Abstract

Dental materials are well-established, with stainless steel 316L (SS) still being a common choice for components such as pediatric crowns and abutments. However, SS has some drawbacks, particularly in terms of mechanical properties and, more importantly, aesthetics, due to its metallic gray color. In this sense, PEEK (polyetheretherketone) has emerged as a promising material for dental applications, combining good mechanical properties with improved aesthetic features. This study compared the cytocompatibility of PEEK TiO2 composite and SS using human fetal osteoblasts (hFOB) and human gingival fibroblasts (HGF). Cytocompatibility was evaluated over 1–7 days through metabolic activity and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assays. Additionally, bacterial adhesion was assessed using Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in both monoculture and co-culture. The results showed that both materials were non-cytotoxic and supported cell growth. Notably, after 7 days of culture, PEEK TiO2 surfaces promoted approximately 7% higher ALP activity than stainless steel, demonstrating a significantly enhanced osteogenic response (p < 0.01). Moreover, at day 7, PEEK TiO2 promoted ~25% higher metabolic activity in HGF cells compared to SS. Regarding the bacterial adhesion, it was consistently low in PEEK TiO2 for both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, with a marked reduction (~50%) observed for P. aeruginosa under co-culture conditions. PEEK TiO2 demonstrated enhanced biological performance and lower bacterial adhesion compared with SS, highlighting its potential as a biocompatible and aesthetically promising option for dental applications, including pediatric crowns.

1. Introduction

In clinical dentistry, a variety of materials are used, including metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites, each serving distinct functional and aesthetic purposes [1]. Metallic components, such as stainless steel, shape memory alloys, and titanium (Ti) alloys, are extensively employed across a broad spectrum of dental applications. These metals are used in the fabrication of dental implants, prosthetic screws, orthodontic appliances, and pediatric crowns, among other devices [2,3]. Their inherent properties, such as strength, durability, and biocompatibility, make them essential in both restorative and functional dental treatments [4].

Stainless steel (SS), especially low-carbon 316L, has been a traditional material used in dental applications due to its excellent mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and lower cost than other metals [5]. It has also been employed as screws [6] and dental implants [7], with one of its primary applications being in pediatric crowns [8]. Conversely, its high strength and elastic modulus do not match those of natural bone, resulting in stress shielding and subsequent bone resorption around dental implants [9]. In addition, the metallic gray color of these materials is considered aesthetically unappealing, both for dental implants and pediatric crowns.

Recent developments in biomaterials have led to the study of alternatives such as PEEK and its composites, which are emerging as key options due to their favorable combination of mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and low susceptibility to bacterial adhesion [10]. These attributes make PEEK a highly promising material for various dental applications, including bridges, implants, pediatric crowns, and other restorations [11]. Yet, PEEK faces significant clinical limitations regarding its chemical inertness and surface hydrophobicity [12]. To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed strategies such as surface modifications and bioactive coatings with materials like hydroxyapatite [13,14,15].

Infections associated with biomaterials used in dental applications remain a challenge [16]. Bacterial adhesion can result in biofilm formation, which may contribute to significant health complications for the patient [17,18]. In the oral cavity, biofilm formation is governed by the interaction of multiple bacteria that compete between them to adhere and proliferate on a material’s surface [16,19,20].

Substrate characteristics, such as surface charge, wettability, roughness, topography, and chemistry, play a critical role in modulating bacterial adhesion [21,22,23]. Nevertheless, the incorporation of nanoparticles, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), has been shown to reduce bacterial growth on the surface [21]. This feature is particularly relevant for PEEK TiO2 composites specifically developed for pediatric dental crowns, where antibacterial activity plays a key role in preventing bacterial plaque accumulation and the subsequent development of caries. In addition, it can provide the aesthetics of white color to PEEK [24] and increase the mechanical properties of the material, depending on the percentage added to the PEEK base material [25,26,27,28]. Moreover, the photocatalytic properties of TiO2 promote a biocidal action against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi [29,30]. Previous studies have also shown that, even without UV irradiation, the TiO2 maintains a significant antibacterial activity [28,31,32,33]. Additionally, to achieve disinfection, this type of non-contact biocidal action does not present a release of potentially toxic nanoparticles [32,34,35].

The aim of this study was to compare PEEK TiO2 and SS to demonstrate that PEEK TiO2 provides enhanced cytocompatibility and reduced bacterial adhesion, making it a promising alternative for dental applications, such as pediatric crowns. In this sense, two types of cells, representing the hard tissues (human fetal osteoblast cell line) and soft tissue (human gingival fibroblasts), were evaluated in terms of cytotoxicity from 1 day to 7 days in both materials. Cell morphology and adhesion were evaluated after 1 day and 7 days of culturing. Metabolic activity and alkaline phosphatase activity were also assessed at predefined times. Additionally, the microbiological response of PEEK reinforced with TiO2 and SS was assessed through the adhesion of Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative P. aeruginosa to the biomaterial surface. These two bacteria are associated with chronic wound infections and are frequently found together [36,37]. To assess the interactions between the two bacteria, a co-culture of both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was performed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimens

Two different materials, namely stainless steel 316L (SS) and PEEK (Dental Direkt Company, Spenge, Germany) composite reinforced with 20 wt–TiO2, were used in this study. The specimens were milled into circular pieces (∅ 8 mm × 2 mm thickness) from stainless steel 316L and PEEK commercial blocks. All specimens were subsequently polished using a MECAPOL P251 and sandpapers with grit sizes ranging from P800 to P4000 to achieve a smooth surface.

2.2. Surface Characterization

The roughness of five specimens from each material was measured by means of profilometry (Mitutoyo SJ 210, Kawasaki, Japan). For each specimen, three measurements were performed, and the result presented is the average of the obtained values. The measures were performed at a speed of 6 μm/s along the length of the sample, with measurements being acquired every 2.0 μm of dislocation.

Also, contact angle measurements were performed using an automatic instrument, Dataphysics equipment (DataPhysics, Filderstadt, Germany), with OCA20 software version 20, which presents a video system for the capturing of images in static modes. Distilled water was used for contact angle measurements; the drop had a volume of 5 µL and was released at a speed of 2 µL/s. Prior to the measurements, all specimens were ultrasonically cleaned with alcohol.

2.3. In Vitro Characterization

2.3.1. Cell Culture

The human fetal osteoblast cell line (hFOB 1.19; ATCC ®, VA, USA) was cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Ham’s F12 Medium Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium without phenol red (DMEM:F12; PanBiotech ®, Aidenbach, Germany) supplemented with 2.5 mM L- glutamine PanBiotech ®, Aidenbach, Germany), 0.3 mg/mL G418 (PanBiotech ®, Aidenbach, Germany), and 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Human gingival fibroblasts (HGF P10866, Innoprot, Bizkaia, Spain) were cultured under the same conditions of temperature, humidity, and atmospheric composition as hFOB. A distinct culture medium was used in HGF, as suggested by the supplier, constituted in Fibroblast medium (Innoprot, Bizkaia, Spain), and supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Innoprot, Bizkaia, Spain), 1% Fibroblast Growth (FGS), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution.

Both cell lines were maintained at 37 °C under 5% CO2 and 98% humidity. Upon reaching approximately 80% confluence, cells were trypsinized and seeded at passage eight (P8) for hFOB and passage three (P3) for HGF. A 20 µL cell suspension containing 5000 cells was deposited onto each sample in 48-well culture plates, as well as directly into the wells for controls. Two independent experiments were conducted at three time points (24 h, 72 h, and 7 days), with three technical replicates per material (total n = 6 per condition. After 3 h of cell adhesion, 500 µL of culture medium was added to each well, and the plates were returned to the incubator. All specimens were sterilized by autoclaving prior to testing.

2.3.2. Metabolic Activity

The metabolic activity of both hFOB and HGF was measured by the MTS Cell Proliferation Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA) at specific time points, namely, 1, 3, and 7 days after seeding. Briefly, for each sample, 300 µL of culture medium and 30 µL of reagent were added. After 3 h in the incubator, the volume of 150 µL of each well was transferred in duplicate to a 96-well plate for absorbance reading, using a microplate reader (Biotek, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 490 nm. Notably, the dye reagent was incubated with culture medium to create a blank, to subtract its absorbance from each sample.

2.3.3. Alkaline Phosphatase Quantification

For the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assessment, molecular absorbance spectrophotometry measurement was used with a fluorometric enzyme assay (Alkaline Phosphatase Activity Colorimetric Assay Kit, BioVisio, Ilmenau, Germany), according to manufacturer instructions. Standards and samples at specific time points were measured using a fluorescence spectrometer (Biotek Epoch, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 405 nm. Values were converted to glycine units (ALP) based on the standard regression equation.

2.3.4. Cell Adhesion and Morphology by Scanning Electron Microscopy

To assess the surface of both materials and the ability of cells to adhere and spread along the material surfaces, an ultra-high-resolution field-emission scanning electron microscope (Nova NanoSEM 200 microscope, FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) was used. For that, the specimens were collected after 1 and 7 days of culture and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution in PBS, followed by a wash with ultra-pure water, and dehydrated in increased concentrations of ethanol from 30% to 100% and air-dried overnight. Prior to observation through the SEM, the specimens were coated with gold.

The percentage of surface area covered by bacteria was quantified from the SEM micrographs using ImageJ 1.43 software. Micrograph contrast was adjusted to enhance bacterial contours and minimize background noise. Quantification was performed on single technical replicates of images acquired at 1500× magnification, corresponding to a surface area of 40.000 µm2 per condition, using image thresholding. All the measurements were performed in a single field per specimen, corresponding to the maximum image surface at magnification, with blind image analysis of the material and culture conditions. Single data are expressed as the percentage of surface coverage of each specimen, SS and PEEK, for each bacterial strain.

2.3.5. Bacterial Adhesion Protocol

In the present tests, two types of bacteria were used, namely S. aureus (CIP 76.25) and P. aeruginosa (CIP 76.110). The pre-inocula of each bacterium were prepared by incubation in tryptone soya broth (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Maharashtra India) medium at 37 °C and 120 rpm.

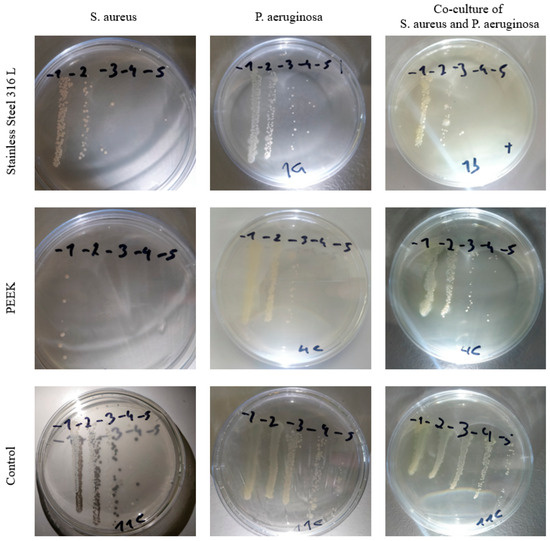

Three technical replicates of each condition were placed into 24-well plates and incubated with 1 mL of pre-inocula, with an initial bacterial concentration of 1 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL for each bacteria in monoculture (bacteria isolated) and with pre-inocula of both bacteria, with an inoculum ratio of 1:1 CFU, in co-culture (both bacteria cohabitate in the same media). The pre-inocula were adjusted by densitometry (Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer, Biotek, USA) at 600 nm to a McFarland standard optical density. The specimens remained in contact with pre-inocula for 24 h at 37 °C and 120 rpm. Afterwards, the broth was aseptically removed, and each specimen was inserted into a falcon tube with a 3 mL PBS solution. A 10 min ultrasonic bath (50/60 Hz, J.P. Selecta, Barcelona, Spain), followed by a 1 min vortex, was performed to detach the bacteria from specimen surfaces. Subsequently, 5 µL of each medium was poured into Petri dishes and incubated overnight at 37 °C to estimate the CFU/mL of each specimen (Figure 1), and the CFU were counted.

Figure 1.

Petri dishes of different conditions, evaluated after overnight growth.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software version 5.0a. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using unpaired t-tests. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Specimens’ Characterization

Table 1 displays the surface roughness (Ra) results; PEEK TiO2 presents higher roughness (0.083 ± 0.025 µm) compared with SS (0.028 ± 0.010 µm). Although both values remain within the range typically considered smooth, the increased micro-roughness of PEEK may provide additional anchoring sites for cell adhesion and contribute to improved bioactivity.

Table 1.

Mean ± standard deviation values of Ra for the polished specimen.

Also, contact angles were assessed, as shown in Table 2. The contact angle of SS was 80.1° ± 9.9, indicating a moderately hydrophilic surface, while PEEK TiO2 exhibited a contact angle of 91.5° ± 8.6, corresponding to a moderately hydrophobic surface. Surface wettability plays a key role in biological performance, as hydrophilic surfaces tend to promote protein adsorption and initial cell adhesion, whereas hydrophobic surfaces may reduce bacterial colonization.

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviation values of contact angle for polished specimens.

3.2. In Vitro Characterization

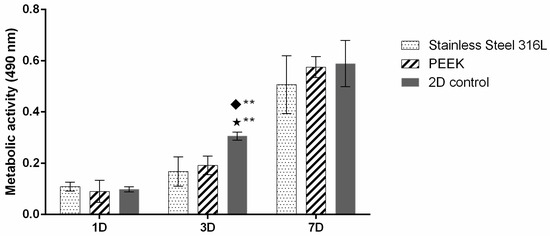

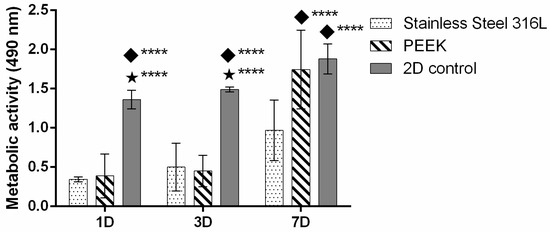

To evaluate the cell viability of both hFOB and HGF cells, metabolic activity was assessed, and the results are displayed in Figure 2. At day 1, no significant differences were observed among SS, PEEK TiO2, and the 2D control. By day 3, a significant increase in activity was detected in all groups, with the 2D control showing the highest values (p < 0.01). At day 7, both SS and PEEK TiO2 present markedly higher metabolic activity compared with earlier time points, with PEEK TiO2 exhibiting slightly higher values than SS.

Figure 2.

hFOB metabolic activity for up to 7 days of culture. Symbols denote statistically significant differences (** p < 0.01) in comparison to the following: (◆) Stainless Steel 316L; (⋆) PEEK. Data is presented as mean ± stdev (total n = 6 per condition).

To determine how different materials influence osteoblastic cell growth, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was assessed (Figure 3). ALP activity remained relatively stable at days 1 and 3 for all groups, with no statistically significant differences between SS, PEEK TiO2, and the 2D control. By day 7, however, a noticeable increase in ALP activity was observed in both SS and PEEK specimens, with PEEK TiO2 showing the highest values (p < 0.01 compared to day 1 and day 3). The elevated ALP expression at day 7 suggests enhanced osteogenic differentiation, particularly on PEEK TiO2 surfaces, supporting its potential for improved bone integration compared with SS.

Figure 3.

hFOB ALP activity for up to 7 days of culture. Symbols denote statistically significant differences (** p < 0.01) in comparison to the following: (■) 2D control; (◆) SS. (total n = 6 per condition).

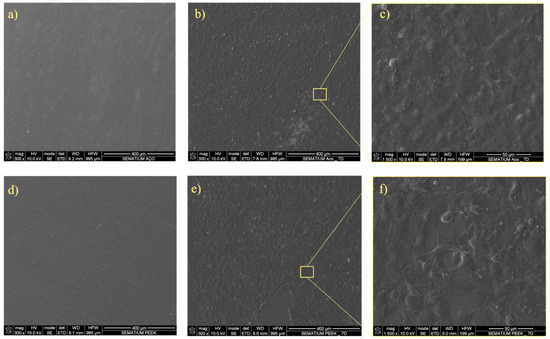

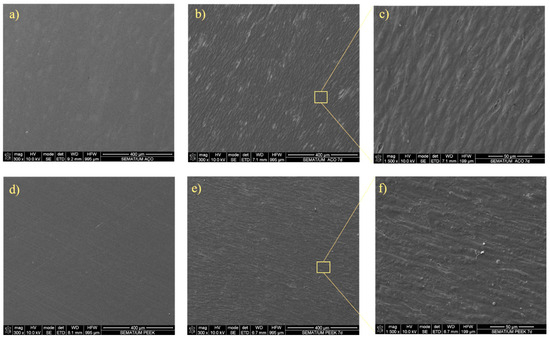

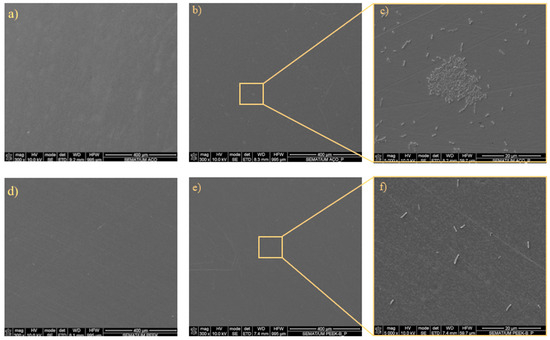

The SEM was used to examine cell–material interactions on the surface, offering high-resolution insights into cellular adhesion and morphological features (Figure 4). In both materials, cells were able to adhere and spread, creating a continuous layer.

Figure 4.

SEM analysis. SEM image of (a) unseeded SS, (b) hFOB seeded on SS at day 7, and (c) hFOB cell detail on seeded SS at day 7; (d) unseeded PEEK; (e) hFOB seeded on PEEK at day 7, and (f) hFOB cell detail on seeded PEEK at day 7.

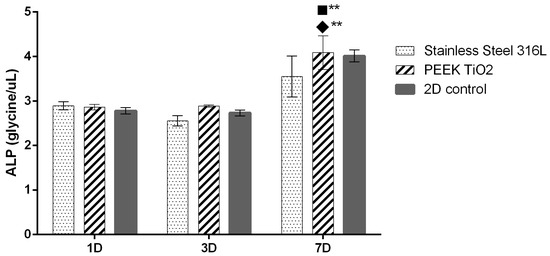

Metabolic activity of HGF cells increased from day 1 to day 7 across all conditions (Figure 5). At day 1, no significant differences were observed between SS and PEEK TiO2, while the 2D control showed higher activity (p < 0.05). By day 3, both materials supported increased cell metabolism, although values remained lower than the 2D control. At day 7, a substantial rise in metabolic activity was detected for both SS and PEEK, with PEEK exhibiting higher activity than SS and approaching the 2D control.

Figure 5.

HGF metabolic activity for up to 7 days of culture. Symbols denote statistically significant differences (**** p < 0.05) in comparison to the following: (◆) SS; (⋆) PEEK. Data is presented as mean ± stdev (total n = 6 per condition).

In addition, the SEM was used to examine cell–material interactions with HGF (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

SEM analysis. SEM image of (a) unseeded SS, (b) HGF seeded on SS at day 7, and (c) HGF cell detail on seeded SS at day 7; (d) unseeded PEEK; (e) HGF seeded on PEEK at day 7, and (f) HGF cell detail on seeded PEEK at day 7.

3.3. Bacterial Adhesion

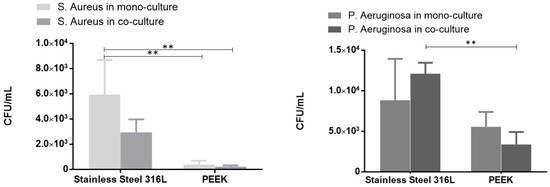

To investigate the antibacterial potential of the tested materials, bacterial adhesion and proliferation were evaluated. Figure 7 shows bacterial adhesion (CFU/mL) on the surfaces of the two tested materials for the two different bacterial species. Overall, PEEK exhibited lower bacterial adhesion compared to SS in both single- and co-culture conditions. In general, adhesion in co-culture was lower than in monoculture, with the exception of P. aeruginosa, which showed increased adhesion on the SS surface when in co-culture.

Figure 7.

Bacterial adhesion (CFU/mL) to specimens PEEK and SS in monoculture and co-culture for the following: (a) S. aureus and (b) P. aeruginosa. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation and (**) to the statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) (total n = 3 per condition).

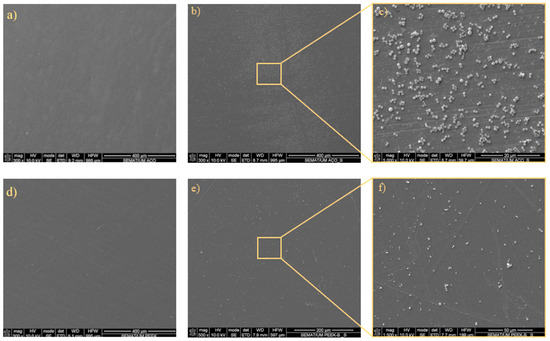

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to visualize both bacterial adhesion and colonization on the material surfaces, providing detailed insights into the morphology and distribution of bacterial cells. Figure 8 shows greater adhesion of S. aureus on the SS surface compared to the PEEK surface, consistent with the CFU count results.

Figure 8.

Representative micrographs of the adhered S. aureus bacteria to SS: (a) unseeded; (b) day 1 bacterial adhesion; and (c) day 1 bacterial adhesion with detail; and the adhesion to PEEK: (d) unseeded; (e) day 1 bacterial adhesion; and (f) day 1 bacterial adhesion with detail.

Figure 9 presents representative micrographs of P. aeruginosa adhesion. Unseeded SS and PEEK surfaces confirm the absence of bacteria. After 1 day, bacterial adhesion is observed on both surfaces, with noticeably more P. aeruginosa attached to SS than to PEEK. Detailed views highlight the morphology and distribution of the adhered bacteria, confirming that P. aeruginosa exhibits greater adhesion to SS compared to PEEK.

Figure 9.

Representative micrographs of the adhered P. aeruginosa bacteria to SS: (a) unseeded; (b) day 1 bacterial adhesion; and (c) day 1 bacterial adhesion with detail; and the adhesion to PEEK: (d) unseeded; (e) day 1 bacterial adhesion; and (f) day 1 bacterial adhesion with detail.

Table 3 presents an ImageJ analysis of the SEM images, quantifying the surface coverage of bacteria on the tested materials. S. aureus showed substantially higher coverage on SS (10.27%) compared to PEEK (1.32%). Similarly, P. aeruginosa adhered more to SS (0.79%) than to PEEK (0.13%), although overall coverage was lower than that of S. aureus. These results indicate that both bacterial species preferentially adhere to SS surfaces, with S. aureus exhibiting the highest surface coverage.

Table 3.

Bacteria surface coverage measurement (%).

4. Discussion

A common issue with currently available materials for dental components, such as implants and pediatric crowns, is their gray metallic color, which negatively impacts aesthetics. To address this challenge, the use of materials like PEEK has gained increasing relevance. In this study, SS (a commonly used dental material) and a PEEK TiO2 composite were evaluated with respect to their surface characteristics and their influence on cell behavior and bacterial adhesion. The success of dental implants mainly depended on the bone–implant interaction and may be influenced by several factors such as surface roughness, wettability, and composition [38], which are also important for fibroblasts.

PEEK in its native state is hydrophobic, a property often linked to reduced tissue bioactivity [39]. Reports from the literature indicate that surface modifications or the addition of filler particles can increase surface energy, enhance hydrophilicity, and create micro/nano-roughness that improves cell anchorage [40,41]. Incorporation of TiO2 particles produces similar effects, enhancing mechanical properties, increasing surface roughness, and reducing contact angle, thereby improving the biological potential of PEEK composites [42,43]. Accordingly, both materials were evaluated for their surface characteristics, with surface roughness (Ra) values presented in Table 1. Although the values obtained are similar, as shown in Table 2, SS exhibited a contact angle of less than 90°, indicating a hydrophilic surface. In contrast, PEEK reinforced with TiO2 displayed a contact angle greater than 90°, indicating a hydrophobic surface. Following surface analysis, cellular behavior was assessed in terms of metabolic activity, cell adhesion, proliferation, and ALP activity. Two cell types were used for this evaluation: human fetal osteoblasts (hFOB), representing hard tissues, and human gingival fibroblasts (HGF), representing soft tissues, both of which are physiologically relevant for dental applications. As shown in Figure 2, the metabolic activity of hFOB cells cultured in a well (2D control) followed a typical pattern, with activity increasing until day 7. Also, the results indicate that both materials, SS and PEEK, supported metabolic cell activity at the time points. At day 1, the metabolic activity was relatively low across all samples, with no statistically significant differences among the materials. This initial stage likely reflects the adaptation of hFOB cells to the material surfaces, during which cells are still adhering and beginning their proliferation cycle [44]. By day 3, both the SS and PEEK samples exhibited a significant increase in metabolic activity relative to day 1. The increased activity on PEEK may be attributed to its surface properties, particularly the reinforcement with TiO2 nanoparticles, which are known to enhance cell adhesion and proliferation [36]. On day 7, metabolic activity continued to increase for all materials, with PEEK showing the highest level of activity. The continued growth observed on PEEK specimens highlights its potential as a viable alternative to SS for applications requiring direct bone interaction. The metabolic activity on SS, although lower than that of PEEK, increased consistently during culture time. Stainless steel has been widely used in orthopedic and dental applications [37]; however, its lower metabolic activity compared to PEEK in this study suggests that PEEK composites could potentially outperform SS.

Considering the final application of these materials, it was important to assess markers such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) to understand how different materials affected the culture of osteoblastic cells, which could later offer crucial insights into bone formation. Analyzing Figure 3, it can be observed that on days 1 and 3, the ALP expression was very similar, and this may be due to deficient cell–cell contact [45]. Nevertheless, at day 7, cells presented a peak of ALP expression, especially when those cultured in PEEK were reinforced with TiO2. It is noteworthy that throughout the entire culture period, the cells expressed ALP, indicating a successful culture. The SEM was employed to assess cell–material interactions at the surface level, providing detailed information on cell adhesion and morphology. As shown in Figure 4, cells were able to adhere and spread to some extent in both materials, forming a layer over the entire surface. Regarding the metabolic activity of HGF cells, it can be observed that, by analyzing Figure 5, they followed a normal pattern of continuous increase. On day 1, PEEK shows metabolic activity comparable to that of SS, indicating a similar initial biocompatibility profile. At day 3, the trend continued with metabolic activity still being higher on the 2D control, though a progressive increase was observed in both PEEK and SS specimens. The sustained growth indicates that HGF cells can adapt and proliferate on both surfaces over time. Notably, the PEEK composite demonstrated slightly higher metabolic activity compared to SS. By day 7, a substantial increase in metabolic activity was observed, especially in PEEK, which outperformed SS, showing statistically significant higher metabolic activity (p < 0.01) compared to SS.

These findings, along with the hFOB metabolic activity and ALP expression, highlight the potential of PEEK composites as a promising alternative to SS for oral applications. The SEM images presented in Figure 6 clearly showed the morphology of fibroblasts adhering and spreading across the surfaces of both materials, further supporting the potential of PEEK composites as a promising alternative to SS for oral applications. One of the major challenges in developing biomedical materials is infection due to biofilm formation. As previously referenced, the evaluation of microbiological response of the materials evaluated was complemented with the bacterial adhesion of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in monoculture and in co-culture. Considering the final applications of the materials evaluated, a 24 h time point was used to assess the initial bacterial adhesion. The results of bacterial adhesion to the specimens’ surface are presented in Figure 7. Figure 8 presents a direct relation between the adhesion of both S. Aureus and P. Aeruginosa and the specimens’ material. Although there is a high variance between results, predominantly for SS, there is a clear pattern of greater bacterial adhesion on SS. A bacterial adhesion mean reduction of 93% and 37% between SS and PEEK was observed with S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, respectively, in monoculture. Bacterial adhesion is strongly influenced by factors such as material composition, surface chemistry, energy, and wettability. In this work, the reduced bacterial adhesion observed on PEEK compared with SS may be attributed to differences in these surfaces’ characteristics, though we did not isolate the contributions of individual factors. While TiO2 is frequently reported to present antibacterial activity [46,47], the role of physical parameters such as roughness and wettability is less clear. Some studies describe a direct relationship between surface roughness and bacterial attachment [48], while others report no consistent trend [49]. In our results, however, surfaces with higher roughness exhibited lower adhesion values (Ra = 0.028 ± 0.010 μm for SS and Ra = 0.083 ± 0.025 μm for PEEK). Wettability has also been inconsistently described in the literature: some authors note a positive association, others a negative one, and some report no significant influence in the case of moderately wettable materials [50,51,52]. The contact angle measurements in our study differed by 11.4֯ (80.1֯ for SS vs. 91.5֯ for PEEK), placing both in the moderate wettability range. Interestingly, within this range, the samples with the higher contact angle showed reduced bacterial adhesion in both species tested.

The assessment of the co-existence and adhesion to materials’ surface of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was also verified. These two bacteria are the most common co-colonization pathogens in most infections and have a direct influence on wound healing, even in the oral cavity. The results obtained followed the same pattern as those obtained in monoculture (Figure 8). A bacterial adhesion mean reduction of 92% and 72% between SS and PEEK was observed in S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, respectively, for the co-culture evaluation. Regarding bacterial adhesion results obtained in co-culture, it was observed that there was a reduction in both specimens tested for S. aureus, compared with the results obtained in monoculture. On the other hand, P. aeruginosa bacterial adhesion results present an increment for stainless steel specimens, while for PEEK, a reduction was observed, when compared with monoculture.

P. aeruginosa and S. aureus are opportunistic species. Even though these species are co-colonizing pathogens, it was verified in other studies that in vitro co-culture of those specimens can challenge the development of each other, as P. aeruginosa can eradicate S. aureus in the first hours of incubation due to extracellular factors secreted by P. aeruginosa [53,54]. The results presented in this work are in accordance with these findings, and, as expected, the activity of P. aeruginosa increased when compared with monoculture. However, P. aeruginosa surface bacterial adhesion decreased in PEEK specimens, although the results do not present a statistical difference. Under our 24 h in vitro co-culture conditions (two species), PEEK TiO2 showed lower early bacterial adhesion than the control. Even considering the study limitations (a single time point of 24 h does not have access to all the temporal biofilm evolution), the demonstrated reduction in bacterial adhesion could translate into improved long-term performance of pediatric crowns and reduced incidence of peri-implantitis in implant applications.

In Figure 9, the SEM images show the adhesion of S. aureus to the two tested specimens: SS (Figure 9a–c) and PEEK (Figure 9d–f). The SS samples exhibited a higher number of bacteria, corroborating the CFU/mL results presented in Figure 7. Similarly, the SEM images of P. aeruginosa adhesion (Figure 9, right) revealed a predominance of bacteria on SS compared with PEEK. In both cases, the bacteria formed large clusters on SS surfaces, whereas on PEEK, they appeared more sparsely distributed, forming small, scattered aggregates. Comparable findings were reported by Songmei et al. [55] in SS polished surfaces with nanoscale roughness. The percentage of surface area covered by bacteria presented a relative reduction of 87% and 83% between SS and PEEK for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, respectively. These results corroborate the bacterial adhesion reduction observed in the experiments presented before; however, considering that the measurements were performed in single technical replicates, the results should be considered as strictly descriptive.

These findings highlight the potential for PEEK TiO2 to be a viable option for crowns in pediatric dentistry, in line with previous reports [11,24]. Such properties are particularly relevant in pediatric dentistry, where aesthetics, infection control, and tissue compatibility are critical to long-term treatment success. Nevertheless, PEEK dental prostheses are not yet regarded as a definitive clinical alternative, as recent systematic reviews have highlighted mechanical limitations that may compromise long-term performance.

5. Conclusions

In this study, SS and PEEK TiO2 nanoparticles were characterized in terms of surface properties, cytocompatibility, and bacterial adhesion. Both materials proved to be non-cytotoxic and supported cell growth. However, PEEK demonstrated superior biological performance, as demonstrated by ALP activity increasing at day 7 relative to days 1–3 (p < 0.01), with PEEK TiO2 showing the highest mean values. In HGF, metabolic activity at day 7 was higher on PEEK TiO2 than on SS (p < 0.01). PEEK TiO2 also showed lower bacterial adhesion than SS in mono- and co-culture for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. In co-culture, mean adhesion on PEEK TiO2 was lower (−92% for S. aureus; −72% for P. aeruginosa), although the P. aeruginosa difference did not reach statistical significance.

Overall, these findings indicate that PEEK TiO2 composites may represent an alternative to SS for dental applications, including pediatric crowns and bone-contacting components. Nonetheless, as this was a short-term in vitro study, the results do not capture the full complexity of the biological response that occurs in vivo. Therefore, additional studies, including in vitro co-culture models with multiple bacterial species at different time points and in vivo studies, are required to evaluate the long-term performance and microbial resistance of PEEK TiO2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S.; methodology, H.P. and F.R.; validation, H.P., F.R., A.A., and J.P.; formal analysis, H.P., F.R., A.A., and J.P.; investigation, H.P., F.R., A.A., and J.P.; resources, F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.P., F.R., and J.P.; writing—review and editing, H.P., F.R., F.S., and J.P.; supervision, F.S.; funding acquisition, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) national funds, under the national support to the R&D unit’s grant, through the reference project UIDB/04436/2020 and UIDP/04436/2020. Also, H. Pereira acknowledges FCT for her PhD scholarship 2020.07257.BD (https://doi.org/10.54499/2020.07257.BD). J. Pinto acknowledges FCT for his individual grant 2021.09001.BD and F. Rodrigues also acknowledges FCT 2023.05138.BDANA (https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.05138.BDANA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marin, E. History of dental biomaterials: Biocompatibility, durability and still open challenges. Heritage Sci. 2023, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Imai, H.; Kawai, T.; Yoneyama, T. Application of titanium and titanium alloys to fixed dental prostheses. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2019, 63, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.T.; Devi, S.P.; Krithika, C.; Raghavan, R.N. Review of metallic biomaterials in dental applications. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12 (Suppl. 1), S14–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.M.; Venkatesan, S. A review on application of biomaterials for medical and dental implants. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2023, 237, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbole, N.; Yadav, S.; Ramachandran, M.; Belemkar, S. A review on surface treatment of stainless steel orthopedic implants. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2016, 36, 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wills, D.J.; Neville-Towle, J.; Podadera, J.; Johnson, K.A. Computed tomographic evaluation of the accuracy of minimally invasive sacroiliac screw fixation in cats. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2022, 35, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduok, U. Microbiologically induced intergranular corrosion of 316L stainless steel dental material in saliva. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 313, 128799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaipattanawan, N.; Chompu-Inwai, P.; Nirunsittirat, A.; Phinyo, P.; Manmontri, C. Longevity of stainless steel crowns as interim restorations on young permanent first molars that have undergone vital pulp therapy treatment in children and factors associated with their treatment failure: A retrospective study of up to 8.5 years. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Singh, A.; Jackson, M.J.; Coelho, R.T.; Prakash, D.; Charalambous, C.P.; Ahmed, W.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Lawrence, A.A. A comprehensive review on metallic implant biomaterials and their subtractive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 1473–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitalla, A.; Müller, W.-D. PEEK dental implants: A review of the literature. J. Oral Implant. 2013, 39, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arieira, A.; Madeira, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Silva, F. Tribological Behavior of TiO2 PEEK Composite and Stainless Steel for Pediatric Crowns. Materials 2023, 16, 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, C.; Oates, T.W.; Weir, M.D.; Wu, J.; Xu, H.H.K. Review on development and dental applications of polyetheretherketone-based biomaterials and restorations. Materials 2021, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adali, U.; Sütel, M.; Yassine, J.; Mao, Z.; Müller, W.-D.; Schwitalla, A.D. Influence of sandblasting and bonding on the shear bond strength between differently pigmented polyetheretherketone (PEEK) and veneering composite after artificial aging. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-F.; Lee, I.-T.; Wu, S.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Mine, Y.; Peng, T.-Y.; Kok, S.-H. Effects of handheld nonthermal plasma on the biological responses, mineralization, and inflammatory reactions of polyaryletherketone implant materials. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, S.; Shi, Y.; Chen, M.; Lan, Y.; Hu, L.; Yang, X. Overcoming biological inertness: Multifaceted strategies to optimize PEEK bioactivity for interdisciplinary clinical applications. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 3106–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaguer-Flores, A.; Ximénez-Fyvie, L.A.; Rodil, S.E. Oral bacterial adhesion on amorphous carbon and titanium films: Effect of surface roughness and culture media. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 92, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikogianni, M.; Missirlis, Y. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterials and of techniques used in estimating bacteria-material interactions. Eur. Cell Mater. 2004, 8, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W. Biofilm theory can guide the treatment of device-related orthopaedic infections. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 437, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontology 2000 2005, 38, 135–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paster, B.J.; Boches, S.K.; Galvin, J.L.; Ericson, R.E.; Lau, C.N.; Levanos, V.A.; Sahasrabudhe, A.; Dewhirst, F.E. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 3770–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, H.; Bigger, C.M.; Valentin, J.; Abt, D.; Qin, X.; Eberl, L.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Ren, Q. Bacterial adhesion on soft materials: Passive physicochemical interactions or active bacterial mechanosensing? Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1801323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbourne, A.; Chapman, J.; Gelmi, A.; Cozzolino, D.; Crawford, R.J.; Truong, V.K. Bacterial-nanostructure interactions: The role of cell elasticity and adhesion forces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 546, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Allan, E.; van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J. Emergent heterogeneous microenvironments in biofilms: Substratum surface heterogeneity and bacterial adhesion force-sensing. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.-J.; Chen, W.-C.; Srimaneepong, V.; Chen, C.-S.; Huang, C.-H.; Lin, H.-C.; Tung, O.-H.; Huang, H.-H. Fracture Characteristics of Commercial PEEK Dental Crowns: Combining the Effects of Aging Time and TiO2 Content. Polymers 2023, 15, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragaglia, M.; Cherubini, V.; Nanni, F. PEEK-TiO2 composites with enhanced UV resistance. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 199, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Chu, M.; Jiang, J.; Yin, T.; Li, J.; Gao, S. Polyetheretherketone/Nano-Ag-TiO2 composite with mechanical properties and antibacterial activity. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, N.A.A.; Ridha, H.B.M. Investigation of tribological and mechanical properties of PEEK-TiO2 composites. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (ICMAE), Prague, Czech Republic, 22–25 July 2017; pp. 330–334. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A.V.M.; Thanigachalam, M. Mechanical performances, in-vitro antibacterial study and bone stress prediction of ceramic particulates filled polyether ether ketone nanocomposites for medical applications. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, A.; Diez, M.S.; Rojo, D.; Bargiela, R.; Ciordia, S.; Zapico, I.; Albar, J.P.; Barbas, C.; dos Santos, V.A.P.M.; Fernández-García, M.; et al. Understanding the antimicrobial mechanism of TiO2-based nanocomposite films in a pathogenic bacterium. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.; Quinn, J.P.; Bradford, P.A.; Goering, R.V.; Nathan, C.; Bush, K.; Weinstein, R.A. Multiple antibiotic–resistant Klebsiella and Escherichia coli in nursing homes. JAMA 1999, 281, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokare, A.; Sanap, A.; Pai, M.; Sabharwal, S.; Athawale, A.A. Antibacterial activities of Nd doped and Ag coated TiO2 nanoparticles under solar light irradiation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 102, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Díez-Vicente, A.L. Nano-TiO2 reinforced PEEK/PEI blends as biomaterials for load-bearing implant applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5561–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, M.A.; Rodríguez-Páez, J.E. Facile synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles of different crystalline phases and evaluation of their antibacterial effect under dark conditions against E. coli. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrada, M.L.; Serrano, C.; Sánchez-Chaves, M.; Fernández-García, M.; Fernández-Martín, F.; de Andres, A.; Rioboo, R.J.J.; Kubacka, A.; Ferrer, M.; Fernández-García, M. Self-sterilized EVOH-TiO2 nanocomposites: Interface effects on biocidal properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, A.; Serrano, C.; Ferrer, M.; Lünsdorf, H.; Bielecki, P.; Cerrada, M.L.; Fernández-García, M.; Fernández-García, M. High-performance dual-action polymer−TiO2 nanocomposite films via melting processing. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 2529–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, T.; Padrão, J.; da Silva, M.R.; Pinto, P.; Madeira, S.; Vaz, P.; Zille, A.; Silva, F. Bacteria co-culture adhesion on different texturized zirconia surfaces. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 123, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.M.; Al-Badi, E.; Withycombe, C.; Jones, P.M.; Purdy, K.J.; Maddocks, S.E. Interaction between Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is beneficial for colonisation and pathogenicity in a mixed biofilm. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, fty003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhy, B.; Priyadarshini, P.; Sen, A.K. Effect of surface energy and roughness on cell adhesion and growth—Facile surface modification for enhanced cell culture. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 15467–15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarso; Tsuchiya, A.; Toita, R.; Tsuru, K.; Ishikawa, K. Enhanced osseointegration capability of poly(ether ether ketone) via combined phosphate and calcium surface-functionalization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xiong, D.; Liu, Y. Improving surface wettability and lubrication of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) by combining with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) hydrogel. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 82, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesel, A.; Zaplotnik, R.; Primc, G.; Mozetič, M. Kinetics of surface wettability of aromatic polymers (PET, PS, PEEK, and PPS) upon treatment with neutral oxygen atoms from non-equilibrium oxygen plasma. Polymers 2024, 16, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea Mifsud, M.; Sachan, A.; Narayan, R.J.; Di-Silvio, L.; Coward, T. Fabrication and Characterization of a Porous TiO2-Modified PEEK Scaffold with Enhanced Flexural Compliance for Bone Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Paliwal, J.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, N.; Meena, K.K.; Singhal, P. Influence of PEEK surface modification with titanium for improving osseointegration: An in vitro study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lim, J.Y.; Donahue, H.J.; Dhurjati, R.; Mastro, A.M.; Vogler, E.A. Influence of substratum surface chemistry/energy and topography on the human fetal osteoblastic cell line hFOB 1.19: Phenotypic and genotypic responses observed in vitro. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 4535–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.-T.; Lin, D.-J.; Huang, S.; Lin, H.-T.; Chang, W.H. Osteogenic differentiation is synergistically influenced by osteoinductive treatment and direct cell–cell contact between murine osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells. Int. Orthop. 2012, 36, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochford, E.; Poulsson, A.; Varela, J.S.; Lezuo, P.; Richards, R.; Moriarty, T. Bacterial adhesion to orthopaedic implant materials and a novel oxygen plasma modified PEEK surface. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 113, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Hays, M.P.; Hardwidge, P.R.; Kim, J. Surface characteristics influencing bacterial adhesion to polymeric substrates. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14254–14261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, M.; Dogša, I.; Stošicki, T.; Stopar, D.; Kalin, M.; Kobe, S.; Novak, S. The influence of surface modification on bacterial adhesion to titanium-based substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.; Boshkovikj, V.; Fluke, C.; Truong, V.; Hasan, J.; Baulin, V.; Lapovok, R.; Estrin, Y.; Crawford, R.; Ivanova, E. Bacterial attachment on sub-nanometrically smooth titanium substrata. Biofouling 2013, 29, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Yin, X.; Iglauer, S. A review on clay wettability: From experimental investigations to molecular dynamics simulations. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 285, 102266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amshawee, S.; Yunus, M.Y.B.M.; Lynam, J.G.; Lee, W.H.; Dai, F.; Dakhil, I.H. Roughness and wettability of biofilm carriers: A systematic review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Guo, Z. Bioinspired surfaces with wettability: Biomolecule adhesion behaviors. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 1502–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, C.F.; Christensen, A.-M.J.; Bojer, M.S.; Høiby, N.; Ingmer, H.; Jelsbak, L. Staphylococcus aureus alters growth activity, autolysis, and antibiotic tolerance in a human host-adapted Pseudomonas aeruginosa lineage. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 3903–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, D.B.Y.; Sircombe, K.J.; Pletzer, D. Friends or enemies? The complicated relationship between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2021, 116, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Altenried, S.; Zogg, A.; Zuber, F.; Maniura-Weber, K.; Ren, Q. Role of the surface nanoscale roughness of stainless steel on bacterial adhesion and microcolony formation. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 6456–6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).