Abstract

The use of nanomaterials (NMs) in 3D printing concrete (3DPC) has shown significant advancements in enhancing both fresh and hardened properties. This review finds that their inclusion in printable concrete has altered the rheological properties of the mix by promoting thixotropy, extrudability, and buildability while simultaneously refining the microstructure to enhance mechanical strength. Studies further highlight that these additives impart functional properties, such as the photocatalytic activity of nano-TiO2, which enables self-cleaning ability and assists pollutant degradation. At the same time, carbon-based materials enhance electrical conductivity, thereby facilitating the development of innovative and multifunctional structures. Such incorporation also mitigates anisotropy by filling voids, creating crack-bridging networks, and reducing pore interconnectivity, thereby improving load distribution and structural cohesion in printed structures. Integrating topology optimisation with 3DPC has the potential to enable efficient material usage. Thus, it enhances both sustainability and cost-effectiveness. However, challenges such as efficient dispersion, agglomeration, energy-intensive production processes, high costs, and ensuring environmental compatibility continue to hinder their widespread adoption in concrete printing. This article emphasises the need for optimised NM dosages, effective dispersion techniques, and standardised testing methods, as well as sustainability considerations, for adapting NMs in concrete printing.

1. Introduction

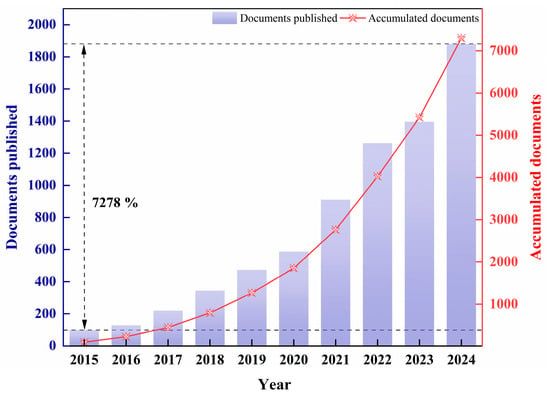

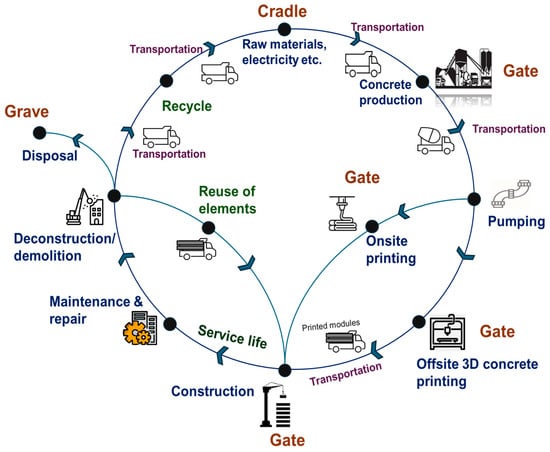

Additive manufacturing in construction, commonly referred to as 3D printing concrete (3DPC), has rapidly evolved from a niche research topic into one of the most disruptive innovations in civil engineering. Its promise of design freedom, material efficiency, reduced labor demands, and enhanced sustainability clearly distinguishes it from conventional concrete construction. Although industries such as pharmaceuticals, medicine, automotive, and aeronautics have already embraced additive manufacturing at scale [1,2,3,4], the construction sector is only beginning to unlock its full potential. Over the past decade, global research activity on 3DPC has increased dramatically, with publications expanding more than 72-fold between 2015 and 2024. As illustrated in Figure 1, this steep and continuous rise underscores the accelerating worldwide interest in 3DPC, in line with the scientometric trends reported by Wang et al. [5].

Figure 1.

Growth of publications on 3DPC in the Scopus database over the last decade.

3D printing is an automated additive manufacturing technique that fabricates three-dimensional objects from computer-aided design models, in which the 3D models are segmented into different two-dimensional layers and then laid down using printers to construct the intended model [6]. Extrusion-based layering (selective material deposition by extrusion) and powder-bed layering (selective binding) are the two main additive manufacturing techniques in the construction sector [7,8,9,10].

In the extrusion-based layering process, selected materials are deposited layer by layer using an extrusion print head, guided through computer-aided design tools, which direct the crane, robot, or gantry of a 3D printer equipped with six- or four-axis arms [8,9,11,12]. Examples of extrusion-based printing are contour crafting [13] and concrete printing [1]. The powder-based 3DPC is an additive manufacturing process that creates precise structures by depositing the binder liquid into a powder bed and generates detailed geometries through selective deposition, consolidating the powder upon contact with the bed. It is ideal for small-scale building elements, such as panels, formworks, and interior structures, which can be assembled on-site [14].

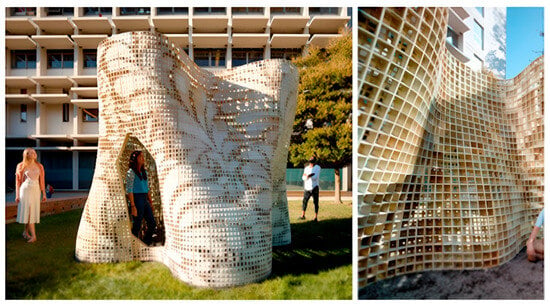

3D printing technology is being recognised as a pivotal component of the Fourth Industrial Revolution [15]. According to IndustryARC, the global 3D Printing in Construction market is projected to reach approximately USD 205.6 billion by 2030, growing at an unprecedented compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 113.7% during the forecast period 2024–2030 [16]. The demonstration by NASA of utilising 3D printing for building construction systems on the Moon and Mars highlights the capabilities of 3DPC [17], indicating that the world is ready to transition from conventional concreting to this emerging technology. Its adaptability is further demonstrated through architectural innovation, as shown in Figure 2, where the structural-aesthetic concept of the Bloom installation exemplifies the ability of 3DPC to produce complex, curved, and perforated geometries that merge structural efficiency with aesthetic expression. Collectively, such demonstrations highlight the advantages of 3DPC, such as eliminating formwork that typically contributes 35–60% of concrete cost [18], reduction of 30–60% in construction waste, reduction in labour cost by 50–80%, and cutting down the production time ranging from 50–70% [19]. Complementing these findings, case studies of structural wall printing have demonstrated cost reductions of 10–25% [19] and time savings of 30–50% [20]. These benefits, however, are not universal: gantry systems tend to be more efficient and cost-effective at the building scale due to their higher throughput, whereas robotic arms offer greater geometric flexibility for small-scale or complex elements but often at a higher per-unit cost. Such distinctions underscore the need to contextualise reported savings in 3DPC by system type and project scale. Additionally, printable concrete adheres to stringent structural imperatives, generates minimal waste, and achieves economic efficiency, positioning it as a forward-looking and responsible alternative to traditional concrete [3,4].

Figure 2.

The Bloom structural form, exterior and interior faces [21].

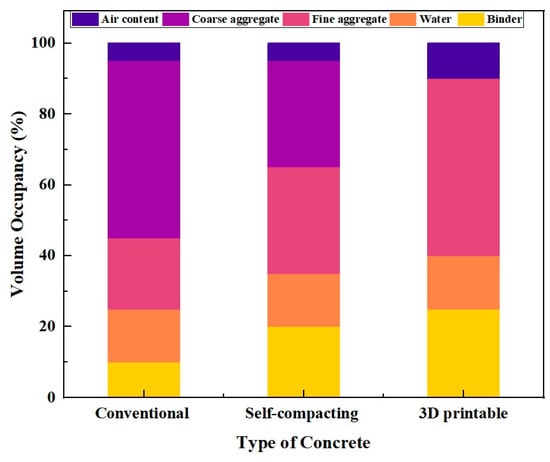

Despite several advantages, 3DPC has a few limitations. Introduction of coarse aggregate, resulting in multifaceted challenges [22], nozzle blockages, emergence of pores [23], impact of printing parameters on mechanical strength of printed specimen [24], lack of reinforcing methods [25], anisotropy [26] and more challenges like cold joints and interlayer bonding are major concerning factors in dragging additively manufactured concrete to establish it as a robust and reliable technique. For instance, Rahul et al. [27] and Chen et al. [28] utilized coarse aggregate in 3DPC and reported an aberration from desired rheological and mechanical properties. For these reasons, numerous researchers exclude the coarse aggregate and employ Portland cement along with fine aggregate shown in Figure 3, to achieve the optimal rheological and mechanical properties.

Figure 3.

A demonstrative comparison of the proportion of materials by volume consumed in traditional concrete, self-compacting concrete, and 3DPC. Modified from [23].

Limited literature [29,30,31,32,33] suggests that other hurdles, such as nozzle blockages and weak inter-transitional zones, can be addressed by developing suitable mix designs that consider factors like the appropriate water-to-cement ratio and aggregate-to-binder ratio. To assist the volume requirement criteria, the production of 3DPC involved the utilisation of a higher dosage of cement and fine aggregate compared to conventional and self-compacting concrete, which not only increases material consumption but also raises environmental concerns due to the associated carbon footprint. Consequently, 3DPC exhibits more air voids, primarily due to the absence of compaction during the layer-by-layer deposition process. Although the mix possesses inherent flowability to ensure extrusion and buildability, inadequate control of this property, combined with the lack of compaction, can lead to pore interconnectivity and weak interlayer bonding, ultimately reducing the mechanical performance of printed concrete [34].

Along with this, on the other side, there is a parallel pace in enhancing the rheological and mechanical properties of 3DPC by partially replacing cement with micro-sized materials such as silica fume [35,36], rice husk ash [37,38], fly ash [39,40], limestone calcined clay [41,42,43], ground granulated blast furnace Slag (GGBS) [44] and nano-sized particles like nano-clay (NC) [45], nano-silica (NS) [46], nano-titanium dioxide (NT) [47], and graphene oxide (GO) sheets [48]. Furthermore, in the investigation of the utilization of nano- and micro-sized particle materials in 3DPC [49], nanoparticles exhibited superior performance over microparticles demonstrating enhanced rheological, mechanical, and microstructural properties. This superiority is attributed due to the distinctive reactivity, small size, and expansive surface area of nanoparticles [50]. Nanomaterials (NMs) fill the pores in 3DPC and intensify the microstructural density [51]. Recent investigation by Li et al. [52] highlighted the significance of hydration kinetics and early-age microstructural development in determining the interfacial performance of 3D-printed cementitious materials, especially under varying ambient conditions and printing parameters. Following this, a study by Jinwhy et al. [53] demonstrated that the incorporation of hybrid nanomaterials, such as GO and NS, synergistically improved both toughness and crack resistance in 3DPC, owing to their combined effects of hydration nucleation and microcrack bridging. However, careful handling, precise dispersion, and optimal dosage of NMs are essential, as improper use can negatively impact the fresh and hardened properties of concrete. Additionally, a primary challenge associated with NMs lies in the higher production cost [54]. Nevertheless, prevailing research studies indicate that the combination of NMs and micro-sized materials in 3DPC can produce a synergistic effect, resulting in a composition that offers improved performance compared to using each material individually [55,56,57,58].

Currently, the demand for a material’s viability extends beyond its fundamental sustainability, necessitating a multifaceted approach that aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), given the increased environmental impacts, such as global warming and climate change. The construction sector contributes approximately 38% of greenhouse gas emissions, 40% of solid waste production, and 12% of potable water usage and is poised to tackle mounting environmental and socio-economic challenges. Due to the anticipated rise in urban populations, which is expected to represent 68% of the global population by 2050, it is imperative to enhance and adopt innovative, pioneering, and sustainable approaches to cater to the escalating needs for housing, transportation, and essential infrastructure [3]. In this context, there is an urgent need to develop a technology that, unlike traditional construction methods, can improve sustainability. Digital fabrication techniques appear to be a promising candidate, contributing significantly by satisfying 11 out of the 17 SDGs and aligning with broader global objectives for social and economic development. It suggests that 3DPC possesses a diverse range of qualities that make it environmentally sustainable [59]. Currently, the majority of the researchers are developing printable blends only with cement, fine aggregates, mineral and chemical admixtures. Therefore, a higher cement dosage of is essential compared to conventional concrete, acknowledging the elevated carbon dioxide emissions associated with cement production [60] which thereby intensify carbon footprints in the environment through 3DPC [61]. Incorporating a blend of supplementary materials in conjunction with cement presents a promising approach to achieving sustainable development in construction [62]. Sustainable alternatives like recycled powders and reactive fillers have demonstrated potential in reducing the carbon footprint of 3D-printed construction, while maintaining comparable mechanical properties [63]. Furthermore, alternative printable mixes developed by geopolymer as a binder [64], alkali-activated material [65] also provide a viable solution for sustainable construction. Nonetheless, the current study focuses on an in-depth exploration of performance of NMs used in 3DPC, where cement is used as a binder system.

Recent reviews [51,53,66] have significantly contributed to the understanding of NMs in 3DPC, particularly about rheological behaviour, early-age hydration kinetics, and the evolution of interfacial zones that govern printability and mechanical fidelity. These efforts have provided foundational insights into the influence of nanoscale additives on flow characteristics, build stability, and mechanical strength, highlighting the importance of material–process interactions. As 3D printing transitions from formulation development to structural-scale implementation, however, a broader and more integrated perspective is required—one that aligns nanoscale functionalities with macrostructural performance targets, long-term durability, and sustainability objectives. Alongside these considerations, the safe handling of NMs requires careful attention to detail. Due to their ultrafine particle size and high surface reactivity, nanoparticles can become airborne during mixing, posing potential risks of inhalation, dermal contact, and long-term health effects.

Overall, 3DPC represents a rapidly advancing frontier in civil engineering, offering unparalleled design flexibility, reduced labour intensity, faster construction, and measurable sustainability benefits. Nevertheless, its large-scale deployment is still constrained by challenges such as rheological instability, weak interlayer bonding, nozzle blockages, and high cement demand. To address these limitations, extensive research has focused on incorporating NMs and supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). NMs, in particular, have proven to be highly effective modifiers, capable of improving fresh-state performance through rheological tuning and hydration acceleration, while also enhancing hardened-state strength and durability via pore refinement and microstructural densification. Although challenges such as higher cost and dispersion difficulties persist, the hybrid use of NMs with SCMs demonstrates strong potential to elevate both fresh and hardened properties of 3DPC.

Furthermore, the methodology for this review was based on a structured screening of peer-reviewed studies that investigate the role of NMs in 3DPC. The literature was identified using Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, with the search restricted to English-language publications. Because NM integration in 3DPC is a relatively new field, no strict time window was imposed; however, emphasis was placed on studies from the last decade to capture the most relevant developments. Inclusion criteria covered experimental and review papers that addressed the influence of NMs on rheology, hydration, mechanical, durability, or sustainability aspects of 3DPC. Exclusion criteria were non-peer-reviewed sources, patents, and grey literature. The final pool, therefore, comprised peer-reviewed articles and select conference papers from established publishers in the fields of construction materials, cement science, and additive manufacturing. Evidence was synthesised qualitatively and comparatively to highlight consistent performance trends across NM classes, while recognising that quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible due to variation in mix design, testing protocols, and performance metrics. This approach ensured that the review provides a transparent basis for claims such as rapid publication growth (Figure 1) and comparative assessments of different NM classes.

The present paper provides a comprehensive review of the effect on the rheological, mechanical, and microstructural performance of 3DPC modified with NMs. In the first segment, the role of NMs in enhancing the properties of concrete through various mechanisms, including the filler effect, alterations in hydration kinetics, and microstructural densification, is discussed. It is followed by offering a detailed understanding of fresh and hardened parameters of 3DPC, providing an overview of the material’s behavioural dynamics. In the subsequent sections, an in-depth analysis is presented on the impact of NMs on the overall properties of 3DPC, with an emphasis on the synergistic effects when combined with other SCMs and fibres. Furthermore, the study examines the potential of NMs in promoting sustainable construction practices, with a focus on their adaptability within the emerging field of 3DPC. The studies conclude by examining the role of topological optimisation in enhancing sustainability, emphasising its potential to reduce material usage.

2. Nanotechnology in Cementitious Composites: Influence on Hydration Kinetics, Mechanical Strength and Microstructure

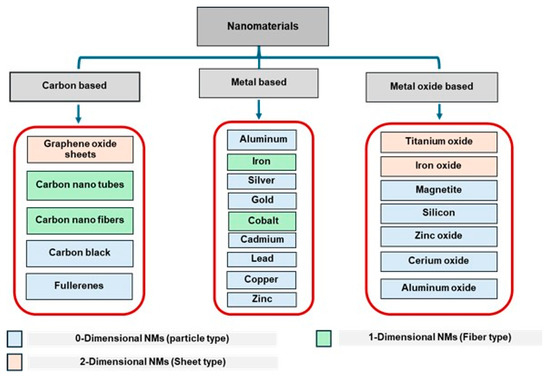

The concept of nanotechnology was first introduced by the renowned physicist Richard Feynman in 1959 through his talk “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” at the American Physical Society meeting at the California Institute of Technology. In his presentation, he emphasised the capabilities of manipulating and governing matter on a microscopic scale, exploring the ramifications and opportunities presented by miniaturisation and nanoscience [67]. After fifteen years, in 1974, another physicist, Taniguchi, coined the term “nanotechnology” [68]. Sobolev et al. [69], disclosed that all materials can be converted to nanoparticles. The effectiveness of nanoparticle formation lies in its ability to impact the purity or fundamental chemical composition of the parent materials. Top-down and bottom-up are the two primary approaches generally used for the synthesis of NMs. In the top-down approach, the bulk material is sliced to create nano-sized particles, whereas in the bottom-up approach, molecules are combined to form larger structures, such as atoms [70,71]. In concrete applications, NMs synthesised through a bottom-up approach are preferred, as they offer precise control over particle size, morphology and specific properties [72]. Figure 4 further classifies the NMs used in concrete based on their composition and dimensional structure, providing a detailed overview of these materials. Figure 5 illustrates their morphology and surface characteristics.

Figure 4.

Classification of NMs that are used as a common additive in the conventional and 3DPC according to material composition and by their dimensionality criterion.

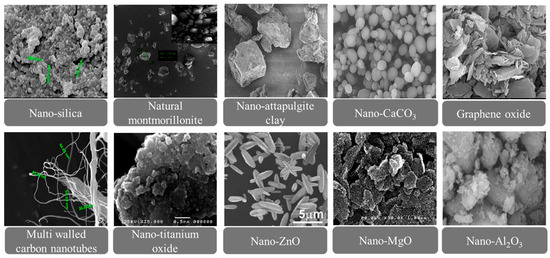

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrographs of various NMs illustrating their morphology and surface texture for use in concrete applications [73,74,75,76].

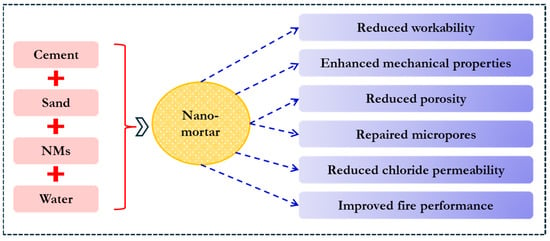

NMs, when incorporated into concrete, modify its fresh and hardened behaviour by influencing workability, strength development, durability, and high-temperature resistance, as schematically represented in Figure 6. Active NMs, such as NS, NC, nano-metakaolin, and nano-Al2O3, play a pivotal role in influencing the cement hydration reaction. Remaining inert nanoparticles, such as graphene nanoparticles (GNPs), carbon nanofibres (CNFs), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), GO, NT, nano-Fe2O3, and nano-ZrO2, serve as nucleation sites for the precipitation of C-S-H, thereby filling the pores and impeding the formation of microcracks within the concrete matrix [75]. Land and Stephan’s [77] experimentation results also showed that it is possible to accelerate or control the kinetics of cement hydration in multiple ways with the addition of NMs.

Figure 6.

Commonly employed materials in the production of nano-mortar and the enhanced characteristics of mortar by adding NMs. Modified from [78].

Typically, the C-S-H gel mainly forms around clinker particles, filling the gaps between them. However, the introduction of C-S-H seeds into the mixture encourages the further growth of C-S-H across the cement matrix, not just surrounding the clinker particles. This seeding procedure yields a more uniform and compact distribution of C-S-H, thereby reducing porosity and densifying the concrete’s microstructure [79].

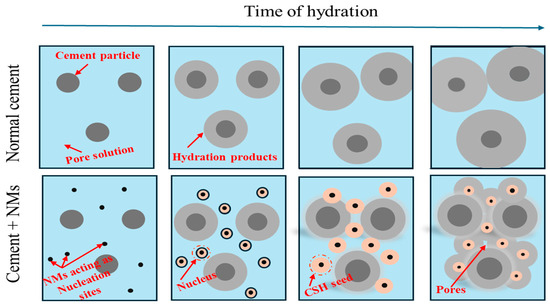

The evolution of microstructure with hydration time in the plain and NM-integrated concrete matrix is depicted in Figure 7. Additionally, some NMs, such as NS, nano-metakaolin, and nano-fly ash, will also form more C-S-H through active pozzolanic reactions and contribute to the improvement of overall mechanical strength. To improve the rheological, mechanical, and microstructural performance of concrete through the addition of NMs to the concrete blend, researchers have begun utilising NMs in printable concrete to enhance the properties and performance of the printed structures.

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration comparing the evolution of microstructure with respect to time of hydration in a concrete matrix with and without NMs. Modified from [80].

According to Deyu et al. [81], the nucleation effect occurs when a critical ion concentration is reached before the formation of a crystal nucleus and crystal growth in a saturated solution, as described in the classical theory of crystallisation. It represents the stage known as nucleation control in the homogeneous nucleation process of numerous chemical reactions. The utilisation of NMs introduces heterogeneous nucleation, which effectively reduces the critical ion concentration required for nucleation to occur, thereby facilitating rapid crystal growth on the NM surface. For developing ideal cementitious composites modified with NMs, efficient dispersion is necessary due to their small size and high specific surface area, which makes them easily susceptible to agglomerating as clusters in the blend. Therefore, meticulous attention to dispersion methods, such as physical, chemical and physical-chemical, is required [66]. The zeta potential has a significant influence on the electrostatic stability of the colloidal system and governs the dispersion’s resistance to agglomeration. Dispersions exhibiting zeta potential values under ±30 mV are susceptible to quick coagulation and agglomeration due to inadequate electrostatic repulsion. Ultrasonication, a method that utilises cavitation microbubbles to disintegrate agglomerates, is a practical approach to enhance dispersion. Furthermore, adjusting the suspension’s pH and applying dispersion strategies, such as the use of surfactants and superplasticisers, can significantly improve stability [82].

Beyond their role in modifying hydration kinetics and microstructure, NMs also provide multifunctional enhancements that directly address the limitations of traditional SCMs, particularly in 3DPC. These materials have emerged as critical modifiers in 3DPC, addressing durability deficiencies stemming from directional porosity and weak interfacial zones formed during layer-by-layer deposition. Compared to traditional SCMs such as fly ash and silica fume, which are typically added at high dosages (15–30%) and often increase long-term porosity by ~12% while delaying hydration onset, NMs operate more efficiently at significantly lower dosages (0.5–3%) by directly engaging with microstructural degradation mechanisms at the nanoscale through their nucleation potential, filler effects, and chemical reactivity, NMs promote dense hydration products, reduce ion permeability, and fortify weak zones in the matrix and at interlayer interfaces. NS, incorporated at just 1–3% by binder weight, accelerates secondary C-S-H gel formation, thereby reducing chloride diffusion coefficients by 50.8–54.4% and mitigating sulphate-induced mass loss by 16–20% through pore refinement and ion transport resistance [83]. In contrast, silica fume, although reactive, increases paste viscosity and requires up to 20% more super-plasticiser to maintain printability, often complicating rheology in extrusion-based systems [53].

In addition to NS, NT offers multifunctional durability enhancements. At 1–1.5% by cement weight, it reduces average pore diameters from ~100 nm to <50 nm, lowering total porosity by 20–35% and improving chloride resistance by ~30% in ultra-high-performance concrete under flexural stress [84]. Moreover, its photocatalytic activity enables 65–80% NOx degradation under UV exposure, providing self-cleaning and surface protection in polluted environments [85]. These functionalities are not available in conventional SCMs. GO, even at ultralow dosages (0.06%), forms a hydrophobic, crack-bridging nanonetwork that reduces water absorption by a factor of four and enhances freeze–thaw durability by 68.75%, cutting mass loss from 0.8% to 0.25% across 540 cycles [86]. GO’s intrinsic electrical conductivity also supports real-time structural health monitoring, positioning it as a multifunctional additive that far exceeds the capabilities of traditional pozzolans.

The integration of NMs into cementitious composites has revolutionised the design and performance of both conventional and 3DPC. NMs, even at ultra-low dosages, fundamentally enhance hydration kinetics, densify the microstructure, and improve durability by acting as nucleation sites, promoting pozzolanic reactions, and refining pore structure. These additives accelerate C-S-H gel formation, reduce permeability, and impart advanced functionalities, such as self-cleaning and real-time structural monitoring, which are not achievable with traditional supplementary cementitious materials. However, the exceptional reactivity and high specific surface area of NMs demand meticulous dispersion strategies (e.g., ultrasonication, surfactants) to prevent agglomeration and ensure uniform performance gains. Thus, nanotechnology offers a transformative pathway for next-generation concrete, contingent upon precise control of NM dispersion and integration within the cement matrix.

From the above studies, it is clear that the addition of NMs to concrete may enhance its performance by modifying hydration kinetics, microstructural development, and durability. They can act as pozzolanic agents and form additional C-S-H; they can also serve as nucleation sites, promoting heterogeneous crystallisation and densification of the cement matrix. However, dispersion stability, influenced by zeta potential and methods such as ultrasonication, ensures a homogeneous distribution and prevents agglomeration that could undermine the nanoscale mechanisms.

3. Fresh and Hardened Properties of 3DPC and the Role of NMs

3.1. Fresh Properties

Concrete designed for 3D printing requires a delicate balance between high consistency and pumpability. In contrast, the slump test, widely used to assess the workability of traditional concrete, often falls short in detecting subtle variations critical to the performance of printable concrete [87]. Rheological properties in printable concrete offer a more detailed and sensitive characterisation of material behaviour compared to slump tests. However, their assessment typically involves specialised and costly equipment. Although fresh concrete can be readily extruded, its workability or open time for printing is often limited compared to conventional applications [33,88,89]. As viscosity increases over time, workability decreases until the material becomes more rigid, making it suitable for extrusion. Despite the challenges posed by this stiffening, it can enhance the mechanical strength of the initial layers, thereby supporting the ones that follow. Therefore, rheological measurements are vital for assessing the casting properties of fresh concrete, including workability, flowability, and printability [87].

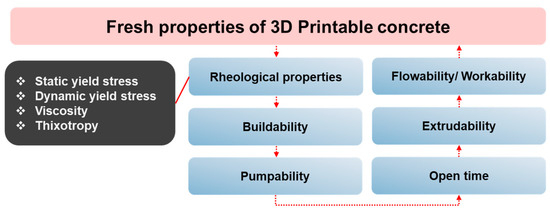

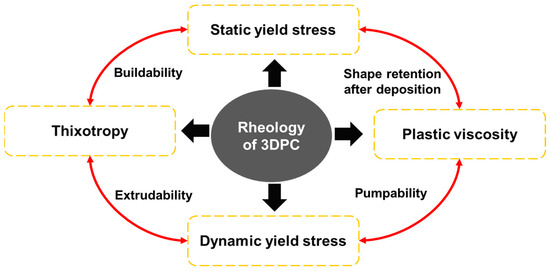

Furthermore, Prolonged pauses during printing may result in cold joints with weaker bonds between layers. Nevertheless, a structured approach [90] was developed to evaluate pumpability and buildability using slump and slump-flow tests, helping to identify mixtures suitable for 3D printing. Mixes with slump values of 4–8 mm and a slump flow of 150–190 mm were found to provide sufficient buildability and a smooth surface. To illustrate these parameters within the broader context of material behaviour, the classification of fresh properties relevant to 3DPC is presented in Figure 8. Fresh performance in 3DPC is governed by the balance between static yield stress, dynamic yield stress, viscosity, and thixotropy, which together control pumpability, extrudability, buildability, and open time. Slump/slump-flow values only provide entry into the printable window, while interlayer bonding ultimately depends on time-dependent structuration and surface moisture evolution.

Figure 8.

Key fresh properties of 3DPC based on material characteristics.

3.1.1. Flowability

The concept of flowability in 3DPC refers to the ability of the material to deform and be conveyed through the system under pressure while retaining key rheological properties such as yield stress, plastic viscosity, thixotropic recovery, cohesion, and early-age (green) strength during the open time window [11]. If the printable mix possesses high flowability, it is more likely to act as a fluid and adversely affect buildability. Conversely, if the mix is too stiff (i.e., low flowability), it isn’t easy to print. Although there is no standard code for the flowability range, a previous study [91], suggested that the mix with a flowability range of 160–200 mm is optimal for printing.

Mechanistically, it reflects how particles within the mix move and rearrange under applied energy. Smooth and spherical particles, such as fly ash, improve flow due to reduced interparticle friction, whereas angular or ultra-fine particles like silica fume, nano-clay, and metakaolin increase water demand and reduce spread. Fibres further restrict flowability by entangling within the mix, although their effect can vary depending on the type and dosage of the fibre. Chemical admixtures strongly influence this property: superplasticisers increase flow by dispersing cement grains, while viscosity-modifying agents decrease spread but enhance stability. The water-to-binder ratio is another key factor, where higher ratios promote ease of flow but risk segregation, while lower ratios stiffen the mix. Due to these combined effects, flowability must fall within a narrow optimum range; too low leads to nozzle blockage and poor extrusion, while too high causes loss of shape and instability in deposited layers.

3.1.2. Buildability

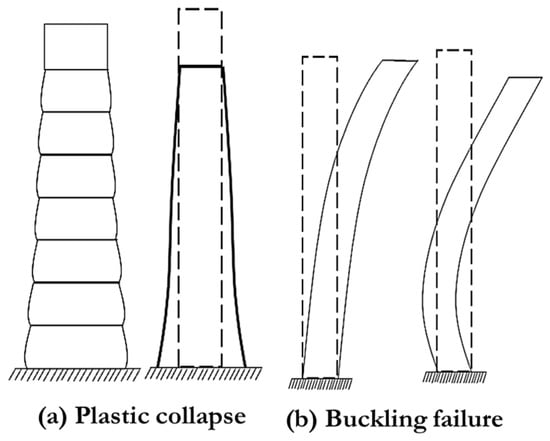

Buildability refers to the capability of an extruded material to uphold its form and size even when subjected to continuous and escalating loads caused by the deposition of subsequent layers [92]. It relies on the yield stress of the material, the structural build-up, and the stability of the shape. The initial rigidity is guaranteed by the static yield stress, which ensures that the shape is retained after extrusion before the structural build-up process commences [33,93]. The structural build-up is affected by factors such as flocculation and binder hydration rates [94]. If the material is deposited faster than it builds up, the structure will fail [33]. Buildability failure in 3DPC can occur either through plastic collapse, where stresses exceed the evolving yield strength of fresh concrete, or through elastic buckling, which is governed by material stiffness and elastic modulus in the fresh state [95]. These two primary failure modes are illustrated in Figure 9. There is no standardised test for buildability. However, researchers evaluated buildability by counting the number of printed layers [96], performing a layer deformation test [29], and a cylinder stability test, among others. Perrot et al. [33] analysed the relationship between buildability and static yield stress in layer-by-layer concrete printing using the rheological modelling Equation (1) to determine the optimal balance for structural stability and predict failure.

where H (m) is the buildability, α is the geometric factor of the printed structure, is the density of materials (g/cm3), and g (m/s2) is the acceleration due to gravity. (Pa) is the static yield stress. Reported thresholds suggest that plastic collapse can be avoided when the slenderness ratio, defined as the total build height (H) divided by the single-layer thickness (τs), is kept below ~3–4. At the same time, elastic buckling can be controlled by maintaining an applied stress ratio of τ/τs < 1. These dimensionless criteria provide practical limits for defining safe print rates and maximum layer heights in extrusion-based 3DPC.

Figure 9.

Buildability failure criteria in slender structural elements: (a) plastic collapse due to progressive yielding and (b) buckling failure showing lateral instability under axial loading [95].

3.1.3. Extrudability

Extrudability is attributed to how well a printable mix can maintain its dimensional accuracy and layer quality while being continuously extruded through the nozzle [97,98]. Accurate structures are dependent on proper extrusion. To measure this, one can print with fresh material and assess the length without any breakage of printed filament or blockage of the nozzle. Longer uninterrupted length is indicative of superior extrudability [95].

Further, this property is not merely concerned with the passage of material through the nozzle, but with the efficiency and continuity of that process under the operational demands of digital construction. The rheological state of the mix is decisive: excessive viscosity or yield stress leads to elevated resistance and potential blockages, while insufficient cohesion results in filament collapse, tearing, or spreading. Extrudability is also governed by the synchronisation between pump discharge and printhead motion; even minor discrepancies can manifest as discontinuities, nozzle clogging, or buckling of the deposited strand. In this sense, extrudability embodies a coupled response of material formulation and process mechanics, where the cohesion of the cementitious matrix and the external energy input must be meticulously balanced. Achieving robust extrudability is therefore critical not only for maintaining uninterrupted flow but also for ensuring precise filament geometry, uniform interlayer adhesion, and the dimensional fidelity of the printed structure.

3.1.4. Pumpability

Pumpability refers to the ease with which a printable mix is pumped smoothly through a conduit under pressure and reaches the desired printing location while ensuring its functionality and avoiding segregation [99]. Pumpability is typically assessed indirectly by examining rheological properties, which collectively determine the mix’s ability to be pumped efficiently. For ideal pumpability, the viscosity needs to be reduced, while the static yield stress should be increased post-extrusion to enhance buildability. Pumpability in printable concrete should be considered in conjunction with its buildability to ensure a smooth flow through the pump and nozzle while maintaining shape and structural integrity after deposition [100]. In addition, Pumpability, extrudability, and buildability are categorised as the fundamental printable performance criteria for printable concrete [101].

3.1.5. Open Time

In 3DPC, open time refers to the period when the material flows smoothly through the nozzle without any blockages or clogging [102]. The printable mixture must have an open time that exceeds the extrusion time to ensure optimal printability [23]. The test methods employed to assess flowability can also be used to determine the open time of the mixture by examining the flow over time [95]. Furthermore, the cessation of open time is recognised through disruptions in extruded filaments, such as decreased filament width and gaps, which suggest challenges in material extrusion caused by elevated yield stress, leading to blockages in the nozzle [23].

3.1.6. Rheological Properties

The construction material industry introduced rheology to evaluate the initial flow characteristics of materials with composite properties for concrete. Rheology quantitatively analyses and evaluates material characteristics and phenomena, providing a numerical representation of the quality and performance of composite materials in 3D concrete printing [103]. It affects both the fresh state behaviour and mechanical characteristics of the printed structure; therefore, a thorough comprehension and management of rheological parameters, which include yield stress, plastic viscosity, thixotropy, structuration rate, and flocculation rate, are essential to guarantee the production of high-quality, structurally sound printed concrete elements [23,95].

Yield stress is a fundamental rheological property that determines the material’s capacity to maintain its shape after extrusion and impacts the ease of flow during printing. The time-dependent increase in yield stress of fresh concrete is driven by internal structuration and C-S-H formation, which is critical for maintaining the stability and geometrical accuracy of printed structures [101]. Static and dynamic yield stresses are the two types of yield stresses involved in 3DPC. Static yield stress is the minimum stress needed to initiate flow, while dynamic yield stress maintains flow. Higher static yield stress and lower dynamic yield stress are desirable for maintaining buildability and pumpability. Studies [104,105], suggests that an optimal yield stress range of 500 to 2500 Pa is appropriate for 3DPC, with the precise value depending on the specific printing technology and operational conditions. Perrot et al. [33] developed a model (Equation (2)) to describe the increase in yield stress over time, considering the structuration rate and time-dependent nature of yield stress, which is not directly a flow model but rather a structuration model. Initially, the strength of concrete increases steadily with age, then shifts to a rapid rise in later stages.

where is the structuration rate, is the yield stress at = 0, and is the curve-fitting parameter derived from experimental data.

Thixotropy is a reversible rheological behaviour exhibited by printable concrete. When an external shear force is applied, the concrete loses its flocculated structure and starts to flow. Upon the reduction or removal of the shear force, the concrete ceases to flow, and the particles begin to flocculate again due to interparticle interactions. This process restores the static yield stress of the mix. Thixotropy describes the material’s ability to transit between a fluid-like state when sheared and a solid-like state when the shear is reduced or removed, ensuring the concrete can be easily shaped during extrusion and regain its strength afterwards [91]. The behaviour of concrete can be assessed through experimental tests, such as hysteresis loops, incremental variations in shear rate or shear stress, dynamic moduli, and start-up or creep tests [106]. Kruger et al. [107] developed a novel analytical model where they presented a bi-linear thixotropy model, incorporating indices such as Rthix (Re-flocculation rate) and Athix (Structuration rate/Structural build-up rate) further reported that Rthix in particular is significant because it measures the material’s ability to regain its internal structure after shear quickly, ensuring stability and facilitating the addition of new layers, which is essential for maintaining the integrity of the printed structure throughout the building process.

Plastic viscosity (μp) is another notable rheological property of printable concrete, referring to the additional shear stress required to increase the flow rate [108]. It is essential for a seamless 3D printing process and for maintaining the structural integrity of the material after it has been extruded. Rotational rheometers are used to measure it, working in conjunction with yield stress to describe the overall rheological behaviour of printable concrete in its fresh state [91].

The rheological behaviour of 3DPC is typically characterised using the Bingham plastic model, as described in Equation (3), which considers concrete as a Viscoplastic material. This model is widely used by many researchers due to its simplicity [109]. However, the Herschel–Bulkley model in Equation (4) and the Power-law model in Equation (5) can also be utilised to determine the yield stress and plastic viscosity of printable concrete. Prem et al. [110] validated the three models mentioned above. They reported that all models adequately predicted the rheological properties of printable mixes with components such as NS, Polyvinyl alcohol fibres, and fly ash. Furthermore, the authors suggested that further studies are needed to identify the most suitable model to reduce extensive experimentation. In practical terms, printable mortars exhibit shear-thinning and time-dependent behaviour. For simpler binder-rich mixes, the Bingham model remains adequate; however, at higher shear ranges or in NM-modified pastes, the Herschel–Bulkley model generally provides a more reliable description of the flow response.

where is shear stress, is yield stress, μp is plastic viscosity, is the shear rate, and n is the flow index.

To maintain structural integrity, the internal structural buildup of the lower layer must be greater than the stress due to the gravitational load or self-weight of the upper layer, which is printed or about to be printed; otherwise, the layers will settle and lead to collapse. Together, these rheological parameters determine the fresh-state performance of 3DPC, linking fundamental material behaviour to practical outcomes such as pumpability, extrudability, buildability, and shape stability. This relationship is conceptually illustrated in Figure 10. Higher shear rates during pumping reduce thixotropy, improving interlayer wetting, while resting rebuilds structure and increases static yield stress for buildability. This feedback explains why pauses promote cold joints, and why superplasticiser dosage, shear history, and curing directly tune interlayer bond strength.

Figure 10.

Conceptual framework of fresh performance of 3DPC.

In NM-enhanced 3D printable cementitious systems, hydration begins almost immediately after mixing due to the presence of highly reactive NMs such as NS, NC, and nano-calcium carbonate (NCa). These additives act as nucleation sites, significantly accelerating the formation of C-S-H and reducing the induction period of cement hydration. This early-age acceleration leads to swift structural build-up and increased matrix cohesion, both of which are critical for maintaining geometric fidelity during the layer-by-layer printing process [47]. These materials also enhance thixotropy by promoting reversible flocculation, allowing the material to flow under shear during extrusion but rapidly regain stiffness after deposition, thus supporting the stability of subsequent layers [53]. Quantitative assessment of these effects involves both conventional tests (e.g., mini-slump, flow table) and advanced rheometric techniques that provide detailed insights into yield stress, plastic viscosity, and thixotropic index. Uniform dispersion, typically achieved using ultrasonication or high-range water reducers, is crucial for maximising nanoparticle effectiveness and preventing agglomeration [51]. Overall, tailoring nanomaterial content and dispersion strategies enables precise control over fresh-state properties, directly translating into improved printability, structural integrity, and process reliability in 3DPC.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

Typically, 3DPC exhibits the same mechanical properties as conventional cast concrete, including compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, modulus of elasticity, and fracture energy, which collectively define its load-bearing capacity and durability. These properties are typically evaluated using standardised tests and are influenced by mixture design, curing conditions, and age. However, due to the layer-by-layer deposition process, 3DPC also develops distinctive properties not present in cast concrete, most notably interlayer bond strength, which is crucial in ensuring structural integrity. If not adequately managed, weak interlayer bonding can lead to the formation of cold joints. But there are no existing norms for testing this property [95]. Researchers determine interlayer bond strength by applying a tensile load perpendicular to the deposited layer [8], using two loads in opposite directions (longitudinal) on the deposited layers [111], and a split tensile test [112]. Few researchers [8,113] have found that interlayer bond strength is closely associated with the printing time gap and the amount of moisture available on the surface. With the increase in the printing gap, the tensile bond strength will decrease.

The anisotropic mechanical response of 3DPC is a direct consequence of its manufacturing process. Unlike cast concrete, which can often be approximated as isotropic at the macroscale, extrusion-based printing produces a laminated microstructure where filaments are deposited sequentially. This results in three orthogonal material directions: along the filament axis, perpendicular within the filament plane, and across the build height. The microstructure introduces weak planes at interlayer interfaces due to incomplete hydration, surface moisture loss, and thixotropic structuration in the resting layer. Consequently, stiffness, strength, and fracture resistance vary with orientation, making 3DPC an orthotropic quasi-brittle material rather than an isotropic one.

Weng et al. [112] experimentally demonstrated this by studying how process parameters affect hardened properties and interlayer adhesion. They showed that compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths are consistently lower when loads are applied perpendicular to the layer interfaces, where debonding dominates failure, compared to loading parallel to filaments. This confirmed that print orientation directly influences peak load, stiffness degradation, and crack patterns, and therefore cannot be ignored in structural analysis.

To capture these effects, Mader et al. [114] developed the 3DPC damage–plasticity model, an orthotropic extension of the widely used Concrete Damage Plasticity framework. The model explicitly accounts for direction-dependent stiffness and strength by defining nine independent elastic constants aligned with the print directions, together with orthotropy parameters calibrated from mechanical tests in different orientations. A novel stress-mapping procedure enables the projection of anisotropic stresses into an equivalent isotropic configuration, preserving computational efficiency while incorporating directional dependence. The constitutive law further combines anisotropic plasticity with a gradient-enhanced damage formulation, which ensures mesh-objective simulation of softening and crack localisation. Validation against uniaxial compression and three-point bending tests with varied print orientations showed that the model successfully reproduces directional yield surfaces, anisotropic strength envelopes, and interface-driven cracking modes.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that orthotropy in 3DPC is not a secondary feature but a defining mechanical characteristic. Its origin lies in the microstructural anisotropy and interlayer bonding mechanisms, while constitutive frameworks such as the 3DPC damage–plasticity model provide the scientific foundation for predictive design. Neglecting this anisotropy risks unsafe overestimation of ductility and capacity, especially under stresses perpendicular to layer interfaces.

Having established the fresh and hardened performance requirements of 3DPC in Section 3, Section 4 investigates how different classes of nanomaterials such as Nano-silica, Nano-clay, calcium carbonate, carbon-based nanomaterials, and Nano-titanium dioxide (TiO2) modify these properties and contribute to improved performance.

4. Influence of NMs on Fresh and Hardened Properties of 3DPC

4.1. Nano-Silica

Numerous studies have investigated the incorporation of silica nanoparticles in conventional and 3DPC, consistently highlighting their ability to enhance both rheological properties and mechanical performance. The superior pozzolanic reactivity of NS enables it to alter the hydration kinetics, offering significant benefits for the long-term performance of cementitious materials. According to Senff et al. [115], the presence of NS accelerates hydration by establishing nucleation sites for the precipitation of the C-S-H gel, thereby leading to potential modifications in the static yield stress due to variations in initial hydration reactions and the physical characteristics of the system. Specifically, NS provides a significantly larger surface area for hydration reactions compared to traditional cement particles, thereby enhancing the rate and extent of C-S-H gel formation, which results in a more compact microstructure and a reduction in pores. These findings are supported by Quercia et al. [116], who emphasised that the higher surface area of NS, coupled with its function as a nucleation site, pivotal in the transformations witnessed within cementitious systems; these modifications affect the hydration kinetics, which in turn influence the static yield stress of fresh concrete.

Qiang et al. [117] investigated the effects of various mineral admixtures, including fly ash, ground slag, silica fume, NCa, attapulgite, and NS, on the rheological properties and structural development in cement pastes. They reported that NS has shown better rheological behaviour, significantly improving C-S-H formation, static yield stress, and overall performance compared to other additives, such as silica fume, fly ash, and ground slag. At optimal dosages (1–2%), NS demonstrated superior mechanical efficiency and hydration kinetics, particularly at lower w/c ratios. Oscar et al. [46] evaluated the influence of NS, micro silica, metakaolin, and nano-calcium carbonate in 3D printable cement pastes. In their experimental study, NS outperformed all other materials due to its enhanced buildability, smooth extrusion and higher thixotropy. Additionally, both NS and NC reduced pore volume by up to 16.2% and increased the hydration product volume fraction by 4.3%. This progressive improvement in buildability with increasing NS content is further illustrated in Figure 11, where the inclusion of NS markedly enhanced layer stability and vertical shape retention. Notably, the mix with 1% NS achieved a 133% increase in the number of printable layers compared to the reference mix without NS, demonstrating significantly higher build heights and improved overall structural integrity as the dosage of NS increased [118].

Figure 11.

Buildability of printed elements with increasing NS content. Modified from [118].

Kruger et al. [119] developed a thixotropic model that incorporates re-flocculation and structuration rates to assess the suitability of the material for 3DPC. Rapid re-flocculation is crucial for maintaining the material’s shape immediately after deposition, thereby enhancing its strength after extrusion. The structuration rate quantifies the increase in static yield stress over time, driven by chemical processes such as the formation of ettringite needles. The incorporation of NS enhances re-flocculation, thereby improving buildability without sacrificing structural integrity; however, an excess of NS may negatively impact thixotropic behaviour. The research highlights the importance of optimising the dosages of NS and superplasticisers to expedite the development of static yield stress, ensuring quicker structural stability and facilitating higher printing speeds. A comparative analysis of existing rheological models, including the Bingham, Herschel–Bulkley, and Power-law models, was conducted by Prem et al. [110] to identify the most suitable prediction model. The study investigated the effects of varying dosages of nano-silica, polyvinyl alcohol fibres, and fly ash on the mix’s flow characteristics. All models provided valuable insights into the rheological behaviour of mixes, with the Herschel–Bulkley model offering slightly higher reliability. Nonetheless, the study highlights the need for continued refinement of these models to further enhance their accuracy and relevance for diverse 3D concrete printing applications.

Jacques et al. [120] studied the effects of silica and silicon carbide nanoparticles on high-performance 3D printable concrete. The addition of NS reduced re-flocculation rates by nearly 48% and structuration rates by 33%, while silicon carbide achieved reductions of 42% and 24%, respectively. The highest compressive strength of 80.3 MPa was observed at 1% NS, while 2% yielded the best flexural strength of 9.2 MPa, with higher dosages leading to diminishing returns. Silicon carbide exhibited inconsistent trends in compressive strength, and while NS increased stiffness, silicon carbide caused slight reductions in Young’s modulus. Both nanoparticles enhanced buildability and thixotropy, but silicon nanoparticles showed superior improvements in structural stability during printing. Another study [121] was conducted by adding nano-SiC and reported that the continuous addition of nano-SiC significantly increased both static and dynamic yield stresses, reaching peaks of 6483 Pa and 2803 Pa, respectively, indicating improved initial resistance to deformation. However, the re-flocculation and structuration rates decreased with higher nano-SiC content, dropping to 4.2 Pa/s and 0.61 Pa/s, respectively, indicating a reduced ability of the cement paste to rebuild its internal structure after shearing, which leads to diminished thixotropic behaviour. Mechanical properties, such as compressive and flexural strengths, reached their peak at a 3% nano-SiC addition. Scanning electron micrograph analysis revealed that nano-SiC effectively reduced microstructural voids and crystal sizes, resulting in a denser microstructure and improved mechanical performance.

Beyond rheology and buildability, NS also influences anisotropy in 3DPC. Qian et al. [122] reported that compressive strength varied between cast specimens and those printed in the X- and Z-directions, confirming the anisotropic nature of 3DPC. They attributed this directional dependence to interlayer bonding and filament alignment and further showed that even at low dosages (0.5–1%), NS, particularly when combined with polypropylene fibres, significantly reduced the anisotropic coefficient. These findings highlight the dual role of NS in improving material performance while also emphasising the need to optimise mix design and printing strategies to minimise strength variations across different orientations. These findings highlight the dual role of NS in improving rheological stability, buildability, and anisotropy reduction in 3DPC. However, its performance is highly dosage-dependent: studies consistently report an optimal range of ~1–2% by weight of binder, where buildability and strength gains are maximised [117,120], and mixes achieve up to 133% increases in printable layers [46]. At higher dosages, however, NS increases viscosity, reduces thixotropy, and raises superplasticiser demand, leading to workability loss and extrusion instability [119,120]. To provide clarity for researchers and practitioners, the main advantages and limitations of NS in 3DPC are consolidated in the following practical guidance.

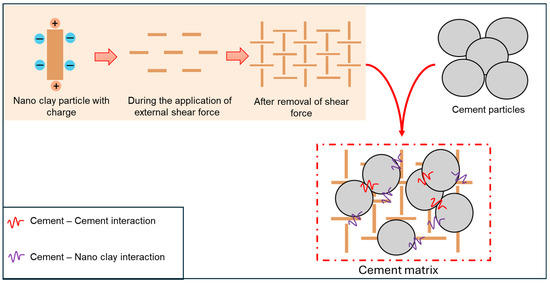

4.2. Nano-Clay

Nano-clays, which are nanoparticles of layered mineral silicates such as montmorillonite, bentonite, and kaolinite, exhibit unique properties including high chemical reactivity, stability, and significant hydration and swelling capacity due to their platelet structure (≈1 nm thick, 70–150 nm wide). They form interactions with cement particles to create a dense microstructure [123]. During shear, Van der Waals bonds break but can reform after deposition; this can cause a long structural recovery time; adding NC strengthens particle interactions because of its charged edges and thixotropic behaviour, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Behaviour of NC particles during and after the removal of external shear force with time. Modified from [124].

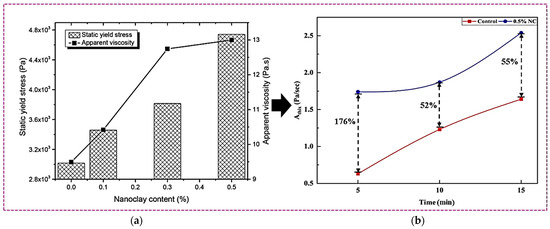

The thixotropic effect of NC is further confirmed by Panda et al. [75], who reported that the incorporation of nano-attapulgite clay significantly increased yield stress, apparent viscosity, and structural build-up rates, thereby improving printability, as shown in Figure 13. Owing to these rheological improvements, NC is widely employed in extrusion-based 3DPC, where it primarily functions as a viscosity-modifying agent (VMA).

Figure 13.

Influence of NC on rheological properties (a) Static Yield Stress (b) Apparent Viscosity [75].

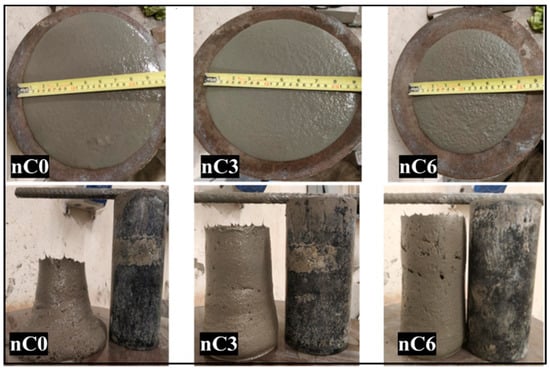

Kaushik et al. [57] investigated the influence of NC on the fresh properties of 3DPC. They found that the addition of NC reduced the slump flow by 20% (Figure 14), while increasing the yield stress by over 60%, indicating enhanced cohesiveness, stability, and printability of the blend. The study highlighted a strong inverse relationship between slump flow and yield stress. Notably, the addition of NC enhanced the elastic modulus at an early stage, improving the green strength of the mortar. This enhancement is attributed to the formation of calcium silicate hydrate, which accelerates the development of early strength. Hugo et al. [125] investigated the effects of three different types of clays—bentonite, sepiolite, and attapulgite—combined with two kinds of VMAs and fly ash on the rheological properties of cement-based systems for 3D printing. The study found that sepiolite, when paired with methylcellulose ether as a VMA, significantly enhanced extrusion characteristics by doubling the initial shear yield stress, achieving values above 2 kPa for defect-free extrusion. While fly ash reduced the paste’s thixotropy, sepiolite mitigated this effect and improved the structural build-up rate to 155 Pa/min. Methylcellulose ether-based VMA increased cohesion and extrudability but delayed stiffening, highlighting the importance of balancing initial and compressive yield stresses for optimal buildability. Proper extrusion is associated with a cohesive mixture and low friction. The study also reported that the cone penetration test, though helpful in assessing extrusion and buildability, was observed to overestimate shear yield stress over time due to compression effects during testing. Further studies [126,127] have confirmed the above-reported findings, indicating that the inclusion of NC in the printable mix improves yield stress and thixotropy, leading to better structural rebuilding rates and reduced formwork pressure.

Figure 14.

Reduced spread diameter and improved slump stability with increasing NC dosage [57].

Rahul et al. [105] reported that incorporating 0.1–0.3% NC enhanced thixotropy and yield stress control, improving buildability. Yu Wang et al. [128] investigated the effects of NC addition at 7–9%, revealing its role as a nano-filler that bridges the gaps between cement particles, thereby forming an interlocking microstructure. Thus, it improved static yield stress by 1.5–2 times while boosting green strength by 20–30%. A synergistic effect with 3% superplasticiser doubled the initial yield stress, achieving optimal extrusion with a fluidity of 170–200 mm and a viscosity that rose from 1.6 to 2.6 Pa·s. Sonebi et al. [55] reported that incorporating NC enhances the cohesiveness and flocculation strength of printable concrete, increasing density and yield stress, though varying proportions may compromise workability and extrusion properties. Kaushik et al. [45] optimised NC incorporation by defining a “printability box” to balance static yield stress and consistency. The 3% NC mix achieved an ideal synergy of workability and structural stability, ensuring cohesive, sharp, and segregation-resistant layers.

Ali et al. [29] and Zhang et al. [56] studied the effects of NC and SF on the workability and printability of printable concrete. Ali et al. found that incorporating 0.3% highly purified attapulgite clay and 10% SF improved compressive strength by 10%, with NC showing the least layer settlement. SF enhanced print quality and shape stability. In contrast, Zhang et al. reported that adding 2% NC and 2% SF significantly improved buildability, with the double-doped blend increasing buildability by four times and green strength by two times compared to the reference mix. Both studies highlighted a linear inverse relationship between green strength and flowability, emphasising the challenge of balancing structural integrity with extrusion ease in 3D printing applications. A study [129] investigated low-carbon 3D-printed concrete by incorporating 50% GGBS and highly purified attapulgite nano-clay at 0.25% and 0.5% by mass of cement. The results indicated that mixes with only cement demonstrated mechanical properties that were over 50% higher compared to those containing GGBS. However, the addition of NC reduced this decline to less than 10%. Although GGBS provides a sustainable pathway to reducing embodied carbon, its optimal replacement levels require further study to ensure reliable printability.

NC also influences hardened properties by accelerating strength gain, enhancing elastic modulus, and inducing anisotropic variations in compressive and flexural strength [75,130,131]. In synergy with SCMs, it promotes early strength development and long-term densification. Its effectiveness, however, is dosage-sensitive: moderate levels stabilise the mix and strengthen interlayer bonding through ettringite networking, whereas excessive amounts sharply increase viscosity and hinder extrusion. To mitigate these risks, recent studies recommend maintaining a mini-slump flow in the range of 65–75 mm, which provides a workable balance between extrusion ease and structural stability in printable concretes.

4.3. Nano-CaCO3

Calcium carbonate nanoparticles are one of the most affordable nanoparticles available. It is because of its lower energy-intensity requirements for manufacturing [132]. They are widely used in cement-based materials because of their significant physical and chemical reactivity, as well as their compatibility with various matrices. Additionally, CaCO3 nanoparticles are non-toxic to both humans and the environment, making them a more sustainable and eco-friendly option [133].

In a study conducted by Yang et al. [134], the authors partially replaced limestone powder in printable blends with 1–3% CaCO3 nanoparticles by mass, highlighting that the incorporation of NCa improved buildability without significantly affecting flowability. The nucleation effect of NCa accelerated hydration, resulting in enhanced green strength and yield stress. Notably, the addition of 3% NCa reduced layer deformation by nearly one-third compared to the 0%, 1%, and 2% blends, indicating improved buildability. While mechanical properties, such as compressive and flexural strength, showed limited improvement, the compressive strength of the 1% NCa mix outperformed that of the other blends. However, the compressive strength remained lower than that of cast specimens due to the presence of elongated voids, which reduced the overall mechanical strength. NCa accelerates cement hydration and enhances the microstructure by increasing density and reducing pore size. In another study [135], the incorporation of calcium carbonate nanoparticles at a 1–4% mass fraction as a partial replacement for fly ash enhances the rheological, mechanical, and microstructural properties of printable concrete. The filler and hydration-accelerating effects of NCa refine the pore structure, increase yield stress and viscosity, and reduce vertical filament displacement, improving stability during printing. At 2%, NCa achieves an optimal balance between rheology and strength. Mechanical properties peak at 4%, with compressive strength doubling from 25 MPa to 50 MPa and flexural strength rising from 8 to 13 MPa. SEM and BSE analyses confirm a denser microstructure, smaller calcium hydroxide crystals, and uniform distribution of hydration products, emphasising NCa’s role in refining the microstructure and enhancing performance.

NCa demonstrates significant potential in 3DPC by enhancing properties such as buildability, yield stress, and microstructure through hydration acceleration and pore refinement. However, its influence on mechanical properties, such as compressive strength, is inconsistent and often impacted by printing-induced voids and anisotropy. These drawbacks become more pronounced at higher dosages, but they can be partly mitigated by strategies such as interlayer surface conditioning or reducing the time interval between successive layer depositions. While its eco-friendliness and cost-efficiency make it an attractive choice, research on its comprehensive performance in both fresh and hardened states remain limited, necessitating further exploration for full-scale applications.

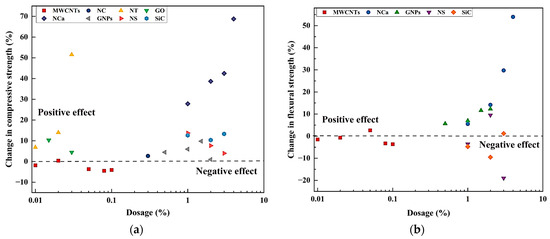

4.4. Carbon Based Nanomaterials

Carbon-based nanomaterials have been extensively investigated as reinforcement fillers in cementitious composites due to their unique properties. A detailed classification of these materials is presented in Figure 4. However, additional types exist beyond those illustrated, highlighting the diversity. These materials provide a bridging effect, resist crack propagation and accelerate hydration reactions. Furthermore, the specific porous and layered structures of these materials function as viscosity-modifying agents capable of altering the rheological behaviour required for 3DPC [53]. A detailed analysis of some of these materials is provided in the subsequent sections.

4.4.1. Carbon Nanotubes and Fibers

Sun et al. [136], added multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and polyvinyl alcohol fibres at maximum dosages of 0.1% for the former and 1.5% for the latter by mass of binder. The study highlighted that the addition of MWCNTs did not result in any noticeable variation in flowability, setting time, or buildability. In contrast, the addition of fibres drastically reduced flowability by around 40% and made the mix stiffer to extrude. The compressive strength and flexural strength were not significantly different after 28 days, and no clear trend patterns for strength development were observed. It was concluded that the excessive agglomeration of MWCNTs may be the cause of this phenomenon. Nevertheless, the addition of fibres demonstrated a bridging effect in the specimen.

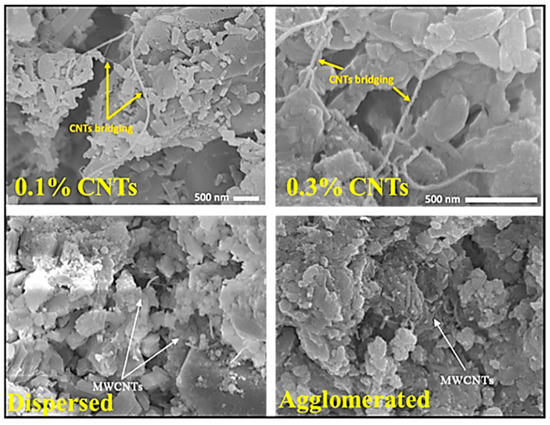

In contrast, Ali et al. [58], dispersed MWCNTs using sonication and showed that proper dispersion is critical. Their results highlighted that 0.2% CNTs improved buildability by 81% and that a combination of 5% silica fume and 0.1% CNTs increased buildability by 74% compared to the reference. Furthermore, 0.2% CNTs enhanced compressive strength by 72%, Young’s modulus by 43%, and nearly doubled flexural strength after 28 days. This improvement was linked to nanoscale crack bridging, where CNTs form fibre-based networks that reduce macrocracks and voids. The scanning electron micrographs in Figure 15 show CNTs bridging within the cement matrix at different dosages, highlighting the importance of effective dispersion versus agglomeration.

Figure 15.

CNT dispersion and bridging in cementitious composites: (top) bridging at 0.1% and 0.3% CNTs, (bottom) comparison of dispersed and agglomerated MWCNTs [58,136].

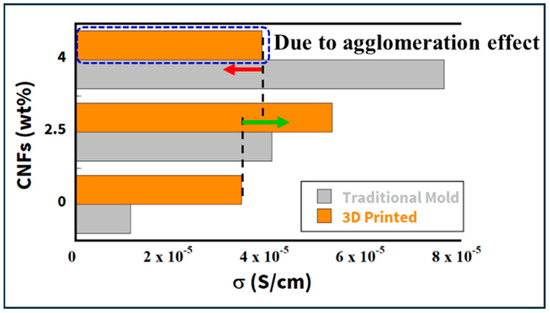

CNFs have been explored as functional additives to enhance the electrical performance of 3D-printed cementitious composites. Goracci et al. [137] reported that incorporating CNFs increased the electrical conductivity of 3D-printed specimens compared with mould-cast counterparts, with conductivity improving in direct proportion to CNF content. The superior performance of printed concrete was attributed to the extrusion process, which aligns fibres along efficient pathways, while also modifying the pore network to improve the distribution and retention of free water molecules, thereby facilitating ion transport. This alignment also enhanced the longitudinal-to-transverse conductivity ratio, providing directional conductivity that is beneficial for applications such as sensors and conductive composites. Complementing this, Kosson et al. [138] observed that CNF- and CMF-modified mixes suffered from under-extrusion issues and that CNFs reduced compressive strength by 44% compared with controls, underscoring the trade-off between conductivity and mechanical performance. As illustrated in Figure 16, electrical conductivity increases with CNF content up to an optimal dosage, after which agglomeration reduces efficiency, particularly in mold-cast specimens. In 3D-printed CNF composites, conductivity at low CNF contents is dominated by interconnected pores and mobile water, enhanced by extrusion-induced pore networks. At higher CNF loadings, partial alignment competes with agglomeration, so dispersion quality—not dosage alone—governs whether a stable percolation network forms.

Figure 16.

Effect of CNF dosage on electrical conductivity of 3D-printed and mold-cast composites [137].

Collectively, these findings show that while CNTs enhance buildability and mechanical properties through nanoscale crack bridging, CNFs provide directional conductivity and multifunctional potential. However, issues such as agglomeration, nozzle blockage, and inconsistent strength gains highlight the need for precise dispersion methods and dosage optimisation to fully explore their benefits. In practice, dispersion quality is often validated by UV–Vis absorbance stability, with typical surfactant–carbon ratios in the range of 1–2:1 and sonication energies on the order of 100–200 J/mL. Without adequate dispersion, CNFs in particular have been reported to cause under-extrusion and nozzle blockage, limiting their processability in 3DPC.

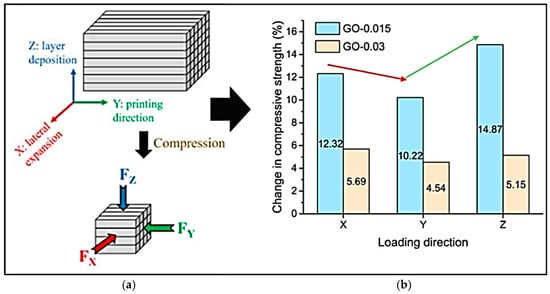

4.4.2. Nano-Graphene Oxide

Liu et al. [48] investigated the incorporation of GO sheets in 3DPC and reported that a b% dosage (by binder mass) increased compressive strength by ~10%, attributed to effective dispersion and matrix filling. In contrast, 0.03% GO reduced flowability, which caused void formation and weakened strength despite microstructural densification at both dosages. Notably, the influence of GO is also direction-dependent: as illustrated in Figure 17, a 0.015% dosage improved compressive strength along all loading directions, whereas 0.03% reduced the gains and amplified anisotropy. This highlights the importance of dosage optimisation to balance workability and mechanical performance.

Figure 17.

(a) Direction of compression strength testing (b) Effect of GO dosage on compressive strength in different loading directions [48].

Further study by Ahmadi et al. [139] confirmed the mechanical benefits of graphene modifications, where GO-coated steel fibres yielded a 20% gain in compressive strength, doubled tensile strength, and 60% higher flexural strength, alongside narrower cracks under flexural loading. These results reinforce the structural potential of GO when dispersion and fibre integration are well controlled.

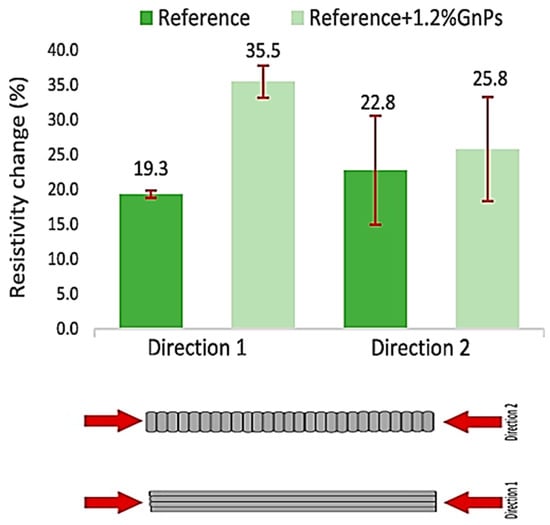

Dulaj et al. [140] examined the influence of GNPs on the mechanical and self-sensing performance of 3DPC. While GnPs improved compressive strength and self-sensing ability in cast specimens, their impact on printed ones was strongly affected by anisotropy from layer-by-layer deposition. As shown in Figure 18, printed specimens exhibited direction-dependent resistivity responses: in Direction 1, the addition of 1.2% GnPs increased the resistivity change from 19.3% to 35.5%, whereas in Direction 2, the gain was smaller (22.8% to 25.8%). This highlights that although GnPs can enhance self-sensing ability, their effectiveness in printed elements depends on the printing orientation and interlayer bonding quality.

Figure 18.

Resistivity change in printed mortar specimens with and without GNPs tested along two printing directions [140].

Taken together, these studies indicate that GO nanoparticles and GNPs have strong potential to enhance the mechanical properties and multifunctionality of cementitious composites. However, their use in 3DPC is limited by challenges such as reduced flowability, agglomeration at higher dosages, and weaker interlayer bonding. Overcoming these barriers requires careful dosage optimisation, improved dispersion methods, and the integration of admixtures to balance mechanical performance with printability and structural integrity. Beyond laboratory indicators, the resistivity and self-sensing responses of GO- and GNP-modified mixes point to direct utility in 3D-printed structural components. Printed beams, slabs, and facade panels can benefit from embedded self-monitoring capability, where changes in the electrical response signal indicate crack initiation or strain build-up. Such integration supports predictive maintenance, extends service life, and reduces reliance on external sensing systems [139,140].

Beyond conventional carbon NMs, emerging 2D nanofillers such as MXenes (e.g., Ti3C2Tx and Mo2Ctx) have demonstrated tribofilm-enabled superlubricity and shear reduction. In situ tribofilm formation with Ti3C2Tx MXene nanoflakes in glycerol achieved a macroscale superlubricity regime, with the coefficient of friction reduced to ~0.002, thereby drastically lowering interfacial shear stresses and wear [141]. Similarly, Mo2Ctx MXene bio-microcapsule nanofluids reduced cutting friction by up to 66% and stabilised lubrication through controlled release, underscoring their potential to enable low-shear deposition windows at constant build rates in 3DPC [142]. In parallel, coupled thermal–force simulations with GO nanofluids have revealed concentration-dependent performance: at 0.1–0.3 wt%, GO nanosheets dispersed in fluid media enhanced heat transfer and reduced applied forces; however, at higher loadings, agglomeration reversed these benefits, leading to instability. Such findings reinforce the need to consistently report dosage–dispersion–performance triads in 3DPC to ensure reproducibility and comparability across studies [143,144].

A critical practical requirement for realising these multifunctional applications is ensuring reliable dispersion of carbon NMs. Across CNTs, CNFs, GO, and GNPs, effective dispersion is typically validated by UV–Vis absorbance stability, with sonication energies on the order of 100–200 J/mL and surfactant to carbon ratios around 1–2:1. Insufficient dispersion not only diminishes the expected strength or sensing gains but can also cause severe printability problems; CNFs, for instance, are prone to under-extrusion and nozzle blockage when not correctly processed. To improve reproducibility and comparability of results, the above studies recommend that studies report dosage–dispersion–performance triads when evaluating carbon-based NMs in 3DPC.

4.5. Nano-TiO2

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles possess photocatalytic properties, which enable concrete to self-clean and promote environmental sustainability by breaking down SOx and NOx compounds present in the air. Additionally, it also possesses antimicrobial properties [145,146]. To explore its potential in modern construction, researchers have incorporated NT into printable concrete, where it has been shown to significantly enhance both functional and structural performance. Zahabizadeh et al. [147,148] demonstrated that NT surface coatings improve photocatalytic activity under light exposure, with higher coating rates producing more uniform particle distribution and greater dye degradation efficiency. Specimens coated after seven days exhibited the highest efficiency due to favorable surface conditions, while extended curing led to reduced adsorption capacity from pore refinement and densification.

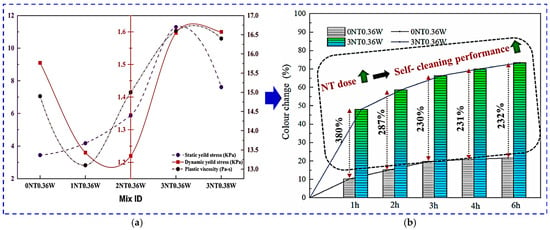

Beyond surface coatings, incorporating NT directly into printable mixes improves both buildability and functional performance. Rheologically, NT increases static yield stress while reducing dynamic yield stress and plastic viscosity, producing pastes that extrude smoothly yet retain stability after deposition. At an optimum dosage of around 3% with a w/c of 0.36, buildability improved markedly, up to 3.24 times the reference mix, supporting more than 120 layers without collapse. Functionally, NT enhances photocatalytic self-cleaning, as shown in Figure 19. Under UV irradiation, NT-containing specimens exhibited substantially higher colour degradation rates than controls, with photocatalytic removal of Rhodamine B dye exceeding 230–280% of the reference over 6h. Since greater colour change directly reflects stronger photocatalytic activity, this behaviour confirms NT’s ability to impart durable self-cleaning properties. Together, these findings establish NT as a multifunctional additive that not only enhances rheology and buildability but also promotes sustainability in 3DPC through photocatalytic depollution and reduced maintenance demands [149].

Figure 19.

Influence of NT incorporation on 3DPC: (a) Rheological behaviour; (b) Photocatalytic self-cleaning performance. Modified from [148].

In practical applications, these photocatalytic properties can be directly leveraged in 3D-printed facades, paving blocks, and noise barriers, where NT-functionalised surfaces continuously degrade NOx/SOx pollutants and organic deposits under natural light. This not only preserves aesthetic quality and reduces cleaning frequency, but also enhances long-term durability by limiting pollutant-induced surface deterioration, thereby lowering life-cycle costs of 3DPC components [147,148].

NT coatings also modify surface topography by filling irregularities and exposing hydration by-products such as C–S–H and Ca(OH)2, thereby enhancing overall structural integrity [47]. These findings highlight the potential of NT to advance the functional and structural performance of 3D-printed cementitious materials, though optimizing dosage and application methods remains critical.

In summary, the literature reviewed so far consistently indicates that the inclusion of NMs into printable concrete can significantly influence its properties in both fresh and hardened states. Table 1 below provides a summary of additional research investigating the effects of incorporating NMs into printable concrete and their interactions with other materials.

Table 1.

Additional studies on NMs in 3DPC: dosages, additives, and their reported effects.

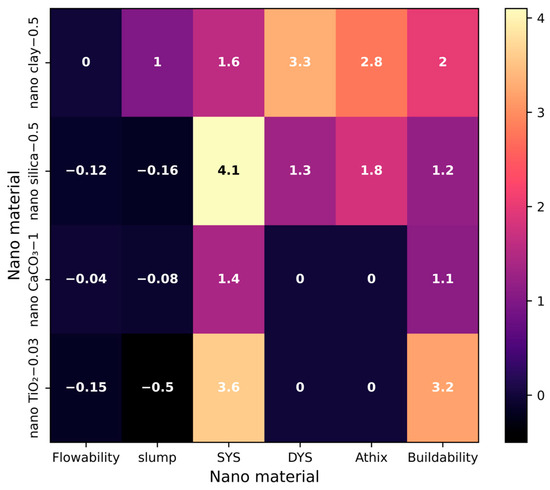

Taken together, the reviewed studies demonstrate that different NMs influence 3DPC through distinct but sometimes overlapping mechanisms, including pozzolanic activity, nucleation, filler densification, and functional enhancements such as crack bridging or photocatalysis. To provide a consolidated overview, Table 2 summarises the main NMs explored in 3DPC, outlining their activity type, dominant mechanism, typical dosage ranges, and common dispersion aids.

Table 2.

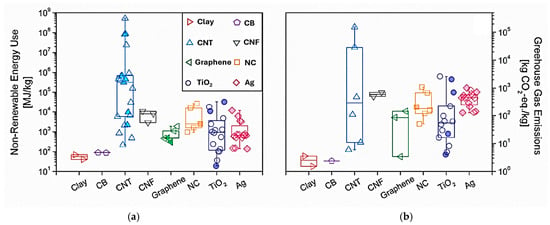

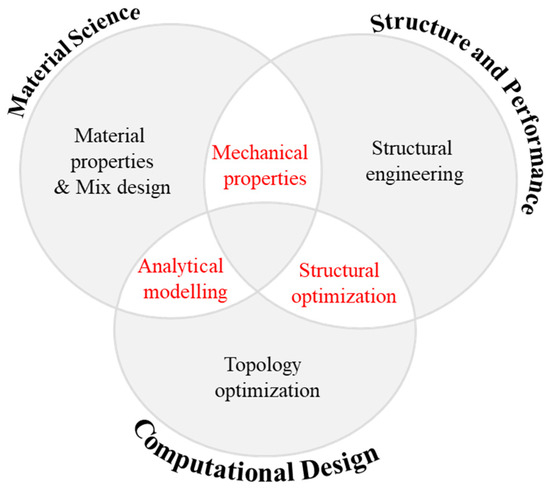

Overview of NMs in 3DPC: activity, mechanisms, and dispersion approaches.