Abstract

Background: Clear aligner therapy (CAT) is widely used, yet safe per-stage rotation in periodontally compromised incisors remains uncertain. This study aims to define tooth position and support specific rotation limits by quantifying periodontal ligament (PDL) stress using finite element analysis (FEA). Methods: Four 3D FEA models (healthy; Stage I–III periodontitis) of maxillary central and lateral incisors were built in ANSYS 2024 R2. Mesial rotations of 1.25–3.0° were imposed on single teeth with a 0.5 mm PET-G aligner and attachments; the posterior segment was fixed. The PDL was modeled as nonlinear. Primary outcomes were peak PDL von Mises stress and total deformation; the mesh convergence was <5%. Results: At 3.0°, the healthy model produced 270.87 kPa (central) and 641.73 kPa (lateral). Stage I plateaued beyond ≈1.75° at ≈221.53 kPa (central) and ≈406.71 kPa (lateral). Stage II showed low central stress (86.20 kPa) but high lateral stress (2763.1 kPa) with greater deformation. Stage III yielded 825.39 kPa (central) and 1321.6 kPa (lateral). Deformation increased from <0.005 µm to ≈8.37 µm for centrals and from <0.005 µm to ≈11.139 µm for laterals with diminishing periodontal support. Conclusions: Safe rotational staging depends on periodontal support and tooth type. The recommended per stage angles are as follows: centrals ≤2.5° in healthy, 1.75° in Stage I, ≤1.0° in Stages II and III; laterals ≤1.75°, ≤1.25°, and ≤1.0°, respectively.

1. Background

Clear aligner therapy (CAT) has gained substantial popularity owing to its aesthetics, comfort, and facilitation of oral hygiene. Beyond mild crowding, indications now extend to more complex problems, including Class II/III malocclusions and interdisciplinary care [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Patient-reported outcomes are generally favorable; CAT users often report less discomfort and fewer eating/speaking difficulties and show better oral health-related quality of life than those treated with fixed appliances [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], although some studies found only small differences between the two modalities [9,14].

CAT is also compatible with comprehensive periodontal care. In periodontally compromised patients, CAT has been associated with improvements in clinical attachment level, recession, mobility, and probing depth, and can be delivered safely when coordinated with periodontal therapy [15,16]; nevertheless, some tooth movements, particularly rotations (and especially in teeth with more circular crown morphology), remain less predictable when CAT is used [17].

Pathological tooth migration is common in periodontitis, and anterior teeth are susceptible to flaring, elongation, and spacing [18]. With periodontitis affecting a substantial proportion of adults [19], CAT protocols must be individualized to periodontal support, calibrating per-stage displacement to remain within safe tissue capacity.

Orthodontic tooth movement relies on mechanically mediated remodeling of the alveolar bone through the periodontal ligament (PDL), a viscoelastic tissue that modulates load transmission; excessive force risks hyalinization, root resorption, and anchorage loss, whereas insufficient force may be biologically ineffective [20,21]. Although an “optimal force” has been proposed conceptually as the lightest force that elicits a maximal biological response [22], within this biomechanical framework, force delivery with CAT is displacement-driven rather than force-controlled [23]. When a thermoformed tray is first seated, the programmed shape mismatch generates relatively high initial force moment systems [23,24] that then decay over hours to days because of polymer stress relaxation, intraoral temperature and humidity, and progressive seating of the tooth [25,26]; thermoforming itself also alters material properties [27]. Consequently, the forces from CAT are not directly comparable to the near constant unloading plateaus delivered by superelastic NiTi arch wires in fixed appliances [28]; by contrast, CAT typically delivers a high initial load that diminishes over time [25,26].

Finite element analysis (FEA) has become central to orthodontic biomechanics because it enables noninvasive estimation of stress/strain within dental and periodontal structures under controlled boundary conditions [29,30,31,32]. Prior FEA work demonstrated that alveolar bone height strongly modulates stress concentrations in anterior teeth (e.g., maxillary central incisor/canine), and underscored the relevance of time-dependent responses in the PDL and adjacent bone [29,30,31,32]. Clinically, stress magnitude matters: loads that are too low fail to stimulate adaptation, whereas excessive loads can precipitate necrosis and collateral damage [33,34,35]. In mandibular do nots, simulated bone loss amplifies stress concentrations during intrusion with inclination, underscoring the need to revise force systems in periodontally challenged patients [36].

Study aim: Clinically, rotational corrections in periodontally compromised adults can overload the cervical periodontal ligament (PDL), increasing risks of hyalinization and external apical root resorption; therefore, defining safe per-step rotation thresholds is necessary for clear, evidence-based staging in CAT. Despite the growing use of CAT in such cases, data on safe rotational per-stage for maxillary incisors across staged bone loss remain limited. Prior FEM work often modeled an intact or uniformly reduced periodontium without mapping to the 2017 AAP/EFP staging and frequently assumed a linear-elastic PDL; few studies translated stress fields into implementable, tooth- and stage-specific limits for step planning. This study uses FEA to evaluate PDL von Mises stress and tooth deformation during incremental rotational movements of maxillary central and lateral incisors under CAT, across staged periodontal support mapped to the 2017 AAP/EFP stages, employing a nonlinear PDL formulation to derive conservative tooth- and support-specific rotation steps that keep PDL stresses within predefined thresholds and inform evidence-based staging for patients with periodontitis [37,38].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geometry Acquisition, Model Construction, and Periodontal Conditions

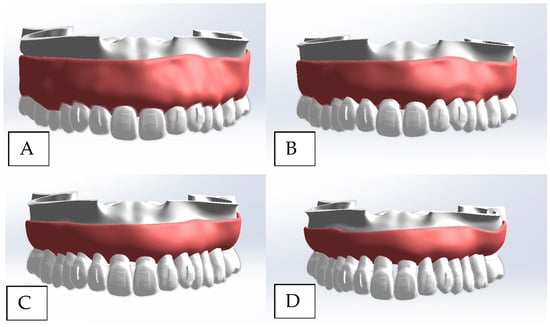

A three-dimensional finite element analysis (3D FEA) model of the maxillary arch was developed to evaluate stress distribution and tooth displacement during CAT-induced rotation of the maxillary central and lateral incisors across staged periodontal conditions. Patient-specific CBCT data were obtained from a completely dentate, periodontally healthy 29-year-old female. Anatomical reconstruction was performed in Mimics Research (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium), surface refinement in Geomagic Design X (Hexagon, Stockholm, Sweden), aligner/attachment design in exocad (exocad GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany), and final CAD assembly in SOLIDWORKS (Dassault Systèmes, Waltham, MA, USA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional CAD assembly model with CAT. Models’ construction and periodontal conditions. (A) Normal periodontal condition. (B) Stage I periodontitis. (C) Stage II periodontitis. (D) Stage III periodontitis.

CBCT acquisition: The scanning parameters included a voxel size of 0.25 mm, tube voltage of 120 kVp, current of 7 mA, a field of view of 16 cm (diameter) × 4 cm (height), and a scan time of 26.9 s; the volume was exported in DICOM format for downstream processing.

Ethics and consent: The study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Cyprus Health and Social Sciences University (KSTU/2024/312); written informed consent was obtained for the use of anonymized radiographic data.

Four models were generated in accordance with the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions (AAP/EFP) to represent escalating periodontal breakdown [37,38]. Periodontal staging followed the AAP/EFP framework; for finite-element parameterization>, we used only the severity components that map directly to geometry—interdental CAL at the site of greatest loss and radiographic bone loss (RBL) expressed as a percentage of root length from the CEJ. Bone loss was simulated by digitally reducing alveolar height on mesial, distal, palatal, and labial aspects using anatomical landmarks as references, while maintaining identical tooth-root morphology across all models to isolate the effect of support on stress distribution and kinematics. The periodontal staging and the global mesh statistics (nodes/elements) for each model are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Periodontal classification and mesh characteristics of the four models.

Simulation of bone loss (landmarking rule): Alveolar crest reduction was applied to mesial, distal, palatal, and labial aspects using anatomical landmarks while preserving identical tooth-root morphology across models. Operationally, alveolar height was determined by referencing CEJ-based lines and offset apically by 1.5/3.5/5.0 mm for Stages I–III, respectively; these offsets were chosen as representative anchors within the AAP/EFP %RBL bands (<15%, 15–33%, mid-third+), applied proportionally to each tooth’s CBCT-measured CEJ–apex root length (i.e., no fixed millimeter thresholds were implied). Stage IV was excluded from simulation. In the AAP/EFP scheme, Stage IV shares the same RBL severity as Stage III and differs primarily by functional complexity and tooth loss of ≥5 teeth due to periodontitis.

2.2. Aligner and Attachment Modeling: Material Properties

The CAT was modeled as a 0.5 mm PET-G thermoplastic shell closely adapted to the clinical crown contours and gingival margins of the anterior teeth. To standardize rotational coupling and minimize unintended tipping or loss of tracking, vertical rectangular attachments (4 × 2 × 1 mm) were placed on the labial surfaces of the maxillary central and lateral incisors with the long axis oriented vertically. The aligner tooth attachment assembly corresponds to the CAD configuration shown in Figure 1.

All structural components—cortical bone, cancellous bone, teeth, gingiva, attachments, and the aligner—were treated as homogeneous, isotropic, and linearly elastic. The periodontal ligament (PDL) was modeled as nonlinear elastic to approximate its physiological (viscoelastic-like) response under dynamic loading. A uniform PDL thickness of 0.25 mm was assigned across all models. The elastic constants (Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio) used for each structure are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The properties of the materials used in the study.

2.3. Meshing and Convergence Test

Finite element meshing was performed in ANSYS 2024 R2 using tetrahedral elements. A fine element size of approximately 0.20 mm was applied in regions expected to experience high stress gradients (specifically the PDL, root surfaces, and the alveolar crest), while a comparatively coarser mesh was adopted in non-critical regions (gingiva, aligner) to balance accuracy and computational convergence vs. time frame. Tetrahedral mesh statistics for each periodontal model are reported in Table 1.

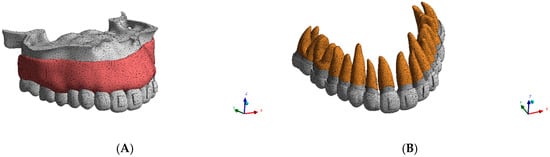

Mesh quality was verified visually and through solver diagnostics to ensure appropriate element shapes for nonlinear solution stability. A mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted by refining the critical element size from 0.30 mm to 0.15 mm. Convergence testing was performed by comparing results across successive refinements, and convergence was confirmed when the variation in peak PDL von Mises stress was <5%, while corresponding displacement values varied by <2% across representative load steps. These thresholds were adopted as convergence criteria to ensure the reliability of stress and displacement predictions. The final meshing configuration is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(A) Mesh of the maxilla. (B) Mesh of the maxillary teeth and periodontal ligament.

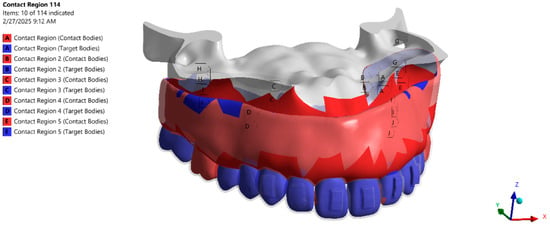

2.4. Boundary Conditions, Contact Definitions, Loading Protocol, and Software

To prevent rigid body motion, the posterior maxillary segment was fully constrained in all degrees of freedom. The PDL–bone and root–PDL interfaces were modeled as bonded to represent physiological attachment, with relative compliance arising from the PDL material properties. Frictional surface contact with the coefficient μ = 0.3 was assigned at the aligner–tooth and aligner–attachment interfaces. Composite resin attachments were modeled as perfectly bonded to enamel. Contact pairs and boundary constraints are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Contact interfaces between CAD bodies (aligner tooth/attachment; tooth–PDL; PDL–bone) and fixed supports.

A prescribed rotation about the tooth’s long axis was applied to the maxillary central and lateral incisors in six steps 1.25°, 1.50°, 1.75°, 2.00°, 2.50°, and 3.00° in the mesial direction (toward the midline). We performed a nonlinear transient analysis with rotational displacement ramped over normalized pseudo-time subdivided into 100,000 increments. For each step, the PDL von Mises stress distribution and tooth total deformation were extracted, and the maximum PDL stress at each angle was recorded for within-model dose response and between-model comparisons; all pre-/post-processing and solutions were carried out in ANSYS 2024 R2 (Ansys Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA).

2.5. Model Validation

To verify the accuracy of the finite element model, validation was performed by comparing the simulated von Mises stress on the central incisor under a 1° angulation load with published data. For Model 1 (normal bone), the current simulation predicted a peak von Mises stress of 108.2 MPa, whereas the reference value reported by Li et al. (2023) [41] was 105.3 MPa. The error tolerance of 2.7% falls within the acceptable range for finite element model validation, supporting the reliability of the meshing strategy, material properties, and boundary conditions employed in this study.

3. Results

3.1. PDL Stress Distribution

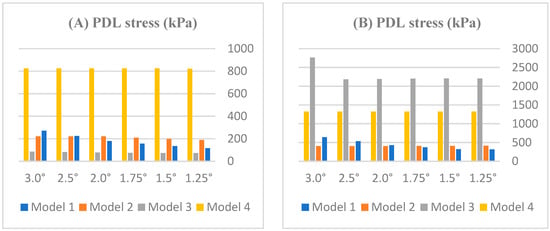

PDL von Mises stress was quantified across four periodontal models (Models 1–4) and for both incisors across mesial rotation angles of 1.25–3.0° (Table 3; Figure 4 and Figure 5). Overall, stress increased as periodontal support decreased, and the stress of the lateral incisor exceeded that of the central incisor at matched angles. Within-model angular dependence was evident in Models 1 and 4, whereas a plateau emerged in Model 2 beyond ≈1.75°; Model 3 showed a tooth-type divergence with low central and high lateral values.

Table 3.

Von Mises stresses induced on PDL (kPa).

Figure 4.

Effect of rotation angle on PDL stress (kPa) in (A) central and (B) lateral incisors across periodontal models (Models 1–4).

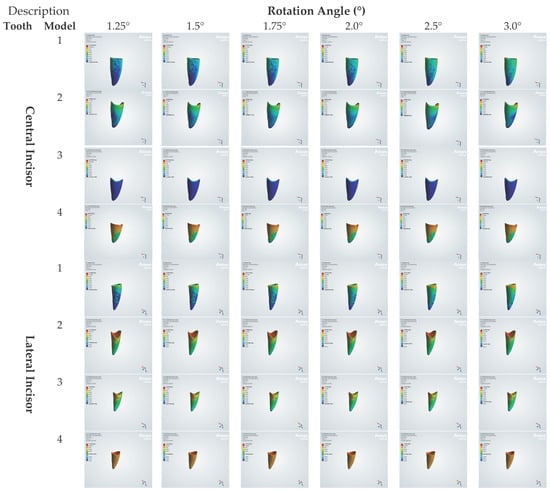

Figure 5.

Von Mises stresses induced on PDL (kPa).

By model: In Model 1 (healthy), the central incisor increased nearly linearly from ≈117 kPa at 1.25° to ≈271 kPa at 3.0°, whereas laterals reached higher peaks within the same model (e.g., ≈642 kPa at 3.0°). In Model 2 (mild loss), both teeth stabilized beyond ≈1.75°, near ≈222 kPa (central) and ≈407 kPa (lateral), with minimal change between 2.0 and 3.0°. In Model 3 (moderate loss), centrals remained low (≈86.2 kPa), whereas laterals were substantially higher (≈2207 kPa at 1.25°, increasing to ≈2763 kPa at 3.0°). In Model 4 (severe loss), peaks were largest overall, reaching ≈822 kPa (central) and ≈1322 kPa (lateral) at 3.0°.

3.2. Total Deformation on Teeth

Across all models and angles (1.25–3.0°), total deformation (µm) increased with rotation and decreased with periodontal support; the lateral incisor consistently exhibited larger deformations than the central incisor at matched activations (Table 4; Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Table 4.

Total deformation induced on the central and lateral incisors (µm).

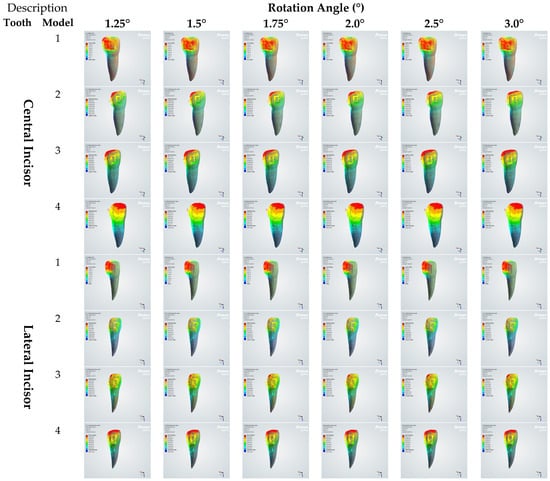

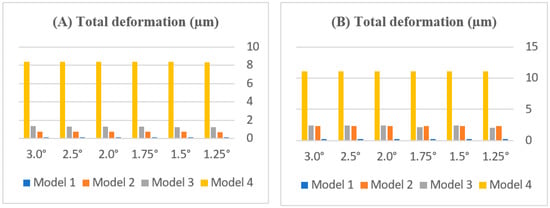

Figure 6.

Total deformation induced on central and lateral incisors (µm).

Figure 7.

Effect of rotation angle on total deformation (µm) in (A) central and (B) lateral incisors across periodontal models (Models 1–4). Note: Model 1 is not visible in the graph because its deformation values are very low compared to those of the other models.

By model. In Model 1 (healthy), the total deformation was extremely small yet angle-dependent, remaining ≤0.005 µm across 1.25–3.0° (central ≤ 0.00467 µm; lateral ≈0.00502 µm at 3.0°). In Model 2 (mild loss), deformations flattened beyond ≈1.75°: the central plateaued at ≈0.76 µm, while the lateral stabilized near ≈2.30 µm with minimal change from 2.0 to 3.0°. In Model 3 (moderate loss), the central increased modestly with the angle (≈1.25 → 1.34 µm) but remained well below the lateral; the lateral showed a steeper early angle increase with midrange peaks ≈2.4 µm (≈1.5–2.0°), followed by a slight decline at higher angles. In Model 4 (severe loss), the deformations were the largest overall and plateaued early: central ≈8.37 µm and lateral ≈11.14 µm at 3.0°.

4. Discussion

4.1. PDL Stress Distribution and Rationale for Tooth-Specific Thresholds

A PDL stress plateau is early saturation of the response: the peak rises, then stabilizes despite further rotation. Cause: nonlinear stiffening with strain and physiologic damping that dissipates load; with support loss, the center of resistance shifts apically and spreads load. Practically, once the first damped plateau is reached, extra activation does not add proportional rotation and instead increases PDL area and time above the threshold [42]. Setting the central incisor PDL limit at 240 kPa is grounded in physiologic damping and the early plateau in our model. In vivo modal tests on maxillary centrals report damping ratios 0.091–0.240 (mean ≈0.146 ± 0.037), and dynamic FE of the same tooth shows that adding damping reduces the peak versus static and delays the time to peak, matching the decaying load profile of CAT. In our FEA (Model 2), the central’s PDL stress stabilizes at ≈221.53 kPa (2.0° to 3.0°), so we stage the initial rotation at or below this first plateau and adopt a conservative 240 kPa ceiling; applying the same rule to the lateral, an early maximum 412.58 kPa at 1.25° is followed by a shallow plateau ≈406.71 kPa (2.0° to 3.0°), so we adopt 400 kPa (Figure 4) [43].

Experimental and numerical evidence explains why lateral > central: human PDL DMA shows E′ = 0.808–7.274 MPa and E″ = 0.087–0.891 MPa with mid-root > cervical and centrals > laterals (p < 0.05), indicating greater storage and damping in centrals and, therefore lower, delayed peaks under transient loads; this matches our plateau findings [44]. Microscopically, the collagen-fiber volume fraction is graded (mid-root ≈63.1%, cervical ≈60.3%, apical ≈52.0%), and a fiber fraction-based hyperelastic model shows that higher fiber content increases transient tensile resistance; when rotation extends loading into the mid-root, local support and local stresses rise, reinforcing the lateral over central pattern [45,46].

There is no universal PDL pressure threshold, so we avoid claiming a single kPa “safe” value. Clear-aligner forces start high and then decay: thermoformed aligners (TFAs) at 0.10–0.30 mm activation show peaks 5.11–16.26 N and stabilized 4.60–15.30 N, while directly printed aligners (DPAs) show peaks 2.44–3.87 N and stabilized 0.73–1.69 N—high initial forces that drop markedly over time [24]. Independent in vitro studies likewise report pronounced force decay/stress relaxation in aligner systems and materials, with DPA showing larger decay than TFA and 14-day relaxation documented across materials [26,47]. Given geometry, contact area, and time dependence, local pressures therefore vary over time and a single kPa threshold is unrealistic. Accordingly, we target the initial damped peak/early plateau where the transient exceedance risk is greatest and set model-derived, tooth-specific thresholds: 240 kPa for central and 400 kPa for lateral. Clinically, we use the first damped plateau as the threshold to limit the initial over compression and reduce PDL area and time above that level while avoiding any claim of a universal kPa limit linked to hyalinization and root resorption risk.

4.2. Nonlinear Stress Redistribution with Progressive Bone Loss (Models 1–4)

In Model 1, PDL von Mises stress increased almost linearly with mesial rotation. For the maxillary central incisor, values increased from 117.33 kPa at 1.25° to 270.87 kPa at 3.0°; the lateral incisor exhibited a similar monotonic increase from 318.86 kPa at 1.25° to 641.73 kPa at 3.0° (Table 3). This orderly, near-linear escalation indicates efficient load transfer through an intact PDL and aligns with the observations of Middleton et al. regarding the behavior of undamaged periodontal tissues [32].

In Model 2, PDL von Mises stress showed an early rise followed by a clear plateau. For the central incisor, values increased from 189.24 kPa at 1.25° to 198.18 kPa at 1.5° and 209.25 kPa at 1.75°, then reached a stable plateau of 221.53 kPa from 2.0° through 3.0°. The lateral incisor showed a shallow decline that, likewise, stabilized: 412.58 kPa at 1.25°, 410.91 kPa at 1.5°, 408.80 kPa at 1.75°, settling at 406.71 kPa from 2.0° to 3.0° (Table 3). This plateau behavior is consistent with viscoelastic damping where the PDL dissipates energy and limits peak stresses, echoing experimental and modeling observations by Wu et al. [48] and Cai et al. [42] that mild displacements can be accommodated without progressive stress escalation.

In Model 3, the maxillary central displayed an apparently paradoxical reduction in peak PDL von Mises stress (Model 3 central = 86.20 kPa at 3.0°) relative to the healthy and mildly compromised models (Model 1 = 270.87 kPa, Model 2 = 221.53 kPa), despite an increased total displacement (central deformation: Model 3 = 1.340 µm vs. Model 1 = 0.00467 µm and Model 2 = 0.757 µm) (Table 3 and Table 4). This pattern is explained by the interaction of center of resistance migration with tooth geometry, which reduces the effective moment arm on the central after moderate alveolar loss, and the PDL’s nonlinear, rate-dependent constitutive behavior. Under displacement-driven loading, the central’s PDL elements operate in the low-stiffness “toe” region of the hyperelastic curve and exhibit marked viscoelastic relaxation, thereby accommodating larger kinematic response (increased rotation/displacement) while attenuating instantaneous von Mises peaks. By contrast, lateral PDL elements in Model 3 experience larger strains that engage the strain-stiffening branch of the constitutive law and show less relative relaxation, producing markedly higher and more sustained von Mises stresses (lateral Model 3 = 2763.1 kPa at 3.0°).

Sensitivity runs that linearize the PDL or remove viscous terms restore higher central peaks, confirming the dominant role of PDL nonlinearity and viscoelasticity in the observed load redistribution. These findings concur with prior reports linking alveolar bone loss to apical CR migration and altered moment/force behavior [49], and with experimental/numerical demonstrations of PDL nonlinear and viscoelastic responses under transient loading [44]. Consistent with this mechanism, the quantitative Model 3 pattern was tooth type-specific: the central stayed low, rising from 73.88 kPa at 1.25° to 86.20 kPa at 3.0°, whereas the lateral remained well above the allowable threshold (400 kPa) at all angles (2207.0 kPa at 1.25°, 2763.1 kPa at 3.0°; Table 3). Although the lateral curve is nearly flat between 1.25 and 2.5° (2207.0 → 2182.3 kPa; −1.1%), this “plateau” lies far above the allowable limit, with a late rise at 3.0° further increasing the overshoot. Accordingly, both teeth should be staged conservatively in Model 3: for laterals, there should be low-force, small-step rotation ≤ 1.0° per step with reinforced anchorage and mid-root attachments; for centrals, despite PDL stress remaining below the 240 kPa threshold, the increased total deformation (1.340 µm) under moderate support loss warrants similarly conservative steps (≤1.0° per step) to limit PDL peaks and avoid uncontrolled movements.

In Model 4, PDL von Mises stress was high and plateaued early across the rotation range: for the central incisor, it increased from 821.97 kPa at 1.25° to 825.39 kPa at 1.5°, then remained at 825.39 kPa through 3.0°; the lateral incisor showed a similarly flat profile (1321.5 kPa at 1.25°, 1321.6 kPa at 1.5°, and stable at 1321.6 kPa to 3.0°) (Table 3). At 3.0°, these magnitudes markedly exceeded healthy bone values in Model 1 (270.87 kPa central; 641.73 kPa lateral), corresponding to ≈3.047 higher for the central and ≈2.059 higher for the lateral, consistent with reports that severe periodontal bone loss concentrates stresses during tooth movement [36].

4.3. Comparison with Previous Finite Element and Clinical Studies: Clinical Implications for Aligner Staging

First, progressive periodontal bone loss was associated with increased tooth deformation and loss of anchorage, especially under rotational loads. Model 1 showed very little deformation (<5 µm), but Models 3 and 4 exhibited up to 20 times more displacement (≈11 µm in the lateral incisor). This manifested clinically as apical tipping (upward root displacement) and cervical buckling (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This atypical movement shifted local stress concentrations away from the PDL’s mid root damping zone, imposing excessive stress on the structurally weak apical collagen network [44] and creating a biomechanical “lever arm” that further exacerbated anchorage loss. The nonlinear stress redistribution observed in compromised models is consistent with FEA studies by Toms and Eberhardt [40], who showed that reduced alveolar support rendered the root’s fulcrum unstable, allowing the crown to continue to move freely even under light forces. In clinical settings, this resembles pathological tooth migration in patients with periodontitis [16,50], highlighting the necessity for lightweight rotational procedures (≤1.0°) in cases of severe bone loss to prevent irreparable PDL damage and tooth displacement.

Clinical translation and protocol—central vs. lateral incisors with alveolar bone loss: Building on the deformation and stress patterns (Figure 4 and Figure 7), this study supports a clinically risk-adapted approach to CAT. At matched angles and periodontal support, lateral incisors show greater rotational response and higher cervical PDL stress than centrals; therefore, per-step rotation should be smaller for laterals at each AAP/EFP-mapped stage [37,38]. For the central incisor, safe rotational angles were up to 2.5° in Model 1, ~1.75° in Model 2, and ≤1.0° in Models 3–4; for the lateral incisor, tolerances were ≤1.75° in Model 1, ≤1.25° in Model 2, and ≤1.0° in Models 3–4. As alveolar support declines (Models 2–4), the center of resistance shifts apically and cervical stress concentrates, justifying smaller steps and tighter activation control [31,39,40].

Clinically, one should begin with the smallest per-step rotation that keeps PDL stress within the conservative limits defined in this study, use crown attachments oriented to increase the rotational couple when indicated, and reassess tracking at short intervals; one should escalate only if tracking remains stable. Beyond the observed plateau, additional rotational activation yields diminishing deformation while disproportionately increasing cervical PDL stress; when stresses approach or exceed the conservative thresholds defined in this study, further activation represents over-treatment with greater risk than benefit, increasing the risk of PDL hyalinization and external apical root resorption.

In parallel with these clinical recommendations, the Invisalign® system (Align Technology, San Jose, CA, USA) allows a maximum of 3° of rotational movement per aligner stage in a low-anchorage pattern [51]. In regular clinical practice, nonetheless, the system’s default maximum values per stage do not depend on how the case is staged. For example, 2° is usually the limit for rotation [52]. Our finite element analysis demonstrates close agreement with this protocol under physiologic conditions for the central incisor, where rotational movements up to 2.5° remain within conservative biomechanical limits. In contrast, the lateral incisor exhibits a reduced tolerance: approximately 0.75° lower (≈1.75°). These observations underscore that although standard clinical parameters may be acceptable in healthy periodontal cases, they require adjustment in the presence of compromised periodontal support to mitigate excessive biomechanical loading and to preserve physiologically safe patterns of tooth movement.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, this FEA is idealized and derived from a single CBCT to isolate the effects of periodontal support and mechanics; accordingly, it may not fully capture patient-specific anatomical variability (e.g., differences in tooth morphology, PDL thickness, and alveolar bone density). Secondly, due to a lack of similar FEA studies, direct validation of our findings is limited, although general biomechanical trends align well with existing literature. Lastly, FEA-based results remain theoretical until confirmed through clinical trials; thus, future clinical validation is needed to ensure the practical relevance of the proposed recommendations.

Future clinical validation. We propose a prospective, risk-stratified clinical study to test conservative per-stage rotation limits across tooth types and arches over AAP/EFP periodontal stages, evaluating periodontal clinical indices (PI, BOP, PD, CAL), standardized radiographic alveolar bone-level change, external apical root resorption (EARR) on serial periapicals under principles, aligner tracking/achieved rotation, adverse events, and patient-reported comfort.

5. Conclusions

This finite element analysis indicates that safe per-stage rotational displacement with CAT depends on periodontal support and tooth type. For the maxillary central incisor, the limits were ≤2.5° in Model 1, ~1.75° in Model 2, and ≤1.0° in Models 3–4; for the lateral incisor, they were ≤1.75°, ≤1.25°, and ≤1.0°, respectively. Because outputs were computed using 0.25° angular increments up to 2.0° and 0.5° increments from 2.0° to 3.0°, these values should be interpreted as computational anchors rather than prescriptive targets. For clinical implementation, rounded, practical per-stage angles are appropriate—for example, with ~1 mm alveolar bone loss (Stage I) and stable periodontal control, up to 2.0° per stage for the maxillary central incisor and up to 1.5° for the lateral may be used; with greater bone loss, ≤1.0° per stage is advised.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.A.-l.; Methodology, A.G.A.-l. and R.L.T.; Formal analysis, A.G.A.-l., K.M.D. and O.Ö.; Writing—original draft, A.G.A.-l.; writing—review and editing, A.G.A.-l., O.Ö. and K.M.D.; supervision, K.M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Cyprus Health and Social Sciences University (KSTU/2024/312). No clinical procedures were conducted, and no identifiable patient data were used.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient provided written consent for the publication of their anonymized radiographic image included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for participation in this study and the use of their radiographic data in anonymized form.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mohamed Gamal Askar for his technical assistance in conducting the finite element analysis. The simulations were performed on a contractual basis, and the authors acknowledge his professional contribution to the modeling phase.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Nomenclature

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis. |

| PDL | Periodontal Ligament. |

| CAT | Clear aligner therapy. |

| CEJ | Cementoenamel Junction. |

| µm | Micrometer. |

| MPa | Megapascal (unit of stress). |

| kPa | Kilopascal (1000 kPa = 1 MPa). |

| Normal Periodontal Condition | Simulated model with full alveolar bone support. |

| Reduced Periodontal Support | Simulated model with decreased alveolar bone height (bone loss). |

| Optimal Displacement | Range of initial tooth displacement considered biomechanically favorable. |

| Maxillary Incisors | Upper front teeth (central and lateral) evaluated in this study. |

| Von Mises Stress | Equivalent stress value used to assess stress distribution in structures. |

| PET-G | Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol-modified. |

| Aligners | Clear thermoplastic orthodontic appliances used for tooth movement. |

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography. |

| AAP/EFP | American Academy of Periodontology/European Federation of Periodontology. |

Appendix A

The nonlinear mechanical properties of the PDL were previously derived from load displacement experiments on tooth–PDL–bone specimens [53]. The shear stress–strain relationship was fitted to an exponential function, and piecewise elastic moduli were calculated to generate stress–strain data for finite element input. The model predictions were validated against experimental results, showing strong agreement (r2 > 0.9) [40].

τ = A(eBγ − 1)

Commercial software (Sigma Plot v13, Jandel, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to determine A and B for each transverse section, and close agreement between the data points and the curve-fit equation was achieved (r2 > 0.9) for each transverse specimen. Shear stress and strain were calculated for 10 data points per Equation (A1). The slope between adjacent data points was computed to determine a piecewise linear shear modulus (Gi) from which the elastic modulus (Ei) was then calculated with Equation (A2).

Ei = 2 Gi (1 + ν) ν = 0.45, i = 1, 2, …, 9

A set of 10 data points (εi, σi) was calculated with the elastic modulus according to Equation (A3).

σi − σi−1 = Ei (εi − εi−1) i = 1, 2, …, 10

These data points were used as input to the FE software (Ansys 2024 R2, Canonsburg, PA, USA) to describe the nonlinear mechanical properties of the PDL.

References

- Dianiskova, S.; Rongo, R.; Buono, R.; Franchi, L.; Michelotti, A.; D’Antò, V. Treatment of mild Class II malocclusion in growing patients with clear aligners versus fixed multibracket therapy: A retrospective study. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2022, 25, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirlys, R.; Nedzinskaitė, R.; Rongo, R.; Severino, M.; Puisys, A.; D’Antò, V. Digital planning technique for surgical guides for prosthetic implants before orthodontic treatment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongo, R.; Dianišková, S.; Spiezia, A.; Bucci, R.; Michelotti, A.; D’Antò, V. Class II malocclusion in adult patients: What are the effects of the intermaxillary elastics with clear aligners? A retrospective single center one-group longitudinal study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staderini, E.; Meuli, S.; Gallenzi, P. Orthodontic treatment of class three malocclusion using clear aligners: A case report. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2019, 9, 360–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staderini, E.; Patini, R.; Meuli, S.; Camodeca, A.; Guglielmi, F.; Gallenzi, P. Indication of clear aligners in the early treatment of anterior crossbite: A case series. Dent. Press. J. Orthod. 2020, 25, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Ren, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Jian, F.; Long, H.; Lai, W. Effectiveness of clear aligners in achieving proclination and intrusion of incisors among Class II division 2 patients: A multivariate analysis. Prog. Orthod. 2023, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassem, A.A.B. Does clear aligner treatment result in different patient perceptions of treatment process and outcomes compared to conventional/traditional fixed appliance treatment: A literature review. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 16, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccomanno, S.; Saran, S.; Laganà, D.; Mastrapasqua, R.; Grippaudo, C. Motivation, perception, and behavior of the adult orthodontic patient: A survey analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 2754051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mir, C.; Brandelli, J.; Pacheco-Pereira, C. Patient satisfaction and quality of life status after 2 treatment modalities: Invisalign and conventional fixed appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Pereira, C.; Brandelli, J.; Flores-Mir, C. Patient satisfaction and quality of life changes after Invisalign treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokeen, B.; Viloria, E.; Duong, E.; Rizvi, M.; Murillo, G.; Mullen, J.; Shi, B.; Dinis, M.; Li, H.; Tran, N.C. The impact of fixed orthodontic appliances and clear aligners on the oral microbiome and the association with clinical parameters: A longitudinal comparative study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 161, e475–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yan, X.; Zhao, R.; Shan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jian, F.; Long, H.; Lai, W. Comparison of pain perception, anxiety, and impacts on oral health-related quality of life between patients receiving clear aligners and fixed appliances during the initial stage of orthodontic treatment. Eur. J. Orthod. 2021, 43, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, X.; Yan, X.; Tang, Z.; Lai, W.; Long, H. Orthodontic Practitioners’ Knowledge and Education Demand on Clear Aligner Therapy. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluccio, G. Is the use of clear aligners a real critical change in oral health prevention and treatment. La Clin. Ter. 2021, 172, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, B.-O. Orthodontic treatment for maxillary anterior pathologic tooth migration by periodontitis using clear aligner. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2011, 41, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, K.; Nazeer, M.R.; Ghafoor, R. Interdisciplinary management of gingiva l recession and pathologic teeth migration-Revisiting dental aesthetics. JPMA 2019, 69, 1384–1388. [Google Scholar]

- D’Antò, V.; Rongo, R.; Casaburo, S.D.; Martina, S.; Petrucci, P.; Keraj, K.; Valletta, R. Predictability of tooth rotations in patients treated with clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.F.; Ford, P.J.; Symons, A.L. Periodontal disease and the special needs patient. Periodontology 2000 2017, 74, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiwattanapong, K.; Samruajbenjakun, B. Tissue response resulting from different force magnitudes combined with corticotomy in rats. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, H.E.; El-Beialy, A.R.; El-Ghafour, M.A.; Abouelezz, A.M.; El Sharaby, F.A. Root resorption associated with maxillary buccal segment intrusion using variable force magnitudes: A randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, C.; Hotokezaka, H.; Yoshimatsu, M.; Yozgatian, J.H.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Yoshida, N. Force magnitude and duration effects on amount of tooth movement and root resorption in the rat molar. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodorou, C.I.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M.; Bronkhorst, E.M.; Wagener, F.A. Optimal force magnitude for bodily orthodontic tooth movement with fixed appliances: A systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 156, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, W.; Engelke, B.; Jung, K.; Dathe, H.; Fialka-Fricke, J.; Kubein-Meesenburg, D.; Sadat-Khonsari, R. Initial forces and moments delivered by removable thermoplastic appliances during rotation of an upper central incisor. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertan, E.; McCray, J.; Bankhead, B.; Kim, K.B. Force profile assessment of direct-printed aligners versus thermoformed aligners and the effects of non-engaged surface patterns. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Martines, E.; Mazzanti, V.; Arreghini, A.; Mollica, F.; Siciliani, G. Stress relaxation properties of four orthodontic aligner materials: A 24-hour in vitro study. Angle Orthod. 2016, 87, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, P.; Mazzanti, V.; Mollica, F.; Pellitteri, F.; Palone, M.; Lombardo, L. Stress relaxation properties of five orthodontic aligner materials: A 14-day in-vitro study. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-H.; Kwon, J.-S.; Jiang, H.B.; Cha, J.-Y.; Kim, K.-M. Effects of thermoforming on the physical and mechanical properties of thermoplastic materials for transparent orthodontic aligners. Korean J. Orthod. 2018, 48, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcaraz, I.; Moyano, J.; Pàmies, A.; Ruiz, G.; Artés, M.; Gil, J.; Puigdollers, A. Properties of superelastic nickel–titanium wires after clinical use. Materials 2023, 16, 5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanne, K.; Hiraga, J.; Kakiuchi, K.; Yamagata, Y.; Sakuda, M. Biomechanical effect of anteriorly directed extraoral forces on the craniofacial complex: A study using the finite element method. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1989, 95, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, N.J.; Wilson, A.N.; Jones, M.L.; Middleton, J. A stress analysis of the periodontal ligament under various orthodontic loadings. Eur. J. Orthod. 1991, 13, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geramy, A. Initial stress produced in the periodontal membrane by orthodontic loads in the presence of varying loss of alveolar bone: A three-dimensional finite element analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2002, 24, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.; Jones, M.; Wilson, A. The role of the periodontal ligament in bone modeling: The initial development of a time-dependent finite element model. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1996, 109, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gill, G.; Kaur, H.; Amhmed, M.; Jakhu, H. Role of osteopontin in bone remodeling and orthodontic tooth movement: A review. Prog. Orthod. 2018, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortona, A.; Rossini, G.; Parrini, S.; Deregibus, A.; Castroflorio, T. Clear aligner orthodontic therapy of rotated mandibular round-shaped teeth: A finite element study. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, W. Force changes associated with different intrusion strategies for deep-bite correction by clear aligners. Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Li, S. The optimal orthodontic displacement of clear aligner for mild, moderate and severe periodontal conditions: An in vitro study in a periodontally compromised individual using the finite element model. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S173–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S159–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-H.; Hong, K.; Lim, D.; Lee, J.-H.; Jung, Y.J.; Kim, B. Optimal position of attachment for removable thermoplastic aligner on the lower canine using finite element analysis. Materials 2020, 13, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toms, S.R.; Eberhardt, A.W. A nonlinear finite element analysis of the periodontal ligament under orthodontic tooth loading. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 123, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, D.; Li, N. Clear aligner orthodontic therapy of rotated mandibular teeth with different shapes: A three-dimensional finite element analysis. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2023, 27, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Yang, X.; He, B.; Yao, J. Finite element method analysis of the periodontal ligament in mandibular canine movement with transparent tooth correction treatment. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-M.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Lee, H.-F.; Lin, C.-T.; Yao, W.-C.; Chiu, W.-T.; Lee, S.-Y. Damping effects on the response of maxillary incisor subjected to a traumatic impact force: A nonlinear finite element analysis. J. Dent. 2006, 34, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Zhao, S.; Shi, H.; Lu, R.; Yan, B.; Ma, S.; Markert, B. Viscoelastic properties of human periodontal ligament: Effects of the loading frequency and location. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, N.; Liu, M.; Cheng, K.; Jiang, D.; Yi, Y.; Ma, S.; Yan, B.; Lu, Y. Construction of human periodontal ligament constitutive model based on collagen fiber content. Materials 2023, 16, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Huang, C.; Li, N.; Lu, Y.; Yi, Y.; Yan, B.; Jiang, D. Formulation of Hyperelastic Constitutive Model for Human Periodontal Ligament Based on Fiber Volume Fraction. Materials 2025, 18, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q. The force effects of two types of polyethylene terephthalate glyc-olmodified clear aligners immersed in artificial saliva. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Fu, Y.; Shi, H.; Yan, B.; Lu, R.; Ma, S.; Markert, B. Tensile testing of the mechanical behavior of the human periodontal ligament. Biomed. Eng. Online 2018, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geramy, A. Alveolar bone resorption and the center of resistance modification (3-D analysis by means of the finite element method). Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2000, 117, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkantidis, N.; Christou, P.; Topouzelis, N. The orthodontic–periodontic interrelationship in integrated treatment challenges: A systematic review. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2010, 37, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taffarel, I.A.; Gasparello, G.G.; Mota-Júnior, S.L.; Pithon, M.M.; Taffarel, I.P.; Meira, T.M.; Tanaka, O.M. Distalization of maxillary molars with Invisalign aligners in nonextraction patients with Class II malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, e176–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castroflorio, T.; Sedran, A.; Parrini, S.; Garino, F.; Reverdito, M.; Capuozzo, R.; Mutinelli, S.; Grybauskas, S.; Vaitiekūnas, M.; Deregibus, A. Predictability of orthodontic tooth movement with aligners: Effect of treatment design. Prog. Orthod. 2023, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toms, S.R.; Dakin, G.J.; Lemons, J.E.; Eberhardt, A.W. Quasi-linear viscoelastic behavior of the human periodontal ligament. J. Biomech. 2002, 35, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).