Abstract

Bypass graft is widely used, especially in cardiovascular diseases, to detour clogged blood vessels, alleviating and correcting the manifestation of the symptoms of damaged blood vessels. Bypass grafting is also used in hemodialysis treatment, specifically an arteriovenous bypass graft, considering the repeated withdrawal of blood, for the dialysis machine to filter the blood and return it to the body to circulate. Nonetheless, bypass grafts are susceptible to failure due to the abnormal hemodynamic performance of the blood flowing to the graft, leading to complications such as thrombosis, intimal hyperplasia, and atherosclerosis. Multiple bypass graft designs are continuously developed to optimize the desirable hemodynamics of the blood, which is essential to avoid complications. This study examines helical arteriovenous bypass graft (AVG) hemodynamic performance using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to identify enhanced blood flow characteristics. The analysis concentrated on area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS), helicity, pressure drop, time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT) from twenty-seven graft models changing anastomosis angles, helical diameters, and helical pitches. Model 25-13-30 (25-degree anastomosis angle, 13 mm helical diameter, 30 mm helical pitch) demonstrated the most favorable overall hemodynamic performance based on the variables considered. The results indicate that integrating helical shape into bypass grafts improves hemodynamic performance, reduces intimal hyperplasia risk, and may prolong graft durability. These findings provide valuable insights and suggestions for enhancing AVG designs to support patient outcomes.

1. Introduction

Bypass graft demand is continuously rising as a result of the growing prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). It is reported in the United States that ischemic heart disease affects approximately 20.5 million Americans, and this accounts for over 371,000 deaths in 2022 [1]. One way to address this global burden is by utilizing a bypass graft, creating an alternative pathway for blood flow, allowing circulation to occur without setbacks from bypassed, blocked, or damaged sections of arteries or veins. This ensures a stable blood supply, and multiple efforts, trials, and designs are developed to optimize graft performance while minimizing complications caused by the hemodynamic characteristics of the blood flow on the designed graft. Bypassing blood around clogged vessels and bypass grafts helps alleviate symptoms and prevent serious cardiac events by detouring blood around clogged vessels. Bypass graft material depends on the clinical application, ranging from autologous veins and arteries to synthetic materials such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and Dacron. In that context, coronary surgeries utilize autologous grafts, which are generally preferred to synthetic grafts commonly used in peripheral bypass procedures [2]. Despite this method in addressing blood flow problems, regardless of the material used, both are susceptible to failure, often leading to complications such as occlusion from thrombosis, intimal hyperplasia, and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, which result from hemodynamic factors [3].

Blood vessels naturally adapt to their hemodynamic environment to maintain homeostasis, essential for normal function. However, introducing foreign materials such as bypass grafts, used to treat or manage vascular diseases, can disrupt this balance. These disruptions often arise from new hemodynamic effects of the graft. For example, hemodialysis utilizes an arteriovenous graft (AVG) as a vascular access point, allowing repeated withdrawal of blood, filtration using a dialysis machine, and returning the blood to the human body. Approximately 80% of AVG failures are linked to intimal hyperplasia, while the remainder is caused by infection [4]. Intimal hyperplasia is the abnormal thickening of the vessel’s inner layer, driven by the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells and the deposition of a proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix between the endothelium and the internal elastic lamina. The remodeling typically begins at the surgical anastomosis site; the sudden change in vessel geometry and the differences in flexibility between the native vessel and the graft produce a disturbed blood flow. As a result, the vessel wall thickens over time and the lumen narrows, reducing the blood flow and raising the risk of thrombosis [5]. Hemodynamic disturbances, especially regions of low wall shear stress (WSS) and a high oscillatory shear index (OSI), promote endothelial dysfunction, inflammatory cell recruitment, and neointimal growth [6,7]. Conversely, the release of matrix-degrading enzymes is associated with abnormally high WSS, often resulting from stenosis-induced flow acceleration or changes to sharp vessel geometry, hence the damage to the endothelium [8].

Several research efforts have focused on improving the hemodynamic performance of vascular grafts to prevent the development of intimal hyperplasia, which is a significant cause of graft failure. One promising approach involves inducing swirling or spiral blood flow within prosthetic grafts, which has been hypothesized to enhance clinical outcomes in patients undergoing bypass grafting [9]. The arterial systems have a natural feature of spiral flow and play a role in stabilizing shear stresses, minimizing flow disturbances, and promoting vessel wall health [10,11]. Researchers aim to optimize local hemodynamics and prolong graft patency by replicating this physiological flow pattern in graft designs. In a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) study performed by Keshimiri et al. [8] investigating and comparing the effectiveness of spiral ridge and helicity designs of bypass graft in inducing spiral blood flow, their result suggested that the helical design was significantly more effective than the spiral ridge in having a swirling flow within the anastomosis, neglecting the effect of anastomosis angle as this was kept constant in all trials, not clearly considering the potential of anastomosis angle in influencing on the flow pattern as this was not evaluated. In another study, Liu et al. [9] investigated the impact of helical grafts with and without taper on enhancing helical flow in both the graft and the host vessel. They have reported that a tapered helical graft improved the helical flow profile of the bypass graft compared to a tapered design. Similarly to the previous study, they did not examine the effect of anastomosis angle on influencing the hemodynamic behavior of blood flowing in the graft. Further exploration into graft geometry was undertaken by Totorean et al. [12]. Their study aimed to understand the fluid dynamics of various helical configurations of bypass grafts. By altering the amplitude of the helical structure, they compared which geometry produced the most favorable outcome. Their findings suggest that increasing amplitude led to higher helicity and vorticity of blood flow. Despite these insights, the study did not investigate other influential parameters, such as helical pitch, nor assess the interaction between helical geometry and anastomosis angle. Moreover, Apan et al. investigated the introduction of a ridge in bypass grafts to elicit spiral flow and enhance blood hemodynamics by altering the anastomosis angle [13]. They found that the anastomosis angle significantly affects hemodynamic disturbances, with smaller angles minimizing pressure drop, reducing areas affected by recirculation, and lowering abnormally high wall shear stress, all factors related to bypass graft failure. Ultimately, they found that spiral flow bypass grafts outperformed conventional bypass grafts due to the ridged geometry of their design. These studies highlight the potential of spiral and helical graft designs to improve hemodynamic performance. However, underscoring the need for further research, they also reveal gaps in the literature, particularly regarding the role of anastomosis angle and its interaction with graft geometry, which this paper tries to explain, studying the effect of anastomosis angle, helical diameter, and helical pitch by changing them and understanding their impact on having an optimal arteriovenous bypass graft.

In this study, the researchers aim to design and optimize the parameters of a helical arterio-venous bypass graft (AVG) to improve vascular access performance. The focus is on developing 3D graft models with variations in anastomosis angles, helical diameters, and helical pitches. Using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis, each graft design is evaluated based on its hemodynamic performance. Key indicators such as wall shear stress (WSS), time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT) are measured to assess blood flow behavior and potential for complications such as thrombosis or intimal hyperplasia. The final step compares the optimized helical AVG design with a conventional bypass graft model to determine its relative effectiveness and potential clinical advantages, especially in improving patient outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of 3D Graft Geometrical Models

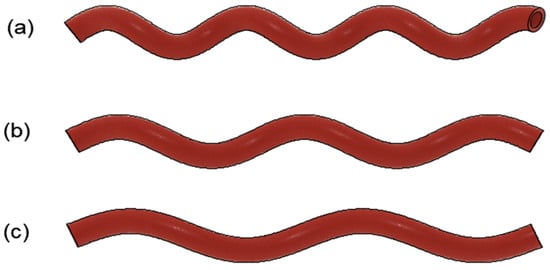

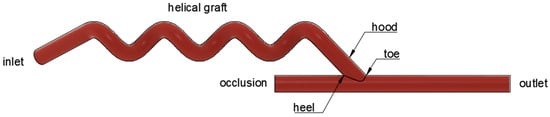

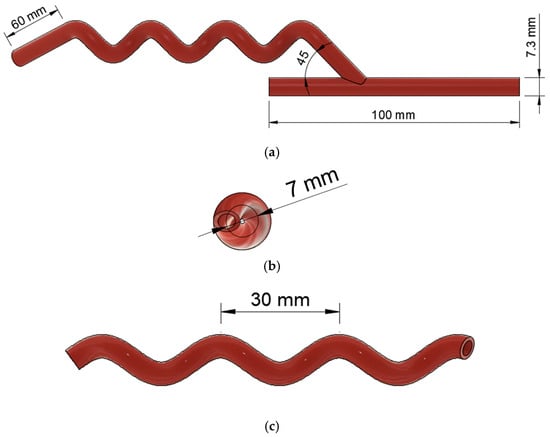

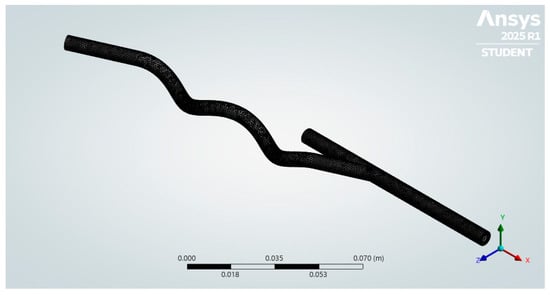

The 3D geometrical models for this study were entirely generated from Autodesk Fusion 360 software, generally described in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3. Each model had its unique parameters that aided the researchers in selecting the most favorable design.

Figure 1.

Sample helical arterial bypass graft model with varying helical pitches. (a) HP = 30 mm; (b) HP = 40 mm; (c) HP = 50 mm.

Figure 2.

Parts of the helical arterio-venous bypass graft.

Figure 3.

Geometrical model of helical arterio-venous bypass graft with model number 45-7-30. (a) The front view shows the anastomosis; (b) the right-side view presents the helical diameter; and (c) the front view indicates the helical pitch.

Table 1 shows the different parameters to be selected and determined to create the optimized bypass graft. To check the effect of anastomosis angles on hemodynamic disturbance, the researchers used anastomosis angles of 25°, 35°, and 45°. Since no past studies explored the impact of varying helical diameter and helical pitch on the flow performance of a bypass graft, the values were used according to the range of values garnered from the related literature. The researchers also added values close to the literature to verify if other values may generate better results. Thus, the graft design parameters had three (3) different anastomosis angles in degrees, three (3) different helical diameters in millimeters, and three (3) different helical pitches in millimeters.

Table 1.

Graft design parameters.

Based on Table 2, there were twenty-seven (27) 3D helical arterial bypass graft models with varying anastomosis angles (AAs), helical diameters (HDs), and helical pitches (HPs). In identifying the model, a corresponding code number format was assigned AA-HD-HP per geometry, which indicates the Anastomosis Angle–Helical Diameter–Helical pitch. Based on the CFD simulation results, the researchers utilized the combinations of these design parameters to select the best helical bypass graft design.

Table 2.

Graft design selection.

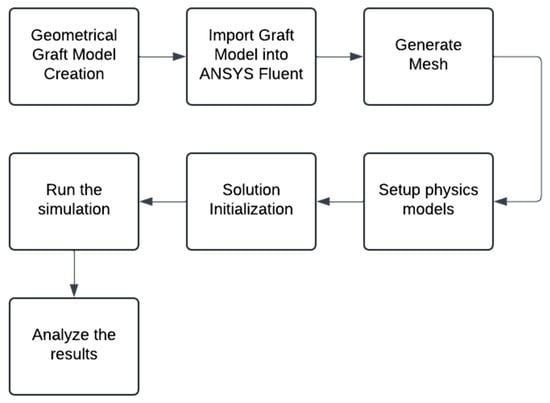

2.2. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Simulation

To analyze the effect of the anastomosis angle (AA), helical diameter (HD), and helical pitch (HP) on the helical arterial bypass graft, both steady-state and transient CFD simulation was conducted using the ANSYS Fluent 2025 Student Version, process is summarized in Figure 4. A steady-state CFD simulation characterized hemodynamic parameters, including area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS), pressure drop, and helicity. On the other hand, transient CFD simulation was employed to offer time-dependent hemodynamic parameters, including time-average wall shear stress (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT). The 3D graft models were discretized into a computational mesh for CFD analysis, and appropriate boundary conditions were defined to govern fluid flow through the graft.

Figure 4.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) analysis step-by-step procedure.

2.2.1. Geometry Import

The generated geometry was transferred into ANSYS Fluent software for further processing. This step checked the model for faults or mistakes that could have hindered the meshing.

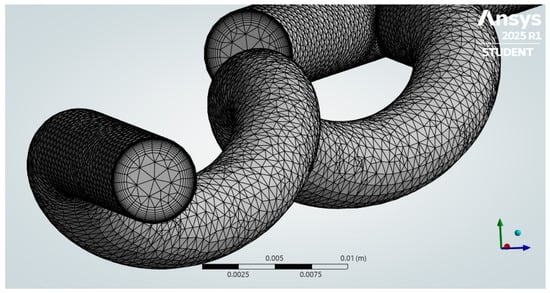

2.2.2. Mesh Generation

The ANSYS Meshing was used for this section of the study. A finite-volume hybrid mesh was used as a basis for the computational domain as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The mesh consistently maintained an orthogonal quality over 0.10 to guarantee high-quality simulations. An average number of 430,000 elements were used to achieve the results that the researchers aim for. The selection of elements and mesh sizing parameters was guided using the available literature in the same field of study and tutorial resources, which served as the primary reference for this study due to the limited availability of other instructional materials. This approach ensured consistency with established modeling practices demonstrated in prior studies and provided a validated framework for achieving reliable and reproducible simulation results.

Figure 5.

Hybrid mesh generated.

Figure 6.

A hybrid mesh was generated, showing the inlet walls with inflation.

2.2.3. Setup Physics Model

An upstream extension zone was incorporated before the graft inlet to minimize the influence of boundary conditions and allow the pulsatile velocity profile to develop into a realistic flow before reaching the graft. Steady-state CFD simulations employed a pressure-based solver suitable for incompressible laminar blood flow, with the Carreau model used to capture its non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior across low and high shear rates [14,15]. The zero-shear viscosity was set to 0.056 Pa·s, the infinite-shear viscosity to 0.0035 Pa·s, the time constant to 3.313 s, and the power-law index to 0.3568, similar to a reported study investigating the effect of ridged bypass graft in eliciting helical flow [13]. A constant inlet velocity of 0.3 m/s was applied, with zero pressure specified at the outlet, while the vessel walls were modeled as rigid with a no-slip boundary condition. This configuration ensured a physiologically realistic flow profile entering the graft and reduced artificial numerical effects caused by boundary conditions. For transient simulations, the same solver type, laminar flow model, working fluid, and viscosity model were employed.

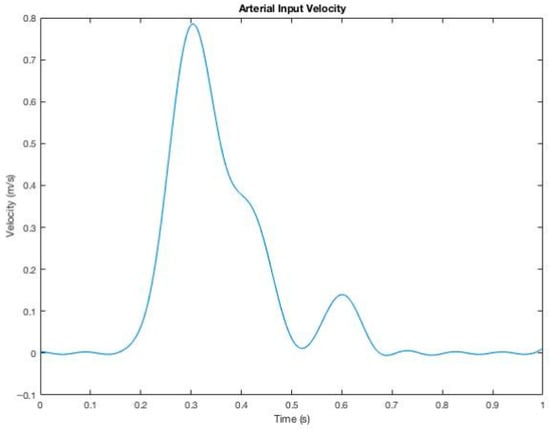

The arterial inlet velocity reported in the literature illustrated in Figure 7 on arteriovenous grafts was adopted as the inlet boundary condition in this research [16]. The transient simulation in ANSYS Fluent was executed for three initial periods to stabilize the residuals, after which data sampling was performed during the fourth period. Each period consisted of 25 time steps, with a maximum of 20 iterations per time step.

Figure 7.

Pulsatile velocity profile imposed on the inlet for transient CFD simulations.

2.2.4. Solution Initialization

A hybrid initialization was employed for simulation under steady-state conditions. Hybrid initialization is typically recommended since it computes an initial flow field by solving a Laplace equation for velocity and pressure in compliance with the boundary conditions. A more accurate initial condition enhances convergence for intricate flow fields, particularly in irregular geometries such as a helical bypass graft [17]. For the transient simulation, a standard initialization was used. It sets uniform values for velocity, pressure, and turbulence parameters based on user-defined inputs or inlet conditions. This method ensures a stable starting point for time-dependent calculations, preventing numerical instabilities [17].

2.2.5. Running the Simulations

The selected solver guided the simulation until the residuals for momentum, continuity, and energy variables dropped below a designated threshold; the solver iteratively processes the governing fluid dynamics equations, indicating convergent behavior. The criterion for the declining residuals for this work was 10−6 [13].

2.2.6. Analysis of the Results

In analyzing the results of the computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation, critical insights into the hemodynamic performance of the helical bypass graft were obtained. Post-processing involved visualizing and interpreting hemodynamic parameters such as area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS), pressure drop, and helicity. Moreover, time-dependent hemodynamic metrics, including time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT), were evaluated.

2.3. Data Validation of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Process

Before proceeding with the simulation of the helical arterial bypass graft models, the results were compared to the study of Abdulwahhab et al. [18]. The researchers determined the percentage difference (%) of the outlet pressure and outlet velocity between the CFD simulation and the reference study. A low percentage difference (%) signified that the researchers’ CFD simulation process was correct and reliable.

2.4. Selection of the Best Helical Arterio-Venous Bypass Graft

The researchers determined the best design parameters of the helical arterio-venous bypass graft (AVG) according to the results of the ANSYS Fluent Simulation. This study used two stages of CFD simulation. Under steady-state CFD simulations, the area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS), pressure drop, and helicity magnitude were acquired. In stage 1 of the simulation, the four (4) best helical arterio-venous bypass grafts were selected according to the selection criteria shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selection criteria for the best helical arterio-venous bypass graft.

According to Bernad et al., a pressure drop below five mmHg or 667 Pa is often considered safe for human application [19]. On the other hand, Zhou et al. stated that the wall shear stress (WSS) a blood vessel can withstand is 1 Pa to 6 Pa [20]. For the oscillatory shear index (OSI), an OSI value of less than 0.2 is considered safe. Moreover, it was determined by Tzikaris et al. that the safe time-averaged wall shear stress in healthy human coronary arteries is more significant in greater than 0.4 Pa [21].

The best helical arterio-venous bypass graft models derived in stage 1 of the selection underwent stage 2. Stage 2 of the selection process of the best helical arterio-venous bypass graft was based on time-dependent hemodynamic parameters such as time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT). To determine the best helical arterio-venous bypass graft (AVG), the model must have had the highest TAWSS, lowest OSI, and lowest RRT while still within physiological values, as shown in Table 3.

2.5. Comparison Between the Optimized and Conventional Arterio-Venous Bypass Graft (AVG)

To determine the efficiency of the helical arterio-venous bypass graft, it is numerically compared to the bypass graft simulated using a spiral ridge bypass graft designed and conducted by Xenakis et al. [22]. The researchers compared the area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS), helicity, and area with abnormally low wall shear stress (<1 Pa). The researchers computed the percentage difference (%) to determine how close or far the CFD simulations were and drew better conclusions according to the same selection criteria shown in Table 3.

3. Results

3.1. Data Validation

Before proceeding with the helical arterio-venous bypass graft model simulation, quantitative data validation was conducted using the CFD simulation results performed by Nimadge and Chopade [23].

Table 4 presents a velocity data validation comparison between CFD results and literature values for a T-joint pipe. The literature and CFD comparison shows that at the inlet, both indicate a velocity of 2.05 m/s, reflecting a 0% discrepancy, evidence that the simulation accurately captures the intake circumstances. At one outlet oriented at 90°, the literature value is 1.36 m/s; however, the CFD result is 1.1275 m/s, resulting in a notable 18.69% discrepancy. This discrepancy may stem from mesh resolution, turbulence modeling, or boundary conditions that necessitate enhancement in the CFD configuration. Furthermore, flow division in T-junction geometries is highly sensitive to small perturbations in the numerical setup, where secondary vortices and localized recirculation zones can significantly alter outlet velocities. The rigid wall and laminar flow assumptions adopted in this study may also neglect subtle transitional effects present in experimental conditions, further contributing to the variation.

Table 4.

Velocity (m/s) data validation between the CFD results and the literature.

Nevertheless, this deviation remains localized to a single outlet. At the same time, the inlet velocity was reproduced with 0% difference, and pressure validation exhibited discrepancies below 5%, both of which fall within acceptable CFD accuracy ranges reported in the literature. The accuracy of the simulation in this domain is validated by the secondary 90° outlet, which demonstrates a strong correlation between the literature value of 1.20 m/s and the CFD result of 1.2009 m/s. The discrepancy was found to be 0.0749%.

Table 5 displays a validation comparison of pressure (Pa) between Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) results and published literature values for a T-joint pipe. The literature and CFD results at the intake indicate a pressure of 2903 Pa, demonstrating a 0% discrepancy, hence confirming the simulation accurately reflects the inlet circumstances. The literature pressure at the initial 90° outlet is 1814.23 Pa, whereas the CFD result is 1765.88 Pa, yielding a 2.70% discrepancy. This difference explains that the CFD model accurately forecasts pressure at this exit despite potential minor discrepancies due to turbulence effects or numerical approximations. Simultaneously, at the secondary 90° outlet, the literature value is 1588.68 Pa. The CFD result is 1669.79 Pa, resulting in a 4.98% discrepancy, which is warranted to be greater than the initial outlet but remains within an acceptable range for CFD models. The CFD model has strong concordance with the published values, with discrepancies remaining under 5%, which is often adequate for fluid flow simulations. The minor inconsistencies may be ascribed to turbulence modeling, mesh resolution, or boundary condition configurations.

Table 5.

Pressure (Pa) data validation between the CFD results and the literature.

3.2. Area-Weighted Average Wall Shear Stress (AWA-WSS)

The tangential force per unit area a flowing fluid applies to a conduit tube’s surface is known as wall shear stress, or WSS. The wall shear stress (WSS) magnitude directly correlates with the velocity gradient adjacent to the tube wall. This pertains to the rate at which flow velocity escalates when transitioning from a place on the tube wall to an adjoining site in a direction perpendicular to the wall, towards the tube’s center shown in Figure 8 [24].

Figure 8.

Host artery wall.

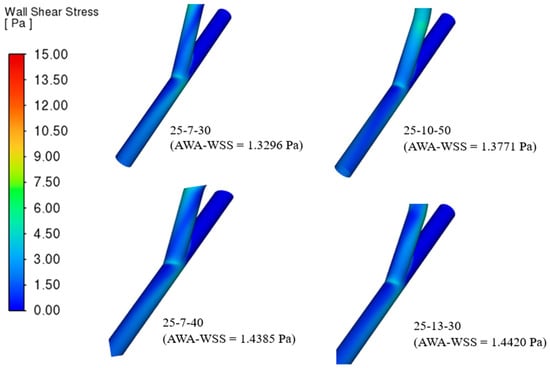

Presented in Figure 9 are the four best-performing helical bypass graft models, evaluated based on the area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS) criterion shown in Table 3. Each model is labeled with its geometric parameters and corresponding AWA-WSS values ranging from 1.3296 Pa to 1.4420 Pa. Among them, the 25-13-30 model exhibits the highest AWA-WSS at 1.4420 Pa, while the 25-7-30 model has the lowest at 1.3296 Pa.

Figure 9.

The four (4) best helical bypass graft models according to the area-weighted average wall shear stress (AWA-WSS) criterion.

The color scale on the left, ranging from 0 Pa (blue) to over 15 Pa (red), represents the distribution of wall shear stress (WSS), indicating regions of low to high stress. Across all grafts, most WSS values fall within the low to moderate range (blue to green), with minimal high-stress zones. Variations in arterial angle, helical diameter, and helical pitch alter the curvature and torsion of the graft, influencing how blood accelerates, decelerates, and swirls along the vessel wall [10]. WSS is proportional to the velocity gradient at the wall; therefore, smoother and more uniform flow tends to produce lower WSS. On the other hand, grafts with sharper turns or tighter helical shapes generate secondary flows, increasing velocity gradients and WSS.

Although Figure 9 predominantly shows low to moderate WSS magnitudes, small localized regions of higher WSS can be observed near the anastomotic junction and along inner curvatures of the helical segments. These localized peaks are expected and physiologically realistic, as flow impingement and curvature-induced secondary motion in helical grafts naturally generate transient velocity gradients near these zones. However, their limited visibility in the color map may stem from the broad WSS scale (0–15 Pa), which visually compresses higher gradients into narrower color bands. Numerically, these high-WSS spots are not artifacts, as mesh refinement and convergence tests confirmed grid independence and stability of the computed WSS values. Nonetheless, slight variations may still arise due to local mesh resolution at the anastomosis and curvature interfaces inherent to CFD discretization.

In this context, the 25-7-30 model likely has the lowest AWA-WSS due to its gentler curvature or longer flow path, which smooths velocity gradients. In contrast, the 25-13-30 model’s wider helical diameter likely pushes the flow closer to the vessel wall, increasing the velocity gradient and resulting in higher WSS. This is also evident in those geometries with higher helical diameter and helical pitch in Table S1. The model 25-10-50, which has the highest helical pitch, clearly has a high WSS at the hood proximal to the anastomosis origin, minimally observed as well in the 25-7-40 model, suggesting that higher helical pitch affects the AWA-WSS of a bypass graft.

3.3. Pressure Drop

The variation in pressure between two designated locations inside a system is called pressure drop. The phenomenon is frequently attributed to friction or flow resistance from walls, junctions, or impediments. The pressure differential between the entry and exit sites determines the resistance level, denoting the extent of friction, static, and acceleration pressure reductions experienced by the fluid between two designated points [21].

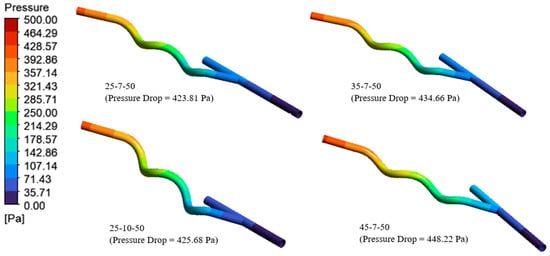

Figure 10 presents the four (4) best helical bypass graft models based on the pressure drop criterion, with pressure values ranging from 423.81 Pa to 448.22 Pa. The 25-7-50, 35-7-50, 25-10-50, and 45-7-50 demonstrate comparatively low pressure decreases, signifying efficient blood flow with minimum resistance. Of the options, 25-7-50 exhibits the lowest pressure drop (423.81 Pa), rendering it the most efficient in minimizing the flow resistance of the blood, whereas 45-7-50 has the highest pressure drop (448.22 Pa), albeit remaining within an acceptable range shown in Table S2.

Figure 10.

The four (4) best helical bypass graft models according to the pressure drop criterion.

The results demonstrate that the anastomosis angle and helical diameter strongly influence flow resistance. Larger angles, which correspond to sharper curvature, tend to induce greater flow separation and secondary flows, as observed in the 45-7-50 model. This effect increases energy loss and consequently elevates the pressure drop. The trend is consistent with the observed increase in pressure drop as the anastomosis angle increases. Conversely, smaller angles with smoother curvature, as in the 25-7-50 model, promote more streamlined flow, reducing turbulence and minimizing energy loss. Lower pressure drops are generally preferred in graft design as they allow blood to pass with minimal resistance, potentially reducing the workload on the heart. However, this must be balanced against the need to maintain adequate wall shear stress to prevent intimal hyperplasia [10].

3.4. Helicity

Helicity refers to the degree of coiling and wrapping of velocity field lines. In fluid flow, helical patterns resembling a corkscrew may develop [10]. Incorporating helicity into graft design can enhance long-term patency and reduce the risk of graft failure due to thrombosis or restenosis [9]. This improvement results from the swirling or helical flow generated within the graft, which minimizes the size and duration of recirculation zones and stagnant regions, where low wall shear stress and oscillatory shear stress typically promote intimal hyperplasia and thrombus formation. The secondary flows induced by helicity enhance mixing and improve the uniformity of wall shear stress, thereby supporting endothelial health and suppressing pathological changes in the vessel wall. Furthermore, helical flow decreases the oscillatory shear index and relative residence time, critical factors linked to vascular graft complications [15].

Table 6 displays the helicity values (m/s2) for various helical bypass graft models, illustrating the impact of differing anastomosis angles, helical diameters, and helical pitches on rotational flow. The helicity values fluctuate considerably based on the graft form, from 0.6369 m/s2 (25-13-30) to 9.4276 m/s2 (45-13-50).

Table 6.

Helicity results.

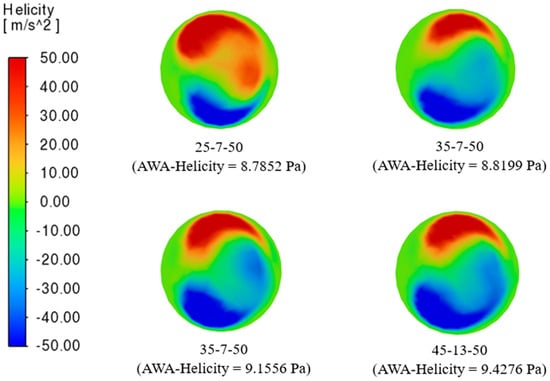

Figure 11 presents the four optimal helical bypass graft models based on the helicity criterion, ranging from 8.7852 m/s2 to 9.4276 m/s2. Models such as 45-10-40, 35-7-50, 45-7-50, and 45-13-50 exhibit elevated helicity levels, indicating strong rotational flow characteristics. Helicity is a hemodynamic parameter, representing the alignment between flow velocity and vorticity. Higher helicity values generally correspond to stronger and more coherent swirling flows, promoting uniform wall shear stress (WSS) distribution and reducing flow stagnation or recirculation zones that may contribute to intimal hyperplasia [10].

Figure 11.

The four (4) best helical bypass graft models according to the helicity criterion.

Though relatively close in magnitude, the observed AWA-helicity values reveal subtle differences influenced by graft geometry. Grafts with smaller anastomosis angles tend to produce smoother but slightly less intense swirling motions, resulting in lower helicity values. In contrast, larger helical diameters and pitches push the flow off-center along a spiral trajectory, increasing the intensity of rotational motion and, consequently, helicity. The color distribution in the cross-sectional views highlights intense positive (red) and negative (blue) helicity zones, representing counter-rotating flow structures. A balanced distribution across all models suggests consistent swirling behavior, although the intensity and symmetry vary with geometric configuration. Maintaining moderate-to-high helicity within bypass grafts is advantageous, as it supports a uniform WSS environment and reduces the formation of low-shear regions susceptible to plaque development [25].

3.5. Selection of the Best Helical Arterio-Venous Bypass Graft (AVG) Based on CFD Transient Simulations

Pasta et al. stated that the Time-Averaged Wall Shear Stress (TAWSS) can be determined by integrating the amplitude of each nodal WSS vector along the vessel wall throughout the cardiac cycle [26]. Essentially, over one complete cardiac cycle, TAWSS characterizes the mean magnitude of the shear force exerted by the fluid on the vessel wall of the designed bypass graft. This is mathematically expressed in Equation (1):

where represents the instantaneous wall shear stress at time t, and T is the duration of one cardiac cycle. The factor normalizes the integral by the cycle length, ensuring that the computed value represents the average shear stress magnitude over time, rather than the cumulative stress applied during the cycle. While TAWSS reflects the overall magnitude of shear stress, the Oscillatory Shear Index (OSI), defined in Equation (2), characterizes directional changes by relating the net shear stress to the total magnitude, capturing the degree of flow oscillation during pulsatile conditions. This is particularly important for viscoelastic and non-Newtonian fluids such as blood. Complementing TAWSS in hemodynamic assessment, OSI provides insight into the directional variations in shear stress throughout the cardiac cycle, and together, these metrics offer a more complete evaluation of the mechanical environment experienced by the vessel wall.

Building on these parameters, illustrated in Equation (3), the Relative Residence Time (RRT) combines information from both TAWSS and OSI to highlight regions of low and highly oscillatory shear stress, thereby identifying areas of disturbed blood flow [27].

Higher RRT values indicate regions of low, oscillatory shear, which are associated with increased blood residence time near the wall and may contribute to endothelial dysfunction and atherogenic processes [28].

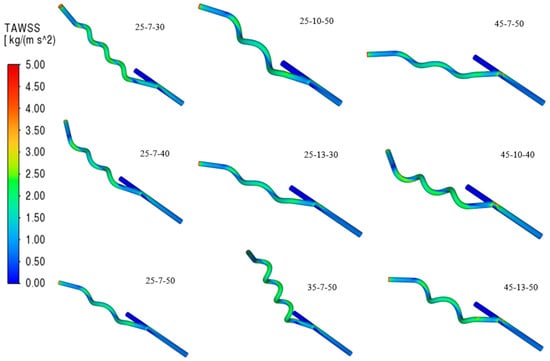

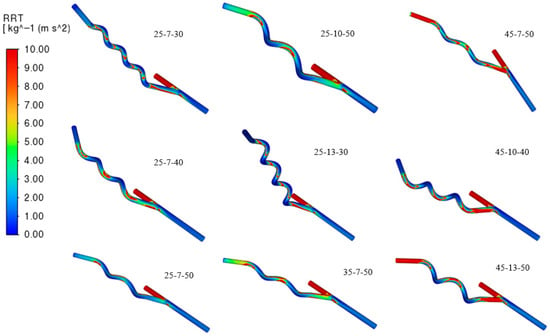

Summarized in Table 7 are the compiled grafts with the best performance from the steady-steady state simulation from stage 1 of this study, subject to further simulation to capture the effect of transient time-dependent simulation on the graft, and to further analyze the best helical arteriovenous bypass graft. It is evident from Table 7 described as well in Figure 12 that increasing the helical pitch, observed in 25-7-(30,40,50), decreases TAWSS. A higher helical pitch performs closer to a straight tube, which has a weaker swirling and mixing, resulting in a streamlined flow, so the near-wall velocity gradient decreases. This phenomenon is also evident in the 45-(10,13)-(40,50) model. Also, a lower anastomosis angle results in a higher TAWSS. Moreover, OSI reveals the strength of the changes in the direction of wall shear stress changes and can have a value from 0 to 0.5; typically, a value of 0.5 correlates to atherosclerosis or thrombosis [29].

Table 7.

Transient CFD simulation results.

Figure 12.

Contours of Time-Averaged Wall Shear Stress (TAWSS).

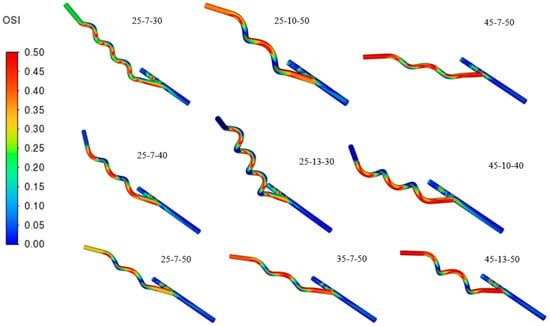

Evident from Figure 13, increasing the helical pitch results in a higher OSI in the flow of the graft, considering that it loses the swirling flow, stabilizing the hemodynamics of the blood, meaning blood can decelerate and recirculate near the wall. These recirculation cause changes in shear stress direction during the cardiac cycle. Similarly, grafts with higher anastomosis angles exhibit elevated OSI values due to the sharper entry of blood into the host vessel, which promotes flow separation and the formation of vortical structures. A high pitch and a large angle amplify oscillatory shear, creating disturbed flow regions strongly associated with thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Moreover, relative residence time (RRT) also increases in areas with low TAWSS and high OSI since blood particles remain near the wall for prolonged periods depicted in Figure 14. Grafts with high pitch or high angle show greater RRT values, highlighting the strong connection between these hemodynamic indices.

Figure 13.

Contours of Oscillatory Shear Index (OSI).

Figure 14.

Contours of Relative Residence Time (RRT).

Transient CFD simulation data indicate that the 25-13-30 graft model achieves the highest TAWSS value of 1.4604 Pa, fulfilling the condition for maximizing wall shear stress. It also demonstrates the lowest OSI value of 0.1461, suggesting improved flow stability and reduced directional changes in shear stress. The RRT for this model was calculated at 1.4621 Pa−1, which remains within an acceptable range, although not the lowest among all models. Significantly, since higher RRT values are typically associated with prolonged particle residence near the vessel wall and are often linked to an increased risk of thrombosis and atherosclerosis, the relatively moderate RRT of the 25-13-30 model does not outweigh its advantages of high TAWSS and low OSI. These results suggest that the 25-13-30 model provides a favorable hemodynamic environment for long-term graft performance.

3.6. Numerical Comparison Between the Helical Arterio-Venous Bypass Graft and the Conventional Bypass Graft

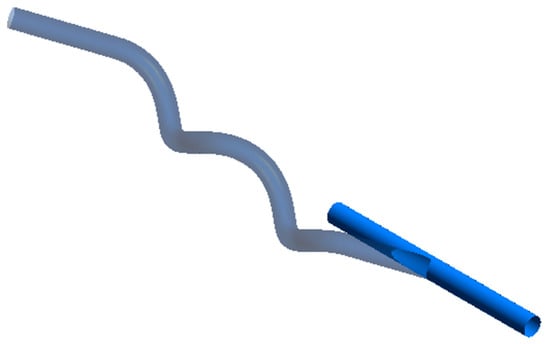

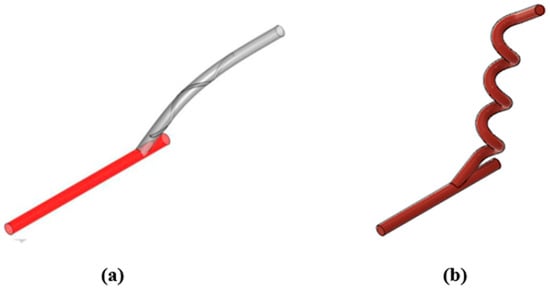

The selected helical arterio-venous bypass graft model is compared to a conventional bypass graft found in the literature presented in Figure 15 [22]. The numerical comparison aims to determine whether the helical design offers improved area-weighted average WSS, helicity, and area with low wall shear stress on the host artery wall.

Figure 15.

Design comparison between the study and the conventional bypass graft. (a) Internal spiral ridged bypass graft; (b) Helical bypass graft.

Based on these hemodynamic outcomes, the helical bypass graft performs better in two of the three evaluated parameters. Specifically, it shows a lower area-weighted average WSS (1.4420 Pa) and a smaller region of low-WSS exposure (8.08 mm2) on the host artery wall compared to the spiral-ridged graft. Although its helicity (1.1980 J/kg) is slightly lower, the advantages of reducing low-shear stress areas and ensuring more uniform shear stress distribution outweigh this limitation.

4. Discussion

Bypass grafts must be carefully optimized because their design directly influences the patient’s post-operative condition. Computational studies enable detailed analysis of the hemodynamic performance of blood flow within a designed bypass graft using computational fluid dynamics (CFD). Moreover, these studies can be coupled with finite element analysis (FEA) to evaluate the structural and mechanical behavior of the graft under physiological conditions, providing a comprehensive assessment of flow dynamics and graft integrity [30]. Sometimes, CFD partners with FEA to give a wider picture of what is happening in the graft. Hemodynamic parameters play a vital role in prolonging graft patency, and these parameters are strongly dependent on the geometric design of the graft. A poorly designed bypass graft can lead to failure by promoting conditions such as intimal hyperplasia, thrombosis, and atherosclerosis arising from disturbed hemodynamic flow. The swirling motion of blood flow helps maintain uniform mixing along the vessel pathway. This reduces the likelihood of recirculation zones and multidirectional flow patterns linked to vascular complications. Previous studies have investigated the effects of swirling motion and flow patterns in optimizing bypass graft performance. However, none have focused explicitly on helical bypass grafts combined with the influence of varying the angle of anastomosis. This study aimed to address that gap by investigating how changes in anastomosis angle, helical diameter, and helical pitch affect graft performance. Different geometric designs were developed and simulated using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to evaluate their hemodynamic properties. The results provide insight into how geometric modifications can optimize arterio-venous bypass grafts, ultimately supporting better patient outcomes.

4.1. Effect of Anastomosis Angle, Helical Diameter, and Helical Pitch on Hemodynamic Parameters

This study used a steady-state setup in the pressure-based solver, as it is suitable for incompressible and non-Newtonian fluids such as blood. This explained the behavior of the area-weighted average wall shear stress of the graft and the pressure drop and helicity, ensuring that these are within the range to avoid endothelial dysfunction, thereby reducing the risk of graft failure. Those that have a higher helical pitch tend to behave close to a straight tube, leading to a higher AWA-WSS value, especially to the hood proximal to the anastomosis site, as there is less mixing of blood layers. The wall shear stress near the graft hood and anastomosis site tends to increase as the flow impinges more directly on these regions. Higher wall shear stress (AWA-WSS) in these proximal regions is linked to changes in endothelial cell function and can influence thrombus formation and intimal hyperplasia development [22].

On the other hand, the anastomosis angle also affects the AWA-WSS, as increasing the angle also increases stress. Increasing the anastomosis angle increases wall shear stress by causing sharper flow deceleration, separation, and higher velocity gradients at the graft-vessel junction. This leads to localized regions of elevated shear stress and vascular stress.

Similarly, pressure drop is directly affected by the helical pitch and the anatomosis angle. Among the different geometries, all those with a helical pitch of 50 mm led to a lower pressure drop value than those with a 30 mm and 40 mm pitch. The tighter helices increase flow curvature and friction, raising resistance and causing higher pressure drops. The tighter spirals result in more energy dissipation because the fluid has to turn sharply and frequently, increasing viscous losses [31]. Nonetheless, the anastomosis angle plays a vital role in pressure drop, as increasing the angle results in a higher pressure drop in the graft. A larger anastomosis angle disrupts the smooth transition between the graft and the native vessel, leading to greater flow separation and turbulence at the junction. These disturbances increase the resistance, contributing to a higher pressure drop across the graft. This elevated resistance requires the heart to exert more force to maintain adequate blood flow, which can increase cardiac workload and potentially compromise graft function over time. Conversely, smaller anastomosis angles encourage more streamlined flow with reduced separation, minimizing energy losses and pressure drop [32]. Thus, optimizing the helical pitch and anastomosis angle is crucial in bypass graft design to balance enhanced hemodynamics, achieving strong swirling flow to prevent stagnation and intimal hyperplasia while maintaining acceptable pressure drops conducive to efficient cardiac workload.

The helical diameter and helical pitch directly influence the helicity of flow within the graft. As shown in Table 8, identifying an optimal helicity combination is challenging because helicity varies with different anastomosis angles. Generally, increasing the anastomosis angle and helical pitch leads to higher helicity. Helical pitch also determines the number of turns within the graft, which correlates with swirl strength and secondary velocity. Though relatively close in magnitude, the observed AWA-helicity values reveal subtle differences shaped by graft geometry. Grafts with smaller anastomosis angles tend to generate smoother but less intense swirling motions, resulting in lower helicity values.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of hemodynamic performance.

In contrast, larger helical diameters and pitches displace the flow along a spiral trajectory, intensifying rotational motion and increasing helicity. Cross-sectional color distributions highlight intense positive (red) and negative (blue) helicity zones, representing counter-rotating flow structures. While all models demonstrate consistent swirling behavior, the intensity and symmetry of these motions vary with geometric configuration.

4.2. Selection of the Best Helical Arterio-Venous Bypass Graft (AVG) Based on CFD Transient Simulations

The transient CFD simulations provide significant insights into the hemodynamic behavior of arterio-venous bypass grafts under varying geometric configurations, highlighting the role of design parameters in influencing graft performance and long-term patency. The results demonstrate that increased helical pitch reduces time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS) due to the diminished uniform mixing of blood, causing the graft to behave more like a straight conduit. Conversely, lower anastomosis angles are associated with higher TAWSS, as smaller angles promote efficient, laminar, and high-velocity flow along the vessel walls. In contrast, larger angles induce flow disturbances that reduce shear stress. Analysis of the oscillatory shear index (OSI) further reveals that grafts with higher helical pitch exhibit elevated OSI values, resulting from weakened swirling flow that compromises flow stabilization and leads to blood deceleration and recirculation near the wall. Moreover, grafts with larger anastomosis angles show increased OSI, as sharper blood entry angles encourage flow separation and the development of vortical structures. The interaction between high pitch and large angles amplifies oscillatory shear, generating disturbed flow regions strongly correlated with thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Relative residence time (RRT) also increases in areas of low TAWSS and high OSI, reflecting prolonged particle retention near the wall, which can exacerbate pathological processes.

4.3. Optimized Arterio-Venous Bypass Graft

Varying the geometric architecture of a bypass graft directly affects the hemodynamic performance of blood flow within the graft. Smaller anastomosis angles combined with moderate helical pitch improve hemodynamic parameters, including higher TAWSS and lower OSI, resulting in stable blood flow and enhanced endothelial function. Among the twenty-seven models, transient CFD results identify the 25-13-30 graft model as a strong candidate for bypass graft optimization due to its balanced hemodynamic profile. Its high TAWSS value indicates enhanced endothelial stimulation, a factor commonly associated with improved vascular adaptation and a lower likelihood of intimal hyperplasia. The low OSI value reinforces this advantage by indicating stable, unidirectional shear forces that reduce the oscillatory stresses often linked to endothelial dysfunction and disturbed flow. While the RRT for this model is not the lowest among those evaluated, its moderate level suggests that particle residence near the vessel wall remains within an acceptable range, limiting the risks of thrombosis and atherosclerosis. The elevated TAWSS, minimized OSI, and acceptable RRT indicate that the 25-13-30 model fosters a hemodynamic environment supportive of long-term graft patency. The 25-13-30 model behaves favorably in enhancing the patency of arteriovenous bypass grafts. In particular, compared to spiral ridged bypass grafts, it minimizes regions of critically low wall shear stress (<1 Pa), reducing the risk of neointimal hyperplasia and thrombosis, despite having lower helicity than spiral ridge grafts.

This holistic vascular graft study presents a geometry-driven framework for improving physiological compatibility, directly influencing hemodialysis access and cardiovascular bypass procedures. It addresses graft failures driven by the hemodynamic behavior of blood within the graft, thereby alleviating the possibility of post-operative complications such as thrombosis, atherosclerosis, and hyperplasia. For example, in hemodialysis AVGs, where repeated blood withdrawal and return can disrupt vascular homeostasis, implementing optimal graft geometries like the 25-13-30 model could help reduce flow disturbances that lead to intimal hyperplasia and other complications. The optimal configurations can improve graft patency, reduce complications, and enhance patient outcomes by outperforming conventional designs in key hemodynamic metrics.

In this study, the blood vessel walls were assumed to be rigid and non-deformable, and the flow was treated as laminar. These assumptions were adopted to simplify the analysis and focus on the geometric influence of the helical design. Although real vessels exhibit elasticity and expand with pulsatile flow, previous studies have demonstrated that the rigid-wall assumption can still provide reliable trends in wall shear stress and flow behavior for vessels of comparable size and pressure range [6,7]. Incorporating vessel compliance through fluid–structure interaction (FSI) modeling would substantially increase computational cost without significantly affecting the comparative evaluation among graft geometries. Similarly, the laminar flow assumption was considered appropriate since blood flow in arteriovenous grafts typically remains below the critical Reynolds number for turbulence (Re < 2300) [10,19]. While localized flow disturbances may occur near the anastomosis, their influence on the overall hemodynamic parameters, such as AWA-WSS, OSI, and RRT is expected to be minimal.

Despite these reasonable simplifications, the modeling assumptions should be acknowledged. The rigid-wall approach omits vessel compliance and the dynamic interaction between pulsatile flow and wall deformation, which could slightly alter local shear stress distribution. In addition, while the Carreau model effectively captures the shear-thinning behavior of blood, it does not account for viscoelastic or particulate effects that may arise under transient or mildly turbulent conditions. Consequently, the quantitative results of this study should be interpreted as relative comparisons between graft designs rather than absolute physiological values. Future work incorporating FSI simulations and more advanced rheological models could further improve the physiological accuracy of helical bypass graft analyses.

5. Conclusions

This work aimed to create 3D geometrical models of helical arterio-venous bypass grafts with different anastomosis angles, helical diameters, and helical pitches and choose the optimal model depending on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation results. This work’s simulations of hemodynamic parameters included area-weighted wall shear stress (AWA-WSS), helicity, and pressure drop using steady-state analysis. On the other hand, transient analysis was used to simulate time-dependent hemodynamic parameters such as time-average wall shear stress (TAWSS), oscillatory shear index (OSI), and relative residence time (RRT). After the two-staged CFD simulation process, among the twenty-seven (27) helical arterio-venous bypass grafts, model 25-13-30 emerged as the best design with balanced shear stress, flow stability, and thrombosis prevention for improved vascular performance. After comparing it with the conventional graft, the helical arterio-venous bypass graft emerged as having a better design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152011064/s1, Table S1. Area-Weighted Average Wall Shear Stress (AWA-WSS) results. Table S2. Pressure drop results. Table S3. Transient CFD simulation results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B., J.M., J.H. and L.T.; methodology, J.B., J.M., J.H. and L.T.; software, J.B. and J.M.; validation, J.B. and J.M.; formal analysis, J.B., J.M., and W.J.A.; investigation, J.B., J.M., and W.J.A.; resources, J.B. and J.M.; data curation, J.B. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.B., J.M., W.J.A., J.H. and L.T.; visualization, J.B. and J.M.; supervision, J.H. and L.T.; project administration, J.B., J.M., J.H. and L.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramsingh, R.; Bakaeen, F.G. Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Practice Trends and Projections. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2025, 92, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, D.; Pigliafreddo, A.; Casarella, S.; Di Nunno, L.; Mantovani, D.; Boccafoschi, F. Biological Materials for Tissue-Engineered Vascular Grafts: Overview of Recent Advancements. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafron, J.M.; Heng, E.E.; Boyd, J.; Humphrey, J.D.; Marsden, A.L. Hemodynamics and Wall Mechanics of Vascular Graft Failure. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1065–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, M.; Brenner, B. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s the Kidney, 7th ed.; Elsevier Saunders: Edinburgh, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jennette, J.C.; Stone, J.R. Diseases of Medium-Sized and Small Vessels. In Cellular and Molecular Pathobiology of Cardiovascular Disease; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Donadoni, F.; Bonfanti, M.; Pichardo-Almarza, C.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S.; Dardik, A.; Díaz-Zuccarini, V. An in Silico Study of the Influence of Vessel Wall Deformation on Neointimal Hyperplasia Progression in Peripheral Bypass Grafts. Med. Eng. Phys. 2019, 74, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadoni, F.; Pichardo-Almarza, C.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S.; Dardik, A.; Díaz-Zuccarini, V. Multiscale, Patient-Specific Computational Fluid Dynamics Models Predict Formation of Neointimal Hyperplasia in Saphenous Vein Grafts. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2020, 6, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, J.M.; Kolega, J.; Meng, H. High Wall Shear Stress and Spatial Gradients in Vascular Pathology: A Review. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 41, 1411–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Kang, H.; Fan, Y.; Sun, A.; Deng, X. Bioinspired helical graft with taper to enhance helical flow. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 3643–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabinejadian, F.; McElroy, M.; Ruiz-Soler, A.; Leo, H.; Slevin, M.; Badimon, L.; Keshmiri, A.; Sznitman, J. Numerical Assessment of Novel Helical/Spiral Grafts with Improved Hemodynamics for Distal Graft Anastomoses. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.C.; Larman, A. Investigation of Spiral Blood Flow in a Model of Arterial Stenosis. Med. Eng. Phys. 2009, 31, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Totorean, A.F.; Bernad, S.I.; Susan-Resiga, R.F. Fluid dynamics in helical geometries with applications for bypass graft. Appl. Math. Comput. 2016, 272, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apan, J.J.; Tayo, L.; Honra, J. Numerical Investigation of the Relationship between Anastomosis Angle and Hemodynamics in Ridged Spiral Flow Bypass Grafts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzizisis, Y.S.; Coskun, A.U.; Jonas, M.; Edelman, E.R.; Feldman, C.L.; Stone, P.H. Role of Endothelial Shear Stress in the Natural History of Coronary Atherosclerosis and Vascular Remodeling. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajihah, S.A.; Sankar, D.S. A Review on Non-Newtonian Fluid Models for Multi-Layered Blood Rheology in Constricted Arteries. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2023, 93, 1771–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis of Arteriovenous Graft Configurations. Master’s Thesis, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, P.; Ranade, R.; Choudhry, S. Accelerating Transient CFD through Machine Learning-Based Flow Initialization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahhab, M.; Injeti, N.K.; Dakhil, S.F. CFD Simulations and Flow Analysis Through a T-junction Pipe. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2012, 4, 3392–3407. [Google Scholar]

- Bernad, S.I.; Bosioc, A.I.; Bernad, E.S.; Craina, M.L. Helical type coronary bypass graft performance: Experimental investigations. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2015, 26, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yu, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Gao, L.; Jian, W.; Wang, L. Wall shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1083547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzirakis, K.; Kamarianakis, Y.; Kontopodis, N.; Ioannou, C.V. Selection of Bifurcated Grafts’ Dimensions during Aorto-Iliac Vascular Reconstruction Based on Their Hemodynamic Performance. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenakis, A.; Ruiz-Soler, A.; Keshmiri, A. Multi-Objective Optimisation of a Novel Bypass Graft with a Spiral Ridge. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimadge, M.; Chopade, M. CFD Analysis of Flow through T-Junction of Pipe. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2017, 4, 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Katritsis, D.; Kaiktsis, L.; Chaniotis, A.; Pantos, J.; Efstathopoulos, E.P.; Marmarelis, V. Wall shear stress: Theoretical considerations and measurement methods. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2007, 49, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Hwang, D.; Choi, W.-R.; Baek, J.; Lee, S.J. Fluid-Dynamic Optimal Design of Helical Vascular Graft for Stenotic Disturbed Flow. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111047. [Google Scholar]

- Pasta, S.; Agnese, V.; Gallo, A.; Consentino, F.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Gentile, G.; Raffa, G.; Maalouf, J.; Michelena, H.; Bellavia, D.; et al. Shear Stress and Aortic Strain Associations With Biomarkers of Ascending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 110, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, J.; Urbina, J.; Valverde, I.; Tejos, C.; Irarrázaval, P.; Andia, M.; Uribe, S.; Hurtado, D. 3D Quantification of Wall Shear Stress and Oscillatory Shear Index Using a Finite-Element Method in 3D CINE PC-MRI Data of the Thoracic Aorta. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2016, 35, 1475–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenti, C.; Ziegler, M.; Bjarnegård, N.; Ebbers, T.; Lindenberger, M.; Dyverfeldt, P. Wall Shear Stress and Relative Residence Time as Potential Risk Factors for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in Males: A 4D Flow Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Case–Control Study. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2022, 24, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Cai, X.; Zhan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ao, H.; Wan, Y.; Luo, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Hemodynamic Evaluation of Different Stent Graft Schemes in Aortic Arch Covered Stent Implantation. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2021, 13, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren, F.; Tayo, L.L. Finite Element Analysis of ACL Reconstruction-Compatible Knee Implant Design with Bone Graft Component. Computation 2023, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Soler, A.; Kabinejadian, F.; Slevin, M.A.; Bartolo, P.J.; Keshmiri, A. Optimisation of a Novel Spiral-Inducing Bypass Graft Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghista, D.N.; Kabinejadian, F. Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Hemodynamics and Anastomosis Design: A Biomedical Engineering Review. Biomed. Eng. Online 2013, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).