Abstract

This article provides answers to the question of how Generation Z perceives various quality characteristics in connection with paper straws. The aim of this study was to analyze the advantages and disadvantages of paper straws from three perspectives: intrinsic quality characteristics, sensory perception, and physical characteristics. A total of 215 young adults and 65 students aged up to 27 years took part in the field study and sensory analysis, respectively. The field survey revealed that Serbian Gen Z prefers and expects paper straws do not contribute to the flavor of the drink, have a rounded and dull edge, and not change their shape when dipped into the drink. The sensory panel was formed by selecting students based on the results of several sensory screening tests conducted in the initial phase. Sensory testing for the difference showed that the impact of paper straws of different diameters on flavor was limited, although it was confirmed that artificial saliva could easily coat the surfaces and penetrate the layers of the paper straws, resulting in a significant loss of firmness and a greater potential to adhere to the lips. No effects were found on the sweetness, sourness, pungency, and overall flavor of the soft drink. Viscosity was the only attribute that was affected. The soft drink was perceived as more viscous when using the narrower straw than when using the larger diameter straws. Artificial saliva and water were the liquids that had the greatest influence on the loss of firmness of the soaked straws. After 20 min of exposure to most of the liquids tested, the paper straws were found to lose over 75% of their firmness. Paper straws are more sustainable and have the potential to completely replace plastic straws. However, their physical properties, especially firmness, need to be further improved, considering that they can be soaked in liquids for more than 20 min when consuming various beverages.

1. Introduction

One of the issues of environmental concern is the management of food packaging waste, with straws playing a recognizable part in this impact. Some scientists estimate that eight million tons of plastic, including plastic straws, end up in the oceans [1]. Assuming that the average European produces 180 kg of waste per year, the European Union (EU) has set a target to reduce packaging waste by 15% by 2040, promote the reuse/refill of packaging, and develop a new generation of fully recyclable packaging by 2030 [2]. A recent study on food packaging waste in Serbia shows that each household throws away 70 pieces of different types of food packaging per week [3], with plastic waste predominating. To tackle food packaging waste, the EU has started to crack down on single-use plastic plates, cutlery, and straws that are only used once and then thrown away [4]. As the directive came into force in July 2021, it is expected to reduce waste from the top 10 single-use plastic products by more than 50% [5]. Plastic straws are considered one of the biggest pollutants [6]. There is no clear data on the production volume of plastic straws. Some scientists estimate that over 150 million plastic straws are thrown away every day in the USA alone [7]. Other authors quote a range between 170 million and 490 million straws per day [8]. However, Hirschlag [9] of the BBC disputes that the estimate of 500 million straws per day is a statistical ad from 2011 that was used by some multinational companies to promote paper straws as more sustainable. As for paper straws, this market is worth over 1.5 billion USD worldwide [10] and continues to grow, considering the ban on single-use plastic products in some countries and regions such as the US, the EU, and Australia.

Geyer et al. [11] estimate that 9% of plastic waste is recycled, 12% is incinerated, and the rest remains in landfills (and in nature). Therefore, various natural materials such as bamboo, sugarcane, corn, rice, wheat, and paper are used in the straw industry to promote its biodegradable potential [7]. In Malaysia [12], South Africa [13], and the United States of America [14], the environmental aspects of paper straws have been studied mainly through a life cycle assessment.

Serbia is not part of the EU, but its intention to become part of this union was recognized as a national priority as of 1 March 2012 [15], when the European Council granted Serbia the status of an EU candidate. As a result, many efforts are being made to harmonize food-related legislation, and it is expected that plastic food packaging regulations will soon be on the harmonization agenda. In parallel, Serbia has set its targets for (food) waste and (food) packaging waste in line with the 2030 Agenda [16].

In contrast to the environmental impact described above, straws play an important role in the consumption of various types of beverages, especially in food establishments. These establishments include bars, cafés, restaurants, fast food, and other places where food and beverages are sold to the public [17]. Several studies have found that consumer satisfaction in food establishments consists of three pillars—the environment (external and internal physical environment), the quality of service, and the quality/safety of the food and beverages served [18,19]. In terms of target groups and generations, Beekman et al. [20] studied the effects of straws (including paper straws) on iced coffee drinks with 75 healthy adults aged between 18 and 55 years. Jonsson et al. [7] conducted an online survey on straw preferences on six continents, with the majority of the population being young (43% under 24 years), while the consumer test conducted in the USA included 102 participants aged 18–69 years.

Generation ‘Z’ (Gen Z), born between 1995 and 2010, makes up almost a third of the world’s population [21]. As it is the largest global consumer group, it has the potential to change consumer behavior and consumption patterns in the food sector [22]. Hanifawati et al. [23] explain that Gen Z, born in the digital age, is influencing the hospitality industry with their specific perceptions, behaviors, and preferences in food and beverage consumption. The oldest members of this generation are currently young adults at the beginning of their careers, and they represent the modern consumer. The modern consumer recognizes the negative consequences of their behavior and tries to avoid them [24]. Gen Z consumers are open to new consumption patterns and styles and are transforming from consumer hedonists to morally responsible, environmentally conscious consumers who avoid unnecessary purchases and choose products that do not harm the environment [25]. They are developing into a sustainable generation and show a strong preference for sustainable brands. More than sixty percent of Gen Z opt for sustainable brands and base their purchasing decisions on personal, social, and environmental values [26]. They can also be seen as sustainability torchbearers, as they encourage older generations to place more emphasis on sustainability in their purchasing decisions.

With regard to straws, only a few quality dimensions have been investigated so far, such as the influence of straw size on the perceived amount of beverage consumed [27] using 4-mm and 12-mm straws and asking 36 participants to quantify perceived water consumption using the two types of straws; emotional responses of 163 respondents to different sensory characteristics of cold tea [6] using the check-all-that-apply method with 39 emotional terms offered and comparing different sensory and physical tests of different types of straws [7] using 9-point hedonic scales and check-all-that-apply ballots. Gen Z was not specifically the focus of these studies.

Currently, plastic straws are still the most commonly used in Serbia, although a shift towards environmentally friendly materials is expected, with paper straws predominating. These straws are mostly made of food-grade paper materials bonded with food-grade adhesives. There are two working hypotheses: (i) paper straws influence the sensory perception of the beverages consumed, and (ii) the physical characteristics of the straws change during consumption. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to analyze the potential of using paper straws for Gen Z from different perspectives: their sensory perception, their physical properties, and their intrinsic quality characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminary Data Collection

Before starting the survey, the students visited 50 food establishments (bars, cafés, fast food restaurants) near the Faculty of Agriculture in Belgrade—the capital of Serbia—and collected all types of straws offered to consumers. The results showed that plastic straws are still predominant (83.3%), but almost 20% of the establishments visited also offer biodegradable paper straws.

2.2. Field Survey

A questionnaire was developed to analyze the perceptions of young adults (up to 27 years of age) regarding the intrinsic quality characteristics of straws. The first part only recorded gender as a demographic characteristic, as the study focuses on the younger generation. In the second part, respondents were able to indicate which quality characteristics they considered most and least important. For this purpose, nine characteristics (Table 1) were taken from the work of Jonsson et al. [7]. They were randomly divided into seven subgroups of four characteristics (Table 2), and each respondent rated all subgroups.

Table 1.

Nine intrinsic quality characteristics.

Table 2.

Model of a subset of quality characteristics. All respondents were asked to indicate which of the four characteristics presented they considered most and least important.

2.3. Beverage and Drinking Straw Samples

Three different soft drink concentrates from local producers were used to prepare the beverage samples. Apple concentrated syrup (beverage sample ‘A’) with the following ingredients: apple juice concentrate (40 ± 2%), sugar, water, citric acid, vitamin C, apple flavor (dry matter 65–67%; pH 3.1–3.3). Elderflower concentrated syrup (beverage sample ‘E’) with the following ingredients: sugar, water, elderflower (min 7%), citric acid (dry matter 65–67%; pH 2.6–3.0). Orange flavored instant granulated drink fortified with nine vitamins (beverage sample ‘O’) with the following ingredients: sugar, citric acid, sodium hydrogen carbonate, natural orange flavor, vitamin C (plus eight additional vitamins), and acacia gum.

The beverage samples were prepared from the soft drink concentrates using low-mineral bottled water and served in disposable white polypropylene (PP) 200 mL cups in the amount of 75 mL per cup. Randomly ordered 3-digit numbers were used to code the samples.

Paper straws (20 cm long) with four different outer diameters were used for the study: Ø6, Ø8, Ø10, Ø12 (mm).

2.4. Sensory Testing

All sensory tests were performed in the sensory testing laboratory at the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Belgrade.

2.4.1. Difference Tests

In order to examine the influence of the drinking straw diameter on the sensory perception of soft drinks, three different forced-choice sensory tests were applied. The tests were adjusted for the purpose of the study.

The sensory panel consisted of 65 students (up to 27 years of age) briefly screened for acuity by performing basic taste detection tests (sour, sweet, salty, and bitter) and discrimination tests for sour and sweet tastes, according to ISO 8586:2014 [28]. Only the students who fully met the testing criteria were recruited.

2.4.2. Difference Test #01 (Overall Difference Test)

Difference test #1 was performed with the Ø6 and Ø10 paper straws as a modified duo-trio test. Two separate sessions were conducted, one using soft drink sample ‘A’ (apple) and the other one using drink sample ‘O’ (orange). Beverage samples were prepared from the concentrates according to the manufacturers’ instructions: apple syrup was diluted with water in a ratio of 1:5 by mass, while orange-flavored granules were mixed with water in the amount of 75 g per liter of soft drink. Sixty assessors participated in both sessions. Each session was performed in the way that each assessor was presented with three samples simultaneously: one was marked as a reference, and the other two were coded. All three contained the same beverage sample, which was the information hidden from the assessors. The reference was served without a drinking straw, while two coded samples were tested by using straws of different diameters (Ø6 or Ø10). Coded cups were covered with aluminum foil in order to mask the appearance of test beverages, and the assessments were performed by puncturing the cover foil with straws. The task was to indicate which coded sample matches the reference (with the chance probability of one in two). The null hypothesis stated that there is no difference in the overall perception of a soft drink when tasting by using drinking straws of two different diameters.

2.4.3. Difference Test #02 (Overall Difference Test)

Beverage samples were prepared from elderflower concentrated syrup (‘E’) in three different concentrations with a syrup-to-water ratio by mass: 1:5.8 (syrup concentration of 14.8% w/w); 1:5.0 (16.7% w/w); and 1:4.4 (18.6% w/w). The sample with a central concentration of 16.7% w/w was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and taken as a reference. Concentrations for the other two samples were determined experimentally by applying the triangle test for the difference. A panel, consisted of 16 assessors chosen from the University staff with experience in sensory evaluation, performed several sessions of triangle test evaluating perceptible difference between reference concentration and concentrations slightly higher than the reference (syrup to water ratios by mass: 1:4.8; 1:4.6; 1:4.4). Sequential test was used as a mathematical tool for the data analysis and the first tested concentration that the panel could distinguish from the reference (p < 0.05) was taken as a working sample with higher syrup concentration [29]. The lower concentration was proportionally calculated by subtracting the experimentally obtained concentration difference of 1.9% from the reference value.

Difference test #2 was performed by 60 assessors in two separate sessions, one using Ø6 mm and the other one using Ø8 mm paper straws. Each session was performed in the way that each assessor was presented with four samples simultaneously: one was marked as a reference (the beverage sample with central concentration), and the rest were coded (all three prepared concentrations of the soft drink). The reference was served uncovered and without a drinking straw, while the coded samples were covered with aluminum foils and tested by using the straws. The task was to indicate which coded sample matches the reference (with the chance probability of one in three). The null hypothesis stated that the use of a drinking straw does not influence the overall perception of a soft drink. In case of finding differences, the direction of changes in perception would be examined by testing asymmetry in the data set.

2.4.4. Difference Test #03 (Attribute Difference Test)

Difference test #3 was performed by using the Ø6, Ø8, Ø10, and Ø12 mm paper straws in order to test whether the straw diameter influences the perception of the following sensory attributes of a soft drink: sweetness, sourness, overall flavor, viscosity, and pungency. The soft drink (sample ‘O’) was prepared by mixing orange-flavored granules with water in the amount of 75 g per liter of drink, according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The test was done by a sensory panel consisting of 61 assessors. Each assessor was presented with four coded cups covered with aluminum foils, together with the four straws of different diameters. The assessors were not told that the samples contained the same soft drink product. The task was to rank the samples for the degree of the five selected sensory attributes (from lowest to highest intensity) in consecutive assessments. The testing was done according to the procedure described in ISO 8587:2006 [30]. The null hypothesis stated that there is no difference in the perception of the selected attributes when tasting a soft drink by using drinking straws of different diameters. Selection of the attributes was made in separate testing sessions by an eight-member panel from the University staff, using the soft drink samples of different concentrations purposely prepared for the assessment. These sessions were done according to the procedure for term generation in descriptive analysis described by Heymann et al. [31].

2.5. Descriptive Sensory Analysis

Sensory texture and appearance evaluation was conducted on different types of drinking straws 6 mm in diameter by nine staff members from the University of Belgrade experienced in descriptive analysis. Five straw materials were selected for this purpose: metal (food-grade stainless steel), paper, reusable hard plastic, disposable plastic, and biodegradable polyester resins. Two training sessions [31] with different types of straws were performed until the consensus list of eight attributes was created (Table 3). The testing methodology was similar to flash profiling described by Delarue [32]. Straw samples were presented in random order at the same time. The sensory panel rated the selected attributes according to their intensities by directly comparing the straw samples with each other and using unstructured 15 cm line scales. The assessors were instructed to use the intensity scales in their own way.

Table 3.

The list of sensory attributes evaluated in the descriptive analysis of drinking straws made of different materials.

2.6. Physical Testing

Paper straws that are considered biodegradable were subjected to a three-point bend test. This test was performed on Brookfield CT3 Texture Analyzer using the normal test with a trigger of 0.05 N, deformation of 10.0 mm, and speed of 5.0 mm/s. The following variants were employed—dry straw ‘S’, straws soaked in water ‘W’, and straws soaked in different food simulants ‘A’ (ethanol 10% v/v—refer to contact with aqueous foods pH > 4.5), ‘B’ (3% acetic acid—refer to contact with acidic foods pH < 4.5), ‘C’ (50% ethanol—refer to contact with dairy products) and ‘D’ (95% ethanol—refer to contact with high-fat content food) as outlined in the EU Regulation EC 10/2011 [33] and ‘E’ (artificial saliva © Apoteka Beograd). The food simulants were prepared at room temperature (22 °C–26 °C). The soaking time was 20 min, as suggested by Jonsson et al. [7], to analyze the effect of liquid on the durability of the straws. All tests were performed in five replicates. The data were further processed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test to distinguish statistical differences between different soaked straws of the same diameter (p < 0.05).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Nominal sensory data obtained in overall difference tests were analyzed by using binomial distributions and tables for chance probabilities of 1/2 and 1/3 as described in ISO 5495:2005 [34] and ISO 4120:2021, [35], respectively. Initially, the sensitivity of the tests was set as follows: (test #1; p0 = 1/2; two-tailed) α = 0.05, β = 0.20 and pd = 0.36; (test #2/p0 = 1/3) α = 0.05, β = 0.05 and pd = 0.31 (where p0 is chance probability and pd is the proportion of discriminators chosen for the tests). The Friedman test and the least significant ranked difference test for complete block designs (α = 0.05) were used to analyze the ranked data [30].

Descriptive data were first tested for the significance of discrimination among the straw samples (α = 0.05). The data were standardized by attributes for each assessor and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), with ‘assessors’ as random factors. The raw descriptive data of the attributes that significantly discriminated among the samples, grouped by assessors, were first subjected to Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA) to obtain a set of consensus data. Dimension reduction was performed by applying Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the consensus data matrix obtained.

Since presented intrinsic characteristics may be chosen as most important or least important, initial processing consisted of counting the number of times a certain characteristic has been selected. Based on the counting, the “S” score has been computed (Equation (1)) in line with the works of Merlino et al. [36] and Djekic et al. [37].

M—Most frequently chosen; L—Least frequently chosen; a—availability in the series of seven sets (in our case attribute “smooth touch” was available in four sets, all other characteristics were available three sets); n—number of respondents.

In addition, two other indicators were derived: ‘M − L%’ (showing percentages of characteristics selected as most important, as least important and not selected) and ‘preference share’ outlining the likelihood that an attribute is identified as the most important [38]. In addition, the χ2 test for association was employed to discover potential relationships between genders for the most important and the least important characteristics. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

Statistical programs used for data analysis were SPSS Statistics 17.0 (IBM) and XLSTAT 2022.3.2 (Addinsoft).

3. Results and Discussion

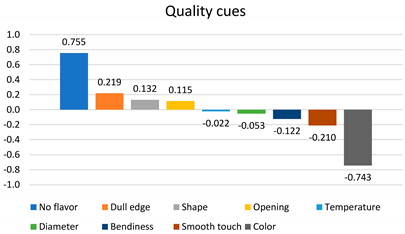

3.1. Analysis of Most and Least Important Characteristics

A total of 215 young adults participated in the survey, with female respondents outnumbering male respondents (68.4% female vs. 31.6% male respondents). Table 4 shows respondents’ subjective prioritization of intrinsic quality characteristics. The ability of straws not to add flavor to the beverage consumed was identified as the most important quality attribute (‘S’ score = 0.755), followed by ‘dull edge’ (‘S’ score = 0.219). These characteristics were contrasted with the ‘color’ of the straws (‘S’ score = −0.743) and ‘smooth touch’ (‘S’ score = −0.210) as the least important attributes. Within the subset of choices, ‘no flavor’ was selected as the most important attribute almost 80% of the time when the attribute was included in the subset of choices. Its share of preference to be selected as the most important attribute is one-third (33.75%). This survey confirms the study by Jonsson et al. [7] in which the same attribute was identified as a “must have” in their Kano model. Both genders chose the same most/least important attributes. There was a statistically significant difference in terms of the patterns of the nine intrinsic characteristics for the most important attributes selected (χ2 = 18.052; p < 0.05) but not for the least important attributes.

Table 4.

Subjective priority of the quality characteristics of paper straw: Most-least scaling report—frequency counts and standardized, average value taking into account the entire sample (N = 215).

3.2. Effects of Paper Straw Diameter on Sensory Perception

The results of several sensory difference tests conducted did not indicate any meaningful effect of paper straw diameter on the perception of the soft drink samples used in the experiment. The only exception was the perception of ‘viscosity.’

The two overall difference tests (#1 and #2) did not show that the use of straws can lead to differences in the way the soft drink can be perceived (p < 0.05). Of the 60 responses obtained in each of the two test sessions conducted with apple and orange soft drinks in Test #1, the sample with the Ø6 straw was selected by 33 assessors, and the sample with the Ø10 straw by 27 assessors in both cases. From the number of consensual responses (33), it can be concluded that there is no statistical difference between the effects of Ø6 and Ø10 paper straws on the change in sensitivity to the stimuli produced by the same soft drink, even at α = 0.20 (allowing for a reduction in β-risk and pd). No difference was found in the overall perception of the beverage samples when tasted with paper drinking straws of the two selected diameters. The results of Test #2 also showed that the use of paper drinking straws with the selected diameters had no effect on the overall perception of the soft drink used. There were 30 correct responses in the Ø6 paper straw test and 27 correct responses in the Ø8 paper straw test, out of a total of 60 in both cases. Thus, the proportion of correct responses in both cases was significantly higher (α = 0.05) than the chance probability of one in three. This indicates that the assessors were able to identify the reference sample among the coded samples and that the use of a paper straw did not affect the sensitivity to the perception of the soft drink tested.

Testing for differences in sweetness, sourness, overall flavor, viscosity, and pungency was conducted by 61 assessors using the ranking method in a complete block design. The four selected paper straws with diameters of Ø6, Ø8, Ø10, and Ø12 mm differed significantly (p < 0.05) only with respect to ‘viscosity.’ The perceived intensity of the viscosity of the soft drink tested was significantly higher when using the Ø6 straw than the Ø10 and Ø12 straws. This could be due to the greater force required to push the liquid into the mouth through the narrower straw than with a larger diameter straw. There were no statistically significant differences between Ø8, Ø10, and Ø12 straws in terms of effects on the perception of the soft drink ‘viscosity.’ Pramudya et al. [6] studied the effects of five different straw materials (plastic, paper, copper, stainless steel, and silicon, with an inner diameter of 6 mm) on sensory responses toward cold tea beverages. In evaluating the overall flavor, bitterness, sourness, sweetness, and astringency intensities of the tea samples, the different types of straw materials used were not found to significantly affect sensory responses. A significant difference was found only in terms of sourness and only between silicon and copper (with slightly higher ratings for the former).

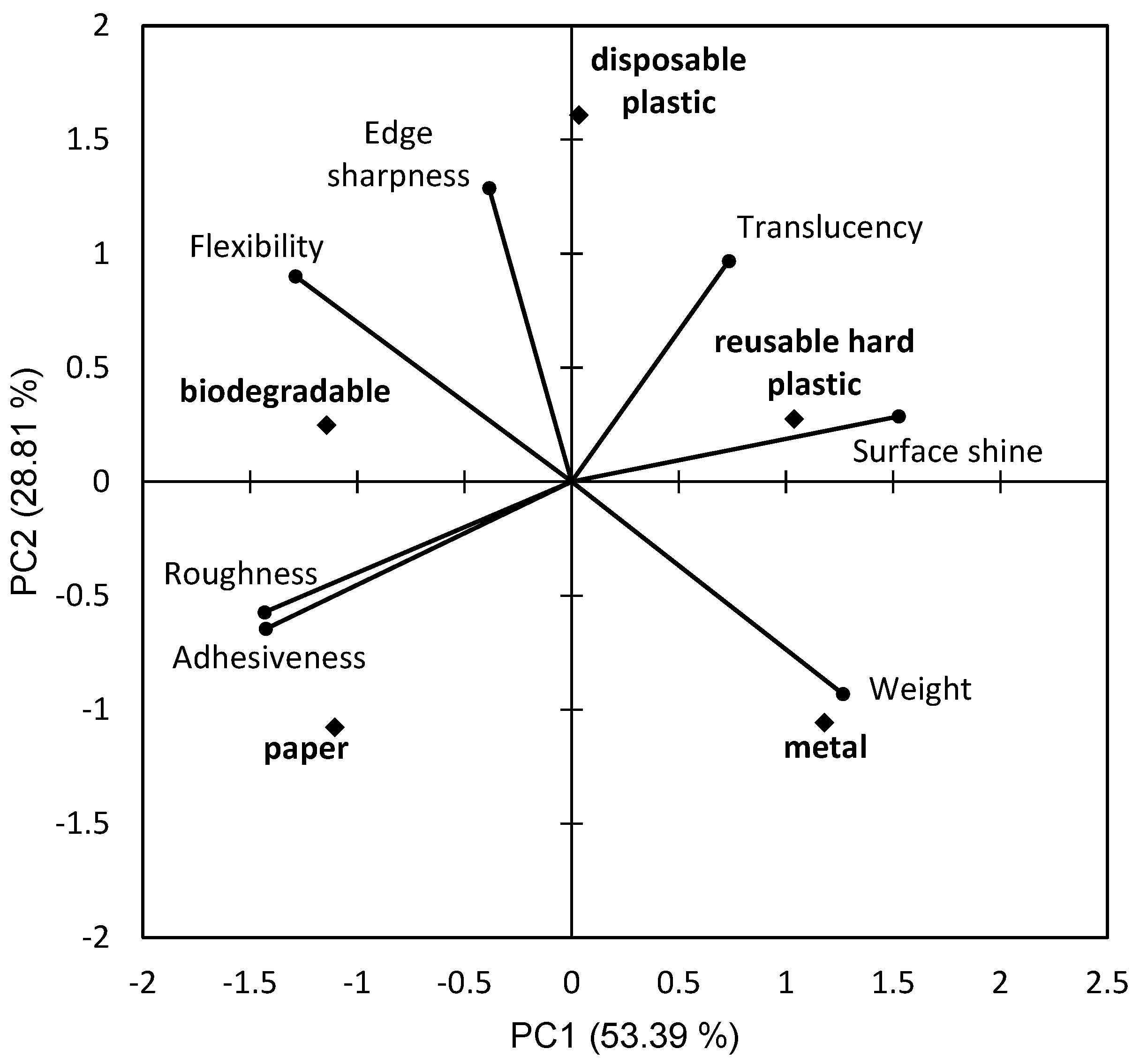

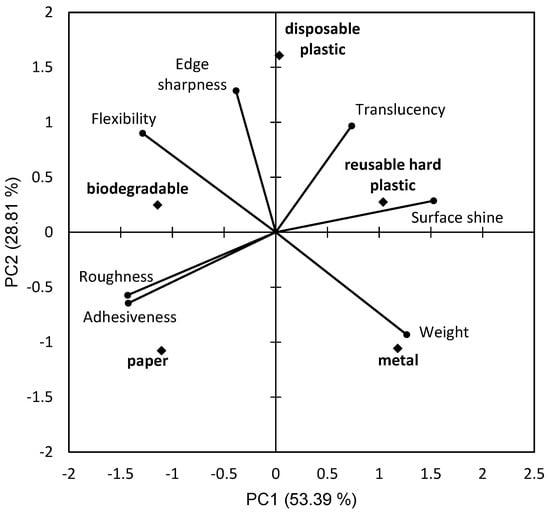

3.3. Descriptive Analysis of Different Straw Materials

The results of descriptive sensory analysis of drinking straws made of different materials are shown in Figure 1. The first two extracted principal components explained 82.2% of the variance in original data values. Five original variables were strongly correlated with PC1 (PC1-loading values greater than 0.6), while the remaining two had high PC2 loadings (Table 3). Disposable plastic straw has prominent edge sharpness, translucency, and flexibility. Keeping in mind that the ‘dull straw edge’ was one of the most important quality cues according to a survey conducted with young adults, another sample with pronounced edge sharpness was biodegradable polyester straw. There was no statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between disposable plastic and biodegradable straws in edge sharpness. On the other hand, hard plastic, metal, and paper straws showed the same perceptible level of edge sharpness (p > 0.05), which was significantly lower compared to disposable plastic and biodegradable straws. Paper and biodegradable straws are represented by rough surfaces, higher adhesiveness to wet lips, higher flexibility, and less surface shine compared to the other straw samples. Hard plastic and metal straws are characterized by pronounced surface shine and weight, with a low rate of flexibility, surface roughness, and adhesiveness. Surface roughness was significantly higher in paper and biodegradable straws than in the remaining three, but it should be noticed that ‘smooth touch’ was not judged as an important attribute of drinking straws by surveyed young adults. Springiness was not included in the dimension reduction statistical analysis since the metal straw could not be evaluated according to this attribute. There was no perceptible difference in springiness among disposable plastic, biodegradable, and hard plastic straws. They possess a certain level of springiness in contrast to paper straws that showed almost no recovery at all after the bite force was stopped.

Figure 1.

Biplot of the first two principal components extracted by applying principal component analysis on the consensus data matrix obtained by subjecting the sensory descriptive data of drinking straws made of different materials to Generalized Procrustes Analysis. Legend: PC—principal component.

3.4. Texture Analysis of Paper Straws

The texture analysis (Table 5) showed that at diameter Ø6, straws ‘A’ and ‘E’ had the lowest values and were statistically different from ‘B’ and ‘C’ (p < 0.05). Other results showed that ‘W’ and ‘E’ were statistically different from ‘C’ and ‘D’ (p < 0.05; Ø8), with ‘A’, ‘C’, and ‘D’ (p < 0.05; Ø10) and with all other straws (p < 0.05; Ø12). As the results show, artificial saliva and water had the strongest effect on the firmness of the straws with diameters Ø8, Ø10, and Ø12. Apparently, artificial saliva and water easily coated the surfaces of the straws and destabilized the interaction between the water-based adhesive that holds the layers of paper material together. With the exception of straw ‘D’, the loss of firmness was more than 75% for all other soaked straws.

Table 5.

Physical characteristics of the paper straws.

The loss of firmness of soaked paper straws is mainly caused by the porosity of the cellulose fibers, which easily absorb moisture when in contact with various beverages, especially acidic or hot drinks [8]. However, for beverages such as milk and other beverages containing lipids (food simulant ‘D’), fats as non-polar molecules penetrate the paper material due to their high hydrophobicity, contributing to protective and hydrophobic functionality. This interaction probably affects the physicochemical properties of straws by forming strong, attractive interactions (hydrogen bonds) between the head group of the lipid and the hydroxyl group of the cellulose molecules [39].

Deformation at peak shows the distance to which the sample was compressed when the peak load occurred. The results show that the distance is between 7.2 ± 1.7 and 9.9 ± 0.1 mm for Ø6, between 7.7 ± 1.0 and 9.9 ± 0.1 for Ø8, between 7.1 ± 1.4 and 9.9 ± 0.1 for Ø10 and between 7.0 ± 0.9 and 9.9 ± 0.1 for Ø12. Except for Ø8, for all other diameters, the smallest ‘deformation at peak’ value was observed for ‘D’ straws (p < 0.05).

The preliminary investigation revealed that the different beverages served in the food service establishments range from water to cocktails, juices, and dairy products. ‘A’ straw is used for sweet drinks with a high sugar/honey content, ‘B’ for various types of clear drinks (cider, fruit/vegetable juices, lemonades, syrups, bitters, coffee, tea, energy drinks), ‘C’ is associated with clear drinks and alcoholic beverages (alcohol content between 6%vol and 20%vol), ‘D’ stands for cloudy drinks (juices and nectars as well as soft drinks with fruit pulp and liquid chocolate), alcoholic beverages (alcohol content over 20%) and all cream liqueurs [33]. ‘E’ stands for artificial saliva, as it is common for some consumers to hold the straw in their mouth. Finally, the ‘W’ straw stands for the group of water drinks (both still and carbonated).

In the study on straws made of different materials and their effects on emotional and sensory responses to cold tea, Pramudya et al. [6] found that cold tea received higher ratings for both overall and flavor hedonic impressions when metal straws (stainless steel and copper) were used compared to paper straws. Considering that they found no significant difference in the perception of all flavor notes rated (overall taste, bitterness, acidity, sweetness, and astringency), it is likely that the acceptability of cold tea was influenced by the characteristics of the straws. Drawing parallels with the results of this study, it could be hypothesized that characteristics such as higher adhesion to wet lips, higher flexibility, no springiness (no recovery after deformation under pressure), as well as soaking abilities and loss of firmness after soaking, influenced the lower acceptability of paper straws compared to metal straws.

3.5. Practical Application

The results of this study provide interesting conclusions regarding paper straws depending on the role of the interested party in the life cycle of the straws. First, it provides straw manufacturers with insights on how to improve the quality of straws from a textural point of view and preserve the physical properties during consumption (no shape changes during use, limited changes in firmness when the same straw is used over a longer period of time). Secondly, it can help food establishments understand the expectations of Gen Z when serving different beverages with this type of straw. And finally, it can serve as a guide for scientists with some methodological tips for conducting sensory analyses with different types of straws and beverages.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated paper straws from various aspects, such as the types of straws mainly consumed by Gen Z, their perceptions of the intrinsic quality characteristics of straws, sensory analysis of various soft drinks consumed with the straws, evaluation of the texture and appearance of the straws, and their physical testing. The overall results show that Gen Z does not highlight any flavor effect of the straws as well as a dull edge and shape during use. The paper straws with different diameters had no effect on the overall perception and flavor notes of the soft drink. A certain difference was only found in the perception of viscosity, with the soft drink being perceived as more viscous when using the narrower straw than when using the wider straws. The first working hypothesis was therefore not confirmed, as the paper straws did not have a major influence on the sensory perception of the drinks consumed.

Artificial saliva and water had the greatest influence on the loss of firmness of the soaked straws, as the cellulose fibers easily absorb water, while the saliva could additionally break the bonds between the water-based adhesives and the paper layers. At the same time, the paper straws lost more than 75% of their firmness after 20 min of exposure to most liquids, which can be attributed to the formation of a cellulose-lipid complex. This confirms the second working hypothesis that paper straws lose their physical characteristics over time. Despite these results, this study confirms that paper straws have great potential to replace plastic straws as they do not alter sensory perception.

One limitation of the study was that only soft drinks were used for the sensory analysis. Future research should focus on other types of beverages, such as coffee-based drinks or carbonated soft drinks, to pave the way for defining the optimal quality characteristics of paper straws.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D. and N.T.; methodology, N.T., I.D. and T.P.; validation, N.T.; formal analysis, T.P., B.U. and N.S.; investigation, T.P., B.U. and N.S.; resources, N.T. and I.D.; data curation, N.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D. and N.T.; writing—review and editing, all co-authors; visualization, N.T., N.S. and B.U.; supervision, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The participation of human subjects in the sensory studies conducted was in accordance with the Code of Professional Ethics of the University of Belgrade [40].

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants. Consent was not obtained in written form as the study only included a simple anonymous sensory evaluation of consumer acceptance and perception of selected sensory attributes of soft drinks. The soft drink concentrates, mineral water, and drinking utensils were of standard commercial quality and were purchased at the local market. Participants were informed about the purpose and protocol of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, L.; Tan, J. An integrated sustainability assessment of drinking straws. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. European Green Deal: Putting an End to Wasteful Packaging, Boosting Reuse and Recycling; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Djekic, I.; Miloradovic, Z.; Djekic, S.; Tomasevic, I. Household food waste in Serbia—Attitudes, quantities and global warming potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Directive 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 189, 17. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Turning the Tide in Single-Use Plastics; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pramudya, R.C.; Singh, A.; Seo, H.-S. A sip of joy: Straw materials can influence emotional responses to, and sensory attributes of cold tea. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, A.; Andersson, K.; Stelick, A.; Dando, R. An evaluation of alternative biodegradable and reusable drinking straws as alternatives to single-use plastic. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 3219–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.N.; Royals, A.W.; Jameel, H.; Venditti, R.A.; Pal, L. Evaluation of paper straws versus plastic straws: Development of a methodology for testing and understanding challenges for paper straws. BioResources 2019, 14, 8345–8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschlag, A. Plastic or Paper? The Truth About Drinking Straws. BBC News. 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20231103-plastic-or-paper-the-truth-about-drinking-straws (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Fortune. Paper Straw Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis, by Material (Virgin Paper and Recycled Paper), by Product (Printed and Non-Printed), by Application (Foodservice and Household), and Regional Forecast, 2024–2032; Fortune Business Insights: Pune, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moy, C.-H.; Tan, L.-S.; Shoparwe, N.F.; Shariff, A.M.; Tan, J. Comparative study of a life cycle assessment for bio-plastic straws and paper straws: Malaysia’s perspective. Processes 2021, 9, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitaka, T.Y.; Russo, V.; von Blottnitz, H. In pursuit of environmentally friendly straws: A comparative life cycle assessment of five straw material options in South Africa. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1818–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.L.; Wan, Y. Life cycle assessment of environmental impact of disposable drinking straws: A trade-off analysis with marine litter in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 153016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smigic, N.; Rajkovic, A.; Djekic, I.; Tomic, N. Legislation, standards and diagnostics as a backbone of food safety assurance in Serbia. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republika Srbija. Srbija i Agenda 2030—Mapiranje Nacionalnog Strateškog Okvira u Odnosu na Ciljeve Održivog Razvoja; V.R.S.-R.s.z.j., Editor Republika Srbija: Belgrad, Serbia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Djekic, I.; Smigic, N.; Kalogianni, E.P.; Rocha, A.; Zamioudi, L.; Pacheco, R. Food hygiene practices in different food establishments. Food Control. 2014, 39, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barber, N.; Goodman, R.J.; Goh, B.K. Restaurant consumers repeat patronage: A service quality concern. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Kane, K.; Tomic, N.; Kalogianni, E.; Rocha, A.; Zamioudi, L.; Pacheco, R. Cross-cultural consumer perceptions of service quality in restaurants. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 46, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekman, T.L.; Huck, L.; Claure, B.; Seo, H.-S. Consumer acceptability and monetary value perception of iced coffee beverages vary with drinking conditions using different types of straws or lids. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Lu, W. Gen Z Is Set to Outnumber Millennials Within a Year; Bloomberg: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, M.-H.; Lv, W.Q. US sustainable food market generation Z consumer segments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifawati, T.; Dewanti, V.W.; Saputri, G.D. The role of social media influencer on brand switching of millennial and Gen Z: A study of food-beverage products. J. Apl. Manaj. 2019, 17, 625–638. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk-Spiewak, K. Nowoczesne technologie—Wyzwanie dla współczesnych konsumentów. Stud. I Mater. Pol. Stowarzyszenia Zarz. Wiedza/Stud. Proc. Pol. Assoc. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 52, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jaciow, M.; Wolny, R. New Technologies in the Ecological Behavior of Generation Z. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 4780–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FirstInsight. The State of Consumers Spending: Gen Z Influencing All Generations to Make Sustainability-First Purchasing Decisions; The Baker Retailing Center at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.-M.; Lo, H.-Y.; Liao, Y.-S. More than just a utensil: The influence of drinking straw size on perceived consumption. Mark. Lett. 2013, 24, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8586:2014; Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 16820:2019; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Sequential Analysis. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 8587:2006; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Ranking. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Heymann, H.; King, E.S.; Hopfer, H. Classical Descriptive Analysis. In Novel Techniques in Sensory Characterization and Consumer Profiling; Varela, P., Ares, G., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Delarue, J. Flash Profile. In Novel Techniques in Sensory Characterization and Consumer Profiling; Varela, P., Ares, G., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EC. European Regulation No 10/2011 of 14 January 2011 on Plastic Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food; O.J.o.t.E.U., Editor European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 5495:2005; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Paired Comparison Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 4120:2021; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Triangle Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Merlino, V.; Borra, D.; Girgenti, V.; Dal Vecchio, A.; Massaglia, S. Beef meat preferences of consumers from Northwest Italy: Analysis of choice attributes. Meat Sci. 2018, 143, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Nikolić, A.; Uzunović, M.; Marijke, A.; Liu, A.; Han, J.; Brnčić, M.; Knežević, N.; Papademas, P.; Lemoniati, K.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic effects on food safety—Multi-country survey study. Food Control 2021, 122, 107800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlbacher, A.C.; Kaczynski, A.; Zweifel, P.; Johnson, F.R. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: An overview. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurtovenko, A.A.; Mukhamadiarov, E.I.; Kostritskii, A.Y.; Karttunen, M. Phospholipid-Cellulose Interactions: Insight from Atomistic Computer Simulations for Understanding the Impact of Cellulose-Based Materials on Plasma Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 9973–9981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senate of the University of Belgrade. The Code of Professional Ethics of the University of Belgrade. Off. Gaz. Univ. Belgrade 2016, 193, 16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).