Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) encompasses various neurological disorders with symptoms varying by age, development, genetics, and other factors. Core symptoms include decreased pain sensitivity, difficulty sustaining eye contact, incorrect auditory responses, and social engagement issues. Diagnosing ASD poses challenges as signs can appear at early stages of life, leading to delayed diagnoses. Traditional diagnosis relies mainly on clinical observation, which is a subjective and time-consuming approach. However, AI-driven techniques, primarily those within machine learning and deep learning, are becoming increasingly prevalent for the efficient and objective detection and classification of ASD. In this work, we review and discuss the most relevant related literature between January 2016 and May 2024 by focusing on ASD detection or classification using diverse technologies, including magnetic resonance imaging, facial images, questionnaires, electroencephalogram, and eye tracking data. Our analysis encompasses works from major research repositories, including WoS, PubMed, Scopus, and IEEE. We discuss rehabilitation techniques, the structure of public and private datasets, and the challenges of automated ASD detection, classification, and therapy by highlighting emerging trends, gaps, and future research directions. Among the most interesting findings of this review are the relevance of questionnaires and genetics in the early detection of ASD, as well as the prevalence of datasets that are biased toward specific genders, ethnicities, or geographic locations, restricting their applicability. This document serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers, clinicians, and stakeholders, promoting a deeper understanding and advancement of AI applications in the evaluation and management of ASD.

1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a broad term that includes several neuropsychiatric disorders. Impaired social communication, interpersonal relationships, academic achievement, and confined and repetitive activities are all characteristics of this disorder. When compared to others, people with ASD frequently display variations in habits, interaction, and learning [1]. The term `spectrum’ in ASD refers to a wide range of characteristics, aptitudes, and capacities particular to each person. Individuals with ASD experience this condition differently from one another, which results in a range of assistance needs. Although the fundamental traits of ASD offer a range of difficulties, they may also lead to unique strengths and skills. Even though this is a lifelong condition, both adults and children with ASD may make significant progress and have fulfilling lives with the correct kind of assistance [2,3]. Although the specific causes of ASD are still unclear, biological variables such as mutations in genes, inflammatory conditions of the brain, and detrimental perinatal circumstances are likely to be involved. ASD symptoms can be confusing and time-consuming to diagnose since they resemble those of several other mental conditions. Although we lack a definitive treatment for ASD, early detection of its symptoms can lessen its impact over time [4]. Core symptoms of ASD include decreased pain sensitivity, trouble sustaining eye contact, incorrect auditory response, reluctance to snuggle, difficulties using gestures, inability to engage in social engagement, abnormal attachment to items, and a desire for isolation among children. In addition to behavioral examinations specific to ASD, standard clinical and medical records can provide vital information for assessing young children’s risk for ASD. Research has shown that extra symptoms and health concerns, such as digestive disorders, infections, and feeding difficulties, are common in kids with ASD [5].

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depressive disorders, and epileptic seizures are among the co-occurring problems that people with ASD frequently face. Moreover, individuals often exhibit difficulty controlling challenging behaviors, such as self-harm and sleep disruptions. ASD’s intellectual landscape is broad, ranging from those with severe cognitive deficits to those who perform at exceptionally high levels [6,7]. Although 168 million people worldwide might be affected by ASD, the actual number is probably larger due to underdiagnosis brought on by a lack of resources and awareness [8]. Unbelievably, one-third of people with ASD live in low- and middle-income nations, where it is sometimes difficult to get a diagnosis and receive proper treatment.

ASD has become more common, especially in the last several decades. In the United States, the prevalence of ASD increased from 1 in 150 children in 2000 to 1 in 44 children in 2018 [9]. This increase might be influenced by greater awareness, diagnosis improvements, and diagnostic criteria changes, although the exact causes remain unknown. Up to 2023, the countries with the largest children population affected with ASD were the United States, with 466,665; Japan, with 127,590; and the United Kingdom, with 95,801 children [10].

The treatment of ASD accounted for over USD 1.88 billion of the global market in 2021. According to projections, it will reach over USD 3.5 billion by 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.15% between 2022 and 2030. The increasing incidence of ASD is driving the growth of the market for treatments. Additionally, the World Health Organization’s revised study from March 2022 showed that one in 100 children globally has ASD, highlighting the critical need to address this expanding health issue. Anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, antidepressants, as well as other drugs that focus on specific disorder symptoms are commonly used in the treatment of ASD. Nevertheless, despite continuous attempts, there are not any reliable ASD therapy alternatives on the market. As such, pursuing the objective of research and development to improve treatment alternatives offers profitable prospects for market growth (see Figure 1 for more details).

Figure 1.

Global ASD treatment market size (in USD billion) [11].

Offering children with ASD symptoms the proper therapy and treatment requires early discovery and diagnosis. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that, over the previous fifteen years, four and a half years have been the average age at which early indications of ASD are diagnosed. However, parents and other caretakers frequently become aware of issues at around two years old. As such, it is critical to apply efficient diagnostic and rehabilitation methods. There are two primary methods for identifying and monitoring kids with ASD: manual and automatic methods [12]. For the identification and diagnosis of ASD, automated systems using computer vision and image-based techniques in conjunction with conventional machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are becoming increasingly common [13].

Additionally, manual techniques like observation- and interview-based methodologies are standard nowadays. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), for example, uses 15 questions to diagnose ASD and uses scores to classify severity [14]. Interview-based systems such as the Growth-related Dimensional analysis, Diagnostic Interview (3DI) [15], Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) [16], and Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Interview (ASDI) require in-depth interviews with parents or other caregivers to diagnose ASD [17]. Similarly, the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) uses 56 items divided into four categories to evaluate the severity of ASD [18]. However, this manual approach is not practicable for collecting data during daily activities since it primarily depends on expert opinion and behavioral observations. It takes a lot of time and money as well [19].

Researchers have created automated solutions to improve precision and effectiveness using the diagnosis process to overcome the shortcomings of conventional ASD diagnostic techniques [20,21]. For example, conventional ML methods and computer vision have demonstrated potential for producing quick and efficient screening tools [22,23,24]. Meanwhile, DL approaches have outperformed traditional ML methods by automatically extracting characteristics and decreasing mistakes in identifying and diagnosing medical conditions, including ASD [21]. The capacity to analyze photos and videos for detecting, categorizing, diagnosing, and tracking ASD has increased dramatically in recent DL developments, significantly improving manual techniques [25,26].

ML is a fast-growing Artificial Intelligence (AI) subfield that uses information to create highly accurate predictive models. ML encompasses diverse algorithms designed for classification, regression, and clustering [27]. These algorithms, such as Naïve Bayes, support vector machines (SVM), logistic regression (LR), k-nearest neighbors (kNN), linear and polynomial regression (LPR), k-means, neural networks (NNs), and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are adept at learning and interpreting intricate data features [27,28]. They are instrumental in predicting and classifying ASD across various age groups. Given the proper requirements, these techniques can predict survival rates, analyze behavior, study gaze patterns, and more, thereby facilitating early diagnosis of ASD [29].

Standardized behavioral evaluations, which can be drawn out and time-consuming, are commonly used to diagnose ASD. The goal of research on psychiatric neuroimaging is to find objective biomarkers that can help diagnose and treat brain-based diseases more effectively. By removing identifying characteristics from functional MRI (fMRI) data and passing them into classifiers, the literature has explored DL approaches to automate the diagnosis of ASD. Cutting-edge DL methods have greatly improved the classification of ASD by distinguishing ASD from typical developmental behaviors [30]. These methods improve the effectiveness of feature transformation and reduction, which reduces analysis time and improves classification parameters. The accuracy, specificity, error rate, sensitivity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Area Under the Curve (AUC), and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) are common performance indicators used in the evaluation of diagnostic tools for ASD and play a vital role [31,32]. In this area, CNNs, deep neural networks (DNNs), graph convolutional networks (GCNs), and hybrid models have shown encouraging outcomes [33].

AI-powered computer-aided systems use combined AI and relative technologies like ML and DL techniques. DL has grown increasingly used for extracting deep features [34]. New developments in ASD diagnosis use DL models, combining ML and neuroimaging techniques through DL to identify early biological indicators [35,36]. CNN models that have been simplified exhibit remarkable F1-scores, accuracy, and precision. Still, difficulties remain, including problems with data accuracy, comprehensibility, and ethical dilemmas [37]. With a combination of DL approaches, ASD detection algorithms are developing and combining data from several sources to increase accuracy. DL techniques have become common in the early phases of ASD identification and analyzing speech data, behavioral observations, and neuroimaging [38]. This combination improves diagnosis precision and speeds up the procedure, which might result in better results. Accurate diagnosis depends critically on structural MRI (MRI) and functional MRI (fMRI) [39].

It is essential to critically evaluate the aims and constraints of previous studies to ascertain the present level of academic comprehension concerning the methodologies of ASD using AI tools. Song et al. [40] conducted a systematic review and analyzed 13 research studies from 2009 to 2019 that used AI to diagnose ASD. They employed supervised ML techniques to distinguish between people with and without ASD. Their study investigates AI’s capacity to record behavioral traits that might act as diagnostic markers objectively. Kohli et al. [16] reviewed potential techniques, such as machine learning and deep learning, to enhance the early identification of ASD. The study carried out a scoping review of 35 studies published from 2011 to 2021, and this study focused on multiple modalities such as stereotypical behaviors, eye gaze, facial expression, etc. Moreover, this scoping review addresses the limitations and future works. Minissi et al. [41] focused on evaluating the earliest stages of ASD using ML approaches to analyze eye movement (EM) biomarkers regarding social cues. They looked at 11 research articles from 2015 to 2020 that used ML to study children’s social visual attention (SVA) and found disparities between friends with ASD and those typically developing (TD). Jeyarani and Senthilkumar [42] examined 30 selective new studies published between 2017 and 2020 that focused on eye tracking data based on ML and DL techniques. They also described the diagnostic tools, performance criteria, and datasets in the review. Furthermore, this study focused on insights into the detection, behavioral assessment, and differentiation between autistic children and TD. Moreover, Joudar et al. [43] systematically reviewed 18 research articles published from 2017 to 2022. They assessed AI approaches using different datasets and examined AI’s involvement in triage, priority setting, and genetic factors. The study explored ML models as prediction tools for diagnosing ASD by addressing research limitations and gaps. The study conducted by Parlett-Pelleriti et al. [44] reviewed 43 articles based on unsupervised ML and focused on the diagnosis and treatment of ASD based on genetic and behavioral data. More recently, Uddin et al. [45] presented a detailed review of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques for detection, classification, and rehabilitation of ASD. In their review, they reported 130 articles published from 2017 to June 2023, concentrating on the usage of the DL models to analyze image or videos representing ASD.

Various authors have presented their solutions using AI-based approaches. The goal was to extract potential findings and research gaps within this area so that future investigators could research and work on them. Moreover, even published in recent years, some systematic literature review (SLR) research considered only a few modalities and missed others that could provide deeper insights and information. Our primary motivation is to explore various modalities, including MRI images, genomics, facial images, eye gaze patterns, EEG signals, and questionnaires, by extensively reviewing most of the related work within this domain for early detection of ASD. However, the aim is to conduct a novel research covering all the essential aspects like reviewing the literature, extracting prospective limitations, identifying AI-based challenges, research gaps, reviewing potential datasets and deriving their limitations and overall contribution of AI for detecting and classifying ASD.

The reminder for this document is as follows. Section 2 describes the objectives and research questions in our work. Additionally, we describe the search and data extraction process, which includes the search, inclusion and exclusion criteria. Section 3 describes the most relevant contributions and various modalities of AI to ASD detection and classification. Section 4 describes the related work regarding ML and DL. In Section 5, we provide a list of popular datasets available for ASD detection and classification. Section 6 describes the limitations and research gaps we identified in the literature. Finally, Section 7 provides a conclusion and some ideas for future work.

2. Research Methods

This work compares various research methodologies and techniques presented by different authors. The study rigorously evaluates the research process and outcomes, focusing on their effectiveness, innovation, and performance. We meticulously defined the search strategy, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the quality assessment standards for the selected articles.

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, which provide a standardized framework for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses [46,47]. PRISMA offers multiple benefits, including facilitating comprehensive searches of research repositories, clarifying the description of research questions, and providing a transparent and rigorous approach to defining inclusion and exclusion criteria for relevant studies. Supplementary Materials File S1 presents the completed PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist [48] corresponding to the present review. In addition, this investigation was registered on the Open Science Framework and is publicly available at https://osf.io/ua6b4/, accessed on 10 March 2025.

The following sections provide detailed explanations of each component in this work.

2.1. Objectives and Research Questions

The primary objective of this study is to explore the significant roles of AI and its associated techniques, such as ML and DL, in detecting or classifying ASD. Additionally, the research reviews related works by various authors utilizing ML and DL, highlighting the difficulties and challenges encountered in ASD detection or classification. Another key goal is to identify shortcomings and gaps in current ASD intervention strategies. This proposed study offers valuable insights into different areas for improvement, future directions, and potential outcomes in the field of ASD treatment, as well as support.

This work aims to answer the following research questions:

- (i)

- What are the key contributions of AI and its subfields, such as ML and DL, in detecting or classifying ASD?

- (ii)

- Which datasets are available for ASD detection or classification, and what are their representative characteristics?

- (iii)

- What significant advancements and studies have been conducted in the domain of ML and DL for ASD detection or classification?

- (iv)

- What are the limitations and gaps in the current research on ASD detection or classification using AI and its subfields such as ML and DL, and how can these be addressed in future studies?

2.2. Search and Data Extraction

To retrieve the documents considered for this work, we used the following query:

- ("autism spectrum disorder" OR "autism" OR "asd") AND

- ("machine learning" OR "deep learning") AND

- ("classification" OR "detection" OR "identification")

Such a query allowed us to retrieve relevant literature on the research topic. We executed this query across reputable databases, including PubMed, WOS, IEEE, and Scopus. As described before, our review incorporates all English-language articles presented to peer-reviewed conferences or journals. However, we excluded some works from this analysis for various reasons, such as those presenting an unclear methodology, tools, strategy, or approach. Thus, from all the documents retrieved by our search, we only considered:

- (i)

- Documents written in English.

- (ii)

- Documents published between 1 January 2016 and 31 May 2024.

- (iii)

- Documents related to AI, ML- and DL-based detection or classification of ASD and aligned with our research questions and objectives.

Please note that, according to the inclusion criteria, we excluded documents written in languages other than English from our study. Additionally, we also excluded grey literature, abstracts, or preprints to ensure the inclusion of only peer-reviewed, methodologically sound, and fully reported studies. These sources often lack rigorous quality control, comprehensive data, or final results, which may compromise the reliability and reproducibility of our findings.

Search Results

To decide on the documents for our analysis, we followed a PRISMA-inspired four-step methodology, as described in Figure 2. Initially, we obtained 4719 documents by using the query as described before. We removed 2042 duplicate results during the screening phase since some documents appear in multiple sources. This elimination reduced the number of documents to 2677. Additionally, during the same phase, we removed 2611 documents since we considered them out of this work’s scope based on their title and abstract, which left 66 documents. In the eligibility phase, our criteria focused on studies involving the detection, classification, and identification of ASD using AI methodologies, mainly consisting of ML and DL techniques and full-text evaluation. A variety of diagnostic modalities, such as MRI/fMRI, eye gaze, facial images, questionnaires, genetics, and EEG, were included in these studies. Subsequently, from the 66 documents resulting from the screening phase, articles that failed to meet the requisite criteria were removed for the following reasons: five documents because they contained insufficient comprehensive information, seven more documents due to their irrelevance to ASD diagnosis, four more because of an absence of discernible results, and two more because they were retracted. By the end of the selection process, we kept only 48 documents for full review eligibility and met the inclusion criteria based on ML and DL approaches.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the study-selection process.

3. Contributions of Artificial Intelligence to ASD Detection

In addition, the identification of many brain abnormalities, including ASD, has been greatly facilitated by the quick development of neuroimaging methods. For example, MRI is a crucial noninvasive technique for assessing brain structure, white matter (WM) integrity, and functional activity. Structural MRI (sMRI) has been employed to delineate the morphological alterations in the brain associated with ASD, focusing on the shape and volume of various brain areas. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) evaluates anatomical connections and has revealed impaired microstructural white matter integrity in individuals with autism. Functional MRI (fMRI) depends on identifying dynamic physiological data from active cerebral areas. Assessing alterations in blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signals in different brain states (resting state or task-induced) can uncover functional architectural anomalies in the ASD population despite various MRI modalities demonstrating potential in differentiating people with ASD from healthy controls (HCs) [49]. For instance, Abraham et al. [50] used features derived from ROI-based resting-state FC metrics to distinguish ASD from HCs. They used an SVM algorithm, exposing an enhancement in predictive accuracy corresponding to an enhancement in participant numbers. Later, Saad and Islam [51] relied on SVM and a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) to categorize the data, and PCA was employed to reduce the noise characteristics based on graph theory with DTI-based connection characteristics and classify ASD from HCs. The best performance was determined using two PCA features and the SVM algorithm.

Furthermore, EEG captures the brain’s electrical activity by measuring the electrical impulses of various frequencies utilized by neurons for communication via electrodes affixed to the scalp. EEG-based diagnosis can offer better-tailored interventions by identifying diverse neurophysiological traits in autistic patients. EEG data analysis enables the detection of aberrant synchronous neural activity in children with ASD. The researcher investigated the amalgamation of EEG with AI methodologies to improve the identification and categorization of ASD [52]. For instance, Rogala et al. [53] utilized traditional statistical methods with classical ML techniques based on EEG data to classify distinct features or attributes linked to ASD. Researchers also combined statistical and ML approaches to enhance the classification of ASD.

Moreover, eye tracking (ET) is a noninvasive technique for recording a person’s gaze positions in real-time, which allows us to examine a user’s eye movements or the focus point of an individual. It is a process of assessing the point of gaze or the location of eyes and gathering the eye features from an individual. The recorded data containing fixation amounts, first fixation, and fixation duration can be examined using visual analytic methods to review and obtain the eye features. It utilizes a visual analytic procedure to enhance the visualization of general visual problem-solving [54]. For example, Meng et al. [55] used eye movement data to apply ML techniques for early detection of ASD gathered from individuals as they view different types of faces (real and artificial). Notably, it examined how the gaze patterns of individuals can be assessed when they inspect both real human faces and artificial faces to classify key markers of ASD.

Researchers have relied on AI techniques for the early identification of ASD based on facial photos. Facial images may be the most reliable diagnosis technique because every child with ASD differs from a normal child based on facial features. Researchers from the University of Missouri discovered that children with autism exhibit specific facial characteristics, like wide-set eyes and a broad upper face. Compared to youngsters without ASD, their faces are frequently characterized by a shorter central area, including the nose and cheeks. Because of the social impact on emerging nations, research on the facial feature-based diagnosis of ASD is expanding quickly [56]. For example, in this study, Awaji et al. [57] explored hybrid techniques for early detection of ASD based on facial images using CNN-based feature extraction. This method also integrated many CNN models to improve the detection accuracy and utilized DL to capture intricate facial patterns related to ASD.

AI algorithms analyze genetic data to find variations linked to the severity and susceptibility to ASD [58]. By identifying specific gene mutations and pathways related to ASD, whole-genome sequencing and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) shed light on the ASD genetic makeup. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) has excellent potential for deciphering intricate representations and patterns in various data sources. To build trust and enable more informed and actionable insights in biomedical applications, XAI makes the inner workings of these models more transparent, enabling researchers and clinicians to understand better how decisions are made [59]. AI-driven methods improve our comprehension of the intricate genetic foundation of ASD and guide tailored treatments that focus on the underlying molecular process [60]. For more details, each modality is described individually below.

4. Related Work in the ML and DL Domain

4.1. Questionnaire-Based Diagnosis of ASD

Early screening is crucial for timely intervention in children’s development. Regular screening by using tools like the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ), the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), and the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) helps gather information about a child’s social skills and behavior. This information aids healthcare professionals in diagnosing ASD, a process they can only carry out. Diagnosis involves the use of standardized diagnostic tools such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5). These methods rely primarily on interviews, which are easily adaptable to participants of all ages [61].

Early identification helps to ensure prompt intervention, which has a significant impact on the management of ASD. They function similarly to checklists physicians use to spot trends that may indicate ASD and order early screens and therapies. The diagnosis of ASD is undergoing a revolution due to recent developments in AI. For example, ML and DL algorithms process through enormous volumes of data from many sources. This data consists of medical records, questionnaires, and behavioral assessments. By examining these many sources, AI can find trends and indicators related to ASD [62,63]. The following lines describe, chronologically, relevant works where AI has interacted with data gathered from questionnaires to improve ASD diagnosis.

In 2019, Erkan and Thanh [64] proposed a classification system for ASD data to facilitate early ASD diagnosis using practical algorithms. It used three ASD datasets to consider kids, teens, and adults (AQ-10-Child, AQ-10-Adolescence, and AQ-10-Adult). Their research used Random Forests (RF), SVM, and k-nearest neighbors (kNN) for classification in datasets with 20 variables that include screening questions and personal information. Their study suggests that RF and SVM are valuable techniques for classifying ASD. Also in 2019, Akter et al. [65] used datasets that included people with ASD of all ages, from toddlers to adults. It used a variety of approaches, such as sine function, logarithmic, and Z-score normalization, to modify the characteristics. They used the adjusted datasets to evaluate a variety of ML-based classifiers. Feature selection techniques were then used to Z-score normalized datasets to uncover significant ASD risk variables across age groups. The study showed how well optimal ML techniques can predict ASD, even in the face of obstacles like missing values and data noise. The UCI ML archives and Kaggle datasets included records for 1054 toddlers, 248 children, 98 adolescents, and 609 adults, with varying gender proportions for each age group.

A year later, Raj and Masood [66] used three publicly accessible non-clinical ASD datasets to predict and analyze ASD across various age groups: one with 21 characteristics for children (292 occurrences), one for adults (704 instances), and one for adolescents (104 instances). Their technique included a train-test split of 80:20 and tested NB, SVM, LR, kNN, neural networks (NN), and CNN models. CNN models performed better across all datasets. Later, the study conducted by Vakadkar et al. [67] focused on increasing the accuracy and swiftness of ASD diagnosis by integrating ML approaches with conventional methodologies. The dataset had 1054 instances at first, with 18 features. However, unimportant and categorical attributes had to be removed during the preprocessing. The dataset was then divided into 80% for training (843 samples) and 20% for testing (211 samples).

Another important work is that of Hossain et al. [22], who used various classification algorithms on datasets with different age groups (including toddlers, children, adolescents, and adults) to explore how to automate the diagnosis of ASD. Their study carefully cleans data and removes unnecessary features to preprocess ASD datasets. It then uses a wide range of 27 classification methods, evaluating each one using 10-fold cross-validation and evaluating the results according to accuracy and F1-score. The focus is on feature engineering, which identifies the most important features for the best classifier performance by rating them using five benchmark methodologies. The results highlight the multilayer perceptron (MLP) as the best classifier and the `relief F’ approach as the most successful feature selection technique for ASD identification among all age groups.

Bala et al. [68] developed an ML model that enabled more accurate identification of ASD in children, adolescents, adults, and toddlers. Their approach selected features using various methods and evaluated many classifiers using metrics, including AUROC, kappa statistics, F1-measure, and overall prediction accuracy. SVM consistently performed better in every age group than other classifiers. Significant ASD-related characteristics were found by analyzing several feature subsets employing the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) approach. The data gathering process entailed using the autism screening app ASDTests, which assessed the risk of ASD in various age groups using the Q-CHAT-10 and AQ-10 questionnaires. Each age group was represented by a dataset with 18 to 23 characteristics. That same year, Kumar and Das [69] looked at the automated generation of an autism diagnosis tool using ML using a dataset of 701 samples that include individual characteristics and AQ-10-Adult data. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) was used for feature selection in the training and testing of ML classifiers, including ANN, SVM, and RF, on a preprocessed dataset. The ASD screening data collection for adults includes 701 samples from 67 nations, with 512 negative and 189 positive cases. The gender distribution of the samples is also balanced. Regarding age, gender, jaundice, and ASD, including app usage, missing data are added, and classifiers like SVM, RF, and decision tree (DT), including LR with RFE, are used. A total of 12 classification models were created.

More recently, Farooq et al. [70] presented a federated learning (FL) method that uses locally trained SVM classifiers and LR classifiers to diagnose ASD in children and adults. Four datasets totaling more than 600 records each were considered to extract the features. The suggested strategy consists of five essential parts: gathering datasets, preprocessing data, locally training ML models, and testing to identify the best diagnostic model for ASD. Getting publicly accessible datasets, preprocessing and normalizing the data, and then individually implementing SVM and LR classifiers onto the dataset were the steps in the procedure. These classifiers then send their results across a centralized server, whereby a meta-classifier is developed to determine the best approach. Moreover, Khudhur and Khudhur [71] employed four non-clinical ASD screening datasets from Kaggle and the UCI ML library. These datasets comprise the following age groups: adults (704 cases, 21 features), adolescents (104 cases, 21 features), toddlers (1054 instances, 19 characteristics), and children (292 cases, 21 features). Several supervised ML models are used in the study, including RF, DT, SVM, kNN, NB, and LR. The study found that the best classifiers were DT, LR, and RF.

Finally, we can mention the works by Mukherjee et al. [72] and Rasul et al. [73]. Mukherjee et al. [72] relied on a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model to analyze parent-child conversations to identify indications of ASD in children. The data, which focused on improving speech, conduct, and communication, were gathered from various social media sites and groups that support kids with special needs. The gathered conversations underwent preprocessing. Then, the LSTM model was trained to identify sentiment patterns within the parent chats. After training and testing, the model could accurately predict sentiment on fresh input data, either 0 or 1. Conversely, Rasul et al. [73] used a dataset for adults with ASD and a children’s dataset based on the AQ10 questionnaire with 292 samples of children aged four to eleven. The study determined the effectiveness of eight state-of-the-art classification methods in identifying ASD. The study evaluates five clustering algorithms in the absence of labeled data. It examines how well they perform using measures such as Silhouette Coefficient (SC), Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI). Based on ARI and NMI metrics, spectral clustering is the best performer, while k-means shows the greatest SC. ML algorithms were trained and evaluated using five-fold cross-validation to ensure robust results.

We provide a summary of the studies related to the questionnaire data in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of works using AI techniques for detecting ASD through questionnaire data.

4.2. Facial Image-Based Diagnosis of ASD

The diagnosis of ASD has also been explored by examining facial characteristics [74]. Many facial distances are altered in ASD individuals, according to research: the distances between the glabella and nasion and the inner canthi, as well as the distances between nasion and landmarks on the nose and philtrum, are reduced, while the distances between the mouth and the nasal region, as well as the distances between facial landmarks and the eyes and the opposing side that contains the mouth, are increased. Boys with ASD usually exhibit significant facial asymmetry, particularly around the supra- and periorbital areas [75,76]. Additionally, studies reveal that compared to children without ASD, who more often display expressions indicating engagement and interest, kids who suffer from high-functioning autism (HFA) produce neutral emotions with greater frequency and show less richness and flexibility in their facial expressions.

Regarding real-time mental and emotional state assessments and ASD diagnosis, facial recognition technology is beneficial. This technique extracts characteristics that differentiate between regular and aberrant expressions by analyzing human traits and is applied to identify behavioral patterns from big datasets. The study of facial expressions in individuals with ASD has recently received more attention. Facial expressions have also been widely studied in individuals with neurological illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and frontotemporal dementia. Various techniques teach models to detect characteristics like lips, eyes, and eyebrows to help children with ASD comprehend and use facial emotions. Combined with iconized images, these models help in differential diagnosis [74,77]. The following is a list of the most relevant works related to AI techniques and the use of facial image data to detect ASD.

In 2016, Liu et al. [78] identified children with ASD relying on ML techniques to analyze data on eye movements using a face recognition test. They used a dataset including three cohorts: 29 Chinese children between four and eleven years old diagnosed with ASD, 29 Chinese children matched by age who were typically developed (TD), and 29 additional TD children matched by IQ. Its main objective was to assess the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of ASD categorization using patterns from face scans.

Later, in 2021, Lu and Perkowski [79] used the VGG16 DL model with transfer learning based on facial images for identifying ASD in children. This study employed two datasets: the Kaggle Autism Facial Dataset, which included 2936 photos from diverse racial origins, and the East Asia ASD Children Facial Image Dataset, which included 1122 photographs of East Asian children. The two datasets are split equally between kids with ASD and TD.

A year later, the study by Mujeeb Rahman and Subashini [80] determined whether facial traits taken from photos of autistic children may be used as a biomarker to distinguish autistic children from usually developing kids. The work uses a DNN model for accurate ASD classification and five pre-trained CNN models (MobileNet, Xception, EfficientNetB0, EfficientNetB1, and EfficientNetB2) with feature extraction. The 2936 colored 2D face photos in the dataset, which is publicly accessible and split into training, validation, as well as test sets with each grouping between autistic and non-autistic subgroups, are of children between the ages of two and 14, with the majority falling between the ages of two and eight. The CNN-based feature extraction tool captures complex face features important for categorization, demonstrating the model’s ability to extract sophisticated features beyond human visual evaluation using digital filters.

The year 2023 was critical for this type of application. Gaddala et al. [81] improved the diagnosis of ASD by integrating DL with conventional techniques for detecting ASD based on the dataset of facial images using deep CNNs such as VGG16 and VGG19. The models were trained to achieve optimal accuracy in ASD identification using a batch size aggregating 12 over ten epochs. Additionally, the study conducted by Alkahtani et al. [82] used a dataset of facial images from Kaggle. It focused on ML and DL techniques to diagnose ASD using facial landmark analysis, such as LR, linear SVM, RF, DT, gradient boosting, MLP classifiers, and KNNs with deep CNNs, including MobileNetV2 and hybrid VGG19 based on transfer learning techniques to improve the performance of the models using Kaggle dataset with 2940 photos of children with and without autism. Finally, Li et al. [83] employed DL techniques and focused on improving the performance of ASD classification using MobileNetV2 and MobileNetV3 large models through a two-phase transfer learning using the dataset of facial images. This study showed improvements, supporting the two-phase transfer learning method regarding accuracy and Area Under the Curve (AUC).

More recently, Reddy [84] addressed DL models; three pre-trained CNN models, VGG16, VGG19, and EfficientNetB0, were employed for feature extraction and classification of ASD using a dataset of facial images from Kaggle. The results revealed that DL models, especially EfficientNetB0, perform well in the classification of ASD.

At this point, we would like to provide deeper comparative insights regarding the performance of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and support vector machines (SVMs) in facial image analysis. Before CNNs became dominant, SVMs were considered state-of-the-art for many classification tasks. However, in recent years, CNNs have established themselves as the leading approach for object recognition in computer vision. One reason for their success is that convolutional layers can learn hierarchical and spatially-aware representations of input data, while fully connected layers subsequently map these representations to output classes. The superiority of CNNs is often attributed to several factors, including translation invariance, hierarchical feature learning, reduction in overfitting through techniques such as dropout and data augmentation, and efficiency in processing image data. By contrast, SVMs do not learn feature representations from data. Instead, they rely on a pre-specified kernel function to transform the data into a higher-dimensional space where it may become linearly separable. If the chosen kernel is appropriate, the SVM can perform well; if not, its performance degrades. This process can be seen as a form of “educated guessing”. In contrast, CNNs can be interpreted as learning both the feature transformation (analogous to a data-driven kernel) and the classifier simultaneously. This capacity to adaptively learn representations makes CNNs particularly advantageous in complex or exploratory domains [85,86].

Finally, regarding the architectures of the CNNs, VGG-16 is a relatively straightforward CNN architecture that does not include residual connections. In contrast, ResNet architectures incorporate residual blocks, allowing for the effective training of much deeper networks. As a result, ResNets generally outperform VGG models both in accuracy and computational efficiency. For example, ResNet-50 requires approximately 3.8 billion floating point operations (FLOPs), compared to 15.3 billion FLOPs for VGG-16 [87]. In terms of classification accuracy on the ImageNet benchmark, ResNet-50 achieves 85.7% of accuracy [88], compared to 79.01% for VGG-16 [89].

Furthermore, we present the summary of all studies on the facial image data in Table 2.

Table 2.

A summary of works using AI techniques for detecting ASD through facial image data.

4.3. MRI-Based Diagnosis of ASD

Strong magnets and radio waves are used in MRI to produce precise images of the body. MRI works similarly to a powerful camera that can see through muscle and skin, providing doctors with incredibly detailed images of organs, tissues, and the brain [90]. Since MRIs do not use radiation, they are safer than CT scans and X-rays. Because of this, they are ideal for evaluating soft tissues, such as the brain and muscles, which aid in diagnosing everything from malignancies to brain damage [91,92].

AI-based systems can decipher the complex information concealed in MRI images, particularly those built on ML, DL, and computer vision. These scans capture the structure and functionality of the brain, and AI decodes the intricate patterns inside them like a codebreaker. AI may detect minute variations in brain areas and their connections, frequently connected to ASD, by training on enormous volumes of MRI data. AI can recognize these subtleties that human specialists could overlook. This makes it possible to diagnose ASD more accurately and comprehend its brain roots on a deeper level. Additionally, MRI is a noninvasive, accurate method of making an early diagnosis of ASD in collaboration with medical specialists, which improves treatment strategies and provides insightful information about this complex disease [93,94].

For instance, Heinsfeld et al. [95] used a resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) dataset gathered by the Autism Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I), which included 530 typical controls (TC) and 505 people with ASD. The information collected from seventeen distinct imaging locations was utilized to train a classification model. The researchers used denoising autoencoders to improve model accuracy on new data, which recreated inputs from faulty copies. For the unsupervised pre-training phase, two stacked autoencoders were used to minimize the dimensionality of the data and maximize reconstruction loss. The autoencoder weights were merged into the multilayer perceptron (MLP), the final model, which was then fine-tuned to reduce prediction errors. The output layer of the MLP yielded the likelihood that an input image would be categorized as either TC or ASD. In addition, the work conducted by Li et al. [96] used fMRI scans to identify biomarkers for ASD using a dual-phase technique. Initially, spatial-temporal data from 4D fMRI, compressed to dimensions, is trained into a DNN classifier (2CC3D). The classifier combines dropout and L2 regularization to avoid overfitting with convolutional and fully connected layers. The technique uses task-based fMRI images processed by motion correction, slice timing correction, brain extraction, spatial smoothing, and high-pass filtering on participants with ASD and control subjects doing a pointing task. Sliding window analysis over the fMRI time dimension produces 144 3D volume pairings per participant during region segmentation, which is carried out using the AAL atlas. The method’s effectiveness in distinguishing ASD-related brain characteristics amongst ASD and experimental results demonstrate healthy controls.

Just a year later, Mostafa et al. [97] used the ABIDE dataset, which comprises structural MRI, rs-fMRI, and phenotypic data from 1112 participants (539 ASD and 573 TC), to diagnose ASD and 264 raw brain features derived from the eigenvalues of the Laplacian matrix of the brain network plus three network centrality features. These 264 features were reduced to 64 using a feature selection technique. After that, these characteristics are employed to train several ML models, such as NN, SVM, LDA, LR, and kNN, to diagnose ASD and the classification performance for ASD and TC participants. NN is implemented in PyCharm using Python, whereas LDA, LR, SVM, and kNN are executed in MATLAB. The same year, Eslami and Saeed [98] presented the Auto-ASD-Network model, which uses fMRI data to differentiate between individuals with ASD and healthy individuals. To increase classification accuracy and avoid overfitting, this model uses a multilayer perceptron (MLP) with two hidden layers and adds SMOTE for data augmentation. After being retrieved from MLP, the SVM classifier evaluates the features, and Auto-Tune Models (ATM) optimizes them. By interpolating between randomly chosen nearest neighbors, SMOTE is used to construct synthetic samples, increasing the training set’s size. The C-PAC pipeline preprocesses the ABIDE initiative’s fMRI data. The preprocessing steps include motion correction, slice timing correction, drift correction, nuisance signal removal, and voxel normalization. ABIDE’s spatially limited spectral clustering techniques partition the brain into 200 areas.

Sharif and Khan [99] presented an ML system that uses brain volume and corpus callosum data to identify ASD. This method simplifies model training through selective feature extraction while achieving excellent recognition accuracy for ASD. The study also investigates the use of DL for neuroimaging data analysis, using the ABIDE-I dataset to build a VGG16 model. This dataset includes 573 healthy controls and 539 autistic persons from 17 countries. The effectiveness of ML in analyzing structural MRI data for ASD identification was demonstrated by the evaluation of several classifiers, comprising LDA, SVM (with an RBF kernel), RF, MLP, and kNN (with ). Additionally, in 2022, in the study by Othmani et al. [100], MRI data is used to classify ASD using a comprehensible DNN method. When the techniques were evaluated using the ABIDE dataset, it outperformed VGG16 and ResNet-50 and produced encouraging results. Preprocessing the data, isolating and finally integrating local ROIs, enhancing the data to prevent overfitting, and feeding the enhanced dataset through the LeNet-5 network. It utilized data processed by the Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes (C-PAC). The results justify the implementation of LeNet-5 throughout an ASD diagnostic assistance system by showing that adding additional MRI images to the annotated training set considerably improves performance.

Using the ABIDE fMRI dataset, Zhang et al. [101] provided a DL strategy combined with the F-score feature selection method for ASD diagnosis. Their method finds functional connectivity characteristics in the ABIDE and intra-site datasets with great accuracy. ASD’s path duration and cluster coefficient significantly decreased, as shown by feature analysis, suggesting a switch between small world and random network architecture. The model is tested using k-fold cross-validation, which splits the source data across k-equal subsections between training and testing. An autoencoder is used to remove lower-dimensional features from the model. Classification accuracy (ACC), sensitivity (SEN), and specificity (SPE) are performance measures that quantify the percentage of adequately categorized subjects, correctly recognized individuals with ASD subjects, and correctly identified healthy subjects, respectively. Similarly, Park and Cho [102] used the ABIDE I dataset and applied a residual attention network integrated with a graph convolutional network to extract features from 4D brain scans. By using 10-fold cross-validation and the ABIDE I dataset, which comprises 800 individuals (389 with ASD and 411 controls), the model can attain a better accuracy rate. The training efficiency is increased by employing the Adam optimizer. The Adam optimizer was used to enhance the training accuracy or efficiency.

More recently, Bahathiq et al. [103] employed ABIDE datasets containing sMRI and rs-fMRI scans. Seven ML models were tested for their ability to detect early signs of ASD in children between the ages of five and ten. Combining Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) with support vector machines (SVM) yielded the most significant results. The assessment was conducted using 10-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness, and the models were trained using an 80/20 training–validation split. Additionally, Li et al. [104] employed a unique framework, LD-MILCT, for analyzing spatial and morphological data across different brain areas. It utilized a two-stage multi-instance learning technique. The multi-instance learning head (MIL head) of a Vision Transformer is integrated into the framework to optimize the use of essential characteristics for categorization. The study used the ABIDE dataset for ASD, which included 342 typically developing controls and 213 ASD patients, and the ADNI dataset for Alzheimer’s, which included 399 controls and 308 AD patients. In addition, also in 2024, Wang et al. [105] employed fMRI data from 264 participants, which consisted of 134 with ASD and 130 TD children. The study utilized cutting-edge techniques for detecting ASD using graph attention networks (GATs). The model considered every brain region of interest (ROI) as a node and used wavelet decomposition to extract features from the BOLD signal. The adjacency matrix is an optimized functional connectivity (FC) matrix. Self-attention methods capture long-range relationships between features, and node-selection pooling layers ascertain the importance of each ROI for prediction. Finally, Wang et al. [106] presented a multisite fMRI investigation using the ABIDE dataset. The study used a class-consistency and site-independence multiview hyperedge-aware hypergraph embedding learning (CcSi-MHAHGEL) framework to integrate functional connectivity networks (FCNs) from different brain atlases. A multiview hyperedge-aware hypergraph convolutional network (HGCN) trained adaptive hyperedge weights, developing a multi-atlas-based FCN embedding. The framework includes a site-independence module to minimize site-related disparities resulting from disparate scanning procedures and a class-consistency element to preserve intra-class compression with inter-class separation. Afterward, fully connected layers and a softmax classifier are used to facilitate diagnosis and multi-atlas-based FCN embeddings.

Table 3 summarizes the studies related to the MRI image data.

Table 3.

A summary of works using AI techniques for detecting ASD through MRI image data.

4.4. Eye Tracking-Based Diagnosis of ASD

The use of eye-tracking technology has provided evidence in favor of theories about the gaze habits of autistic youngsters. An effective way to evaluate ASD is by eye movement analysis, which can provide important information about a person’s cognitive abilities, social communication skills, and visual attention. Eye-tracking technologies allow for the recording several types of gaze patterns, such as saccadic eye movements, blinking, and fixation [107]. By highlighting minute differences in gaze-related behaviors, it becomes possible to pinpoint characteristics that differentiate people with ASD from the rest. Technological obstacles, such as various equipment types and intricate analytical methods, hinder the collection and processing of eye tracking data. Cutting-edge AI techniques such as ML and DL are being applied to improve eye-tracking equipment for examining gaze patterns and attentional mechanisms in people diagnosed with and not diagnosed with ASD [62,107]. Numerous research studies use AI algorithms to examine gaze patterns and diagnose autism. Through the analysis and classification of these gaze patterns, the integration of eye-tracking technology with AI algorithms has the potential for the early identification of ASD [62,108,109]. Some relevant works that have explored eye tracking to diagnose ASD are described below.

Fabiano et al. [110] categorized varying degrees of ASD risk using eye gaze data and demographic characteristics like age and gender. They developed feature descriptors incorporating these variables, and examining eye-gazing patterns verified their efficacy. Their work utilized the National Database for Autism Research (NDAR) “Eye Tracking Subject-Experiment” (ETS-E) dataset, which included 229 participants with varying degrees of ASD risk. PART, a deep NN, RF, and C4.5 DTs were among the classifiers put to the test. In addition to age and gender data, the dataset included information on eye gazing. By using age, gender, average fixation time, and raw eye gaze points, they created homogeneous feature vectors that enable precise ASD categorization determined by gaze patterns for in-depth analysis.

A year later, using ML and visualization approaches, Cilia et al. [111] investigated the application of eye tracking for ASD screening. Fifty-nine school-age participants in the study watched age-appropriate pictures and videos while having their eye movements monitored. Eye-tracking scan paths were converted into visual pictures or representations, which were analyzed using a CNN. This approach aimed to ease the diagnostic task and achieve high classification accuracy. High classification accuracy was achieved by converting these eye-tracking scan paths into visual pictures and employing a CNN for analysis. This suggests that visual representations can instead capture gaze motion details well. The study also looked at relationships between eye movement patterns and the degree of autism. Children with diagnoses of ASD, as well as generally developing kids, participated in the study; medical professionals confirmed the diagnosis. They used a threshold of 200 points to ensure optimal visual clarity in the scan path representations.

In 2022, Ahmed et al. [112] presented three AI approaches, ML, DL, and hybrid, for the early detection of autism. The first technique combined features taken from grey-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) and local binary pattern (LBP) methods using neural networks (FFNNs and ANNs). The second technique extracts deep features from CNN models that have already been trained, such as GoogleNet and ResNet-18. The third strategy, known as GoogleNet + SVM and ResNet-18 + SVM, is a hybrid approach that combines ML and DL methods such as (SVM, GoogleNet, and ResNet-18). The study also used image preprocessing and feature extraction using eye-tracking routes. The main contributions of their study are the unique hybrid strategy and the thorough examination of machine learning and deep learning techniques for eye-tracking ASD detection. Using visible eye-tracking scan path (ETSP) pictures, Kanhirakadavath and Chandran [113] analyzed ML approaches to determine the optimal model for autism prediction. They used a publicly accessible dataset of 547 ETSPs from 328 usually developing and 219 autistic children to test three conventional models, including a DNN classifier. To avoid overfitting, they used picture augmentation. The study aimed to replace subjective manual screenings with an objective and trustworthy way of diagnosing autism utilizing 2D ETSP pictures. While boosted DT (BDT), deep SVM, decision jungle (DJ), and DNN functioned as classifiers, principal component analysis (PCA) and CNN were employed for feature extraction. They assessed performance using AUC, specificity, sensitivity, PPV, and NPV.

Ahmed et al. [114] utilized cutting-edge technology based on eye tracking and deep-learning algorithms such as LSTM, CNN-LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and GRU networks. They trained these models using an eye tracking dataset specifically curated for ASD research. In performance evaluations, LSTM outperformed the other models in terms of accuracy. Moreover, in 2023, Thanarajan et al. [115] aimed to detect ASD using eye tracking based on deep learning techniques. The researcher integrated eye tracking data with the Chaotic Butterfly Optimization (CBO) method to enhance the diagnosis accuracy using the ETASD-CBODL framework. It analyzes the patterns using the visualization of eye-tracking scanpaths image dataset in ASD. The ETASD-CBODL approach uses Inception v3 for feature extraction and U-Net for segmentation to find regions of interest for feature extraction.

More recently, Alsaidi et al. [109] presented T-CNN-ASD, which analyzes ASD based on eye tracking data to categorize subjects into typically developing (TD) and ASD groups. The researchers utilized quantitative eye movement analysis to study attentional processes. It is a potential technique for establishing biomarkers in clinical experiments for ASD because of its high accuracy, cost, and ease of use. This framework compared the abnormal visual attention patterns displayed in children with ASD and those in TD children. The T-CNN-ASD model has two hidden layers comprising 300 and 150 neurons, respectively, and it was subjected to a 20% dropout rate during a 10-fold cross-validation process.

A summary of the studies related to the eye tracking data is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

A summary of works using AI techniques for detecting ASD through eye tracking data.

4.5. EEG-Based Diagnosis of ASD

EEG is a noninvasive method for evaluating electrical activity in the brain, making it crucial for clarifying the neurophysiological underpinnings of ASD. An EEG allows us to investigate the brain and detect minute electrical vibrations. This method of measuring brain activity and displaying it as wave patterns is painless. Epilepsy and sleep disturbances are among the illnesses that doctors identify with EEGs. Moreover, ASD can benefit from this technology if AI technologies are introduced in the diagnosis workflow. EEG recordings include intricate patterns that may be analyzed by AI techniques such as ML and DL, which allow the identification of ASD-specific patterns [52,116]. They search for indicators such as wave frequency, the electrical interactions between various brain areas, and the brain’s response to stimuli. AI can increase the precision of ASD diagnosis, particularly in the critical early stages, by identifying these minimal variations. Even better, AI can grow and learn over time. Large-scale EEG data analysis improves its ability to recognize ASD patterns. Because of this, AI techniques, such as ML and DL, can evaluate EEG data to identify abnormal brainwave patterns and connectivity and are valuable tools for medical professionals and researchers, providing a noninvasive and ever more trustworthy means of diagnosing and comprehending ASD [117,118,119].

For instance, Radhakrishnan et al. [120] investigated many deep convolutional architectures for ASD diagnosis, emphasizing good classification accuracy and automated feature extraction. Their study assesses models including AlexNet, DenseNet, SqueezeNet, ShuffleNet, VGGNet, InceptionNet, and ResNet based on precision, recall, and accuracy. Using k-fold cross-validation, ResNet50 outperformed the other models based on specificity and F1-Score. Therefore, the study suggests that ResNet50 be used to diagnose ASD from EEG waves. EEG data were obtained from 10 normally growing and autistic children collected using the internationally recognized 10-20 electrode system. At the same time, they were respecting ethical standards and getting parental agreement. The Helsinki Ethical Principles and ICMR Ethical Guidelines were adhered to by the procedure.

Rogala et al. [53] investigated the classification of ASD in children utilizing statistical methods and ML approaches to EEG data. The authors performed retrospective research using statistical methods and machine-learning approaches, employing clinical EEG recordings from two patient groups aged from 2.08 to 5.92 years. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test with FDR correction and the Friedman test were two statistical procedures. A logistic regression model with L2 regularization was utilized for machine learning approaches using cross-validation optimization to assess the model’s performance. In the same year, Alhassan et al. [121] presented sensor-based techniques for early detection of ASD using EEG signals. The study emphasized energy-efficient signal modification for feature extraction and classification using machine learning techniques. The complexity of brain activity was measured using multiscale entropy (MSE), which was calculated using digital Haar wavelet decomposition. The three ML classifiers examined were SVM, logistic regression, and decision trees.

More recently, Menaka et al. [122] evaluated the effectiveness of many deep learning models, such as AlexNet, VGG16, and ResNet50, in diagnosing ASD using EEG data utilizing five cepstral coefficient characteristics. One of the main contributions is using cepstral coefficients to create spectrograms during the processing stage. According to experimental data, the maximum accuracy is obtained when AlexNet is combined alongside Linear Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (LFCC). In addition, Al-Qazzaz et al. [123] utilized several pre-trained models, such as AlexNet, SqueezeNet, and MobileNetV2, to classify ASD based on EEG data. The EEG signals are segmented into five-second intervals, and power spectral density (PSD) is used to transform the signals into greyscale spectrograms. The researcher used hybrid models that combined DL models with traditional machine learning models such as SVM, kNN, and DT. According to the results, SqueezeNet increased accuracy, and performance is further improved when combined with the SVM classifier. Additionally, in 2024, Ullah and Yu [124] presented a weighted ensemble model based on DL for the classification of ASD. They used STFT to extract features from EEG recordings and convert them into 2D time-frequency spectrograms. The dataset included EEG data from 17 participants, 12 with ASD and 5 TD participants. EEG data was recorded with Ag/AgCl electrodes. An ensemble model is formed by combining three CNN models, and a grid search is used to build the final weighted ensemble.

We provide a summary of these studies in Table 5.

Table 5.

A summary of works using AI techniques for detecting ASD through EEG data.

4.6. Genetics-Based Diagnosis of ASD

Genetics has made a significant new understanding of the biology of ASD possible [125,126]. More than a thousand genes are thought to be involved in increasing the risk of ASD when they experience functional perturbations, including de novo mutations, disruptions to expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), and inheritance of harmful uncommon variants. Despite these approximations, recent studies have shown about 100 genes that have a high correlation with the incidence of ASD. Extensive genetic research is being conducted to find more genes linked to ASD [127]. The brain’s frontal and parietal cortex frequently exhibit low expression of genes linked to ASD. Notable genes include newly discovered candidates like MYCBP2 and CAND1 and well-known ones like NBEA, HERC1, and TCF20. CNNs and recurrent neural networks are two examples of contemporary DL applications in genomics that improve the analysis of DNA and RNA sequences and forecast mutations’ biological and phenotypic effects, including the single-cell methylation state of CpG dinucleotides. AI can recognize patterns, linkages, and genetic markers that may point to an ASD diagnosis or suggest a person’s predisposition to the disorder by applying ML and DL [128]. These algorithms can navigate the intricate web of genetics and identify minute distinctions between people with and without ASD. This results in more accurate and customized diagnoses. Additionally, AI-driven genomic analysis opens the door to creating early-stage targeted therapies and treatments by helping us decipher the underlying genetic pathways driving ASD Nahas et al. [59], Abdullah et al. [129].

For example, Gök [130] used data on brain-developing gene expression to create a model that used machine learning to perform binary classification of ASD risk genes. The model’s two main parts are discretization, the Haar wavelet transform for feature extraction, and a Bayes network learning algorithm for classification. Using lncRNA gene data, they evaluated the proposed model against a few stand-alone classifiers and current techniques, such as LR, RF, NB, Bayes network, kNN, and linear and polynomial SVM. The 10-fold cross-validation testing methodology was used for the ASD classification problem in all classifier assessments.

A few years later, Wang et al. [131] used ML techniques, particularly RF, to identify ASD using IgA levels and VFGM genes. The research used metagenomic datasets to compare kids with TD (n = 31) and ASD (n = 43). According to the data, there is a correlation between IgA levels and VFGM gene diversity, which is more significant in ASD. Most of the 24 VFGMs that distinguished between TD and ASD were attributed to genes related to the group B streptococcus (GBS). The study found nine important virulence factors utilizing the Random Forest approach. These included five unique GBS genes (like YP_329683.1) and four non-GBS genes (like kfiC, pvdM, mtrE, and hasA). Additionally, in 2021, Lin et al. [132] examined ASD-specific gene expression, enabling prospective subsequent detection by predicting ASD risk genes and identifying the temporospatial areas of brain structures at different developmental stages. Employing the BrainSpan atlas, the research analyzed a dataset spanning 13 developmental stages from eight weeks post-conception to eight years over 26 different brain regions. The proposed work utilized the SVM technique to differentiate ASD risk genes from non-ASD genes. It used the transmissible bi-objective combinatorial genetic algorithm for the best feature selection, improving the model’s performance. At 13 post-conception weeks, the posteroventral parietal cortex was the most predictive brain area for genes.

Alsuliman and Al-Baity [133] explored two datasets: the GE dataset, which contains gene expression data from 30 samples with 43,931 features differentiating ASD and non-ASD cases, and the PBC dataset, from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) that contains 292 samples and 20 features related to ASD diagnosis and personal details. The high dimensionality of the datasets was addressed in the study by optimizing feature selection using a combination of bio-inspired algorithms and machine learning (ML) models to boost classification accuracy. For this goal, we utilized four algorithms: GWO, FPA, BA, and ABC. The models were assessed using AUC, recall, accuracy, precision, and F1-score. Out of all the models suggested the GWO-SVM model had the best performance, with an accuracy of 99.66%.

More recently, Suratanee and Plaimas [134] created a differential gene expression profile utilizing gene expression data and a gene embedding profile, which incorporated intricate gene connections using the data to determine disease-related genes for ASD. They utilized these profiles and the XGBoost classifier to find new connections for ASD. The proposed method found 10,848 putative gene–gene connections and 125 candidate genes, with the top three possibilities being DNA Topoisomerase I, ATP Synthase F1 Subunit Gamma, and Neuronal Calcium Sensor. They used statistical analysis to assess these candidate genes regarding specific pathways and activities. Additionally, they discovered sub-networks inside the prospective gene network, which aided in identifying association subgroups for putative genes linked to ASD.

A summary of the studies related to the eye tracking data is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

A summary of works using AI techniques for detecting ASD by analyzing genetic data.

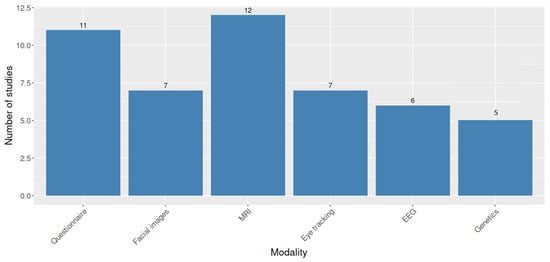

To summarize, we provide a plot showing the number of works in our review related to each modality. Figure 3 allows to distinguish the most used modalities and then, estimate their contribution to detecting or classifying ASD. Based on these results, we can observe that MRI and questionnaire are the most used modalities for detecting ASD in our study, with 12 and 11 works, respectively.

Figure 3.

A bar plot with the number of works in our review related to each modality.

5. Popular Datasets for ASD Detection or Classification

This section describes some popular ASD-related datasets relative to the various modalities available in the current literature.

- MRI datasets. The ABIDE I and ABIDE II datasets are open-access and publicly available, consisting of resting state fMRI (r-fMRI) data samples or regional and total brain characteristics of the brain connectome. The ABIDE I dataset, launched in 2012, consists of a total of 1112 samples collected from over 17 various global sites, including 539 ASD and 573 typical control participants that are aged from 7 to 64 years. The ABIDE II launched in 2016, with contributions from 19 locations, provided a total of 1114 samples with enhanced phenotypical data, including 521 ASD people and 593 additional longitudinal samples from 38 people, who were participants aged 5 to 64 years. The major limitation of the ABIDE I dataset for ASD is the imbalanced distribution of gender (male and female). For instance, over 85% of participants are male, reporting a 4:1 male-to-female diagnosis ratio. This gender inequality makes it difficult for AI models to detect ASD accurately in females since girls may determine distinct brain patterns and behaviors. As a result, models instructed on commonly male data may not behave well in real clinical settings where gender differences are more balanced [135]. Additionally, the dataset is taken from specific high-income countries, resulting in biases for similar human races or regions lacking diversity. Further, the data samples taken belong to humans of specific age groups, which reflects a need first to increase the data samples as they are quite low and require targeting a larger age group to improve the effectiveness of these datasets. Lastly, the quality of data samples can differ based on the imaging technology used by the institute from which it is taken and collectively can affect the preprocessing, impacting the model’s performance upon training [38,136].

- Questionnaire datasets. The Autism Screening on Adults dataset, ASD children traits dataset, and Autism Screening data for toddlers datasets are all publicly available on Kaggle. All these datasets consist of ASD Questionnaire-based responses filled out by parents or caregivers of autistic individuals using the ASD Test application. The autism screening on the adult dataset consists of 21 attributes and a total of 704 participants in the age group of 17–64 years. The ASD children traits dataset consists of 19 attributes and 1054 instances where the age range of the participants is from 12 to 36 months. The Autism Screening data for toddlers dataset comprises 1985 instances and 28 attributes. The age range of participants consists of 1 to 18 years. These datasets have a few limitations; first, the datasets have been developed by compiling user responses. It is analyzed that few outliers exist within these datasets caused by typing errors or user mistakes while entering data, causing a lack of data integrity. The datasets are limited to detailed information as they consist of a few questions but do not include any attributes regarding medical ASD tests carried out by experts like MRI or EEG signals, which lowers the impact of ASD classification. Moreover, all these datasets consist of class imbalance in terms of data samples as these datasets consist of fewer samples of ASD patients and more instances of non-ASD individuals, making it less effective for ASD detection [137,138]

- The eye tracking dataset. The eye tracking dataset is an open-source resource publicly available in the Figshare repository. It was created to assist researchers in further research on ASD by sharing detailed records of gaze behavior in children. The dataset comprises 59 participants and is limited to children aged 3 to 12 years, including ASD and TD participants, collected from educational institutions in Hauts-de-France. The gender distribution of participants was 64% male and 36% female. Eye movements, such as fixations and saccades, pupil diameter, and point-of-gaze coordinates, have been recorded for each participant utilizing a screen-based SMI RED-M eye tracker at a sampling rate of 60 Hz. At the same time, this dataset provides valuable opportunities for ASD researchers to explore more research on ASD detection using it. However, limitations exist, such as small sample size, limited diversity, gender imbalance, and potential measurement errors [139,140].

- NDAR dataset. The National Database for Autism Research (NDAR) is a scalable and adaptable data informatics platform that facilitates research on ASD. Data from all layers of biological and behavioral structures, such as synthetics, genes, brain tissue, personality, and relationships with the environment and society, are supported. Different sorts of data are also supported by NDAR, including text, pictures, time series, and numerical values, as NDAR consists of multi-dimensional data types like behavioral data, genetic data, and neuroimaging data that may be in raw format. It adds more complexity to data analysis; therefore, extensive data preprocessing techniques are required to develop benchmark datasets requiring higher computational resources like GPU. Moreover, the datasets are limited to fewer samples and need more diversity, adding biases towards specific human races and age groups [141,142].

- SFARI dataset. The SFARI Autism Inpatient Collection dataset was released in 2013 and consists of behavioral and genetics-based samples belonging to ASD individuals with 527 instances. Some limitations are found in the SFARI dataset. First, the number of instances of this dataset is significantly low and requires more data samples. The genetic dataset is based on the socioeconomic and demographic factors of participants from specific countries with different diagnosis criteria for individuals with ASD, limiting overall diversity and generalizability. Moreover, the behavioral dataset consists of missing values as data is collected via parents and caregivers so human error can reduce data integrity [143,144,145].

- EEG datasets. The P300 speller KAU dataset is an open-source dataset by King AbdulAziz University KSA, and the dataset consists of two categories: one is the global dataset for autism disorder, and the global P300 speller dataset consists of EEG samples of individuals with ASD and people without neurological disorders. Ten boys, ages 9 to 16, who are not diagnosed with any neurological impairments make up the control group; eight boys, ages 10 to 16, represent the ASD group. The BCIAUT_P30 dataset was launched in 2020 and is freely available on Kaggle; comprising of EEG recordings developed for the Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system based on the P300, it contains 105 individual recordings of data from 15 people diagnosed with ASD, collected throughout seven sessions. The main limitation of EEG datasets is the lack of data diversity and demographic imbalances [146] since they contain very few EEG recording samples, only from the male gender. Moreover, the EEG samples belong to a particular age group, causing bias based only on inclination to that age group. Lastly, the EEG samples are pretty challenging to extract. They are prone to making noise during recording due to interactions with other electromagnetic waves, adding distortion, which requires advanced preprocessing techniques to remove and enhance data quality [147,148,149]. Overall, these problems can reduce a model’s performance and generalization to real-world settings.