAM, and a 1 TB SSD. Experiments and data processing were performed on the MATLAB R2023b and Python 3.9.23 platforms, ensuring the efficiency of the simulations.

3.2. Experimental Parameter Settings

Taking Luoyang Beijiao Airport in Henan Province as an example, it is a mixed-operation airport integrating flight training and air transport. The airport has a 4D flight zone classification and is a runway airport. The runway is 2500 m long and 45 m wide, with the primary landing direction from east to west. The minimum wake separation for the medium A321 aircraft and the light training SR20 aircraft, calculated through simulation, are used as the basis for flight interval assessment in this study. In the runway capacity assessment for this study, civil aviation transportation flights at Luoyang Beijiao Airport operate in accordance with the relevant regulations of the domestic air traffic control under the IFR. Training flights, depending on the specific training objectives, are classified and assessed under two different flight rules: VFR and IFR, to assess the runway capacity under mixed operations.

The A321 aircraft was selected as the leading aircraft type, which served as the wake turbulence model for the approach and landing phase. The specific parameters of the A321 and SR-20 aircraft categories of wake turbulence under various standards is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

A321 and SR-20 aircraft approachlanding phase parameters and categories of wake turbulence under various standards.

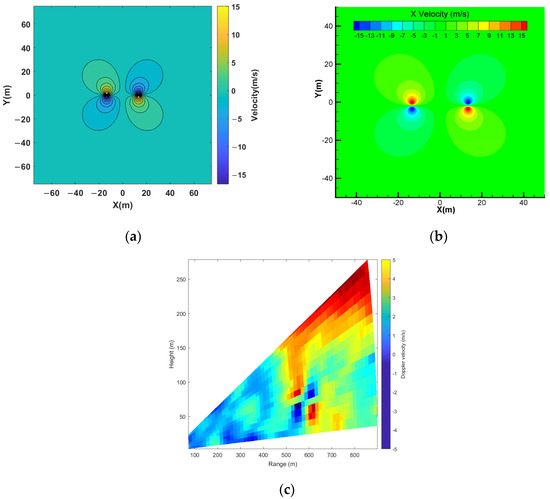

3.3. Risk Analysis of SR20 Encountering A321 Aircraft Wake

To more accurately simulate the impact of wake vortices on the following aircraft, the scenario in this study was during the aircrafts’ approach and landing phase. Therefore, a double vortex model was used to study the wake vortex effect on the following aircraft. The radial cross-section of the wake vortex field was selected, with the midpoint of the line connecting the two vortex core centers of the initial wake vortex model as the coordinate origin. The line connecting the vortex cores was defined as the X-axis, and the direction away from the ground was specified as the positive Y-axis. Based on the A321 aircraft parameters, we constructed a two-dimensional computational domain and the initial wake vortex velocity field. The comparison and validation of the velocity in the X and Y directions with the CFD simulation and LIDAR results are shown in Figure 5. The comparison results indicated that the wake vortex velocity field from the numerical simulation and detection aligns well with the predicted wake vortex model, with similar structural ranges. The simulation parameters are presented in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the A321 Wake Vortex Initial Velocity Field Evolution. (a) Induced velocity in the X direction from model; (b)Induced velocity in the X direction from CFD; (c) Induced velocity in the X direction from LIDAR detection.

Table 2.

A321 initial parameters for wake simulation.

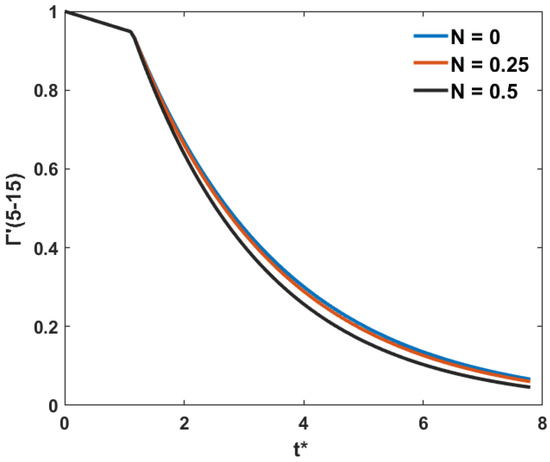

After simulation and nondimensionalization of the wake evolution time t* = t/t0, the variation in the wake vortex circulation dissipation process of the A321 aircraft at different BV frequencies is shown in Figure 6. The simulation results indicated that the BV frequency affected the dissipation rate of the wake vortex. The higher the BV frequency, the faster the dissipation rate. When t* = 4, the wake vortex intensity decreased to 23–28% of the initial circulation.

Figure 6.

Variation in wake vortex intensity decay of the A321 at different BV frequency.

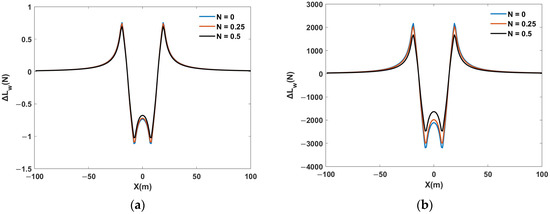

Figure 7 illustrated the change in lift generated by the vertical component of the induced wake vortex velocity of the A321 aircraft, acting on the SR20 aircraft’s wing surface at different characteristic times. Overall, the change can be considered as axisymmetric with respect to the X = 0 axis. On the positive half of the X-axis, the lift changes rapidly within the range of X = 0 m to X = 35 m, particularly at X = 14 m, where the lift changed from negative to positive. Within this range, the roll risk for the following aircraft was relatively high. The maximum positive and negative lift peaked occur at X = 7 m and X = 20 m, respectively. Additionally, the higher the BV frequency, the greater the reduction in the peak values.

Figure 7.

Variation in wing lift for SR20 Encountering A321 wake vortex at different characteristic times. (a) t* = 2.5; (b) t* = 5.5.

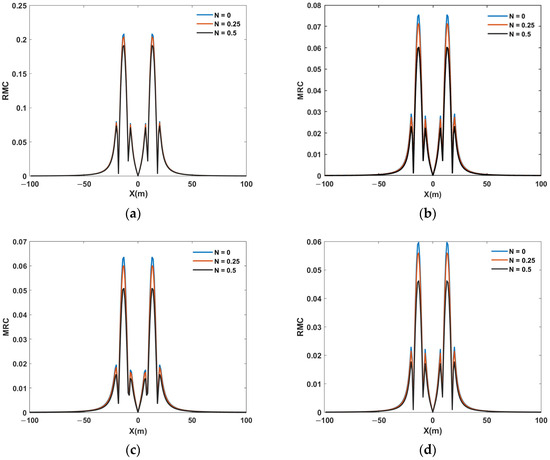

As shown in Figure 8, the encounter risk of the A321 wake vortex at different times within a 100 m range around the vortex core height was presented. The RMC values for the negative half of the horizontal axis were treated as absolute values. With the dissipation of the wake vortex, the peak value of the wake vortex at different characteristic times decreases. The BV frequency affected the rate of wake vortex dissipation; the higher the BV frequency, the faster the dissipation of the wake vortex strength, resulting in a smaller rolling moment experienced by the following aircraft and a corresponding reduction in the RMC values. When N = 0 and t* = 5.5, the RMC value of the SR20 aircraft reached the preset safety threshold. When N = 0.25 and t* = 5.3, the RMC value also reached the same safety threshold, and when N = 0.5 and t* = 4.9, it again met this threshold. The simulation results under N = 0, 0.25 and 0.5 atmospheric conditions were therefore used as the basis for determining the corresponding safety separations. Based on the A321’s approach speed, the safe separation distance for the following light aircraft SR20 was determined to be 6375 m under N = 0, 6188 m under N = 0.25, and 5700 m under N = 0.5. These were 31.5%, 33.5%, and 38.7% smaller, respectively, than the radar-based wake vortex separations prescribed in the current regulatory document CCAR-93TM-R6. Compared to the RECAT-EU standards, the reductions were 31.2%, 33.2%, and 38.4%, while compared to the RECAT 1.5 standards, the reductions were 13.9%, 16.5%, and 23.1%. Table 3 presents a comparative summary of the wake vortex safety separations obtained from this study and those specified in the CCAR-93TM-R6, ICAO RECAT, and RECAT-EU standards. As shown, the N = 0, 0.25, and 0.5 scenarios all yield shorter separations compared to the regulatory requirements. The proposed wake vortex safety separation based on the RMC threshold provided a more refined and operationally efficient standard while maintaining safety margins consistent with standard.

Figure 8.

Variation in MRC Values for SR20 Encountering A321 Wake Vortex at Different Characteristic Times. (a) t* = 2.5; (b) t* = 4.9; (c) t* = 5.3; (d) t* = 5.5.

Table 3.

Comparison of wake turbulence safety separations under different atmospheric stability conditions with international standards.

3.4. Runway Capacity Assessment

The establishment of aircraft separation was not only to ensure flight safety and prevent collisions between aircraft, but also to meet the required separation between aircraft during flight. Additionally, considering the wake vortex of the leading aircraft during the takeoff and landing phases, the wake vortex generated by civil transport aircraft may pose a threat to smaller aircraft following in its wake. Specific separation requirements varied depending on the flight rules. In airports with mixed operations, when VFR and IFR were simultaneously in operation, the separation requirements between aircraft must not only comply with the corresponding air traffic management regulations but also comprehensively considered the effects of the leading aircraft’s wake vortex and the differences in flight speeds.

The medium A321 aircraft performing civil aviation transport flights operated under IFR, while the light SR20 training aircraft were divided into VFR and IFR due to training requirements. This study discussed the aircraft separation under both IFR and VFR at Luoyang Beijiao Airport. Additionally, it compared the wake vortex encounter safety separation between the medium and light aircraft combinations from Section 3.3 with the current wake vortex separation standards to assess the airport runway capacity.

According to civil aviation air traffic management rules and the flight interval specifications for light training aircraft at Luoyang Beijiao Airport, during the final approach phase, when both aircraft operated under IFR, the separation between consecutive takeoffs and landings must consider the wake vortex effect. During the approach and landing phase, when the leading aircraft was a medium aircraft and the following aircraft was a light training aircraft, the wake vortex separation was 9.3 km, while other aircraft pairings used the minimum radar separation of 6 km. The interval between consecutive takeoffs was governed by the time separation requirements. For runway use, the following aircraft was only allowed to take off or taxi after the leading aircraft passed the runway end or started turning, or after all landing aircraft vacated the runway. Similarly, the following aircraft was only allowed to cross the runway threshold after the leading aircraft passed the runway end or started turning, or after all landing aircraft vacated the runway.

At Luoyang Beijiao Airport, the experiment distance from the final approach point to the runway threshold (Dapp) was set to 15 km. The IFR specified a 2 NM longitudinal separation between light aircraft. For wake vortex separation during takeoff, The rules required a 50 s interval between light aircraft, a 180 s interval when the leading aircraft was a light aircraft and the following aircraft was a medium aircraft, and a 120 s interval for other aircraft combinations. The reduced time intervals for different N values were indicated in parentheses, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Instrument flight rules approach landing separation time for light aircraft (seconds) under the CAAC regulation, with wake encounter safety separation time interval in parentheses, as specified in the footnote.

In the case of simultaneous operation under IFR and VFR, according to the regulations, aircraft operating under IFR and VFR are required to maintain the separation as specified under their respective flight rules. The light aircraft VFR separation was set at 50 s. However, in actual operations, the approach speed of the medium IFR aircraft was relatively higher, while the VFR aircraft had a slower speed. As a result, the longitudinal separation between the two aircraft gradually increased during the final approach phase. In this case, the separation between the aircraft wasgreater than the regulation requirements. The time intervals for the simultaneous operation of both flight rules under different N values in actual operations at Beijiao Airport are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Visual flight rules approach landing separation time for light aircraft (seconds) under the CAAC regulation, with wake encounter safety separation time interval in parentheses, as specified in the footnote.

In the interleaved operation mode of takeoff and landing, multiple factors need to be fully considered, including the ROTA of the landing aircraft, the ROTD of the departing aircraft, and the runway threshold distance when the air traffic controller issues landing clearance to subsequent aircraft. The time intervals for interleaved takeoff and landing operations under different N values are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Time interval for landing on the same runway that meets takeoff requirements (seconds) under the CAAC regulation, with wake encounter safety separation time interval in parentheses, as specified in the footnote.

In the runway capacity assessment simulation setup of this study, the simulation was conducted using the speed, wake vortex safety separation parameters of the A321 and SR20. The simulation setup aircraft type combination probabilities, limited to only medium and light aircraft. Based on this, the proportion of medium aircraft varied from 0% to 100%, with intervals of 10%. The runway capacity, considering both landing and continuous landing with takeoff, was calculated using the runway average service time model established in Section 2.4.

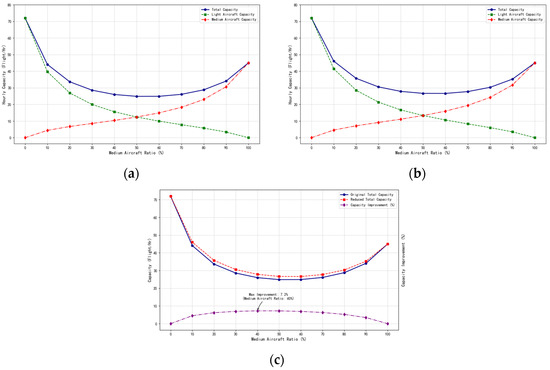

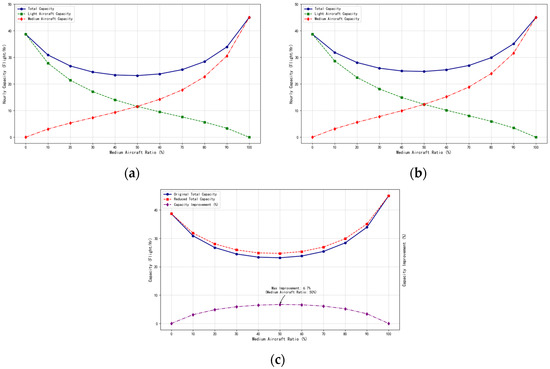

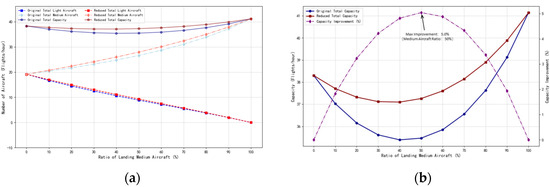

The simulation results for runway full landing capacity at N = 0 showed that when light aircraft conduct VFR training, the runway capacity was significantly higher compared to IFR training, as shown in Figure 9. This was because the approach and landing time interval for VFR training was much smaller than that for IFR training. Under the current regulatory separation standards, the maximum runway capacity of 72.00 movements per hour was only achieved during training flights. As the proportion of medium aircraft in civil aviation transport increased, the average runway service time also increased, causing a rapid decrease in runway capacity. When the proportion of medium aircraft reached 20%, the runway landing capacity was reduced to only 46.7% of the capacity for light aircraft during training flights. With the continued increase in the proportion of medium aircraft, the minimum capacity was reached at 24.87 movements per hour when the proportion reaches 50%, and then gradually increases, reaching 45.00 movements per hour when only medium civil transport aircraft were operating.

Figure 9.

Runway landing capacity for light aircraft under VFR at N = 0 according to CAAC regulations. (a) Landing capacity based on separation standards; (b) Landing capacity based on wake vortex encounter safety separation; (c) Capacity improvement comparison.

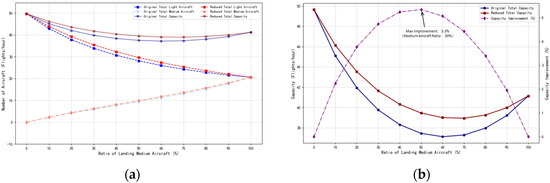

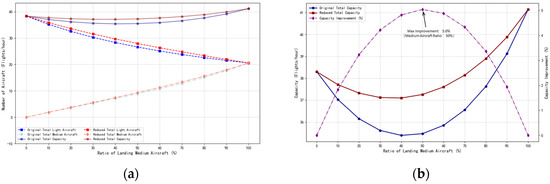

Under the wake vortex encounter safety time separation for the aircraft combination of medium aircraft in the front and light aircraft in the rear, the runway capacity increases compared to the capacity under the current separation standards. The maximum capacity improvement occurs when the proportion of medium aircraft was 40%, with the runway capacity under wake vortex encounter safety separation increasing by 7.2% compared to the current separation standards, as shown in Figure 10. When training aircraft conduct IFR landing operations, the slower flight speed of light aircraft increased runway service time. The runway capacity for training aircraft only was 38.71 movements per hour. As the proportion of medium aircraft increased, the minimum runway capacity was reached at 23.15 movements per hour when the medium aircraft proportion reached 50%. At this proportion, the runway capacity under wake vortex encounter safety separation increases by a maximum of 6.7%.

Figure 10.

Runway landing capacity for light aircraft under IFR at N = 0 according to CAAC regulations. (a) Landing capacity based on separation standards; (b) Landing capacity based on wake vortex encounter safety separation; (c) Capacity improvement comparison.

By adding takeoff aircraft between consecutively landing aircraft, the runway service time for continuous approach and landing at N = 0 can be better utilized. Under the condition that the ROTA requirement for takeoff aircraft is met, the runway capacity can be increased. As shown in the experimental results in Figure 11, when the takeoff aircraft was a light aircraft operating under VFR, and only light aircraft were conducting training flights, the separation between the two aircraft was small, allowing the runway to efficiently handle the takeoff and landing of light aircraft. The total takeoff and landing capacity was 49.66 movements per hour. As the proportion of medium aircraft increased, the runway capacity slowly decreases. When only medium aircraft were in operation for continuous interleaved takeoffs and landings, the total capacity was 41.14 movements per hour. Under the wake vortex encounter safety separation conditions, the total capacity increased by a maximum of 5.3% when the proportion of medium aircraft reached 50%.

Figure 11.

Total Runway capacity for interleaved landing and takeoff, takeoff aircraft as light aircraft under VFR at N = 0 according to CAAC regulations. (a) Runway capacity based on separation standards and wake vortex encounter safety separation; (b) Capacity improvement comparison.

When the takeoff aircraft was a light aircraft operating under IFR, as shown in Figure 12, the time interval between light aircraft was relatively large. When only light aircraft were operating, the total runway capacity was 38.30 movements per hour. As the proportion of medium aircraft increased, the total runway capacity showed a slight decrease followed by an increase. The capacity improvement under wake vortex encounter safety separation reached its maximum at 5.0% when the proportion of medium aircraft was 50%.

Figure 12.

Total Runway capacity for interleaved landing and takeoff, takeoff aircraft as light aircraft under IFR at N = 0 according to CAAC regulations. (a) Runway capacity based on separation standards and wake vortex encounter safety separation; (b) Capacity improvement comparison.

When the takeoff aircraft was a medium aircraft operating under IFR, as shown in Figure 13, all light aircraft must operate under IFR. The total runway capacity in this case was the same as the total capacity shown in Figure 12. It can be seen that when takeoff aircraft were added between consecutively landing aircraft, the factor influencing the total runway capacity was the flight rules of the light training aircraft. The capacity under VFR was higher than that under IFR.

Figure 13.

Total Runway capacity for interleaved landing and takeoff, takeoff aircraft as middle aircraft under IFR at N = 0 according to CAAC regulations. (a) Runway capacity based on separation standards and wake vortex encounter safety separation; (b) Capacity improvement comparison.

As shown in Table 7, the simulation results indicated that an increase in atmospheric instability accelerated the dissipation of aircraft wake vortices, thereby reducing the risk of wake encounters for following aircraft and allowing for a reduction in mandatory separation distances. By introducing atmospheric stability parameters into the capacity model for comparison, a clear positive correlation between the value of N and the maximum achievable capacity gain was observed across all operational scenarios. For instance, in the Medium-IFR and Light-VFR continuous landings scenario, the maximum capacity improvement increased from 7.2% at N = 0 to 7.8% at N = 0.25, a 0.6% increase, and further reached 9.1% at N = 0.5, a 1.3% increase over N = 0.25. Similar growth trends were also observed in other operational scenarios. As the N value increased, the magnitude of the maximum capacity improvement grew, demonstrating that system capacity was more sensitive to changes in atmospheric stability.

Table 7.

Simulation results of runway capacity improvements under CAAC Regulations across different scenarios, atmosphere conditions, and medium aircraft proportions.

This sensitivity highlighted the potential for capacity enhancement under unstable atmospheric conditions, as shorter but still safe separation minima could be implemented. Therefore, these findings not only confirmed the crucial role of atmospheric stability in wake-vortex-based separation safety assessments but also revealed the extent of potential capacity gains achievable under varying stability conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study focused on the scenario of mixed operations at airports for civil aviation transport and training flights. By using a wake dissipation simulation model and RMC as the risk indicator derived from encounter simulations, the study established a connection between wake vortex encounter safety and airport operational efficiency. Through a multi-model integrated analysis approach, representative aircraft were selected for this scenario. Based on the MRC analysis of wake vortex encounters and adhering to ICAO/RECAT-EU safety thresholds, the wake vortex separation for the leading civil aviation medium aircraft A321 and following training light aircraft SR20 combination during the approach phase was evaluated for reduction. The reduction scheme was implemented in the runway capacity model based on runway service time, and the capacity improvement after the separation reduction was compared and analyzed. In addition, the simulated safe separation distances were compared with the RECAT and RECAT-EU standards. The proportion of civil aviation transport aircraft was a key factor affecting the landing capacity of mixed operations airports. The capacity change for interleaved takeoff and landing operations was relatively small. The main influencing factor in this mode was the flight rules for light aircraft. Under VFR for training light aircraft, the total capacity change for takeoff and landing was more significant. The maximum increase in capacity can be achieved through the optimization of interleaved landing and takeoff operations, further enhancing runway utilization. The runway can accommodate more flights and training aircraft per unit of time, especially during peak hours, which improves airport throughput and reduces the occurrence of delays.

5. Discussion

Although this study proposes a systematic runway capacity assessment framework for mixed-operation airports based on wake vortex encounter safety, several limitations remain. The current modeling approach primarily focuses on the A321–SR20 aircraft pairing, which represents the typical operational mode at the studied airport. The model assumes conventional meteorological conditions to ensure result comparability and controllability during model validation. Therefore, the findings of this study are mainly applicable to airport operational scenarios under stable and favorable weather conditions. Future research should further consider more complex and realistic meteorological scenarios, such as strong crosswinds, vertical wind shear, and temperature gradient variations, which have a significant impact on wake vortex dissipation and encounter risk. By integrating real-time meteorological observations or high-resolution atmospheric numerical simulation data, the model’s adaptability to dynamic weather conditions can be enhanced. Furthermore, combining the wake dissipation model with mesoscale weather forecasting or field measurements based on LiDAR data can facilitate the development of safety separation management model that adjusts separation distances according to variations in atmospheric stability.

In addition, the proposed model can incorporate real-time aircraft spacing data from actual operations to dynamically adjust separation standards and runway occupancy times according to current traffic conditions, thereby supporting real-time capacity prediction and decision-making under various operational scenarios. The overall modeling framework presented in this study also demonstrates good generalizability and can be extended to other aircraft combinations and different airport configurations. Future studies may expand the model to include more aircraft weight categories, mixed Visual/Instrument Flight Rules, and diverse runway occupancy scenarios, enabling a more comprehensive evaluation of operational efficiency and safety performance under complex conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and W.P.; methodology, C.Z.; software, C.Z.; validation, Y.Z., Y.J. and X.W.; formal analysis, W.P.; investigation, Y.Z. and X.W.; resources, W.P. and X.W.; data curation, Y.J. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Z. and W.P.; visualization, C.Z.; supervision, W.P.; project administration, C.Z.; funding acquisition, W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number U2333207, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 24CAFUC01002, the Civil Aviation Flight University of China Science Innovation Fund for Graduate Students, grant number 25CAFUC10031, the Sichuan Provincial Civil Aviation Flight Technology and Flight Safety Engineering Technology Research Center, grant number GY2024-44E, the Sichuan Provincial Civil Aviation Flight Technology and Flight Safety Engineering Technology Research Center, grant number GY2024-39E and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Funds for CAAC the Key Laboratory of Flight Techniques and Flight Safety, grant number FZ2025ZX11.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request at tproc97@163.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| MRC | Rolling Moment Coefficient |

| MLW | Maximum Landing Weight |

| IFR | Instrument Flight Rules |

| VFR | Visual Flight Rules |

| RASR | Radar Wake Vortex Time Separation Between the Leading and Following Aircraft During Approach |

| Dij,w | Minimum Wake Safety Separation |

| AROR | Leading Aircraft’s Runway Occupancy Time |

| RASR | Time Interval For the Following Aircraft To Pass Runway Threshold |

| ADASR | Time Interval Between Two Consecutive Aircraft That One Landing and One Departing |

| ROTA | Runway Occupied Time of Landing Aircraft |

| ROTD | Runway Occupied Time of Departing Aircraft |

References

- Hallock, J.N.; Holzäpfel, F. A Review of Recent Wake Vortex Research for Increasing Airport Capacity. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 98, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Deng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Leng, Y. Aircraft Wake Vortex Recognition Method Based on Improved Inception-VGG16 Hybrid Network. Sensors 2025, 25, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijun, P.; Yingjie, D.; Qiang, Z.; Jiahao, T.; Jun, Z. Deep Learning for Aircraft Wake Vortex Identification. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 685, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, J.; Trani, A.; Hu, J.; Mirmohammadsadeghi, N. Simulation of Runway Operations with Application of Dynamic Wake Separations to Study Runway Limitations. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2020, 2674, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, S.C. Stability Theory for a Pair of Trailing Vortices. AIAA J. 1970, 8, 2172–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, G.C. An Approximate Model of Vortex Decay in the Atmosphere. J. Aircr. 1986, 23, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpkaya, T.; Robins, R.E.; Delisi, D.P. Wake-Vortex Eddy-Dissipation Model Predictions Compared with Observations. J. Aircr. 2001, 38, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzäpfel, F. Probabilistic Two-Phase Wake Vortex Decay and Transport Model. J. Aircr. 2003, 40, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.M.B.C.; Marques, J.M.G. On an Analytical Model of Wake Vortex Separation of Aircraft. Aeronaut. J. 2016, 120, 1534–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y. A330-300 Wake Encounter by ARJ21 Aircraft. Aerospace 2024, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Simulation Study of the Effect of Atmospheric Stratification on Aircraft Wake Vortex Encounter. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Pan, W.; Zhao, P.; Chen, K.; Wang, X. TransCNN: A Hybrid Framework for Aircraft Wake Vortex Detection and Safety Interval Assessment. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Pan, W.; Wang, Y.; Luan, T.; Leng, Y. Aircraft Wake Evolution Prediction Based on Parallel Hybrid Neural Network Model. Aerospace 2024, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visscher, I.; Stempfel, G.; Rooseleer, F.; Treve, V. Data Mining and Machine Learning Techniques Supporting Time-Based Separation Concept Deployment. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/AIAA 37th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), London, UK, 23–27 September 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tee, Y.Y.; Zhong, Z.W. Modelling and Simulation Studies of the Runway Capacity of Changi Airport. Aeronaut. J. 2018, 122, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Mirmohammadsadeghi, N.; Trani, A. Runway Occupancy Time Constraint and Runway Throughput Estimation under Reduced Arrival Wake Separation Rules. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2019 Forum, Dallas, TX, USA, 17–21 June 2019; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Xiang, H.; Han, B.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, F. Research on Runway Capacity Evaluation of General Aviation Airport Based on Runway Expansion System. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltinti, F.; Flore, M.; Pigozzi, F.; Coni, M. Optimizing Airport Runway Capacity and Sustainability through the Introduction of Rapid Exit Taxiways: A Case Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascón, D.C.; Díaz Olariaga, O. Air Traffic Forecast and Its Impact on Runway Capacity. A System Dynamics Approach. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 90, 101946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, K.; Kato, F.; Kageyama, K.; Itoh, E. Data-Driven Simulation for Evaluating the Impact of Lower Arrival Aircraft Separation on Available Airspace and Runway Capacity at Tokyo International Airport. Aerospace 2021, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetek, F.A.; Cetek, C. Simulation Modelling of Runway Capacity for Flight Training Airports. Aeronaut. J. 2014, 118, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, E.; Mitici, M. Evaluating the Impact of New Aircraft Separation Minima on Available Airspace Capacity and Arrival Time Delay. Aeronaut. J. 2020, 124, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Anupriya; Bansal, P.; Anderson, R.J.; Findlay, N.S.; Graham, D.J. Understanding the Capacity of Airport Runway Systems. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2025, 173, 104998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascio, P.D.; Rappoli, G.; Moretti, L. Analytical Method for Calculating Sustainable Airport Capacity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.N.; Proctor, F. Review of Idealized Aircraft Wake Vortex Models. In Proceedings of the 52nd Aerospace Sciences Meeting, National Harbor, MD, USA, 13–17 January 2014; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sarpkaya, T. Decay of Wake Vortices of Large Aircraft. AIAA J. 1998, 36, 1671–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatov, V.V.; Vladimirov, Y.V. Analytical Solutions of the Internal Gravity Wave Equation for a Semi-Infinite Stratified Layer of Variable Buoyancy. Comput. Math. Math. Phys. 2019, 59, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visscher, I.; Bricteux, L.; Winckelmans, G. Aircraft Vortices in Stably Stratified and Weakly Turbulent Atmospheres: Simulation and Modeling. AIAA J. 2013, 51, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Baren, G.; Treve, V.; Rooseleer, F.; Van Der Geest, P.; Heesbeen, B. Assessing the Severity of Wake Encounters in Various Aircraft Types in Piloted Flight Simulations. In Proceedings of the AIAA Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference, Grapevine, TX, USA, 9–13 January 2017; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, S.; Tittsworth, J.; Bryant, W.; Wilson, P.; Lepadatu, C.; Delisi, D.; Lai, D.; Greene, G. Progress on an ICAO Wake Turbulence Re-Categorization Effort. In Proceedings of the AIAA Atmospheric and Space Environments Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–5 August 2010; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- JO7110.659C; Wake Turbulence Recategorization. Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- RECAT-EU: European Wake Turbulence Categorisation and Separation Minima on Approach and Departure. EUROCONTROL: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. Available online: https://www.eurocontrol.int/publication/european-wake-turbulence-categorisation-and-separation-minima-approach-and-departure (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- CCAR-93TM-R6; Civil Aviation Air Traffic Management Rules. Civil Aviation Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).