Featured Application

This pilot study provides preliminary evidence that integrating chemical (TMVOC) and biological (ATP) indicators can enhance post-disaster indoor air quality assessments. For environmental engineering, the findings suggest potential applications in refining building assessment tools and moisture diagnostics to better identify hidden microbial contamination. For environmental health, the approach offers early insight into how combined TMVOC and ATP measurements may complement visual inspection methods in flood-damaged homes. Although based on a small sample of residential homes affected by Hurricane Ian, these results demonstrate a methodological framework that could be expanded in larger studies and aid future disaster response strategies.

Abstract

Flooding from hurricanes creates damp indoor environments that support mold growth and microbial contamination, posing long-term health risks for occupants. This pilot study evaluated TMVOCs, microbial activity, and environmental conditions in 13 Hurricane Ian-affected residences across multiple flood-affected neighborhoods. Air samples were collected using sorbent tubes and analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, while microbial activity on surfaces was assessed via ATP bioluminescence. Visible mold and dampness were documented with the CDC/NIOSH Dampness and Mold Assessment Tool, and environmental measurements included temperature, relative humidity, and surface as well as hidden moisture. Median (IQR) TMVOC concentrations were 12 (8) µg/m3, with 61% of homes exceeding the 10 µg/m3 benchmark set by previous researchers despite minimal visible contamination. Spearman’s correlation revealed significant negative relationships between odor and surface microbial activity (ρ = −0.569, p < 0.05), indicating that organic debris may play a more crucial role in microbial activity within the tested homes, and that odors might originate from hidden microbes instead of surface microbial growth. Our study emphasizes the necessity of utilizing both chemical (TMVOC) and biological (ATP) indicators to evaluate poor air quality caused by molds in flood-affected homes, serving as a supplement to routine visible mold assessments.

1. Introduction

Flooding is one of the most frequent and destructive natural disasters globally, leading to significant structural damage to homes and posing major public health challenges. Post-flood environments are characterized by high levels of dampness and humidity, which provide favorable conditions for microbial proliferation, including molds, bacteria, and other opportunistic pathogens [1]. Excess moisture in building materials—such as wood, drywall, and insulation—not only compromises structural integrity but also fosters hidden microbial growth behind walls, under flooring, and within ceilings [2]. Importantly, microbial contamination of the indoor environment is a well-documented contributor to building-related illnesses, including respiratory conditions, asthma exacerbation, allergic sensitization, and sick building syndrome [3,4]. Floodwater also introduces organic matter, sewage, and chemical contaminants, further compounding microbial risks. Contaminated floodwaters can seed affected homes with harmful bacteria and fungi, which persist long after visible water is removed [5]. Several previous studies, including those conducted by the current authors [6,7,8], have shown increased mold contamination and enrichment of some health-hazardous mold genera in flood-affected homes in other U.S. states. Even when remediation is attempted, hidden moisture can sustain microbial activity for months or years, making accurate detection and long-term monitoring crucial to safeguarding occupant health [9]. Mold growth in damp buildings has been widely studied as a primary indicator of poor indoor air quality (IAQ). Beyond spores and fragments, molds release metabolic byproducts into the air known as mold-specific volatile organic compounds (MVOCs), such as alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, and hydrocarbons. Common examples include 1-octen-3-ol, 2-heptanone, and 3-methylfuran, which have been associated with musty odors and adverse health effects [10]. Exposure to MVOCs has been linked with irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, fatigue, headaches, and respiratory symptoms consistent with sick building syndrome [11,12]. MVOCs can be detected even in the absence of visible mold growth, providing a valuable tool for identifying hidden microbial contamination [13,14]. Thus, measurement of TMVOC levels offers an indirect but sensitive approach for characterizing microbial contamination in flood-impacted homes, which has been relatively less explored.

In addition to airborne contaminants, microbial activity can persist on building surfaces. High-touch areas such as floors, tables, and door handles may serve as reservoirs of microbial biomass, increasing potential exposure risk for occupants [15]. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence assays are widely used in environmental health to quantify microbial activity on surfaces by detecting ATP from living organisms and organic debris [16]. Though not species-specific, ATP-based measurements provide a rapid, standardized, and quantitative assessment of surface contamination levels in indoor settings. Flood-damaged homes are particularly prone to microbial colonization of surfaces due to residual dampness. By combining ATP bioluminescence with environmental measures such as relative humidity, temperature, and hidden moisture levels, researchers can better understand the ecological niches that sustain microbial growth post-disaster [17].

Hurricane Ian, which struck Florida and surrounding coastal areas in September 2022, was one of the most destructive U.S. hurricanes in recent history. The storm surge and heavy rainfall caused extensive flooding, displacing residents and damaging thousands of homes. Long after the floodwater receded, affected homes faced persistent dampness, odor problems, and microbial contamination that threatened long-term habitability and health of residents [18]. Understanding the environmental conditions and microbial burdens in post-Ian homes is crucial for informing remediation guidelines, risk communication, and preventive health measures. While visible mold or other microbial growth is often used as the primary marker of contamination, its absence does not necessarily preclude ongoing microbial activity. However, prior large-scale assessments after Hurricane Katrina and Sandy primarily relied on visual inspection and spore counts [5,6]. In this pilot study, we hypothesized that flooding and persistent dampness from Hurricane Ian created transient indoor microclimates in affected homes, fostering elevated microbial activity, mold growth, and MVOC emissions, which occurred even without visible contamination. We integrated measurement of TMVOC levels and ATP assays to quantify microbial activity on surfaces, offering a multi-method framework to detect hidden microbial activity. The primary aim was to measure TMVOC in the air, microbial activity on indoor surfaces, odor levels, and environmental parameters (relative humidity, temperature, and moisture content). Secondary objectives included measurement of contamination levels across different surfaces and assessment of visible mold using the standardized CDC/NIOSH Dampness and Mold Assessment Tool [19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional field study was conducted to evaluate post-flood indoor environmental conditions in residential buildings affected by Hurricane Ian. The hurricane struck the southwestern coast of Florida in September 2022, producing storm surges and extensive flooding in low-lying coastal communities. Sampling was conducted in November 2023, corresponding to approximately one year after flooding. This period was selected to allow initial recovery efforts, such as pumping out floodwater and superficial renovations to be completed while still permitting the detection of residual dampness and microbial activity.

2.2. Selection of Homes

The original study design aimed to include 40 homes, 20 flood-affected and 20 non-flooded, to serve as a control group. However, due to funding constraints and challenges in obtaining homeowner participation, 17 single-family residential homes from flood-affected areas could ultimately be recruited, and 13 of them met the selection criteria for inclusion in the study. Non-flooded homes were not included in the final sample.

All selected homes were located within hurricane-affected zones of Lee and Collier counties, Florida, near the city of Fort Myers. Flooded homes were identified through collaboration with local public health agencies and community organizations engaged in post-disaster recovery. Inclusion criteria were: (1) documented flooding with water levels of ≥3 feet during Hurricane Ian; (2) occupancy or partial occupancy at the time of sampling; and (3) homeowner consent for environmental sampling. Exclusion criteria included: (1) homes that had undergone major reconstruction (e.g., demolition and rebuilding of entire structural elements), as these would not reflect residual contamination; and (2) properties uninhabited or inaccessible due to safety concerns. Initial flood water depths for included homes were reported by homeowners and verified by visual water lines when available, ranging between 3 and 10 feet.

2.3. Air Sampling and VOC Analysis

Air sampling was performed using glass sorbent tubes, following a modified U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) TO-17 protocol and ISO 16000-6 standards [20,21]. The EPA TO-17 protocol involves actively pumping air onto sorbent tubes to collect VOCs, which are then analyzed by thermal desorption followed by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC/MS) for identification and quantification. Sample analysis was conducted by an AIHA-accredited analytical lab that used GC-MS and also combined fluorescence spectroscopy with GC-MS for formaldehyde-related compounds; this approach allows the rapid identification and quantification of many VOCs, including mold-specific MVOCs, from just a single air sample. A calibrated low-flow pump (Prism Analytical Technologies, Mt. Pleasant, MI, USA) was used to collect about 18 L of air at a flow rate of 200 mL/min +/− 5 mL/min over 90 min. To ensure accuracy and consistency, all instruments—including the pump and the ppbRAE 3000+ monitor (Honeywell, Charlotte, NC, USA)—were calibrated before and after sampling using manufacturer-recommended standards. Following collection, tubes were sealed, labeled, and transported to the laboratory. Samples were analyzed within a week using GC/MS and fluorescence spectroscopy. Compounds were desorbed via thermal desorption, separated on a capillary column, and identified by retention time and mass spectra against the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library. Total mold-specific VOCs (TMVOC) were quantified by summing concentrations of 21 characteristic compounds, including methyl ethyl ketone, 1-pentanol, 2-heptanone, 2-pentyl furan, and 2-ethyl-1-hexanol, as identified in prior studies of mold metabolism [22,23]. Concentrations were expressed as ng/L of air. In addition to TMVOC, total VOCs or TVOCs were also assessed in air samples collected by sorbent tubes, as well as in real time by the ppbRAE monitor, which uses a 3rd generation photoionization detector (PID) and built-in correction factors for more than 200 VOC compounds and is one of the most advanced VOC monitors for parts-per-billion (ppb) detection. Due to time, funding limitations, and restricted sampling materials, TMVOC, microbial activity, and odor samples were all collected from the same room in each home, primarily the main living area. Only one sample was collected for each home for VOCs, and multiple samples were collected for ATPs and other test variables. This approach was chosen because these rooms had been affected by floodwater at heights of 1.2–1.5 m, approximating the human breathing zone. However, this design does not capture spatial variation across different rooms or levels of the home, and results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind.

2.4. Mold Assessment

Visual mold assessments were conducted using the Dampness and Mold Assessment Tool (DMAT) developed by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which provides a standardized method for rating the presence of dampness and visible mold across building surfaces [19]. The DMAT uses a semi-quantitative approach to score the level of dampness and mold-related damage (mold odor, water damage/stains, visible mold, and wetness/dampness) by intensity or size for each of the room components (ceiling, walls, windows, floor, furnishings, ventilation system, pipes, and supplies and materials). Trained research assistants systematically inspected surfaces for discoloration, musty odors, and visible fungal growth, assigning categorical scores ranging from none (zero signs of mold) to extensive. To ensure accurate documentation, photographs were taken only of areas with visible mold contamination, and information on prior remediation efforts (e.g., repainting, replacing drywall, or dehumidifier use) was collected. These mold assessment data were then integrated with TMVOC and microbial activity measurements to contextualize findings.

2.5. Surface Microbial Activity Assessment

Surface microbial contamination was assessed using ATP bioluminescence assays, a widely accepted method for rapid quantification of biological activity on environmental surfaces [16,17]. A Hygiena SystemSURE Plus luminometer with UltraSnap swabs (Hygiena LLC, Camarillo, CA, USA) was employed. Sampling locations included four commonly contacted or moisture-prone surfaces: Floors (living area, near entry points), Door handles (frequently touched surfaces), Tables (horizontal surfaces), and Interior walls. Swabbed surface areas were not uniform because of variation in specific spores and sample locations; final readings were converted to RLU (Relative Light Units) per cm2. Our data can be converted to RLU per 10 cm2 to align with other studies that swabbed a 10 cm2 area, as suggested by the manufacturer’s protocol [16,17]. Swabs were immediately inserted into the tube and activated to release luciferase/luciferin reagent by shaking and then inserted into the luminometer, and RLUs were recorded as a proxy for microbial activity. Higher RLU values indicate greater microbial load. At least three measurements were obtained for quality assurance, and mean values were used for data analysis. Because ATP detects both viable microorganisms and non-microbial organic debris, results were interpreted as relative indices of contamination rather than absolute microbial counts. It should be noted that ATP assays detect both microbial and non-microbial organic material (e.g., food residues, skin cells). Therefore, elevated RLU values should be interpreted as general biological contamination rather than mold-specific activity, unless confirmed by complementary culture or molecular methods [16].

2.6. Environmental Measurements

Indoor environmental conditions were monitored concurrently with air and surface sampling. The Mastech MS6300—a portable multifunctional environmental multimeter—was used for monitoring temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), illuminance (LUX), and wind speed (m/s). Hidden moisture within building materials was evaluated using a pinless FLIR MR160 Thermal Imaging Moisture Meter (FLIR Systems, Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA) with Infrared Guided Measurement (IGM™), which is a handheld diagnostic tool that combines a built-in thermal imager with a pinless moisture meter and an external pin probe for precise moisture detection. It features an 80 × 60 thermal camera that uses IGM™ technology to quickly identify potential moisture problem areas behind walls, ceilings, and floors. The Kanomax OMX-ADM Handheld Odor Monitor (Kanomax USA, Inc., Andover, NJ, USA) was used for odor assessment, which is a portable gas detector designed to quantify odor strength in indoor and occupational environments. It employs semiconductor gas sensor technology that responds to a broad range of volatile gases, including ammonia-type compounds, and displays results in a dimensionless “odor strength value” ranging from 0 to 999. These values are relative units rather than absolute concentrations (e.g., ppm), meaning the instrument does not identify specific gases or provide chemical quantification. Instead, the user establishes a baseline reference for what constitutes weak, moderate, or strong odor in the study setting. Because individual human sensitivity varies and some gases are odorless, the numerical reading from the OMX-ADM may not always correspond to human perception. Nonetheless, the device provides a reproducible index of odor intensity that is particularly useful for comparative monitoring of odor fluctuations in real time.

2.7. Data Analysis

All field and laboratory-analyzed data were recorded on standardized forms and entered into a secure database. Since a normal distribution of data could not be assumed for variables, descriptive statistics for TMVOC, total VOC concentrations, surface microbial activity (RLUs), moisture levels, temperature, and humidity were displayed using median (interquartile range). Relationships between environmental parameters (moisture, humidity) and microbial activity were evaluated using Spearman correlation coefficients. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Visible Mold Growth and Signs of Dampness on the Surfaces as Determined by the CDC/NIOSH DMAT

The CDC/NIOSH Dampness and Mold Assessment Tool (DMAT) provides a semi-quantitative scoring system for evaluating visible mold, water stains, musty odors, and signs of dampness across structural components [19]. In our study, DMAT scores were predominantly zero for most surfaces and homes (Table 1), with only a few cases reporting minor water stains or residual musty odors (notably Homes 4 and 11). This largely negative finding is important because it suggests that visual inspection alone substantially underestimates microbial risk, particularly when hidden moisture and MVOC levels remain elevated.

Table 1.

Visible Mold Data collected by the CDC/NIOSH Dampness & Mold Assessment Tool (0 = No visible mold, 1 = mild mold growth, 2 = Moderate mold growth, 3 = Strong mold growth).

Previous studies in post-Katrina homes [5] and long-term surveys of U.S. residences [9] similarly found discrepancies between visible mold and hidden contamination. In New Orleans, for instance, many homes that appeared remediated still harbored measurable fungal burdens months after flooding. Our findings build on prior studies by showing preliminary evidence that 61% of homes exceeded the 10 µg/m3 TMVOC threshold (explained below in Section 3.2) despite minimal visible mold. While mold could be observed in damp areas in a few homes, most homes were free from visible mold growth on walls, floors, and ceilings.

3.2. Levels of TMVOCs and TVOCs in Flood-Affected Homes

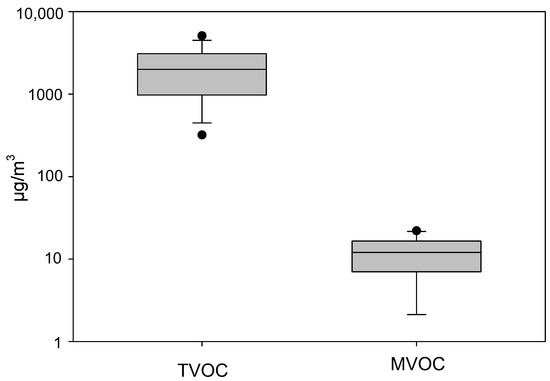

The median (IQR) concentration of TMVOCs across the 13 sampled homes was 12 (8) µg/m3, providing preliminary evidence that 61% of homes exceeded 10 µg/m3 (Figure 1). In large-scale assessments of residential buildings, total mold-specific VOCs (TMVOC) have been suggested as indicators of microbial activity, with concentrations exceeding 10 µg/m3 of air often considered suggestive of active growth [10]. In addition to producing allergenic spores and toxic secondary metabolites, many mold species release microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs), which significantly influence indoor air quality, ecological interactions, and human health [10]. Because individual mVOCs vary greatly in chemistry and toxicological impact, there are no threshold limit values (TLVs) or permissible exposure limits (PELs). To provide a practical benchmark, Korpi and colleagues reviewed data from multiple indoor air studies and proposed 10 µg/m3 of total mold-specific VOCs (TMVOCs) as a reference point. Their reasoning was that TMVOC levels in clean, dry buildings are generally very low or undetectable, while homes with hidden fungal growth often show elevated concentrations. Thus, values above 10 µg/m3 serve as a red flag for potential hidden contamination, even in the absence of visible mold. This reference threshold is particularly relevant to our study, as it offers a comparative standard for interpreting TMVOC concentrations in the examined Hurricane Ian-affected homes and strengthens the connection between environmental measurements and potential health risks. It should be noted that the 10 µg/m3 threshold is research-based rather than a regulatory threshold; it provides a useful benchmark for identifying likely microbial activity but does not represent an enforceable health-based standard [10]. While these results provide preliminary insight into post-flood IAQ, it is important to note that our pilot study did not have sufficient time, funding, or sample size to account for additional confounding factors, such as VOC emissions from building materials, cleaning chemicals, or outdoor air infiltration. Addressing these limitations will be essential in future larger-scale studies to better isolate the sources of TMVOCs and strengthen causal interpretation. Previous investigations of non-flooded, mold-free U.S. and European residences have reported lower levels, typically ranging from 2 to 8 µg/m3 [24,25]. These baseline values represent clean, non-damp homes, further underscoring that the elevated TMVOC concentrations observed in our study reflect residual microbial activity and hidden moisture in post-flood environments. Importantly, Schleibinger et al. [25] also showed that moldy or moisture-damaged homes had substantially higher MVOC concentrations, often well above 20 µg/m3. Thus, our findings place the sampled Hurricane Ian homes in an intermediate contamination category—higher than clean, non-problem homes, but generally lower than the most heavily mold-contaminated dwellings reported in previous studies. A large dataset from the Enthalpy/IAQ Home Survey, which analyzed more than 45,000 U.S. home air samples, reported an average TMVOC concentration of approximately 10 µg/m3. That report also defined interpretive bands: Minimal (<8 µg/m3), Moderate (8–30 µg/m3), Elevated (30–80 µg/m3), High (80–150 µg/m3), and Severe (>150 µg/m3). About 20% of the surveyed homes fell near 20 µg/m3. In comparison, 61% of the Hurricane Ian–affected homes in our study exceeded 10 µg/m3 and were therefore classified in the Moderate category. These results suggest preliminary evidence of elevated microbial activity in more than half of the sampled homes, likely related to hidden fungal growth sustained by residual dampness—possibly hidden behind walls or under the floors. This may be associated with an increased risk of respiratory irritation, allergic sensitization, and other adverse health effects, particularly in susceptible individuals. Our findings are particularly noteworthy because, until now, no studies have systematically combined the analysis of 21 specific mold volatile organic compounds found in flood-affected homes as performed in our study. Many laboratory studies have been performed to determine which chemical compounds are emitted by molds under various conditions [10,22,23]. Depending on the specific data needs, these studies provide the basis for selecting target analytes. 21 compounds were selected considering the mold growth conditions expected in US homes and combined to calculate TMVOCs. This approach not only provides a comprehensive dataset of TMVOCs but also highlights the significant health and safety implications for communities impacted by flooding. Additionally, these data will benefit environmental health researchers and microbiologists who seek to understand the complex interactions between mold growth and environmental conditions following flooding events.

Figure 1.

Box plots showing the TMVOC and TVOC levels across sampled flood-affected homes. The lower and upper boundaries of the box specify the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The line within the box indicates the median, and the whiskers above and below the box indicate the 95th and 5th percentiles, respectively.

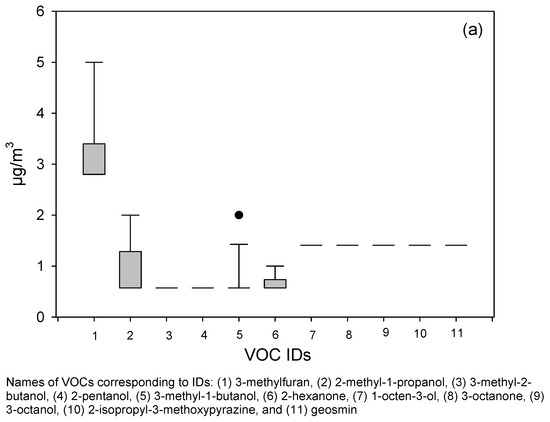

Although air samples were analyzed for a total of 21 microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOCs), to maintain consistency with established literature [10,22,23], we highlighted 11 “priority” MVOCs that have been most consistently reported in damp indoor environments. These included 3-methylfuran, 2-methyl-1-propanol, 3-methyl-2-butanol, 2-pentanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-hexanone, 1-octen-3-ol, 3-octanone, 3-octanol, 2-isopropyl-3-methoxypyrazine, and geosmin. This set overlaps with 11 of the 15 MVOCs identified by Korpi et al. [10] as the core group most relevant to microbial metabolism and health effects, ensuring comparability with previous research. The remaining 10 MVOCs were also reported because they are produced by common building-associated fungi and have been documented in indoor air studies. Monitoring a broader set of 21 MVOCs allowed us to capture the cumulative profile of microbial metabolism rather than limiting interpretation to a narrow subset. This inclusive approach provides a more complete picture of post-flood microbial activity and strengthens comparability with diverse prior studies that have used different VOC panels (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Box plots show (a) the distribution of data for 11 priority MVOCs (as reported by previous researchers) and (b) the other 10 MVOCs in sampled flood-affected homes. Altogether, 21 different MVOCs were analyzed. The lower and upper boundaries of the box specify the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The line within the box indicates the median, and the whiskers above and below the box indicate the 95th and 5th percentiles, respectively.

By comparison, a CDC/NIOSH study of 23 non-problem U.S. homes [26] reported the highest average concentrations for several individual MVOCs (e.g., 1-octen-3-ol, 2-octen-1-ol, 3-octenone, 2-heptanone, 1-butanol) in the 11–37 µg/m3 range. Our summed TMVOC average of 11.84 µg/m3 falls at the lower end of that distribution, reflecting cumulative burden rather than peak values of single compounds. This suggests that while individual MVOCs may reach higher levels even in clean homes, the persistence of multiple compounds at moderate concentrations in our post-flood homes likely reflects sustained microbial activity and hidden contamination.

Concerning the TVOC data, we found that the median (IQR) concentration across the 13 homes was 2000 (1500) µg/m3 (Figure 1), whereas the median (IQR)concentration of TVOC measured by the ppbRAE 3000+ monitor was 54 (518) ppm. Compared with the literature, the TVOC levels measured by sorbent tubes were higher than those typically reported in non-flooded U.S. residences (commonly <150 µg/m3) but fall within the range documented in damp or mold-contaminated homes [24,25]. Our findings, therefore, indicate that post-flood environments may sustain persistently elevated VOC burdens, consistent with microbial metabolism as well as off-gassing from damaged building materials.

The odor levels with respect to clean, non-flooded homes in the study area were assessed. Odor strengths in the investigated flooded homes were 13 (73) (median and IQR).

Correlation analysis revealed several significant associations between environmental parameters and TVOC, highlighting complex interactions between dampness and chemical emissions. TVOC was negatively correlated with surface moisture (ρ = −0.711, p < 0.01) and was positively correlated with odor (ρ = 0.721, p < 0.01), indicating that some non-moldy VOCs might play an important role in odor generation.

To place our findings in a broader microbiological context, we compared the MVOCs detected in Florida homes with entries in the recently updated mVOC 4.0 database [27]. This resource catalogs microbial volatiles and their known producers, allowing us to make informed inferences about hidden fungal growth. Several of the compounds we measured (such as 1-octen-3-ol, 2-heptanone, geosmin, and 3-methylfuran) are characteristic metabolites of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Stachybotrys, and Fusarium. Fungal colonization on damp building substrates substantially elevates emissions of MVOCs, including 1-octen-3-ol and 2-heptanone [22]. Distinct MVOC, including ketones and alcohols such as 3-methylfuran, were identified from Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium species cultured on building materials [28]. Furthermore, toxigenic strains of Stachybotrys chartarum on wallboard emit unique MVOCs such as anisole, serving as markers for concealed fungal growth [29]. The appearance of these volatiles in our samples suggests that active fungal colonization may still be occurring behind damp walls and flooring, even in homes where visible mold was minimal. By aligning chemical signals with microbial sources, the database strengthens the interpretation of MVOCs as early warning indicators of hidden contamination, while also highlighting their broader relevance for post-flood indoor air quality assessments.

3.3. Surface Microbial Activity in Flood-Affected Homes

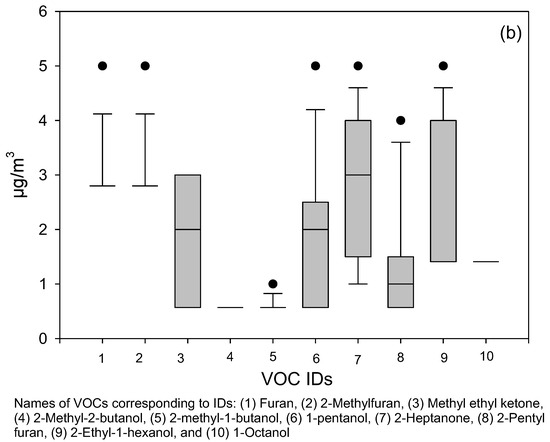

The distributions of microbial activity across different surfaces (floors, tables, door handles, and walls) are presented below in Figure 3. ATP bioluminescence assays revealed substantial variability in microbial activity across tested surfaces. Floors exhibited the highest median (IQR) activity (267, 225 RLU/cm2), followed by door handles (81, 128.75), tables (29, 111), and walls (12, 26.5) (all units are RLU/cm2). The elevated microbial load on floors is consistent with previous work demonstrating that floors act as major sinks for microbial deposition and resuspension [30]. Conversely, walls, which are less frequently contacted, showed the lowest ATP activity. These findings highlight that high-touch surfaces (e.g., tables, door handles) may serve as secondary reservoirs, sustaining microbial transfer between occupants and indoor environments, even when visual microbial growth is absent [31]. Floors showed the highest activity with a median of 267 RLU, highlighting their role as significant microbial reservoirs [30,31].

Figure 3.

Variations in microbial activity across 13 homes on different surfaces. The lower and upper boundaries of the box specify the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The line within the box indicates the median, and the whiskers above and below the box indicate the 95th and 5th percentiles, respectively.

Notable connections between microbial activity and odor were identified, underscoring the intricate interactions between moisture and microbial growth that affect odor emissions. A moderate negative correlation was observed between odor and average microbial activity (ρ = −0.569, p < 0.01). This apparent inverse relationship between odor intensity and microbial activity may reflect differences in microbial community composition, metabolic states, or the lag between moisture persistence and detectable microbial growth. These findings extend prior work by demonstrating that reliance on visual inspection alone may underestimate health-relevant exposures. Elevated TMVOCs and ATP activity in homes with minimal visible mold support the need for broader assessment frameworks that include chemical and biological indicators.

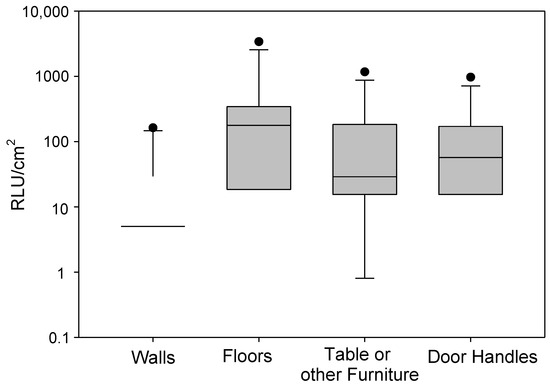

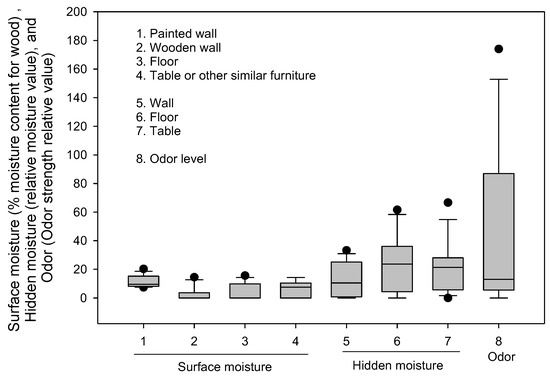

3.4. Hidden Moisture Levels in Flood-Affected Homes and Other Environmental Parameters

The levels of temperature, relative humidity, surface moisture, and hidden moisture (medians and IQR) across 13 homes were: 24.2 (0.8) °C, 64.7 (2)%, 8.05 (3.97) WME, and 13.76 (12.87) MC, respectively. The measured environmental parameters (relative humidity averaging 64% and elevated hidden moisture) reinforce the persistence of damp conditions favorable for microbial survival and growth. Hidden moisture ranged from 5 to 66.6 relative MC, with floors showing the highest values. Surface moisture, expressed as WME, was generally lower (range 3–18% WME). The persistence of elevated hidden moisture more than one year after Hurricane Ian is a notable finding because it indicates that microbial growth may remain active even when visible surfaces appear dry. Prior studies have shown that relative humidity above 60% and hidden moisture >15% are sufficient to sustain fungal proliferation [2,32]. Thus, these data highlight the importance of using moisture meters and thermal imaging rather than relying solely on visual inspection. These values are above thresholds typically associated with elevated microbial risk, as prior studies have suggested that mold proliferation accelerates when relative humidity exceeds 60% and when building materials remain damp for extended periods [2]. The levels and variations in surface moisture and hidden moisture across 13 sampled homes are presented below in Figure 4. Although sampling was conducted more than one year after Hurricane Ian, this timing remains relevant for assessing health risks. Prior studies have shown that moisture can persist for months or years in subflooring, wall cavities, and insulation, creating long-term ecological niches for fungal growth even after superficial drying or remediation [5,9]. Our finding of hidden moisture up to 66.6 MC in one home, alongside moderate levels in others, demonstrates that residual dampness and microbial activity were still sustained long after the flood. Importantly, post-disaster recovery is often heterogeneous, and many households experience incomplete or delayed remediation, meaning residents may remain exposed to microbial byproducts well beyond the immediate aftermath. Thus, delayed sampling provides valuable insight into the chronic phase of exposure, complementing rapid-response studies and highlighting the need for long-term monitoring and remediation strategies.

Figure 4.

The box plots illustrate variations in surface moisture (%), hidden moisture (relative moisture value), and odor levels (dimensionless relative value) across 13 sampled homes. The lower and upper boundaries of the box specify the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The line within the box indicates the median, and the whiskers above and below the box indicate the 95th and 5th percentiles, respectively.

Taken together, the correlation analysis and descriptive statistical analysis of data suggest that indoor microbial exposures after flooding are influenced by a complex interplay of surface moisture, odor, and chemical emissions, rather than being driven solely by visible mold or localized dampness.

3.5. Public Health Implications

Because no clinical or epidemiological data were collected in this pilot study, health-related statements are framed as hypotheses requiring future validation. The presence of MVOCs and ATP activity should therefore be interpreted as potential indicators of risk, not direct evidence of adverse health outcomes.

From a health perspective, the presence of MVOCs and microbial contamination in homes poses risks for individuals with asthma, allergies, and other respiratory conditions. Flood-related dampness has been repeatedly associated with increased rates of wheeze, coughing, and asthma exacerbations in both children and adults [3,4]. Sensitive populations, including children, the elderly, and those with immuno-compromised conditions, are likely to be disproportionately affected by prolonged exposure in inadequately remediated homes.

Importantly, epidemiological research has established that residential dampness and mold are consistently linked to a 30–50% increased risk of asthma exacerbation and respiratory symptoms in both children and adults [33,34]. The WHO [33,35] guidelines on indoor dampness and mold, as well as earlier recommendations on bioaerosol exposure, emphasize that even moderate levels of visible dampness and microbial growth are sufficient to increase the risk of adverse respiratory outcomes, regardless of specific fungal species present. Similarly, the Institute of Medicine [34] concluded that damp indoor environments contribute significantly to asthma morbidity and other respiratory conditions. These international syntheses of large-scale cohort and case–control studies provide critical context for interpreting the signals observed here.

Moreover, the detection of microbial activity on high-contact surfaces such as door handles and tables highlights potential transmission pathways for opportunistic pathogens seeded by contaminated floodwaters. While ATP assays cannot differentiate pathogenic from non-pathogenic organisms, they signal the need for comprehensive cleaning and disinfection protocols during post-flood recovery. These findings align with both the WHO bioaerosol guidelines and dampness guidelines and large-scale epidemiological evidence linking residential dampness to elevated risks of asthma, respiratory irritation, and allergic sensitization [3,4,32,33,34,35]. Even moderate TMVOC concentrations, if persistent, may contribute to significant health burdens in sensitive populations.

3.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study provides an important snapshot of microbial hazards in Hurricane Ian–impacted homes, combining chemical (TMVOC) and biological (ATP) methods to capture hidden contamination. However, several limitations should be noted. First, the sample size was small (13 homes), limiting generalizability across the whole affected region. The timing of data collection in this study may be seen as a limitation since it occurred a year after the hurricane. However, it is important to recognize that moisture can linger in homes affected by flooding long after the storm has passed and even after remediation efforts. This ongoing moisture can potentially pose a health risk. Second, ATP assays cannot specify microbial taxa, requiring complementary microbiological methods (e.g., culture-based, qPCR, or next-generation sequencing) in future studies. Third, the cross-sectional design captures contamination at one point in time, without accounting for temporal variations during different stages of remediation. Interpretation of findings is further complicated by variability in remediation practices, ventilation conditions, and socioeconomic circumstances among households, all of which may influence microbial outcomes [5,9]. In practice, these factors can create substantial variability across homes with similar flood exposures. Remediation practices differ widely, with some households employing professional drying and mold abatement services while others rely on surface-level cleaning or delayed interventions, leading to divergent levels of residual contamination. Ventilation conditions further contribute, as well-ventilated homes are able to reduce humidity and disperse MVOCs more effectively, whereas poorly ventilated spaces retain dampness and microbial by-products. Socioeconomic circumstances also play a critical role: families with greater resources may replace water-damaged building materials or install air purification systems, while those with fewer resources may be forced to remain in inadequately remediated environments. Together, these differences act as important confounders that influence microbial outcomes independently of the flood event itself, complicating efforts to generalize the findings to broader populations.

Future research should expand sampling to larger populations and incorporate health outcome data from residents, thereby strengthening the evidence linking environmental contamination with morbidity. Longitudinal designs could capture changes in microbial and VOC levels as remediation progresses, providing guidance for evidence-based intervention strategies. Integration with community-based participatory research could also ensure that findings inform actionable policies and household-level practices.

4. Conclusions

Overall, the study highlights the persistent risk of hidden microbial contamination in flood-affected homes, even when visible mold growth is absent. Moderate TMVOC levels and elevated ATP values on surfaces provide preliminary evidence of ongoing microbial activity sustained by residual dampness. The findings also revealed significant negative relationships between odor and surface microbial activity, and this finding indicates that odors might originate from hidden microbes rather than from the microbes on surfaces measured by the ATP bioluminescence method. Although based on a small, non-representative sample, these findings suggest that combining TMVOC and ATP indicators can serve as a practical framework for post-disaster environmental microbial assessment.

The study outcomes emphasize the need for post-flood remediation strategies that extend beyond superficial cleaning and renovation, incorporating continuous monitoring to guide moisture control, targeted disinfection, and safe re-occupancy. Therefore, protecting vulnerable populations in hurricane-affected regions requires moving beyond visual assessments. Coordinated public health and housing policies should integrate assessments of hidden moisture and MVOCs to guide effective remediation, safe re-occupancy decisions, and long-term monitoring programs. Future research should expand to larger, more diverse populations, standardize sampling protocols, and directly link environmental contamination with occupant health outcomes [3,4].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and J.G.; methodology, A.A.; formal analysis, O.J.; investigation, V.C.E., O.A.-F., A.A., J.G. and O.J.; resources, A.A., J.G. and M.S.; data curation, O.J.; writing—original draft preparation, O.J. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A., O.J., J.G. and M.S.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, A.A. and J.G.; project administration, A.A. and J.G.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was made possible through the generous funding provided by the Faculty Research Committee FY24 (2023–2024) Research Seed Funding or Scholarly Pursuit Award at Georgia Southern University, awarded to Dr. Atin Adhikari.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol underwent review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Florida Gulf Coast University, which determined it to be exempt since there was no direct involvement of human subjects. Homeowners provided informed consent via telephone or email prior to sampling. To ensure participant confidentiality, all data were anonymized, and results were shared with homeowners, along with interpretations of data, upon request.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected in the study can be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude for the Faculty Research Committee FY24 (2023–2024) Research Seed Funding or Scholarly Pursuit Award at Georgia Southern University. The generous participation of the community organizations and residents of flood-affected homes in the Fort Myers area is greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The Office of Research, Georgia Southern University, had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VOC | Volatile Organic Carbons |

| MVOC | Microbial Volatile Organic Carbons |

| TVOC | Total Volatile Organic Carbons |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality |

| AIHA | American Industrial Hygiene Association |

| GC/MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| DMAT | Dampness and Mold Assessment Tool |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PID | Photoionization Detector |

| RLU | Relative Light Units |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

References

- Brandt, M.; Brown, C.; Burkhart, J.; Burton, N.; Cox-Ganser, J.; Damon, S.; Falk, H.; Fridkin, S.; Garbe, P.; McGeehin, M.; et al. Mold prevention strategies and possible health effects in the aftermath of hurricanes and major floods. MMWR. Recommendations and reports: Morb. Mortal. Wkly. report. Recomm. Rep. 2006, 55, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mudarri, D.; Fisk, W.J. Public health and economic impact of dampness and mold. Indoor Air 2007, 17, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendell, M.J.; Mirer, A.G.; Cheung, K.; Tong, M.; Douwes, J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quansah, R.; Jaakkola, M.S.; Hugg, T.T.; Heikkinen, S.A.; Jaakkola, J.J. Residential dampness and molds and the risk of developing asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, G.L.; Wilson, J.; Rabito, F.A.; Grimsley, F.; Iqbal, S.; Reponen, T.; Muilenberg, M.L. Mold and endotoxin levels in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: A pilot project of homes in New Orleans undergoing renovation. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1883–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Adhikari, A.; Jung, J.; Reponen, T.; Lewis, J.S.; DeGrasse, E.C.; Grimsley, L.F.; Chew, G.L.; Grinshpun, S.A. Aerosolization of fungi, (1-->3)-beta-D glucan, and endotoxin from flood-affected materials collected in New Orleans homes. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.; Lewis, J.S.; Reponen, T.; Degrasse, E.C.; Grimsley, L.F.; Chew, G.L.; Iossifova, Y.; Grinshpun, S.A. Exposure matrices of endotoxin, (1→3)-β-d-glucan, fungi, and dust mite allergens in flood-affected homes of New Orleans. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5489–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omebeyinje, M.H.; Adeluyi, A.; Mitra, C.; Chakraborty, P.; Gandee, G.M.; Patel, N.; Verghese, B.; Farrance, C.E.; Hull, M.; Basu, P.; et al. Increased prevalence of indoor Aspergillus and Penicillium species is associated with indoor flooding and coastal proximity: A case study of 28 moldy buildings. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2021, 23, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesper, S.; McKinstry, C.; Cox, D.; Dewalt, G. Correlation between ERMI values and other moisture and mold assessments of homes in the American Healthy Homes Survey. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2009, 86, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpi, A.; Järnberg, J.; Pasanen, A.L. Microbial volatile organic compounds. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2009, 39, 139–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, A.; Kanazawa, A.; Kawai, T.; Eitaki, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Nakayama, K.; Shibata, E.; Tanaka, M.; Takigawa, T.; Yoshimura, T.; et al. The relationship between exposure to microbial volatile organic compound and allergy prevalence in single-family homes. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 423, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nielsen, G.D. Mechanisms of Activation of the Sensory Irritant Receptor by Airborne Chemicals. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1991, 21, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, S.R.; Hall, E.C.; Marciniak, K.; Misztal, P.K.; Goldstein, A.H.; Adams, R.I.; Dannemiller, K.C. Microbial growth and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions from carpet and drywall under elevated relative humidity conditions. Microbiome 2021, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.L.; Elfman, L.; Mi, Y.; Wieslander, G.; Smedje, G.; Norbäck, D. Indoor molds, bacteria, microbial volatile organic compounds and plasticizers in schools--associations with asthma and respiratory symptoms in pupils. Indoor Air 2007, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospodsky, D.; Qian, J.; Nazaroff, W.W.; Yamamoto, N.; Bibby, K.; Rismani-Yazdi, H.; Peccia, J. Human occupancy as a source of indoor airborne bacteria. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, C.J.; Cooper, R.A.; Gilmore, J.; Davies, C.; Lewis, M. An evaluation of hospital cleaning regimes and standards. J. Hosp. Infect. 2000, 45, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.M.; Rasch, M.; Kvist, J.; Tollefsen, T.; Lukkassen, R.; Sandvik, L.; Welo, A. Floor cleaning: Effect on bacteria and organic materials in hospital rooms. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 71, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Hurricane Center. Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ian. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2023. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL092022_Ian.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- NIOSH. Dampness and Mold Assessment Tool for General Buildings—Form & Instructions. Cox-Ganser J, Martin M, Park JH, Game, S. Morgantown WV: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2019-115. 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.26616/NIOSHPUB2019115 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- EPA. Compendium Method TO-17: Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Using Active Sampling onto Sorbent Tubes. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Method TO-17—Determination of Volatile Organic Compounds in Ambient Air Using Active Sampling onto Sorbent Tubes. 1999. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/documents/to-17r.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ISO 16000-6; Indoor Air—Part 6: Determination of Organic Compounds (VVOC, VOC, SVOC) in Indoor and Test Chamber Air by Active Sampling on Sorbent Tubes, Thermal Desorption, and Gas Chromatography Using MS or MSFID. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Korpi, A.; Pasanen, A.L.; Pasanen, P. Volatile compounds originating from mixed microbial cultures on building materials under various humidity conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2914–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Janson, C.; Gislason, T.; Gunnbjörnsdottir, M.; Jogi, R.; Orru, H.; Norbäck, D. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in homes are associated with asthma and lung function among adults in Northern Europe. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 321, 121103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, K.; Larsen, K.; Simkus, M. Volatile metabolites from mold growth on building materials and synthetic media. Chemosphere 2000, 41, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleibinger, H.; Laussmann, D.; Bornehag, C.G.; Eis, D.; Rueden, H. Microbial volatile organic compounds in the air of moldy and mold-free indoor environments. Indoor Air 2008, 18, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.J.; Beaucham, C. Dominant microbial volatile organic compounds in 23 U.S. homes. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmler, E.; Lemfack, M.C.; Goede, A.; Gallo, K.; Toguem, S.M.T.; Ahmed, W.; Millberg, I.; Preissner, S.; Piechulla, B.; Preissner, R. mVOC 4.0: A database of microbial volatiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1692–D1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, K.; Schütz, E. Detection of microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOCs) produced by moulds on various materials. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2001, 204, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, D.A.; Krebs, K.; Moore, S.A.; Martin, S.M. Microbial volatile organic compound emissions from Stachybotrys chartarum growing on gypsum wallboard and ceiling tile. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Hospodsky, D.; Yamamoto, N.; Nazaroff, W.W.; Peccia, J. Size-resolved emission rates of airborne bacteria and fungi in an occupied classroom. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, S.; Smith, D.P.; Hampton-Marcell, J.; Owens, S.M.; Handley, K.M.; Scott, N.M.; Gilbert, J.A. Longitudinal analysis of microbial interaction between humans and the indoor environment. Science 2014, 345, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannigan, B.; Miller, J.D. Microbial Growth in Indoor Environments. In Microorganisms in Home and Indoor Work Environments, 2nd ed.; Miller, J.D., Flannigan, B., Samson, R.A., Cox-Ganser, D.O., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 57–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Damp Indoor Spaces and Health. Damp Indoor Spaces and Health; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Bioaerosols: Assessment and Control; WHO Technical Report Series No. 941; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).