Abstract

Voice phishing has emerged as a critical security threat, exploiting both linguistic manipulation and advances in synthetic speech technologies. Traditional keyword-based approaches often fail to capture contextual patterns or detect forged audio, limiting their effectiveness in real-world scenarios. To address this gap, we propose a multimodal voice phishing detection system that integrates text and audio analysis. The text module employs a KoBERT-based transformer classifier with self-attention interpretation, while the audio module leverages MFCC features and a CNN–BiLSTM classifier to identify synthetic speech. A fusion mechanism combines the outputs of both modalities, with experiments conducted on real-world call transcripts, phishing datasets, and synthetic voice corpora. The results demonstrate that the proposed system consistently achieves high values regarding the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score on validation data while maintaining robust performance in noisy and diverse real-call scenarios. Furthermore, attention-based interpretability enhances trustworthiness by revealing cross-token and discourse-level interaction patterns specific to phishing contexts. These findings highlight the potential of the proposed system as a reliable, explainable, and deployable solution for preventing the financial and social damage caused by voice phishing. Unlike prior studies limited to single-modality or shallow fusion, our work presents a fully integrated text–audio detection pipeline optimized for Korean real-world datasets and robust to noisy, multi-speaker conditions.

1. Introduction

Voice phishing is a prevalent form of social engineering crime in which attackers use telephone calls or voice messages to steal personal and financial information, exploiting victims’ psychological vulnerabilities and trust mechanisms [1]. Prior studies have shown that such criminals employ a variety of manipulation techniques—including caller ID spoofing [2], impersonation of authority figures, imposing time pressure, and using tailored conversation scripts—to hinder victims from making rational decisions [3].

Recent advancements in speech synthesis technologies and large language models (LLMs) have further increased the sophistication of voice phishing schemes. For instance, Figueiredo et al. [4] experimentally demonstrated an AI-based voice phishing bot that combines LLMs with speech synthesis tools to automatically generate and conduct human-like conversations, while Toapanta [5] showed that personalized scams can be executed by imitating the vocabulary and tone of actual targets. These hybrid crimes, which integrate both technical and social engineering elements, have contributed to the steady increase in cases worldwide with their risks amplified by the growing prevalence of contactless financial services.

Existing research on voice phishing detection has primarily focused on three areas: text classification [6,7,8], synthetic speech detection using audio features [9,10], and mobile security frameworks [11]. Recently, LLM-based data augmentation (e.g., using ChatGPT) has been shown to improve text classification performance in low-resource scenarios [6,7]. Following this approach, we expanded original call transcripts into multiple paraphrased variants to increase the diversity of training data. In parallel, research using CNN- and LSTM-based architectures with various acoustic features has been conducted for synthetic speech detection [9]; however, evaluations that incorporate variations in accent and speaking style, as observed in real-world conditions, remain limited [12].

To address these limitations and effectively respond to the evolving tactics of voice phishing, we propose a multimodal voice phishing detection system that integrates text and audio analysis. Text-only systems, while effective in capturing semantic patterns, often misclassify legitimate conversations containing financial or institutional terms, leading to high false-positive rates. Conversely, audio-only systems focusing on acoustic artifacts are highly sensitive to noise, channel variability, and speaker characteristics, resulting in unstable performance. By combining textual semantics with acoustic cues, our multimodal approach mitigates these weaknesses, providing a more robust and reliable framework for detecting complex phishing attacks in real-world environments. The proposed system concurrently analyzes speech and textual information through two complementary detection models: a CNN–LSTM-based synthetic speech detection model and a KoBERT-based text classification model. The outputs of these models are fused using a weighted averaging strategy to produce the final detection decision.

In the text analysis pipeline, the KoBERT architecture with a self-attention mechanism is employed to capture semantic relationships between words within a sentence. Unlike traditional keyword-based approaches—which often misclassify benign sentences as high risk when certain terms (e.g., “account”, “transfer”) appear in non-malicious contexts—the self-attention mechanism evaluates words in their full contextual relationships, enabling a more precise identification of phishing intent.

For data collection, we utilized real-world voice phishing recordings provided by the Financial Supervisory Service, which were transcribed using Whisper STT [13]. Synthetic speech samples were generated using the so-vits-svc-fork model [14] trained on authentic Korean conversational speech from AI Hub [15]. To ensure robust detection in multi-speaker scenarios, a speaker-level analysis module was implemented, extracting speaker embeddings via Resemblyzer [16] and clustering them with K-Means to enable the separate analysis of each speaker’s utterances.

Voice phishing has also become a pressing societal and economic problem worldwide. According to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, reported consumer losses to fraud exceeded 12.5 billion USD in 2024, representing a substantial increase from previous years [17]. Furthermore, impersonation scams targeting older adults have risen dramatically, with reports showing a more than four-fold increase since 2020, and high-loss cases (≥100,000 USD) growing eight-fold during the same period [18]. These statistics highlight the urgent need for robust and adaptable detection systems, particularly as attackers exploit vulnerable populations and rapidly evolving communication technologies.

Although recent efforts have explored text classification and synthetic speech detection, a comprehensive multimodal system remains underexplored. As highlighted in the survey by Triantafyllopoulos et al. [19], the lack of systematic approaches to voice phishing detection underscores the necessity of integrating linguistic and acoustic cues. To address these gaps, this study presents a multimodal system for voice phishing detection via integrated text and speech processing.

2. Related Work

Existing approaches to voice phishing detection have made notable progress, but they also exhibit critical shortcomings in practical scenarios. For example, text-only classifiers such as keyword-based and n-gram models often fail in multi-speaker environments, where fragmented conversational turns dilute semantic context and increase false-positive rates. Similarly, audio-based detection models relying solely on MFCC or spectrogram features have shown reduced robustness against modern neural vocoders (e.g., HiFi-GAN, VITS) and voice conversion systems, which produce speech with highly natural prosody and timbre. These limitations illustrate why a multimodal framework that jointly leverages linguistic and acoustic cues is necessary for achieving robustness in real-world environments.

2.1. Text-Based Voice Phishing Detection

Among studies on voice phishing detection, approaches based on text analysis have been actively explored from various perspectives. Dai et al. [6] proposed AugGPT, which is a data augmentation method that leverages ChatGPT to reconstruct existing sentences into semantically similar yet lexically diverse paraphrases. This technique was shown to effectively improve the accuracy of classification models in few-shot settings. Fang et al. [7] also utilized ChatGPT to generate sentences with compositional generalization, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to process unseen combinations of sentences in tasks such as Open Intent Detection. These studies support the view that LLM-based augmentation is advantageous for learning semantic relationships between sentences.

Moussavou Boussougou et al. [8] proposed a hybrid model that combines FastText embeddings with an attention-based 1D CNN–BiLSTM architecture to simultaneously learn both structural and sequential features of voice phishing sentences. Su et al. [20] systematically analyzed cases where large language models (LLMs) were applied to time-series prediction and context-based anomaly detection, demonstrating that LLM-based text analysis can also be effective for voice phishing detection. Lee et al. [21] demonstrated the feasibility of real-time detection by converting actual voice phishing audio into text using speech-to-text (STT) technology and applying the results to a machine learning-based text classification model.

Sim and Kim [22] achieved GPT-4-level performance in voice phishing detection by combining expert evaluation criteria with Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning in a lightweight Llama3 language model. Sim and Nasution [23] benchmarked the performance and efficiency of phishing URL detection across 21 open-source LLMs using various prompting strategies (zero-shot, few-shot, CoT, etc.), confirming that some models approached GPT-4-level performance. Li et al. [24] analyzed the security vulnerabilities of existing text-based detection methods by generating adversarial phishing transcripts with LLMs to evade detection.

Text-based voice phishing detection research has evolved in various directions, including data augmentation, temporal and contextual analysis, lightweight model optimization, adversarial attack mitigation, and methodological reviews. However, there remains a shortage of studies utilizing large-scale raw data collected directly from real-world voice phishing calls, with most relying on scripted or transcribed datasets, which limits the validation of performance in practical environments.

2.2. Audio-Based Voice Phishing Detection

Research on audio-based voice phishing detection has primarily focused on synthetic speech identification and the development of mobile security systems. Zhang et al. [9] analyzed the accuracy and limitations of synthetic speech detection methods based on acoustic features such as MFCC, CQCC, and spectrograms, utilizing CNN, ResNet, and LSTM architectures. They emphasized the need for neural network architectures capable of capturing high-dimensional temporal information to mitigate vulnerabilities to synthetic speech. Triantafyllopoulos et al. [10] highlighted the necessity of foundation models with broad applicability in audio processing and discussed the potential of multitask architectures to overcome the limitations of task-specific models. Elizalde and Emmanouilidou [25] further demonstrated that robocalls and spam calls can be detected with over 93% accuracy using only acoustic features of voicemail recordings, underscoring that audio cues alone can serve as a strong baseline for detecting suspicious calls.

In the context of social engineering-based voice scams, Ray et al. [12] experimentally investigated how speech characteristics, such as ethnic accents, influence recipients’ trust judgments. From a mobile security perspective, Kim et al. [11] analyzed the behavior of malicious Android-based voice phishing applications and proposed the HearMeOut framework, which blocks attacks such as call redirection, screen overlays, and synthetic speech playback by detecting system API calls. More recently, advanced security systems that integrate synthetic speech detection with user authentication have been proposed. Kang et al. [26] developed the DeepDetection system, which performs speech preprocessing locally on the user’s device to detect synthetic speech and simultaneously authenticate the caller without exposing personal information, achieving an F1-score of 100% in voice phishing prevention.

Despite these advances, existing approaches still face several challenges, including an insufficient consideration of accent and speaking style variations in real-world voice phishing calls, limited handling of multi-speaker environments, and difficulties in adapting to the latest synthetic speech technologies.

2.3. Multimodal Voice Phishing Detection

Although relatively few studies have directly addressed multimodal voice phishing detection, several related works provide important context. Pham et al. [27] demonstrated that combining spectrogram-based features with deep neural models can improve audio deepfake detection, but their work focused primarily on synthetic voice identification without integrating linguistic information. Triantafyllopoulos et al. [19] emphasized the importance of multimodal approaches that leverage both acoustic and textual cues, but existing systems often adopt shallow fusion strategies and have not been evaluated under real-world noisy or multi-speaker conditions. Other multimodal frameworks, such as CLIP-style cross-modal fusion, have shown strong performance in general tasks but remain underexplored in the domain of phishing detection. These shortcomings underscore the necessity of our work, which introduces a fully integrated text–audio detection pipeline optimized for Korean real-world datasets, explicitly addressing the limitations of prior multimodal or single-modal approaches.

2.4. Summary

Existing research on voice phishing has primarily proposed individual detection methods for each modality—such as text classification, audio-based synthetic speech detection, and mobile security frameworks—or focused on improving performance in specific environments. However, many studies have faced limitations in acquiring data that reflect real-world call scenarios, and few have presented a unified system capable of handling multi-speaker situations or adapting to the latest voice phishing techniques. To address these gaps, this study proposes a multimodal voice phishing detection system integrating text and audio analysis, leveraging both real-world phishing cases and synthetic speech to provide a more practical and scalable detection solution.

3. Design and Implementation

The proposed multimodal voice phishing detection system estimates the likelihood of a call being a phishing attempt by jointly analyzing its speech and textual representations. As illustrated in Figure 1, the input audio is first processed through speaker diarization, segmenting the conversation into up to two speakers. Each segment is then independently analyzed in parallel: the transcribed text is processed by a KoBERT-based classifier, while the raw speech signal is evaluated by a CNN–LSTM model. The results are subsequently fused to produce the final phishing risk score.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed multimodal voice phishing detection system. The system applies speaker diarization to separate speakers and then performs parallel analysis using a text-based and an audio-based detection model.

In the text-based detection model, the audio is transcribed using a Speech-to-Text (STT) module, and a KoBERT-based sentence classifier estimates the probability of voice phishing content. This probability is converted into a text-based risk score ranging from 0 to 100.

In the audio-based detection model, Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) features were adopted as the primary audio representation because they capture perceptually meaningful aspects of human speech—such as timbre and spectral envelope—while maintaining computational efficiency. We also examined other acoustic representations, including spectrograms, Constant-Q Cepstral Coefficients (CQCCs), and prosodic features, but MFCCs provided the most stable performance–efficiency balance within our framework. The extracted MFCCs are then fed into a CNN–BiLSTM model to estimate the likelihood of synthetic (deepfake) speech, which is converted into an audio-based risk score.

For each speaker, the final score is calculated as a weighted average of the text- and audio-based risk scores. The overall decision for the call is determined by the highest score among all speakers.

3.1. Data Collection

In this study, we aimed to secure high-quality data that closely resemble real-world scenarios to train the proposed multimodal voice phishing detection system. We first collected 2542 real phishing conversations and 21,950 non-phishing conversations provided by the Financial Supervisory Service. However, the phishing data volume was significantly smaller than the non-phishing data, raising the risk of class imbalance during training.

To mitigate this issue, we applied a ChatGPT-based scenario generation technique. Specifically, we referenced 762 original phishing conversations (approximately 30% of the total) to generate synthetic scenarios that preserved the original intent and context while diversifying vocabulary and sentence structures. To validate the quality of these generated samples, we performed manual verification on a subset of 500 utterances, confirming that they preserved realistic phishing intent without introducing semantic errors. In addition, we conducted a comparative distributional analysis by examining lexical frequency profiles and dialogue length statistics between generated and authentic data, which showed high similarity. These steps ensured that the generated scenarios enriched the dataset without distorting its overall distribution. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that LLM-based augmentation may introduce subtle stylistic biases, and we plan to address this in future work by incorporating cross-corpus validation and multilingual augmentation strategies. This process yielded a total of 3304 phishing utterances. The final dataset consisted of 3304 phishing and 21,950 non-phishing samples, resulting in an approximate class ratio of 8:2. The data were split into training and validation sets at a 9:1 ratio, producing 22,707 samples for training and 2523 for validation.

Due to ChatGPT’s token limitations, each generated scenario was produced as a single turn from the caller (i.e., the phishing actor). The main prompt guidelines used for scenario generation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example prompt instructions for ChatGPT-based scenario generation.

As summarized in Table 2, both sources originate from primarily Korean corpora. While this ensures domain-specific optimization, it also limits generalization across multilingual and cross-regional scenarios.

Table 2.

Dataset sources and their characteristics.

3.2. Speaker Separation and Preprocessing

This study takes into account that real-world calls often involve multiple speakers. Accordingly, the input audio is first segmented at the speaker level using diarization, after which both text- and audio-based analyses are conducted in parallel for each speaker. To achieve this, each audio frame is transformed into a 256-dimensional embedding using the VoiceEncoder of Resemblyzer. The sequence of embeddings is then clustered with K-means to partition speakers, restricting the number of clusters to to reflect the typical one-on-one nature of call center and fraud conversations, as the majority of real-world voice phishing incidents involve a single scammer and a single victim (conference or group calls with more than two participants are outside the scope of this study).

K-means minimizes the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) for each cluster with centroid :

The choice of k is determined jointly by the silhouette score and cluster cohesion. For a sample i, the silhouette value is defined as

where is the mean intra-cluster distance (distance to all other samples in the same cluster), and is the mean nearest-cluster distance (distance to the closest neighboring cluster). If the mean silhouette score is low (indicating unclear separation), or if small clusters fail to meet a minimum sample/length threshold, the segment is treated as single-speaker audio (). (In practice, minimum thresholds on segment duration and count were applied to avoid misclassifying short noise fragments as independent speakers).

In exceptional cases (e.g., embedding generation failure, clustering non-convergence, excessive silence/noise), a fallback strategy is applied, treating the segment as single-speaker audio to ensure robust processing without loss.

To further handle overlapping speech or clustering failures, the system monitors the average silhouette score and intra-cluster variance in real time. If the silhouette score falls below 0.35 or the cluster variance exceeds a predefined threshold, the current segment is adaptively merged into a single-speaker stream using energy-based thresholding. This fallback mechanism effectively prevents false speaker splits and improves diarization stability in overlapping or noisy environments.

The separated speaker segments are saved as individual audio files, which are subsequently transcribed using OpenAI Whisper STT and forwarded to the text processing pipeline.

The transcribed text undergoes only minimal normalization so as not to alter semantic meaning: the removal of redundant spaces or repeated symbols, the exclusion of emojis and non-linguistic marks, and the standardization of numeric and currency expressions (see Section 4 for details). The tokenized sequence, produced after morphological analysis and word-level segmentation, is then passed to a pretrained KoBERT-based classifier to compute the text risk score.

In summary, the procedure consists of the following four stages:

- 1.

- Embedding: generate frame-level embeddings with Resemblyzer VoiceEncoder.

- 2.

- Clustering: apply K-means with , minimizing J in (1).

- 3.

- Model selection: determine k using from (2) and minimum sample/length thresholds; apply single-speaker fallback if conditions fail.

- 4.

- Post-processing: store speaker-specific segments → Whisper STT → text normalization and tokenization.

3.3. KoBERT-Based Text Phishing Detection Model

We selected KoBERT over other pretrained language models due to its advantages in handling Korean text. KoBERT is pretrained on large-scale Korean corpora and employs a tokenizer optimized for Korean morphological structures, allowing it to accurately process compound words, postpositions, and honorific expressions that are prevalent in Korean conversation. In contrast, multilingual models such as mBERT or XLM-R allocate limited representation capacity to Korean and often fragment words into unnatural subword units, leading to degraded performance. These characteristics make KoBERT particularly well suited for phishing detection in Korean dialogues, where subtle lexical and contextual variations are critical to distinguishing fraudulent intent from benign conversations.

This section details the architecture and training procedure of the KoBERT-based text phishing detection model, which leverages a pretrained Korean language model. Each input sentence is tokenized into subword units using the SentencePiece tokenizer with a maximum sequence length of 64 tokens. If the sequence length is shorter than 64, padding tokens are added. The tokenized sequence is then transformed into three tensors—input IDs, token type IDs, and attention masks—that serve as model inputs. Unlike approaches requiring morphological analysis, the KoBERT model directly processes raw sentences through a Transformer-based encoder to capture contextual dependencies.

3.3.1. Model Architecture

KoBERT adopts a Transformer architecture in which the output vector of the special [CLS] token is used to represent the overall meaning of the sentence. This vector is passed through a fully connected layer to produce classification logits, which are then converted into probabilities via the Softmax function. The probability of the phishing class, , is calculated as in Equation (3):

where denotes the logit for the normal conversation class, and denotes the logit for the phishing class.

The self-attention operation in KoBERT is defined as follows, using the Query, Key, and Value matrices :

Here, represents the dimension of the Key vectors, and the Softmax function normalizes attention scores into probabilities, thereby capturing semantic associations between words. From the final encoder layer, the output vector corresponding to the [CLS] token, , is used to summarize the meaning of the entire sentence.

This vector is transformed into classification logits using a multilayer perceptron (MLP):

The phishing probability is then calculated using the Softmax function and scaled to define the text-based risk score :

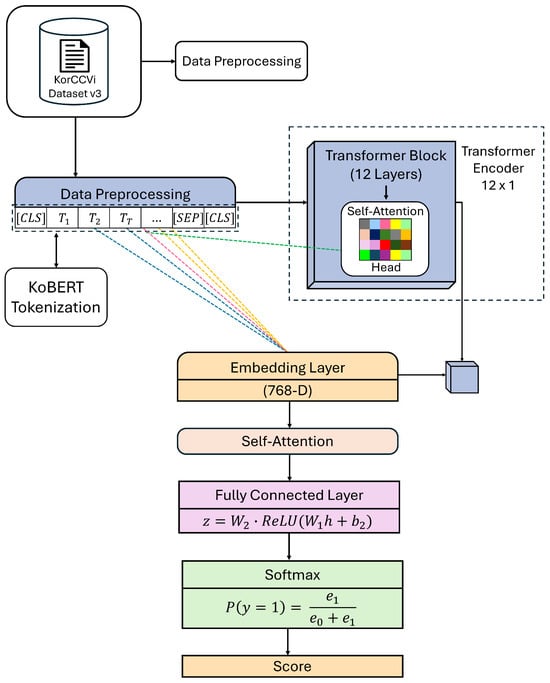

Figure 2 illustrates the overall architecture and data flow of the KoBERT-based text classification model implemented in this study. Sentences from the KorCCVi Dataset v3 are preprocessed and tokenized with SentencePiece into at most 64 tokens, which are each mapped to a 768-dimensional embedding vector. These embeddings are processed through a 12-layer Transformer encoder, where the self-attention mechanism learns contextual relationships between tokens. Finally, the output vector of the [CLS] token is passed through a fully connected layer and Softmax function to yield the phishing probability, which is used as the text risk score.

Figure 2.

Architecture and data flow of the KoBERT-based text classification model used in this study.

The adoption of a self-attention mechanism is motivated by its ability to capture semantic dependencies within sentences, which is in contrast to keyword-based approaches that rely on word frequency and may fail in manipulated contexts. Unlike RNNs, which suffer from information decay in long sequences, or CNNs, which struggle with long-range dependencies, the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism can effectively model complex sentence structures, making it well suited for phishing detection tasks.

3.3.2. Training Procedure

The KoBERT-based text classification model was trained using the standard cross-entropy loss as the objective function with AdamW adopted as the optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to , and a linear decay scheduler was applied to ensure stable convergence. Training was conducted for a total of 10 epochs with a batch size of 32.

As shown in Table 3, validation accuracy reached 99.96% at epoch 3, and the validation F1 peaked at 99.68% (epoch 3). Subsequent epochs exhibited small, non-monotonic fluctuations (e.g., 95.41% at epoch 4 and 99.36% at epoch 5) while maintaining overall high performance, indicating rapid convergence under our preprocessing and training setup.

Table 3.

Training results of the KoBERT-based text classification model.

Each utterance was tokenized and padded/truncated to 64 tokens. Tokens were encoded by KoBERT (12-layer Transformer, 768-dim), and the [CLS] representation was fed into a dropout-regularized classification head (p = 0.4). A softmax layer was applied only at inference. Attention masks ensured that padded tokens did not influence self-attention, and attention maps were inspected only for analysis (not used as classifier inputs).

The cross-entropy loss is defined as

where N is the batch size, is the one-hot ground truth label of sample i, and is the predicted probability of class c obtained from the Softmax function.

Considering the class imbalance, a weighted version of the loss function was employed:

where denotes the weight assigned to class c.

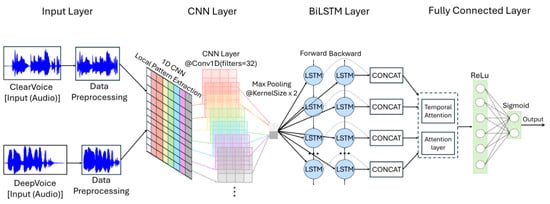

3.4. Synthetic Speech Detection Model

To determine whether a given utterance is genuine or artificially generated, we designed a hybrid classification model that integrates convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM). As shown in Figure 3, the model combines acoustic feature extraction, temporal sequence modeling, and an attention mechanism to capture both local and contextual patterns associated with synthetic speech.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the CNN-BiLSTM based synthetic speech detection model.

Feature Extraction and Architecture

Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs) were extracted from each utterance using a 25 ms window size and a 10 ms frame shift. MFCCs provide a compact representation of spectral and timbre characteristics, reflecting perceptual properties of human hearing.

The MFCC sequences were fed into a one-dimensional CNN (Conv1D) layer, which effectively captures short-term variations such as noise, distortion, and pitch anomalies. The convolutional operation is defined as

Subsequently, the output was processed through a BiLSTM layer, which incorporates both past and future temporal dependencies:

To emphasize abnormal patterns more likely to appear in synthetic speech, a temporal attention mechanism was applied:

where denotes the attention weight at time step t, and W, , and b are trainable parameters.

The final representation was passed through a fully connected layer with ReLU activation and a sigmoid output, which produces the probability of synthetic speech. This probability is scaled to 0–100 and defined as the Voice Score.

3.4.1. Dataset Preparation and Quality Verification

Genuine Korean speech data from AI Hub were used as real samples, while synthetic speech was generated using the so-vits-svc-fork model with the same dataset. Approximately 18,000 samples were collected and split into training and validation sets with an 8:2 ratio.

Prior to training, dataset quality was verified by computing the cosine similarity between MFCC mean vectors of paired real and synthetic utterances (1691 pairs). The average similarity score reached 0.974, confirming that synthetic data closely resembled real speech in terms of spectral and timbre characteristics (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality verification of synthetic speech data.

3.4.2. Training Procedure and Results

The model was trained using binary cross-entropy loss with the Adam optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to with a batch size of 32 for 5 epochs. Dropout (0.3) was applied to reduce overfitting, and input sequences were padded to a fixed number of MFCC frames.

As detailed in Table 5, the CNN-BiLSTM model exhibited highly effective and rapid convergence during its five-epoch training. The validation accuracy consistently achieved remarkable performance, reaching 99.83% as early as the first epoch. This performance further improved, peaking at an impressive 0.9992 in epoch 3. Throughout the remaining epochs (up to epoch 5), the validation accuracy remained consistently high and stable, demonstrating that the model effectively learned to distinguish between genuine and synthetic speech under the specified training configuration without significant degradation. This rapid and stable convergence confirms the robustness of the model and the effectiveness of the chosen features and architecture for synthetic speech detection.

Table 5.

Training results of the CNN-BiLSTM synthetic speech classifier.

3.4.3. Integration into Risk Scoring

The model output represents the probability of synthetic speech, which is expressed as the (0–100). In the multimodal phishing detection system, this score is combined with the text-based score () via a weighted average:

If the final score exceeds 70, the call is classified as phishing; otherwise, it is considered benign.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

The text dataset was compiled from two primary sources. First, real-world voice phishing speech cases released by the Financial Supervisory Service were transcribed into text using OpenAI Whisper. Second, to capture general conversational patterns, we utilized the Korean Multi-Session Dialogue Corpus provided by AI Hub. In total, approximately 90% of the data (22,707 samples) was allocated for training, while the remaining 10% (2523 samples) was reserved for validation.

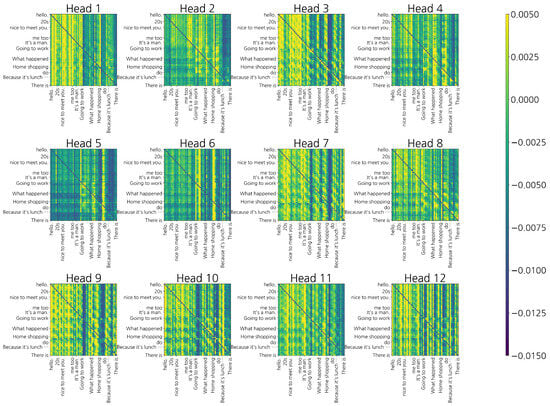

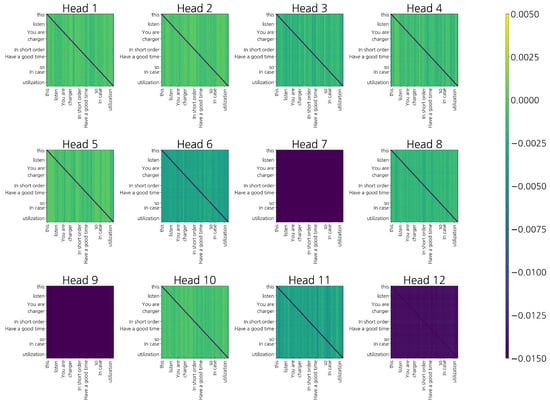

The model input was limited to a maximum of 64 tokens with excess length truncated at the head. However, when visualizing attention maps, displaying all 64 tokens resulted in label overlap and reduced readability due to dense cells. To ensure clarity, only the most relevant subsections of tokens were displayed: Figure 4 shows tokens, and Figure 5 shows tokens. In addition, special tokens ([CLS], [SEP], [PAD]) and self-attention along the main diagonal were removed. As a result, the number of tokens in the figures appears smaller than the original input length; however, this reduction was performed solely for visualization purposes and does not affect training or inference.

Figure 4.

Last-layer 12 attention heads (excess, no diagonal/special) for a normal conversation sample. Tokens on both axes; brighter cells indicate stronger cross-token interactions after removing the main diagonal and special tokens.

Figure 5.

Last-layer 12 attention heads (excess, no diagonal/special) for a phishing sample. Repeated vertical bands emerge around finance/verification tokens (e.g., loan, rate, fund, confirm, condition, product).

Figure 4 illustrates the last-layer attention heads for a normal conversation sample. Brighter cells indicate stronger cross-token interactions after excluding special tokens and self-attention.

The text classifier combined a KoBERT encoder with a shallow classification head while enabling attention output, which is defined as

Attention interpretation was performed as follows. First, special tokens and self-attention were removed, leaving only cross-token interactions. Each row was normalized into a probability distribution, and excess attention relative to a uniform distribution () was calculated as

where denotes the row-normalized attention matrix and T is the effective token length.

Sentence-level influence was computed using the attention rollout method proposed by Chefer et al. [28], in which layer-wise mean attention across heads is combined through cumulative multiplication:

Token importance relative to the [CLS] embedding was visualized using the first row of R. Furthermore, to quantify the contribution of individual heads, we computed four indicators: (i) entropy to measure concentration, (ii) semantic affinity based on finance/discourse lexicons, (iii) head diversity using the Jensen–Shannon distance, and (iv) head-masking contribution .

For voice classification, approximately 18 K paired samples were constructed from genuine speaker recordings in AI Hub, and synthetic voices were generated using so-vits-svc-fork. MFCC features were extracted with a 25 ms window and 10 ms hop, and a 1D-CNN+BiLSTM binary classifier was trained with an 8:2 split, converging within 10 epochs. To reflect multi-speaker conditions, Resemblyzer embeddings and K-Means clustering (maximum ) were used to separate speakers. The final call-level score was conservatively aggregated as the maximum risk score among speakers:

Finally, multimodal fusion was performed by normalizing text and voice scores to a 0–100 range and combining them via weighted sum:

Thresholds for warning or confirmation (e.g., 70/90) were used exclusively for user notification and did not affect the calculation of quantitative evaluation metrics. All experiments were conducted under consistent settings to ensure reproducibility.

4.2. Qualitative Analysis of Attention Patterns (12-Head Visualization)

Figure 4 and Figure 5 compare the last-layer attention heads between normal conversations and phishing utterances. The main diagonal and special tokens ([CLS], [SEP], [PAD]) were removed, and each row was normalized into a probability distribution. Only the excess attention relative to a uniform distribution was visualized.

In normal conversations (Figure 4), a distributed pattern reflecting discourse cohesion was dominant. Local binding emerged around honorifics (e.g., “Hello”, “Nice to meet you”), address terms (e.g., “Mother”, “Teacher”), and discourse connectives (e.g., “and”, “so”, “but”). For example, in utterances such as “Did you enjoy your lunch? I usually like to eat stew.”, sequential topical continuity (food, hobbies, daily life) was evident with bright spikes appearing within noun phrases (“stew → like to eat”) and near discourse markers.

Among the 12 heads, some linked honorific or address tokens with sentence-initial context, while others emphasized closure signals at sentence boundaries (e.g., period, final endings). This functional differentiation across heads resulted in relatively high entropy (average 0.78) and elevated Jensen–Shannon-based head diversity (0.62), which were both significantly higher than in phishing dialogues (0.41). Such dispersion mitigates false positives by distributing attention across multiple contextual cues rather than overfocusing on isolated financial or directive terms.

In contrast, phishing utterances (Figure 5) exhibited repeated vertical bands concentrated on financial tokens (“loan”, “interest rate”, “fund”, “account”), procedural terms (“repayment”, “policy”, “condition”), directives (“send”, “transfer”, “verify”), and immediacy cues (“now”, “immediately”). For example, in the sentence “If you repay a high-interest loan today with the government support fund, your credit score will increase,” financial terms such as “loan” or “product” became tightly coupled with procedural vocabulary (“repayment”, “policy”), while legitimization terms (“credit score”) intersected with directive verbs (“receive”, “submit”) and identifiers (“account”, “amount”). Immediacy expressions (“today”, “now”) further reinforced this alignment.

Multiple heads converged on the same rows and columns, producing clear columnar patterns. Consequently, head entropy was lower (mean 0.54), reflecting a stronger focus on specific semantic roles, while the consensus index (0.81) was markedly higher than in normal dialogues (0.62), indicating that heads collectively tracked the persuasion frame of financial transfer–immediacy–procedural legitimization. Such structures were not triggered by isolated keywords but reliably emerged when the discourse flow completed the sequence of request → directive → legitimization.

In short utterances, normal conversations displayed weakly distributed cohesion, whereas phishing samples showed concentrated coupling between directive verbs and identifiers (account, amount), yielding high focus despite brevity. This demonstrates that the model stably captured cross-role coupling structures even in short, colloquial phishing utterances.

For each sample, we further computed indices of focus, consensus, financial–action coupling, head masking contribution (), and head diversity. Head diversity was defined as the mean Jensen–Shannon distance across all head pairs in the final layer. Higher values indicate that heads attend to diverse token relations, while lower values reflect stronger inter-head consensus. Experimental results showed that normal conversations exhibited higher diversity (0.62) compared to phishing ones (0.41), suggesting that heads distributed attention across contextual and discourse-organizing functions in normal dialogues while converging on finance–directive–procedure semantics in phishing. These indices provided a systematic interpretation of how attention distributions—through concentration, alignment, and cross-role coupling—contributed to the final classification decision.

4.3. Quantitative Analysis of Attention Concentration (Entropy–Gini Metrics)

To complement the qualitative visualization, we computed two quantitative indices—normalized Shannon entropy (H) and the Gini coefficient (G)—to measure attention concentration in the fine-tuned KoBERT model. For each input utterance, the attention weights of the final transformer layer were extracted from the [CLS] token and normalized to form a probability distribution.

The normalized Shannon entropy H is defined as

where denotes the normalized attention weight for token i and n is the number of tokens. Lower entropy indicates that attention is concentrated on fewer tokens, whereas higher values imply a more uniformly distributed focus.

The Gini coefficient G, originally used to quantify inequality in economics, measures how unevenly attention is distributed:

Higher G values correspond to greater inequality (i.e., stronger attention focus on specific tokens).

Table 6 presents the averaged results across the test set. Normal conversations exhibited higher entropy (0.992) and lower Gini (0.149), indicating that attention was evenly distributed across discourse-related tokens. In contrast, phishing utterances showed lower entropy (0.807) and higher Gini (0.366), confirming that attention was more narrowly focused on risk-related terms such as “loan,” “account,” and “credit.”

Table 6.

Average entropy and Gini coefficient of attention distributions.

4.4. Quantitative Comparison Between Baseline and Proposed Models

On the same validation set (250 sentences, balanced between normal and phishing), the proposed model substantially outperformed the baseline in both precision and F1-score (Table 7). This improvement is attributed to the integration of LLM-based semantic diversification and self-attention-friendly preprocessing, which enabled the stable detection of discourse patterns involving request–action–procedure–urgency even in short or noisy utterances.

Table 7.

Performance comparison on the validation set (250 sentences).

Evaluation criteria and procedure: For each input sentence, the models output a continuous probability score ranging between 0 and 1. To convert this into a binary classification (normal vs. phishing), we determined an optimal threshold that maximized the F1-score on a held-out portion of the training set. This threshold was then applied unchanged to validation and test sets to avoid data leakage. Evaluation metrics included precision, recall, and F1-score, which were each computed according to standard definitions.

Error analysis: False positives (FPs) and false negatives (FNs) from the validation set were categorized using both qualitative (case inspection) and quantitative (frequency analysis) methods. The main error types were as follows:

(1) Colloquial variations: When utterances contained repetitions, ellipses, or fillers (e.g., “uh”, “well”), the baseline model often failed to interpret context, while the proposed model preserved meaning via preprocessing and attention-based contextualization.

(2) Paraphrasing: Even when phishing dialogues intentionally avoided key terms and instead used semantically similar expressions, the proposed model captured the composite directive–procedure–urgency pattern and maintained detection performance.

(3) Meta-speech: In normal dialogues quoting scam news or warnings, the baseline tended to produce FPs, whereas the proposed model leveraged the overall negative framing of the utterance to suppress such errors.

Performance across length and noise levels: We further analyzed performance by partitioning utterances into buckets based on subword length and speech-to-text (STT) error rate. The proposed model achieved the largest performance gains in the segment of short utterances with high STT noise, demonstrating its ability to capture semantic interaction patterns beyond reliance on individual keywords regardless of utterance length or recognition noise.

Reliability and explainability: To evaluate the calibration of output probabilities, we measured the Brier score and expected calibration error (ECE). Compared with the baseline, the proposed model exhibited reduced over- or under-confidence relative to the ground-truth distribution, making it easier to policy-tune the FP/FN balance through threshold adjustment. Moreover, attention-based token importance visualization provided an explainable alert capability, allowing practitioners to interpret and justify warnings in operational environments.

Table 7 presents the validation results with 250 sentences. The baseline model exhibited high recall (1.0) by over-relying on surface-level cues such as financial or procedural keywords (e.g., institution names, verification requests, transaction instructions). However, this approach led to frequent false positives when such terms appeared in legitimate conversations, resulting in very low precision. In contrast, the proposed model achieved a more balanced performance, maintaining high precision (0.945) while also capturing contextual discourse patterns such as the request–action–procedure–urgency flow. Although recall slightly decreased (0.832), the model substantially reduced false alarms, leading to an improved reliability of alerts and mitigating user fatigue in real-world deployment.

Table 8 presents illustrative examples of normal and phishing utterances from the dataset. Excerpts are shown with partial omission (…) for brevity, and each sample is labeled (0 = normal, 1 = phishing). These examples highlight the dataset’s linguistic characteristics and provide intuitive insight into the types of patterns the model has learned.

Table 8.

Example utterances from the dataset (normal and phishing).

Table 9 further breaks down the phishing subset of the evaluation dataset. While the majority of samples involve prosecutor, police, or public institution impersonation, 25 cases (20% of the phishing data) represent family impersonation fraud. This demonstrates that family-voice scam scenarios are already included in our dataset. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that the current scope remains limited, and future work will extend the dataset to cover additional fraud types such as refund scams, tax-related fraud, and messenger-based impersonation, thereby improving robustness and practical applicability.

Table 9.

Composition of phishing cases in the evaluation dataset (total = 125).

4.5. Comparison with Multimodal Baseline Fusion Models

We evaluated three multimodal baseline fusion strategies—early fusion, CLIP-style projection fusion, and late fusion—using the same dataset and experimental configuration as the proposed system. As summarized in Table 10, all fusion approaches outperformed unimodal models (KoBERT text-only and CNN–BiLSTM voice-only), demonstrating the benefits of multimodal integration. However, the proposed weighted fusion (8:2) achieved the best overall balance, reaching an F1-score of 0.994, confirming that adaptively combining textual semantics with acoustic cues yields the most reliable performance under real-world call conditions.

Table 10.

Performance comparison across different multimodal fusion strategies.

The proposed weighted fusion model not only achieved the highest F1-score but also maintained strong precision and recall, illustrating that the system can balance linguistic and acoustic information effectively. Unlike traditional early or late fusion methods that rely on simple feature concatenation or posterior averaging, our model leverages adaptive weighting guided by validation performance, ensuring consistent and robust results across different audio conditions.

4.6. Multimodal Fusion Weight Experiments (VOICE + LLM)

We evaluated text-only, voice-only, and three fusion ratios () on a balanced set of 150 utterances (75 normal, 75 phishing). As shown in Table 11, the voice-only model was highly sensitive to channel characteristics, background noise, and speaking style, producing 41 false positives on normal utterances. In contrast, the text-only (LLM) and all three fusion ratios (7:3, 8:2, 9:1) each yielded nine false positives.

Table 11.

False positives on a balanced evaluation set (75 normal, 75 phishing).

Table 12 illustrates five aligned cases mixing normal and phishing utterances. The voice-only model frequently misclassified benign utterances such as abnormal data usage alerts (Cases 2 and 4) or insurance-related notices (Case 5) as phishing, whereas the LLM and 8:2 fusion generally followed the ground truth more accurately. These observations confirm that voice-only classification is strongly influenced by speaker variation and channel artifacts, and that multimodal fusion with text input is essential for robust performance in real-world environments.

Table 12.

Sample predictions on five aligned cases (the same five are reused in Table 13).

Although the FP counts were identical among these, we selected the 8:2 fusion ratio as the final configuration because it provided the most stable outputs on borderline/disagreement cases (Table 13) while maintaining balance between modalities. This choice was guided by validation set experiments in which we compared three different weighting schemes (7:3, 8:2, 9:1). The 8:2 ratio yielded the most consistent performance under noisy and ambiguous conditions. We note, however, that this weighting remains fixed, and future work will explore adaptive strategies that dynamically adjust the contribution of each modality according to channel conditions, noise levels, or STT confidence.

Table 13.

Multimodal fusion outputs on the same five cases (0–100 scale; decision threshold = 70).

As shown in Table 13, the 8:2 fusion ratio produced stable scores near the decision boundary across multiple disagreement cases. In contrast, the LLM-only and voice-only settings fluctuated heavily: LLM sometimes dropped far below threshold (e.g., 0.01% in Case 2), while the voice-only model often overshot (e.g., 90.40% in Case 1) or hovered near threshold unreliably (e.g., 70.31% in Case 2). These results confirm that multimodal fusion mitigates instability by anchoring decisions to textual cues, thereby providing more consistent classifications in noisy and speaker-diverse real-world scenarios.

4.7. Error Analysis by Fraud Type

To gain deeper insight into the model’s behavioral tendencies, we conducted a detailed false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) analysis categorized by phishing type. Among the 150 evaluation utterances (75 normal, 75 phishing), a total of 9 FPs and 21 FNs were observed under the selected 8:2 fusion configuration.

Interestingly, all FP cases belonged to the family impersonation category, indicating that the model tends to overreact to financial expressions—such as “account,” “transfer,” and “authentication code”—that frequently appear even in benign family conversations. This suggests that while the model effectively captures financial and procedural dependencies, it sometimes misclassifies ordinary family dialogues as phishing when everyday communication includes finance-related terms. Such cases highlight the model’s sensitivity to lexical risk cues regardless of interpersonal context, reflecting partial overfitting to financial semantics.

In contrast, most FN cases were concentrated in family impersonation and several public-institution impersonation utterances. The family-type FNs were characterized by emotionally charged or colloquial expressions (e.g., “I’m at the hospital,” “Please send it quickly,” “I’m sorry”) that lacked explicit financial triggers despite conveying urgency. In these cases, the model appeared to underreact to affective tones, interpreting them as benign family requests rather than fraudulent instructions. For public-institution-type FNs, many samples contained grammatically irregular or corrupted sentences, causing the model to misinterpret procedural intent and lower its confidence in phishing classification.

Overall, these findings indicate that the proposed system performs robustly on structured, institutional scams but remains relatively vulnerable to informal or emotionally driven fraud patterns. These results suggest that incorporating emotion-aware embeddings and conversational context modeling could further enhance the detection of such relational and affective phishing scenarios.

4.8. Computational Cost and Resource Usage

Table 14 summarizes the computational cost across three representative audio lengths. All experiments were executed on a desktop equipped with an Intel i9-9900K CPU and an RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB memory), although the pipeline itself operated entirely on CPU without GPU acceleration. On average, analyzing a 20–170 s audio segment required 32.4 s of latency (RTF ≈ 0.40×) with about 245 MB of CPU memory. These results demonstrate feasibility on high-end desktop hardware while also highlighting the need for further lightweight optimization for deployment on mobile or embedded platforms.

Table 14.

Computational cost measured across audio lengths.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study proposed a multimodal voice phishing detection system that jointly analyzes text and speech to capture fraudulent patterns in real-world call environments. The system integrates a KoBERT-based self-attention text classifier with a CNN–LSTM synthetic speech detector using MFCC features, while employing Resemblyzer–KMeans for speaker diarization and OpenAI Whisper for speech-to-text conversion, enabling automated preprocessing and analysis.

In evaluation, the proposed system demonstrated consistently strong performance, achieving near-perfect precision and F1-score on a balanced validation set and maintaining stable results across multiple fusion configurations on real-call data. Notably, an 8:2 text-to-speech weighting provided the best balance between robustness and reliability, indicating that combining textual signals with audio cues mitigates the sensitivity of voice-only models to channel conditions and environmental variability.

Nevertheless, the system has certain limitations, including reliance on fixed fusion weights, evaluation restricted to Korean datasets, and the absence of multimodal baseline comparisons. In addition, future extensions may explore adaptive fusion mechanisms that dynamically adjust modality weights based on contextual factors such as background noise, speech clarity, and STT confidence to enhance robustness in real-world environments. The following paragraphs elaborate these limitations in more detail and outline directions for future work.

Another limitation is that we did not conduct a detailed ablation study to assess the contribution of each system component. The LLM-based (KoBERT with self-attention) and voice-only (CNN–LSTM) modules exhibited different sensitivities across cases with the fusion approach producing more stable and consistent results overall. To further improve robustness under noisy or error-prone conditions, an adaptive fusion mechanism that accounts for speech noise and STT errors would be beneficial.

This study is based on datasets provided by the Korean Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) and AI Hub, which makes it specifically optimized for Korean language and speaking patterns. As a result, the current findings cannot be directly generalized to multi-regional or multilingual scenarios. In future work, we plan to extend the dataset by incorporating international voice phishing corpora and multilingual speech data in order to evaluate cross-lingual performance and the system’s sensitivity to non-Korean accents.

Specifically, pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation will be applied to reduce model complexity and enable deployment on mobile and embedded platforms without sacrificing accuracy. We also plan to expand the dataset to cover a broader range of fraud scenarios, including family impersonation, refund scams, messenger-based fraud, and tax-related scams. Each of these attack types involves distinct linguistic and acoustic characteristics, and their inclusion will allow us to design specialized modules or adaptive fusion strategies tailored to different scam categories. These detailed pathways will guide practical extensions of our system in both performance and applicability.

Overall, the proposed multimodal framework establishes a practical foundation for reliable and explainable voice phishing detection, providing valuable insights for future research and real-world deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and C.K.; methodology, J.K.; software, J.K.; validation, S.G. and Y.K.; formal analysis, J.K.; investigation, S.G. and Y.K.; resources, C.K.; data curation, S.G. and Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.G., Y.K., S.L. and C.K.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, S.L. and C.K.; project administration, S.L. and C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Culture, Sports and Tourism R&D Program through the Korea Creative Content Agency grant funded by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in 2025 (No. RS-2024-00442837).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in GitHub (https://github.com/newkimjiwon/KoBERT_dataset_v3.0.csv, accessed on 1 September 2025). The repository includes datasets derived from the Financial Supervisory Service (https://www.fss.or.kr/, accessed on 3 May 2025) and AI Hub (https://www.aihub.or.kr/, accessed on 3 May 2025) as well as the augmented data generated by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saini, U. Voice Phishing Attacks. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2020, 7, 4656–4658. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, P.; Ahamad, M.; Kumaraguru, P. Abusing phone numbers and cross-application features for crafting targeted attacks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.07330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, S.; Chandre, P.; Pathan, S.; Mande, U.; Nimbalkar, M.; Mahalle, P. Defending against vishing attacks: A comprehensive review for prevention and mitigation techniques. In Cyber Security and Digital Forensics, Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Developments in Cyber Security, Greater Noida, India, 16–17 June 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 411–422. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, J.; Carvalho, A.; Castro, D.; Gonçalves, D.; Santos, N. On the feasibility of fully ai-automated vishing attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.13793. [Google Scholar]

- Toapanta, F.; Rivadeneira, B.; Tipantuña, C.; Guamán, D. AI-Driven vishing attacks: A practical approach. Eng. Proc. 2024, 77, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.; Liu, Z.; Liao, W.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Xu, S.; Zeng, F.; Liu, W.; et al. Auggpt: Leveraging chatgpt for text data augmentation. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2025, 11, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Li, X.; Thomas, S.W.; Zhu, X. Chatgpt as data augmentation for compositional generalization: A case study in open intent detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.13517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavou Boussougou, M.K.; Park, D.J. Attention-based 1D CNN-BiLSTM hybrid model enhanced with fasttext word embedding for Korean voice phishing detection. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cui, H.; Nguyen, V.; Whitty, M. Audio deepfake detection: What has been achieved and what lies ahead. Sensors 2025, 25, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllopoulos, A.; Tsangko, I.; Gebhard, A.; Mesaros, A.; Virtanen, T.; Schuller, B. Computer audition: From task-specific machine learning to foundation models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.15672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Wi, S.; Kim, Y.; Son, S. HearMeOut: Detecting voice phishing activities in Android. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, Portland, OR, USA, 27 June–1 July 2022; pp. 422–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, A.; Saha, S.; Chakrabarty, K.; Collins, L.; Lafata, K.; Emami-Naeini, P. Exploring the Impact of Ethnicity on Susceptibility to Voice Phishing. In Proceedings of the USENIX Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS), Anaheim, CA, USA, 7–8 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- voicepaw. so-vits-svc-fork: A Realtime Voice Conversion System Based on SoftVC VITS. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/voicepaw/so-vits-svc-fork (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- National Information Society Agency (NIA). Korean Conversational Speech Corpus. 2020. Available online: https://www.aihub.or.kr (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- resemble-ai. Resemblyzer: Voice Embedding Toolkit for Speaker Similarity and Diarization. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/resemble-ai/Resemblyzer (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Federal Trade Commission. New FTC Data Show a Big Jump in Reported Losses to Fraud. 2025. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/03/new-ftc-data-show-big-jump-reported-losses-fraud-125-billion-2024 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Federal Trade Commission. FTC Data Show a More Than Four-Fold Increase in Reports of Impersonation Scammers. 2025. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2025/08/ftc-data-show-more-four-fold-increase-reports-impersonation-scammers-stealing-tens-even-hundreds (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Triantafyllopoulos, A.; Spiesberger, A.A.; Tsangko, I.; Jing, X.; Distler, V.; Dietz, F.; Alt, F.; Schuller, B.W. Vishing: Detecting social engineering in spoken communication—A first survey & urgent roadmap to address an emerging societal challenge. Comput. Speech Lang. 2025, 94, 101802. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Jiang, C.; Jin, X.; Qiao, Y.; Xiao, T.; Ma, H.; Wei, R.; Jing, Z.; Xu, J.; Lin, J. Large language models for forecasting and anomaly detection: A systematic literature review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, E. Real-time Korean voice phishing detection based on machine learning approaches. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2023, 14, 8173–8184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.Y.; Kim, S.H. Detecting Voice Phishing with Precision: Fine-Tuning Small Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, A.H.; Monika, W.; Onan, A.; Murakami, Y. Benchmarking 21 Open-Source Large Language Models for Phishing Link Detection with Prompt Engineering. Information 2025, 16, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Manickam, S.; Chong, Y.w.; Karuppayah, S. Talking Like a Phisher: LLM-Based Attacks on Voice Phishing Classifiers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.16291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, B.; Emmanouilidou, D. Detection of robocall and spam calls using acoustic features of incoming voicemails. Proc. Mtgs. Acoust. 2021, 45, 060004. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, W.; Lim, S.; Kim, H.; Seo, H. Deepdetection: Privacy-enhanced deep voice detection and user authentication for preventing voice phishing. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Lam, P.; Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, H.; Schindler, A. Deepfake audio detection using spectrogram-based feature and ensemble of deep learning models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 5th International Symposium on the Internet of Sounds (IS2), Erlangen, Germany, 30 September–2 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chefer, H.; Gur, S.; Wolf, L. Transformer interpretability beyond attention visualization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 782–791. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).