Abstract

Risk assessment and management during the entire production process of a radiopharmaceutical are pivotal factors in ensuring drug safety and quality. A methodology of quality risk assessment has been performed by integrating the advice reported in Eudralex, ICHQ, and ISO 9001, and its validity has been evaluated by applying it to real data collected in 21 months of activities of 18F-FDG production at Officina Farmaceutica, CNR-Pisa (Italy) to confirm whether the critical aspects that previously have been identified in the quality risk assessment were effective. The analysis of the results of the real data matched the hypotheses obtained from the model, and in particular, the most critical aspects were those related to human resources and staff organization with regard to management risk. Regarding the production process, the model of operational risk had predicted, as later confirmed by real data, that the most critical phase could be the synthesis and dispensing of the radiopharmaceuticals. So, the proposed method could be used by other similar radiopharmaceutical production sites to identify the critical phases of the production process and to act to improve performance and prevent failure in the entire cycle of radiopharmaceutical products.

1. Introduction

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is a nuclear medicine technique used mostly for the diagnosis, staging, and follow-up of cancers [1]. 18F-FDG is the most widely used radiopharmaceutical in PET clinical investigations; it is used in over 95% of the PET examinations performed [2].

Over the years, alternative radiopharmaceuticals to 18F-FDG have been studied, but research in this environment is complex due to the high costs for development (from 20 to 60 million dollars in 2013), the long period for development (minimum 7–9 years) [3], and high risk (one new radiopharmaceutical for clinical use out of ten thousand molecules tested at the beginning) [4].

18F-FDG will still be the most used radiopharmaceutical in nuclear medicine for years to come, although there are malignant diseases with poor uptake of F-FDG and other benign diseases that could cause false positives [5].

The radiopharmaceutical industrial production requires compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP): the guidelines for GMP implementation are enclosed in Volume 4 of the Eudralex “The rules governing medicinal products in the European Union” [6].

The GMP rules should be applied to all phases of a drug’s life cycle, starting from clinical trials through technology transfer and production until the final product’s retirement [6].

The Eudralex also suggests the use of other guidelines, among which ICHQ 10 guidelines (ICHQ:International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) were finalized at setup for the pharmaceutical quality system (PQS) to be applied throughout the product life cycle.

ICHQ10 guidelines recommend the integration of the GMP regulations with the ISO 9001:2015 quality concepts related to the whole process [7], with the aim of harmonizing the entire production cycle of the drug.

A key aspect of the PQS is represented by Quality Risk Management (QRM), as described in another ICHQ guideline (ICHQ 9) [8].

In fact, to date, QRM has assumed a pivotal role in the (radio)pharmaceutical industries for the assessment, control, and communication of the risks associated with product safety and quality.

The literature reports several cases of QRM applied to radiopharmaceutical production, which are mostly applied to segments of the production process but not to the whole process [9,10,11] or are intended to prevent injury to the operators or patients [12] but without quantification of the risk throughout the product life cycle.

The analyzed literature also shows that the integrated application of some quality standards, such as GMP, ISO 9001, ICHQ, and EFQM (European Foundation for Quality Management), could contribute to obtaining the quality of a radiopharmaceutical [13] through quality risk assessment and guaranteeing performance and efficacy in the entire process.

Therefore, the application of different quality standards, such as GMP, ISO 9001, and ICHQ, guarantees the quality and safety of a radiopharmaceutical [13] and contributes to optimizing the performance and efficacy of the entire production process.

This paper describes the conceptualization and the setting up of a quality risk assessment methodology to be applied to the production of sterile PET radiopharmaceuticals under the GMP regulations.

This methodology has been developed in our public research institution, taking into consideration all phases of the product life cycle, starting from development, passing through technology transfer, and finally, commercial delivery.

This methodology of quality risk management has been performed by integrating the recommendations reported in Eudralex, ICHQ, and ISO 9001, and its validity has been evaluated by applying it to real data collected in 21 months of activities of 18F-FDG production at Officina Farmaceutica, CNR-Pisa (Italy), to confirm whether the critical aspects, which have previously been identified in the quality risk assessment, were effective.

2. Materials and Methods

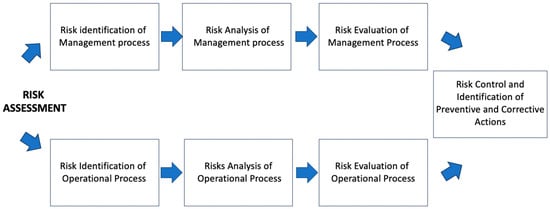

The quality risk assessment has been carried out, highlighting criticalities at both management and operational levels. The flowchart in Figure 1 shows the rationale applied to develop the methodology.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of quality risk assessment methodology to be applied to production of sterile PET radiopharmaceuticals under GMP regulations.

Our institution is authorized to manufacture radiopharmaceuticals for diagnostic use (2-18F fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose and 18F-Fluoromethylcholine) with marketing authorization, and it is also authorized to produce fluorinated radiopharmaceuticals intended for clinical trials.

Synthesis and dispensing of 18F-FDG are carried out in a classified room in accordance with annex 1 of the EU; the raw materials and the finished product enter and leave the clean room bypass through ventilated boxes.

Inside the clean room, there are five shielded cells and a Class A class isolator equipped with a Class B transfer chamber. The shielded cells contain three automatic synthesis modules. Briefly, the production of 18F-FDG is carried out with the fully automated IBA Synthera® multipurpose synthesizer, and the radiopharmaceutical is then dispensed into the single vials through the semi-automatic fractionation system, which is equipped with a dose calibrator. The product is dispensed in a grade-A environment and filtered through a 0.22-micron Millipore filter. After dispensing, the filter integrity is verified using the Bubble Point test system. The quality control of the finished product is made in an unclassified environment equipped with the instrumentation for chemical-physical and microbiological (content of bacterial endotoxins) tests.

2.1. Organizational and Management Risk Assessment

For the assessment of organizational and management risks, a matrix has been developed to identify the factors that influence the production of radiopharmaceuticals. These factors have been identified considering the indications contained in the ISO 9001: 2015 standard, which is considered a golden standard for the management of an organization. For each requirement of the ISO 9001 standard, we asked ourselves a number of questions, and based on the answers, we identified the relative risks. The aspects taken into consideration were the context of Organization, Leadership, Planning, Support, Operating Activities, Performance evaluation, and Improvement.

Table 1 reports management risks individuated based on the ISO 9001:2015 standard.

Table 1.

Risks identification of the management process.

Each identified risk was analyzed and defined as irrelevant, tolerable, moderate, effective, or intolerable by examining the impact of the risk on the production process and the probability of occurrence. Table 2 shows the risk quantification matrix.

Table 2.

Matrix for risk quantification, risk index.

Based on the obtained score, corrective and preventive actions have been identified to mitigate the risk. The actions were identified according to the criterion shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Corrective and preventive actions based on risk index.

2.2. Operational Risks

To assess the operational risk, a similar approach has been used, but rather than ISO9001, the Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA) methodology was used according to ICH Q9 because FMEA is able to identify and help us understand the risk sources, their causes, and their effects on the system by assigning priorities and implementing corrective actions to address the most serious risks.

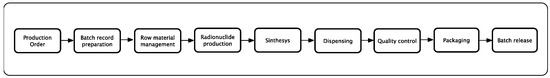

At the beginning, the production process was divided into the main activities and then each identified activity was analyzed for the identification of the risks. Figure 2 shows the main process subdivided into the principal activities.

Figure 2.

Principal activities of the main process.

For each step of the process, the most critical operations were identified, and the risks were quantified by evaluating the severity, detectability, and probability of occurrence according to the criteria reported in the following tables, attributing 3 points to a severe risk, 2 points to a medium risk and 1 point to a not-relevant risk (see Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 4.

Severity.

Table 5.

Probability of occurrence.

Table 6.

Detectability.

By multiplying the severity of the damage (S) with the probability of occurrence (O) and the detection index (D), the risk index was obtained according to the formula RI = SxOxD.

Based on the risk index (RI) calculated, 3 different risk categories are individuated:

Risks with indexes 27, 18, and 12. They are high risk (NOT acceptable) and require immediate mitigation action.

Risk with index 9 or 6 medium risk: requires corrective actions to be implemented as soon as possible (days).

Risk with index from 4 to 1: low risk; they may require improvement actions to be implemented in the medium–long term (annual planning).

3. Results

Table 7 and Table 8 show the results of risk assessment defined as the “Risk Index” performed based on theoretical analysis of the entire production cycle divided into management (Table 7) and operational process risks (Table 8).

Table 7.

Risk assessment of the management’s risks.

Table 8.

Risk assessment of the operational process. The green scale represents the severity of risk.

The most critical activities (productivity, reliability, non-conformities) were analyzed as suggested in Chapter 1 of the EUGMP guidelines Volume 4 for a period of 21 months of activity of the production site after restart.

The results of these analyses are summarized in the following figures.

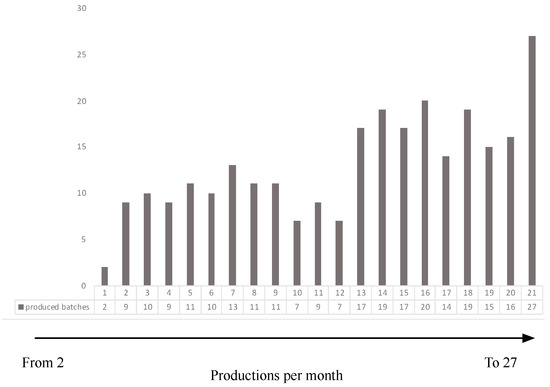

The first analysis concerns the productivity of the site evaluated through the number of productions/months. Figure 3 shows that over those 21 months, the productivity went from 2 productions per month to 27 productions per month.

Figure 3.

Increase in productivity.

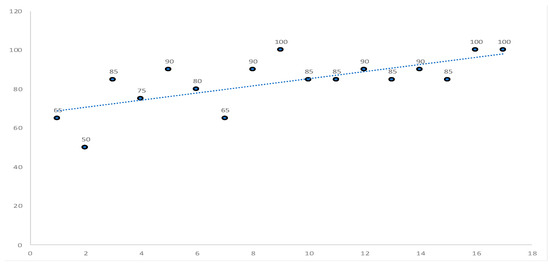

Regarding reliability evaluation, the collected data were grouped into 17 slots of 20 productions, and for each slot, the reliability percentage value was calculated using the following formula: Reliability = scheduled lots/released lots × 100.

The average reliability is 84%, and the trend is positive, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Increase in reliability over time (each circle represents the % scheduled lots/released lots).

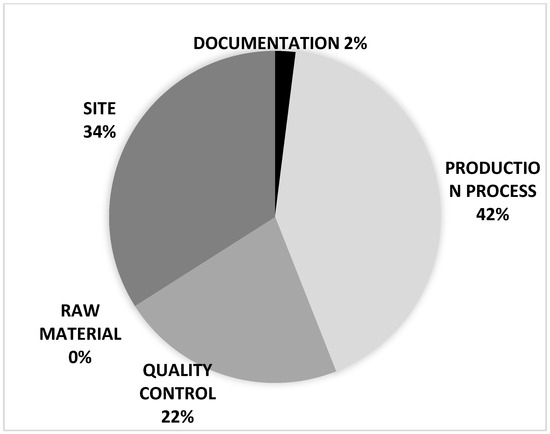

All non-conformities (n = 143) were recorded in the 21-month period and were analyzed in accordance with the internal procedures that contemplate a classification related to the items reported below:

- Production process deviations;

- Quality control deviations;

- Raw material deviations;

- General site deviations;

- Documentation deviations.

Figure 5 shows how non-conformities are distributed within these five areas.

Figure 5.

Non-conformities distributed within these 5 areas.

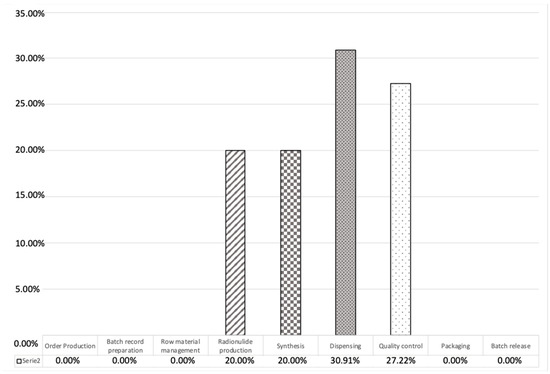

To verify if the risk assessment process had correctly identified the most critical segments of the process, we further subdivided the registered non-conformities along the entire production process as scheduled in Figure 6 (main steps process), as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Percentage distribution of registered non-conformities along the entire production process steps.

We have also quantified the impact of the non-conformities on the three types of failures identified during the risk assessment: product quality, personnel safety, and sustainability.

In general, the risk to the quality of the product never occurred because the system was able to detect potential risks to product quality, including with sterility control. To guarantee the sterility of the finished product, specific actions are adopted to ensure that the entire production chain takes place in quality assurance conditions, despite the test result being available to the patient at least 15 days after the injection.

For the operator risk, the data analysis shows that the most critical process is the dispensing in 8.6% of non-conformities; radioactive material has leaked out, especially inside the shielded isolator, due to incorrect assembly of the sterilization filter. This aspect was carefully monitored, and corrective actions were taken, which led to risk mitigation. Another risk for operator safety is the breaking of the vial in the delivery channel (1.2% of non-conformities), but also, in this case, the radioactivity monitoring systems have effectively detected the contamination, and the automatic locking systems for the opening of the cells have prevented the contamination of the operator.

As regards the failure to sustainability, the failure to release the lot generally had an important impact on the site’s sustainability.

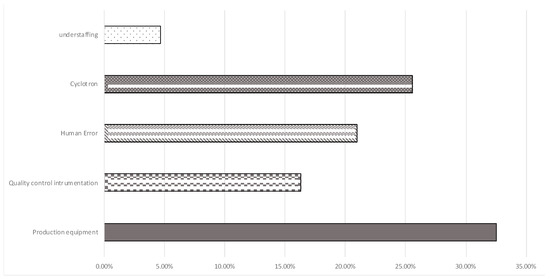

Figure 7 shows the main causes of the rejection of a lot of radiopharmaceuticals.

Figure 7.

Main causes of lot rejection.

4. Discussion

In general, the radiopharmaceutical manufacturing process starts with the production of the radionuclide and continues with the synthesis of the radiopharmaceutical according to the formulation described in the Marketing Authorization (MA) dossier or Pharmacopoeia Monograph [14].

The production of PET radiopharmaceuticals is extremely complex due to a series of factors [15]: the delivery of the final product that takes place with the sterility control still in progress; the short half-life of the tracer; the very high number of batches produced compared to conventional drugs; the activity carried out mainly during the night; and the handling of radioactive substances. The complexity of this system implies that risk assessment is even more necessary than in other production systems.

Fortunately, the GMP standard helps us keep the critical aspects of the production process under control by indicating the tools to be used “to manage” the risk [16,17].

Our GMP experience has allowed us to develop a risk assessment, which is conducted by separately considering organizational and management risks and operational risks.

This report describes the experience of a public radiopharmaceutical site that has adopted the GMP standards and which, therefore, produces radiopharmaceuticals following the indications of the EU-GMP for industrial production [18]. Since the start of GMP radiopharmaceutical production, the site has used an approach founded on risk-based thinking and followed regulatory updates over the years.

In 2021, the production site radically changed the production process, moving from production with final sterilization in an autoclave to production using aseptic techniques. Before starting with the new production process, a risk assessment was carried out, which identified the most critical segments of the process. Twenty-one months after the restart of the production, which was intended for distribution on the national territory, the data that emerged were collected and analyzed to verify if the risk assessment process carried out ex ante had been able to identify the main risks.

Compared to the initial risk assessment, the evidence collected during these twenty-one months allows us to state that the method, adopted both for the assessment of management risks and operational risks, is a suitable tool for identifying the critical phases of the process.

At the managerial level, the greatest criticality was mainly linked to personnel management.

The results of the analysis also show that production is the most critical phase of the process (asepsis and radioactivity). In particular, the dispensing phase has proven to be the most critical, implying a delay or even a loss of production along with customer dissatisfaction. In addition, there are problems during the dispensing phase; as an example, the breakage of a product vial could result in personal and environmental contamination and put an operator’s safety in danger (Table 2).

In general, the preventive actions to be undertaken to mitigate the risk can be grouped into two main types: the continuous training of staff, with attention to motivation and awareness of the complexity of the system, and the increasingly detailed processes so that the risks can be reduced as much as possible and, therefore, achieve an overall risk reduction.

In conclusion, having a risk management process in place is critical for GMP production facilities, and the identification of risks in the matrix is a useful tool. Our implemented model has identified and quantified the risks, and, given the overlap between the risks identified and the analysis of real data, the proposed method could be used by other similar radiopharmaceutical production sites to identify the critical phases of the production process, improve the performance, and prevent damages to the entire cycle of the radiopharmaceutical product.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P., G.I. and L.G.; methodology, A.Z., S.P. and M.T.; software, M.Q.; validation, M.T. and A.Z.; formal analysis, M.P. and M.Q.; investigation, G.I. and L.G.; data curation S.P. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, G.I. and L.G.; visualization, L.G.; supervision L.G. and G.I.; project administration, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boellaard, R.; Delgado-Bolton, R.; Oyen, W.J.; Giammarile, F.; Tatsch, K.; Eschner, W.; Verzijlbergen, F.J.; Barrington, S.F.; Pike, L.C.; Weber, W.A.; et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: Version 2.0. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 42, 328–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chierichetti, F.; Pizzolato, G. 18F-FDG-PET/CT. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 56, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaw, R.C.; Tamagnan, G.D.; Tavares, A.A.S. Rapidly (and Successfully) Translating Novel Brain Radiotracers From Animal Research Into Clinical Use. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerella, S.G.; Singh, P.; Sanam, T.; Digwal, C.S. PET Molecular Imaging in Drug Development: The Imaging and Chemistry Perspective. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 812270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.L.; Binzel, K.; Zhang, J.; Knopp, M.V. Advanced Functional Tumor Imaging and Precision Nuclear Medicine Enabled by Digital PET Technologies. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2017, 2017, 5260305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vol 4 EU GMP (Guidelines for Good Manufacturing Practices for Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use—Pharmaceutical Quality System). Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/eudralex/eudralex-volume-4_en (accessed on 8 October 2003).

- ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System—Scientific Guideline. 2015. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q10-pharmaceutical-quality-system-scientific-guideline (accessed on 28 May 2014).

- ICH Q9 Guideline of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH Q9). 2015. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-q9-quality-risk-management-scientific-guideline (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Lange, R.; ter Heine, R.; Decristoforo, C.; Peñuelas, I.; Elsinga, P.H.; van der Westerlaken, M.M.; Hendrikse, N.H. Untangling the web of European regulations for the preparation of unlicensed radiopharmaceuticals: A concise overview and practical guidance for a risk-based approach. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2015, 36, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsinga, P.; Todde, S.; Penuelas, I.; Meyer, G.; Farstad, B.; Faivre-Chauvet, A.; Mikolajczak, R.; Westera, G.; Gmeiner-Stopar, T.; Decristoforo, C.; et al. Guidance on current good radiopharmacy practice (cGRPP) for the small-scale preparation of radiopharmaceuticals. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitto, G.; Di Domenico, E.; Gandolfo, P.; Ria, F.; Tafuri, C.; Papa, S. Risk assessment and economic impact analysis of the implementation of new European legislation on radiopharmaceuticals in Italy: The case of the new monograph chapter Compounding of Radiopharmaceuticals. Curr. Radiopharm. 2013, 6, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dondi, M.; Torres, L.; Marengo, M.; Massardo, T.; Mishani, E.; Ellmann AV, Z.; Solanki, K.; Bischof Delaloye, A.; Estrada Lobato, E.; Nunez Miller, R.; et al. Comprehensive Auditing in Nuclear Medicine through the International Atomic Energy Agency Quality Management Audits in Nuclear Medicine Program. Part 2: Analysis of Results. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 47, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanDuyse, S.A.; Fulford, M.J.; Bartlett, M.G. ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System Guidance: Understanding Its Impact on Pharmaceutical Quality. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monograph for (18F) Fludeoxyglucose Injection; Working Document QAS/17.733; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Hansen, S.B.; Bender, D. Advancement in Production of Radiotracers. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 53, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todde, S.; Kolenc Peitl, P. Guidance on validation and qualification of processes and operations involving radiopharmaceuticals. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2017, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillings, N.; Hjelstuen, O.; Behe, M.; Decristoforo, C.; Elsinga, P.H.; Ferrari, V.; Kiss, O.C.; Kolenc, P.; Koziorowski, J.; Laverman, P.; et al. EANM guideline on quality risk management for radiopharmaceuticals. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 49, 3353–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillings, N.; Hjelstuen, O.; Ballinger, J.; Behe, M.; Decristoforo, C.; Elsinga, P.; Ferrari, V.; Kolenc Peitl, P.; Koziorowski, J.; Laverman, P.; et al. Guideline on current good radiopharmacy practice (cGRPP) for the small-scale preparation of radiopharmaceuticals. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2021, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).