Abstract

Dynamic environments pose significant challenges for Visual Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (VSLAM), as moving objects can introduce outlier observations that severely degrade localization and mapping performance. To address this problem, we propose YSAG-VINS, a VSLAM algorithm specifically designed for dynamic scenes. The system integrates an enhanced YOLOv8 object detection network with an adaptive epipolar constraint strategy to effectively identify and suppress the impact of dynamic features. In particular, a lightweight YOLOv8n model augmented with ODConv and UIB modules is employed to balance detection accuracy with real-time efficiency. Based on semantic detection results, images are divided into static background and potentially dynamic regions, and the motion state of these regions is further verified using geometric constraints. Features belonging to truly dynamic objects are then removed to enhance robustness. Comprehensive experiments on multiple public datasets demonstrate that YSAG-VINS achieves superior pose estimation accuracy compared with VINS-Fusion, VDO-SLAM, and Dynamic-VINS. On three dynamic sequences of the KITTI dataset, the proposed method achieves average RMSE improvement rates of 48.62%, 12.18%, and 13.50%, respectively. These results confirm that YSAG-VINS provides robust and high-accuracy localization performance in dynamic environments, making it a promising solution for real-world applications such as autonomous driving, service robotics, and augmented reality.

1. Introduction

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) is a fundamental technology for enabling situational awareness in mobile robots. It allows robots to estimate their position within unknown environments, thereby supporting efficient navigation, path planning, and autonomous decision-making. With the rapid development of camera technology and computing systems in recent years, visual sensors have become not only cost-effective but also capable of providing rich spatial and structural information [1]. This progress has significantly enhanced the capability of robots to achieve accurate self-localization and robust navigation. However, many established visual SLAM systems (e.g., PTAM [2], ORB-SLAM2 [3], SVO [4], Kimera [5], VINS-Mono [6], LSD-SLAM [7]) were primarily designed under the assumption of static environments, which often does not hold in real-world applications. In dynamic settings, moving objects such as pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles introduce outlier measurements that can substantially degrade localization accuracy and mapping consistency.

To overcome these challenges, researchers have increasingly explored approaches that integrate geometric constraints with semantic perception. Deep learning techniques such as semantic segmentation and object detection have been shown to improve the robustness of SLAM in dynamic environments [8,9,10,11]. Nevertheless, existing methods still face important limitations: (i) high computational overhead restricts deployment in resource-constrained platforms; (ii) heuristic rules for handling dynamic objects often lack adaptability across diverse scenarios; and (iii) limited robustness under severe occlusion or extreme dynamic scenes reduces their practical applicability. These gaps highlight the need for a more efficient, adaptive, and scalable strategy to suppress the influence of dynamic objects while preserving real-time performance.

In this paper, we propose YSAG-VINS, a visual–inertial SLAM system that integrates YOLOv8-based semantic detection with adaptive geometric constraints to enhance robustness in dynamic environments. Unlike prior works such as DynaVINS or VDO-SLAM, which either rely heavily on computationally expensive detectors or use fixed geometric thresholds, YSAG-VINS introduces two key innovations: (i) a lightweight yet accurate detector (YOLOv8n-ODUIB) optimized for real-time inference, and (ii) an adaptive epipolar-geometry mechanism that dynamically adjusts thresholds based on background features, thereby avoiding the over-removal of static information. Together, these innovations contribute a more balanced solution that improves localization accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

YSAG-VINS is particularly well-suited for real-world applications where both high precision and real-time efficiency are critical, such as autonomous driving, urban delivery robots, and service robots operating in crowded or dynamically changing environments. In these scenarios, high localization accuracy ensures safe navigation and collision avoidance, while real-time processing enables immediate decision-making and responsiveness to dynamic obstacles. The adaptive design of YSAG-VINS allows the system to dynamically modulate its reliance on semantic information depending on the scene conditions, making it robust in situations with occlusions, low visibility, or high traffic density. Moreover, the computational efficiency of the YOLOv8n-ODUIB detector facilitates deployment on resource-constrained platforms, such as small autonomous vehicles or embedded robotic systems, without compromising performance. By addressing both precision and efficiency requirements, YSAG-VINS provides a practical and scalable solution for dynamic scene SLAM in a variety of real-world applications.

The main contributions of this article are as follows:

(1) We design and integrate an enhanced YOLOv8n-ODUIB object detection network into the VINS-Fusion framework. Unlike segmentation-based approaches such as DynaVINS and VDO-LAM, our method provides real-time semantic awareness with significantly lower computational cost, making it more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained platforms while maintaining high detection accuracy.

(2) To address the false removal of static features in purely detection-based filtering, we propose an adaptive geometry-guided strategy. Specifically, the threshold of the epipolar constraint is dynamically adjusted according to static background features, enabling the system to more reliably distinguish truly dynamic features from pseudo-dynamic ones. This design improves robustness and localization stability in challenging scenarios such as occlusion and multi-object motion.

(3) We conduct extensive experiments, including (i) benchmarking the proposed YOLOv8n-ODUIB against the baseline YOLOv8n on the BDD100K dataset for accuracy and real-time performance, and (ii) comparing YSAG-VINS with VINS-Fusion and several state-of-the-art dynamic SLAM systems on KITTI, M2DGR, and M2UD datasets. Results demonstrate that YSAG-VINS achieves a novel balance between robustness and efficiency, outperforming existing methods in dynamic environments.

2. Related Work

At present, most SLAM systems are designed under the assumption of a static environment. Compared with visual SLAM in static scenes, the presence of dynamic objects presents significant challenges to system stability and localization accuracy [12]. Regardless of whether feature-based or direct methods are used, visual SLAM systems fundamentally rely on feature correspondences in images to estimate camera pose. Motion inconsistency between dynamic objects and the static background disrupts the geometric consistency of these correspondences, leading to failures in data association, increased pose estimation errors, or even system crashes [13]. Therefore, accurately detecting and suppressing dynamic features is critical for improving SLAM performance in dynamic environments. Existing research in this area can be broadly divided into two main approaches: geometry-based methods and semantics-based methods., each with different trade-offs between computational cost and robustness.

2.1. The Methods Based on Geometric Information

Geometry-based approaches detect motion by analyzing variations in spatial positions and motion patterns of feature points, typically leveraging 3D coordinates and optical flow information. Pablo et al. [14] proposed a stereo SLAM algorithm for dynamic scenes that incorporates scene flow analysis by computing dense optical flow for each pixel and identify dynamic regions using thresholding. Tan et al. [15] introduced an improved adaptive RANSAC algorithm into the PTAM framework, combining geometric constraints with object color information to distinguish dynamic objects. Wang et al. [16] combined optical flow with clustering techniques to propose a dynamic scene SLAM method based on RGB-D cameras. These methods are generally computationally efficient and thus well-suited for real-time applications. However, their lack of semantic awareness makes them vulnerable when dynamic objects dominate the scene or when motion patterns are ambiguous, often leading to degraded accuracy or tracking failures.

2.2. The Methods Based on Semantic Information

With the rapid progress of deep learning in computer vision, semantic-based techniques have emerged as a promising direction for dynamic SLAM. These approaches can generally be divided into semantic segmentation networks and object detection networks. For instance, DynaSLAM, proposed by Berta Bescos et al. [17], combines the Mask R-CNN semantic segmentation network with multi-view geometry to detect dynamic objects and remove outliers. Runz et al. [18] introduced MaskFusion, which integrates Mask R-CNN [19] to achieve pixel-level segmentation and tracking of dynamic objects. Chang et al. [20] combined the real-time instance segmentation network YOLACT [21] with geometric constraints and dense optical flow for dynamic object detection and background reconstruction. VDO-SLAM [22] combines Mask R-CNN, dense optical flow, and rigid-body constraints to jointly estimate camera and object motion, improving robustness but with high computational cost. In addition, studies [23,24,25] introduced lightweight semantic segmentation networks and dynamic detection modules with co-optimization to further improve localization accuracy and robustness. Despite their accuracy, segmentation networks impose heavy computational costs, making them difficult to deploy on real-time or resource-constrained platforms.

In contrast, object detection-based methods offer better computational efficiency while retaining semantic awareness capabilities. For instance, Cheng et al. [26] proposed SG-SLAM, which employs a lightweight NCNN network for real-time object detection, combined with epipolar constraints and semantic-weighted adaptive filtering of dynamic points. This effectively addresses the threshold sensitivity problem inherent in traditional geometric methods. However, this approach relies on manually predefined weights based on prior knowledge and lacks adaptability to dynamic scene changes. COEB-SLAM [27] identifies dynamic objects by integrating object detection results with motion blur constraints and removes dynamic feature points using epipolar geometry. DynaVINS [28] integrates YOLOv3 detection with multi-hypothesis constraints, achieving real-time efficiency while maintaining accuracy in dynamic environment. Sun et al. [29] employ a lightweight object detector to generate semantic information, which is combined with geometric constraints and a feature-depth-based RANSAC algorithm to mitigate the impact of dynamic features. Moreover, study [30] proposed an improved version of the YOLOv5s detection network and introduced a dynamic logic decision mechanism, retaining only static feature points for subsequent pose estimation and map construction. Based on the characteristics and limitations of these methods, we compare the main technical approaches and performance of existing dynamic SLAM methods, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of existing dynamic SLAM methods.

Although the above methods have achieved promising results in enhancing SLAM accuracy and robustness in dynamic environments, several limitations persist:

(1) The recognition failure of dynamic objects under occlusion: Object detection-based approaches [26,27,28] are prone to missed detections in scenes with dynamic or static occlusions (e.g., vehicles obscured by moving objects or static structures such as fences). This results in incomplete semantic representations of the environment. In dynamic regions, the spatiotemporal continuity of features is disrupted, weakening the system’s ability to establish stable feature correspondences across frames.

(2) The over-removal of feature information caused by fixed threshold strategies: Most deep learning-based methods adopt fixed thresholds to remove all features within detected dynamic object regions [20,25,26,27,28], based on geometric priors. However, in complex outdoor scenes, such fixed strategies can lead to over-removal. For instance, stationary vehicles may be mistakenly classified as dynamic and removed, reducing the number of valid features for matching and optimization, thereby impairing the robustness and completeness of the generated map.

(3) The insufficient real-time performance: Semantic-enhanced SLAM systems [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] typically suffer from heavy network architectures, large parameter sizes, and computational latency. Coupled with inefficient resource scheduling, these limitations make it difficult to achieve high-frame-rate processing and limit deployment on real-time platforms such as mobile robots.

3. System Overview

3.1. The System Architecture of the Proposed Algorithm of YSAG-VINS

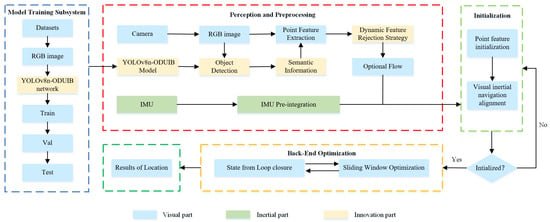

The proposed system is built upon the VINS-Fusion framework, which is widely regarded as one of the most comprehensive and robust open-source visual-inertial SLAM algorithms. Leveraging VINS-Fusion as the core infrastructure enables YSAG-VINS to achieve reliable global localization. As depicted in Figure 1, the overall architecture of YSAG-VINS comprises three principal components: Model Training Subsystem, Perception and Preprocessing, Initialization, and Back-End Optimization.

Figure 1.

System Framework.

In the Perception and Preprocessing module, YSAG-VINS incorporates a dedicated object detection thread operating in parallel with the tracking thread. This multithreaded design significantly improves the system’s runtime efficiency. The primary objective of introducing the object detection thread is to utilize a deep neural network to extract prior semantic information, which forms the foundation of the system’s dynamic feature rejection strategy. This mechanism enables the identification of potentially dynamic objects in the scene, thereby improving tracking robustness in dynamic environments.

During system operation, RGB image frames captured by the camera are simultaneously fed into both the tracking thread and the object detection thread. The object detection thread performs object recognition on the input images, while the tracking thread concurrently extracts point features from the same frames. Following feature extraction, the tracking thread employs a pyramidal iterative Lucas-Kanade optical flow method to perform sparse feature tracking between consecutive frames. Subsequently, a RANSAC-based seven-point algorithm is applied to estimate the fundamental matrix, which effectively mitigates the adverse impact of incorrect feature associations in dynamic regions.

It is worth noting that object detection generally incurs higher computational overhead compared to feature extraction and fundamental matrix estimation. Consequently, the tracking thread must wait for the detection results after computing the fundamental matrix before proceeding. However, since only object-level detection information (as opposed to pixel-level semantic segmentation) is required, the waiting time remains relatively short, thus preserving the system’s real-time performance. Once the detection results are available, the tracking thread integrates the semantic information to distinguish potentially dynamic regions from the static background. Epipolar constraints are then applied to the subset of features associated with the static background, and the average epipolar deviation is computed. This average deviation serves as an adaptive threshold for rejecting feature points that are likely to belong to dynamic objects, thereby improving the accuracy of the final camera pose estimation. The Initialization and Back-End Optimization components in YSAG-VINS are fully inherited from the original VINS-Fusion framework, including its sliding window-based local optimization and loop closure mechanisms, ensuring robust and globally consistent mapping and localization.

3.2. The Optimization Algorithm of Object Detection Based on the Enhanced YOLOv8

An efficient real-time object detection algorithm is essential for enabling fast processing of image data from the camera sensor and ensuring seamless integration with other SLAM components, such as feature extraction, feature matching, and pose estimation. In this work, we adopt the YOLOv8 object detection algorithm, known for its high inference speed. However, in urban dynamic scenes, the presence of occlusions often leads to deformation of potential dynamic targets, which can degrade detection accuracy. Such failures may result in previously detected into the SLAM pipeline.

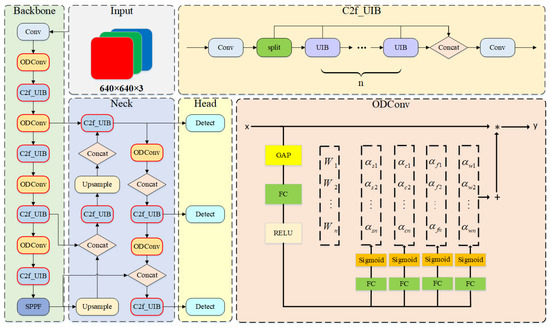

To overcome this limitation, the ODConv (Omni-Dimensional Dynamic Convolution) and the C2f (Concatenate and Fuse) modules are used to improve the neural network structure of YOLOv8. The enhanced detection network, termed YOLOv8n-ODUIB, is shown in Figure 2. It is specifically designed to improve detection robustness in dynamic and occluded scenarios while maintaining computational efficiency. In the original YOLOv8 architecture, the network is divided into three main components: the backbone, the neck, and the detection head. Traditional convolution operations rely on fixed kernel weights, which limit the model’s ability to adapt to the diverse characteristics of input data. To address this limitation, the ODConv module is introduced to significantly enhance the network’s capability for dynamic feature extraction. Specifically, ODConv dynamically adjusts the convolutional kernel weights along four dimensions of the input feature map, enabling the convolution operation to better accommodate targets of varying scales and shapes. This omni-dimensional adaptability allows the network to more effectively model the fine-grained details of multi-scale objects, thereby improving detection performance in complex scenes. As illustrated in Figure 2, the integration of ODConv into both the backbone and neck components enables the network to capture richer and more discriminative representations of the input data. The definition and implementation of the ODConv are as follows:

where denotes the convolution parameters along the spatial dimensions, is the corresponding parameters associated with the input channel dimension, pertains to those along the output channel dimension, and represents the parameters related to the kernel’s spatial extent; Moreover, denotes the input data, is convolution kernel, and denotes the output data.

Figure 2.

The YOLOv8n-ODUIB network architecture.

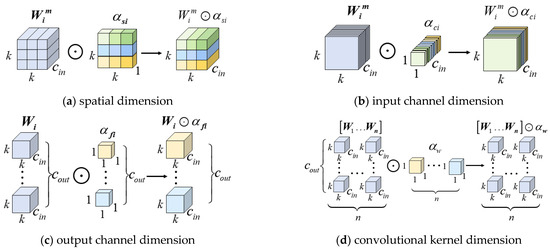

More specifically, Figure 3 illustrates the process of applying four-dimensional attention in the kernel space to the convolutional kernels [31]. This process involves adjusting the convolutional weights along the kernel dimension, spatial dimension, input channel dimension, and output channel dimension, respectively. These four attention mechanisms complement and coordinate with each other, enabling the model to exert differentiated influence across various dimensions of the input data. As a result, the convolutional neural network becomes more adaptable to variations in input features and enables more flexible convolution operations to handle complex and diverse data, thereby better accommodating the complexity and dynamic nature of the target.

Figure 3.

The applying process of ODConv.

This dynamic adjustment feature not only improves the accuracy of feature extraction but also enhances the network’s generalization capability in complex scenes. It effectively optimizes the semantic recognition of dynamic objects, even in the presence of occlusion deformation and motion blur. To address the attention of both shallow and deep features for object recognition, the ODConv module is integrated into the YOLOv8 Backbone, applied to all convolutional layers except the first layer, as well as all convolutional layers in the Neck section.

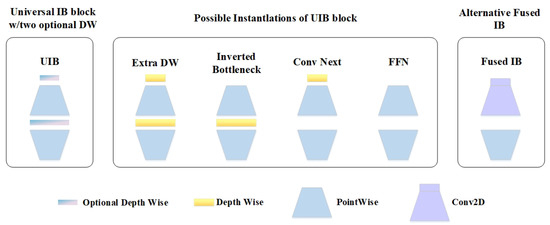

In addition, the C2f module in YOLOv8 employs a relatively simple channel extraction mechanism, which lacks the ability to dynamically emphasize critical channel features. This limits the detection capability for objects, as it cannot fully capture global information in complex scenes. Moreover, the C2f module has a high parameter count and computational complexity, making it less suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices. To overcome these limitations, we propose a novel C2f_UIB structure, inspired by the UIB (Unified Inverted Bottleneck) design in MobileNetV4 [32]. The inverted bottleneck structure of C2f_UIB enhances channel feature extraction by dynamically adjusting inter-channel weights, thereby improving the network’s ability to capture key features. Furthermore, the C2f_UIB introduces dilated convolutions, which enlarge the receptive field and improve the ability to capture global information. Importantly, the C2f_UIB structure maintains efficient feature extraction while significantly reducing parameter size and computational complexity. This results in a lightweight improvement of the YOLOv8 model, making it more suitable for deployment on devices with limited computational resources. The general inverted bottleneck structure is shown in Figure 4. When a new image is captured by the camera, the improved YOLOv8n-ODUIB model is employed to perform object detection. Based on the detection results, the environment is divided into potential dynamic regions and static background. The potential dynamic regions correspond to areas containing movable object categories, such as pedestrians, vehicles (including parked cars), and riders. In contrast, the static background includes all remaining areas outside the potential dynamic regions, including elements such as grass, street lamps, and other immobile structures.

Figure 4.

General inverted bottleneck structure.

3.3. The Dynamic Feature Rejection Strategy Based on the Epipolar Constraint of Dynamic Threshold

After obtaining semantic bounding boxes through object detection, feature points located outside the bounding boxes are classified as static features, whereas those within the bounding boxes are initially treated as potential dynamic features. Static features, due to their stable spatial positions relative to the scene, contribute to accurate pose estimation in the SLAM system. In contrast, dynamic features, which move relative to the world coordinate system, can introduce significant errors if included in the pose estimation process.

To enhance the robustness of visual localization in dynamic environments, traditional methods typically remove all feature points within potential dynamic regions. However, this strategy has notable limitations: in scenes dominated by dynamic objects, the number of static feature points outside the bounding boxes may be insufficient to support accurate pose estimation, potentially resulting in tracking failure. To address this issue, the proposed YSAG-VINS system employs the pyramidal iterative Lucas–Kanade optical flow method to compute feature correspondences. Compared to conventional ORB-based matching, this method offers significantly higher computational efficiency, meeting real-time processing requirements while providing denser feature correspondences to enhance the robustness of motion estimation. Notably, in highly dynamic scenes, the optical flow method exhibits superior adaptability to fast object motion, effectively mitigating mismatches in ORB feature point caused by viewpoint variation or motion blur.

After obtaining the set of optical flow correspondence, the system employs the RANSAC seven-point algorithm to estimate the essential matrix using the static feature points located outside the detection bounding boxes, thereby establishing a reliable geometric constraint. This hierarchical processing strategy not only retains the positional accuracy advantages of static features but also enhances the system’s robustness in dynamic environments through the dynamic feature filtering mechanism. As a result, the system provides a more reliable and resilient solution for visual localization in complex and dynamic scenarios.

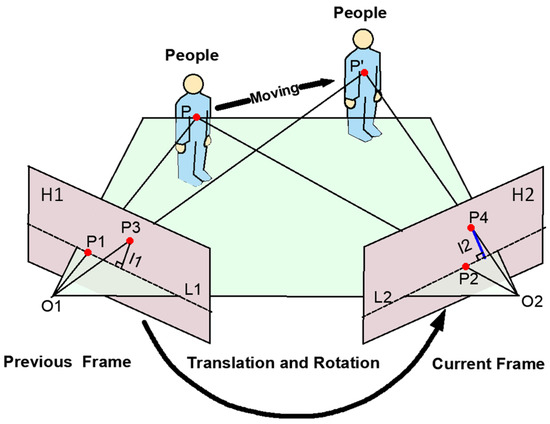

According to the pinhole camera model, let the camera centers of two image frames be and . The plane determined by the spatial point and these two camera centers is the epipolar plane. The image planes (previous frame) and (current frame) intersect this epipolar plane to form the epipolar lines L1 and L2, respectively. The projection of on is , its theoretical projection on is , while the projection of the displaced spatial point (caused by camera motion or target displacement) on is , as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Epipolar constraint.

The epipolar line is determined by the fundamental matrix :

where , and represent the components of the epipolar line vector. Based on the relationship between corresponding feature points expressed by the fundamental matrix , the epipolar constraint can be derived as follows:

The offset distance between the feature point ( = 2, 4) in the current frame and the corresponding epipolar line is given by:

Ideally, if a feature point belongs to the static background, its offset distance should be zero. However, in practical scenarios, the offset distance is generally greater than zero but remains below an empirical threshold ε, due to factors such as image noise, feature localization inaccuracies, and camera calibration errors [25].

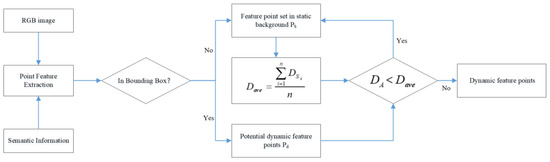

In outdoor scenarios, due to the rapid movement of the carrier, the offset distance in the epipolar constraint is affected by the magnitude of the carrier’s motion [33]. Traditional fixed empirical thresholds often fail to effectively eliminate dynamic points from potential dynamic regions. To address this issue and enhance detection accuracy under varying motion and scene conditions, this paper adopts an adaptive epipolar constraint method that is based on dynamic threshold to discriminate dynamic feature points. The core idea of the method is using the feature points of static background in current frame to real-time calculate the threshold of epipolar constraint, and the threshold serve as a constraint to effectively identify and reject potentially dynamic feature points. As shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the dynamic feature rejection strategy based on the epipolar constraint with a dynamic threshold.

The average epipolar distance of the feature point set in static background of the current frame is calculated, and the offset distance between the feature point of potential dynamic regions and the corresponding epipolar line is also calculated. By comparing the offset distance with the average epipolar distance, the dynamic characteristics of feature points in potential dynamic regions can be determined. The equation to calculate the average epipolar distance of the feature point set in static background of the current frame is constructed as follows:

For a feature point = (,) in a potential dynamic region, its offset distance the offset distance for feature points in the potential dynamic region is given by:

The rule for dynamic feature identification is formally defined as follows:

If < , the is considered as static feature point, otherwise, the is identified as dynamic feature points. And the identified dynamic feature point is eliminated. All the feature points in potential dynamic regions are identified using this method to determine whether they are dynamic feature points. The detailed implementation of this dynamic feature rejection strategy is provided in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Dynamic feature rejection strategy |

| Input: Previous frame’s feature point P1, Current frame’s feature point P2, Bounding BOX x1, y1, x2, y2 Output: The set of static feature points in the current frame, S F = FindFundmentalMat (P2, P1, seven-point method based on RANSAC) for each matched pair p1, p2 in P1, P2 do: if (Bounding BOX exist) then if (xp < x1||xp > x2||yp < y1||yp > y2) then Append p2 to S & DSi = CalEpipolarLineDistance (p1, p2, F) Traverse the number of feature points in S obtain && = DSi / end if else DA = CalEpipolarLineDistance (p1, p2, F) if (DA < ) then Append p2 to S end if else Append p2 to S end if end for |

4. Experiments

To evaluate the performance of the proposed object detection model, the BDD100K dataset [34] was employed for validation. In order to comprehensively assess the overall accuracy of the proposed YSAG-VINS system in dynamic outdoor scenarios, a series of systematic experiments were conducted using three benchmark datasets: KITTI dataset [35], the M2DGR dataset [36], and the M2UD [37]. For convenience in recording, the data sequences are denoted accordingly. All the experiments were conducted on a desktop workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4050 GPU (6 GB), a 13th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-13500H CPU @ 2.60 GHz.

4.1. The Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Object Detection Model

The BDD100K dataset, released by the University of California, Berkeley, is one of the largest and most diverse datasets for autonomous driving. In this experiment, over 60,000 images from the BDD100K dataset were partitioned into training, validation, and test sets at a ratio of 7:2:1. The training process was configured with a batch size of 32, using 1500 epochs, a weight decay rate of 0.0005, and the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer. The initial learning rate was set to 1 × 10−2. To mitigate overfitting, an early stopping strategy was applied, terminating training if no improvement in accuracy was observed over 100 consecutive epochs. The object detection model was evaluated using six key metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP@0.5 (mean average precision at IoU threshold = 0.5), mAP@0.5:0.95 (mean average precision across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95), parameter count (Param), and computational complexity (GFLOPs). Among these, mAP@0.5 was selected as the core performance indicator for this experiment.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, four experimental Groups were designed:

- Group 1: Baseline model using YOLOv8n.

- Group 2: YOLOv8n enhanced with the ODConv module.

- Group 3: YOLOv8n model incorporating the C2f module integrated with the proposed UIB structure.

- Group 4: Integrated model combining both ODConv and C2f_UIB modifications, under the same input conditions and hyperparameter settings as the other groups.

The comparative results of these configurations are presented in Table 2, which summarizes the ablation study on object detection performance. In Table 2, it can be observed that the baseline YOLOv8n (Group1) model achieves an mAP@0.5 and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of only 89.6% and 63.7%, indicating room for improvement. Introducing the ODConv module (Group 2) enhances the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 to 92.4% and 66.9%, respectively, albeit with increased computational overhead. The inclusion of the C2f module integrated with the proposed UIB structure (Group 3) also yields noticeable performance gains, and the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 are increased to 92.0% and 66.2%, respectively. Notably, when both enhancements are combined (Group 4), the model exhibits the most significant performance improvement: with minimal changes in parameter count, GFLOPs decrease by 28.7%, Precision increases by 4.5%, Recall rises by 2.6%, and mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 improve by 3.3% and 6.9%, respectively.

Table 2.

The statistics of ablation experiment of object detection for the four experimental Groups.

In terms of real-time inference speed, the model in Group 4 achieves 157.81 FPS, representing a 19.51% improvement over the baseline in Group 1. This considerable enhancement in detection speed demonstrates the model’s potential for deployment in real-time applications such as SLAM systems, where low latency and stable performance in dynamic environments are critical.

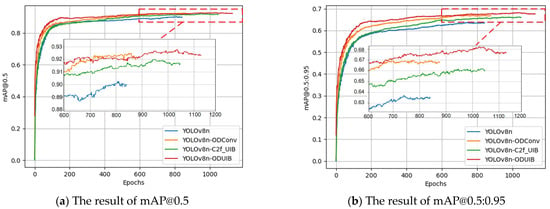

To further evaluate the recognition accuracy of the proposed object detection algorithm, a time-series analysis of the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics across training epochs was conducted for all four experimental groups. Figure 7 shows the time-series results of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 for the four Group. In Figure 7, it is evident that Group 1 (baseline YOLOv8n) consistently exhibits the lowest performance in both mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 throughout the training process, with values gradually stabilizing as the number of epochs increases. Group 2, which incorporates the ODConv module, achieves higher detection accuracy than Group 1 across most of the training period. Notably, during the 700–900 epoch range, Group 2 temporarily surpasses the proposed method in terms of mAP@0.5. However, signs of overfitting begin to emerge in Group 2 beyond epoch 850, leading to a relative decline in performance. Group 3, integrating the UIB structure in place of the C2f module, demonstrates relatively stable performance throughout training, but its final accuracy remains slightly below that of Group 2. In contrast, the proposed method (Group 4), which combines both the ODConv and UIB modules, consistently outperforms the other three configurations in terms of both mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 in the later training stages. Specifically, the proposed method achieves an mAP@0.5 of 92.6%, and under the stricter IoU threshold conditions, reaches an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 68.1%, representing a 6.9% improvement over the baseline model in Group 1. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the dual-module integration strategy in enhancing detection accuracy while maintaining robustness throughout the training process.

Figure 7.

The accuracy results of the metrics of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 for the designed Groups during the entire training epochs.

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed method in detecting dynamic targets across different object categories, a detailed evaluation was conducted on three representative dynamic classes: cars, cyclists, and pedestrians. Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of the performance metrics for the baseline YOLOv8n and the improved YOLOv8n-ODUIB model. As shown in Table 3, the proposed improvement led to consistent gains across all evaluation indicators. For the “Car” category, the improved model achieves a 1.2% increase in mAP@0.5 and a 3.3% increase in mAP@0.5:0.95. In the “Cyclist” category, the mAP@0.5 improves by 2.2%, while mAP@0.5:0.95 increases by 1.5%. The most notable enhancement is observed in the “Pedestrian” category, where the model achieves substantial gains of 5.5% in mAP@0.5 and 8.9% in mAP@0.5:0.95. These results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm can improve the detection performance of all designed dynamic object categories.

Table 3.

The comparative analysis of the performance metrics for the baseline YOLOv8n and the improved YOLOv8n-ODUIB model (%).

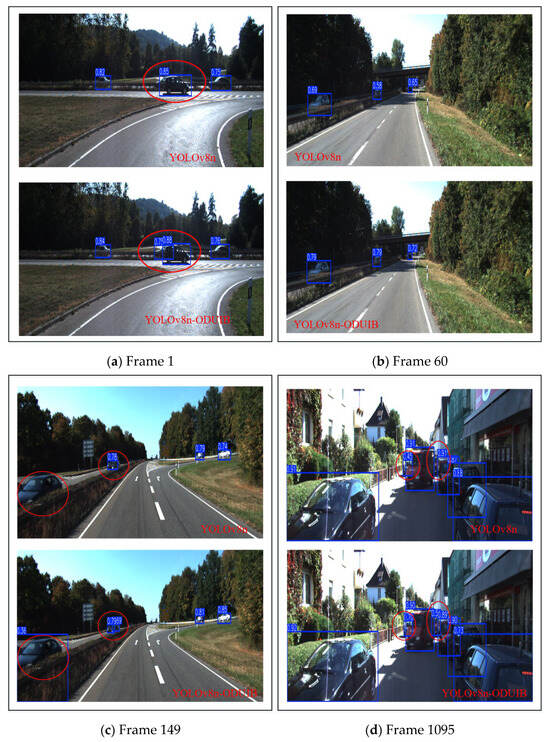

Figure 8 presents a visual comparison of object detection results between the original YOLOv8n model and the proposed YOLOv8n-ODUIB model. Four scenarios were used to evaluate the recognition performance of the dynamic object. In Figure 8a, compared to the detection result of the original YOLOv8n model, the vehicle in the bottom-left corner was successfully detected by the proposed algorithm, and the detection confidence for the other vehicles was enhanced by the proposed algorithm. In Figure 8b, although the dynamic vehicles are in the shade, the detection confidence of these vehicles has been significantly improved by the proposed algorithm, with the maximum confidence improvement reaching 36.2%. In Figure 8c, a dynamic vehicle is occluded by other vehicles. The original YOLOv8n model fails to recognize the occluded vehicle, while the proposed algorithm successfully detects it with a confidence of 0.75. In Figure 8d, there are many vehicles, and two vehicles are severely occluded that are marked with the red box. Only one occluded vehicle is detected by the original YOLOv8n model with a confidence of 0.45, whereas both occluded vehicles are detected with higher confidence by the proposed YOLOv8n-ODUIB model. As shown in Figure 7, the proposed YOLOv8n-ODUIB model exhibits a clear advantage in dynamic objects detection of occlusion scenarios. Specifically, it demonstrates significantly improved accuracy in detecting partially occluded objects, particularly vehicles that are partially hidden by other objects or scene elements.

Figure 8.

The visual comparison of object detection results between the original YOLOv8n model and the proposed YOLOv8n-ODUIB model.

4.2. The Performance Evaluation of Pose Estimation Based on the KITTI Dataset

The KITTI dataset, jointly released in 2012 by the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and the Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago, is a widely recognized benchmark for evaluating algorithms in outdoor driving environments. To assess the accuracy and robustness of the proposed YSAG-VINS system under purely visual conditions in dynamic environments, three high-dynamic sequences from the KITTI dataset were selected for evaluation.

In this evaluation, the Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) is adopted as the primary metric to quantify the deviation between the estimated trajectory and the ground truth. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, a comparative analysis was performed between YSAG-VINS and the baseline VINS-Fusion system.

Table 4 summarizes the statistics of ATE result of the YSAG-VINS and VINS-Fusion systems for the three KITTI sequences. In Table 4, the RMSE, mean and standard deviation (STD) of the YSAG-VINS for the 0930-0027 sequence are 0.5795 m, 0.5442 m, and 0.1991 m, representing improvements over VINS-Fusion of 49.71%, 50.50%, and 55.47%, respectively. The most substantial performance gain is observed in sequence 0930-0033, where the YSAG-VINS reduces the RMSE, mean, and STD by 61.26%, 61.17%, and 61.45%, resulting in final values of 2.2445 m, 1.8391 m, and 1.2866 m, respectively. For the 0930-0034 sequence, the RMSE, mean and STD of the proposed algorithm are 1.4945m, 1.3281m and 0.6854m, respectively, and the improvement rate achieves 43.05% (RMSE), 34.19% (mean), and 33.73% (STD) compared to VINS-Fusion. These experimental results clearly demonstrate that the proposed YSAG-VINS system significantly enhances absolute pose estimation accuracy compared to VINS-Fusion, particularly in dynamic outdoor scenarios where conventional visual-inertial methods may struggle with moving objects and occlusions.

Table 4.

The statistics of ATE result of the YSAG-VINS and VINS-Fusion systems for the three KITTI sequences (m).

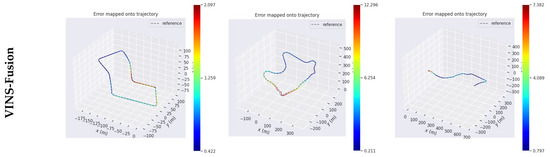

In Figure 9, the legend on the right indicates the position error. For the three KITTI sequences, the proposed algorithm significantly reduced the maximum position errors compared to the VINS-Fusion method. Specifically:

Figure 9.

The absolute trajectory poses error of the VINS-Fusion and YSAG-VINS algorithm for the KITTI dataset.

The minimum position errors were also reduced by the proposed algorithm, reaching 0.184 m, 0.049 m, and 0.316 m for Figure 9a,b, and Figure 9c, respectively.

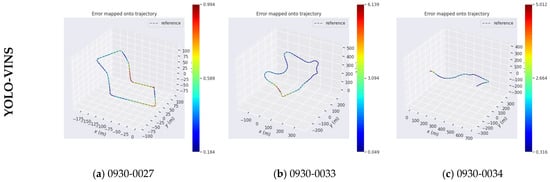

Figure 10 is the time series of trajectory for the VINS-Fusion and YSAG-VINS algorithm in the X, Y, and Z directions. In Figure 10a–c the green curve represents the trajectory sequence of the proposed algorithm, and the blue curve is that of VINS-Fusion. The proposed algorithm and the VINS algorithm exhibit great consistency with the ground truth trajectory in the X and Z directions. In the Y direction, the position trajectory of the VINS algorithm shows a larger deviation from the ground truth compared to the proposed algorithm.

Figure 10.

The timeseries of trajectory for the VINS-Fusion and YSAG-VINS algorithm in the X, Y, and Z directions.

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed YSAG-VINS system, we conducted a comparative analysis with two state-of-the-art SLAM systems, VDO-SLAM and Dynamic-VINS [38], specifically designed for dynamic environments. Table 5 is the RMSE statistics of ATE result of YSAG-VINS and the two baseline methods across multiple KITTI sequences. In Table 5, YSAG-VINS consistently outperforms both VDO-SLAM and Dynamic-VINS across all tested sequences. Compared to VDO-SLAM and Dynamic-VINS, the RMSE by the proposed algorithm is improved by 30.4% and 26.8%, respectively, for the 0930-0027 sequence. For the sequences 0930-0033 and 0930-0034, the RMSEs of Dynamic-VINS are 2.4356 m and 1.5864 m, respectively. The accuracy is slightly improved by VDO-SLAM, while the proposed algorithm obtains the optimal RMSEs for both datasets, achieving 2.2445 m and 1.4945 m, respectively. These results indicate that the proposed YSAG-VINS system is highly effective to handle feature point tracking in dynamic scenes, thereby achieving more accurate pose estimation in challenging environments.

Table 5.

Result of the RMSE of ATE result for the YSAG-VINS and VINS-Fusion systems on the three KITTI sequences (m).

4.3. The Performance Evaluation of Pose Estimation Based on the M2DGR and M2UD Datasets

To further evaluate the pose estimation performance of the proposed algorithm in dynamic environments, additional experiments were conducted on sequences from the M2DGR and M2UD datasets. Specifically, the rotation_01 sequence from the M2DGR dataset, which includes dynamic objection in outdoor scenes, and the Urban_02, and Urban_03 sequences from the M2UD dataset were used. The VINS-Fusion, DynaVINS and the proposed algorithm were used to process these datasets. The ATE between the estimated trajectory and the ground-truth trajectory was adopted as the metric to evaluate the pose estimation accuracy. Table 6 is the statistics of ATE result for the three algorithms.

Table 6.

The statistics of ATE result of the YSAG-VINS and VINS-Fusion systems for the three KITTI sequences (m).

In Table 6, the RMSE, Mean and STD of the DynaVINS and YSAG-VINS are better than that of the VINS-Fusion for all the datasets. Compared to VINS-Fusion, the maximum improvement rates of RMSE for the DynaVINS and YSAG-VINS are 16.89% and 29.82%, respectively, and the average improvement rates are 9.15% and 17.01%, respectively. Compared to DynaVINS, the RMSEs of the proposed algorithm are improved by 15.56%, 9.72% and 13.39% for the three sequences.

4.4. Validation of the Adaptive Threshold Strategy

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive threshold strategy in dynamic feature point selection, we conducted comparative experiments on the KITTI, M2DGR, and M2UD datasets to evaluate the localization accuracy of the SLAM system. The experiments covered typical dynamic objects such as vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists, while also accounting for variations in scene complexity and dynamic levels. The control group employed the fixed threshold ranges used in previous works, such as SG-SLAM [25], to compare the performance under different threshold settings.

where denotes the initial threshold, typically set in the range of [0.01, 0.1] pixels, while represents the prior weight determined by the dynamic objects identified through semantic information; a higher object motion probability corresponds to a larger value. As an example, in [25], the prior weight is set within the range of [1, 5]. denotes the final threshold for determining dynamic objects, which is computed by combining the initial threshold and the prior weight . In the control group of this study, the threshold is set according to the maximum dynamic probability, in order to fully evaluate the performance of the fixed-threshold strategy under highly dynamic conditions, resulting in the threshold value:

To ensure the fairness of the experiments, the control group using the Fixed Threshold Strategy also employed the semantic feature selection method proposed in this work, with the threshold set to the initial value . The experimental results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

The statistics of ATE result of the performance Comparison of the Our Method and Fixed Threshold Strategy (m).

Table 7 presents the quantitative comparison between the Fixed Threshold Strategy and the proposed adaptive threshold method across multiple sequences. For sequence 0930-0033, the Fixed Threshold Strategy achieves an RMSE of 3.5631, a mean error of 2.7781, and a standard deviation of 1.7369, whereas the adaptive threshold method achieves an RMSE of 2.2445, a mean error of 1.8391, and a standard deviation of 1.2866, corresponding to reductions of approximately 37%, 34%, and 26%, respectively. Across all other tested sequences, the adaptive threshold consistently achieves lower RMSE, mean, and standard deviation values.

These quantitative results confirm that the proposed method improves feature selection accuracy and system localization stability, demonstrating clear advantages over the Fixed Threshold Strategy, particularly in highly dynamic environments.

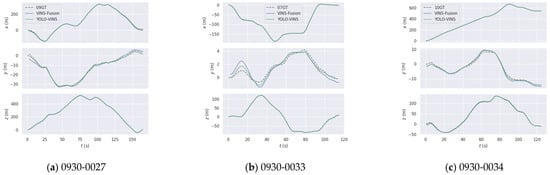

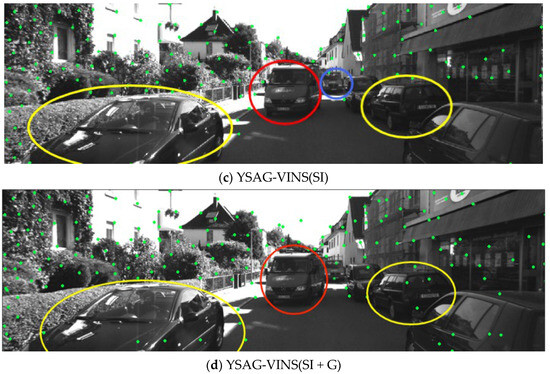

4.5. The Effectiveness Evaluation of Dynamic Feature Removal Strategy

The proposed YSAG-VINS system integrates enhanced semantic information with geometric methods to remove dynamic features, thereby leveraging the complementary strengths of both approaches. To evaluate the effectiveness of this semantic-geometric fusion strategy, and to analyze the individual contributions of its component, ablation experiments were conducted on three dynamic sequences from the KITTI dataset. Figure 11 presents the experimental results of dynamic feature removal across four different configurations:

Figure 11.

The experimental results of dynamic feature removal for the four Groups.

- VINS-Fusion (baseline);

- YSAG-VINS (S), which utilizes the original YOLOv8n model for semantic-based feature removal;

- YSAG-VINS (SI), which employs the improved semantic detection model proposed in this work;

- YSAG-VINS (SI+G), the full pipeline that integrates both the improved semantic model and adaptive geometric constraints.

In Figure 11a, the feature points extracted by VINS-Fusion do not account for dynamic and potential dynamic objects in the scene. As a result, the extracted feature points come from static objects, dynamic objects, and potential dynamic objects. The feature points extracted from dynamic objects will affect the system’s position estimation accuracy. Figure 11b shows the result of the feature points extraction by YSAG-VINS (S) that the semantic information from the original YOLOv8n model is used. The dynamic objection (marked in red cycle) and most potential dynamic objects are identified, while one potential dynamic object marked in blue cycle is still undetected. The feature points from the identified dynamic and potential objects are removed, while some feature points are extracted from the undetected potential dynamic object. Figure 11c is the result of the feature points extraction by YSAG-VINS (SI), and the undetected potential dynamic object in Figure 11d is also detected by the improved semantic model. The feature points from the dynamic and potential dynamic objects are successfully removed. However, in scenes with a large number of potential dynamic objects, removing all the feature points of potential dynamic objects will result in an insufficient number of usable feature points, thereby affecting the accuracy and stability of the system’s position estimation. Figure 11d is the result of the feature points extraction by the proposed algorithm (YSAG-VINS (SI+G)), and all the dynamic and potential dynamic objects are detected. For the proposed algorithm, the feature points from dynamic objects are removed, while the feature points from robust potential dynamic objects are retained as much as possible. This will enable more reliable feature points to be extracted from the scene, thereby enhancing the reliability of the system’s position estimation.

These results validate the effectiveness and necessity of combining semantic and geometric constraints, and highlight the critical role of the improved semantic model in achieving precise and robust dynamic feature suppression in real-world environments.

Table 8 is the statistics of ATE result for the four Groups with the different strategy of dynamic feature removal. In Table 8 the accuracy of pose estimation is significantly enhanced when the improved semantic constraint (SI) strategy is introduced into VINS. For the three sequences, compared to VINS-Fusion, the proposed SI-based method achieves 19.09%, 54.10% and 34.19% reduction in RMSE, indicating a substantial improvement in pose estimation. When compared to YSAG-VINS(S) which relies solely on the original YOLOv8n model for semantic segmentation, the improved semantic model yields an additional 9.81%, 33.13%, and 14.75% reduction in RMSE for the three sequences, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements. Furthermore, by incorporating geometric information, the proposed algorithm YSAG-VINS(SI+G) leads to a further 38.83%, 15.55% and 13.46% improvement in RMSE over the YSAG-VINS(SI).

Table 8.

Result of ATE for the four Groups with different strategy of dynamic feature removal (m).

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted paired t-tests on the RMSE metric across three sequences. The paired t-test is formulated as follows:

where denotes the difference in RMSE between two compared methods on the -th sequence, is the mean of these differences, and is the number of paired samples. The denominator corresponds to the standard error of the mean difference.

The results summarized in Table 9 indicate that all proposed YSAG-VINS configurations significantly outperform the baseline VINS-Fusion.

Table 9.

Paired t-test results on RMSE across three KITTI sequences.

In Table 9, it can be observed that all proposed YSAG-VINS configurations outperform the baseline VINS-Fusion with statistical significance. Specifically, YSAG-VINS(S) shows a significant improvement over VINS-Fusion (t = 4.53, p = 0.045 < 0.05), while YSAG-VINS(SI) achieves an even higher level of significance (t = 6.40, p = 0.023 < 0.05). Furthermore, YSAG-VINS(SI+G) demonstrates a highly significant improvement compared to the baseline (t = 10.9, p = 0.008 < 0.01).

When comparing different configurations within YSAG-VINS, the improvement of YSAG-VINS(SI) over YSAG-VINS(S) does not reach statistical significance (t = 2.81, p = 0.106). This is mainly because both methods adopt a purely semantic strategy, which indiscriminately removes all feature points within the detected semantic bounding boxes. Since YSAG-VINS(SI) has higher detection accuracy than YSAG-VINS(S), it tends to identify more objects, including some static ones. As a result, more feature points are removed, leading to a smaller relative performance gain compared with YSAG-VINS(S).

However, adding adaptive geometric constraints (G) to YSAG-VINS(SI) leads to a statistically significant performance enhancement (t = 6.55, p = 0.022 < 0.05), highlighting the critical role of the global constraint module in improving overall system accuracy.

This additional gain illustrates the synergistic effect of combining semantic perception with adaptive geometric constraint, effectively mitigating cumulative drift and enhancing the stability and robustness of the estimated trajectory in dynamic environments.

4.6. Timing Analysis

The speed of a SLAM system directly affects the efficiency of executing more complex tasks. Therefore, we evaluated the average processing time of per frame for the proposed YSAG-VINS and compared it with other systems. The systems of VINS-Fusion, DynaVINS, Dynamic-VINS, VDO-SLAM, YSAG-VINS(S), YSAG-VINS(SI) and the proposed YSAG-VINS(SI+G) are used to analyze the computational performance. These systems are operated in the hardware platform Intel i5-13500H, Nvidia RTX4050(6G). Table 10 is the average processing time of per frame for these compared systems.

Table 10.

The processing time of per frame for these compared systems (ms).

In Table 10, among the compared methods, VDO-SLAM incurs the highest time cost due to its reliance on a pixel-level semantic segmentation network, which significantly increases per-frame computational overhead. In contrast, the proposed YSAG-VINS employs a dedicated object inference thread and adopts TensorRT-based model semi-parametrization techniques to effectively improve processing speed, and the per-frame processing time is 37.75ms. This reflects that the proposed YSAG-VINS achieves an effective trade-off between semantic accuracy, pose estimation accuracy and real-time performance.

5. Discussion

The proposed YSAG-VINS system demonstrates significant advancements in addressing the long-standing challenges of SLAM in dynamic environments, particularly in terms of robustness and localization accuracy. Existing dynamic SLAM methods still face several limitations: first, when dynamic objects are occluded, semantic information can be incorrectly obtained, leading to errors in dynamic feature removal [26,27,28]; second, traditional geometry-based methods with fixed thresholds cannot accurately identify and remove dynamic objects in complex outdoor scenes, which reduces localization accuracy [20,25,26,27,28]. In addition, these methods often have high computational costs, making deployment on resource-constrained platforms challenging.

Regarding neural network architecture design, several findings from this study are generalizable: full-dimensional dynamic convolution effectively captures multi-scale, context-aware features; the UIB-enhanced C2f module demonstrates that balancing information bottlenecks with feature fusion can improve feature discrimination while maintaining computational efficiency; and strategies for multi-module integration and context enhancement provide useful guidance for other VSLAM or dynamic perception systems, especially in scenarios requiring both high accuracy and real-time performance. These findings are consistent with prior studies on efficient CNN design and embedded vision tasks [19,21], further validating the effectiveness of context-aware features and feature fusion strategies in improving system robustness and accuracy. For researchers in the field, this study suggests focusing on multi-scale context modeling, balancing information bottlenecks and feature fusion, and controlling computational cost to achieve both performance and efficiency in dynamic scene understanding and VSLAM systems.

YSAG-VINS addresses these limitations by introducing full-dimensional dynamic convolution and an improved UIB-enhanced C2f module into the object detection framework, which enhances feature representation and improves the extraction of salient visual cues. Combined with an optimized YOLOv8 detector trained on the BDD100K dataset, the system achieves a balanced trade-off between high detection accuracy and real-time inference capability. Furthermore, integrating semantic information into the VINS-Fusion framework and employing a dynamic suppression strategy based on epipolar constraints effectively mitigates the negative impact of dynamic objects. This semantic-geometric fusion strengthens system resilience in complex scenarios, ensuring reliable pose estimation where existing dynamic SLAM methods often fail.

Experimental evaluations on the KITTI, M2DGR, and M2UD datasets show that YSAG-VINS consistently outperforms robust baselines in pose accuracy and resilience to dynamic objects. To improve clarity, key results can be summarized in concise comparative tables or figures, highlighting improvements without overwhelming the reader with numerical details.

6. Conclusions

To address the limitations of conventional SLAM systems in dynamic environments, particularly their insufficient robustness and localization accuracy, this paper proposes YSAG-VINS, a real-time dynamic semantic visual-inertial SLAM system tailored for such challenging conditions. First, in the object detection module, we enhance the standard convolution layers with full-dimensional dynamic convolution and improve the C2f module with a UIB structure. These improvements enable the neural network to more effectively extract channel-wise features, dynamically adjust inter-channel dependencies, and capture salient visual information. As a result, the detection model achieves better feature representation and training accuracy. The improved YOLOv8 neural network is subsequently trained, validated, and tested on the BDD100K dataset, yielding a model that balances high detection accuracy with real-time performance.

Subsequently, the optimized YOLOv8 detector is integrated into the VINS-Fusion framework to provide prior semantic information. A dynamic suppression strategy, grounded in epipolar geometry constraints, is employed to eliminate feature points associated with dynamic objects. This semantic-geometric fusion approach significantly enhances the system’s robustness, accuracy, and real-time capability in dynamic scenes.

Extensive experiments validate the effectiveness of the proposed system. In particular, evaluations on three sequences from the KITTI dataset demonstrate that YSAG-VINS reduces the RMSE of trajectory estimation by 43.05% to 61.26% compared to the VINS-Fusion method. Additionally, the system achieves competitive inference speed, making it well-suited for real-world applications where both precision and efficiency are critical.

However, experimental evaluations also reveal certain limitations. The effectiveness of YSAG-VINS is closely tied to the quality of semantic information, which may degrade in environments with poor visibility or underexposed imagery. In such cases, the robustness of object detection can be compromised, leading to less reliable feature suppression and, consequently, reduced localization accuracy. Moreover, although the system achieves competitive real-time performance, the computational cost of integrating an enhanced deep learning detector could pose challenges for deployment on resource-constrained platforms. Future work will focus on addressing these limitations by exploring lightweight yet robust network architectures for semantic extraction, as well as adaptive strategies that can dynamically adjust the reliance on semantic information depending on scene quality. Additionally, extending the framework to incorporate temporal semantic consistency across frames may further mitigate detection failures in visually degraded conditions, paving the way for broader applicability of YSAG-VINS in real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.; methodology, K.W.; validation, X.W.; formal analysis, Y.N. and W.S.; investigation, S.W.; resources, D.C.; data curation, R.Y.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant numbers ZR2022QD108, ZR2024QD186 and ZR2022MD103); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 42204011 and 42374049).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SLAM | Simultaneous localization and mapping |

| ODConv | Omni-dimensional dynamic convolution |

| C2f | Concatenate and fuse |

| UIB | Unified inverted bottleneck |

| SGD | Stochastic gradient descent |

| mAP@0.5 | mean average precision at IoU threshold = 0.5 |

| mAP@0.5:0.95 | mean average precision across IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 |

| Param | parameter count |

| GLOPs | Giga Floating Point Operations per Second |

References

- Durrant-Whyte, H.; Bailey, T. Simultaneous localization and mapping: Part I. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2006, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Murray, D. Parallel tracking and mapping for small AR workspaces. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Nara, Japan, 13–16 November 2007; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An open-source SLAM system for monocular, stereo, and RGB-D cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 13 May–7 June 2014; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rosinol, A.; Abate, M.; Chang, Y.; Carlone, L. Kimera: An open-source library for real-time metric-semantic localization and mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 1689–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. VINS-Mono: A robust and versatile monocular visual-inertial state estimator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large-scale direct monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Cham, Switzerland, 8–11 September 2014; pp. 834–849. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. OVD-SLAM: An online visual SLAM for dynamic environments. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 13210–13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Tao, S.; Long, Y. Dynamic SLAM: A visual SLAM in outdoor dynamic scenes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Guo, L.; Gao, H.; You, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z. YOLO-SLAM: A semantic SLAM system towards dynamic environment with geometric constraint. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 6011–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Qian, C.; Wu, T.; Hu, X.; Duan, F.; Ye, X. A dynamic scene vision SLAM method incorporating object detection and object characterization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A versatile and accurate monocular SLAM system. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerl, C.; Sturm, J.; Cremers, D. Dense visual SLAM for RGB-D cameras. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Tokyo, Japan, 3–8 November 2013; pp. 2100–2106. [Google Scholar]

- Alcantarilla, P.F.; Yebes, J.J.; Almazán, J.; Bergasa, L.M. On combining visual SLAM and dense scene flow to increase the robustness of localization and mapping in dynamic environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Saint Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; pp. 1290–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.; Liu, H.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, G.; Bao, H. Robust Monocular SLAM in dynamic environments. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Adelaide, Australia, 1–4 October 2013; pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, S. Towards dense moving object segmentation based robust dense RGB-D SLAM in dynamic scenarios. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV), Singapore, 10–12 December 2014; pp. 1841–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Bescos, B.; Fácil, J.M.; Civera, J.; Neira, J. DynaSLAM: Tracking, mapping, and inpainting in dynamic scenes. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 4076–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runz, M.; Buffier, M.; Agapito, L. MaskFusion: Real-time recognition, tracking and reconstruction of multiple moving objects. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Munich, Germany, 16–20 October 2018; pp. 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Dong, N.; Li, D. A real-time dynamic object segmentation framework for SLAM system in dynamic scenes. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolya, D.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, F.; Lee, Y.J. YOLACT: Real-time instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, South Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 9157–9166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Henein, M.; Mahony, R.; Ila, V. VDO-SLAM: A visual dynamic object-aware SLAM system. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.11052. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, T.; Zhang, R.; Yi, X. PLD-SLAM: A new RGB-D SLAM method with point and line features for indoor dynamic scene. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Zhu, X.; Dong, D. DE-SLAM: SLAM for highly dynamic environment. J. Field Robot. 2022, 39, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Fang, M.; Ma, L. DHP-SLAM: A real-time visual SLAM system with high positioning accuracy under dynamic environment. Displays 2025, 84, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D. SG-SLAM: A real-time RGB-D visual SLAM toward dynamic scenes with semantic and geometric information. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Lim, H.; Lee, A.J.; Myung, H. DynaVINS: A visual-inertial SLAM for dynamic environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 11523–11530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, F.; Wu, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, G.; Liu, N. COEB-SLAM: A robust VSLAM in dynamic environments combined object detection, epipolar geometry constraint, and blur filtering. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 26279–26291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. A real-time visual SLAM based on semantic information and geometric information in dynamic environment. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, Z.; He, T. Visual simultaneous localization and mapping optimization method based on object detection in dynamic scene. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, A.; Yao, A. Omni-dimensional dynamic convolution. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.07947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Leichner, C.; Delakis, M.; Fornoni, M.; Luo, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Banbury, C.; Ye, C.; Akin, B.; et al. MobileNetV4: Universal models for the mobile ecosystem. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Cham, Switzerland, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G. Epipolar Geometry in Stereo, Motion and Object Recognition; Computational Imaging and Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Xian, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Madhavan, V.; Darrell, T. BDD100K: A diverse driving dataset for heterogeneous multitask learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 18–24 June 2020; pp. 2636–2645. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The KITTI dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Li, A.; Li, T.; Yu, W.; Zou, D. M2DGR: A multi-sensor and multi-scenario SLAM dataset for ground robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 7, 2266–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Shao, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, T. M2UD: A multi-model, multi-scenario, uneven-terrain dataset for ground robot with localization and mapping evaluation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12387. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Y. DynamicVINS: Visual-inertial localization and dynamic object tracking. In Proceedings of the China Automation Congress (CAC), Beijing, China, 10–12 October 2022; pp. 6861–6866. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).