Featured Application

The findings of this study can be applied to the design of small- and medium-scale vertical axis wind turbines intended for urban or low-wind environments, where efficient start-up and improved energy capture are critical. The use of cavity-modified polycarbonate blades provides a practical pathway for lightweight, cost-effective, and easily manufacturable turbines, supporting the wider deployment of renewable energy solutions in distributed power generation and off-grid applications.

Abstract

Vertical axis wind turbines (VAWTs) have significant potential for renewable energy generation, yet their operational efficiency is often limited by reduced aerodynamic performance and difficulties during start-up. This study investigates the effect of passive flow control and material selection on the performance of H-Darrieus VAWT blades, with the aim of identifying design solutions that enhance start-up dynamics and overall efficiency. Two-dimensional numerical simulations were conducted using the Dynamic Mesh method with six degrees of freedom (6DOF) in ANSYS 19.2 Fluent, enabling a time-resolved assessment of rotor behavior under constant wind velocities. Two blade configurations were analyzed: a baseline NACA0012 geometry and a modified profile with inclined cavities on the extrados. In addition, the influence of blade material was examined by comparing 3D-printed resin blades with lighter 3D-printed polycarbonate blades. The results demonstrate that cavity-modified blades provide superior performance compared to the baseline, showing faster acceleration, higher tip speed ratios, and improved power coefficients, particularly at higher wind velocities. Furthermore, polycarbonate blades achieved more efficient energy conversion than resin blades, highlighting the importance of material properties in turbine optimization. These findings confirm that combining passive flow control strategies with advanced lightweight materials can significantly improve the aerodynamic and dynamic performance of VAWTs, offering valuable insights for future experimental validation and prototype development.

1. Introduction

The continuous increase in global energy demand, coupled with the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, has intensified research on renewable energy technologies. Among these, wind energy represents one of the most promising alternatives due to its scalability and abundance. Unlike horizontal-axis wind turbines, VAWTs offer unique advantages for distributed generation, urban deployment, and turbulent wind environments due to their omni-directional operation and simpler structural design [1,2]. However, their widespread adoption remains limited by intrinsic aerodynamic challenges such as dynamic stall, low self-starting capability, and torque fluctuations [3,4]. These issues have been extensively discussed in critical reviews that emphasize the need for innovative aerodynamic control strategies and advanced numerical methodologies to unlock the full potential of VAWTs [1,2,3].

Recent comprehensive reviews have also highlighted the broader challenges and opportunities facing the wind-energy sector as a whole. Ligeza [5] outlined the current and forecasted technological trends in wind power generation, emphasizing the need for integrated design approaches, advanced control systems, and improved aerodynamic efficiency in both large-scale and small-scale turbines. Similarly, Roga et al. [6] reviewed the latest developments in turbine technology and energy-harvesting methods, underlining the importance of novel passive and hybrid flow-control concepts for enhancing performance at low and moderate wind velocities. Together, these works reinforce the necessity for continued innovation in aerodynamic optimization and flow-management strategies, providing the foundation for the approach proposed in the present study.

Several approaches have been proposed to enhance the aerodynamic performance and dynamic behavior of VAWTs. Passive flow control has attracted significant attention due to its simplicity and low operational cost. Strategies such as guided vane integration [7], leading-edge slot structures [8], and modifications including groove-flap and concave cavity designs [9] have demonstrated measurable improvements in lift, torque, and power coefficients. Other investigations have explored novel airfoil geometries, such as J-blades [10], confirming that careful aerodynamic tailoring can mitigate stall and boost efficiency. Comprehensive reviews [11,12,13,14] further highlight the effectiveness of passive devices while also stressing the risk of added drag and mechanical complexity, indicating that performance gains are strongly dependent on design optimization and operating conditions.

Parallel to geometric innovations, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a cornerstone for VAWT design, enabling detailed insight into complex unsteady flows. Recent advances include transient Dynamic Mesh simulations to capture lateral vortices and Strouhal number effects [15], systematic CFD optimization methods based on Taguchi design [16], and hybrid analytical–CFD frameworks for torque and power prediction [17]. Reviews of CFD methodologies stress the importance of turbulence modeling, with the k–ω SST model frequently employed for its balance between near-wall resolution and free-stream accuracy [18]. These approaches have been used to study dynamic stall, blade–vortex interaction, and flow-control effectiveness, offering increasingly accurate predictions of start-up and steady-state turbine behavior [18,19].

Despite these advances, the issue of self-starting remains one of the most critical barriers for small and medium-sized VAWTs. Strategies ranging from aerodynamic tailoring to passive and active flow control have been systematically reviewed [6], with many studies converging on the conclusion that improving self-starting requires balancing mass, inertia, and aerodynamic efficiency. Experimental studies [9] and CFD investigations [10,15] both confirm that material properties and blade mass distribution play a decisive role in determining the transient response during start-up. Additionally, experimental and numerical studies indicate that heavier blades, such as those made from resin composites, may hinder acceleration at low wind speeds, whereas lighter alternatives, including advanced polymers or 3D-printed materials, can improve dynamic responsiveness [15,19]. Nonetheless, systematic investigations that combine passive flow control with material optimization remain limited in the current literature.

The present study addresses this gap by performing a comparative numerical analysis of straight-bladed VAWTs using the Dynamic Mesh method in ANSYS Fluent. Two geometrical configurations were considered: a baseline NACA0012 profile and a modified profile incorporating inclined cavities on the extrados. The current investigation compares results for the mass of 3D printed resin blades and blades manufactured from modified polycarbonate filament produced also by 3D printing, enabling a direct assessment of how blade material influences start-up behavior, tip speed ratio, and power coefficient. The results highlight the combined effect of passive flow control and material selection, showing that cavity-modified polycarbonate blades exhibit superior start-up dynamics and enhanced aerodynamic performance compared to both resin blades and unmodified profiles.

With this approach, two complementary aspects—blade geometry and material selection—are examined simultaneously to capture their combined influence on start-up dynamics and energy conversion efficiency. Unlike most existing studies, which treat these parameters separately or under simplified steady-state assumptions, the current work integrates passive flow control through inclined cavities with mass–inertia effects derived from measured material properties within a unified 6DOF framework. This dual-parameter approach enables a physically realistic prediction of turbine behavior, from acceleration to steady operation, under varying wind conditions.

By integrating geometric and material considerations, this work contributes to the broader understanding of VAWT optimization. The findings provide actionable insights for the design of lightweight, high-performance turbines suited for urban and distributed renewable energy applications, while also informing future experimental validation and prototype development.

In recent years, the frontier of numerical and experimental research has increasingly shifted toward the integration of high-fidelity modeling, data-driven optimization, and multi-field coupling techniques. Examples include the use of virtual-sample calibration combined with autoencoder architectures for enhanced sensor accuracy in complex thermal systems [20], as well as multi-field particle–flow coupling and ultrasonic control methods applied in microreactor environments [21]. Although these studies address different engineering domains, they share a common objective: to achieve more adaptive, accurate, and physics-informed modeling frameworks. In alignment with these advances, the present work extends high-fidelity transient modeling to the renewable energy sector by coupling aerodynamic flow phenomena with real-time inertial dynamics in a six-degree-of-freedom framework, thereby contributing to the broader movement toward intelligent, fully coupled simulation methodologies.

2. Materials and Methods

This study evaluated the aerodynamic performance of a VAWT equipped with modified airfoil blades fabricated from polycarbonate filament in comparison with resin blades, using transient CFD simulations in ANSYS 19.2 Fluent.

2.1. Computational Domain and Grid

The turbine rotor was modeled as an H-Darrieus configuration with the following main dimensions, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The geometric characteristics of the studied H-Darrieus VAWT.

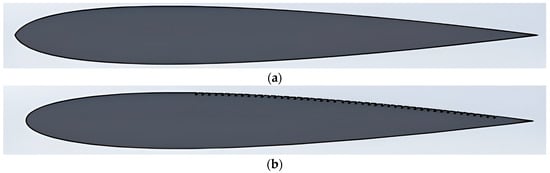

Two blade geometries were studied: a baseline case–NACA0012 profile and a modified case–NACA0012 with tilted orifices introduced along the extrados. These are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Studied blade geometries. (a) Baseline case—NACA0012; (b) Modified case—NACA0012 with tilted orifices on the last two-thirds of the chord (orifice opening = 0.003c; spacing between orifices = 0.01c; orifice depth = 0.005c).

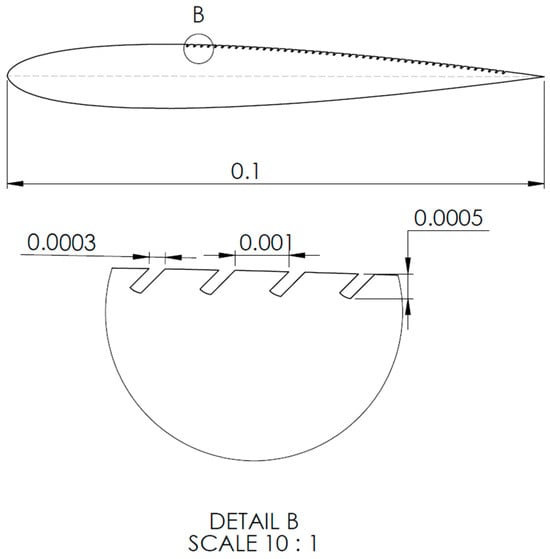

The modified case was derived from a NACA0012 profile by introducing a series of 46 tilted orifices (45° inclination, promoting passive flow reattachment and delayed separation) distributed along the last two-thirds of the chord. Each orifice has an opening diameter of 0.0003 m, a spacing of 0.001 m, and a depth of 0.0005 m, positioned on the extrados surface. These details are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Modified NACA0012 profile.

The dimensions and layout of the tilted cavities were established based on the authors’ previous parametric investigations of NACA0012 airfoil modified with inclined cavities [22,23]. Those studies evaluated several combinations of cavity size, spacing, and placement, concluding that the most effective configuration consisted of tilted cavities inclined at 45°, positioned on the last two-thirds of the upper surface. Each cavity featured an opening diameter of 0.003*c, a spacing of 0.01*c, and a depth of 0.005*c, where c is the blade chord. The results of these investigations, which included flow visualizations, demonstrated how the cavities promote flow reattachment and delay separation, leading to a significant lift increase without a noticeable drag penalty. Since the aerodynamic mechanism and local flow behavior around the cavities have already been illustrated and discussed extensively in those works, only turbine-scale aerodynamic results are presented in the current paper. Consequently, these validated geometric characteristics were adopted here as the reference passive-flow-control configuration.

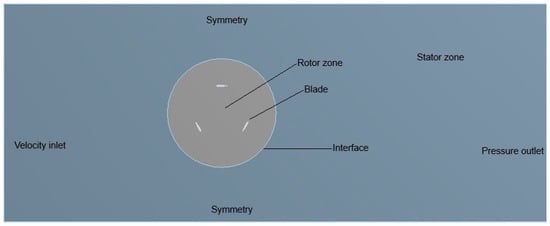

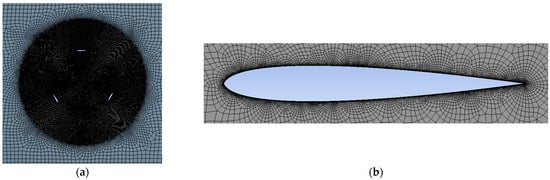

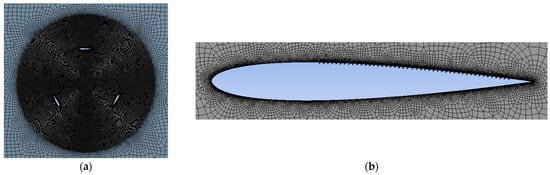

The computational grid was generated in ANSYS Meshing and a hybrid grid was adopted: structured quadrilateral elements were applied around the airfoil blades to ensure boundary layer resolution, while a combination of quadrilateral and triangular unstructured elements was used in the rotor and stator zones. The computational domain was divided into two regions: rotor zone, including the blades, rotor fluid volume, and rotor/stator interface; and stator zone, representing undisturbed airflow, including inlet velocity, outlet pressure, symmetry planes, and the stator fluid volume. The computation domain is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Computational domain.

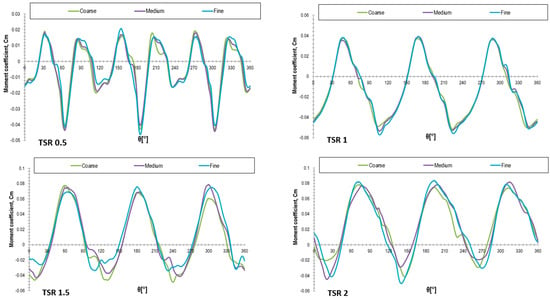

The rotor/stator setup replicated wind tunnel conditions, with a unidirectional airflow from left to right. The “Quadrilateral Dominant” method was used for meshing, and inflation layers (10 boundary layers) were added around the blades to capture near-wall effects. The first cell height at the wall was determined using the flat-plate boundary layer theory [24], resulting in a calculated value of 6.822 × 10−5 m corresponding to y+ ≅ 1. For the final computational grids, a slightly refined first-layer spacing of Δy = 1 × 10−5 m was employed for both the airfoil and the cavity walls to ensure proper near-wall resolution. Furthermore, the mesh was locally refined along the airfoil and cavity walls, as well as around the orifice rims, using inflation layers and quadrilateral elements. The resulting mesh ensured high-quality boundary-layer capture and numerical stability throughout the unsteady simulations. To verify that the numerical solution is independent of the spatial discretization, a mesh-independence study was performed based on literature best practices for vertical axis wind turbines [25]. Three computational grids were generated for the baseline: a coarse grid with 90,488 elements and 94,216 nodes, a medium grid with 134,648 elements and 139,004 nodes, and a fine grid with 201,763 elements and 206,854 nodes. All grids maintained the same first-cell height near the wall while varying the number of elements along edges and surfaces. The baseline model was evaluated using, for the mesh independency study, Moving Mesh approach at 10 m/s wind speed for tip-speed-ratio values between 0.5 and 3.5. A comparison of the results showed negligible differences between the coarse, medium and fine grids throughout the entire TSR range, as depicted in Figure 4. The maximum variation in the moment coefficient was below 2%, confirming that the solution is mesh-independent. Consequently, the fine grid was adopted for all subsequent analyses.

Figure 4.

Moment coefficient variation for different grid sizes.

For the Dynamic Mesh study, the baseline model had 201,763 elements and 206,854 nodes, whereas the one for the blades with tilted cavities had 389,797 elements and 407,171 nodes. The generated computational grid is shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Mesh for baseline wind turbine: (a) rotor and (b) near blade.

Figure 6.

Mesh for modified wind turbine: (a) rotor and (b) near blade.

2.2. Turbulence Model and Solver Settings

The k–ω Shear Stress Transport (SST) model was selected for the numerical analysis due to its proven capability to accurately predict separated and adverse-pressure-gradient flows in rotating aerodynamic systems. It combines the advantages of the standard k–ω model near walls with the k–ε formulation in fully turbulent regions, through a set of blending functions, ensuring robust performance across the entire computational domain. The k–ω SST approach has been extensively validated for wind-turbine applications, providing accurate predictions for VAWT aerodynamics [26,27]. The SIMPLE algorithm was used for pressure–velocity coupling, with second-order spatial discretization for momentum and turbulence quantities. Simulations employed a time step of 0.0005 s, with up to 50 iterations per step, corresponding to 120,000 time steps (≅60 s physical time) per case, sufficient for reaching steady periodic rotor motion.

2.3. Dynamic Mesh Setup

The turbine blades and rotor zone were defined as rigid bodies within the Dynamic Mesh framework with six degrees of freedom (6DOF). Blade motion was determined by their mass and inertia properties, derived from the fabricated 3D-printed polycarbonate blades and 3D-printed resin blades, respectively. This data is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mass and inertia properties for the studied models.

The rotor zone was coupled passively to blade motion, while the stator was fixed. The 6DOF solver tracked blade displacement and angular velocity in response to aerodynamic loads, allowing the turbine’s self-starting behavior and dynamic equilibrium to be evaluated.

For each blade geometry and material configuration, five inlet wind speeds were investigated: 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 m/s. Boundary conditions were applied as described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Boundary conditions.

For each time step, blade angular displacement was recorded. The angular velocity was computed as the change in displacement over time, which was then used to determine the tip speed ratio (TSR), torque coefficient (cm), power coefficient (cp), and output power (P). The turbine was considered to have reached equilibrium once TSR values stabilized, corresponding to a constant angular velocity.

3. Results

By employing the Dynamic Mesh function, it was possible to record the blade position at each time step. Based on this data, the difference in position between consecutive steps was calculated, and once this difference became constant, the turbine was considered to have reached an equilibrium state, rotating with a constant angular velocity. The angular velocity () was computed as the ratio between the change in blade position (in radians) and the time step (in seconds).

Knowing the angular velocity, it was then possible to determine the velocity coefficient (λ) for each case using the following standard expression:

In parallel, the torque coefficient () was monitored throughout the simulation and numerically evaluated. Based on its values and the TSR, the power coefficient () was subsequently calculated, allowing a direct assessment of the aerodynamic efficiency of the turbine under different configurations and material properties.

Having these coefficients available, the moment (torque—M) and the power of the turbine (P) could be directly determined, thus providing a comprehensive evaluation of its performance. The involved parameters are [kg/m3]—air density; A—rotor area [m2]; V∞ [m/s]—wind speed; R [m]—turbine radius.

The results for each model under study are summarized in the following tables, which include the calculated values of angular velocity, tip speed ratio, torque coefficient, and power coefficient, as well as the corresponding torque and power. These datasets enable a direct comparison between the different geometrical configurations and blade materials, highlighting the influence of the introduced modifications on the turbine’s overall performance.

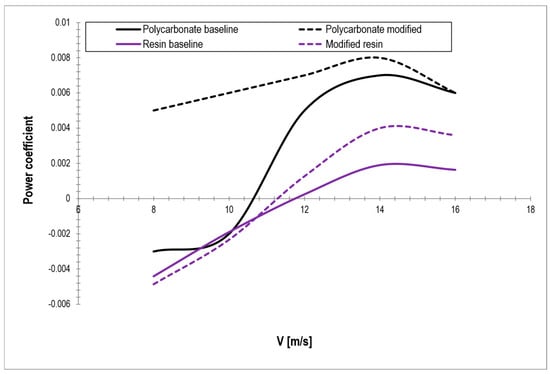

To better visualize the results, Figure 7 illustrates the variation in the power coefficient as a function of wind speed for blades manufactured from resin and modified polycarbonate, both in the baseline configuration and in the configuration with orifices.

Figure 7.

Power coefficient variation with wind speed.

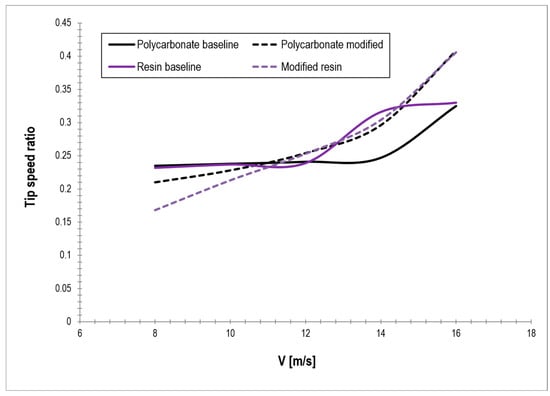

Furthermore, Figure 8 presents the evolution of the tip speed ratio with wind speed for the same cases, offering a complementary perspective on the dynamic behavior of the turbine.

Figure 8.

Tip speed ratio variation with wind speed.

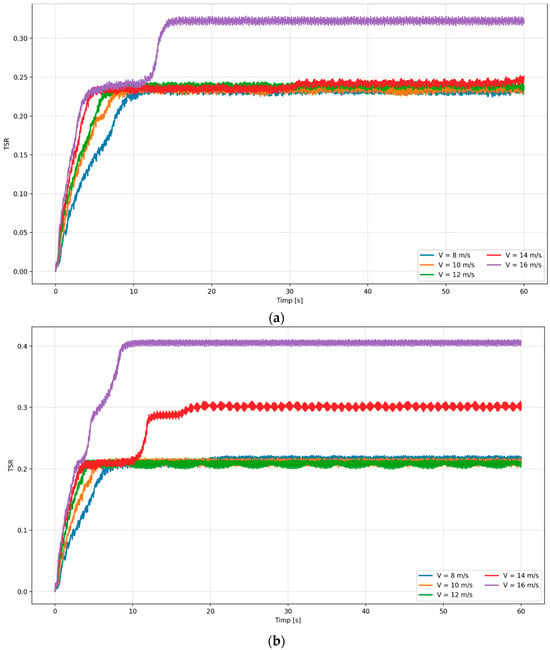

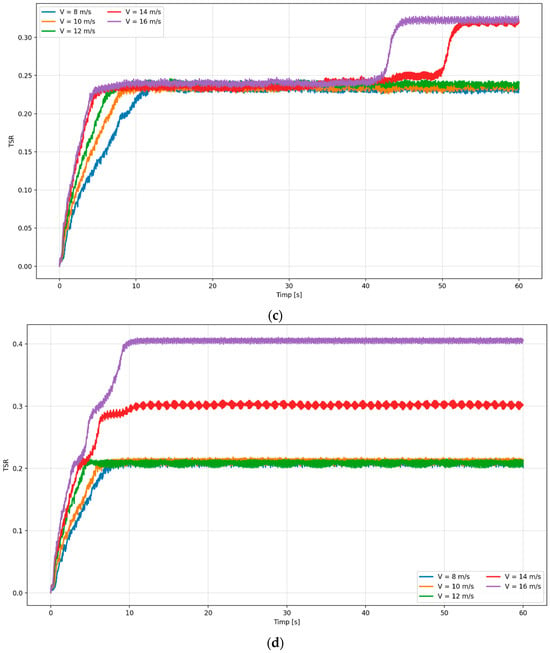

To evaluate the dynamic behavior of the turbine, the time evolution of the tip speed ratio (TSR) was monitored at different wind speeds for both blade materials (resin and modified polycarbonate). The results, illustrated in Figure 9, allow for a direct comparison between the evolution and stabilization of TSR values for the two geometries, as influenced by the imposed flow conditions.

Figure 9.

Tip speed ratio variation with time. (a) Polycarbonate blades—baseline case; (b) Polycarbonate blades—modified case; (c) Resin blades—baseline case; (d) Resin blades—modified case.

4. Discussion

The numerical results for the baseline and modified blades fabricated from polycarbonate and resin are summarized in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. For polycarbonate blades, the baseline configuration shows relatively low power coefficients at low wind speeds (negative values at 8–10 m/s), but performance improves significantly at higher speeds, reaching a maximum power coefficient of 0.007 at 14 m/s. These results are in accordance with those from similar studied for small VAWTs [7]. As mentioned, at lower wind velocities, the simulations produced negative torque and power coefficients. This behavior is characteristic of the self-starting phase of H-Darrieus VAWTs and indicates that the turbine operates temporarily in a drag-dominated regime. During this phase, the blades encounter highly unsteady flow conditions and dynamic stall. These transient effects lead to a negative torque until sufficient angular velocity is reached for the flow to stabilize around the airfoils, after which the turbine transitions into a lift-driven regime with positive torque and power generation. Such behavior has also been reported in previous experimental and numerical studies [6,10], confirming that negative torque and power coefficients at low wind speeds are a physically expected feature of small Darrieus-type turbines rather than a numerical error.

Table 4.

Baseline blades—3D-printed polycarbonate blades.

Table 5.

Modified blades—3D-printed polycarbonate blades.

Table 6.

Baseline blades—3D-printed resin blades.

Table 7.

Modified blades—3D-printed resin blades.

The modified polycarbonate blades with inclined orifices demonstrate higher performance across all velocities, with power coefficient peaking at 0.008. In comparison, the resin blades exhibit overall lower aerodynamic efficiency [6,10]. The baseline resin case shows negligible or even negative power at low wind speeds and modest improvement at higher velocities, with power coefficients not exceeding 0.0019. However, the modified resin blades show some performance recovery at higher velocities, reaching a power coefficient value of 0.004 at 14 m/s, but still remain below the levels of the polycarbonate models. These results confirm that both the material properties (lighter polycarbonate vs. heavier resin) and the passive flow control modification (orifices) strongly influence turbine self-starting capability and power generation.

To better visualize these results, Figure 5 illustrates the variation in the power coefficient with wind speed for both polycarbonate and resin blades, in baseline and modified configurations. It can be observed that polycarbonate blades consistently outperform resin blades, with modified designs achieving the highest values. The presence of orifices contributes to better startup characteristics and improved efficiency at moderate wind speeds, confirming the effectiveness of passive flow control.

Figure 6 shows the evolution of the tip speed ratio with wind speed. The modified polycarbonate blades achieve the highest TSR values, reaching 0.40 at 16 m/s, compared to 0.33 for the resin baseline. In general, TSR increases with wind speed for all cases, but polycarbonate blades demonstrate both higher peak values and more stable growth compared to resin blades.

To assess the dynamic response of the turbine, the time evolution of TSR was analyzed at different wind speeds (8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 m/s) for all configurations (Figure 7). For the polycarbonate baseline, TSR stabilizes quickly but at lower values, while the modified polycarbonate blades achieve faster acceleration and higher equilibrium TSR, especially at 14–16 m/s. Resin blades show slower stabilization and lower equilibrium values, with the modified design offering partial improvement but still underperforming compared to polycarbonate. The time-history evolution of the TSR reflects the interplay between aerodynamic torque generation and rotor inertia during the turbine’s self-starting and steady-state phases. In the early seconds of each simulation, the rotor is nearly stationary and the blades encounter very high instantaneous angles of attack, resulting in drag-dominated torque and dynamic-stall cycles. This stage produces the steep initial rise in TSR visible for all wind speeds. As the rotational velocity increases, the relative inflow angle decreases and the blades progressively transition from separated to attached flow, marking the shift from a drag- to a lift-driven regime. The subsequent flattening of the TSR curves corresponds to the moment when aerodynamic torque and resistive torque (mainly viscous and inertial) reach equilibrium. The higher final TSR values observed for the modified blades arise from the tilted cavities, which delay separation and promote reattachment, increasing the net positive torque once the lift mechanism dominates. Differences between resin and polycarbonate blades are linked to inertia: the lighter polycarbonate blades accelerate faster and achieve higher steady TSR because of their lower rotational moment of inertia.

The results highlight two decisive factors in the aerodynamic performance of the studied VAWTs. First, the material influence: lighter polycarbonate blades exhibit faster acceleration and reach higher TSR values compared to resin blades, owing to their reduced inertia, which enhances the dynamic response of the turbine. Second, the geometric modification: the addition of inclined orifices on the extrados proves effective as a passive flow control strategy, improving startup behavior and sustaining higher aerodynamic efficiency across operating conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comparative numerical investigation of VAWTs equipped with baseline and cavity-modified blades fabricated from resin and polycarbonate. Using the Dynamic Mesh approach with six degrees of freedom in ANSYS Fluent, the analysis demonstrated that both blade geometry and material selection have a decisive influence on turbine performance.

The results showed that lighter polycarbonate blades achieved faster acceleration and higher tip speed ratios than their resin counterparts, highlighting the importance of reduced inertia for improving dynamic response and start-up capability. Furthermore, the introduction of inclined cavities along the extrados proved to be an effective passive flow control strategy, enhancing aerodynamic efficiency and increasing the power coefficient across a wide range of wind speeds. When combined, these two design considerations—lightweight material and cavity modification—produced the most favorable performance, indicating a promising pathway for optimizing small- and medium-scale VAWTs intended for urban and distributed energy applications.

While the present investigation provides valuable insight into the aerodynamic and dynamic behavior of modified VAWTs, it is limited to two-dimensional CFD simulations that neglect three-dimensional flow effects. Moreover, experimental validation has not yet been performed at this stage. Future work will focus on the experimental validation of the numerical findings through dedicated wind tunnel tests of the fabricated blade models. These tests will provide further insight into the real-world aerodynamic behavior, confirm the reliability of the numerical predictions, and support the development of scalable prototypes suitable for practical deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-O.B. and D.-E.C.; methodology, I.-O.B. and M.-C.D.; software, I.-O.B.; validation, D.-E.C. and M.-C.D.; formal analysis, I.-O.B. and M.-C.D.; investigation, I.-O.B.; resources, D.-E.C.; data curation, I.-O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.-O.B.; writing—review and editing, D.-E.C. and M.-C.D.; supervision, D.-E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Doctoral School of Aerospace Engineering, Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, National University of Science and Technology Polytechnic of Bucharest. This article was funded by the PubArt program of the National University of Science and Technology Polytechnic of Bucharest.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results is available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Doctoral School of Aerospace Engineering, Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, National University of Science and Technology Polytechnic of Bucharest.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VAWT | Vertical Axis Wind Turbine |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| TSR | Tip Speed Ratio |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport turbulence model |

References

- Kumar, R.; Raahemifar, K.; Fung, A.S. A critical review of vertical axis wind turbines for urban applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Gutierrez, B.; Sanchez-Cortez, L.; Hinojosa-Manrique, M.; Lozada-Pedraza, A.; Ninaquispe-Soto, M.; Montaño-Pisfil, J.; Gutiérrez-Tirado, R.; Chávez-Sánchez, W.; Romero-Goytendia, L.; Díaz-Aliaga, J.; et al. Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines in Emerging Energy Applications (1979–2025): Global Trends and Technological Gaps Revealed by a Bibliometric Analysis and Review. Energies 2025, 18, 3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolahifar, A.; Zanj, A. Addressing VAWT Aerodynamic Challenges as the Key to Unlocking Their Potential in the Wind Energy Sector. Energies 2024, 17, 5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Molina, J.S.; Chavero-Navarrete, E. A Systematic Review of Technological Strategies to Improve Self-Starting in H-Type Darrieus VAWT. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligeza, P. Basic, Advanced, and Sophisticated Approaches to the Current and Forecast Challenges of Wind Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 8147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roga, S.; Bardhan, S.; Kumar, Y.; Dubey, S.K. Recent technology and challenges of wind energy generation: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelezz, A.; Ghali, H.; Elbayomi, G.; Madboli, M. A novel VAWT passive flow control numerical and experimental investigations: Guided Vane Airfoil Wind Turbine. Ocean Eng. 2022, 257, 111704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhan, L.; Kuang, L.; Yushan, R.; Tu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Su, J.; Han, Z.; Zhou, D. Passive flow control technique for enhancing power efficiency of vertical-axis wind turbines: Leading-edge slot structure. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Chen, Y.; Song, L.; Xing, Y.; Wang, B.; Sun, Y. Experimental Study on the Influence of Groove-Flap and Concave Cavity on the Output Characteristics of Vertical Axis Wind Turbine. Fluids 2025, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; William, M.A.; Moharram, N.A.; Zidane, I.F. Boosting H-Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine performance: A CFD investigation of J-Blade aerodynamics. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syawitri, T.P.; Yao, Y.; Yao, J.; Chandra, B. A review on the use of passive flow control devices as performance enhancement of lift-type vertical axis wind turbines. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2022, 11, e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hao, W.; Li, C.; Ding, Q.; Wu, B. A critical study on passive flow control techniques for straight-bladed vertical axis wind turbine. Energy 2018, 165, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouh, F.; Ismaiel, A.; Eleashy, H. Enhancing Wind Turbine Performance Using Flow Control Techniques: A Mini Review. Future Eng. J. 2025, 5. Available online: https://digitalcommons.aaru.edu.jo/fej/vol5/iss1/3 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Akhter, M.Z.; Omar, F.K. Review of Flow-Control Devices for Wind-Turbine Performance Enhancement. Energies 2021, 14, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadumkol, J.; Muangput, B.; Namchanthra, S.; Zin, T.; Phengpom, T.; Chookaew, W.; Suvanjumrat, C.; Promtong, M. CFD modelling of vertical-axis wind turbines using transient dynamic mesh towards lateral vortices capturing and Strouhal number. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalassov, N.; Baizhuma, Z.; Manatbayev, R.; Yershina, A.; Isataev, M.; Kalassova, A.; Seidulla, Z.; Bektibay, B.; Amir, B. Integrated Approach to Aerodynamic Optimization of Darrieus Wind Turbine Based on the Taguchi Method and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, F.; Augustyn, M. Analytical and Computational Fluid Dynamics Methods for Determining the Torque and Power of a Vertical-Axis Wind Turbine with a Carousel Rotor. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlizan, A.; Muzammil, W.K.; Al-Khawlani, N.A. A Review of Computational Fluid Dynamics Techniques and Methodologies in Vertical Axis Wind Turbine Development. CMES—Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 144, 1371–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, L. Design Options to Improve the Dynamic Behavior and the Control of Small H-Darrieus VAWTs. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yao, Q.; Jin, H.; Xu, Y.; Hang, W.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Shi, L.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A novel in-situ sensor calibration method for building thermal systems based on virtual samples and autoencoder. Energy 2024, 297, 131314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xu, P.; Li, Q.; Yin, Z.; Zheng, R.; Wu, J.; Bao, J.; Bai, W.; Qi, H.; Tan, D. Multi-field coupling particle flow dynamic behaviors of the microreactor and ultrasonic control method. Powder Technol. 2025, 454, 120731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, I.O.; Crunteanu, D.E.; Dombrovschi, M.C. Numerical Analysis of Tilted Cavities Placement Effects on the Airfoils in Wind Turbine Systems. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1375, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, I.O.; Crunteanu, D.E.; Dombrovschi, M. Numerical evaluation of airfoils with tilted cavities for vertical axis wind turbines applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3117, 020012. [Google Scholar]

- White, F.M. Flow Past Immersed Bodies. In Fluid Mechanics, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Jiang, H. Investigation of meshing strategies and turbulence models for computational fluid dynamics simulations of vertical axis wind turbines. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2015, 7, 033111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerri, O.; Sakout, A.; Bouhadef, K. Simulations of the Fluid Flow around a Rotating Vertical Axis Wind Turbine. J. Wind Eng. 2007, 31, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeiha, A.; Montazeri, H.; Blocken, B. On the accuracy of turbulence models for CFD simulations of vertical axis wind turbines. Energy 2019, 180, 838–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).