Abstract

Agile software development prioritizes customer satisfaction through the continuous delivery of valuable software. However, integrating user experience (UX) evaluations into agile projects remains a significant challenge. Existing proposals address specific stages that apply UX evaluation methods but do not fully consider UX artifacts or UX events for integrating user experience into agile processes. To address this gap and support teams, we propose FRAMUX-EV, a framework for evaluating UX in agile software development using Scrum. FRAMUX-EV introduces seven UX artifacts: (1) UX evaluation methods, (2) UX design system, (3) UX personas, (4) UX responsibilities and roles, (5) UX evaluation repository, (6) UX backlog, and (7) UX sprint backlog; and four UX events: (1) pre-planning UX meeting, (2) pre-review UX meeting, (3) weekly UX meeting, and (4) weekly user meeting. The first version of the framework was developed using a seven-step methodology with a qualitative approach. A survey of 34 practitioners validated the usefulness and ease of integration of FRAMUX-EV components, yielding positive results. These findings suggest the potential of FRAMUX-EV as an interesting proposal for integrating UX into agile software development.

1. Introduction

Agile software development has become an increasingly popular practice among companies of various sizes. This approach emphasizes the frequent delivery of valuable software to ensure customer satisfaction, driven by the efforts of motivated teams [1]. In agile projects, it is important to consider users’ needs and objectives throughout the development process to design and develop a product that fulfills their expectations. However, integrating user experience (UX) into agile approaches presents significant challenges, as various issues arise when attempting to align these two disciplines [2,3,4]. This challenge is further compounded by the fact that even Scrum, the most widely used agile approach [5], lacks clear guidance on incorporating UX activities, UX evaluation methods, or UX roles. Moreover, Scrum does not address how to involve representative users effectively [6,7].

Our research on UX evaluation in agile software development revealed a lack of approaches specifically tailored for this integration. While several proposed approaches outline specific evaluation steps and methods aimed at achieving this goal, existing proposals focus on certain stages where evaluation methods are applied. However, they do not fully consider UX artifacts or UX events to effectively integrate UX into agile processes. For this reason, the development of a framework that incorporates UX events and UX artifacts to support UX evaluation in agile software development will benefit both UX and development teams. This will enable them to create high-quality products that take into account the user’s perspective, including their needs, pain points, and goals.

We propose FRAMUX-EV: a FRAMework for evaluating the User eXperience in agile software development using Scrum. FRAMUX-EV was developed using a seven-step methodology, combining different UX evaluation methods and introducing new UX artifacts and UX events. It incorporates seven UX artifacts: (1) UX evaluation methods, (2) UX design system, (3) UX personas, (4) UX responsibilities and roles, (5) UX evaluation repository, (6) UX backlog, and (7) UX sprint backlog. Additionally, it includes four UX events: (1) pre-planning UX meeting, (2) pre-review UX meeting, (3) weekly UX meeting, and (4) weekly user meeting.

A survey was conducted to collect and analyze the perceptions of practitioners. The main objective was to validate the usefulness and ease of integration of UX components (i.e., UX evaluation methods, UX artifacts, and UX events) for evaluating UX in agile software development, specifically within Scrum. In addition, practitioners were encouraged to recommend new components, suggest removing one component, or provide additional feedback. Overall, the UX components in the first version of FRAMUX-EV were positively received by practitioners. Consequently, no UX evaluation method, UX artifact, or UX event was eliminated in this first iteration. However, some refinements are necessary before proceeding with the remaining experiments and validations.

This article is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the theoretical background; Section 3 indicates the need for a UX evaluation framework; Section 4 explains the methodology; Section 5 presents FRAMUX-EV; Section 6 details the validation; Section 7 details the discussions; and Section 8 summarizes the conclusions and outlines future work.

2. Theoretical Background

The concepts of user experience, agile software development, and Scrum are presented below. In addition, related works are analyzed.

2.1. User Experience (UX)

The ISO 9241-210 standard [8] defines UX as “a person’s perceptions and responses resulting from the use and/or anticipated use of a product, system, or service”. Similarly, Schulze and Krömker [9] characterize UX as “the degree of positive or negative emotions that can be experienced by a specific user in a specific context during and after product use and that motivates for further usage”.

In software development, UX plays a critical role in determining overall user satisfaction. A well-designed UX goes beyond ensuring ease of use; it also addresses whether the software meets user needs and expectations. Evaluating UX throughout the development process is essential, as it enables the early detection and resolution of issues before the product reaches the end user [10]. Additionally, a continuous UX evaluation ensures that the product adapts to evolving user needs and expectations.

There are numerous methods available for evaluating UX [11]. These techniques effectively identify issues related to interface design, user interaction, navigation, and usability. However, applying them in agile development environments can be challenging due to time constraints [12,13].

2.2. Agile Software Development

Agile is described as “the ability to create and respond to change, offering a means to navigate and ultimately succeed in an uncertain and turbulent environment” [14]. Sommerville [15] highlights that agile software development focuses on quickly delivering functional software through incremental releases, with each increment introducing new system features. Among various agile approaches, Scrum is the most widely adopted [5]. Other commonly used agile approaches include Kanban, ScrumBan, Extreme Programming (XP), and Lean Startup, among others [5].

Scrum is a lightweight framework designed to help individuals, teams, and organizations deliver value by developing adaptive solutions for complex challenges [16]. To use Scrum effectively and efficiently, it is essential to know and apply the Scrum values and principles, which are reflected in three pillars [16]: (1) transparency, (2) inspection, and (3) adaptation. One of the main features of Scrum is that it has events and artifacts to facilitate software development [16]. The events are (1) sprint planning, (2) sprint, (3) daily meeting, (4) sprint review, and (5) sprint retrospective, while the Scrum artifacts are (1) product backlog, (2) sprint backlog, and (3) increments.

2.3. Related Work

We identified different frameworks that integrated components in their proposal to evaluate UX in agile software development, either through UX artifacts, UX events, UX evaluation stages, or UX evaluation methods (see Table 1). We identified two types of studies: (1) proposals that integrate new elements into an existing agile approach [2,17,18,19,20]; and (2) proposals based on sequential and/or iterative agile activities [21]. These frameworks are usually composed of three to four phases, typically including Scrum events and different UX evaluation methods such as user testing, the rapid iterative testing and evaluation (RITE) method, pair design, paper prototypes, or heuristic evaluation. Although we identified one study that mentioned the presence of a UX artifact [19] and another that referenced a UX event [18], we observed a recurring issue in these studies, as they lacked detailed explanations of how these elements function or how they could be integrated into agile approaches. Therefore, no proposals focused on evaluating the UX throughout the process and phases of agile software development (incorporating all of these components) were found.

Table 1.

Characteristics and limitations of the related works reviewed.

3. Need for a UX Evaluation Framework

Agile approaches are increasingly being used by companies for software development. This iterative development approach helps teams to deliver value to their customers faster and with fewer headaches [22]. Given frequent deliveries, it is important to check that what users need is actually being developed. Therefore, it is necessary to include the UX in agile software development, specifically the UX evaluation, to avoid neglecting the needs of end-users. However, some problems can be observed when integrating and evaluating UX within agile software development:

- Difficulty in selecting the best method: Owing to the large number of UX evaluation methods, it is difficult to understand when it is convenient to apply some evaluation methods [23]. This becomes more difficult in changing and agile environments [24,25,26].

- Users are not actively incorporated: When working in an agile way, teams often neglect to incorporate users to evaluate an idea or decide what to implement. User feedback is often ignored or considered only in specific instances such as sprint reviews [25,27,28].

- Prioritization of design over evaluation: Practices such as software design (user-centered design) are prioritized over evaluation (evaluation-centered evaluation). Thus, the team develops software primarily by considering what users want (functionalities) rather than how they want it (needs and goals) [26].

- Communication problems: There is a lack of communication between the design/UX team and the development team, resulting in misunderstandings in the design and loss of important information [26,27,28].

- Lack of early UX evaluation: In agile software development, it is believed that UX can (or should) be evaluated only in the final stages. Therefore, in the early stages, decisions are made without considering users’ needs [27].

- Difficulty in prioritizing UX work: No backlog is used to highlight user stories focused on UX. In addition, sprint goals are typically focused on development rather than UX, making it difficult to manage and check UX work [25,27].

Most of these problems arise because agile approaches present a set of recommendations or guidelines for iterative development. However, these do not explicitly indicate the tasks or actions that each team must perform to evaluate the UX. For this reason, our study proposes a framework for evaluating UX in agile software development, considering different elements to solve these problems, that is, UX events and artifacts.

4. Methodology

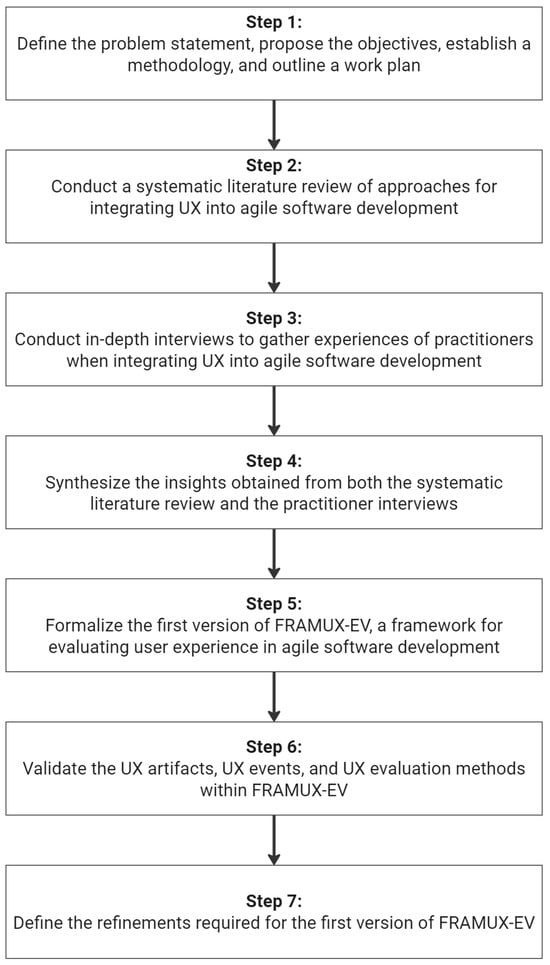

The methodology for developing the framework was divided into seven distinct steps (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Process of developing the framework.

In Step 1, we defined the problem statement, proposed the objectives, established a methodology (including the approach, scope, and steps), and outlined the work plan.

In Step 2, we conducted a systematic literature review of frameworks, methodologies, UX evaluation methods, challenges, and recommendations related to integrating UX into agile software development [29]. We identified different studies that incorporated components of UX evaluation in agile development, focusing on roles, artifacts, events, or evaluation methods. However, no proposals were found that comprehensively evaluated UX across all phases of the agile development process, including UX events, artifacts, and evaluation methods. We identified several UX evaluation methods from these proposals, along with challenges and recommendations related to various UX stages and roles.

In Step 3, we conducted six in-depth interviews to gather and analyze the experiences of various practitioners (e.g., challenges, recommendations, relationships between roles and teams, and adopted practices) when integrating UX into agile software development [30]. Additionally, these interviews were conducted to validate the findings of the systematic literature review. As a result, we identified several methods used for UX evaluation, along with the challenges faced when integrating UX into agile environments, as well as recommendations and practices suggested by practitioners.

In Step 4, we synthesized the insights gathered from both the systematic literature review [29] (i.e., 23 UX evaluation methods, 56 problems, and 91 recommendations) and practitioner interviews [30] (i.e., 9 evaluation methods, 25 problems, and 40 recommendations). A comprehensive comparative analysis was conducted to identify common elements, the most frequently mentioned aspects, novel insights, and notable cases of success or failure. Based on this analysis, some of the most relevant findings were selected to create the initial framework proposal.

In Stage 5, based on the findings from the previous stage, we proposed different UX components to be included in the proposal: 8 UX evaluation methods, 7 UX artifacts, and 4 UX events. This proposal of components resulted in the first version of FRAMUX-EV, a framework for evaluating user experience in agile software development.

In Step 6, we conducted the first validation of FRAMUX-EV to evaluate the usefulness and ease of integration of the proposed UX components (UX artifacts, UX events, and UX evaluation methods) for evaluating UX in agile software development, specifically within Scrum. The validation involved gathering feedback from experts (developers and UX roles) regarding the elements that they suggested adding, modifying, or removing to improve the framework.

In Step 7, we defined the refinements required for the first version of FRAMUX-EV based on the information gathered in the previous step. The experts’ feedback on each component, along with future actions to refine UX events and UX artifacts, is detailed in Section 6.1, Section 6.2 and Section 7.6.

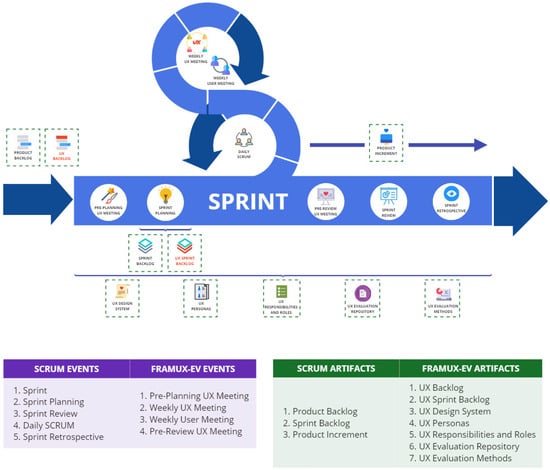

5. FRAMUX-EV: First Version

FRAMUX-EV is a framework for evaluating the user experience in agile software development using Scrum. FRAMUX-EV incorporates seven UX artifacts: (1) UX evaluation methods, (2) UX design system, (3) UX personas, (4) UX responsibilities and roles, (5) UX evaluation repository, (6) UX backlog, and (7) UX sprint backlog. In addition, FRAMUX-EV incorporates four UX events: (1) pre-planning UX meeting, (2) pre-review UX meeting, (3) weekly UX meeting, and (4) weekly user meeting. Figure 2 presents the first version of FRAMUX-EV.

Figure 2.

First version of FRAMUX-EV.

5.1. Inputs

Different inputs were considered when proposing the first version of the framework for evaluating UX in agile software development:

- Systematic literature review: The systematic literature review provided frameworks or similar (e.g., methodologies, processes, or approaches), highlighting 23 UX evaluation methods, 56 problems/challenges, and 91 recommendations/practices, which were taken as a reference to propose new UX components [29].

- Interviews: The interviews with practitioners provided insight into the industry’s perspective, highlighting 9 UX evaluation methods, 25 problems/challenges, and 40 recommendations/practices experienced by UX roles and developers when developing software in agile projects [30].

5.2. UX Evaluation Methods

There are multiple UX evaluation methods that can be used to evaluate the UX in agile software development. We decided to select the eight evaluation methods mentioned in the interviews with practitioners and systematic literature review for the first version of FRAMUX-EV (see Table 2).

Table 2.

UX evaluation methods selected for the first version of FRAMUX-EV.

5.3. UX Artifacts

Based on the findings obtained from the practitioner interviews and systematic literature review, we proposed seven UX artifacts (see Table 3).

Table 3.

UX artifacts proposed for the first version of FRAMUX-EV.

5.4. UX Events

Based on the findings obtained from the practitioner interviews and systematic literature review, we proposed four UX events (see Table 4).

Table 4.

UX events proposed for the first version of FRAMUX-EV.

6. Validating the Framework

We conducted a survey to gather and analyze the perceptions of 34 practitioners (P1–P34) who had worked in UX/UI roles or as developers in agile projects (see Table 5). The survey consisted of four main sections: (1) practitioners’ demographics and agile experience, (2) practitioners’ perspectives on UX evaluation methods, (3) practitioners’ perspectives on UX artifacts, and (4) practitioners’ perspectives on UX events. The main objective was to validate the proposed UX components in FRAMUX-EV using a five-level Likert scale (1—worst to 5—best) in two dimensions: (D1) usefulness and (D2) ease of integration into agile software development. In addition, practitioners were able to recommend new components, suggest the elimination of one component, or provide additional feedback.

Table 5.

Practitioners’ profile and experience.

6.1. Quantitative Results

The following section presents the perceptions of the surveyed practitioners regarding the usefulness (D1) and ease of integration (D2) of the proposed UX evaluation methods, UX artifacts, and UX events for FRAMUX-EV.

6.1.1. Quantitative Results: UX Evaluation Methods

Table 6 summarizes the survey results for dimensions D1 and D2 of the UX evaluation methods proposed in the first version of the FRAMUX-EV. A brief analysis of the descriptive statistics is provided below.

Table 6.

Survey results for dimensions D1 and D2 of UX evaluation methods.

(D1) Usefulness. The UX evaluation method that obtained the best rating from the practitioners was the “usability/user test” with a score of 4.79 out of 5.00. Another UX evaluation method considered useful by the participants was “evaluation with mockups or prototypes”, with 4.26 out of 5.00. On the other hand, the UX evaluation methods with the worst usefulness perceived by the participants were “pluralistic walkthrough” and “system usability scale” with a score of 3.35 out of 5.00. However, although these methods were the worst evaluated, none were rated as “not very useful” (score 2) or “very unhelpful” (score 1).

(D2) Ease of integration. The UX evaluation method considered the easiest to integrate by the practitioners was “evaluation with mockups or prototypes”, with a score of 4.12 out of 5.00, followed by “usability/user test”, with a score of 3.65 out of 5.00. On the other hand, the UX evaluation methods with the worst ease-of-integration ratings assigned by the participants were “pluralistic walkthrough”, with a score of 2.91 out of 5.00, and “RITE method”, with a score of 2.85 out of 5.00. Surprisingly, only one UX evaluation method obtained an average score higher than 4.0 for ease of integration.

Initially, no UX evaluation method should be discarded from this initial version of FRAMUX-EV, as all received a usefulness rating of above 3. However, it is necessary to provide more detailed guidance on how and when the proposed methods should be used, with a particular emphasis on those considered more challenging to integrate into agile environments. The decision to discard UX evaluation methods or provide detailed guidance will be revisited after analyzing the qualitative feedback from the experiment.

6.1.2. Quantitative Results: UX Artifacts

Table 7 summarizes the survey results for dimensions D1 and D2 of the UX artifacts proposed in the first version of the FRAMUX-EV. A brief analysis of the descriptive statistics is provided below.

Table 7.

Survey results for dimensions D1 and D2 of UX artifacts.

(D1) Usefulness. The UX artifact that obtained the best rating from the practitioners was “UX backlog”, with a score of 4.26 out of 5.00, followed by “UX evaluation repository”, with 4.18 out of 5.00. On the other hand, the UX artifacts with the worst usefulness perceived by the participants were “UX personas”, with a score of 3.82 out of 5.00, and “UX responsibilities and roles”, with a score of 3.29 out of 5.00. However, although these UX artifacts were the worst evaluated, none were rated as “not very useful” (score 2) or “very unhelpful” (score 1).

(D2) Ease of integration. The UX artifact considered the easiest to integrate by the practitioners was “UX responsibilities and roles” with 3.91 out of 5.00. Another UX artifact considered easy to integrate by the participants was “UX evaluation methods”, with a score of 3.85 out of 5.00. On the other hand, the UX artifacts with the worst rating assigned by the participants were “UX personas”, with a score of 3.50 out of 5.00, and “UX backlog”, with a score of 3.26 out of 5.00. Although these UX artifacts were the worst evaluated, none were rated as “difficult” (score 2) or “very difficult” (score 1). In addition, none of the UX artifacts were classified as “ease to integrate” (score 4).

Initially, no UX artifacts should be discarded from this initial version of FRAMUX-EV, as all received a usefulness rating above 3. However, it is necessary to provide more detailed explanations of how and when all the proposed UX artifacts can be used, as, surprisingly, none received a score higher than 4. The decision to discard UX artifacts or provide detailed guidance will be revisited after analyzing the qualitative feedback from the experiment.

6.1.3. Quantitative Results: UX Events

Table 8 summarizes the survey results for dimensions D1 and D2 of the UX events proposed in the first version of the FRAMUX-EV. A brief analysis of the descriptive statistics is provided below.

Table 8.

Survey results for dimensions D1 and D2 of UX events.

(D1) Usefulness. The UX event that obtained the best rating from the practitioners was “weekly UX meeting”, with a score of 4.41 out of 5.00, followed by “pre-planning UX meeting”, with a score of 4.09 out of 5.00. On the other hand, the UX events with the worst usefulness perceived by the participants were “pre-review UX meeting” and “weekly user meeting”, with a score of 3.85 out of 5.00. However, although these UX events were the worst evaluated, none were rated as “not very useful” (score 2) or “very unhelpful” (score 1).

(D2) Ease of integration. The UX event considered the easiest to integrate by the practitioners was “pre-review UX meeting”, with a score of 3.97 out of 5.00, followed by “pre-planning UX meeting”, with a score of 3.94 out of 5.00. On the other hand, the UX event with the worst rating assigned by the participants was “weekly user meeting”, with a score of 2.35 out of 5.00. Surprisingly, none of the UX events were classified as “ease to integrate” (score 4).

Initially, all UX events were perceived as useful, and none should be discarded from this initial version of FRAMUX-EV, as each received a usefulness rating above 3. However, it is important to analyze the feedback and suggestions provided by the experts to understand the reasons behind the lower score given to “weekly user meeting”. The decision to discard UX events or modify them to improve their ease of integration will be revisited after analyzing the qualitative feedback from the experiment.

6.2. Qualitative Results

The following section presents feedback and suggestions from the surveyed practitioners regarding the proposed UX evaluation methods, UX artifacts, and UX events for FRAMUX-EV.

6.2.1. Qualitative Results: UX Evaluation Methods

In addition to the methods presented in the survey, 29 additional methods were suggested for consideration. However, almost all the methods mentioned were related to UX design methods rather than UX evaluation methods (e.g., card sorting, tree tests, benchmarks, focus groups, or surveys). The only ones specifically focused on UX evaluation were heat maps (P4, P5, P16, P27), eye tracking (P4, P15), and the five-second test (P5, P21).

Half of the respondents were satisfied with the methods presented, indicating that they would not remove any of the proposed methods (17 of the 34 participants). Meanwhile, the other half were uncertain about whether to remove any method. “A/B testing” was the most frequently mentioned method for elimination, with 6 out of 34 respondents suggesting its removal (P6, P9, P12, P18, P20, P21), followed by the “system usability scale (SUS)”, with four responses (P2, P3, P16, P26). It should be noted that this does not mean that these methods are not useful, but that they may be less applicable or effective in certain situations or contexts (P4, P9, P12, P14).

Participants provided additional comments on the methods presented. For instance, P2 pointed out that “It would be necessary to clarify the methodology you are thinking about for agile software development and what kind of teams you are going to have. The methods will eventually depend on that”. P3 mentioned that “(evaluation methods) must be used at the right time, always proportional to the problem to be addressed”. P15 highlighted that “I find this list quite interesting and complete. They are essential methods with which it is possible to conduct a complete evaluation of the usability and therefore of the user experience”. Table 9 presents the comments obtained.

Table 9.

Additional comments on UX evaluation methods mentioned by practitioners.

In summary, we noted that there are many UX evaluation methods that can be used to evaluate the UX in agile software development projects. However, each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, and it is important to choose the appropriate methods according to the specific objectives of a project (P3, P11). Taking this into consideration, a complete evaluation of usability and user experience can be conducted (P15, P25). Therefore, based on the quantitative and qualitative results, no UX evaluation method will be eliminated from this initial version of FRAMUX-EV.

6.2.2. Qualitative Results: UX Artifacts

In addition to the UX artifacts presented in the survey, 15 additional artifacts were suggested for consideration. However, almost all the suggestions were specifically related to UX design methods rather than UX artifacts (e.g., user scenarios, customer journey, or user flows). The suggestions that could be considered artifacts (e.g., documents, guidelines, and repositories) were the “repository of UX tools” (P5, P20), “KPI guidelines for stakeholders” (P17), and “content repositories” (P4).

The majority of the respondents seemed satisfied with the artifacts presented, indicating that they would not eliminate any of the artifacts proposed (24 of 34 participants). “UX personas” was the most frequently mentioned artifact for elimination, with 4 out of 34 respondents suggesting its removal (P2, P5, P19, P20), followed by the “UX design system”, with three responses (P9, P19, P26).

Although few comments were obtained, there were different opinions regarding the proposal. For instance, P15 and P20 highlighted that it is a “good initiative” and “It is an interesting proposal”, respectively. P24 and P32 highlighted the complexity of the integration and learning of new artifacts in an agile context. Table 10 presents additional comments related to each UX artifact and future actions to be considered.

Table 10.

Additional comments and future actions for UX artifacts.

In summary, there were generally no negative comments regarding the proposed UX artifacts. However, it is necessary to better specify the description of these artifacts to avoid confusion and highlight their usefulness (P2, P5, P14, P15), and to include specific considerations for some of them (P19). Considering this, these improvements will help ensure a clearer understanding and more effective use of UX artifacts in the agile development process. Therefore, based on the quantitative and qualitative results, no UX artifacts will be eliminated from the initial version of FRAMUX-EV.

6.2.3. Qualitative Results: UX Events

In addition to the UX events presented in the survey, 10 additional events were suggested for consideration. The most mentioned events were “UX feedback meeting” (P4, P19, P21) and “daily UX meeting” (P5, P7). Surprisingly, 20 practitioners considered it unnecessary to include any additional UX events beyond those mentioned in the survey.

The majority of respondents seemed satisfied with the events presented, indicating that they would not eliminate any of the artifacts proposed (25 of 34 participants). However, some practitioners suggest eliminating the “pre-review UX meeting” because it is not the right time to do it (P30) and it should be done with the whole team (P19), as well as the “weekly UX meeting”, where it is mentioned that they would not do it weekly (P32) as it is unnecessary (P4) given the time they have within the sprint (P26).

Although few comments were obtained, there were different opinions regarding the proposal. For instance, it was stressed that the “weekly UX meeting” should not have to be weekly as it takes too much time and could be unnecessary (P4, P16, P20, P32). On the other hand, it was mentioned that events and meetings should be held with the entire team (P14, P32). Table 11 presents additional comments related to each UX event and future actions to be considered.

Table 11.

Additional comments and future actions for UX events.

In summary, there were no significant negative comments regarding proposed UX events. However, it is necessary to adjust the frequency of certain events to better align with agile environments (P16, P20, P26, P32). These modifications will ensure that UX activities are seamlessly integrated into agile workflows. Therefore, based on the quantitative and qualitative results, no UX events will be eliminated from the first version of FRAMUX-EV.

7. Discussions

In this section, we explain how to apply FRAMUX-EV in a sprint, in various real-world scenarios, and in other agile contexts or approaches. We include a comparative analysis between FRAMUX-EV and other existing proposals, discuss the challenges in implementing FRAMUX-EV, detail its contributions, and explain the limitations and opportunities for improving FRAMUX-EV.

7.1. How to Use FRAMUX-EV

The integration of UX practices into agile development frameworks, such as Scrum, is essential to ensure that software products meet both functional and UX requirements. FRAMUX-EV, a framework proposed for supporting UX evaluation within agile approaches, provides a flexible approach for integrating UX events and artifacts throughout a Scrum iteration. Below, we outline how FRAMUX-EV can be integrated into the traditional Scrum iteration through dedicated UX events and UX artifacts, ensuring that UX is prioritized along with development tasks:

- Before the sprint planning, the team conducts a pre-planning UX meeting. This event aims to verify whether the prioritized UX work in the UX backlog is ready to be undertaken by the development team during the sprint.

- During the sprint planning, the Scrum team selects items from the product backlog to be developed during the sprint. Simultaneously, the UX tasks from the UX backlog are prioritized and integrated into the UX sprint backlog to ensure that the UX requirements are covered.

- The team meets daily during the daily meeting to track the progress of sprint tasks. During this event, both developers and UX roles ensure that any blockers or impediments in the UX work are promptly resolved. If UX team members have questions about any aspect of their tasks, they can refer to UX roles and responsibilities.

- Once per week, a weekly UX meeting is held, where the UX team and developers discuss the progress of UX design, review updates to the UX components, and resolve issues related to the feasibility of UX designs. In this meeting, potential changes to the UX design system may be reviewed, and the team discusses the evolution of the UX work

- Once per week, a weekly user meeting is held with users to evaluate UX work using some of the methods suggested in UX evaluation methods, discuss upcoming tasks, and obtain direct feedback on ongoing designs. The outcomes of these meetings are documented in the UX evaluation repository for subsequent analysis and refinement.

- Just before the sprint review, a pre-review UX meeting is conducted, where the UX and development teams validate whether the UX designs and functions implemented during the sprint meet the required standards and objectives.

- During the sprint review, the Scrum team presents the product increment, including both development and UX implementations. The UX team can demonstrate how the UX personas, UX design system, and UX evaluation repository guided the final design presented to the stakeholders.

- After the sprint review, the team holds a sprint retrospective to discuss what went well and what could be improved, focusing on both the development and the UX integration aspects. In this event, improvements to UX artifacts, UX events, or UX evaluation methods may be proposed.

In addition, we present practical examples illustrating how FRAMUX-EV components (UX events, UX artifacts, and UX evaluation methods) can be applied across three distinct Scrum team scenarios: (1) a team with only developers and no dedicated UX roles, (2) a small team with both developers and one UX role, and (3) a larger team with multiple developers and UX roles working together. Each scenario demonstrates how UX considerations can be adapted to varying team compositions, ensuring that user-centered design remains a priority (see Table 12).

Table 12.

Application of FRAMUX-EV components across different Scrum team scenarios.

Table 12 highlights the flexibility of FRAMUX-EV, which can be adapted to fit different Scrum team structures by modifying the number of UX evaluation methods, UX events, and UX artifacts incorporated into the workflow. In teams where no dedicated UX role exists, only the core elements, such as the weekly user meeting and key UX evaluation methods, are implemented. This approach empowers developers to integrate user-centered design practices into their projects. Smaller teams with a single UX role may introduce more UX events and UX artifacts, like the weekly UX meeting and pre-review UX sessions, to support ongoing UX improvements. Larger teams with multiple UX roles can adopt the full range of FRAMUX-EV’s UX events and UX artifacts, enabling thorough UX integration across all Scrum iterations. This flexibility ensures teams of any size or level of UX expertise can maintain a strong user focus throughout the project.

While FRAMUX-EV has been proposed for integration with Scrum, its flexible structure allows it to be adapted for use in other agile approaches. For example, Kanban is an agile approach that focuses on continuous workflow rather than using fixed iterations like Scrum. In Kanban, tasks are managed visually on a board, and the goal is to improve efficiency by controlling the amount of work in progress (WIP). To integrate FRAMUX-EV with Kanban, some events would need to be adjusted. Meetings such as the “pre-planning UX meeting” or the “pre-review UX meeting” could be transformed into “milestones” to be reached within the workflow, rather than events that occur before or after each iteration. The “weekly UX meeting” would remain relevant, although it could be adjusted to a more flexible frequency depending on the pace of the work. Artifacts such as the “UX backlog” and the “UX evaluation repository” could also be integrated into Kanban, allowing for visual and continuous management of UX-related tasks.

On the other hand, FRAMUX-EV could also be integrated with the agile approach Extreme Programming (XP). XP places a strong emphasis on close collaboration between developers and clients, with short iterations and a focus on continuous improvement through rapid feedback and small software increments. FRAMUX-EV fits well with XP due to its iterative nature. Events such as the “weekly UX meeting” and the “pre-review UX meeting” can be adapted to the end of each XP iteration, enabling quick and continuous user feedback integration. The “pre-planning UX meeting” can also align with XP’s iteration planning meetings, ensuring that UX tasks are prioritized and worked on alongside functionalities. FRAMUX-EV artifacts such as the “UX backlog” and the “UX sprint backlog” can continue to be used as defined, ensuring that UX tasks align with both technical expectations and user needs.

7.2. Comparison between FRAMUX-EV and Existing Proposals

As mentioned in Section 2.3, we identified six different proposals that integrate various elements for evaluating UX in agile software development [2,17,18,19,20,21]. Table 13 presents a comparison between the six analyzed proposals and FRAMUX-EV, in terms of the components they include (events, artifacts, and UX evaluation methods), the representation mode (whether figures, diagrams, or tables are used to explain the proposal), the validation performed on the proposal, strengths, and weaknesses.

Table 13.

Comparison between existing proposals and FRAMUX-EV.

Of the six proposals analyzed (see Table 13), five do not propose UX events [2,17,19,20,21], and five do not propose UX artifacts [2,17,18,20,21]. Having specific events and artifacts can facilitate the continuous and planned integration of UX evaluation in each agile iteration. In comparison with the proposals by Felker et al. [2], Maguire [17], Argumanis et al. [20], and Gardner and Aktunc [21], which do not include specific UX events or artifacts, FRAMUX-EV introduces seven UX artifacts and four UX-specific events, providing a clear evaluation structure that integrates with Scrum. The inclusion of “weekly UX meetings” and the “UX backlog” allows for iterative and continuous UX evaluation, aligned with agile principles, offering greater flexibility and responsiveness.

Regarding UX methods, most of the proposals analyzed include UX evaluation methods, except for one [18]. The number of methods included in each proposal varies between one and five. FRAMUX-EV includes eight UX evaluation methods, four of which appear in existing proposals (user testing [19,20,21], heuristic evaluation [17], evaluation with mockups or prototypes [2], and the RITE method [2]), and four additional UX evaluation methods (guerrilla testing, A/B testing, pluralistic walkthrough, and SUS), based on the results obtained from the systematic literature review conducted [29] and interviews with practitioners [30]. While Pillay and Wing [18] and Weber et al. [19] offered interesting proposals for evaluating UX within each sprint (including Lean UX principles [18] and various UX evaluation methods [19]), they did not specify when to conduct UX evaluations or how to manage UX work in each iteration. In comparison, FRAMUX-EV provides a clear structure that includes artifacts (such as the “UX evaluation repository” and the “UX sprint backlog”) and events (such as the “pre-planning UX meeting” and the “pre-review UX meeting”), facilitating UX evaluations at key moments in the agile development cycle and providing visibility into UX work.

On the other hand, three of the proposals analyzed have not been validated [2,17,18], while the other three were validated through interviews [19,21]), case studies [19], real projects [20], and questionnaires [21]. FRAMUX-EV was validated through surveys conducted with practitioners who have been working in the industry for several years developing agile projects (see Section 6). FRAMUX-EV, in addition to addressing the deficiencies of previous approaches, adds significant value by formalizing UX activities within Scrum through the introduction of specific artifacts and events. This ensures that UX evaluation becomes an integral part of the agile process, improving collaboration between UX and development teams and enabling faster and more effective feedback in each sprint. The combination of these elements provides a more comprehensive and adaptable framework for evaluating user experience in agile environments.

7.3. Challenges in Applying FRAMUX-EV

The integration of FRAMUX-EV in agile projects can present some significant challenges for different work teams. Introducing new UX events and UX artifacts requires not only adjustments to well-established workflows but also the involvement of the entire team, which can be difficult to guarantee. Teams that are familiar with their current way of working may resist the changes required to adapt to this new proposal. In addition, the time required for these UX activities, in particular the weekly UX meeting and weekly user meeting, could overload already tight sprint schedules, raising questions about their feasibility in agile projects with small iterations.

The framework’s adaptability to different team compositions is another critical factor for its success. FRAMUX-EV must work effectively across different team structures, from those without dedicated UX roles to teams that include multiple UX roles. However, this flexibility introduces a learning curve, as teams will need time to understand and properly apply the UX artifacts and UX events. Furthermore, it can be challenging for teams without UX roles to balance UX and development tasks in the backlog and sprint planning, as developers need to make sure UX tasks get enough focus but without slowing down development activities.

On the other hand, creating and maintaining up-to-date UX artifacts, such as the UX backlog, the UX evaluation repository, and the UX design system, requires the team’s continuous dedication to ensure their relevance and usefulness throughout the project lifecycle. This effort is essential to prevent UX artifacts from becoming outdated given the evolving needs of the project. Finally, user involvement is crucial to the success of FRAMUX-EV; however, obtaining and analyzing user feedback without delaying other activities could be a problem for some teams.

7.4. Contributions

This framework introduces a flexible approach to integrate and support UX evaluation in agile software development using Scrum, addressing a significant gap in the existing literature. It includes new UX components within Scrum by proposing seven UX artifacts and four UX events to ensure that UX activities are constantly integrated throughout the project lifecycle. In addition, FRAMUX-EV suggests eight different UX evaluation methods, offering a wider range of options than previous proposals and increasing flexibility to support different team compositions and sizes, with or without UX roles. Moreover, FRAMUX-EV promotes collaboration between the UX team and the development team by synchronizing efforts and facilitating early feedback, thereby decreasing communication problems. Considering all these UX components, our proposal offers a comprehensive and flexible approach compared to existing approaches for integrating and supporting UX in each iteration throughout an agile project.

7.5. Limitations

This study presents different limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the validation survey was conducted with only 34 practitioners, limiting the generalizability of the results. A larger sample size would offer more robust insights and improve the reliability of the findings. Additionally, since this is the first version of the framework, only one validation has been conducted, and it has not yet been applied in real-world agile software development projects. As a result, its effectiveness and practicality in actual settings remain to be evaluated, leaving a gap between theoretical development and real-world applicability.

Furthermore, the UX events proposed in the framework are specifically designed for use within Scrum, and their applicability to other agile methodologies, such as Kanban or Extreme Programming (XP), has not yet been addressed. However, this limitation primarily applies to UX events, as UX artifacts and UX evaluation methods could potentially be used in other agile approaches. Finally, the study lacks a detailed specification of each proposed event and artifact, including aspects such as descriptions, objectives, life cycles, frequency, duration, and key considerations. This absence may pose challenges for teams attempting to implement the framework, as it corresponds to the first version of FRAMUX-EV. However, these details will be included in the next version of the proposal after refinements and additional experiments.

7.6. Opportunities to Improve FRAMUX-EV

As presented in Section 6.2, the experiment conducted to validate the UX components of FRAMUX-EV provided valuable insights and findings on future actions that should be implemented. Suggestions for both UX events and UX artifacts highlight opportunities to improve utility and facilitate integration, so that the framework continues to evolve and can be used to integrate and support the UX evaluation into agile software development.

Thus, several changes have been identified based on the feedback gathered from experts. For UX artifacts (see Table 10), improvements will include providing more detailed explanations for all UX artifacts, with particular emphasis on the UX design system, UX personas, UX roles and responsibilities, and UX evaluation repository, to avoid confusion and highlight their utility. The feedback also suggested including a consideration for each UX artifact to indicate that; depending on the team’s capacity, these could be specified in more or less detail.

On the other hand, for UX events (see Table 11), modifications include adjusting the frequency of three events: weekly UX meeting, weekly user meeting, and pre-review UX meeting. First, the frequency of the weekly UX meeting will be adjusted to better accommodate the capabilities of different teams. Similarly, the weekly user meeting will be scheduled more flexibly, either by iterations or based on the volume of work completed. Additionally, the frequency of the pre-review UX meeting will be modified to ensure that teams have time to make changes before the sprint review. For this reason, the weekly UX meeting will be renamed to “UX meeting”, while the weekly user meeting will be renamed to “user meeting” to emphasize the flexibility of its frequency.

After implementing these changes, FRAMUX will require additional iterations to ensure it can be used to support teams in integrating and evaluating UX in agile software development. Thus, the following FRAMUX-EV iterations include the following stages and activities:

- Iteration 2: In this phase, the changes identified during this first iteration will be implemented to develop the second version of FRAMUX-EV. This version will need to be validated with UX practitioners by conducting two experiments: (1) an experiment focused on evaluating the specification and detailed content of UX artifacts and (2) an experiment focused on evaluating the specification and feasibility of UX events. Both experiments aim to validate that the proposal meets the industry standards and project needs. Based on these expert evaluations, the necessary refinements will be identified, which will lay the groundwork for the next iteration of the framework.

- Iteration 3: The findings from the second iteration will be applied to further refine the framework, leading to the development of the third version of FRAMUX-EV. This version will be tested in real-world projects with two case studies to validate its effectiveness and applicability. In each experiment, feedback will be collected from UX and development roles to assess the effectiveness of integrating FRAMUX-EV in agile projects. The results of these validations will be used to obtain the final necessary adjustments, preparing the framework for its final iteration.

- Iteration 4: Finally, based on the feedback and improvements from the previous iteration, the necessary adjustments will be made to FRAMUX-EV to present its final version. This version will include all refinements identified during experiments in real-world projects and will represent a mature framework for evaluating and integrating UX into agile software development.

- Following these iterations, FRAMUX-EV will continuously evolve, ensuring the integration of UX evaluation and agile software development processes and providing more robust and effective results.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

In this article, we proposed FRAMUX-EV, a framework for evaluating user experience in agile software development using Scrum. The proposal presents seven UX artifacts: (1) UX evaluation methods, (2) UX design system, (3) UX personas, (4) UX responsibilities and roles, (5) UX evaluation repository, (6) UX backlog, and (7) UX sprint backlog and four UX events: (1) pre-planning UX meeting, (2) pre-review UX meeting, (3) weekly UX meeting, and (4) weekly user meeting.

A survey of 34 practitioners validated the usefulness and ease of integration of the proposed UX components. Overall, the UX evaluation methods, UX artifacts, and UX events were perceived as useful, with most receiving ratings above 3 out of 5. However, some components were seen as more challenging to integrate into agile workflows. Based on quantitative and qualitative feedback, no UX components were eliminated from the initial version of FRAMUX-EV. However, some refinements are required: (1) provide more detailed guidance on how and when to use the proposed UX evaluation methods, especially those considered more difficult to integrate; (2) better specify the descriptions of UX artifacts to avoid confusion and include specific considerations for their use; and (3) adjust the frequency of certain UX events to better align with agile timelines and team structures.

Future work will focus on implementing these refinements and conducting further validation of the framework through case studies of real agile software development projects. In addition, a detailed specification of each event and artifact proposed in FRAMUX-EV will be provided. This will help evaluate FRAMUX-EV’s effectiveness in practice and identify any additional improvements required. By providing a structured approach to UX evaluation within agile processes, FRAMUX-EV aims to benefit both UX and development teams by creating high-quality products that truly consider users’ needs and goals. Further research and practical applications will help to evolve the framework to better serve agile and UX communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.R. and D.Q.; methodology, L.F.R. and D.Q.; software, L.F.R. and D.Q.; validation, L.F.R.; formal analysis, L.F.R. and D.Q.; investigation, L.F.R. and D.Q.; resources, L.F.R. and D.Q.; data curation, L.F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.R.; writing—review and editing, L.F.R. and D.Q.; visualization, L.F.R. and D.Q.; supervision, D.Q and C.C.; project administration, L.F.R., D.Q. and C.C.; funding acquisition, L.F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Luis Felipe Rojas is supported by Grant ANID BECAS/DOCTORADO NACIONAL, Chile, No. 21211272.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards defined in the regulations of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile (protocol code BIOEPUCV-H 779-2024, date of approval: 4 June 2024), the Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights of 2005 by UNESCO, and the ANID regulations for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all practitioners who were involved in the experiment for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Beck, K.; Beedle, M.; Bennekum, A.V.; Cockburn, A.; Cunningham, W.; Fowler, M.; Grenning, J.; Highsmith, J.; Hunt, A.; Jeffries, R.; et al. Agile Manifesto. 2001. Available online: https://agilemanifesto.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Felker, C.; Slamova, R.; Davis, J. Integrating UX with scrum in an undergraduate software development project. In Proceedings of the 43rd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, Raleigh, NC, USA, 29 February–3 March 2012; pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Sousa, A.; Valentim, N.M.C. Prototyping Usability and User Experience: A Simple Technique to Agile Teams. In Proceedings of the XVIII Brazilian Symposium on Software Quality, SBQS’19, Fortaleza, Brazil, 28 October–1 November 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusinen, K.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K. How to Make Agile UX Work More Efficient: Management and Sales Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 7th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Making Sense Through Design, NordiCHI ’12, Copenhagen, Denmark, 14–17 October 2012; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital.ai. 16th State of Agile Report. 2022. Available online: https://info.digital.ai/rs/981-LQX-968/images/AR-SA-2022-16th-Annual-State-Of-Agile-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Lárusdóttir, M.K.; Cajander, Å.; Gulliksen, J. The Big Picture of UX is Missing in Scrum Projects. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Interplay between User Experience (UX) Evaluation and System Development (I-UxSED), Copenhagen, Denmark, 14 October 2012; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kikitamara, S.; Noviyanti, A.A. A Conceptual Model of User Experience in Scrum Practice. In Proceedings of the 2018 10th International Conference on Information Technology and Electrical Engineering (ICITEE), Xiamen, China, 7–8 December 2018; pp. 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9241-210; 2010 Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Schulze, K.; Krömker, H. A framework to measure User eXperience of interactive online products. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Internet Computing and Information Services, Washington, DC, USA, 17–18 September 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roto, V.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K.; Law, E.; Vermeeren, A. User experience evaluation methods in product development (UXEM’09). In Human-Computer Interaction–INTERACT 2009: 12th IFIP TC 13 International Conference, Uppsala, Sweden, 24–28 August 2009; Proceedings, Part II 12; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 981–982. [Google Scholar]

- Experience Research Society. User Experience. Available online: https://experienceresearchsociety.org/ux/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Krause, R. Accounting for User Research in Agile. 2021. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/user-research-agile/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Persson, J.S.; Bruun, A.; Lárusdóttir, M.K.; Nielsen, P.A. Agile software development and UX design: A case study of integration by mutual adjustment. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2022, 152, 107059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agile Alliance. What is Agile? | Agile 101 | Agile Alliance. Available online: https://www.agilealliance.org/agile101/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Sommerville, I. Software Engineering, 9th ed.; Pearson Education India: Chennai, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber, K.; Sutherland, J. The 2020 Scrum Guide. 2020. Available online: https://scrumguides.org/scrum-guide.html (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Maguire, M. Using human factors standards to support user experience and agile design. In International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, N.; Wing, J. Agile UX: Integrating good UX development practices in Agile. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Information Communications Technology and Society (ICTAS), Durban, South Africa, 6–8 March 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, B.; Müller, A.; Miclau, C. Methodical Framework and Case Study for Εmpowering Customer-Centricity in an E-Commerce Agency–The Experience Logic as Key Component of User Experience Practices Within Agile IT Project Teams. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. Incl. Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinform. 2021, 12783, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argumanis, D.; Moquillaza, A.; Paz, F. A Framework Based on UCD and Scrum for the Software Development Process. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. Incl. Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinform. 2021, 12779, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T.N.; Aktunc, O. Integrating Usability into the Agile Software Development Life Cycle Using User Experience Practices. In ASEE Gulf Southwest Annual Conference, ASEE Conferences. 2022. Available online: https://peer.asee.org/39189 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Atlassian. What is Agile? | Atlassian. Available online: https://www.atlassian.com/agile (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Vermeeren, A.P.O.S.; Law, E.L.C.; Roto, V.; Obrist, M.; Hoonhout, J.; Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K. User experience evaluation methods: Current state and development needs. In Proceedings of the Nordic 2010 Extending Boundaries—Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Reykjavik, Iceland, 16–20 October 2010; pp. 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkvist, S. Towards a Model for Bridging Agile Development and User-Centered Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, D.; Paige, R.F.; Cairns, P. A systematic literature review for Agile development processes and user centred design integration. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 13–14 May 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isomursu, M.; Sirotkin, A.; Voltti, P.; Halonen, M. User experience design goes agile in lean transformation—A case study. In Proceedings of the 2012 Agile Conference, Dallas, TX USA, 13–17 August 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, D.; Miller, L. Optimizing Agile user-centred design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 5–10 April 2008; pp. 3897–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.; Sharp, H.; Maiden, N. Towards a framework for integrating agile development and user-centred design. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. Incl. Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinform. 2006, 4044, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, L.F.; Quiñones, D. How to Evaluate the User Experience in Agile Software Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Submitt. J. Under Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, L.F.; Quiñones, D.; Cubillos, C. Exploring practitioners’ perspective on user experience and agile software development. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industry Science and Computer Sciences Innovation, Porto, Portugal, 29–31 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P. Designing Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to the New Human Factors, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J.; Molich, R. Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Washington, DC, USA, 1–5 April 1990; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, E. Guerrilla Usability Testing: How to Introduce It in Your Next UX Project—Usability Geek. Available online: https://usabilitygeek.com/guerrilla-usability-testing-how-to/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Medlock, M.C.; Wixon, D.; Terrano, M.; Romero, R.; Fulton, B. Using the RITE method to improve products: A definition and a case study. Usability Prof. Assoc. 2002, 51, 1562338474–1963813932. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Putting A/B Testing in Its Place. August 2005. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/putting-ab-testing-in-its-place/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Nielsen, J. Summary of Usability Inspection Methods. 1994. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/summary-of-usability-inspection-methods/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).