Abstract

Existing long-form video recommendation systems primarily rely on rating prediction or click-through rate estimation. However, the former is constrained by data sparsity, while the latter fails to capture actual viewing experiences. The accumulation of mid-playback abandonment behaviors undermines platform stickiness and commercial value. To address this issue, this paper seeks to improve viewing engagement. Grounded in Expectation-Confirmation Theory, this paper proposes the Long-Form Video Viewing Engagement Prediction (LVVEP) method. Specifically, LVVEP estimates user expectations from storyline semantics encoded by a pre-trained BERT model and refined via contrastive learning, weighted by historical engagement levels. Perceived experience is dynamically constructed using a GRU-based encoder enhanced with cross-attention and a neural tensor kernel, enabling the model to capture evolving preferences and fine-grained semantic interactions. The model parameters are optimized by jointly combining prediction loss with contrastive loss, achieving more accurate user viewing engagement predictions. Experiments conducted on real-world long-form video viewing records demonstrate that LVVEP outperforms baseline models, providing novel methodological contributions and empirical evidence to research on long-form video recommendation. The findings provide practical implications for optimizing platform management, improving operational efficiency, and enhancing the quality of information services in long-form video platforms.

1. Introduction

In the era of mobile Internet, long-form video has become a major medium for entertainment and leisure activities. Unlike short-form videos, which create addictive behavior through dopamine-driven cycles, long-form videos offer viewers a deeper sense of satisfaction associated with sustained cognitive and emotional engagement. Consequently, platforms such as YouTube, Dailymotion, and Vimeo attract hundreds of millions of daily active users and hold substantial market shares. However, as the availability of long-form video-on-demand resources continues to grow, platforms face increasing challenges related to information overload in their management and operational processes. This overload not only raises the time required for filtering on-demand content but also contributes to declining user satisfaction and higher churn rates, thereby disrupting the commercial monetization pathways of long-form video content and posing significant risks to the sustainable development of the long-form video industry. This phenomenon also poses threats to the broader cultural and entertainment sectors.

In addressing the challenge of information overload, both academia and industry have sought to predict user behaviors, such as click-through rate (CTR), ratings, and viewing duration, to facilitate long-form video recommendations that help consumers filter out irrelevant content. Existing long-form video recommendation systems can be categorized by their underlying methods into collaborative filtering-based systems, content-based systems, deep learning-based systems, and hybrid systems. These systems generate accurate and efficient recommendations for long-form video viewers by mining both user interaction data and information about long-form video products. However, most current systems rely primarily on predicting user ratings or CTR to construct recommendation lists, which present several limitations. First, in practical platform operations, a large proportion of long-form video viewers do not habitually provide ratings, resulting in data sparsity issues for rating-based and rating-prediction-based systems. This scarcity constrains the accuracy of recommendations and ultimately degrades the effectiveness of information services [1]. Second, as long-form video platforms generate revenue primarily from advertising and subscription fees [2], CTR-based systems can effectively attract users to click on videos; however, this metric does not guarantee that viewers will watch the content in its entirety [3]. Viewers may exit before completion, indicating dissatisfaction with the recommended content. The likelihood of early termination increases with longer durations and denser informational content. Continuously recommending such long-form videos can undermine advertising effectiveness from the advertisers’ perspective and diminish viewing experiences from the users’ perspective, thereby reducing advertisers’ willingness to invest and users’ willingness to subscribe. This, in turn, impairs both the service quality and the economic returns of long-form video platforms, posing obstacles to the sustainable growth of the long-form video industry [4].

Therefore, recommending long-form videos that viewers are more likely to watch in their entirety, namely, those with higher viewing engagement, is particularly important for increasing user retention time on the platform and for supporting the operation and growth of long-form video services. However, existing research has rarely designed recommendation systems from the perspective of viewing engagement. Although a limited number of studies have considered user viewing duration, none have systematically examined the influence of long-form video content on both viewing duration and engagement. For example, Lin et al. [5] focused solely on factors influencing user clicks, such as video titles and click trajectories, to recommend videos. These features, however, are suitable primarily for click-oriented short video recommendations and perform poorly when applied to long-form videos exceeding 30 min in length. Zhan et al. [6] studied duration bias in watch-time prediction for video recommendation, while neglecting content influence in predicting user engagement. For long-form content, click-through rate-oriented models struggle to accurately capture user preferences in a way that sustains viewing duration [7]. In light of this, from the perspective of enhancing the quality of information services and improving operational competitiveness for long-form video platforms, it is necessary to design a novel and effective recommendation method that prioritizes improving viewing engagement by integrating information from both the video side and the user side.

To this end, this paper proposes a long-form video recommendation method based on predicting user viewing engagement. By conducting an in-depth analysis of user behaviors and long-form video content, and drawing on Expectation-Confirmation Theory from consumer behavior research [8], a novel recommendation method, LVVEP, is introduced. According to Expectation-Confirmation Theory, user satisfaction and continued usage intentions are determined by the consistency between their expectations of a product or service and their perceived experiences [9]. This paper characterizes users’ expectations and perceived experiences for unviewed long-form videos based on historical user viewing behaviors and the textual content of long-form video products. The confirmation relationship between expectations and perceived experiences is then used to predict user viewing engagement and generate long-form video recommendations. Experiments conducted on real datasets of movies and television series demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed LVVEP method. Compared with state-of-the-art baseline models, LVVEP significantly reduces prediction loss, improves prediction accuracy by more than 25.00%, increases the F1 score by more than 16.49%, and enhances the top 5, top 10, and top 15 recommendation hit rates by 4.63%, 10.53%, and 11.54%, respectively.

Section 2 of this paper reviews the relevant literature and summarizes previous research progress. Section 3 presents the recommendation system framework, depicting user expectations, perceived experiences, and viewing engagement. Section 4 details the experimental design, which uses real long-form video viewing logs to validate the proposed recommendation system. Section 5 analyzes the experimental results, and Section 6 provides conclusions and insights.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Long-Form Video Recommendation Systems

Existing long-form video recommendation systems can be categorized by their underlying methods into collaborative filtering-based systems, content-based systems, deep learning-based systems, and hybrid systems [5]. Collaborative filtering (CF) is one of the most common approaches in recommendation systems [10]. It analyzes users’ historical behavior data to identify similarities among users and recommends long-form videos preferred by similar users. For example, Gupta et al. [11] combined the KNN algorithm and collaborative filtering for movie recommendation, and validated their long-form video recommendations using the MovieLens dataset. Koren et al. [12] applied matrix factorization models to user-item rating matrices in recommendation scenarios, mapping both users and long-form video items into latent factor spaces to effectively capture user preferences and predict potential ratings and viewing interests for unrated items. Sahoo et al. [13] focused on the halo effect commonly present in multidimensional ratings, noting that a user’s overall rating of a movie can influence ratings of individual components such as storyline and direction. Based on this observation, they proposed a structured learning algorithm to more accurately predict movie ratings and improve the recommendation system performance.

Content-based filtering (CBF) systems focus on analyzing the features of long-form video content, such as genre, director, and cast, to predict user preferences. Son et al. [14] proposed a content filtering algorithm based on multi-attribute networks, which reflects similarities among long-form video items by considering multiple attributes and employs network analysis to measure both direct and indirect connections between items, thereby recommending similar long-form videos to users. Shi et al. [15] combined collaborative filtering and content-based recommendation methods by integrating user-item rating matrices with movie similarity matrices derived from movie reviews, incorporating rating information into the recommendation process, and demonstrating performance advantages over single-method approaches.

With the development of artificial intelligence, machine learning- and deep learning-based recommendation systems have increasingly become a research focus and frontier in the field. Focusing on long-form video recommendation, Lu et al. [16] proposed a deep Bayesian tensor system for long-form video recommendation, which captures latent patterns of user behavior and enhances recommendation relevance and novelty by modeling Bayesian surprise using rich online multi-relational long-form video information. Zhou et al. [17] combined recurrent neural networks with attention mechanisms to develop a deep interest evolution network that predicts users’ click-through rates (CTR) for recommended content. Considering the sequential nature of long-form video viewing behavior, Jiao et al. [18] integrated deep neural network language models with user playback sequence analysis, mapping long-form videos to feature vectors and using SVD++ and Bi-LSTM models to accurately model users’ interest distributions, thereby generating personalized Top-N long-form video recommendation lists. Zhan et al. [19] and Zhao et al. [6] designed deep learning-based long-form video recommendation systems with user viewing duration as the prediction target.

Research on long-form video recommendation systems is progressing toward more personalized and precise approaches. However, existing methods still exhibit certain limitations. First, collaborative filtering-based or hybrid recommendation systems continue to rely on user rating data, which may result in suboptimal recommendation performance on long-form video platforms with sparse rating information, limiting their large-scale applicability. Second, current content-based recommendation systems typically incorporate only features with limited information, such as video titles and genres, making it difficult to accurately measure video similarity and capture user preferences solely based on these content features. Third, deep learning-based long-form video recommendation systems incorporate the evolution of user interests and contextual information into the models, yet most studies focus primarily on click-through rate prediction, and only a few consider user satisfaction as reflected by viewing engagement. In particular, there is a lack of recommendation methods that integrate both long-form video content features and user-side information to predict and enhance user viewing engagement. Therefore, this paper proposes a long-form video recommendation system based on engagement prediction, aiming to provide novel information service methods for long-form video platforms and improve user satisfaction.

2.2. Factors Influencing Viewing Engagement

Viewing engagement in long-form videos is defined as the combination of users’ behavioral and psychological investment in the video content. Unlike social media engagement, such as likes and comments, which are mediated by social platforms, this paper focuses on viewing engagement specifically related to long-form videos, referring to users’ sustained and deep involvement and attention during playback. Viewing engagement is primarily measured by indicators such as viewing duration [20] and the proportion of the video watched [7]. Since viewing engagement is directly associated with platform operational performance and encompasses all users, whereas social media engagement data are fragmented, sparse, and temporally delayed, and cannot be directly linked to specific in-platform user behavior paths or experience quality, this study aims to enhance user viewing engagement.

The factors influencing user viewing engagement can be categorized into four main types. The first type is the technical quality of long-form videos [20]. Factors such as rendering quality, loading time, and bitrate directly affect the user experience by disrupting visual smoothness and cognitive continuity, thereby influencing the user’s immersion threshold. Within the same platform, the technical quality of long-form videos is largely homogeneous. With the standardization of content delivery network (CDN) technologies and improvements in device computing power, major platforms (e.g., Netflix, Tencent Video) have achieved technical quality homogeneity, such that under identical playback settings, differences in clarity, buffering rates, and other indicators across different long-form videos have largely converged. Users are also able to select playback configurations that suit their preferences. Therefore, on major long-form video media platforms today, technical quality is not a primary factor affecting user experience.

The second type is environmental factors [21,22], such as the user’s physical location, viewing time, and socio-cultural background, which can influence viewing experience. Viewing time significantly affects content preference and engagement depth by modulating attention bandwidth and emotional state. For instance, fragmented viewing during morning commutes differs from immersive viewing at night. Similarly, the same long-form video may be experienced differently by users in different geographic regions or socio-cultural contexts. Regional cultural background affects narrative reception, while educational level modulates cognitive engagement thresholds. Therefore, viewing time and geographic location should be controlled, whereas cultural and educational background information is difficult to obtain at scale due to privacy concerns.

The third type is psychological factors [23], such as the user’s current mood and physiological or psychological state, which may influence viewing experience. However, these are not primary factors and are difficult to acquire at scale in real time. Emotional state changes dynamically with context and interacts with long-form video content in a highly stochastic manner. Moreover, user emotions are difficult to capture on a large scale under natural viewing conditions.

The fourth type is video content. Studies [22] have found that users’ long-form video viewing sessions often consist of many short-duration sessions, and they indicate that even if a user clicks on a video due to certain factors, the viewing duration may be brief if the content does not meet the user’s preferences. This phenomenon fundamentally stems from the nature of long-form video viewing as a process of deep cognitive and emotional investment. Insights from multiple disciplinary theories and empirical findings provide guidance. In neuroscience and narrative communication research, it has been shown that when content constructs an immersive narrative environment, users experience a “disengagement from reality” psychological state, enhancing immersion and increasing continued viewing intention [24]. High-quality narratives activate the default mode network (DMN) and trigger neural coupling through empathy with characters, naturally extending viewing duration [25]. Cognitive load theory suggests that content complexity aligned with users’ cognitive capacity stimulates exploratory behavior [26], whereas long-form videos with information overload (e.g., unfocused knowledge accumulation) activate prefrontal inhibition, leading to early dropout [27]. Role identification theory indicates that users achieve vicarious satisfaction through characters, and viewing duration is positively correlated with the depth of character development [28]. Therefore, emotional immersion in long-form video content is crucial for maintaining extended viewing.

In summary, the first type of factors has become largely homogenized on contemporary standardized long-form video platforms; the second type represents common environmental control variables; the third type is highly subjective and difficult to capture at scale; and the fourth type, namely, video content, constitutes the core factor influencing and differentiating user viewing engagement. Unlike existing studies that focus on superficial content features with limited information, such as titles, genres, or user comments, this paper emphasizes the video content itself. While external content features may influence user clicks, they are weakly related to sustained viewing. The user’s continued viewing intention is primarily determined by whether the video content aligns with their viewing preferences.

2.3. Expectation-Confirmation Theory

Expectation-Confirmation Theory (ECT), originating from consumer behavior research, was first proposed by Oliver [29] to explain the decision-making process underlying consumer satisfaction. The theory, based on the concept of cognitive consistency, posits that an individual’s satisfaction with a product or service depends on the congruence between prior expectations and perceived experiences. When perceived experience meets or exceeds expectation, the individual experiences satisfaction; conversely, dissatisfaction occurs when expectations are not met. Expectation-Confirmation Theory has been widely applied across multiple domains, including information systems [9,30], social media marketing [31], and service quality management [32].

Yang et al. [33] investigated recommendation vlogs (Rec-vlogs) to examine factors influencing users’ continued usage intention. Using a survey of Rec-vlogs users combined with partial least squares structural equation modeling, the study found that the alignment between users and vloggers, as well as users’ perceived content diagnosticity, are key predictors of continued usage intention. Meanwhile, some scholars have applied Expectation-Confirmation Theory to explore the impact of product quality on perceived experience. Duanmu et al. [34] focused on technical aspects of long-form videos, such as video resolution, and proposed a user experience quality model based on Expectation-Confirmation Theory. Through large-scale video data experiments and user studies, the model’s predictions were shown to be consistent with subjective user evaluations and superior to other user experience quality models.

In summary, Expectation-Confirmation Theory systematically explains the formation mechanism of consumer satisfaction. This paper introduces the theory into the design of long-form video platform information services, focusing on predicting user viewing engagement in long-form video recommendation systems. By integrating deep learning models and optimization algorithms, the study characterizes users’ expectations and perceived experiences for unwatched long-form videos, and leverages the discrepancy between expectations and perceived experiences to predict user viewing engagement, thereby generating long-form video content recommendation lists.

3. Research Design

3.1. Problem Statement

This paper aims to enhance the quality of information services on long-form video platforms. Addressing the limitations of existing studies that overly rely on user click behavior while neglecting actual viewing experience, the study proposes a novel and effective long-form video content recommendation method that integrates both user-side and video-side information. Let the historical viewing records of user on the platform be denoted as , where represents video and represents the number of long-form videos watched by user within the dataset time window. The corresponding viewing engagement sequence is defined as , with each element calculated as the ratio of viewing duration to the total length of the video. The sequence of video storyline information is denoted as . The set of long-form videos not yet watched by user is represented as , where denotes the complete set of long-form videos available on the platform. Since the user’s viewing behavior evolves over time, let , , , and denote, respectively, the historical viewing sequence, historical engagement sequence, historical video storyline sequence, and the set of unwatched long-form videos for user up to time .

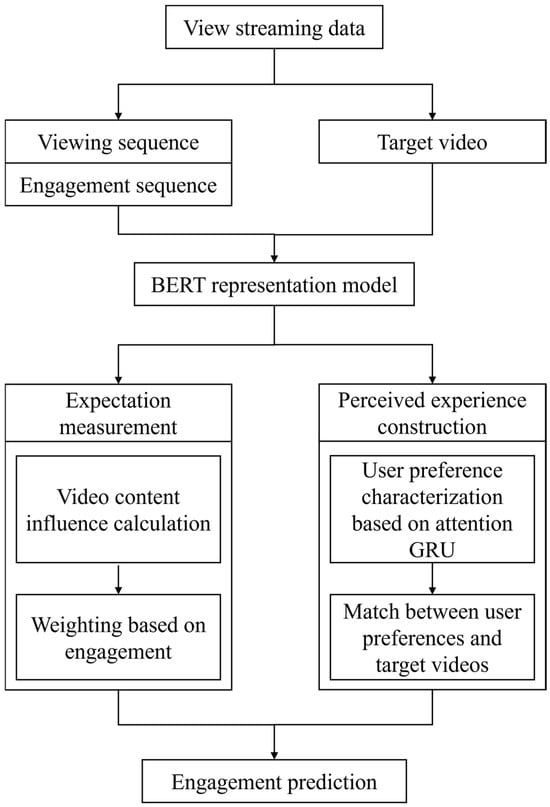

The long-form video recommendation system designed in this study, named LVVEP (Long-form video Viewing Engagement Prediction), aims to predict the viewing engagement of user for each long-form video in by modeling the user’s expectation and perceived experience . Based on these predictions, the system generates recommendations of high-engagement long-form videos for user . The overall design logic of LVVEP is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall Framework of LVVEP.

3.2. Measurement of Expectation

Expectation-Confirmation Theory posits that expectations are established based on consumers’ prior consumption experiences and the information provided by marketers, representing a prediction of what is likely to occur with a product or service. In the context of long-form video consumption, a user’s expectation toward a video originates from two sources: accumulated past consumption experiences of video and the currently available information about the target video [7]. When encountering an unwatched video, a user forms a prior cognitive judgment regarding the potential viewing experience by integrating the video’s descriptive information with personal historical viewing experiences.

Since the storyline of a long-form video serves as the primary driver of user engagement, the storyline text is semantically represented, allowing the similarity between videos to be measured through semantic similarity computation. BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), as an advanced pre-trained language representation model, captures long-range contextual semantic information and addresses polysemy, enabling context-sensitive vector representations of text. BERT has been widely applied across multiple natural language processing tasks [35]. In this study, a Chinese pre-trained BERT model developed by the HIT-iFLYTEK Joint Laboratory is employed to semantically represent long-form video content, forming the basis for expectation measurement.

After obtaining the static representation of user i’s historical video storyline sequence, the semantic representations produced by a pre-trained model on general-purpose corpora may deviate from the specific requirements of the task. This deviation can result in storyline embeddings that fail to adequately capture the relative differences and distinctiveness among storylines. To address this limitation, this study introduces a learnable projection layer, , which maps these static embeddings into a new vector space, such that the representations of similar storylines become closer, while those of dissimilar storylines are pushed apart. The historical storyline sequence of user , , is input into the BERT model and then the projection model , as shown in Equation (1).

After constructing , it is essential to properly train and update its parameters to ensure robust discriminative capacity with respect to semantic similarity. To this end, this study introduces a contrastive learning approach, in which the training objective “pulls positive samples closer while pushing negative samples farther apart.” This objective facilitates more effective optimization of the parameters of . If the model were to rely solely on the main task loss, the optimization signals might be relatively “sparse” or “indirect.” By incorporating contrastive learning, an explicit representational constraint is imposed, enabling the projection layer to not only serve the prediction task but also learn more discriminative representations.

Specifically, in constructing the training data, triplets are formed from the collection of storyline summaries. Here, denotes the anchor sample, namely the original storyline summary of a video; is a positive sample, representing a storyline summary that exhibits high semantic similarity with ; and is a negative sample, corresponding to a storyline summary that differs significantly in content from .

In this study, the open-source large-scale Chinese language model ChatGLM-6B [36] is employed to generate positive samples. Under the constraint of preserving the main narrative and event structure of the original storyline summary, diversified rewritings are produced through synonym substitution, textual expansion, and textual truncation, thereby constructing . For negative samples, this study follows the principle of “significant semantic divergence and clear categorical distinction.” Concretely, negative samples are not derived from modifications of the original storyline summary; instead, they are directly selected at random from storyline summaries of videos that differ completely in theme, narrative style, or event type.

To implement discriminative learning, this study adopts the InfoNCE (Information Noise-Contrastive Estimation) loss function [37], as shown in Equation (2). Compared with traditional reconstruction-oriented objectives, the advantage of InfoNCE lies in its ability to operate within a unified probabilistic framework, simultaneously maximizing the similarity between anchor samples and their corresponding positive samples while minimizing their similarity to a set of negative samples. In doing so, InfoNCE explicitly strengthens the discriminative structure of the embedding space.

Here, denotes the cosine similarity, where larger values indicate greater semantic closeness between two texts. N represents the batch size, denotes the set of users corresponding to the batch, refers to the set of videos in the batch, and is the number of negative samples assigned to each video. A larger value of increases the difficulty of the contrastive task, requiring the model to distinguish positive and negative samples across a broader range. This enhances the discriminative power of the embedding space, albeit at a higher computational cost. A smaller temperature parameter amplifies similarity differences, rendering the model more “selective.”

Upon constructing the contrastive learning framework, the semantic representation capability of video storylines is substantially enhanced, with semantically similar videos positioned closer together in the embedding space. The similarity between and a historical long-form video is measured by cosine similarity, reflecting the semantic closeness between the new video and the user’s past consumption. In the viewing history of user i, each long-form video has a distinct engagement level, denoted by . A higher engagement indicates a stronger preference for the corresponding video, and thus a higher expectation. By incorporating as weights, the expectation of user for a target long-form video at time can be calculated, as shown in Equation (3), where denotes the number of long-form videos watched by user up to time , and represents the expectation of user for the target long-form video at time .

3.3. Perceived Experience Construction

Perceived experience is essentially an intuitive evaluation of service quality. It is independent of pre-viewing expectations and reflects users’ net satisfaction during the viewing process. This experience is shaped by user preferences, as its quality is closely tied to the extent to which the service meets current preferences. Capturing dynamic user preferences is therefore critical, with profound implications for targeted advertising and optimizing platform revenue models.

In the context of long-form video consumption, when perceived experience exceeds expectation, users typically exhibit higher satisfaction and engagement, which can manifest as complete viewing or even repeated viewing. Conversely, when perceived experience falls short of expectation, users are likely to experience disappointment and terminate viewing prematurely. Since user preferences evolve dynamically across different stages, a static representation of perceived experience is insufficient to fully capture user preference. Thus, the present study models perceived experience by incorporating not only heterogeneous experiences across previously watched videos but also their temporal evolution and situational adaptability. This design allows the model to learn users’ stable preference patterns while simultaneously identifying and responding to preference shifts under varying viewing contexts.

To this end, we adopt a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [38] with contextual enhancements to capture and adapt to the dynamic nature of user preferences. The GRU’s gating mechanism enables selective memory retention and information forgetting, thereby accommodating both long-term and short-term preference variations. Compared with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, GRUs reduce parameter count by approximately 33%, lowering computational complexity and mitigating overfitting risks. Moreover, when sequential data implicitly contains state transition logic such as the evolution of user preferences, the GRU framework better aligns with the Markov assumption and achieves faster parameter convergence [39].

Specifically, the update gate controls the flow of information from the previous state to the current state through Equation (4), while the reset gate determines the influence of historical information on the formation of the new state through Equation (5). Here, denotes the hidden state at the previous time step, represents the semantic embedding vector of the video storyline at time , denotes the sigmoid activation function, and , , and are trainable parameters of the GRU. The reset gate captures short-term dependencies in the sequence. As shown in Equation (6), it regulates the proportion of historical information from that flows into the candidate hidden state . The symbol denotes element-wise multiplication. A smaller value of indicates that less prior information is retained, leading to greater forgetting. In addition, Equation (6) integrates the user’s engagement level at time to balance the contribution of current storyline information and prior preference . This design enhances the retention of storyline segments associated with higher past engagement while reducing the influence of less engaging experiences. Finally, Equation (7) controls the proportion of new information from the candidate hidden state and historical information preserved from , producing the hidden state output up to time .

To highlight the influence of a subset of historical long-form videos that exhibit high similarity to the target video on future user preferences, this study introduces an attention mechanism that scales the contribution of to the output according to its attention score. The attention score is computed using Equation (8), where denotes the semantic embedding vector of the target long-form video, and represents the length of the preference evolution sequence.

This study introduces a modeling framework based on the cross-attention mechanism. Compared with commonly used cosine similarity or Euclidean distance, cross-attention enables dynamic weight allocation at the dimensional level, rather than applying a uniform similarity calculation over the entire semantic vector. Cosine or Euclidean metrics implicitly assume equal contributions of all semantic dimensions, which often leads to the neglect of local fine-grained differences in high-dimensional scenarios. In contrast, cross-attention, through the query–key matching process, allows the user preference vector to differentially attend to distinct semantic subcomponents of the storyline summary, thereby automatically identifying the segments most aligned with the current preferences. This mechanism not only improves the resolution of semantic matching but also enhances the robustness of the model under nonlinear preference structures, thereby providing a more faithful representation of the multidimensional combinatorial effects of user preferences.

Within this framework, the user preference vector is regarded as the query, while the semantic representation of the video storyline summary serves as both the key and the value. The rationale behind this design is that user preferences actively initiate information retrieval (query), whereas storyline semantics act as potential matching candidates (key) and semantic carriers (value). Through this query–key–value allocation, the model establishes mapping relationships between user preferences and storyline semantics at the dimensional level.

Since video storylines typically contain multiple heterogeneous semantic segments, directly matching the overall semantic vector of a storyline summary, , with user preference , may obscure local semantic variations, thereby limiting the model’s ability to capture latent user preferences. To address this issue, this study uniformly partitions the semantic vector into sub-vectors: .

Each sub-vector corresponds to a local semantic subspace that characterizes fine-grained storyline features. Accordingly, the information retrieval initiated by user preference , the potential matching candidate , and the semantic carrier of the sub-vector of storyline semantics is defined in Equation (9).

To replace the traditional dot product used for similarity computation, this study introduces a learnable similarity kernel, enabling more flexible similarity modeling. Specifically, for user preference vector and storyline semantic vector , the matching score is given by a learnable kernel function in Equation (10).

This study employs the Neural Tensor Kernel, where denotes the -th slice of the tensor kernel, capturing second-order and higher-order interactions between user preferences and storyline semantics. is the number of kernel slices, which controls the dimensionality of higher-order interactions. is the linear mapping matrix, and is the bias term. Unlike fixed inner products, this kernel captures nonlinear high-dimensional correlations, enabling attention weights to better reflect true preference patterns. In contrast to linear, polynomial, or radial basis function kernels, the Neural Tensor Kernel explicitly models second- and higher-order interactions through tensor slices. Its parameterized structure allows the learning of non-uniform interaction patterns across dimensions, making it more suitable for the complex matching process between user preferences and storyline semantics.

The scores are normalized by SoftMax to yield attention weights as shown in Equation (11).

Finally, the representation of the match between user preferences and storyline semantics is obtained through a weighted sum, where denotes the semantic carrier representation of the storyline summary as shown in Equation (12).

The resulting representation, , characterizes the adaptation between high-dimensional user preferences and storyline semantics, offering dual advantages. On the one hand, the learnable similarity kernel addresses the limitations of fixed similarity measures in high-dimensional spaces by dynamically adjusting correlations across semantic dimensions. On the other hand, the cross-attention mechanism models multidimensional feature interactions through weight allocation, enabling user preferences to match the most relevant semantic components within complex structures. The obtained representation not only captures global similarity but also integrates nonlinear cross-dimensional interactions, thereby providing a solid representational foundation for subsequent prediction of user viewing time.

Considering that user experience is also influenced by contextual factors such as viewing time, geographical location, individual heterogeneity, and video metadata, this study aggregates storyline preference–video matching, environmental variables, user demographic features, and video-level features through the fully connected neural network defined in Equation (13), thereby constructing the perceived experience of user for video at time , denoted as .

3.4. Viewing Engagement Prediction

In examining the interrelationships among user satisfaction, expectation, and perceived experience under the framework of ECT, this study adopts a polynomial testing method in the form of following [30]. Specifically, Equation (14) measures the degree of confirmation of perceived experience relative to expectation, and its effect on viewing engagement. Here, denotes the predicted perceived experience of user when watching target long-form video ; denotes the expectation; and represents the confirmation. A positive value indicates positive confirmation (performance exceeds expectation), whereas a negative value indicates negative confirmation (performance falls short of expectation). The sigmoid function maps the result of expectation confirmation to the range . The predicted viewing engagement of user with long-form video at time is denoted as . Unlike prior studies, Equation (9) captures the nonlinear relationship among expectation, perceived experience, and satisfaction. This design reflects the bounded nature of user satisfaction: since satisfaction is inherently upper- and lower-bounded, when confirmation is very high or very low, satisfaction does not increase or decrease indefinitely but asymptotically approaches its limits. Such dynamics align with the diminishing marginal effects implied by nonlinear relationships.

Since recommendation based on viewing engagement in long-form video platforms constitutes an explicit recommendation task, this study adopts the mean squared error (MSE) loss function as the objective function, optimized via stochastic gradient descent. Furthermore, to enhance the capacity of the proposed method in learning and representing high-dimensional video storyline semantics, this study integrates the prediction loss with the contrastive loss as shown in Equation (15). Here, is a hyperparameter that controls the weight of the contrastive loss within the overall objective. This joint optimization not only ensures that the predicted user engagement aligns closely with the observed values but also reinforces the discriminability of storyline embeddings through contrastive learning, such that semantically similar storylines are pulled closer together in the vector space, while dissimilar ones are pushed farther apart.

To alleviate overfitting, an L2 regularization term is applied to constrain the value ranges of trainable parameters within the GRU, cross-attention, attention mechanism, and fully connected neural network, thereby ensuring stability and robustness in model training. Here, and denote the user and long-form video sets in the dataset, respectively, and N represents the batch size.

Based on Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, pseudocode of the forward propagation Algorithm 1 in LVVEP is presented below.

| Algorithm 1: Forward Propagation algorithm in LVVEP |

| Input: sequence of viewing records, ; sequence of viewing engagement, ; sequence of video plot, ; complete set of long-form videos, ; target video, ; block number, ; environment, ; user demographic features, ; video features, . Output: predicted engagement for the target video , |

| 1: |

| 2: # Step 1: Encode historical plots and target video plot |

| 3: |

| 4: |

| 5: # Step 2: Compute semantic similarity between historical and target plots |

| 6: |

| 7: # Step 3: Estimate user expectation on target video |

| 8: |

| 9: |

| 10: |

| 11: # Step 4: Extract dynamic user preference via attention-based GRU |

| 12: Initialize |

| 13: for to do |

| 14: |

| 15: |

| 16: 17: |

| 18: |

| 19: end for |

| 20: |

| 21: # Step 5: Construct Matching degree between user preference and plot semantics |

| 22: 23: for to do |

| 24: 25: 26: 27: end for |

| 28: 29: |

| 30: # Step 6: Predict engagement via confirmation model |

| 31: |

| 32: return |

| 33: end function |

4. Experimental Design

4.1. Experimental Data

To evaluate the performance of LVVEP recommendations, we conduct data-driven experiments based on real long-form video consumption logs. The dataset was provided by a licensed third-party provider, covering the period from 21 June 2018 to 21 June 2019. It contains 19.34 million on-demand viewing records from 100,000 randomly sampled smart terminals. Among these, 15.67 million records are related to TV dramas, and 3.67 million are related to movies. Each log entry includes a de-identified terminal ID, geographic region, program title, program category, tags, director, cast, start time, end time, and other metadata, which provide a detailed and realistic reflection of user consumption behaviors for long-form video.

Since LVVEP leverages narrative text information as a critical input variable, we additionally collect storyline synopses of movies and TV dramas from Baidu Baike, the largest free knowledge platform in China, and DianShiMao, a widely used program guide platform. Missing information is cross-validated and supplemented using Douban, a well-known social media and review platform for films and television. After data consolidation, the final dataset comprises 3.49 million movie viewing records from 20,058 users and 14.38 million TV drama viewing records from 85,909 users.

During data cleaning, we apply several filtering strategies to reduce sparsity. First, long-form videos viewed by fewer than 20 unique users within the one-year window are removed, as are users who have viewed fewer than 10 different long-form videos. This results in 1.54 million movie viewing records from 3873 users and 7.69 million TV drama viewing records from 36,732 users. Second, we collect movie runtimes, per-episode runtimes, and the number of episodes for each TV drama from Baidu Baike and Douban. Following [7], we compute viewing engagement as the ratio of actual viewing duration (derived from log start and end timestamps) to the total duration of the long-form video.

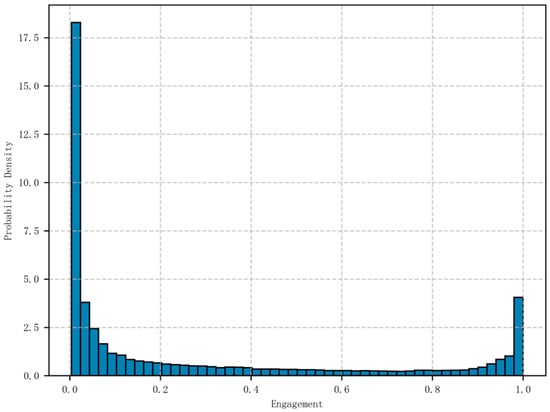

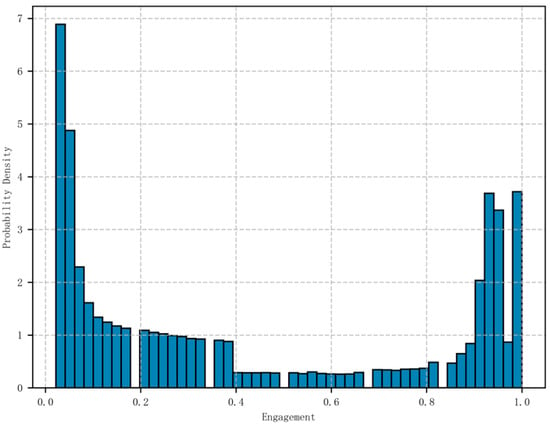

Figure 2 and Figure 3 depict the distributions of viewing engagement for movies and TV dramas. Several observations emerge. First, both categories exhibit bimodal distributions, with user density in the 0–20% quantile significantly higher than in the 80–100% quantile. Second, movie viewing engagement is more polarized: most users either exit quickly or complete the movie, whereas TV drama users are more likely to abandon viewing midway. Finally, movie viewing engagement is relatively continuous, while TV drama engagement is more discrete, with certain levels of engagement rarely observed among users.

Figure 2.

Viewing Engagement Distribution of Movie Users.

Figure 3.

Viewing Engagement Distribution of TV Users.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the performance of LVVEP, we design two evaluation tasks: engagement prediction and recommendation hit rate, examining its effectiveness in enhancing long-form video recommendation.

For engagement prediction, following [40], the continuous engagement scores are discretized into five bins: [0, 0.2], [0.2, 0.4], [0.4, 0.6], [0.6, 0.8], and [0.8, 1]. This transforms the model outputs into categorical labels. Four standard metrics—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score—are employed to evaluate prediction performance.

For recommendation evaluation, LVVEP is applied to the Top-N recommendation task. Due to the nature of sequential recommendation, there is typically only one ground truth, since the true engagement of a user with unseen videos cannot be directly observed. To address this, high-engagement samples are used as the evaluation focus. Based on the bimodal distribution of engagement shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the inflection point at 0.8 is chosen as the threshold to define high engagement. The Hit Rate@N metric, commonly used in Top-N recommendation, is adopted to evaluate recommendation effectiveness. Hit Rate@N is defined in Equation (16), where #hit@N denotes the number of successful hits. A hit occurs if the ground truth item appears within the Top-N recommended list. The denominator represents the total number of recommendation cases in the test set.

4.3. Baselines and Experimental Environment

This study selects both commonly used and state-of-the-art methods in sequential recommendation as baseline models. The non-sequential recommendation methods include RF [41], XGBoost [42], LightGBM [43], DeepFM [44], and DIFM [45], while the sequential recommendation algorithms include GRU4Rec [46], DIN [47], DIEN [17], BST [48], and EDCN [49]. These baselines represent both classical and recent state-of-the-art methods, ensuring fair comparison.

From 21 June 2018 to 20 February 2019, the data were used as the training set; from 21 February 2019 to 20 April 2019, as the validation set; and from 21 April 2019 to 21 June 2019, as the test set. To enhance robustness, forward-chaining cross-validation was performed, in which the dataset was partitioned into successive, chronologically ordered windows. In each fold, all preceding windows were combined as the training set, and the subsequent window served as the validation set for hyperparameter tuning. This design preserves temporal causality and enables a more comprehensive evaluation of model generalization across different time segments, thereby mitigating the risk of overfitting associated with a single data split.

Regarding hyperparameter settings, a consistent strategy is applied to all models by initializing them with the same hyperparameters. Additionally, adaptive learning rate optimization is employed in conjunction with adaptive dropout. During model training, these techniques dynamically adjust the learning rate and dropout ratio in response to the training state of the model, thereby improving its learning ability and predictive accuracy without sacrificing generalization capacity.

Hyperparameters were optimized via grid search, and the configuration that minimized the prediction loss on the validation set was selected. The selected hyperparameters include a sequence length of 20, a GRU hidden dimension of 256, one GRU layer, an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3, 16 blocks, a batch size of 512, a dropout rate of 0.3, an L2 regularization coefficient of 1 × 10−3, a contrastive loss weight of 0.05, a negative sample size for contrastive learning of 32, an AdamW weight decay of 1 × 10−4, and 50 training epochs.

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Main Experimental Results

Table 1 presents the comparison of prediction losses on the testing set between the proposed LVVEP method and the baseline methods after training. Prediction loss directly measures the discrepancy between predicted values and ground truth, thereby providing an effective means to compare the predictive capabilities of the proposed method against the baselines.

Table 1.

Comparison of model prediction loss.

As shown in Table 1, LVVEP demonstrates significant and consistent advantages in prediction loss (MAE and RMSE) across both the movie and television drama datasets. For the movie dataset, LVVEP achieves the lowest MAE (0.187) and RMSE (0.246). Compared with the next-best model, BST (MAE = 0.216, RMSE = 0.279), LVVEP reduces MAE by approximately 13.4% and RMSE by 11.8%. Relative to other strong deep models such as DIN (MAE = 0.251) and DIFM (RMSE = 0.296), the improvements are even more pronounced. In contrast to traditional tree-based models (RF, XGBOOST, LIGHTGBM) and certain deep models (e.g., GRU4Rec, EDCN), LVVEP exhibits a substantial performance margin.

For the television drama dataset, LVVEP likewise achieves the lowest MAE (0.203) and RMSE (0.282). Compared with BST (MAE = 0.222, RMSE = 0.298), LVVEP reduces MAE by approximately 8.6% and RMSE by 5.4%. Overall, across both evaluation metrics (MAE and RMSE) and both datasets (movie and television drama), LVVEP achieves the best results. The substantial reductions indicate that LVVEP can more accurately predict user engagement with unwatched video content, demonstrating strong robustness and generalization capability, and confirming its superior performance in predicting long-form video engagement.

5.2. Prediction Performance

Using Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 as evaluation metrics, this study validates the classification performance of different models in predicting viewing engagement on both the movie and television drama datasets. As shown in Table 2, LVVEP achieves superior prediction performance across multiple evaluation metrics compared with the baseline models.

Table 2.

Comparison of model prediction performance.

The experimental results indicate that, on the movie dataset, LVVEP improves the four metrics by 28.13%, 12.12%, 21.21%, and 16.49%, respectively, showing a significant advantage over the second-best model. On the television drama dataset, the corresponding improvements are 25.00%, 9.09%, 30.00%, and 19.13%, further demonstrating the generalization ability and superiority of LVVEP across different types of datasets.

Although all methods are evaluated on the same datasets, LVVEP distinguishes itself through its theoretically driven paradigm. By jointly modeling user expectations and experiences and explicitly learning their confirmation relationship, LVVEP predicts user engagement while uncovering deeper latent information embedded in user behaviors. In contrast, BST, which ranks second, captures complex associations between historical and target long-form videos through multi-head self-attention, but fails to adequately account for the impact of the match between user preferences and target video attributes on user experience. Compared with DIFM and DeepFM, LVVEP holds a clear advantage since factorization machine-based methods emphasize user–video interactions through field information but overlook sequential dependencies in long-form video consumption, thereby limiting their ability to capture current user preferences. Although DIN and DIEN focus on modeling the evolution of user preferences, they do not sufficiently incorporate the influence of historical engagement levels on preference formation, which diminishes their capacity to identify user engagement intensity.

In summary, the strong performance of LVVEP in viewing engagement prediction not only validates the effectiveness of its algorithmic design but also highlights its potential in understanding user behavior and delivering personalized recommendations, providing solid support for further optimization of recommender systems.

5.3. Recommendation Performance

To evaluate the effectiveness of LVVEP in downstream recommendation tasks, we adopt Hit Rate@N as the key evaluation metric. Experiments are conducted on both the movie and TV series datasets to examine the performance of LVVEP against all baseline models in the Top-N recommendation task, where takes values of 5, 10, and 15. The recommendation results of LVVEP and the baselines are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of Recommendation Systems Performance.

The experimental results demonstrate that LVVEP consistently outperforms other baseline models across Hit Rate@5, Hit Rate@10, and Hit Rate@15. Specifically, on the movie dataset, LVVEP improves upon the second-best model by 7.14%, 10.53%, and 11.54% in Hit Rate@5, Hit Rate@10, and Hit Rate@15, respectively. On the TV series dataset, LVVEP also exhibits superior performance, with improvements of 4.63%, 12.50%, and 16.67% across the same three metrics.

First, across all recommendation algorithms, the Hit Rate metric generally increases with the expansion of the recommendation list length . This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that a longer recommendation list naturally increases the probability of hitting high-engagement ground-truth items. Choosing within the range of 5 to 15 not only aligns with the typical recommendation list length used in practice but also balances relevance and diversity of the recommendations.

Second, although the recommendation system aims to prioritize long-form videos with the highest predicted engagement, the empirical results show that high-engagement items are not exclusively concentrated within the Top-5 positions. For the movie dataset, as the list expands to Top-10 and Top-15, the Hit Rate increases to 0.21 and 0.29, respectively, indicating enhanced capability in capturing high-engagement content with a broader recommendation scope. Similarly, on the TV series dataset, the Hit Rate increases from 0.11 at Top-5 to 0.28 at Top-15, thereby confirming this trend. This phenomenon suggests that while LVVEP is capable of placing a portion of high-engagement long-form videos within the top ranks, a considerable share of such content may appear slightly lower in the recommendation list. This may be attributed to LVVEP’s comprehensive modeling of long-term user history, short-term preferences, and long-form video content features, which expands the recommendation space to offer users a wider selection of relevant items.

In summary, the superior performance of LVVEP in the comparison of recommendation algorithms not only highlights its application potential in long-form video recommendation but also provides new insights for the design and optimization of recommendation systems in this domain.

5.4. Ablation Study

Section 5.1, Section 5.2 and Section 5.3 have demonstrated the performance differences between LVVEP and other deep learning models that do not incorporate ECT theory in terms of prediction loss, engagement prediction, and long-form video recommendation. Once ECT theory is embedded, LVVEP is composed of key modules such as content embedding, expectation, and perceived experience. Analyzing the contribution of these modules is crucial for verifying their effectiveness and for understanding the robustness and generalization of the model—that is, whether LVVEP is overly dependent on specific modules, and in which aspects it exhibits stronger stability, thereby revealing potential bottlenecks and directions for improvement.

The ablation study is conducted by removing or replacing specific modules within LVVEP, under the same tasks and parameter configurations as in Section 5.1. The results are shown in Table 4, with analysis as follows.

Table 4.

Ablation Study Results.

(1) Removing long-form video content. When the long-form video content information is removed, the video representation vector is replaced by the embedding of the video ID. In the expectation module, similarity is calculated based on ID embeddings rather than content similarity. In the perceived experience module, user preferences degenerate into preferences for video IDs instead of video content. Compared with the full model (0), the performance shows substantial drops: on the movie dataset, Accuracy and F1 decrease by 34.15% and 28.95%, respectively; on the TV series dataset, the decreases are 34.43% and 37.84%. This indicates that content information is crucial for model performance.

(2) Replacing similarity with labels. Instead of measuring video similarity via content, we redefine similar videos as those sharing the same label, and user expectation is calculated by aggregating historical engagement with videos of the same label. Compared with (0), on the movie dataset, Accuracy and F1 drop by 18.52% and 22.22%, while on the TV series dataset, the decreases are 19.06% and 30.43%. Although performance degradation exists, it is less severe than in (1), suggesting that content information plays a more significant role than the method of computing expectation.

(3) Removing expectation. Within the ECT framework, expectation negatively impacts satisfaction. To examine its marginal contribution, the expectation module is removed, and only the perceived experience module is used. Compared with (0), on the movie dataset, Accuracy and F1 decrease by 27.78% and 28.13%; on the TV series dataset, the decreases are 22.86% and 17.70%. This shows that expectation contributes positively to performance. The degradation is larger than in (2), implying that even label-based expectation is more effective than removing the expectation module altogether.

(4) Replacing GRU with LSTM. In capturing evolving user preferences, GRU is used to retain positive historical experiences while forgetting less relevant ones. Here, GRU is replaced with LSTM, optimized by attention over the forget and input gates. Compared with (0), on the movie dataset, Accuracy improves by 3.23% but F1 decreases by 3.45%; on the TV series dataset, Accuracy decreases by 3.13% while F1 improves by 3.16%. Overall, (4) performs comparably to (0), but (0) achieves higher Recall (by 9.67% on movies and 3.45% on TV series). This indicates that GRU is more effective in predicting true positives. Nevertheless, the similar performance between GRU and LSTM confirms the robustness of the LVVEP framework—its predictive strength does not stem from the accidental choice of a specific recurrent unit.

(5) Removing perceived experience. Within the ECT framework, perceived experience has a positive effect on satisfaction. To test its marginal contribution, the perceived experience module is removed, leaving only the expectation module. Compared with (0), on the movie dataset, Accuracy and F1 drop drastically by 57.14% and 64.86%; on the TV series dataset, the decreases are even larger, 74.36% and 73.68%, respectively. This represents the most significant degradation among all settings, demonstrating that perceived experience plays a decisive role in predicting user engagement.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

With the increasing abundance of long-form video content, the industry is entering a crucial transition period from scale-driven growth to quality-oriented development. Providing high-quality information services and alleviating information overload has become essential for optimizing platform operations and fostering the sustainable growth of the long-form video industry. As the core component of information services, recommender systems play a pivotal role in helping users efficiently filter high-quality content and enhancing their overall viewing experience.

Existing long-form video recommender systems rarely incorporate user engagement as a key metric. To address this gap, this study proposes LVVEP, a long-form video recommendation method grounded in user engagement prediction. Based on Expectation-Confirmation Theory (ECT), user satisfaction and continuous usage intention are determined by the consistency between their expectations and perceived experiences. By analyzing user viewing behaviors and the narrative content of long-form videos, LVVEP separately models users’ expectations and perceived experiences of unseen videos and predicts their engagement levels. The resulting predictions are used to generate personalized recommendations. Extensive experiments on real-world long-form video datasets demonstrate that LVVEP outperforms both classical and state-of-the-art baseline models in recommendation effectiveness and predictive performance. Ablation studies further confirm the marginal contribution and generalization ability of each module, highlighting the robustness of the proposed framework.

This study makes three key contributions. First, by introducing a recommendation approach based on user engagement, it enriches theoretical research on long-form video recommender systems and empirically validates engagement as a critical factor for improving system performance, thereby providing new insights and tools for platform managers. Second, the innovative integration of ECT into recommendation system design enables a deeper analysis of user expectations and perceived experiences, enhancing both the relevance and accuracy of recommendations while offering theoretical support for improving user satisfaction and experience optimization. Third, experiments on real datasets verify the superior performance of LVVEP across different types of long-form video and multiple key evaluation metrics, offering empirical evidence for strategy design and practical guidance for platform managers seeking to improve content recommendation and user retention. These findings not only advance academic research on long-form video information services but also provide actionable strategies for commercial practice, helping platforms strengthen their competitiveness in capturing audience attention and achieve sustainable industry development.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. First, while external factors such as buzz or social trends may influence user expectations to some extent, their impacts are highly context-dependent and heterogeneous across users. To maintain theoretical coherence and model interpretability, LVVEP focuses on the intrinsic expectation–experience mechanism grounded in user–content interactions. This design ensures that the model captures the stable cognitive foundation of expectation formation while leaving open the possibility of integrating exogenous social or cultural signals in future extensions of the framework. Second, the proposed method has not yet been deployed on large-scale industrial platforms. Future research should include experiments on large-scale datasets and computational performance evaluation to validate scalability and efficiency. In addition, future empirical studies can leverage LVVEP as a validation model to infer the specific relationships among user expectations, perceived experiences, and satisfaction in real-world recommendation scenarios. Finally, while LVVEP has been validated in the domain of long-form video recommendation, its design as an engagement-driven predictive framework can potentially be extended to other domains, providing opportunities to explore user engagement prediction in broader application contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; Methodology, Y.C.; Software, Y.C.; Validation, Y.C.; Formal analysis, Y.C.; Investigation, Y.C.; Resources, Y.C.; Data curation, Y.C.; Writing—original draft, Y.C.; Writing—review & editing, Y.C. and J.Z.; Visualization, Y.C.; Supervision, Y.C.; Project administration, Y.C.; Funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECT | Expectation-Confirmation Theory |

| LVVEP | Long-Form Video Viewing Engagement Prediction |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

References

- Batmaz, Z.; Yurekli, A.; Bilge, A.; Kaleli, C. A review on deep learning for recommender systems: Challenges and remedies. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J. The economics of movies (revisited): A survey of recent literature. J. Econ. Surv. 2023, 37, 480–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chiu, D.M. A study of user behavior in online VoD services. Comput. Commun. 2014, 46, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymäki, M.; Islam, A.N.; Benbasat, I. What drives subscribing to premium in freemium services? A consumer value-based view of differences between upgrading to and staying with premium. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 295–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chen, X.; Song, L.; Liu, J.; Li, B.; Jiang, P. Tree based progressive regression model for watch-time prediction in short-video recommendation. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, R.; Pei, C.; Su, Q.; Wen, J.; Wang, X.; Mu, G.; Zheng, D.; Jiang, P.; Gai, K. Deconfounding duration bias in watch-time prediction for video recommendation. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran, A.; Sekar, V.; Akella, A.; Seshan, S.; Stoica, I.; Zhang, H. Developing a predictive model of quality of experience for internet video. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2013, 43, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-C.; Wu, S.; Hsu, J.S.-C.; Chou, Y.-C. The integration of value-based adoption and expectation–confirmation models: An example of IPTV continuance intention. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyaswamy, V.; Logesh, R.; Chandrashekhar, M.; Challa, A.; Vijayakumar, V. A personalised movie recommendation system based on collaborative filtering. Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Netw. 2017, 10, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Thakkar, A.; Gupta, V.; Rathore, D.P.S. Movie recommender system using collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electronics and Sustainable Communication Systems (ICESC), Coimbatore, India, 2–4 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.; Krishnan, R.; Duncan, G.; Callan, J. Research note—The halo effect in multicomponent ratings and its implications for recommender systems: The case of yahoo! movies. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Kim, S.B. Content-based filtering for recommendation systems using multiattribute networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 89, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Larson, M.; Hanjalic, A. Mining contextual movie similarity with matrix factorization for context-aware recommendation. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2013, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chung, F.-L.; Jiang, W.; Ester, M.; Liu, W. A deep Bayesian tensor-based system for video recommendation. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. (TOIS) 2018, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Mou, N.; Fan, Y.; Pi, Q.; Bian, W.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, X.; Gai, K. Deep interest evolution network for click-through rate prediction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Wang, Y. A novel learning rate function and its application on the SVD++ recommendation algorithm. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 14112–14122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Cai, G.; Zhu, J.; Dong, Z.; Xu, J.; Wen, J.-R. Counteracting Duration Bias in Video Recommendation via Counterfactual Watch Time. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrian, F.; Sekar, V.; Awan, A.; Stoica, I.; Joseph, D.; Ganjam, A.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, H. Understanding the impact of video quality on user engagement. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2011, 41, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, S.; Calheiros, R.N.; Yang, F. Survey on QoE assessment approach for network service. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 48374–48390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zheng, D.; Zhao, B.Y.; Zheng, W. Understanding user behavior in large-scale video-on-demand systems. ACM SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 2006, 40, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiche, F.; Ben Letaifa, A.; Elloumi, I.; Aguili, T. When machine learning algorithms meet user engagement parameters to predict video QoE. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 116, 2723–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.C.; Brock, T.C. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, U.; Landesman, O.; Knappmeyer, B.; Vallines, I.; Rubin, N.; Heeger, D.J. Neurocinematics: The neuroscience of film. Projections 2008, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Wu, C.-H. Effects of different video lecture types on sustained attention, emotion, cognitive load, and learning performance. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, M.A.; Keller, T.A.; Cynkar, J. A decrease in brain activation associated with driving when listening to someone speak. Brain Res. 2008, 1205, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Audience identification with media characters. In Psychology of Entertainment; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; Venkatesh, V.; Goyal, S. Expectation confirmation in information systems research. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 729–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Men, J. Recommendation content matters! Exploring the impact of the recommendation content on consumer decisions from the means-end chain perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.-m.; Zhang, J.-h.; Chan, F.T. Determinants of loyalty to public transit: A model integrating Satisfaction-Loyalty Theory and Expectation-Confirmation Theory. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, F.; Men, J. Understanding consumers’ continuance intention toward recommendation vlogs: An exploration based on the dual-congruity theory and expectation-confirmation theory. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 59, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, Z.; Ma, K.; Wang, Z. Quality-of-experience for adaptive streaming videos: An expectation confirmation theory motivated approach. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 6135–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- GLM, T.; Zeng, A.; Xu, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Yin, D.; Zhang, D.; Rojas, D.; Feng, G.; Zhao, H. Chatglm: A family of large language models from glm-130b to glm-4 all tools. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.12793. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Wu, F.; Huang, Y. Rethinking infonce: How many negative samples do you need? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical evaluation of gated recurrent neural networks on sequence modeling. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.3555. [Google Scholar]

- Bampis, C.G.; Li, Z.; Katsavounidis, I.; Bovik, A.C. Recurrent and dynamic models for predicting streaming video quality of experience. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3316–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 3149–3157. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3294996.3295074 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; He, X. DeepFM: A factorization-machine based neural network for CTR prediction. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.04247. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Yu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Yuan, B. A dual input-aware factorization machine for CTR prediction. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth International Conference on International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence, Yokohama, Japan, 7–15 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hidasi, B. Session-based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06939. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, X.; Song, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, Y.; Jin, J.; Li, H.; Gai, K. Deep interest network for click-through rate prediction. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Lian, J.; Mahmoody, A.; Liu, G.; Xie, X. Adaptive User Modeling with Long and Short-Term Preferences for Personalized Recommendation. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, R.; Guo, W.; Zheng, H.; Yao, W.; Zhang, M.; He, X. Enhancing explicit and implicit feature interactions via information sharing for parallel deep CTR models. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Gold Coast, Australia, 1–5 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).